1. Introduction

Hydrogen is widely regarded as a promising energy carrier due to its high gravimetric energy density, environmental compatibility, and potential role in decarbonizing multiple sectors of the global energy system. However, its practical implementation is limited by the lack of storage technologies that simultaneously ensure safety, reversibility, and efficiency under ambient or near-ambient conditions. Conventional storage methods such as high-pressure compression and cryogenic liquefaction suffer from energy inefficiency, safety risks, and low volumetric densities. In contrast, material-based hydrogen storage—where hydrogen is stored via physisorption, chemisorption, or a combination of both—has emerged as a compelling alternative. For such systems to be practical, adsorption energies must typically fall within the range of −0.1 to −0.8 eV per H

2 molecule, striking a balance between sufficient binding strength and reversible release under operational conditions[

1,

2,

3]. Theoretical studies have shown that nanostructured materials—including metal-organic frameworks, functionalized carbon materials, and transition-metal-decorated systems—can meet these criteria by fine-tuning their surface electronic structure, pore architecture, and active site polarity[

4,

5,

6]. Within this landscape, atomically precise clusters offer several intrinsic advantages, including high surface-to-volume ratios, tunable reactivity, and well-defined sorption sites, positioning them as promising candidates for high-performance hydrogen storage applications.

Various silicon–lithium (Si–Li) clusters have been proposed for hydrogen storage, supported by computational predictions of high gravimetric capacities and adsorption energies compatible with reversible, non-dissociative adsorption[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Particular attention has focused on aromatic clusters combining enhanced stability with favorable interaction profiles. Si

5Li

6 (

C2v), studied by Jena et al. in 2006, was predicted to adsorb up to 14 H

2 molecules, though steric constraints limit effective uptake to around 10, with adsorption energies of 0.11–0.16 eV per H

2 range[

7]. Shortly thereafter, in 2012, Pan, Merino, and Chattaraj reported Si

5Li

7⁺ (

D5h) and Si

4Li

4 (

Td) as viable hydrogen hosts, capable of storing 10–12 H

2 molecules with gravimetric capacities of 15.25 wt% and 14.7 wt%, and adsorption energies in the 0.10–0.20 eV per H

2 range[

9]. Guo and Wang, in 2020, investigated SiLi

4⁺, composed of a central Si atom tetrahedrally coordinated by Li atoms, which adsorbs 12 H

2 molecules at 30.2 wt% and ~0.12 eV per H

2, with dynamic stability confirmed at 300 K via molecular dynamics simulations[

10]. All these clusters—Si

4Li

4, Si

5Li

6, Si

5Li

7+, and SiLi

4+—were confirmed as global minima (GM) through systematic potential energy surface (PES) exploration, reinforcing the reliability of their predicted properties[

10,

12,

13,

14]. In contrast, larger clusters such as Si

6Li

6 (D

2h) and Si

10Li

10 (C

s), proposed by Jaiswal and Sahu in 2022[

8]

, were constructed without global optimization. While they were predicted to adsorb 18 and 40 H

2 molecules, respectively, with gravimetric capacities of 14.7 wt% and 18.7%, and adsorption energies ranging from 0.059 to 0.141 eV per H

2, their thermodynamic relevance remains uncertain. Larger silicon-based assemblies have also been proposed, including Li-functionalized Si

20H

20 frameworks with lithium-containing organic groups (e.g., CN

2HLi, CONHLi), reported in 2015 to adsorb up to 60 H

2 molecules (12.5 wt%) [

15], and Li

12Si

60H

60, a 2009 silicon analog of a decorated fullerene, predicted to bind 30 H

2 molecules (7.46 wt%)[

11] . However, these extended systems have not undergone global optimization, leaving their stability and practical viability unverified.

Cluster-assembled materials (CAMs)[

16], constructed from discrete, atomically defined units that retain their structural and electronic identity upon aggregation, provide a robust framework for the modular design of functional nanomaterials[

17]. In the realm of Si–Li systems, our computational studies have shown that Li

4Si

4 (

Td) and Li

6Si

5 (

C2v)—both global minima—are promising building blocks stabilized by distinct forms of aromaticity. Li

4Si

4 exhibits spherical σ-aromaticity, while Li

6Si

5 features both σ- and π-aromatic delocalization. These clusters assemble into stable oligomers such as Li

8Si

8, Li

10Si

9, and Li

12Si

10, which preserve their local bonding environments and remain dynamically stable even at elevated temperatures[

12]. Notably, these systems' Si

44– and Si

56– motifs are also present in experimental Zintl phases such as Li

12Si

7, Li

8MgSi

6, and Li

21Si

5, supporting their chemical viability[

18,

19,

20,

21]. Among these assemblies, (Li

4Si

4)

n oligomers are particularly attractive for hydrogen storage due to their high density of surface-accessible Li⁺ centers, which offer multiple binding sites for physisorption.

This study examines a series of structurally diverse Si–Li clusters selected for their potential to enable hydrogen storage via polar Li⁺ adsorption centers, favorable charge distribution, and electronically stable, modular architectures. Although distinct in topology, all analyzed systems share a common underlying motivation: they are either based on aromatic Si–Li motifs or serve as computational models of CAMs with accessible surfaces for physisorption. Firstly, we revisit the Si₆Li₆ and Si₁₀Li₁₀ clusters, previously proposed as high-capacity sorbents due to their resemblance to benzene and naphthalene, respectively[

8]. While these structures suggest delocalized bonding frameworks, they were modeled without global optimization, and their thermodynamic viability remains unresolved. We, therefore, carry out a comprehensive exploration of their potential energy surfaces (PES) to locate the true global minima and reassess their hydrogen adsorption properties. In addition, we analyze the Li₁₂Si₅ (D₅h) cluster[

13], recently reported by our group as a global minimum sandwich-type system, built from a Si₅¹⁰⁻ ring flanked by two Li₆⁵⁺ units[

13]. This compact, highly polarizable structure features σ-aromatic delocalization and a high density of Li⁺ sites favorable for hydrogen binding. Finally, we investigate (Li₄Si₄)

n oligomers (n = 1–3), which model CAMs based on the Li₄Si₄ (

Td) global minimum and exhibit a large number of accessible Li⁺ adsorption sites. Together, these systems span a range of structural motifs and degrees of modularity, allowing us to examine the interplay between PES stability, electronic structure, and hydrogen uptake capacity in Si–Li nanocluster design.

2. Computational Details

The potential energy surfaces (PES) of the Li₆Si₆, Li₁₀Si₁₀, and (Li₄Si₄)n (n = 1–3) clusters were explored using the AUTOMATON program[

22], which combines a probabilistic automata-based framework with genetic algorithms, for the (Li₄Si₄)n oligomers, PES exploration was also carried out using the guided Kick-MEP method[

23]; full methodological details are provided in the Supporting Information. Initial structure screening for all systems was performed for singlet and triplet multiplicities at the PBE0[

24]/SDDALL[

25] level. Low-energy isomers within 20.0 kcal·mol⁻¹ of the putative global minimum were re-optimized at the PBE0-D3[

26]/def2-TZVP[

27] level. Harmonic vibrational frequency calculations confirmed that all reported minima are true stationary points. Final relative energies were obtained from single-point refinements at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)[

28]/CBS[

29] //PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP level, carried out using ORCA 5.0.3; only these values are considered in the energetic discussion. Geometry optimizations and frequency calculations were performed using Gaussian 16[

30]. All computational details and representative low-energy structures are included in the

Supporting Information (Sections S1–S3).

Hydrogen adsorption energetics were evaluated by computing adsorption energies (E

ads) for all nH₂–cluster complexes using the expression:

Here,

E(complex) is the total energy of the hydrogen–cluster complex,

nE(H₂) is the energy of

n isolated H₂ molecules, and

E(cluster) is the energy of the bare cluster. To improve accuracy, adsorption energies were corrected for basis set superposition error (BSSE)[

31] arising from artificial stabilization due to basis function overlap in weakly bound systems. Boys and Bernardi's counterpoise (CP) correction method was employed to account for BSSE[

32]. The CP-corrected interaction energy (

ECP) is given by:

Here, Eint is the uncorrected interaction energy, and EBSSE is the basis set superposition error correction. All cluster geometries and their hydrogenated analogues were optimized using Gaussian 16 at the M06[

33]/6-311+G(d,p)[

34] level, chosen for its proven accuracy in describing dispersion-driven interactions relevant to hydrogen storage[

8]. Practical storage capacity was estimated through gravimetric density calculations at approximate saturation using the expression:

Here, M(nH₂) is the total mass of the adsorbed hydrogen molecules, and M(cluster) is the molecular mass of the bare cluster.

