Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

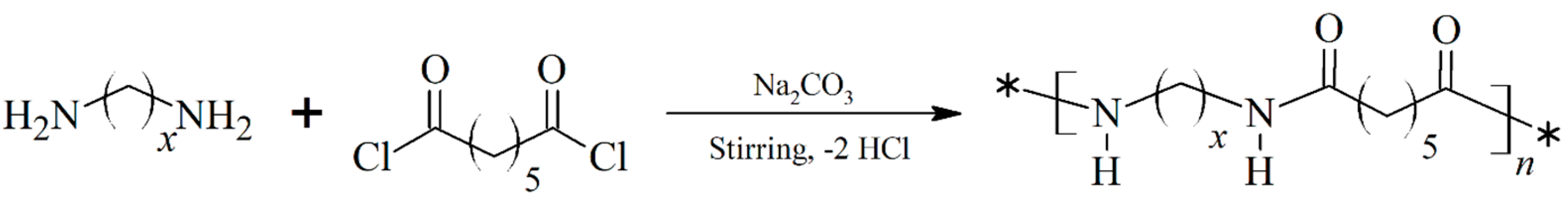

2.2. Synthesis

2.3. Characterization

3. Results

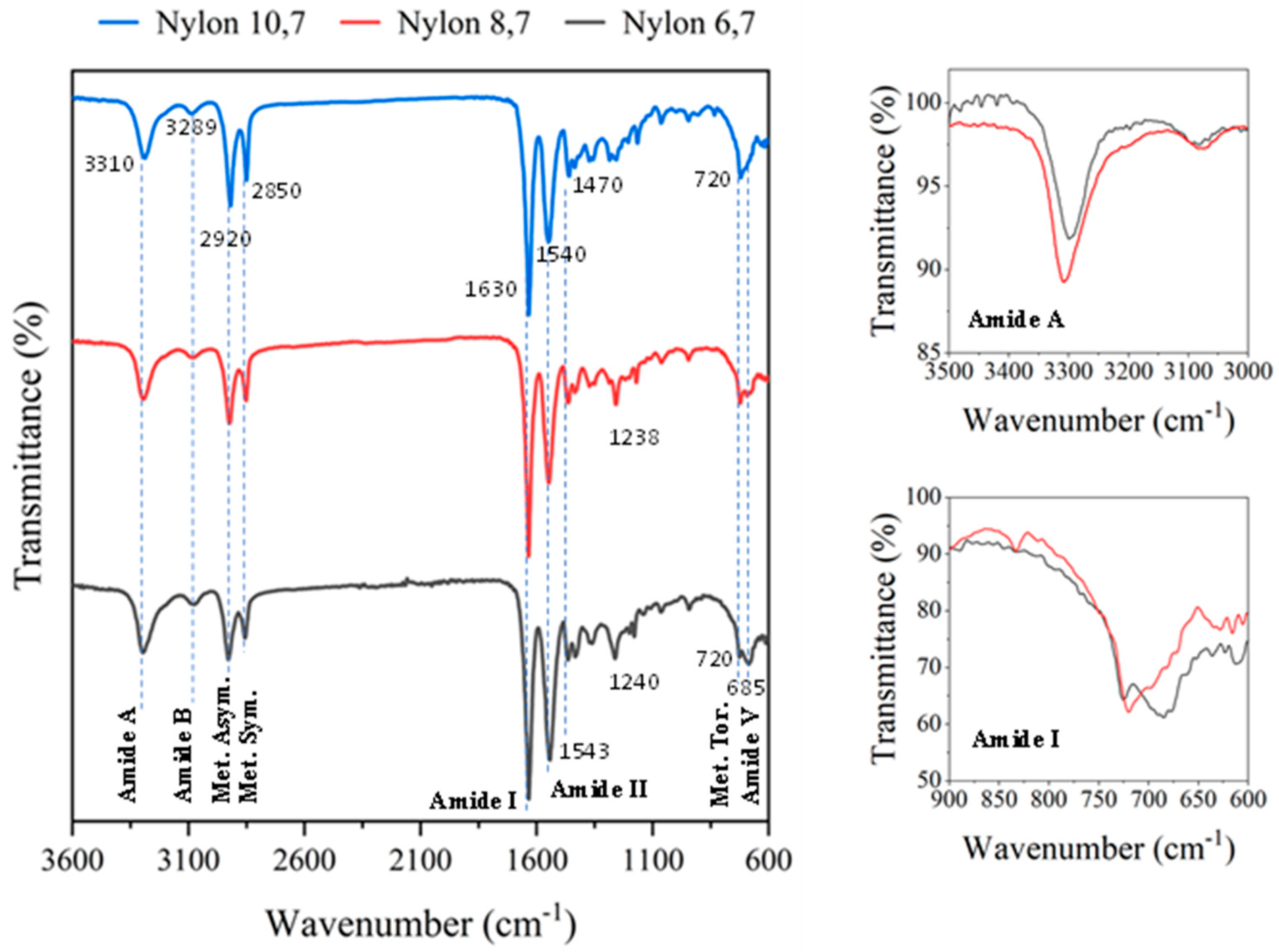

3.1. Synthesis

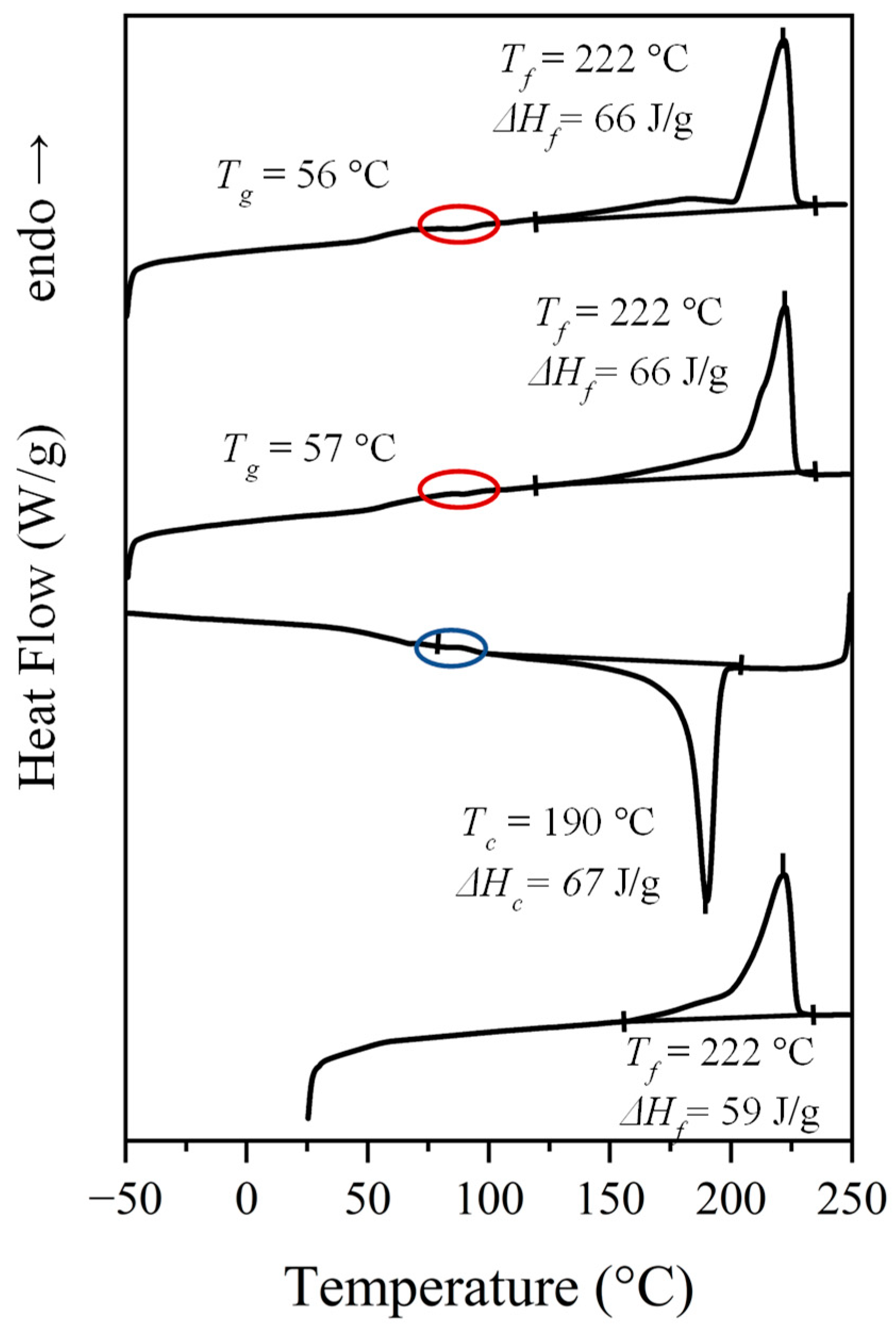

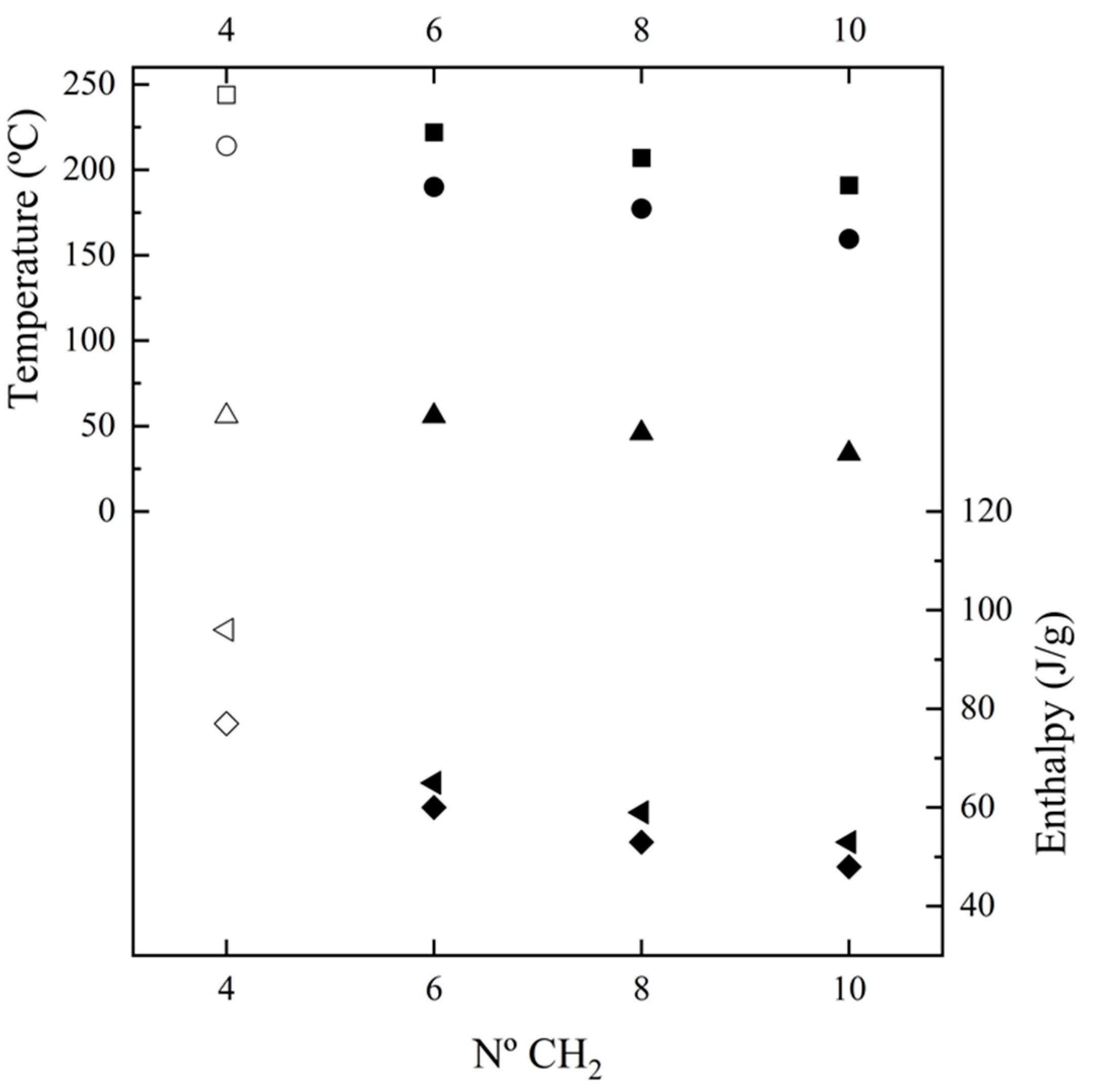

3.2. Calorimetric Analysis

- A complex melting process where a major peak centered at 222 °C, a shoulder around 203 °C and a minor peak/shoulder at 180 °C can be distinguished according to the preparation method (e.g., samples coming from solution precipitation or by melt crystallization). The two high temperature signals may be due to the presence of lamellae with different thicknesses, being the thinner ones susceptible to a folding reorganization during heating. Endothermic processes associated to the fusion of minority phases should be discarded since structural transitions so close to the fusion were not detected in the subsequent synchrotron measurements as then will be explained. This argument is not so clear for the signal around 180 °C since it is a value close to the Brill transition temperature, by contrast the presence of highly defective crystals with low melting peak temperature has also been reported for similar nylons. DSC plots showed also a slow recovery of the base line on both heating and cooling processes, which may be indicative of a continuous structural transition as detected in synchrotron experiments.

