1. Introduction

Based on the 2021 WHO classification, the revised

definition of glioblastoma emphasizes the molecular features over traditional

histopathological criteria. Glioblastoma is now exclusively defined as an

IDH-wildtype astrocytic tumor. [1] This shift

toward molecular diagnostics is important as it reduces dependance on

morphologic features, which previously showed inconsistency in diagnosis.

Importantly, even in cases where the tumor may display lower histological

grades (grade 2 or 3), the presence of specific molecular markers, such as TERT

promoter mutations and EGFR amplification, supports the classification as

glioblastoma. [2;3]

Within the clinical spectrum of gliomas, the

prognostic panorama reveals a distinct divergence between grades. For

individuals diagnosed with low-grade gliomas (e.g., IDH Mutant), the expected

survival spans an average of 7 years. In contrast, for those with high-grade

gliomas, particularly glioblastoma with IDH Wild Type (IDH-WT), survival is

significantly shorter, typically not exceeding 14 to 16 months, despite the

employment of gold standard treatments such as gross total resection,

radiation, and chemotherapy (STUPP Protocol) [4].

The superiority of complete surgical resection over

biopsy in the treatment of gliomas is a well-established principle in

neuro-oncology. Surgical intervention, particularly gross total resection

(GTR), is central to this strategy, offering significant benefits over biopsy

alone. This approach directly reduces the volume of cancerous cells,

potentially delaying the progression of the disease. Secondly, by decreasing

the tumor burden, GTR enhances the effectiveness of adjuvant therapies, such as

chemotherapy and radiotherapy [5–7].

The choice between biopsy and surgery for

glioblastoma varies according to the tumor location, patient health, and the

intervention’s goal. Biopsy is preferred for inaccessible tumors, high surgical

risk patients, or when diagnostic clarity is needed. Multifocal or diffusely

infiltrating tumors are another example. Decisions should be patient-specific,

weighing benefits against risks [8,9].

Conversely, a growing body of clinical evidence

reveals a subset of patients who, despite only undergoing biopsy procedures,

manifest surprisingly prolonged survival rates. Such cases, in which survival

unexpectedly exceeds that of patients who have undergone complete surgical

resections, call for a reevaluation of our current understanding of

glioblastoma management and prognostication [10].

This study focused on a cohort of patients with

IDH-wildtype gliomas (grade 4, WHO 2021) who only underwent biopsy, aiming to

identify those who benefit from adjuvant treatments. The goal was to understand

survival determinants, as such patients are rarely the focus of studies and are

often mixed with those receiving multimodal treatments or having with

better-prognosis IDH-mutant gliomas.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Subject Inclusion Criteria

We performed a retrospective analysis focusing on

patients who underwent biopsy only at our institution from 2017 to 2021,

diagnosed with IDH-Wildtype glioblastomas as per the WHO 2021 classification.

Eligibility criteria for this study were patients aged over 18 years, who had

undergone a biopsy revealing an IDH wildtype GBM and had pre-operative MRI

scans. Exclusion criteria included patients who underwent tumor resection

procedures, those with a history of another intracranial tumor, patients

previously treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and those without

available clinical registry data.

2.2. Data Collection Parameters

We collected demographic details such as age at

diagnosis and sex. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was employed to

evaluate and quantify the presence of comorbidities in the patient population.

Furthermore, we recorded the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scores to measure

patients’ baseline functional status, as well as a subsequent evaluation of KPS

scores prior to the initiation of adjuvant therapy (dual-timepoint

assessment). We also incorporated the Neurologic Assessment in

Neuro-Oncology (NANO) score to evaluate neurological status. Post-operative

complications within 30 days after surgery were also meticulously recorded. We

investigated cognitive impairment reviewing data from two recognized

neuropsychological assessment tools: the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). For the purpose of this analysis,

cognitive function was stratified into three categories based on the scores

obtained from the MoCA and MMSE. Specifically, cognitive function was

considered normal for scores exceeding 26 on MoCA and 27 on MMSE. Mild

Cognitive Impairment was defined by MoCA scores ranging from 18 to 26 and MMSE

scores between 20 and 27. Severe cognitive impairment was identified by MoCA

scores below 18 and MMSE scores under 20. Patients with severe impairment of

executive function or lack of cooperation on these standardized tests were

classified within the severe cognitive impairment category. Patients with

absence data were excluded. We also recorded the use of medications like

anticoagulants, antiplatelets, antiepileptics and corticosteroids.

2.3. Genetic and Epigenetic Analysis

To identify routine genetic alterations, Polymerase

Chain Reaction (PCR) tests were conducted for IDH mutations. Pyrosequencing or

Methylation-Specific PCR (MSP) techniques determined the MGMT promoter’s

methylation status in tumor samples.

2.4. Imaging Analysis

Concerning tumor volumetry, the Brainlab Elements

software was utilized to calculate the volume of each tumor accurately, which

allowed for a standardized assessment of tumor size across the patient cohort.

For evaluating contrast uptake, we adopted a classification system based on the

extent of contrast enhancement observed in imaging studies. Contrast uptake was

categorized into three distinct levels: None, indicating no contrast

enhancement; Slight, when contrast enhancement constituted less than 15% of the

total tumor volume; and high, when it exceeded 15% of the total volume.

Regarding the tumor’s location, we documented the primary site of each lesion

based on where most of the tumor mass was located. The side of the brain

affected by the tumor (left or right hemisphere) was also noted.

2.5. Treatment Protocols

Following surgery, patients were treated according

to the following regimens: Stupp protocol, incorporating concurrent and

adjuvant radiotherapy with temozolomide chemotherapy; hypofractionated

radiotherapy plus temozolomide or monotherapy (chemotherapy or radiotherapy

alone) For recurrent tumors or when conventional options are exhausted,

off-label use of bevacizumab is considered. All therapeutic decisions,

including the adoption of standard and alternative treatment protocols, are

deliberated upon in a multidisciplinary neuro-oncology tumor board. All

treatment approaches were documented carefully.

