1. Introduction

Kupletskite, K

2NaMn

2+7Ti

2(Si

4O

12)

2O

2(OH)

4F, and kupletskite-(Cs), Cs

2NaMn

2+7Ti

2(Si

4O

12)

2O

2(OH)

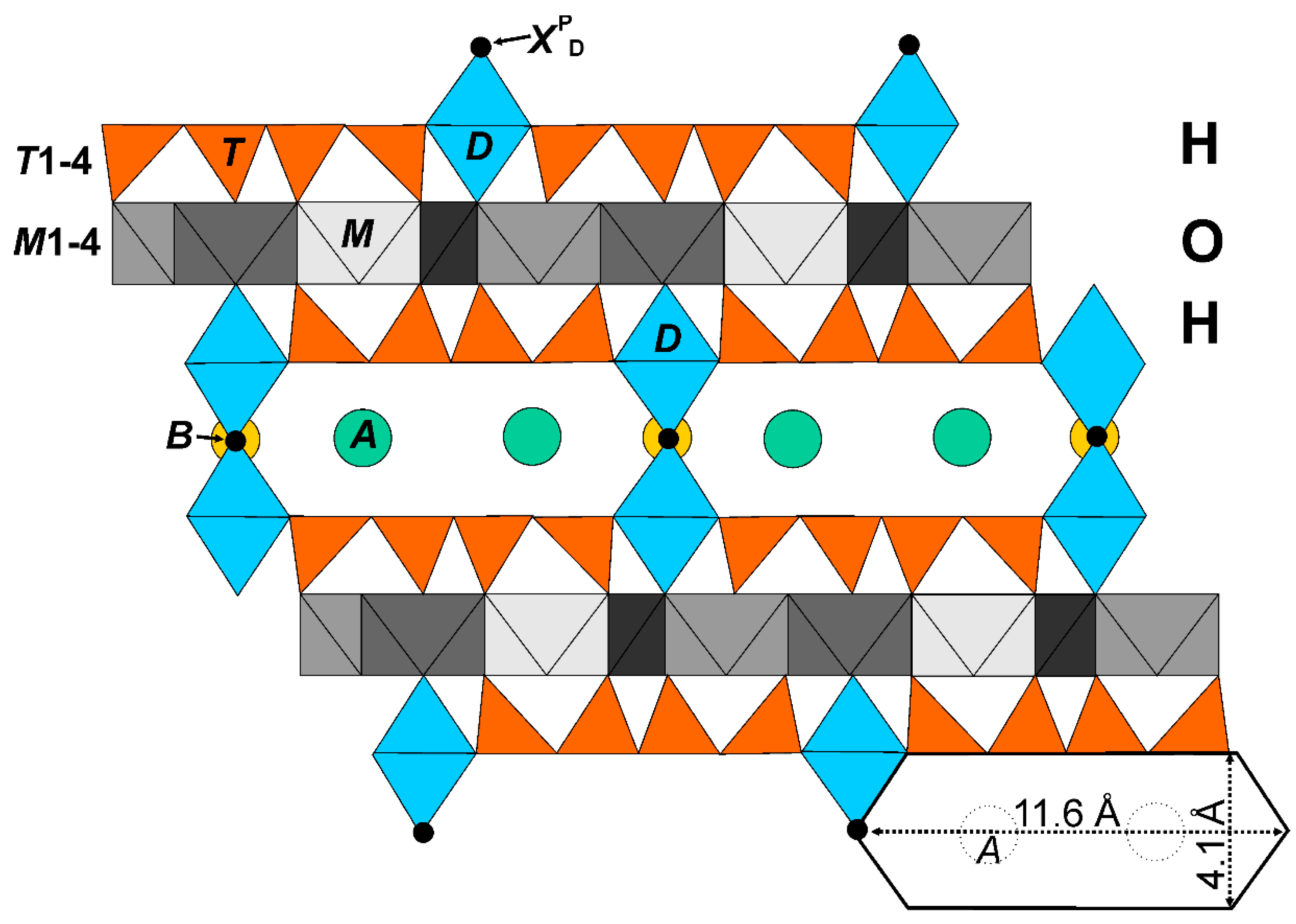

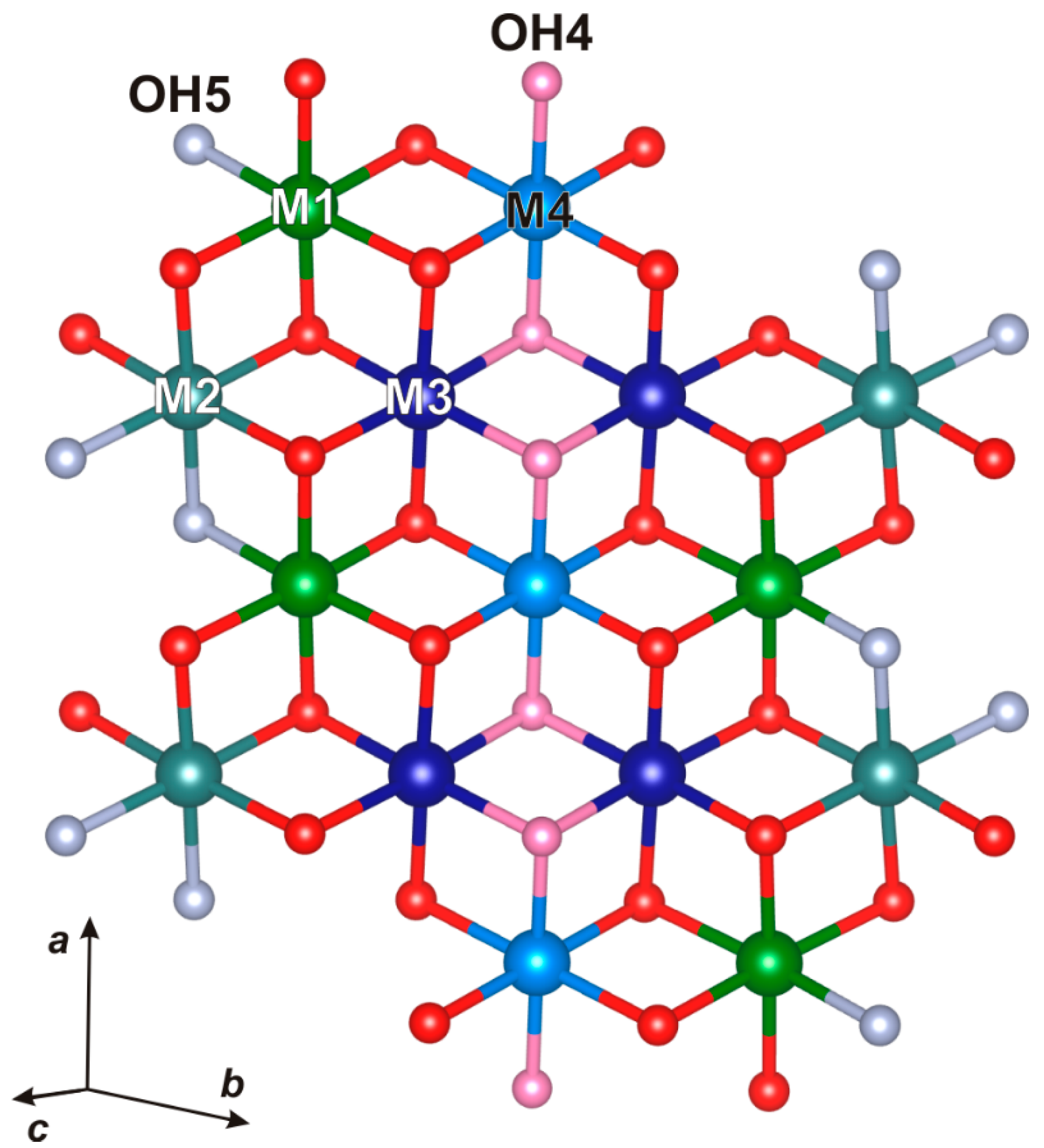

4F, are titanosilicates with layered structures, also known as layered titanosilicate micas in the terminology of Belov (1976). Their crystal structures consist of one brucite-type octahedral (O) layer sandwiched between two heteropolyhedral (H) layers. The H layer is constructed of

zweier [

T4O

12]

8− chains of TO

4 tetrahedra [Liebau, 1985] (

T = Si, Al) and

Dφ

6 octahedra (

D = Ti, Nb and Zr; φ = O, F and OH). These O and H layers form HOH blocks. The HOH titanosilicates are numerous and may form topologically different structures [Ferraris et al., 2008]. In recent mineral nomenclature, kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) are part of the kupletskite group and astrophyllite supergroup [Sokolova et al., 2017]. Kupletskite is the Mn-analogue of astrophyllite, K

2NaFe

2+7Ti

2(Si

4O

12)

2O

2(OH)

4F, and kupletskite-(Cs) is Mn-Cs-analogue of astrophyllite; all three minerals have the astrophyllite structure-type (

Figure 1); [Piilonen, 2003a]. In their crystal structures two HOH blocks are linked by sharing the

XPD site (mainly occupied by F). The O layer contains four sites,

M(1)-(4), occupied by Mn, Fe and Mg. The H layer contains a net of SiO

4 groups and Tiφ

6 octahedra, φ = 5O + 1F. The astrophyllite-type structure is porous (

Figure 1) with cavities of two types: the first cavity is occupied by

A-site cations (K or Cs) with minor H

2O content, the second cavity is filled with

B-site cations, mainly Na. Сesium minerals are quite rare, and so kupletskite-(Cs) is of interest as a natural sink for Cs that is accommodated in large cavities of the structure.

In our previous work, Zhitova et al. (2017a,b; 2019) [Zhitova et al., 2017a,b; 2019] showed for the first time in titanosilicates (using astrophyllite-supergroup minerals) that simultaneous Fe oxidation and dehydroxylation (or deprotonation) processes that happen at temperature above 500 °C resulting in formation of high-temperature modifications. First, astrophyllite, K2NaFe2+7Ti2(Si4O12)2O2(OH)4F, [Zhitova et al., 2017a] experiences coupled Fe-oxidation dehydroxylation and defluorination, leading to formation of the high-temperature modification, K2Na(Fe3+,Mg)7Ti2(Si4O12)2O2O4O, that is stable from 550 to 750 °C. The transformation is irreversible and the high-temperature modification remains stable at room conditions [Zhitova et al., 2017a]. The same behaviour is shown by bafertisite, Ba2Fe2+4Ti2(Si2O7)2O2(OH)2F2; however, in bafertisite, Fe2+ > OH apfu and this precludes formation of the stoichiometric high-temperature oxidized modification [Zhitova et al., 2017b]. The most novel results were found for lobanovite, K2Na(Fe2+4Mg2Na)Ti2(Si4O12)2O2(OH)4, in which oxidation-dehydroxylation reactions combined with migration of Fe and Mg cations over the M(1)-(4) sites in order to satisfy the valence-sum rule [Brown, 2016; Hawthorne, 2012, 2015] at the apical oxygen of the TiO5 square pyramid [Zhitova et al., 2019].

Temperature-induced Fe oxidation has been reported for amphibole-, mica- and tourmaline-supergroup minerals (Fe-rich phlogopite [Russell, Guggenheim, 1999; Chon et al., 2006; Ventruti et al., 2008; Zema et al., 2010], illite [Murad, Wagner, 1996], biotite [Güttler et al., 1989], vermiculite [Veith, Jackson, 1974]; tourmaline-supergroup minerals [Korovushkin et al., 1979; Ferrow et al., 1988; Bačik et al., 2011; Filip et al., 2012], and amphibole-supergroup minerals [Oberti et al., 2015; Della Ventura, 2015; Susta et al., 2015; and references therein]. Recently, temperature-induced migration of M-site Fe2+ and Fe3+ has been observed for the amphibole-supergroup mineral – riebeckite, ◻[Na2][Fe2+3Fe3+2]Si8O22(OH)2, forming CR3+-disordered riebeckite with an atypical cation distribution [Della Ventura et al., 2023a]. High-temperature Raman spectra [Mihailova et al., 2022] show that electrons released by oxidation couple with the phonon spectrum to produce itinerant polarons. These drastically affect the magnitude [Della Ventura et al., 2023b] of the conductivity of the amphibole. In turn, the occupancy of the A-site affects the temperature at which the polarons form, and the resulting conductivity is very anisotropic [Bernedini et al., 2024]. Due to the effect of stress-driven alignment of amphiboles during plate motion, subducting metamorphic rocks can show strongly anisotropic conductivity on a large scale [Bernedini et al., 2025]. Thus, the Fe-oxidation process in minerals can affect large-scale Earth processes at elevated temperatures and pressures in the Earth [Della Ventura et al., 2024].

