1. Introduction

In 2008, it was shown for the first time that short unmodified antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides саn be used as contact insecticides (Oberemok 2008). Oligonucleotide insecticides (briefly, olinscides or DNA insecticides) as a new class of insecticides has its own peculiar characteristics. Olinscides are short unmodified antisense DNA fragments that use pre-RNA and rRNA of pests as target and act through DNA containment mechanism (first step: ‘arrest’ of target rRNA, block of functioning of ribosomes accompanied with hypercompensation of expression of rRNA; second step: degradation of target rRNA by RNase H or other specific enzymes) (Gal’chinsky et al. 2024; Oberemok and Gal’chinsky 2024; Oberemok et al. 2024a). A target rRNA and an olinscide interlock and in the presence of specific RNase resemble zipper mechanism performed by DNA-RNA duplex (‘genetic zipper’ method) (Oberemok et al. 2024b). Use of insect pest pre-rRNA and rRNA as target leads to high efficiency of oligonucleotide insecticides, since pre-rRNA and rRNA comprise 80 % of all RNA in the cell (Oberemok et al. 2024a). Thousands of different mRNAs make up only 5 % of all RNA and use of pre-rRNA and rRNA for targeting substantially increases signal-to-noise ratio, ca. 105:1 (rRNA vs. random mRNA) (Palazzo and Lee 2015). Other cell RNA, in both target and non-target organisms, due to much lower concentration, will be much less susceptible to antisense oligonucleotides, even if oligonucleotide insecticides will possess perfect complementarity to it (Oberemok et al. 2024c).