2.6. Outcome Measures

The study’s main outcomes were Overall Survival

(OS) and Progression-Free Survival (PFS), measured from the time of diagnosis

to death from any cause or to disease progression/death, respectively. These

outcomes were analyzed in relation to patient characteristics to identify

significant prognostic factors.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 29.0.

Descriptive statistics are presented as means and standard deviations for

continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical

variables. Survival times are presented as medians and interquartile ranges.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regressions were performed to assess

associations with overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). The

assumptions of Cox proportional hazards were verified using log-minus-log

plots, which showed parallel curves. The effect size was measured as the hazard

ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals. Screening for entry into multivariate

Cox regression was based on a p-value < 0.10. Kaplan-Meier analysis with

stratification was used to compare adjuvant treatment groups (yes vs. no).

Variables for adjustment/stratification were Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS)

≥70 and age ≥72. The decision to select the age cut-off was based on a heatmap

assessment. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between OS

and any adjuvant treatment, adjusted for KPS ≥70 or age ≥72.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

This research adhered to the ethical guidelines

established by our institutional review board, in alignment with the principles

set forth in the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its subsequent amendments. Given

the retrospective design of our study, the requirement for informed consent was

waived.

3. Results

The pre-operative demographics and clinical

features of the study cohort are summarized in

Table 1. A total of 99 patients diagnosed with glioblastoma were included,

with a male predominance (67.7%). The mean age at diagnosis was approximately

65.5 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 10.9 years.

The reasoning behind the use of biopsy as a

diagnostic tool in these patients was mostly the location of the tumor in

eloquent areas of the brain not deemed surgically accessible or safe (46.5%),

as well as the presence of multifocal lesions (45.5%), with a minority of

patients performing biopsy due to the need for differential diagnosis (6.1% of

the cases). An examination of the postoperative complications following biopsy

reveals that a significant majority of the patient cohort (89.9%) did not

experience any complications. The most common post-operative complications

reported were hemorrhage and neurologic deficit, totaling 10.1% of patients.

The cohort’s comorbidity burden, assessed by the

CCI, averaged 2.7 (SD 1.5). Pre-operative functional status, measured by the

KPS score, was relatively preserved with a mean score of 72.2 (SD 17.5). A

decline was observed in the KPS scores after surgery, with a post-operative

mean of 65.7 (SD 19.8). Neurological functionality, as measured by the NANO

score, had a mean score of 3.1 (SD 1.9). Cognitive function varied within the

patient group, with 37.4% presenting with normal cognitive function, 47.5% with

mild cognitive impairment, and 15.2% with severe cognitive impairment.

The medication profile of the cohort included a

small proportion of patients on anticoagulants (6.1%) and antiplatelets

(12.1%), with the vast majority receiving corticosteroids (99.0%). Tumors

predominantly presented as a focal lesion in 52.5% of cases, while the

remainder had multifocal disease. MGMT methylation status was positive in 13.1%

of the cases. The mean tumor volume was 23.5 cm³ (SD 20.2 cm³). In terms of

tumor appearance, most cases (79.8%) had a cystic component, with a high

proportion showing significant contrast enhancement (≥ 15% contrast uptake) in

imaging studies. A minority displayed homogeneous (7.1%) or infiltrative

(13.1%) features. Regarding tumor location, the majority were found in the

intrinsic/midline structure of the brain (49.5%), with other locations

including the frontal (18.2%), parietal (13.1%), temporal (13.1%), occipital

(5.1%), and cerebellar (1.0%) regions. Tumors were almost evenly distributed

between the left (46.5%) and right (36.4%) hemispheres, with a smaller number

diffusely spread (17.2%).

In this study, only 8 of the 99 patients survived

beyond 24 months. Among these the median PFS was approximately 17.12 months.

The mean age at diagnosis was 59.06 years, with a predominance of male patients

(75%). The average CCI was 1.875. The cohort revealed a high functional status,

with a KPS score of 86, maintained both preoperatively and postoperatively

before the adjuvant therapy. The median NANO score was 1.375. A significant

proportion, of the patients (75%) received treatment (Stupp Protocol), and

bevacizumab was administered to 50% of the patients. Methylation of the MGMT

promoter was observed in only 25% of these cases.

3.1. Treatment Regimens Administered Post-Biopsy

Following biopsy, the subsequent treatment

approaches adopted for the cohort are described in

Table 2. A subset of patients (24.2%) did not

receive any adjuvant treatment post-surgery, while most patients (75.8%)

underwent some form of adjuvant therapy. One-third of the patients (33.3%) were

treated according to the Stupp protocol. hypofractionated radiotherapy plus TMZ

was done in 37.4% of patients. Bevacizumab was administered to 13.1% of the

patients.

Table 3 and

Table 4

show univariate and multivariate results for associations with PFS and OS.

Median PFS was 3.6 months with interquartile range (IQR) of 1.8 to 5.9, minimum

of 4 days and maximum of 52 months. Median OS was 6.0 months with interquartile

range of 3.6 to 10.7, minimum of 4 days and maximum of 52 months.

3.2. Uni and Multivariate Associations with PFS

In the univariate analysis, significant factors associated with PFS included age at diagnosis (HR=1.03, p=0.006), CCI (HR=1.23, p=0.003), pre-surgery KPS (HR=0.98, p=0.001), and pre-adjuvant KPS (HR=0.98, p<0.001) [

Table 3]. The presence of mild cognitive impairment (HR=1.91, p=0.005) and severe cognitive impairment (HR=2.18, p=0.014) was also significantly associated with worse PFS, as well as multifocality (HR=1.57, p=0.032). The Stupp Protocol (HR=0.45, p<0.001) and Bevacizumab (HR=0.52, p=0.029*) appeared beneficial. The employment of adjuvant treatment showed a strong association with improved PFS (HR=0.33, p<0.001). There was a notable difference in outcomes depending on whether there was uptake of the contrast agent or not. Both the presence (HR 3.99, p=0.021) and absence (HR 0.7, p=0.014) of contrast uptake appeared related to PFS scores in univariate analysis.

