1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), owing to their high mobility, flexible deployment, and cost-effective operation, have found widespread applications in a range of civil and industrial domains, including environmental monitoring, aerial photography, emergency communications, and intelligent transportation systems [

1,

2,

3,

4]. As the technological maturity of UAV platforms continues to improve, swarm-based UAV systems are gaining increasing traction due to their superior spatial coverage, multi-point collaboration, and mission scalability. These UAV swarms, typically coordinated through distributed or hierarchical control architectures, are envisioned to support complex tasks requiring real-time situational awareness and large-scale data processing. However, their onboard processing capabilities are constrained by limited size, weight, and power budgets, posing a significant challenge to the realization of intelligent, autonomous aerial operations [

5].

To address this bottleneck, computational offloading has emerged as a promising solution, allowing UAVs to offload compute-intensive tasks—such as object detection, trajectory planning, and sensor fusion—to edge servers or cloud infrastructure [

6,

7,

8]. Existing works in this domain primarily focus on optimizing task allocation, modeling wireless communication channels, and designing adaptive scheduling strategies [

9,

10,

11]. Approaches such as joint trajectory planning and dynamic computation partitioning have been proposed to improve overall offloading efficiency. Meanwhile, the adoption of high-capacity communication technologies, such as millimeter-wave (mmWave) and device-to-device (D2D) links, has further enhanced the feasibility of real-time task migration. However, UAV swarms operating in dynamic and dense environments still suffer from co-channel interference, intermittent connectivity, and channel fading—factors that severely degrade the quality-of-service (QoS) of computation offloading systems. In recent years, federated learning (FL) has attracted growing interest as a privacy-preserving distributed learning paradigm that enables collaborative model training across multiple UAVs or edge devices without directly sharing raw data. Integrating FL into multi-agent systems can significantly enhance the swarm’s adaptability and generalization by allowing decentralized knowledge sharing and continual learning [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Against this backdrop, cell-free massive multiple-input multiple-output (CF-mMIMO) has been proposed as a promising wireless architecture to enhance spectral efficiency, coverage uniformity, and user-centric service provisioning [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Unlike conventional cellular networks, CF-mMIMO eliminates cell boundaries by deploying a large number of distributed access points (APs), all jointly coordinated by a central processing unit (CPU). This architecture has recently been explored for UAV communications, offering potential advantages in mitigating inter-UAV interference, enhancing link robustness, and supporting highly mobile devices in a scalable fashion. Moreover, when combined with edge/cloud computing, CF-mMIMO can facilitate ultra-reliable and low-latency task offloading in complex aerial environments [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Nevertheless, most existing studies remain limited to theoretical analysis or idealized simulations, with relatively few works addressing real-world deployment or experimental verification of such systems.

To the best of our knowledge, practical platforms that jointly leverage UAV swarm coordination, CF-mMIMO communication, and distributed computation frameworks (e.g., cloud-edge collaboration and FL) are still at an early stage [

25]. Existing prototypes typically simplify the wireless front-end (e.g., adopting centralized Wi-Fi or LTE links) or fail to exploit the potential of distributed optimization across communication and computation domains. Furthermore, challenges such as real-time synchronization, delay compensation, and adaptive formation control in decentralized swarm environments remain largely underexplored. To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a comprehensive UAV swarm communication and computation framework that integrates cloud-edge-end collaboration with CF-mMIMO technologies. The proposed system is designed to enhance the scalability, efficiency, and reliability of computational offloading in multi-UAV scenarios. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We design a lightweight dynamic task migration framework that enables flexible workload allocation between onboard UAV processors and remote edge/cloud servers. This synergy significantly alleviates the SWaP-induced processing limitations of UAVs, achieving over reduction in onboard computational load, as validated through extensive experimental evaluation.

A cell-free massive MIMO-based communication architecture tailored for UAV swarms is proposed, featuring over-the-air synchronization and distributed delay compensation mechanisms. These techniques address key challenges such as inter-RRU coordination, timing alignment, and CSI acquisition in dynamic and decentralized swarm environments.

We build a hardware-in-the-loop experimental testbed consisting of nine UAVs equipped with real-time sensing and distributed control capabilities. A flocking-inspired formation control algorithm is integrated to ensure coordinated swarm mobility, and system-level experiments under object detection tasks demonstrate improved reliability and latency performance compared to traditional centralized solutions.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. We introduce the system model in

Section 2, and in

Section 3, we present key technologies for the proposed system. Prototype system and experimental validation are discussed in

Section 4. Finally, we draw our conclusions in

Section 5.

