Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Porous Border of Adulthood

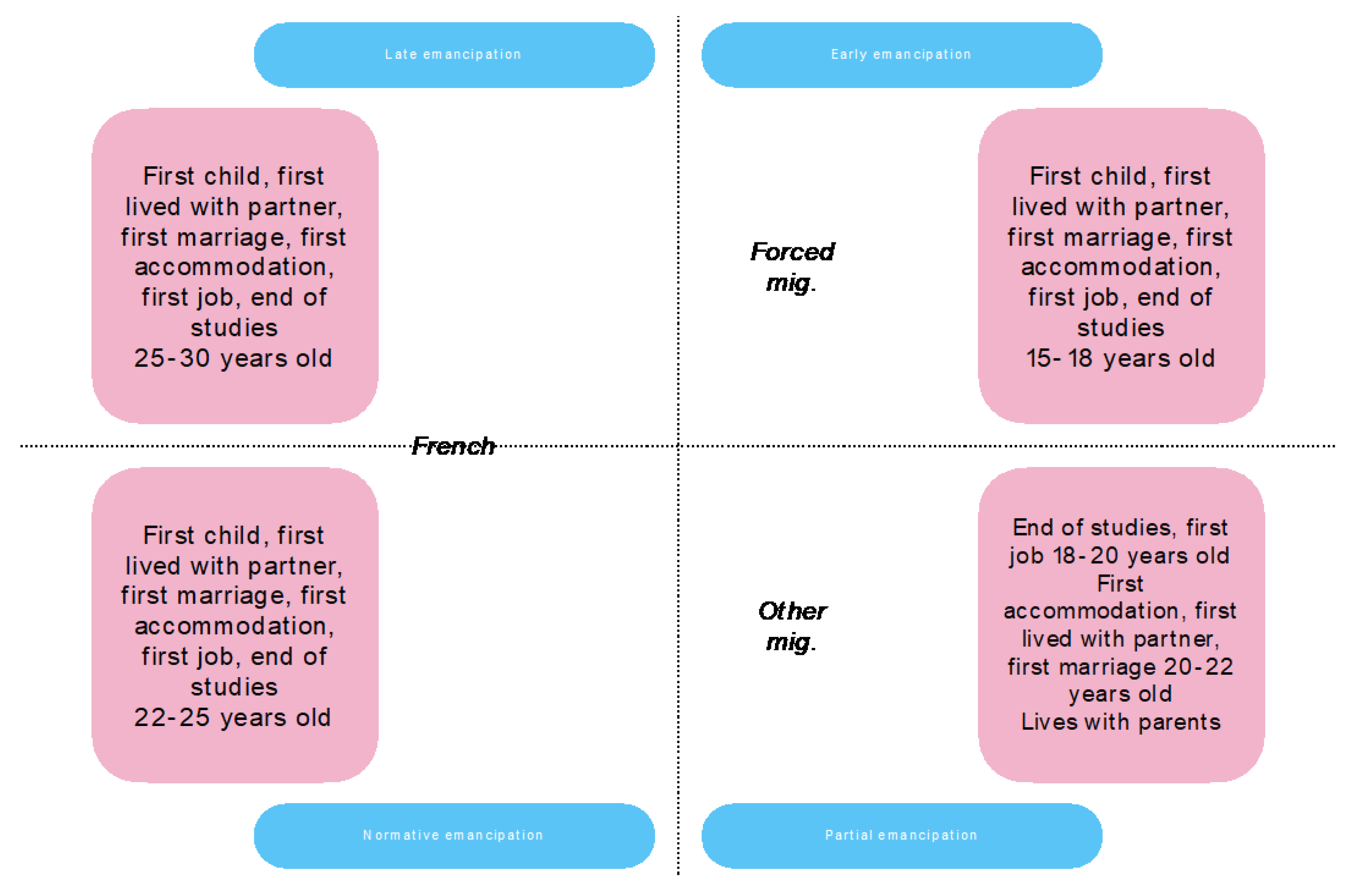

3.1.1. Different Profiles of Youth

3.1.2. A Backward Crossing of the Normative Border of Adulthood

I finished High School, I have all the diplomas. I started two years of University, but I stopped because I had my wife and my son. I chose to work because we didn’t have money. Here, I want to get the papers because… the years go on, I’ve been here for five years and I lost five years here in France – Male, 28 years old