Multivariate analysis-maintained significance for pre-adjuvant KPS (HR=0.97, p=0.009) and the presence of mild cognitive impairment (HR=2.22, p=0.014). The absence of contrast uptake remained significantly associated with higher PFS scores (HR=0.68, p=0.040).

3.3. Uni and Multivariate Associations with OS

Univariate analysis highlighted age (HR=1.03, p=0.004), CCI (HR=1.21, p=0.008), pre-surgery KPS (HR=0.97, p<0.001), and pre-adjuvant KPS (HR=0.98, p<0.001) as significantly associated with OS [

Table 4]. Severe cognitive impairment (HR=2.28, p=0.009) and multifocal status remained negative predictors of OS (HR=1.60, p=0.023). Treatment with the Stupp Protocol (HR=0.41, p<0.001) and Bevacizumab (HR=0.34, p=0.001) correlated with better OS. The implementation of any adjuvant treatment was highly beneficial (HR=0.14, p<0.001). The absence of contrast uptake also revealed a strong association with OS (HR=4.28, p=0.030).

Multivariate analysis highlighted the Stupp Protocol (HR=0.66, p=0.248) and Bevacizumab (HR=0.27, p=0.002), with the latter remaining significant. Adjuvant treatment showed a strong multivariate association (HR=0.21, p<0.001). The absence of contrast uptake maintained a strong significant association with OS in multivariate analysis (HR=0.7, p=0.015).

We also studied the association of any adjuvant treatment with survival outcome, considering 3 months as threshold. Among the study participants, 77 (77.8%) patients survived beyond the three-month threshold, with this higher proportion of survival significantly associated with the administration of any adjuvant treatment (p < 0.001). Out of the 22 patients that survived less than 3 months, 8 (36.4%) were treated with any adjuvant treatment. Within the 77 patients that survived longer than 3 months, 15 (19%) had KPS < 70. Within the 22 patients that did no survived after 3 months, 11(50%) had KPS < 70. The proportion of patients among survivors longer than 3 months with KPS ≥ 70 was 90.3% and for KPS < 70 was 73.3%.

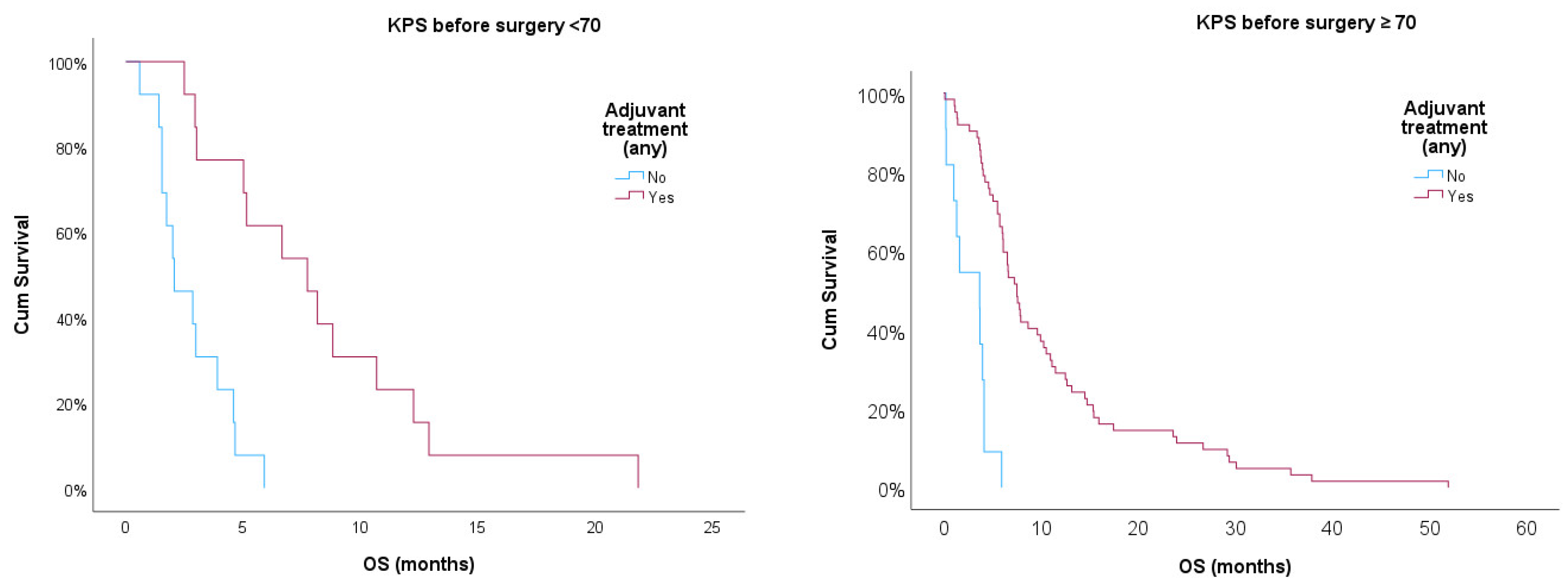

Additionally, we used Kaplan-Meier curves to compare OS for patients treated or non-treated with any adjuvant therapy, also adjusting for KPS ≥ 70. Log-rank test showed statistical significance for treated vs. non-treated patients (p<0.001) after adjusting for KPS ≥ 70. Treated patients showed better prognosis in both strata, but those with KPS ≥ 70 had a better prognosis when compared with patients with KPS < 70 (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for treated and non-treated patients any adjuvant therapy stratified for KPS ≥ 70.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for treated and non-treated patients any adjuvant therapy stratified for KPS ≥ 70.

