1. Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM), classified as CNS WHO grade 4 [

1], is the most aggressive and common primary brain tumor in adults. Despite advances in multimodal treatment strategies, including surgical resection followed by radiation and chemotherapy according to the Stupp protocol, the prognosis for patients remains poor, with a median survival of approximately 14–16 months [

2,

3]. Tumor recurrence is almost inevitable and presents significant challenges for both diagnosis and treatment [

4]. One of the critical hurdles in managing recurrent GBM is distinguishing true tumor recurrence from treatment-induced changes, such as radiation necrosis or pseudoprogression [

5,

6]. Accurate diagnosis is essential for guiding subsequent therapeutic decisions, as unnecessary treatments or interventions can significantly impact patient outcomes and quality of life.

18-fluoride-fluoro-ethyl-tyrosine positron emission tomography (FET-PET) imaging has emerged as a promising tool to boost diagnostic accuracy by providing metabolic insights that complement conventional MRI, particularly when MRI findings are inconclusive [

7,

8,

9,

10]. FET-PET provides metabolic and molecular information that complements conventional anatomical imaging modalities such as MRI. This is particularly valuable in cases where MRI findings are inconclusive due to overlapping features of recurrence and treatment-related effects [

11,

12]. While prior studies have suggested the utility of FET-PET in identifying recurrent GBM, its diagnostic performance, specifically in terms of sensitivity and specificity, remains under debate. Furthermore, the role of PET imaging in routine clinical practice has yet to be fully established, particularly in consideration of its significant economic burden on health care providers.

This retrospective, single-center study aims to evaluate the role of FET-PET imaging in detecting glioblastoma recurrence by analyzing its diagnostic accuracy. Ultimately, this study seeks to contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the clinical utility of FET-PET imaging in glioblastoma recurrence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort

All patients included in the study had available formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor specimens and underwent surgical resection followed by adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy according to the Stupp protocol [

2]. Inclusion criteria mandated that the tumor resection was performed at our institution, that a minimum follow-up period of three months was available, and that the diagnosis of GBM was confirmed by histopathological examination. Patients were excluded if a definitive tumor recurrence was not confirmed by histopathology, if they had any other grade 4 tumor harboring an isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutation, or if they did not undergo PET imaging at the time of suspected tumor recurrence.

2.2. Study Design

This is a retrospective, single-center study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of FET-PET imaging in detecting GBM recurrence. For the primary outcome, FET-PET imaging findings obtained during clinical suspicion of recurrence were compared with histopathological results from re-resection or biopsy, enabling the calculation of sensitivity and specificity. For a stratified analysis, three groups were examined to calculate sensitivity and specificity: in the first group (1), only cases with clearly defined FET-PET results—either positive or negative—aligned with histopathologically confirmed recurrence or its exclusion were included, with ambiguous cases excluded. In the second group (2), ambiguous cases were classified as negative, whereas in the third group (3), ambiguous cases were assigned to the positive group. This approach allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of ambiguous PET findings on diagnostic accuracy. Secondary outcome parameters included stratification by MGMT status, time to recurrence, survival data, as well as consecutive rates of surgery or other forms of treatment.

2.3. Statistics

Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and R. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of PET imaging in detecting glioblastoma recurrence. The results were presented as percentages, providing insight into the diagnostic performance of FET-PET in distinguishing true tumor recurrence from treatment-related changes. To assess the significance of molecular correlations, Fisher’s Exact Test was applied to compare the sensitivity and specificity of FET-PET in relation to MGMT promoter methylation status. This statistical approach was chosen due to the categorical nature of the data and the limited sample size in molecular subgroups.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from the local ethics committee prior to the initiation of the study (approval number 740/20). Given the retrospective nature of the research, the ethics committee granted a waiver for patient informed consent.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Cohort