I left my village to go to Kinshasa. […] I stayed there a while. I wanted to leave the village to make my life. I worked in a restaurant, I did hair for women. Then, there was a problem so I left. […] I don’t work here in France, I’ve never worked here in France. […] Life has no balance, we’re just here, we stay here like people who know nothing – Female, 23 years old

Over there in Tchad, I lived with my family. When I arrived here, I know nobody. I have to make my choices on my own. – Male, 27 years old

People around me see me like a child, because I don’t have the language. They don’t look at my body, at what’s inside my head, they just look at my… speaking. And so it’s the child who speaks, because he doesn’t know how to speak French. You’re not an adult, an old person, because here, every time, you’re helped. – Male, 24 years old

3.1.3. An Accelerated Transition into Adulthood

When I left Guinea, I was a child. I didn’t know how long it would take to arrive to France. And I felt like an adult when I arrived, because I know nobody here. I don’t have my parents here. So you have to manage. – Male, 26 years old

When you leave your mom and dad, we can neglect some things. We think ‘mom is here, dad is here’. Then, bam, you end up in a place like in a dream. You fall asleep, you wake up, you’re in another world. And you’re told ‘here, it’s like that, you have to learn that and that’. […] And that made me feel really responsible of myself. If I trip, I don’t have my mom to call. I have to fight, myself and I. – Male, 24 years old

After High School, I went to do economics to work in a bank. But I didn’t have time… I didn’t finish university because I left everything. […] Now if I study, it’s for a job and I already chose. I’ll do electricity, or mechanic. [- It’s quite different from economics and banking!] It’s not banking but here, when I left my country, I had to change my project. Someone in banking in Afghanistan, it’s… it’s not difficult. But here, things need a lot of time to be learnt. And I have a problem with the language. […] I am sad because in Afghanistan, I didn’t choose any other career. Banking is the first thing I chose, but here I was changed, I am sad. – Male, 26 years old

I arrived… I wasn’t enrolled yet. I went to the orientation centre, I did the test and everything… So I did the test, and then they told me I should start school and they put me in the first year of vocational in electricity. I’d never done electricity. In Congo, I’ve never done that. – Male, 20 years old

