1. Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM), the most aggressive primary brain tumor in adults, remains a significant therapeutic challenge. The standard of care typically involves maximal safe surgical resection followed by concurrent radiotherapy and temozolomide chemotherapy, based on the Stupp protocol [

1]. Despite these intensive first-line treatments, the prognosis remains poor, with a median overall survival of 12-15 months and inevitable disease progression in most patients. [

2]. Once recurrence occurs, therapeutic options become limited, and no treatment has consistently demonstrated a significant improvement in survival post-recurrence. The management of recurrent GBM (rGBM) remains highly debated, with no clear consensus on the optimal approach [

3].

Repeat resection is one approach that has been explored for managing rGBM, yet its efficacy remains contentious. Earlier studies often produced mixed results, partly due to heterogeneity in patient selection and molecular tumor characteristics, which were poorly understood before the 2021 WHO classification update. More recent evidence suggests that maximal safe re-resection may be associated with improved survival outcomes, particularly in patients with minimal residual tumor volume post-operatively [

4,

5]. Additionally, the influence of molecular profiles, such as IDH mutation status, Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation, is becoming increasingly recognized as critical factors influencing outcomes after reoperation [

6].

Deciding whether to pursue repeat resection is a complex process that requires careful consideration of various clinical, surgical, and molecular factors. This study aims to assess the overall survival benefits of repeat resection in a well-defined cohort of patients with rGBM, as well as to identify factors that can be associated with long-term survival. To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal matched case-control study that integrates clinical, radiological, and molecular parameters to evaluate the role of repeat resection in recurrent GBM. Furthermore, we aimed to identify factors for long-term survival following repeat resection, allowing for more informed patient selection and improved treatment planning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