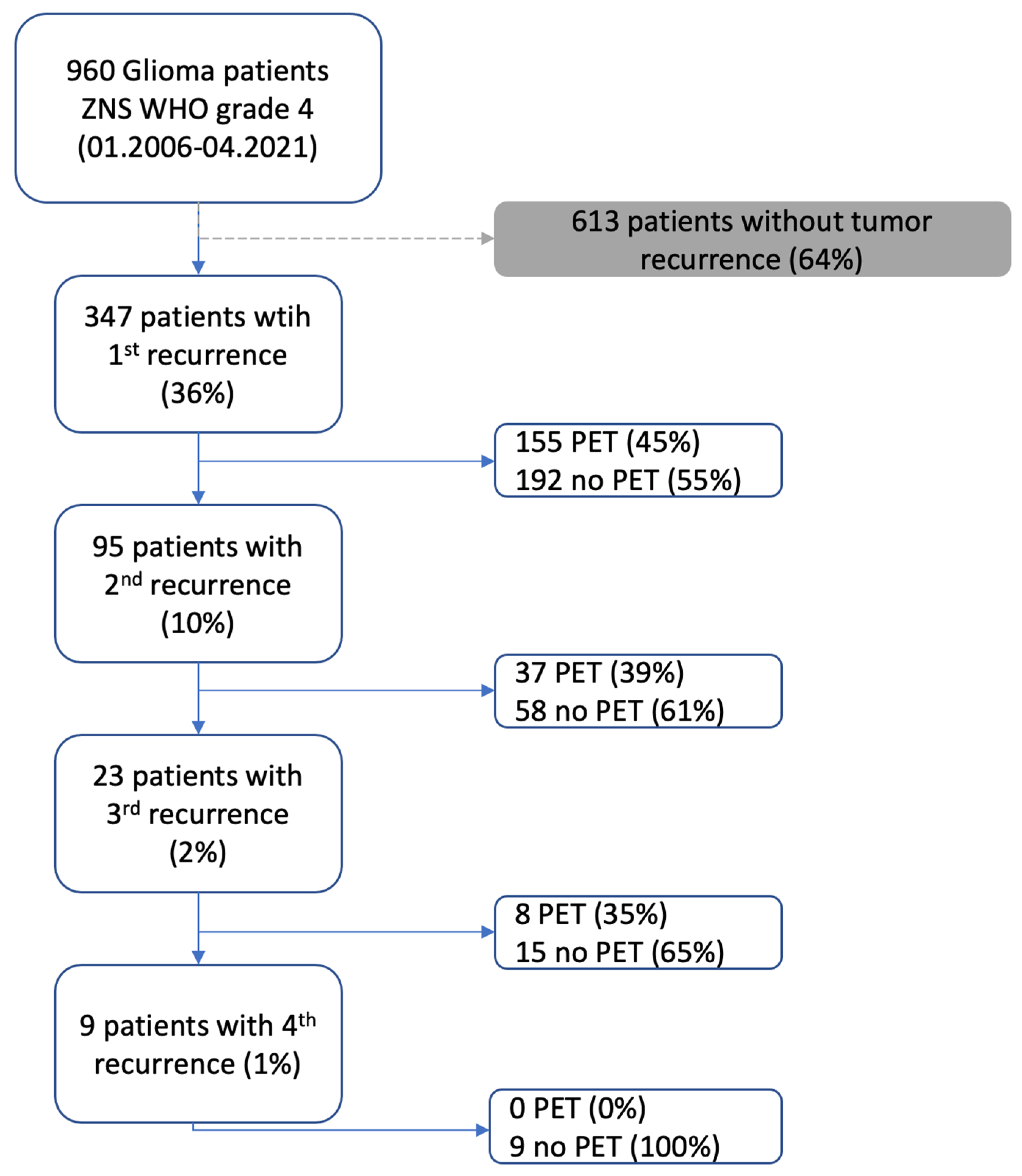

Between 2006 and 2021, a total of 960 glioblastoma (GBM) patients were screened. Of these, 613 patients were excluded due to a lack of documented tumor recurrence. This resulted in a study cohort of 347 patients (36%) with a first recurrence. Among them, 155 patients (45%) underwent PET imaging, while 192 (55%) did not. A second recurrence was documented in 95 patients (10%), with 37 patients (39%) receiving PET imaging and 58 (61%) without PET. A third recurrence was recorded in 23 patients (2%), of whom 8 (35%) underwent PET imaging, whereas 15 (65%) did not. For patients experiencing a fourth recurrence (9 patients; 1%), none underwent PET imaging (

Figure 1).