Non-covalent interactions were analyzed using the Independent Gradient Model based on Hirshfeld partitioning (IGMH)[

35]. This method improves upon the original IGM method by using Hirshfeld-derived atomic densities, offering a more physically grounded and higher-resolution depiction of weak interactions. Compared to conventional NCI plots, IGMH provides more detailed insights into dispersion-driven adsorption. All analyses were performed at the M06/6-311+G(d,p) level using Multiwfn[

36], with visualizations rendered in VMD[

37].

To evaluate the structural resilience and reversibility of hydrogen adsorption under thermal conditions, Born–Oppenheimer molecular dynamics (BOMD)[

38] simulations were conducted at 300 K and 400 K, temperatures relevant to practical hydrogen storage. The ADMP method[

39], a Lagrangian formulation using Gaussian basis sets, was employed as a computationally efficient alternative to conventional BOMD, offering comparable accuracy for trajectory prediction. Simulations were run for 10 ps to assess structural stability and the dynamic retention of adsorbed hydrogen over time.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Confirming Li-Si Lowest Energy Structures

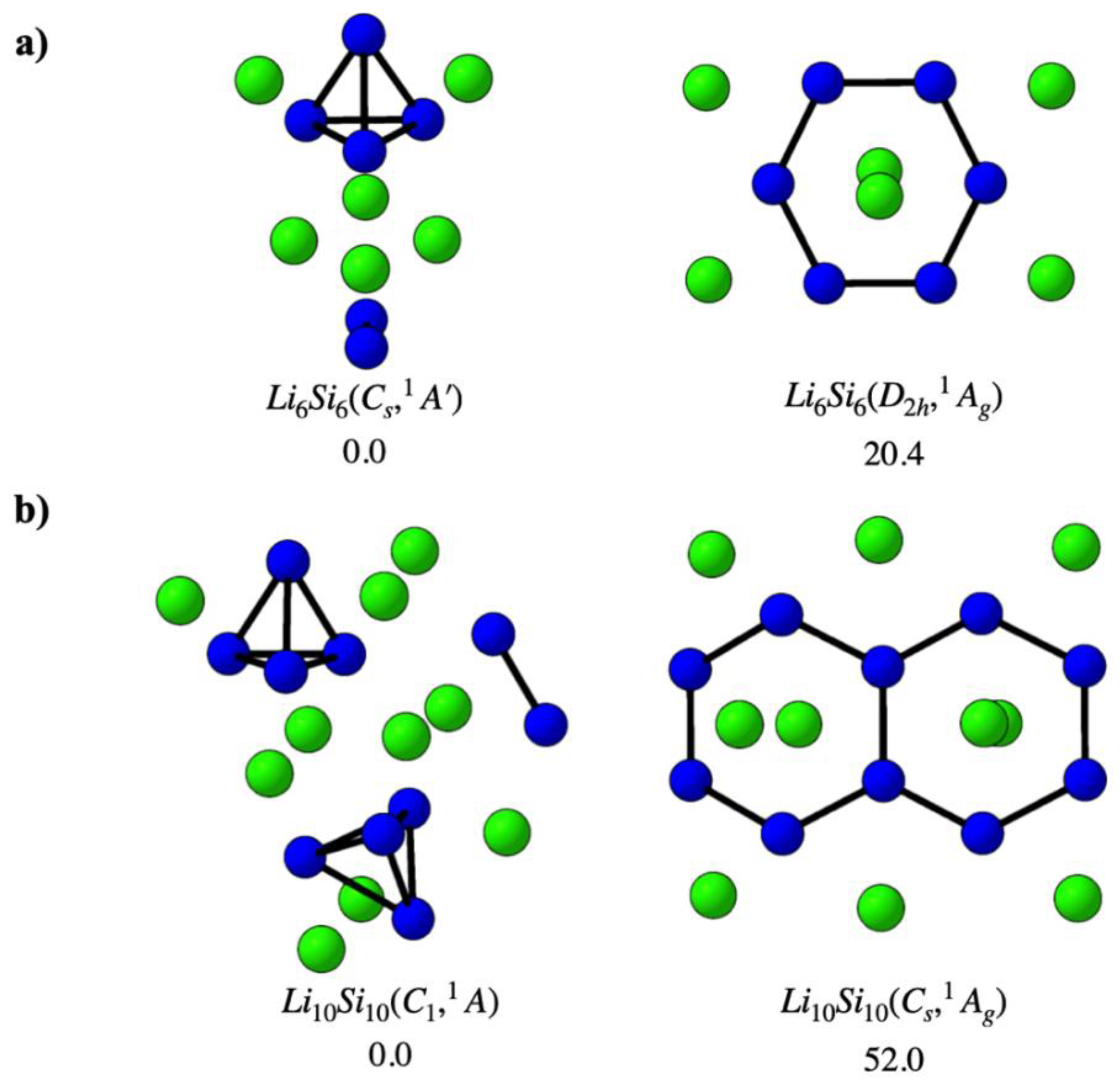

Figure 1 shows the global minima and the previously proposed high-symmetry structures for the Li

6Si

6 and Li

10Si

10 clusters[

8], as identified through comprehensive PES exploration. For Li

6Si

6 (panel a, left), the global minimum exhibits Cₛ symmetry (

¹A′ state) and is composed of a Si

4 tetrahedral unit (

Td) and a Si

2 dimer, surrounded by asymmetrically distributed Li atoms. This compact three-dimensional configuration is significantly more stable—by 20.4 kcal·mol⁻¹—than the previously proposed D

2h-symmetric structure (panel a, right), which features a planar Si

6 ring and had been modeled as a benzene analog in earlier hydrogen storage studies. For Li

10Si

10 (panel b), the global minimum adopts C₁ symmetry (

¹A′ state) and consists of two Si

4 tetrahedra and one Si–Si dimer, coordinated by a spatially dispersed set of lithium atoms. This low-symmetry arrangement lies 52.0 kcal·mol⁻¹ below the Cₛ-symmetric isomer (panel b, right), previously proposed as a naphthalene-like candidate for molecular hydrogen adsorption. These results indicate that the earlier high-symmetry, π-aromatic-like structures do not correspond to thermodynamically favored forms. Instead, the emergence of Si

4-based building units in both global minima highlight the stabilizing role of such substructures in lithium–silicon chemistry and supports their relevance for the design of hydrogen storage clusters. Additional low-energy isomers within 20 kcal·mol⁻¹ of the global minima are reported in

Figure S1-S2 (Supporting Information), further illustrating the structural diversity of these systems.

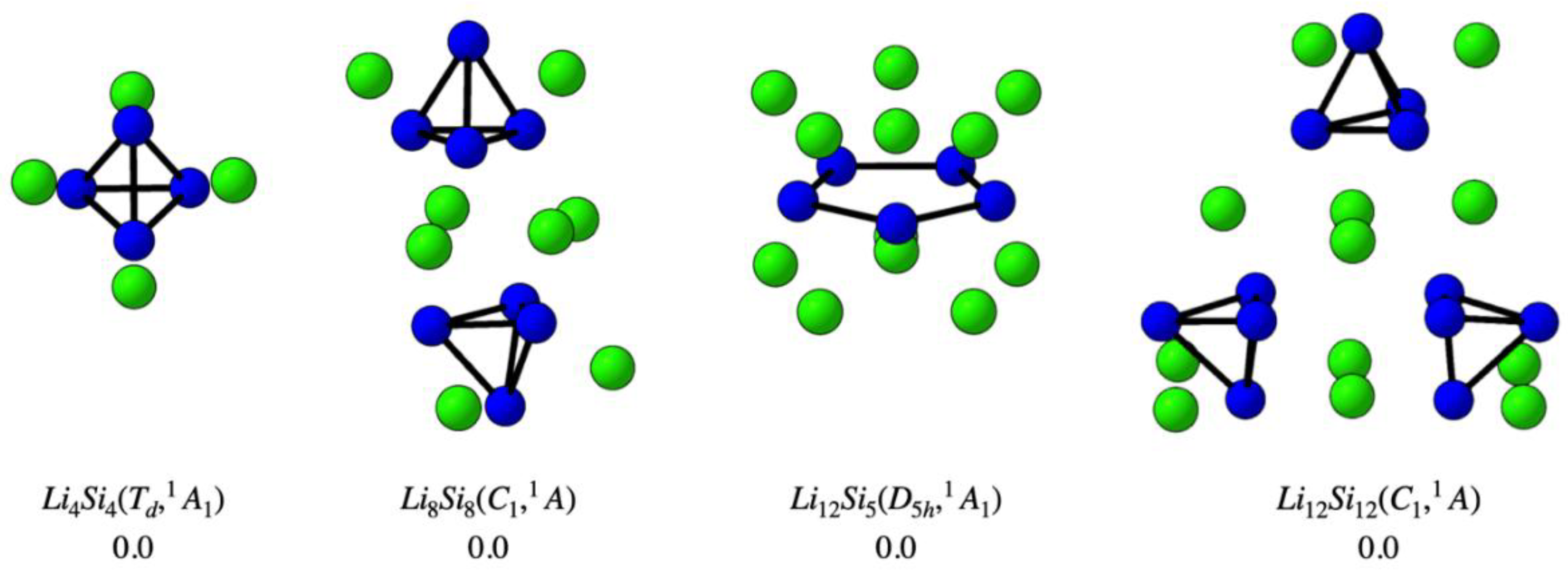

In parallel with our identification of new global minima, we re-evaluated the potential energy surfaces of two previously proposed systems—Li₁₂Si₅ (D₅h, ¹A₁) and the (Li₄Si₄)ₙ oligomers (n = 2–3)—reported initially as global minima and selected here for their relevance to hydrogen storage. Our independent PES analysis confirms that these structures correspond to ground-state configurations. As shown in

Figure 2, the Li

4Si

4 (

Td) monomer maintains its structural integrity upon oligomerization, with Li

8Si

8 and Li

12Si

12 preserving the local Si₄-based connectivity and Li⁺ coordination. The Li₁₂Si₅ cluster was likewise verified to occupy the lowest point on the potential energy surface. These results substantiate the thermodynamic stability of the selected clusters and support their role as structurally persistent, modular building units for hydrogen-rich Si–Li assemblies.

