Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Literature Review

III. Methodology

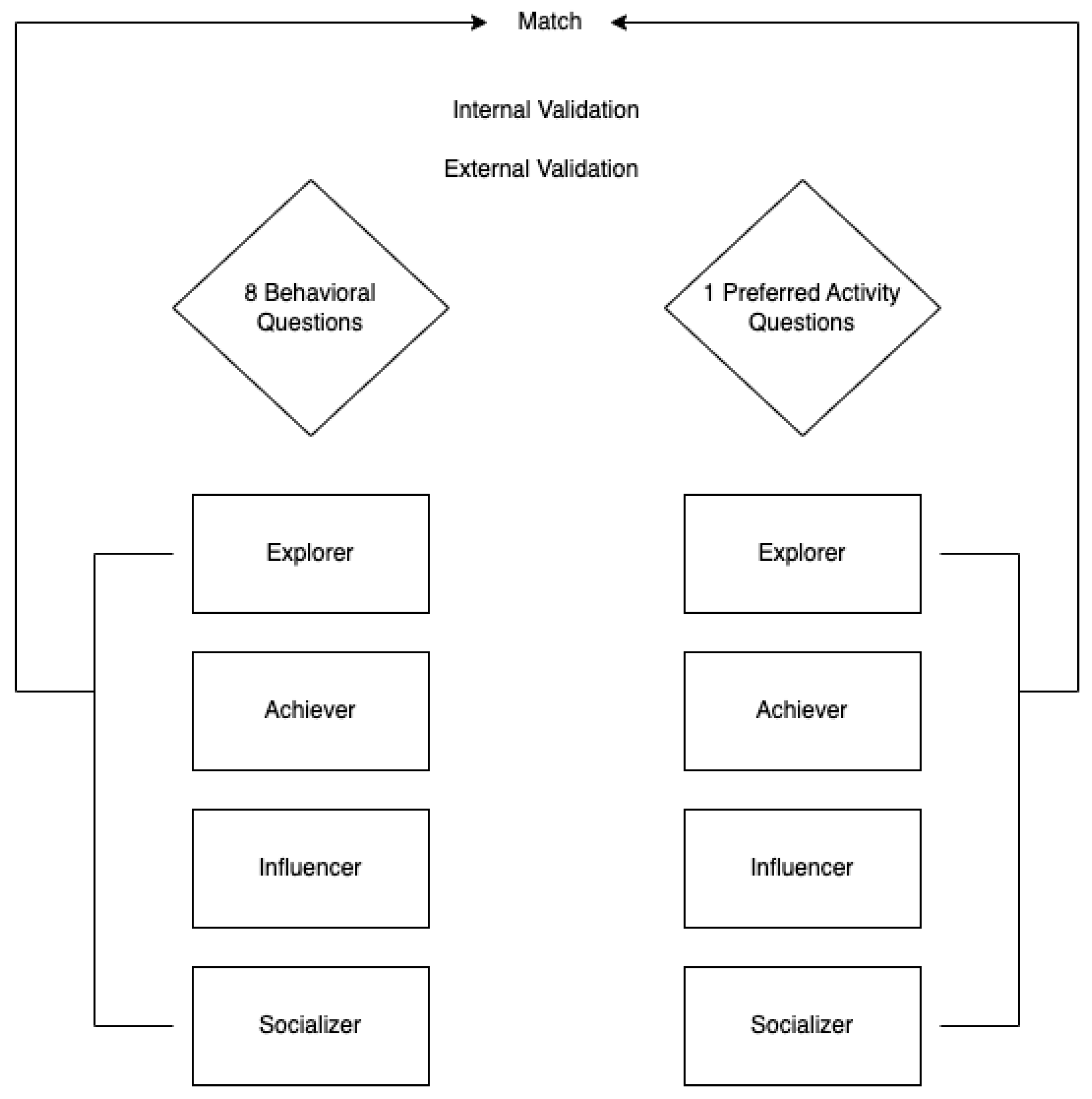

IV. Design and Procedures

V. Data Collection

VI. Data Re-evaluation

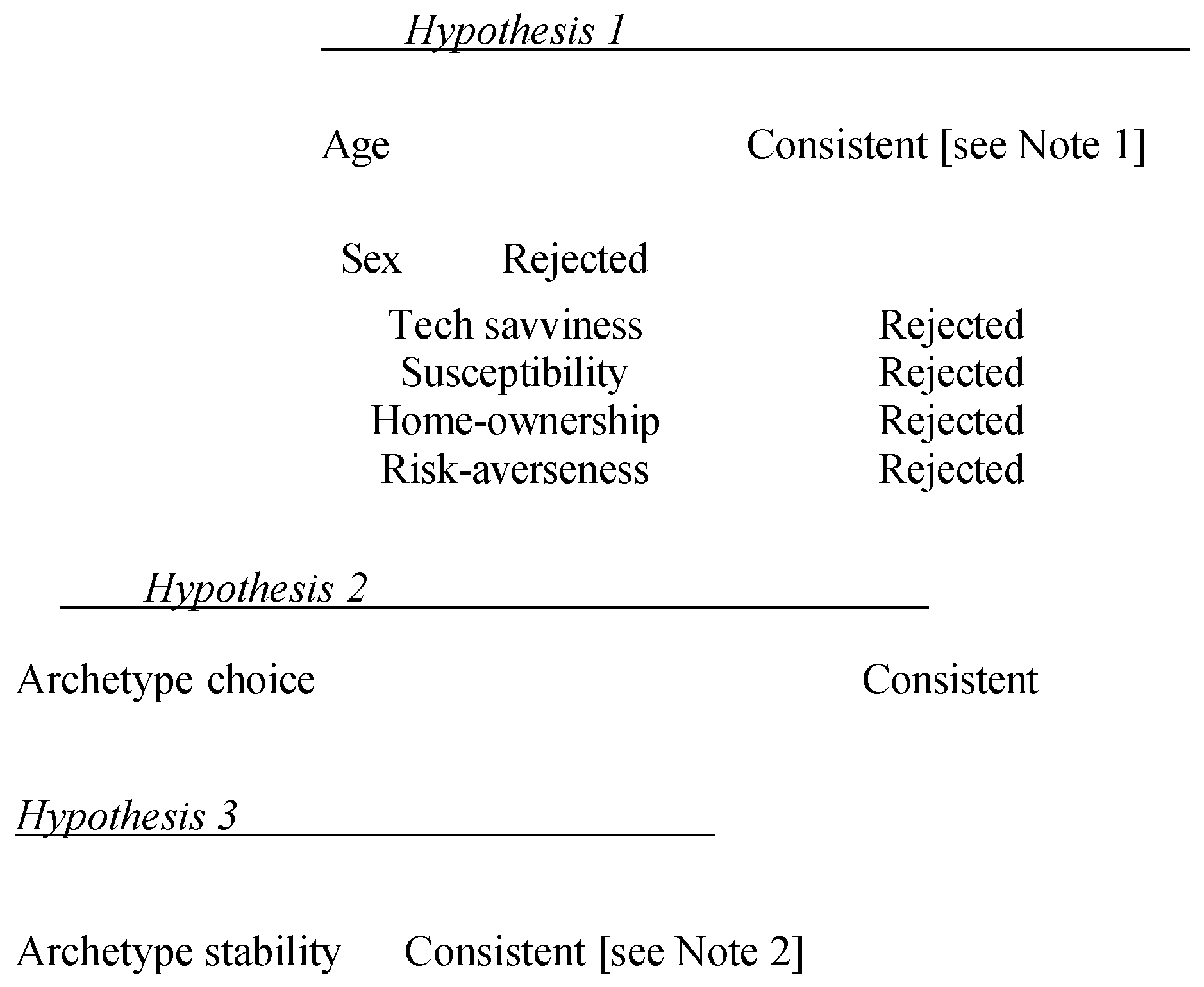

VII. Hypotheses

- (1)

- An individual’s personality type can be determined from self-reported data about themselves;

- (2)

- An individual’s personality type can predict their choices; and

- (3)

- An individual’s personality type corresponds to an archetype that is stable over time.

