1. Introduction

With the improvement of living standards and increased awareness of dental health, an increasing number of individuals are seeking dental treatments (such as orthodontics, implants, and restorations) to ensure normal oral function and enhance their facial appearance [

1,

2,

3,

4]. According to a report on oral diseases [

5], nearly 90% of the global population experiences dental issues to varying degrees, with many requiring dental treatment. In clinical dentistry, Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) has become a commonly employed diagnostic method, offering essential information regarding the anatomical structure of teeth and the extent and severity of periapical tissue lesions.

In contrast to conventional X-ray images, which provide two-dimensional data, CBCT offers three-dimensional visualization of the area of interest. Moreover, high-resolution CBCT (approximately 0.1 mm) delivers more precise dental information. This level of precision proves advantageous for diagnosis, treatment planning, and the post-treatment assessment of patients with various oral conditions. CBCT’s capacity to provide comprehensive, three-dimensional views significantly aids in selecting appropriate treatment techniques and equipment for dental procedures.

While 3D dental model reconstruction offers substantial clinical advantages, the current practice predominantly involves manual annotation of CBCT images by experienced clinicians. This annotation process typically requires professionals to review hundreds of individual 2D tomographic images meticulously using specialized software. Consequently, it is a time-consuming endeavor, with each tooth, necessitating several hours of work and frequently introducing subjectivity into the process [

6].

To achieve automatic and objective tooth segmentation from these images, researchers have spent the last decade exploring various methods for crafting hand-engineered tooth segmentation features [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. These low-level descriptors and features are exceedingly sensitive to the intricate characteristics of dental CBCT images, such as the limited intensity contrast between teeth and the surrounding tissues. As a result, tedious manual intervention is often required for initialization or post-processing corrections. Deep learning has gained widespread acceptance in the domain of tooth segmentation [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, it typically demands substantial annotated datasets. The manual annotation of half-jaws by experienced professionals can be a time-consuming and labor-intensive task, often taking around 15 to 30 minutes per instance tooth [

17].

Recently, the deployment of Large AI Models (LAM) [

18] has exhibited remarkable performance across a range of downstream tasks. The Segmentation Any Model (SAM) [

19] serves as a foundational model renowned for its robust generalization capabilities. It holds significant potential and feasibility in addressing the labeling cost challenges associated with tooth segmentation [

20].

Nevertheless, the application of SAM still presents considerable challenges in the dental clinical practice. Primarily, 2D SAM necessitates a slice-by-slice methodology for processing volumetric images. This involves decomposing 3D data into individual two-dimensional slices, independent processing of each slice, and subsequent aggregation of the two-dimensional outcomes to generate a 3D prediction. As reported in [

20], the slice-by-slice method, by overlooking three-dimensional spatial relationships between slices, exhibits suboptimal performance when applied to three-dimensional medical images. Furthermore, clinical CBCT images are characterized by substantial size, for instance, dimensions like 672×688×688, whereas tooth structures within CBCT images are relatively diminutive. The current SAM model encounters difficulties when processing such extensive data volumes directly, demanding robust hardware capabilities.

However, the downsampling process involved in handling this challenge poses the risk of losing valuable tooth-related information. Moreover, at present, there have been no research endeavors to leverage SAM’s potent generalization capabilities in addressing the intricate issue of tooth annotation difficulties. In addition, the existing SAM network loses a lot of texture information and has poor segmentation performance for slender and small targets in medical images.

To this end, we propose a 3D-SAM with skip-connection network, which segments teeth by interacting with annotators. Firstly, considering that the dental structures constitute a relatively small portion of the entire CBCT image, we engage with annotators to delineate the ROI encompassing the teeth. This initial interaction enables us to accurately pinpoint the tooth region, which is then input into the model. Secondly, we introduce the SAM-MED3D model, offering the capability to segment teeth through a straightforward interactive annotation process using points or bounding boxes. Leveraging the predefined positions marked by annotation points, we identify the distinct connected regions within these positions, effectively achieving semantic-level segmentation. Finally, we use clinical data and ablation research to verify the effectiveness of the proposed method.

We have outlined our primary contributions as follows: 1. As far as we know, this work is the first attempt to apply SAM to three-dimensional tooth segmentation to help solve the problem of the high annotation cost of segmentation tasks in high-resolution images. 2. Through the utilization of the two-stage promptSAM approach, we have managed to lower hardware prerequisites while not bringing too much annotation workload. Meanwhile, by adding skip-connection, we keep more details of teeth to facilitate segmentation by SAM. 3. Our method greatly reduces the annotation cost and achieves competitive performance compared with the fully supervised baseline.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tooth Segmentation

Non-learning methods: [

2,

4,

5] implemented the level set method to track and separate teeth. Meanwhile, Ref [

3,

6] et al.. employed a slice-by-slice segmentation approach in a 2D transversal plane to segment teeth. In particular, [

10] utilized 2D tooth contours to automatically model the overall 3D tooth shape using a B-spline representation. [

7,

8,

9] simulated CBCT 3D images and then used graph cuts to obtain an optimal image segmentation through a probability model. However, these methods require manual initialization or correction and are particularly sensitive to parameters or data, making it difficult to assist with tooth CBCT annotation.

Learning-based method: Toothnet [

11], proposed by Cui et al., is the first instance tooth segmentation method based on deep learning. They demonstrate the powerful advantages and good performance of deep learning networks when applied to big data for joint segmentation of alveolar bone and teeth [

13]. [

12] improves segmentation accuracy by jointly predicting teeth and tooth center points. Li et al. [

14] and Wang et al. [

16] consider the surgical scheme of root canal treatment and adopt a semantic segmentation structure for the joint segmentation of root canals and teeth. Li et al. [

15] also propose a multi-task structure based on Swin-Transformer. Additionally, there are studies on tooth segmentation based on Mesh [

21,

22] and Point Cloud [

23,

24] instead of voxels, which have shown better tooth segmentation results. However, deep learning models require large amounts of data for training, resulting in significant manual annotation costs. Xie et al. [

25] attempted to reduce the cost of tooth annotation by using weakly supervised learning, reducing the annotation level from voxel to box. However, in order to achieve fine voxel-level segmentation results, this method relies on the prior knowledge of tooth shape and a combination of the level set and Variational Inference methods for post-processing tasks.