Due to porous crystal structure, theses minerals are considered prototypes of ion exchangers, sorbents and catalysts [Ferraris, 2005; Ferraris and Merlino, 2005; Lin et al., 2011]. The experimental studies revealed exchange of extra framework cations for other alkali metals and one-dimensional ion conductivity of alkali metals Na+, K+, Rb+, Cs+, Ag+ and Pb2+ and two-dimensional ion conductivity for Li+ ions within channels [Aksenov et al., 2022]. The presence of 5- and 6-coordinated Ti in the heteropolyhedral layers is promising in term of their catalytic properties [Lin et al., 2011; Ferraris, 2005].

This study characterizes the high-temperature behavior of two Mn-minerals with astrophyllite structure type that differ by A-site extra-framework cations: K for kupletskite and Cs for kupletskite-(Cs). Although the astrophyllite-supergroup minerals do not dominate the chemical compositions of the rocks in which they occur (as do amphiboles and micas), their high-temperature behavior may affect their host rocks at a smaller scale that is the case for the major rock-forming minerals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The kupletskite studied in this work originates from the Khibiny alkaline complex (Kola peninsula, Russia) [Yakovenchuk et al., 2005] and the sample is denoted K25. Kupletskite-(Cs) originates from Dara-i-Pioz Glacier (Alai Range, Tien Shan Mtn, Tajikistan) [Yefimov et al., 1971] and the sample is denoted CsK25.

The heat-treated (or annealed) modifications are denoted as K for kupletskite and CsK for kupletskite-(Cs). The high-temperature (HT) modifications of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) were obtained by heating K25 and CsK25 in an oven with the following strategy: 30 min heating to T (°C), 30 min kept at that T (°C) followed by cooling to room temperature.

The main work was done on each mineral; however, as kupletskite-(Cs) is rare and the quantity for analytical study was limited, some experiments were done only for kupletskite.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Electron-Microprobe Analysis

Several crystals of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) were mounted in epoxy blocks, polished, carbon-coated and analyzed using the scanning electron microscope Hitachi S-3400N equipped with an AzTec analyzer Energy 350. The operating conditions were energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mode at 20 kV, 1.5 nA and a 5 µm spot size and 10 mm working distance. The standards are NaCl (Na), KCl (K), CaSO4 (Ca), Cs2O (Cs), PbO (Pb), MgO (Mg), MnO (Mn), FeO (Fe), Al2O3 (Al2O3), TiO2 (Ti), Nb2O5 (Nb), SiO2 (Si), BaF2 (F).

2.2.2. High-Temperature In Situ X-Ray Diffraction

The thermal behavior of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) was studied by in situ high-temperature X-ray diffraction (HTXRD) in the 25–1000 °C temperature range in air with a Rigaku Ultima IV powder X-ray diffractometer (CuKα1+2 radiation, U = 40 kV, I = 30 mA, Bragg–Brentano geometry, PSD D-Tex Ultra) with Rigaku HT 1500 high-temperature attachment in air. A thin powder sample was deposited on a Pt sample holder (20 × 12 × 2 mm3) from a heptane suspension. The temperature step and the heating rate were 25 °C and 4 °/min, respectively. The reversibility of the observed phase transformation was checked by re-recording the powder patterns of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) heated above 500 °C and then cooled to room temperature.

The unit-cell parameters were refined by the Rietveld method (the data are provided in Tables S1, S2) using Topas 4.2 [Bruker AXS, 2009], and the atom coordinates, site scattering and isotropic-displacement parameters were kept fixed. Refinement of the unit-cell parameters was done in the temperature ranges 25–450 °C for kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) and 550–725 °C for their high-temperature modifications. The 475–525 °C range was excluded due to broadening of some reflections in the patterns, indicating the coexistence of kupletskite/kupletskite-(Cs) and their high-temperature modifications. Neutral scattering factors were used for all atoms. The background was modeled using a Chebyshev polynomial approximation of 12-th order. The peak profile was described using the fundamental parameters approach. Refinement of preferred orientation parameters confirmed the presence of a significant preferred orientation along the [001] direction.

The main coefficients of the thermal-expansion tensor were determined using a second-order approximation of temperature dependencies for the unit-cell parameters (Tables S3, S4) in the ranges 25–450 °C for kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) and 550–725 °C for their high-temperature modifications by the DTC program [Belousov, Filatov, 2007; Bubnova et al., 2013]. The DTC program was also used to determine the orientation of the principal axes of the thermal-expansion tensor with respect to the crystallographic axes. The thermal-expansion tensor was visualized using the TEV program [Langreiter, Kahlenberg, 2014].

2.2.3. Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction

Crystals of K25, K650, CsK25 and CsK650 were examined in air at room temperature using a single-crystal diffractometer Bruker SMART APEX operated at 50 kV and 40 mA, equipped with a CCD area-detector and graphite-monochromatized Mo

Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). The data were collected and processed using the Bruker software APEX2 [Bruker AXS, 2014]; details of data collection are listed in

Table 1. The intensity data were reduced and corrected for Lorentz, polarization and background effects using the Bruker software APEX2 [Bruker AXS, 2014]. A semi-empirical absorption-correction based upon the intensities of equivalent reflections was applied [SADABS, Sheldrick, 2015]. The diffraction data obtained during single-crystal X-ray experiments were indexed in a standard triclinic unit-cell (

Table 1). The structures have been refined using SHELXL program package [Sheldrick, 2015] within the Olex2 shell [Dolomanov et al., 2009].

2.2.4. Infrared Spectroscopy

Infrared (IR) absorption spectra were measured using: (a) a Bruker Vertex IR spectrometer for K25, CsK25, K670, CsK670, and (b) a Micran-3 infrared microscope and a Simex FT-801 spectrometer with a Ge-attenuated total reflection (ATR) module for K25, K550, K600 and K650 (this data is correlated with optical absorption spectroscopy). The absorption spectra of the K25, K550, K600 and K650 with 0.02 mm thickness were measured in transmittance mode of the infrared microscope.

2.2.5. Mössbauer Spectroscopy

Mössbauer spectra were collected at room temperature (RT) using a 57Co(Rh) source for the samples K25 and K650. The spectrometer was calibrated using the spectrum of metallic iron at room temperature. Powdered absorbers containing about 5 mg Fe per cm2 were pressed in plastic discs and fixed on a special aluminum holder to avoid preferred orientation of mineral grains. The spectra were approximated by a sum of Lorentzian lines using the MOSSFIT software. The relative amounts of Fe2+ and Fe3+ and their site occupancies were determined from integrated doublet intensities and hyperfine parameters, assuming equal recoil-free fractions for Fe2+ and Fe3+ at the different sites.

2.2.6. Optical Absorption Spectroscopy

Optical absorption spectra in the Ultraviolet/Visible/Near Infrared (UV/Vis/NIR) spectral region were recorded using a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 950 spectrophotometer and kupletskite plates with a thickness of 0.02-0.04 mm. The absorption spectra were recorded from the K25, K550, K600 and K650 samples.

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition

The mean chemical compositions of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) are given in

Table 2. Iron was divided into di- and trivalent ions based on Mössbauer spectroscopy data; the OH/O ratio was calculated based on charge-balance requirements. The empirical chemical formulae were calculated on the basis of Si + Al = 8. The analyses of chemical composition confirms that the starting material for high-temperature experiments was kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) (

Table 2).

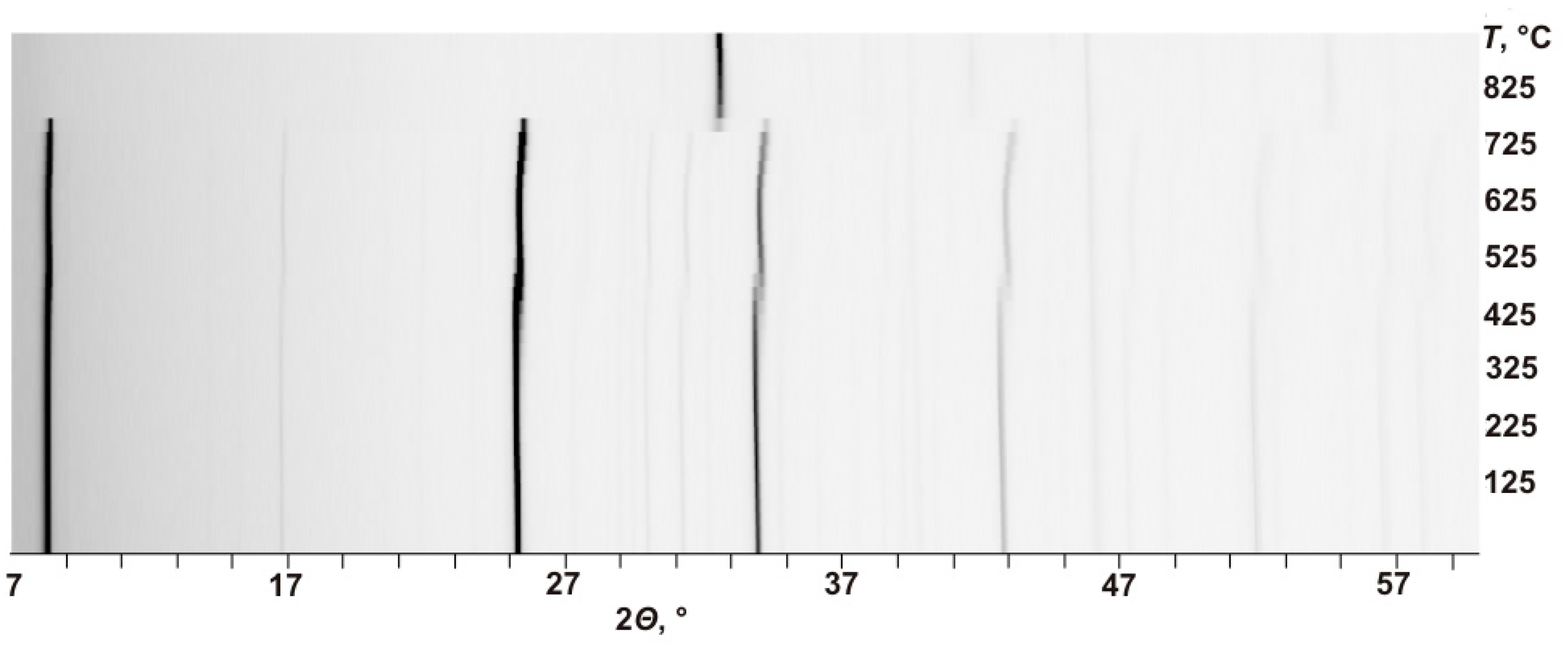

3.2. Thermal Evolution

The high-temperature behavior of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) is distinct for two temperature regions: (a) 25‒450 °C and (b) 525‒775 °C, the latter region is characterized by a shift of reflections to higher 2-theta angles (

Figure 2). At 800 °C, both minerals decompose. The

in situ high-temperature powder X-ray diffraction patterns show the inheritance of the astrophyllite structural type by the high-temperature modifications (i.e. the preservation of the main structure topology on heating) and the reduction in the unit-cell parameters at a temperature above 500 °C (

Figure 2) due to shift of the pattern to high-angle region in 2-theta axis.

