1. Introduction

Child development is a multifaceted process that involves a dynamic interplay between children and their environment. Among the many factors influencing this process, parents play a particularly profound role in shaping early learning [

1]. Researchers have long emphasized the importance of maternal care during infancy, as the quality of this care can either facilitate or hinder a child’s development [

2]. When infants enter the world, they are entirely dependent on their caregivers, in many cases their parents. As the child grows, parents play multiple roles including feeding, protecting, educating, disciplining, and bonding with their children [

3]. Through daily interactions, parents shape their children’s development both directly and indirectly. At the same time, parents also develop a sense of efficacy in their caregiving roles and establish expectations for their children [

4]. Therefore, a deeper examination of parents’ roles during infancy is crucial for understanding the complexities of early childhood development.

One significant and often overlooked component of parental influence is the role of parental perspectives—here identified as knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, theories, and expectations parents hold. These perspectives act as guiding principles, determining which activities are introduced, how feedback is given, and how much effort is invested in caregiving [

5]. These beliefs are active and evolving, responding to a parent’s own experiences, cultural background, and direct interactions with their child. Ultimately, parental perspectives create a framework that guides behavior and helps shape a child’s developmental journey across multiple domains, including motor skills.

This paper examines the pivotal role of parental perspectives in shaping infant motor development and seeks to integrate these perspectives into existing developmental frameworks. The analysis begins with a critical evaluation of theoretical models that provide insight into motor development. Building on this foundation, the paper reviews empirical studies of parental perspectives and behaviors in motor domains, identifying key gaps in the current understanding of how these beliefs and behaviors influence motor development. To address these gaps, a novel parent-centered ecological model is proposed, situating the parent-child dyad within a dynamic, interactive framework that accounts for cultural and environmental contexts. The paper concludes by discussing the implications of this model for research and practice, offering new directions for understanding and supporting early motor development.

1.1. Parental Perspectives in Academic Domains

Research has shown that parental perspectives significantly influence children’s developmental trajectories. This phenomenon has been primarily studied in the context of academic achievement. For example, children whose parents value math tend to perform better in that subject [

6,

7]. The mechanisms through which parental beliefs shape children’s math skills are important to understand. One proposed mechanism is that parents’ beliefs about the importance of math influence the types of activities they engage in with their children. Studies suggest that parents who place a high value on math are more likely to engage in math-related activities such as counting and sorting with their preschool and school-age children, thereby promoting their children’s math development [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Conversely, parental anxiety about their own math abilities is negatively associated with their children’s math performance [

13].

Similar patterns emerge in literacy development. Parents who hold strong beliefs about the importance of literacy are more likely to provide early literacy experiences [

14] and engage in positive interactions during joint book-reading activities [

15]. Through these home literacy practices, parents can foster both reading skills and motivation for reading in their children [

16]. Children whose parents believed reading is a source of entertainment show more interest in reading [

17]. More generally, parents’ academic expectations and school readiness-related beliefs contribute to the quantity and quality of parenting practices and in turn influence children’s school readiness. [

18]. Interestingly, even non-academic beliefs can influence early learning. For example, parents who emphasize the importance of play are more likely to support activities that foster creativity, problem-solving, and social-emotional skills [

19,

20]. Additionally, maternal self-efficacy beliefs have been associated with toddlers’ cognitive outcomes and affection towards their mothers [

21].

Collectively, these studies show that parental perspectives, whether specific to academic subjects or more general, can shape children’s development by influencing the behaviors and environments that support learning. While much of this research has focused on cognitive skills like math and reading, other domains of development—particularly motor development—have received far less attention.

1.2. Importance of Motor Development

Motor development is critical for children’s overall growth and lays the foundation for other domains such as language, social, and cognitive development [

22,

23]. The acquisition of motor skills opens new opportunities for children to explore their surroundings and engage in social interactions, which in turn influences their further development [

24,

25,

26,

27]. For instance, the development of reaching skills in early infancy allows children to grasp and manipulate objects, facilitating object exploration and problem-solving skills [

28]. Later, the emergence of locomotion skills, such as walking, enables infants to travel greater distances, experience new visual perspectives, interact with objects in various ways, and communicate more with caregivers [

29]. This interconnection between motor skills, environment, and other domains of development, is often explained through the concept of ‘developmental cascades,’ where advancements in one area can elicit positive responses from the environment that promote further development [

30,

31]. For example, as a child learns to crawl, their parents may praise and encourage them, which gradually facilitates language learning and helps them make meaningful connections with their surroundings. This, in turn, promotes overall development. Therefore, understanding motor development is essential, as it acts as building blocks for infant development.

While all infants achieve motor milestones as they grow, caregivers’ support is essential in this process. They contribute by providing physical space, engaging in play, and creating safe yet challenging environments for their children [

3]. Understanding how parental perspectives influence motor development can reveal insights into these dynamics. Unlike cognitive domains, motor development research has historically received less attention regarding parental perspectives, though it is equally vital [

23]. To contextualize motor development within a broader developmental framework, it is necessary to review theoretical perspectives that have guided research in this area. The following section will evaluate these theories to highlight their contributions and gaps, ultimately building the foundation for a renewed model.

2. Review of Theoretical Models

Theories of motor development provide frameworks for understanding how infants acquire motor skills and interact with their environments. Four prominent theories provide insights into motor development: the maturational theory, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, and dynamic systems theory. Each of these frameworks offers a unique lens.

Traditionally, motor development has been studied through a biological lens, as exemplified by the maturational perspectives put forward by Arnold Gesell and others in the early 1900s [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Maturational views have remained popular and found widespread adoption in therapeutic settings. A key principle of maturational theories of motor development is that motor development follows a biologically predetermined sequence of maturation and environmental factors are considered to play only a minor role. Accordingly, infants are expected to follow a strict developmental sequence based primarily on internal readiness, regardless of external stimuli [

36]. While this theory provides a foundational understanding of the biological underpinnings of motor development, its biologically determined view overlooks the significant role of experiences guided by parental engagement [

37]. For example, maturational theories fail to explain cross-cultural differences in infant motor skill attainment [

38].

A second theory that has found widespread adoption in the motor development literature is the dynamic systems theory. Dynamic systems views address the shortcomings of maturational perspectives by shifting the focus from fixed developmental sequences to the complex interplay of biological, environmental, and task-related factors that shape motor development [

39,

40,

41]. According to this theory, children’s behaviors are organized into dynamic patterns that exhibit both stability and flexibility. By emphasizing self-organization and the adaptive nature of motor skill acquisition, this theory provides a valuable point of view regarding the complexity of developmental changes. However, Dynamic Systems Theory has been criticized for its vague conceptualization of systems and its lack of specificity in identifying the causes of developmental change. This broad focus can make it difficult to predict or identify specific causal mechanisms [

42]. In this theory, systems are rather abstract entities that exert some influence on the child (aka the developing system). However, little attention is paid to these systems themselves. Specifically, while Dynamic Systems views would acknowledge that parents dynamically and reciprocally influence the child, the theory does not address the parent’s own behavior, goals, or beliefs – the Dynamic Systems Theory does not try to explain why the systems act the way they do.

Although not exclusively focused on motor development, other broader theories, such as the sociocultural theory and ecological systems theory, are also relevant. Lev Vygotsky's sociocultural theory offers profound insights into how social interactions and cultural norms shape individual development [

43]. A central concept of Vygotsky’s theory is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which highlights the difference between what a child can achieve independently and what he can achieve under the guidance of a more knowledgeable other, such as a caregiver, peer, or teacher. This process of scaffolding allows children to integrate new knowledge into their existing mental structures. Vygotsky’s framework emphasizes the importance of social and cultural contexts in learning. However, the theory may not be universally applicable, as different social groups may employ diverse learning methods, and each individual’s social experience is unique [

44].