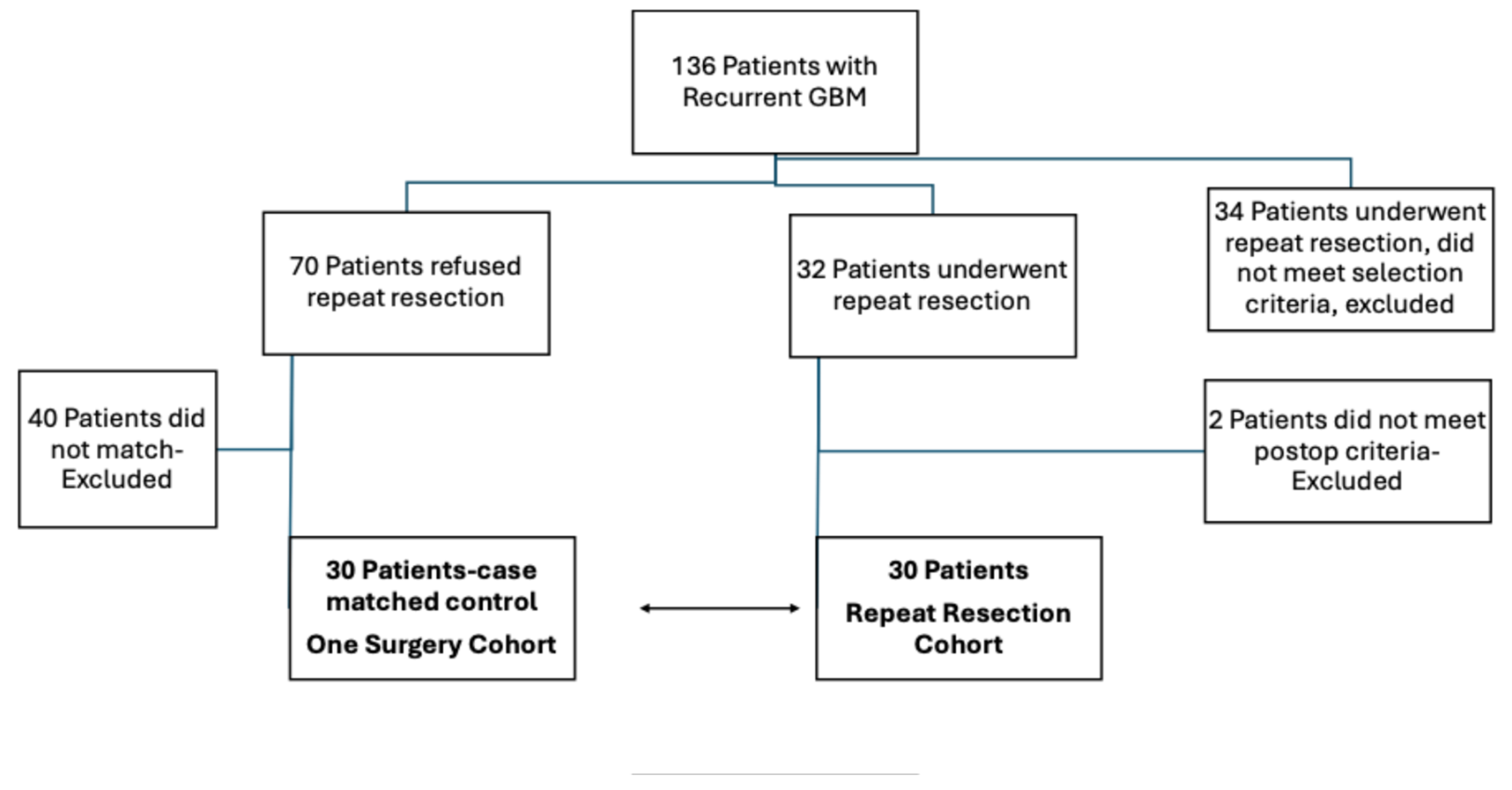

This study utilized a longitudinal, matched case-control design involving patients diagnosed with IDH-wildtype GBM and treated between 2014-2019 and pathological specimens were re-analysed and regraded based on WHO 2021 molecular criteria. The Institutional Review Board approved the study. The inclusion criteria for patients were radiological and/or symptomatic tumor progression, tumors suitable for surgical resection, failure of non-surgical therapies, requiring tissue sampling for further treatment planning, longitudinally followed until deceased and being medically fit for repeat procedure. Patients were required to meet all these criteria. Contraindications included inaccessible tumor locations, extensive disease spread, or severe comorbidities that had significant impact on the patient’s surgical procedure. The decision-making process involved a multidisciplinary team to thoroughly evaluate and balance the potential benefits and risks. Repeat surgical resection was offered to all eligible patients (n=136), with 102 patients with recurrent GBM meeting the inclusion criteria and enrolling in the study during the study period. Among these, 32 patients underwent repeat resection, while 70 declined the procedure. Additionally, 34 other patients underwent repeat resection during this timeframe but were excluded from the study due to not meeting at least one of the strict inclusion criteria. The reasons for refusing surgery include concerns about potential risks or complications, lack of belief in the surgical benefits, a preference to pursue second- or third-line medical treatments, family decisions, long travel distances for follow up, and an inability or unwillingness to adhere to the close follow-up requirements of the study. Thirty-two patients underwent surgery; however, 2 patients were excluded from the study for not meeting the required postoperative imaging and pathological criteria (unsatisfactory MRI findings, radiation necrosis, and the absence of viable tissue in pathology). The remaining 30 patients met the eligibility criteria with confirmed recurrent disease in the pathological examination of specimens and were matched to a control cohort based on criteria. Matching criteria included age, preoperative tumor volume at initial diagnosis, gender, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, preoperative ASA [the American Society of Anesthesiologists] score), extent of resection (EOR) at initial surgery, tumor location (left side and eloquent location based on motor-sensory-speech), GCS and KPS at presentation, postoperative adjuvant treatments and molecular markers (MGMT methylation, TERT mutation, p53, ATRX loss). Forty patients who were not matched were excluded from the study. Study groups were comprised of 2 cohorts: one surgical resection, who refused the repeat resection (n=30) and those who underwent repeat resection (n=30) (

Figure 1). All cases were operated by the senior author MM. Overall survival is measured from the date of the initial surgery to the time of death. Volumetric analyses of contrast-enhancing (CE) tumors were performed using a semi-automated method. In short, tumor volumes were quantified on pre- and postoperative MRI scans (obtained ≤48 hours after surgery). Using 3D Slicer (open-source software, version 5.6.2), total CE tumor was measured on contrast-enhanced T1 sequences, and non-contrast-enhancing (nCE) tumor was delineated on FLAIR or T2 sequences. Absolute volumes (cm³) were recorded for both first and repeat resections and relative volume reduction was calculated as (postoperative volume/preoperative volume) × 100. The Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) classification system for GBM divides the EOR into four primary categories based on residual tumor volume. Class 1 signifies supramaximal resection, which is defined as 0 cm³ of CE tumor and ≤5 cm³ of nCE tumor [