3.2. Structural and Electronic Features of Bare and Hydrogen-Adsorbed Si–Li Clusters

Table 1 depicts the computed interatomic distances for the Si–Li clusters examined in this study and their corresponding hydrogen-adsorbed complexes. Si–Si bond lengths remain largely invariant upon H₂ adsorption, spanning 2.12–2.57 Å, reflecting the structural integrity of the silicon frameworks. Si–Li distances in the bare clusters range from approximately 2.40 to 2.76 Å and undergo modest elongation upon hydrogenation, particularly in larger assemblies such as Li

8Si

8 and Li

12Si

5, where maximum distances approach ~2.89 Å. Li–H separations offer insight into adsorption, with the shortest distances (2.08–2.30 Å) corresponding to favorable electrostatic interactions with exposed Li⁺ centers. As hydrogen coverage increases, longer Li–H contacts—up to ~3.9 Å—are observed, indicating weaker physisorption at more peripheral or sterically hindered sites. This trend appears in both the global minimum (GM) structures identified through PES exploration and in the previously proposed high-symmetry local minima, Li

6Si

6* and Li

10Si

10*. While both structures support molecular hydrogen adsorption, the GM isomers generally present more spatially accessible and topologically diverse Li⁺ coordination, which can enhance adsorption site availability. In all cases, H–H bond distances remain close to 0.75 Å, consistent with nondissociative molecular adsorption. These structural characteristics underscore the relevance of using thermodynamically validated GM structures for accurately predicting hydrogen storage performance in Si–Li clusters.

Table 2 compiles the HOMO–LUMO energy gaps (ΔE

H–L) of the studied lithium–silicon clusters, both in their bare and hydrogen-adsorbed configurations. These values offer insight into electronic stability and chemical hardness. Among the bare clusters, Li

4Si

4 exhibits the highest gap (3.1 eV), which increases to 3.4 eV upon adsorption of 8 H

2 molecules and remains relatively high (3.2 eV) for 12 H

2, confirming its closed-shell character and resilience to electronic perturbation. The global minimum structures of Li

6Si

6 and Li

10Si

10 show gaps of 2.8 and 2.6 eV, respectively, which are also maintained or even slightly enhanced upon hydrogenation, reaching 2.9 eV for both 12H₂@Li

6Si

6 and 30H₂@Li

10Si

10. In contrast, the previously proposed high-symmetry structures—Li

6Si

6* (D

2h) and Li

10Si

10* (C

s)—exhibit narrower gaps of 2.2 eV and 1.8 eV, respectively, with negligible changes upon hydrogen loading. These values match closely with those reported by Jaiswal et al., who found ΔE

H–L values of 2.33 eV for Li₆Si₆ and 1.81 eV for Li₁₀Si₁₀ using the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory. Although method-dependent differences are expected, the trend is consistent: higher energy isomers on PES tend to display smaller HOMO–LUMO gaps and reduced electronic stability. Additional insights are observed in other systems. Li

8Si

8 displays an increase from 2.7 to 3.1 eV as H₂ adsorption progresses up to 16 molecules, followed by a decline to 2.1 eV at 24H

2, suggesting a saturation threshold for electronic stabilization. Li₁₂Si₁₂ maintains gaps above 2.6 eV, while Li

12Si

5, the most compact and polarizable structure, shows the lowest gaps (1.3–1.7 eV), which increase modestly with hydrogen coverage.

3.3. Hydrogen Adsorption Energetics, Charge Redistribution, and Storage Capacity

The hydrogen adsorption properties of the investigated lithium–silicon clusters were assessed through BSSE-corrected adsorption energies (E

ads), partial charges on Li centers, and gravimetric hydrogen capacities (wt%), as summarized in

Table 3. In all systems, Li atoms initially exhibit partial charges between +0.75 and +0.89, consistent with their role as electropositive adsorption sites. Upon hydrogen adsorption, these charges decrease progressively—reaching as low as +0.30 in Li

12Si

5—reflecting charge redistribution driven by weak donor-acceptor interactions. The BSSE-corrected Eads values lie within the optimal range for reversible hydrogen storage (−0.11 to −0.16 eV per H

2), with slightly stronger binding at low coverage. The difference from uncorrected values (~0.01–0.02 eV) confirms the weakly bound nature of the interactions and the importance of applying BSSE corrections for reliable energetic estimates. All PES-validated GM structures—Li

4Si

4, Li

6Si

6, Li

8Si

8, and Li

10Si

10—reach 14.72 wt% through adsorbing 12, 18, 24, and 30 H

2 molecules, respectively. These values align with the upper limit of approximately three H

2 molecules per Li⁺, as Pan, Merino, and Chattaraj proposed[

9]. Li

4Si

4, a symmetric and modular unit (

Td), and its oligomeric derivatives Li

8Si

8 and Li

12Si

12, maintain favorable adsorption behavior and extend capacity, with Li

12Si

12 reaching 14.72 wt% with 36 H

2. While the high-symmetry isomers of Li

6Si

6 (D

2h) and Li

10Si

10 (C

s) achieve comparable hydrogen uptake and adsorption energetics, they correspond to higher-energy local minima and show narrower Li charge distributions relative to the GMs. The Li₁₂Si₅ GM attains the highest capacity in the series (23.45 wt% with 34 H

2), enabled by its compact

D5h geometry, slightly stronger adsorption energies, and a broader Li charge range (+0.30 to +0.78), which reflects increased electrostatic heterogeneity across adsorption sites. For example,