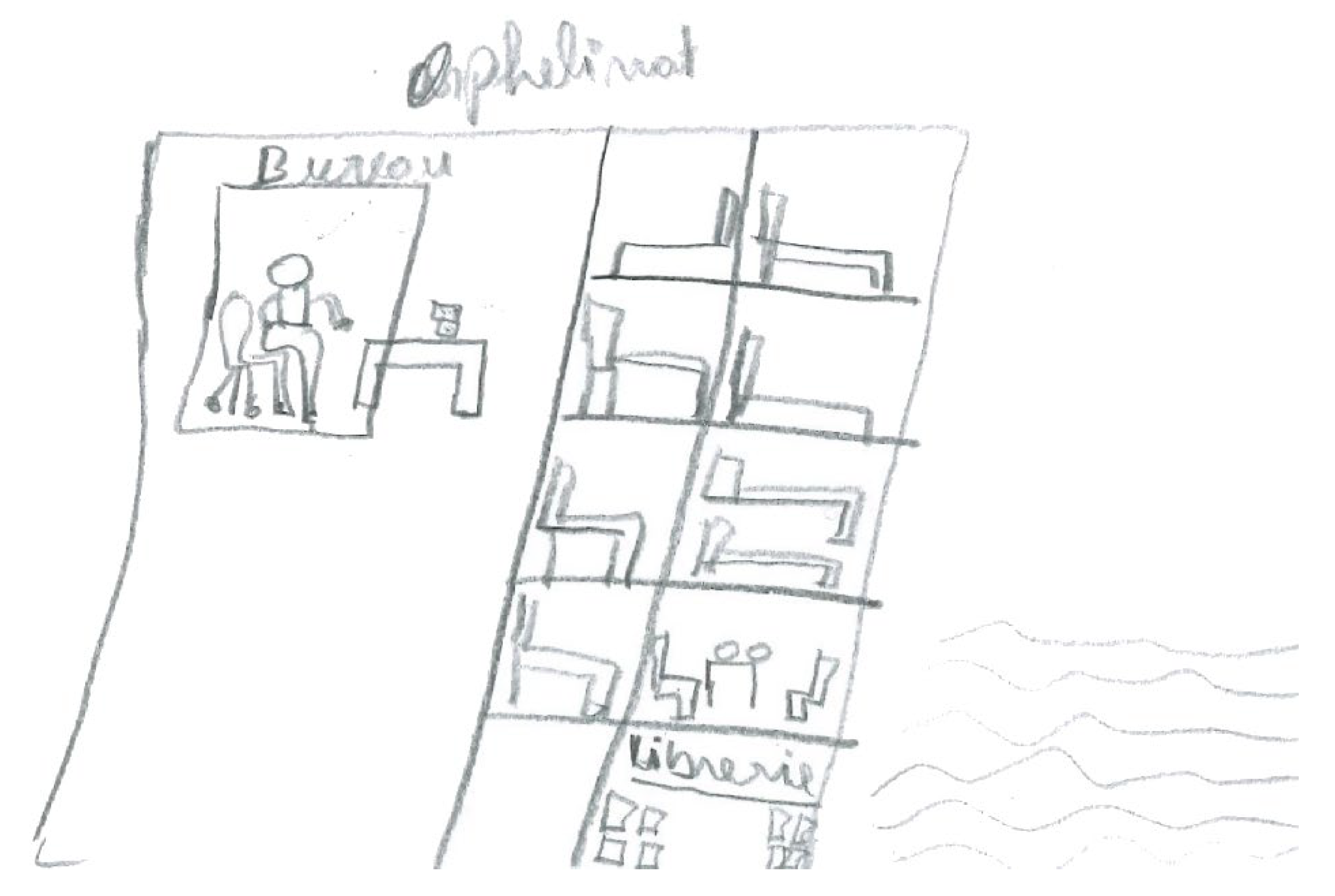

When they arrive at 16, we’re so happy because we have more time; when they’re 17, it’s a rush. We have to get them papers as fast as possible, and for that they have to check very precise boxes. They have to be integrated through school, work, social life, culture, as fast as possible, with concrete proofs. The major part of our support is to help this integration. – Unit manager, NGO managing an unaccompanied minors centre

Here, we’re convinced they should be able to change paths if they want, we try to defend that with the Department Council. The Department for them, they want the fastest way out. You have work placement, you have an income, you don’t take the risk to change. – Unit manager, NGO managing an unaccompanied minors centre

When I was in Afghanistan I was like a child. But now I went through all those problems, bad things; now I think I’m… an adult. […] Before, when I was with my family I was not an adult. Now I help my family. I went through a lot of problems, so I’m an adult because it’s not easy for someone to spend four months, everyday through problems, through forests, through mountains, that’s not something that children do, it’s not normal. I changed a lot. – Male, 26 years old

Being an adult, you know how to make decisions. The challenges I went through, they allow me to anticipate a lot of things, to make thought through decisions. I didn’t have this level of maturity before leaving Benin. The challenges I experienced, in Europe, they allowed me to become mature. – Male, 29 years old