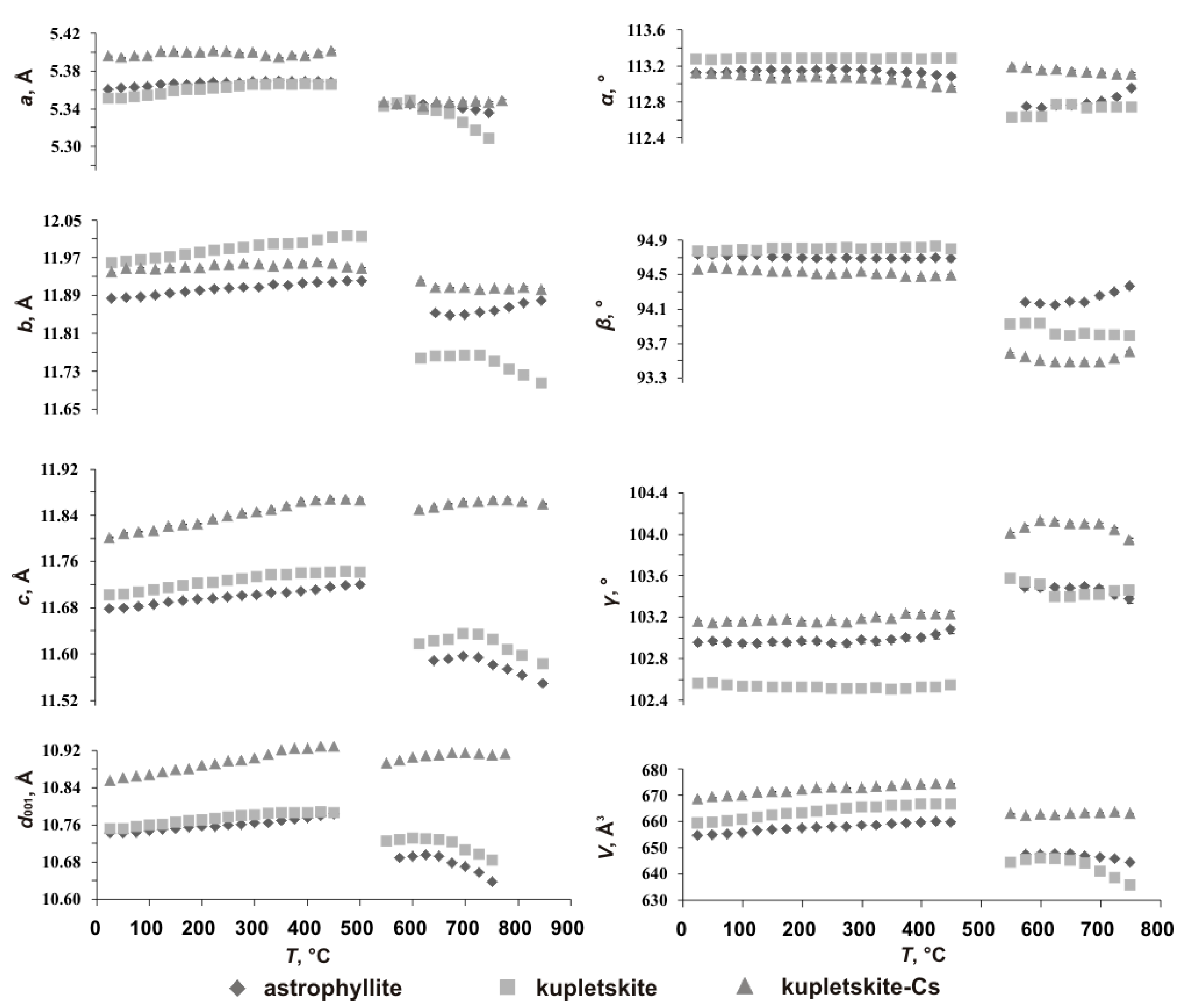

The variation of the unit-cell parameters of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs)

versus temperature are shown in

Figure 3, and the data on astrophyllite [Zhitova et al., 2017a] are given for comparison. The 25‒450 °C temperature range is characterized primarily by an increase of the unit-cell parameters (i.e. expansion), while the 525‒775 °C temperature range shows more complex behavior with some parameters increasing and others decreasing (i.e. simultaneous expansion and contraction in different crystallographic directions) (

Figure 3).

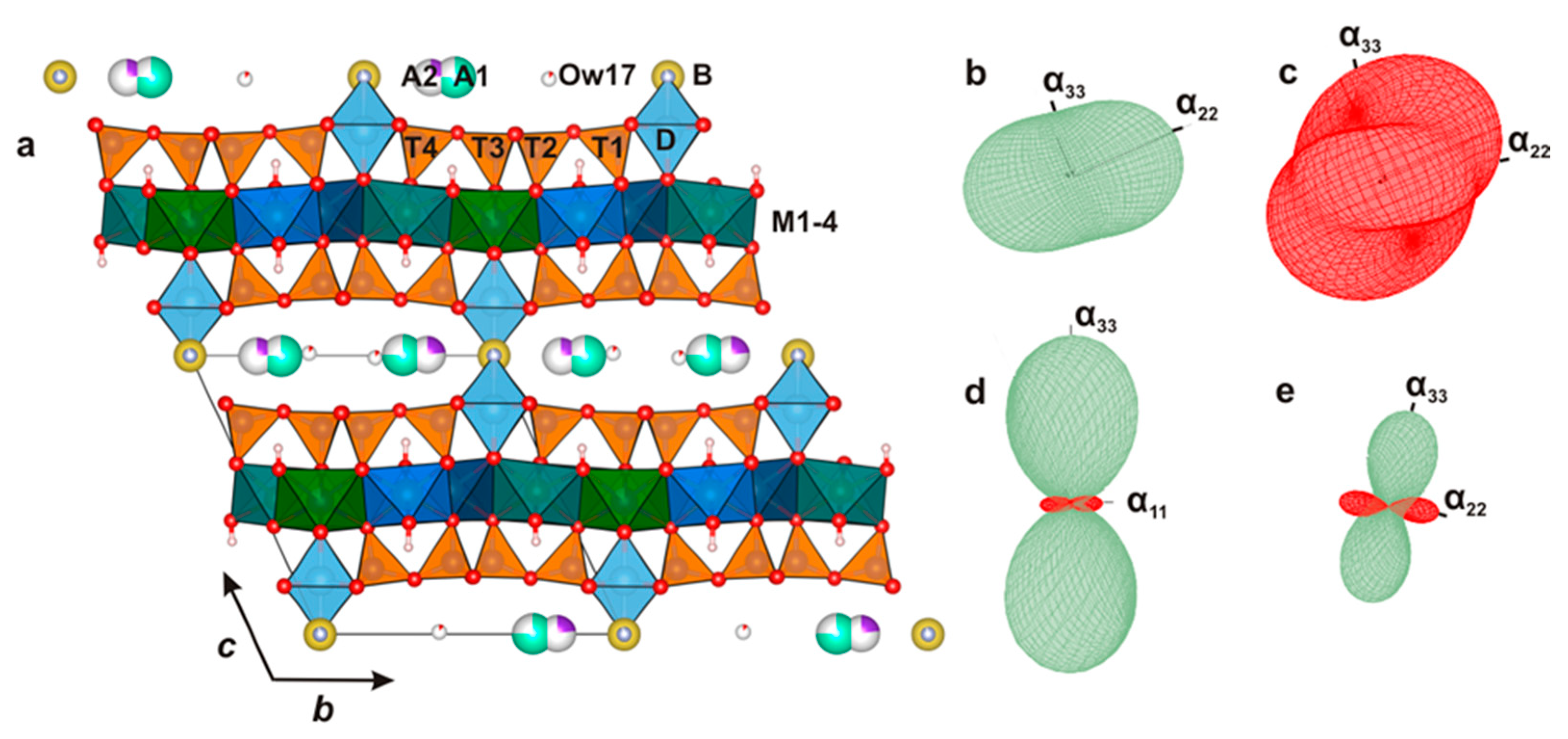

The thermal expansion coefficients for kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and their high-temperature modifications are given in

Table 3 (selected) and Tables S5, S6 (full). The figures of thermal expansion are shown in

Figure 4. The thermal behavior of both minerals and their high-temperature modifications is strongly anisotropic. For kupletskite, the maximum thermal expansion occurs within the plane of the layers and may correspond to their straightening (or decrease in corrugation). At the same time, for kupletskite-(Cs) the maximum thermal expansion is observed along the stacking direction. The high-temperature modification of kupletskite is characterized by contraction (owing to oxidation) in all directions with nearly equal coefficients within and between layers (

Figure 4) similar to astrophyllite [Zhitova et al., 2017a]. The thermal behavior of kupletskite-(Cs) is different and shows expansion with the maximal coefficient along the stacking direction (

Figure 4).

3.3. Crystal Structures

The crystal structures of kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and their high-temperature modifications (K25, K650, CsK25 and CsK650) are triclinic and

P-1 space-group symmetry. All crystal structures refined to good convergence indices (

Table 1) and the structure models agree with previously reported data [Woodrow, 1967; Piilonen et al. 2003a,b; Cámara et al., 2010; Sokolova, 2012]. The atom coordinates, isotropic-displacement parameters and site occupancies are given in

Table S7, anisotropic-displacement parameters are provided in

Table S8. Selected bond lengths are listed in

Table S9. The X-ray diffraction data confirm the powder X-ray diffraction data: the high-temperature modifications retain the structure type of astrophyllite, but are characterized by a reduction in the unit-cell parameters relative to initial kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) (

Table 1).

The O layer incorporates four metal sites

M(1)-(4) coordinated by O(1)-(7), two oxygen atoms of which OH(4) and OH(5) are protonated (

Figure 5) in K25 and CsK25 and become deprotonated in the high-temperature modifications (K650, CsK650). The site-scattering values and bond lengths are given in

Table 4. The main structural changes affect the O sheet: the

M(1)‒O bond length increases slightly with reduction of site scattering, indicating Na-Li migration to the

M(1) site and/or site-selective oxidation of transition metals. The site scattering also decreases at the

M(2) site and may indicate partial migration of Na-Li. The site-scattering values fluctuate slightly at the

M(3) and

M(4) sites which may be interpreted as an absence of significant change in their occupancies. The maximal contraction of

M‒O bond length occurs at the

M(2) and

M(4) sites (

Figure 5); it is less pronounced for the

M(3) site, indicating that most Fe

2+,Mn

2+ subject to oxidation occurs at the

M(2) and

M(4) sites and to lesser extent at

M(3).

