1. Introduction

The chip industry is facing the challenge of developing and manufacturing ever more complex and powerful semiconductor products. Efficient manufacturing processes play a decisive role here. However, the planning and optimization of these processes are particularly challenging due to the high complexity and non-linearity of the processes. Traditional user interfaces (UI) reach their limits as they cannot adequately depict the complexity and dynamics of the processes.

Currently, the high complexity of manufacturing processes and the distribution of data across different systems such as MES (Manufacturing Execution System) and RMS (Recipe Management System) requires the expertise of specialists to oversee and make changes. Requestors often have no precise idea of the scope and impact of their change requests. Such requests tend to be made on existing templates, which, however, cannot always correctly represent the complexity and interrelationships of the plans. This often leads to errors in the requests and to considerable additional work due to multiple correction loops.

Adaptive user interfaces (AUI) offer a promising solution, as they can adapt flexibly to the requirements and preferences of the user as well as to the respective context conditions. By contextually adapting the information according to various metrics, the information displayed can be tailored to the user and the specific use case. This should lead to an improved understanding of the user and thus to fewer errors in the process. The implementation of such an AUI concept can optimize the current workflow and reduce the dependency on expert knowledge. Changes can be automatically entered into the systems after approval without experts having to transfer this data manually.

2. Research Methodology

The research methodology employed in this study is based on the Design Research Methodology (DRM) framework, as described by Blessing and Chakrabarti [

1]. DRM provides a systematic and iterative approach to design research, structured into four distinct phases. Following this framework ensures that the development process remains rigorous and aligned with both academic and practical requirements, with continuous feedback loops to incorporate insights at each stage.

The DRM approach applied in this work comprises the following phases:

Initial Research Clarification: In the first phase, the research problem and objectives were clearly defined. A comprehensive literature review was conducted to examine existing solutions and the state of the art in AUIs and manufacturing planning. This analysis helped identify knowledge gaps and provided a foundation for positioning the study within the broader research context.

Descriptive Study I: Building on the clarified research scope, this phase gathered detailed requirements for the proposed AUI concept through qualitative methods. Expert interviews and collaborative workshops were carried out in the semiconductor manufacturing industry to capture domain-specific insights. Additionally, consultations with a business architect provided user-centric perspectives and highlighted challenges in visualizing complex, non-linear manufacturing processes. These activities ensured a deep understanding of user needs and the contextual factors influencing the UI design.

Prescriptive Study: In the prescriptive phase, an initial AUI concept was developed based on the findings from Descriptive Study I. The design was then iteratively refined through collaboration with industry experts, incorporating their feedback to enhance relevance and usability. This phase culminated in the implementation of a functional prototype that demonstrates the core UI functionalities and adaptability, serving as a tangible outcome of the research for further evaluation.

Descriptive Study II: The final phase involved evaluating the AUI prototype in a real-world setting. Usability testing sessions were conducted with industry professionals to assess the interface’s effectiveness and usability. Structured feedback was collected (e.g., via questionnaires and observations) to measure user satisfaction and efficiency in performing planning tasks. This evaluation aligns with the DRM framework’s emphasis on assessing the developed solution’s usability and practical usefulness. The results from this phase were analyzed to derive insights and recommendations, to refine the UI concept further in future research.

3. State of the Art

This section reviews the current state of the art in key design principles and technologies relevant to the work. We discuss AUI concepts, including AI-driven adaptations and user modeling, as well as challenges in intelligent UIs and the conceptual distinctions between adaptability and adaptivity. Furthermore, we outline visualization techniques for complex data, and review foundational systems in manufacturing planning alongside data integration standards.

3.1. Adaptive UI Concepts

AUIs are designed to enhance user experience by dynamically adjusting the interface based on user behavior and context [

2]. The core approaches enabling AUIs draw from the fields of Artificial Intelligence (AI), User Modeling (UM), and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) [

3,

4]. These disciplines contribute methods for observing user interactions and tailoring the interface accordingly, aiming to improve usability.

3.2. Artificial Intelligence in AUIs

AI-driven AUIs rely on inference mechanisms and machine learning algorithms to monitor user actions and adapt the interface accordingly [

5,

6]. Such AI techniques have proven effective in modeling user behavior patterns and dynamically optimizing interface layouts [

4].

Table 1 summarizes key advantages and disadvantages of AI-driven adaptation in user interfaces.

3.3. User Modeling in AUIs

User Modeling focuses on personalization by analyzing explicit and implicit user data, such as navigation history and preferences [

7]. By leveraging detailed user models, an interface can offer tailored content and adaptive recommendations that align with individual needs [

4].

Table 2 highlights the advantages and disadvantages of employing user modeling in adaptive interfaces.

3.4. Challenges in Intelligent UIs

Despite these advances, designing intelligent user interfaces presents several challenges. Notable issues include:

Addressing these challenges is crucial for developing effective adaptive systems that are both useful and acceptable to end-users.

3.5. Adaptivity Concepts

According to Miraz et al. [

9], it is important to distinguish between different adaptation paradigms. Two primary concepts are

adaptability and

adaptivity, and there is also a hybrid approach:

Adaptability: Users manually adjust certain interface characteristics (e.g., layout, content density) to suit their preferences or context.

Adaptivity: The system autonomously adapts its behavior or appearance in response to the user’s needs and usage patterns, without explicit user input.

Mixed-initiative: A combination of user-driven and system-driven adaptation mechanisms, where both the user and the system cooperate in the adaptation process.

Each of these approaches has its merits: adaptability gives users control, adaptivity offers convenience and proactivity, and mixed-initiative seeks to balance both by leveraging the strengths of each approach.

3.6. Technological Foundations and Existing Systems in Manufacturing Planning

In the domain of manufacturing planning, several established software systems provide foundational capabilities:

Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES): Systems for real-time production monitoring and shop-floor control, ensuring that manufacturing processes are executed efficiently [

10].

Advanced Planning and Scheduling (APS): Tools for optimizing production workflows and resource allocation, often using algorithms to generate feasible and efficient schedules [

11].

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP): Comprehensive platforms that integrate various business processes (e.g., inventory management, order processing, human resources) to provide a unified view of enterprise operations [

12].

These systems represent the state of practice in manufacturing, and any advanced planning tool must often interface with or build upon their capabilities.

3.7. Data Integration and Interoperability

Ensuring seamless data exchange across heterogeneous systems requires common standards and integration strategies. Key technologies include:

Standard data formats and interfaces: Widely adopted formats like XML [

13], JSON [

14], industrial communication standards such as OPC UA [

15], and web service architectures like RESTful APIs [

16]. These standards facilitate interoperability by providing a common structure for data and interactions.

Methods of data integration: Techniques such as (ETL) processes [

17], data virtualization [

18], and API-driven integration frameworks [

19] enable combining data from multiple sources. These approaches help maintain consistency and accuracy of information while allowing different software systems to work in concert.