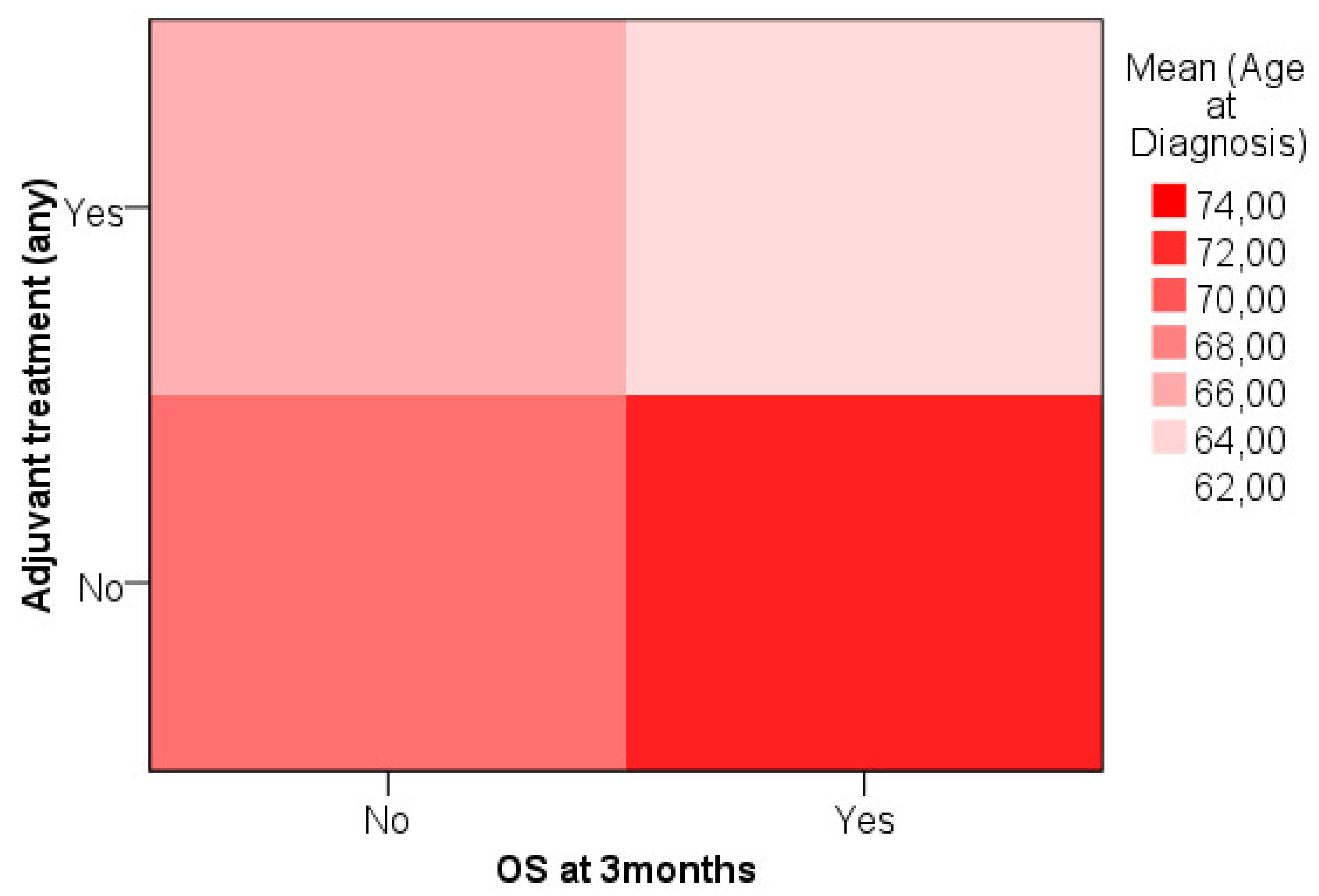

We analyzed age data attempting to define a cut-off for treatment decision considering OS at three months. Heat map showed that younger patients that survived longer than 3 months were more likely to have been treated with any adjuvant treatment while older patients that survived were less likely to receive adjuvant treatment [

Figure 2].

Based on the previous analysis a cut-off was established for age ≥ 72 (n=29, 29.3%). Within the 77 patients that survived after 3 months, 55 had age < 72 and 22 had had age ≥ 72. Within the 22 patients that did no survived after 3 months, 15 had age < 72 and 7 had age ≥ 72. Proportion of treated patients for survivors > 3 months with age ≥ 72 was 72.7% and for age < 72 was 92.7%. Proportion of treated patients for non-survivors > 3 months with age ≥ 72 was 14.3% and for age < 72 was 46.7%.