While Vygotsky’s theory underlines social interactions and cultural contexts, Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory provides a more comprehensive view of bidirectional influences of environment on child development. The ecological systems theory [

45,

46,

47] complements other theories by situating the child within a complex system of relationships across multiple environmental levels. These interconnected systems range from the immediate family and close friends (microsystem) to broader cultural and societal influences (macrosystem). The exosystem, mesosystem, and chronosystem provide additional layers that contribute to a child’s upbringing. Despite its wide application, ecological systems theory has faced some criticism. For instance, some scholars argue that culture is deeply integrated into daily activities and should not be placed in a separate, distal system [

48].

Despite theoretical advancements, gaps remain in understanding the role of parental perspectives in infant motor skill development. The ecological systems theory and sociocultural theory may not fully apply to all social groups, as caregiving practices and interactions between parents and children can vary widely across cultures and communities. Therefore, the dynamics between parents and children can differ significantly, limiting the universality of these theories. Moreover, while these theories provide valuable insights, they are not specifically tailored to motor development during infancy. Factors such as school and peers may not be applicable.

In terms of theories that do focus on motor development, the maturational theory neglects the influence of environmental factors, suggesting that development is driven primarily by internal biological processes. On the other hand, the dynamic systems theory acknowledges the role of environmental variables, but its vague conceptualization of systems and subsystems makes it difficult to apply in specific contexts. Most importantly, all of the previous theories position the child at the center of the developmental model. While this perspective is critical, it failed to look into the essential role that parents play, especially during infancy.

3. Review of Empirical Studies

Empirical research provides valuable insights into the mechanisms through which parental perspectives and behaviors influence infant motor development. Prior research examining whether and how parental perspectives may influence child development can be categorized into explicit parental perspectives, implicit caregiving behaviors, and intervention-driven changes. Together, these studies illuminate the pathways by which parental perspectives shape behaviors, how these behaviors directly impact motor outcomes, and how contextual factors influence both perspectives and practices.

3.1. Explicit Assessments of Parental Perspectives on Motor Development

Research on explicit parental perspectives provides a window into how parents conceptualize motor development and the ways these conceptualizations shape their caregiving behaviors. Parental perspectives are influenced by cultural norms, socioeconomic conditions, and personal experiences, creating significant variability in practices that ultimately affect infant motor outcomes. However, research that focused on parental perspectives in the motor domain remains scarce. The few studies that have focused on the role of parental perspectives have been completed mainly outside of the United States.

In Brazil, research has shown that parental attitudes toward motor development can shape parenting practices and infant outcomes. For example, Gomes et al. [

49] asked parents about their beliefs and practices. It was observed that parents exhibit different approaches based on their beliefs. Parents who valued motor stimulation were more likely to actively encourage motor stimulation, offering toys, and spending time on the floor with their children to practice sitting and walking. Additionally, a more recent study by Graciosa et al. [

50] demonstrated that parents’ who held beliefs of motor development as a natural process tended to have children with later emerging independent walking skills. Together, these two studies show that parental beliefs or practices may accelerate or slow down motor skill development.

In England, a series of studies by Hopkins & Westra [

51,

52] compared Jamaican mothers living in England with their English counterparts. Results of these studies reveal surprising contrasting patterns. Jamaican mothers expected their children to achieve sitting and walking earlier than English mothers. These expectations were quite accurate as Jamaican infants did reach these milestones earlier. Interestingly, 3 English infants progressed from sitting to walking without having crawled, while 12 Jamaican infants achieved walking alone without crawling. These observations may relate to differences in beliefs. Jamaican mothers viewed sitting and walking as a significant step towards independence and success, whereas crawling was seen as primitive and hazardous. Yet, these views were not held by the British mothers, resulting in different motor development trajectories across the two groups.

In Isreal, parents tend to place their children in prone positions and encourage floor play. Similar to the Jamaican mothers, Israeli parents placed significant importance on motor development and believed in motor stimulation. Even so, they stimulate prone skills even when infants are asleep. On the other hand, Dutch families believed that resting is more important than stimulation and preferred to let the develop at their own pace. Interestingly, Israeli children have been observed to develop motor skills earlier compared to American children, whereas Dutch children lagged behind [

53,

54].

Research in several African communities provide additional context. In these communities, infants often achieve motor milestones significantly earlier than their American and European counterparts [

55]. This advancement is often attributed to broader societal factors. In these communities, motor skills are often encouraged from an early age, with parents employing hands-on methods to promote skills like sitting and standing [

56]. For example, Yoruba mothers reported that the age at which babies attain motor milestones depends on how they are reared. Some mothers even suggest that children would not achieve these milestones without active teaching. These beliefs are coupled with cultural traditions. Yoruba caregivers often prop infants into sitting positions and place them in cardboard boxes or basins, believing these practices help foster independent sitting [

57].

The reviewed studies highlight significant variability in parental beliefs and behaviors, not only across cultures but also within them, revealing the complexity of the relationship between caregiving practices and motor development. In Brazil, research demonstrates that even within the same cultural context, parental attitudes toward motor development can vary widely. Some parents actively promote motor stimulation, engaging in practices such as floor play and the use of toys to encourage sitting and walking [

49]. In contrast, others adopt a more hands-off approach, viewing motor development as a natural process that unfolds without the need for direct intervention [

50]. These differing perspectives align with distinct caregiving strategies and are potentially associated with variations in the timing of motor milestones, such as the emergence of independent walking. Cultural contrasts across countries further emphasize the influence of parental values on caregiving practices. Jamaican mothers prioritize sitting and walking, connecting these milestones with independence and maturity, while Israeli parents emphasize prone positioning to encourage early physical skills [

51,

52,

53]. In contrast, Dutch parents adopt a self-paced developmental philosophy, linked with slower attainment of motor milestones [

54]. These studies collectively reveal the nuanced relationships between parental perspectives, caregiving behaviors, and motor outcomes, demonstrating variability both within and across cultural contexts. They raise important questions about the factors that influence these relationships and challenge the assumption of uniformity in caregiving practices and beliefs, even within a shared cultural framework.

3.2. Implicit Assessments of Parental Perspectives on Motor Development

While explicit assessments provide insights into indirect influences of parental perspectives, implicit assessments reveal direct connections between caregiving practices and motor development. These studies often examine how parenting behaviors, shaped by cultural values and societal norms, impact infants’ motor trajectories. Although these practices may not always reflect consciously articulated beliefs, they provide critical information about the parent-child dyad.

Research in Kokwet highlights how societal norms shape proactive caregiving. Super [

58] observed that over 80% of mothers reported actively teaching their children skills such as sitting and standing, demonstrating a deeply embedded cultural emphasis on fostering motor development. Similarly, in Zambia, parents engage in culturally specific techniques to encourage motor skills, such as tossing infants to increase arousal and muscle tone or placing them in slings to promote postural stability [

59,

60]. These practices were associated with advanced skills in sitting and standing but delayed crawling compared to Euro-American infants, reflecting differing cultural values about which motor milestones are prioritized. In contrast, Euro-American parents view crawling as an essential milestone, linking it to early locomotor ability, autonomy, and environmental mastery [

61]. To promote these abilities, they encourage independent locomotor efforts and reinforce quadrupedal movements [

38].

