Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

17 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

The Timing of Puberty

Genetic Factors

Adrenarche

Body Weight and Puberty

Childhood Obesity

EDCs and Puberty

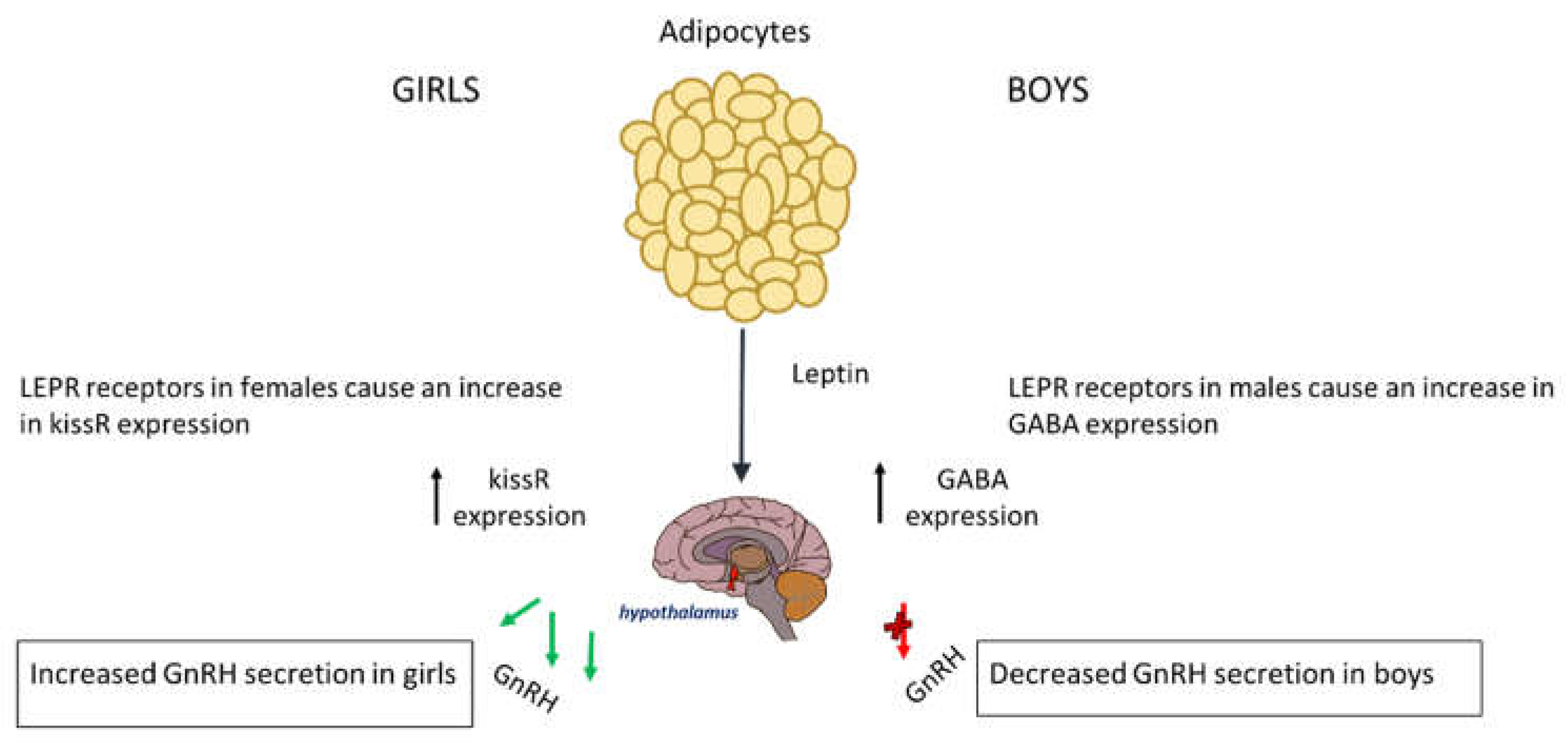

Adipokines (Leptin and Adiponectin)