By employing standardized data formats and robust integration methods, modern manufacturing planning systems can achieve a high degree of interoperability and flexibility, which is essential for scaling and evolving in complex industrial environments.

4. Requirements Analysis

4.1. Context Analysis

Semiconductor manufacturing planning has become increasingly complex and non-linear. Various software tools (such as a MES) are used for production planning and control. However, the current workflow for modifying production process plans is fragmented and inefficient:

Manual Data Handling: Engineers must export process data from the MES into Excel spreadsheets to make changes. Adjustments are done using Excel macros and then formatted into modification requests.

Error-Prone Process: Each modification request is reviewed and approved manually before re-importing the data into the MES. Using multiple disconnected tools (MES, Excel, etc.) leads to inconsistencies during data transfer and increases the chance of errors.

Lack of Unified Interface: There is no standardized way to visualize or edit process plans across the different systems. Users have to jump between tools, which is time-intensive and reduces transparency.

To address these issues, an AUI is proposed as a centralized platform for process visualization and modification. This UI will interact directly with MES data to provide real-time updates while enforcing process security. By consolidating all necessary information into a single interface, the system will replace the Excel-based workaround—reducing manual data handling, improving data consistency, and enhancing transparency in semiconductor manufacturing planning.

4.2. Requirements for Process Plan Visualization

The new AUI must meet several key requirements to effectively visualize and manage non-linear process plans while remaining familiar to users:

Preserve Tabular Format: Maintain a spreadsheet-like tabular view for process plans. Since engineers are used to Excel, the UI should present data in a familiar table format, while also allowing more advanced data structures behind the scenes.

Visualize Non-Linearity: Support graphical representations (e.g. flowcharts or diagrams) to depict complex flows. This includes showing rule-based branches (if/else decisions) and rework loops that are not easily captured in a flat table.

Subplan Differentiation: Clearly distinguish sub-plans or subprocesses from main process flows. The UI should use a hierarchical view or links to let users navigate between a main process and its associated subplans seamlessly.

Adaptive Detail Views: Provide detailed tabular views (similar to Excel) for experts, but allow dynamic filtering and customizable columns. Users should be able to see only the information relevant to their task or role, preventing information overload.

Multiple View Modes: Enable flexible switching between different representations. For example, a user might toggle between a graphical flowchart view and the detailed table view of the same process, depending on what is more useful at the moment.

Data Integration and Consistency: Integrate directly with the MES and other data sources. The UI should pull live data for up-to-date process information and ensure that any modifications made in the UI can be safely transmitted back to the MES. All changes should be tracked and, if necessary, be reversible to maintain data integrity.

4.3. User Profiles and Role-Based Adaptation

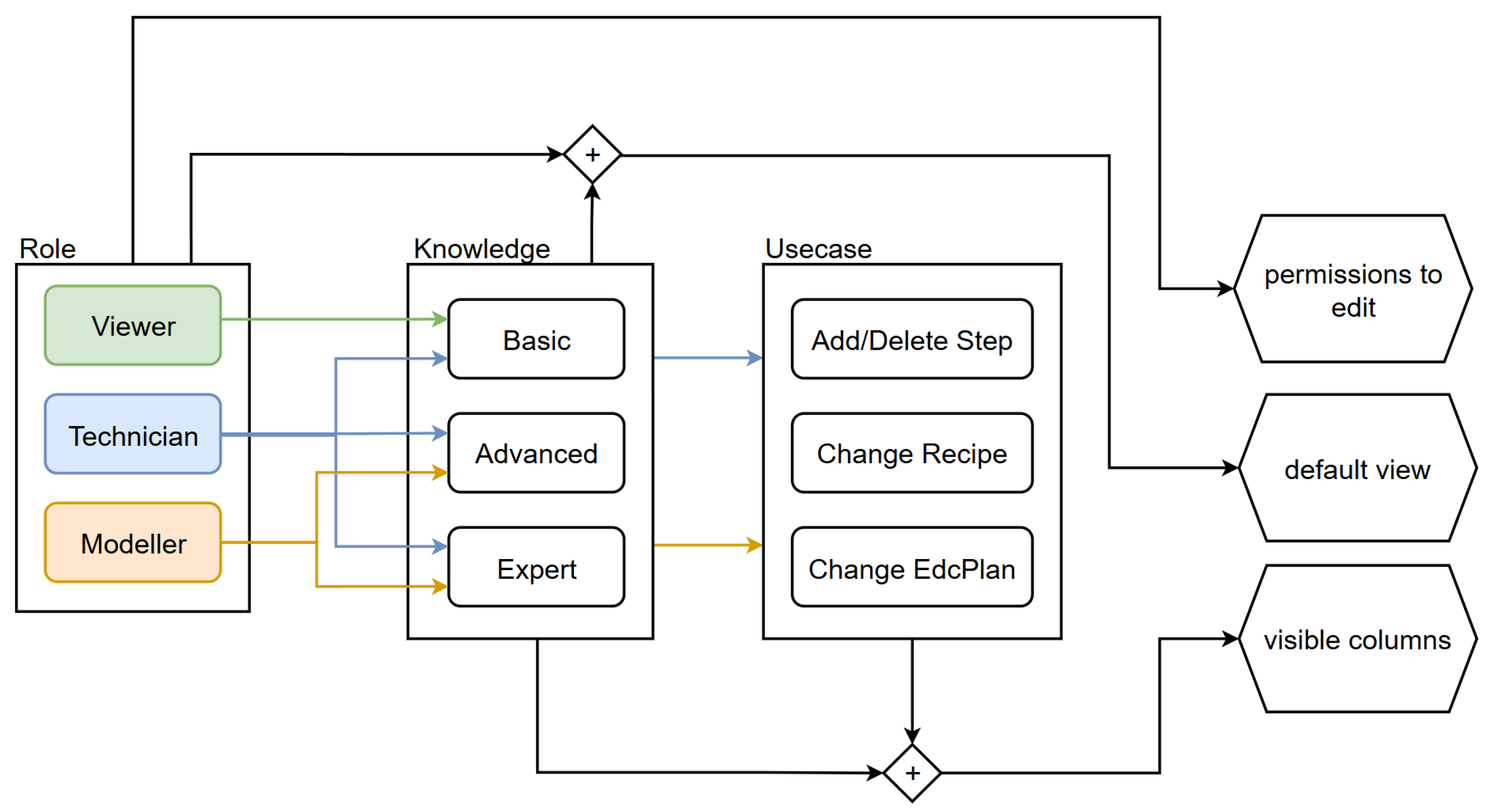

Different user groups will interact with the system, each with specific needs and levels of expertise. The UI must adapt to these roles to provide an optimal user experience for each:

Viewers: These users (e.g. managers or auditors) oversee production plans but do not edit them. They need high-level overviews and visual summaries of the process flow. The UI should present simplified, easy-to-understand graphics without overwhelming technical detail.