The delayed development of certain skills due to caregiving practices is another theme in implicit assessments. For instance, in rural Chinese communities, parents often do not emphasize motor milestones and engage minimally in interactive play with their infants. Wang et al. [

62] observed that this lack of emphasis was associated with delayed motor skills and other developmental domains, suggesting that parental behaviors significantly influence developmental outcomes. A more striking example comes from Tajikistan, where the use of the “gahvora”—a traditional cradle that binds infants for prolonged periods—limits movement and leads to delayed milestones such as crawling and walking [

63,

64]. These findings illustrate how implicit caregiving practices, informed by cultural traditions, can both nurture and constrain motor development depending on the emphasis placed on movement and exploration.

Within-cultural variations in parenting behaviors provide additional insights. In the United States, the "Back to Sleep" campaign, which promoted supine sleeping to reduce sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), led many parents to restrict prone sleeping positions [

65]. Davis et al. [

66] found that this shift was associated with delayed motor milestones, such as rolling and crawling. However, infants who regularly participated in tummy time or were placed in prone positions during waking hours demonstrated significantly higher locomotion scores [

67]. These findings suggest that while parental practices may not always explicitly prioritize certain motor activities, these implicit decisions have measurable effects on infants’ motor development.

Cultural priorities regarding motor milestones also highlight the variability in implicit caregiving practices. For example, in Euro-American families, where crawling is viewed as a critical developmental step, parents may unconsciously encourage behaviors that facilitate independent mobility. Conversely, in communities where early sitting or standing is emphasized, practices like tossing or propping infants reflect an implicit belief in the importance of fostering postural control and balance.

Altogether, these examples demonstrate that caregiving practices are shaped by cultural values, societal norms, and individual parenting strategies. They show how parental behaviors influence motor trajectories by creating opportunities or imposing limitations. While these behaviors may not directly reflect parents’ conscious perspectives, they provide a valuable lens for understanding how implicit priorities and beliefs drive caregiving decisions and, consequently, infant development.

3.3. Intervention Research for Parents Pointing to Changes in Parental Behaviors

Intervention programs provide critical insights into how parental perspectives and behaviors can be influenced to support infant motor development. These programs target either explicit and implicit aspects of parenting by addressing parental beliefs, modifying caregiving practices through structured activities, or fostering new skills. By engaging parents as active participants, interventions highlight the mechanisms through which parent-focused approaches can foster both immediate and long-term developmental outcomes.

Programs designed to explicitly modify parental perspectives demonstrate how changes in beliefs can influence caregiving behaviors and child outcomes. The Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) exemplifies this approach. By educating parents about infant behavioral cues and caregiving techniques, NIDCAP aims to reduce parental stress and enhance parent-infant interactions. Participants reported improved confidence in interpreting their infant’s needs and greater adaptability in caregiving strategies, leading to better motor outcomes for their children [

68]. Another program by Moxley-Haegert and Serbin [

69] supports this notion. In this study, a home treatment program was implemented to help developmentally delayed children. Caregivers who received parent-education were more knowledgeable and had better understanding of their children’s development than the no-education control group. Their children also had better motor outcomes as well. Moreover, at the follow-up visit a year later, caregivers who received education participated more in treatment programs and were more motivated than the control group. Their children also showed continued advancement in motor skills. These changes seem to be long-lasting, demonstrating the benefit of support and education for parents.

Implicit influences on parental perspectives are observed in both clinical and non-clinical interventions that indirectly shape behaviors. Clinical programs targeting infants at risk for developmental delays demonstrate the importance of parental involvement in achieving positive outcomes. For instance, interventions emphasizing motor-enhancing exercises rely heavily on parents’ active participation, and studies have shown that greater parental involvement correlates with improved motor milestones [

70,

71]. These findings suggest that interventions not only improve infant outcomes but also enhance parents’ understanding of their role as facilitators of development. Importantly, parents involved in such programs often report lasting changes in their caregiving behaviors, even after the intervention concludes [

72].

Non-clinical interventions illustrate the transformative potential of parent-led practices integrated into daily routines. For example, Lobo and Galloway [

73] demonstrated that parents trained in enhanced handling and positioning techniques for three weeks observed significant improvements in their infants’ gross and fine motor skills. Similarly, “sticky mittens” interventions, where parents guide infants in enriched reaching sessions, resulted in increased manual exploration, better coordination, and stronger parent-infant engagement [

74,

75]. These interventions influence parental behaviors by embedding motor skill practices into naturalistic interactions, ensuring that changes are practical and sustainable.

The mechanisms driving changes in parental perspectives and behaviors are multifaceted. Education programs directly influence explicit beliefs by equipping parents with knowledge about developmental processes and caregiving techniques. For instance, by learning the importance of tummy time or handling exercises, parents may adopt more structured motor-stimulating behaviors. Behavior-focused interventions rely on experiential learning, where parents see tangible improvements in their child’s development, reinforcing the value of their caregiving practices. These experiences create positive feedback loops, where successful engagement strengthens parental confidence and commitment to motor-focused caregiving.

Whether these changes last depend on several factors, including the intensity and frequency of the intervention, the support available to parents post-intervention, and how well the practices align with parents’ cultural and ecological contexts. Studies like those by Lobo and Galloway [

73] demonstrate that when interventions are integrated into daily routines and supported by follow-up resources, parents are more likely to sustain changes over time.

Collectively, these examples illustrate that interventions targeting both parental perspectives and behaviors can influence caregiving practices and create lasting impacts on infant motor development. By providing parents with practical skills, reinforcing positive outcomes, and addressing cultural and contextual factors, these programs equip families with the tools necessary to sustain nurturing caregiving environments.

