Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

17 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mental Health

3. Gut Microbiota Involvement in Neurological Diseases

5. Improvement of Brain Function

6. Diet and Nutrition Impact on Mental Health

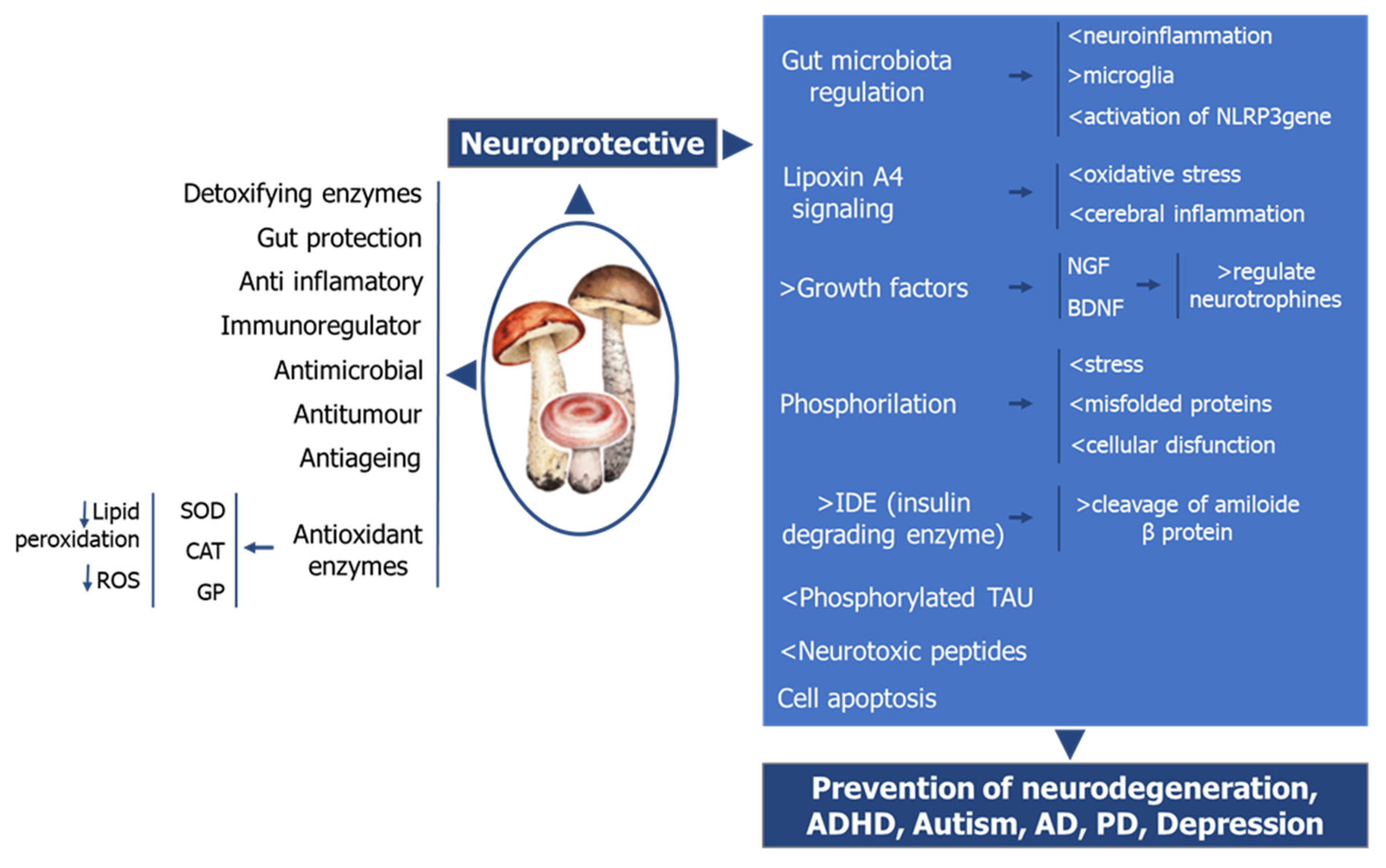

7. The Role of Mushrooms on Neurologic Health

|

7.1. Lentinula edodes (“Shiitake”)

7.2. Grifola frondosa (“Maitake”)

7.3. Coriolus versicolor (“Turkey Tail”)

7.4. Mixture Hericium erinaceus and Coriolus versicolor

7.5. Inonotus obliquus (“Chaga”)

7.6. Hericium erinaceus (“Lion´s Mane”)

7.7. Cordyceps (“Caterpillar”)

7.8. Ganoderma lucidum (“Reishi”)

7.9. Pleurotus (“King Oyster”)

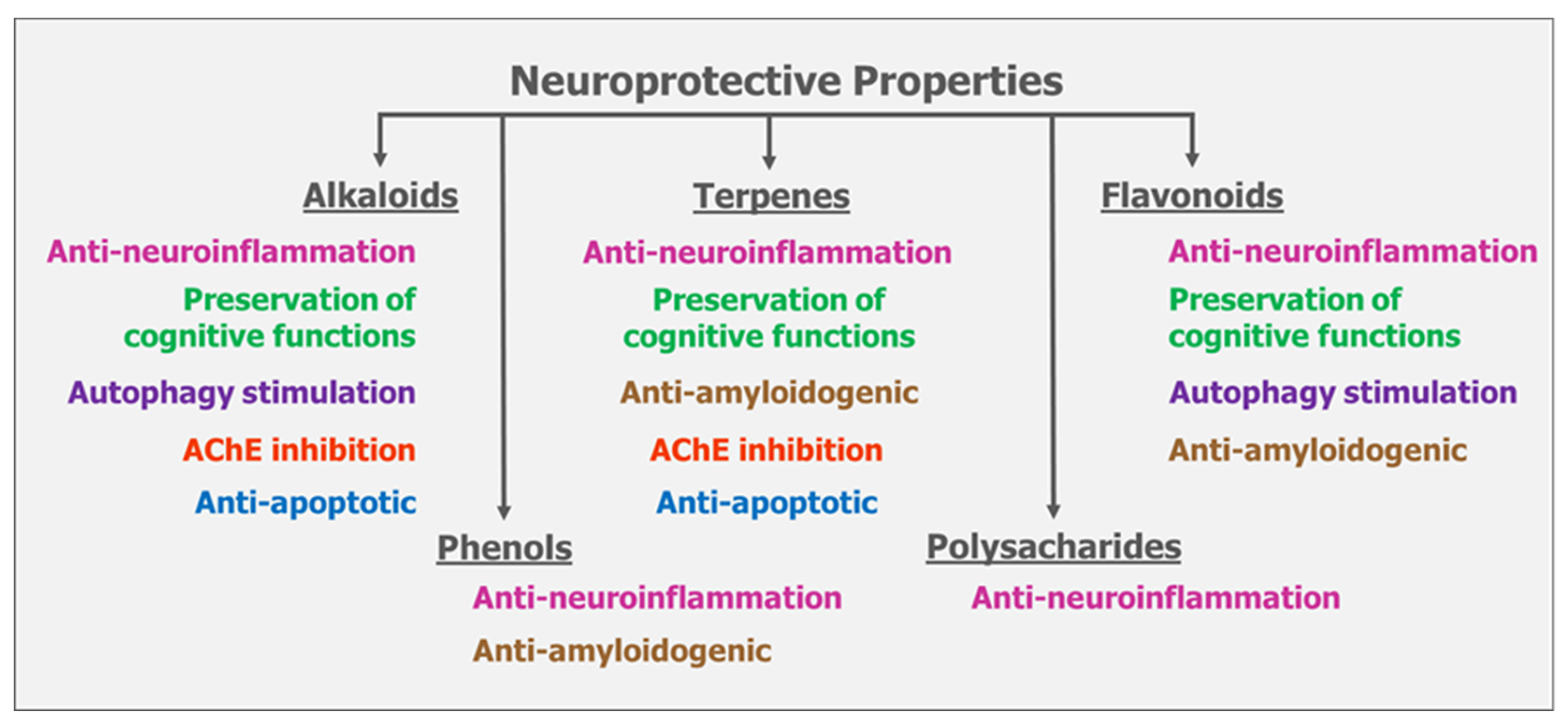

8. Summary on the Mode of Actions of Mushrooms on Neuroprotection

9. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reynolds, C.F.; Jeste, D. V.; Sachdev, P.S.; Blazer, D.G. Mental Health Care for Older Adults: Recent Advances and New Directions in Clinical Practice and Research. World psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. 2022, 21, 336–363. [CrossRef]