Process Engineers: They are responsible for creating and modifying process parameters. They require both the big picture and the fine details—graphical representations to understand overall flow, and detailed tabular data to tweak specific steps. The UI should let them drill down into specifics as needed.

MES Experts: These specialists validate and approve any changes before they are loaded into the MES. They need full visibility into all modifications, including comprehensive tables and change tracking logs. The interface should allow them to review each request in detail for correctness and compliance.

To accommodate these varying needs, the UI will employ role-based adaptation. This means the interface dynamically adjusts the amount and type of information shown based on the user’s role and context. Each user will see the most relevant views by default (preventing unnecessary complexity), while still having the option to access more detailed information when required. This adaptive approach ensures efficiency and clarity for every user group, from novices to experts.

4.4. Challenges

Designing and implementing this AUI comes with several challenges that must be addressed:

Balancing Familiarity with Innovation: The interface should retain the familiar elements of the current Excel-based workflow to encourage user adoption. At the same time, it must introduce new visualization methods (like flowcharts for decision points and loops) to handle non-linear processes. Achieving this balance is crucial so users feel comfortable transitioning to the new system.

Data Exchange and Consistency: The UI will directly interface with the MES and possibly other systems. Ensuring smooth, real-time data exchange without errors is technically challenging. Any change made in the UI must remain consistent with the MES data, requiring robust data validation and version control to maintain process integrity across platforms.

Role-Based Complexity: Implementing a dynamic, role-tailored interface adds complexity to the design. The system must simplify the view for basic users while still providing power-users (like process engineers and MES experts) full access to detailed information and controls. Managing these layers of access without confusing users is a delicate task.

Integration into Existing Workflows: Replacing the established Excel-and-MES workflow means the new UI has to integrate into the current production IT environment smoothly. It must be reliable and secure, since any interface failure could disrupt production planning. Thorough testing and iterative refinement will be needed to ensure the UI enhances efficiency without compromising process security.

Successfully overcoming these challenges is critical for the AUI to fulfill its promise. By carefully balancing user familiarity with advanced features, maintaining data integrity, and tailoring the experience to different roles, the new interface can significantly improve the efficiency and accuracy of semiconductor manufacturing planning.

5. Proposed Concept

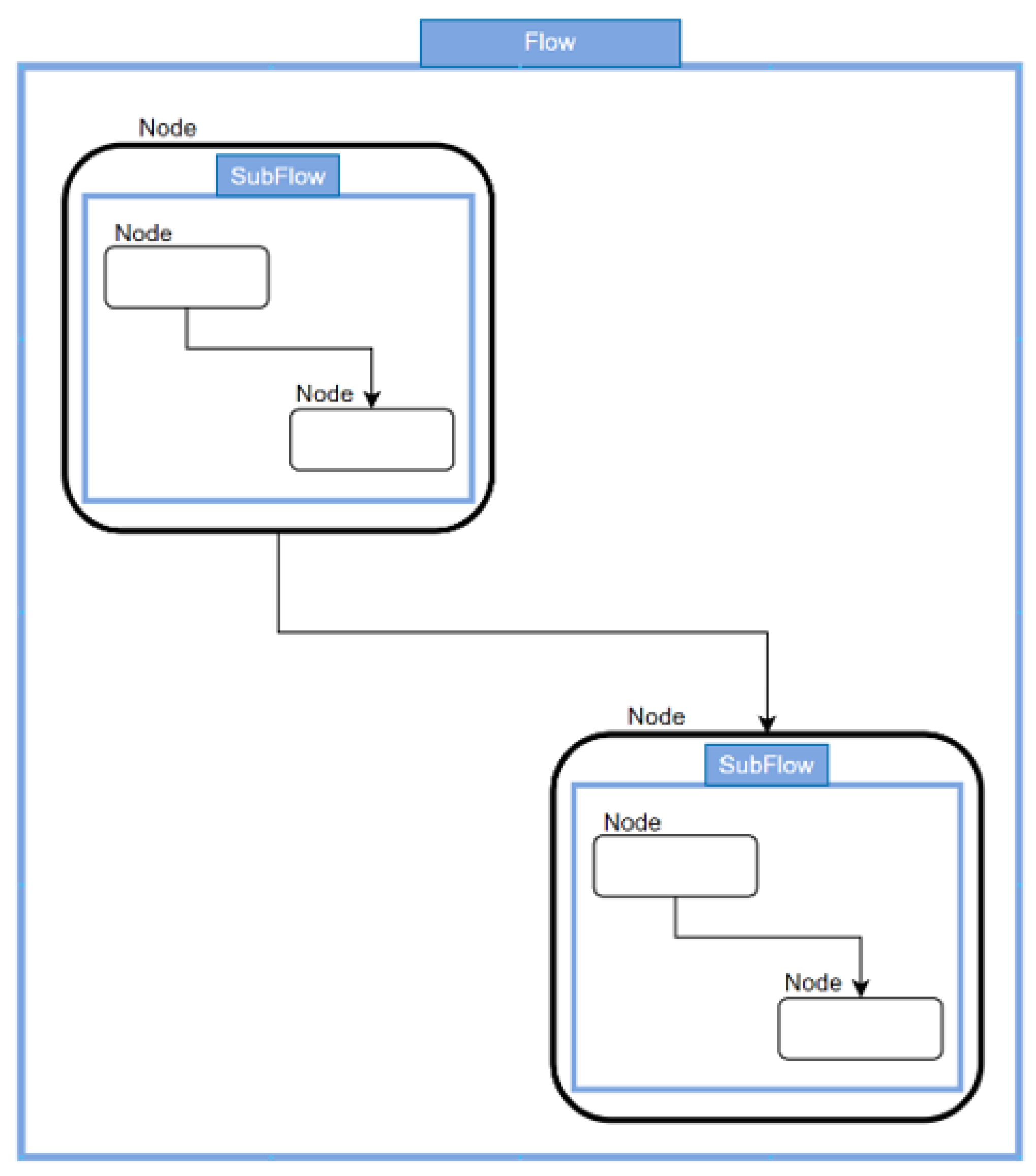

This concept addresses the challenges of displaying and processing complex, non-linear production plans in the chip industry and was developed to replace the Excel-based workflow most commonly used to date and to enable seamless data exchange with the MES. At its core, the concept is based on an AUI that dynamically adapts to different user groups and offers both graphical and tabular views to meet the various requirements of users. The complex process plans are displayed in the form of flowcharts, with each process plan consisting of a series of sub-plans, which in turn are visualized as nodes (see

Figure 1). Within these sub-plans are sequences of so-called steps, which are arranged in a linear sequence until a control condition or a rework process triggers a branch or a loop. This hierarchical structure ensures that the complex branches of the production processes remain clearly recognizable and at the same time provides an intuitive overview of all relevant steps and dependencies.