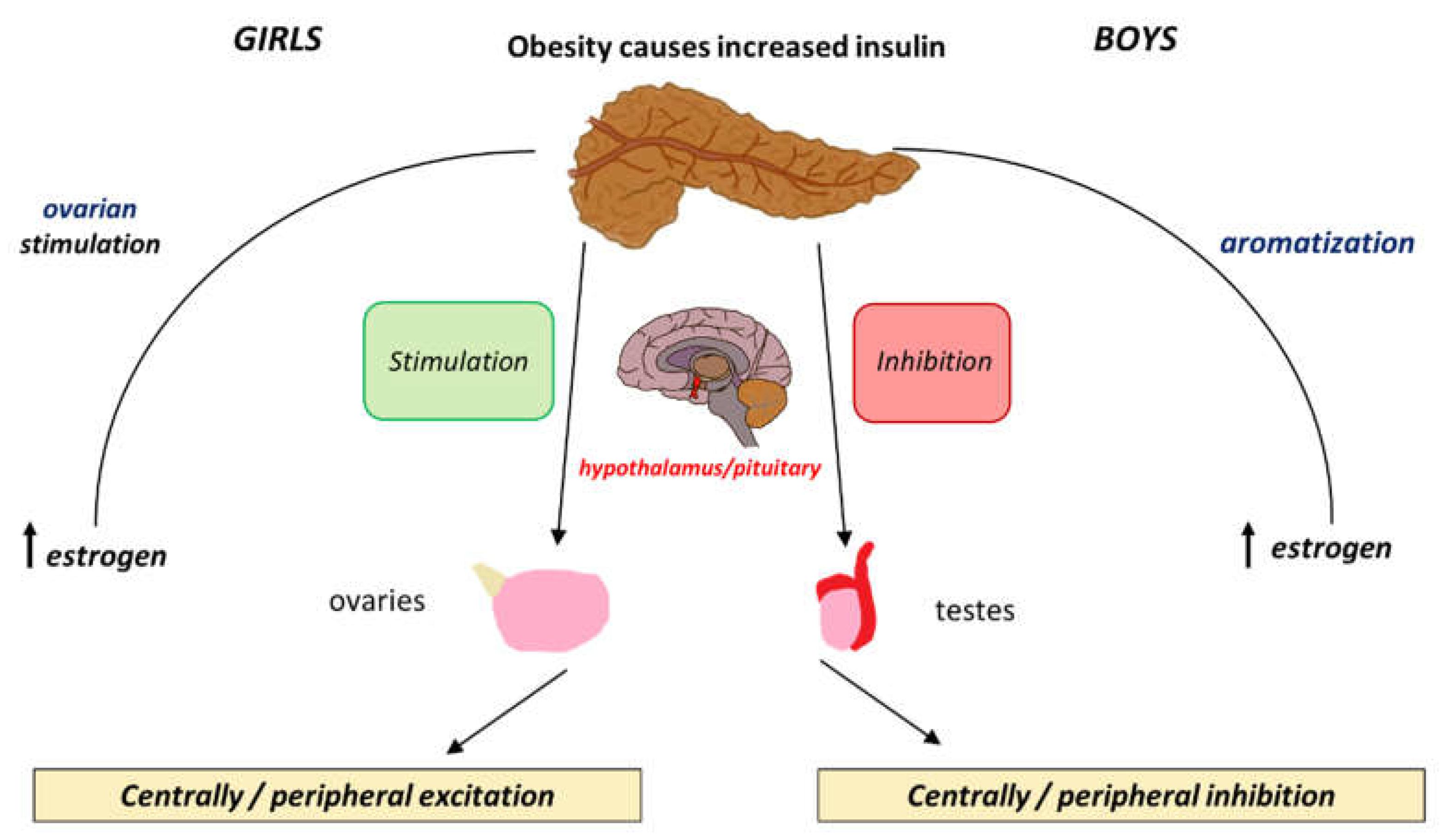

Insulin

SGA, Obesity and Premature Gonadarche

Conclusion

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

References

- Breehl, L. Physiology, puberty, StatPearls [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534827/ (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Vijayakumar, N.; et al. Puberty and the human brain: Insights Into Adolescent Development, Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2018. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6234123/ (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Manotas, M.C.; et al. Genetic and epigenetic control of puberty, Sexual development: genetics, molecular biology, evolution, endocrinology, embryology, and pathology of sex determination and differentiation. 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8820423/ (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Joseph, D.N.; Whirledge, S. Stress and the HPA axis: Balancing homeostasis and fertility, International journal of molecular sciences. 2017. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5666903/#:~:text=As%20part%20of%20the%20physiological,reproductive%20competence%20of%20an%20organism (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Abreu, A.P.; Kaiser, U.B.; Pubertal development and regulation, The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology. 2016. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5192018/ (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Cunningham, S.A.; et al. Changes in the incidence of childhood obesity, Pediatrics. 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9879733/ (accessed on 01 June 2024).

- Eckert-Lind, C.; et al. Worldwide secular trends in age at pubertal onset assessed by breast development among girls: A systematic review and meta-analysis, JAMA pediatrics. 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7042934/ (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Wohlfahrt-Veje, C.; et al. ‘Pubarche and Gonadarche Onset and Progression Are Differently Associated With Birth Weight and Infancy Growth Patterns’, Journal of the Endocrine Society, 5(8). 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvab108 (accessed on 01 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Beccuti, Guglielmo, and Lucia Ghizzoni. “Normal and Abnormal Puberty.” PubMed, MDText.com, Inc. 2000. Available online: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279024/ (accessed on 01 June 2024).

- Yang, D.; et al. Initiation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in young girls undergoing central precocious puberty exerts remodeling effects on the prefrontal cortex, Frontiers in psychiatry. 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6524415/ (accessed on 01 June 2024).

