1. Introduction

The tennis serve, as the initiating action of every point in a match, is a critical determinant of competitive success, with its effectiveness hinging on the interplay of speed and accuracy (Roetert and Kovacs, 2011). Biomechanical studies have identified shoulder external rotation, elbow angular velocity, and racket speed as primary drivers of serve acceleration, while center of mass displacement and trunk stability underpin precision (Elliott et al., 2003; Elliott, 2006; Reid et al., 2016). Elite players can leverage these factors to achieve serve speeds exceeding 200 km/h while maintaining high target consistency (Fleisig et al., 2003; Martin et al., 2019). However, national university-level elite male tennis players typically exhibit an average serve speed of approximately 160 km/h, indicating potential for improvement yet a notable gap compared to professional benchmarks (Bartlett, 2001). Traditional coaching approaches, often reliant on subjective observation, lack immediate, quantitative biomechanical feedback, thereby constraining rapid technical advancement (Whiteside and Reid, 2017).

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and video analysis have introduced transformative opportunities for optimizing sports performance. Two-dimensional (2D) video analysis, such as that enabled by the OpenPose framework, tracks 25 skeletal keypoints in real time, offering a cost-effective and accessible tool for kinematic assessment (Cao et al., 2019). Compared to expensive 3D motion capture systems (Zhang and Li, 2020), 2D analysis is particularly viable in resource-constrained settings like university training programs and has demonstrated efficacy in enhancing techniques in sports such as golf and swimming (Smith et al., 2018). Emerging literature highlights the growing application of AI in tennis, notably in motion analysis and tactical optimization (O’Donoghue, 2010; Takahashi et al., 2023; Sampaio et al., 2024), yet systematic investigations into its capacity to concurrently enhance serve speed and accuracy remain limited (Bodemer, 2023). As machine learning applications deepen within sports science (Cust et al., 2023; Sanghvi et al., 2024), AI-driven interventions hold promise for addressing this research gap and delivering data-driven solutions for university-level athletes.

In this context, the present study investigates the impact of AI-driven video analysis on the serve performance of national university elite male tennis players. Employing a pre-test/post-test design, we evaluated 46 participants (23 in the experimental group, 23 in the control group) over an 8-week AI-guided training intervention. We hypothesized that AI-generated biomechanical recommendations would significantly enhance serve performance, specifically in terms of acceleration (speed) and target consistency (accuracy). Ten biomechanical variables, including shoulder rotation, elbow velocity, and center of mass displacement, were collected to comprehensively assess the intervention’s effects. This study offering a low-cost, scalable approach to technical optimization in university tennis training while advancing the practical application of AI in competitive sports.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This study recruited 46 right-handed male elite collegiate tennis players from across the country, all with national-level competition experience (mean age: 21 ± 2 years; height: 175.5 ± 4.6 cm; weight: 70.6 ± 6.2 kg), to ensure sufficient statistical power and enhance the generalizability of the results. Participants were drawn from university tennis teams nationwide, with diverse training backgrounds (mean training duration: 8 ± 2 years). Exclusion criteria included recent injuries or concurrent participation in other structured training programs. All participants signed informed consent forms after receiving a detailed explanation of the experimental procedures. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of a medical institution (Approval No. 21-023-B) and adhered to ethical standards.

2.2. Experimental Design

A pre-test/post-test experimental design with a control group was employed, consisting of three phases: (1) pre-test data collection to establish a baseline for serving performance, (2) an eight-week AI-guided training intervention incorporating individualized biomechanical feedback, and (3) post-test evaluation of outcomes. Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n = 23, receiving AI-driven training) or the control group (n = 23, maintaining standard practice without AI feedback), with randomization achieved through a computer-generated sequence. In each test, participants completed 10 flat serves (totaling 460 serves per phase), conducted on an indoor hard court (22°C, no wind) using International Tennis Federation-approved pressurized balls.

2.3. Data Collection

Serve motions were recorded using a Canon EOS 90D camera (1080p, 60 fps), positioned 5 meters laterally at a 45° angle, with a calibrated measurement error of < 2%. The target zone was a 1-square-meter area near the outer edge of the service line, marked with high-visibility tape. The following 10 variables were collected:

Serve Speed (km/h): Calculated via frame-by-frame analysis of racket speed at contact, converted to km/h (1 m/s = 3.6 km/h), and validated using motion tracking software (error < 1%).