- WHO Mental Health of Adolescents Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Dou, L.; Yan, M.; Shen, T.; Tang, W.; Li, J. Aging and Aging-Related Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Interventions and Treatments. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022 71 2022, 7, 1–40. [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.W.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, C.; Kim, Y.T. Natural Products and Their Neuroprotective Effects in Degenerative Brain Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11223. [CrossRef]

- 2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [CrossRef]

- Singh, O. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2030: We Must Rise to the Challenge. Indian J. Psychiatry 2021, 63, 415–417. [CrossRef]

- Dumurgier, J.; Tzourio, C. Epidemiology of Neurological Diseases in Older Adults. Rev. Neurol. (Paris). 2020, 176, 642–648. [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.J.; Palk, A.C.; Kendler, K.S. What Is a Mental Disorder? An Exemplar-Focused Approach. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 894–901. [CrossRef]

- Healthdirect Australia Mental Illness - Types, Causes and Diagnosis of Mental Health Issues Available online: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/mental-illness (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Burback, L.; Brémault-Phillips, S.; Nijdam, M.J.; McFarlane, A.; Vermetten, E. Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A State-of-the-Art Review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 22, 557–635. [CrossRef]

- WHO ICD-11 2022 Release Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/11-02-2022-icd-11-2022-release (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Amand-Eeckhout, L. World Mental Health Day 2024: 10 October; 2024;

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation Global Health Data Exchange Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Moitra, M.; Santomauro, D.; Collins, P.Y.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.; Saxena, S.; Ferrari, A.J. The Global Gap in Treatment Coverage for Major Depressive Disorder in 84 Countries from 2000–2019: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Meta-Regression Analysis. PLOS Med. 2022, 19, e1003901. [CrossRef]

- Common Comorbidities with Substance Use Disorders Research Report; National Institutes on Drug Abuse (US), 2020;

- Lopes, A.G.; Laís, ; Cezário, R.A.; Fábio, ;; Mialhe, L. The Influence of Socioeconomic and Behavioural Factors on the Caries Experience of Adults with Mental Disorders in a Large Brazilian Metropolis. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 2024, 58, 149.

- Colizzi, M.; Lasalvia, A.; Ruggeri, M. Prevention and Early Intervention in Youth Mental Health: Is It Time for a Multidisciplinary and Trans-Diagnostic Model for Care? Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, S. Evidence Review: The Primary Prevention of Mental Health Conditions; Melboune, Australia, 2020;

- Fusar-Poli, P.; Correll, C.U.; Arango, C.; Berk, M.; Patel, V.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Preventive Psychiatry: A Blueprint for Improving the Mental Health of Young People. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 200–221. [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research; Mrazek, P.J., Haggerty, R.J., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC), 1994;

- Galderisi, S.; Appelbaum, P.S.; Gill, N.; Gooding, P.; Herrman, H.; Melillo, A.; Myrick, K.; Pathare, S.; Savage, M.; Szmukler, G.; et al. Ethical Challenges in Contemporary Psychiatry: An Overview and an Appraisal of Possible Strategies and Research Needs. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 364–386. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Tao, M.; Cao, H.; Yuan, H.; Ye, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Zhu, C. Changing Trends in the Global Burden of Mental Disorders from 1990 to 2019 and Predicted Levels in 25 Years. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2023, 32, e63. [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; Moseley, G.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F. Nutritional Psychiatry: The Present State of the Evidence. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 427–436. [CrossRef]

- Sugden, S.G.; Merlo, G. What Do Climate Change, Nutrition, and the Environment Have to Do With Mental Health? Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bell, V.; Fernandes, T.H. Mushrooms as Functional Foods for Ménière’s Disease. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Grabska-Kobyłecka, I.; Szpakowski, P.; Król, A.; Książek-Winiarek, D.; Kobyłecki, A.; Głąbiński, A.; Nowak, D. Polyphenols and Their Impact on the Prevention of Neurodegenerative Diseases and Development. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Osakabe, N.; Anfuso, C.D.; Jacob, U.M.; Sidenkova, A.; Fritsch, T.; Abdelhameed, A.S.; Rashan, L.; Wenzel, U.; Calabrese, E.J.; Calabrese, V. Phytochemicals and Vitagenes for a Healthy Brain. In Brain and Mental Health in Ageing; Kaur, G., Rattan, S.I.S., Eds.; Springer, Cham, 2024; pp. 215–253 ISBN 978-3-031-68513-2.

- Ciancarelli, I.; Morone, G.; Iosa, M.; Cerasa, A.; Calabrò, R.S.; Tozzi Ciancarelli, M.G. Neuronutrition and Its Impact on Post-Stroke Neurorehabilitation: Modulating Plasticity Through Diet. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3705. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Parisi, A.; Seminara, F.; Vernuccio, L.; Catanese, G.; Barbagallo, M. Mediterranean Diet and Lifestyle in Persons with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Wren-Lewis, S.; Alexandrova, A. Mental Health Without Well-Being. J. Med. Philos. 2021, 46, 684–703. [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride, J.B.; Anglin, D.M.; Colman, I.; Dykxhoorn, J.; Jones, P.B.; Patalay, P.; Pitman, A.; Soneson, E.; Steare, T.; Wright, T.; et al. The Social Determinants of Mental Health and Disorder: Evidence, Prevention and Recommendations. World psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. 2024, 23, 58–90. [CrossRef]

- Selloni, A. Social Determinants of Psychosis: An Examination of Loneliness, Stress, Discrimination, and Neighborhood Cohesion in Psychotic Disorders, City University of New York (CUNY), 2024.

- WHO Mental Health Available online: https://dev-cms.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Belfiore, C.I.; Galofaro, V.; Cotroneo, D.; Lopis, A.; Tringali, I.; Denaro, V.; Casu, M. A Multi-Level Analysis of Biological, Social, and Psychological Determinants of Substance Use Disorder and Co-Occurring Mental Health Outcomes. Psychoactives 2024, 3, 194–214. [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.M. What’s in a Name? Mental Disorders, Mental Health Conditions and Psychosocial Disability. World psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. 2024, 23, 209–210. [CrossRef]

- Ploke, V.; Batinic, B.; Stieger, S. Evaluating Flourishing: A Comparative Analysis of Four Measures Using Item Pool Visualization. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1458946. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and M.H. and M.D.B. on H.C.S.C. on I.D.M.C.L. to I. with T. Selected Health Conditions and Likelihood of Improvement with Treatment; National Academies Press, 2020;

- Moukham, H.; Lambiase, A.; Barone, G.D.; Tripodi, F.; Coccetti, P. Exploiting Natural Niches with Neuroprotective Properties: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Muscaritoli, M. The Impact of Nutrients on Mental Health and Well-Being: Insights From the Literature. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Jain, A.; Chaudhary, J.; Gautam, M.; Gaur, M.; Grover, S. Concept of Mental Health and Mental Well-Being, It’s Determinants and Coping Strategies. Indian J. Psychiatry 2024, 66, S231. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.Y.; Mei, J.X.; Yu, G.; Lei, L.; Zhang, W.H.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.L.; Kołat, D.; Yang, K.; Hu, J.K. Role of the Gut Microbiota in Anticancer Therapy: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Colella, M.; Charitos, I.A.; Ballini, A.; Cafiero, C.; Topi, S.; Palmirotta, R.; Santacroce, L. Microbiota Revolution: How Gut Microbes Regulate Our Lives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 4368. [CrossRef]