2.2. SAM

SAM [

9] is equipped with an impressive pre-training of 1 billion masks, making it a general visual foundation model for fast image segmentation. It demonstrates impressive few-shot performance across various visual tasks. Due to its versatility, SAM has been applied to several applications, such as subtitles, data annotation, modification, and tracking, when combined with other methods [

26]. FGVP [

42] incorporates SAM to achieve zero-shot fine-grained visual prompting, MedSAM [

43] adapts SAM into a large-scale medical dataset to build a medical foundation model, and some methods [

44] utilize SAM to deal with the weakly-supervised semantic segmentation problem. However, SAM is an interactive segmentation method that heavily relies on human prompts.

2.3. SAM in Medical

The success of SAM [

26] in natural images has prompted researchers to explore its applicability in the field of medical imaging, particularly in 3D medical image segmentation. This poses a significant challenge in medical image analysis. SAM3D [

28] utilizes the native SAM encoder as its image encoder and processes voxel images piece by piece to obtain a 3D representation. This representation is then interpreted by a 3D decoder to generate masks. MedLSAM [

29] adopts SAM in a two-stage model and improves the segmentation accuracy by providing accurate hints through model localization. SAMMed [

30] innovatively proposes a pipeline that generates 3D hints from 2D points. Additionally, other methods attempt to design a 3D adapter to fine-tune SAM. MSA [

31] retains all the weights of the original SAM and introduces a space and depth adapter specifically designed for processing 3D spatial information. However, these methods rely on adapters (with only some trainable parameters) to encode important 3D information, which may not be conducive to extracting spatial information in 3D. In particular, Sam-Med3D [

32] is the first foundational model for medical images based on 3D VIT, however, the performance of small targets (such as tumors) and slender structures (e.g., trachea) may be degraded due to the image compression approach used.

2.4. Skip Connection

Skip connection, also known as shortcut connection, has been studied for a long time. In 1948, Wiener introduced negative feedback into the control system and proposed Cybernetics [

35,

36,

37]. Negative feedback refers to the output of a system being fed back to the input to promote the system’s stability. The use of short skip connections can help alleviate the degradation problem by making it easier to learn residual feature maps compared to directly fitting a desired underlying feature mapping [

35]. Meanwhile, long skip connections bridge the gap between detailed and semantic information, demonstrating their effectiveness in many tasks.

Short skip connections are integrated into a 3D U-Net architecture [

43]. The encoder directly embeds residual blocks, and the decoder receives feature maps from the encoder through long skip connections. Due to the combination of short and long skip connections, the 3D U-Net’s training efficiency and feature learning are improved by enhancing the information aggregation within the U-Net, both locally and globally

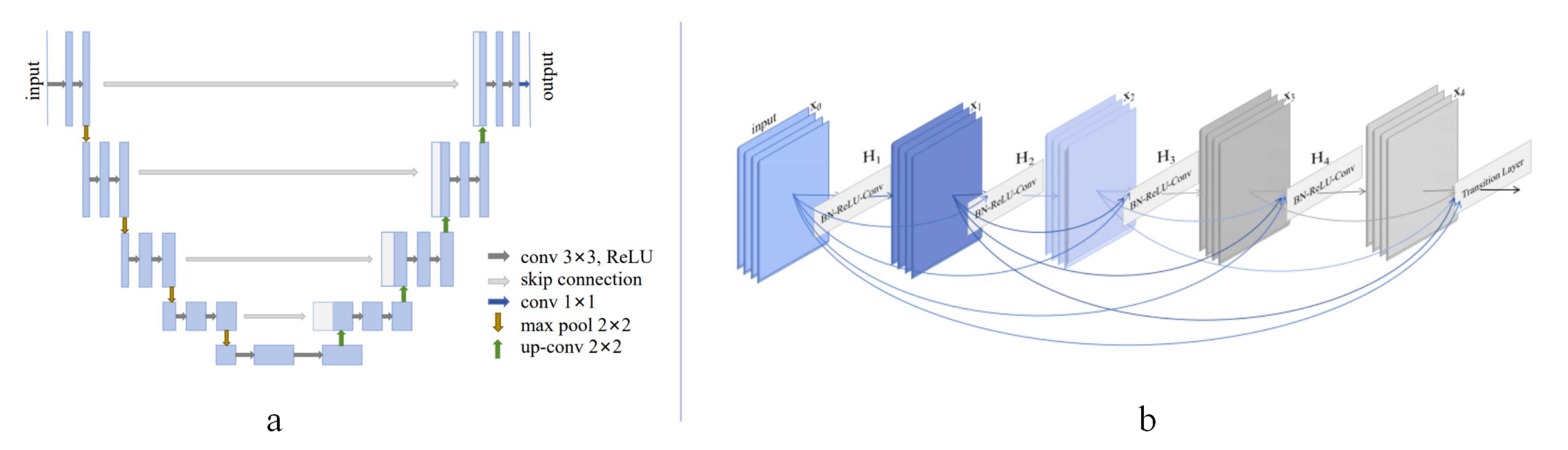

Figure 1(a). In [

38], a type of densely connected convolutional network (DenseNet) was proposed

Figure 1(b). The DenseNet connects each layer to every other subsequent layer in a feed-forward fashion, including both short and long skip connections. Compared to ResNet, DenseNet makes full use of the feature maps from each layer to ensure maximum information flow between layers in the network. Two of its compelling advantages are strengthened feature propagation and encouraged feature reuse. Additionally, many works also utilize short and long skip connections for various tasks. For instance, the ResUNet-a [

39] employs a U-Net backbone combined with residual blocks, atrous convolutions, and pyramid scene parsing pooling. The proposal of volumetric ConvNets [

41] included mixed residual connections for prostate segmentation from 3D MR Images. In summary, it is more effective to integrate both short and skip connections for residual feature learning. However, it can be challenging to determine the optimal format to combine them for a specific task.