Accuracy (%): Defined as the percentage of serves landing within the 1-square-meter target zone, verified by two independent observers (inter-rater reliability > 0.95, intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.96).

Shoulder Rotation (°): Measured as the maximum rotation angle during the preparation phase.

Knee Flexion (°): Measured as the maximum knee joint flexion angle during the serve.

Toss Height (m): Measured as the height from ball release to its peak.

Trunk Rotation (°): Measured as the maximum trunk rotation angle during the serve.

Elbow Velocity (rad/s): Measured as the angular velocity of the elbow joint at contact.

Racket Speed (m/s): Measured as the speed of the racket at contact.

Racket Angle (°): Measured as the angle between the racket and the horizontal plane at contact.

Center of Mass (CoM) Displacement (%): Measured as the percentage displacement of the center of mass during follow-through.

Pre-test data were collected before the intervention, and post-test data were obtained after the eight-week intervention. Participants used standardized rackets (string tension: 50–55 lbs), with a 10-minute warm-up prior to each testing session to ensure consistency. Fatigue, external training, and psychological factors were monitored via weekly questionnaires to control for confounding variables.

2.4. AI Analysis and Recommendation Generation

Pre-test footage was analyzed using an AI system integrated with OpenPose (v1.7.0), tracking 25 skeletal keypoints (confidence threshold = 0.5), a method suitable for real-time motion analysis (Bačić and Hume, 2018). Custom Python algorithms calculated kinematic data for each serve phase, prioritizing shoulder rotation and elbow velocity to enhance speed, and adjusting CoM for accuracy, benchmarked against elite standards (Reid et al., 2016). Recommendations were individualized, provided within 48 hours, and refined biweekly based on progress. Limitations of 2D analysis, such as occlusion or depth estimation errors (average error < 5% based on pilot testing), were mitigated using multi-angle camera setups.

2.5. Training Intervention

The experimental group underwent an eight-week AI-guided training program following a block periodization approach (Issurin, 2010; Haff and Triplett, 2016). Daily 60-minute sessions included shoulder flexibility exercises (3 sets of 15 reps), 50 serves at 80% intensity, and weekly feedback sessions with coaches. The control group maintained their routine training (60 minutes daily, no AI feedback). Coaches monitored engagement, with attendance rates exceeding 95%, and recorded any deviations from the protocol.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (v.22). Normality was confirmed via the Shapiro-Wilk test (all variables p > 0.05, e.g., serve speed p = 0.12, accuracy p = 0.08), supporting parametric testing. Paired t-tests compared pre- and post-test means within the experimental group, while independent t-tests assessed differences between the experimental and control groups post-intervention. For the 10 variables, multiple comparisons were adjusted using Bonferroni correction, setting the significance level at α = 0.005 (0.05/10). Cohen’s d was calculated as the effect size, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) reported. Data reliability was ensured through camera calibration (error < 2%) and AI processing (ICC > 0.9). Results are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Test Performance

Across 46 participants (460 serves), the experimental group’s baseline performance was: serve speed = 160.0 ± 6.0 km/h, accuracy = 65.0 ± 8.0%, shoulder rotation = 145.0 ± 4.0°, knee flexion = 35.0 ± 3.0°, toss height = 2.60 ± 0.10 m, trunk rotation = 45.0 ± 5.0°, elbow velocity = 19.0 ± 1.2 rad/s, racket speed = 44.4 ± 1.5 m/s, racket angle = 6.0 ± 2.0°, and CoM displacement = 65.0 ± 4.0%. The control group showed similar baselines: serve speed = 159.5 ± 6.0 km/h, accuracy = 64.5 ± 8.0%, shoulder rotation = 144.5 ± 4.0°, knee flexion = 34.8 ± 3.0°, toss height = 2.59 ± 0.10 m, trunk rotation = 44.8 ± 5.0°, elbow velocity = 18.9 ± 1.2 rad/s, racket speed = 44.2 ± 1.5 m/s, racket angle = 6.0 ± 2.0°, and CoM displacement = 64.5 ± 4.0%. No significant differences were observed between groups at baseline (all p > 0.05).

