1. Introduction

Since the beginning of Human history, the Moon has captivated human imaginations and influenced social and cultural evolution with its mystical beauty. Ancient civilisations, such as the Greeks, Babylonians, and Egyptians, recorded the regular motion of the Moon across the sky. It was not until 1610, before the Age of Enlightenment, that Galileo Galilei (Gingerich, 2024) discovered moons orbiting Jupiter, which challenged the geocentric model and made Earth the centre of the Universe. This notion laid the foundation, suggesting the Moon could also orbit the Earth. Only with the rise of rocket technology and the beginning of space exploration was the Moon observed up close. In 1959, the soviet spacecraft Luna 1 (Crawford & Joy, 2014) became the first spacecraft to fly by the Moon, closely followed by Luna 9, which achieved the first soft landing in 1966. Luna 3, launched in 1959 (Crawford & Joy, 2014), was the first to capture images of the far side of the Moon that is never visible from Earth. The far side of the Moon is never visible from Earth because of what is called Tidal Locking. This locking is due to the rotation of the Moon at the same rate as its orbital motion, a phenomenon called synchronous rotation. This tidal locking is due to the gravitational interaction between the Earth and the Moon, which causes the rotation of the Moon to synchronise with its orbit. Not soon after, in the 1960s, the United States Ranger series (Crawford and Joy, 2014) captured detailed photographs of the Moon’s surface, revealing different topographical features and fine regolith. The ranger series continued till 1965 and paved the way for Human Lunar exploration missions, leading to the Apollo landings. In 1968, Apollo 8 (Crawford & Joy, 2014) was the first-ever human-crewed mission to orbit the Moon and safely return to Earth. The following year, on July 16th, 1969, they made history when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans (Crawford & Joy, 2014) to set foot on the Moon, marking a remarkable achievement of our Human ingenuity and endeavours. Since then, five more manned missions, namely Apollo 12,14,15,16 and 17, have landed on the Moon with another ten astronauts (Crawford & Joy, 2014) walking on the surface, after which the Apollo missions were concluded. Since then, there has been no manned mission to the Moon. In 2017, NASA announced the Artemis program, which aims to send astronauts to the Lunar surface again and permanently establish a sustainable human presence there. Artemis 1 was launched as an uncrewed mission on November 16th, 2022, to test the Orion Spacecraft and SLS (Space Launch System rocket). Artemis 2 and 3 are scheduled for late 2025 and 2026 for Moon flyby and crewed landing, respectively. This history of Lunar exploration exemplifies its importance for the future of space exploration, but that comes with a tremendous scientific challenge and understanding the nature of the Moon itself.

Unlike Earth, the Moon has no global magnetic field and a thick atmosphere to safeguard itself from the harsh conditions of harmful space radiation. The absence of protection exposes any astronauts on the lunar surface to extremely high doses of radiation. NASA's standard radiation dose for a person on Earth is about 0.0036 Sv (Sievert) / year ( 0.36 rad) (Scarano, 2023). During the Apollo missions, astronauts, on average, received around 0.38 rad dosages. Apollo 14 received the average highest skin dose, around 1.14 rad, for a mission duration of 12 days (Scarano, 2023). Further data from research studies conducted by NASA showed that female astronauts have a higher chance of being affected by radiation during a lunar mission. These radiation dosages are enough, even during a brief period, to create acute and chronic health issues, including cataracts and heart diseases. Extreme radiation dosage due to sudden events or localised radiation on the Lunar surface can lead to short-term radiation illness and an incremental risk of getting cancer. The estimated radiation exposure can go up to 150 times (Scarano, 2023) the average dose on Earth, posing on Earth, posing an extremely significant challenge in crewed lunar exploration. Thus, this is one of the primary reasons for understanding the effects of Lunar space weather. Another critical challenge associated with the Lunar space weather environment is the Lunar Regolith, which can be charged in nature. The secondary formation of the lunar regolith due to radiation interaction posed a significant challenge for astronaut spacesuits and equipment. It showed irritation and the potential to damage equipment, making walking, data, and communicating hard. This paper aims to understand these different space weather processes of the Lunar environment and subsequently propose a novel mission initiative named 'Lunar Space Weather Observatory' a dedicated space weather mission for understanding the Lunar Space Weather in a more detailed way and offering solutions to the challenges that it brings to exploration and future habitation on Lunar surface.

2. Overview of Lunar Space Weather

In our Solar system, the Sun is the primary source of space weather. The solar activities of the Sun provide the first line of a solid framework for understanding Lunar space weather. The Sun has a layered structure where the core's innermost region undergoes nuclear fusion, known as the proton-proton chain reaction, where hydrogen nuclei fuse to form helium nuclei (Patzek and Rüsch, 2022). This reaction releases a tremendous amount of energy in the form of a gamma-ray that serves as the heat the Sun emits and the visible light observed. The other regions of the Sun are the radiative zone, an interface layer, a convective zone, a Photosphere, a Chromosphere, and the outermost layer called the Corona, respectively (Townsend, 2020). All the layers have complex processes that contribute to the overall mechanism of how the sun behaves. In the context of space weather, the outermost layer, the Corona, is the most significant contributor to the space weather. The Corona is the source of the solar wind, a continuous stream of charged particles carried along with the Sun's magnetic field and extends throughout the solar system. Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs) (Townsend, 2020) are another primary influencer of space weather. CMEs are massive eruptions of plasma and magnetic fields from the Sun's Corona, where billions of tons of solar material (Buzulukova and Tsurutani, 2022) are accelerated into space at high speeds. It often happens due to the destabilisation of the Sun's magnetic field; this is also associated with Solar flares or other Solar energy particle events. SEPs also comprise highly energetic particles such as protons and heavier ions that affect space weather. All these above factors from the Sun contribute to the Lunar Space weather conditions as solar wind and frequent SEPs. Other significant contributors to the Lunar Space Weather besides the Sun are the Galactic Cosmic Rays, high-energy particles originating outside the solar system. They are likely to be formed by supernova explosion events. The lack of a thick atmosphere and micrometeoroids caused by bombardments also impact the lunar surface by fracturing rocks and creating finer regolith.