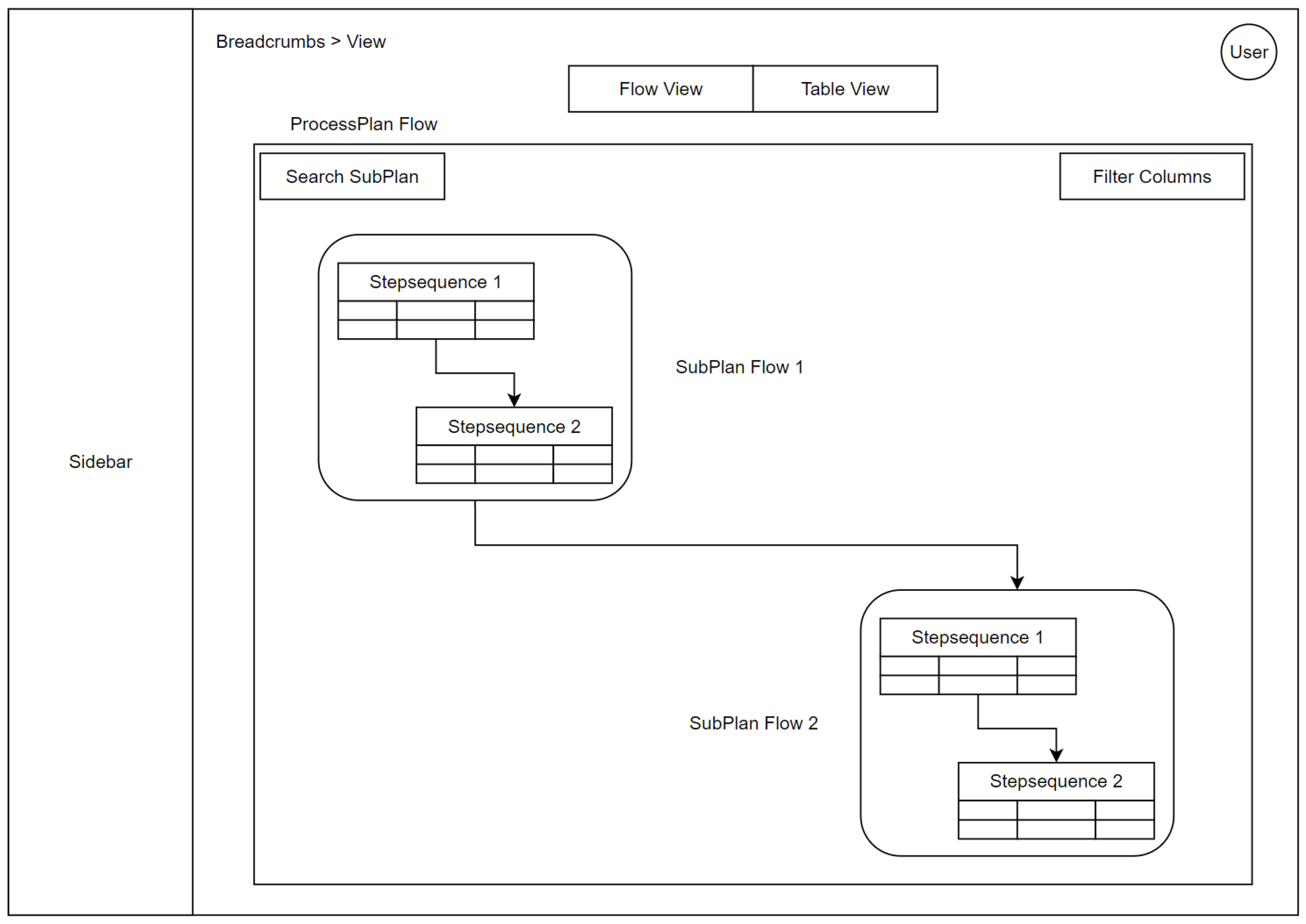

The graphical representation of flows and subflows makes it possible to emphasize the non-linear nature of these processes, as branches, loops and returns are immediately visible. Interactive functions such as zooming or panning the flow diagrams allow users to quickly take a detailed look at specific subplans and their steps or to view the entire process chain (see