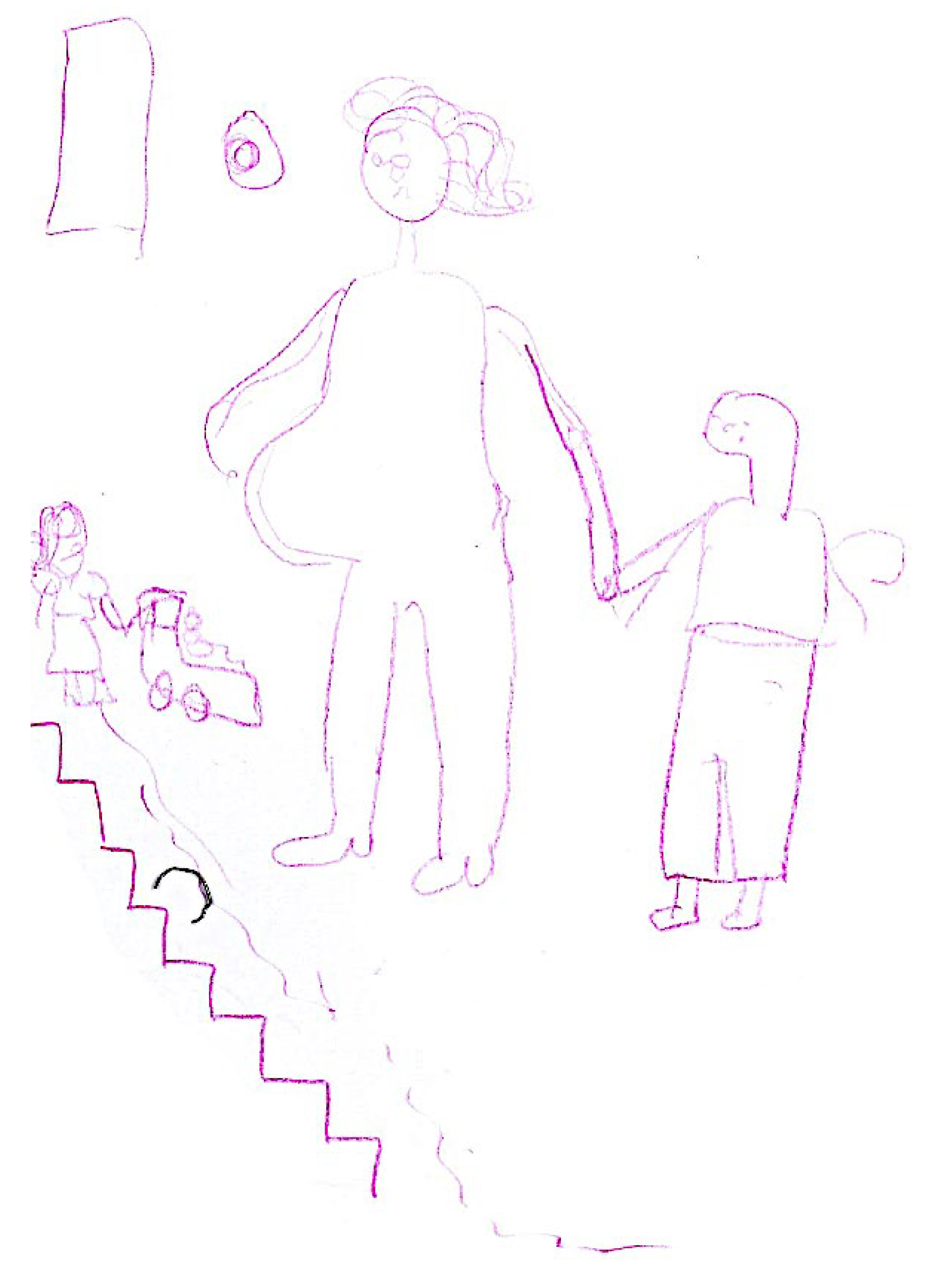

I feel like an adult since I’m in France, because as soon as I learnt French, I’m the one who brought my parents to appointments. I translate, I explain the e-mails, the mail. I make appointments, I… our roles are swapped. Now they speak French, A2 or B1. So with the doctors, with anything administrative, it’s complicated. I don’t know, it’s a very different relationship with your parents. – Female, 26 years old

3.2. Artistic Practices as Acts of Resistance to Reclaim the Adulthood Border

3.2.1. The Everyday Enactment of Agency

3.2.2. Exploration and Expression of the Self

Painting, it’s something you do in discussion, in interaction. It’s only by interacting with yourself that… it’s a communication. The canvas speaks, if you do not converse you… you have to be in symbiosis with it. The proof being sometimes when you paint, you want to bring the canvas somewhere but if it doesn’t want, you’re blocked and you feel a void of creativity, of passion. You need that, this contact. – Male, 29 years old

It's true that with art, I feel like we can express, we can say things. Art changed so much through time, the look on art changes every year. It’s something that changes and people change as well. Art changes me as well, I think we use art to change ourselves. It’s a relationship between art and myself, art and us. – Female, 19 years old

I really believe in the idea that an artist is someone who practices. If the artist doesn’t practice, he’s not an artist: you don’t write ideas on paper and tell people “I do that.” Rather, you have to go and do, try, fail, try, fail; for me, that’s the real artist. – Male, 24 years old

Sometimes I go back to what I drew before, and I see… my thought before and my thoughts now. How I had these problems before, how I tried to deal with them… I see that the problems that were very difficult then, now it’s the past. They’re over, they seem easy. I wrote about my problems, but then when I managed, I reread what I wrote and I saw that they were actually very easy. Now I went through all this to succeed after. It helps me a lot, it gives me courage to continue. – Female, 19 years old

3.2.3. Projection of the Self and Aspirations

It’s like… you’re taking a minute, you’re looking inside and you look back. It helps. – Male, 19 years old

4. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galland, O. Les jeunes; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2009.

