1. Introduction

Asprosin is a glucogenic adipokine, discovered very recently, in 2016, synthesized and produced by adipocytes. The protein is primarily produced and released by white adipose tissue during fasting and plays a complex role in the biochemistry of the central nervous system, peripheral tissues, and various organs. It is involved in the regulation of appetite, glucose metabolism, insulin resistance, and cell apoptosis [

1]. Plasma asprosin level shows diurnal oscillations, characterized by lower concentrations at the time of the first food intake after the overnight fasting period. As far as night fasting is concerned, it is known to be connected with elevated concentration of circulating asprosin in serum [

2]. Certain disturbances in asprosin secretion may occur in individuals with metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, or obesity–as it has been shown that asprosin levels are significantly elevated in these individuals [

3].

Fertility is understood as the ability to achieve clinical pregnancy within 12 months of regular unprotected sexual intercourse. It can be influenced by many factors, related both to women and men [

4,

5,

6]. Currently, difficulties with conception are recognized as a global problem that affects an increasing number of people but it is still in need of adequate efforts both as a research area and as a health policy concern [

7]. The latest data indicate that as much as 48 million couples (186 million people) worldwide suffer from infertility [

7,

8,

9]. The numbers reported in literature are mainly based on a 2012 study [

10], with the most recent estimates, such as the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 [

5], published in 2025, predicting that approximately 55 million men and 110 million women aged 15–49 would be affected by infertility globally in 2021. The fact that forecasts predict that increasing numbers of people will be affected by infertility—along with indicating the need for better clinical outcomes as far as pregnancy rates are concerned—suggests that research in the field is very much needed.

Recent studies in men have indeed pointed to the existence of a relationship between asprosin and fertility [

11]. It has been established that asprosin mitigates the decline in fertility potential associated with aging and obesity by improving sperm motility [

12]. In the case of women, the role of asprosin in fertility is currently unclear. In a broad context, asprosin may represent an important link between adipose tissue activity, metabolic health, and various aspects of female physiology. An excessive amount of body fat is an aspect of human biology that is known to be influenced by lifestyle choices and negatively affect fertility [

13]. The reason for this lies in the fact that adipose tissue is not merely a fat storage depot but also an exceptionally active endocrine organ. As a source of adipokines, adipose tissue plays a role in regulating numerous physiological and pathological processes, with many adipokines exhibiting multifunctional effects [

12]. Therefore, examining the role of asprosin in women could contribute valuable insights about the metabolic and endocrine factors that have an impact on female health, including its aspects connected with fertility.

Apart from its association with fertility through its involvement in metabolic processes, asprosin may also be linked with certain aspect physiology more directly connected with female fertility. Leonard et al. [

14] demonstrated that asprosin levels fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle and that the use of contraception is associated with a decrease in asprosin level. How this association translates into the broader context of fertility, however, is currently unclear. Moreover, some studies have shown an association between increased serum asprosin levels and the risk of developing polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a common disorder affecting 6–10% of women [

9], while other studies do not show such a relationship [

15]. The former finding primarily confirms that asprosin levels are elevated in individuals with insulin resistance, whereas a direct link between asprosin and infertility has not been investigated. In other words, the observed increase in asprosin levels among women with PCOS most probably reflects the frequent co-occurrence of obesity and insulin resistance in the population. Previous research conducted by the authors of the present study, investigating the relationship between body composition parameters, the intake of specific nutrients, and AMH level in the context of ovulatory infertility, demonstrated that body composition—including parameters such as percentage body fat (PBF) and BMI—was associated with serum AMH concentrations, suggesting a possible link between the levels of various hormones known to be associated with changes in body composition, including asprosin, and AMH concentration [

16]. For these reasons—and considering that the role of asprosin in women is still an emerging research area—exploring relationships that could link asprosin and fertility seems to be a promising exploratory direction.

