Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- encourages empathy and global responsibility;

- develops strategic analysis skills;

- prepares students for professional reality, where decisions rarely affect a single area;

- stimulates creativity, interdisciplinarity, and thinking "out of the box";

- meets international requirements for transformative learning.

- think systemically;

- understand complex causal relationships;

- can build integrative and sustainable solutions;

- are able to anticipate risks, conflicts, or side effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background - Literature and Global Context

2.1.1. Key Data and Conclusions from the Sustainable Development Report 2024 on SDG 2

- An estimated 600 million people will suffer from hunger in 2030 if current trends are not reversed.

- The prevalence of undernutrition has increased again, reaching 10% of the global population in 2021, after years of decline.

- In parallel, the prevalence of obesity at a global level has increased alarmingly, from 9% in 2005 to 16% in 2022, generating a double challenge: undernutrition and overnutrition in the same communities or regions.

- Agriculture uses over 50% of the planet’s land area and approximately 70% of freshwater resources.

- Food systems are responsible for a third of global greenhouse gas emissions and are the main cause of biodiversity loss.

- Despite some local progress (for example, increasing cereal production from 3.4 tons/ha in 2000 to 4.4 tons/ha in 2021), the phenomenon of hunger at a global is increasing, fueled by conflicts, climate crises, economic inequalities, and price volatility.

2.1.2. SDG 2: Zero Hunger - A Central Node in the SDGs Architecture

2.1.3. The Need for Systemic Education About Food Security

2.2. Case Study Context

- understanding the concept of food security in all its dimensions (availability, accessibility, quality and stability);

- familiarizing students with the current challenges of food systems at global, European and national levels;

- developing systemic thinking and the ability to analyze the interdependencies between food security and other areas of sustainable development;

- forming an ethical awareness regarding responsible consumption, reducing food waste, and respecting natural resources.

2.3. Methodology of Teaching Activity

- Students were divided into working groups of three students each.

