Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tissue Samples

2.2. Thyroid Cell Culture and Transfection Experiments

2.3. Luciferase Reporter Assay

2.4. Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Amplification

2.5. Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy

2.6. Immunoblotting

2.7. Viability Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

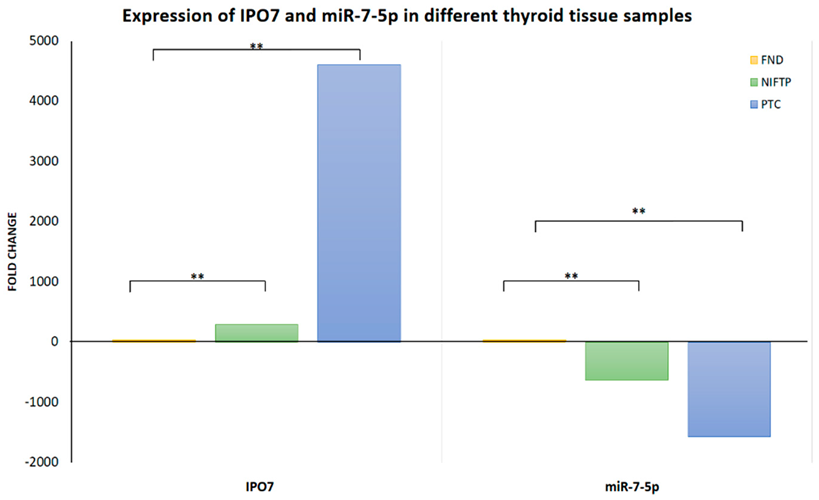

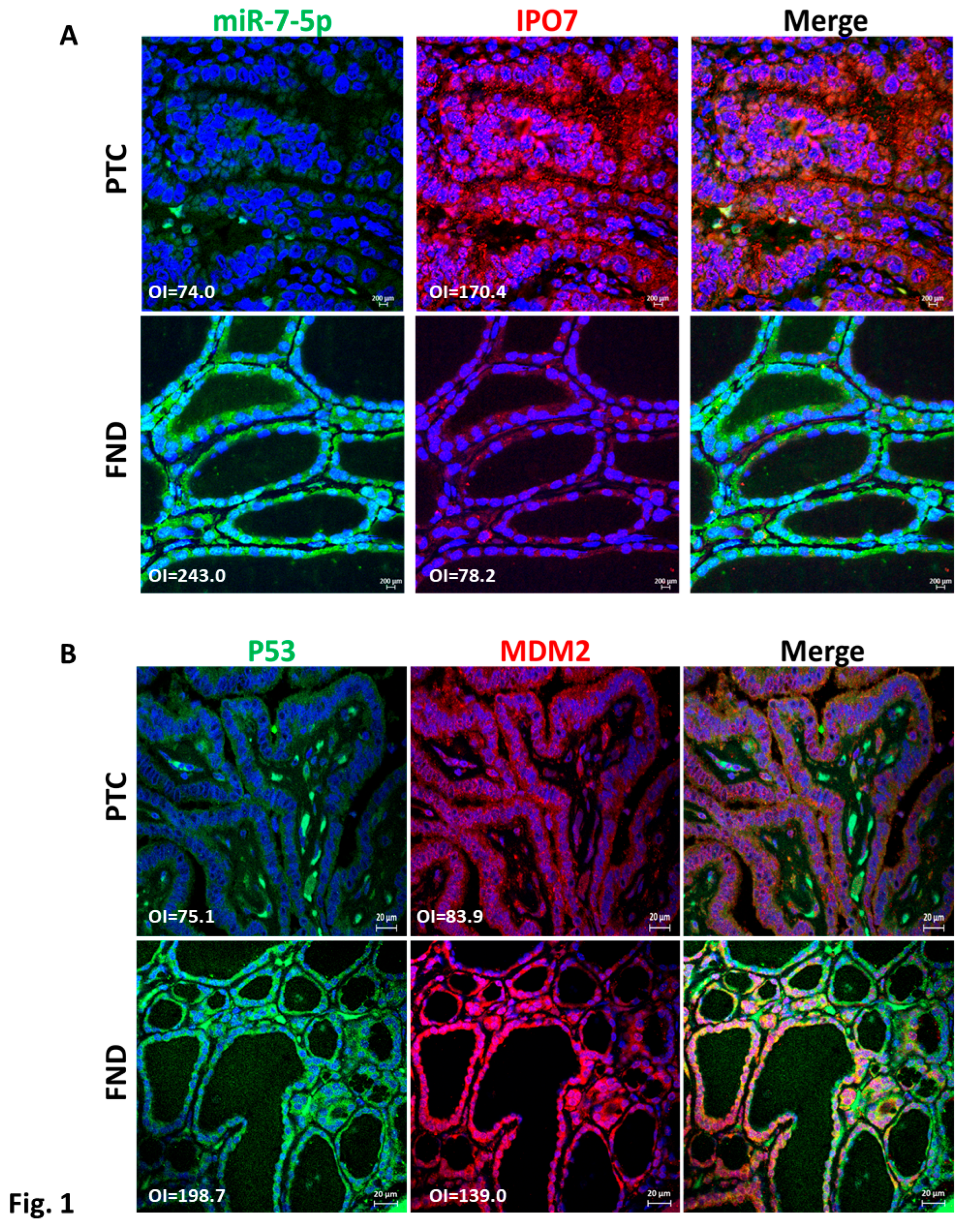

3.1. Expression of IPO7 and p53 in PTC Clinical Samples

|

3.2. p53 Activity Is Suppressed in PTC and Is Rescued by miR-7-5p Gain of Function