2. System Design

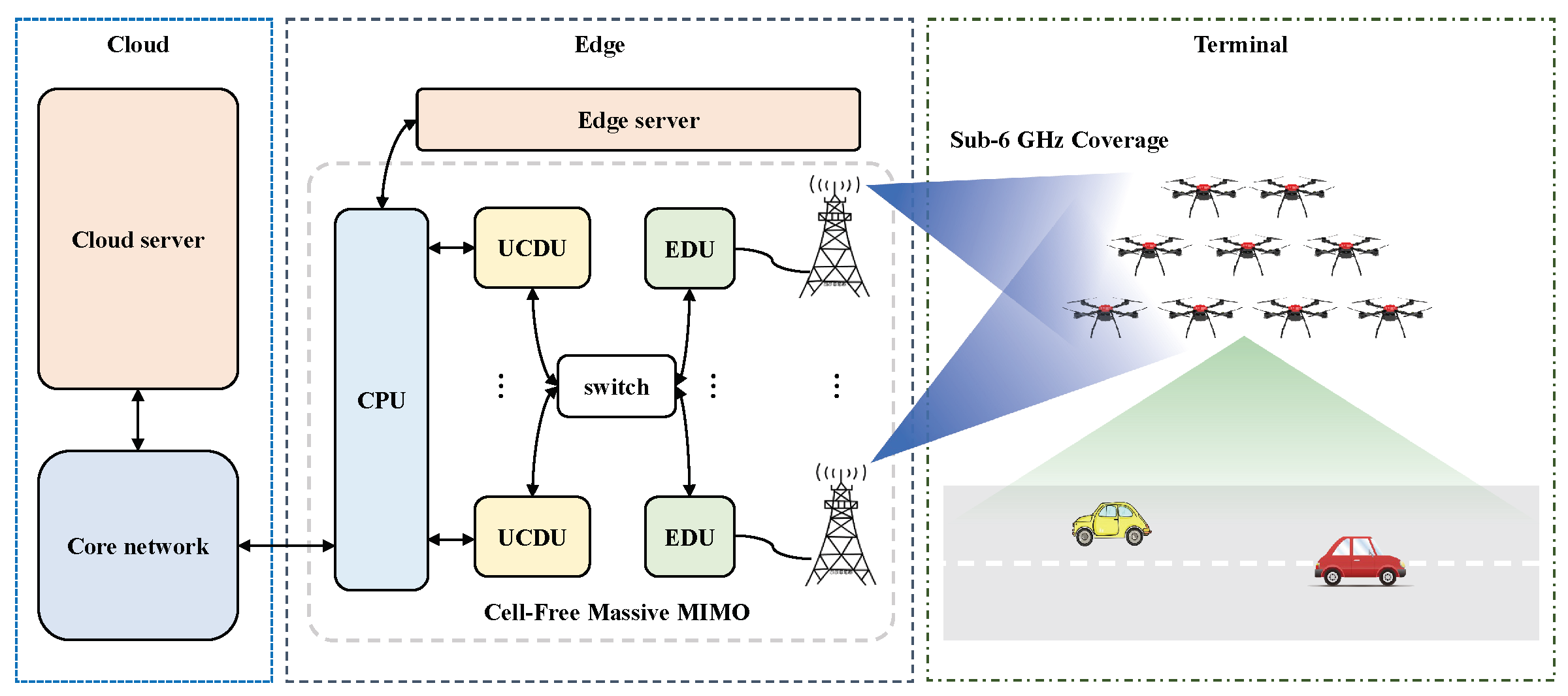

The proposed system architecture, depicted in

Figure 1, leverages a CF-mMIMO-driven cloud-edge-terminal collaborative framework for UAV swarms. This hierarchical architecture contains three tiers:

Cloud tier: Integrates cloud servers and core networks for centralized computation and global resource management;

Edge tier: Deploys distributed CF-mMIMO transceivers with edge servers to enable spatial multiplexing and low-latency processing;

Terminal tier: Comprises a swarm of K single-antenna UAVs for visual perception tasks.

The hierarchical structure and functionalities of each tier are detailed below.

2.1. Cloud Tier

In this tier, the cloud server performs the following core functions: algorithmic model training, real-time inference, task scheduling, and comprehensive monitoring of resources, tasks, and network status. The algorithmic model training relies on the robust computational capabilities of cloud-based servers, where optimization is achieved through advanced artificial intelligence (AI) models or iterative algorithms. Real-time inference leverages pre-trained models to generate predictions promptly upon receiving new data, requiring low latency and high throughput. The task scheduling mechanism dynamically orchestrates resource allocation to maximize parallelism and efficiency in multi-task execution, while integrating fault-tolerant strategies to ensure resilience against potential failures. The real-time resource monitoring system tracks resource usage to dynamically adjust allocations. The task monitoring system ensures timely handling of faults by real-time tracking of task status. The network monitoring evaluates performance in real-time to guarantee efficient and secure data transmission. Data and command exchange is facilitated between the core network and edge-tier CPUs through bidirectional interaction. These functionalities are interdependent, collectively forming a highly efficient and reliable system.

2.2. Edge Tier

The edge server centrally manages task scheduling for UAV swarms through real-time data acquisition. By leveraging the real-time status, positional data, and task priorities of all UAVs, the system optimizes task allocation to ensure efficient resource utilization. Furthermore, edge servers continuously monitor system resources, swarm task status, data traffic, and network performance metrics to dynamically optimize communication efficiency among UAV and access points (APs). This centralized management and intelligent scheduling approach not only enhances real-time responsiveness to swarm operations but also improves the overall efficiency of task execution.