7,

8]. For patients with no postoperative residual CE tumor, MRIs were further analyzed in terms of the volume of the nCE tumor to determine their RANO scales. Eloquence was defined as the involvement of motor, sensory, and speech areas, and these factors were matched one-to-one, as was the left-side localization of tumors. Multicentric or multifocal GBMs that required multiple craniotomies at the initial presentation were excluded. Time to first progression was assessed per RANO 2.0 criteria [

9]. We further analyzed the repeat resection group in seeking to identify associated factors for long-term survival. We compared the patients (n=7) who had short survival with a median of 2.1 (±1.13) months to those who had a long survival with median of 12.77 (±8.4) (n=23) in the repeat resection group.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between the two groups were made using Student’s t-test, Mann Whitney U test, Pearson's χ² test, and Fisher’s Exact test as appropriate. Survival analyses were conducted using the Log-Rank test to compare overall survival between the groups.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

The mean age of patients undergoing one-surgery was 54.1±11.05 years (range: 24-71), compared to 49.3±10.74 years (range: 25-69) for those undergoing repeat resection (p=0.093). Preoperative tumor volumes were similar between the groups (46.1 cm³ vs. 45.5 cm³, p=0.871). Gender distribution was also comparable in one-surgery vs. repeat resection groups (15 females and 15 males vs. 21 females and 9 males, p=0.114, respectively). Comorbidities such as hypertension (11 vs. 7, p=0.260) and diabetes mellitus (4 vs. 8, p=0.219) showed no significant differences. There was no difference in their KPS and GCS at presentation. Ten patients in one-surgery and 11 patients in repeat resection group received second-line chemotherapy before the time they were offered repeat resection and they included bevacizumab, irinotecan, lomustine, or carboplatin. No significant differences in second-line medical therapies were observed between patients with one surgery and with repeat resection (

Table 1).

3.2. EOR and Molecular Markers

The EOR during the first surgery was similar between the groups, with 86.7% for the one resection group and 85.8% for the repeat resection group (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.917). The median residual tumor volume at the first surgery was 5.61 cm³ (range: 0-59.09) for the one resection group and 2.38 cm³ (range: 0-31.99) for the repeat resection group (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.347). RANO Class 1 resection during the first surgery was achieved in 7 patients in the one-surgery group and 10 patients in the repeat resection group (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.56). For the repeat resection group, the EOR during the second surgery was 88.2%, with a median residual tumor volume of 3 cm³ (range: 0-32). RANO Class 1 resection during the repeat surgery was achieved in 8 patients in the repeat resection group (

Table 2). Similarly, MGMT methylation and TERT mutation status were not significantly different between these groups (p>0.05) (

Table 1). Other molecular markers like CDKN2A/B, KDR, EGFR were not available for all patients at the time of study.