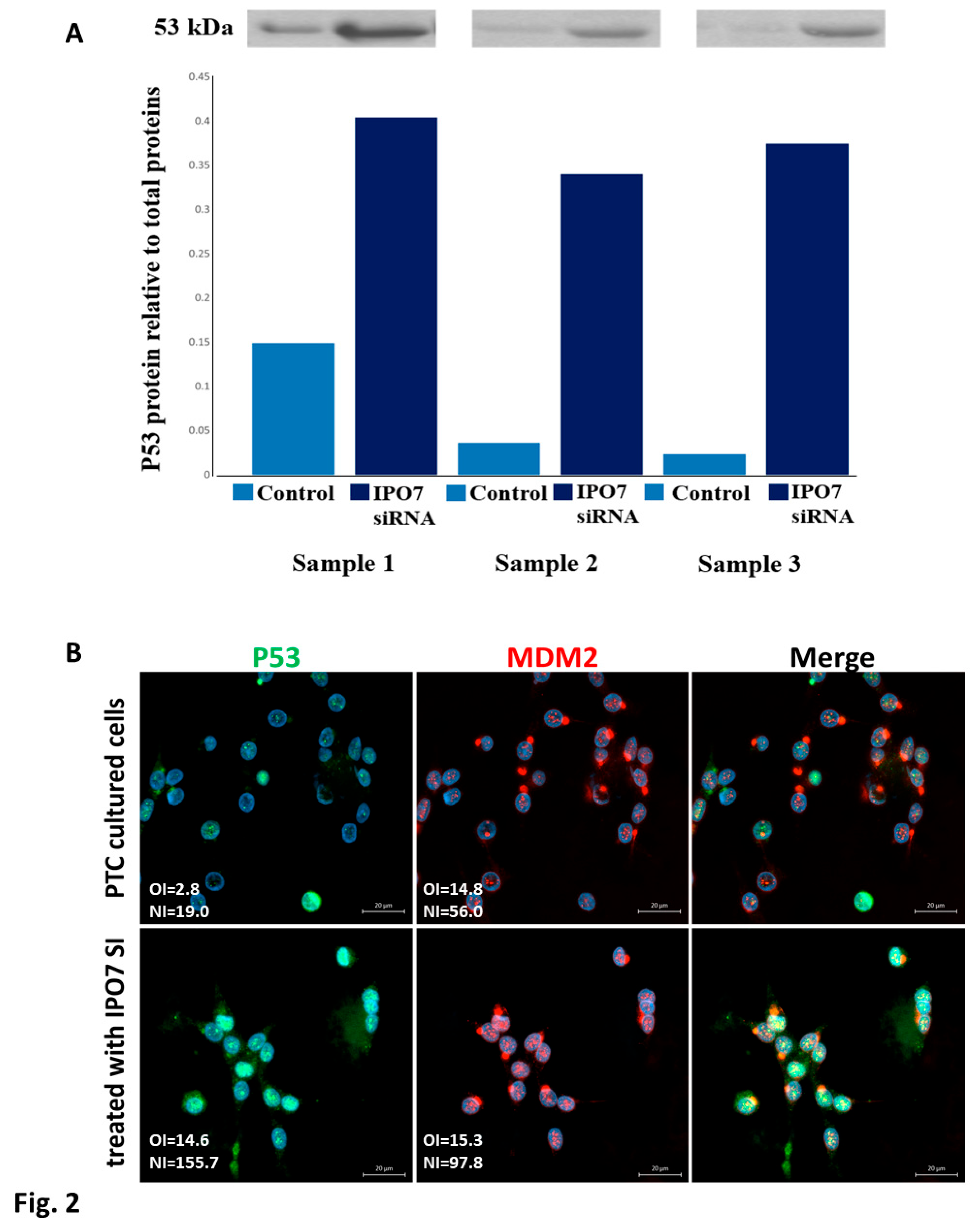

3.3. IPO7 Partial Depletion Increased the Availability of p53 Protein and the Nuclear Colocalization of MDM2 with the Ribosomal Proteins RPL11 and RPL5 in Primary Cultured PTC Cells

3.4. p53 Regulation by miR-7-5p/IPO7 in the Normal Thyroid Cell Line Nthy-ori 3-1