The H layer has four symmetrically distinct silicate tetrahedra,

T(1)-(4) that share corners with each other and with

Dφ

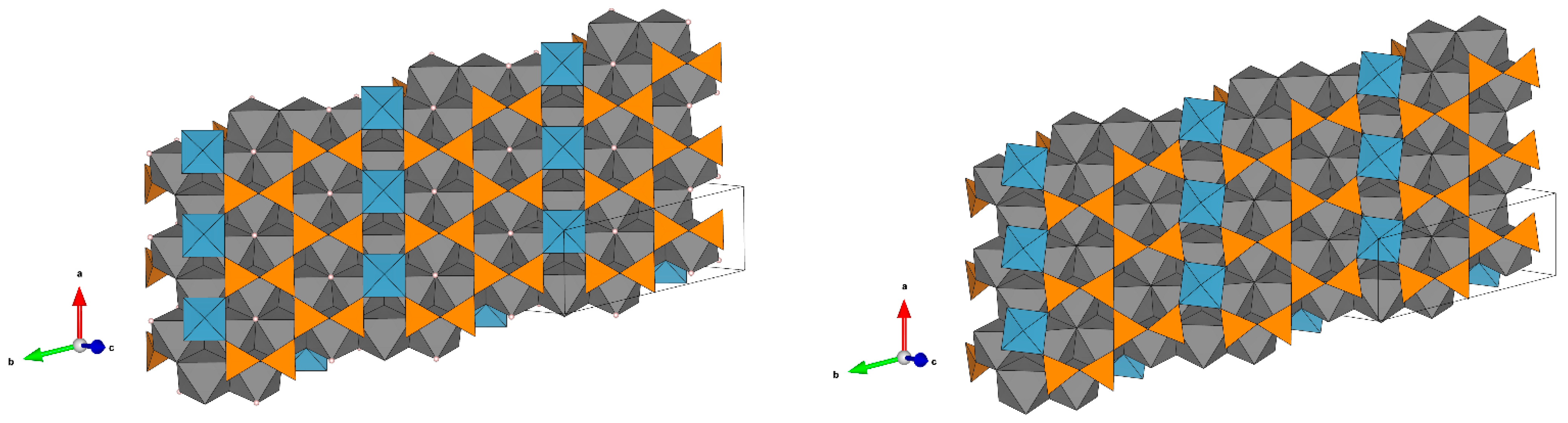

6 octahedra. The structural changes caused by oxidation-dexydroxylation also affect the H layer. The

Dφ

6 octahedra in kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) are distorted; the apical bond

D‒O2 (1.81-1.86 Å) is significantly shorter than

D‒

XPD (2.05-2.09 Å). In the high-temperature modifications of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs), the apical bonds of the

Dφ

6 octahedra are 1.90-1.96 Å for

D‒O2 and 1.99-2.00 Å for

D‒

XPD. The regulation of

Dφ

6 octahedra occurs due to a saturation of the O2 atom with additional valence units in the result of

M-cations oxidation. In addition, there is rotation of the SiO

4 tetrahedra and

Dφ

6 octahedra, giving rise to a more distorted H layer (

Figure 6).

The interlayer A site in kupletskite/kupletskite-(Cs) is split, forming the A1 and A2 sites ~0.8-0.9 Å apart. The interlayer also contains the B site occupied predominantly by Na and low-occupied oxygen (O17w site) coordinating A2. No significant changes in the geometry of the A- and B-polyhedra were detected.

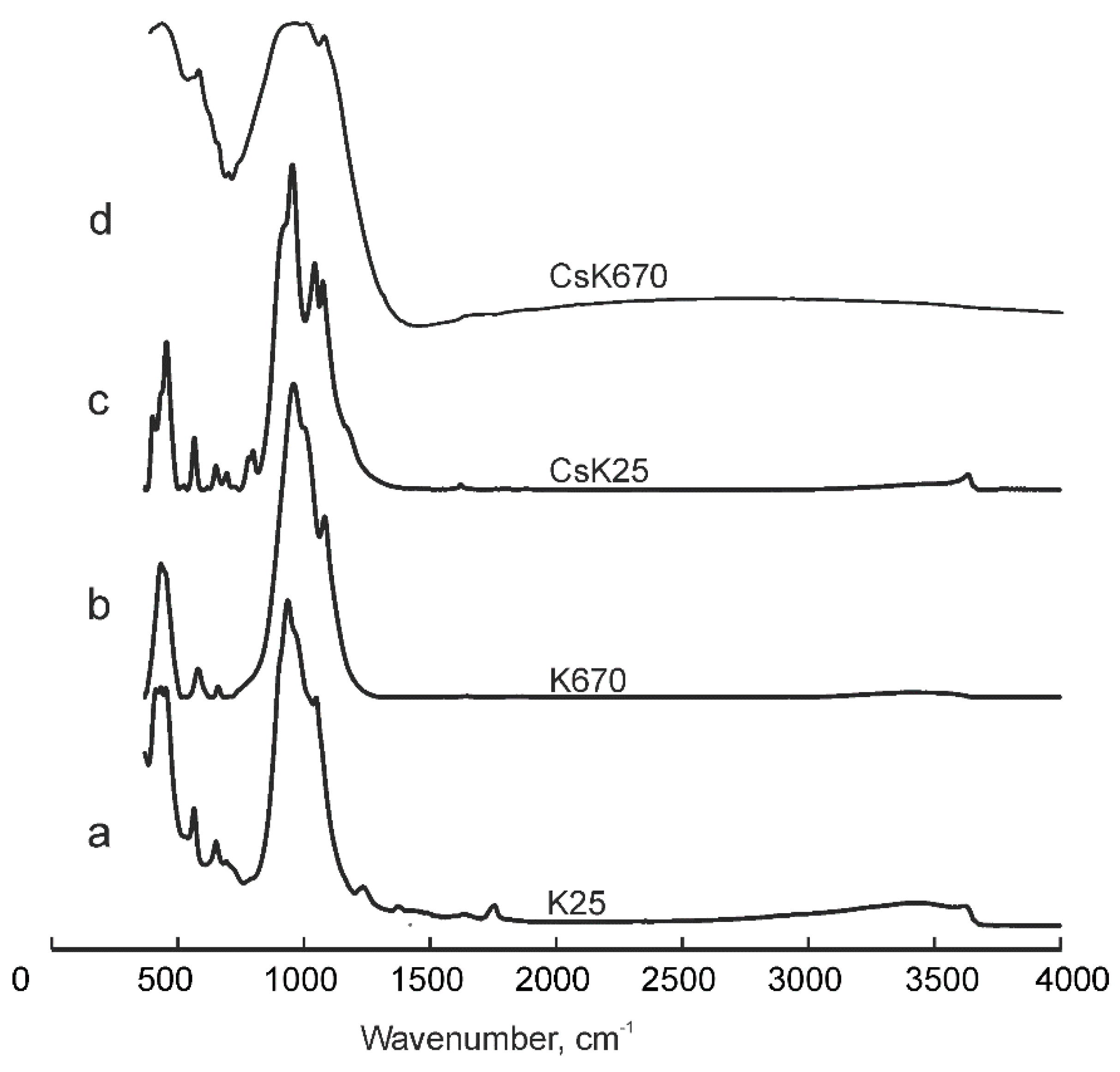

3.4. Dexydroxylation

The dehydroxylation process is clearly tracked by the reduction of O‒H intensities in the principal OH-stretching region of the infrared spectra in the wavenumber regions 3800-3000 cm

‒1 (principal O‒H stretching) for high-temperature modifications relative to the unheated crystals (

Figure 7).

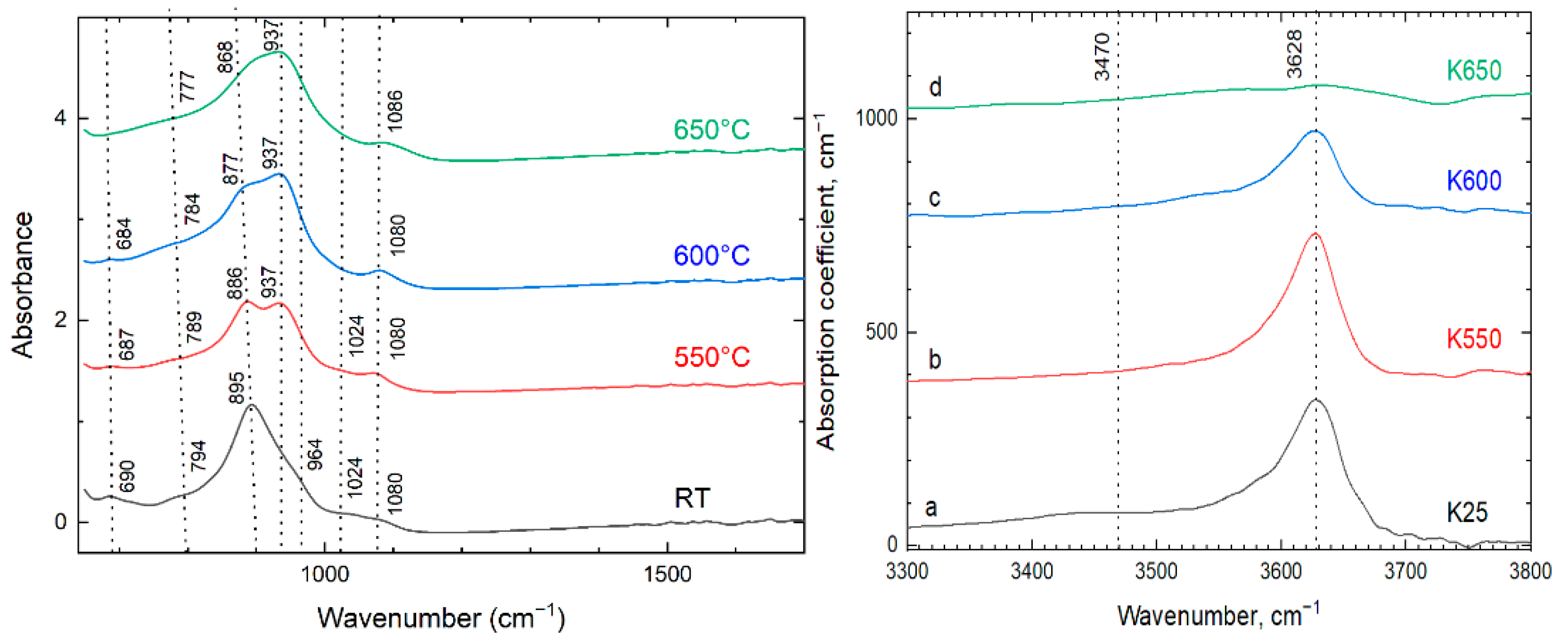

Another set of IR spectra were recorded for K25, K550, K600 and K650 from the same material as optical absorption spectra in order to monitor the heat-induced changes (

Figure 8). The infrared spectra recorded from K25 exhibit the following bands 1075, 1024, 964 (shoulder), 895, 794 and 690 cm

−1. The bands at 1075 and 1024 cm

−1 are assigned to the Si‒O stretching vibrations in Si‒O‒Si chains. The bands at 964, 895 and 794 cm

-1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of apical Si‒O bonds. The band at 690 cm

−1 is assigned to the bending vibration of O‒Si‒O. Upon heating of kupletskite, the infrared spectra change: bands at 895, 789 and 690 cm

−1 (K25) shift to 886, 789 and 687 cm

−1 (K550) and the intensity of shoulder at 964 cm

−1 (K25) decreases with the appearance of a new band at 937 cm

−1 (K550). Heating to higher temperatures (K600, K650) leads to further shift of the bands to 877, 784 and 684 cm

−1 (K600) and 868, 784 cm

−1 and disappearance of the 690-680 cm

−1 band. These changes occur synchronously with increase of intensity for the band at 937 cm

−1 (

Figure 8). The intensity of 3628 cm

−1, attributed to O‒H stretching, decreases in K600 and disappears in K650.

3.5. The Fe and Mn Oxidation

The hyperfine parameters of the Mössbauer spectra of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) (samples K25 and CsK25) and their high-temperature modifications (samples K650 and CsK600) are given in

Table 5. The spectra show absorption peaks due to both Fe

2+ and Fe

3+. The spectra were fit to a QSD model having two/three generalized sites. As can be seen from the parameters given in

Table 5, Fe is predominantly divalent in kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) and trivalent in their high-temperature modifications.