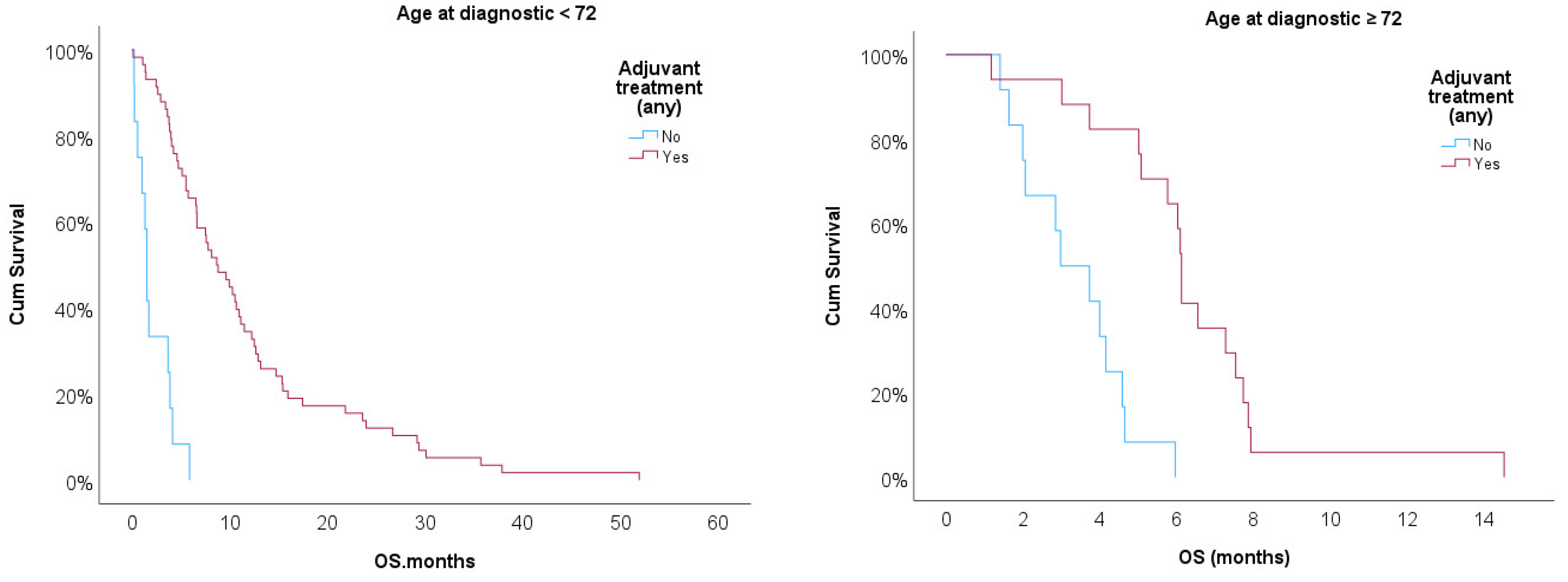

Kaplan-Meir curves were then implemented to compare OS for patients treated or non-treated with any adjuvant therapy adjusted for age ≥ 72 [

Figure 3]. Log-rank test showed statistical significance for treated vs. non-treated patients (p<0.001) after adjusting for age ≥ 72. Treated patients showed better prognostic in both strata, but age ≥ 72 had worse prognostic when compared with patients with KPS < 70 (p<0.05).

Age effect was studied as a covariate of treatment effect in OS ≥ 3 months. Univariate logistic regression showed an effect of OR=11.73 (p<0.001), 95%CI= [3.93 – 35.00] for treatment, suggesting that treatment is associated with increased likelihood or surviving after 3 months. After adjusting to age, treatment effect on survival after 3 months was maintained (OR=12.17, p<0.001, 95% CI= [3.84 – 38.54]).

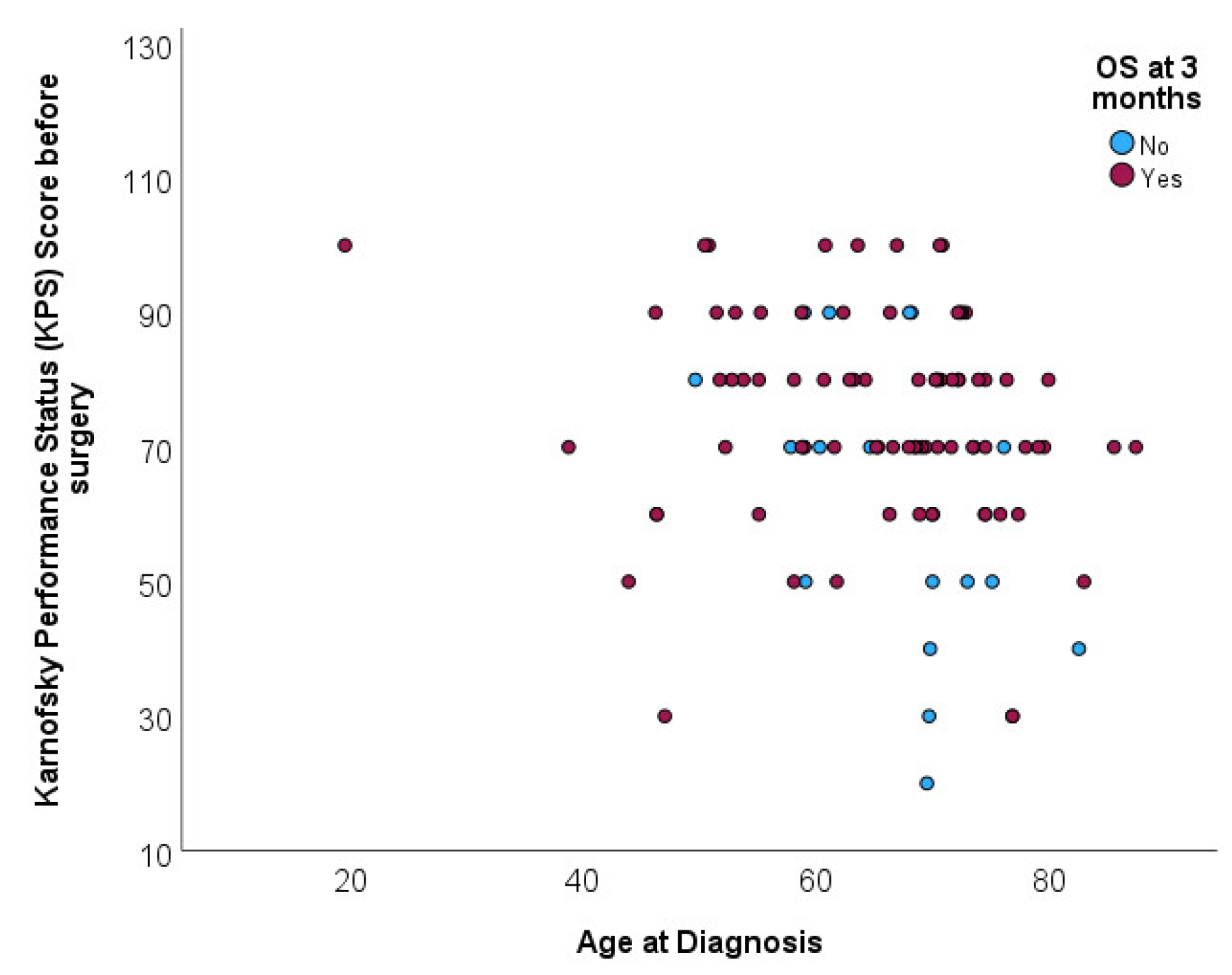

Distribution of age at diagnosis was not associated with overall survival at 3 months (p=0.296). Mean age for patients deceased before completing 3 months of follow up was 67.6 (SD=7.9) and mean age for patients deceased after completing 3 months of follow up was 64.8 (SD=11.6). Scatterplot shows the age distribution of patients according to survival beyond 3 moths, without any specific pattern [

Figure 4].