3. Materials and Methods

Let’s review SAM’s architecture for two-dimensional natural images, which can be divided into three core components:

Image Encoder: SAM utilizes a pre-trained Vision Transformer (ViT) [

33], specifically an MAE [

34] pre-trained the ViT to extract image representations. This component employs 2D patch embeddings along with learnable position encodings to transform the input image into image embeddings.

Prompt Encoder: This module is designed to handle both sparse prompts (points, boxes) and dense prompts (masks). Sparse prompts are represented using frozen 2D absolute positional encodings and then combined with learned embeddings specific to each prompt type. Dense prompts, on the other hand, are encoded using a 2D convolution neck to generate dense prompt embeddings.

Mask Decoder: SAM adopts a lightweight structure to efficiently map the image embedding with a set of prompt embeddings to produce an output mask. Each transformer layer consists of four steps: (1) self-attention on tokens, (2) cross-attention between tokens and the image embedding, (3) token updates using a point-wise MLP, and (4) cross-attention that updates the image embedding with prompt details. After processing through the transformer layers, the feature map undergoes up-sampling and is subsequently converted into segmentation masks using an MLP.

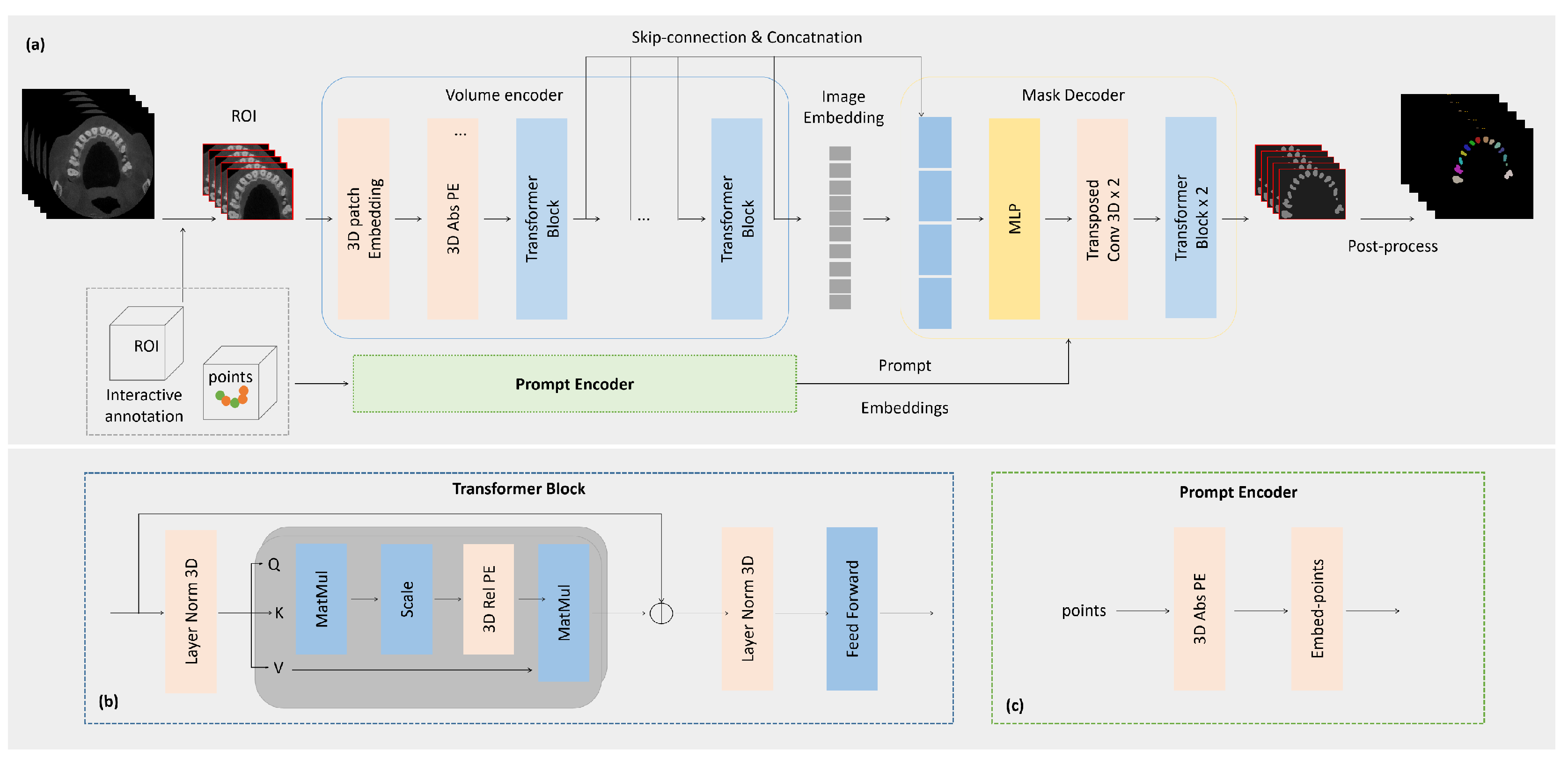

3.1. The proposed network

Inspired by [

29,

32], for the task of tooth segmentation in high-resolution CBCT images, we adopt SAM with a two-stage prompt mechanism and skip-connection. The network structure can be mainly divided into three parts: 1. Two-stage prompt; 2. ToothSC-SAM:A 3D-SAM with skip-connection network for tooth Segmentation; 3. Post-processing for tooth labeling and padding to original CBCT size. The proposed model structure is illustrated in

Figure 2 below:

3.2. Two-Stage Prompt

In previous studies, most 3D tooth segmentation models utilized a two-stage method due to the high resolution of CBCT, which would require significant hardware and computational resources if directly input into the model. Additionally, direct segmentation in CBCT images often yielded poor performance as teeth occupy a relatively small proportion. Therefore, previous models, such as Ref [

11,

13,

14,

15], employed a rough segmentation approach based on full supervision information to extract the ROI for the teeth and subsequently performed fine segmentation within this region. However, training such a rough segmentation model also incurred significant annotation costs as the entire tooth had to be labeled. Moreover, the quality of rough segmentation directly impacted the performance of fine segmentation. If the result of coarse segmentation is poor, fine segmentation also becomes a failure. We only need to request an ROI area box because of the interactive prompt mechanism, which can achieve this goal perfectly without increasing the number of comments. Finally, we record the location information of all prompts.