Considering the above, the limited scientific evidence currently available indicates possible links between various aspects of women’s physiology, including—but not limited to—those connected with fertility, and serum asprosin concentrations. In this respect, research is needed to clarify whether asprosin interacts with other female hormones and to what extent it may contribute to the understanding of female reproductive health. Given that the connections between asprosin and female fertility remain an emerging area of study with few studies available, the aim of this research was to explore the role of asprosin in female physiology, with a focus on selected endocrine and lifestyle-related factors that may be associated with female fertility. This approach is based on the current literature data and the authors’ previous findings.

2. Materials and Methods

This case-controlled study was conducted on 56 women, aged 25 to 42. The participants were patients of the Reproductive Health Clinic and the Clinic of Endocrinology, Diabetology, and Internal Medicine of the Medical University of Białystok, Poland. The participants were recruited and underwent diagnostic and therapeutic procedures as part of the clinics’ standard medical practice between September 2023 to March 2025.

The data used for this study were obtained from the records collected during routine clinical operation in the aforementioned clinics, in line with the ethical approval granted by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Białystok (APK.002.99.2023, dated 16 February 2023). Informed consent for participation in the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures was obtained from all patients. Since the analysis was based on existing data collected in the course of routine care, no additional follow-up visits were scheduled specifically for the purposes of this study.

2.1. Hormonal and Biochemical Assessments

The levels of the following reproductive hormones were measured: anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), prolactin (PRL), estradiol, progesterone, testosterone, and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). Tubal patency was assessed using sonohysterography (sono-HSG). To rule out thyroid disease, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels were also determined. All the assessments were conducted by trained and experienced gynecologists. Blood samples for progesterone measurement were collected during the luteal phase, while samples for the other hormonal tests were collected during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. The levels of asprosin, fasting glucose, insulin, cholesterol were measured. In the case of blood parameters with values reported as below or above the limit of quantification (LOQ), the respective lower or upper LOQ was imputed.

2.2. Anthropometric Measurements and Lifestyle Factors

Body composition was assessed through bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) using the InBody 720 device. Parameters such as body weight, height, body mass index (BMI), percent body fat (PBF), and visceral fat content/area (VFA) were evaluated. As far as lifestyle-related parameters are concerned, one variable was assessed, i.e., night fasting duration, calculated based on a weighted average of the mean hours of sleep during weekdays and weekends.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Normality of distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Due to the lack of normality of the distribution of variables, Spearman’s rank correlation was used. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses were conducted, with serum asprosin concentration as the dependent variable, to examine its associations with selected independent variables. The univariate analysis tested the effect of each variable separately, while the multivariate model aimed to explain variations in asprosin concentrations under the combined influence of selected predictors. In order to evaluate the accuracy of the linear regression model, the model fit to the data was checked. Only patients whose data were complete were included in the analysis.

Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The results were processed using Stata 18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

