Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

17 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Determinants of Organic Farming

2.2. Public Policies vs. Organic Farming

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kułyk, P.; Dubicki, P. Uwarunkowania zachowań konsumentów na rynku żywności ekologicznej. Problems of World Agriculture/ Problemy Rolnictwa Światowego 2019, 19, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stappen, F.; Loriers, A. , Mathot, M.; Planchon, V.; Stilmant, D.; Debode, F. Organic versus conventional farming: the case of wheat production in Wallonia (Belgium). Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia 2015, 7, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissen, V.; Silva, V.; Lwanga, E. H.; Beriot, N.; Oostindie, K.; Bin, Z.; Ritsema, C.J. Cocktails of pesticide residues in conventional and organic farming systems in Europe–Legacy of the past and turning point for the future. Environmental Pollution 2021, 278, 116827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostensalo, J.; Lemola, R.; Salo, T.; Ukonmaanaho, L.; Turtola, E.; Saarinen, M. A site-specific prediction model for nitrogen leaching in conventional and organic farming. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 349, 119388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacono, M.; Persiani, A.; Testani, E.; Montemurro, F.; Ciaccia, C. Recycling agricultural wastes and by-products in organic farming: Biofertilizer production, yield performance and carbon footprint analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, T.; Pimentel, D.; Paoletti, M.G. Environmental impact of different agricultural management practices: conventional vs. organic agriculture. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2011, 30, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambotte, M.; De Cara, S.; Brocas, C.; Bellassen, V. Organic farming offers promising mitigation potential in dairy systems without compromising economic performances. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 334, 117405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squalli, J. , & Adamkiewicz, G. The spatial distribution of agricultural emissions in the United States: The role of organic farming in mitigating climate change. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2023; 137678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Menalled, F.D. Supporting beneficial insects for agricultural sustainability: The role of livestock-integrated organic and cover cropping to enhance ground beetle (Carabidae) communities. Agronomy 2000, 10, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Singh, P.P.; Singh, S.K.; Verma, H. Sustainable agriculture and benefits of organic farming to special emphasis on PGPR. Role of plant growth promoting microorganisms in sustainable agriculture and nanotechnology 2019, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotchés-Ribalta, R.; Marull, J.; Pino, J. Organic farming increases functional diversity and ecosystem service provision of spontaneous vegetation in Mediterranean vineyards. Ecological Indicators 2023, 147, 110023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockstrom, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F. S. I.; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T. M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H. J.; Nykvist, B.; de Wit, C. A.; Hughes, T.; van der Leeuw, S.; Rodhe, H.; Sörlin, S.; Snyder, P. K.; Costanza, R.; Svedin, U.; Falkenmark, M.; Karlberg, L.; Corell, R. W.; Fabry, V. J.; Hansen, J.; Walker, B.; Liverman, D.; Richardson, K.; Crutzen, P.; Foley, J. Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecology and Society 2009, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PIU. Polska Izba Ubezpieczeń. Klimat rosnących strat. Rola ubezpieczeń w ochronie klimatu i transformacji energetycznej. /A climate of mounting losses. The role of insurance in climate protection and the energy transition/. Warszawa, Poland 2023. Available online: https://piu.org.pl/raporty/klimat-rosnacych-strat/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Richardson, K. , Steffen, W., et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Science Advances 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendyk, E. Przestrzelona przyszłość. Polityka, 2024; 49. [Google Scholar]

- Buchner, B. COP 29’s climate investment imperative. Science 2024, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Climate Change Service. 2024 – first year exceed 1.5°C above pre-industrial level. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Hansen, E. J.; Karecha, P.; Sato, M.; Kelly, J. Global warming has accelerated: Are the United Nations and the public well-informed? Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 2025; 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M. Punkt krytyczny dla klimatu. Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, 2025; 25. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. (2025). The Global Risks Report 2025 (20th ed.).