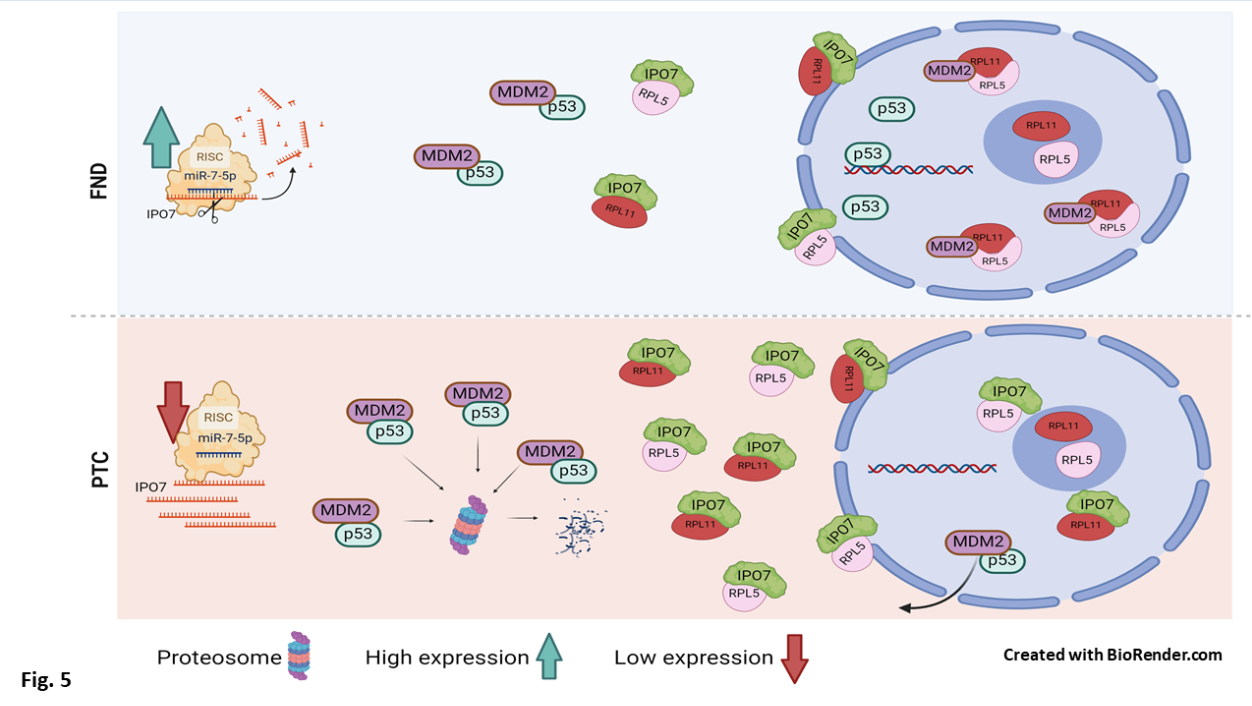

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lim, H.; Devesa, S.S.; Sosa, J.A.; Check, D.; Kitahara, C.M. Trends in Thyroid Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA 2017, 317, 1338–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Thyroid Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/thyroid-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Limaiem, F.; Rehman, A.; Mazzoni, T. Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536943/.

