Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Questionnaire Design

2.4. Data Collection and Processing

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

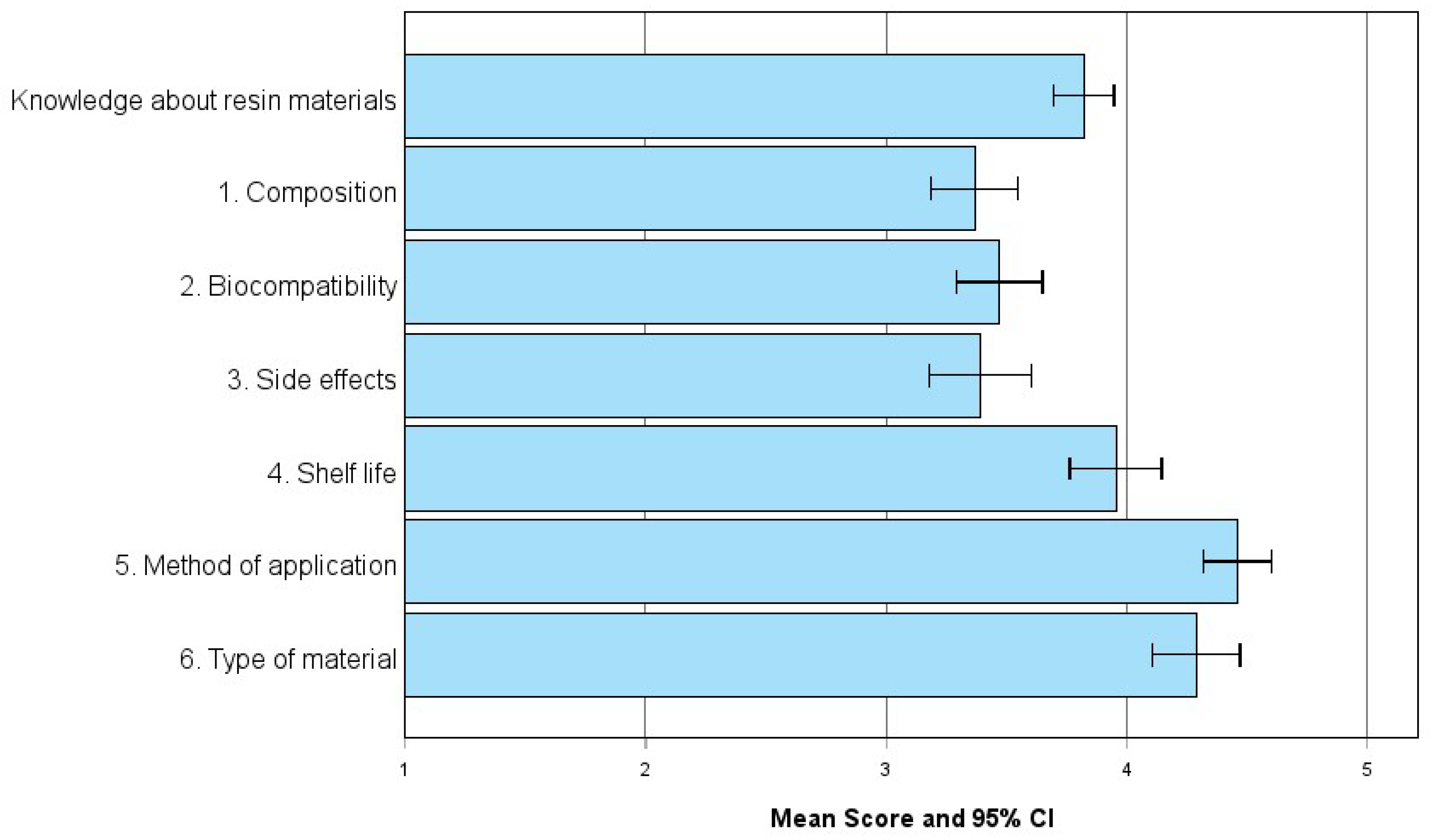

3.2. Knowledge About Resin Materials

3.2.1. Knowledge Levels in Resin Materials and Correlation with Professional Characteristics