3.3. Overall Survival

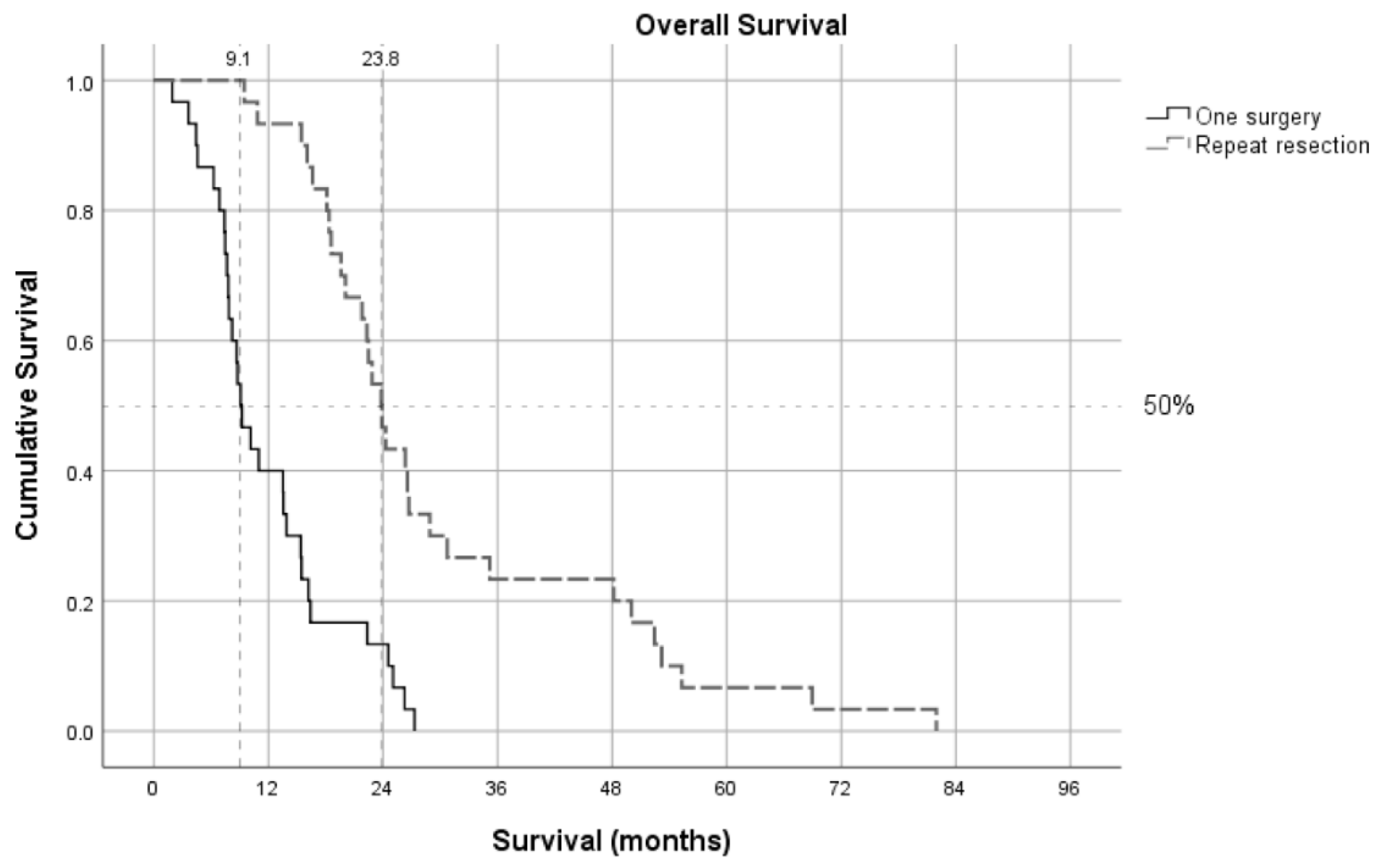

Patients who underwent one resection had a median survival of 9.2 months, whereas those who underwent repeat resection had a significantly longer median survival of 23.4 months (Log Rank test, p < 0.001) (

Figure 2). The median time to second resection in the repeat resection group was 11.6 months, with a subsequent median survival of 11.3 months after the second resection. Although excluded 40 patients who underwent one-surgery are not within the scope of this manuscript due to the one-to-one case-control matching design with the strict matching criteria; however, it is worth mentioning that among the excluded patients who underwent only one surgery, the median age was 68 years, with 23 males and 17 females. The median overall survival in this group was 10.1 months.

3.4. Factors Related to Long Survival After Repeat Resection

In the repeat surgery cohort, 7 out of 23 patients did not survive long enough to receive postoperative adjuvant therapy. In this short-survival group, the median survival was 2.1 months (range: 2–3.5) compared to 12.77 months (range: 6.1–50.6) in patients who were able to receive adjuvant therapy and achieved longer survival. We compared the patients who had short survival (n=7) to those who had long survival (n=23) after the repeat resection group to identify associated factors for long-term survival (