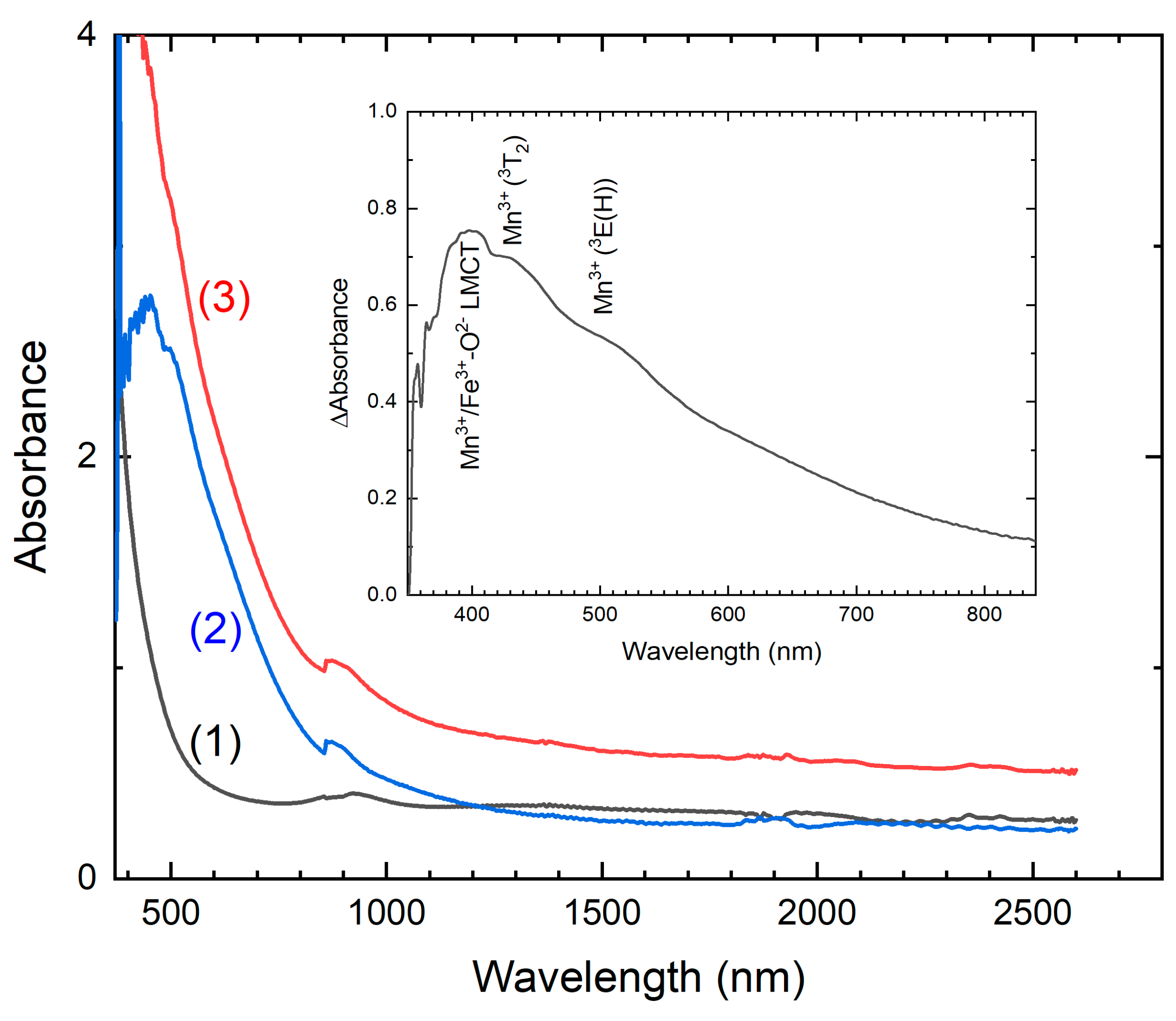

The optical absorption spectrum of the initial kupletskite (K25) exhibits an absortion edge at 380 nm, which can be attributed to

d-

d transitions of Mn

2+ ions (

Figure 9). The sharp structure corresponding to these transitions is not resolved due to the strong exchange interaction between Mn

2+ ions.

The optical absorption spectra of K600 shows increased absorption in the 400-600 nm spectral region. Analysis of the difference spectrum (

Figure 9) shows a UV band at approximately 400 nm that is attributed to ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) from Mn

3+ to O

2− and from Fe

3+ to O

2− [Hålenius, 2014]. The bands at 430 and 505 nm correspond to spin-allowed

d-

d transitions in Mn

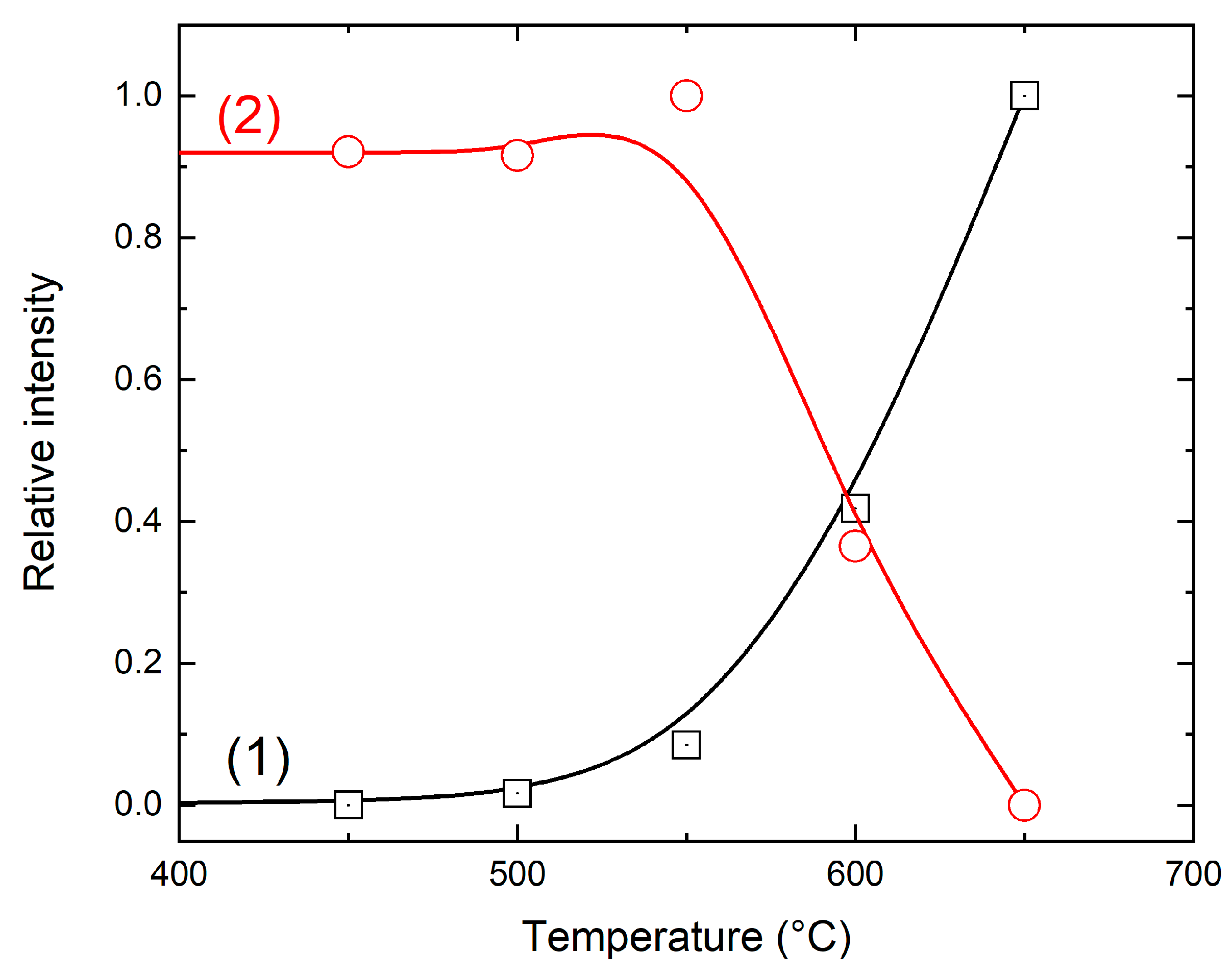

3+ ions [Czaja, 2018; Hålenius, 2014; Fridrichova, 2018]. The temperature dependencies of the Mn

3+-related absorption and the O‒H absorption band at 3628 cm

−1 are inversely correlated (

Figure 10) suggesting that oxidation of Mn ions from the divalent to the trivalent state is accompanied by dehydroxylation.

4. Discussion

Structural studies of two manganese heterophyllosilicates: kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) using powder and single-crystal X-ray diffraction show a discontinuous reduction in the unit-cell parameters at temperatures of about 500 °C and above. By analogy with the high-temperature behavior of astrophyllite [Zhitova et al., 2017a], bafertisite [Zhitova et al., 2017b] and lobanovite [Zhitova et al., 2019], it has been suggested that this transformation occurs due to dehydroxylation and iron oxidation. The changes of iron oxidation state are confirmed by Mössbauer spectroscopy, the reduction of O–H related bands is evident from infrared spectra. The contraction of the unit-cell volume is due to shortening of

M‒O bond lengths, since Fe

3+–O bonds are shorter than the Fe

2+–O bonds [Gagné and Hawthorne, 2020]. If only Fe oxidizes, then the degree of the unit-cell contraction should correlate with the content of Fe

2+. However, as can be seen from

Table 6, the unit-cell contraction is practically identical for kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and astrophyllite, despite different Fe

2+ content. For astrophyllite, we know that 4-5

apfu of Fe

2+ undergo oxidation, among which 4 are compensated by 4(OH)

‒ groups, and the 5-th by partial defluorination (F

– → O

2–) [Zhitova et al., 2017a]. For the samples studied here, the Fe

2+ apfu [2.22

apfu for kupletskite and 1.78

apfu for kupletskite-(Cs)] is much less. However, the degree of unit-cell volume contraction as a result of annealing is identical for kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and astrophyllite. The identical degree of volume contraction and reduction of metal-oxygen bond lengths in minerals with different Fe contents indicates that additional mechanism(s) of oxidation must occur during dehydroxylation. The change in Mn oxidation state [obtained by optical absorption spectroscopy (

Figure 9) is inversely correlated with the intensity of the O–H band in the infrared spectra, indicating the synchronicity of these processes (

Figure 10).

The following structural criteria have been calculated for each polyhedra: the (polyhedral) volume; bond-angle variance; distortion index and quadratic elongation (

Table 6). From the results in

Table 6, it is apparent that the main structural changes upon heating affect the O layer for both, kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs). The largest compression and distortion occur for the

M(2)O

6 octahedron, significant changes with similar distortion indices occur for the

M(3)O

6,

M(4)O

6 octahedra, and the smallest distortions occur for the

M(1)O

6 octahedron, which confirms our proposal that the non-oxidizing elements are concentrated at the

M(1) site. The distortions of the polyhedra of H layer are less significant and are most likely caused by the need to satisfy the valence-sum requirements in the structures of the high-temperature modifications. We did not record any significant changes in the bond geometry and/or position of the interlayer cations at the

A and

B sites (

Table 6). However, the thermal expansion figure for the HT modification of kupletskite-(Cs) is very different from those of kupletskite and astrophyllite since in the temperature range 500‒800 °C there is a volume expansion (not contraction) caused by expansion of the structure along the direction of layer stacking. If we carefully examine the evolution of the unit-cell parameters with temperature (

Figure 3), the interlayer distance,

d00n clearly reflects this difference: for astrophyllite and kupletskite, the interlayer distance of the high-temperature modification is smaller than that of the initial structures; for kupletskite-(Cs),

d00n does not fall below the initial room temperature value. It seems reasonable to suggest that this indicates the role of Cs ions in the stabilization of thermal expansion of the astrophyllite structural type, as Cs is larger than K [Hawthorne and Gagné, 2024] and its presence in the channels leads to a limitation on the minimum possible separation of the O layers.