- Liu, X.; Pattanaik, N.; Nelson, M.; Ibrahim, M. The choice to go organic: Evidence from small US farms. Agricultural Sciences 2019, 10, 1566–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.P.; Requena, J.C. Factors related to the adoption of organic farming in Spanish olive orchards. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2005, 3, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malá, Z.; Malý, M. The determinants of adopting organic farming practices: A case study in the Czech Republic. Agricultural Economics 2013, 59, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, L.; Schleenbecker, R.; Hamm, U. Factors influencing a conversion to organic farming in Nepalese tea farms. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics 2011, 112, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Khaledi, M.; Weseen, S.; Sawyer, E.; Ferguson, S.; Richard, G. Factors influencing partial and complete adoption of organic farming practices in Saskatchewan, Canada. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics 2011, 58, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhao, H.; Pawlak, K.; Gao, Y. The development of organic agriculture in China and the factors affecting organic farming. Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development, 2016; 1644-2016-135466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, S.; Hakala, O.; Viitaharju, L. Factors affecting the regional distribution of organic farming. Journal of Rural Studies 2022, 92, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, J.; Kuhn, T.; Pahmeyer, C.; Britz, W. Economic effects of plot sizes and farm-plot distances in organic and conventional farming systems: A farm-level analysis for Germany. Agricultural Systems 2021, 187, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.F.; Cheng, C.Y. Exploring the distribution of organic farming: Findings from certified rice in Taiwan. Ecological Economics 2023, 212, 107915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Wrzaszcz, W.; Sobierajewska, J.; Adamski, M. Development and Effects of Organic Farms in Poland, Taking into Account Their Location in Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints. Agriculture 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genius, M.; Pantzios, C.J.; Tzouvelekas, V. Information acquisition and adoption of organic farming practices. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2006, 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kafle, B. Factors affecting adoption of organic vegetable farming in Chitwan District, Nepal. World Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2011, 7, 604–606. [Google Scholar]