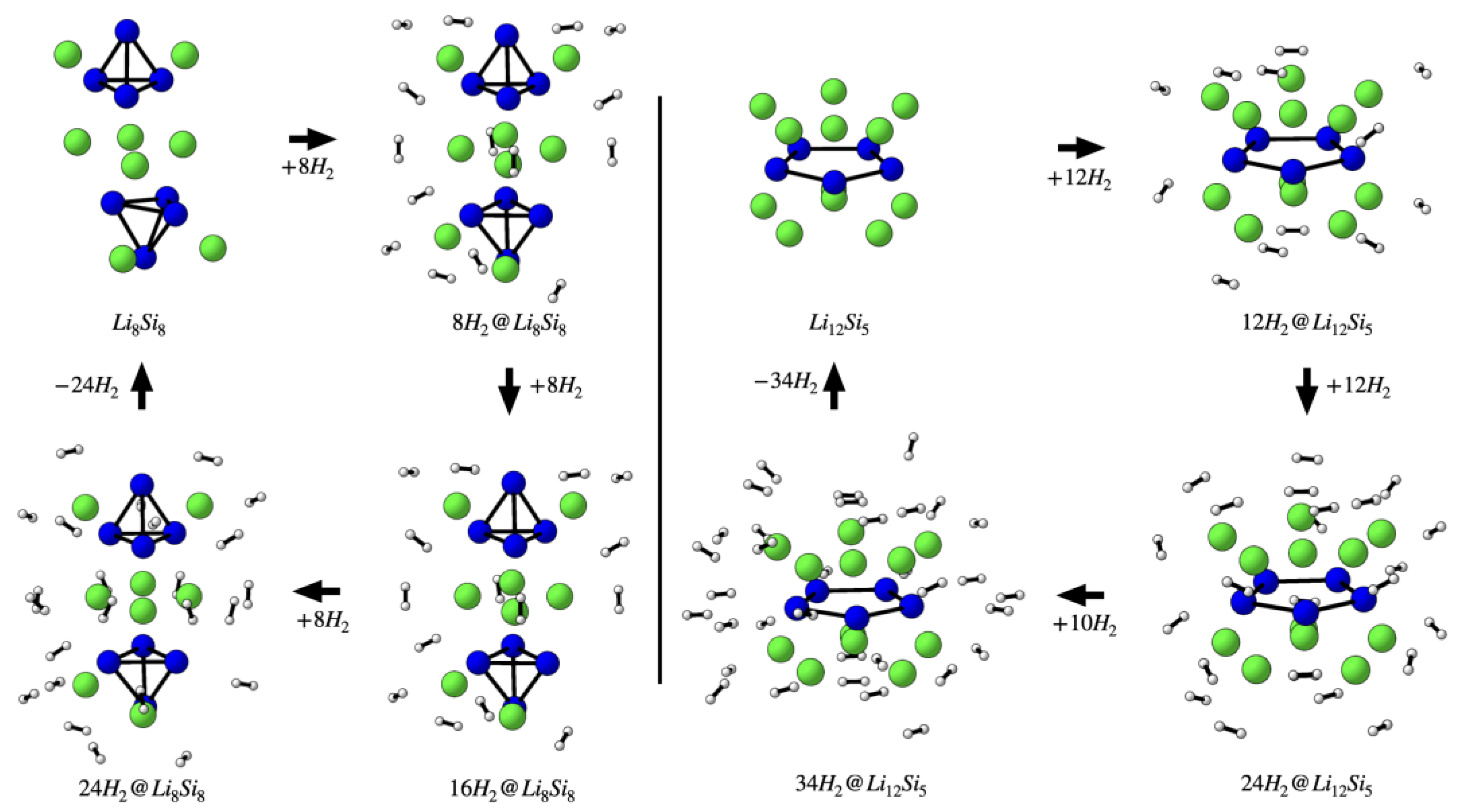

Figure 3 illustrates the stepwise hydrogen uptake over Li

8Si

8 and Li

12Si

5, showing progressive occupation of Li⁺ centers with minimal structural deformation. These results demonstrate that the Si–Li GMs studied here combine thermodynamic stability, favorable charge redistribution, and optimal adsorption energetics to enable efficient and reversible hydrogen storage.

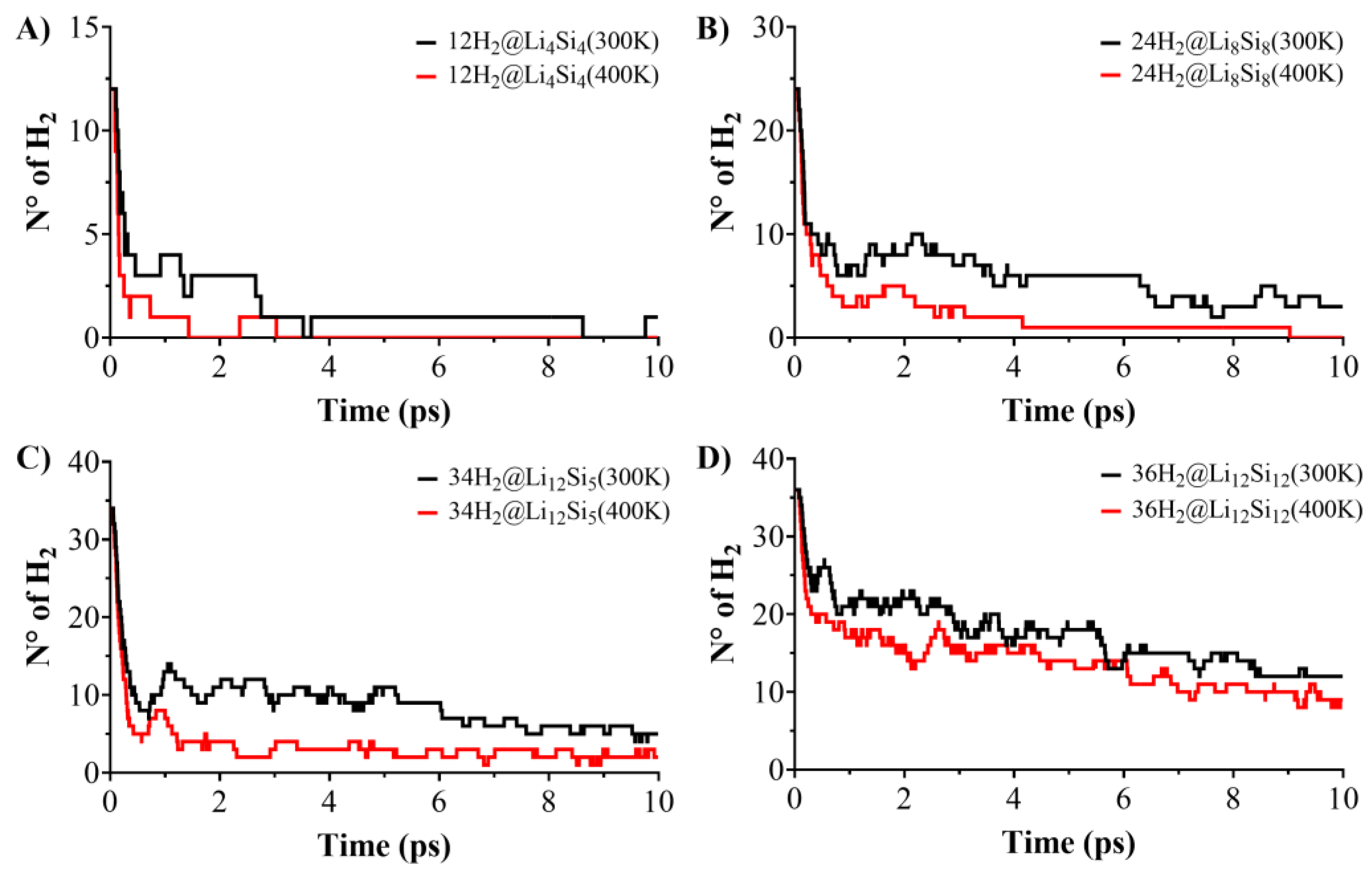

3.3. Thermal Stability and Hydrogen Release Dynamics via BOMD Simulations

The reversibility and thermal resilience of hydrogen adsorption were assessed through Born–Oppenheimer molecular dynamics (BOMD) simulations on hydrogen-loaded Si–Li clusters: 12H

2@Li

4Si

4, 18H

2@Li

6Si

6, 24H

2@Li

8Si

8, 30H

2@Li

10Si

10, 34H

2@Li

12Si

5, and 36H₂@Li₁₂Si₁₂. Simulations were conducted for 10 ps at 300 K and 400 K to probe hydrogen release under operating conditions. As shown in