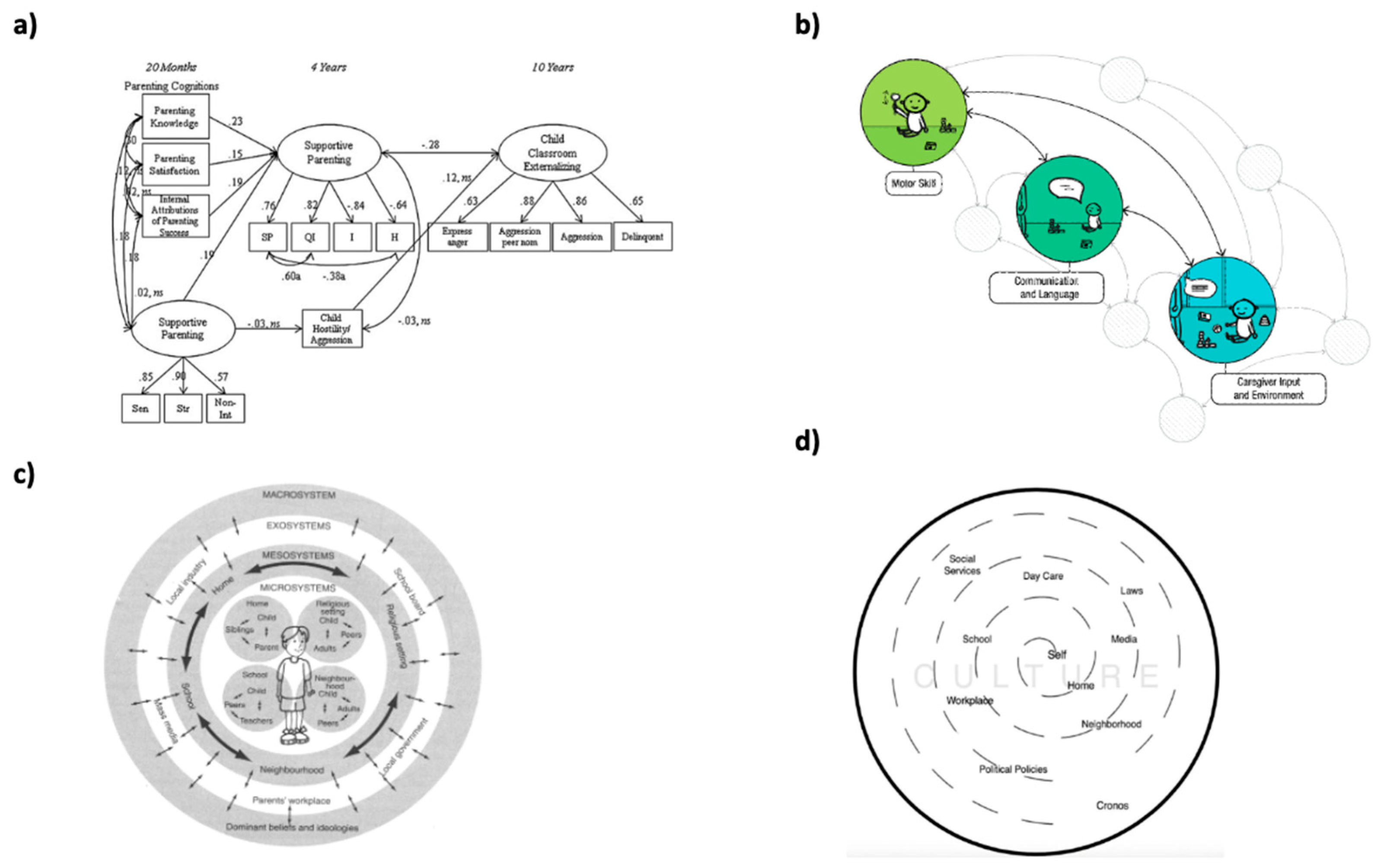

4. New Integrated model

While existing theories and empirical studies offer valuable insights into motor development, significant gaps remain in understanding how parental perspectives dynamically influence caregiving behaviors and motor outcomes within diverse ecological contexts. Existing theoretical models, such as Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory and dynamic systems theory, recognize the importance of environmental and interactive factors but often overlook the active role of parents, particularly how their beliefs and behaviors dynamically influence motor outcomes. These frameworks lack integration of parental perspectives as central agents of developmental change, especially during infancy.