The study cohort consisted of 347 patients, including 124 women (36%) and 223 men (64%). The age at diagnosis ranged from 10 to 90 years, with a median age of 57 years. Overall survival ranging from 11 to 4712 days, with a median survival of 555 days. Women had a median overall survival of 647 days, while men had a median survival of 528 days. The number of recurrence surgeries ranged from 1 to 5, with a median of 1 surgery for both genders.

3.2. First Recurrence

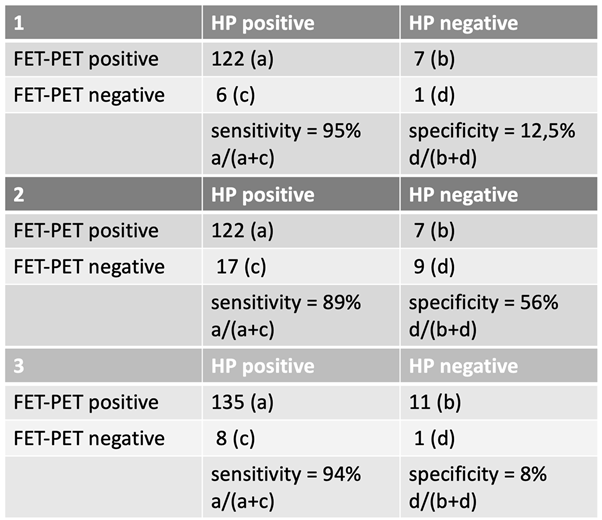

The first suspected recurrence requiring subsequent surgical intervention occurred at a median of 277 days (range: 10–3338 days) after initial diagnosis. The first FET-PET scan indicating tumor recurrence was performed at a median of 244 days (range: 0–2381 days) following completion of radiotherapy. The evaluation of FET-PET diagnostic accuracy in the first recurrence was conducted based on the three predefined groups (

Table 1).

In Group 1, only confirmed FET-PET positive or negative cases with corresponding histopathological (HP) confirmation were included. The analysis yielded a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 12.5% based on the following distribution: 122 HP-positive cases were correctly identified as FET-PET positive (a), while 6 HP-positive cases were FET-PET negative (c). Among the HP-negative cases, 7 were misclassified as FET-PET positive (b), and only 1 was correctly classified as FET-PET negative (d).

In Group 2, uncertain cases were assigned to the negative group, leading to a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 56%. Here, 122 HP-positive cases were correctly classified as FET-PET positive (a), while 17 HP-positive cases were classified as negative (c). Among the HP-negative cases, 7 were misclassified as FET-PET positive (b), whereas 9 were correctly identified as negative (d).

In Group 3, uncertain cases were counted as positive, resulting in a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 8%. In this scenario, 135 HP-positive cases were identified as FET-PET positive (a), while 8 HP-positive cases were FET-PET negative (c). Among the HP-negative cases, 11 were misclassified as positive (b), and only 1 was correctly classified as negative (d).

3.3. Second Recurrence

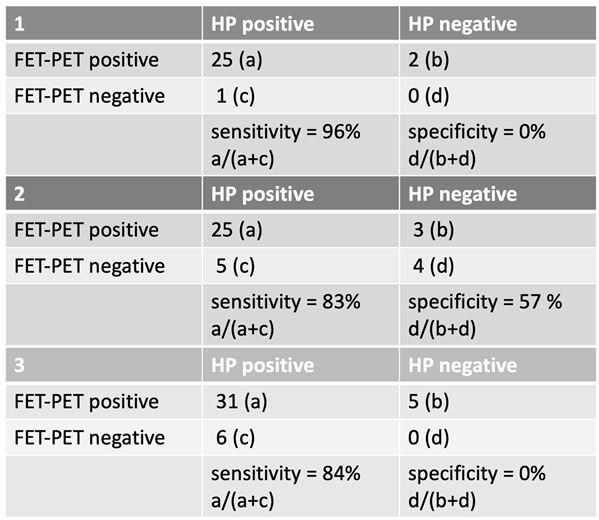

The evaluation of FET-PET imaging in the detection of a second glioblastoma recurrence followed the same classification into three groups. The second suspected recurrence occurred at a median of 975 days (range: 256–3816 days) after initial diagnosis. The corresponding FET-PET imaging in case of suspected tumor recurrence was performed at a median of 340 days (range: 35–3756 days) following the last radiotherapy. For the second glioblastoma recurrence, FET-PET imaging demonstrated a high sensitivity but variable specificity depending on case classification.