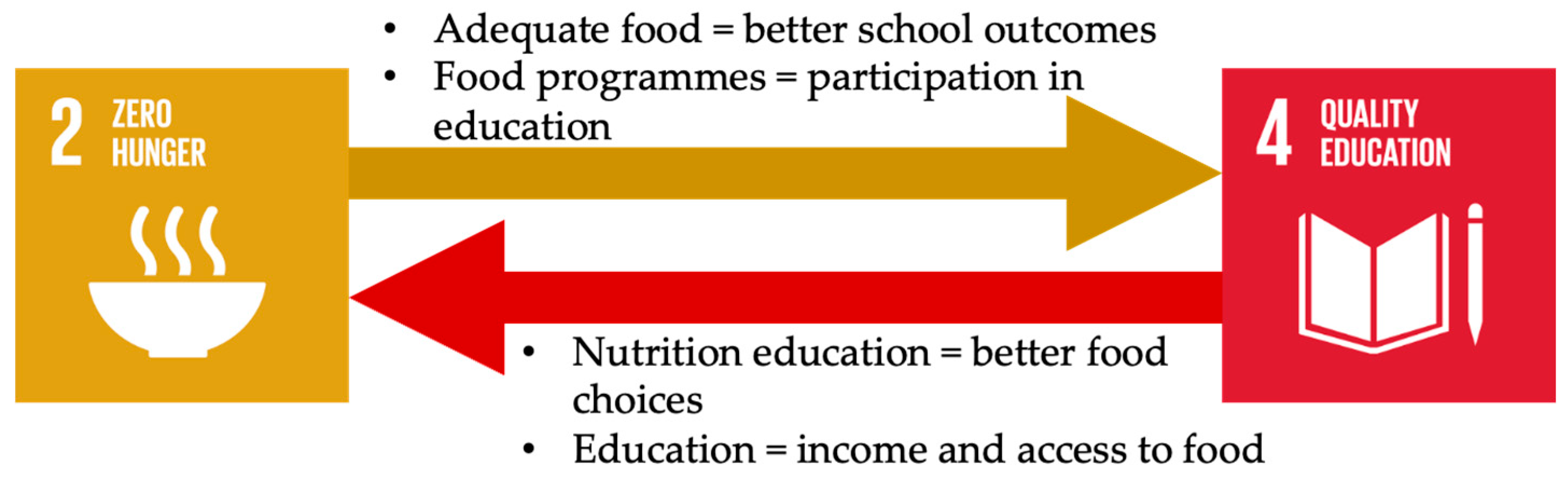

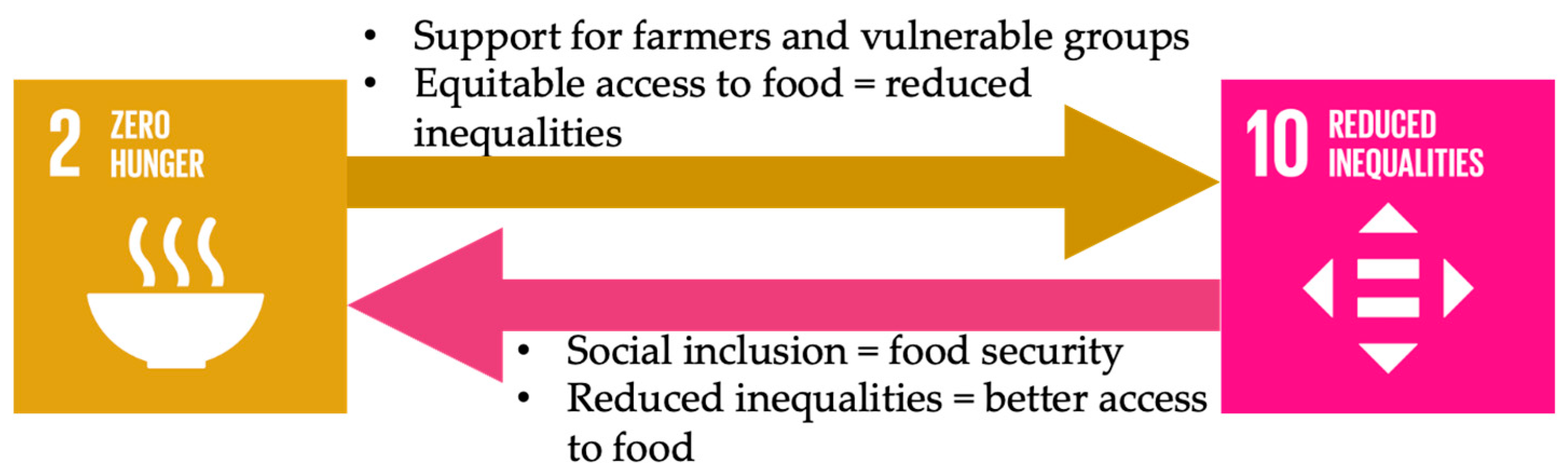

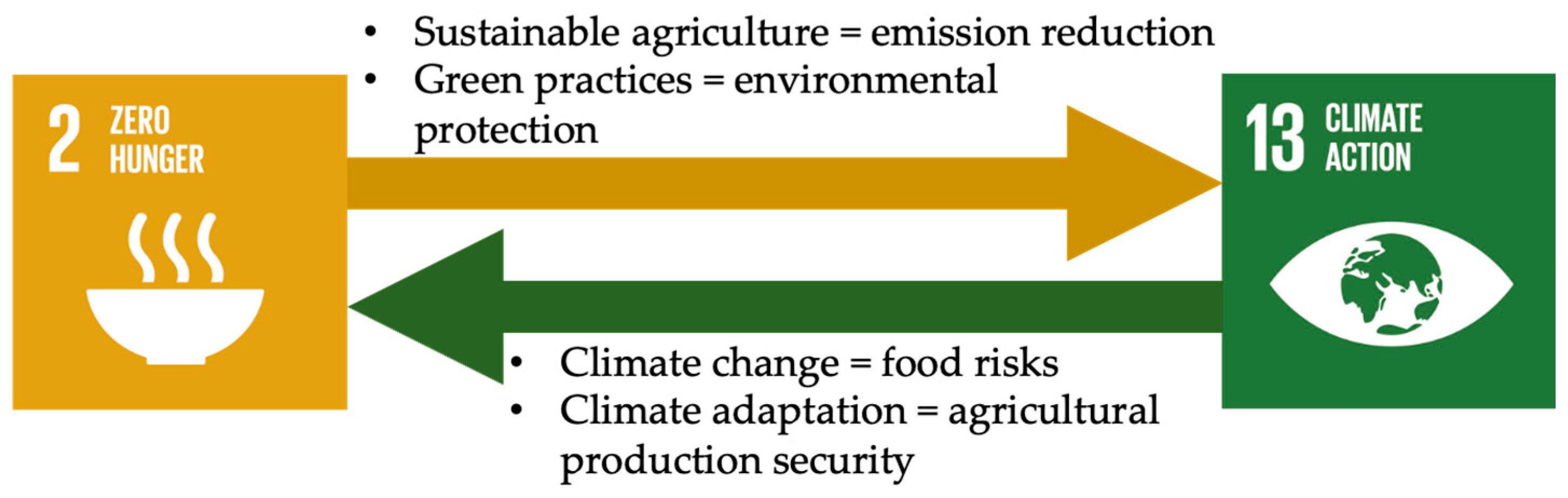

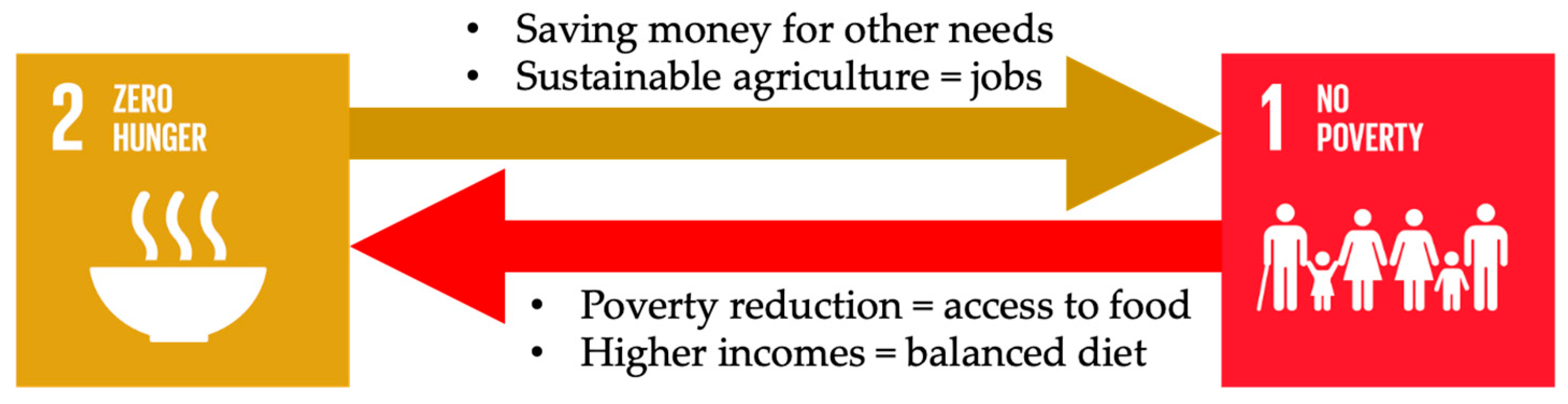

- Each group was assigned a pair or two of goals: SDG 2: Zero Hunger and another SDG (from SDG 1 to SDG 17, excluding SDG 2).

-

The task was twofold:

- -

- to analyze how SDG 2: Zero Hunger influences that SDG;

- -

- identify how that SDG in turn influences SDG 2.

- making an oral presentation (PowerPoint, flipchart, poster or creative board);

- oral supporting the ideas within a dedicated seminar;

- arguing the identified connections through examples, data or case studies;

- actively participating in discussions and feedback between groups.

- stimulating critical thinking;

- developing the capacity for systemic analysis;

- promoting creativity and teamwork;

- developing an ethical awareness in relation to food security;

- raising awareness regarding the role of SDG 2: Zero Hunger within the 2030 Agenda.

- theoretical and practical analysis;

- documentation based on FAO, UN, SDSN, Sustainable Development Report resources;

- visual activities: posters, charts, diagrams;

- presentations and debates in seminars.

2.4. Methodology of the Survey Applied to Students

- Section 1 - General data (academic year, group, completion date)

-

Section 2 - Perception of the usefulness and efficiency of the activity (5 items, Likert scale 1-5) [30]:

- The practical activity helping to better understand the SDGs.

- The analysis of the links between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and the other SDGs was interesting and useful.

- The working method (groups, presentations, boards, debates) was effective for learning.

- Better understood the role of food security in sustainable development.

- Enjoyning working as a team on this topic.

-

Section 3 - Perceived personal impact (5 items, Likert scale 1-5):

- 6.

- A result of this activity is to pay more attention to the diet.

- 7.

- Have become more mindful to food waste.

- 8.

- Believing that systemic thinking is important in solving global problems.

- 9.

- Feeling better prepared to analyze complex issues, such as food security.

- 10.

- Would recommend this activity to other students.

- Section 4 - Open Feedback (2 questions).

- 25 students in the 2023/2024 academic year;

- 21 students in the 2024/2025 academic year.

2.5. Organization of Teaching Activity: Time Allocation, Work Stages, and Applied Method

- internal brainstorming, within each team, to identify ideas;

- collective brainstorming, during seminars assigned to presentations, after each group’s presentation, when the entire group of students was actively involved in completing, commenting on and discussing the ideas presented.

2.6. Sources Used for Documentation and Development of Teaching Activities

- Reports, guides, official documents and educational materials developed by authoritative international organizations, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), United Nations (UN), Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), UNESCO, World Bank, and Sustainable Development Report.

- Recent scientific articles, published in journals indexed in recognized international databases (Web of Science, Scopus), available through international publishers such as Elsevier, Springer, Taylor & Francis, Wiley, MDPI etc.

- Relevant academic literature, identified through Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and Publons, with a focus on recent works (last 5-10 years) that address topics related to food security, education for sustainable development, analysis of interdependencies between SDGs and the formation of transversal skills in higher education.

- Grey literature, including case studies, technical reports, public policy documents, practical guides and educational resources available online.

3. Results

3.1. Visual Diagrams for the Main Connections Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and the Other SDGs

- how SDG 2: Zero Hunger contributes to achieving the other SDG analyzed;

- how that SDG in turn influences food security.