- Biggart, A.; Walther, A. Coping with Yo-Yo Transitions. Young Adults’ Struggle for Support, between Family and State in Comparative Perspective. In A New Youth?; Leccardi, C., Ruspini, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, United Kingdom, 2006.

- Reifman, A.; Arnett, J.J.; Colwell, M.J. Emerging Adulthood: Theory, Assessment and Application. Journal of Youth Development 2007, 2, pp. 37-48. [CrossRef]

- De Valk, H. Pathways into Adulthood: a Comparative Study on Family Life Transitions among Migrant and Dutch Youth; Universiteit Utrecht: Utrecht, Netherlands, 2006.

- Lesnard, L.; Cousteaux, A.S.; Le Hay, V.; Chanvril, F. Trajectoires d’entrée dans l’âge adulte et États-providence. Informations sociales 2011, 3, pp. 16-24. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.S.; Nunes, C. Les trajectoires de passage à l’âge adulte en Europe. Politiques sociales et familiales 2010, 1, pp. 21-38. [CrossRef]

- Bidart, C. Les temps de la vie et les cheminements vers l’âge adulte. Lien social et Politiques 2006, 54, pp. 51-63. [CrossRef]

- Reifman, A.; Niehuis, S. Extending the Five Psychological Features of Emerging Adulthood into Established Adulthood. Journal of Adult Development 2023, 30, pp. 6-20. [CrossRef]

- Elder, G.H.; Johnson, M.K.; Crosnoe, R. The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory. In Handbook of the Life Course; Mortimer, J.T., Shanahan, M.J., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, United States, 2003, pp. 3-19.

- Mazade, O. La crise dans les parcours biographiques : un régime temporal spécifique ? Temporalités 2011, 13, pp. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, R.; Elsinga, M. ‘Buy Your Home and Feel in Control’ Does Home Ownership Achieve the Empowerment of Former Tenants of Social Housing? International Journal of Housing Policy 2010, 10, pp. 41-61. [CrossRef]

- Somerville, P. Empowerment through Residence. Housing Studies 1998, 13, pp. 233-257. [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.; Finegan, J.E.; Shamian, J.; Wilk, P. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Impact of Workplace Empowerment on Work Satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2004, 25, pp. 527-545. [CrossRef]

- Clot, Y.; Simonet, P. Pouvoirs d’agir et marges de manoeuvre. Le travail humain 2015, 78, pp. 31-52. [CrossRef]

- Deverchère, N. Innovations et engagement des travailleurs sociaux en faveur du développement du pouvoir d’agir. Vie sociale 2017, 3, pp. 91-105. [CrossRef]

- Frank, K. Agency. Anthropological Theory 2006, 6, pp. 281-302. [CrossRef]

- Hitlin, S.; Elder, G.H. Time, Self, and the Curiously Abstract Concept of Agency. Sociological Theory 2007, 25, pp. 170-191. [CrossRef]

- Coulon, A. Ethnométhodologie et education; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1993.

- Séguy-Duclot, A. Définir l’art; Belin: Paris, France, 2017.

- Rampley, M. De l’art considéré comme système social : observations sur la sociologie de Niklas Luhmann. Sociologie de l’art 2005, 7, pp. 157-185. [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, J.L. Des arts à la théorie de l’action : le travail sociologique de Pierre-Michel Menger. Annales. Histoires, sciences sociales 2016, 71, pp. 951-978.

- Chateau, D. Qu’est-ce que l’art ?; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2000.

- Wendling, T. Us et abus de la notion de fait social total : turbulences critiques. Revue du MAUSS 2011, 2, pp. 87-99. [CrossRef]

- Mauss, M. Essai sur le don : forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2012.