- Koesling, M.; Flaten, O.; Lien, G. Factors influencing the conversion to organic farming in Norway. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 2008; 7, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Xiang, P.; Mei, G.; Liu, Z. Drivers for the Adoption of Organic Farming: Evidence from an Analysis of Chinese Farmers. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartulović, A.; Kozorog, M. Taking up organic farming in (pre-) Alpine Slovenia: Contrasting motivations of dairy farmers from less-favoured agricultural areas. Anthropological Notebooks 2014, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Wollni, M.; Andersson, C. Spatial patterns of organic agriculture adoption: Evidence from Honduras. Ecological Economics 2014, 97, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Läpple, D. Adoption and abandonment of organic farming: an empirical investigation of the Irish drystock sector. Journal of Agricultural Economics 2010, 61, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Läpple, D.; van Rensburg, T. Adoption of organic farming: Are there differences between early and late adoption? Ecological Economics 2011, 70, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, Ł.; Biczkowski, M.; Rudnicki, R. Natural potential versus rationality of allocation of Common Agriculture Policy funds dedicated for supporting organic farming development–Assessment of spatial suitability: The case of Poland. Ecological Indicators 2021, 130, 108039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.N.; Saha, S.M.; Imran, S.; Hannan, A.; Seen, M.M.H.; Thamid, S.S.; Tuz-zohra, F. Farmers' agrochemicals usage and willingness to adopt organic inputs: Watermelon farming in Bangladesh. Environmental Challenges 2022, 7, 100451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, S.; Yan, J.; Gao, W.; Cui, J.; Chen, Y. From Conventional to Organic Agriculture: Influencing Factors and Reasons for Tea Farmers’ Adoption of Organic Farming in Pu’er City. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, S.; Vogel, A. Reversion from organic to conventional agriculture in Germany: An event history analysis. German Journal of Agricultural Economics 2017, 66, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriwichailamphan, T.; Sucharidtham, T. Factors affecting adoption of vegetable growing using organic system: A case study of Royal Project Foundation, Thailand. International Journal of Economics and Management Sciences 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornpratansombat, P.; Bauer, B.; Boland, H. The adoption of organic rice farming in Northeastern Thailand. Journal of Organic Systems 2011, 6, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mrinila, S.; Keshav, L.M.; Bijan, M. Factors impacting adoption of organic farming in Chitwan district of Nepal. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development 2015, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, R.W.; Verberne, E.; Negro, S.O. Accelerating the transition towards sustainable agriculture: The case of organic dairy farming in the Netherlands. Agricultural Systems 2022, 198, 103368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosius, F.H.; Kramer, M.R.; Spiegel, A.; Bokkers, E.A.; Bock, B.B.; Hofstede, G.J. Diffusion of organic farming among Dutch pig farmers: An agent-based model. Agricultural Systems 2022, 197, 103336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Oliveira, F.; Gomes da Silva, F.; Teixeira, M.; Gonçalves, M.; Eugénio, R.; Gonçalves, J. M. Assessment of factors constraining organic farming expansion in Lis Valley, Portugal. AgriEngineering 2020, 2, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, T.; Zilberman, D.; Gil, J.M. Differential uncertainties and risk attitudes between conventional and organic producers: the case of Spanish arable crop farmers. Agricultural Economics 2008, 39, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palšová, L. Organic farming versus interest of the state for its support. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 2019, 28, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman, Č.; Pažek, K.; Kljajić, M.; Bavec, M.; Turk, J.; Bavec, F.; Škraba, A. The dynamic simulation of organic farming development scenarios–A case study in Slovenia. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2013, 96, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczka, W.; Kalinowski, S. Barriers to the development of organic farming: A Polish Case Study. Agriculture 2020, 10, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, L.; Nicholas, K.A. German winegrowers’ motives and barriers to convert to organic farming. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanakittkul, P.; Aungvaravong, C. A model of farmers intentions towards organic farming: A case study on rice farming in Thailand. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerselaers, E.; De Cock, L.; Lauwers, L.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Modelling farm-level economic potential for conversion to organic farming. Agricultural Systems 2007, 94, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoyer, S.; Préget, R. Enriching the CAP evaluation toolbox with experimental approaches: introduction to the special issue. European Review of Agricultural Economics 2019, 46, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanslembrouck, I.; Van Huylenbroeck, G.; Verbeke, W. Determinants of the Willingness of Belgian Farmers to Participate in Agri-environmental Measures. Journal of Agricultural Economics 2002, 53, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampe, I.; Würtenberger, D. Loss aversion and the demand for index insurance. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 2019, 180, 678–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastra-Bravo, X.B.; Hubbard, C.; Garrod, G.; Tolón-Becerra, A. What drives farmers' participation in EU agri-environmental schemes?: Results from a qualitative meta-analysis. Environmental Science & Policy 2015, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defrancesco, E.; Gatto, P.; Runge, F.; Trestini, S. Factors Affecting Farmers' Participation in Agri-environmental Measures: a Northern Italian Perspective. Journal of Agricultural Economics 2008, 59, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Goded, M.; Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; Ruto, E. What do farmers want from Agri-Environmental Scheme Design? a choice experiment approach. Journal of Agricultural Economics 2010, 61, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behaghel, L.; Macours, K.; Subervie, J. How can randomised controlled trials help improve the design of the common agricultural policy? European Review of Agricultural Economics 2019, 46, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, F. J.; Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; Van Bavel, R. Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: a policy-oriented review. European Review of Agricultural Economics 2019, 46, 417–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocean, N.; Howley, P. Using Choice Framing to Improve the Design of Agricultural Subsidy Schemes. Land Economics 2021, 97, 933–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. , Loss Aversion in Riskless Choice: A Reference-Dependent Model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 1991, 106, 1039–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science 1985, 4, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, N.; Klaes, M. An Introduction to Behavioral Economics. (3rd ed.) Palgrave Macmillan 2017.