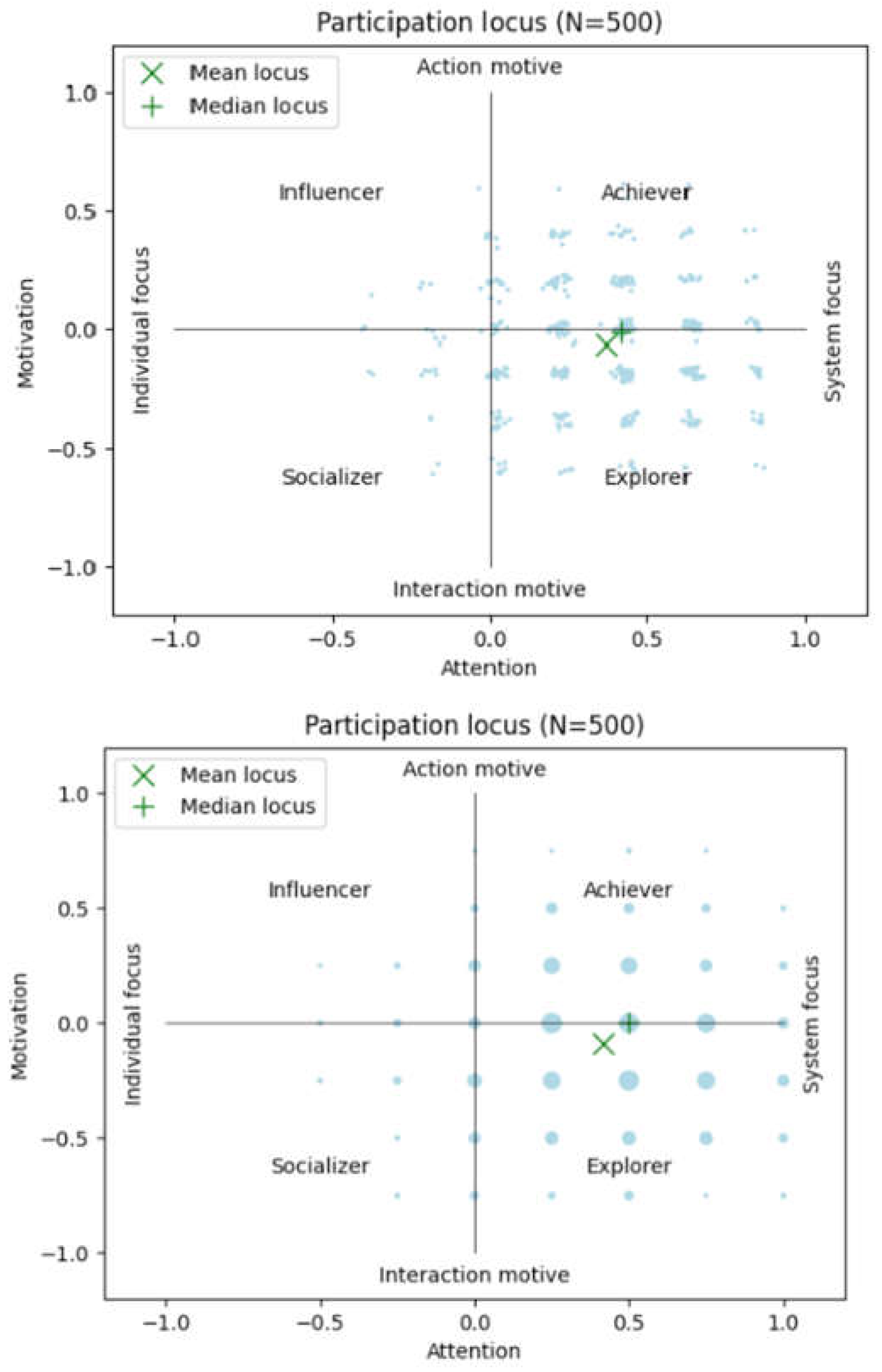

VIII. Results - Primary Survey

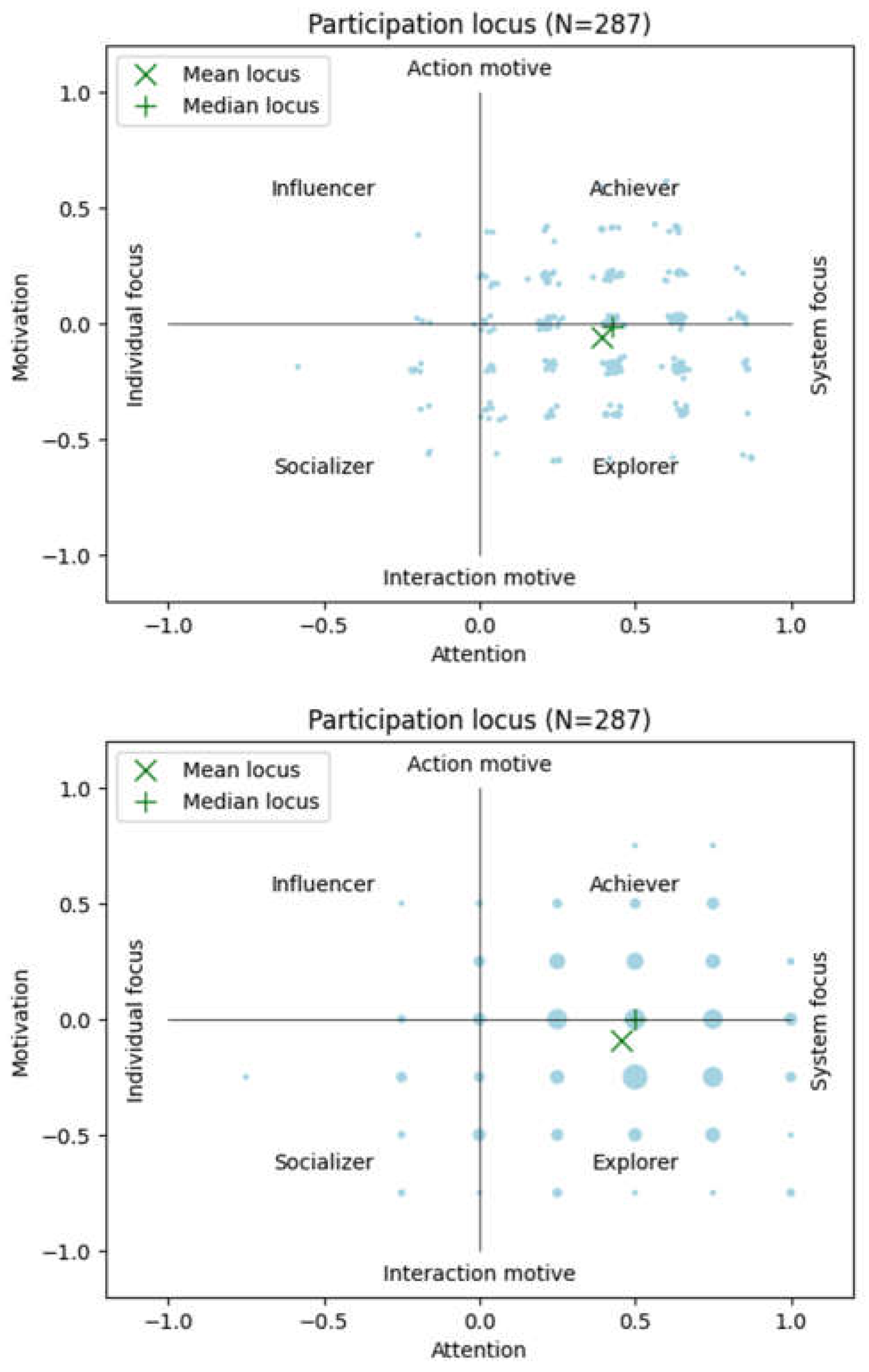

IX. Results - Re-Evluation Survey

| Personality Type | ||||

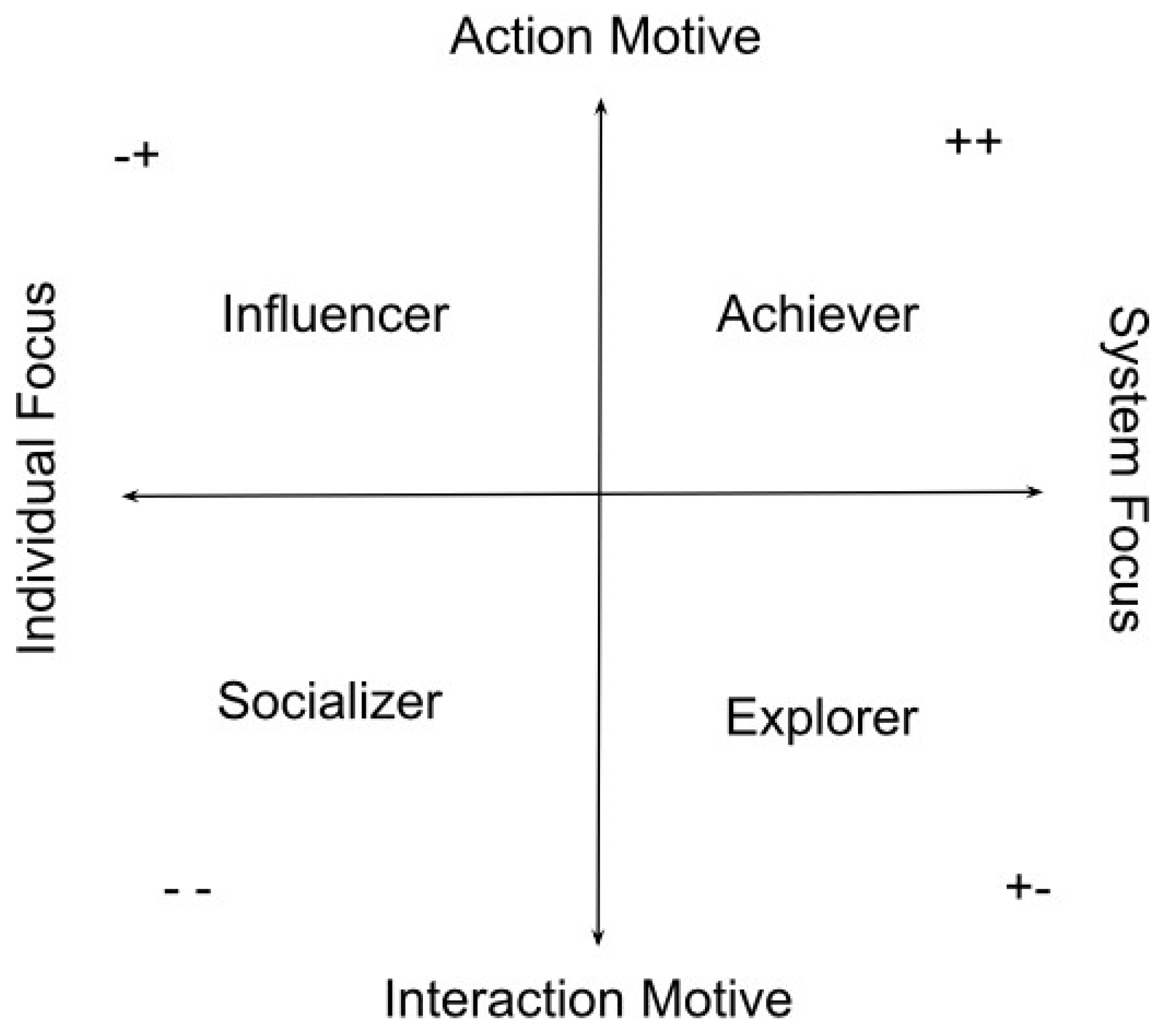

| Action Type | Explorer | Achiever | Influencer | Socializer |

| Explorer |

0.36 (0.00) |

0.25 (0.00) |

0.16 (0.12) |

0.22 (0.05) |

| Achiever | 0.34 (0.00) |

0.42 (0.00) |

0.19 (0.11) |

0.44 (0.00) |

| Influencer | 0.21 (0.00) |

0.21 (0.00) |

0.56 (0.00) |

0.34 (0.10) |

| Socializer | 0.08 (0.00) |

0.09 (0.00) |

0.07 (0.30) |

0.00 (0.99) |

X. Regression Analysis

XI. Conclusions

- (1)

- Age is a significant explanatory variable for some archetyped choices with the older age groups standing out the most.

- (2)

- Archetype stability is not fully consistent at the individ- ual level but it is remarkably consistent in the aggregate.

Appendix

- (1)

- Pursuing higher rankings for better rewards

- (2)

- Venturing into a new map in the game

- (3)

- Collaborating with fellow players in a team

- (4)

- Broadcasting my narrated gameplay

- (1)

- To join a fitness group to meet new people

- (2)

- To try a bootcamp with different fitness classes

- (3)

- To engage in daily workouts to advance in the fitness program

- (4)

- To recruit more members to join the fitness program

- (1)

- To rate and review the food online

- (2)

- To beat the food eating challenge

- (3)

- To try different dishes on the seasonal menu

- (4)

- To bring a friend to dine in together

- (1)

- I learn the game rules as you go

- (2)

- I cooperate with other players as much as possible

- (3)

- I dominate the board

- (4)

- I convince other players to adopt new rules for the game

- (1)

- I would share organizer’s post on your social media

- (2)

- I would listen to the band’s music from different time periods

- (3)

- I would join the fanbase group online

- (4)

- I would pass the band’s loyalty quiz

- (1)