- Rancière, J. Et tant pis pour les gens fatigues : entretiens; Éditions Amsterdam: Paris, France, 2009.

- Langar, S. Les pratiques artistiques entre reconnaissances et emancipation : trajets d’artistes, de la rue à la scène internationale. Le Télémaque 2022, 2, pp. 109-124. [CrossRef]

- Calkin, S. Healthcare not Airfare! Art, Abortion and Political Agency in Ireland. Gender, Place & Culture 2019, 26, pp. 338-361. [CrossRef]

- Escafré-Dublet, A. Un allié précieux : l’art dans les mouvements immigrés à Paris et à Londres (1958-1978). Hommes & migrations 2019, 1325, pp. 47-55. [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, T.; Chevalier, T. Les méthodes mixtes pour la science politique : apports, limites et propositions de strategies de recherche. Revue française de science politique 2021, 71, pp. 365-389. [CrossRef]

- Beuchemin, C.; Ichou, M.; Simon, P. Trajectoires et Origines 2019-2020 (TeO2) : presentation d’une enquête sur la diversité des populations en France. Population 2023, 78, pp. 11-28. [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Valentin, D. Multiple Correspondence Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics; Salkind, N.J., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, United States, 2007, pp. 1-13.

- Larmarange, J. guide-R. Available online: https://larmarange.github.io/guide-R/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Roudet, B. Qu’est-ce que la jeunesse ? Après-demain 2012, 4, pp. 3-4. [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, L.; Liève, M. Les bénévoles, artisans institutionnalisés des politiques migratoires locales ? Lien social et Politiques 2019, 83, pp. 184-203. [CrossRef]

- Dunezat, X. Une figure racisée de la précarité : les sans-papiers. Raison présente 2011, 178, pp. 83-94. [CrossRef]

- Siméant, J. La cause des sans-papiers; Presses de Sciences Po: Paris, France, 1998.

- Le Bars, J. Le coût d’une existence sans droits. La trajectoire résidentielle d’une femme sans-papiers. Espaces et sociétés 2018, 1, pp. 19-33. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M. On the Streets of Paris: The Experience of Displaced Migrants and Refugees. Social Sciences 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- D’Halluin-Mabillot, E. Les épreuves de l’asile : associations et réfugiés face aux politiques du soupçon. Editions de l’EHESS: Paris, France, 2012.

- D’Halluin, E.; Hoyez, A.-C. L’initiative associative et les reconfigurations locales des dispositifs d’accès aux soins pour les migrants primo-arrivants. Humanitaire 2012, 33. https://journals.openedition.org/humanitaire/1407.

- McCarthy, B.; Williams, M.; Hagan, J. Homeless Youth and the Transition to Adulthood. In Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood; Furlong, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, United Kingdom, 2009.

- Lisiecka-Bednarczyk, A. Parenthood as a Disappearing Determinant of Adulthood. Quarterly Journal Fides et Ratio 2024, 59, pp. 54-63. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.; Shulman, S.; Bar-On, Z.; Tsur, A. The Role of Parentification and Family Climate Adaptation Among Immigrant Adolescents in Israel. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2006, 16, pp. 321-350. [CrossRef]

- Chase, N. Burdened Children: Theory, Research, and Treatment of Parentification; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, United States, 1999.

- Evans, K. Concepts of Bounded Agency in Education, Work, and the Personal Lives of Young Adults. International Journal of Psychology 2007, 42, pp. 85-93. [CrossRef]

- Bessin, M.; Bidart, C.; Grossetti, M. Introduction générale. In Bifurcations; Bessin, M., Bidart, C., Grossetti, M., Dirs.; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2009, pp. 7-19.

- Bidart, C. Bifurcations biographiques et ingrédients de l’action. In Bifurcations; Bessin, M., Bidart, C., Grossetti, M., Dirs.; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2009, pp. 224-238.

- Author, 2025.

- Mortimer, J.T.; Shanahan, M.J. Handbook of the Life Course; Springer: New York, United States, 2003.

- Scott, J.C. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance; Yale University Press: London, United Kingdom, 1985.

- Merle, I. Les subaltern studies : retour sur les principes fondateurs d’un projet historiographique de l’Inde coloniale. Genèses 2004, 56, pp. 131-147. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).