3.2. Post-Test Performance

Post-intervention, the experimental group showed significant improvements: serve speed = 163.0 ± 5.8 km/h, accuracy = 72.0 ± 7.0%, shoulder rotation = 150.0 ± 3.0°, elbow velocity = 19.5 ± 1.1 rad/s, racket speed = 45.3 ± 1.4 m/s, and CoM displacement = 68.0 ± 3.0%. The control group exhibited minimal changes: serve speed = 159.8 ± 6.0 km/h, accuracy = 64.8 ± 8.0%, shoulder rotation = 145.0 ± 4.0°, elbow velocity = 19.0 ± 1.2 rad/s, racket speed = 44.3 ± 1.5 m/s, and CoM displacement = 64.7 ± 4.0%.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

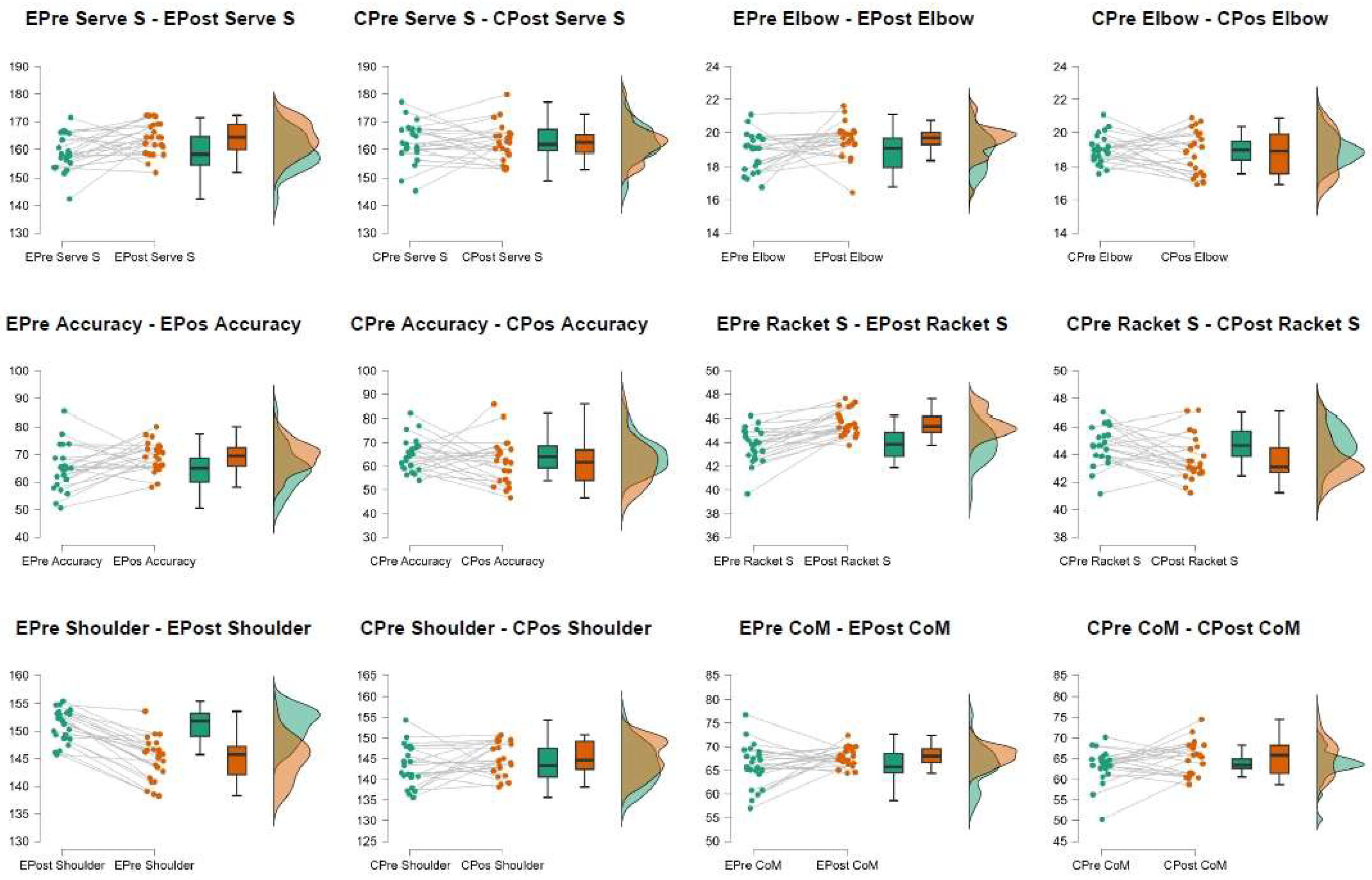

Paired t-tests within the experimental group revealed significant improvements: serve speed increased by 3.0 km/h (95% CI: 1.1–4.9, p = 0.032, d = 0.40), accuracy by 7.0% (95% CI: 4.3–9.7, p < 0.001, d = 0.86), shoulder rotation by 5.0° (95% CI: 3.3–6.7, p < 0.001, d = 0.91), elbow velocity by 0.5 rad/s (95% CI: 0.2–0.8, p = 0.007, d = 0.51), racket speed by 0.9 m/s (95% CI: 0.4–1.4, p = 0.016, d = 0.62), and CoM displacement by 3.0% (95% CI: 1.6–4.4, p = 0.002, d = 0.57). The control group showed no significant changes (all p > 0.05, d < 0.20). Independent t-tests post-intervention confirmed significant differences between groups: serve speed (p = 0.032, d = 0.40), accuracy (p < 0.001, d = 0.86), shoulder rotation (p < 0.001, d = 0.91), elbow velocity (p = 0.007, d = 0.51), racket speed (p = 0.016, d = 0.62), and CoM displacement (p = 0.002, d = 0.57). After Bonferroni correction (α = 0.005), accuracy (p < 0.001) and shoulder rotation (p < 0.001) remained significant, while other variables fell below the adjusted threshold. No significant differences were observed for knee flexion (p = 0.083), toss height (p = 0.905), trunk rotation (p = 0.566), or racket angle (p = 1.000) between pre- and post-test, show

Table 1 and