The Moon has no substantial atmosphere or magnetic field, but the Moon has an exosphere. The exosphere is too thin to entrap or spread the energy of the Sun. This temperature difference creates an extreme thermal environment (Patzek and Rüsch, 2022) between the sunlit and the shadowed regions. Temperatures can rise to 121°C during the daytime and plummet to around -133°C during the nighttime. These fluctuations in temperature contribute to the Lunar thermal cycling processes (Patzek and Rüsch, 2022) that cause thermal stress, leading to weathering and breakdown of surface materials. Thermal cycling was a cause of concern during the Apollo missions, resulting in restrictions on both duration and landing time of day. Overheating of the Lunar Roving Vehicle battery caused significant issues in Apollo 16 and 17 due to the local thermal environment and accumulation of lunar dust. Solar wind plasma continuously bombards the lunar surface (Townsend, 2020). However, the solar wind properties can vary over different timescales, leading to short-term and long-term variations in the charged particles impacting the Lunar Surface. The Moon Spends about a quarter of its time downstream, which defines the location of the Moon on the other side of the Earth, opposite to the direction of Solar wind flow. The period of the Moon that it remains at Earth’s bow shocks in the magnetosheath, a region of space between the bow shock and magnetopause where solar wind is significantly slowed and compressed due to interaction with the Earth’s magnetic field. This region is where the properties of the plasma are different to those in the undisturbed solar wind. On average, the far side of the Moon faces more frequently toward the undisturbed solar wind. Charged particles from the solar wind break chemical bonds of the surface materials and form new molecules and chemical minerals like hydroxyl (Denevi et al., n.d.). These processes also produce soft X-ray emissions. The magnetic anomalies present in some local regions on the lunar surface also affect the impact of local plasma, leading to non-isotropic particle precipitation, which indicates that charged particles (Schwadron et al., 2012) from the solar wind or magnetospheric plasma are not uniformly distributed across the surface. It also affects the weathering of the lunar surface. The following section discusses a few critical Lunar processes and features for understanding the Lunar environment and how the Lunar Space weather environment directly impacts them.