- Wang, Z.; Ji, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, W. Clinical and molecular features of progressive papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 2313–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, H.G.; Altibi, A.M.; Abdelhamid, A.H.; Ngoc, P.U.; Quan, V.D.; Tantawi, M.Y.; Elfil, M.; Vu, T.L.; Elgebaly, A.; Oishi, N.; Nakazawa, T.; Hirayama, K.; Katoh, R.; Huy, N.T.; Kondo, T. The changing characteristics and molecular profiles of papillary thyroid carcinoma over time: a systematic review. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 10637–10649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Ku, B.M.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Lim, S.H.; Sun, J.M.; Lee, S.H.; Park, K.; Oh, Y.L.; Hong, M.; Jeong, H.S.; Son, Y.I.; Baek, C.H.; Ahn, M.J. Genetic Alterations and Their Clinical Implications in High-Recurrence Risk Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Cancer Res Treat 2017, 49, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, S.; Alix-Panabières, C.; Alaei, A.S.; Abooshahab, R.; Shakib, H.; Ashrafi, M.R. Looking at Thyroid Cancer from the Tumor-Suppressor Genes Point of View. Cancers 2022, 14, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donghi, R.; Longoni, A.; Pilotti, S.; Michieli, P.; Della Porta, G.; Pierotti, M.A. Gene p53 mutations are restricted to poorly differentiated and undifferentiated carcinomas of the thyroid gland. J. Clin. Investig. 1993, 91, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Guo, M.; Wei, H.; et al. Targeting p53 pathways: mechanisms, structures, and advances in therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S. Papillary Thyroid Cancer Remodels the Genetic Information Processing Pathways. Genes 2024, 15, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbani, I.; Al-Abdallah, A.; Ali, R.H.; Al-Brahim, N.; Mojiminiyi, O. Discriminatory miRNAs for the Management of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma and Noninvasive Follicular Thyroid Neoplasms with Papillary-Like Nuclear Features. Thyroid 2018, 28, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdallah, A.; Jahanbani, I.; Ali, R.H.; Al-Brahim, N.; Prasanth, J.; Al-Shammary, B.; Al-Bader, M. A new paradigm for epidermal growth factor receptor expression exists in PTC and NIFTP regulated by microRNAs. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1080008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Martínez, M.; Vega, M.I. Role of MicroRNA-7 (MiR-7) in Cancer Physiopathology. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, K.; Jin, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, B.; Wu, C.; Xu, H.; Fang, L. MicroRNA-7 inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion of thyroid papillary cancer cells by targeting CKS2. International Journal of Oncology 2016, 49, 1531–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, K.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, X.; He, Q.; Duan, Y. microRNA-7 regulates cell growth, migration and invasion via direct targeting of PAK1 in thyroid cancer. Mol Med Rep 2016, 14, 2127–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; et al. MicroRNA-7 inhibits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of breast cancer cells by targeting FAK expression. PLoS One 2012, e41523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajda, E.; Grzanka, M.; Godlewska, M.; Gawel, D. The Role of miRNA-7 in the Biology of Cancer and Modulation of Drug Resistance. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, X.; Wu, C.W.; Dong, Y.; Cai, M.; Mok, M.T.S.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Ng, S.S.M.; Chen, M.; et al. microRNA-7 is a novel inhibitor of YY1 contributing to colorectal tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2012, 32, 5078–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Ni, L.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Q.; Su, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, W.; Wu, X.; Ye, J.; Yang, S.; et al. Identification of miR-7 as an oncogene in renal cell carcinoma. J Mol Histol 2013, 44, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.-F.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chou, Y.-T.; Wu, C.-W. MicroRNA-7 Compromises p53 Protein-dependent Apoptosis by Controlling the Expression of the Chromatin Remodeling Factor SMARCD1. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 1877–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.T.; Lin, H.H.; Lien, Y.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Hong, C.F.; et al. EGFR promotes lung tumorigenesis by activating miR-7 through a Ras/ERK/Myc pathway that targets the Ets2 transcriptional repressor ERF. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 8822–8831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görlich, D.; Kutay, U. Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 1999, 15, 607–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, K.; Seger, R. Stimulated nuclear import by β-like importins. F1000Prime Rep 2013, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, M.Y.; Parish, C.R.; Chong, B.H.; Khachigian, L. Nuclear import of early growth response-1 involves importin-7 and the novel nuclear localization signal serine-proline-serine. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2011, 43, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chachami, G.; Paraskeva, E.; Mingot, J.; Braliou, G.G.; Görlich, D.; Simos, G. Transport of hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1alpha into the nucleus involves importins 4 and 7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009, 390, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldmann, I.; Wälde, S.; Kehlenbach, R.H. Nuclear import of c-Jun is mediated by multiple transport receptors. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 27685–27692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Chen, X.; Cottonham, C.; Xu, L. Preferential utilization of Imp7/8 in nuclear import of Smads. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 22867–22874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağatay, T.; Chook, Y.M. Karyopherins in cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2018, 52, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.R.; Gyselman, V.G.; Dorudi, S.; Bustin, S.A. Elevated levels of RanBP7 mRNA in colorectal carcinoma are associated with increased proliferation and are similar to the transcription pattern of the proto-oncogene c-myc. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000, 271, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Zhou, A.; Tan, C.; Wu, Y.; Lee, H.-T.; Li, W.; et al. Forkhead box M1 is essential for nuclear localization of glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 in glioblastoma multiforme cells by promoting importin-7 expression. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 18662–18670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Jiang, H.-L.; Kim, S.-B.; Hong, S.-H.; Cho, M.-H. Knockdown of Importin 7 Inhibits Lung Tumorigenesis in K-rasLA1 Lung Cancer Mice. Anticancer Research 2017, 37, 2381–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, Y.; Teng, Y.; Yang, B. Increased Nuclear Transporter Importin 7 Contributes to the Tumor Growth and Correlates With CD8 T-Cell Infiltration in Cervical Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 732786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, D.; Zhan, Y.; Tan, S. IPO7 promotes pancreatic cancer progression by regulating ERBB pathway. Clinics 2022, 77, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golomb, L.; Bublik, D.R.; Wilder, S.; Nevo, R.; Kiss, V.; Grabusic, K.; Volarevic, S.; Oren, M. Importin 7 and exportin 1 link c-Myc and p53 to regulation of ribosomal biogenesis. Mol Cell 2012, 45, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xu, W.; Xuan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Q.; Lan, C. Pancreatic Cancer Progression Is Regulated by IPO7/p53/LncRNA MALAT1/MiR-129-5p Positive Feedback Loop. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 630262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloch, Z.W.; Asa, S.L.; Barletta, J.A.; Ghossein, R.A.; Juhlin, C.C.; Jung, C.K.; et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of thyroid neoplasms. Endocrine Pathol 2022, 33, 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Abdallah, A.; Jahanbani, I.; Mehdawi, H.; Ali, R.H.; Al-Brahim, N.; Mojiminiyi, O. The stress-activated protein kinase pathway and the expression of stanniocalcin-1 are regulated by miR-146b-5p in papillary thyroid carcinogenesis. Cancer Biol Ther 2020, 21, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using realtime quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzella, L.; Stella, S.; Pennisi, M.S.; Tirrò, E.; Massimino, M.; Romano, C.; Puma, A.; Tavarelli, M.; Vigneri, P. New Insights in Thyroid Cancer and p53 Family Proteins. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaguarnera, R.; Vella, V.; Vigneri, R.; Frasca, F. p53 family proteins in thyroid cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2007, 14, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, R.; Kheirollahi, A.; Davoodi, J. Apaf-1: Regulation and function in cell death. Biochimie 2017, 135, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uxa, S.; Castillo-Binder, P.; Kohler, R.; Stangner, K.; Müller, G.A.; Engeland, K. Ki-67 gene expression. Cell Death Differ 2021, 28, 3357–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma, W.; Zhao, P.; Zang, L.; Zhang, K.; Liao, H.; Hu, Z. Tumor suppressive function of HUWE1 in thyroid cancer. J. Biosci. 