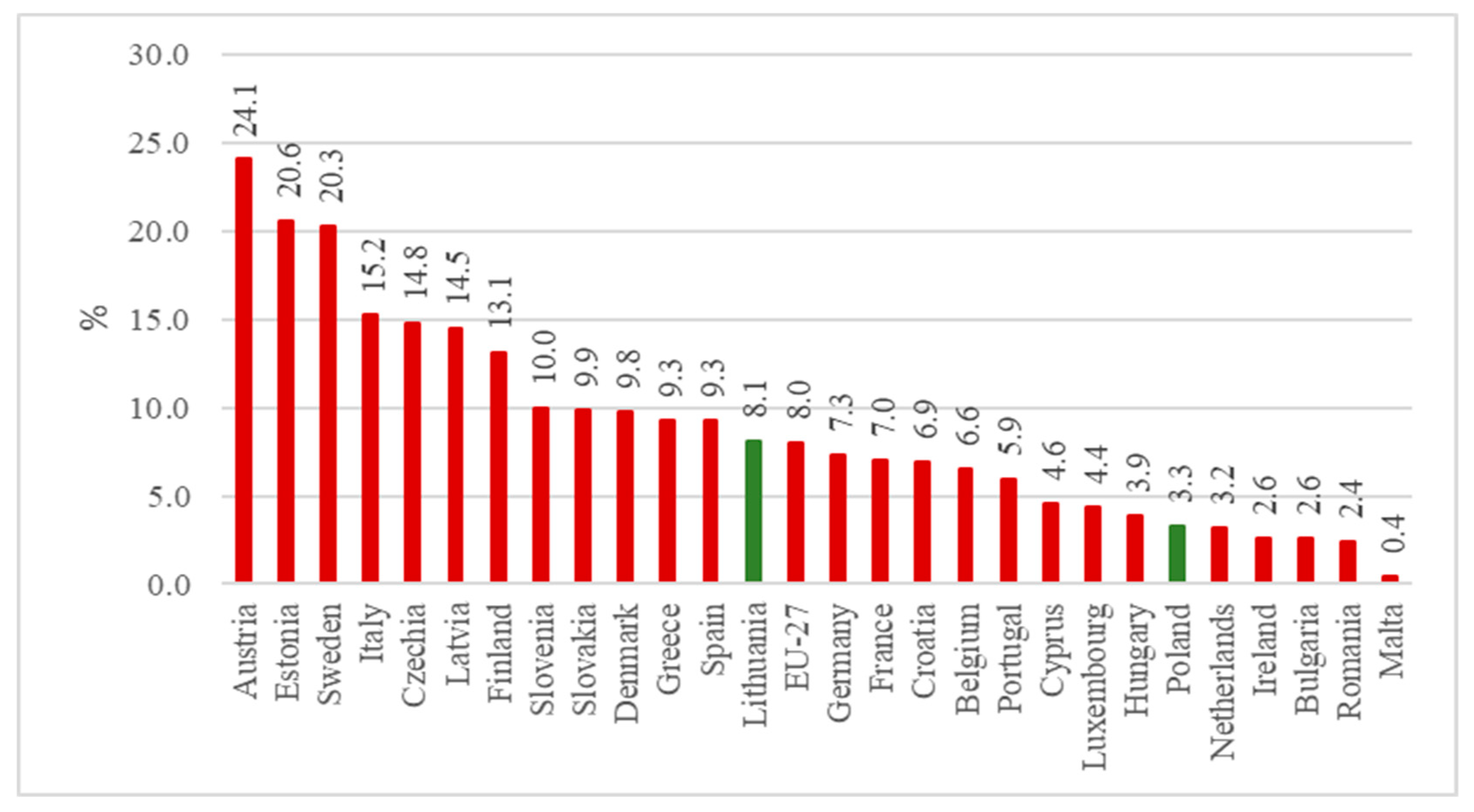

- Eurostat 2020. Organic farming statistics. Statistics explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Organic_farming_statistics (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Ekoagros. (2022). Veiklosataskaitos. Available online: https://www.ekoagros.lt/veiklos-ataskaitos-2 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Główna Inspekcja Jakości Handlowej Artykułów Rolno-Spożywczych. Raport o stanie rolnictwa ekologicznego w Polsce w latach 2019-2020. Warszawa, Poland 2021.

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. (2022). Roczniki Statystyczne. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Uematsu, H.; Mishra, K.A. Organic farmers or conventional farmers: Where's the money? Ecological Economics 2012, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligon, E. Supply and effects of specialty crop insurance. NBER Working Paper 2011, 16709. [Google Scholar]

- Belasco, E.; Galinato, S.; Marsh, T.; Miles, C.; Wallace, R. High tunnels are my crop insurance: An assessment of risk management tools for small-scale specialty crop producers. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 2013, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singerman, A. , Hart, E. C., & Lence, S. H. (2012). Revenue protection for organic producers: Too much or too little? Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 37. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, B.; Smith, V. What harm is done by subsidizing crop insurance. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2013, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belasco, E.; Schahczenski, J. Is organic farming risky? An evaluation of WFRP in organic and conventional production systems. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 2021, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 2009 | 2019 | Change 2019 compared to 2009 (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic farms | Conventional farms | Organic farms | Conventional farms | Organic farms | Conventional farms | |