3.2.2. Dentists’ Familiarity and Priorities in Resin Material Selection: Specifications, Features, and Sustainability

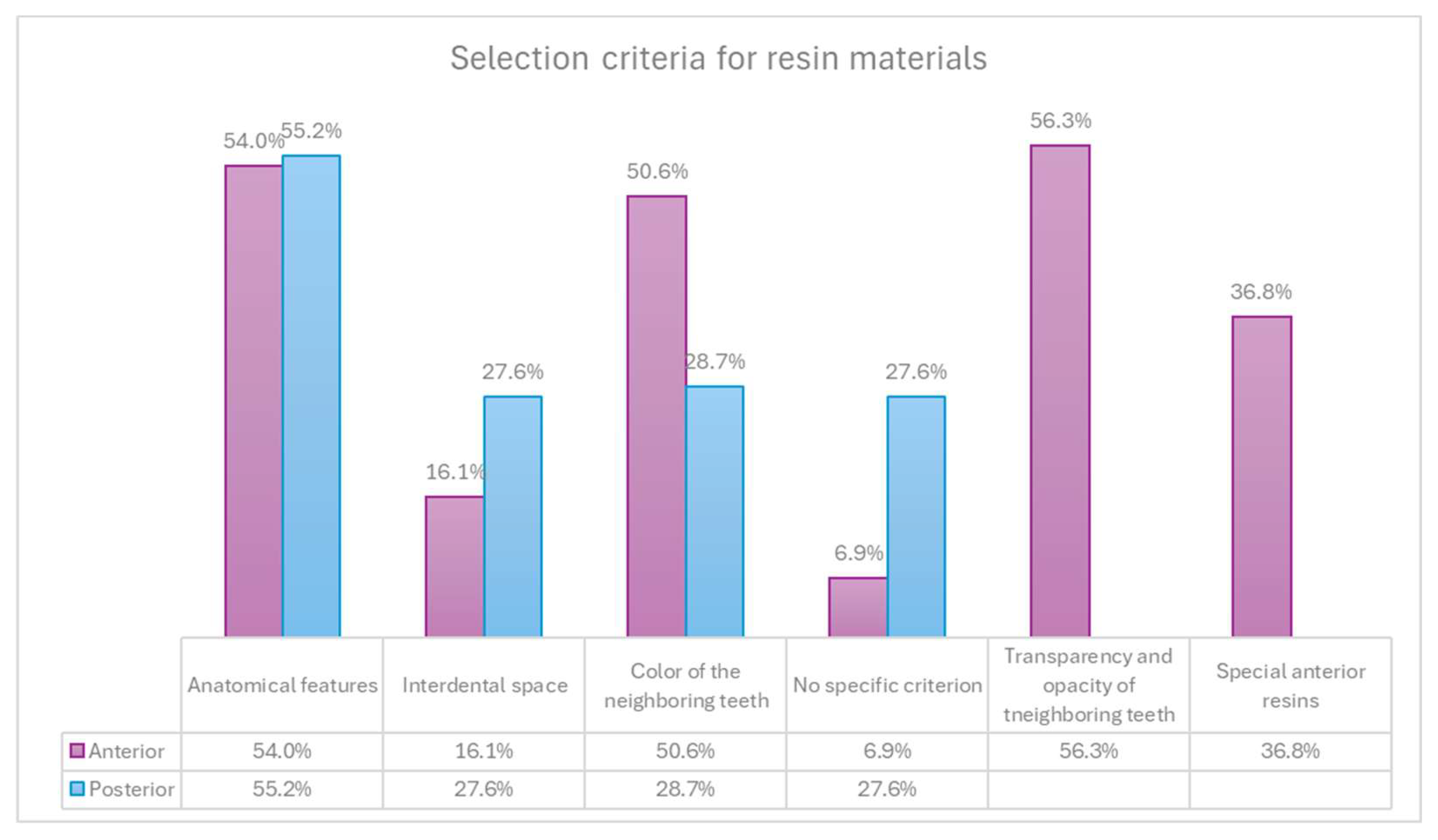

3.3. Selection of Resin Materials

3.3.1. Resin Selection in Anterior and Posterior Restorations

3.4. Professional Characteristics and Resin Material Selection

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Professional Characteristics on Material Selection