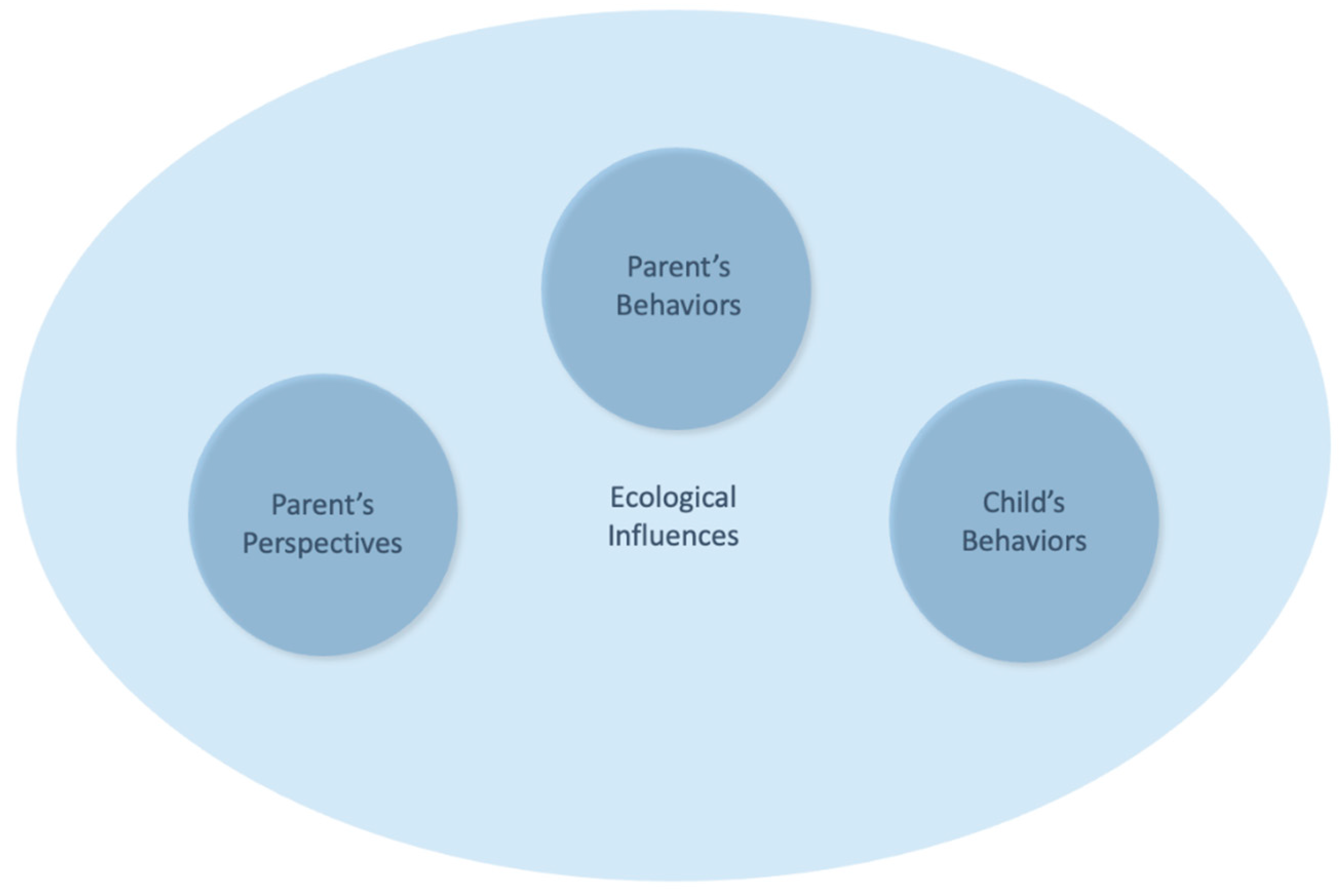

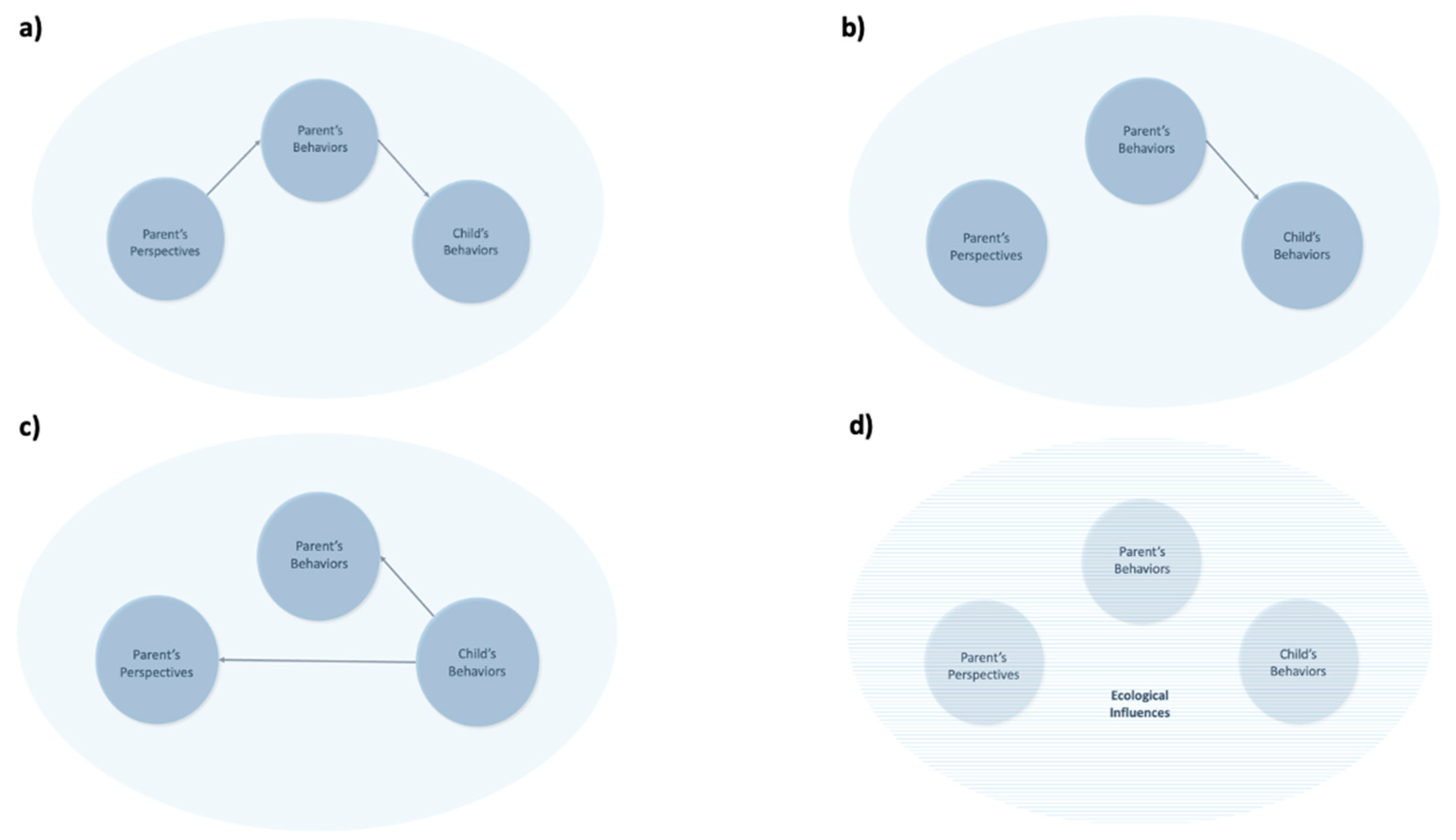

To address existing gaps, we propose a new integrated model that situates the parent-child dyad within an ecological framework, emphasizing the dynamic interplay between parental perspectives, parental behaviors, and infant motor development (see

Figure 1). By consolidating existing theories, the model is structured around three core components: parental perspectives, parental behaviors, and children's behaviors. These interactions are embedded within an ecological layer that represents the unique contexts of both parents and children. The model recognizes that parental perspectives and behaviors evolve through interactions with their children and their broader environment. It also draws attention to the importance of cultural and socioeconomic contexts in shaping these perspectives and practices, providing a comprehensive understanding of how parents influence their children’s development. By focusing on the reciprocal nature of parent-child dyads and the contextual factors that shape these interactions, this model offers new insights into the mechanisms through which parental perspectives affect motor outcomes.

4.1. Model Components

At the heart of this model are parental perspectives – a wide range of cognitive constructs that parents hold regarding their children, themselves, the course of development, and child-rearing practices. These perspectives encompass knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, theories, and expectations. Existing research has explored aspects of parental perspectives under the term "parental cognitions," which refers to parenting knowledge, beliefs, expectations, perceptions, and satisfaction [

5,

76]. Parents acquire information about child development through daily experiences, such as babysitting siblings; through communicating with others, such as friends and families; and through education, such as parenting classes. For example, when a father sees his daughter turning her head side to side, he may know that she is hungry because he learned this from a parenting book. Additionally, parents form beliefs, theories, and ethnotheories [

77] based on their own experiences, cultural backgrounds, and interactions with their children. For instance, a parent who experienced physical play during childhood may believe that physical play is essential for child development. Parents also develop expectations regarding their children’s developmental milestones. For example, a mother may expect her daughter to start walking around 12 months based on observations of other children. These perspectives guide parental behaviors, which, in turn, influence children’s behaviors (see

Figure 2a and

Figure 3a).

Parental behaviors refer to the actions, responses, and methods parents use in child-rearing. These behaviors are shaped by parents' knowledge, theories, attitudes, and beliefs [

78]. For example, when a father sees his hungry daughter turning her head, he draws from his knowledge and respond by feeding her. A mother who believes motor stimulation is beneficial might reinforce tummy time with her son. Parents' expectations also influence how they interact with their children. For example, a mother who expects her child to walk early may provide more opportunities to practice walking. It’s also important to note that parental perspectives don’t always align with actual practices. A father may believe screen time is harmful for motor development while allowing his child to watch TV due to exhaustion. Nevertheless, parental behaviors play a crucial role in shaping children’s motor development (see

Figure 3b).

Children's behaviors in this model refer to the observable motor actions that infants display through their interactions with caregivers and the environment. These behaviors include both immediate reactions to parental actions and the motor skills that develop over time. For instance, children whose parents encourage sitting may acquire sitting skills faster, and those whose parents restrict walking may develop walking skills slower. Due to the reciprocal nature of parent-child dynamics, children's behaviors can also influence their parents' behaviors and perspectives (see

Figure 2b and

Figure 3c). While traditional models have viewed the child as a passive recipient of parental guidance, this model aligns with the concept of bidirectional influences between parents and children, as described by Relation Developmental Systems-Based Models [

79]. Our model also draws from Piaget’s and Gibson’s notion of children as active learners. [

80] suggested that infants explore and experiment with motor actions to construct knowledge about their abilities and everything around them. Similarly, [

81] theory on perception emphasizes that children are attuned to environmental cues, learning from the opportunities their surroundings provide. Together, they indicate that children actively shape their own motor development through exploration, creating a feedback loop where their actions elicit meaningful responses from caregivers. This bidirectional process also reflects the concept of developmental cascades where a child's motor development sparks environmental responses, further shaping growth [

30]. For example, if an infant does well during tummy time, the parent may continue the activity, which may alter the parent's perception of his abilities.

Parents and children alone do not fully encapsulate the complexity of child development. Integrating an ecological layer is crucial to account for the additional factors that affect this process. Drawing from Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory [

45] and its revised version [

48], we propose that parental perspectives, parental behaviors, and children's behaviors are embedded within an ecological layer (see

Figure 2c,

Figure 2d, and

Figure 3d). This layer includes, but is not limited to, factors such as neighborhoods, extended families, community networks, social trends, cultural contexts, public policies, socioeconomic status, and life events. These factors are incorporated into a flexible and inclusive ecological layer, acknowledging that not all families engage with every system in the same way.

5. Discussions

The proposed integrated model for understanding infant motor development provides a comprehensive framework that addresses parental perspectives, parental behaviors, and child behaviors within an ecological context. By emphasizing the evolving, reciprocal interactions between these components, this model offers a holistic perspective on the factors that influence motor development during infancy.

5.1. Summary of Current Model

Central to this model are parental perspectives, which play a key role in shaping how parents interact with their children and the behaviors they adopt. These perspectives also determine the opportunities and support children receive for motor development. Importantly, parental perspectives are not fixed; they change as parents gain new experiences, insights, and as they respond to children’s behaviors. These shifting perspectives, in turn, guide the actions and practices.