3.1.1. Analysis of the Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG1: No Poverty

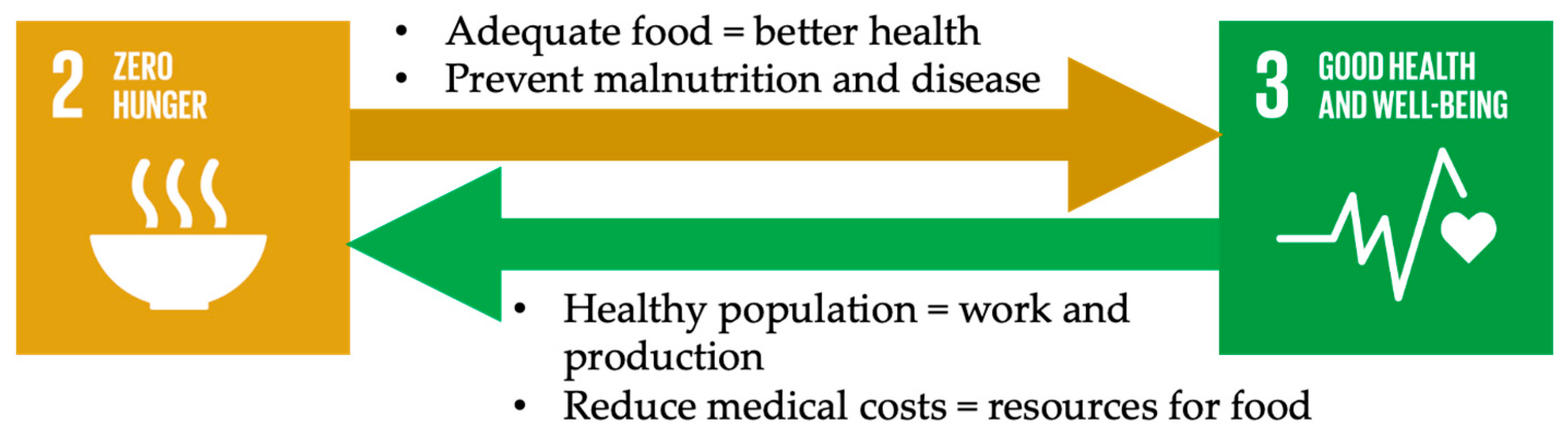

3.1.2. Analysis of the Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 3: Good Health and Well-Being

3.1.3. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 4: Quality Education

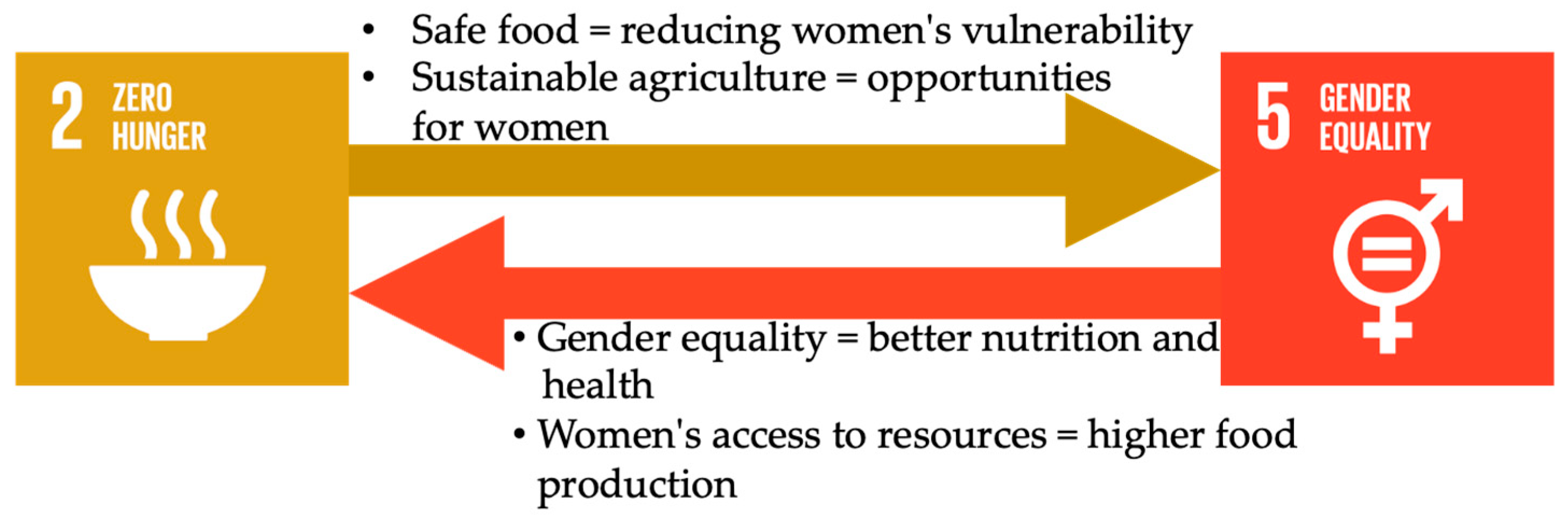

3.1.4. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 5: Gender Equality

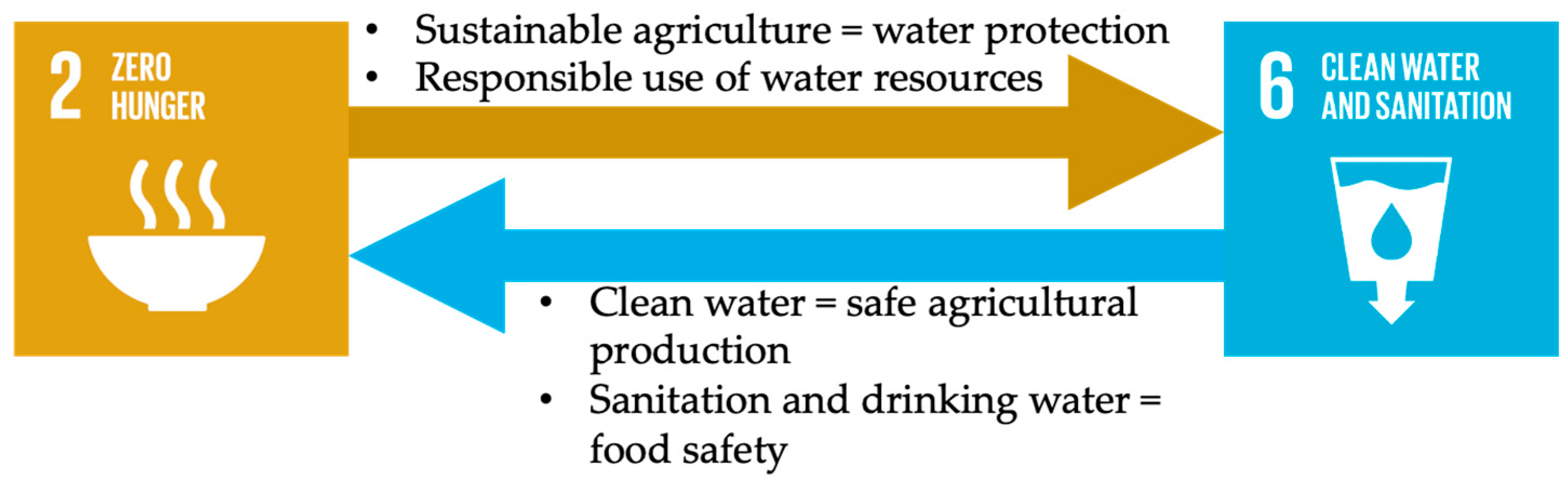

3.1.5. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

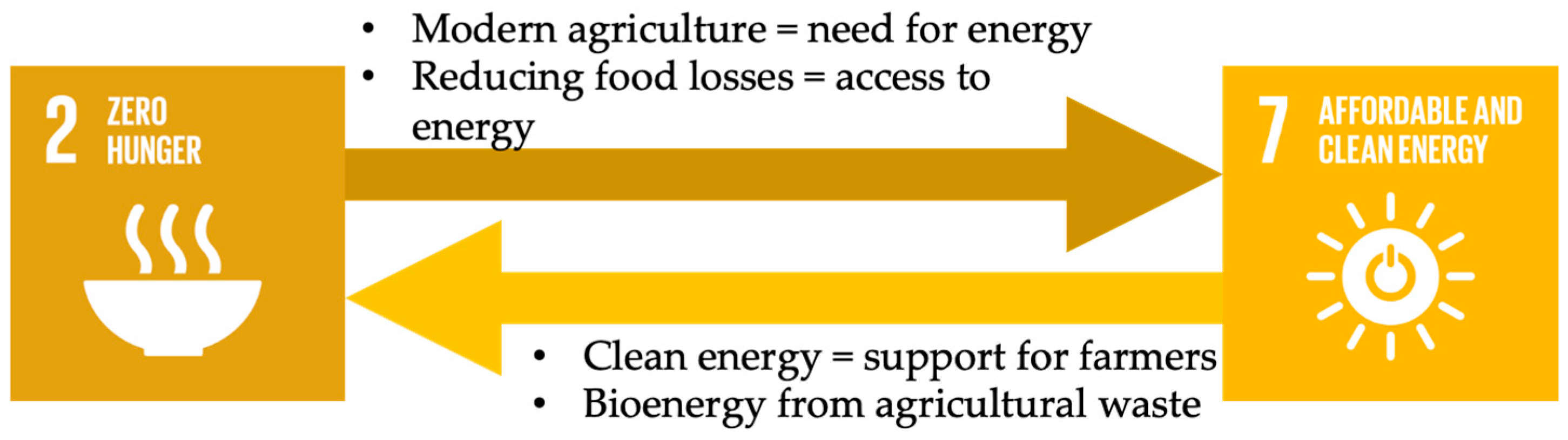

3.1.6. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