Edge servers establish reliable connectivity with UAV swarms via the CF-mMIMO architecture. The architecture ensures robust coverage in dynamic environments through large-scale deployment of APs, playing a critical role in enhancing communication reliability and reducing latency. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the proposed architecture comprises

N APs,

M edge distributed unit (EDU),

M user-centric distributed unit (UCDU), and a central processing unit (CPU). The APs handle radio frequency (RF) signal reception/transmission across Sub-6 GHz frequency bands, while the EDU executes distributed precoding and reception processing. The UCDU manages data distribution and combining operations.

In the considered system, it is assumed that no inter-UAV communication exists, thereby resulting in independent tasks. Furthermore, each UAV is served by N APs, where each AP is equipped with antennas. The implementation details of uplink and downlink transmissions are presented separately.

During the uplink phase, the received signal at the

n-th AP can be expressed as

where

denotes the channel coefficient between the

k-th UAV and

n-th AP,

represents the transmitted signal from the

k-th UAV, and

denotes additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) with power

at

n-th AP.

By employing detector

at the

n-th AP, the transmitted signal of the

k-th UAV can be collaboratively detected as

where

is the indicator function satisfies

if and only if the

k-th UAV is served by the

n-th AP. In a fully distributed architecture, each AP is limited to local channel state information (CSI), i.e.,

, and thus performs non-cooperative signal detection (e.g., conventional maximum ratio combining (MRC)). This decentralized strategy inevitably induces significant performance degradation, while full collaboration imposes prohibitive fronthaul overhead.

To address this challenge, following the CF-mMIMO architecture in [

18], multiple APs are interconnected with a dedicated EDU for signal detection. This configuration improves collaborative processing performance through integration of additional cooperative APs while maintaining system scalability. Specifically, each user may associate with multiple EDUs but only one UCDU. After demultiplexing multi-user data streams, EDUs forward them to the associated UCDU, which performs signal aggregation from distributed EDUs. The composite partial minimum mean squared error (P-MMSE) detector at the

m-th EDU is formulated as

where

denote the transmit power of the

k-th UAV,

represent the set of UAVs associated with the

m-th EDU, and

denote the equivalent channel between the

i-th UAV and the

m-th EDU. Substituting (

3) into (

2) yields the recovered uplink signal from the UAVs.

In the downlink phase, the received signal at the

k-th UAV is expressed as

where

denotes the precoding vector for the

k-th UAV at the

m-th EDU Similarly, the downlink data stream for same UAV is exclusively transmitted from the UCDU to multiple EDUs, enabling a downlink coherent joint transmission (CJT) through coordinated beamforming across distributed EDUs.

2.3. Terminal Tier

Each UAV is equipped with a flight control unit (FCU), terminal processor, and communication module. The FCU acquires real-time state data including position, velocity, and attitude. The terminal processor handles mission-specific data processing, such as preliminary analysis of camera-captured video streams. Both processed results and raw data are then transmitted in real-time through the communication module to edge and cloud servers for subsequent management, analytical operations, and decision-making optimization. In this paper, we leverage the proposed cloud-edge-end architecture to offload computational tasks from UAVs to ground-based servers, thereby achieving a substantial reduction in computational energy consumption and enhanced operational endurance for UAVs.

3. UAV Formation Control Technologies

UAV formation control techniques primarily include the leader–follower approach, virtual structure method, consensus-based control, artificial potential field method, and behavior-based control.

Among these, the leader–follower approach is currently the most widely adopted and mature method. It features a relatively simple control structure and is easy to implement. However, this method is highly dependent on the leader UAV, and any malfunction of the leader may result in the failure of the entire formation. To address this limitation, a virtual leader can be introduced as the overall formation reference. The position and velocity of this virtual leader are estimated and shared among UAVs in real time. This design enhances the fault tolerance of the formation and reduces its reliance on a single physical leader.

The virtual structure method conceptualizes the UAV formation as a rigid geometric configuration. During coordinated flight, each UAV maintains a fixed relative position within this virtual structure. When the formation changes its shape or trajectory, individual UAVs simply track their assigned virtual coordinates, enabling the formation to adaptively follow pre-defined inspection paths. This method ensures geometric consistency but poses challenges in large-scale implementations due to the rigidity of the structural assumptions.

The consensus-based method enables each UAV to update its state by exchanging information with neighboring UAVs, ultimately achieving global agreement on variables such as position, velocity, or heading. This approach is well-suited for distributed networks and enhances the formation’s responsiveness to dynamic environments. It also improves system robustness, as the loss or failure of a single UAV does not compromise the overall stability. However, consensus algorithms are typically complex and impose stringent requirements on communication channel capacity and latency. Prolonged communication delays or packet losses may prevent the formation from maintaining consistent states across all UAVs.