- Author links open overlay panelMatteo Spaziani a b et al. Hypothalamo-pituitary axis and puberty, Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2020. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0303720720303968?via%3Dihub (accessed on 01 June 2024).

- Blair, J.A.; et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis involvement in learning and memory and alzheimer’s disease: More than ‘just’ estrogen, Frontiers in endocrinology. 2015. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4373369/ (accessed on 01 June 2024).

- Guercio, G.; et al. Estrogens in human male gonadotropin secretion and testicular physiology from infancy to late puberty, Frontiers in endocrinology. 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7051936/ (accessed on 01 June 2024).

- Shaw, N.D.; et al. Estrogen negative feedback on gonadotropin secretion: Evidence for a direct pituitary effect in women, The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2010. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2853991/ (accessed on 05 June 2024).

- Manotas, M.C.; et al. Genetic and epigenetic control of puberty, Karger Publishers. 2021. Available online: https://karger.com/sxd/article/16/1/1/829199/Genetic-and-Epigenetic-Control-of-Puberty (accessed on 05 June 2024).

- Chan, Y.-M.; et al. Using kisspeptin to predict pubertal outcomes for youth with pubertal delay, The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7282711/ (accessed on 05 June 2024).

- Christoforidis, A.; Skordis, N.; Fanis, P.; Dimitriadou, M.; Sevastidou, M.; Phelan, M.M.; Neocleous, V.; Phylactou, L.A. A novel MKRN3 nonsense mutation causing familial central precocious puberty. Endocrine. 2017, 56, 446–449. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-017-1232-6 (accessed on 5 June 2024). [PubMed]

- Howard, S.R. The Genetic Basis of Delayed Puberty. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2019, 10. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00423 (accessed on 5 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Faienza, M.F.; Urbano, F.; Moscogiuri, L.A.; Chiarito, M.; De Santis, S.; Giordano, P. . Genetic, epigenetic and enviromental influencing factors on the regulation of precocious and delayed puberty. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2022, 13, 1019468. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1019468 (accessed on 5 June 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagani, S.; et al. MKRN3 and KISS1R mutations in precocious and early puberty, Italian journal of pediatrics. 2017. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7104496/ (accessed on 05 June 2024).