| Age of farm operator (years) | 44 | 45 | 48 | 48 | 9.1 | 6.7 |

| Total costs per 1 ha of UAA (EUR) | 448 | 654 | 632 | 951 | 41.1 | 45.4 |

| Family labor force (FWU) | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.3 | -7.1 | -18.7 |

| Total utilized agricultural area (hectares) | 113 | 137 | 105 | 166 | -7.1 | 21.2 |

| Share of crop output in total output (%) | 74 | 68 | 61 | 69 | -17.6 | 1.5 |

| Income, per 1 ha of UAA (EUR) | 294 | 601 | 405 | 836 | 37.8 | 39.1 |

| Total liabilities per 1 ha of UAA (EUR) | 218 | 326 | 462 | 607 | 2.1 * | 86.2 |

| Total subsidies (excluding on investment) per 1 ha of UAA (EUR) | 359 | 163 | 361 | 223 | 0.6 | 36.8 |

| Variable | 2009 | 2019 | Change 2019 compared to 2009 (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic farms | Conventional farms | Organic farms | Conventional farms | Organic farms | Conventional farms | |

| Age of farm operator (years) | 45.1 | 43.8 | 47.4 | 45.2 | 5.1 | 3.2 |

| Total costs per 1 ha of UAA (EUR) | 3199 | 12636 | 3722 | 7868 | 16.3 | -37.7 |

| Family labor force (FWU) | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.6 | -12.5 | -5.9 |

| Total utilized agricultural area (hectares) | 34 | 35 | 29 | 34 | -14.7 | -2.9 |

| Share of crop output in total output (%) | 49 | 50 | 60 | 59 | 22.4 | 18.0 |

| Income, per 1 ha of UAA (EUR) | 1811 | 4236 | 2594 | 3719 | 43.2 | -12.2 |

| Total liabilities per 1 ha of UAA (EUR) | 1481 | 6352 | 1532 | 2736 | 3.4 | -56.9 |

| Total subsidies (excluding on investment) per 1 ha of UAA (EUR) | 1782 | 1180 | 2155 | 1535 | 20.9 | 30.1 |

|

Variable |

Years | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Age of farm operator | -0.017 (0.012) | -0.039 (0.013)*** | -0.015 (0.011) | -0.015 (0.012) | -0.004 (0.012) | -0.012 (0.012) | 0.022 (0.009)** |

0.007 (0.011) | 0.022 (0.010)** | 0.027 (0.010)*** | 0.014 (0.009) |

| Total costs | -0.006 (0.001)*** | -0.005 (0.001)*** | -0.004 (0.001)*** | -0.002 (0.001)*** | -0.006 (0.001)*** | -0.006 (0.001)*** | -0.005 (0.001)*** |

-0.005 (0.001)*** | -0.004 (0.000)*** | -0.003 (0.000)*** | -0.003 (0.000)*** |

| Family labor force | -0.268 (0.246) | -0.009 (0.254) | 0.122 (0.253) | -0.300 (0.300) | 0.147 (0.285) | -0.065 (0.292) | -0.035 (0.226) | -0.509 (0.290)* | -0.640 (0.299)** | -0.601 (0.275)** | -0.519 (0.261)** |

| Total utilized agricultural area | 0.002 (0.001)* | 0.002 (0.001)*** | 0.001 (0.001)* | 0.001 (0.001)* | 0.003 (0.001)*** | 0.003 (0.001)*** | 0.002 (0.001)*** | 0.003 (0.001)*** | 0.002 (0.001)*** | 0.001 (0.001)* | 0.001 (0.001) |

| Share of crop output in total output | 0.002 (0.003) | 0.000 (0.005) | 0.008 (0.006) | 0.017 (0.006)*** | 0.011 (0.006)* | 0.036 (0.007)*** | 0.018 (0.005)*** | 0.018 (0.006)*** | 0.001 (0.005) | 0.001 (0.004) | -0.002 (0.003) |

| Income from off-farm sources | 0.268 (0.325) | 0.356 (0.323) | 0.178 (0.279) | 0.246 (0.301) | 0.227 (0.314) | 0.399 (0.333) | 1.013 (0.274)*** | 1.295 (0.320)*** | 1.227 (0.289)*** | 0.653 (0.278)** | 0.916 (0.252)*** |