2.1. Lunar Space Weather Processes

2.1.1. Space Weathering

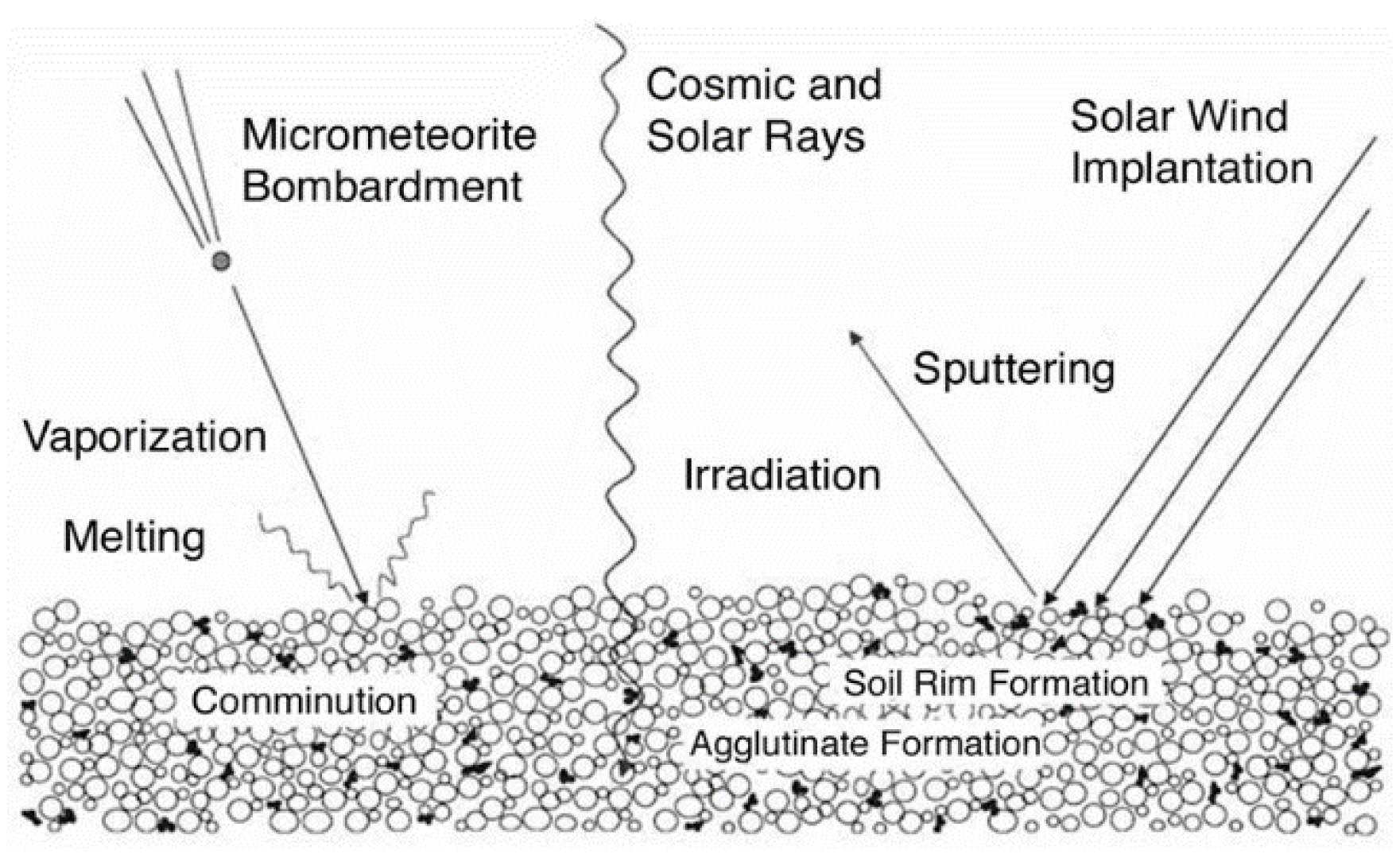

Space Weathering is the process that alters the surface compositions and features (Denevi et al., n.d.) due to various chemical and physical interactions. It is used primarily for bodies such as planets, moons, asteroids, or comets in outer space. The primary causes of space weathering on the lunar surface are solar wind, micrometeoroid impacts, cosmic radiation, and thermal cycling (Denevi et al., n.d.). The solar wind continuously bombards the lunar surface. Solar protons play a significant role in space weathering on the lunar surface. These high-energy protons impact the lunar surface and cause various effects, including sputtering, implantation, and radiation damage to the surface materials. These can permanently alter the chemical and physical properties of the materials. Changes can also be observed or estimated in terms of changes in reflectance, changes in colour and variations in mineralogy composition over time.

Sputtering is one of the critical mechanisms that is triggered by the space weathering effect (Williams, 1979) on the Moon. During sputtering, the kinetic energy of the incoming protons dislodges atoms from the surface of lunar rocks and regolith. These ejected atoms get implanted into neighbouring regolith or may eventually escape to space. Prolonged periods of sputtering can result in the removal of surface materials and the creation of a thin layer of altered material, generally called the Lunar soil, (Denevi et al., n.d.) that covers a large portion of the lunar surface. Thus, understanding space weathering effects and the associated mechanisms is essential as it allows us to see how this continuously suspended regolith affects the environment and plays a role in the evolution of the lunar surface.

2.1.2. Regolith formations

Lunar Regolith is a thick layer of fragmented, unconsolidated rocky materials covering the entire lunar surface. The regolith layer is estimated to be around 4-5 m thick in the mare region and can be about 10-15 metres in highland areas

(Noble, n.d.). The range of sizes can be from boulders to sub-micron dust-like particles. Formed primarily by meteoritic impacts and the subsequent pulverisation of lunar rocks, regolith consists of a heterogeneous mixture of fine dust, gravel-sized particles, larger rock fragments, and even boulders

(Noble, n.d.). These materials accumulate over time due to ongoing impacts from meteoroids and micrometeorites, continuously breaking down and churning the surface layers. Additionally, the lunar regolith is heavily influenced by space weathering processes, particularly the effects of solar wind bombardment from the sun. The solar wind, consisting of high-energy particles, interacts with the lunar surface, causing chemical alterations and forming amorphous coatings on mineral grains

(Noble, n.d.). These coatings, along with the formation of agglutinates, a significant component of lunar soils, and the creation of micro craters by micrometeorite impacts, are substantial contributors to the weathering and alteration of regolith over a long period.

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the processes.

The concept of maturity (Noble, n.d.) in lunar soils plays a pivotal role in understanding the geological history of the Moon's surface. Defined by various criteria, such as the percentage of agglutinates or the density of cosmic ray tracks, the standard measure of maturity in recent years has become the Is/FeO value (Noble, n.d.). It represents the intensity of ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) resulting from iron particles in a specific size range, typically normalised by the soil's iron content (FeO). This normalisation accounts for the fact that soils with higher iron content tend to produce nanophase iron more readily. An Is/FeO value below 30 indicates immaturity, corresponding to soils composed of 5-20% agglutinates, while values between 30-60 signify sub-maturity with ~15-50% agglutinates, and values over 60 indicate maturity, often characterised by 40-60% agglutinates (Noble, n.d.). The finer fractions of lunar soil exhibit higher nanophase iron content, indicating greater maturity, primarily due to two factors: the higher ratio of rim material to grain material in finer grains and the fragility of nanophase iron-rich agglutinate glass, which tends to break down into smaller grain sizes more readily (Noble, n.d.). Understanding the nuances of lunar soil maturity also gives insight into the lunar surfaces and regolith formation due to space weather processes over a long geological timescale.