3.3. 3D-SAM with Skip-Connection

We have made several modifications to the 2D components of the SAM model to adapt it to volumetric medical images. Our modified model incorporates a holistic 3D structure that enables direct capture of spatial information. In the image encoder, we start by embedding patches using a 3D convolution with a kernel size of (16, 16, 16). These embedded patches are then combined with a learnable 3D absolute Positional Encoding (PE), which extends an additional dimension to the 2D PE of SAM. This encoding enables the model to encode spatial relationships in a 3D context. The patch embeddings are subsequently fed into 3D attention blocks. To better capture spatial details, we introduce a 3D relative PE into the Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) module of SAM within the transformer block. This allows our model to directly capture spatial nuances and encode them into the attention mechanism. In the prompt encoder, we handle sparse prompts by leveraging 3D position encodings, which enable the model to represent 3D spatial information. For dense prompts, we utilize 3D convolutions to process them.Likewise, our 3D Mask Decoder integrates 3D upscaling procedures using 3D transposed convolution. This ensures that the generated masks align with the spatial dimensions of the original volumetric medical images. However, although the SAM-Med3D model, which is based on ViT, is able to capture the global context information of the image, it faces certain difficulties in segmenting complex-shaped objects, especially elongated or small targets, in the edge and detail regions. On the other hand, UNet-based models [

14] leverage the skip-connection pattern to handle local features and details effectively. By combining the skip-connection and SAM together, we can fully exploit their respective advantages, thereby improving the accuracy, localization, and detail-capturing capabilities of image segmentation.

3.4. Loss Function

We use the combination of dice loss and weight entropy loss, and the total loss function is defined as follows:

where y represents the true ground truth, ypred represents the predicted label of the model, and w represents the category weight. The category weight can be determined based on the number of pixels in each category in the dataset in order to balance the significance of different categories.

Dice loss primarily focuses on capturing the spatial overlap between the predicted mask and the target mask. By incorporating the dice loss into the overall loss function, the model is incentivized to generate segmentation results that are more accurate and precise. In the context of medical image segmentation, we often encounter the issue of imbalanced categories, wherein the number of pixels belonging to certain categories greatly surpasses those of others. This leads the model to prioritize predicting the larger categories and overlooking the details of smaller categories. Weight Entropy loss addresses this problem by penalizing uncertain and fuzzy predictions, effectively encouraging the network to generate sharper predictions. Additionally, it ensures better segmentation performance for smaller targets by balancing the importance of different categories.

3.5. Post-Processing

Firstly, we label the connected regions of the image using the recorded position information of the points. This enables us to achieve semantic-level tooth segmentation. Then, through the position information of ROI, the semantic segmentation effect of teeth is filled with zero to restore to the original size, so as to realize the effect of tooth segmentation and labeling in high-resolution CBCT images.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Clinical Data

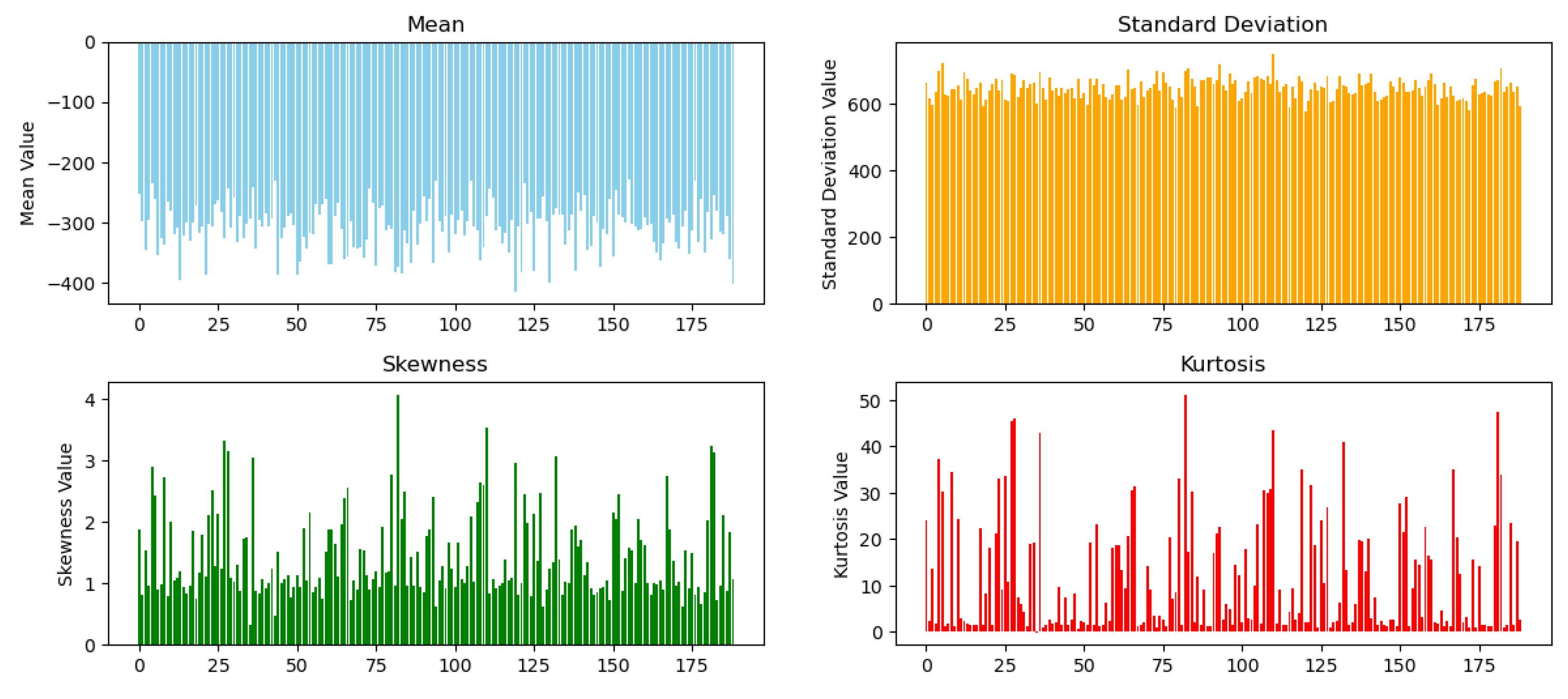

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of my institution. A total of 176 CBCT imaging data were obtained from the Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University between 2019 and 2022

