1. Introduction

Declared in November 2017 [

1], Revillagigedo National Park (RNP) encompasses over 14,000 km

2 of ocean surrounding four volcanic islands—Socorro, San Benedicto, Roca Partida, and Clarión—located approximately 390 km southwest of Baja California Sur. North America’s largest no-take marine reserve provides a critical refuge for a wide range of pelagic megafauna, including several shark species and the oceanic manta ray (

Mobula birostris) [

1,

2].

Since its designation, RNP has shown promising signs of ecological improvement. By minimizing fishing pressure and preserving essential habitats, large marine protected areas (MPAs), such as RNP, may foster conditions conducive to observing infrequent or context-dependent behaviors [

3,

4]. Such protections can be especially valuable in remote pelagic ecosystems where consistent diver presence and well-managed habitats improve the likelihood of documenting infrequent interspecies interactions.

RNP’s cleaning stations at Socorro, San Benedicto, and Roca Partida islands are well known for hosting interactions where reef fishes remove ectoparasites from large pelagic species, including sharks and oceanic manta rays [

2,

5,

6,

7]. While several shark species—such as Galapagos and scalloped hammerheads—have been observed participating in these interactions, formal documentation of cleaning or chafing involving tiger sharks remains absent from the literature.

Chafing behavior in elasmobranchs—rubbing the body against substrates—is generally interpreted as a mechanism for ectoparasite removal and skin or reproductive organ maintenance, particularly in sensitive areas such as the head, gills, and lateral surfaces [

8,

9]. This has been documented in species like scalloped hammerhead sharks, which have been observed scraping their flanks and claspers on sandy bottoms [

10], as well as ocellated eagle rays [

11] and Caribbean reef and blacktip sharks using sand ripples to enhance chafing [

12]. While these studies highlight the use of abiotic substrates, peer-reviewed reports of sharks chafing against other marine animals remain scarce. Recent observations of juvenile Galapagos sharks (

Carcharhinus galapagensis) chafing against whale sharks (

Rhincodon typus) [

7] suggest that species-specific dynamics and ecological context may influence these interactions. However, the function of such interspecific behaviors—especially those involving potential predator-prey relationships, such as with manta rays—remains poorly understood despite growing recognition of chafing as ecologically significant across marine taxa.

Here, we report a novel interaction between an adult tiger shark and an adult oceanic manta ray, representing the first documented instance of chafing behavior in this apex predator. When considered alongside our additional observations involving Galapagos sharks, as well as those recently described in a preprint by Vinesky et al. [

13], these findings suggest that non-predatory physical interactions between sharks and oceanic manta rays may represent a previously underrecognized behavioral pattern. Our findings provide new insight into the ecological relationships between sharks and oceanic manta rays and underscore the importance of well-protected ecosystems for revealing rare or context-dependent interactions.

2. Materials and Methods

Observations were conducted in December 2024 and February 2025 at RNP during routine monitoring activities. Behavioral interactions between sharks and manta rays were opportunistically and non-invasively recorded at two dive sites – “The Boiler”, located off the northwest coast of San Benedicto Island, and “The Canyon”, situated off the island’s southern end. High-definition GoPro Hero 10 cameras were operated by divers at depths ranging from approximately 10-20 meters.

Video footage capturing interactions between

Mobula birostris and carcharhinid sharks was reviewed and analyzed to identify chafing behavior. For this study, chafing was defined as sustained physical contact initiated by the shark, directed at the manta ray’s body surfaces – typically along the dorsal, lateral, or ventral regions – and targeting areas known to be prone to ectoparasite accumulation, such as the head, gills, pectoral fins, and body flanks, outlined by Williams et al. [

8] and Thompson & Meeuwig [

9].

Sex and maturity were estimated through visual assessment of external features in the video footage: manta ray sex and maturity were identified based on the presence and calcification of claspers extending beyond the pelvic fins [

14], and shark maturity was estimated using body size and clasper morphology following published species-specific thresholds [

15,

16].

To contextualize the behavioral observations, we reviewed relevant literature on chafing behavior documented in carcharhinid sharks, with particular attention to interspecies interactions [

7,

8,

9].