In conclusion, our data show that age per se does not determine the outcome of patients with IDH-wildtype glioblastoma undergoing biopsy.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to isolate a specific cohort of patients (IDH-Wildtype) defined as grade 4 according to the WHO 2021 criteria submitted to biopsy. These patients often escape the follow-up of a neurosurgeon and it is important to understand which patients actually undergo adjuvant treatment and benefit from it, in order to assess whether the decisions made in this difficult subgroup of patients are appropriate. On the other hand, some of these patients rarely exhibit unexpected survival rates and trying to identify them is also important An attempt was made to characterize this cohort to better understand their unique survival determinants. Studies specifically focusing on IDH-WT gliomas that have experienced only biopsy are scarce and are often incorporated into research involving multimodal treatments, including surgery. Additionally, such studies frequently include patients with IDH mutations, who typically exhibit a better prognosis and higher rates of MGMT promoter methylation.

The observations previously outlined, coupled with the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, partially explain the findings of our investigation regarding the diminished PFS of 3 months and OS of 6 months within our cohort. These outcomes invariably fall below the standards described in the recent literature for survival following glioma biopsies (OS ~ 8 months). [

12,

13,

21] Considering this, it is evident that patients initially subjected to biopsy and lack IDH Mutation exhibit a prognosis that is comparatively less favorable than their counterparts.

Even though patients undergoing biopsy generally exhibit a worse prognosis compared to the overall population, exists a very specific group of patients in our study - approximately 8% - who demonstrated a survival rate of more than 24 months. Interestingly, these patients also had a considerable high PFS of 17.12 months. These individuals were younger, had no comorbidities, were in good neurological condition, and received first-line adjuvant treatment. Although our molecular study was limited, we observed that only 25% of these patients exhibited MGMT promoter methylation. It has been noted that a very long survival can occur even in cases where only a biopsy was performed, without subsequent surgical resection. This finding is intriguing and somewhat paradoxical given the generally accepted belief that more aggressive surgical interventions typically correlate with better outcomes. According to the systematic review by Tomasz Tykocki and Mohamed Eltayeb, “Ten-year survival in glioblastoma. A systematic review,” approximately 5.56% of long-term survivors (9 out of 162 cases reviewed) underwent only a biopsy without subsequent surgical resection. In this study, a longer progression-free interval strongly correlates with better OS, and younger age at diagnosis has been consistently associated with increased chances of reaching ten-year survival. [

22]

Different studies show that patients who do not experience relapse often have tumors that lack methylation of the MGMT promoter. This is particularly interesting since the presence of MGMT promoter methylation has traditionally been associated with better responses to alkylating agent therapy and longer survival times. This observation suggests the presence of one or more currently unrecognized, but important molecular or other predictors of long-term survival. [

11] It’s important to highlight, that alterations in MYB, MN1, and the MAPK pathway typically correlate with improved survival outcomes. In contrast, the presence of mutations such as CDKN2A, TERT promoter mutations, EGFR amplifications, H3F3A alterations, and concurrent gain of chromosome 7 and loss of chromosome 10 tend to be associated with poorer survival. These factors may significantly influence prognosis and were not included in our analysis. [

14].

Another interesting point to reflect on was that 24.2% of patients (n=25) did not receive adjuvant treatment. Interestingly, this aligns with the literature, which reports a similar rate of 24.8%. [

23] If we consider this, it becomes evident that one-quarter of patients did not get any benefit from the treatment, suggesting that the risk-benefit ratio of the procedure should be better evaluated. For this reason, liquid biopsies, an evolving alternative to conventional brain tumor biopsy, offer a minimally invasive method for early detection, monitoring, and treatment modification. These biopsies include the analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or RNA (ctRNA) in various biofluids, including blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This method considerably decreases the risks and discomfort associated with surgical tissue sampling, while enabling healthcare professionals to track tumor evolution and response to treatment over time and can be an interesting area of focus in the future [

20]. Furthermore, not all patients are discussed with the oncology team to assess their capability to start adjuvant treatments, and a multidisciplinary decision pre-biopsy may be the answer to decrease this percentage. Another factor that may explain these findings is the decrease in KPS from the pre-biopsy period to the first oncology consultation one-month post-procedure, where patients begin treatment. The KPS dropped slightly, with a mean score of 72.2 preoperatively, declining to a mean of 65.7 postoperatively. The univariate and multivariate analyses suggest that a higher pre-surgery KPS is associated with a lower hazard ratio for both progression-free survival and overall survival, indicating better outcomes. Specifically, each point increase in KPS was associated with a 2% reduction in the risk of progression or death before adjuvant therapy. It should also be noted that only 33% of patients received the first-line STUPP protocol. Another 33% received hypofractionation, which is typically administered in our department to older patients with a lower capacity to tolerate increased doses of radiation.

The univariate and multivariate analyses suggest that higher pre-surgery KPS is associated with a lower hazard ratio for both PFS and OS, indicating better outcomes. This finding aligns with existing studies highlighting the importance of KPS. [

15,

22,

23] Our study further confirms the importance of this parameter as an independent predictor of survival. However, it should not be used as the single decisive factor. Although KPS is an important predictor of survival, patients with KPS < 70 who underwent biopsy and received adjuvant treatment showed better survival compared to those who did not receive any treatment. It is important to analyze the data carefully, as KPS refers to levels of functionality. For instance, a patient with good cognitive status, no comorbidities, and young age but who presents with paresis that prevents independence can still benefit from treatments. We also highlight the relationship between cognitive function and clinical outcomes. Cognitive impairment, particularly mild and severe levels, was associated with worse PFS, with hazard ratios indicating almost twice the risk of progression in patients with mild impairment and even higher in those with severe impairment. This association emphasizes the importance of neurocognitive assessments [

15]. Finally, the absence of contrast uptake on imaging manifests a significant association with OS in multivariate analysis (p=0.015). This parameter acquired considerable importance in therapeutic decision-making, nearly as much as KPS. Often, it does not appear as an important predictor in the literature and should be valued accordingly.