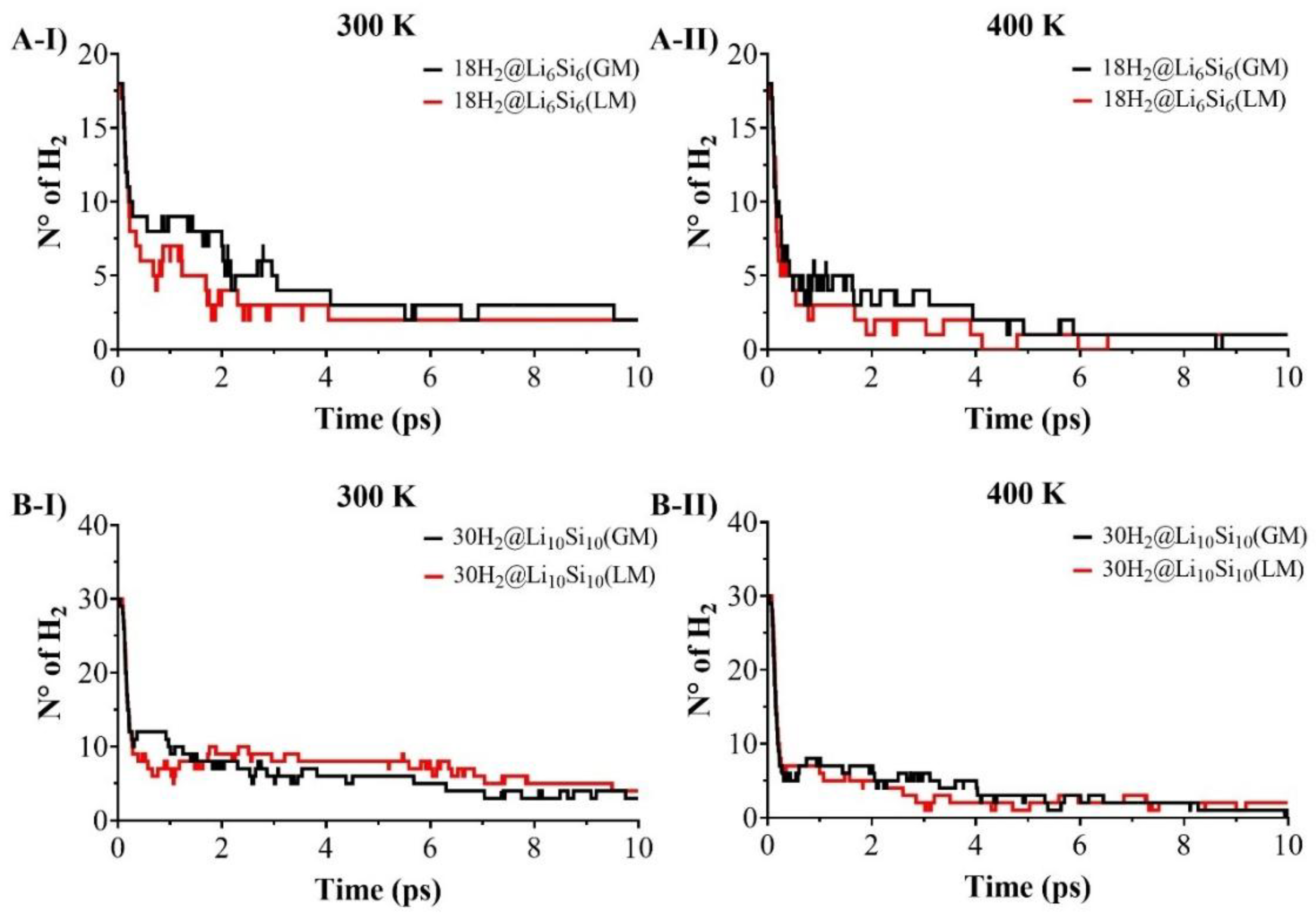

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, desorption behavior depends strongly on cluster size. At 300 K, smaller clusters such as Li

4Si

4 and Li

6Si

6 release the majority of their adsorbed hydrogen within the first few picoseconds, with only 1–2 H₂ molecules retained by the end of the simulation. In contrast, larger systems like Li

12Si

5 and Li

12Si

12 retain 6 and 12 H

2 molecules, respectively, under identical conditions. This size-dependent stability becomes even more pronounced at 400 K, where small clusters undergo complete or near-complete desorption, while Li

12Si

12 maintains nearly one-third of its original hydrogen load. These observations confirm that increasing cluster size and coordination density enhances hydrogen retention under elevated thermal conditions.

A comparative analysis between PES-validated global minima (GM) and previously reported local minima (LM) structures for Li

6Si

6 and Li

10Si

10 (

Figure 4) further underscores the role of structure optimization. While initial desorption rates are similar for GM and LM configurations, the GMs consistently retain more hydrogen at later times. For instance, at 400 K, 18H

2@Li

6Si

6(GM) retains ~2 H

2 molecules, whereas the LM counterpart undergoes full desorption. Similarly, 30H

2@Li

10Si

10(GM) retains ~4 H

2, while the LM form releases nearly all of its hydrogen content. These differences, though subtle in kinetics, reveal that GM structures offer more resilient binding sites capable of maintaining adsorbed hydrogen under thermal fluctuations. Altogether, the BOMD results support the conclusion that larger, PES-validated Si–Li clusters—particularly Li

10Si

10, Li

12Si

5, and Li

12Si

12—combine structural stability and dynamic retention, making them promising candidates for reversible hydrogen storage under realistic operating conditions.

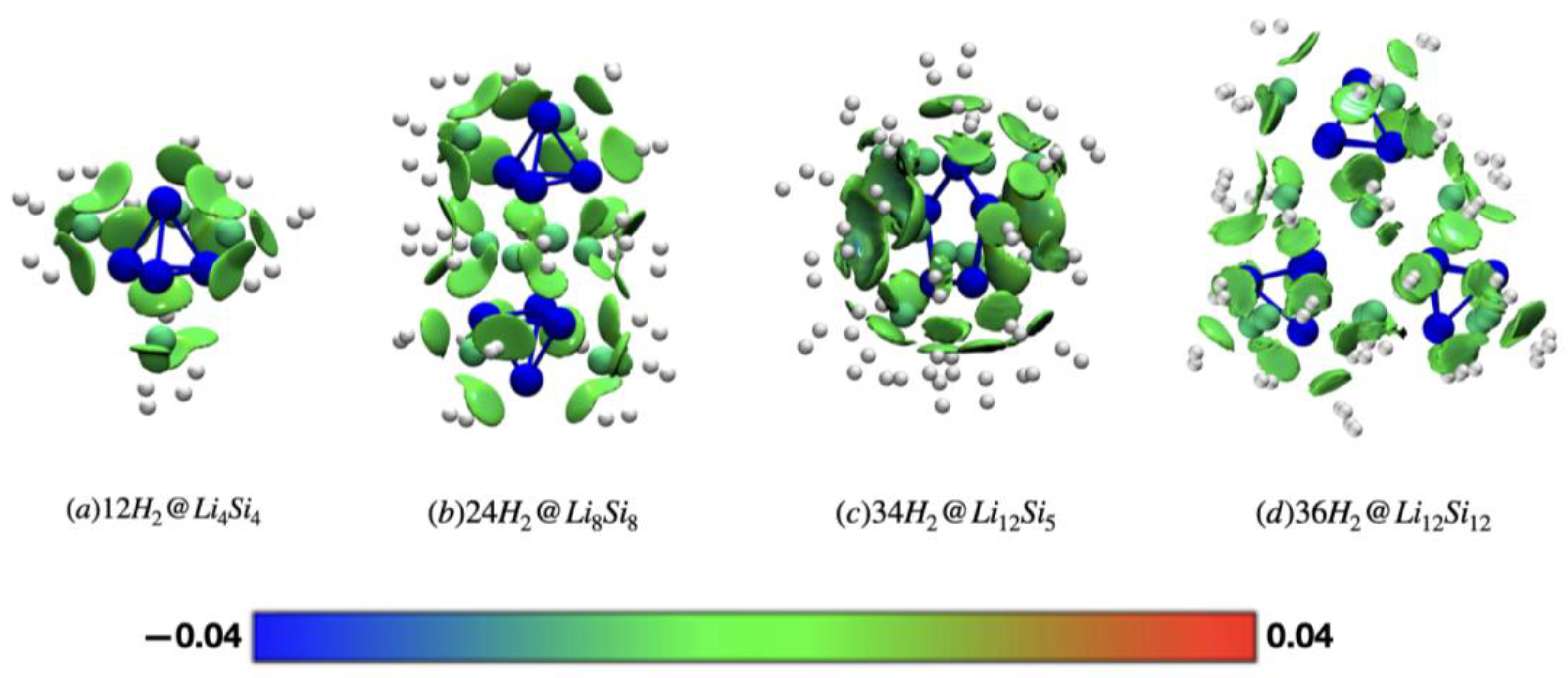

3.4. Visualization of Non-Covalent Interactions via IGMH Analysis

To gain visual insight into the nature of hydrogen adsorption in lithium–silicon clusters, we applied the Independent Gradient Model based on Hirshfeld partitioning (IGMH) to a series of representative hydrogenated systems (

Figure 6). As a qualitative method, IGMH enables high-resolution visualization of non-covalent interactions by partitioning electron density based on the actual molecular environment, offering superior clarity compared to traditional NCI plots—especially for dispersion-dominated systems. In all cases, the interactions between H₂ molecules and Li⁺ centers are characterized by green-colored isosurfaces located between the adsorbates and the cluster surface, confirming that physisorption is mediated primarily by weak van der Waals forces. No significant blue or red regions are observed, indicating the absence of strong electrostatic attractions or steric repulsion. The interaction fields are more extensive and homogeneously distributed in PES-validated structures such as 12H

2@Li

4Si

4, 24H

2@Li

8Si

8, and 34H

2@Li

12Si

5, reflecting their favorable electrostatic landscapes and high hydrogen uptake. In contrast, the local minima geometries of Li

6Si

6(D

2h) and Li

10Si

10(Cₛ) exhibit more fragmented interaction regions, correlating with reduced charge delocalization and lower retention in BOMD simulations. Overall, the IGMH results reinforce that dispersion-driven, non-dissociative physisorption governs hydrogen storage in these Si–Li clusters, complementing the energetic and dynamic analyses and validating their potential as reversible hydrogen carriers.

4. Conclusions

This study comprehensively investigates Si–Li clusters as hydrogen storage candidates, emphasizing the importance of accurate potential energy surface (PES) exploration. For the Li₆Si₆ and Li₁₀Si₁₀ systems, global optimization revealed that the true ground-state structures do not correspond to previously proposed benzene- and naphthalene-like motifs but rather consist of compact arrangements built from tetrahedral Si₄ (Td) units and a Si₂ dimer, all stabilized by surrounding lithium atoms. Specifically, Li₆Si₆ features a single Si₄ unit and a Si₂ bridge, while Li₁₀Si₁₀ includes two Si₄ units linked via a Si–Si dimer. These findings highlight the necessity of PES validation in cluster-based materials design, ensuring that the predicted structures are electronically stable and experimentally feasible.