Figure 3. These cases were selected based on dental symptoms recognized as indications for oral CBCT by professional stomatologists. All CBCT scans were carefully reviewed by two experienced examiners specialized in endodontics, each having 10 years of clinical experience. The manual segmentation of teeth was performed using MITK software. In instances where there were disagreements between the two examiners, a joint discussion was held to reach a consensus. The results of this review process were considered as the ground truth for further analysis. The reliability of the observers was evaluated using Cohen’s kappa test. The data set allocation ratio is training: verification: testing = 130: 32: 27.

4.2. Data Preprocessing

Prior to inputting a 3D CBCT image into the deep learning network, several pre-processing stages were undertaken. Firstly, as the physical resolution of the CBCT images collected varied from 0.2 to 1.0 mm, all images were normalized to an isotropic resolution of 0.4 × 0.4 × 0.4 mm³, taking into account the balance between computational efficiency and segmentation accuracy. In line with the standard image processing protocol in deep learning, voxel-wise intensities were normalized to the interval [0, 1]. Furthermore, in order to minimize the impact of extreme values, particularly in areas with metal artifacts, the intensity values of each CBCT scan were clipped to the range [0, 2500] before intensity normalization.

4.3. Implementation

After extracting the ROI from all CBCT images in the first stage, the clipping patch size in the second stage is set to 128*128*128 to ensure the inclusion of the entire foreground tooth object. Our method is implemented in PyTorch and trained on six NVIDIA A6000 GPUs, each with 64GB of memory. We use the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e-4, and initialize and fine-tune the weights [

32] for 200 epochs. The learning rate is reduced to 0.5 every 20 epochs. During our parallel training, the total batch size is set to 6, and the interval for aggregation and update of the gradient accumulation strategy is set to every 20 steps, with a weight decay of 0.1. The random seed is set to 2023 to prevent randomness during model training.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

Similar to previous studies [

7,

9,

10], we used standard segmentation metrics to evaluate the performance of our method. These metrics include voxel classification accuracy metrics such as the dice coefficient, jaccard similarity coefficient (jaccard), and sensitivity. Additionally, we utilized surface (edge) distance metrics such as the 95% Hausdorff distance (HD95) and average surface distance (ASD).

The dice coefficient is robust to unbalanced datasets, as it is not affected by the uneven distribution of categories, such as the small proportion of tooth pixels in the entire CBCT pixel set. The jaccard coefficient directly indicates the accuracy and coincidence of segmentation results. Sensitivity represents the ratio of true positives to the sum of true positives and false negatives. The ASD metric is highly sensitive to the accuracy of the segmentation boundary. Therefore, it can be used to evaluate the quality of segmentation boundaries. On the other hand, HD95 provides detailed information about the boundary quality of segmentation results and has low sensitivity to outliers. These metrics are calculated as follows:

where TP (True Positives) is the number of pixels correctly divided into positive categories. FP (False Positives) is the number of pixels that have been wrongly divided into positive categories. FN (False Negatives) is the number of pixels that are not correctly divided into positive categories.

where D(S, G) represents the distance from each surface point in the segmentation result S to the nearest real segmentation G boundary, and P stands for summation operation, which calculates the sum of distances of all surface points. N represents the total number of surface points.

where H(S, G) represents the Hausdorff distance from the segmentation result S to the real segmentation G. H(G, S) represents the Hausdorff distance from the real segmentation G to the segmentation result S. Max means to take the larger value between the two.

4.5. Performance comparison of different methods

We compared our proposed method with the UNet-based model [

10], as well as a segmentation method based on the transformer [

15] and the SAM-Med3D method applied to downsampled CBCT images. To ensure fair comparison, we only validated the backbone networks of [

10,

15]. Additionally, due to variations in performance across different combinations of post-processing methods and models, we focused on evaluating and visualizing the performance of tooth labeling for all methods.

Table 1 presents a performance comparison of our method with other approaches in terms of tooth segmentation. The UNet-based method exhibits promising results in tooth segmentation under fully-supervised settings, achieving pixel classification accuracy metrics of Dice, Jaccard, and Sensitivity are 89.32%, 80.04%, and 86.41%, respectively. Furthermore, the integration of the transformer model, which possesses powerful feature extraction capabilities, further enhances performance by leveraging global attention. Compared to the UNet-based model, the transformer-based model achieves a 2.5% improvement in the Dice coefficient while obtaining better edge segmentation through global information constraints. Surface distance metrics, including HD95 and ASD, are measured at 2.41mm and 0.38mm, respectively. Compared to the UNet-based model, our method demonstrates a decrease of 0.42 and 0.09 in HD95 and ASD, respectively. However, the SAM-Med3D method, which also utilizes the transformer as the backbone, exhibits poor tooth segmentation capability when directly applied to dental CBCT images. This could be attributed to the loss of spatial information for small objects caused by the downsampling process. Additionally, due to the interactive prompt mechanism, the annotation positions have a direct impact on the segmentation accuracy of the SAM-Med3D model. Therefore, it is challenging for the SAM network with a cylindrical ViT model as the backbone to achieve satisfactory accuracy for thin and small objects. Our proposed approach effectively addresses these issues by leveraging a two-stage prompt mechanism and skip connections. The Dice coefficient is improved from 76.99% to 83.88%. Moreover, our model only requires ROI annotations and point prompts, reducing the annotation time from several tens of hours to just a few minutes while achieving performance that surpasses 90% of the fully supervised baseline.