The management of glioblastomas among the elderly mirrors strategies applied to younger adults, emphasizing the safety and benefits of maximum resections. The rationale behind favoring biopsy over aggressive resection in older patients has historically been supported in the supposed poor prognosis, increased surgical risks, and unclear survival benefits. However, this perspective may overlook the significant advantages of maximum resections, challenging the premise that conservative approaches are invariably preferable in the elderly. Additional evidence suggests that the diminished prognosis for HGGs in older individuals might be more attributable to differences in tumor biology than age alone [

16]. The debate over the risks of surgical resection versus biopsy and Adjuvant therapy in older patients is supported by the appreciation that elderly individuals may have a reduced capacity to tolerate major surgeries and treatments due to comorbidities and diminished physiological reserves [

16,

17]. We attempted to establish a potential age-related cut-off for treatment decisions. The results indicated that while younger patients (age < 72) were more likely to receive adjuvant therapy, age did not significantly impact the effectiveness of the treatment in terms of survival at the three-month mark. In fact, treatment was a strong predictor of 3-month survival irrespective of age, with an odds ratio of 12.17 and no observed effect of age on survival, suggesting that the benefits of adjuvant therapy are not age-dependent. Moreover, the lack of a significant age effect on the efficacy of adjuvant therapy suggests that older patients should not be precluded from such treatment based solely on biologic age. [

18].

Our study did not focus on the importance of quality of life (QoL) assessments in patients with glioblastomas. QoL is an undervalued component of patient care, particularly in the context of glioblastoma, where survival rates are notably low, and all efforts are done to increase survival. We can’t disregard the increases in fatigue post-surgery and treatments, particularly pain during chemotherapy. A marked decrease in QoL is clear, specifically after radiotherapy and in the initial months of chemotherapy. Deciding which patients are likely to gain more from palliative care can be a valuable aspect of their management. [

19] Another important limitation is that many patients were referred to palliative care without undergoing biopsies and, as such, were not included in the study. Bevacizumab’s impact was noteworthy in univariate analysis (p=0.029) and it appeared as an independent factor upon multivariate analysis (p=0.002). Only patients in good general condition and those who had a good response to first-line treatment were referred for this off-label therapy, and therefore these results should be evaluated with caution. Although we meticulously documented all treatment approaches, the choice of treatment was not randomized and was influenced by patient status, tumor biology and multidisciplinary team discussions that can vary between different regions and protocols. Additionally, not all patients underwent MGMT promoter methylation testing, and many other molecular alterations were not assessed.

5. Conclusion

Our study exhibits an extensive investigation of the prognostic factors influencing survival outcomes in a cohort of patients diagnosed with IDH-wildtype glioma submitted to biopsy. This study highlights the importance of KPS both before and after surgery and any form of adjuvant treatment in determining patient outcomes. A decline in KPS post-operatively was indicative of poorer prognosis. We also clarified the adverse impact of cognitive impairment on PFS and OS for patients with mild cognitive deficits, and even higher for those severely impaired. Contrary to traditional fears regarding aggressive treatments in older patients, our data did not show a significant age-related impact on the three-month survival rate after adjuvant therapy in patients able to comply with treatment. While the volumetry, location, and hemisphere dominance of gliomas did not appear as significant predictors, lack of contrast uptake in imaging studies did and it was associated with a notably poorer PFS and OS, as an independent variable. Finally, a critical observation from our data is the clear survival benefit associated with adjuvant therapies post-biopsy, irrespective of their preoperative clinical status.

References

- Louis, D. N., Perry, A., Reifenberger, G., von Deimling, A., Figarella-Branger, D., Cavenee, W. K., Ohgaki, H., Wiestler, O. D., Kleihues, P., & Ellison, D. W. (2016). The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta neuropathologica, 131(6), 803–820. [CrossRef]

- Śledzińska, P., Bebyn, M. G., Furtak, J., Kowalewski, J., & Lewandowska, M. A. (2021). Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in Gliomas. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(19), 10373. [CrossRef]

- Louis, D. N., Perry, A., Wesseling, P., Brat, D. J., Cree, I. A., Figarella-Branger, D., Hawkins, C., Ng, H. K., Pfister, S. M., Reifenberger, G., Soffietti, R., von Deimling, A., & Ellison, D. W. (2021). The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro-oncology, 23(8), 1231–1251. [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Brat, D. J., Verhaak, R. G., Aldape, K. D., Yung, W. K., Salama, S. R., Cooper, L. A., Rheinbay, E., Miller, C. R., Vitucci, M., Morozova, O., Robertson, A. G., Noushmehr, H., Laird, P. W., Cherniack, A. D., Akbani, R., Huse, J. T., Ciriello, G., Poisson, L. M., Barnholtz-Sloan, J. S., … Zhang, J. (2015). Comprehensive, Integrative Genomic Analysis of Diffuse Lower-Grade Gliomas. The New England journal of medicine, 372(26), 2481–2498. [CrossRef]

- Domino, J. S., Ormond, D. R., Germano, I. M., Sami, M., Ryken, T. C., & Olson, J. J. (2020). Cytoreductive surgery in the management of newly diagnosed glioblastoma in adults: a systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline update. Journal of neuro-oncology, 150(2), 121–142. [CrossRef]

- Stummer, W. , Reulen, H. J., Meinel, T., Pichlmeier, U., Schumacher, W., Tonn, J. C., Rohde, V., Oppel, F., Turowski, B., Woiciechowsky, C., Franz, K., Pietsch, T., & ALA-Glioma Study Group (2008). Extent of resection and survival in glioblastoma multiforme: identification of and adjustment for bias. Neurosurgery, 62(3), 564–576. [CrossRef]