- I navigate the game by trial and error

- (2)

- I share suggestions how to play the game

- (3)

- I aim to advance to the next level first

- (4)

- I befriend other players to learn and make connections

- (1)

- An option to encourage businesses to adopt the card

- (2)

- New and unique features of the card

- (3)

- Highest cashback on purchases

- (4)

- Ability to easily split bills with others

- (1)

- That it is a sold-out event

- (2)

- That it connects people

- (3)

- That it attracts new participants

- (4)

- That it is a new experience

- (1)

- Never

- (2)

- Less than once a week

- (3)

- Once a week

- (4)

- Several times a week

- (5)

- At least once a day

- (6)

- Multiple times a day

- (7)

- Most of the day

- (1)

- Not at all confident

- (2)

- Only a little confident

- (3)

- Somewhat confident

- (4)

- Very confident

- (1)

- Definitely yes

- (2)

- Probably yes

- (3)

- Probably not

- (4)

- Definitely not

- (1)

- Definitely yes

- (2)

- Probably yes

- (3)

- Probably not

- (4)

- Definitely not

- (1)

- Definitely yes

- (2)

- Probably yes

- (3)

- Probably not

- (4)

- Definitely not

- (1)

- Definitely yes

- (2)

- Probably yes

- (3)

- Probably not

- (4)

- Definitely not

- (1)

- I am a homeowner

- (2)

- I am a renter

- (3)

- Other:

- (1)

- 18 to 24

- (2)

- 25 to 34

- (3)

- 35 to 44

- (4)

- 45 to 54

- (5)

- 55 to 64

- (6)

- 65 or over

- (1)

- I choose to read the press release to learn about the largest camera in the world

- (2)

- I choose to compare your completion time of the survey with others

- (3)

- I choose to provide rating and feedback regarding the survey

- (4)

- I choose to connect with us on social media

References

- K. Salen and E. Zimmerman, “Rules of play: Game design fundamental,” 2004.

- Y. Weng, J. Yu, and R. Rajagopal, “Electrical power and energy system,” 2017.

- Sheth, K., Patel, D., & Swami, G. (2024). Strategic insights into vehicles fuel consumption patterns: Innovative approaches for predictive modeling and efficiency forecasting. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT), 13(6).

- Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2024). Strategic placement of charging stations for enhanced electric vehicle adoption in San Diego, California. Journal of Transportation Technologies, 14(1), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- R. Bartle, “Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players who suits muds,” 1996.

- N. Yee, “Motivations for play in online games,” 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. Hamari and J. Tuunanen, “Player types: A meta-synthesis,” 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Busch, E. Mattheiss, R. Orji, M. A, W. Hochleitner, M. Lankes, L. E. Nacke, and M. Tscheligi, “Personalization in serious and persuasive games and gamified interactions,” 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. F. Tondello, R. R. Wehbe, P. O. T. Dugas, L. E. Nacke, and N. K. Crenshaw, “Understanding player attitudes towards digital game objects,” 2016. [CrossRef]

- Swami, G., Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2025). From ground to grid: The environmental footprint of minerals in renewable energy supply chains. Computational Water, Energy, and Environmental Engineering, 14(1), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Swami, G., Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2024). PV capacity evaluation using ASTM E2848: Techniques for accuracy and reliability in bifacial systems. Smart Grid and Renewable Energy, 15(9), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, K., Patel, D., & Swami, G. (2024). Reducing electrical consumption in stationary long-haul trucks. Open Journal of Energy Efficiency, 13(3), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- T. Dohmen, A. Falk, D. Huffman, U. Sunde, J. Schupp, and G. Wagner, “Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences,” 2011. [CrossRef]

- O. Cecilia, K. Katrin, and F. Sudzina, “Gender and personality traits’ effect on self-perceived tech savviness,” 2017.

- L. Phan, C. Seyl, J. Chen-Sankey, J. Niederdeppe, M. Guy, K. Sterling, and K. Choi, “Exploring young adults’ beliefs about cigar smoking by susceptibility: A belief elicitation study,” 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Schmidt, “Shall we really do it again? the powerful concept of replication is neglected in the social sciences,” 2009. [CrossRef]

- H. Radder, “In and about the world: Philosophical studies of science and technology,” 1996.

- Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2024). Comprehensive examination of solar panel design: A focus on thermal dynamics. Smart Grid and Renewable Energy, 15(1), Article 2. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).