We have shown for the first time, using heterophyllosilicates as an example, that temperature-induced oxidation of Mn occurs along with Fe, coupling with dehydroxylation of the O layer. Comparison of iron- and manganese-dominant minerals shows the structural identity of the oxidation reactions of these two elements. Taking into account the widespread occurrence of iron-oxidation reactions in rock-forming minerals: amphiboles, tourmalines, micas and clays, one can assume similar behavior for their manganese-dominant analogues. By analogy with the oxidation reactions of Fe, it seems reasonable to propose that oxidation of Mn can be implied in Earth processes at elevated temperatures and pressures, albeit on a more local scale than Fe due to the restricted distribution of Mn-rich rocks. The presence of dehydroxylated minerals (or their varieties) with trivalent manganese may also indicate heating to a temperature above 500 °C in an oxygen environment. The results obtained may also have applications in materials science, since these minerals have a porous structure and are capable of incorporating mono- and divalent cations, including Cs and transition d-elements.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1. Unit-cell parameters refined for kupletskite at different temperatures; Table S2. Unit-cell parameters refined for kupletskite-(Cs) at different temperatures; Table S3. Coefficients of equations used for approximation of unit-cell parameters of kupletskite and its HT modification; Table S4. Coefficients of equations used for approximation of unit-cell parameters of kupletskite-(Cs) and its HT modification; Table S5. The main characteristics of thermal expansion/contraction for kupletskite (angles are given in degrees, coefficients are × 10

6, °C

-1); Table S6. The main characteristics of thermal expansion/contraction for kupletskite-(Cs) (angles are given in degrees, coefficients are × 10

6, °C

-1); Table S7. Atom coordinates, equivalent isotropic-displacement parameters (Å

2), site occupancies for kupletskite (K25), kupletskite-(Cs) (CsK25) and their high-temperature modifications (K650 and CsK650); Table S8. Anisotropic-displacement parameters (Å

2) for kupletskite (K25), kupletskite-(Cs) (CsK25) and their high-temperature modifications (K650 and CsK650); Table S9. Selected bond-distances (Å) for for kupletskite (K25), kupletskite-(Cs) (CsK25) and their high-temperature modifications (K650 and CsK650). The crystal structure data for kupletskite (K25), kupletskite-(Cs) (CsK25) and their high-temperature modifications (K650 and CsK650) are available as CIF–files from the CCDC/FIZ Karlsruhe database as CSD # 2442952 (К25), 2442953 (К650), 2442954 (Cs650) and 2442955 (Cs25) at

https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.Z., and A.A.Z.; methodology, E.S.Z., A.A.Z., R.Yu.S., F.C.H.; software, E.S.Z., A.A.Z., R.M.S., R.Yu.S., F.C.H., A.A.N., N.S.K.; validation, E.S.Z., A.A.Z., R.M.S., R.Yu.S., F.C.H., A.A.N., E.V.K., V.N.Ya.; formal analysis, E.S.Z., A.A.Z., R.M.S., R.Yu.S., A.A.N., N.S.V.; investigation, E.S.Z., A.A.Z., R.M.S., R.Yu.S., F.C.H., A.A.N., N.S.V., E.V.K., V.N.Ya.; resources, E.S.Z., A.A.Z., V.N.Ya.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.Z., A.A.Z., R.M.S., R.Yu.S., F.C.H.; writing—review and editing, E.S.Z., A.A.Z., R.M.S., R.Yu.S., F.C.H., A.A.N., N.S.V., E.V.K., V.N.Ya.; visualization, E.S.Z., R.M.S., R.Yu.S.; supervision, E.S.Z., A.A.Z., F.C.H.; project administration, E.S.Z.; funding acquisition, E.S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 22-77-10036 for ESZ, AAZ, RMS, AAN and EVK). Technical support of the St. Petersburg State University Resource Centres "X-ray diffraction research methods" and "Geomodel" is carried out within the framework of SPbSU, grants No. 125021702335-5 and No. 124032000029-9, for both Resource Centres, respectively. FCH was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Acknowledgments

The infrared and UV/Vis absorption spectra were measured at the Center of Isotope and Geochemical Research for Collective Use (A. P. Vinogradov Institute of Geochemistry of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences) that is acknowledged. St. Petersburg State University Resource Centres "X-ray diffraction research methods" and "Geomodel" are also acknowledged for the equipment access. We thank the reviewers for their constructive comments and editors for processing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Belov, N.V. Essays on structural mineralogy, Nauka: Moscow, USSR, 1976; pp. 1‒344 (in Russian).

- Liebau F. Structural chemistry of silicates: structure, bonding and classification. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany, 1985.

- Ferraris, G. Modular structures–the paradigmatic case of the heterophyllosilicates. Z Kristallogr Cryst, 2008, 223(1-2), 76‒84.

- Sokolova, E., Cámara, F., Hawthorne, F.C., Ciriotti, M.E. The astrophyllite supergroup: nomenclature and classification. Mineral Mag, 2017, 81(1), 143‒153.

- Piilonen, P.C., Lalonde, A.E., McDonald, A.M., Gault, R.A., Larsen, A.O. Insights into astrophyllite-group minerals. I. Nomenclature, composition and development of a standardized general formula. Canad Mineral, 2003a, 41(1), 1‒26.

- Zhitova, E.S., Krivovichev, S.V., Hawthorne, F.C., Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G., Zolotarev, A.A., Abdu, Y.A., Yakovenchuk, V.N., Pakhomovsky, Ya.A., Goncharov, A.G. High-temperature behaviour of astrophyllite, K2NaFe72+Ti2(Si4O12)2O2(OH)4F: a combined X-ray diffraction and Mössbauer spectroscopic study. Phys Chem Miner, 2017a, 44, 595‒613.

- Zhitova, E.S., Zolotarev, A.A., Krivovichev, S.V., Goncharov, A.G., Gabdrakhmanova, F.A., Vladykin, N.V., Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G., Shilovskikh, V.V., Vlasenko, N.S., Zolotarev, A.A. Temperature-induced iron oxidation in bafertisite Ba2Fe42+Ti2(Si2O7)2O2(OH)2F2: X-ray diffraction and Mössbauer spectroscopy study. Hyperfine Interact, 2017b, 238, 1‒12.

- Zhitova, E.S., Zolotarev, A.A., Hawthorne, F.C., Krivovichev, S.V., Yakovenchuk, V.N., Goncharov, A.G. High-temperature Fe oxidation coupled with redistribution of framework cations in lobanovite, K2Na(Fe2+4Mg2Na)Ti2(Si4O12)2O2(OH)4 – the first titanosilicate case. Acta Crystallogr, 2019, 75(4), 578‒590.

- Brown, I.D. The Chemical Bond in Inorganic Chemistry. The Bond Valence Model. 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press, U.K., 2016; pp. 1‒344.

- Hawthorne, F.C. A bond-topological approach to theoretical mineralogy: crystal structure, chemical composition and chemical reactions. Phys Chem Min, 2012, 39, 841‒874. 39.

- Hawthorne, F.C. Toward theoretical mineralogy: a bond-topological approach. Am Min, 2015, 100, 696‒713.

- Russell, R.L. , Guggenheim, S. Crystal structures of near-endmember phlogopite at high temperatures and heat-treated Fe-rich phlogopite: the influence of the O, OH, F site. Canad Mineral, 1999, 37, 711–729. [Google Scholar]

- Chon, C-M., Lee, C-K., Song, Y., Kim, S.A. Structural changes and oxidation of ferroan phlogopite with increasing temperature: in situ neutron powder diffraction and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Phys Chem Miner, 2006, 33, 289–299. [CrossRef]

- Ventruti, G. , Zema, M., Scordari, F., Pedrazzi, G. Thermal behavior of a Ti-rich phlogopite from Mt. Vulture (Potenza, Italy): An in situ X-ray single-crystal diffraction study. Am Miner, 2008, 93, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zema, M. , Ventruti, G., Lacalamita, M., Scordari, F. Kinetics of Fe-oxidation/deprotonation process in Fe-rich phlogopite under isothermal conditions. Am Miner, 2010, 95, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, E. , Wagner, U. The thermal behaviuor of an Fe-rich illite. Clay Miner, 1996, 31, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güttler, B. , Niemann, W., Redfern, S.A.T. EXAFS and XANES spectroscopy study of the oxidation and deprotonation of biotite. Mineral Mag, 1989, 53, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veith, J.A. , Jackson, M.L. Iron oxidation and reduction effects on structural hydroxyl and layer charge in aqueous suspensions of micaceous vermiculites. Clays Clay Miner, 1974, 22, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korovushkin, V.V. , Kuzmin, V., Belov, V.F. Mossbauer studies of structural features in tourmaline of various genesis. Phys Chem Miner, 1979, 4, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrow, E.A. , Annersten, H., Gunawardane, R.P. Mössbauer effect study on the mixed valence state of iron in tourmaline. Mineral Mag, 1988, 52, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bačik, P. , Ozdin, D., Miglierini, M., Kardošova, P., Pentra, M., Haloda, J. Crystallochemical effects of heat treatment on Fedominant tourmalines from Dolni Bory (Czech Republic) and Vlachovo(Slovakia). Phys Chem Miner, 2011, 38, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, J. , Bosi, F., Novák, M., Skogby, H., Tuček, J., Čuda, J., Wildner, M. Iron redox reactions in the tourmaline structure: Hightemperature treatment of Fe3+-rich schorl. Geochim Cosmochim Acta, 2012, 86, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberti, R., Della Ventura, G., Dyar, M.D. Combining structure refinement and spectroscopies: hints and warnings for more efficient tolls to decipher the mechanism of deprotonation in amphiboles. Period Miner, 2015, ECMS 2015, 131–132.

- Della Ventura, G. FTIR spectroscopy at HT: applications and problems. Period Miner, 2015, ECMS 2015, 7–8.

- Susta, U., Della Ventura, G., Bellatreccia, F., Hawthorne, F.C., Oberti, R. HT-FTIR spectroscopy of riebeckite. Period Miner, 2015, ECMS 2015, 167–168.

- Della Ventura, G., Redhammer, G.J., Galdenzi, F., Ventruti, G., Susta, U., Oberti, R., Radica, F., Marcelli, A. Oxidation or cation re-arrangement? Distinct behavior of riebeckite at high temperature. Am Min, 2023a, 108(1), 59‒69.

- Mihailova, B., Della Ventura, G., Waeselmann, N., Bernardini, S., Wei, Xu, Marcelli. Polarons in rock-forming minerals: physical implications. Condens Matter, 2022, 7, 68.

- Della Ventura, G., Galdenzi, F., Marcelli, A., Cibin, G., Oberti, R., Hawthorne, F.C., Bernardini, S. Mihailova, B. In situ simultaneous Fe K-edge XAS spectroscopy and resistivity measurements of riebeckite: Implications for anomalous electrical conductivity in subduction zones. Geochem., 2023b. [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, S. , Della Ventura, G., Schlüter, J., Hawthorne, F.C., Mihailova, B. The effect of A-site cations on charge-carrier mobility in Fe-rich amphiboles. Am Min, 2024, 109, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, S., Della Ventura, G., Hawthorne, F.C., Marcelli, A., Salvini, F., Mihailova, B. The effect of anisotropic electrical conductivity of amphiboles on geophysical anomalies observed in subduction zones. Sci. Rep., 2025, accepted.

- Della Ventura, G., Bernardini, S., Redhammer, J.G., Galdenzi, F., Radica, F., Marcelli, A., Hawthorne F.C., Oberti, R., Mihailova, B. The oxidation of iron in amphiboles at high temperatures: a review and implications for large-scale Earth processes. Rend Lincei Sci Fis Nat, 2024, 1‒14.

- Ferraris, G. Heterophyllosilicates, a potential source of nanolayers for materials science. In Minerals as Advanced Materials I; Krivovichev S.V. Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Germany, 2008, pp. 157–163.

- Ferraris, G., Merlino, S. Micro-and mesoporous mineral phases; Washington DC: Mineralogical Society of America, USA, 2005; Vol. 57, pp. 1–448.

- Lin, Z.; Paz, F. A. A.; Rocha, J. Layered titanosilicates. In Layered Mineral Structures and their Application in Advanced Technologies; Brigatti, M.F.; Mottana A. Eds.; Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland, UK, 2011; Volume 11, pp. 10.1180/EMU-notes.11.3.

- Aksenov, S.M.; Yamnova, N.A.; Chukanov, N.V.; Kabanova, N.A.; Kobeleva, E.A.; Deyneko, D.V.; Krivovichev, S.V. Theoretical analysis of cation-migration paths in microporous heterophyllosilicates with astrophyllite and veblenite type structures. J. Struct. Chem., 2022, 63(2), 293–301.