3. Results

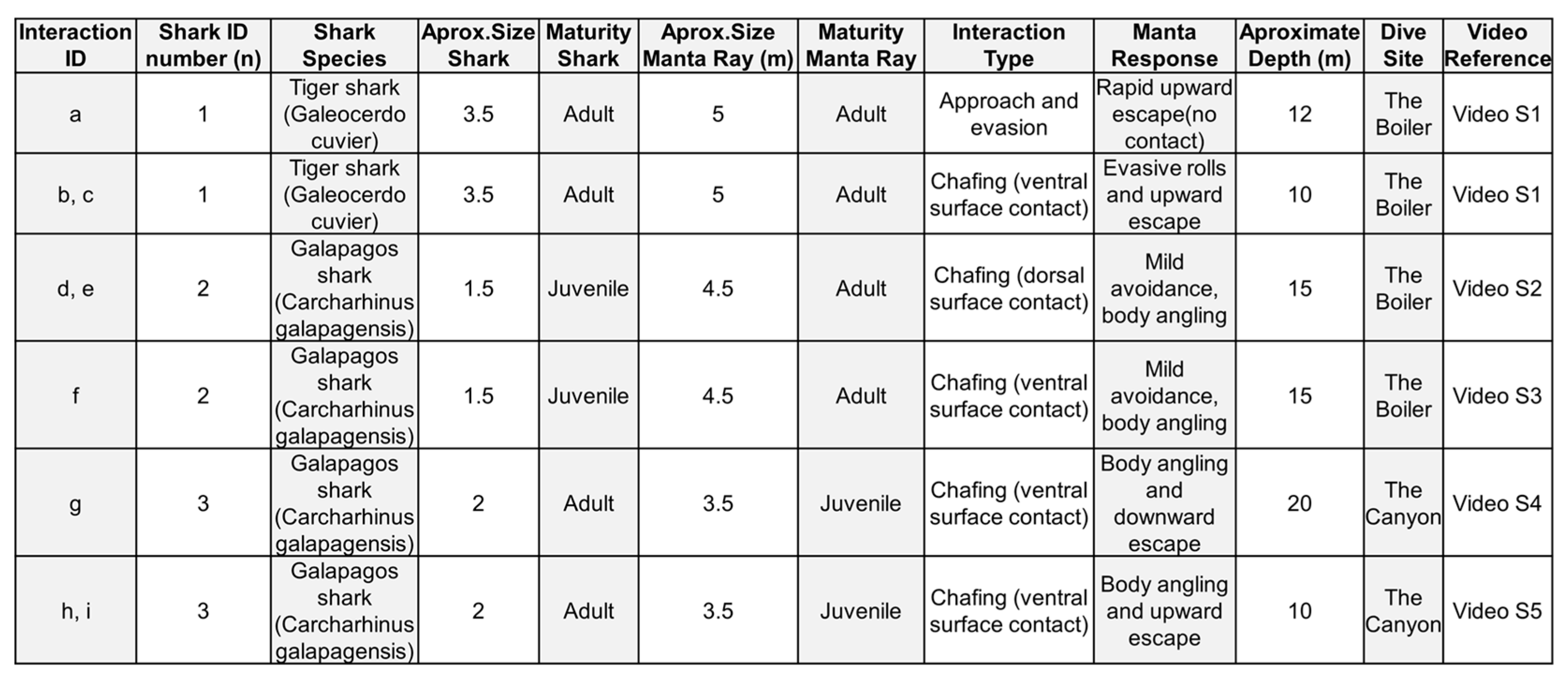

We documented four opportunistic interactions between carcharhinid sharks (

n = 3) and oceanic manta rays (

n = 4) at two dive sites – The Boiler and The Canyon – located off San Benedicto Island in RNP. The observed interactions included one involving a juvenile Galapagos shark, one involving an adult Galapagos shark, and two separate interactions between an adult tiger shark and two adult manta rays. All encounters were initiated at depths ranging from approximately 10 to 20 meters (

Appendix A, Table A1).

The tiger shark footage (

Figure 1a-c) captured two distinct interactions with separate adult manta rays. In the first (

Figure 1a), the manta ray quickly evaded the approaching shark by swimming toward the surface. In the second (

Figure 1b–c), the tiger shark pursued a female manta ray in an interaction that lasted approximately 20 seconds, during which it made repeated physical contact by scraping its rostrum and lateral body along the manta ray’s pectoral fins and ventral surface, while also performing lateral flexing. The manta ray responded with two backward rolls and an upward escape.

In the first Galapagos shark interaction (

Figure 1d-f), a juvenile shark engaged in chafing behavior involving both the dorsal (

Figure 1d-e) and ventral surfaces (

Figure 1f) of the manta ray. The manta ray’s response was limited to slight postural adjustments, primarily body angling. In the second Galapagos interaction (

Figure 1g-i), an adult male shark approached a juvenile female manta ray. The manta ray initially shifted downward in response (

Figure 1g), followed by pronounced body angling and an upward movement (

Figure 1h-i) as the shark continued to pursue. Both interactions lasted approximately 8-12 seconds and involved discrete bouts of contact, during which the shark scraped its rostrum and lateral body against the manta ray.

Manta ray responses across the four interactions ranged from mild avoidance (e.g., postural adjustment) to active evasion (e.g., swimming upward) and defensive behaviors (e.g., backward rolls and escape movements) (

Appendix A, Table A1). Both tiger shark interactions corresponded with stronger manta ray responses, including evasive and defensive movements, even though only one involved sustained physical contact and chafing behavior. In contrast, the Galapagos shark interactions were shorter in duration: the juvenile shark prompted only slight postural adjustments, such as body angling, while the adult shark triggered a more pronounced evasive response. At no point during any of the interactions did the sharks exhibit gape displays or behaviors indicative of a biting attempt.

4. Discussion

These observations offer a rare glimpse into the behavioral diversity of carcharhinid sharks, revealing non-predatory interactions with large manta rays that remain undocumented in the peer-reviewed literature. They provide new insight into complex interspecies dynamics between apex predators, mesopredators, and large zooplanktivores in pelagic ecosystems.