- Młynarska, E.; Jakubowska, P.; Frąk, W.; Gajewska, A.; Sornowska, J.; Skwira, S.; Wasiak, J.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Associations of Microbiota and Nutrition with Cognitive Impairment in Diseases. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, T.; Ubaldi, F.; Volpini, V.; Valeriani, F.; Romano Spica, V. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Different Types of Physical Activity and Their Intensity: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M.; Costabile, G.; Testa, R.; D’Abbronzo, G.; Nettore, I.C.; Macchia, P.E.; Giacco, R. Ultra-Processed Foods and Human Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Santillo, A.; Albenzio, M.; Derossi, A.; Caporizzi, R.; Francavilla, M.; Racca, D.; Flagella, Z.; et al. Ultra-Processed Food and Gut Microbiota: Do Additives Affect Eubiosis? A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Ratan, Y.; Rajput, A.; Pareek, A.; Pareek, A.; Jain, V.; Sonia, S.; Farooqui, Z.; Kaur, R.; Singh, G. Advancements in Genetic and Biochemical Insights: Unraveling the Etiopathogenesis of Neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s Disease. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Junyi, L.; Yueyang, W.; Bin, L.; Xiaohong, D.; Wenhui, C.; Ning, Z.; Hong, Z. Gut Microbiota Mediates Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Unraveling Key Factors and Mechanistic Insights. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62. [CrossRef]

- Kasarello, K.; Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska, A.; Czarzasta, K. Communication of Gut Microbiota and Brain via Immune and Neuroendocrine Signaling. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.S.; Mak, W.Q.; Tan, L.K.S.; Ng, C.X.; Chan, H.H.; Yeow, S.H.; Foo, J.B.; Ong, Y.S.; How, C.W.; Khaw, K.Y. Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis and Its Therapeutic Applications in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 37. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, K. V.; Sherwin, E.; Schellekens, H.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Feeding the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Diet, Microbiome, and Neuropsychiatry. Transl. Res. 2017, 179, 223–244. [CrossRef]

- Fekete, M.; Lehoczki, A.; Major, D.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Csípő, T.; Tarantini, S.; Csizmadia, Z.; Varga, J.T. Exploring the Influence of Gut-Brain Axis Modulation on Cognitive Health: A Comprehensive Review of Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Symbiotics. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Chianese, R.; Coccurello, R.; Viggiano, A.; Scafuro, M.; Fiore, M.; Coppola, G.; Operto, F.F.; Fasano, S.; Laye, S.; Pierantoni, R.; et al. Impact of Dietary Fats on Brain Functions. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 16, 1059–1085. [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G. Nutritional Psychiatry: How Diet Affects Brain through Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Damiani, F.; Cornuti, S.; Tognini, P. The Gut-Brain Connection: Exploring the Influence of the Gut Microbiota on Neuroplasticity and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Neuropharmacology 2023, 231. [CrossRef]

- Daliry, A.; Pereira, E.N.G. da S. Role of Maternal Microbiota and Nutrition in Early-Life Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Xie, F.; Chen, B.; Shin, W.S.; Chen, W.; He, Y.; Leung, K.T.; Tse, G.M.K.; Yu, J.; To, K.F.; et al. The Nerve Cells in Gastrointestinal Cancers: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Intervention. Oncogene 2024, 43, 77–91. [CrossRef]

- Nakhal, M.M.; Yassin, L.K.; Alyaqoubi, R.; Saeed, S.; Alderei, A.; Alhammadi, A.; Alshehhi, M.; Almehairbi, A.; Al Houqani, S.; BaniYas, S.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Neurological Disorders: A Comprehensive Review. Life 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.; Dwivedi, R.; Bansal, M.; Tripathi, M.; Dada, R. Role of Gut Microbiota in Neurological Disorders and Its Therapeutic Significance. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Mihailovich, M.; Soković Bajić, S.; Dinić, M.; Đokić, J.; Živković, M.; Radojević, D.; Golić, N. Cutting-Edge IPSC-Based Approaches in Studying Host-Microbe Interactions in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Anand, N.; Gorantla, V.R.; Chidambaram, S.B. The Role of Gut Dysbiosis in the Pathophysiology of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kuźniar, J.; Kozubek, P.; Czaja, M.; Leszek, J. Correlation between Alzheimer’s Disease and Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, H.; Liu, Z.; Geng, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, W. Gut Microbes in Central Nervous System Development and Related Disorders. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Barmaki, H.; Nourazarian, A.; Khaki-Khatibi, F. Proteostasis and Neurodegeneration: A Closer Look at Autophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1281338. [CrossRef]

- Amartumur, S.; Nguyen, H.; Huynh, T.; Kim, T.S.; Woo, R.S.; Oh, E.; Kim, K.K.; Lee, L.P.; Heo, C. Neuropathogenesis-on-Chips for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Pashaei, K.H.A.; Irankhah, K.; Namkhah, Z.; Sobhani, S.R. Edible Mushrooms as an Alternative to Animal Proteins for Having a More Sustainable Diet: A Review. J. Heal. Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huh, J.R.; Shah, K. Microbiota and the Gut-Brain-Axis: Implications for New Therapeutic Design in the CNS. eBioMedicine 2022, 77. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, T.S.; Senapati, S.G.; Gadam, S.; Mannam, H.P.S.S.; Voruganti, H.V.; Abbasi, Z.; Abhinav, T.; Challa, A.B.; Pallipamu, N.; Bheemisetty, N.; et al. The Impact of Microbiota on the Gut-Brain Axis: Examining the Complex Interplay and Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.; Zhou, Q.G.; Xu, C.; Taleb, A.; Meng, F.; Ahmed, B.; Zhang, Y.; Fukunaga, K.; Han, F. Gut-Brain Axis: A Matter of Concern in Neuropsychiatric Disorders…! Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 104. [CrossRef]

- Settanni, C.R.; Ianiro, G.; Bibbò, S.; Cammarota, G.; Gasbarrini, A. Gut Microbiota Alteration and Modulation in Psychiatric Disorders: Current Evidence on Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.K.; Ramadan, H.K.A.; Elbeh, K.; Haridy, N.A. Bridging the Gap: Associations between Gut Microbiota and Psychiatric Disorders. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2024 311 2024, 31, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, Q.; Mou, C.K.; Lei, L.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, W.; et al. Current Landscape of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Treating Depression. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Chang, K.T.; Chang, F. Just a Gut Feeling: Faecal Microbiota Transplant for Treatment of Depression – A Mini-Review. J. Psychopharmacol. 2024, 38, 353–361. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, T.; Zhu, C.; Qiu, Y.; Yu, E. Research Progress on Mechanisms of Modulating Gut Microbiota to Improve Symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder. Discov. Med. 2024, 36, 1354. [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, P.B.; Sorond, F.A. What Is Brain Health? Cereb. Circ. - Cogn. Behav. 2024, 6. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pinilla, F. Brain Foods: The Effects of Nutrients on Brain Function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 568–578. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Long, J.; Feng, Z.; Su, J.; Gao, F.; Liu, J. Mitochondria as a Sensor, a Central Hub and a Biological Clock in Psychological Stress-Accelerated Aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 93. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Dash, R.; Nishan, A. Al; Habiba, S.U.; Moon, I.S. Brain Modulation by the Gut Microbiota: From Disease to Therapy. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 53, 153–173. [CrossRef]

- Rusch, J.A.; Layden, B.T.; Dugas, L.R. Signalling Cognition: The Gut Microbiota and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Prinz, M.; Masuda, T.; Wheeler, M.A.; Quintana, F.J. Microglia and Central Nervous System-Associated Macrophages Mdash from Origin to Disease Modulation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 39, 251–277. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Eo, J.C.; Lee, C.; Yu, J.W. Distinct Features of Brain-Resident Macrophages: Microglia and Non-Parenchymal Brain Macrophages. Mol. Cells 2021, 44, 281–291. [CrossRef]

- Thameem Dheen, S.; Kaur, C.; Ling, E.-A. Microglial Activation and Its Implications in the Brain Diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 1189–1197. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Mechanism and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Jiang, H. Border-Associated Macrophages in the Central Nervous System. J. Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 67. [CrossRef]

- Osetrova, M.; Tkachev, A.; Mair, W.; Guijarro Larraz, P.; Efimova, O.; Kurochkin, I.; Stekolshchikova, E.; Anikanov, N.; Foo, J.C.; Cazenave-Gassiot, A.; et al. Lipidome Atlas of the Adult Human Brain. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Smolińska, K.; Szopa, A.; Sobczyński, J.; Serefko, A.; Dobrowolski, P. Nutritional Quality Implications: Exploring the Impact of a Fatty Acid-Rich Diet on Central Nervous System Development. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- McNamara, R.K.; Asch, R.H.; Lindquist, D.M.; Krikorian, R. Role of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Human Brain Structure and Function across the Lifespan: An Update on Neuroimaging Findings. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2018, 136, 23–34. [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Brodrick, L. Omega-3 Supplementation Reduces Aggressive Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2024, 78. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, P.H.G. de; Duarte, A.O.; Silva, M.C. da Influência Da Dieta Na Saúde Mental e Desempenho Cognitivo – Uma Revisão Da Literatura. Res. Soc. Dev. 2024, 13, e11013646103. [CrossRef]