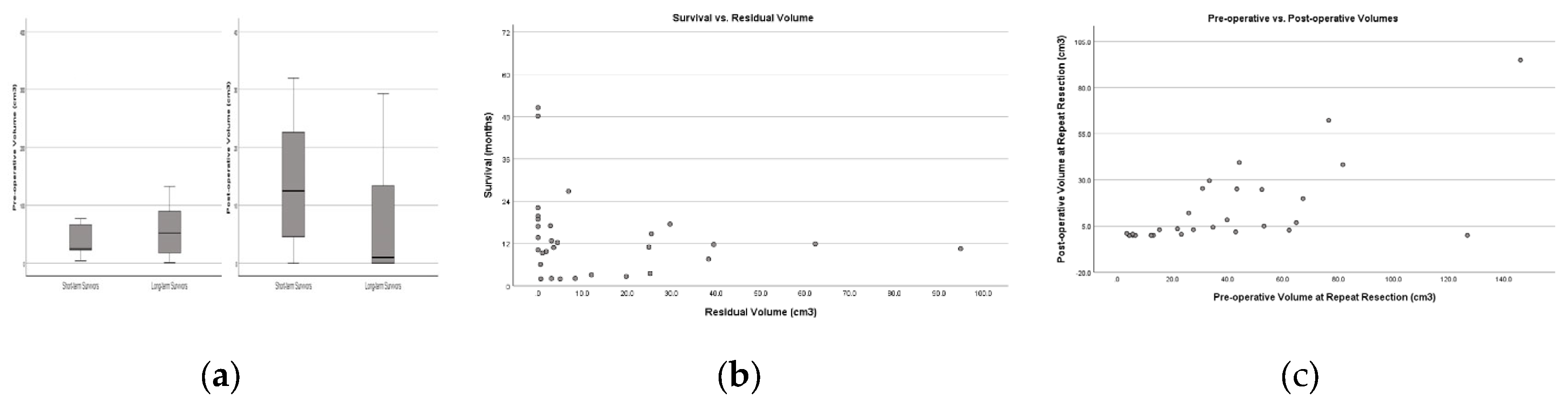

Table 3). All patient after the repeat resection had better GCS and their KPS remained stable without additional neurological deficits. Among several factors, only the preoperative GCS and preoperative KPS were significantly different between short-term and long-term survivors following repeat resection. The Park score, which combines preoperative tumor volume, KPS, and tumor location within the motor, speech, or middle cerebral artery territory, was influential but did not achieve statistical significance, likely due to the limited sample size (Fisher’s Exact, p=0.07). Neither the postoperative residual volume nor the EOR achieved statistical significance after the repeat resection. RANO Class 1 resection was attained in 8 out of 23 long-term survivors, but 0 out of 7 short-term survivors. However, the difference was not significant, probably due to sample size (Fisher’s Exact, p=0.307). The residual volume after repeat resection was notably smaller among long-term survivors (long-term survivors=2.79 cm3 vs. short-term survivors=8.35 cm3) (

Figure 3-A). The Pearson regression analysis showed a weak relationship, which suggests a more noticeable trend that higher residual volumes are linked to shorter survival (R square=0.03 p=0.36) (

Figure 3-B). To determine if there was a strong cutoff point in the data, we further analyzed whether a specific threshold of residual volume could significantly separate survival outcomes. The most significant difference occurs at the 0.0 cm³ threshold. Patients with no residual volume have a mean survival of 25.0 months, while those with any residual volume have a mean survival of 9.4 months in the repeat resection group. This suggests that complete resection with 0.0 cm³ residual volume might be associated with notably better survival outcomes. (

Figure 3-B).

Then, we analyzed the relationship between preoperative and postoperative volumes in repeat resection using a linear regression model, we found that higher preoperative volumes before the repeat resection were associated with higher postoperative volumes. The preoperative volumes may moderately be associated with postoperative residuals after repeat resection with a positive linear relationship, as demonstrated by the statistically significant results (R-square: 0.43, p=0.0001) (

Figure 3-C).

4. Discussion

Our study demonstrates a significant survival benefit for patients undergoing repeat resection in recurrent GBM, with a median survival of 23.4 months, substantially longer than the 9.17 months observed in patients with only one-surgery. These findings support the earlier consideration of repeat resection, particularly before consciousness (GCS) and functional deterioration (KPS) occur. Furthermore, smaller preoperative tumor volumes were associated with less residual tumor after surgery. Notably, patients with no residual tumor volume after repeat resection had a mean survival of 25.0 months, compared to 9.4 months for those with residual tumors, suggesting that RANO Class 1 resection may lead to better survival outcomes.

GBM is an extremely aggressive brain tumor that inevitably recurs, even after intensive first-line treatment [

2,

10]. Currently, therapeutic strategies for recurrent glioblastoma are inadequate, as no treatment has demonstrated significant improvement in post-recurrence survival in randomized controlled trials [

3,

11]. While earlier studies have reported mixed outcomes with surgical resection at tumor progression, recent evidence suggests that repeat resection may be associated with improved survival outcomes [

4] [

12,

13,

14]. Moreover, patients selected for repeat resection often have a more favorable clinical profile and less extensive, non-eloquent disease, raising questions about whether the observed benefits are due to selection bias or the EOR itself [

15,

16]. There is a notable literature gap regarding the selection process for patients with GBM, which presents inherent challenges for conducting prospective controlled trials. These challenges arise from various factors, including ethical considerations, tumor location, patient comorbidities, surgeons' approaches, and molecular subgroups of GBM. To address these issues, we designed a study with matched case-control design to exclude confounding factors.