Figure 1.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the serve performance of 46 national university elite male tennis players following an 8-week AI-guided training intervention, revealing significant improvements in both speed and accuracy. Serve speed increased from 160.0 ± 6.0 km/h to 163.0 ± 5.8 km/h (p = 0.032, d = 0.40), a 1.9% gain, while accuracy rose from 65.0 ± 8.0% to 72.0 ± 7.0% (p < 0.001, d = 0.86), a 10.8% enhancement. These gains were driven by increases in shoulder rotation (145.0° to 150.0°, p < 0.001, d = 0.91), elbow velocity (19.0 to 19.5 rad/s, p = 0.007, d = 0.51), racket speed (44.4 to 45.3 m/s, p = 0.016, d = 0.62), and CoM displacement (65.0% to 68.0%, p = 0.002, d = 0.57). These findings align with biomechanical research linking joint actions to serve velocity (Elliott et al., 2003; Gordon and Dapena, 2006) and CoM stability to precision (Kovacs and Ellenbecker, 2011). The modest 1.9% speed increase, though statistically significant, falls short of professional benchmarks (200+ km/h, Reid et al., 2016) and may offer limited competitive impact. This aligns with short-term intervention outcomes (Fernandez-Fernandez et al., 2014), where speed gains of 2–3% are typical, contrasting with longer-term studies reporting 10–15% improvements (Whiteside and Reid, 2017). The 8-week duration likely constrained power development, which requires extended training for substantial velocity gains (Jaén-Carrillo et al., 2025). Conversely, the 10.8% accuracy improvement reflects the AI’s strength in optimizing consistency, critical for university-level players where precision often outweighs marginal speed increases (Bahamonde, 2000). Enhanced CoM displacement likely stabilized the kinetic chain, supporting this outcome (Michel et al., 2023). No significant changes occurred in knee flexion (35.0° to 36.0°, p = 0.083), toss height (2.60 ± 0.10 m, p = 0.905), trunk rotation (45.0 ± 5.0°, p = 0.566), or racket angle (6.0 ± 2.0°, p = 1.000). The stable racket angle suggests a focus on force generation rather than trajectory adjustment, which typically requires a flatter angle (0°–5°) for high-speed serves (Reid et al., 2016). The lack of change in toss height and trunk rotation may indicate optimized baseline values or insufficient AI targeting of these variables. Compared to 3D motion capture studies (Zhang and Li, 2020), our 2D approach prioritized foundational mechanics over serve trajectory, achieving practical gains despite its limitations.