| Total liabilities | 0.001 (0.000)* | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | -0.000 (0.000) | 0.001 (0.000)* | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000)*** |

| Location in agriculturally less favoured areas | 0.034 (0.277) | -1.777 (0.357)*** | -0.776 (0.308)*** | -0.317 (0.316) | -1.304 (0.354)*** | -1.593 (0.371)*** | -0.498 (0.262)* | -0.676 (0.297)** | -0.489 (0.293)* | -0.687 (0.252)*** | -0.677 (0.235)*** |

| Total subsidies (excluding on investment) | 0.027 (0.002)*** | 0.037 (0.003)*** | 0.029 (0.002)*** | 0.034 (0.002)*** | 0.037 (0.003)*** | 0.045 (0.003)*** | 0.026 (0.002)*** | 0.026 (0.002)*** | 0.023 (0.002)*** | 0.021 (0.002)*** | 0.017 (0.001)*** |

|

Variable |

Years | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Age of farm operator | 0.020 (0.002)*** | 0.010 (0.109) | 0.016 (0.006)*** | 0.016 (0.003)*** | 0.017 (0.001)*** | 0.017 (0.001)*** | 0.028 (0.000)*** | 0.032 (0.000)*** | 0.022 (0.000)*** | 0.024 (0.000)*** | 0.027 (0.000)*** |

| Total costs | -0.000 (0.000)*** | -0.000 (0.000)*** | -0.000 (0.000)*** | -0.000 (0.000)*** | -0.000 (0.000)*** | -0.000 (0.000)*** | -0.000 (0.000)*** | -0.000 (0.000)*** | -0.000 (0.000)*** | -0.000 (0.000)*** | -0.000 (0.000)*** |

| Family labor force | -0.491 (0.000)*** | -0.500 (0.000)*** | -0.585 (0.000)*** | -0.571 (0.000)*** | -0.442 (0.000)*** | -0.441 (0.000)*** | -0.380 (0.001)*** | -0.235 (0.035)** | -0.128 (0.223) | -0.161 (0.115) | -0.204 (0.051)* |

| Total utilized agricultural area | -0.001 (0.247) | -0.002 (0.176) | -0.002 (0.202) | -0.001 (0.648) | -0.002 (0.166) | -0.001 (0.303) | -0.005 (0.021)** | -0.008 (0.001)*** | -0.005 (0.013)** | -0.006 (0.003)*** | -0.004 (0.037)** |

| Share of crop output in total output | -0.763 (0.001)*** | -0.651 (0.004)*** | -0.601 (0.006)*** | -0.417 (0.039)** | -0.535 (0.002)*** | -0.249 (0.186) | 0.079 (0.683) | 0.109 (0.573) | -0.012 (0.950) | -0.384 (0.021)** | -0.445 (0.010)** |

| Income from off-farm sources | 0.122 (0.527) | -0.017 (0.925) | -0.134 (0.503) | 0.086 (0.621) | 0.294 (0.045)** | 0.237 (0.134) | 0.230 (0.172) | 0.113 (0.448) | 0.067 (0.658) | -0.120 (0.443) | 0.139 (0.312) |

| Total liabilities | 0.000 (0.009)*** | 0.000 (0.000)*** | 0.000 (0.761) | 0.000 (0.247) | 0.000 (0.135) | 0.000 (0.804) | 0.000 (0.662) | 0.000 (0.199) | 0.000 (0.697) | 0.000 (0.161) | 0.000 (0.001)*** |

| Location in agriculturally less favoured areas | 0.659 (0.000)*** | 0.917 (0.000)*** | 0.949 (0.000)*** | 0.933 (0.000)*** | 0.967 (0.000)*** | 1.117 (0.000)*** | 1.003 (0.000) *** | 1.108 (0.000)*** | 1.013 (0.000)*** | 1.017 (0.000)*** | 0.444 (0.204) |

| Total subsidies (excluding on investment) | 0.001 (0.000)*** | 0.001 (0.000)*** | 0.001 (0.000)*** | 0.000 (0.000)*** | 0.001 (0.000)*** | 0.000 (0.000)*** | 0.000 (0.000)*** | 0.001 (0.000)*** | 0.000 (0.000)*** | 0.000 (0.000)*** | 0.001 (0.000)*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).