- Fogh, S. E., Boreta, L., Nakamura, J. L., Johnson, D. R., Chi, A. S., & Kurz, S. C. (2020). Neuro-Oncology Practice Clinical Debate: Early treatment or observation for patients with newly diagnosed oligodendroglioma and small-volume residual disease. Neuro-oncology practice, 8(1), 11–17. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. , Nath, S., Koziarz, A., Badhiwala, J. H., Ghayur, H., Sourour, M., Catana, D., Nassiri, F., Alotaibi, M. B., Kameda-Smith, M., Manoranjan, B., Aref, M. H., Mansouri, A., Singh, S., & Almenawer, S. A. (2018). Biopsy Versus Subtotal Versus Gross Total Resection in Patients with Low-Grade Glioma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World neurosurgery, 120, e762–e775. [CrossRef]

- Müller, D. M. J. , Robe, P. A. J. T., Eijgelaar, R. S., Witte, M. G., Visser, M., de Munck, J. C., Broekman, M. L. D., Seute, T., Hendrikse, J., Noske, D. P., Vandertop, W. P., Barkhof, F., Kouwenhoven, M. C. M., Mandonnet, E., Berger, M. S., & De Witt Hamer, P. C. (2019). Comparing Glioblastoma Surgery Decisions Between Teams Using Brain Maps of Tumor Locations, Biopsies, and Resections. JCO clinical cancer informatics, 3, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- González Bonet, L. G. , Piqueras-Sánchez, C., Roselló-Sastre, E., Broseta-Torres, R., & de Las Peñas, R. (2022). Long-term survival of glioblastoma: A systematic analysis of literature about a case. Neurocirugia (English Edition), 33(5), 227–236. [CrossRef]

- Hertler, C. , Felsberg, J., Gramatzki, D., Le Rhun, E., Clarke, J., Soffietti, R., Wick, W., Chinot, O., Ducray, F., Roth, P., McDonald, K., Hau, P., Hottinger, A. F., Reijneveld, J., Schnell, O., Marosi, C., Glantz, M., Darlix, A., Lombardi, G., Krex, D., … Weller, M. (2023). Long-term survival with IDH wildtype glioblastoma: first results from the ETERNITY Brain Tumor Funders’ Collaborative Consortium (EORTC 1419). European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990), 189, 112913. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C. , Hentschel, B., Simon, M., Westphal, M., Schackert, G., Tonn, J. C., Loeffler, M., Reifenberger, G., Pietsch, T., von Deimling, A., Weller, M., & German Glioma Network (2013). Long-term survival in primary glioblastoma with versus without isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 19(18), 5146–5157. [CrossRef]

- Karschnia, P. , Young, J. S., Dono, A., Häni, L., Sciortino, T., Bruno, F., Juenger, S. T., Teske, N., Morshed, R. A., Haddad, A. F., Zhang, Y., Stoecklein, S., Weller, M., Vogelbaum, M. A., Beck, J., Tandon, N., Hervey-Jumper, S., Molinaro, A. M., Rudà, R., Bello, L., … Tonn, J. C. (2023). Prognostic validation of a new classification system for extent of resection in glioblastoma: A report of the RANO resect group. Neuro-oncology, 25(5), 940–954. [CrossRef]

- Śledzińska, P., Bebyn, M. G., Furtak, J., Kowalewski, J., & Lewandowska, M. A. (2021). Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in Gliomas. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(19), 10373. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. T. , Park, C. K., Kim, J. W., Park, M. J., Lee, H., Lim, J. A., Choi, S. H., Kim, T. M., Lee, S. H., Park, S. H., Kim, I. H., & Lee, K. M. (2015). Early cognitive function tests predict early progression in glioblastoma. Neuro-oncology practice, 2(3), 137–143. [CrossRef]

- Almenawer, S. A., Badhiwala, J. H., Alhazzani, W., Greenspoon, J., Farrokhyar, F., Yarascavitch, B., Algird, A., Kachur, E., Cenic, A., Sharieff, W., Klurfan, P., Gunnarsson, T., Ajani, O., Reddy, K., Singh, S. K., & Murty, N. K. (2015). Biopsy versus partial versus gross total resection in older patients with high-grade glioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuro-oncology, 17(6), 868–881. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J. , & Walbert, T. (2017). Managing Glioblastoma in the Elderly Patient: New Opportunities. Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.), 31(6), 476–483.

- Wick, A. , Kessler, T., Elia, A. E. H., Winkler, F., Batchelor, T. T., Platten, M., & Wick, W. (2018). Glioblastoma in elderly patients: solid conclusions built on shifting sand?. Neuro-oncology, 20(2), 174–183. [CrossRef]

- Taskiran, E. , Kemerdere, R., Akgun, M. Y., Cetintas, S. C., Alizada, O., Kacira, T., & Tanriverdi, T. (2021). Health-related Quality of Life Assessment in Patients with Malignant Gliomas. Neurology India, 69(6), 1613–1618. [CrossRef]

- Brennan P., M. (2022). The future of brain tumor liquid biopsies in the clinic. Neuro-oncology advances, 4(Suppl 2), ii4–ii5. [CrossRef]

- Brown, N. F., Ottaviani, D., Tazare, J., Gregson, J., Kitchen, N., Brandner, S., Fersht, N., & Mulholland, P. (2022). Survival Outcomes and Prognostic Factors in Glioblastoma. Cancers, 14(13), 3161. [CrossRef]

- Tykocki, T. , & Eltayeb, M. (2018). Ten-year survival in glioblastoma. A systematic review. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia, 54, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Kole, A. J. , Park, H. S., Yeboa, D. N., Rutter, C. E., Corso, C. D., Aneja, S., Lester-Coll, N. H., Mancini, B. R., Knisely, J. P., & Yu, J. B. (2016). Concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for “biopsy-only” glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer, 122(15), 2364–2370. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).