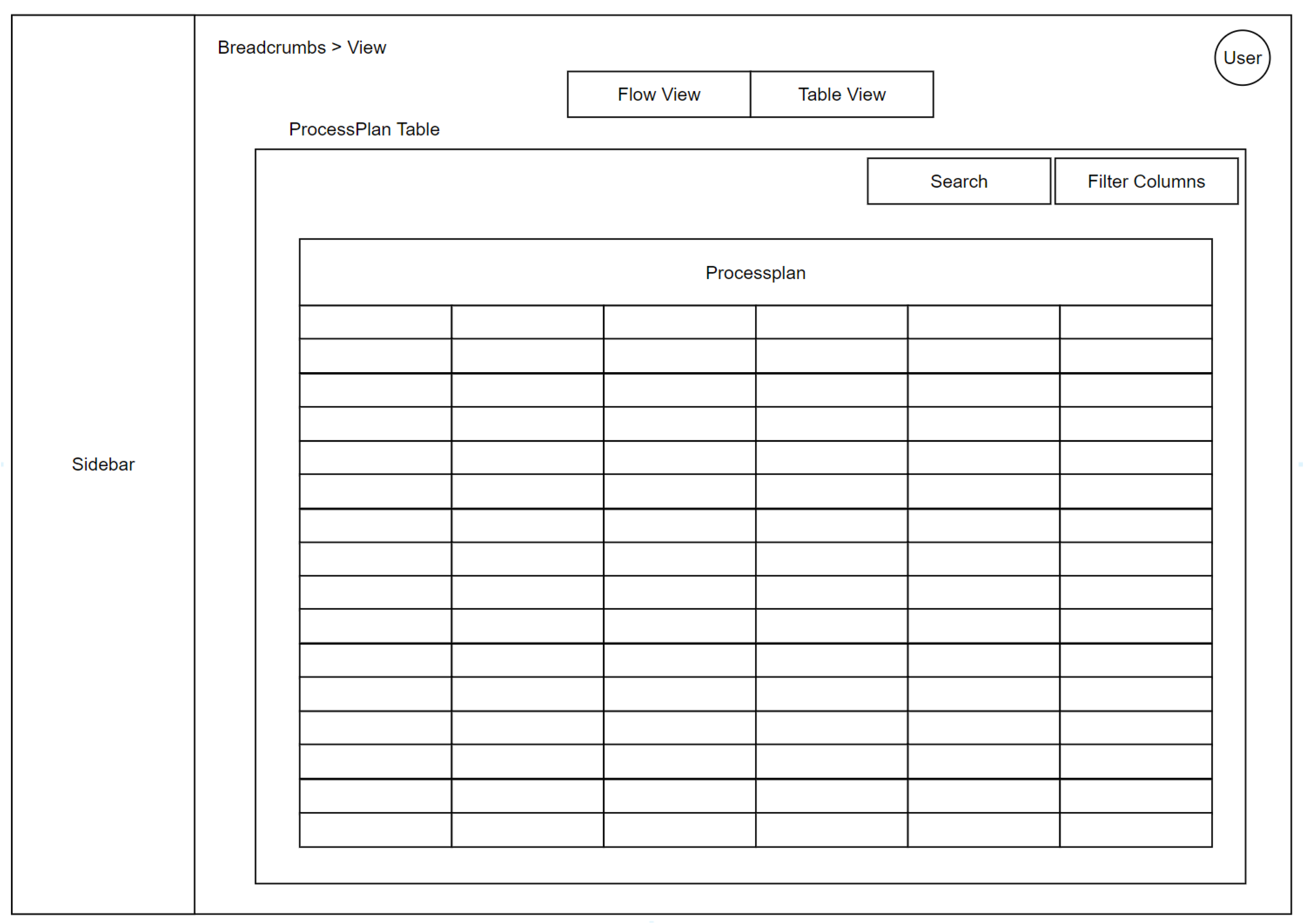

Figure 2). In addition, a tabular view is offered in which all steps of a process plan are listed in compact form. This view allows experts and advanced users to efficiently process large amounts of data, as they can search for specific steps or show or hide certain columns (see

Figure 3). Seamless switching between the two views is ensured via a tab switcher integrated into the user interface, so that users can decide at any time whether a visually clear or data-focused perspective is more important to them.

The adaptability of the concept extends beyond pure visualization, because different functions and editing rights are provided depending on the respective role, for example viewer, process engineer or MES expert role. For example, users in the role of viewer may only view the plans, while process engineers can make their own adjustments while experts work with the tabular view and extended information density as standard. Despite these role-specific default settings, it is possible to adapt the respective interfaces to personal preferences, for example by hiding individual columns or freely arranging the subplans (see

Figure 4).

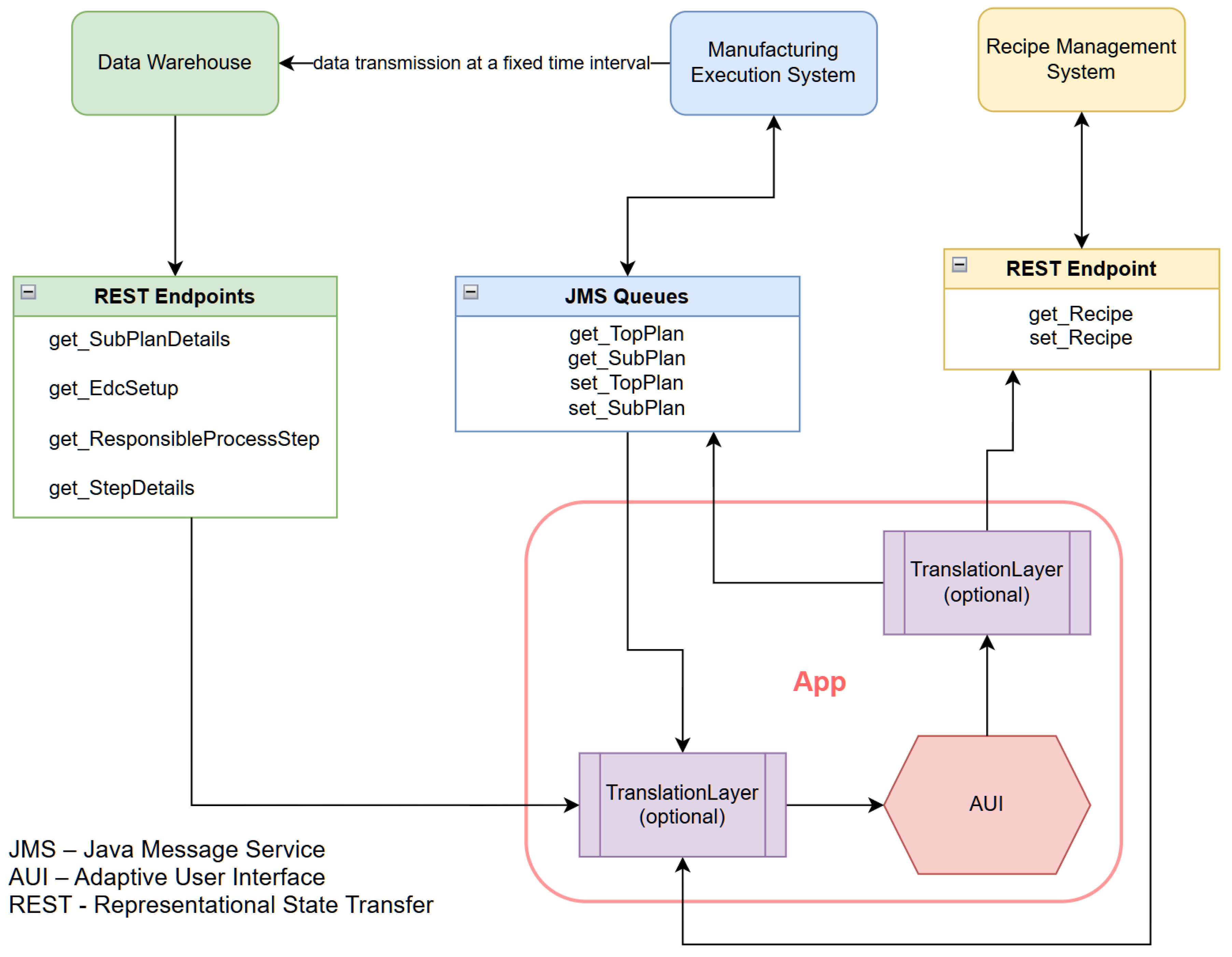

This UI concept is complemented by a sophisticated data integration strategy that pursues the primary goal of using the most up-to-date and consistent data while simultaneously writing back changes to the source systems, in particular the MES. Data is to be retrieved from the source systems in JSON format via REST and JMS interfaces and prepared in a translation layer for display in the user interface. This allows both the process plans and all relevant context data to be integrated in real time. Changes made in the front end are in turn converted back into the required original format and transmitted to the respective systems so that the data remains up-to-date in all platforms involved.