- Yakovenchuk V.; Ivanyuk G.; Pakhomovsky Ya.; Men’shikov Yu. Khibiny. Laplandia Minerals: Apatity, Russia, 2005.

- Yefimov, A.F. , Dusmatov, V.D., Ganzeyev, A.A., Katayeva, Z.T. Cesium kupletskite, a new mineral. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR, 1971, 197, 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bruker AXS. Topas V4.2: General Profile and Structure Analysis Software for Powder Diffraction Data. Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany, 2009.

- Belousov, R., Filatov, S. Algorithm for calculating the thermal expansion tensor and constructing the thermal expansion diagram for crystals. Glass Phys Chem, 2007, 33(3), 271–275.

- Bubnova, R.S., Firsova, V.A., Filatov, S.K. Software for determining the thermal expansion tensor and the graphic representation of its characteristic surface (theta to tensor-TTT). Glass Phys Chem, 2013, 39(3), 347–350.

- Langreiter, T., Kahlenberg, V. TEV—a program for the determination of the thermal expansion tensor from diffraction data. Crystals, 2015, 5(1), 143‒153.

- Bruker AXS. APEX2. Version 2014.11-0. Bruker AXS, Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2014.

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure solution with ShelXT. Acta Crystallogr, 2015, A71, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov, O.V. , Bourhis, L.J., Gildea, R.J., Howard, J.A.K., Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analisis program. Appl. Crystallogr, 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara, F., Sokolova, E., Abdu, Y., Hawthorne, F. C. The crystal structures of niobophyllite, kupletskite-(Cs) and Sn-rich astrophyllite: revisions to the crystal chemistry of the astrophyllite-group minerals. Canad Mineral, 2010, 48(1), 1‒16.

- Woodrow, P.J. The crystal structure of astrophyllite. Acta Crystallogr, 1967, 22(5), 673‒678.

- Piilonen, P.C., McDonald, A.M., Lalonde, A.E. Insights into astrophyllite-group minerals. II. Crystal chemistry. Canad Mineral, 2003b, 41(1), 27‒54.

- Sokolova, E. Further developments in the structure topology of the astrophyllite-group minerals. Mineral Mag, 2012, 76(4), 863‒882.

- Hålenius, U., Bosi, F. Color of Mn-bearing gahnite: A first example of electronic transitions in heterovalent exchange coupled IVMn2+–VIMn3+ pairs in minerals. Am Min, 2014, 99(2‒3), 261‒266. [CrossRef]

- Czaja, M. , Lisiecki, R., Chrobak, A., Sitko, R., Mazurak, Z. The absorption-and luminescence spectra of Mn3+ in beryl and vesuvianite. Phys Chem Miner, 2018, 45, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridrichová, J., Bačík, P., Ertl, A., Wildner, M., Dekan, J., Miglierini, M. Jahn-Teller distortion of Mn3+-occupied octahedra in red beryl from Utah indicated by optical spectroscopy. J Mol Struct, 2018, 1152, 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Gagné, O.C., Hawthorne, F.C. Bond-length distributions for ions bonded to oxygen: Results for the transition metals and quantification of the factors underlying bond-length variation in inorganic solids. IUCrJ, 2020, 7, 581–629.

- Hawthorne, F.C. , Gagné, O.C. New ion radii for oxides and oxysalts, fluorides, chlorides and nitrides. Acta Cryst., 2024, B80, 326–339. [Google Scholar]

- Momma, K., Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr, 2011, 44(6), 1272‒1276.

Figure 1.

The astrophyllite structure-type of alternating octahedral and heteropolyhedral layers.

Figure 1.

The astrophyllite structure-type of alternating octahedral and heteropolyhedral layers.

Figure 2.

The evolution of the powder X-ray diffraction pattern of kupletskite / kupletskite-(Cs) with temperature.

Figure 2.

The evolution of the powder X-ray diffraction pattern of kupletskite / kupletskite-(Cs) with temperature.

Figure 3.

Temperature dependencies of the unit-cell parameters and d001-spacings for kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) compared to astrophyllite [Zhitova et al., 2017a] (ESDs fall within the limits of the symbols).

Figure 3.

Temperature dependencies of the unit-cell parameters and d001-spacings for kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs) compared to astrophyllite [Zhitova et al., 2017a] (ESDs fall within the limits of the symbols).

Figure 4.

The crystal structure of kupletskite / kupletskite-(Cs) (the unit cell is shown by the thin black lines) (a) and their figures of their thermal expansion for kupletskite at T = 300 °C (b), high-temperature modification of kupletskite at T = 650 °C (c), kupletskite-(Cs) at T = 300 °C (d) and high-temperature modification of kupletskite-(Cs) at T = 650 °C (e).

Figure 4.

The crystal structure of kupletskite / kupletskite-(Cs) (the unit cell is shown by the thin black lines) (a) and their figures of their thermal expansion for kupletskite at T = 300 °C (b), high-temperature modification of kupletskite at T = 650 °C (c), kupletskite-(Cs) at T = 300 °C (d) and high-temperature modification of kupletskite-(Cs) at T = 650 °C (e).

Figure 5.

The bond topology of the O layer in the crystal structure of kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and astrophyllite; the M(1)-M(4) sites are shown by different colors. The protonated oxygen atoms are designated as OH(4) (pink) and OH(5) (grey).

Figure 5.

The bond topology of the O layer in the crystal structure of kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and astrophyllite; the M(1)-M(4) sites are shown by different colors. The protonated oxygen atoms are designated as OH(4) (pink) and OH(5) (grey).

Figure 6.

The topology of the H layer in the crystal structure of kupletskite/kupletskite-(Cs) (left) and their high-temperature modification (right). Comparison of the images shows a change in the rotation of the Dφ6 octahedra and distortions in the geometry of the T4O12 chains.

Figure 6.

The topology of the H layer in the crystal structure of kupletskite/kupletskite-(Cs) (left) and their high-temperature modification (right). Comparison of the images shows a change in the rotation of the Dφ6 octahedra and distortions in the geometry of the T4O12 chains.

Figure 7.

Infrared spectra of (a) kupletskite and (b) its high-temperature modification; (c) kupletskite-(Cs) and (d) its high-temperature modification.

Figure 7.

Infrared spectra of (a) kupletskite and (b) its high-temperature modification; (c) kupletskite-(Cs) and (d) its high-temperature modification.

Figure 8.

The ATR infrared spectra of kupletskite (K25) and its high-temperature modifications (K550, K600 and K650) in the 1700-600 cm-1 (a) and 3800-3300 cm-1 (b) ranges.

Figure 8.

The ATR infrared spectra of kupletskite (K25) and its high-temperature modifications (K550, K600 and K650) in the 1700-600 cm-1 (a) and 3800-3300 cm-1 (b) ranges.

Figure 9.

Optical absorption spectra of kupletskite, K25 (curve 1) and its high-temperature modifications K550 (curve 2) and K600 (curve 3). In the inset, the difference spectrum of the spectra recorded from K25 and K550 is given.

Figure 9.

Optical absorption spectra of kupletskite, K25 (curve 1) and its high-temperature modifications K550 (curve 2) and K600 (curve 3). In the inset, the difference spectrum of the spectra recorded from K25 and K550 is given.

Figure 10.

Temperature dependences of Mn3+ absorption (1) and in tensity of the O–H related band at 3628 cm−1 (2).

Figure 10.

Temperature dependences of Mn3+ absorption (1) and in tensity of the O–H related band at 3628 cm−1 (2).

Table 1.

Crystallographic data, data collection and refinement parameters for kupletskite (K25), kupletskite-(Cs) (CsK25) and their high-temperature modifications (K650 and CsK650).

Table 1.

Crystallographic data, data collection and refinement parameters for kupletskite (K25), kupletskite-(Cs) (CsK25) and their high-temperature modifications (K650 and CsK650).

| Sample |

K25 |

K650 |

CsK25 |

CsK650 |

| Crystal data |

| Crystal system |

Triclinic |

Triclinic |

Triclinic |

Triclinic |

| Space group |

P-1 |

P-1 |

P-1 |

P-1 |

Unit-cell dimensions

a, b, c (Å),

α, β, γ (°) |

5.3976(2)

11.9431(7)

11.7092(6)

113.066(5)

94.702(4)

103.086(4) |

5.3233(5)

11.8826(14)

11.5362(12)

112.756(10)

93.699(8)

104.462(9) |

5.3904(10)

11.946(2)

11.799(2)

113.135(5)

94.573(6)

103.115(17) |

5.312(2)

11.832(4)

11.739(5)

112.996(10)

93.587(10)

104.39(4) |

| Unit-cell volume (Å3) |

664.06(6) |

640.90(13) |

668.2(2) |

647.3(5) |

| Z |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Calculated density (g/cm-3) |

3.274 |

3.354 |

3.635 |

3.726 |

| Absorption coefficient (μ/mm-1) |

4.992 |

4.481 |

6.204 |

6.244 |

| Data collection |

| Diffractometer |

Bruker APEX II |

| Temperature (K) |

293 K |

| Radiation |

MoKα |

| 2θ range (°) |

3.852-72.8 |

3.892-72.88 |

3.864-59.99 |

3.832-59.986 |

|

h, k, l ranges |

-8 ≤ h ≤ 8,

-19 ≤ k ≤ 19,

-18 ≤ l ≤ 19 |

-8 ≤ h ≤ 8,

-19 ≤ k ≤ 19,

-18 ≤ l ≤ 18 |

-7 ≤ h ≤ 7,

-16 ≤ k ≤ 16,

-14 ≤ l ≤ 16 |

-7 ≤ h ≤ 7,

-16 ≤ k ≤ 16,

-16 ≤ l ≤ 16 |

| F(000) |

634.0 |

625.0 |

693.0 |

686.0 |

| Total reflections collected |

12050 |

11358 |

8686 |

12060 |

| Unique reflections (Rint) |

6044

(0.0325) |

5837

(0.0303) |

3591

(0.0518) |

3766

(0.0476) |

| Unique reflections F > 4σ(F) |

4768 |

4531 |

2667 |

2831 |

| Structure refinement |

| Refinement method |

Full-matrix least-squares on F2

|

| Data/ restrains/parameters |

6044/2/253 |

5837/0/245 |

3591/2/256 |

3766/0/251 |

R1 [F > 4σ(F)],

wR2 [F > 4σ(F)] |

0.0433,

0.1119 |

0.0416,

0.1002 |

0.0323,

0.0715 |

0.0476,

0.1108 |

|

R1 all, wR2 all |

0.0590,

0.1232 |

0.0611,

0.1110 |

0.0657,

0.0904 |

0.0697,

0.1229 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2

|

1.051 |

1.037 |

1.061 |

1.044 |

| Largest diff. peak and hole (ēÅ-3) |

1.29/-1.81 |

1.57/-1.37 |

1.72/-1.45 |

1.29/-1.52 |

Table 2.

Chemical composition of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs).

Table 2.