- Neocleous, V.; Shammas, C.; Phelan, M.M.; Nicolaou, S.; Phylactou, L.A.; Skordis, N. In silico analysis of a novelMKRN3missense mutation in familial central precocious puberty. Clinical Endocrinology 2015, 84, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanis, P.; Skordis, N.; Toumba, M.; Papaioannou, N.; Makris, A.; Kyriakou, A.; Neocleous, V.; Phylactou, L.A. Central Precocious Puberty Caused by Novel Mutations in the Promoter and 5′-UTR Region of the Imprinted MKRN3 Gene. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfield, R.L. Normal and premature adrenarche, Endocrine reviews. 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8599200/ (accessed on 06 June 2024).

- Sheng, J.A.; et al. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: Development, programming actions of hormones, and maternal-fetal interactions, Frontiers. 2020. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2020.601939/full (accessed on 06 June 2024).

- Heck, A.L.; Handa, R.J. Sex differences in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis’ response to stress: An important role for gonadal hormones, Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6235871/ (accessed on 07 June 2024).

- Stephens, M.A.C.; et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to acute psychosocial stress: Effects of biological sex and circulating sex hormones, Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4788592/ (accessed on 07 June 2024).

- Obesity and overweight [Internet]. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Prevalence of obesity [Internet]. World Obesity Federation. Available online: https://www.worldobesity.org/about/about-obesity/prevalence-of-obesity (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Tiwari, A.; Daley, S.F.; Balasundaram, P. Obesity in Pediatric Patients [Updated 2023 Mar 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570626/.