Equally important are children's behaviors, which encompass the observable motor actions and reactions that emerge as they engage with their environment and caregivers. These behaviors are influenced by parental perspectives and actions but also affect how parents respond. This aligns with developmental theories that pointed out the active role children play in shaping their own development [

80,

81]. Rather than viewing parent-child interactions as a one-way process, this model highlights the cyclical nature of these exchanges, where children's actions continuously inform parental behaviors and beliefs [

79].

The current model is also unique as it places parents in the inner circle, examining the factors influencing their perspectives and behaviors. Such an approach not only highlights the critical role parents play during infancy but also provides a deeper understanding of why parents engage in specific parenting behaviors. This understanding can inform targeted interventions, enabling us to better help parents so that they, in turn, can better support their children.

The ecological layer integrates various contextual factors into a flexible framework, recognizing that each family operates with a unique set of circumstances. As societal conditions evolve, so too do the environments that influence motor development. By incorporating elements of prior theories, this model underlines the changing nature of children's developmental contexts, while accounting for the distinct challenges and opportunities that families encounter [

45,

48]. Ultimately, the interactions between parents, children, and the surrounding environment jointly craft parenting practices and developmental outcomes.

5.2. The Current Model in Action

The current model offers a renewed interpretation of motor development by addressing key limitations in traditional child-centered frameworks. While previous models focus primarily on the child’s experiences and outcomes—emphasizing motor opportunities provided to the child—the current model highlights the dynamic and reciprocal role of parental perspectives and behaviors in shaping motor development. By embedding these processes within broader ecological contexts, this model uniquely accounts for the evolving interplay between parents, children, and their environments.

Traditional frameworks often attribute motor development to the direct experiences children receive, neglecting the critical role of parental beliefs as a driver of those experiences. For example, studies by Gomes et al. [

49] and Graciosa et al. [

50] highlight variations in parental beliefs, caregiving practices, and motor outcomes within Brazil. A child-centered model might attribute motor outcomes to the child’s exposure to motor opportunities. In contrast, the current model identifies parental perspectives as the initiating factor, showing how beliefs guide behaviors, which then indirectly influence child outcomes. This additional layer of explanation distinguishes the current model by placing parents at the center of the developmental process.

Cross-cultural examples further clarify this distinction. Jamaican mothers explicitly prioritize sitting and walking as indicators of independence and success, resulting in proactive caregiving strategies such as encouraging weight-bearing activities [

52]. Similarly, Dutch parents’ belief in a self-paced, natural progression of development results in fewer structured motor opportunities [

54]. Israeli parents’ explicit emphasis on prone positioning is tied with active stimulations [

53]. Previous models would point out the differences in parenting approaches but overlook the mechanisms behind them. The current model recognizes parental perspectives as the foundation of caregiving behaviors, providing a pathway to understand cross-cultural and within-culture variability in motor development.

Traditional child-focused models interpret caregiving behaviors as simply providing or restricting opportunities for motor development. The current model, however, situates these behaviors within cultural and ecological contexts, recognizing that parenting practices reflect deeper parental values and societal norms. For instance, Zambian parents’ use of tossing and slings promotes sitting and standing while deprioritizing crawling [

59]. Further, in rural Tajikistan, the gahvora cradle restricts infants’ movement, delaying crawling and walking milestones [

63,

64].

While traditional models attribute these advancements and delays solely to reduced or increased motor experiences, the current model explains these practices as arising from ecological constraints and parental beliefs about safety, independence, and convenience. This deeper contextualization sets the current model apart by providing a more holistic explanation for motor development variability.

Intervention studies illustrate the significant differences between the current model and traditional frameworks. In the “sticky mittens” intervention [

74], child-centered interpretations focus on the enriched motor experience for infants, emphasizing improvements in manual exploration. The current model, however, highlights the role of parents. By actively guiding their infants during the intervention, parents not only provide motor opportunities but also gain new insights and confidence in their ability to facilitate development. These shifts in parental perspectives can influence future behaviors, creating lasting changes beyond the immediate intervention. Similarly, parent education programs like NIDCAP [

68] show that interventions do not merely improve motor outcomes for infants but also enhance parents’ understanding and caregiving strategies. While traditional frameworks focus on the motor gains for children, the current model highlights that these interventions reshape parental beliefs, fostering environments that sustain developmental progress.

In summary, the current model stands apart from previous child-centered frameworks by foregrounding the role of parents as active agents in motor development. It uniquely integrates parental perspectives, caregiving behaviors, and the child within an ecological context, providing a more comprehensive explanation for motor development. By emphasizing the pathways through which parental beliefs guide behaviors, and how these behaviors shape child outcomes, the model offers a deeper understanding of the variability observed across cultures and contexts. Unlike traditional models that view motor development as the product of opportunities provided to the child, the current model highlights the dynamic interplay between parents, children, and their environments, taking a closer look at how ecological factors impact the parent-child dyad.

5.3. Implications for Research and Practice

The integrated model has significant implications for both research and practice. Researchers can use this model to design studies that capture the complexity of environmental influences on motor development, employing methodologies that account for the interactions between different contextual factors. Observing and documenting changes in motor behaviors within various contexts will provide valuable insights into the developmental process and offer a clearer understanding of motor skill acquisition.

For practitioners, this model can guide the development of interventions that address multiple layers of influence, from direct parent-child interactions to broader community and societal supports. By focusing on enhancing parental perspectives and behaviors, interventions can create supportive environments that foster motor development. Understanding the unique circumstances of each family can also inform culturally sensitive and contextually relevant approaches.

5.4. Future Directions

The primar focus of the current review and proposed model has been on motor development during infancy. However, the proposed model does not need to be limited to the motor domain. Examinig applicability of our proposed model in other developmental domains would be beneficial and should be entertained in future research. Further, the proposed model is limited to observable infant motor behaviors, observable interactions between parents and children, and parent’s expressed perspcetives. Research with older children that can express their views and beliefs explicitly could additionally incorporate children's perspectives. This approach would enhance our understanding of the reciprocal nature of child-parent interactions over time.

6. Conclusion

Parental perspectives and behaviors shape and influence a child’s development across domains. However, research on the impact of parental perspectives or behaviors on infant motor development remains rare. This may be due to a lack of a theoretical model that is focused on how parental perspectives and behaviors in their ecological context act to shape infant motor behaviors and development specifically. To address this gap, we propose a new holistic model centered on infants’ observable motor behaviors and explicitly including parental perspectives and behaviors as factors shaping motor developmental outcomes. In contrast to prior models, the proposed model separates parental beliefs from their behaviors, situates parent-child interactions within a larger ecological context, and includes bi-directional relations between infant behavior and both parental beliefs and behaviors. We hope that the proposed model will be applied to prior research and will generate new hypotheses for future research on the complex factors shaping infant motor development.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- S. H. Landry, “The role of parents in early childhood learning,” Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development, 2008.

- M. H. Bornstein, “Human Infancy . . . and the Rest of the Lifespan,” Annual review of psychology, vol. 65, pp. 121–158, 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Mowder, “Parent Development Theory: understanding parents, parenting perceptions and parenting behaviors,” Journal of Early Childhood and Infant Psychology, vol. 1, 2005, Accessed: Mar. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A220766550/AONE?u=anon~9e39eb25&sid=googleScholar&xid=bad70291.