6. Proof of Concept

The developed prototype serves as a proof of concept to validate the previously conceptualized approach of an AUI for complex, non-linear production plans in the chip industry. The prototype was implemented as a web application based on Next.js, allowing users to use the prototype directly in the browser without the need for complex software installation, which guarantees a high degree of flexibility and fast update capability.

In order to meet the core requirements of a dynamically adaptable interface that can represent the non-linearity of the plans, ReactFlow is used for the interactive representation of the non-linear processes. This allows branches, rework loops and control processes to be mapped in the form of flowcharts, whereby sub-plans can be turned into nested sub-flows using customNodes. This offers the advantage that even highly complex process chains are clearly visualized in a hierarchical structure and can be easily navigated using zoom and drag functions. The prototype architecture also provides a translation layer in which all JSON data provided by the MES or other systems is prepared in such a way that it fits directly into the ReactFlow node and edge structure (seen in

Figure 5).

Changes made to the displayed process plans in the browser flow seamlessly back into this JSON cache so that they can be transferred back to the source system if required, see

Figure 6.

This procedure guarantees synchronization of the table and flow view, prevents inconsistencies in the database and allows a possible release or approval function before changes are finally transferred to the MES.

In order to illustrate how the newly developed solution compares to the existing system and which requirements it already reliably fulfills, an evaluation was carried out based on user interviews. On the one hand, this aims to record objective metrics such as processing time and error rate and thus gain information about possible efficiency improvements, but on the other hand also to determine a picture of user satisfaction based on subjective questions. A representative cross-section of respondents from different roles and knowledge levels was selected, including viewers, process engineers and MES experts. Each interviewee went through a predefined process in which they first completed tasks in the old system and then in the new prototype. During this process, both the time taken to complete identical requests and any errors that occurred in both systems were documented so that a direct comparison could be made using these key figures. In addition, the test subjects were surveyed after completing the tasks using a guideline that recorded their subjective perception of the prototype in terms of clarity, ease of use and general satisfaction.

The functions implemented in the prototype and the presentation of the process plans using ReactFlow and the translation layer are to be tested under realistic conditions in this way, while the users provide feedback on their individual workflows and the user interface. The results will serve as a basis for possible further development and fine-tuning of the software. In this way, the steps taken will demonstrate the technical feasibility of the solution on the one hand, and on the other hand give an impression of how it could fit into the everyday workflow, with both efficiency and user-friendliness playing a role.

7. Discussion

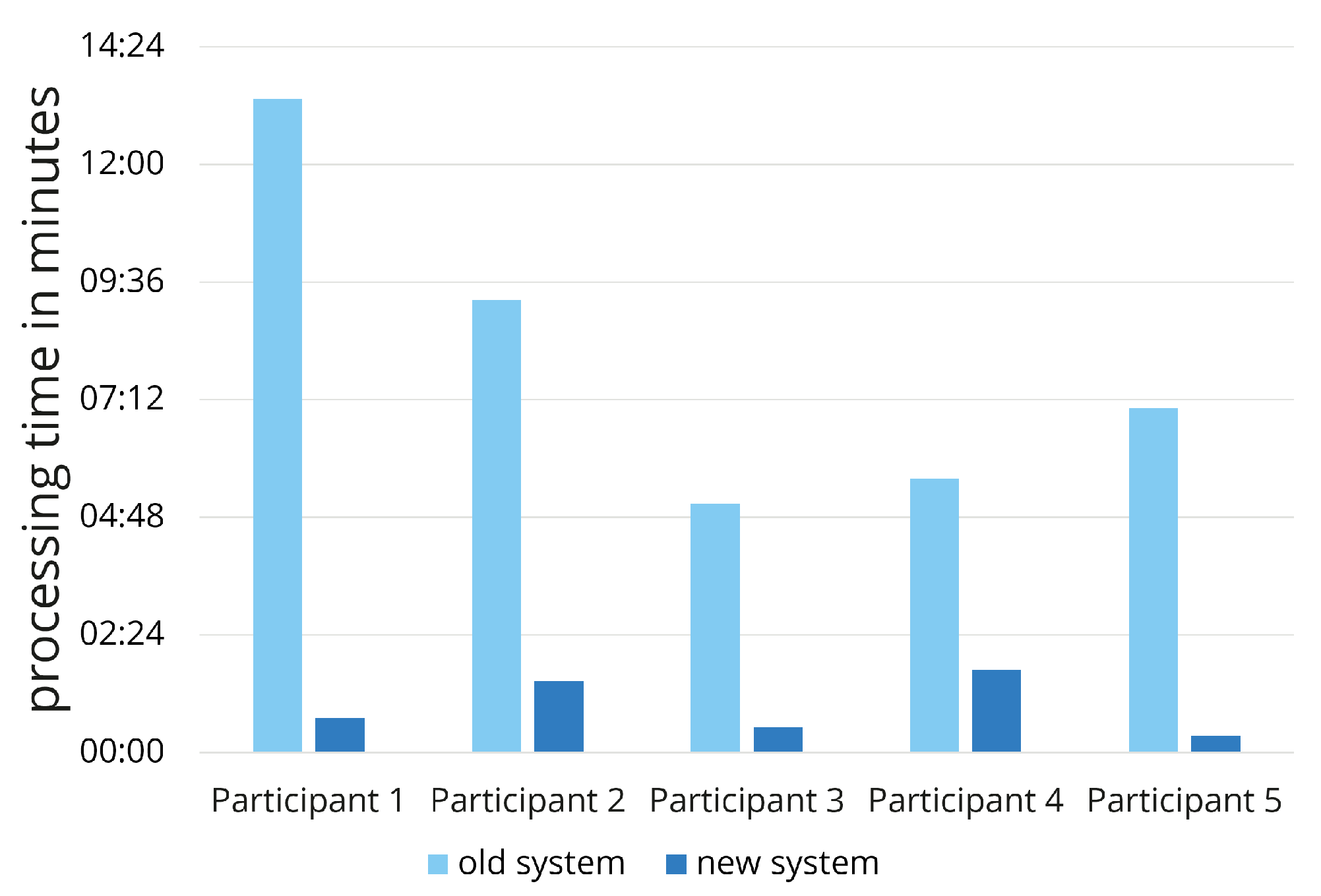

The results of the evaluation show that the prototype developed has clear advantages over the existing system in terms of efficiency and susceptibility to errors. In particular, the measurement of processing time (time on task) clearly shows that users were able to complete their tasks significantly faster in the new system. An average time saving of almost twelve times was recorded, which proves that the new interface simplifies and accelerates the previous workflow in key areas (seen in