4.2. Regional Differences in Resin Material Criteria

4.3. Procurement Responsibility and Specification Awareness

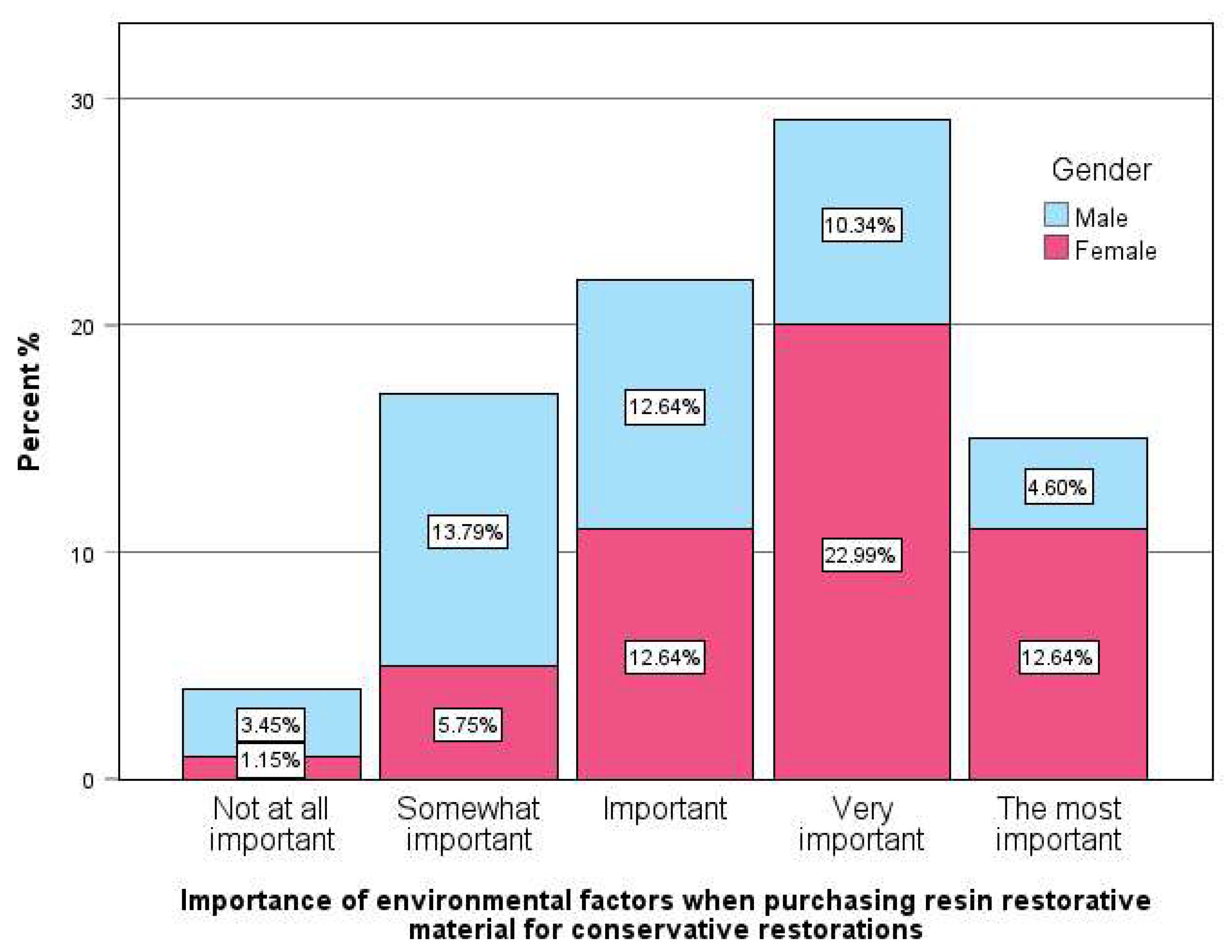

4.4. Sustainability and Gender-Based Preferences

4.5. Implications for Clinical Education and Future Research

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusion

References

- Yadav, R.; Lee, H.H. Ranking and selection of dental restorative composite materials using FAHP-FTOPSIS technique: An application of multi criteria decision making technique. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2022, 132, 105298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demarco, F.F.; Cenci, M.S.; Montagner, A.F.; et al. Longevity of composite restorations is definitely not only about materials. Dental materials: official publication of the Academy of Dental Materials 2023, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, K.; Martins, R.; Hadis, M.A.; et al. ‘Own-Label’ Versus Branded Commercial Dental Resin Composite Materials: Mechanical And Physical Property Comparisons. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent 2016, 24, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratap, B.; Gupta, R.K.; Bhardwaj, B.; et al. Resin based restorative dental materials: characteristics and future perspectives. Jpn Dent Sci Rev 2019, 55, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintze, S.D.; Ilie, N.; Hickel, R.; et al. Laboratory mechanical parameters of composite resins and their relation to fractures and wear in clinical trials—A systematic review. Dental materials 2017, 33, e101–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ren, L.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Evaluation of the Color Stability, Water Sorption, and Solubility of Current Resin Composites. Materials 2022, 15, 6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminoroaya A, Neisiany RE, Khorasani SN, et al. A review of dental composites: Challenges, chemistry aspects, filler influences, and future insights. Composites Part B: Engineering 2021, 216, 108852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz G, Watts DC and Darvell BW. Dental materials science: Research, testing and standards. Dental materials: official publication of the Academy of Dental Materials 2021, 37, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz G, Schwendicke F, Hickel R, et al. Alternative Direct Restorative Materials for Dental Amalgam: A Concise Review Based on an FDI Policy Statement. International dental journal 2023, 74. [CrossRef]

- Soni N, Bairwa S, Sumita S, et al. Mechanical Properties of Dental Resin Composites: A Review. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews 2024, 5, 7675–7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (ISO) IOfS. Scopes -ISO/TC 106 Dentistry Subcommittees 1 and 2.