While some studies have not shown favorable outcomes with surgical resection at tumor progression, recent evidence suggests that repeat resection may be associated with improved outcomes. [

12,

13,

14,

17]. Our study demonstrated the benefits of repeat resection in rGBM through a matched case-control, longitudinal approach. Repeat surgery provides patients with “a fresh start”, effectively resetting the clock to the initial time point, offering survival outcomes comparable to those seen after the first resection (11.63 vs. 11.35 mo.s, time to 2nd surgery vs. survival after 2nd surgery, respectively).

Recent studies have emphasized the importance of minimizing residual tumor volume during reoperation to maximize patient survival, suggesting that the surgical goal should be maximal safe resection for eligible patients [

6,

7,

18,

19] . Patients selected for repeat resection often have a more favorable clinical profile and less extensive, non-eloquent disease, which raises the question of whether the observed benefits are truly due to the EOR or simply a result of selection bias [

16]. The EOR has consistently been identified as a key prognostic factor, with studies highlighting that minimizing residual tumor volume during both initial and repeat surgeries is crucial for improving survival. Comparing previous surgical studies is complicated by inconsistent terminology used to describe the EOR, often referring to relative tumor reduction in percentage terms. The study by Yong et al. analyzed the impact of residual tumor volume on the survival of patients with rGBM who underwent reoperation. The median postoperative survival was 12.4 months, and results indicated that larger residual tumors (>3 cm³) were associated with significantly decreased survival compared to smaller or no residual tumors. The findings emphasize the importance of minimizing residual tumor volume during reoperation to maximize patient survival. [

18]. Given that absolute residual tumor volume (in cm³) might be more prognostically significant than relative resection extent, the “RANO classification for EOR” was recently established based on residual CE and nCE tumors to standardize terminology (Molinaro et al., 2020). This classification aims to provide a more consistent and prognostically relevant measure of surgical success, thereby improving the design of future clinical trials and patient management strategies [

8,

20]. A recent study by the RANO resect group investigated the impact of repeat resection on the outcomes of patients with recurrent IDH wild-type GBM. Data from 681 glioblastoma patients with first tumor recurrence were collected, showing that all tumors were IDH wild-type GBM WHO grade 4. Re-resection was performed in 310 patients (45.5%), while 371 patients (54.5%) were managed non-surgically. The study found no distinct molecular profile for tumors selected for repeat resection, but these tumors often had a superficial location. Patients who underwent repeat resection typically had "supramaximal" or "maximal" resection of CE tumor initially and were generally younger with higher KPS at recurrence. Re-resection was associated with favorable outcomes, with a median overall survival of 11 months after recurrence compared to 7 months for non-surgically managed patients. This survival benefit persisted after adjusting for clinical confounders. The study found that only patients with residual CE tumor volumes ≤1 cm³ had improved outcomes, and the RANO classification system effectively stratified patients [

7]. Preoperative tumor volume has been identified as a significant factor for survival in rGBM previously [

12]. In our study, we demonstrated for the first time that larger preoperative volumes tend to be associated with larger postoperative residual volumes, for every 1 ml increase in preoperative volume, the postoperative volume increased by approximately 0.43 ml after repeat resections. This finding underscores the impact of initial tumor size on surgical outcomes in rGBM and supports the need for early surgical intervention in managing the disease.

Repeat surgery related series in favor of repeat resections [

4,

12,

13,

14] were mainly based on molecularly ill-defined cohorts prior to the 2021 WHO classification [

21]. A recent study by Dono et al. analyzed data from 273 patients treated for rGBM, finding that genetic factors like CDKN2A/B loss and KDR mutations were linked to shorter post-progression survival. Repeat surgery, especially when combined with bevacizumab, improved post-progression survival, particularly in younger patients with better performance status, extending survival by 7.0 months in IDH wild-type rGBMs. Patients with specific genetic profiles, such as EGFR mutations and CDKN2A/B mutations, benefited most from repeat resection. The study suggests that while maximal safe re-resection improves survival overall, certain genetic profiles gain greater benefit [

6]. In our series, we did not identify any specific genetic feature linked to improved survival.