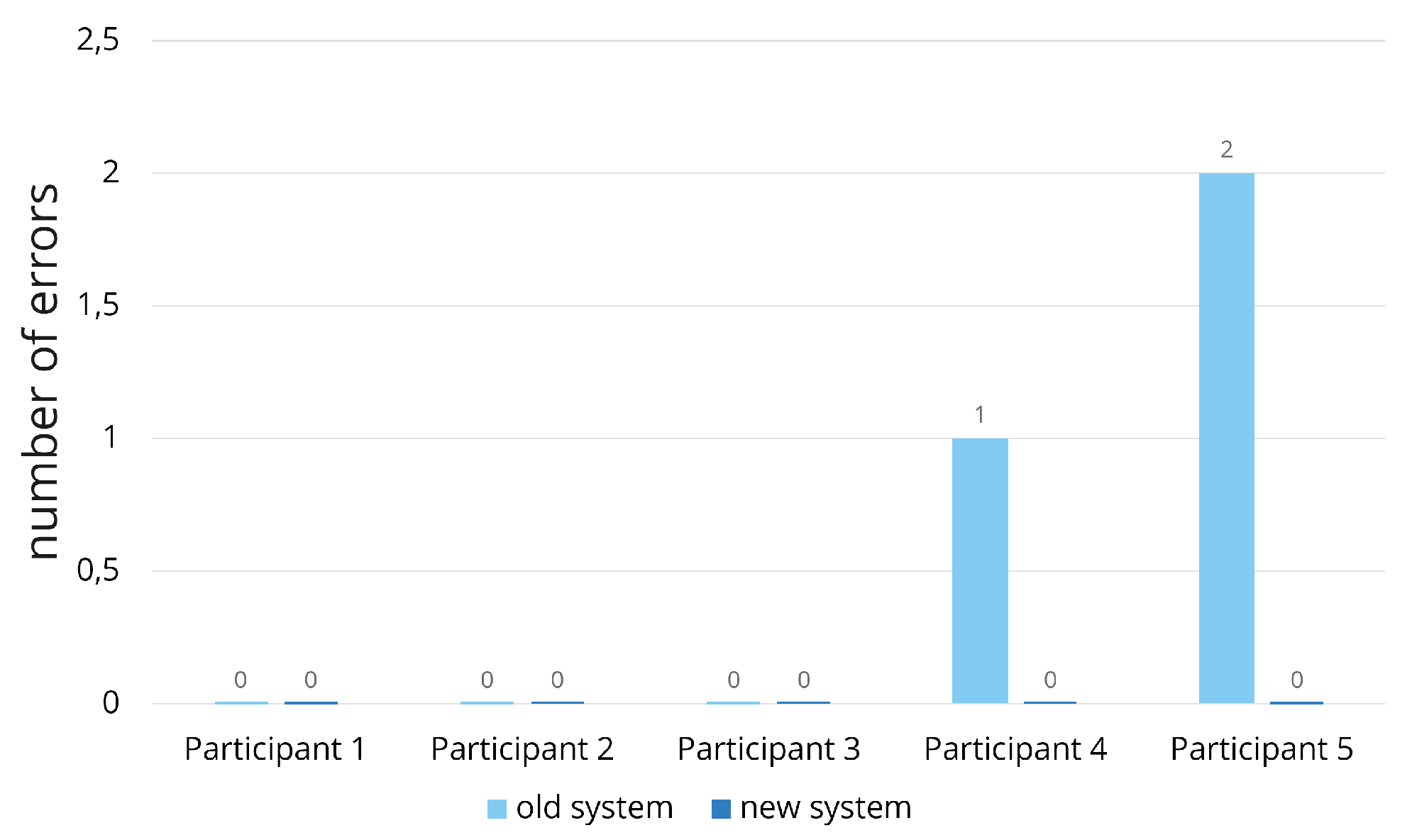

Figure 7). At the same time, the error rate was reduced for the request tested in that use case (seen in

Figure 8). As important information is located centrally in one place and no longer has to be obtained from different systems, the likelihood of users producing discrepancies when entering or transferring data is reduced.

These findings have direct implications for the developed concept of the adaptive user interface. Firstly, they confirm the assumption that the combination of a tabular and a graphical view makes complex processes easier to understand and reduces potential operating errors. Secondly, they confirm that the integration of dynamic information via REST interfaces or message queues significantly reduces the processing effort for routine tasks and thus underlines the benefits of closer integration with the manufacturing execution system. Thirdly, the high time savings combined with a reduced error rate highlight the importance of intuitive, context-sensitive visualization. The approach of bundling subplans clearly as nodes and implementing additional interaction options such as zoom, drag-and-drop and search functions appears to be proving its worth in practice.

The results also suggest that the adaptation to different roles, such as viewers, process engineers or MES experts, makes sense and helps to reduce the complexity of the interface for less experienced users. The feedback from the user interviews makes it clear how helpful it can be to activate certain views or editing functions only for those roles that actually have to perform the associated tasks. In this context, it seems essential for a future expansion of the system to enable even more granular settings. This is because the wider the area of application, the more likely it is that additional roles with different knowledge and responsibilities will need to be taken into account. It will also be important to develop automated mechanisms that adapt the user interface to specific user needs.

Despite the positive results, it should be noted that this is a limited prototype whose range of functions cannot yet cover all real use cases. Many of the processes relevant in the production context, such as the creation of completely new plans, version management for existing plans or complex rule and rework procedures, have only been implemented as prototypes or in simplified form to date. It is therefore foreseeable that further validation and automation mechanisms will have to be added in a real scaling in order to make both the data input and the release processes reliable and secure.

In addition, only a limited number of test subjects were included in the evaluation, which meant that individual aspects, such as certain use cases or very specific production plans, could not be examined in depth. A much more comprehensive test phase, ideally in the real production environment over a longer period of time, would be necessary in order to conclusively assess the generalizability and robustness of the system. This would give rise to additional questions, such as how the system could be managed with different product categories or production stages.

8. Conclusions

In this work, an AUI was developed for production planning in the semiconductor industry. The primary objective was to visualize and optimize complex, non-linear manufacturing plans while enhancing both user-friendliness and efficiency in plan editing through a dynamic, adaptive interface. To achieve this, a comprehensive requirements analysis was conducted, addressing the specific needs of diverse user groups. These findings informed the design and implementation of interactive components and dynamic representations within the prototype.

The evaluation results demonstrate a substantial reduction in processing time and a significant decrease in errors when using the prototype. Users completed their tasks up to twelve times faster compared to previous systems, and the error rate was reduced. Notably, the integrated graphical and tabular views facilitated more intuitive navigation of the complex processes. Consequently, the prototype successfully met the specified requirements and shows great potential for improving the efficiency of semiconductor production planning.

9. Future Research

Despite the promising results, several open challenges remain and should be addressed in future research and implementations. First, system scalability warrants further investigation, particularly in scenarios involving larger data sets and more complex use cases. Current tests were limited to relatively small-scale application contexts, whereas real-world manufacturing environments often encompass a wider range of processes and roles, thus posing greater challenges.