- ADA Division of Science ACoSA. Resin-based composites. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939) 2003, 134, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organization for Standardization G, Switzerland. ISO 4049:2019. DentistryPolymer-based restorative materials. 2019, 29.

- Cho K, Rajan G, Farrar P, et al. Dental resin composites: A review on materials to product realizations. Composites Part B: Engineering 2021, 230, 109495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracane JL, Hilton TJ, Stansbury JW, et al. Academy of Dental Materials guidance-Resin composites: Part II-Technique sensitivity (handling, polymerization, dimensional changes). Dental materials: official publication of the Academy of Dental Materials 2017, 33, 1171–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie N, Hilton TJ, Heintze SD, et al. Academy of Dental Materials guidance -Resin composites: Part I-Mechanical properties. Dental materials: official publication of the Academy of Dental Materials 2017, 33, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap AU, Eweis AH and Yahya NA. Dynamic and Static Flexural Appraisal of Resin-based Composites: Comparison of the ISO and Mini-flexural Tests. Operative dentistry 2018, 43, E223–e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouf mohamed saeed shaabin RHK, Hibah Saad Al-Ahmadi, Rasha Nabeel Halal, Afaf Ahmed Tawati, Maram mohamed saeed shaabin, Nadia Abdulrahman addas, Maha sameer linjawi, Waleed saleh balubaid, Mohamed fouad Garanbish,; Abeer Abdullatif Alomarey. Materia l Selection for Posterior Restorations: An Observational Study Evaluating Dentists’ Preferences in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology 2022, 30, 649–659. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoneim A, Yu B, Lawrence H, et al. What influences the clinical decision-making of dentists? A cross-sectional study. PloS one 2020, 15, e0233652–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandi, NZ. Current trends in placing posterior composite restorations: Perspectives from Palestinian general dentists: A questionnair study. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry 2024, 14, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento GG, Correa MB, Opdam N, et al. Do clinical experience time and postgraduate training influence the choice of materials for posterior restorations? Results of a survey with Brazilian general dentists. Brazilian dental journal 2013, 24, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleefa S, Yeslam H and Hasanain F. Knowledge and Attitude of Recent Dental Graduates towards Smart/Bioactive Dental Composites. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International 2021, 33, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WD AL, Ingle N, Assery M, et al. Dentists’ Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Evidence-Based Dentistry Practice in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences 2019, 11, S507–s514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi O, Alam M, Alshareef R, et al. Environmental factors affecting green purchase behaviors of the consumers: Mediating role of environmental attitude. Cleaner Environmental Systems 2023, 100130. [CrossRef]

- Ririn Y, Rahmat STY and Rina A. How packaging, product quality and promotion affect the purchase intention? Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences 2019, 92, 46–55.

- Rundh, B. Linking packaging to marketing: how packaging is influencing the marketing strategy. British Food Journal 2013, 115, 1547–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane B, Ramasubbu D, Harford S, et al. Environmental sustainability and procurement: purchasing products for the dental setting. British dental journal 2019, 226, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshkbid E, Cree DE, Bradford L, et al. Biodegradable Alternatives to Plastic in Medical Equipment: Current State, Challenges, and the Future. 2024, 8, 342.

- Mulimani, P. Green dentistry: the art and science of sustainable practice. British dental journal 2017, 222, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier C, Thatcher J, Grover V, et al. Cross-sectional research: A critical perspective, use cases, and recommendations for IS research. International Journal of Information Management 2023, 70, 102625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed A, Pereira L and Jane K. Mixed Methods Research: Combining both qualitative and quantitative approaches. 2024.