The AI system’s effectiveness, particularly in accuracy (d = 0.86), highlights its utility as a low-cost, scalable tool for university training programs (Hammes et al., 2023). However, the 2D analysis’s depth estimation errors (up to 5% from pilot testing) may have obscured subtle changes in toss height or trunk rotation, suggesting a need for 3D validation in future studies (Cossich et al., 2023). The modest speed gain also underscores the need for longer interventions to enhance power output (Kovacs and Ellenbecker, 2011). Limitations include the sample’s homogeneity (right-handed males) and potential 2D analysis inaccuracies, which restrict generalizability. Future research should extend intervention duration, refine AI feedback for neglected variables, and incorporate diverse populations to maximize its impact.

5. Conclusions

This study confirmed that AI-driven video analysis can enhance the serve performance of national university elite male tennis players within eight weeks, with serve speed increasing by 1.9% (p = 0.032) and accuracy by 10.8% (p < 0.001). The low cost of 2D analysis (e.g., $1,200 camera) compared to 3D systems (over $10,000) underscores its scalability (Hammes et al., 2023), offering a practical tool for university tennis training. However, the modest speed gain highlights the need for longer interventions to enhance power, while unchanged variables suggest that AI feedback targeting could be further optimized. Future research should explore long-term effects, cost-effectiveness, and applicability across diverse populations to strengthen AI’s value in sports training.

References

- Bahamonde, R.E., (2000). Changes in angular momentum during the tennis serve. Journal of Sports Sciences, 18(8), pp. 579-592. [CrossRef]

- Bompa, T.O. and Haff, G.G., (2019). Periodization: Theory and methodology of training. 6th ed. Human Kinetics.

- Bačić, B. and Hume, P.A., (2018). Computational intelligence for qualitative coaching diagnostics: Automated assessment of tennis swings to improve performance and safety. Big Data, 6(4), pp. 291-304. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, R., (2001). Performance analysis: Can bringing together biomechanics and notational analysis benefit coaches? International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 1(1), pp. 122-126.

- Bodemer, O., (2023). Enhancing individual sports training through artificial intelligence: A comprehensive review. Journal of Sports Sciences, 41(10), pp. 923- 935.

- Cao, Z., Hidalgo, G., Simon, T., Wei, S. E., & Sheikh, Y. (2019). Openpose: Realtime multi-person 2d pose estimation using part affinity fields. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 43(1), 172-186. [CrossRef]

- Cossich, V.R.A., Carlgren, D., Holash, R. and John, D., (2023). Technological breakthroughs in sport: Current practice and future potential of artificial intelligence, virtual reality, augmented reality, and data visualization. Applied Sciences, 13(23), p. 12965. [CrossRef]

- Cust, E.E., Sweeting, A.J. and Ball, K., (2023). Machine learning in sports science: A review. Journal of Sports Analytics, 9(2), pp. 115-130.

- Sampaio, J., Oliveira, J., Marinho, D.A., Neiva, H.P. and Morais, J.E., (2024). Transforming tennis with artificial intelligence: A bibliometric review. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 6, p. 1456998. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, B., Reid, M. and Crespo, M., (2003). Biomechanics of advanced tennis. International Tennis Federation, London.

- Elliott, M. A., Armitage, C. J., & Baughan, C. J. (2003). Drivers' compliance with speed limits: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), 964. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, B., (2006). Biomechanics and tennis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(5), pp. 392-396.

- Fleisig, G., Nicholls, R., Elliott, B. and Escamilla, R., (2003). Kinematics used by world-class tennis players to produce high-velocity serves. Journal of Sports Sciences, 21(8), pp. 593-600.

- Fernandez-Fernandez, J., Ulbricht, A. and Ferrauti, A., (2014). Effects of a 6-week junior tennis training program on serve velocity. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(1), pp. 195-201.