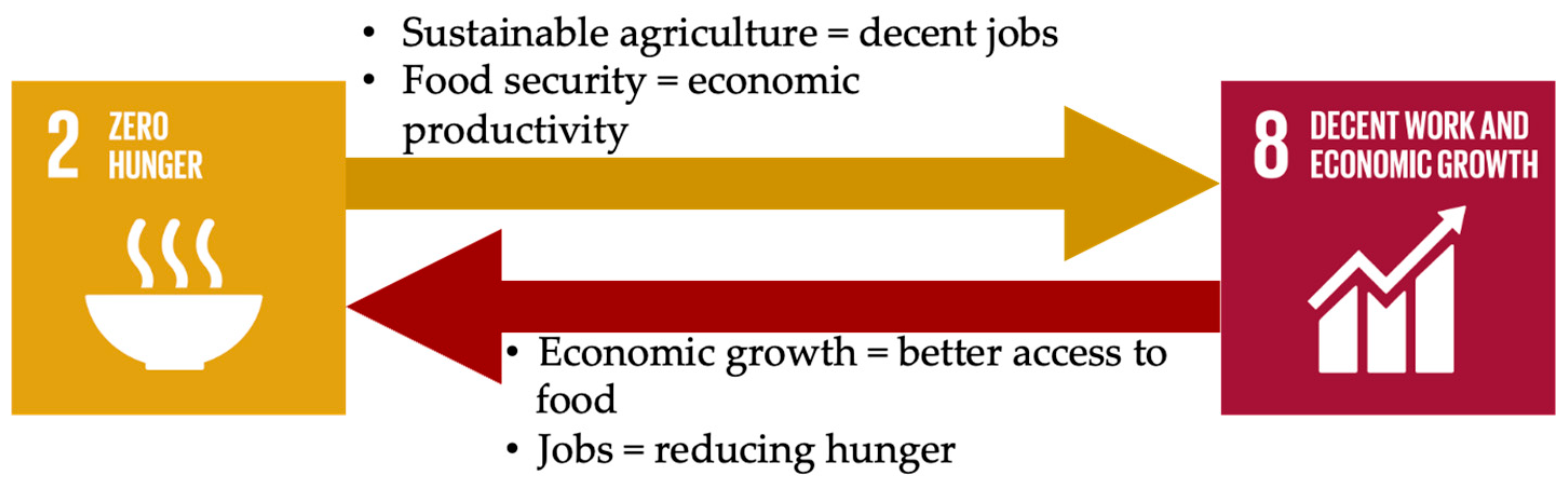

3.1.7. Analysis of the Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

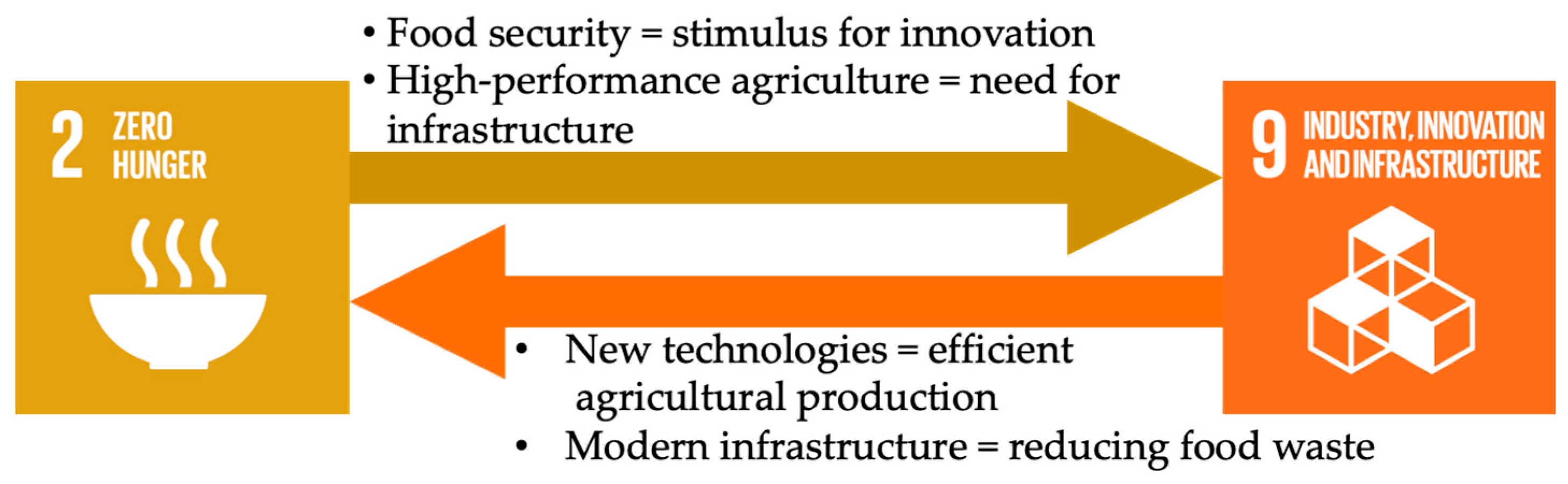

3.1.8. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

3.1.9. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

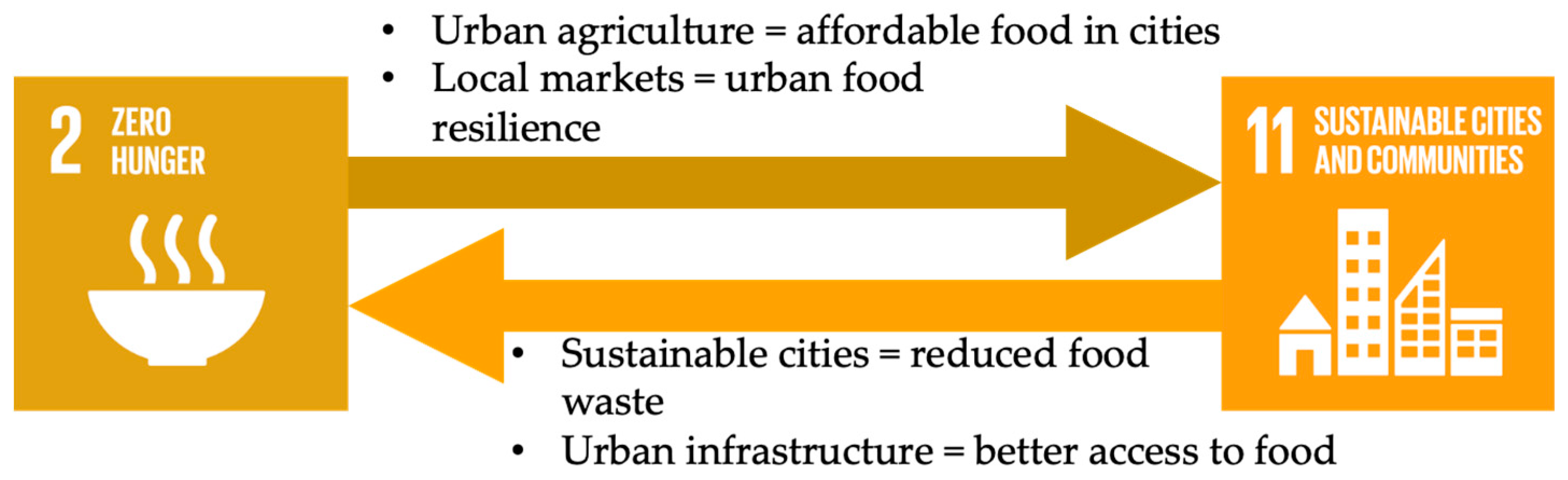

3.1.10. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

3.1.11. Analysis of the Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

3.1.12. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 13: Climate Action

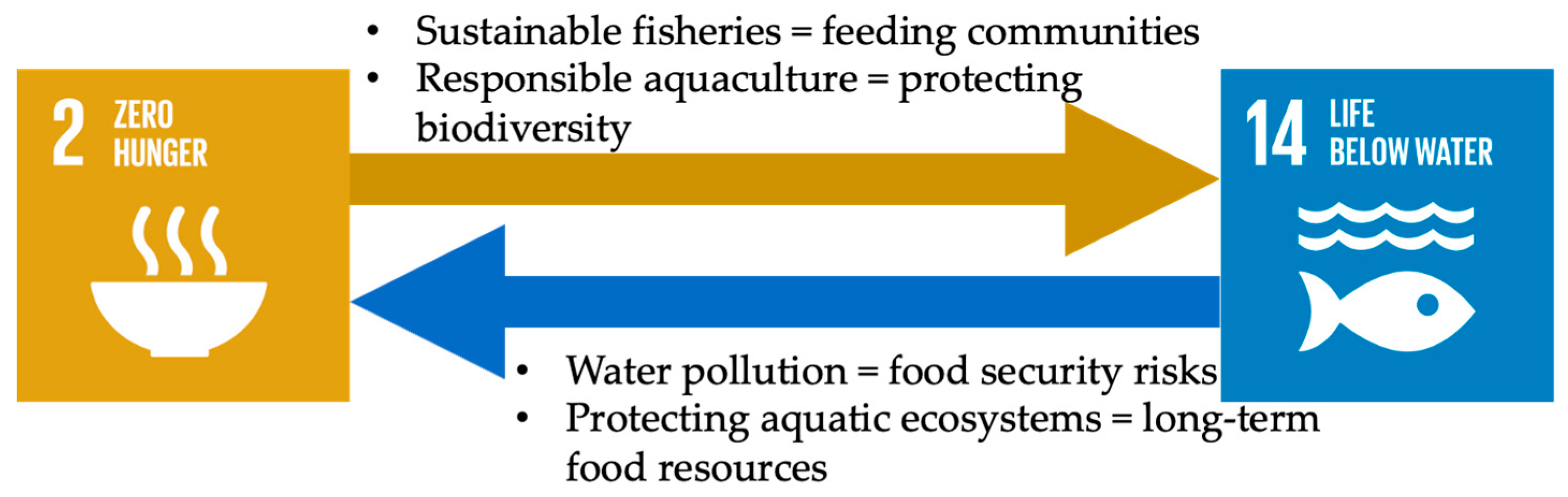

3.1.13. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 14: Life Below Water