- Chai HH, Gao SS, Chen KJ, et al. A Concise Review on Qualitative Research in Dentistry. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18 2021/01/28. [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan P and Caduff, C. Designing and validating a research questionnaire - Part 1. Perspectives in clinical research 2023, 14, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal B and Chhetri, D. A Pilot Study Approach to Assessing the Reliability and Validity of Relevancy and Efficacy Survey Scale. Janabhawana Research Journal 2024, 3, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster J and Roberts, HW. 12-Month flexural mechanical properties of conventional and self-adhesive flowable resin composite materials. Dental materials journal 2023, 42, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese L, Fabiano F, Bonaccorsi LM, et al. Evaluation of the Clinical Impact of ISO 4049 in Comparison with Miniflexural Test on Mechanical Performances of Resin Based Composite. International journal of biomaterials 2015, 2015, 149798–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson RL and Barkmeier, WW. Comparisons of ISO depth of cure for a resin composite in stainless-steel and natural-tooth molds. European journal of oral sciences 2019, 127, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan PL, Schumacher RM, Azzolin K, et al. Curing-light intensity and depth of cure of resin-based composites tested according to international standards. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939) 2002, 133, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flury S, Hayoz S, Peutzfeldt A, et al. Depth of cure of resin composites: is the ISO 4049 method suitable for bulk fill materials? Dental materials: official publication of the Academy of Dental Materials 2012, 28, 521–528. [CrossRef]

- Heintze S and Zimmerli, B. Relevance of in-vitro tests of adhesive and composite dental materials. A review in 3 parts. Part 2: non-standardized tests of composite materials. Schweizer Monatsschrift für Zahnmedizin = Revue mensuelle suisse d’odonto-stomatologie = Rivista mensile svizzera di odontologia e stomatologia/SSO 2011, 121, 916–930. [Google Scholar]

- Heintze SD and Zimmerli, B. Relevance of in vitro tests of adhesive and composite dental materials, a review in 3 parts. Part 1: Approval requirements and standardized testing of composite materials according to ISO specifications. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed 2011, 121, 804–816. [Google Scholar]

- Ilie, N. ISO 4049 versus NIST 4877: Influence of stress configuration on the outcome of a three-point bending test in resin-based dental materials and interrelation between standards. Journal of dentistry 2021, 110, 103682–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore BK, Platt JA, Borges G, et al. Depth of cure of dental resin composites: ISO 4049 depth and microhardness of types of materials and shades. Operative dentistry 2008, 33, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang N and Xie, C. Polymerization shrinkage, shrinkage stress, and mechanical evaluation of novel prototype dental composite resin. Dental materials journal 2020, 39, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, FJ. The evidence base for ‘own label’ resin-based dental restoratives. Dent Update 2013, 40, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaiman K, Ortega D and Garnache C. Consumer preferences and demand for packaging material and recyclability. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2016, 115. [CrossRef]

- Mallinson DJ and Hatemi, PK. The effects of information and social conformity on opinion change. PloS one 2018, 13, e0196600–20180502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megremis, SJ. Assuring the Safety of Dental Materials: The Usefulness and Application of Standards. Dental clinics of North America 2022, 66, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal R, Maheshwari R, Tripathi S, et al. Eco-friendly dentistry: Preventing pollution to promoting sustainability. Indian Journal of Dental Sciences 2020, 12, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudnikov Y and Nazarenko A. The role of content marketing in the promotion of medical goods and services. 2021.

- Zaware PDN. Exploration of market potential towards dental material brands: An assessment with preferences of dentists in India. Available at SSRN 3819251 2020.

- Bujang MA, Omar E, Foo D, et al. Sample size determination for conducting a pilot study to assess reliability of a questionnaire. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics 2024, 49. [CrossRef]

- Hussey I, Alsalti T, Bosco F, et al. An Aberrant Abundance of Cronbach’s Alpha Values at.70. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 2025, 8, 25152459241287123. [CrossRef]

- Tavakol M and Dennick, R. Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. International Journal of Medical Education 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal AA, Prakash N, Almagbol M, et al. Synoptic review on existing and potential sources for bias in dental research methodology with methods on their prevention and remedies. World journal of methodology 2023, 13, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, AK. Controlling bias in research. Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society 2022, 22, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo Júnior, JP. Social desirability bias in qualitative health research. Revista de saude publica 2022, 56, 101–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latkin CA, Edwards C, Davey-Rothwell MA, et al. The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addictive behaviors 2017, 73, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo M, Wang Y, Yang Q, et al. Normal Workflow and Key Strategies for Data Cleaning Toward Real-World Data: Viewpoint. Interactive journal of medical research 2023, 12, e44310–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan P and Hunsberger, S. Handling missing data in research. Perspectives in clinical research 2024, 15, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed I and Ishtiaq, S. Reliability and validity: Importance in Medical Research. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2021, 71, 2401–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta A, Naka O, Mehta SB, et al. The clinical performance of bulk-fill versus the incremental layered application of direct resin composite restorations: a systematic review. Evidence-based dentistry 2023, 24, 143–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesterman J, Jowett A, Gallacher A, et al. Bulk-fill resin-based composite restorative materials: A review. BDJ 2017, 222, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos JD, Nakano LJ, Scalzer G, et al. Characterization of Bulk-Fill Resin Composites in Terms of Physical, Chemical, Mechanical and Optical Properties and Clinical Behavior. International Journal of Odontostomatology 2021, 15, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka N and Brizuela M. Glass Ionomer Cement. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Melina Brizuela declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2025.