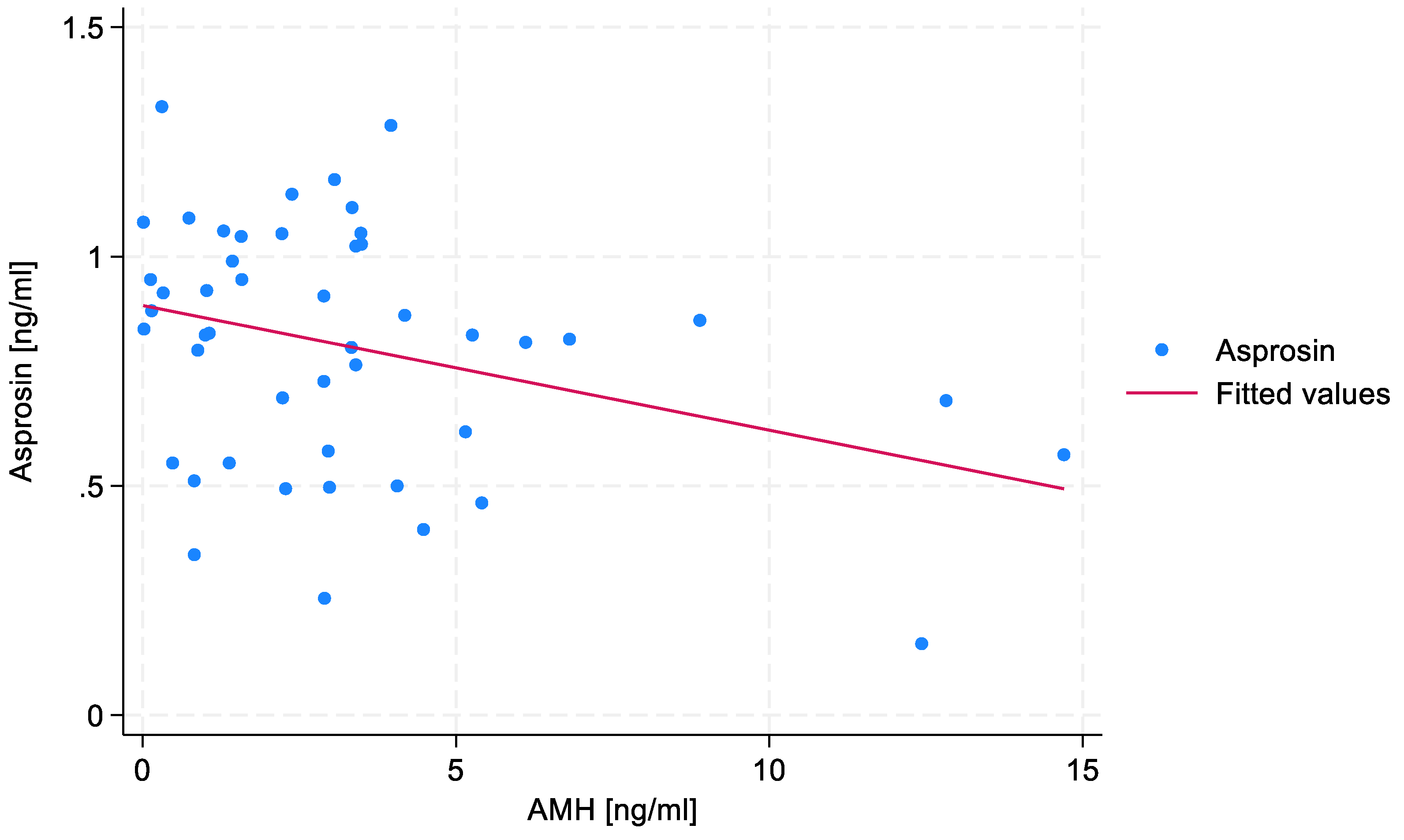

No statistically significant correlations were found between estradiol, SHBG or testosterone levels, and serum asprosin concentration. A negative, weak correlation (R=-0.271) between AMH level and serum asprosin concentration was found, the significance of which slightly exceeded the assumed statistical significance threshold (p=0.06). The absence of data points in the upper-right section of the diagram indicates that none of the patients exhibited both high AMH and high asprosin levels. The correlation between AMH level and serum asprosin level is shown in

Figure 1.