2016, 41, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaguarnera, R.; Vella, V.; Pandini, G.; et al. TAp73 alpha increases p53 tumor suppressor activity in thyroid cancer cells via the inhibition of Mdm2-mediated degradation. Mol Cancer Res 2008, 6, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Pochampally, R.; Chen, L.; Traidej, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J. Nuclear exclusion of p53 in a subset of tumors requires MDM2 function. Oncogene 2000, 19, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.H.; Clarke, M.F. Regulation of p53 localization. Eur J Biochem 2001, 268, 2779–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conforti, F.; Wang, Y.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Alberobello, A.T.; Zhang, Y.W.; Giaccone, G. Molecular Pathways: Anticancer Activity by Inhibition of Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling. Clin Cancer Res 2015, 21, 4508–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerfaoui, M.; Dokunmu, T.M.; Toraih, E.A.; Rezk, B.M.; Abd Elmageed, Z.Y.; Kandil, E. New Insights into the Link between Melanoma and Thyroid Cancer: Role of Nucleocytoplasmic Trafficking. Cells 2021, 10, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerasimov, G.; Bronstein, M.; Troshina, K.; Alexandrova, G.; Dedov, I.; Jennings, T.; Kallakury, B.V.; Izquierdo, R.; Boguniewicz, A.; Figge, H.; et al. Nuclear p53 immunoreactivity in papillary thyroid cancers is associated with two established indicators of poor prognosis. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 1995, 62, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penzo, M.; Montanaro, L.; Treré, D.; Derenzini, M. The Ribosome Biogenesis-Cancer Connection. Cells 2019, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Las Heras-Rubio, A.; Perucho, L.; Paciucci, R.; et al. Ribosomal proteins as novel players in tumorigenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2014, 33, 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, H. Signaling to p53: ribosomal proteins find their way. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, M.; Wei, H.; et al. Targeting p53 pathways: mechanisms, structures, and advances in therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.J. p53: 800 million years of evolution and 40 years of discovery. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastenhuber, E.R.; Lowe, S.W. Putting p53 in context. Cell 2017, 170, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäkel, S.; Görlich, D. Importin beta transportin, RanBP5 and RanBP7 mediate nuclear import of ribosomal proteins in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 4491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, K.P.; Itahana, K.; Jin, A.; Zhang, Y. Essential role of ribosomal protein L11 in mediating growth inhibition-induced p53 activation. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 2402–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohrum, M.A.; Ludwig, R.L.; Kubbutat, M.H.; Hanlon, M.; Vousden, K.H. Regulation of HDM2 activity by the ribosomal protein L11. Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursac, S.; Brdovcak, M.C.; Pfannkuchen, M.; Orsolic, I.; Golomb, L.; Zhu, Y.; Katz, C.; Daftuar, L.; Grabusic, K.; Vukelic, I.; et al. Mutual protection of ribosomal proteins L5 and L11 from degradation is essential for p53 activation upon ribosomal biogenesis stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 20467–20472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Uechi, T.; Kenmochi, N. Guarding the ‘translation apparatus’: defective ribosome biogenesis and the p53 signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2011, 2, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Yang, P.; Zhang, S. Cell fate regulation governed by p53: Friends or reversible foes in cancer therapy. Cancer Commun 2024, 3, 297–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, G.; Brighenti, E.; Vici, M.; Mazzini, G.; Treré, D.; Montanaro, L.; Derenzini, M. Selective inhibition of rRNAtranscription downregulates E2F-1: Anew p53-independent mechanism linking cell growth to cell proliferation. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 3017–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.-S.; Arnold, H.; Sun, X.-X.; Sears, R.; Lu, H. Inhibition of c-Myc activity by ribosomal protein L11. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 3332–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.J.; Synnott, N.C.; O’Grady, S.; Crown, J. Targeting p53 for the treatment of cancer. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2022, 79, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachmias, B.; Schimmer, A.D. Targeting nuclear import and export in hematological malignancies. Leukemia 2020, 34, 2875–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Mean expression value ΔCt (SD) |