- Swathi, M.; Manjusha, S.; Vadakkiniath, I.J.; Gururaj, A. Prevalence and Correlates of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression in Patients with Chronic Diseases: A Cross-Sectional Study. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 30. [CrossRef]

- Padamsey, Z.; Rochefort, N.L. Paying the Brain’s Energy Bill. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2023, 78. [CrossRef]

- Komar-Fletcher, M.; Wojas, J.; Rutkowska, M.; Raczyńska, G.; Nowacka, A.; Jurek, J.M. Negative Environmental Influences on the Developing Brain Mediated by Epigenetic Modifications. Explor. Neurosci. 2023, 2, 193–211. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, Y.; Hamazaki, K. [Considering Mental Health from the Viewpoint of Diet: The Role and Possibilities of Nutritional Psychiatry]. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 2016.

- Warren, M.; O’Connor, C.; Lee, J.E.; Burton, J.; Walton, D.; Keathley, J.; Wammes, M.; Osuch, E. Predispose, Precipitate, Perpetuate, and Protect: How Diet and the Gut Influence Mental Health in Emerging Adulthood. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1339269. [CrossRef]

- Morelli, A.M.; Scholkmann, F. Should the Standard Model of Cellular Energy Metabolism Be Reconsidered? Possible Coupling between the Pentose Phosphate Pathway, Glycolysis and Extra-Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation. Biochimie 2024, 221, 99–109. [CrossRef]

- Bruce, K.D.; Zsombok, A.; Eckel, R.H. Lipid Processing in the Brain: A Key Regulator of Systemic Metabolism. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; An, Y.A.; Scherer, P.E. Mitochondrial Regulation and White Adipose Tissue Homeostasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2022, 32, 351–364. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Uris, B.; Ramos, M.A.; Busquets, A.; Angulo-Barroso, R. Can Exercise Shape Your Brain? A Review of Aerobic Exercise Effects on Cognitive Function and Neuro-Physiological Underpinning Mechanisms. AIMS Neurosci. 2022, 9, 150–174. [CrossRef]

- Kanougiya, S.; Daruwalla, N.; Osrin, D. Mental Health on Two Continua: Mental Wellbeing and Common Mental Disorders in a Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study with Women in Urban Informal Settlements in India. BMC Womens. Health 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Leslie, K.G.; Berry, S.S.; Miller, G.J.; Mahon, C.S. Sugar-Coated: Can Multivalent Glycoconjugates Improve upon Nature’s Design? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146. [CrossRef]

- Kitchener, E.J.A.; Dundee, J.M.; Brown, G.C. Activated Microglia Release β-Galactosidase That Promotes Inflammatory Neurodegeneration. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Itoh, K.; Tsukimoto, J. Lysosomal Sialidase NEU1, Its Intracellular Properties, Deficiency, and Use as a Therapeutic Agent. Glycoconj. J. 2023, 40, 611–619. [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, D.H.; Brown, G.C. Neu1 Is Released From Activated Microglia, Stimulating Microglial Phagocytosis and Sensitizing Neurons to Glutamate. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16. [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Shui, H.; Chen, R.; Dong, Y.; Xiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Wong, N.K. Neuraminidase-1 (NEU1): Biological Roles and Therapeutic Relevance in Human Disease. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 8031–8052. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Song, Y.; Lv, C.; Li, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q. Mushroom-Derived Bioactive Components with Definite Structures in Alleviating the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, D.W.; Hwang, B.S.; Woo, E.E.; Lee, Y.J.; Jeong, K.W.; Lee, I.K.; Yun, B.S. Neuraminidase Inhibitors from the Fruiting Body of Phellinus Igniarius. Mycobiology 2016, 44, 117. [CrossRef]

- van Zonneveld, S.M.; van den Oever, E.J.; Haarman, B.C.M.; Grandjean, E.L.; Nuninga, J.O.; van de Rest, O.; Sommer, I.E.C. An Anti-Inflammatory Diet and Its Potential Benefit for Individuals with Mental Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases—A Narrative Review. Nutr. 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Białek-Dratwa, A.; Sobczyk, K.; Grot, M.; Kowalski, O.; Staśkiewicz, W. Nutrition and Mental Health: A Review of Current Knowledge about the Impact of Diet on Mental Health. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