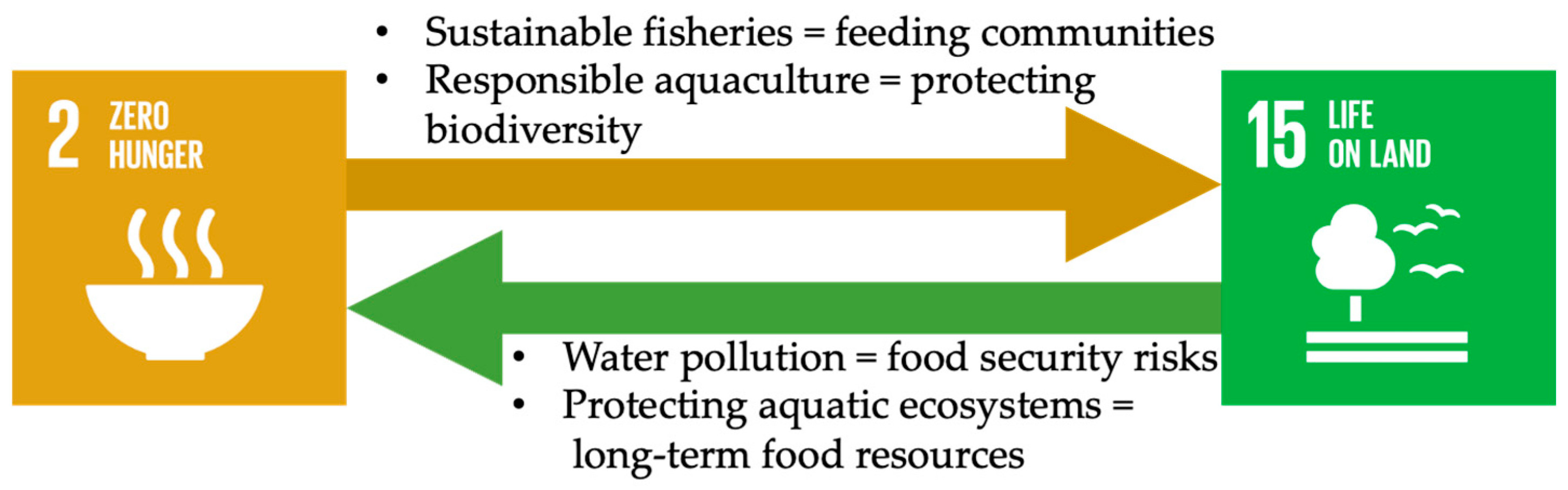

3.1.14. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 15: Life on Land

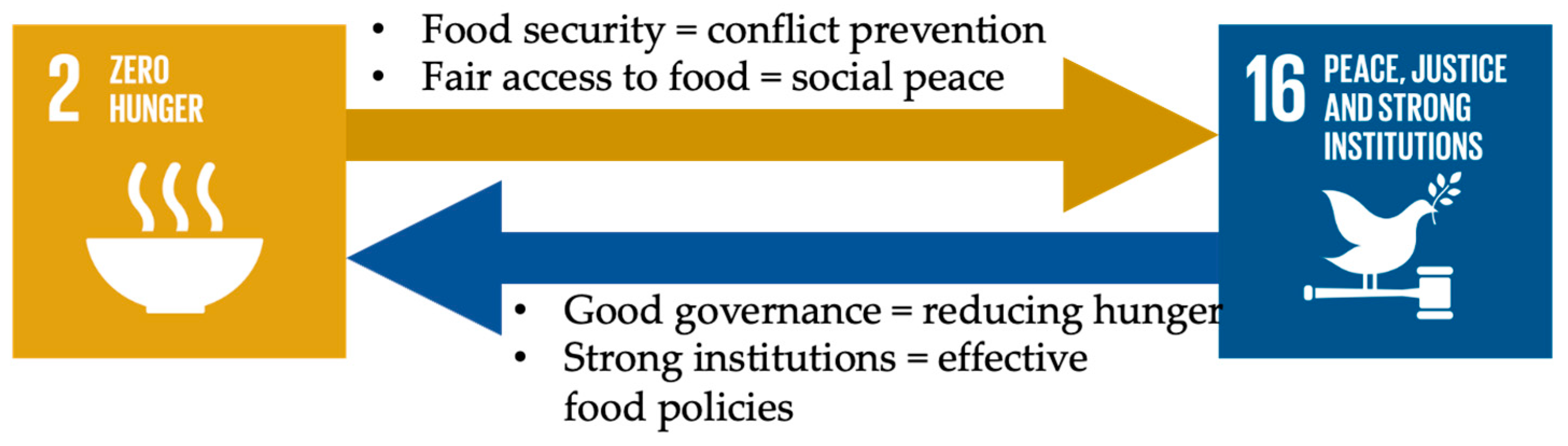

3.1.15. Analysis of the Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

3.1.16. Analysis of Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

3.2. Evaluation of Students’ Perception of the Usefulness and Impact of Educational Activity

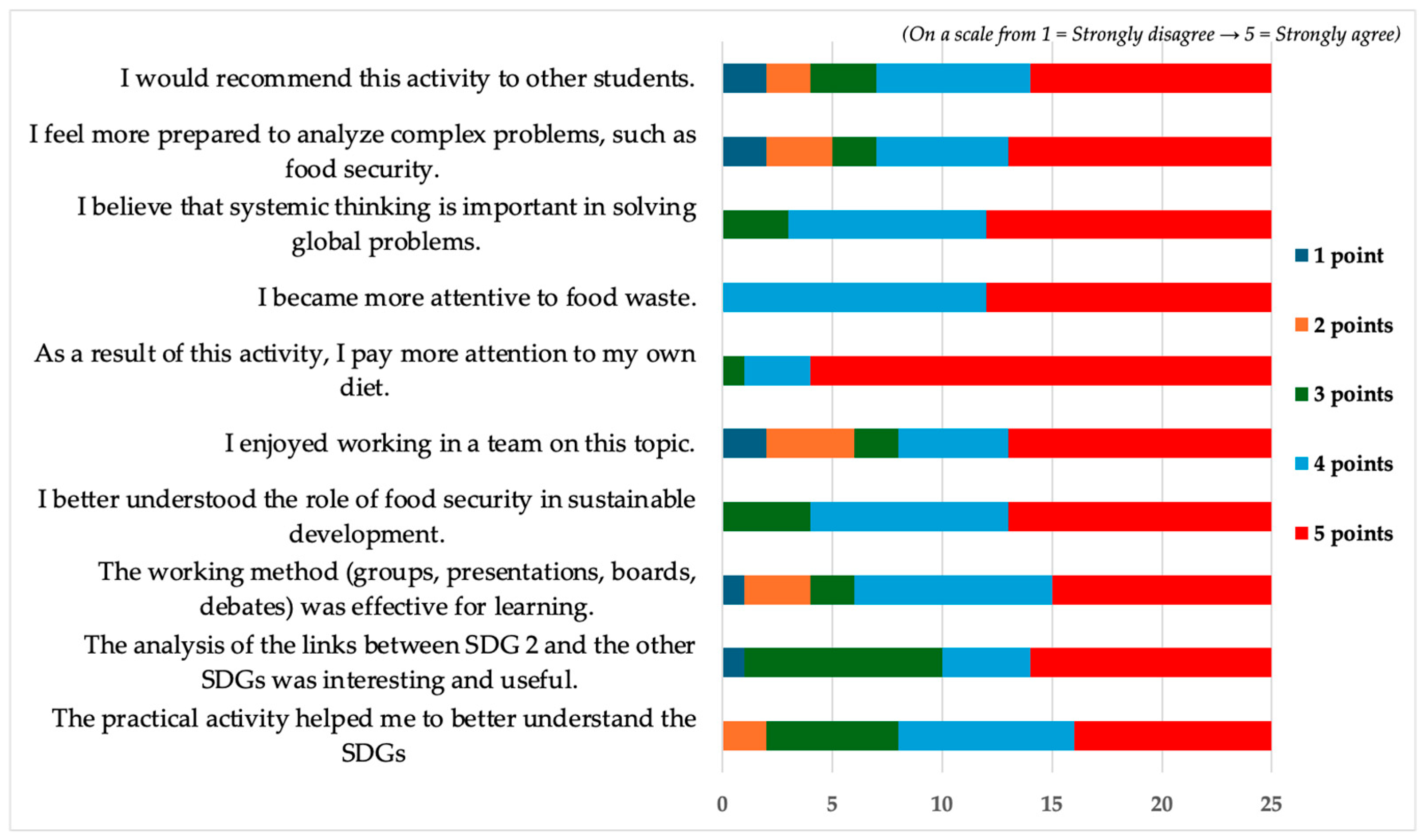

3.2.1. Student Perception Assessment – Academic Year 2023/2024

- Understanding the SDGs and their interdependencies — Most students gave scores of 4 and 5 points to the items related to understanding the Sustainable Development Goals (Item 1) and the links between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and the other SDGs (Item 2), which shows the effectiveness of the practical approach.