- S. Goldberg, “SOCIAL COMPETENCE IN INFANCY: A MODEL OF PARENT-INFANT INTERACTION,” Merrill-Palmer Quarterly of Behavior and Development, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 163–177, Jul. 1977.

- M. H. Bornstein, D. L. Putnick, and J. T. D. Suwalsky, “Parenting cognitions → parenting practices → child adjustment? The standard model,” Dev Psychopathol, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 399–416, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Silver, L. Elliott, and M. E. Libertus, “When beliefs matter most: Examining children’s math achievement in the context of parental math anxiety,” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, vol. 201, p. 104992, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Silver, Y. Chen, D. K. Smith, C. S. Tamis-LeMonda, N. Cabrera, and M. E. Libertus, “Mothers’ and fathers’ engagement in math activities with their toddler sons and daughters: The moderating role of parental math beliefs,” Front. Psychol., vol. 14, p. 1124056, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Cannon and H. P. Ginsburg, “‘Doing the Math’: Maternal Beliefs About Early Mathematics Versus Language Learning,” Early Education & Development, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 238–260, Apr. 2008. [CrossRef]

- J.-A. LeFevre, S.-L. Skwarchuk, B. L. Smith-Chant, L. Fast, D. Kamawar, and J. Bisanz, “Home numeracy experiences and children’s math performance in the early school years.,” Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 55–66, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Musun-Miller and B. Blevins-Knabe, “Adults’ beliefs about children and mathematics: how important is it and how do children learn about it?,” Early Dev. Parent., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 191–202, Dec. 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. Sonnenschein, C. Galindo, S. R. Metzger, J. A. Thompson, H. C. Huang, and H. Lewis, “Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Math Development and Children’s Participation in Math Activities,” Child Development Research, vol. 2012, pp. 1–13, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. L. Zippert and G. B. Ramani, “Parents’ Estimations of Preschoolers’ Number Skills Relate to at-Home Number-Related Activity Engagement: Parents’ Estimates of Child’s Number Skills,” Inf Child Dev, vol. 26, no. 2, p. e1968, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Maloney, G. Ramirez, E. A. Gunderson, S. C. Levine, and S. L. Beilock, “Intergenerational Effects of Parents’ Math Anxiety on Children’s Math Achievement and Anxiety,” Psychol Sci, vol. 26, no. 9, pp. 1480–1488, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Lynch, J. Anderson, A. Anderson, and J. Shapiro, “Parents’ Beliefs About Young Children’s Literacy Development And Parents’ Literacy Behaviors,” Reading Psychology, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 1–20, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- G. E. Bingham, “Maternal Literacy Beliefs and the Quality of Mother-Child Book-reading Interactions: Assoications with Children’s Early Literacy Development,” Early Education & Development, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 23–49, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- L. Baker and D. Scher, “BEGINNING READERS’ MOTIVATION FOR READING IN RELATION TO PARENTAL BELIEFS AND HOME READING EXPERIENCES,” Reading Psychology, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 239–269, Oct. 2002. [CrossRef]

- L. Baker, D. Scher, and K. Mackler, “Home and family influences on motivations for reading,” Educational Psychologist, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 69–82, Mar. 1997. [CrossRef]

- J. Puccioni, “Parents’ Conceptions of School Readiness, Transition Practices, and Children’s Academic Achievement Trajectories,” The Journal of Educational Research, vol. 108, no. 2, pp. 130–147, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Manz and C. B. Bracaliello, “Expanding home visiting outcomes: Collaborative measurement of parental play beliefs and examination of their association with parents’ involvement in toddler’s learning,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 36, pp. 157–167, 33 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Rowe and A. Casillas, “Parental goals and talk with toddlers,” Infant and Child Development, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 475–494, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Coleman and K. H. Karraker, “Maternal self-efficacy beliefs, competence in parenting, and toddlers’ behavior and developmental status,” Infant Mental Health Journal, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 126–148, Mar. 2003. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Leonard and E. L. Hill, “Review: The impact of motor development on typical and atypical social cognition and language: a systematic review,” Child Adolesc Ment Health, p. n/a-n/a, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Libertus and P. Hauf, “Editorial: Motor Skills and Their Foundational Role for Perceptual, Social, and Cognitive Development,” Front. Psychol., vol. 8, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Franchak, K. S. Kretch, and K. E. Adolph, “See and be seen: Infant-caregiver social looking during locomotor free play,” Dev Sci, vol. 21, no. 4, p. e12626, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Gibson and A. D. Pick, An ecological approach to perceptual learning and development. Oxford ; Oxford University Press, 2000.

- E. C. Marcinowski, T. Tripathi, L. Hsu, S. Westcott McCoy, and S. C. Dusing, “Sitting skill and the emergence of arms-free sitting affects the frequency of object looking and exploration,” Dev Psychobiol, vol. 61, no. 7, pp. 1035–1047, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. C. Soska, K. E. Adolph, and S. P. Johnson, “Systems in development: Motor skill acquisition facilitates three-dimensional object completion.,” Developmental Psychology, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 129–138, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Lobo and J. C. Galloway, “Postural and Object-Oriented Experiences Advance Early Reaching, Object Exploration, and Means-End Behavior,” Child Development, vol. 79, no. 6, pp. 1869–1890, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. E. Adolph and C. S. Tamis-LeMonda, “The Costs and Benefits of Development: The Transition From Crawling to Walking,” Child Development Perspectives, vol. 8, no. 4, p. 6, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Iverson, “Developmental Variability and Developmental Cascades: Lessons From Motor and Language Development in Infancy,” Curr Dir Psychol Sci, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 228–235, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Masten and D. Cicchetti, “Developmental cascades,” Dev Psychopathol, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 491–495, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. Gesell, Infancy and human growth. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1928.

- A. Gesell, “The Developmental Morphology of Infant Behavior Pattern,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 139–143, 1932. [CrossRef]

- A. Gesell and C. (Strunk) Amatruda, The embryology of behavior : the beginnings of the human mind. in Classics in developmental medicine ; no. 3. London: MacKeith, 1988.

- M. B. McGraw, The neuromuscular maturation of the human infant. in The neuromuscular maturation of the human infant. New York, NY, US: Columbia University Press, 1943, p. 140.

- C. K. M. R. Formiga and M. B. M. Linhares, “Motor Skills: Development in Infancy and Early Childhood,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Elsevier, 2015, pp. 971–977. [CrossRef]

- A. Sameroff, “A Unified Theory of Development: A Dialectic Integration of Nature and Nurture,” Child Development, vol. 81, no. 1, pp. 6–22, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- H. L. Cintas, “Cross-Cultural Similarities and Differences in Development and the Impact of Parental Expectations on Motor Behavior.pdf.” Pediatric Physical Therapy, 1995.

- L. B. Smith and E. Thelen, “Development as a dynamic system.,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 7, no. 8, pp. 343–348, 2003. [CrossRef]

- E. Thelen, “Dynamic Systems Theory and the Complexity of Change,” Psychoanalytic Dialogues, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 255–283, Apr. 2005. [CrossRef]

- E. Thelen and L. B. Smith, A Dynamic Systems Approach to the Development of Cognition and Action. The MIT Press, 1994. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Spencer, S. Perone, and A. T. Buss, “Twenty Years and Going Strong: A Dynamic Systems Revolution in Motor and Cognitive Development: Dynamic Systems Revolution in Motor and Cognitive Development,” Child Development Perspectives, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 260–266, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Vygotsky, Mind in Society. Harvard University Press, 1978. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Liu and R. Matthews, “Vygotsky’s philosophy: Constructivism and its criticisms examined,” International Education Journal, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 386–399, 2005.