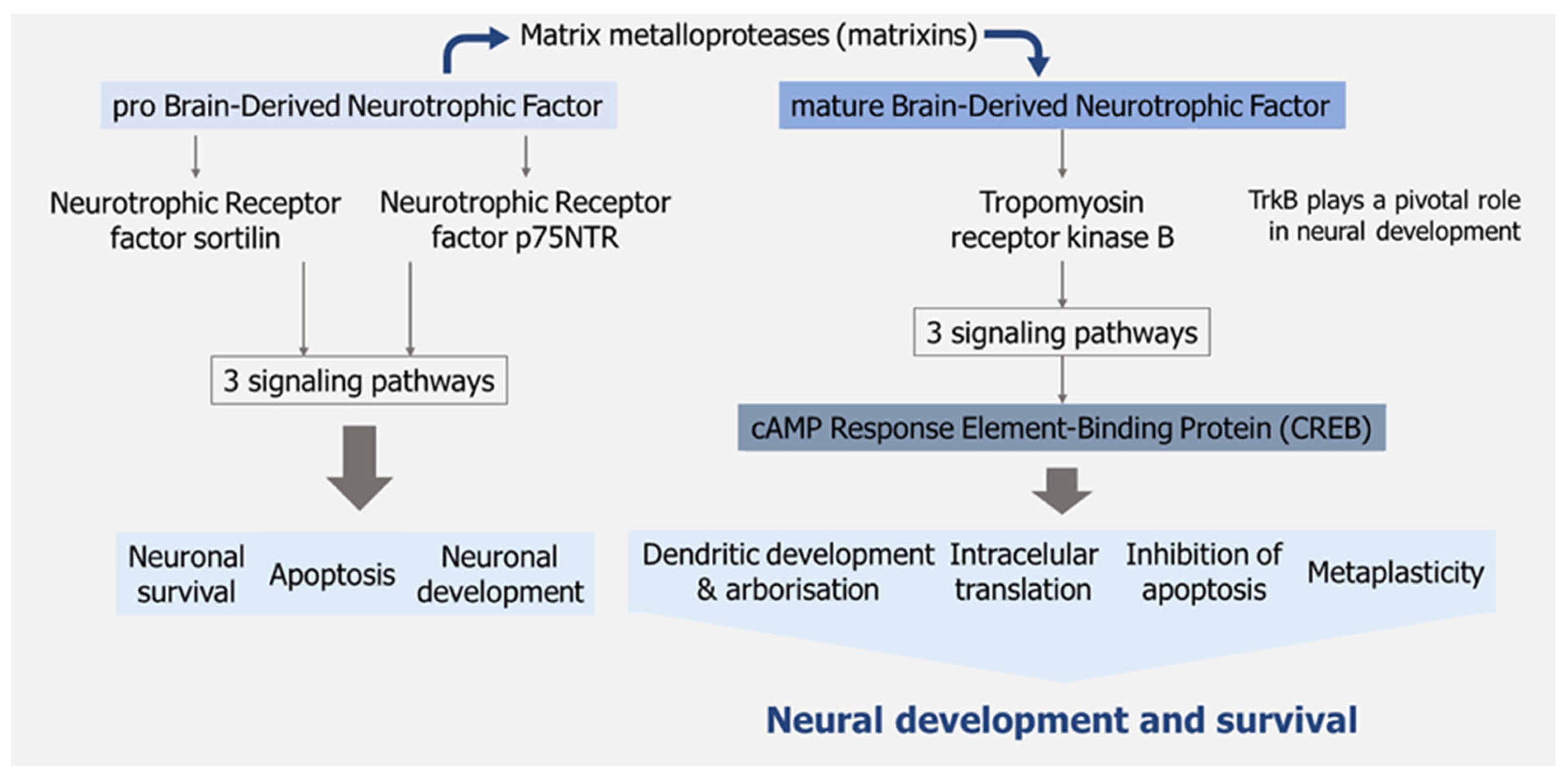

- Palasz, E.; Wysocka, A.; Gasiorowska, A.; Chalimoniuk, M.; Niewiadomski, W.; Niewiadomska, G. BDNF as a Promising Therapeutic Agent in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Schirò, G.; Iacono, S.; Ragonese, P.; Aridon, P.; Salemi, G.; Balistreri, C.R. A Brief Overview on BDNF-Trk Pathway in the Nervous System: A Potential Biomarker or Possible Target in Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis? Front. Neurol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Vacaras, V.; Paraschiv, A.C.; Iluț, S.; Vacaras, C.; Nistor, C.; Marin, G.E.; Schiopu, A.M.; Nistor, D.T.; Vesa, Ștefan C.; Mureșanu, D.F. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Multiple Sclerosis Disability: A Prospective Study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.W.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, C.; Kim, Y.T. Natural Products and Their Neuroprotective Effects in Degenerative Brain Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- von Bohlen und Halbach, O.; Klausch, M. The Neurotrophin System in the Postnatal Brain-An Introduction. Biology (Basel). 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pisani, A.; Paciello, F.; Del Vecchio, V.; Malesci, R.; De Corso, E.; Cantone, E.; Fetoni, A.R. The Role of BDNF as a Biomarker in Cognitive and Sensory Neurodegeneration. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Numakawa, T.; Kajihara, R. An Interaction between Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Stress-Related Glucocorticoids in the Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Alway, E.; Reicher, N.; Bohórquez, D. V. Deciphering Visceral Instincts: A Scientific Quest to Unravel Food Choices from Molecules to Mind. Genes Dev. 2024, 38, 798–801. [CrossRef]

- Sarris, J.; Ravindran, A.; Yatham, L.N.; Marx, W.; Rucklidge, J.J.; McIntyre, R.S.; Akhondzadeh, S.; Benedetti, F.; Caneo, C.; Cramer, H.; et al. Clinician Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders with Nutraceuticals and Phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 23, 424–455. [CrossRef]

- Mulè, S.; Ferrari, S.; Rosso, G.; Galla, R.; Battaglia, S.; Curti, V.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. The Combined Effect of Green Tea, Saffron, Resveratrol, and Citicoline against Neurodegeneration Induced by Oxidative Stress in an In Vitro Model of Cognitive Decline. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2024, 2024, 7465045. [CrossRef]

- Horovitz, O. Nutritional Psychology: Review the Interplay Between Nutrition and Mental Health. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, 562–576. [CrossRef]

- Hiltensperger, R.; Neher, J.; Böhm, L.; Mueller-Stierlin, A.S. Mapping the Scientific Research on Nutrition and Mental Health: A Bibliometric Analysis. Nutr. 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Gangwisch, J.E.; Gangwisch, J.E.; Borisini, A.; Wootton, R.E.; Wootton, R.E.; Wootton, R.E.; Mayer, E.A.; Mayer, E.A. Food and Mood: How Do Diet and Nutrition Affect Mental Wellbeing? BMJ 2020, 369. [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Target Collaborators Global, Regional, and National Progress towards the 2030 Global Nutrition Targets and Forecasts to 2050: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet (London, England) 2024. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, R.; Selvamani, T.Y.; Zahra, A.; Malla, J.; Dhanoa, R.K.; Venugopal, S.; Shoukrie, S.I.; Hamouda, R.K.; Hamid, P. Association Between Dietary Habits and Depression: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022. [CrossRef]

- Adan, R.A.H.; van der Beek, E.M.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Cryan, J.F.; Hebebrand, J.; Higgs, S.; Schellekens, H.; Dickson, S.L. Nutritional Psychiatry: Towards Improving Mental Health by What You Eat. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 1321–1332. [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, M.; Łuszczki, E.; Michońska, I.; Dereń, K. The Mediterranean Diet and the Western Diet in Adolescent Depression-Current Reports. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Chopra, C.; Mandalika, S.; Kinger, N. Does Diet Play a Role in the Prevention and Management of Depression among Adolescents? A Narrative Review. Nutr. Health 2021, 27, 243–263. [CrossRef]

- Baklizi, G.S.; Bruce, B.C.; Santos, A.C. de C.P. Neuronutrição Na Depressão e Transtorno de Ansiedade. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e52101724454. [CrossRef]

- Caroni, D.; Rodrigues, J.S.; Santos, A.L. Influence of Diet on the Prevention and Treatment of Alzheimer: An Integrative Review. Res. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, e14812541677–e14812541677. [CrossRef]

- Offor, S.J.; Orish, C.N.; Frazzoli, C.; Orisakwe, O.E. Augmenting Clinical Interventions in Psychiatric Disorders: Systematic Review and Update on Nutrition. Front. psychiatry 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rebouças, F. da C.; Barbosa, L.L.; Nascimento, L.F. do; Ferreira, J.C. de S.; Freitas, F.M.N. de O. A Influência Da Nutrição No Tratamento e Prevenção Dos Transtornos Mentais: Ansiedade e Depressão. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e57111537078. [CrossRef]

- Reily, N.M.; Tang, S.; Negrone, A.; Gan, D.Z.Q.; Sheanoda, V.; Christensen, H. Omega-3 Supplements in the Prevention and Treatment of Youth Depression and Anxiety Symptoms: A Scoping Review. PLoS One 2023, 18. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Mo, L.; Luo, J.; Shen, Q.; Quan, W. Association between Western Dietary Patterns, Typical Food Groups, and Behavioral Health Disorders: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Boushey, C.; Ard, J.; Bazzano, L.; Heymsfield, S.; Mayer-Davis, E.; Sabaté, J.; Snetselaar, L.; Horn, L. Van; Schneeman, B.; English, L.K.; et al. Dietary Patterns and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review; USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review: Alexandria, 2020;

- English, L.K.; Ard, J.D.; Bailey, R.L.; Bates, M.; Bazzano, L.A.; Boushey, C.J.; Brown, C.; Butera, G.; Callahan, E.H.; de Jesus, J.; et al. Evaluation of Dietary Patterns and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. open 2021, 4, e2122277. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, P.; Chattu, V.K.; Aeri, B.T. Nutritional Aspects of Depression in Adolescents - A Systematic Review. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Dean, E.; Xu, J.; Jones, A.Y.M.; Vongsirinavarat, M.; Lomi, C.; Kumar, P.; Ngeh, E.; Storz, M.A. An Unbiased, Sustainable, Evidence-Informed Universal Food Guide: A Timely Template for National Food Guides. Nutr. J. 2024, 23, 126. [CrossRef]

- Suárez-López, L.M.; Bru-Luna, L.M.; Martí-Vilar, M. Influence of Nutrition on Mental Health: Scoping Review. Healthc. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, M.; Łuszczki, E.; Dereń, K. Dietary Nutrient Deficiencies and Risk of Depression (Review Article 2018-2023). Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Wiss, D.A.; LaFata, E.M. Ultra-Processed Foods and Mental Health: Where Do Eating Disorders Fit into the Puzzle? Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G.; Mazur, A.; Trousselard, M.; Bienkowski, P.; Yaltsewa, N.; Amessou, M.; Noah, L.; Pouteau, E. Magnesium Status and Stress: The Vicious Circle Concept Revisited. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Bell, V.; Silva, C.R.P.G.; Guina, J.; Fernandes, T.H. Mushrooms as Future Generation Healthy Foods. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Pethő, Á.G.; Fülöp, T.; Orosz, P.; Tapolyai, M. Magnesium Is a Vital Ion in the Body-It Is Time to Consider Its Supplementation on a Routine Basis. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 521–535. [CrossRef]

- Tounsi, L.; Ben Hlima, H.; Hentati, F.; Hentati, O.; Derbel, H.; Michaud, P.; Abdelkafi, S. Microalgae: A Promising Source of Bioactive Phycobiliproteins. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21. [CrossRef]

- Merlo, G.; Bachtel, G.; Sugden, S.G. Gut Microbiota, Nutrition, and Mental Health. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Scheiber, A.; Mank, V. Anti-Inflammatory Diets. StatPearls 2023.