2.1.3. Lunar Swirls

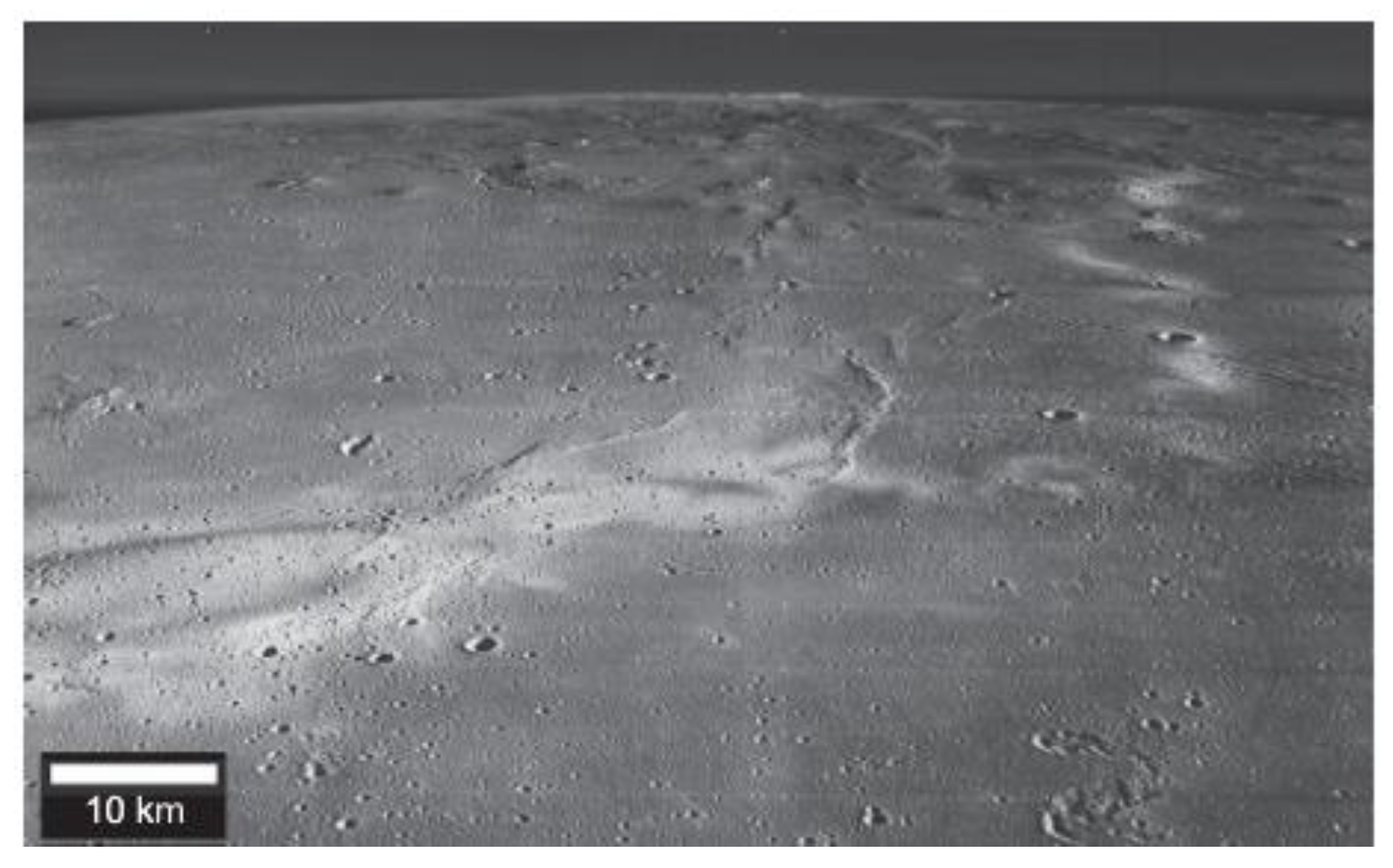

Lunar swirls are distinctive markings observed on the lunar surface, characterised by bright, looping patterns contrasted with darker lanes

(Bruck Syal and Schultz, 2015). These formations span hundreds of kilometres and are often found in regions with contrasting albedo features, such as the lunar maria or highlands. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the formation of lunar swirls. One prominent theory suggests that these features result from interactions between the lunar surface and space weathering processes. Space weathering encompasses various phenomena, including micrometeoroid bombardment, solar wind particle impacts, and exposure to cosmic radiation. These processes alter the physical and chemical properties of lunar regolith over time. Another hypothesis posits that magnetic anomalies may contribute to the formation of lunar swirls

(Bruck Syal and Schultz, 2015). Localised magnetic fields are suggested to shield the lunar surface from space weathering effects, preserving bright, unaltered regolith in swirl regions. An example of lunar swirl in

Figure 2.

Alternatively, electrostatic processes (Denevi et al., 2014) have been proposed as potential drivers of lunar swirl formation. Dust particles on the lunar surface become electrically charged due to interactions with solar radiation and the lunar plasma environment. These charged particles may be repelled or attracted to specific regions, forming patterns consistent with lunar swirls. Exposure to cosmic radiation induces chemical alterations in lunar minerals, forming space-weathering products such as nanophase iron particles (Denevi et al., 2014). These processes gradually darken the lunar regolith and contribute to the reddish hue observed in some regions. Space weathering processes continually modify the lunar surface, gradually altering the appearance of swirl regions. Moon swirls represent fascinating geological features that offer insights into the complex interactions between the Moon and its surrounding space environment. While their exact formation mechanisms remain debated, evidence suggests that space weathering processes are crucial in shaping these enigmatic patterns on the lunar surface.