Chemical composition of kupletskite and kupletskite-(Cs).

| Mineral |

Kupletskite |

Kupletskite-(Cs) |

Constituent |

Kupletskite |

Kupletskite-(Cs) |

| n |

22 |

27 |

Constituent |

| Constituent, wt. % |

average |

range |

average |

range |

apfu, calculated as Si + Al = 8 |

| Na2O |

2.77 |

2.64‒2.93 |

2.11 |

1.76‒2.83 |

Na |

1.15 |

1.00 |

| K2O |

6.22 |

6.03‒6.38 |

0.73 |

0.61‒0.95 |

K |

1.70 |

0.23 |

| CaO |

1.43 |

1.27‒1.59 |

0.73 |

0.56‒0.92 |

Ca |

0.33 |

0.19 |

| Cs2O |

- |

- |

14.40 |

14.25‒15.20 |

Cs |

- |

1.50 |

| PbO |

- |

- |

0.37 |

0‒1.09 |

Pb |

- |

0.02 |

| MgO |

1.42 |

1.29‒1.55 |

0.04 |

0‒0.25 |

Mg |

0.45 |

0.01 |

| MnO |

18.62 |

17.05‒20.16 |

17.79 |

17.41‒18.37 |

Mn |

3.37 |

3.68 |

| FeO(1)

|

11.82 |

14.23‒17.20 |

8.74 |

10.54‒11.72 |

Fe2+

|

2.11 |

1.78 |

| Fe2O3

|

4.15 |

2.57 |

Fe3+

|

0.67 |

0.47 |

| Li2O(2)

|

- |

- |

0.74 |

- |

Li |

- |

0.73 |

| Al2O3

|

0.81 |

0.64‒1.19 |

0.12 |

0‒0.48 |

Al |

0.20 |

0.03 |

| TiO2

|

11.18 |

10.88‒11.48 |

6.96 |

5.83‒8.04 |

Ti |

1.80 |

1.28 |

| Nb2O5

|

2.12 |

1.83‒2.23 |

6.35 |

5.17‒8.56 |

Nb |

0.20 |

0.70 |

| SiO2

|

36.47 |

35.80‒37.89 |

32.62 |

32.11‒33.26 |

Si |

7.80 |

7.97 |

| F |

1.19 |

0.68‒1.63 |

0.84 |

0.65‒1.19 |

F |

0.80 |

0.65 |

| H2O(3)

|

2.67 |

- |

2.35 |

- |

OH |

3.80 |

3.83 |

| O(3)

|

0.50 |

- |

0.58 |

- |

O |

0.20 |

0.52 |

| 2F = O |

-0.50 |

- |

-0.35 |

- |

|

|

|

| Total |

100.87 |

|

99.60 |

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

The main characteristics of thermal expansion/contraction for kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) at T = 300 °C and their high-temperature modifications at T = 650 °C (angles are given in degrees, coefficients are × 106, °C-1).

Table 3.

The main characteristics of thermal expansion/contraction for kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) at T = 300 °C and their high-temperature modifications at T = 650 °C (angles are given in degrees, coefficients are × 106, °C-1).

|

T, °C |

α11

|

α22

|

α33

|

<α11a

|

<α22b

|

<α33c

|

αa

|

αb

|

αc

|

αα

|

αβ

|

αγ

|

αV

|

| Kupletskite |

| 300 |

4.3 |

11.5 |

6.7 |

24.9 |

12.2 |

20 |

4.9(4) |

11.2(4) |

6.7(3) |

-0.01(9) |

0.6(2) |

0.2(2) |

22.5(6) |

| Kupletskite-(Cs) |

| 300 |

-3.4 |

1.6 |

17.1 |

47 |

33.9 |

26.7 |

-1(1) |

0.1(7) |

13.3(7) |

-3.7(4) |

-2.0(4) |

2.7(4) |

15(2) |

| High-temperature modification of kupletskite |

| 650 |

-39.2 |

-19.9 |

-11.8 |

27.3 |

35.4 |

22.3 |

-34(2) |

-23(1) |

-15(2) |

5(2) |

-9(2) |

-6(1) |

-71(3) |

| High-temperature modification of kupletskite-(Cs) |

| 650 |

3.2 |

-6.7 |

10.3 |

26.9 |

10.8 |

39.5 |

2(1) |

-6(2) |

5.5(6) |

-4.1(4) |

0.6(9) |

-3(1) |

7(2) |

Table 4.

Selected site-scattering values and bond lengths for kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and their high-temperature modifications.

Table 4.

Selected site-scattering values and bond lengths for kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and their high-temperature modifications.

| Sample |

Kupletskite |

HT kupletskite |

Kupletskite-(Cs) |

HT kupletskite-(Cs) |

Astrophyllite |

HT astrophyllite |

|

V, Å3

|

664.1 |

640.9 |

668.2 |

647.3 |

655.5 |

633.0 |

| ΔV/V, % |

-3.5 |

-3.1 |

-3.4 |

| Octahedra M(1)O6

|

|

ē M(1) |

23.05 |

21.10 |

21.75 |

19.28 |

23.69 |

21.14 |

| Δē M(1) |

-2.0 |

-2.5 |

-2.6 |

|

<M(1)–O>, Å |

2.203 |

2.219 |

2.193 |

2.197 |

2.176 |

2.185 |

|

Δ<M(1)–O>, Å |

+0.016 |

+0.004 |

+0.009 |

| Octahedra M(2)O6

|

|

ēM(2) |

25.00 |

23.83 |

25.00 |

24.61 |

25.06 |

23.01 |

| ΔēM(2) |

-1.2 |

-0.4 |

-2.0 |

|

<M(2)–O>, Å |

2.174 |

2.091 |

2.179 |

2.089 |

2.156 |

2.102 |

|

Δ<M(2)–O>, Å |

-0.083 |

-0.090 |

-0.054 |

| Octahedra M(3)O6

|

|

ēM(3) |

24.61 |

24.48 |

23.83 |

24.61 |

24.18 |

24.28 |

| ΔēM(3) |

-0.1 |

+0.8 |

+0.1 |

|

<M(3)–O>, Å |

2.162 |

2.117 |

2.167 |

2.108 |

2.144 |

2.097 |

|

Δ<M(3)–O>, Å |

-0.045 |

-0.059 |

-0.047 |

| Octahedra M(4)O6

|

|

ēM(4) |

23.31 |

24.09 |

25.00 |

24.22 |

23.51 |

24.15 |

| ΔēM(4) |

+0.8 |

-0.8 |

+0.6 |

|

<M(4)–O>, Å |

2.133 |

2.047 |

2.138 |

2.049 |

2.128 |

2.059 |

|

Δ<M(4)–O>, Å |

-0.086 |

-0.089 |

-0.069 |

| Octahedra Dφ6

|

|

D‒O(2), Å |

1.808 |

1.902 |

1.855 |

1.960 |

1.811 |

1.952 |

|

D‒XPD, Å |

2.088 |

2.002 |

2.051 |

1.993 |

2.100 |

1.982 |

|

<D–φ>, Å |

1.958 |

1.946 |

1.959 |

1.964 |

1.958 |

1.945 |

| Tetrahedra TO4

|

|

<T1–O>, Å |

1.623 |

1.620 |

1.618 |

1.614 |

1.615 |

1.607 |

|

<T2–O>, Å |

1.629 |

1.618 |

1.627 |

1.613 |

1.625 |

1.620 |

|

<T3–O>, Å |

1.637 |

1.627 |

1.627 |

1.625 |

1.632 |

1.624 |

|

<T4–O>, Å |

1.620 |

1.614 |

1.618 |

1.611 |

1.614 |

1.606 |

| Extraframework sites A, B

|

|

<A1–φ>, Å |

3.283 |

3.225 |

3.336 |

3.318 |

3.298 |

3.243 |

| <A2–φ>, Å |

3.299 |

|

3.226 |

3.369 |

3.345 |

- |

- |

|

<B–φ>, Å |

2.621 |

2.595 |

2.648 |

2.629 |

2.615 |

2.548 |

| Reference |

This work |

This work |

Zhitova et al., 2017a |

Table 5.

Mössbauer parameters for kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and their high-temperature modifications.

Table 5.

Mössbauer parameters for kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and their high-temperature modifications.

| |

δ0 (mm/s) |

δ1

|

Component |

∆ (mm/s) |

δ∆ (mm/s) |

Rel. Area (%) |

| Kupletskite, K25 |

| Fe2+

|

1.157 |

0.014 |

Component 1 |

2.379 |

0.410 |

45 |

| 1.141 |

0.010 |

Component 2 |

1.939 |

0.384 |

31 |

| Fe3+

|

0.259 |

0.003 |

Component 1 |

-0.002 |

1.000 |

24 |

| Kupletskite-(Cs), CsK25 |

| Fe2+

|

1.161 |

0.003 |

Component 1 |

2.380 |

0.505 |

79 |

| Fe3+

|

0.066 |

0.007 |

Component 2 |

0.430 |

0.365 |

21 |

| High-temperature modification of kupletskite, K650 |

| Fe3+

|

0.376 |

-0.006 |

Component 1 |

2.375 |

0.304 |

6 |

| |

0.690 |

-0.042 |

Component 2 |

1.356 |

0.465 |

77 |

| |

0.502 |

-0.013 |

Component 3 |

1.413 |

0.184 |

17 |

| High-temperature modification of kupletskite-(Cs), CsK600 |

| Fe3+

|

0.699 |

0.020 |

Component 1 |

1.646 |

0.370 |

48 |

| Fe3+

|

0.613 |

0.017 |

Component 2 |

1.135 |

0.453 |

52 |

Table 6.

Geometrical parameters derived from the crystal structures of kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and their high-temperature modifications.

Table 6.

Geometrical parameters derived from the crystal structures of kupletskite, kupletskite-(Cs) and their high-temperature modifications.

| Parameter |

Sample |

M(1) |

M(2)

|

M(3)

|

M(4)

|

|

toct, Å |

K |

2.49 → 2.38 |

2.47 → 2.29 |

2.47 → 2.32 |

2.42 → 2.31 |

| CsK |

2.49 → 2.36 |

2.48 → 2.28 |

2.47 → 2.30 |

2.42 → 2.29 |

| Bond angle variance, °2

|

K |

59.3 → 93.7 |

46.5 → 94.6 |

41.9 → 88.0 |

39.1 → 37.3 |

| CsK |

59.7 → 94.7 |

47.1 → 101.0 |

45.1 → 90.7 |

43.7 → 44.18 |

|

Voctahedra, Å3

|

K |

13.88 → 13.94 |

13.44 → 11.64 |

13.23 → 12.17 |

12.72 → 11.22 |

| CsK |

13.69 → 13.53 |

13.50 → 11.52 |

13.28 → 12.00 |

12.78 → 11.2 |

| Distortion index |

K |

0.007 → 0.017 |

0.026 → 0.072 |

0.017 → 0.029 |

0.014 → 0.041 |

| CsK |

0.006 → 0.018 |

0.027 → 0.079 |

0.019 → 0.031 |

0.015 → 0.042 |

| Quadratic elongation |

K |

1.0179 → 1.0299 |

1.0152 → 1.0382 |

1.0132 → 1.0280 |

1.0123 → 1.0156 |

| CsK |

1.0180 → 1.0304 |

1.0155 → 1.0437 |

1.0144 → 1.0292 |

1.0138 → 1.0179 |

| |

|

T(1) |

T(2)

|

T(3)

|

T(4)

|

|

Vtetrahedra, Å3

|

K |

2.19 → 2.17 |

2.21 → 2.17 |

2.24 → 2.20 |

2.18 → 2.15 |

| CsK |

2.17 → 2.15 |

2.21 → 2.15 |

2.20 → 2.19 |

2.17 → 2.14 |

| Distortion index |

K |

0.008 → 0.011 |

0.006→ 0.004 |

0.008 → 0.005 |

0.007 → 0.010 |

| CsK |

0.009 → 0.012 |

0.011 → 0.003 |

0.009 → 0.006 |

0.009 → 0.009 |

| Quadratic elongation |

K |

1.0021 → 1.0018 |

1.0013 → 1.0015 |

1.0018 → 1.0030 |

1.0021 → 1.0015 |

| CsK |

1.0019 → 1.0018 |

1.0018→ 1.0022 |

1.0024 → 1.0040 |

1.0019 → 1.0015 |

| |

|

D |

A |

B |

|

|

Vpolyhedra, Å3

|

K |

9.78 → 9.68 |

72.8 → 69.8 |

34.52 → 33.18 |

|

| CsK |

9.89 → 9.88 |

74.8 → 72.5 |

35.65 → 34.33 |

|

| Distortion index |

K |

0.026 → 0.011 |

0.091 → 0.82 |

0.013 → 0.060 |

|

| CsK |

0.018 → 0.008 |

0.043 → 0.049 |

0.010 → 0.063 |

|

| Quadratic elongation |

K |

1.0179 → 1.0102 |

1.1500 → 1.1510 |

|

|

| CsK |

1.0097 → 1.0049 |

1.1688 → 1.1770 |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).