Level of consciousness and functional status at the time of repeat resection are critically important factors in determining outcomes. Several studies emphasize the critical role of KPS in the prognosis of patients with IDH-wildtype GBM. Chen et al. demonstrated that higher KPS, along with supramaximal resections, significantly improves survival [

22]. Similarly, Park et al. showed that repeat resection for rGBM led to better survival outcomes, with a higher post-treatment KPS strongly associated with improved functional status and longer survival [

23]. Our findings are consistent with previous studies, showing that a KPS ≤70 is significantly associated with short-term survival. Our study is the first to incorporate the GCS into prognostication for repeat surgery in rGBM, revealing that patients with a GCS score of equal or less than 13 are directly linked to shorter survival [

24]. We acknowledge that selection bias remains the primary limitation of our single-center case-control design. To mitigate this, we implemented a rigorous approach, incorporating strict case matching based on a comprehensive set of demographic, clinical, molecular, and radiologic criteria. Furthermore, the study is strengthened by detailed longitudinal follow-up data, although residual bias may still limit the generalizability of the findings. Repeat resection cohort comprises young and fit patients who may not be representative of the typical GBM population. To further validate our results, future research should consider prospective study designs or recruit larger and more diverse patient populations. A clinical trial with an expanded cohort would be instrumental to reaffirm the borderline significance observed in key parameters, including the Park score, RANO criteria, and the relationship between preoperative and postoperative tumor volume. Such a trial would have enhanced impact if conducted through multi-institutional collaborations.

5. Conclusions

Complete repeat resection appears to improve overall survival in patients with recurrent GBM, IDH-wildtype, and may have therapeutic value beyond its traditional role as a diagnostic or salvage procedure. Early surgical intervention aimed at achieving complete resection should be considered to potentially optimize outcomes before patients develop low KPS, low GCS, or tumor volumes that exceed safe surgical thresholds. However, while our study found a notable survival difference at the 0.0 cm³ threshold for contrast-enhancing (CE) residual tumor, RANO Class 1 resection did not reach statistical significance. This underscores the need for caution in interpreting these results. Further research with larger, multi-institutional cohorts is necessary to confirm these findings for patients with recurrent GBM.

Author Contributions

MM is the senior author, lead neurosurgeon, and conceptual designer of the study. MM performed all surgeries, oversaw patient follow-up, and conducted data analysis and wrote the manuscript; HYZ and CSA were responsible for analysis of data, statistical analyses and preparation of figures; DS contributed significantly to writing, editing the manuscript, and providing expert consultation; FS conducted the pathological examinations, ensuring accuracy in diagnostic findings; and AA performed radiological evaluations and volumetric assessments, contributing critical data for analysis.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board of Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine approved

the study (Ethics number: 14/292-25, 20/12-60). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine (Ethics number: 14/292-25, 20/12-60).

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to retrospective nature of study in exempt status.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EOR |

Extent of resection |

| GBM |

Glioblastoma |

| rGBM |

Recurrent GBM |

| MGMT |

Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase |

| ASA |

The American Society of Anesthesiologists score |

| CE |

Contrast-enhancing |

| n-CE |

non-contrast-enhancing |

References

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [CrossRef]

- Wen PY, W.M., Lee EQ, . and et al. "Glioblastoma in adults: A society for neuro-oncology (sno) and european society of neuro-oncology (eano) consensus review on current management and future directions." Neuro Oncol (2020): 1073-113.

- Tsien CI, P.S., Dicker AP, . and et al. "Nrg oncology/rtog1205: A randomized phase ii trial of concurrent bevacizumab and reirradiation versus bevacizumab alone as treatment for recurrent glioblastoma." Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (2022): 36260832.

- Ringel F, P.H., Sabel M, . and et al. "Clinical benefit from resection of recurrent glioblastomas: Results of a multicenter study including 503 patients with recurrent glioblastomas undergoing surgical resection." Neuro Oncol (2016): 96-104.

- Karschnia, P.; Karschnia, P.; Young, J.S.; Young, J.S.; Dono, A.; Dono, A.; Häni, L.; Häni, L.; Sciortino, T.; Sciortino, T.; et al. Prognostic validation of a new classification system for extent of resection in glioblastoma: A report of the RANO resect group. Neuro-Oncology 2022, 25, 940–954. [CrossRef]

- Dono A, Z.P., Holmes E, . and et al. "Impacts of genotypic variants on survival following reoperation for recurrent glioblastoma." J Neurooncol (2022): 353-63.

- Karschnia, P.; Dono, A.; Young, J.S.; Juenger, S.T.; Teske, N.; Häni, L.; Sciortino, T.; Mau, C.Y.; Bruno, F.; Nunez, L.; et al. Prognostic evaluation of re-resection for recurrent glioblastoma using the novel RANO classification for extent of resection: A report of the RANO resect group. Neuro-Oncology 2023, 25, 1672–1685. [CrossRef]

- Karschnia P, Y.J., Dono A, . and et al. "Prognostic validation of a new classification system for extent of resection in glioblastoma: A report of the rano resect group." Neuro Oncol (2022): 35961053.