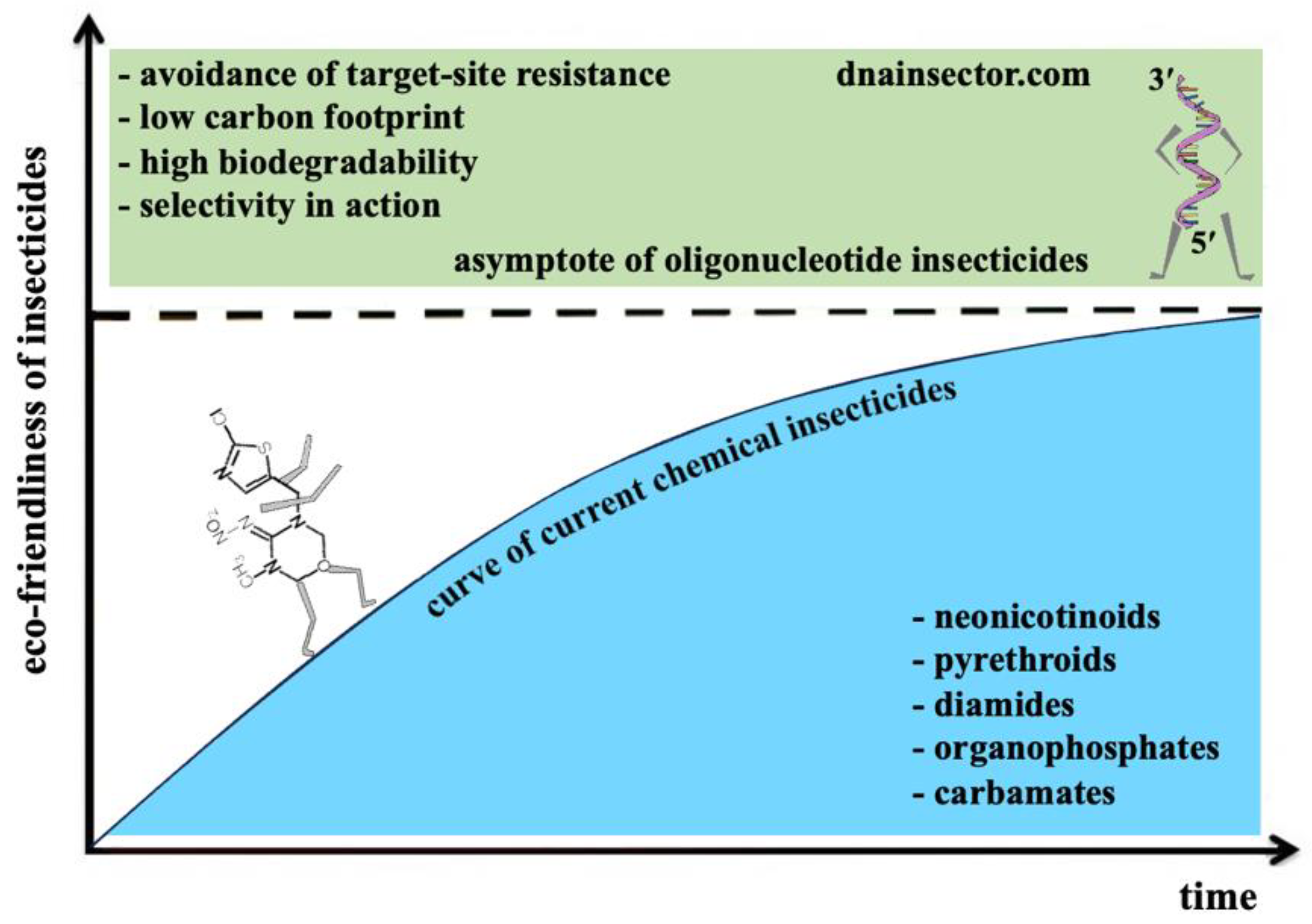

Today, CUAD (contact unmodified antisense DNA) biotechnology is the only technology that uses short unmodified antisense DNA oligonucleotides in plant protection (Oberemok and Gal’chinsky 2024; Oberemok et al. 2024a). Unlike modern chemical insecticides, oligonucleotide insecticides use natural mechanism of action and are part of this mechanism. In addition to the high biodegradability potential, low carbon footprint, and safety for non-target organisms, the opportunity of solving the problem of target-site resistance using oligonucleotide insecticides based on conservative gene sequences is expected (Gal’chinsky et al. 2023, 2024; Oberemok et al. 2023; Kumar et al. 2024; Patil et al. 2024; Gavrilova et al. 2025). With abovementioned advanced characteristics, never seen before for chemical insecticides, oligonucleotide insecticides serve as an asymptote that cannot be reached by current pest control agents (

Figure 1). As a new class of insecticides, oligonucleotide insecticides can reduce the concentration of modern chemical insecticides (organic xenobiotics) in ecosystems (Oberemok et al. 2024a) and provide organic agriculture. CUAD biotechnology, or so-called ‘genetic zipper’ method, is a very efficient and eco-friendly platform against hemipteran insect pests from suborder Sternorrhyncha (aphids, whiteflies, mealybugs, psyllids, soft scale insects, armored scale insects, etc.) and spider mites; in average, mortality rate comprises 80-90 % in 3-14 days after single treatment (Gal’chinsky et al. 2024; Oberemok et al. 2024a). Already today, according to our estimations, the ‘genetic zipper’ method is potentially capable of controlling 10-15% of all insect pests with a simple and flexible algorithm (Oberemok et al. 2024c).

Oligonucleotide insecticides can be designed using DNAInsector program (dnainsector.com) or manually using sequences of pest pre-rRNA and rRNA found in GenBank database. Literally, now you can manually create any oligonucleotide insecticide complementary to pre-rRNA or/and rRNA of a sternorrhynchan and with a very high probability it will work very efficiently. For selectivity, you should consider the same sites of pre-rRNA or/and rRNA of non-target organisms, they must not coincide. The synthesis of DNA insecticides is possible by the phosphoramidite method using liquid-phase synthesis or solid-phase synthesis on DNA synthesizers such as ASM-800 (BIOSSET, Russia), OligoPilotTM (Cytiva, Sweden), 10-Column DNA Synthesizer (PolyGen, Germany), etc. (Gal’chinsky et al. 2023). Oligonucleotide insecticides are generally dissolved in nuclease-free water and usual concentration is 1 mg of olinscides per 10 ml of water solution and applied per m2 of plant leaves containing insect pests (Gal’chinsky et al. 2020, 2023, 2024; Puzanova et al. 2023; Oberemok et al. 2024a). Notably, low-dose concentration of olinscides also have shown significant insecticidal effect on conifer aphids (1 µg of olinscides per 10 ml of water solution and applied per m2) and makes oligonucleotide insecticides very competitive on the market (0.5 USD/ha for control of conifer aphids) (Oberemok et al. 2024c). The length of an oligonucleotide insecticide ~ 11 nt makes it possible to create selective oligonucleotide insecticides with a uniqueness frequency equal to 1/4.19·106 (Oberemok et al. 2024a). Animals and plants comprise around 1.2·106 species (National Geographic 2024), and this level of uniqueness of an olinscide will be sufficient to provide safe DNA-programmable plant protection in most agrocenoses and ecosystems. Many random oligonucleotides in our investigations did not cause a significant insecticidal effect on target insect pests. Moreover, previous studies of the effect of oligonucleotide insecticides on the biochemical parameters of the plants and on the viability of the insects showed their safety for non-target organisms as well (Oberemok et al. 2013, 2019, 2024a; Oberemok and Skorokhod 2014; Zaitsev et al. 2015).