The artificial potential field method, widely used in trajectory planning, models the influence of obstacles and targets as virtual attractive and repulsive forces. While the goal exerts an attractive force on UAVs, obstacles exert repulsive forces to avoid collisions. The resultant force governs UAV motion and navigation. Although this method is simple and offers good real-time performance, it is limited in handling UAV kinematic constraints, and thus is rarely used in precise formation control tasks.

The behavior-based control method categorizes UAV responses into four fundamental behaviors: collision avoidance, obstacle avoidance, target acquisition, and formation maintenance. Each UAV determines its control actions based on weighted behavior responses to sensory inputs. Inspired by biological swarm intelligence, this method offers high flexibility and fault tolerance. However, it lacks the ability to maintain strict formation geometry and poses difficulties in mathematical stability analysis.

To ensure safe operation in large-scale UAV swarms, collision avoidance between UAVs and dynamic network reconfiguration must be considered. Among the existing formation control strategies, the leader–follower method suffers from poor anti-interference performance and single-point failure risk; the virtual structure method lacks flexibility for large-scale swarm task assignment; and the behavior-based method cannot guarantee global formation stability.

Considering these limitations, we adopt a flocking-based distributed formation control strategy. The flocking algorithm combines the advantages of consensus theory and artificial potential fields, and classifies UAVs, obstacles, and target points as -agents, -agents, and -agents, respectively. Under three key rules—separation, cohesion, and velocity alignment—UAVs can maintain a desired formation shape and move uniformly toward a target direction, while avoiding collisions and ensuring safe inter-UAV spacing. Moreover, flocking supports dynamic splitting and merging of UAV groups, offering excellent scalability and adaptability. The control rules are summarized as follows:

Separation: Each UAV is repelled by the sum of repulsive forces from neighboring agents to avoid collisions.

Cohesion: Each UAV is attracted toward neighboring agents to maintain team compactness.

Velocity alignment: Each UAV adjusts its velocity to match the average velocity of its neighbors, ensuring synchronized motion across the swarm.

Based on the aforementioned rules, considering the realistic swarm flight environment, the flocking algorithm adopted in this work is designed as follows.

3.1. Separation

For local repulsive forces, a simple semi-spring model is employed, using a linearly distance-dependent central velocity term. Interaction begins only within a maximum range

, beyond which repulsion is ignored

where

is the linear gain of the repulsive force, and

is the distance between agent

i and

j. The total repulsive force on agent

i from all neighbors is

3.2. Velocity Alignment

Velocity alignment is achieved by introducing a velocity term based on the difference in velocity vectors among nearby agents. The objective is to synchronize motions and reduce self-induced oscillations due to delays or noise. A smooth velocity decay function,

, based on an ideal braking curve is adopted, with constant acceleration at high speed and exponential convergence at low speed

where

r is the distance to the target stopping point,

a is the preferred acceleration, and

p is a linear gain that determines the crossover between two deceleration phases.

The fundamental principle of the velocity alignment term is to constrain the velocity difference between any two agents such that it does not exceed the maximum allowed by the ideal braking curve at a given distance. As such, this alignment mechanism can be treated as a motion planning term within the force-based motion model

where

,

denotes the linear coefficient for reducing velocity alignment error,

is the velocity relaxation term that allows a certain degree of velocity difference to exist independently of the inter-agent distance. The variable

refers to the distance between agent

i and the predicted stopping point ahead of agent

j. Parameters

and

represent the pairwise linear gain and acceleration parameters, respectively. The amplitude of the speed difference between agent

i and

j is denoted by

. The total velocity alignment term for agent

i with respect to all other agents is given by

In addition, the locality condition of the velocity alignment mechanism is implicitly ensured by defining a maximum interaction range . On the other hand, this formulation allows for flexible scalability in the velocity domain. Specifically, for swarms operating at higher speeds, it is beneficial to begin reducing velocity differences at larger distances to prevent potential collisions and improve formation coherence.

3.3. Collision Avoidance and Obstacle Avoidance

Long-range attraction is not an explicit part of this flocking system. To keep the agents together, a bounded flying arena is defined for the agents, surrounded by soft-repelling virtual walls. One ideal way to define such a repulsion is to define virtual "shield" agents near the arena walls. These virtual agents are rushing towards the arena at a certain velocity. Real agents near the walls should relax their velocities to the velocity of the virtual agents. The velocity alignment term for the virtual agents is

where

,

is the location of the virtual agent. Parameter

, where

is the speed of the virtual agent, perpendicular to the edge of the wall polygon pointing inwards towards the arena,

is the base virtual agent speed.

is the dynamic speed coefficient. For each wall or obstacle, multiple virtual agents can be defined, located at different distances to enhance obstacle avoidance. The same concept can be used to avoid convex obstacles within the arena, but with agents moving outward from the obstacle, rather than inward, as described above for the arena. Another difference is that while all wall polygon edges spawn a separate virtual agent within the arena, obstacles are represented with a single virtual agent located at the closest point of the obstacle polygon relative to the agent. Therefore, for each agent, a velocity component

can be defined similarly to

, using the same parameters as for the walls.