- Ulku SG and Unlu, N. Factors influencing the longevity of posterior composite restorations: A dental university clinic study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27735–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz J, Wilhelm C, Urich J, et al. Different Esthetic Assessment of Anterior Restorations by Patient and Expert: A Prospective Clinical Study. Journal of esthetic and restorative dentistry: official publication of the American Academy of Esthetic Dentistry [et al] 2024 2024/12/27. [CrossRef]

- Al-Asmar AA, Al-Hiyasat AS, Abu-Awwad M, et al. Reframing Perceptions in Restorative Dentistry: Evidence-Based Dentistry and Clinical Decision-Making. International journal of dentistry 2021, 2021, 4871385–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotto LPS, Dotto L, Pereira GKR, et al. Restorative preferences and choices of dentists and students for restoring endodontically treated teeth: A systematic review of survey studies. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry 2021, 126, 489–489.e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzolotto L and Moraes RR. Resin Composites in Posterior Teeth: Clinical Performance and Direct Restorative Techniques. Dentistry journal 2022, 10 2022/12/23. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Caussin E, Izart M, Ceinos R, et al. Advanced Material Strategy for Restoring Damaged Endodontically Treated Teeth: A Comprehensive Review. Materials 17(15)(2024).

- Murchie B, Jiwan N and Edwards D. What are the success rates of anterior restorations used in localised wear cases? Evidence-based dentistry 2025, 26, 54–56. [CrossRef]

- Ille CE, Jivănescu A, Pop D, et al. Exploring the Properties and Indications of Chairside CAD/CAM Materials in Restorative Dentistry. Journal of functional biomaterials 2025, 16 2025/02/25. [CrossRef]

- Barakat B, Milhem M, Naji GM, et al. Assessing the Impact of Green Training on Sustainable Business Advantage: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Supply Chain Practices. Sustainability 15(19)(2023).

- Kaurani P, Batra K, Rathore Hooja H, et al. Assessing the Compliance of Dental Clinicians towards Regulatory Infection Control Guidelines Using a Newly Developed Survey Tool: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study in India. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 10 2022/10/28. [CrossRef]

- Boulding H and Hinrichs-Krapels, S. Factors influencing procurement behaviour and decision-making: an exploratory qualitative study in a UK healthcare provider. BMC Health Services Research 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou M, Chrysochoou G, Tzanetopoulos R, et al. Green Dental Environmentalism among Students and Dentists in Greece. Sustainability 15(12)( 2023.

- Beske-Janssen P, Johnsen T, Constant F, et al. New competences enhancing Procurement’s contribution to innovation and sustainability. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 2023, 29, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes E, Bullock AD, Bailey SE, et al. A review of continuing professional development for dentists in Europe(*). European journal of dental education: official journal of the Association for Dental Education in Europe 2013, 17 Suppl 1, 5-17. 2013/04/23. [CrossRef]

- Țâncu AMC, Imre M, Iosif L, et al. Is Sustainability Part of the Drill? Examining Knowledge and Awareness Among Dental Students in Bucharest, Romania. Dentistry journal 2025, 13 2025/03/26. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou M, Intzes A, Kladouchas C, et al. Factors Affecting Water Quality and Sustainability in Dental Practices in Greece. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichenin J, Vallaeys K, Arbab Chirani R, et al. How does gender influence student learning, stress and career choice in endodontics? International endodontic journal 2025 2025/03/14. [CrossRef]

- Wolbring G and Nguyen, A. Equity/Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, and Other EDI Phrases and EDI Policy Frameworks: A Scoping Review. Trends in Higher Education 2(1)( 2023. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sbei R, Ataya J, Jamous I, et al. The Impact of a Web-Based Restorative Dentistry Course on the Learning Outcomes of Dental Graduates: Pre-Experimental Study. JMIR formative research 2024, 8, e51141–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang YM and Chang, YC. Initiating gender mainstreaming in dentistry. Journal of dental sciences 2022, 17, 1411–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe A, Roberts TE, Ives JC, et al. Centre selection for clinical trials and the generalisability of results: a mixed methods study. PloS one 2013, 8, e56560–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino CM and Ferreira, JC. Inclusion and exclusion criteria in research studies: definitions and why they matter. Jornal brasileiro de pneumologia: publicacao oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisilogia 2018, 44, 84–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgerson DJ and Torgerson, CJ. Pilot Randomised Controlled Trials. In: Torgerson DJ and Torgerson CJ (eds) Designing Randomised Trials in Health, Education and the Social Sciences: An Introduction. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2008, pp.119-126.