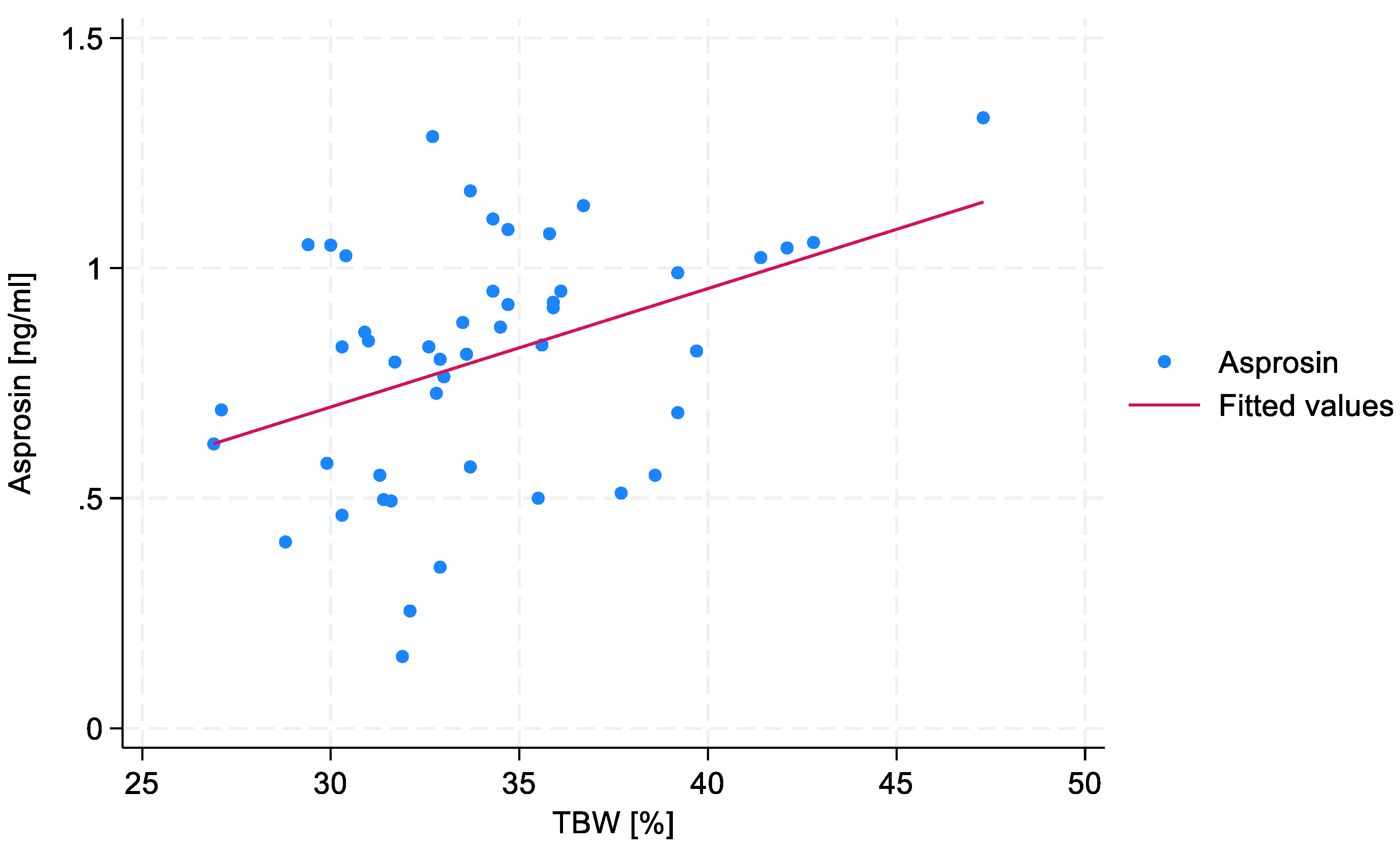

No statistically significant correlations were found between VFA, PBF or BMI, and serum asprosin concentration. However, a statistically significant, medium correlation (R=0.38) was observed between TBW and serum asprosin concentration (p=0.008). This relationship is shown in

Figure 2.

Although suspected, no significant differences were identified when the study group was stratified according to BMI categories.

Table 1 presents the distribution of the key tested parameters according to BMI categories. The results suggest that BMI can be excluded as a potential confounding variable.

No statistically significant correlation was found between night fasting duration and serum asprosin concentration.

Univariate linear regression analysis was performed for all the variables selected for analysis (Table 2). Statistically significant results are marked with an asterisk.

Table 2.

Results of univariate linear regression analyses of the associations between parameters connected with hormone levels, body composition and lifestyle, and serum asprosin concentration.

Table 2.

Results of univariate linear regression analyses of the associations between parameters connected with hormone levels, body composition and lifestyle, and serum asprosin concentration.