- Pourmontaseri, H.; Khanmohammadi, S. Demographic Risk Factors of Pro-Inflammatory Diet: A Narrative Review. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.L.; Gong, Y.; Qi, Y.J.; Shao, Z.M.; Jiang, Y.Z. Effects of Dietary Intervention on Human Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Ferolito, B.; do Valle, I.F.; Gerlovin, H.; Costa, L.; Casas, J.P.; Gaziano, J.M.; Gagnon, D.R.; Begoli, E.; Barabási, A.L.; Cho, K. Visualizing Novel Connections and Genetic Similarities across Diseases Using a Network-Medicine Based Approach. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.S.; Bellou, E.; Verstappen, S.M.M.; Cook, M.J.; Sergeant, J.C.; Warren, R.B.; Barton, A.; Bowes, J. Association between Psoriatic Disease and Lifestyle Factors and Comorbidities: Cross-Sectional Analysis and Mendelian Randomization. Rheumatol. (United Kingdom) 2023, 62, 1272–1285. [CrossRef]

- Galland, L. Diet and Inflammation. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2010, 25, 634–640. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Rashid, R.; Saroya, S.; Deverapalli, M.; Brim, H.; Ashktorab, H. Saffron as a Promising Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, K.; Aggarwal, B.; Singh, R.; Buttar, H.; Wilson, D.; De Meester, F. Food Antioxidants and Their Anti-Inflammatory Properties: A Potential Role in Cardiovascular Diseases and Cancer Prevention. Diseases 2016, 4, 28. [CrossRef]

- Stromsnes, K.; Correas, A.G.; Lehmann, J.; Gambini, J.; Olaso-gonzalez, G. Anti-inflammatory Properties of Diet: Role in Healthy Aging. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Bernier, V.; Alsaleh, G.; Point, C.; Wacquier, B.; Lanquart, J.-P.; Loas, G.; Hein, M. Low-Grade Inflammation Associated with Major Depression Subtypes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 850. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Negrete, E.V.; Morales-González, Á.; Madrigal-Santillán, E.O.; Sánchez-Reyes, K.; Álvarez-González, I.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E.; Valadez-Vega, C.; Chamorro-Cevallos, G.; Garcia-Melo, L.F.; Morales-González, J.A. Phytochemicals and Their Usefulness in the Maintenance of Health. Plants 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Key, M.N.; Szabo-Reed, A.N. Impact of Diet and Exercise Interventions on Cognition and Brain Health in Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Roszczenko, P.; Szewczyk-Roszczenko, O.K.; Gornowicz, A.; Iwańska, I.A.; Bielawski, K.; Wujec, M.; Bielawska, A. The Anticancer Potential of Edible Mushrooms: A Review of Selected Species from Roztocze, Poland. Nutr. 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Rathor, P.; Ch, R. The Impacts of Dietary Intervention on Brain Metabolism and Neurological Disorders: A Narrative Review. Dietetics 2024, 3, 289–307. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Khan, M.K.I.; Hasan, A.; Fordos, S.; Naeem, M.Z.; Usman, A. Investigating the Relationship between Food Quality and Mental Health. 2023, 104. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, J.B. Vitamin and Mineral Basics: The ABCs of Healthy Foods and Beverages, Including Phytonutrients and Functional Foods. Culin. Nutr. 2013, 279–331. [CrossRef]

- ‘Aqilah, N.M.N.; Rovina, K.; Felicia, W.X.L.; Vonnie, J.M. A Review on the Potential Bioactive Components in Fruits and Vegetable Wastes as Value-Added Products in the Food Industry. Molecules 2023, 28. [CrossRef]

- Łysakowska, P.; Sobota, A.; Wirkijowska, A. Medicinal Mushrooms: Their Bioactive Components, Nutritional Value and Application in Functional Food Production—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28. [CrossRef]

- Al Qutaibi, M.; Kagne, S.R. Exploring the Phytochemical Compositions, Antioxidant Activity, and Nutritional Potentials of Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms. Int. J. Microbiol. 2024, 2024, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.; Mylarapu, A.; Krishna, K.V.; Kumar, D.S. An Insight into the Nutritional and Medicinal Value of Edible Mushrooms: A Natural Treasury for Human Health. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 381, 86–99. [CrossRef]

- Yimam, M.A.; Andreini, M.; Carnevale, S.; Muscaritoli, M. The Role of Algae, Fungi, and Insect-Derived Proteins and Bioactive Peptides in Preventive and Clinical Nutrition. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Bandelow, B.; Michaelis, S. Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders in the 21st Century. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 17, 327–335. [CrossRef]

- Bogadi, M.; Kaštelan, S. A Potential Effect of Psilocybin on Anxiety in Neurotic Personality Structures in Adolescents. Croat. Med. J. 2021, 62, 528–530. [CrossRef]

- Fogarasi, M.; Nemeș, S.A.; Fărcaș, A.; Socaciu, C.; Semeniuc, C.A.; Socaciu, M.I.; Socaci, S. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites in Mushrooms: A Focus on Polyphenols, Their Health Benefits and Applications. Food Biosci. 2024, 62. [CrossRef]

- Paterska, M.; Czerny, B.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Macrofungal Extracts as a Source of Bioactive Compounds for Cosmetical Anti-Aging Therapy: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Adamu, A.; Li, S.; Gao, F.; Xue, G. The Role of Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Understanding and Future Therapeutic Targets. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1347987. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A.; Moglad, E.; Afzal, M.; Thapa, R.; Almalki, W.H.; Kazmi, I.; Alzarea, S.I.; Ali, H.; Pant, K.; Singh, T.G.; et al. Therapeutic Approaches Targeting Aging and Cellular Senescence in Huntington’s Disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e70053. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Ravindran, M.; Banadka, A.; Vandana, C.D.; Priya, K.; Nagella, P.; Kukkemane, K. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Insights and New Prospects in Disease Pathophysiology, Biomarkers and Therapies. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Licastro, F.; Porcellini, E. Activation of Endogenous Retrovirus, Brain Infections and Environmental Insults in Neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, A.S.; Halo, J. V. Transcription of Endogenous Retroviruses: Broad and Precise Mechanisms of Control. Viruses 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Qin, Z. Roles of Human Endogenous Retrovirus-K-Encoded Np9 in Human Diseases: A Small Protein with Big Functions. Viruses 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Kozubek, P.; Kuźniar, J.; Czaja, M.; Sitka, H.; Kochman, U.; Leszek, J. Human Endogenous Retroviruses and Their Putative Role in Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease, Inflammation, and Senescence. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Adler, G.L.; Le, K.; Fu, Y.H.; Kim, W.S. Human Endogenous Retroviruses in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Genes (Basel). 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Barcan, A.S.; Barcan, R.A.; Vamanu, E. Therapeutic Potential of Fungal Polysaccharides in Gut Microbiota Regulation: Implications for Diabetes, Neurodegeneration, and Oncology. J. Fungi 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Pang, J.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, X.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Unveiling the Neuroprotective Potential of Dietary Polysaccharides: A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Behrad, S.; Pourranjbar, S.; Pourranjbar, M.; Abbasi-Maleki, S.; Mehr, S.R.; Salmani, R.H.G.; Moradikor, N. Grifola Frondosa Polysaccharides Alleviate Alzheimer’s Disease in Rats. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2024, 14, 500–506. [CrossRef]

- Scuto, M.; Rampulla, F.; Reali, G.M.; Spanò, S.M.; Trovato Salinaro, A.; Calabrese, V. Hormetic Nutrition and Redox Regulation in Gut-Brain Axis Disorders. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Paola, R. Di; Siracusa, R.; Fusco, R.; Ontario, M.; Cammilleri, G.; Pantano, L.; Scuto, M.; Tomasello, M.; Spanò, S.; Salinaro, A.T.; et al. Redox Modulation of Meniere Disease by Coriolus Versicolor Treatment, a Nutritional Mushroom Approach with Neuroprotective Potential. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 22, 2079. [CrossRef]

- Sharika, R.; Mongkolpobsin, K.; Rangsinth, P.; Prasanth, M.I.; Nilkhet, S.; Pradniwat, P.; Tencomnao, T.; Chuchawankul, S. Experimental Models in Unraveling the Biological Mechanisms of Mushroom-Derived Bioactives against Aging- and Lifestyle-Related Diseases: A Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2682. [CrossRef]