In addition, further customization for deployment in different corporate and system landscapes should be explored. Adapting it for other industries and organizations may require additional adjustments especially with respect to data integration.

Future research may also focus on advancing the UI’s adaptive mechanisms. In particular, automated adaptation to various user roles and contexts could yield even greater individualization and efficiency gains. Moreover, integrating novel technologies such as artificial intelligence for predictive modeling of process flows could further optimize the system.

Overall, this work illustrates the potential of an adaptive user interface for production planning, though further validation and scaling are necessary to achieve a fully comprehensive and practical implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Manuel Jorde and Lucas Vogt; Data curation, Manuel Jorde; Formal analysis, Manuel Jorde; Funding acquisition, Leon Urbas; Investigation, Manuel Jorde and Lucas Vogt; Methodology, Manuel Jorde and Lucas Vogt; Project administration, Lucas Vogt and Leon Urbas; Resources, Lucas Vogt; Software, Manuel Jorde; Supervision, Lucas Vogt and Leon Urbas; Validation, Manuel Jorde and Lucas Vogt; Visualization, Manuel Jorde; Writing – original draft, Manuel Jorde; Writing – review & editing, Lucas Vogt.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artifical Intelligence |

| APS |

Advanced Planning and Scheduling |

| AUI |

Adaptive User Interface |

| DRM |

Design Research Methodology |

| ERP |

Enterprise Ressource Planning |

| ETL |

Extract-Transform-Load |

| HCI |

Human-Computer Interaction |

| MES |

Manufacturing Execution System |

| RMS |

Recipe Management System |

| UI |

User Interface |

| UM |

User Modeling |

References

- Blessing, L.T.M.; Chakrabarti, A. DRM, a Design Research Methodology, 1 ed.; Springer London, 2009; pp. XVII, 397. eBook ISBN: 978-1-84882-587-1, Published: 13 June 2009; Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-84882-586-4, Published: 30 June 2009; Softcover ISBN: 978-1-4471-5774-8, Published: 26 November 2014. ISBN 978-1-84882-587-1. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.M.C.; Calleros, J.M.G.; Meixner, G.; Paternò, F.; Pullmann, J.; Raggett, D.; Schwabe, D.; Vanderdonckt, J. Model-Based UI XG Final Report. 2010. Available online: https://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/model-based-ui/XGR-mbui-20100504/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Gullà, F.; Ceccacci, S.; Germani, M.; Cavalieri, L. Design Adaptable and Adaptive User Interfaces: A Method to Manage the Information. In Proceedings of the Biosystems and Biorobotics, 09 2014, Vol. 11. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Cortes, V.; Zayas-Perez, B.E.; Zarate-Silva, V.H.; Ramirez Uresti, J.A. Current Trends in Adaptive User Interfaces: Challenges and Applications. In Proceedings of the Electronics, Robotics and Automotive Mechanics Conference (CERMA 2007); 2007; pp. 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wei, L.; Pu, Z. Measuring and Improving User Experience Through Artificial Intelligence-Aided Design. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Parvatikar, H. Adaptive AI: Unlocking Benefits and Overcoming Challenges, 2023. Accessed: 2024-05-27.

- Kobsa, A. Adaptive Verfahren – Benutzermodellierung (Adaptive Methods – User Modeling). In Grundlagen der Information und Dokumentation; 5th completely new edition 2011 ed.; Kuhlen, R., Seeger, T., Strauch, D., Eds.; De Gruyter Saur, 2004; pp. 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahão, S.; Insfran, E.; Sluÿters, A.; Vanderdonckt, J. Model-based intelligent user interface adaptation: challenges and future directions. Software and Systems Modeling 2021, 20, 1335–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraz, M.H.; Ali, M.; Excell, P.S. Adaptive user interfaces and universal usability through plasticity of user interface design. Computer Science Review 2021, 40, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurdiyanto, H. Critical Role of Manufacturing Execution Systems in Digital Transformation of Manufacturing Industry. Journal of Electrical Systems 2024, 20, 2432–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellsdotter Ivert, L.; Jonsson, P. The potential benefits of advanced planning and scheduling systems in sales and operations planning. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2010, 110, 659–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, Z.N.; Balázs, V. Machine learning-driven optimization of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems: a comprehensive review. Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2024, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, T.; Paoli, J.; Sperberg-McQueen, C.M.; Maler, E.; Yergeau, F. Extensible Markup Language (XML) 1.0, 2008. W3C Recommendation.

- Ecma International. The JSON Data Interchange Standard, 2013. Standard ECMA-404.

- OPC Foundation. OPC Unified Architecture (OPC UA), 2021. OPC Foundation.

- Patni, S. Fundamentals of RESTful APIs. In Pro RESTful APIs: Design, Build and Integrate with REST, JSON, XML and JAX-RS; Apress: Berkeley, CA, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, T.; Blackshear, L. , CA, 2020; pp. 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-5497-4_1.ETL. In Prepare Your Data for Tableau: A Practical Guide to the Tableau Data Prep Tool; Apress: Berkeley, CA, 2020; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordon, A.; Alexander, D. Data Virtualization: A Game-Changer for Big Data Analytics. Zenodo 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronwald, K.D. , Heidelberg, 2024; pp. 91–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-68668-3_8.Interoperabilität. In Data Management: Der Weg zum datengetriebenen Unternehmen; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2024; pp. 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Short Biography of Authors

|

Manuel Jorde received his Diploma in Information Systems Engineering (Dipl.-Ing.) from the Technische Universität Dresden, Germany, in 2024. He is currently working at Robert Bosch Semiconductor Dresden GmbH as a Full Stack Developer, focusing on process automation in semiconductor workflows. His work involves designing and implementing software solutions that optimize manufacturing processes, enhance data integration, and improve operational efficiency in semiconductor production. |

|

Lucas Vogt received his Diploma in mechanical engineering (Dipl.-Ing.) from the TUD Dresden University of Technology, Germany, in 2021. He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. degree in process engineering at the chair of Process Control Systems, TUD Dresden University of Technology, Germany. Since 2021 he has been a research associate at the Process-to-Order Group and is currently working as a team lead for “Smart Architectures” within the P2O-Group. His research interests include future cyber-physical production systems with a special focus on automation architectures for the biopharmaceutical industry. |

|

Leon Urbas received the Dr.-Ing. and Habilitation degrees. He is currently the Head of the Process-to-Order Group, TUD Dresden University of Technology, Germany, and a professor. His research interests include formal information and simulation models in process system design and automation, their application in model-driven methods for engineering support systems and integrated highly efficient workflows for human–computer collaboration in automation engineering. These technology-oriented topics are supported by research in human-centered automation, such as cooperation across control rooms and shop floors, usability engineering for supervisory control, and simulation-based decision support. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).