- Efficiency of the working method — Presentations, teamwork, flipcharts, and debates were considered effective by students (Item 3), and teamwork was appreciated (Item 5), although there is a slight variation in perceptions — which is natural for group activities.

- Impact on food awareness — The results are remarkable for the items regarding the impact on their own eating habits: 84% of students stated that they pay more attention to their personal diet (Item 6), and 100% of them stated that they are more attentive to food waste (Item 7), giving a maximum score of 4 or 5.

- Developing systemic thinking — Items related to systemic thinking (Item 8) and the ability to analyze complex issues such as food security (Item 9) were predominantly evaluated with high scores.

- Recommendation of the activity — Item 10 shows that most students would recommend this activity to other colleagues, which confirms the perceived didactic value of the approach (Figure 18).

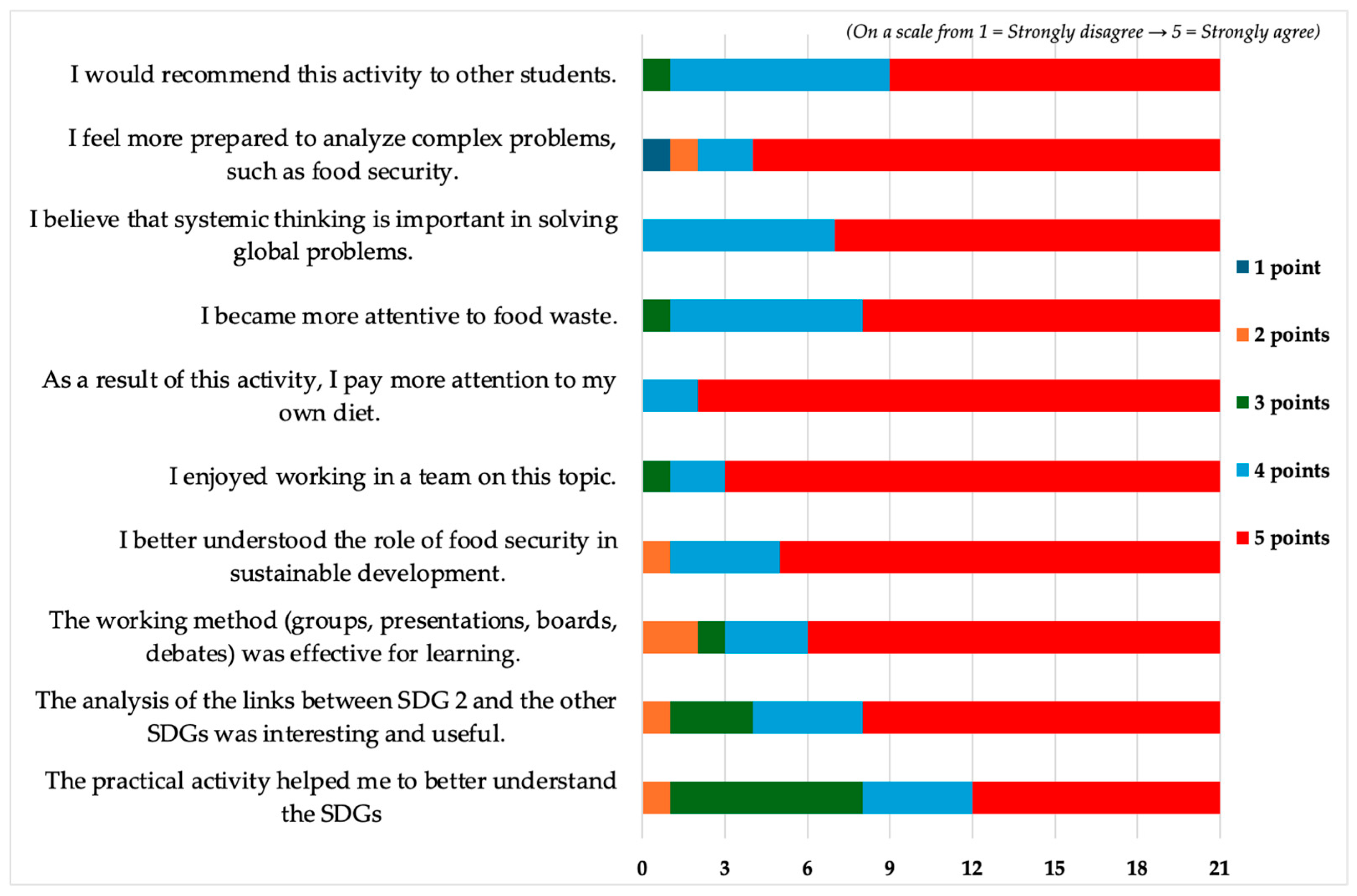

3.2.2. Student Perception Assessment – Academic Year 2024/2025

- Increased understanding of the SDGs and interdependencies — Students considered that the practical activity helped them better understand the Sustainable Development Goals (Item 1) and the links between SDG 2: Zero Hunger and the other SDGs (Item 2), with scores of 4 and 5 points being the most common.

- Efficient and attractive working method — Presentations, teamwork and making charts were very well appreciated (Item 3), and teamwork was an extremely valuable element for students (Item 5), with 18 of them giving it maximum points.

- Concrete impact on eating behavior — It is impressive that 19 students stated that, following the activity, they pay more attention to their personal diet (Item 6), and 20 students are more attentive to food waste (Item 7).

- Formation of systemic thinking — Items related to systemic thinking (Item 8) and the ability to analyze complex problems (Item 9) were evaluated almost exclusively with 4 or 5 points.

- High degree of recommendation — Regarding Item 10, most students stated that they would recommend this activity to other colleagues, which confirms the positive impact felt (Figure 19).

3.2.3. Comparative Analysis of Student Perception in the Two University Years

- -

- increasing understanding of the SDGs;

- -

- developing systemic thinking and the ability to analyze the interdependencies between SDGs;

- -

- positive impact on one’s own eating behaviors (increased attention to diet and food waste);

- -

- appreciation of the working method based on practical analysis, debates and team collaboration.

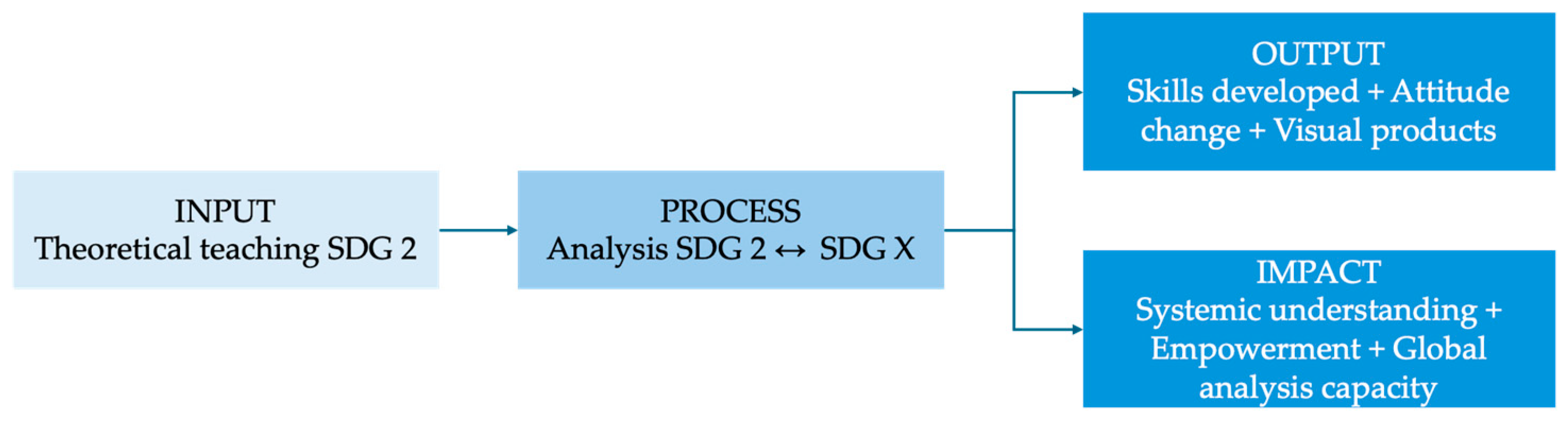

3.3. General Model of Educational Method

- Active and participatory learning.