4.6. Ablation Study

To further validate the effectiveness of each module, we conducted ablation experiments, including using the SAM-Med3D model directly, adding a two-stage prompt to the SAM-Med3D model, adding skip connections to the SAM-Med3D model, and the final model. Firstly, the results of the comparative experiments in

Table 2 demonstrate that the SAM-Med3D model with a two-stage prompt achieves better performance compared to the SAM-Med3D model with directly downsampled images. This is because downsampling the dental CBCT images leads to a significant loss of spatial information, and the two-stage prompt mechanism effectively alleviates this issue. Additionally, while the shallow layers of the ViT model used in the SAM network for natural images are often considered redundant, in medical images, the shallow layers often retain essential texture and detail information required for segmentation. Therefore, adding skip connections to the SAM-Med3D model improves the segmentation performance.

Furthermore, it can be observed that adding skip connections yields superior results compared to adding the two-step prompt mechanism, as skip connections partly mitigate the loss of spatial information. Finally, by combining the advantages of the two-step prompt and skip connections, our 3D-SAM with skip connections based on two-stage prompts achieves the best performance.

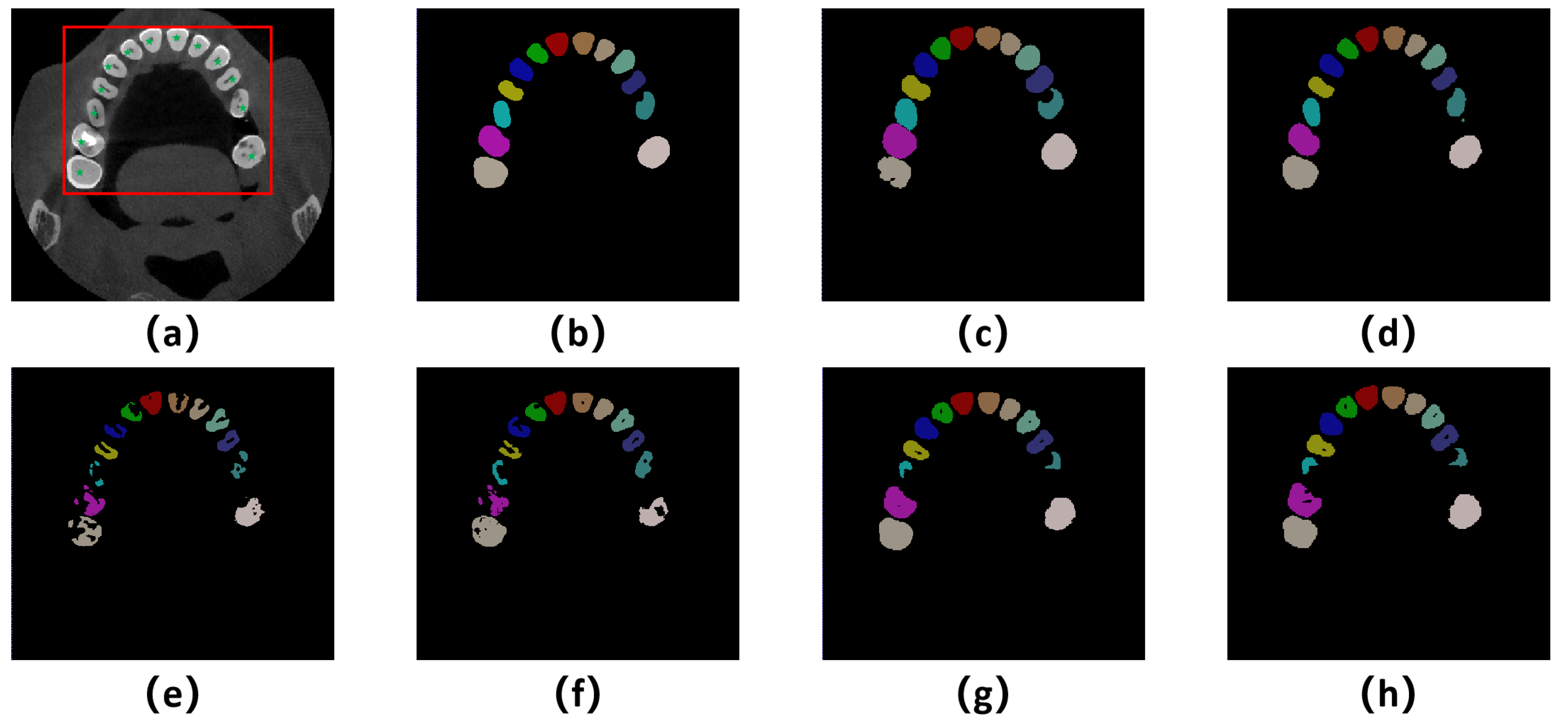

From the segmentation visualizations in

Figure 4 (e), it can be observed that directly downsampling the dental CBCT images for the application of the SAMMed-3D model leads to poor segmentation accuracy. There are evident segmentation errors in regions with prominent teeth, which is likely caused by the spatial compression during downsampling. In contrast,

Figure 4 (f) and

Figure 4 (g) demonstrate that both of the proposed methods show significant improvements compared to

Figure 4 (c), and our model achieves even better results by combining the two approaches. Additionally, it can be noted that our method still exhibits a certain gap compared to the fully supervised approach. However, post-processing techniques such as extracting the largest connected component, applying a watershed algorithm, and employing dilation and erosion operations can optimize the segmentation results to be competitive. Before post-processing, it can be observed that our method presents holes in the root canal area, which is attributed to the fact that the SAM model excels at distinguishing teeth and root canals due to its powerful feature recognition capability. However, the ground truth does not distinguish between teeth and root canals, which poses a significant challenge in determining the performance of our method. Nevertheless, this also indicates the potential of the SAM model in simultaneously segmenting teeth and root canals.

5. Discussion

A SAM-Med3D structure based on two-stage prompt and combined prompt information for post-processing was proposed for dental segmentation. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to achieve improved segmentation performance for small objects at high resolution through the two-stage prompt mechanism. This study addresses the challenge of the immense cost of clinical manual annotation by using an interactive annotation approach for tooth segmentation on CBCT images. This approach provides a valuable reference for reducing the volume of voxel segmentation labels in high-resolution images. Additionally, utilizing the positional information of the prompt for tooth naming can assist downstream tasks such as lesion classification [

15]. Therefore, this research can potentially serve as a feasible preliminary solution for tooth diagnosis studies based on CBCT, dental surgery robot path planning, and postoperative prediction.