In Group 1, sensitivity was 96%, while specificity remained 0%. Among 26 HP-positive cases, 25 were correctly classified as FET-PET positive, while 2 HP-negative cases were misclassified as positive.

In Group 2, where uncertain cases were counted as negative, sensitivity decreased to 83%, while specificity improved to 57%.

In Group 3, with uncertain cases classified as positive, sensitivity was 84%, but specificity remained at 0%.

These findings indicate that FET-PET imaging retained a high sensitivity in detecting a second glioblastoma recurrence but showed substantial limitations in specificity depending on how uncertain cases were classified. Notably, specificity remained 0% in Group 1 and Group 3, highlighting the challenge of distinguishing true recurrence from treatment-related changes at this stage of disease progression.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity in second recurrence.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity in second recurrence.

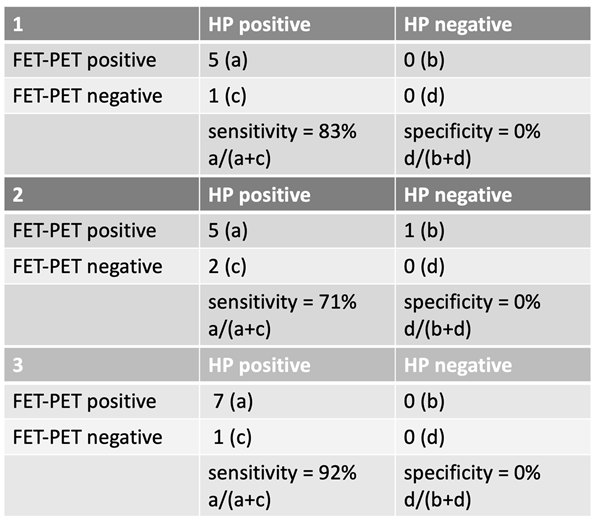

3.4. Third Recurrence

For the third glioblastoma recurrence, FET-PET sensitivity remained high, but specificity was consistently 0% across all groups. The third suspected recurrence occurred at a median of 910.5 days (range: 264–1973 days) after initial diagnosis. The corresponding FET-PET imaging was performed at a median of 159.5 days (range: 32–1005 days) following the last radiotherapy.

In Group 1, sensitivity was 83%, with 5 correctly classified HP-positive cases and 1 misclassified as negative. No HP-negative cases were correctly identified.

In Group 2, where uncertain cases were classified as negative, sensitivity dropped to 71%, but specificity remained 0%.

In Group 3, with uncertain cases counted as positive, sensitivity increased to 92%, though specificity remained 0%.

These findings reinforce that while FET-PET maintains good sensitivity for detecting a third recurrence, its specificity is extremely limited at this stage of disease progression.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity in third recurrence.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity in third recurrence.

3.5. Molecular Correlation of Specificity and Sensitivity with MGMT Status

Stratification of patients by MGMT promoter methylation status revealed no significant differences in the diagnostic performance of FET-PET. Sensitivity remained comparable between MGMT-methylated and unmethylated tumors, with p = 0.498 for the first recurrence and p = 1.0 for the second recurrence. Similarly, specificity did not differ between the molecular subtypes, with p = 1.0 for both the first and second recurrence.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate that FET-PET imaging exhibits high sensitivity for differentiating glioblastoma recurrence from pseudoprogression or therapy-induced changes, particularly during the early stages of recurrence. However, our data indicate a significant decline in sensitivity with successive recurrences, suggesting that the diagnostic challenge of differentiating true tumor regrowth from treatment-related alterations becomes increasingly difficult over time. Importantly, this study is the first to systematically evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of FET-PET across multiple recurrence resections, focusing exclusively on glioblastoma (GBM) patients. These results underscore the utility of FET-PET in the initial recurrence setting while highlighting the need for further research to optimize diagnostic strategies in later recurrences.