2.1.4. Lunar Surface Roughening

Surface roughening is a fundamental aspect of planetary geology, influencing the morphology and evolution of planetary surfaces. On celestial bodies like the Moon, surface roughening refers to the unevenness or irregularity of the terrain, characterised by variations in elevation, slope, and texture over different spatial scales. Surface roughening on the Moon occurs through a combination of geological processes, the primary one being impact cratering (Berezhnoy, 2010). Impact craters are formed when meteoroids or asteroids collide with the lunar surface, excavating material and creating depressions of various sizes. These impact events contribute significantly to the ruggedness of the lunar landscape, with crater rims, ejecta blankets, and central peaks adding to the surface irregularity (Berezhnoy, 2010). Volcanic activity also plays a significant role in surface roughening, particularly in forming lunar maria. These vast plains of dark basaltic lava flows exhibit smoother surfaces than the heavily cratered highlands. However, the volcanic processes involved in the emplacement of lava flows can create subtle variations in surface roughness, including lava channels, tubes, and volcanic domes. Moreover, micrometeorite impacts, and other space weathering processes contribute to surface roughening on the Moon. Micrometeorites continuously bombard the lunar surface, chipping away at rocks and regolith particles, gradually altering surface features (Berezhnoy, 2010). Cosmic rays and solar wind particles also interact with the lunar regolith, inducing chemical reactions and modifying surface materials. Cosmic rays penetrate the lunar regolith, causing ionisation and producing secondary particles (Denevi et al., n.d.) that contribute to surface modification through processes like gardening. These processes contribute to the erosion and fragmentation of surface materials, further enhancing surface roughness. In addition to impact cratering, volcanic activity, and space weathering, other geological processes can influence surface roughening on the Moon. These include mass wasting events such as landslides and slumping, which can redistribute surface materials and create localised variations in roughness.

The lunar processes and features discussed so far give a brief overview of the complex dynamics of how different components of space weather, such as solar, wind, cosmic rays and micrometeoroids play significant roles in contributing to the overall lunar surface conditions. Understanding the observational data and knowledge gaps is crucial to determining what mission objectives will be considered for a dedicated Lunar space weather mission. With the scientific background established, knowing what processes of Lunar space weather and features of significant interest can be done for further studies, the next section of the paper proposes a novel mission to the Moon for a dedicated space weather mission.

3. Lunar Space Weather Observatory’(LSWO) – A Proposed Novel Space Weather Mission

The Lunar Space Weather Observatory is a proposed dedicated near-orbit space weather monitoring mission for the lunar environment. There is no dedicated presence of an orbiter or satellite dedicated to studying the weather for the Lunar surface and its exosphere. The only current mission rotating around the Moon is the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which NASA launched on June 18th, 2009 (Crawford and Joy, 2014). The main objective of the LRO was to create a high-resolution map of the lunar surface to identify future landing sites for human missions and resource gathering, including a survey for water ice deposits in the permanently shadowed regions of Polar craters. It also gathered data for day-night temperature maps and demonstrated the first laser communication with a lunar satellite in January 2013 (Keller and Chin, n.d.). Additional missions had space weather implications, such as observing water molecules moving around the dayside of the Moon and characterising lunar hydration changes throughout the daytime using one of its scientific instruments called the Lyman-Alpha Mapping Project (LAMP) (Keller and Chin, n.d.). Apart from that, only a few dedicated studies, such as Lunar space weathering characterisation and distribution of different sputtered ions from the surface due to solar wind to the exosphere. Observations of surface roughening over a long period to see variations have also never been conducted.

The proposed mission aims to fill these gaps in scientific research and data collection for different lunar environmental conditions due to space weather effects. The mission aims to provide long periods of high-resolution space weather monitoring platform, radiation environment mapping due to sputtering and space weathering conditions in regions of interest and understanding phenomena like Lunar Swirls and surface roughening due to prolonged space weather effects. With continuous monitoring of the lunar space weather, more data can be gathered on how solar wind and cosmic radiation levels affect intensity and variability at different Lunar regions. Space weather already poses a significant hazard to astronauts on the Moon and disruption of electronics and robotics systems (Scarano, 2023). This mission can provide real-time local space weather conditions so that mission planning can be assessed safely, considering radiation exposure and potential risks that can be mitigated, such as from sudden SPEs or incoming solar storms. With the establishment of a permanent weather monitoring platform, data can be collected for an extended period to observe changes and predict trends over time, which would be crucial for mission developments and understanding phenomena that have yet to be studied. Establishing its objectives and scientific goals is essential to develop a mission. The following sections will explore the scope of how a mission for Lunar space weather can be evaluated.

3.1. Mission Description

The proposed LSWO mission will be conducted in multiple phases: deployment, commissioning, and long-term operation. The LSW- observatory is a near-orbit orbiter spacecraft running on solar energy with onboard solar panels. Once orbital insertion is done near the Moon, the whole system will undergo calibration procedures to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the scientific instruments to be used. The primary mission objectives of the mission are long-term space weather monitoring, radiation environment characterisation for localised regions, high-resolution sputtering distribution and characterisation for different ion contents on the lunar surface and exosphere. Observing variations for features such as lunar swirls and surface roughening over time is also a top science goal. Some instruments from the LRO mission are also crucial to scientific objectives for understanding lunar surface and environmental conditions, such as radiation and thermal cycle observations. Keeping this in consideration, the proposed instruments (

Table 1) for the LSWO orbiter are:

3.1.1. Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA)

This instrument measures global topography with high spatial resolution. It can provide detailed elevation profiles that would benefit future safe landing site assessments and the assessment of new landing sites. The working principle of LOLA (Keller and Chin, n.d.) is based on emitting short laser pulses of light in the near-infrared spectrum towards the lunar surface with real-time precision. The laser pulses can interact with terrain features such as craters, valleys, and mountains on the lunar surface. The laser light is reflected in the instrument to receive, capturing both the intensity and the precise time of return. The time delay between the emission of the pulse and the detection of the reflected receiving pulse is used by LOLA to calculate the distance of the orbiter to the surface terrain with high accuracy. The instrument can be systematically used to scan targets of interest from orbit. Raw data can generate high-resolution topographic maps and topographic variations (Keller and Chin, n.d.) in features like lunar swirls. LOLA can also help assess surface roughness using the same principle and investigate how space weather contributes to surface processes over a long period.