- Systemic and multidimensional analysis of global problems.

- Collaborative work and reasoned debates.

- Creativity and freedom of expression.

- Connecting theory with practical examples and case studies.

- Stimulating social and food responsibility.

- Theoretical introduction to the issue of SDG 2: Zero Hunger and the 17 SDGs;

- Formation of work teams and allocation of specific tasks;

- Documenting, analyzing, and arguing the identified interdependencies;

- Creating visual products (presentations, posters, charts);

- Oral presentation and support of ideas during the seminar;

- Debates, collective reflection, and feedback provided by peers and the teacher;

- Final assessment, integrating both theoretical testing and practical performance assessment.

- -

- Output – visible, immediate results: development of skills, creation of visual products, changes in attitude manifested during the activity.

- -

- Impact – profound and lasting results: developing systemic thinking, food and social responsibility, increasing the capacity to analyze and solve global problems.

- In-depth understanding of the SDGs and the interdependencies between them.

- Critical and systemic thinking.

- Ability to analyze complex problems.

- Awareness of the impact of one’s diet.

- Increasing attention to food waste.

- Communication and teamwork skills.

- Creativity in visual and conceptual expression.

4. Discussion

4.1. Originality of the Teaching Method

4.2. Transferability of the Method

- -

- in other universities,

- -

- within other study programs,

- -

- in non-formal educational or continuing education contexts.

4.3. How it Supports Education for Food Ethics and Sustainability Literacy

- -

- increased attention to diet,

- -

- reducing food waste,

- -

- understanding one’s own role in the global food chain.

4.4. The Connection of the Method with the Educational Needs of the Future

- Systems thinking and the ability to understand global interdependencies;

- Literacy for Sustainability (sustainability literacy);

- Food ethics and responsibility towards resources;

- Communication, argumentation and collaboration skills;

- Creativity and visual expression;

- Understanding the complexity of food systems.

4.5. Limits and Future Development Prospects

- expanding its application in international contexts, with students from other cultures and educational backgrounds;

- using the method starting from other SDGs, depending on the specifics of the discipline

- integrating digital methods, interactive platforms or multimedia resources to facilitate analyses;

- conducting longitudinal research to investigate the long-term effects on students’ dietary and environmental behaviors;

- developing a guide to good educational practices, including detailed methodology and examples of results from student work.

5. Conclusions

- -

- environmental ethics;

- -

- ethics towards natural resources;

- -

- ethics towards other people, regardless of space, culture, or generation;

- -

- ethics towards the human condition itself, in its fragility and dignity;

- -

- ethics towards those who will come after us—future generations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: a roadmap. UNESDOC, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. (2024). The SDGs and the UN Summit of the Future. Sustainable Development Report 2024; Paris: SDSN, Dublin: Dublin University Press. [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Drumm, E. (2023). Implementing the SDG Stimulus. Sustainable Development Report 2023; Dublin: Dublin University Press. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Education Summit: Final Report; 2022; https://www.un.org/en/transforming-education-summit.

- SDSN; Accelerating Education for the SDGs in Universities: A guide for universities, colleges, and tertiary and higher education institutions; New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), 2020.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. Rome, FAO, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Guang-Wen, Z.; Murshed, M.; Siddik, A.B.; Alam, M.S.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Mahmood, H. Achieving the objectives of the 2030 sustainable development goals agenda: Causalities between economic growth, environmental sustainability, financial development, and renewable energy consumption. Sustainable Development 2023, 31(2), 680-697. [CrossRef]

- Lile, R.; Ocnean, M.; Balan, I.M.; KIBA, D. Challenges for Zero Hunger (SDG 2): Links with Other SDGs. In Transitioning to Zero Hunger, MDPI 2023, pp.9-66. [CrossRef]

- Dörgő, G.; Sebestyén, V.; Abonyi. J. Evaluating the Interconnectedness of the Sustainable Development Goals Based on the Causality Analysis of Sustainability Indicators. Sustainability 2018, 10(10): 3766. [CrossRef]

- Balan, I.M.; Trasca, T.I. Reducing Agricultural Land Use Through Plant-Based Diets: A Case Study of Romania. Nutrients 2025, 17(1):175. [CrossRef]

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural–urban continuum. Rome, FAO, 2023. [CrossRef]

- United Nations (2023). Global Sustainable Development Report 2023, Times of crisis, times of change: Science for accelerating transformations to sustainable development; (United Nations, New York; https://sdgs.un.org/gsdr/gsdr2023.

- Dube, K.; Booysen, R.; Chili, M. Redefining Education and Development: Innovative Approaches in the Era of Sustainable Goals. In Innovative Approaches to Education and Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Väänänen, N.; Kettunen, H.; Posti, A.; Turunen, V. Sustainable Development Agenda 2030 Goals and Early Childhood Education—A Case Study of Project-Based Learning in Higher Education. In Higher Education for Sustainability: Strategies and Cases; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 33–45. [CrossRef]

- Petroman, I.; Caliopi Untaru, R.; Petroman, C.; Orboi, M.D.; Banes, A.; Marin, D.; Balan, I.; Negrut, V. The influence of differentiated feeding during the early gestation status on sows prolificacy and stillborns. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2011; 9, pp. 223–224. [CrossRef]

- Dudek, H.; Myszkowska-Ryciak. J. Food Insecurity in Central-Eastern Europe: Does Gender Matter? Sustainability 2022; 14(9):5435. [CrossRef]

- Trasca, T.I.; Balan I.M.; Fintineru, G.; Tiu, J.V., Mateoc-Sirb, N.; Rujescu, C.I. Sustainable Food Security in Romania and Neighboring Countries—Trends, Challenges, and Solutions. Foods 2025, 14(8):1309. [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.; Brandli, L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.; Ruiz Vargas, V.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and Sustainability Teaching at Universities: Falling Behind or Getting Ahead of the Pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [CrossRef]

- Bespalyy, S.; Alnazarova, G.; Scalcione, V.N.; Vitliemov, P.; Sichinava, A.; Petrenko, A.; Kaptsov, A. Sustainable Development Awareness and Integration in Higher Education: A Comparative Analysis of Universities in Central Asia, South Caucasus, and the EU. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 346. [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, A.; Beasy, K.; Fiedler, T.; Mann, A.; Morrison, B.; Towle, N.; Wood, G.; Doyle, R.; Peterson, C.; Bettiol, S. Common Experiences and Critical Reflections: Embedding Education for Sustainability in Higher Education Curricula Across Disciplines. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for the Future? Critical Evaluation of Education for Sustainable Development Goals. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 51, 280–291. [CrossRef]

- Gencia, A.D.; Balan, I.M. Reevaluating Economic Drivers of Household Food Waste: Insights, Tools, and Implications Based on European GDP Correlations. Sustainability 2024, 16(16):7181. [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Tripathi, S.K.; Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.D.; Giné-Garriga, R.; Orlovic Lovren, V.; Willats, J. Using the Sustainable Development Goals Towards a Better Understanding of Sustainability Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 26, 179–190. [CrossRef]

- Shulla, K.; Filho, W.L.; Lardjane, S.; Sommer, J.H.; Borgemeister, C. Sustainable Development Education in the Context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 458–468. [CrossRef]

- Zugravu, C.A.; Pogurschi, E.N.; Patrascu, E.; Iacob, P.D.; Nicolae, C. Attitudes toward food additives. A pilot Study. Annals of the University Dunarea de Jos of Galati Fasc. VI-Food Technology 2017, 4(1), 50-61.