2. Recommendations on the Application of Oligonucleotide Insecticides

Contact oligonucleotide insecticides are recommended for use in the morning (from 9 to 11 a.m.) and in the evening (from 5 to 7 p.m.) in dry and windless weather at a temperature of 20–27 °C (Oberemok et al. 2018, 2023). For one tree 2–3 meters high, it is recommended to use 8–10 mg of an 11-nt long oligonucleotide insecticide. For treatments, an aqueous solution of DNA insecticides should be used at a rate of 300–400 ml per tree (Oberemok 2023). Adding of auxiliary substances (spreaders, adhesives, penetrators, UV protectants, etc.) to formulation is possible in each separate case and their effect on efficiency and safety of the final formulation should be previously evaluated. Oligonucleotide pesticides are also compatible with the use of viral (Oberemok et al. 2017) and fungal (Gavrilova et al. 2025) biopesticides showing higher mortality of the pests.

Treatment with an oligonucleotide insecticide is recommended to be carried out using a backpack sprayer or a cold fog generator with a droplet size of 10–20 microns, changing the angle of attack so that the olinscide gets on the entire leaf surface of trees with insect pests located on them. If there are 400–500 trees per hectare of forest, 10–12 g of an 11-nt oligonucleotide insecticide dissolved in 180–200 liters of distilled water will be sufficient. For bushes and grasses, 9–10 g of an 11-nt oligonucleotide insecticide dissolved in 180–200 liters of distilled water will be enough (Oberemok 2023). Oligonucleotide insecticide do not possess pronounced characteristics of systemic insecticides and direct contact of oligonucleotide insecticides with insect integument is required for substantial insecticidal effect (Oberemok et al. 2024d).

During treatments, it is important to prevent inhalation of olinscide particles into the lungs by using anti-dust (anti-aerosol) respirators. Additionally, safety glasses should be worn to protect the eyes. This is necessary because the potential non-specific effects of DNA insecticides have to be thoroughly studied. The frequency of treatments depends on the dynamics of larval hatching and is possible to apply 1-3 treatments (with daily interval) to get sufficient insecticidal effect (Oberemok 2023).

It is recommended that DNA insecticides be lyophilized after synthesis and stored in polypropylene containers in a cool and dry place at room temperature away from sunlight or in the refrigerator at a temperature of 5-8 °C. A ready-to-use water solution with DNA insecticide is recommended to be prepared in the day of application. The absence of degradation of the active substance of the olinscide can be assessed using a mass spectrometer or nucleic acid electrophoresis using an appropriate freshly prepared olinscide standard in a 3-4% agarose gel (Oberemok 2023).

Before application of oligonucleotide insecticides, it is necessary to assess weather conditions, follow safety rules and begin plant protection measures only if they meet the requirements described above (Oberemok 2023).

3. Discussion

Invented in 2008, CUAD biotechnology is among three cost-effective antisense technologies used for insect pest control (RNAi, CUAD, and CRISPR/Cas) based on the formation of duplexes of unmodified nucleic acids (RNAi: guide RNA-mRNA; CUAD: guide DNA-rRNA; CRISPR/Cas: guide RNA-genomic DNA) and action of nucleic acid-guided nucleases (RNAi: Argonaute; CUAD: RNase H; CRISPR/Cas: CRISPR-associated protein). All three technologies started out from the scratch, when nothing is certain, and evolved into powerful tools of pest control. Since the operation of RNAi, CUAD, and CRISPR/Cas technologies is based on the complementary interaction of an antisense molecule, either DNA or RNA, with a target nucleic acid for its further cleavage by specific nucleases, in a broad sense all of them are called as antisense technologies. While CUAD (Oberemok et al. 2024a) and RNAi (Fire et al. 1998) show great potential to be used as the next-generation biochemical insecticides (Oberemok et al. 2024e), CRISPR/Cas is used to genetically attenuate insect pest populations through genetic engineering (Jinek et al. 2012). Organic (xenobiotic-free) farming is becoming popular all over the world today and is a paradigm of the strategic vector of economic development in many agricultural countries. Antisense technologies (RNAi, CUAD, and CRISPR/Cas) are capable of ensuring agriculture that is safe for the environmental and human health.

Laboratory and field experiments have been conducted by our team since 2008 and formed the basis for these brief notes on the use of oligonucleotide insecticides for insect pest control in forests and agrocenoses. Most technological innovations initially were expensive and with poor performance, but eventually become both affordable and reliable. CUAD-based ‘genetic zipper’ method has come a long way for 17 years and is very close to the point to be implemented on a large scale against sternorrhynchans and other pests.