3.1.2. Lunar Space Weather Multispectral Cam (LSWMC)

The Lunar Space Weather Multispectral Camera represents a novel instrument proposed for this mission. The case for LSWMC is to utilise a multispectral imaging approach that can capture data across various wavelengths, including visible, near-infrared, infrared, Ultraviolet, and Ultraviolet. LSWMC will enable high-resolution monitoring of solar flares, CMEs, and Cosmic Ray events' interaction with the Lunar surface. By observing multiple spectral bands (Keller and Chin, n.d.) simultaneously, more data can be obtained for SPEs and high radiation impact events. The real-time capabilities of LSWMC can be crucial for assessing incoming hazards on the lunar surface to mitigate risk for lunar assets and future astronauts on their paths. Thus, the feasibility of such an instrument is very capable of adhering to specific scientific goals.

3.1.3. Cosmic Ray Telescope for the Effects of Radiation (CRaTER)

CRaTER is an instrument currently on board the LRO (Keller and Chin, n.d.). The instrument is specifically designed to measure the radiation environment around the Moon. The instrument can measure the flux of galactic cosmic rays (GCRs) and solar energetic particles (SEPs). It has a suite of detectors under a shielded structure to accurately quantify the incoming cosmic radiation's energy, composition, and temporal variations. CRaTERS' detectors are susceptible to ionising radiation such as protons, heavy ions, and electrons. It can distinguish between different types of radiation particles based on their energy deposition characteristics (Keller and Chin, n.d.). By analysing the energy spectra of incoming particles, the instrument can determine the relative contributions of GCRs and SEPs of the overall Lunar radiation environment. The instrument's capability to spatially map localised radiation hotspots on the lunar surface can detect where space weather, like solar wind, interacts more with the lunar regolith since radiation-induced secondary particles can be detected (Keller and Chin, n.d.). Thus, the CRaTER instrument is also crucial for assessing hazards and mitigating risks on the Lunar Surface for navigation.

3.1.4. Lunar Space Sputtering Detector (LSSD)

The Lunar Space Sputtering Detector is proposed as a more specified scientific goal to investigate the process of space weathering on the Lunar surface by measuring sputtering effects caused by solar wind plasma and micrometeoroid impacts. The instrument proposed has sensitive detectors such as Scintillation detectors, ion detectors and solid-state detectors, capable of measuring the flux, energy, and composition of the particles ejected from the lunar surface due to sputtering events. The instrument's principle is that the detectors are designed to capture and analyse ejected particles from the surface. The measurement of energy distribution and elemental composition can be used to characterise the physical as well as chemical properties of the lunar surface materials (Denevi et al., 2014). Analysing the sputtering yield as a function of particle energy and incident angle, LSSD can give insight into the mechanisms driving Lunar soil erosion and alteration. The LSSD must be operated over a long period to get enough datasets to generate trends for radiation or sputtering conditions over a local lunar region.

3.1.5. Neutron-Detector for Lunar Space Observation (NLSO)

Neutron-detectors Lunar Space Observation (NLSO) is another proposed instrument crafted to precisely study hydrogen-bearing compounds (Mitrofanov et al., 2010) within the lunar regolith, particularly water ice, shaping the course of lunar exploration. Employing sophisticated neutron detection techniques, NLSO discerns thermal and epithermal neutrons emitted from the lunar surface due to cosmic ray interactions. These neutrons, stemming from nuclear reactions involving hydrogen atoms, indicate hydrogen-rich materials. NLSO's spatially resolved measurements enable detailed mapping of hydrogen distribution across the lunar landscape, aiding in identifying potential water ice deposits and other hydrogen-rich environments (Mitrofanov et al., 2010). Additionally, by continually monitoring neutron emissions, NLSO captures temporal variations, offering insights into seasonal fluctuations and the stability of water ice deposits over time. Its significance extends to water ice exploration, planetary science, and resource assessment, contributing crucial data for future lunar missions and sustainable infrastructure development.

Table 1.

Summary of all the instruments proposed for the LSWO mission.

Table 1.

Summary of all the instruments proposed for the LSWO mission.

| Instrument name |

Function |

Possible implications |

| Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA) |

Measures lunar surface topography with high precision using laser pulses. |

Facilitates safe landing site assessments and monitors surface changes over time. |

| Lunar Space Weather Multispectral Cam (LSWMC) |

Monitors solar flares, CMEs, and Cosmic Ray events' impact on the Lunar surface in real-time. |

Enables hazard assessment for lunar assets and future astronauts. |

| Cosmic Ray Telescope for the Effects of Radiation (CRaTER) |

Quantifies galactic cosmic rays (GCRs) and solar energetic particles (SEPs) to assess radiation hazards |

Identifies radiation hotspots and assesses risks for lunar navigation. |

| Lunar Space Sputtering Detector (LSSD) |

Measures sputtering effects from solar wind and micrometeoroid impacts, analysing lunar surface erosion. |

Characterizes lunar soil erosion and investigates radiation effects over time. |

| Neutron-detector for Lunar Space Observation (NLSO) |

Detects hydrogen-bearing compounds like water ice in the lunar regolith by measuring emitted neutrons. |

Maps potential water ice deposits and monitors temporal variations for resource assessment. |