| Variable |

Estimate |

95% CI |

p-value |

| Hormones |

| AMH |

-0.0272 |

-0.0501 |

-0.0043 |

0.02* |

| Estradiol |

0.0005 |

-0.0019 |

0.0029 |

0.69 |

| SHBG |

-0.0011 |

-0.0032 |

0.0009 |

0.28 |

| Testosterone |

-0.0405 |

-0.8103 |

0.0003 |

0.05 |

| Body composition |

| TBW |

0.0257 |

0.0082 |

0.0433 |

0.005* |

| VFA |

0.0015 |

-0.0016 |

0.0046 |

0.34 |

| PBF |

0.0057 |

-0.0066 |

0.0181 |

0.36 |

| BMI |

0.0118 |

-0.0056 |

0.0292 |

0.18 |

| Lifestyle-related parameters |

| Night fasting |

-0.0295 |

-0.0800 |

0.0209 |

0.24 |

Based on the results of the univariate linear regression analysis, an attempt was made to construct a multivariate model. Although several parameters showed a statistically significant association with serum asprosin level in the univariate analyses, not all of them were included in the proposed model. Moreover, some variables that were not statistically significant in the univariate regression analyses were considered in the multivariate model due to their suspected biological significance in the studied processes. Ultimately, the desiged model was based on the following three parameters: AMH, TBW, and night fasting duration (Table 2). The adjusted R² value of the model, explaining the variability in serum asprosin concentration, was 23.42%, indicating that over 23% of the variability in asprosin concentration is explained by this model.

Table 2.

The multivariate linear regression model explaining variability in serum asprosin concentration.

Table 2.

The multivariate linear regression model explaining variability in serum asprosin concentration.

| Variable |

Estimate |

95% CI |

p-value |

| AMH |

-0.0310 |

-0.0529 |

-0.0090 |

0.007* |

| TBW |

0.0232 |

0.0046 |

0.0419 |

0.02* |

| Night fasting |

-0.0573 |

-0.0104 |

-0.0104 |

0.02* |

4. Discussion

This exploratory study examined associations between the levels of selected parameters related to hormones, body composition, and lifestyle, and serum asprosin concentrations. The direction of the exploration was pointed towards potential associations between asprosin and female fertility. As the available scientific literature focuses on men and thus lacks studies that would focus on asprosin as a potential indicator of female infertility—largely due to the hormone itself being a relatively recent discovery [

17]—the results may prove valuable in the context of possible new research directions.

The most notable result of the study in terms of fertility may be the negative correlation between the concentrations of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and serum asprosin. As AMH concentration is a key marker of ovarian reserve, this finding suggests that higher asprosin level may be linked to lower ovarian reserve, potentially indicating that asprosin is involved in—or is an indicator of—mechanisms that negatively affect female fertility. In particular, the fact that no patient exhibited concurrent high concentrations of both hormones needs to be emphasized. This relationship, however, can also be explained by the fact that individuals with overweight or obesity—who often exhibit higher asprosin levels [

18]—may also be characterized by lower levels of AMH [

19]. In view of these findings, it must be pointed out that the study group in the present research included individuals with both normal and elevated BMI. Since obesity is known to be associated with increased circulating asprosin levels, and individuals with higher BMI also show lower AMH concentrations compared to those with normal BMI, the results discussed above should be confirmed in a more homogeneous group, despite the fact that the present in the present group BMI did not differ significantly between the compared subgroups and was thus unlikely to confound the results.

As far as the associations between the levels of other hormones known to be involved in fertility and serum asprosin concentrations are concerned, the results of this study did not show any statistically significant relationships. However, a negative correlation between the concentrations of SHBG and serum asprosin has been established. Although the association did not reach statistical significance, the result is partly consistent with the findings of Li et al. [

20], who showed that while asprosin concentration is positively correlated with testosterone level, it is correlated negatively with estradiol and SHBG levels; however, Li et al. tested these relationships only in women with PCOS. For this reason, studies in healthy women are needed to confirm or disprove these findings for the general female population. Hence, the discrepancies in results may stem from the heterogeneity of the tested study populations, as well as the presence of confounders, indicating that the role of asprosin within the endocrine system as a whole—and in the pathogenesis of fertility disorders in particular—is still unclear and needs further studies.

Contrary to expectations, no significant associations were found between the levels of several parameters connected with body composition, such as BMI, PBF, and VFA, and serum asprosin concentrations. This may be considered a surprising result, given that asprosin is secreted by adipose tissue and is often elevated in individuals with overweight or obesity [

3,

21]. However, there are no studies demonstrating such an association in individuals with normal fat levels, which may explain the lack of correlation observed in this study.