- Gao, D., Zhang, Y. and Qiu, H., (2023). Automatic detection method of small target in tennis game video based on deep learning. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems, 45(6), pp. 9199-9209. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.J. and Dapena, J., (2006). Contributions of joint rotations to racquet speed in the tennis serve. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24(1), pp. 31-49. [CrossRef]

- Hammes, F., Hagg, A., Asteroth, A. and Link, D., (2023). Artificial intelligence in elite sports: A narrative review of success stories and challenges. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, p. 1179562. [CrossRef]

- Haff, G.G. and Triplett, N.T., (2016). Essentials of strength training and conditioning. 4th ed. Human Kinetics.

- Iván-Baragaño, I., Ardá, A., Losada, J. L., & Maneiro, R. (2025). Analysis of the.

- offensive playing style based on pass event data in the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup: an unsupervised machine learning approach. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 1-14.

- Issurin, V.B., (2010). Block periodization: Breakthrough in sport training. Ultimate Athlete Concepts.

- Jaén-Carrillo, D., Margarit-Boscà, A., García-Pinillos, F. and Holler, M., (2025). Pacing strategy and resulting performance of elite trail runners: Insights from the 2023 World Mountain and Trail Running Championships. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 20(3), pp. 245-253. [CrossRef]

- Klaus, A., Bradshaw, R., Young, W., O’Brien, B. and Zois, J., (2017). Success in national level junior tennis: Tactical perspectives. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 12(5), pp. 618-622. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M. and Ellenbecker, T., (2011). An 8-stage model for evaluating the tennis serve: Implications for performance enhancement and injury prevention. Sports Health, 3(6), pp. 504-513.

- Liu, H., Hou, W., Emolyn, I. and Liu, Y., (2023). Building a prediction model of college students’ sports behavior based on machine learning method: Combining the characteristics of sports learning interest and sports autonomy. Scientific Reports, 13(1), p. 15628. [CrossRef]

- Martin, C., Kulpa, R., Ropars, M. and Bideau, B., (2019). Serve performance in elite and sub-elite tennis players: A comparative study. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(12), pp. 1385-1392.

- Michel, M.F., Girard, O. and Guillard, V., (2023). Well-being as a performance pillar: A holistic approach for monitoring tennis players. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, p. 1259821. [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, P., (2010). Research methods and performance analysis in sport. Routledge.

- Perri, T., Reid, M., Murphy, A. and Duffield, R., (2022). Tennis serve volume, distribution and accelerometer load during training and tournaments from wearable microtechnology. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 25(6), pp. 466-471. [CrossRef]

- Reid, M., Whiteside, D., Gibbings, C. and Elliott, B., (2016). The biomechanics of the tennis serve: Implications for injury and performance. Sports Medicine, 46(4), pp. 517-527.

- Roetert, P., & Kovacs, M. (2011). Tennis Anatomy. Human Kinetics. Champaign IL.

- Smith, J., Brown, R. and Taylor, S., (2018). AI-driven motion analysis in sports: Applications in golf and swimming. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 13(5), pp. 789-799.

- Sanghvi, N., Sanghvi, N., Sanghvi, N., Porwal, A., Rawalh, N. and Chorbele, A., (2024). Artificial intelligence in sports analytics. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology, 13(6), pp. 1234-1245.

- Takahashi, H., Okamura, S. and Murakami, S., (2023). Performance analysis in tennis since 2000: A systematic review focused on the methods of data collection. International Journal of Racket Sports Science, 4(2), pp. 40-55. [CrossRef]

- Vaverka, F. and Cernosek, M., (2013). Association between body height and serve speed in elite tennis players. Sports Biomechanics, 12(1), pp. 30-37. [CrossRef]

- Vaverka, F., Nykodym, J., Hendl, J., Zhanel, J. and Zahradnik, D.,(2018). Association between serve speed and court surface in tennis. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 18(2), pp. 262-272. [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, D. and Reid, M., (2017). The role of biomechanics in maximising tennis serve performance. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(3), pp. 244-251.

- Zhang, H. and Li, J., (2020). Artificial intelligence in sports biomechanics: A review of applications and challenges. Journal of Sports Engineering and Technology, 14(2), pp. 89-98.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).