3.2. Scientific Rationales for Mission Goals

The proposed Lunar Space Weather Observatory (LSWO) mission would collect a vast amount of real-time observation data and scientific information to advance our understanding of the Lunar space weather environment in a very detailed way. Scientific knowledge of mission expectations and target goals must back the feasibility and the operability of such a novel mission. The primary goal is to monitor the solar-wind interaction and the associated sputtering effects for localised regions. The LSWO would monitor solar wind parameters such as velocity, density, and composition. By analysing variations in solar wind fluxes, scientists can study the interaction between solar wind particles and the lunar surface, including the process of sputtering that leads to the ejection of surface material (Denevi et al., 2014). Understanding the dynamics of solar-wind interaction is crucial for deciphering the mechanisms behind surface darkening and regolith formation on the Moon. The mission would measure the flux and characteristics of micrometeoroids impacting the lunar surface. By studying impact craters and regolith properties, scientists can assess the rate of regolith accumulation and the role of micrometeoroid bombardment in shaping the lunar surface. Data on impact events and regolith composition would provide insights into the long-term evolution of the lunar regolith layer and its relationship to space weathering processes. The LSWO would monitor ultraviolet (UV) radiation levels at the lunar surface. UV radiation is crucial as it induces chemical reactions and surface alteration processes on the Moon, including forming reactive radicals and breaking surface materials. By quantifying UV radiation fluxes, scientists can investigate the extent of surface alteration due to UV exposure and its contribution to lunar space weathering.

The LSWO mission with the proposed instrument suites would be capable of measuring cosmic radiation levels at the lunar surface. High-energy cosmic rays can induce damage to surface materials and contribute to space weathering (Denevi et al., n.d.) processes on the Moon. By assessing cosmic radiation fluxes and their energy spectra, scientists can study the effects of cosmic radiation on surface erosion, mineralogical changes, and radiation-induced defects in lunar materials. Combining instruments like LSWMC and LSSD, the LSWO mission can study variations in the lunar magnetic field and their relationship to the formation of lunar swirls. Lunar swirls are enigmatic bright features observed on the lunar surface, often associated with magnetic anomalies. By mapping magnetic field variations and correlating them with surface features, scientists can investigate the role of magnetic shielding in protecting certain areas from space weathering effects and the formation mechanisms of lunar swirls. The high-level goal of the mission is to conduct and establish long-term monitoring of the lunar space weather environments. The mission will eventually be crucial for identifying trends and temporal variations. By analysing multi-year datasets, scientists can assess the impact of solar cycle variations, episodic space weather events, and long-term environmental changes on lunar space weathering processes. Overall, the scientific rationales for observations and data collection from the Lunar Space Weather Observatory (LSWO) aim to advance our understanding of lunar space weathering phenomena and their effects on the lunar environment. By gathering comprehensive datasets on solar wind interaction, micrometeoroid bombardment, UV radiation exposure, cosmic radiation fluxes, magnetic field variations, and long-term trends, the mission would significantly contribute to understanding complex dynamics and processes of Lunar interaction with outer space radiation.

4. Implications of Understanding Advanced Lunar Space Weather

So far, the paper has discussed the Lunar Space Weather environment and its intricate effects, and a novel mission proposal with adherence to scientific feasibility of instruments that can carry out scientific goals to further our understanding of Lunar Space Weather. This section will discuss the application of two essential implications such a mission would contribute to future lunar exploration and habitat establishment.

4.1. Lunar Communications and LunaNet

LunaNet is a new generation communication system proposed by NASA for the Artemis missions (Israel et al., 2020) to establish seamless communication from Earth to the Lunar surface by relay satellites. The architecture leverages existing networking techniques, standards, and an extensible framework to expand network capabilities. The core network architecture is based on Delay/ Disruption Tolerant Networking (DTN), ensuring reliable data transmission despite signal disruptions (Israel et al., 2020). It can empower users with continuous connectivity, eliminating the need for advanced scheduling and maximising communication opportunities and efficiencies. Astronauts on the lunar surface can receive real-time alerts from the LSWO Orbiter instruments. For instance, sudden incoming solar flares can trigger warnings to allow astronauts to return to base or seek cover promptly. LunaNet can also ensure operational independence from Earth-based data processing while maintaining high precision for lunar navigation (Israel et al., 2020). This autonomy is crucial for crewed and robotic missions to determine their locations accurately and mission plans accordingly. LunaNet can also provide critical information to users to enhance situational awareness for astronauts, rovers and other assets on the lunar surface. LunaNet's detection capabilities extend to lunar search and rescue (LunaSAR), offering location data to distressed beacons in the event of contingencies, ensuring the safety and well-being of astronauts. Additionally, LunaNet science services enable nodes to perform measurements for researchers on Earth, facilitating comprehensive studies of the lunar environment over time and advancing scientific knowledge. LunaNet's integration with space weather instruments on board LSWO ensures timely warnings, network resilience and improved safety for lunar missions.

4.2. Lunar Habitat and Exploration

Space weather phenomena can elevate radiation levels on the lunar surface, endangering astronauts' health and compromising the viability of lunar habitats. Comprehending space weather patterns is essential for devising effective radiation shielding techniques and operational guidelines to reduce astronaut exposure during lunar expeditions. Solar storms and other space weather disturbances can trigger power grid malfunctions and disrupt life support systems on lunar habitats and exploration vehicles (Scarano, 2023). Enhanced knowledge of space weather conditions facilitates the deployment of robust power generation and storage systems, along with contingency life support mechanisms, to safeguard the well-being and survival of crew members amidst adverse space weather circumstances. The influence of space weather on resource utilisation endeavours like mining, processing, and water extraction on the lunar surface must be considered (Scarano, 2023). By grasping the implications of space weather on resource availability and extraction processes, lunar exploration missions can optimise resource utilisation strategies and ensure the sustainability of long-term lunar habitats and infrastructure. Space weather predictions are pivotal in planning and executing missions, impacting decisions concerning launch schedules, extravehicular activities (EVAs), and surface operations (Scarano, 2023). Utilising all available space weather and local lunar radiation hazard data from the LSWO can empower mission planners to anticipate and mitigate potential risks, enhancing the safety and efficacy of lunar exploration missions and habitat maintenance and security.