3.4. Self-Driving

The self-driving term represents the agent’s desired velocity, which aligns with its actual motion direction. To improve adaptability, dynamic self-driving terms can be introduced, including speed adaptation and directional correction.

(1) Speed Adaptation

where

is the basic self-driving speed and

is the speed adaptation coefficient.

(2) Directional Correction

where

is the direction correction term, which is used to adjust the movement direction of the agent.

3.5. Final Desired Velocity

The final desired velocity is computed as the vector sum of all interaction forces:

(1) Dynamic Speed Limits

where

is the basic self-driving speed and

is the speed adaptation coefficient.

(2) Directional Correction

3.6. Solution Based on Flocking control algorithm

The algorithm uses three rules, separation, aggregation, and speed alignment, to ensure that the drone group maintains a fixed distance and constant speed during flight, avoids collisions, and achieves the separation and reorganization of any individual. Compared with traditional centralized or distributed formation control methods, the Flocking algorithm has better flexibility and robustness, can adapt to complex environmental changes, and improves the coordination ability and task execution efficiency of the drone swarm.

|

Algorithm 1: Flocking-Based Swarm Motion Control |

|

4. Experimental Validation

The proposed system was validated through a series of collaborative object detection and computation offloading experiments involving a swarm of nine UAVs. The system demonstrated its capability for cloud-edge-end computational orchestration. Specifically, the cloud server was responsible for receiving onboard video streams and executing target detection inference tasks. The edge server handled UAV swarm mission scheduling, forwarded inference results from the cloud, and displayed detection outputs on the ground control interface. Each UAV’s onboard computer managed video acquisition, formation flight, and gimbal control tasks.