On the other hand, a positive correlation was observed between TBW and serum asprosin concentration. Although TBW is not typically considered a direct fertility marker, its correlation with asprosin concentration may reflect an underlying relationship between hydration status, body composition, and metabolic hormone regulation, and asprosin. Due to the fact that unhealthy body composition often results from unhealthy lifestyle choices, which can impact infertility, establishing such relationships may be useful in the context of female fertility [

13]. Although there are no studies concerning the relationship between body composition, especially TBW and asprosin, the results of a study performed by Hebbar et al. [

22] indicate that TBW concentrations correlate with those of other adipokines, such as adiponectin, leptin, or adipsin, which indirectly points to the possibility that asprosin concentration may be connected with lifestyle-dependent biological processes known to be associated with infertility. Although the results of this study did not show a statistically significant relationship between the other tested body composition parameters (BMI, PBF, and VFA) and serum asprosin concentration, in each case the observed association was positive, which is consistent with the findings reported in the literature [

23,

24]. The lack of statistical significance may have resulted from the small size of the study group. The relationships between body composition and asprosin is thus yet another research area worth exploring, also in connection with female fertility.

Interestingly, night fasting duration did not show a significant correlation with serum asprosin concentration, despite the fact that the hormone is known to be secreted in greater amounts during prolonged fasting [

2,

12]. However, when included in the multivariate model, the duration of night fasting was unexpectedly found to have a statistically significant negative association with serum asprosin concentration. This is inconsistent with previous findings which indicated the opposite relationship, i.e., increased asprosin levels following night fasting [

2]. This discrepancy may be connected with the character of the study group as far as metabolic parameters are concerned. Various studies have shown that asprosin levels are significantly elevated in individuals with obesity or metabolic syndrome [

3,

21,

25], as well as in those with carbohydrate metabolism disorders [

26]. Since the tested study group included individuals with all the aforementioned conditions, this most likely had an impact on the results. In the context of fertility, this could imply that certain dietary patterns may be reflected in asprosin levels, which could potentially mean that asprosin concentration may be used as an indicator of diet-related infertility issues in women. In light of the findings of this study, it seems necessary to perform studies in more homogeneous study groups that—less susceptible to the factors identified above—that could shed more light on both the existence and direction of relationships between lifestyle choices, including those that are associated with female fertility, and asprosin.

The multivariate model constructed in the study explained over 23% of the variability in serum asprosin concentrations. This low predictive power is expected and unsurprising, as the variability in serum asprosin concentrations is unlikely to be explained to a large degree by variables that are secondary in the context of endocrine processes. More importantly, the result is interesting in that, unexpectedly, attempts at including BMI in the model did not increase its predictive power. In any case, the finding suggests that including asprosin in future research focused on links between lifestyle choices, metabolism, and female infertility is worth considering.

5. Conclusion

The findings of the exploratory study provide insights into the role of asprosin in females, particularly in relation to fertility—building upon and in some respect contradicting the results of the limited number of previous studies. The results of the study suggest that asprosin may play a role in mechanisms affecting female fertility, particularly in the context of ovarian reserve, and indirectly through its relationship with body composition, especially water distribution in the body. It should be emphasized that the observed relationships were likely affected by the high heterogeneity of the study group. The presence of possible confounding factors—such as underlying metabolic issues or significant lifestyle differences between individuals—makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Hence, make them less susceptible to confounders, future prospective studies should be conducted in more homogeneous groups, both metabolically and hormonally. After implementing such changes in methodology, it would be possible to determine the potential role of asprosin in females—including aspects connected with fertility—more reliably. Most notably, the findings suggest that links between female fertility and asprosin is a potentially viable direction; however, general research into the role of asprosin in female physiology should be a priority.