- Roodveldt, C.; Bernardino, L.; Oztop-Cakmak, O.; Dragic, M.; Fladmark, K.E.; Ertan, S.; Busra, A.; Pita, C.; Ciglar, L.; Garraux, G.; et al. The Immune System in Parkinson’s Disease: What We Know so Far. Brain 2024, 147. [CrossRef]

- Trovato Salinaro, A.; Pennisi, M.; Di Paola, R.; Scuto, M.; Crupi, R.; Cambria, M.T.; Ontario, M.L.; Tomasello, M.; Uva, M.; Maiolino, L.; et al. Neuroinflammation and Neurohormesis in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer-Linked Pathologies: Modulation by Nutritional Mushrooms. Immun. Ageing 2018, 15. [CrossRef]

- Cordaro, M.; Modafferi, S.; D’Amico, R.; Fusco, R.; Genovese, T.; Peritore, A.F.; Gugliandolo, E.; Crupi, R.; Interdonato, L.; Di Paola, D.; et al. Natural Compounds Such as Hericium Erinaceus and Coriolus Versicolor Modulate Neuroinflammation, Oxidative Stress and Lipoxin A4 Expression in Rotenone-Induced Parkinson’s Disease in Mice. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2505. [CrossRef]

- Naim, M.J. A Review on Mushrooms as a Versatile Therapeutic Agent with Emphasis on Its Bioactive Constituents for Anticancer and Antioxidant Potential. Explor. Med. 2024, 5, 312–330. [CrossRef]

- Podkowa, A.; Kryczyk-Poprawa, A.; Opoka, W.; Muszyńska, B. Culinary–Medicinal Mushrooms: A Review of Organic Compounds and Bioelements with Antioxidant Activity. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 513–533. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Shahzadi, S.; Ransom, R.F.; Kloczkowski, A. Nature’s Own Pharmacy: Mushroom-Based Chemical Scaffolds and Their Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Liuzzi, G.M.; Petraglia, T.; Latronico, T.; Crescenzi, A.; Rossano, R. Antioxidant Compounds from Edible Mushrooms as Potential Candidates for Treating Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Recent Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms, Clinical Trials and New Drug Development Strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E.; Bairwa, R.; Lal, P.; Pattanayak, S.; Chakrapani, K.; Poorvasandhya, R.; Kumar, A.; Altaf, M.A.; Tiwari, R.K.; Lal, M.K.; et al. Edible Mushrooms Trending in Food: Nutrigenomics, Bibliometric, from Bench to Valuable Applications. Heliyon 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Gajendra, K.; Pratap, G.K.; Poornima, D. V.; Shantaram, M.; Ranjita, G. Natural Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors: A Multi-Targeted Therapeutic Potential in Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Reports 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Fijałkowska, A.; Jędrejko, K.; Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Ziaja, M.; Kała, K.; Muszyńska, B. Edible Mushrooms as a Potential Component of Dietary Interventions for Major Depressive Disorder. Foods 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Chenghom, O.; Suksringar, J.; Morakot, N. Mineral Composition and Germanium Contents in Some Phellinus Mushrooms in the Northeast of Thailand. Curr. Res. Chem. 2010, 2, 24–34. [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, J.; Bell, V.; Chaquisse, E.; Garrine, C.; Fernandes, T. The Synbiotic Role of Mushrooms: Is Germanium a Bioactive Prebiotic Player? A Review Article. Am. J. Food Nutr. 2019, 7, 26–35. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Sun, J.; Kong, D.; Lei, Y.; Gong, F.; Zhang, T.; Shen, Z.; Wang, K.; Luo, H.; Xu, Y. The Role of Germanium in Diseases: Exploring Its Important Biological Effects. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21. [CrossRef]

- Bravo, L. Polyphenols: Chemistry, Dietary Sources, Metabolism, and Nutritional Significance. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 56, 317–333. [CrossRef]

- Jawhara, S. How Do Polyphenol-Rich Foods Prevent Oxidative Stress and Maintain Gut Health? Microorganisms 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Shih, R.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Yang, C.M. NF-KappaB Signaling Pathways in Neurological Inflammation: A Mini Review. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2015, 8. [CrossRef]

- Nasiry, D.; Khalatbary, A.R. Natural Polyphenols for the Management of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review of Efficacy and Molecular Mechanisms. Nutr. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 241–251. [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Shao, C.; Geng, P.; Wang, S.; Xiao, J. Polyphenols Targeting NF-ΚB Pathway in Neurological Disorders: What We Know So Far? Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 1332–1355. [CrossRef]

- Wachtel-Galor, S.; Yuen, J.; Buswell, J.A.; Benzie, I.F.F. Ganoderma Lucidum (Lingzhi or Reishi). In Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton; Florida, 2011; pp. 175–199 ISBN 9781439807163.

- Uffelman, C.N.; Harold, R.; Hodson, E.S.; Chan, N.I.; Foti, D.; Campbell, W.W. Effects of Consuming White Button and Oyster Mushrooms within a Healthy Mediterranean-Style Dietary Pattern on Changes in Subjective Indexes of Brain Health or Cognitive Function in Healthy Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Foods 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, E.; Pita, I.R.; Mota, S.I.; Valero, J.; Ferreira, N.R.; Fernandes, T.; Calabrese, V.; Fontes-Ribeiro, C.A.; Pereira, F.C.; Rego, A.C. Coriolus Versicolor Biomass Increases Dendritic Arborization of Newly-Generated Neurons in Mouse Hippocampal Dentate Gyrus. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 32929–32942. [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Agramonte, M. de los A.; García, E.N.; Guerra, J.F.; Hurtado, Y.V.; Antonucci, N.; Semprún-Hernández, N.; Schultz, S.; Siniscalco, D. Immune Dysregulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder: What Do We Know about It? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Modafferi, S.; Lupo, G.; Tomasello, M.; Rampulla, F.; Ontario, M.; Scuto, M.; Salinaro, A.T.; Arcidiacono, A.; Anfuso, C.D.; Legmouz, M.; et al. Antioxidants, Hormetic Nutrition, and Autism. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 22, 1156–1168. [CrossRef]

- Mihailovich, M.; Tolinački, M.; Soković Bajić, S.; Lestarevic, S.; Pejovic-Milovancevic, M.; Golić, N. The Microbiome-Genetics Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Probiotic Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Lau, B.F.; Abdullah, N. Sclerotium-Forming Mushrooms as an Emerging Source of Medicinals: Current Perspectives. In Mushroom Biotechnology: Developments and Applications; Petre, M., Ed.; Academic Press, 2016; pp. 111–136 ISBN 9780128027943.

- Li, I.C.; Chang, H.H.; Lin, C.H.; Chen, W.P.; Lu, T.H.; Lee, L.Y.; Chen, Y.W.; Chen, Y.P.; Chen, C.C.; Lin, D.P.C. Prevention of Early Alzheimer’s Disease by Erinacine A-Enriched Hericium Erinaceus Mycelia Pilot Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dong, K.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Shuai, H.; Yu, X. Raw Inonotus Obliquus Polysaccharide Counteracts Alzheimer’s Disease in a Transgenic Mouse Model by Activating the Ubiquitin-Proteosome System. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2023, 17, 1128–1142. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, S.; Feng, X.; Li, L.; Hao, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, Q. Mushroom Polysaccharides as Potential Candidates for Alleviating Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Mármol, R.; Chai, Y.J.; Conroy, J.N.; Khan, Z.; Hong, S.M.; Kim, S.B.; Gormal, R.S.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, J.K.; Coulson, E.J.; et al. Hericerin Derivatives Activates a Pan-Neurotrophic Pathway in Central Hippocampal Neurons Converging to ERK1/2 Signaling Enhancing Spatial Memory. J. Neurochem. 2023, 165, 791–808. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Lin, G.; Liu, W.; Zhang, F.; Linhardt, R.J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, A. Bioactive Substances in Hericium Erinaceus and Their Biological Properties: A Review. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 1825–1844. [CrossRef]