- Leon AC, Davis LL and Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. Journal of psychiatric research 2011, 45, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2010, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallingberg B, Turley R, Segrott J, et al. Exploratory studies to decide whether and how to proceed with full-scale evaluations of public health interventions: a systematic review of guidance. Pilot and Feasibility Studies 2018, 4, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein M, Al-Nawas B, Kuchler U, et al. Consensus Statements and Recommended Clinical Procedures Regarding Contemporary Surgical and Radiographic Techniques in Implant Dentistry. The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants 2014, 29, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Gender (female vs male dentists) |

Age (over 45 years vs younger) |

Dental school (foreign vs domestic) |

Postgrad studies in Dentistry |

Clinical experience (over 5 years vs up to 5 years) |

Employment (private clinic vs other) |

Purchasing resin restorations over 2 times/year |

Not responsible for supply of resin restorations |

Performing over 20 composite resin restorations per week. | |

| Knowledge about resin materials | -0.152 | .236* | 0.118 | 0.175 | .214* | 0.055 | 0.062 | -0.052 | 0.195 |

| 1. Composition | -0.085 | 0.163 | 0.118 | 0.164 | .230* | -0.044 | 0.061 | -0.153 | 0.206 |

| 2. Biocompatibility | -.248* -0.084 -0.024 -0.012 -0.165 |

0.045 0.135 0.208 .214* 0.137 |

0.158 -0.052 0.116 0.107 0.072 |

0.138 0.072 0.039 0.186 0.161 |

-0.014 0.033 .223* 0.159 0.177 |

-0.015 -0.041 0.170 0.028 0.097 |

0.129 0.072 0.110 -0.164 -0.099 |

0.098 0.179 -0.145 0.039 -0.115 |

0.081 0.041 0.149 0.100 0.141 |

| 3. Side effects 4. Shelf life 5. Method of application 6. Type of material |

| N | % | ||

| Familiarity with specifications for dental resin restorative materials | Yes | 55 | 71.4% |

| No | 22 | 28.6% | |

| Importance of resin restorative material compliance with specifications | Very high | 28 | 32.2% |

| High | 47 | 54.0% | |

| Moderate | 12 | 13.8% | |

| Features priority when choosing resin restorative materials | Biocompatibility | 21 | 25.9% |

| Photopolymerization depth | 13 | 16.0% | |

| Bending strength | 28 | 34.6% | |

| Water absorbency, Solubility, etc. | 19 | 23.5% | |

| Green practice but falls slightly short of some of the ISO specifications | Certainly yes | 4 | 4.9% |

| It depends on the specifications | 45 | 54.9% | |

| No, for me ISO standards are the most important selection criterion | 33 | 40.2% |

| Total sample | Clinical experience (in years) | |||||

| up to 5 years | over 5 years | |||||

| N | % | N | % | |||

|

What are the selection criteria for the resin materials you choose for anterior tooth restorations? | ||||||

| It depends on the anatomical features I want to achieve It depends on the interdental space that exists |

47 |

54.0% |

31 |

70.5% |

16 |

37.2% |

| 14 | 16.1% | 10 | 22.7% | 4 | 9.3% | |

| It depends on the color of the neighboring teeth | 44 | 50.6% | 25 | 56.8% | 19 | 44.2% |

| It depends on the transparency and opacity of the neighboring teeth | 49 | 56.3% | 29 | 65.9% | 20 | 46.5% |

| I do not have a specific criterion, I use what I have in stock | 6 | 6.9% | 4 | 9.1% | 2 | 4.7% |

| I only use special anterior resins | 32 | 36.8% | 10 | 22.7% | 22 | 51.2% |

| What are the selection criteria for the resin materials you choose for posterior tooth restorations? | ||||||

| It depends on the anatomical features I want to achieve | 48 | 55.2% | 29 | 65.9% | 19 | 44.2% |

| It depends on the interdental space that exists | 24 | 27.6% | 15 | 34.1% | 9 | 20.9% |

| It depends on the color of the neighboring teeth | 25 | 28.7% | 14 | 31.8% | 11 | 25.6% |