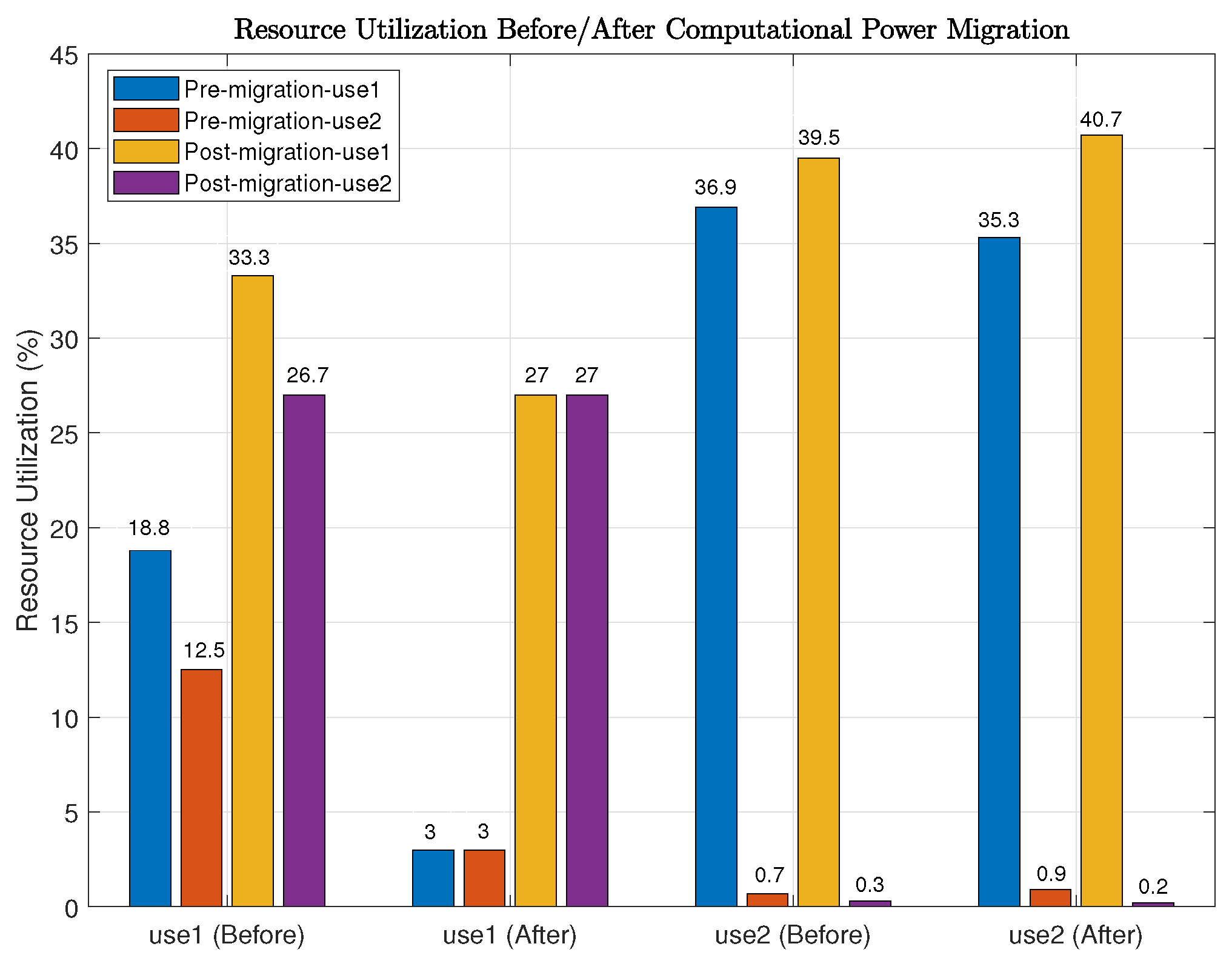

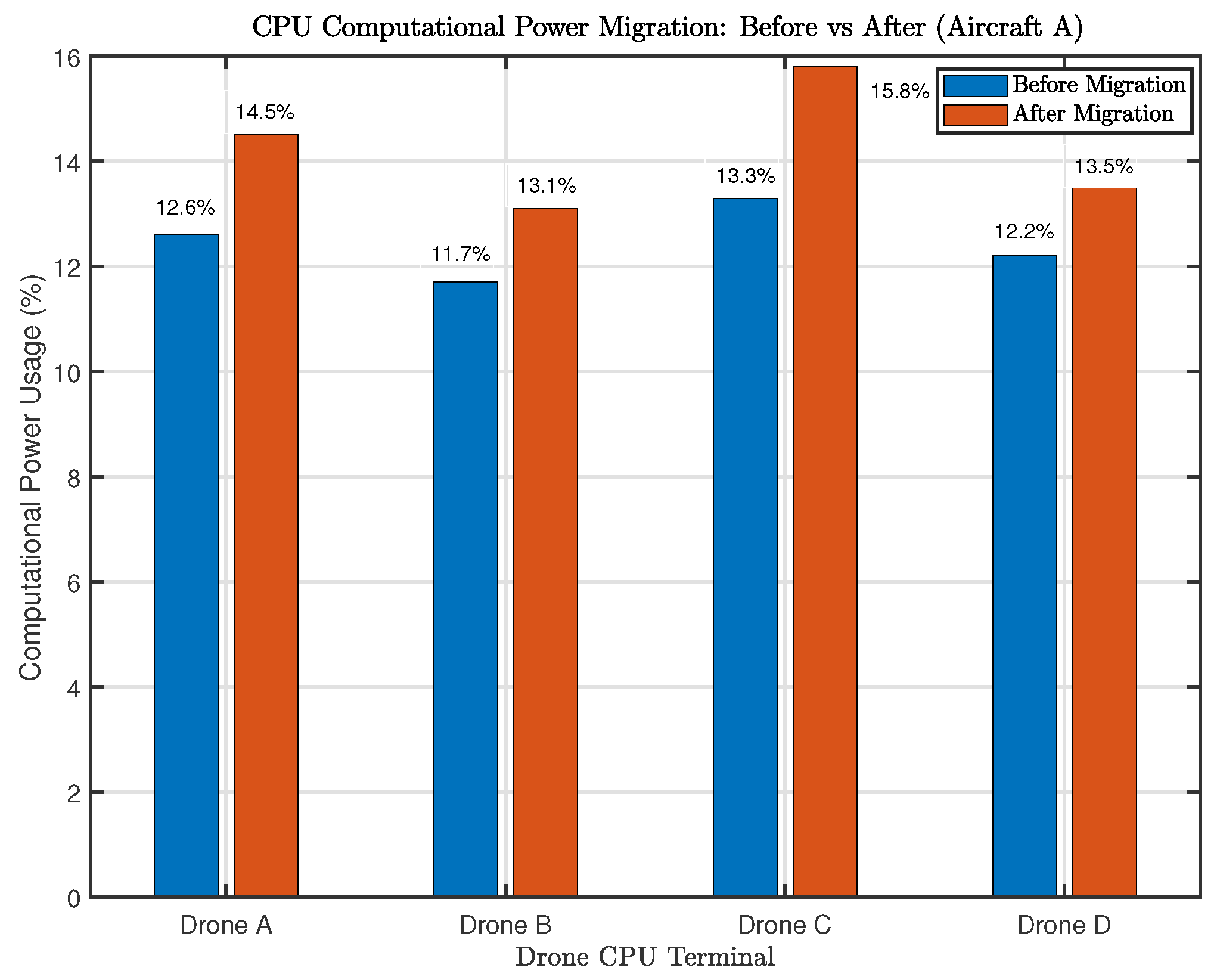

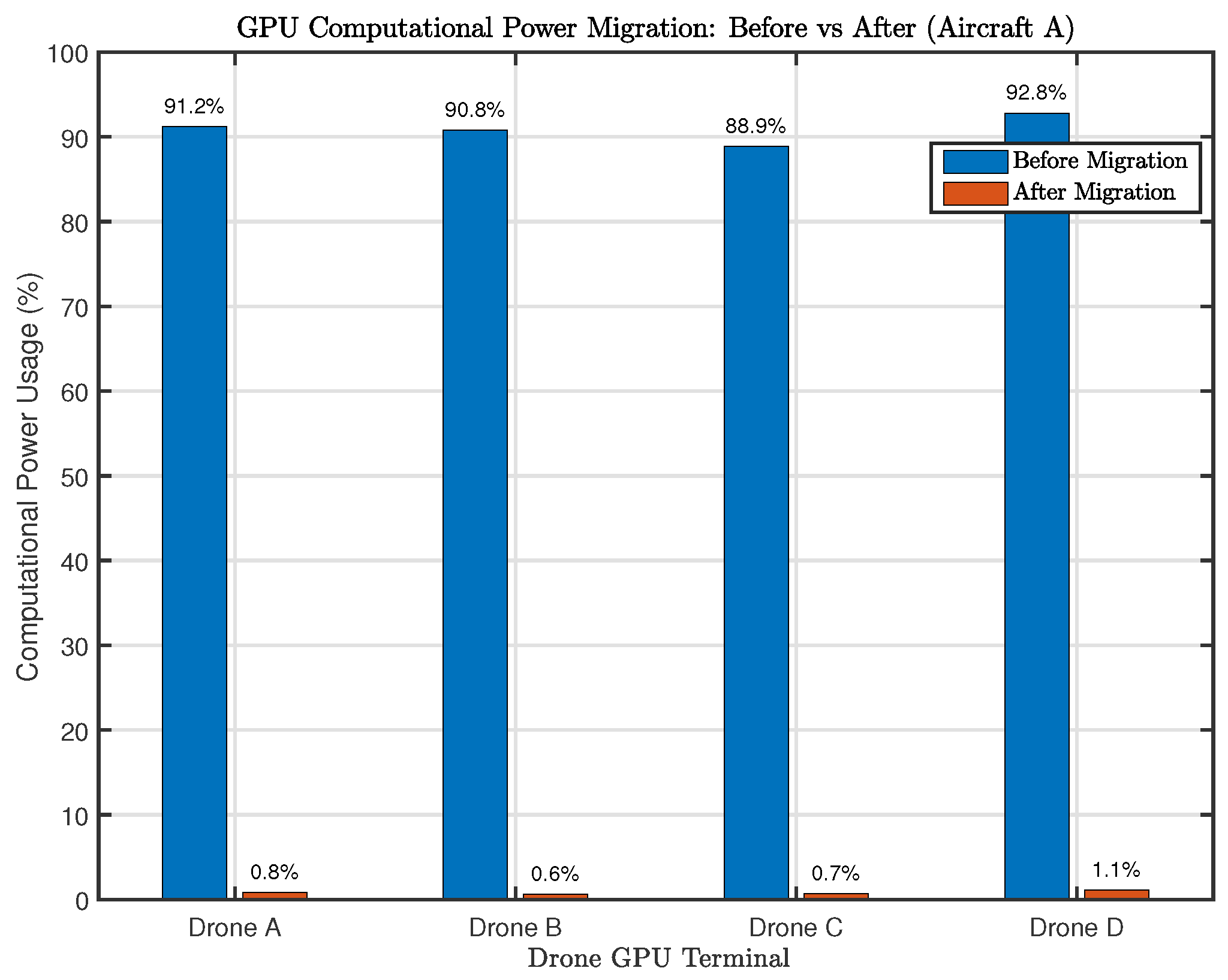

In the experiment, the UAVs ascended to a predefined altitude to perform vehicle detection using local inference. Upon successful detection, the ground control system initiated task migration, offloading the object detection algorithm from the UAV to the cloud server. The inference results were then transmitted through the edge server and displayed as bounding boxes on the ground control interface. Computational resources were monitored using various tools: GPU and CPU usage on the UAVs (Jetson NX) were measured via the jtop tool; the cloud server’s GPU usage was tracked using nvidia-smi, and CPU usage was obtained using the top command, averaging the inference-related CPU loads over all system threads. The edge server’s resource utilization was monitored using the same approach as the cloud server.

Since the adopted YOLOv5 detection algorithm primarily relies on GPU resources, minimal CPU variation was observed before and after task migration. In contrast, GPU utilization exhibited significant changes. After offloading, the cloud server’s GPU usage increased substantially, while the GPU load on selected UAVs dropped sharply.

The test involved all nine UAVs flying in a formation with a horizontal spacing of 8 meters and a hovering altitude of 5 meters. Resource utilization before and after computation migration was recorded and compared.

Figure 2 shows the CPU and GPU usage of the cloud and edge servers,

Figure 3 presents the CPU usage on different UAVs, and

Figure 4 illustrates their GPU usage.