Limitations of the Study: The study sample consisted was relatively small, which may have led to a certain level of unintentional selection bias as such a small sample size, particularly when drawn from a specific region (Białystok, Poland), may not reflect the broader population of women with reproductive issues. As this is a cross-sectional study with no follow-up, its design makes it impossible to establish causality or account for changes over time, i.e., the study is susceptible to hypothetical/temporal bias. As the exploratory character of the study makes it particularly susceptible to data-dredging problems, the researchers made sure that only pre-planned analyses were performed. In this manner, the probability of establishing falsely positive associations was controlled.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., M.P., A.B., and R.M.; Methodology, M.S. and R.M.; Validation, R.M.; Formal analysis, M.S. and M.P.; Investigation, M.S. and R.M.; Resources, A.D., A.B., and R.M.; Writing—original draft, M.S. and M.P.; Writing—review & editing, M.S., M.P. and R.M.; Supervision, R.M.; Funding acquisition, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical University of Bialystok (APK.002.99.2023, approved on February 16, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

References

- M. Yuan , W. Li, Y. Zhu, B. Yu and J. Wu, "Asprosin: A Novel Player in Metabolic Diseases," Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), vol. 11, p. 64, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Romere, C. Duerrschmid, J. Bournat, P. Constable, M. Jain, F. Xia, P. K. Saha, M. Del Solar, B. Zhu, B. York, P. Sarkar, D. A. Rendon, M. W. Gaber, S. A. LeMaire, J. S. Coselli, D. M. Milewicz, V. R. Sutton, N. F. Butte, D. D. Moore and A. R. Chopra, "Asprosin, a Fasting-Induced Glucogenic Protein Hormone," Cell, vol. 165, no. 3, pp. 566-579, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Ulloque-Badaracco, A. Al-Kassab-Córdova, E. A. Hernandez-Bustamante, E. A. Alarcon-Braga, P. Robles-Valcarcel, M. A. Huayta-Cortez, J. C. Cabrera Guzmán, R. A. Seminario-Amez and V. Benites-Zapata, "Asprosin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis," Diabetes & metabolic syndrome, vol. 18, no. 7, p. 103095, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Vander Borght and C. Wyns, "Fertility and infertility: Definition and epidemiology," Clin Biochem, vol. 62, pp. 2-10, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liang, J. Huang, Q. Zhao, H. Mo, Z. Su, S. Feng, S. Li and X. Ruan, "Global, regional, and national prevalence and trends of infertility among individuals of reproductive age (15-49 years) from 1990 to 2021, with projections to 2040," Hum Reprod, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 529-544, 2025.

- J. Feng, Q. Wu, Y. Liang, Y. Liang and Q. Bin, "Epidemiological characteristics of infertility, 1990–2021, and 15-year forecasts: an analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2021," Reprod Health, vol. 22, no. 26, 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. L. G. Health, "Infertility-why the silence?," The Lancet. Global health, vol. 10, no. 6, p. e773, 2022.

- M. C. Inhorn and P. Patrizio, "Infertility around the globe: new thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century," Hum Reprod Update, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 411-426, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Alan, B. Gurlek, A. Yilmaz, M. Aksit, B. Aslanipour, I. Gulhan, C. Mechmet and C. E. Taner, "Asprosin: A novel peptide hormone related to insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.," Gynecol. Endocrinol., vol. 35, pp. 220-223, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Mascarenhas, S. R. Flaxman, T. Boerma, S. Vanderpoel and G. A. Stevens, "National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: a systematic analysis of 277 health surveys," PLoS Med, vol. 9, no. 12, p. e1001356, 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. Wei, A. Long and Y. Wang, "The Asprosin-OLFR734 hormonal signaling axis modulates male fertility," Cell Discov, vol. 5, no. 55, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Bialy, "Asprosin-A Fasting-Induced, Glucogenic, and Orexigenic Adipokine as a New Promising Player. Will It Be a New Factor in the Treatment of Obesity, Diabetes, or Infertility? A Review of the Literature," Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 620, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Broughton and K. H. Molley, "Obesity and female infertility: potential mediators of obesity’s impact," Fertility and Sterility, vol. 107, no. 4, pp. 840-847, 2017.

- N. Leonard, A. L. Shill, A. E. Thackaray, D. J. Stensel and N. C. Bishop, "Fasted plasma asprosin concentrations are associated with menstrual cycle phase, oral contraceptive use and training status in healthy women," Eur. J. Appl. Physiol., pp. 1-9, 2020.