Biodiversity decrease, climate change, high toxicity load in ecosystems dictate new rules for plant protection. If pre-market environmental risk assessment for the approval of new active substances succeeds, oligonucleotide insecticides will be brought to market in abundance and will complement current classes of chemical insecticides. We envision that oligonucleotide insecticides (CUAD biotechnology) can be used solely and also can come into place in complex bioformulations for selective control of a wide range of insect pests and will mark a new marvelous period in efficient and selective plant protection.

On 1935 P. Muller began his search for an ‘ideal’ insecticide, one that would show rapid, potent toxicity for insect species with no harm effect to plants and warm-blooded animals. Four years later he found that DDT satisfied these requirements (Britannica 2024). Today we understand that it was only the beginning of the journey. Over the last 90 years, 6 main classes of chemical insecticides have appeared (organochlorines, organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids, neonicotinoids, diamides) (Araújo et al. 2023). Oligonucleotide insecticides as a perspective 7th class of insecticides are going to possess amazing eco-friendly characteristics (selectivity in action, high biodegradability, low carbon footprint, avoidance of target-site resistance) that no other insecticides have had before in history. CUAD biotechnology creates opportunities never existed before, because any farmer, botanical garden or pests control company is capable of creating very quickly its unique arsenal insecticides well-tailored for a particular population of an insect pest. These recommendations will help scientists and farmers around the world to use oligonucleotide insecticides more efficiently after registration.

Author Contributions

VO: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NG: Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

Research results obtained within the framework of a state assignment V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University for 2024 and the planning period of 2024–2026 No. FZEG-2024–0001.

Acknowledgments

We thank our many colleagues, too numerous to name, for the technical advances and lively discussions that have prompted us to write this opinion. We apologize to the many colleagues whose work has not been cited. We are very much indebted to all anonymous reviewers and our colleagues from the Lab on DNA technologies, PCR analysis and creation of DNA insecticides (V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University, Institute of Biochemical Technologies,

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ecology and Pharmacy, Department of General Biology and Genetics), and OLINSCIDE BIOTECH LLC. for valuable comments on our manuscript.

References

- Araújo MF, Castanheira EMS, Sousa SF (2023) The Buzz on Insecticides: A Review of Uses, Molecular Structures, Targets, Adverse Effects, and Alternatives. Molecules 28:3641. [CrossRef]

- Britannica (2024) DDT. https://www.britannica.com/science/DDT. Accessed 18 June 2024.

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC (1998) Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391(6669):806-11. [CrossRef]

- Gal’chinsky N, Useinov R, Yatskova E, Laikova K, Novikov I, Gorlov M, Trikoz N, Sharmagiy A, Plugatar Y, Oberemok V (2020). A breakthrough in the efficiency of contact DNA insecticides: rapid high mortality rates in the sap-sucking insects Dynaspidiotus britannicus Comstock and Unaspis euonymi Newstead. Journal of Plant Protection Research 60(2):220–223. [CrossRef]

- Gal’chinsky NV, Yatskova EV, Novikov IA, Sharmagiy AK, Plugatar YV, Oberemok VV (2024) Mixed insect pest populations of Diaspididae species under control of oligonucleotide insecticides: 3′-end nucleotide matters. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 105838. [CrossRef]

- Gal’chinsky NV, Yatskova EV, Novikov IA, Useinov RZ, Kouakou NJ, Kouame KF, Kra KD, Sharmagiy AK, Plugatar YV, Laikova KV, Oberemok VV (2023) Icerya purchasi Maskell (Hemiptera: Monophlebidae) Control Using Low Carbon Footprint Oligonucleotide Insecticides. Int J Mol Sci 24(14):11650. doi 10.3390/ijms241411650.

- Gavrilova D, Grizanova E, Novikov I, Laikova E, Zenkova A, Oberemok V, Dubovskiy I (2025) Antisense DNA acaricide targeting pre-rRNA of two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae as efficacy-enhancing agent of fungus Metarhizium robertsii. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 108297. [CrossRef]

- Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier EA (2012) Programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337(6096):816-21. [CrossRef]

- Kumar H, Verma S, Behera R, Chandel A, Sharma M, Sagar D (2024) DNA Insecticide: An Emerging Crop Protection Technology. Indian Journal of Entomology. e24160. [CrossRef]

- National Geographic (2024) Biodiversity. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/biodiversity/. Accessed 18 June 2024.