For the first recurrence, FET-PET demonstrated robust diagnostic performance, with sensitivities ranging from 89% to 95% across the different classification groups, suggesting that in patients with suspected first recurrence, FET-PET provides a valid means of identifying viable tumor tissue and guiding further therapeutic decisions. However, for the second recurrence, sensitivity declined, particularly when uncertain cases were categorized as negative (83% sensitivity in Group 2). This trend continued in the third recurrence, where the lowest sensitivity was observed in Group 2 (71%). These findings suggest that cumulative treatment effects, such as radiation necrosis, gliosis, and therapy-induced metabolic changes, increasingly obscure the ability of FET-PET to distinguish between tumor progression and non-tumorous changes. As a result, the risk of false-negative findings rises with each recurrence, necessitating a careful interpretation of imaging results in later-stage disease.

While sensitivity remained consistently high across all groups in our cohort, specificity was highly dependent on how uncertain cases were classified, showing the greatest increase when these cases were counted as negative.

These observations align with previous research on the diagnostic performance of FET-PET in high-grade gliomas [

13]. A large retrospective study by Singnurkar et al. found an overall sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 84% for static FET-PET parameters in detecting tumor recurrence [

14]. Similarly, Cui et al. reported pooled values of 88% sensitivity and 78% specificity across 15 studies [

15]. The most recent study also demonstrated an overall sensitivity and specificity with 91.6 and 76.9% respectively, with a diagnostic accuracy of 87.13% [

13]. These findings are consistent with our results in early recurrences, where FET-PET showed high sensitivity but limited specificity. However, our study highlights an important limitation of FET-PET in later-stage recurrences, where diagnostic accuracy declines, likely due to an increased presence of non-tumorous changes mimicking active tumor tissue.

The results from de Zwart et al. [

16], who analyzed 10 studies on FET-PET with a pooled sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 86%, further reinforce the clinical value of this imaging modality. In contrast, our study found that specificity remained consistently low across all recurrence stages, emphasizing the limited ability of FET-PET to rule out recurrence, particularly in cases with treatment-related alterations.

While previous studies have suggested that MGMT methylation status may influence recurrence patterns as detected by FET-PET, our findings indicate that the diagnostic performance of FET-PET in detecting recurrence is independent of MGMT status [

17]. MGMT promoter methylation status had no significant impact on the sensitivity or specificity of FET-PET. This aligns with findings from previous studies indicating that amino acid PET tracers, including FET, function independently of molecular tumor markers such as MGMT. Unlike contrast agents for MRIs, which rely on blood-brain barrier disruption and may be influenced by tumor microenvironment changes, FET uptake is mediated through the LAT1 transporter and reflects active glioma metabolism, regardless of MGMT status [

18,

19]. This independence makes FET-PET an attractive imaging modality for both methylated and unmethylated glioblastomas, ensuring broad applicability across patient subgroups.

As is nature of retrospective data analysis, our study cannot confer causality from the results presented herein, and the completeness and accuracy of clinical information is subject to documentation available within the hospital data systems. The lack of routinely available molecular information of patients undergoing treatment during the earlier phase of the cohort in particular limits the ability to draw conclusions about potential MGMT-related differences in later-stage recurrences.

5. Conclusions

FET-PET imaging is a highly sensitive method for detecting glioblastoma recurrence, particularly in early stages. However, sensitivity declines as the number of recurrences increases, likely due to the accumulation of treatment-related changes that complicate differentiation from active tumor tissue. The diagnostic accuracy of FET-PET is independent of MGMT promoter methylation status, making it broadly applicable across glioblastoma subtypes. Given the observed limitations, a multimodal diagnostic approach incorporating additional imaging and molecular techniques may be necessary in later-stage recurrences to optimize clinical decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: B.M., A.W., L.H.; data collection: L.H.; formal analysis, L.H., A.W., C.N., D.B., F.S.-G., I.Y., C.D.; writing—original draft preparation L.H., A.W.; writing—review and editing, L.H., A.W., C.N., D.B., F.S.-G., I.Y., C.D., B.M.; visualization L.H.; supervision A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this publication. The presented study meets the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, ethics approval was obtained, and the favorable vote was registered under the number 740/20. In this retrospective study, only patients who were already deceased at the time of the study were included. Informed consent for study participation was therefore no longer possible.

Informed Consent Statement

The need for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT for the purposes of text writing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNS |

Central nerve system |

| FET-PET |

18-fluoride-fluoro-ethyl-tyrosine positron emission tomography |

| FFPE |

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded |

| GBM |

Glioblastoma |

| HP |

Histopathology |

| MGMT |

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Louis, D.N., et al., The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol, 2021.