- Roda, E.; Priori, E.C.; Ratto, D.; De Luca, F.; Di Iorio, C.; Angelone, P.; Locatelli, C.A.; Desiderio, A.; Goppa, L.; Savino, E.; et al. Neuroprotective Metabolites of Hericium Erinaceus Promote Neuro-Healthy Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Amara, I.; Scuto, M.; Zappalà, A.; Ontario, M.L.; Petralia, A.; Abid-Essefi, S.; Maiolino, L.; Signorile, A.; Salinaro, A.T.; Calabrese, V. Hericium Erinaceus Prevents Dehp-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Apoptosis in PC12 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Yanshree; Yu, W.S.; Fung, M.L.; Lee, C.W.; Lim, L.W.; Wong, K.H. The Monkey Head Mushroom and Memory Enhancement in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Trovato, A.; Siracusa, R.; Di Paola, R.; Scuto, M.; Ontario, M.L.; Bua, O.; Di Mauro, P.; Toscano, M.A.; Petralia, C.C.T.; Maiolino, L.; et al. Redox Modulation of Cellular Stress Response and Lipoxin A4 Expression by Hericium Erinaceus in Rat Brain: Relevance to Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. Immun. Ageing 2016, 13. [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Inatomi, S.; Ouchi, K.; Azumi, Y.; Tuchida, T. Improving Effects of the Mushroom Yamabushitake (Hericium Erinaceus) on Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Phyther. Res. 2009, 23, 367–372. [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.; Bell, L.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Williams, C.M. A Review of the Effects of Mushrooms on Mood and Neurocognitive Health across the Lifespan. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 158. [CrossRef]

- Brandalise, F.; Roda, E.; Ratto, D.; Goppa, L.; Gargano, M.L.; Cirlincione, F.; Priori, E.C.; Venuti, M.T.; Pastorelli, E.; Savino, E.; et al. Hericium Erinaceus in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Bench to Bedside and Beyond, How Far from the Shoreline? J. Fungi 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Li, I.C.; Lee, L.Y.; Tzeng, T.T.; Chen, W.P.; Chen, Y.P.; Shiao, Y.J.; Chen, C.C. Neurohealth Properties of Hericium Erinaceus Mycelia Enriched with Erinacines. Behav. Neurol. 2018, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, M.; Nouri, F.; Sarihi, A.; Habibi, P.; Mohammadi, M. Neuroprotective Effects of Dehydroepiandrosterone and Hericium Erinaceus in Scopolamine-Induced Alzheimer’s Diseases-like Symptoms in Male Rats. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2024. [CrossRef]

- CD, G.; VA, A.; LG, K.; JD, S.; EK, O.; HS, W. Four Weeks of Hericium Erinaceus Supplementation Does Not Impact Markers of Metabolic Flexibility or Cognition. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Docherty, S.; Doughty, F.L.; Smith, E.F. The Acute and Chronic Effects of Lion’s Mane Mushroom Supplementation on Cognitive Function, Stress and Mood in Young Adults: A Double-Blind, Parallel Groups, Pilot Study. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Cheah, I.K.M.; Ng, M.M.X.; Li, J.; Chan, S.M.; Lim, S.L.; Mahendran, R.; Kua, E.H.; Halliwell, B. The Association between Mushroom Consumption and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study in Singapore. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 68, 197–203. [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.; Bell, L.; Williams, C.M. The Relationship between Mushroom Intake and Cognitive Performance: An Epidemiological Study in the European Investigation of Cancer—Norfolk Cohort (EPIC-Norfolk). Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, J.; Cock, I.; Fourie, P.; Gulati, V.; Rosenzweig, J.; Cock, I.; Fourie, P.; Gulati, V. Inhibitory Activity of Hericium Erinaceus Extracts against Some Bacterial Triggers of Multiple Sclerosis and Selected Autoimmune Diseases. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of the 4th International Electronic Conference on Nutrients (IECN 2024), 16–18 October 2024; MDPI, October 11 2024.

- Sharma, H.; Sharma, N.; An, S.S.A. Unique Bioactives from Zombie Fungus (Cordyceps) as Promising Multitargeted Neuroprotective Agents. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.A.; Elkhalifa, A.E.O.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Patel, M.; Awadelkareem, A.M.; Snoussi, M.; Ashraf, M.S.; Adnan, M.; Hadi, S. Cordycepin for Health and Wellbeing: A Potent Bioactive Metabolite of an Entomopathogenic Medicinal Fungus Cordyceps with Its Nutraceutical and Therapeutic Potential. Molecules 2020, 25, 2735. [CrossRef]

- Ekiz, E.; Oz, E.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Proestos, C.; Brennan, C.; Zeng, M.; Tomasevic, I.; Elobeid, T.; Çadırcı, K.; Bayrak, M.; et al. Exploring the Potential Medicinal Benefits of Ganoderma Lucidum: From Metabolic Disorders to Coronavirus Infections. Foods 2023, Vol. 12, Page 1512 2023, 12, 1512. [CrossRef]

- Lian, W.; Yang, X.; Duan, Q.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, C.; He, T.; Sun, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W. The Biological Activity of Ganoderma Lucidum on Neurodegenerative Diseases: The Interplay between Different Active Compounds and the Pathological Hallmarks. Molecules 2024, 29. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Lian, C.; Ke, J.; Liu, J. Triterpenes and Aromatic Meroterpenoids with Antioxidant Activity and Neuroprotective Effects from Ganoderma Lucidum. Molecules 2019, 24. [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Wang, J.; Jiang, W.; Luo, J.; Yang, R.; Zhang, L.; Han, C. Ganoderic Acid A: A Potential Natural Neuroprotective Agent for Neurological Disorders: A Review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2024, 26, 11–23. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Li, G.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Ling, J. A Novel Promising Neuroprotective Agent: Ganoderma Lucidum Polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 229, 168–180. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.F.; A. Alsayegh, A.; Ahmad, F.A.; Akhtar, M.S.; Alavudeen, S.S.; Bantun, F.; Wahab, S.; Ahmed, A.; Ali, M.; Elbendary, E.Y.; et al. Ganoderma Lucidum: Insight into Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties with Development of Secondary Metabolites. Heliyon 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, M.; Huang, R.; Wang, J.; Wu, Q.; Ding, Y. Preparation of Antioxidant Protein Hydrolysates from Pleurotus Geesteranus and Their Protective Effects on H2O2 Oxidative Damaged PC12 Cells. Molecules 2020, 25. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, M.; Liao, X.; Huang, R.; Wang, J.; Xie, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Ding, Y. Protein Hydrolysates from Pleurotus Geesteranus Obtained by Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion Exhibit Neuroprotective Effects in H2 O2 -Injured PC12 Cells. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46. [CrossRef]

- Paola, D.R.; Rosa, D.G.; J, C. V; Trovato, A.; Pennisi, M.; Crupi, R.; Di Paola, R.; Alario, A.; Modafferi, S.; Di Rosa, G.; et al. Neuroinflammation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Modulation by Coriolus Versicolor (Yun-Zhi) Nutritional Mushroom. J. Neurol. Neuromedicine 2017, 2, 19–28.

- Li, N.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Feng, G.; Shi, C.; Wu, Y. Unveiling the Therapeutic Potentials of Mushroom Bioactive Compounds in Alzheimer’s Disease. Foods 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.N.; Mishra, D.; Singh, P.; Vamanu, E.; Singh, M.P. Therapeutic Applications of Mushrooms and Their Biomolecules along with a Glimpse of in Silico Approach in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137. [CrossRef]

- Kou, R.W.; Xia, B.; Han, R.; Li, Z.Q.; Yang, J.R.; Yin, X.; Gao, Y.Q.; Gao, J.M. Neuroprotective Effects of a New Triterpenoid from Edible Mushroom on Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis through the BDNF/TrkB/ERK/CREB and Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Vitro and in Vivo. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12121–12134. [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.Y.A.; Wong, A.N.N.; Ho, C.Y.; Tse, K.W.; Chan, A.Z.; Leung, G.P.H.; Kwan, Y.W.; Yeung, M.H.Y. Potentials of Natural Antioxidants in Reducing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Chronic Kidney Disease. Antioxidants 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, J.; Bell; Calabrese, V.; Pimentel, L.; Pintado, M.; Fernandes, T. Impact of Mushroom Nutrition on Microbiota and Potential for Preventative Health. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 5, 226–233. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).