CBCT images provide more accurate 3D spatial information of teeth due to their high resolution. However, annotating each tooth precisely on a CBCT image can take several hours, let alone acquiring the large volume of annotated data required by data-hungry deep learning models. Additionally, due to the large size of CBCT images, the proportion of teeth is low. Therefore, directly segmenting teeth on the original CBCT image often yields unsatisfactory performance. Moreover, inputting the massive 3D CBCT data into the model requires powerful hardware support, while downsampling results in information loss, especially for the segmentation of small targets like teeth. This study demonstrates that the two-stage prompt mechanism, based on simple ROI annotation, provides more accurate ROI regions and achieves better tooth segmentation results compared to directly compressing the images.

Although our model lags behind fully supervised approaches in terms of performance, we achieve over 90% of the performance of fully supervised models by annotating only a single ROI box and N points or boxes on the teeth, reducing annotation time from several tens of hours per person to just a few minutes through interactive annotation. However, this study has some limitations. Firstly, it includes data from a single center with only a limited amount of data. In future studies, we plan to collect data from different centers and conduct independent validation. Furthermore, this study still requires manual annotation by annotators, which imposes a clinical burden. In subsequent research, we will consider methods such as automatic identification of prompts [

30] to further reduce the annotation workload. Finally, this study focuses only on tooth segmentation, while our future goal is to build a comprehensive dental model for tasks such as comprehensive tooth model reconstruction and tooth lesion identification and classification.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we propose a novel approach based on the two-stage prompt mechanism in SAM-Med3D to significantly reduce annotation costs for tooth segmentation in CBCT images. Experimental results demonstrate that our method effectively combines the prompt mechanism in SAM to handle high-resolution images and achieves tooth segmentation and labeling with minimal annotation requirements. The experimental metrics and visual validation support the effectiveness and efficiency of our proposed approach.

References

- S. T. Tresna, N. Anggriani, H. Napitupulu, and W. M. A. W. Ahmad. Deterministic Modeling of the Issue of Dental Caries and Oral Bacterial Growth: A Brief Review. Mathematics, 12(14):2218, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Mitić, N. Vitković, M. Trajanović, F. Górski, A. Păcurar, C. Borzan, and R. Păcurar. Utilizing Artificial Neural Networks for Geometric Bone Model Reconstruction in Mandibular Prognathism Patients. Mathematics, 12(10):1577, 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. Cojocariu-Oltean, M. S. Tripa, I. Bărăian, D. I. Rotaru, and M. Suciu. About Calculus Through the Transfer Matrix Method of a Beam with Intermediate Support with Applications in Dental Restorations. Mathematics, 12(23):3861, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Y. Liu, J. J. Liou, and S. W. Huang. Exploring the Barriers to the Advancement of 3D Printing Technology. Mathematics, 11(14):3068, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Jin, I. B. Lamster, J. S. Greenspan, N. B. Pitts, C. Scully, and S. Warnakulasuriya. Global burden of oral diseases: emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Diseases, 22(7), 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Qian, J. Yang, S. Tang, G. Chen, and J. Yan. Addressing Noisy Pixels in Weakly Supervised Semantic Segmentation with Weights Assigned. Mathematics, 12(16):2520, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Changjian Li, Zhiming Cui, and Wenping Wang. Toothnet: Automatic tooth instance segmentation and identification from cone beam ct images. IEEE, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Xiyi Wu, Huai Chen, Yijie Huang, Huayan Guo, and Lisheng Wang. Center-sensitive and boundary-aware tooth instance segmentation and classification from cone-beam ct. In 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zhiming Cui, Yu Fang, Lanzhuju Mei, Bojun Zhang, Bo Yu, Jiameng Liu, Caiwen Jiang, Yuhang Sun, Lei Ma, Jia-Bin Huang, Yang Liu, Yue Zhao, Chunfeng Lian, Zhongxiang Ding, Min Zhu, and Dinggang Shen. A fully automatic ai system for tooth and alveolar bone segmentation from cone beam ct images. Nature Communications, 13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Shangxuan Li, Yu Du, Li Ye, Chichi Li, Yanshu Fang, Cheng Wang, and Wu Zhou. Teeth and root canals segmentation using zxyformer with uncertainty guidance and weight transfer. In 2023 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), pages 1–5, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jia Qin Ngu, Humaira Nisar, and Chi-Yi Tsai. MSTransBTS—A Novel Integration of Mamba with Swin Transformer for 3D Brain Tumour Segmentation. Mathematics, 13(7):1117, 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. Nazzal, K. Thurnhofer-Hemsi, and E. López-Rubio. Improving Medical Image Segmentation Using Test-Time Augmentation with MedSAM. Mathematics, 12(24):4003, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Yang, Y. Wang, Y. Ma, and H. Yang. A Multi-Scale Interpretability-Based PET-CT Tumor Segmentation Method. Mathematics, 13(7):1139, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, S. Zhou, K. Li, J. Yin, and J. Huang. A Hybrid Framework for Referring Image Segmentation: Dual-Decoder Model with SAM Complementation. Mathematics, 12(19):3061, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shangxuan Li, Chichi Li, Yu Du, Li Ye, Yanshu Fang, Cheng Wang, and Wu Zhou. Transformer-based tooth segmentation, identification and pulp calcification recognition in cbct. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, pages 706–714. Springer, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yiwei Wang, Wenjun Xia, Zhennan Yan, Liang Zhao, Xiaohe Bian, Chang Liu, Zhengnan Qi, Shaoting Zhang, and Zisheng Tang. Root canal treatment planning by automatic tooth and root canal segmentation in dental cbct with deep multi-task feature learning. Medical Image Analysis, 85:102750, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J Hao, W Liao, YL Zhang, J Peng, Z Zhao, Z Chen, BW Zhou, Y Feng, B Fang, ZZ Liu, et al. Toward clinically applicable 3-dimensional tooth segmentation via deep learning. Journal of dental research, 101(3):304–311, 2022. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Gpt-4 technical report, 2023.