| I do not have a specific criterion, I use what I have in stock | 24 | 27.6% | 10 | 22.7% | 14 | 32.6% |

| Selection criteria for the resin materials |

Gender (female vs male) |

Age (over 45 years) |

Dental school (foreign vs domestic) |

Postgrad studies in dentistry |

Clinical experience (>5 years) |

Employment (private clinic vs other) | Purchasing resin restorations over 2 times/year | Not responsible for supply of resin restorations | Performing over 20 restorations/ week |

| What are the selection criteria for the resin materials you choose for anterior tooth restorations? | |||||||||

| It depends on the anatomical features I want to achieve | -0.043 | -0.204 | 0.055 | -0.134 | -.334** | -0.090 | 0.021 | 0.120 | -.315** |

| It depends on the interdental space that exists | -0.108 | -0.054 | -0.117 | -0.020 | -0.183 | 0.017 | 0.044 | 0.112 | -0.071 |

| It depends on the color of the neighboring teeth | 0.080 | -0.105 | 0.025 | -0.127 | -0.126 | 0.033 | 0.166 | 0.017 | -0.160 |

| It depends on the transparency and opacity of the neighboring teeth | 0.185 | -.239* | -0.028 | -0.076 | -0.196 | -0.188 | 0.090 | 0.040 | -0.164 |

| I do not have a specific criterion, I use what I have in stock | -0.028 | -0.007 | -0.124 | 0.068 | -0.088 | 0.154 | -0.085 | 0.014 | 0.126 |

| I only use special anterior resins | 0.017 | 0.199 | 0.030 | .337** | .295** | -0.127 | 0.004 | -0.151 | 0.113 |

| What are the selection criteria for the resin materials you choose for posterior tooth restorations? | |||||||||

| It depends on the anatomical features I want to achieve | 0.071 | -0.173 | 0.044 | 0.085 | -.218* | -0.162 | 0.105 | 0.055 | -0.133 |

| It depends on the interdental space that exists | 0.091 | -0.123 | -0.077 | -0.058 | -0.147 | -0.012 | 0.142 | -0.025 | -0.037 |

| It depends on the color of the neighboring teeth | -0.041 | 0.020 | -0.021 | 0.132 | -0.069 | 0.164 | 0.178 | -0.097 | -0.057 |

| I do not have a specific criterion; I use what I have in stock | -0.116 | -0.015 | -0.009 | -0.164 | 0.110 | 0.039 | -0.192 | 0.086 | -0.018 |

| I do not know / do not answer | 0.097 | -0.078 | -0.049 | -0.084 | -0.107 | 0.097 | -0.072 | -0.072 | -0.083 |

| Gender (female vs male) | Age (over 45 years) | Dental school (foreign vs domestic) | Post-grad studies in dentistry | Clinical experience (over 5 years) | Employment (private clinic vs other) | Purchasing resin restorations over 2 times/year | Not responsible for supply of resin restorations | Performing over 20 restorations/ week | |

| Familiarity with specifications | -0.033 | 0.076 | 0.132 | -0.108 | .231* | -0.041 | .254* | -.341** | 0.163 |

| Specifications importance | 0.109 | 0.150 | 0.094 | 0.038 | 0.195 | -0.025 | 0.052 | -0.092 | 0.095 |

| Features priority when choosing resin restorative materials | |||||||||

| Biocompatibility | .232* | 0.136 | 0.177 | 0.213 | 0.106 | -0.106 | -0.105 | 0.093 | -0.026 |

| Photopolymerization depth | -0.162 | -0.084 | -0.022 | -0.147 | 0.050 | -0.117 | -0.084 | -0.001 | 0.113 |

| Bending strength | -0.204 | -0.111 | 0.011 | -0.056 | -.233* | 0.181 | 0.112 | -0.092 | -0.078 |

| Water absorbency, Solubility, etc. | 0.130 | 0.056 | -0.176 | -0.030 | 0.108 | 0.009 | 0.056 | 0.009 | 0.019 |

| Green practice but falls slightly short of some of the ISO specifications | |||||||||

| Certainly yes | 0.092 | 0.181 | 0.066 | 0.057 | 0.113 | -0.028 | 0.211 | -0.021 | 0.182 |

| It depends on the specifications | 0.114 | -0.176 | 0.029 | -0.001 | -0.025 | -0.061 | -0.172 | 0.099 | 0.020 |

| No, for me ISO standards are the most important selection criterion | -0.155 | 0.099 | -0.058 | -0.024 | -0.025 | 0.075 | 0.082 | -0.091 | -0.102 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).