- L. Chang, S. Y. Huang, Y. C. Hsu, T. H. Chin and Y. K. Soong, "The serum level of irisin, but not asprosin, is abnormal in polycystic ovary syndrome patients," Sci. Rep., vol. 9, p. 6447, 2019.

- M. Skowrońska, M. Pawłowski, A. Buczyńska , A. Wiatr, A. Dyszkiewicz, A. Wenta, K. Gryko , M. Zbucka-Krętowska and R. Milewski, "The Relationship Between Body Composition Parameters and the Intake of Selected Nutrients, and Serum Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) Levels in the Context of Ovulatory Infertility," Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 23, p. 4149, 2024.

- M. González-rodríguez , C. Ruiz-fernández, A. Cordero-barreal, D. Eldjoudi, J. Pino and Y. Farrag, "Adipokines as targets in musculoskeletal immune and inflammatory diseases," Drug Discovery Today, p. 103352, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Liang, X. Li, C. Xiang, M. Xu, Y. Ren, F. Zheng, L. Ma, J. Yang, Y. Wang and L. Xu, "The correlation between serum asprosin and type 2 diabetic patients with obesity in the community," Frontiers in endocrinology, vol. 16, p. 1535668, 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. W. Freeman, C. R. Gracia, M. D. Sammel, H. Lin, L. C. Lim and J. F. Strauss, "Association of anti-mullerian hormone levels with obesity in late reproductive-age women," Fertil Steril, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 101-106, 2007. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, M. Liao, R. Shen, L. Zhang , H. Hu, J. Wu, X. Wang, H. Qu , S. Guo and M. Long, "Plasma asprosin levels are associated with glucose metabolism, lipid, and sex hormone profiles in females with metabolic-related diseases.," Mediat. Inflamm, p. 7375294, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Ugur, F. Erman, S. Turkoglu, Y. Aydin, A. Aksoy, A. Lale, Z. K. Karagöz, I. Ugur, R. F. Akkoc and M. Yalniz, "Asprosin, visfatin and subfatin as new biomarkers of obesity and metabolic syndrome," European review for medical and pharmacological sciences, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 2124-2133, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Hebbar, M. Abu-Farha and A. Mohammad , "FTO Variant rs1421085 Associates With Increased Body Weight, Soft Lean Mass, and Total Body Water Through Interaction With Ghrelin and Apolipoproteins in Arab Population," Front Genet, vol. 10, p. 1411, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Shabir, J. E. Brown, I. Afzal, S. Gharanei, M. O. Weickert, T. M. Barber, I. Kyrou and H. S. Randeva, "Asprosin, a novel pleiotropic adipokine implicated in fasting and obesity-related cardio-metabolic disease: Comprehensive review of preclinical and clinical evidence," Cytokine & growth factor reviews, vol. 60, pp. 120-132, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Farrag, D. Ait Eldjoudi, M. González-Rodríguez, A. Cordero-Barreal, C. Ruiz-Fernández, M. Capuozzo, M. A. González-Gay, A. Mera, F. Lago, A. Soffar, A. Essawy, J. Pino, Y. Farrag and O. Gualillo, "Asprosin in health and disease, a new glucose sensor with central and peripheral metabolic effects," Frontiers in endocrinology, vol. 13, p. 1101091, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Summers, S. J. Bush, M. R. Davis, D. A. Hume, S. Keshvari and J. A. West, "Fibrillin-1 and asprosin, novel players in metabolic syndrome," Molecular genetics and metabolism, vol. 138, no. 1, p. 106979, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Duerrschmid , Y. He and C. Wang, "Asprosin is a centrally acting orexigenic hormone," Nat Med, vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 1444-1453, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Szamatowicz and J. Szamatowicz, "Proven and unproven methods for diagnosis and treatment of infertility," Adv Med Sci, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 93-96, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. R. S. Maylem, L. J. Spicer, I. Batalha and L. F. Schutz, "Discovery of a possible role of asprosin in ovarian follicular function," J. Mol. Endocrinol., vol. 66, pp. 25-34, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Bala, V. Singh, S. Rajender and K. Singh, "Environment, Lifestyle, and Female Infertility," Reprod Sci, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 617-638, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).