Guided by the recurrence of the Si₄–Td motif, we evaluated oligomeric systems—dimers, trimers, and tetramers—of Li₄Si₄ as model cluster-assembled materials (CAMs). These oligomers preserve the local Si₄ environments and exhibit additive hydrogen storage behavior: each Li₄Si₄ unit binds 12 H₂ molecules (3 per Li⁺), with total storage capacities increasing proportionally with the number of monomers. Additionally, we explored the aromatic Li₁₂Si₅ sandwich cluster, which incorporates a planar Si₅ ring stabilized by two Li₆ caps. This system achieves the highest gravimetric capacity in the series (23.45 wt%), attributable to its high density of accessible Li⁺ sites. Collectively, our results establish clear structure–property relationships among Si–Li clusters and demonstrate the potential of PES-validated, modular architectures for designing thermally stable, high-capacity hydrogen storage materials.

Importantly, this work significantly advances the field of Li–Si clusters for hydrogen storage by delivering (i) a rigorous benchmark of global minimum structures for key systems previously proposed in the literature, (ii) new modular design principles based on Si₄–Td building blocks, and (iii) the identification of high-performing sandwich-type and oligomeric clusters with verified thermodynamic and dynamic stability. These contributions provide a robust theoretical foundation for guiding future experimental development of silicon–lithium nanomaterials in next-generation hydrogen storage technologies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1-S3: Putative global minimum and low-lying isomers of Li6Si6, Li10Si10 and Li12Si12,Figure S4: H2 adsorption configurations,Table S1: T1 diagnostics,Table S2: basis set superposition error,Table S3: Cartesian coordinates of the Li4Si4 , Li8Si8 ,Li6Si6, Li10Si10 and Li12Si12 optimized structures at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.T., L.L-P., W.G-A., and O.Y.; methodology, W.G-A., E.M., D.I., and O.Y.; software, W.G-A., D.I., E.M., and O.Y.; validation, W.G-A., L.L-P., and O.Y.; formal analysis, W.G-A., L.L-P., L.R., and D.I.; investigation, W.T., L.L-P., W.G-A., O.Y., E.M., D.I., J.S-E., L.R., and A.V-E.; resources, W.T., L.L-P., L.R., D.I., J.S-E., and A.V-E.; data curation, W.G-A., D.I., and O.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, W.G-A., L.R., L.L-P., O.Y. and W.T.; writing—review and editing, W.G-A., L.R., O.Y., W.T., L.L-P., E.M., D.I., J.S-E., and A.V-E.; visualization, W.G-A., L.R., and O.Y.; supervision, W.T., L.L-P., L.R., and O.Y.; project administration, W.T., L.L-P., L.R., and O.Y.; funding acquisition, W.T., L.L-P., L.R., and A.V-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the financial support of the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID) through FONDECYT project 1241066 (W. T.), FONDECYT project 1251871 (O. Y.) and FONDECYT project 1221019 (A. V.). Powered@NLHPC: This research was partially supported by the supercomputing infrastructure of the NLHPC (CCSS210001).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jana, G.; Chattaraj, P. K. , Exploring advanced nanostructures and functional materials for efficient hydrogen storage: a theoretical investigation on mechanisms, adsorption process, and future directions. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse L., C. Rowsell, O. M. Y. P. D., Strategies for Hydrogen Storage in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. 2005, 44(30), 4670–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yildirim, T. , Nature and Tunability of Enhanced Hydrogen Binding in Metal−Organic Frameworks with Exposed Transition Metal Sites. J. Phys. Chem. C.. 2008, 112(22), 8132–8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cychosz, K.A.; Matzger, A.J. Water Stability of Microporous Coordination Polymers and the Adsorption of Pharmaceuticals from Water. Langmuir 2010, 26(22), 17198–17202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, D.; Lai, C.; Zeng, G.; Qin, L.; Wang, H.; Yi, H.; Li, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, M.; Deng, R.; Fu, Y.; Li, L.; Xue, W.; Chen, S. , Recent advances in covalent organic frameworks (COFs) as a smart sensing material. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48(20), 5266–5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klontzas, E.; Mavrandonakis, A.; Tylianakis, E.; Froudakis, G. E. Improving Hydrogen Storage Capacity of MOF by Functionalization of the Organic Linker with Lithium Atoms. Nano Lett. 2008, 8(6), 1572–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, N. K.; Srinivasu, K.; Ghosh, S. K. Computational investigation of hydrogen adsorption in silicon-lithium binary clusters#. J. Chem. Sci. 2012, 124(1), 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Sahoo, R. K.; Ray, S. S.; Sahu, S. , Alkali metals decorated silicon clusters (SiM, n = 6, 10; M = Li, Na) as potential hydrogen storage materials: A DFT study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2022, 47(3), 1775–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Merino, G.; Chattaraj, P. K. , The hydrogen trapping potential of some Li-doped star-like clusters and super-alkali systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14(29), 10345–10350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wang, C. , Li center clusters MLi4+ (M = C, Si, Ge) for dihydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2020, 45(46), 24968–24979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Cao, D.; Wang, W. Li12Si60H60 Fullerene Composite: A Promising Hydrogen Storage Medium. ACS Nano 2009, 3(10), 3294–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M.F.Manrique-de-la-Cuba; L.Leyva-Parra; D.Inostroza; B.Gomez; A.Vásquez-Espinal; J.Garza; O.Yañez; W.Tiznado, Li8Si8, Li10Si9, and Li12Si10: Assemblies of Lithium-Silicon Aromatic Units. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22(10), 906–910. [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, D.; Leyva-Parra, L.; Pino-Rios, R.; Solar-Encinas, J.; Vásquez-Espinal, A.; Pan, S.; Merino, G.; Yañez, O.; Tiznado, W. Li6E5Li6: Tetrel Sandwich Complexes with 10-π-Electrons. Angew. Chem. 2024, 136(5), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O.Yañez; V.Garcia; J.Garza; W.Orellana; A.Vásquez-Espinal; W.Tiznado, (Li6Si5)2–5: The Smallest Cluster-Assembled Materials Based on Aromatic Si56− Rings. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 25(10), 2467–2471. [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zhang, C.; He, P. Si 20 H 20 cluster modified by small organic molecules and lithium atoms for high-capacity hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2015, 40(25), 8093–8105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S. N.; Jena, P. Assembling crystals from clusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 69(11), 1664–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P.Jena; Q.Sun, Super Atomic Clusters: Design Rules and Potential for Building Blocks of Materials. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118(11), 5755–5870. [CrossRef]

- Nesper, R.; Curda, J.; Von Schnering, H. G. Li8MgSi6, a novel Zintl compound containing quasi-aromatic Si5 rings. J. Solid State Chem. 1986, 62(2), 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, A.; Sreeraj, P.; Pöttgen, R.; Wiemhöfer, H. D.; Wilkening, M.; Heitjans, P. Li NMR Spectroscopy on Crystalline Li12Si7: Experimental Evidence for the Aromaticity of the Planar Cyclopentadienyl-Analogous Si56- Rings. Angew. Chem. 2011, 50(50), 12099–12102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, T. K. J.; Salager, E.; Morris, A. J.; Key, B.; Seznec, V.; Morcrette, M.; Pickard, C. J.; Grey, C. P. , Resolving the Different Silicon Clusters in Li12Si7 by 29Si and 6,7Li Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. 2011, 50(52), 12591–12594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, A.; Chen, Z.; Jiao, H. , Spherical Aromaticity of Inorganic Cage Molecules. Angew. Chem. 2001, 40(15), 2834–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez, O.; Báez-Grez, R.; Inostroza, D.; Rabanal-León, W. A.; Pino-Rios, R.; Garza, J.; Tiznado, W. AUTOMATON: A Program That Combines a Probabilistic Cellular Automata and a Genetic Algorithm for Global Minimum Search of Clusters and Molecules. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2019, 15(2), 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Argote, W.; Ruiz, L.; Inostroza, D.; Cardenas, C.; Yañez, O.; Tiznado, W. Introducing KICK-MEP: exploring potential energy surfaces in systems with significant non-covalent interactions. J. Mol. Model. 2024, 30(11), 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. , Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110(13), 6158–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P.Fuentealba; L.Von-Szentpaly; H.Preuss; H.Stoll, Pseudopotential calculations for alkaline-earth atoms. J. Phys. B: Atom. Mol. Phys. 1985, 18(7), 1287–1296. [CrossRef]

- S.Grimme; A.Jens; S.Ehrlich; H.Krieg, A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132(15), 154104–154119. [CrossRef]