- Oberemok V, Laikova K, Gal’chinsky N (2024a) Contact Unmodified Antisense DNA (CUAD) Biotechnology: List of Pest Species Successfully Targeted by Oligonucleotide Insecticides. Front. Agron 6. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok V, Nyadar P, Zaitsev A, Levchenko N, Shiyntum H, Omelchenko O (2013) Pioneer evaluation of the possible side effects of the DNA insecticides on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). International Journal of Biochemistry and Biophysics 1(3):57−63. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok VV (2008) Method of Elimination of Phyllophagous Insects from Order Lepidoptera. Ukrainian Patent UA No. 36445.

- Oberemok VV (2023) Development of DNA insecticides: a modern approach. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380727180_Development_of_DNA_insecticides_a_modern_approach_Razrabotka_DNK-insekticidov_sovremennyj_podhod. Accessed 25 May 2024.

- Oberemok VV, Skorokhod OA (2014) Single-stranded DNA fragments of insect-specific nuclear polyhedrosis virus act as selective DNA insecticides for gypsy moth control. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol 113:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok VV, Gal’chinsky NV (2024) Oligonucleotide insecticides (contact unmodified antisense DNA biotechnology) and RNA biocontrols (double-stranded RNA technology): newly born fraternal twins in plant protection. bioRxiv [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.03.13.584797v1. Accessed 14 March 2024.

- Oberemok VV, Gal’chinsky NV, Novikov IA, Sharmagiy AK, Yatskova EV, Laikova EV, Plugatar YV (2024d) rRNA-specific antisense DNA and dsDNA trigger rRNA biogenesis and cause potent insecticidal effect on insect pest Coccus hesperidum L. bioRxiv [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.10.15.618468v1. Accessed 17 October 2024.

- Oberemok VV, Gal’chinsky NV, Useinov RZ, Novikov IA, Puzanova YV, Filatov RI, Kouakou NJ, Kouame KF, Kra KD, Laikova KV (2023) Four Most Pathogenic Superfamilies of Insect Pests of Suborder Sternorrhyncha: Invisible Superplunderers of Plant Vitality. Insects 14(5):462. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok VV, Laikova KV, Andreeva OA, Gal’chinsky NV (2024e) Oligonucleotide insecticides and RNA-based insecticides: 16 years of experience in contact using of the next generation pest control agents. J Plant Dis Prot 131:1837–1852. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok VV, Laikova KV, Gal’chinsky NV, Shumskykh MN, Repetskaya AI, Bessalova EY, Makalish TP, Gninenko YI, Kharlov SA, Ivanova RI, Nikolaev AI (2018) DNA insecticides: Data on the trial in the field. Data Brief 21:1858-1860. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok VV, Laikova KV, Zaitsev AS, Shumskykh MN, Kasich IN, Gal’chinsky NV, Bekirova VV, Makarov VV, Agranovsky AA, Gushchin VA, Zubarev IV, Kubyshkin AV, Fomochkina II, Gorlov MV, Skorokhod OA (2017) Molecular Alliance of Lymantria dispar Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus and a Short Unmodified Antisense Oligonucleotide of Its Anti-Apoptotic IAP-3 Gene: A Novel Approach for Gypsy Moth Control. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18(11):2446. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok VV, Novikov IA, Yatskova EV, Sharmagiy AK, Gal’chinsky NV (2024b) Potent and selective ‘genetic zipper’ method for DNA-programmable plant protection: innovative oligonucleotide insecticides against Trioza alacris Flor. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric 11:144. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok VV, Puzanova EV, Gal’chinsky NV (2024c) The ‘genetic zipper’ method offers a cost-effective solution for aphid control. Front. Insect Sci 4. [CrossRef]

- Palazzo AF, Lee ES (2015) Non-coding RNA: what is functional and what is junk? Front Genet 6:2. [CrossRef]

- Patil V, Jangra S, Ghosh A (2024) Advances in antisense oligo technology for sustainable crop protection. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Puzanova YV, Novikov IA, Bilyk AI, Sharmagiy AK, Plugatar YV, Oberemok VV (2023) Perfect Complementarity Mechanism for Aphid Control: Oligonucleotide Insecticide Macsan-11 Selectively Causes High Mortality Rate for Macrosiphoniella sanborni Gillette. Int J Mol Sci 24(14):11690. [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev AS, Omel’chenko OV, Nyadar PM, Oberemok VV (2015) Influence of DNA Oligonucleotides Used as Insecticides on Biochemical Parameters of “Quercus Robur” and “Malus Domestica “. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov 8:37–46.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).