- Alexander Kirillov, Eric Mintun, Nikhila Ravi, Hanzi Mao, Chloe Rolland, Laura Gustafson, Tete Xiao, Spencer Whitehead, Alexander C Berg, Wan Yen Lo, et al. Segment anything. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.02643, arXiv:2304.02643, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Maciej A Mazurowski, Haoyu Dong, Hanxue Gu, Jichen Yang, Nicholas Konz, and Yixin Zhang. Segment anything model for medical image analysis: an experimental study. Medical Image Analysis, 89:102918, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tai-Hsien Wu, Chunfeng Lian, Sanghee Lee, Matthew Pastewait, Christian Piers, Jie Liu, Fan Wang, Li Wang, Chiung-Ying Chiu, Wenchi Wang, et al. Two-stage mesh deep learning for automated tooth segmentation and landmark localization on 3d intraoral scans. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 41(11):3158–3166, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zuozhu Liu, Xiaoxuan He, Hualiang Wang, Huimin Xiong, Yan Zhang, Gaoang Wang, Jin Hao, Yang Feng, Fudong Zhu, and Haoji Hu. Hierarchical self-supervised learning for 3d tooth segmentation in intra-oral mesh scans. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 42(2):467–480, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Farhad Ghazvinian Zanjani, David Anssari Moin, Bas Verheij, Frank Claessen, Teo Cherici, Tao Tan, et al. Deep learning approach to semantic segmentation in 3d point cloud intra-oral scans of teeth. In International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, pages 557–571. PMLR, 2019.

- Zhiming Cui, Changjian Li, Nenglun Chen, Guodong Wei, Runnan Chen, Yuanfeng Zhou, Dinggang Shen, and Wenping Wang. Tsegnet: An efficient and accurate tooth segmentation network on 3d dental model. Medical Image Analysis, 69:101949, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ruicheng Xie, Yunyun Yang, and Zhaoyang Chen. Wits: Weakly supervised individual tooth segmentation model trained on box-level labels. Pattern Recognition, 133:108974, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chaoning Zhang, Sheng Zheng, Chenghao Li, Yu Qiao, Taegoo Kang, Xinru Shan, Chenshuang Zhang, Caiyan Qin, Francois Rameau, Sung-Ho Bae, et al. A survey on segment anything model (sam): Vision foundation model meets prompt engineering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.06211, 2023. arXiv:2306.06211, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tianrun Chen, Lanyun Zhu, Chaotao Ding, Runlong Cao, Shangzhan Zhang, Yan Wang, Zejian Li, Lingyun Sun, Papa Mao, and Ying Zang. Sam fails to segment anything?–sam-adapter: Adapting sam in underperformed scenes: Camouflage, shadow, and more. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.09148, 2023. arXiv:2304.09148, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nhat-Tan Bui, Dinh-Hieu Hoang, Minh-Triet Tran, and Ngan Le. Sam3d: Segment anything model in volumetric medical images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.03493, 2023. arXiv:2309.03493, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wenhui Lei, Xu Wei, Xiaofan Zhang, Kang Li, and Shaoting Zhang. Medlsam: Localize and segment anything model for 3d medical images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.14752, 2023. arXiv:2306.14752, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chenglong Wang, Dexuan Li, Sucheng Wang, Chengxiu Zhang, Yida Wang, Yun Liu, and Guang Yang. A medical image annotation framework based on large vision model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.05617, 2023. arXiv:2307.05617, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Junde Wu, Rao Fu, Huihui Fang, Yuanpei Liu, Zhaowei Wang, Yanwu Xu, Yueming Jin, and Tal Arbel. Medical sam adapter: Adapting segment anything model for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.12620, 2023. arXiv:2304.12620, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Haoyu Wang, Sizheng Guo, Jin Ye, Zhongying Deng, Junlong Cheng, Tianbin Li, Jianpin Chen, Yanzhou Su, Ziyan Huang, Yiqing Shen, et al. Sammed3d. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.15161, 2023. arXiv:2310.15161, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kaiming He, Xinlei Chen, Saining Xie, Yanghao Li, Piotr Dollár, and Ross Girshick. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 16000–16009, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Alexey Dosovitskiy, Lucas Beyer, Alexander Kolesnikov, Dirk Weissenborn, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Mostafa Dehghani, Matthias Minderer, Georg Heigold, Sylvain Gelly, et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929, 2020. arXiv:2010.11929, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Xu, X. Wang, X. Wu, X. Leng, and Y. Xu. Development of skip connection in deep neural networks for computer vision and medical image analysis: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01725, 2024. arXiv:2405.01725, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Drozdzal, E. Vorontsov, G. Chartrand, S. Kadoury, and C. Pal. The importance of skip connections in biomedical image segmentation. In International Workshop on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis, pages 179–187, 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Wiener. Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. MIT Press, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Huang, Z. Liu, L. Van Der Maaten, and K. Q. Weinberger. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., pages 4700–4708, 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Xu, Y. Rathi, J. A. Camprodon, H. Cao, and L. Ning. Rapid whole-brain electric field mapping in transcranial magnetic stimulation using deep learning. Plos One, 16(7):e0254588, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. I. Diakogiannis, F. Waldner, P. Caccetta, and C. Wu. ResUNet-a: A deep learning framework for semantic segmentation of remotely sensed data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens., 162:94–114, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Yu, X. Yang, H. Chen, J. Qin, and P. A. Heng. Volumetric ConvNets with mixed residual connections for automated prostate segmentation from 3D MR images. In Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., volume 31, number 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Yang, Y. Wang, X. Li, X. Wang, and J. Yang. Fine-grained visual prompting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36:24993–25006, 2023.

- J. Ma, Y. He, F. Li, L. Han, C. You, and B. Wang. Segment anything in medical images. Nature Communications, 15(1):654, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P.-T. Jiang and Y. Yang. Segment anything is a good pseudo-label generator for weakly supervised semantic segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.01275, 2023. arXiv:2305.01275, 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).