- F.Weigend; R.Ahlrichs, Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7(18), 3297–3305. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purvis, G. D.; Bartlett, R. J. , A full coupled-cluster singles and doubles model: The inclusion of disconnected triples. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 76(4), 1910–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truhlar, D.G. Basis-set extrapolation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 294(1-3), 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. J. Frisch, G. W. T., H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, G. Scalmani, V. Barone, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, X. Li, M. Caricato, A. V. Marenich, J. Bloino, B. G. Janesko, R. Gomperts, B. Mennucci, H. P. Hratchian, J. V. Ortiz, A. F. Izmaylov, J. L. Sonnenberg, D. Williams-Young, F. Ding, F. Lipparini, F. Egidi, J. Goings, B. Peng, A. Petrone, T. Henderson, D. Ranasinghe, V. G. Zakrzewski, J. Gao, N. Rega, G. Zheng, W. Liang, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, T. Vreven, K. Throssell, J. A. Montgomery, Jr., J. E. Peralta, F. Ogliaro, M. J.; Bearpark, J. J. H., E. N. Brothers, K. N. Kudin, V. N. Staroverov, T. A. Keith, R. Kobayashi, J. Normand, K. Raghavachari, A. P. Rendell, J. C. Burant, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, M. Cossi, J. M. Millam, M. Klene, C. Adamo, R. Cammi, J. W. Ochterski, R. L. Martin, K. Morokuma, O. Farkas, J. B. Foresman and D. J. Fox Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01, B.01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

- I. Mayer, P. R. S. Improved intermolecular SCF theory and the BSSE problem. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1989, 36(3), 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, S. F.; Bernardi, F. The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19(4), 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other function. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120(1-3), 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehre, W. J. Ab initio molecular orbital theory. Acc. Chem. Res. 1976, 9(11), 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, Q. , Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: A new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 43(8), 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T.Lu; F.Chen, Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput.Chem. 2012, 33(5), 580–592. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. , VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14(1), 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J.M.Millam; V.Bakken; W.Chen; W.L.Hase; H.B.Schlegel, Ab initio classical trajectories on the Born–Oppenheimer surface: Hessian-based integrators using fifth-order polynomial and rational function fits. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 111, 3800–3805. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S. S.; Schlegel, H. B.; Voth, G. A. Atom-Centered Density Matrix Propagation (ADMP): Generalizations Using Bohmian Mechanics. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003, 107(37), 7269–7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Global minima and previously proposed high-symmetry structures for (a) Li6Si6 and (b) Li10Si10 clusters. Relative energies are given in kcal·mol⁻¹, computed at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP//PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory.

Figure 1.

Global minima and previously proposed high-symmetry structures for (a) Li6Si6 and (b) Li10Si10 clusters. Relative energies are given in kcal·mol⁻¹, computed at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP//PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory.

Figure 2.

Optimized structures of global minima for the clusters Li4Si4, Li8Si8, Li12Si5, and Li12Si12, as confirmed in this work through potential energy surface (PES) exploration. All relative energies (in kcal·mol⁻¹) were computed at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory.

Figure 2.

Optimized structures of global minima for the clusters Li4Si4, Li8Si8, Li12Si5, and Li12Si12, as confirmed in this work through potential energy surface (PES) exploration. All relative energies (in kcal·mol⁻¹) were computed at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory.

Figure 3.

Sequential adsorption of H2 molecules over Li8Si8 and Li12Si5 clusters.

Figure 3.

Sequential adsorption of H2 molecules over Li8Si8 and Li12Si5 clusters.

Figure 4.

Hydrogen desorption dynamics of 18H2@Li6Si6 and 30H2@Li10Si10 clusters. Snapshots are shown after 10 ps of BOMD simulation at 300 K (A-I and B-I) and 400 K (A-II and B-II) for both global minimum (GM) and local minimum (LM, marked with *) structures. The LM configurations correspond to the geometries reported by Jaiswal et al.

Figure 4.

Hydrogen desorption dynamics of 18H2@Li6Si6 and 30H2@Li10Si10 clusters. Snapshots are shown after 10 ps of BOMD simulation at 300 K (A-I and B-I) and 400 K (A-II and B-II) for both global minimum (GM) and local minimum (LM, marked with *) structures. The LM configurations correspond to the geometries reported by Jaiswal et al.

Figure 5.

Hydrogen desorption profiles of selected H₂-loaded Li–Si clusters following 10 ps of BOMD simulation at 300 K and 400 K. Shown are final geometries for: (A) 12H2@Li4Si4, (C) 24H2@Li8Si8, (D) 34H2@Li12Si5, and (E) 36H2@Li12Si12. .

Figure 5.

Hydrogen desorption profiles of selected H₂-loaded Li–Si clusters following 10 ps of BOMD simulation at 300 K and 400 K. Shown are final geometries for: (A) 12H2@Li4Si4, (C) 24H2@Li8Si8, (D) 34H2@Li12Si5, and (E) 36H2@Li12Si12. .

Figure 6.

IGMH isosurfaces (δginter = 0.003 a.u.) for hydrogenated Li–Si clusters: (a) 12H2@Li4Si4, (b) 24H2@Li8Si8 (c) 34H2@Li12Si5, and (d) 36H2@Li12Si12. Calculations were performed at the M06/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory. Blue indicates attractive interactions, green represents weak or dispersive interactions, and red denotes repulsive regions. *Local minima reported by Jaiswal et al.

Figure 6.

IGMH isosurfaces (δginter = 0.003 a.u.) for hydrogenated Li–Si clusters: (a) 12H2@Li4Si4, (b) 24H2@Li8Si8 (c) 34H2@Li12Si5, and (d) 36H2@Li12Si12. Calculations were performed at the M06/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory. Blue indicates attractive interactions, green represents weak or dispersive interactions, and red denotes repulsive regions. *Local minima reported by Jaiswal et al.

Table 1.

Computed bond distances (in Å) for Si–Si, Si–Li, Li–H, and H–H interactions in bare Si–Li clusters and their hydrogen-adsorbed complexes, calculated at the M06/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory.

Table 1.

Computed bond distances (in Å) for Si–Si, Si–Li, Li–H, and H–H interactions in bare Si–Li clusters and their hydrogen-adsorbed complexes, calculated at the M06/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory.