Typically interpreted as a form of ectoparasite removal or skin maintenance, chafing behavior in sharks often involves contact with conspecifics, reef substrates, or large-bodied marine fauna [

8,

9]. Chafing behavior involving Galapagos and grey reef sharks interacting with whale sharks has been recently documented [

7,

17], suggesting that such interspecific associations may be more widespread and ecologically relevant than previously recognized.

The four interactions we observed – two involving an adult tiger shark and two involving Galapagos sharks - represent a novel context for this interspecies behavior. In these events, manta rays exhibited stronger evasive and defensive responses toward adult tiger and Galapagos sharks—such as rapid escape maneuvers—whereas responses to the juvenile Galapagos shark were more subdued and limited to postural adjustments. The heightened reactions toward tiger sharks may reflect their role as apex predators known to prey on juvenile manta rays, particularly targeting smaller or immature individuals [

14,

18,

19]. In contrast, Galapagos sharks are mesopredators that primarily consume teleosts, cephalopods, and smaller elasmobranchs [

15] and are not known to prey on manta rays. Variation in manta ray responses highlights how predator identity, body size, and behavioral persistence influence interspecies interactions, suggesting that perceived threat plays a central role in shaping interspecific dynamics.

The tiger shark’s behavior did not appear to exhibit typical signs of predatory pursuit—such as rapid acceleration or direct targeting—and showed no jaw gaping or biting attempts, suggesting non-predatory motivations like chafing, agonistic behavior, or context-dependent communication. Lateral flexing may reflect an agonistic display, a behavior commonly used by elasmobranchs to signal dominance without escalating to physical conflict [

20], and may have occurred concurrently with the chafing interaction. This suggests a degree of behavioral plasticity that is not yet well understood for apex predators.

Chafing behavior observed in both tiger and Galapagos sharks may function as an alternative strategy for ectoparasite removal—potentially offering more localized, targeted, or intensive contact than the services typically provided by cleaner fish at established cleaning stations. While cleaner species, such as wrasses (

Labridae) and butterflyfish (

Chaetodontidae), regularly remove ectoparasites from a variety of elasmobranch hosts [

21], their cleaning behavior is inherently selective, both in spatial coverage and parasite type, which may not align with the specific needs of the shark. Physical interactions with manta rays could, therefore, enable sharks to focus contact on particular areas of irritation or high parasite load, offering a more deliberate and potentially complementary cleaning mechanism through interspecific association. This interpretation is supported by the observed positioning and contact patterns, which suggest a targeted form of parasite removal, particularly concentrated on the rostrum and lateral body surfaces. In addition, social dynamics at cleaning stations—such as competitive exclusion by larger individuals—may limit access for juvenile or subdominant sharks, further encouraging the use of alternative strategies like chafing on manta rays. Such interactions, observed in both the tiger and the Galapagos sharks, may represent an underrecognized ecological strategy that expands the functional role of interspecific associations in marine systems and highlights their behavioral flexibility.

One contributing factor to the emergence or documentation of rare shark behaviors may be the ecological conditions fostered by well-enforced MPAs. Large no-take reserves, such as RNP, are increasingly recognized for supporting predator presence and behavioral expression by minimizing fishing pressure and preserving key habitats [

22,

23]. Such protections may enhance opportunities to observe infrequent behaviors by promoting predator abundance, reducing human disturbance, and stabilizing species assemblages. Notably, both our observations and those reported by Pancaldi et al. [

7] and Gobbato et al. [

19] occurred within MPAs, emphasizing the role that well-managed marine reserves may play in revealing under-recognized or previously undocumented ecological interactions. Similar trends have been observed in other well-managed MPAs, such as Ashmore Reef in northwestern Australia, where shark abundance increased significantly within a decade of no-take protection [

24]. Long-term conservation efforts have also supported evidence of population stability or positive trends in apex and mesopredator sharks, including tiger sharks (

Galeocerdo cuvier) in the Bahamas and the northwestern Atlantic [

4,

25]. These examples highlight how ecological recovery within effectively managed MPAs can provide critical context for the emergence and observation of novel predator behaviors.

In addition, as tiger and Galapagos sharks become increasingly habituated to diver presence in protected environments, the frequency of such interactions may also increase. However, the absence of comprehensive data on shark population trends in RNP underscores the need for targeted research to evaluate the ecological effects of MPA status—particularly in assessing how enhanced protection may be influencing population trends and behavioral expression in both tiger and Galapagos sharks.

Our observations contribute to the growing body of knowledge on shark behavioral ecology, particularly in the context of non-feeding interactions involving sympatric megafauna. Understanding the ecological and evolutionary significance of such behaviors may help clarify the roles of apex and mesopredator species in pelagic ecosystems and inform management priorities in protected areas.

Given these insights, there is a clear need for expanded behavioral research in recovering marine ecosystems. Targeted studies, long-term monitoring, and comparative work across trophic levels and habitat types will be essential to determine whether such interactions are isolated events or part of a broader, understudied repertoire of social or maintenance-related behaviors in sharks.