NIFTP vs. FND | PTC vs. FND | |||||

| FND (n = 10) | NIFTP (n = 11) | PTC (n = 30) | Fold Change | p-value * | Fold Change | p-value * | |

| IPO7 | 2.35 (1.48) | -5.83 (3.25) | -9.82 (3.86) | 290.02 | <0.0001 | 4608.24 | <0.0001 |

| miR-7-5p | -1.05 (1.15) | 8.25 (5.07) | 9.57 (4.17) | -630.35 | 0.0003 | -1573.76 | <0.0001 |

| miR-7 level a | Signaling pathways b | |||||

| p53 | pRb/E2F | MYC/MAX | NFκB | MAPK/JNK | ||

| Sample 1 | -22.85 | -6.59 | -2.67 | -4.51 | -1.88 | -11.38 |

| Sample 2 | -15.37 | -3.70 | -3.64 | -3.76 | -1.46 | -58.01 |

| Sample 3 | -31.71 | 1.47 | -1.96 | -1.90 | -1.14 | -152.93 |

| Sample 4 | -2.38 | -4.63 | -5.87 | -7.41 | -2.45 | -15.54 |

| Sample 5 | -62.77 | -3.14 | -1.97 | -4.26 | -1.23 | -14.69 |

| Sample 6 | -13.97 | -2.26 | 1.99 | 1.35 | 4.09 | -1.28 |

| Sample 7 | -43.74 | -1.78 | -2.39 | -2.08 | 1.29 | -5.97 |

| Sample 8 | -17.72 | -2.45 | -1.93 | -1.71 | 1.63 | -3.29 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.016 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

|

Sample (Diagnosis) |

Expression level a | Signaling pathway activity b | |||||

| p53 | pRb/E2F | Myc/Max | NFκB | MAPK/JNK | |||

| miR-7-5p | IPO7 | p53 | E2F/DP1 | Myc/Max | NFκB | AP-1 | |

| 1 (PTC) | 22.50 | -92.72 | 8.23 | 4.86 | 6.01 | 1.43 | 1.62 |

| 2 (PTC) | 43.47 | -19.41 | 5.29 | -1.22 | 1.71 | 1.87 | -1.42 |

| 3 (PTC) | 48.23 | -7.45 | 2.72 | 1.32 | 4.34 | 1.73 | 1.28 |

| 4 (PTC) | 201.11 | -16.87 | 1.07 | 1.24 | 1.14 | 1.64 | 1.70 |

| 5 (PTC) | 36.05 | -12.27 | 2.60 | 2.86 | 1.84 | -1.36 | -1.86 |

| P Value | <0.002 | 0.04 | 0.067 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.38 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).