According to the measurements, the cloud server’s CPU utilization increased from and to and , respectively, while its GPU usage rose from to . The edge server’s task-related CPU usage slightly increased from to . For the UAVs:

UAV A: CPU increased from to , GPU dropped from to ;

UAV B: CPU increased from to , GPU dropped from to ;

UAV C: CPU increased from to , GPU dropped from to ;

UAV D: CPU increased from to , GPU dropped from to .

These flight experiments validate the effectiveness of the proposed cloud-edge-end computational orchestration framework and the distributed formation control mechanism. The results demonstrate that after task migration, the target detection algorithm continues to operate correctly. The significant increase in cloud GPU usage and the corresponding reduction in onboard GPU load, without compromising detection accuracy or display latency, confirm the efficiency and reliability of the proposed system.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented an integrated communication and computation framework for UAV swarms, combining cloud-edge-end collaboration with a CF-mMIMO architecture. A lightweight task migration scheme was designed to alleviate the onboard processing burden, while a robust CF-mMIMO protocol with synchronization and delay compensation was implemented to ensure reliable wireless connectivity in dynamic swarm environments. Hardware-in-the-loop experiments demonstrated that the proposed system significantly improves computational efficiency, communication reliability, and end-to-end latency. The results offer valuable insights into scalable and practical solutions for real-time, collaborative UAV applications.

Author Contributions

J.S. was the main author. H.X.L. and W.S. provided the methodology, software, and contructive feedback on every part of this manuscript. W.X. was our supervisor. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program under Grant 2020YFB1806608, and in part by the Special Fund for Key Basic Research in Jiangsu Province No. BK20243015.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- You, X.H.; et al. Towards 6G wireless communication networks: Vision, enabling technologies, and new paradigm shifts. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2020, 64, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; et al. Edge learning for B5G networks with distributed signal processing: Semantic communication, edge computing, and wireless sensing. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Signal Process. 2023, 17, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fei, Z.; Zhang, Y. UAV communications for 5G and beyond: Recent advances and future trends. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 2241–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Xu, W.; You, X.H.; Zhao, C.M.; Wei, K.J. Intelligent reflection enabling technologies for integrated and green Internet-of-Everything beyond 5G: Communication, sensing, and security. IEEE Wireless Commun. 2023, 30, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, M.; Saad, W.; Bennis, M.; Nam, Y.H.; Debbah, M. A tutorial on UAVs for wireless networks: Applications, challenges, and open problems. IEEE Commun. Surveys Tuts. 2019, 21, 2334–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; et al. Joint Offloading and Trajectory Design for UAV-Enabled Mobile Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 1879–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Gong, Y.; Gong, S.; Guo. Y. Joint Task Offloading and Resource Allocation in UAV-Enabled Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 3147–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; et al. ; Energy-Efficient UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing: Resource Allocation and Trajectory Optimization. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 3424–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu. X.; Wong K.; Yang K.; Zheng Z. UAV-Assisted Relaying and Edge Computing: Scheduling and Trajectory Optimization. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2019, 18, 4738–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; et al. Multi-UAV-Enabled Load-Balance Mobile-Edge Computing for IoT Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 6898–6908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; et al. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning for Task Offloading in UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2022, 21, 6949–6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; et al. Empowering over-the-air personalized federated learning via RIS. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2024, 67, 219302–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; et al. Byzantine-Resilient Over-the-Air Federated Learning under Zero-Trust Architecture. arXiv preprint arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; et al. Wireless federated learning over resource-constrained networks: Digital versus analog transmissions. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2024, 23, 14020–14036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; et al. Combating interference for over-the-air federated learning: A statistical approach via RIS. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2025, 73, 936–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.Q.; et al. Cell-free massive MIMO versus small cells. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2017, 16, 1834–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; et al. Experimental performance evaluation of cell-free massive MIMO systems using COTS RRU with OTA reciprocity calibration and phase synchronization. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2023, 41, 1620–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; et al. Full-spectrum cell-free RAN for 6G systems: System design and experimental results. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2023, 66, 130305–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; et al. Robust beamforming design for RIS-aided cell-free systems with CSI uncertainties and capacity-limited backhaul. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2023, 71, 4636–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, J.; Ai, B. UAV communications with WPT-aided cell-free massive MIMO systems. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2021, 39, 3114–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Xu, J.; Xu, W.; Yuen, C.; Swindlehurst, A.L.; Zhao, C.M. On secrecy performance of RIS-assisted MISO systems over Rician channels with spatially random eavesdroppers. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2024, 23, 8357–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, X.; Fei, Z. On the uplink distributed detection in UAV-enabled aerial cell-free mMIMO systems. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2024, 23, 13812–13825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Xu, J.; Xu, W.; Renzo, M. Di; Zhao C.M. Secure outage analysis of RIS-assisted communications with discrete phase control. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 5435–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; et al. Superimposed RIS-phase modulation for MIMO communications: A novel paradigm of information transfer. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2024, 23, 2978–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; et al. UAV-Based Intelligent Sensing Over CF-mMIMO Communications: System Design and Experimental Results. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2025. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).