- Mateoc Sirb, N.; Otiman, P.I.; Mateoc, T.; Salasan, C.; Balan, I.M. Balance of Red Meat in Romania—Achievements and Perspectives. In From Management of Crisis to Management in a Time of Crisis. In Proceedings of the 5th Review of Management and Economic Engineering International Management Conference, Cluj Napoca, Romania, 2016, pp. 388–394. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000385997200048.

- Bali Swain, R.; Yang-Wallentin, F. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: Predicaments and Strategies. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 27, 96–106. [CrossRef]

- MDPI Books. N.d. Book Series Transitioning to Sustainability ISSN2624-9324 (Print) ISSN2624-9332 (Online). https://www.mdpi.com/books/book-series/1152-transitioning-to-sustainability (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- UNESCO. n.d. Education for sustainable development Learning to act for people and planet. https://www.unesco.org/en/sustainable-development/education (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Koo, M.; Yang, S.-W. Likert-Type Scale. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 18. [CrossRef]

- Salasan, C.; Balan, I.M. The environmentally acceptable damage and the future of the EU’s rural development policy. In Economics and Engineering of Unpredictable Events 2022, pp. 49-56. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Pogurschi, E.N.; Munteanu, M.; Nicolae, C.G.; Marin, M.; Zugravu, C.A. Rural-urban meat consumption in Romania. Sc Papers Series D. Animal Sc. 2018, 61(2), pp. 111-115.

- Trasca, T.I.; Groza, I .; Rinovetz, A.; Rivis, A.; Radoi, B.P. The study of the behaviour of polyetetrafluorethylene dies for pasta extrusion comparative with bronze dies, Rev Mat Plast 2007; 44(4), pp. 307-309.

- Cripps, K.; Thondre, P.S. An Introduction to SDG2 Zero Hunger, In Higher Education and SDG2: Zero Hunger (Higher Education and the Sustainable Development Goals), Eds. Cripps, K. and Thondre, P.S.; Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, 2024, pp. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2016. Final List of Proposed Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/11803Official-List-of-Proposed-SDG-Indicators.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Rinovetz, A.; Rinovetz, Z.A.; Mateescu, C.; Trasca, T.I.; Jianu, C.; Jianu, I. Rheological characterisation of the fractions separated from pork lards through dry fractionation. Journ Food Agr Env 2011; 9(1); pp. 47-52.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024. Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO: Rome, Italy, 2024. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd1254en. [CrossRef]

- Trasca, T.I.; Ocnean, M.; Gherman, R.; Lile, R.A.; Balan, I.M.; Brad, I.; Tulcan, C.; Firu Negoescu, G.A. Synergy between the Waste of Natural Resources and Food Waste Related to Meat Consumption in Romania. Agriculture 2024, 14(4):644. [CrossRef]

- European Institute of Romania. 2023. Food Security in Romania and the European Union. Challenges and Perspectives. Study carried out within the SPOS 2022 project. Bucharest: European Institute of Romania. https://ier.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Studiul-1_SPOS-2022_Securitatea-alimentara_Final.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Romanian Academy, Presidential Commission for Public Policies for the Development of Agriculture. National Strategic Framework for the Sustainable Development of the Agri-Food Sector and Rural Space in the Period 2014–2020–2030 2013. https://acad.ro/forumuri/doc2013/d0701-02StrategieCadrulNationalRural.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Larson, P.D.; Larson, N.M. The Hunger of Nations: An empirical study of inter-relationships among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Journal of Sustainable Development 2019, 12(6), pp. 39-47. [CrossRef]

- García-Juanatey, A.; De Vita, I. Challenges to SDG 2 on Zero Hunger: Becoming aware of the vulnerabilities of the global food system. In Geoeconomics of the Sustainable Development Goals; 2025; pp. 294-309. Routledge.

- Allahyari, M.; Poursaeed, A; (2020). Sustainable Agriculture: Implication for SDG2 (Zero Hunger). In Eds.: Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T. Zero Hunger. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, D.R.; Saxena, A.D.; Tupkar, N.J.; Karim, F.A.; Irving, A.L. 2025. Understanding Sustainable Development Goal 2: Zero Hunger. In Smart Technologies for Sustainable Development Goals, 2025, pp. 20-41, CRC Press.

- Otekunrin, O.A. Countdown to the 2030 global Goals: a bibliometric analysis of research trends on SDG 2–zero hunger. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science Journal 2023, 11(3), pp. 1338-1362. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, B.; Rundshagen, V. Paradigm shift to implement SDG 2 (end hunger): A humanistic management lens on the education of future leaders. The international journal of management education 2020, 18(1), p. 100368. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Dima, A.M. Mapping the Sustainable Development Goals Relationships; Sustainability 2020, 12, 3359. [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S.J.; Saleem, M.; Misra, R.; Nguyen, N.; Mason, J. Reducing SDG complexity and informing environmental management education via an empirical six-dimensional model of sustainable development, Journal of Environmental Management 2023; 344, 118328. [CrossRef]

- Farquharson, C.; McNally, S.; Tahir, I. Education Inequalities. Oxf. Open Econ. 2024, 3 (Suppl. 1), i760–i820. [CrossRef]

- Allahyari, M.S.; Sadeghzadeh, M. Agricultural Extension Systems Toward SDGs 2030: Zero Hunger. In: Eds.: Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T. Zero Hunger. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer 2020, Cham. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2024. Evaluation of Cohesion Policy in the Member States. Available online: https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/stories/s/suip-d9qs (accessed on 1 April 2025). (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Grigoroiu, M.C.; Țurcanu, C.; Constantin, C.P.; Tecău, A.S.; Tescașiu, B. The Impact of EU-Funded Educational Programs on the Socio-Economic Development of Romanian Students: A Multidimensional Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17(5):2057. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Paredes, G.X.; Juarez-Alvarez, C.R.; Cuya-Zevallos, C.; Mamani-Machaca, E.S.; Esquicha-Tejada, J.D. Enhancing Social Innovation Through Design Thinking, Challenge-Based Learning, and Collaboration in University Students. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10471. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Guo, L. Constructing the Early-Stage Framework of Cultural Identity Enlightenment in Kindergarten Heritage Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9402. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2022. Sustainable development in the European Union. Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context. 2022 Edition. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/15234730/15242025/KS-09-22-019-EN-N.pdf/a2be16e4-b925-f109-563c-f94ae09f5436?t=1667397761499 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- European Commission. EU actions to enhance global food security. N.d. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/eu-actions-enhance-global-food-security_en (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Greben, S.; Parashchenko, L.; Salii, B. Comparative Analysis of Funding of University Education in EU Countries. Public Adm. Law Rev. 2024, 1, pp. 28–42. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Ames, A.J.; Myers, N.D. A review of meta-analyses in education: Methodological strengths and weaknesses. Review of Educational Research 2012, 82(4), pp. 436-476. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. S. The advantages and disadvantages of using qualitative and quantitative approaches and methods in language “testing and assessment” research: A literature review. Journal of education and learning 2016, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- Salasan, C.; Balan, I. Suitability of a quality management approach within the public agricultural advisory services. Quality-Access to Success 2014; 15(140); pp. 81-84. https://scholar.googleusercontent.com/scholar?q=cache:ne3Z9W6DjrkJ:scholar.google.com/&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5.

- Petroman, I.; Untaru, R.C.; Petroman, C.; Orboi, M.D.; Băneș, A.; Marin, D.; Bălan, I.; Negruț, V. 2011. The influence of differentiated feeding during the early gestation status on sows prolificacy and stillborns.

- Schmidt, A.; Smedescu, D.; Mack, G.; Fintineru, G. Is there a nitrogen deficit in Romanian agriculture? AgroLife Sc J 2017, 6(1).

- Vlad, I.M.; Butcaru, A.C.; Fintineru, G.; Badulescu, L.; Stanica, F.; Toma, E. Mapping the Preferences of Apple Consumption in Romania; Horticulturae 2023, 9(1), 35. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). 2025. Hunger and Food Insecurity. https://www.fao.org/hunger/en.

- Cripps, K. and Thondre, P.S. (Eds.) Higher Education and SDG2: Zero Hunger (Higher Education and the Sustainable Development Goals), Emerald Publishing Limited 2024, Leeds, pp. 191-202. [CrossRef]

- Kniepert, M.; Fintineru, G.; Blockchain technology in food-chain management – an institutional economic perspectivfe; Sc. Papers. Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and rural devlopment 2018, 18(3), pp. 183-202.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).