| System |

(Å) |

(Å) |

(Å) |

(Å) |

| H2 |

- |

- |

- |

0.74 |

| Li4Si4 |

2.44 |

2.51 |

- |

- |

| 4H2@Li4Si4 |

2.44 |

2.51-2.53 |

2.10 |

0.75 |

| 8H2@Li4Si4 |

2.44 |

2.52-2.53 |

2.12 |

0.75 |

| 12H2@Li4Si4 |

2.44 |

2.54-2.55 |

2.15-2.18 |

0.75 |

| Li6Si6 (*) |

2.31-2.36 |

2.40-2.76 |

- |

- |

| 6H2@Li6Si6 |

2.31-2.35 |

2.41-2.76 |

2.09-2.16 |

0.75 |

| 12H2@Li6Si6 |

2.31-2.34 |

2.42-2.73 |

2.08-3.58 |

0.75 |

| 18H2@Li6Si6 |

2.31-2.34 |

2.42-2.75 |

2.09-3.47 |

0.75 |

| Li6Si6 |

2.12-2.49 |

2.52-2.68 |

- |

- |

| 6H2@Li6Si6 |

2.12-2.48 |

2.50-2.69 |

2.10-2.20 |

0.75 |

| 12H2@Li6Si6 |

2.12-2.47 |

2.50-2.71 |

2.11-2.42 |

0.75 |

| 18H2@Li6Si6 |

2.12-2.48 |

2.52-2.73 |

2.14-3.41 |

0.75 |

| Li8Si8 |

2.35-2.54 |

2.44-2.89 |

- |

- |

| 8H2@Li8Si8 |

2.36-2.52 |

2.47-2.73 |

2.09-2.26 |

0.75 |

| 16H2@Li8Si8 |

2.36-2.51 |

2.50-2.72 |

2.12-2.29 |

0.75 |

| 24H2@Li8Si8 |

2.36-2.51 |

2.49-2.71 |

2.14-3.46 |

0.75 |

| Li10Si10 (*) |

2.26-2.47 |

2.42-3.35 |

- |

- |

| 10H2@Li10Si10 |

2.26-2.47 |

2.42-3.23 |

2.09-2.22 |

0.75 |

| 20H2@Li10Si10 |

2.27-2.43 |

2.46-3.14 |

2.09-3.72 |

0.75 |

| 30H2@Li10Si10 |

2.27-2.43 |

2.44-3.21 |

2.08-3.78 |

0.75 |

| Li10Si10 |

2.13-2.53 |

2.47-2.85 |

- |

- |

| 10H2@Li10Si10 |

2.13-2.52 |

2.46-2.94 |

2.09-2.25 |

0.75 |

| 20H2@Li10Si10 |

2.13-2.51 |

2.49-2.85 |

2.12-3.55 |

0.75 |

| 30H2@Li10Si10 |

2.13-2.50 |

2.51-2.85 |

2.13-3.90 |

0.75 |

| Li12Si5 |

2.57 |

2.51-2.56 |

- |

- |

| 12H2@ Li12Si5 |

2.46-2.57 |

2.49-2.59 |

1.93-2.17 |

0.75 |

| 22H2@ Li12Si5 |

2.46-2.56 |

2.50-2.58 |

1.91-3.65 |

0.75 |

| 24H2@ Li12Si5 |

2.44-2.56 |

2.50-2.60 |

2.13-3.81 |

0.75 |

| 32H2@ Li12Si5 |

2.45-2.56 |

2.50-2.59 |

1.94-3.76 |

0.75 |

| 34H2@ Li12Si5 |

2.46-2.55 |

2.50-2.60 |

2.00-3.50 |

0.75 |

| Li12Si12 |

2.39-2.52 |

2.47-2.71 |

- |

- |

| 12H2@Li12Si12 |

2.38-2.48 |

2.47-2.72 |

2.10-2.30 |

0.75 |

| 24H2@Li12Si12 |

2.37-2.52 |

2.47-2.67 |

2.11-3.20 |

0.75 |

| 36H2@Li12Si12 |

2.36-2.52 |

2.49-2.67 |

2.13-3.47 |

0.75 |

Table 2.

HOMO–LUMO energy gaps (ΔEH–L, in eV) for the bare and hydrogen-adsorbed lithium–silicon clusters, calculated at the M06/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory.

Table 2.

HOMO–LUMO energy gaps (ΔEH–L, in eV) for the bare and hydrogen-adsorbed lithium–silicon clusters, calculated at the M06/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory.

| System |

EHOMO

|

ELUMO

|

ΔEH-L

|

| Li4Si4 |

−4.4 |

−1.3 |

3.1 |

| 4H2@Li4Si4 |

−4.3 |

−1.0 |

3.3 |

| 8H2@Li4Si4 |

−4.3 |

−0.9 |

3.4 |

| 12H2@Li4Si4 |

−4.2 |

−1.0 |

3.2 |

| Li6Si6 (*) |

−3.6 |

−1.4 |

2.2 |

| 6H2@Li6Si6 |

−3.6 |

−1.4 |

2.2 |

| 12H2@Li6Si6 |

−3.5 |

−1.2 |

2.3 |

| 18H2@Li6Si6 |

−3.6 |

−1.3 |

2.3 |

| Li6Si6 |

−4.6 |

−1.8 |

2.8 |

| 6H2@Li6Si6 |

−4.5 |

−1.6 |

2.9 |

| 12H2@Li6Si6 |

−4.4 |

−1.5 |

2.9 |

| 18H2@Li6Si6 |

−4.6 |

−1.8 |

2.8 |

| Li8Si8 |

−4.4 |

−1.7 |

2.7 |

| 8H2@Li8Si8 |

−4.4 |

−1.3 |

3.1 |

| 16H2@Li8Si8 |

−4.3 |

−1.2 |

3.1 |

| 24H2@Li8Si8 |

−3.4 |

−1.3 |

2.1 |

| Li10Si10 (*) |

−3.3 |

−1.5 |

1.8 |

| 10H2@Li10Si10 |

−3.2 |

−1.4 |

1.8 |

| 20H2@Li10Si10 |

−3.2 |

−1.4 |

1.8 |

| 30H2@Li10Si10 |

−3.2 |

−1.4 |

1.8 |

| Li10Si10 |

−4.3 |

−1.7 |

2.6 |

| 10H2@Li10Si10 |

−4.2 |

−1.9 |

2.2 |

| 20H2@Li10Si10 |

−4.1 |

−1.2 |

2.9 |

| 30H2@Li10Si10 |

−4.1 |

−1.2 |

2.9 |

| Li12Si5 |

−3.0 |

−1.7 |

1.3 |

| 12H2@ Li12Si5 |

−2.8 |

−1.2 |

1.6 |

| 22H2@ Li12Si5 |

−2.7 |

−1.1 |

1.6 |

| 24H2@ Li12Si5 |

−2.7 |

−1.1 |

1.6 |

| 32H2@ Li12Si5 |

−2.8 |

−1.1 |

1.7 |

| 34H2@ Li12Si5 |

−2.9 |

−1.2 |

1.7 |

| Li12Si12 |

−4.0 |

−1.6 |

2.4 |

| 12H2@Li12Si12 |

−3.9 |

−1.3 |

2.6 |

| 24H2@Li12Si12 |

−3.9 |

−1.3 |

2,6 |

| 36H2@Li12Si12 |

−3.9 |

−1.3 |

2.6 |

Table 3.

Partial atomic charges on lithium centers (qLi), adsorption energies without (Eads) and with BSSE correction (Eads+BSSE) for hydrogen-adsorbed Li–Si clusters, computed at the M06/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory.

Table 3.

Partial atomic charges on lithium centers (qLi), adsorption energies without (Eads) and with BSSE correction (Eads+BSSE) for hydrogen-adsorbed Li–Si clusters, computed at the M06/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory.

| System |

q(Li) |

(eV) |

(eV) |

|

| Li4Si4 |

0.86 |

- |

- |

- |

| 4H2@Li4Si4 |

0.84 |

−0.12 |

−0.12 |

5.44 |

| 8H2@Li4Si4 |

0.82 |

−0.12 |

−0.12 |

10.32 |

| 12H2@Li4Si4 |

0.81 |

−0.11 |

−0.12 |

14.72 |

| Li6Si6 (*) |

0.83-0.84 |

- |

- |

- |

| 6H2@Li6Si6 |

0.81-0.85 |

-0.13 |

−0.14 |

5.44 |

| 12H2@Li6Si6 |

0.81-0.82 |

-0.13 |

−0.13 |

10.30 |

| 18H2@Li6Si6 |

0.82-0.83 |

-0.11 |

−0.11 |

14.72 |

| Li6Si6 |

0.70-0.87 |

- |

- |

- |

| 6H2@Li6Si6 |

0.70-0.84 |

−0.12 |

−0.13 |

5.44 |

| 12H2@Li6Si6 |

0.72-0.82 |

−0.11 |

−0.12 |

10.30 |

| 18H2@Li6Si6 |

0.72-0.81 |

−0.10 |

−0.11 |

14.72 |

| Li8Si8 |

0.71-0.88 |

- |

- |

- |

| 8H2@Li8Si8 |

0.72-0.85 |

−0.12 |

−0.13 |

5.44 |

| 16H2@Li8Si8 |

0.73-0.81 |

−0.11 |

−0.12 |

10.32 |

| 24H2@Li8Si8 |

0.77-0.81 |

−0.10 |

−0.11 |

14.72 |

| Li10Si10 (*) |

0.74-0.87 |

- |

- |

- |

| 10H2@Li10Si10 |

0.75-0.85 |

−0.14 |

−0.14 |

5.44 |

| 20H2@Li10Si10 |

0.75-0.83 |

−0.13 |

−0.13 |

10.32 |

| 30H2@Li10Si10 |

0.76-0.83 |

−0.11 |

−0.12 |

14.72 |

| Li10Si10 |

0.71-0.89 |

- |

- |

- |

| 10H2@Li10Si10 |

0.72-0.85 |

−0.12 |

−0.13 |

5.44 |

| 20H2@Li10Si10 |

0.73-0.83 |

−0.11 |

−0.12 |

10.32 |

| 30H2@Li10Si10 |

0.74-0.82 |

−0.10 |

−0.10 |

14.72 |

| Li12Si5 |

0.30-0.78 |

- |

- |

- |

| 12H2@ Li12Si5 |

0.63-0.84 |

−0.16 |

−0.17 |

9.76 |

| 22H2@ Li12Si5 |

0.60-0.82 |

−0.13 |

−0.14 |

16.54 |

| 24H2@ Li12Si5 |

0.59-0.81 |

−0.14 |

−0.14 |

17.78 |

| 32H2@ Li12Si5 |

0.60-0.82 |

−0.12 |

−0.13 |

22.38 |

| 34H2@ Li12Si5 |

0.63-0.82 |

−0.11 |

−0.12 |

23.45 |

| Li12Si12 |

0.75-0.89 |

|

|

|

| 12H2@Li12Si12 |

0.76-0.85 |

−0.11 |

−0.12 |

5.44% |

| 24H2@Li12Si12 |

0.77-0.84 |

−0.11 |

−0.12 |

10.32% |

| 36H2@Li12Si12 |

0.78-0.83 |

−0.11 |

−0.11 |

14.72% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).