- Stupp, R., et al., Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med, 2005. 352(10): p. 987-96.

- Stupp, R., et al., Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Maintenance Temozolomide vs Maintenance Temozolomide Alone on Survival in Patients With Glioblastoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama, 2017. 318(23): p. 2306-2316.

- Vaz-Salgado, M.A., et al., Recurrent Glioblastoma: A Review of the Treatment Options. Cancers (Basel), 2023. 15(17).

- Jacob S Young, N.A.-A., Katie Scotford, Soonmee Cha, Mitchel S Berger, Pseudoprogression versus true progression in glioblastoma: what neurosurgeons need to know. J. Neurosurg., 2023. 139 (3): p. 748-759.

- Kruser, T.J., M.P. Mehta, and H.I. Robins, Pseudoprogression after glioma therapy: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Neurother, 2013. 13(4): p. 389-403.

- Lindsey R. Drake, A.T.H.a.Z.C., Approaches to PET Imaging of Glioblastoma. Molecules, 2020(25): p. 568.

- Wang, J., et al., The State-of-the-Art PET Tracers in Glioblastoma and High-grade Gliomas and Implications for Theranostics. PET Clinics, 2025. 20(1): p. 147-164.

- Ameya D Puranik, M.B., Nilendu Purandare, Venkatesh Rangarajan, Tejpal Gupta, Aliasgar Moiyadi, Prakash Shetty, Epari Sridhar, Archi Agrawal Indraja Dev, Sneha Shah, Utility of FET-PET in detecting high-grade gliomas presenting with equivocal MR imaging features. World Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 2019(18 (3)): p. 266-272.

- Arpita Sahu, R.M., Renuka Ashtekar, Archya Dasgupta, Ameya Puranik, Abhishek Mahajan, Amit Janu, Amitkumar Choudhari, Subhash Desai, Nandakumar G. Patnam, Abhishek Chatterjee, Vijay Patil, Nandini Menon, Yash Jain, Venkatesh Rangarajan, Indraja Dev, Sridhar Epari, Ayushi Sahay, Prakash Shetty, Jayant Goda, Aliasgar Moiyadi, Tejpal Gupta, The complementary role of MRI and FET PET in high-grade gliomas to differentiate recurrence from radionecrosis. Frontiers in Nuclear Medicine, 2023. 3.

- Bobek-Billewicz, B., et al., The use of MR perfusion parameters in differentiation between glioblastoma recurrence and radiation necrosis. Folia Neuropathol, 2023. 61(4): p. 371-378.

- Jajodia, A., et al., Combined Diagnostic Accuracy of Diffusion and Perfusion MR Imaging to Differentiate Radiation-Induced Necrosis from Recurrence in Glioblastoma. Diagnostics (Basel), 2022. 12(3).

- Puranik, A.D., et al., FET PET to differentiate between post-treatment changes and recurrence in high-grade gliomas: a single center multidisciplinary clinic controlled study. Neuroradiology, 2024.

- Singnurkar, A., R. Poon, and J. Detsky, 18F-FET-PET imaging in high-grade gliomas and brain metastases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurooncol, 2023. 161(1): p. 1-12.

- Cui, M., et al., Diagnostic Accuracy of PET for Differentiating True Glioma Progression From Post Treatment-Related Changes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Neurol, 2021. 12: p. 671867.

- de Zwart, P.L., et al., Diagnostic Accuracy of PET Tracers for the Differentiation of Tumor Progression from Treatment-Related Changes in High-Grade Glioma: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. J Nucl Med, 2020. 61(4): p. 498-504.

- Niyazi, M., et al., FET-PET assessed recurrence pattern after radio-chemotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with glioblastoma is influenced by MGMT methylation status. Radiother Oncol, 2012. 104(1): p. 78-82.

- Miyagawa, T., et al., “Facilitated” amino acid transport is upregulated in brain tumors. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 1998. 18(5): p. 500-9.

- Habermeier, A., et al., System L amino acid transporter LAT1 accumulates O-(2-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (FET). Amino Acids, 2015. 47(2): p. 335-44.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).