- Wen, P.Y.; Bent, M.v.D.; Youssef, G.; Cloughesy, T.F.; Ellingson, B.M.; Weller, M.; Galanis, E.; Barboriak, D.P.; de Groot, J.; Gilbert, M.R.; et al. RANO 2.0: Update to the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Criteria for High- and Low-Grade Gliomas in Adults. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 5187–5199. [CrossRef]

- Gorlia T, S.R., Brandes AA, . and et al. "New prognostic factors and calculators for outcome prediction in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: A pooled analysis of eortc brain tumour group phase i and ii clinical trials." European journal of cancer (2012): 1176-84.

- Wick W, G.T., Bendszus M, . and et al. "Lomustine and bevacizumab in progressive glioblastoma." The New England journal of medicine (2017): 1954-63.

- Park JK, H.T., Arko L, . and et al. "Scale to predict survival after surgery for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme." Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (2010): 3838-43.

- Suchorska, B.; Weller, M.; Tabatabai, G.; Senft, C.; Hau, P.; Sabel, M.C.; Herrlinger, U.; Ketter, R.; Schlegel, U.; Marosi, C.; et al. Complete resection of contrast-enhancing tumor volume is associated with improved survival in recurrent glioblastoma—results from the DIRECTOR trial. Neuro-Oncology 2016, 18, 549–556. [CrossRef]

- Behling F, R.J., Dangel E, . and et al. "Complete and incomplete resection for progressive glioblastoma prolongs post-progression survival." Front Oncol (2022): 755430.

- González, V.; Brell, M.; Fuster, J.; Moratinos, L.; Alegre, D.; López, S.; Ibáñez, J. Analyzing the role of reoperation in recurrent glioblastoma: a 15-year retrospective study in a single institution. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 20, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Tully, P.A.; Gogos, A.J.; Love, C.; Liew, D.; Drummond, K.J.; Morokoff, A.P. Reoperation for Recurrent Glioblastoma and Its Association With Survival Benefit. Neurosurgery 2016, 79, 678–689. [CrossRef]

- Ringel, F.; Pape, H.; Sabel, M.; Krex, D.; Bock, H.C.; Misch, M.; Weyerbrock, A.; Westermaier, T.; Senft, C.; Schucht, P.; et al. Clinical benefit from resection of recurrent glioblastomas: results of a multicenter study including 503 patients with recurrent glioblastomas undergoing surgical resection. Neuro-Oncology 2015, 18, 96–104. [CrossRef]

- Yong, R.L.; Wu, T.; Mihatov, N.; Shen, M.J.; Brown, M.A.; Zaghloul, K.A.; Park, G.E.; Park, J.K. Residual tumor volume and patient survival following reoperation for recurrent glioblastoma. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 121, 802–809. [CrossRef]

- Molinaro AM, H.-J. S., Morshed RA, . and et al. "Association of maximal extent of resection of contrast-enhanced and non-contrast-enhanced tumor with survival within molecular subgroups of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma." JAMA Oncol (2020): 495-503.

- Bjorland, L.S.; Mahesparan, R.; Fluge, Ø.; Gilje, B.; Kurz, K.D.; Farbu, E. Impact of extent of resection on outcome from glioblastoma using the RANO resect group classification system: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. Neuro-Oncology Adv. 2023, 5, vdad126. [CrossRef]

- Louis DN, P.A., Wesseling P, . and et al. "The 2021 who classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary." Neuro Oncol (2021): 34185076.

- Chen, M.W.; Morsy, A.A.; Liang, S.; Ng, W.H. Re-do Craniotomy for Recurrent Grade IV Glioblastomas: Impact and Outcomes from the National Neuroscience Institute Singapore. World Neurosurg. 2015, 87, 439–445. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.W.; Choi, K.S.; Foltyn-Dumitru, M.; Brugnara, G.; Banan, R.; Kim, S.; Han, K.; Park, J.E.; Kessler, T.; Bendszus, M.; et al. Incorporating Supramaximal Resection into Survival Stratification of IDH-wildtype Glioblastoma: A Refined Multi-institutional Recursive Partitioning Analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 4866–4875. [CrossRef]

- Askun, M.M.; Zengin, Y.; Azizova, A.; Karli-Oguz, K.; Saydam, O.; Strobel, T.; Soylemezoglu, F. Repeat Resection for Recurrent Glioblastoma in the WHO 2021 Era: A Prospective Matched Case-Control Study. Neurosurgery 2024, 70, 200–200. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).