- Nicolaou, M.; Toumba, M.; Kythreotis, A.; Daher, H.; Skordis, N. Obesogens in adolescence: Challenging Aspects and Prevention Strategies. Children 2024, 11, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E.; Jung, H.W.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, Y.A. Early-life exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and pubertal development in girls. Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism 2019, 24, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, A.C.; Chappell, V.A.; Fenton, S.E.; Flaws, J.A.; Nadal, A.; Prins, G.S.; et al. EDC-2: The endocrine society’s second scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Endocrine Reviews 2015, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nah, W.H.; Park, M.J.; Gye, M.C. Effects of early prepubertal exposure to bisphenol A on the onset of puberty, ovarian weights, and estrous cycle in female mice. Clinical and Experimental Reproductive Medicine 2011, 38, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tassinari, R.; Tait, S.; Busani, L.; Martinelli, A.; Narciso, L.; Valeri, M.; et al. Metabolic, reproductive and thyroid effects of Bis(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) orally administered to male and female juvenile rats at dose levels derived from children biomonitoring study. Toxicology 2021, 449, 152653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalitin, S.; Gat-Yablonski, G. Associations of obesity with linear growth and puberty. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 2021, 95, 120–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Rodríguez, D.; Aylwin, C.F.; Delli, V.; Sevrin, E.; Campanile, M.; Martin, M.; et al. Multi- and transgenerational outcomes of an exposure to a mixture of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (edcs) on puberty and maternal behavior in the female rat. Environmental Health Perspectives 2021, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucaccioni, L.; Trevisani, V.; Marrozzini, L.; Bertoncelli, N.; Predieri, B.; Lugli, L.; et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and their effects during female puberty: A review of current evidence. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamska-Patruno, E.; et al. The relationship between the leptin/ghrelin ratio and meals with various macronutrient contents in men with different nutritional status: A randomized crossover study, Nutrition journal. 2018. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6309055/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Picó, C.; Palou, M.; Pomar, C.A.; Rodríguez, A.M.; Palou, A. Leptin as a key regulator of the adipose organ. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders 2021, 23. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-021-09687-5 (accessed on 10 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, Q.; Deng, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Story, M. Association between Obesity and Puberty Timing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2017, 14, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dDunger, D.B.; Lynn Ahmed, M.; Ong, K.K. Effects of obesity on growth and puberty. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2005, 19, 375–390. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2005.04.005 (accessed on 8 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.G.; Leibel, R.L.; Seeley, R.J.; Schwartz, M.W. . Obesity and leptin resistance: distinguishing cause from effect. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2010, 21, 643–651. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2010.08.002 (accessed on 8 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.L.; Sainsbury, A.; Garden, F.; Sritharan, M.; Paxton, K.; Luscombe, G.; Hawke, C.; Steinbeck, K. Ghrelin and Peptide YY Change During Puberty: Relationships With Adolescent Growth, Development, and Obesity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2018, 103, 2851–2860. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-01825 (accessed on 10 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Reinehr, T.; Roth, C.L. Connections between obesity and puberty: Invited by Manuel Tena-Sempere, Cordoba, Current opinion in endocrine and metabolic research. 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7543977/#:~:text=Longitudinal%20studies%20clearly%20demonstrate%20that,puberty%20and%20age%20of%20menarche (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Shi, L.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, L. Childhood obesity and central precocious puberty, Frontiers in endocrinology. 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9716129/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Odle, A.K.; et al. Leptin regulation of Gonadotrope gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors as a metabolic checkpoint and gateway to reproductive competence, Frontiers in endocrinology. 2018. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5760501/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- d Machinal-Quélin, F.; Dieudonné, M.-N.; Pecquery, R.; Leneveu, M.-C.; Giudicelli, Y. Direct In Vitro Effects of Androgens and Estrogens on ob Gene Expression and Leptin Secretion in Human Adipose Tissue. Endocrine 2002, 18, 179–184. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1385/endo:18:2:179 (accessed on 8 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplowitz, P. Delayed puberty in obese boys: Comparison with constitutional delayed puberty and response to testosterone therapy. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1998, 133, 745–749. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70144-1 (accessed on 13 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zuure, W.A.; Roberts, A.L.; Quennell, J.H.; Anderson, G.M. Leptin Signaling in GABA Neurons, But Not Glutamate Neurons, Is Required for Reproductive Function. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013, 33, 17874–17883. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.2278-13.2013 (accessed on 13 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ahima, R.S. No Kiss1ng by leptin during puberty? Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011, 121, 34–36. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1172/jci45813 (accessed on 13 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, D.; Pujol-Gualdo, N.; Arnoldussen, I.A.C.; Kiliaan, A.J. Adipokines: A gear shift in puberty. Obesity Reviews. 2020, 21. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13005 (accessed on 18 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Kong, Y.; Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N. Association between precocious puberty and obesity risk in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2023, 11. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2023.1226933 (accessed on 13 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ahl, S.; Guenther, M.; Zhao, S.; James, R.; Marks, J.; Szabo, A.; Kidambi, S. Adiponectin Levels Differentiate Metabolically Healthy vs Unhealthy Among Obese and Nonobese White Individuals. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2015, 100, 4172–4180. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2015-2765 (accessed on 08 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Atilla Engin 2017. Adiponectin-Resistance in Obesity. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, pp.415–441. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_18 (accessed on 08 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhong, L.; Li, G.; Han, L.; Fu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, X.; Qi, L.; Li, M.; Gao, S.; Willi Steven, M. Puberty Status Modifies the Effects of Genetic Variants, Lifestyle Factors and Their Interactions on Adiponectin: The BCAMS Study. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2021, 12, 737459. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.737459 (accessed on 18 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, M.; Yin, J.; Cheng, H.; Yu, M.; Zhao, X.; Xiao, X.; Mi, J. Change of Body Composition and Adipokines and Their Relationship with Insulin Resistance across Pubertal Development in Obese and Nonobese Chinese Children: The BCAMS Study. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2012, 2012, 389108. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/389108 (accessed on 20 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Barbe, A.; Bongrani, A.; Mellouk, N.; Estienne, A.; Kurowska, P.; Grandhaye, J.; Elfassy, Y.; Levy, R.; Rak, A.; Froment, P.; Dupont, J. Mechanisms of Adiponectin Action in Fertility: An Overview from Gametogenesis to Gestation in Humans and Animal Models in Normal and Pathological Conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019, 20, 1526. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20071526 (accessed on 20 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ohman-Hanson, R.A.; Cree-Green, M.; Kelsey, M.M.; Bessesen, D.H.; Sharp, T.A.; Pyle, L.; Pereira, R.I.; Nadeau, K.J. Ethnic and Sex Differences in Adiponectin: From Childhood to Adulthood. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2016, 101, 4808–4815. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-1137 (accessed on 20 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, M.M.; Zeitler, P.S. Insulin Resistance of Puberty. Current Diabetes Reports. 2016, 16. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-016-0751-5 (accessed on 24 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Gołacki, J.; Matuszek, M.; Matyjaszek-Matuszek, B. Link between Insulin Resistance and Obesity—From Diagnosis to Treatment. Diagnostics. 2022, 12, 1681. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12071681 (accessed on 25 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Saleh, F.L.; Joshi, A.A.; Tal, A.; Xu, P.; Hens, J.R.; Wong, S.L.; Flannery, C.A. Hyperinsulinemia induces early and dyssynchronous puberty in lean female mice. Journal of Endocrinology. 2022, 254, 121–135. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1530/joe-21-0447 (accessed on 27 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Sliwowska, J.H.; Fergani, C.; Gawałek, M.; Skowronska, B.; Fichna, P.; Lehman, M.N. Insulin: Its role in the central control of reproduction. Physiology & Behavior. 2014, 133, 197–206. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.05.021 (accessed on 28 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Burt Solorzano, C.M.; McCartney, C.R. Obesity and the pubertal transition in girls and boys. REPRODUCTION. 2010, 140, 399–410. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1530/rep-10-0119 (accessed on 28 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mauras, N.; Ross, J.; Mericq, V. Management of Growth Disorders in Puberty: GH, GnRHa, and Aromatase Inhibitors: A Clinical Review. Endocrine Reviews. 2022. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnac014 (accessed on 30 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Nassar, G.N.; Raudales, F.; Leslie, S.W. Physiology, Testosterone [online]. PubMed. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526128/ (accessed on 04 July 2024).

- Osuchukwu, O.O.; Reed, D.J. Small for Gestational Age [online]. PubMed. 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563247/ (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Hong, Y.H.; Chung, S. Small for gestational age and obesity related comorbidities. Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2018, 23, 4–8. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2018.23.1.4 (accessed on 20 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Shi, H.; Huo, Y.; Liu, M.; Sun, F.; Lan, H.; Guo, C.; Liu, H.; Li, T.; Jiang, L.; Hu, X.; Li, T.; Xu, J.; Yao, G.; Zhu, G.; Yu, G.; Chen, J. Rapid BMI Increases and Persistent Obesity in Small-for-Gestational-Age Infants. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2021a, 9, 625853. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.625853 (accessed on 22 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.-K.; Lee, K.-H. Small for gestational age and obesity: epidemiology and general risks. Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2018, 23, 9–13. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2018.23.1.9 (accessed on 22 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Verkauskiene, R.; Petraitiene, I.; Albertsson Wikland, K. Puberty in children born small for gestational age. Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 2013, 80, 69–77. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1159/000353759 (accessed on 25 July 2024). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).