- U. Bronfenbrenner, The ecology of human development : experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1979.

- U. Bronfenbrenner and S. J. Ceci, “Nature-Nurture Reconceptualized in Developmental Perspective: A Bioecological Model,” Psychological Review, 1994.

- U. Härkönen, “The Bronfenbrenner ecological systems theory of human development,” 2007.

- N. M. Vélez-Agosto, J. G. Soto-Crespo, M. Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer, S. Vega-Molina, and C. García Coll, “Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory Revision: Moving Culture From the Macro Into the Micro,” Perspect Psychol Sci, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 900–910, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Gomes, R. F. Ribeiro, B. V. Prat, L. D. C. Magalhães, and R. L. D. S. Morais, “Parental practices and beliefs on motor development in the first year of life,” Fisioter. mov., vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 769–779, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Graciosa, P. A. M. Ferronato, R. Drezner, and E. De Jesus Manoel, “Emergence of locomotor behaviors: Associations with infant characteristics, developmental status, parental beliefs, and practices in typically developing Brazilian infants aged 5 to 15 months,” Infant Behavior and Development, vol. 76, p. 101965, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Hopkins and T. Westra, “MATERNAL EXPECTATIONS OF THEIR INFANTS‘ DEVELOPMENT: SOME CULTURAL DIFFERENCES,” Develop Med Child Neuro, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 384–390, Jun. 1989. [CrossRef]

- B. Hopkins and T. Westra, “Motor development, maternal expectations, and the role of handling,” Infant Behavior and Development, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 117–122, Jan. 1990. [CrossRef]

- R. Kohen-Raz, “Mental and motor development of kibbutz, institutionalized, and home-reared infants in Israel.,” Child Development, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 489–504, 1968. [CrossRef]

- L. J. P. Steenis, M. Verhoeven, D. J. Hessen, and A. L. Van Baar, “Performance of Dutch Children on the Bayley III: A Comparison Study of US and Dutch Norms,” PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 8, p. e0132871, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Geber and R. F. A. Dean, “THE STATE OF DEVELOPMENT OF NEWBORN AFRICAN CHILDREN,” The Lancet, vol. 269, no. 6981, pp. 1216–1219, Jun. 1957. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Goodnow and W. A. Collins, Development according to parents : the nature, sources, and consequences of parents’ ideas. in Essays in developmental psychology. Hove, East Sussex ; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1990.

- O. P. Ejemen, O. E. Bernard, and D. I. Oluwafemi, “SOCIO-CULTURAL CONTEXT OF DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES IN INFANCY IN SOUTH WEST NIGERIA: A QUALITATIVE STUDY,” European Scientific Journal, ESJ, vol. 11, p. null, 2015.

- C. M. Super, “Environmental Effects on Motor Development: the Case of ‘African Infant Precocity,’” Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 561–567, 1976. [CrossRef]

- T. B. Brazelton, B. Koslowski, and E. Tronick, “Neonatal Behavior among Urban Zambians and Americans,” Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 97–107, 1976. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Capute, B. K. Shapiro, F. B. Palmer, A. Ross, and R. C. Wachtel, “NORMAL GROSS MOTOR DEVELOPMENT: THE INFLUENCES OF RACE, SEX AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS,” Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 635–643, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Lagerspetz, M. Nygåkd, and C. Strandvik, “THE EFFECTS OF TRAINING IN CRAWLING ON THE MOTOR AND MENTAL DEVELOPMENT OF INFANTS,” Scandinavian J Psychology, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 192–197, Sep. 1971. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang et al., “Are infant/toddler developmental delays a problem across rural China?,” Journal of Comparative Economics, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 458–469, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. B. Karasik, C. S. Tamis-LeMonda, O. Ossmy, and K. E. Adolph, “The ties that bind: Cradling in Tajikistan,” PLoS ONE, vol. 13, no. 10, p. e0204428, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. B. Karasik, K. E. Adolph, S. N. Fernandes, S. R. Robinson, and C. S. Tamis-LeMonda, “Gahvora cradling in Tajikistan: Cultural practices and associations with motor development,” Child Development, vol. 94, no. 4, pp. 1049–1067, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- AAP, “Positioning and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS): Update,” Pediatrics (Evanston), vol. 98, no. 6, pp. 1216–1218, 1996. [CrossRef]

- B. E. Davis, R. Y. Moon, H. C. Sachs, and M. C. Ottolini, “Effects of Sleep Position on Infant Motor Development,” Pediatrics, vol. 102, no. 5, pp. 1135–1140, Nov. 1998. [CrossRef]

- L. Hewitt, E. Kerr, R. M. Stanley, and A. D. Okely, “Tummy Time and Infant Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review,” Pediatrics, vol. 145, no. 6, p. e20192168, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Blauw-Hospers and M. Hadders-Algra, “A systematic review of the effects of early intervention on motor development,” Developmental medicine and child neurology, vol. 47, no. 6, pp. 421–432, 2005. [CrossRef]

- L. Moxley-Haegert and L. A. Serbin, “Developmental Education for Parents of Delayed Infants: Effects on Parental Motivation and Children’s Development,” Child Development, 1983.

- A. J. Hughes, S. A. Redsell, and C. Glazebrook, “Motor Development Interventions for Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Pediatrics, vol. 138, no. 4, p. e20160147, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Riethmuller, R. A. Jones, and A. D. Okely, “Efficacy of Interventions to Improve Motor Development in Young Children: A Systematic Review,” Pediatrics (Evanston), vol. 124, no. 4, pp. e782–e792, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Hamilton, J. Goodway, and J. Haubenstricker, “Parent-Assisted Instruction in a Motor Skill Program for At-Risk Preschool Children,” Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 415–426, 1999. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Lobo and J. C. Galloway, “Enhanced Handling and Positioning in Early Infancy Advances Development Throughout the First Year: Handling and Positioning Advance Development,” Child Development, vol. 83, no. 4, pp. 1290–1302, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. Libertus and A. Needham, “Teach to reach: The effects of active vs. passive reaching experiences on action and perception,” Vision Research, vol. 50, no. 24, pp. 2750–2757, Dec. 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. Needham, T. Barrett, and K. Peterman, “A pick-me-up for infants’ exploratory skills: Early simulated experiences reaching for objects using ‘sticky mittens’ enhances young infants’ object exploration skills,” Infant Behavior and Development, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 279–295, Jan. 2002. [CrossRef]

- L. Cote and M. Bornstein, “Cultural and Parenting Cognitions in Acculturating Cultures,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, vol. 34, pp. 323–349, 2003. [CrossRef]

- H. Keller, “Culture and Cognition: Developmental Perspectives,” J Cogn Educ Psych, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 3–8, 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. Kochanska, L. Kuczynski, and M. Radke-Yarrow, “Correspondence between Mothers’ Self-Reported and Observed Child-Rearing Practices,” Child Development, vol. 60, no. 1, 1989.

- R. M. Lerner, S. K. Johnson, and M. H. Buckingham, “Relational Developmental Systems-Based Theories and the Study of Children and Families: Lerner and Spanier (1978) Revisited,” J of Family Theo & Revie, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 83–104, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Piaget, The origins of intelligence in children. in The origins of intelligence in children. New York, NY, US: W W Norton & Co, 1952, p. 419. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Gibson, “Exploratory behavior in the development of perceiving, acting, and the acquiring of knowledge.,” in Annual review of psychology, Vol. 39., in Annual review of psychology. , Palo Alto, CA, US: Annual Reviews, 1988, pp. 1–41.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).