5. Conclusion

To conclude, this paper provides a comprehensive overview of lunar space weather. Discussion about the Lunar processes and features such as Lunar swirl, surface roughening and ion sputtering showed there are much to uncover about the Moon’s environment and how space weather affects it. With scientific understanding of the overall lunar space weather interactions , a pioneering solution in the form of a novel mission for Lunar Space Weather study for advancing and filling current knowledge gaps is proposed. Some instruments are suggested from the already present LRO mission. The other instruments such as the LSWMC,LSSD and NLSO are novel instruments discussed with a scientifically validated approach that can be a ground for breakthrough innovation for Lunar space weather studies. The Lunar Space Weather Observatory mission can significantly contribute to our understanding of lunar space weather and enhance the prospects of successful lunar exploration.

References

- Berezhnoy, A.A. , 2010. Meteoroid bombardment as a source of the lunar exosphere. Adv. Space Res. 45, 70–76. [CrossRef]

- Bruck Syal, M. , Schultz, P.H., 2015. Cometary impact effects at the Moon: Implications for lunar swirl formation. Icarus 257, 194–206. [CrossRef]

- Buzulukova, N. , Tsurutani, B., 2022. Space Weather: From solar origins to risks and hazards evolving in time. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 9, 1017103. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, I.A. , Joy, K.H., 2014. Lunar exploration: opening a window into the history and evolution of the inner Solar System. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 372, 20130315. [CrossRef]

- Denevi, B.W. , Noble, S.K., Christoffersen, R., Thompson, M.S., Glotch, T.D., Blewett, D.T., Garrick-Bethell, I., Gillis-Davis, J.J., Greenhagen, B.T., Hendrix, A.R., Hurley, D.M., Keller, L.P., Kramer, G.Y., Trang, D., n.d. Space Weathering At The Moon.

- Denevi, B.W. , Robinson, M.S., Boyd, A.K., Sato, H., Hapke, B.W., Hawke, B.R., 2014. Characterization of space weathering from Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera ultraviolet observations of the Moon: Space weathering from LROC UV. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 119, 976–997. [CrossRef]

- Gingerich, O. , 2024. Galileo, the Impact of the Telescope, and the Birth of Modern Astronomy.

- Israel, D.J. , Mauldin, K.D., Roberts, C.J., Mitchell, J.W., Pulkkinen, A.A., Cooper, L.V.D., Johnson, M.A., Christe, S.D., Gramling, C.J., 2020. LunaNet: a Flexible and Extensible Lunar Exploration Communications and Navigation Infrastructure, in: 2020 IEEE Aerospace Conference. Presented at the 2020 IEEE Aerospace Conference, IEEE, Big Sky, MT, USA, pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Keller, J. , Chin, G., n.d. LUNAR RECONNAISSANCE ORBITER: INSTRUMENT SUITE AND OBJECTIVES.

- Mitrofanov, I.G. , Bartels, A., Bobrovnitsky, Y.I., Boynton, W., Chin, G., Enos, H., Evans, L., Floyd, S., Garvin, J., Golovin, D.V., Grebennikov, A.S., Harshman, K., Kazakov, L.L., Keller, J., Konovalov, A.A., Kozyrev, A.S., Krylov, A.R., Litvak, M.L., Malakhov, A.V., McClanahan, T., Milikh, G.M., Mokrousov, M.I., Ponomareva, S., Sagdeev, R.Z., Sanin, A.B., Shevchenko, V.V., Shvetsov, V.N., Starr, R., Timoshenko, G.N., Tomilina, T.M., Tretyakov, V.I., Trombka, J., Troshin, V.S., Uvarov, V.N., Varennikov, A.B., Vostrukhin, A.A., 2010. Lunar Exploration Neutron Detector for the NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Space Sci. Rev. 150, 183–207. [CrossRef]

- Patzek, M. , Rüsch, O., 2022. Experimentally Induced Thermal Fatigue on Lunar and Eucrite Meteorites—Influence of the Mineralogy on Rock Breakdown. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2022JE007306. [CrossRef]

- Scarano, M. , 2023. Impacts of Space Weather on Crew Safety for Lunar and Orbital Missions.

- Schwadron, N.A. , Baker, T., Blake, B., Case, A.W., Cooper, J.F., Golightly, M., Jordan, A., Joyce, C., Kasper, J., Kozarev, K., Mislinski, J., Mazur, J., Posner, A., Rother, O., Smith, S., Spence, H.E., Townsend, L.W., Wilson, J., Zeitlin, C., 2012. Lunar radiation environment and space weathering from the Cosmic Ray Telescope for the Effects of Radiation (CRaTER). J. Geophys. Res. Planets 117, 2011JE003978. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.W. , 2020. Space weather on the Moon. Phys. Today 73, 66–67. [CrossRef]

- Williams, P. , 1979. The sputtering process and sputtered ion emission. Surf. Sci. 90, 588–634. [CrossRef]

- Noble,S.(n.d.).The Lunar Regolith. url:. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/wp content/uploads/2019/04/05_1_snoble_thelunarregolith.pdf?emrc=0bd585.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).