- A crystallization process that is characterized by a narrow exothermic peak at an undercooling degree of 30–35 °C (for a cooling rate of 10 °C/min). This peak is followed by a broad exothermic event that extents practically up to the glass transition temperature and that may be associated to a continuous structural transition.

- Some minor events that can be detected in the 80–100 °C interval (see ellipsoids in Figure 4 that point out small exothermic peaks during 2nd and 3rd heating runs and an endothermic peak during cooling).

- A well-defined and reversible glass transition.

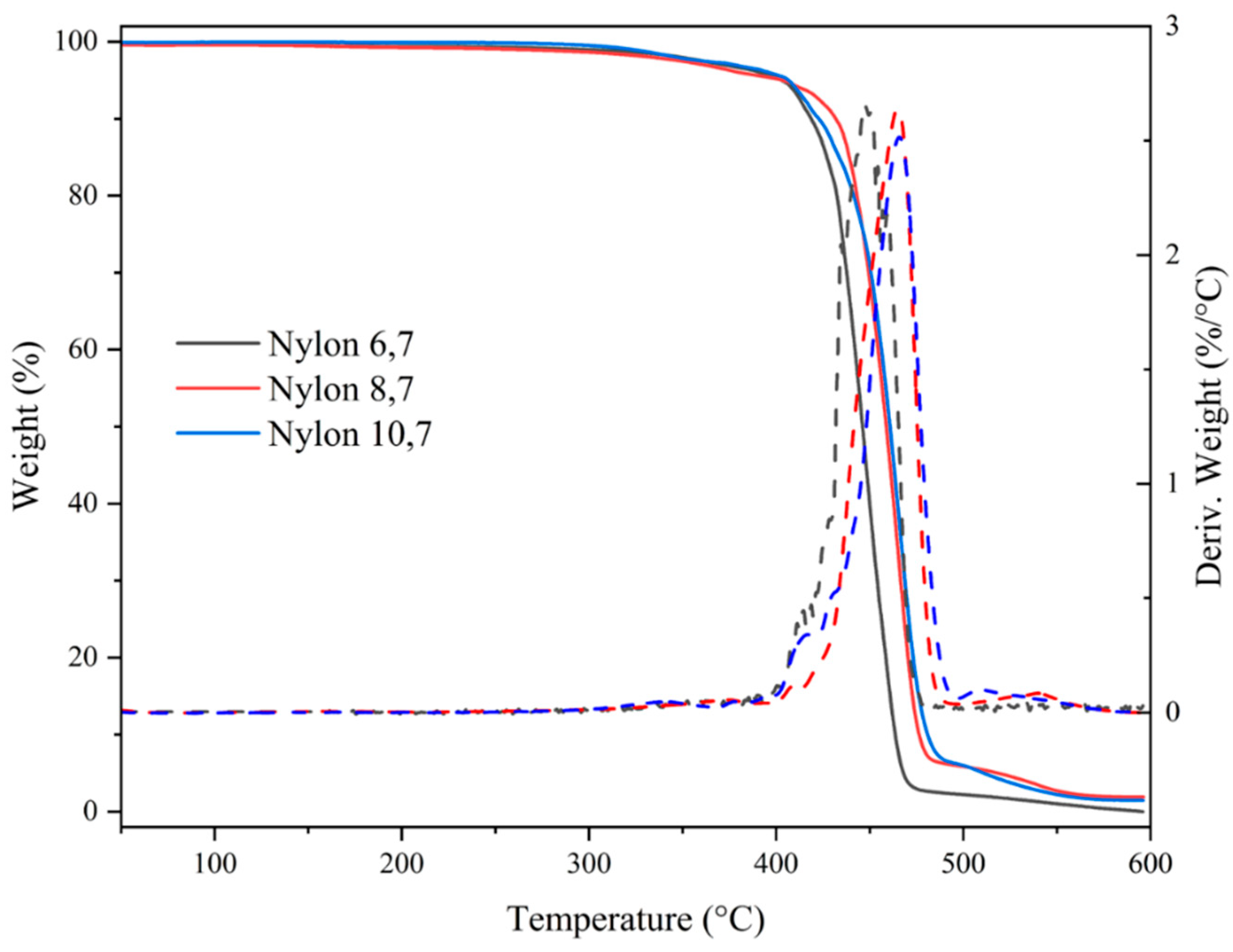

3.3. Thermal Stability

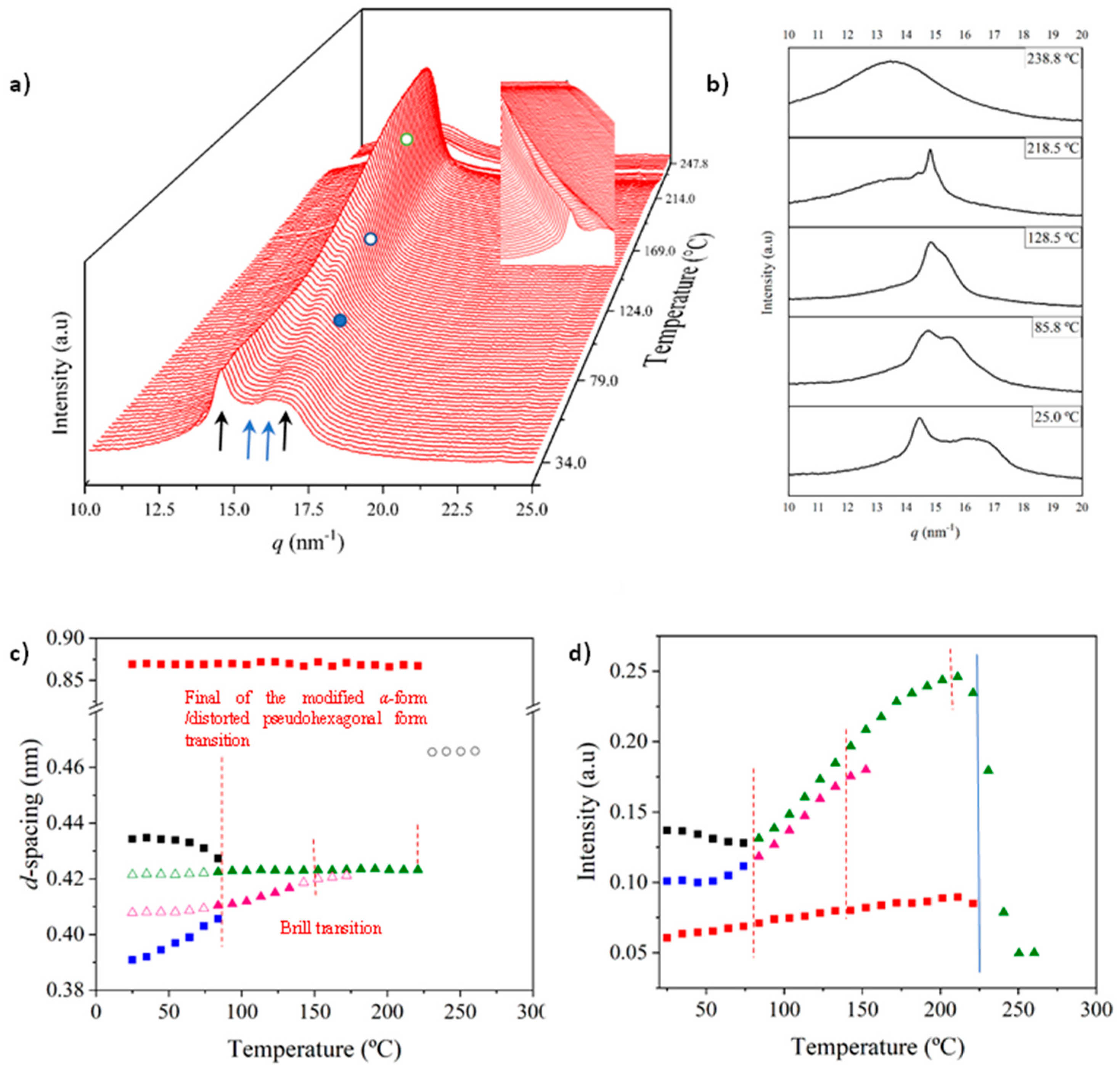

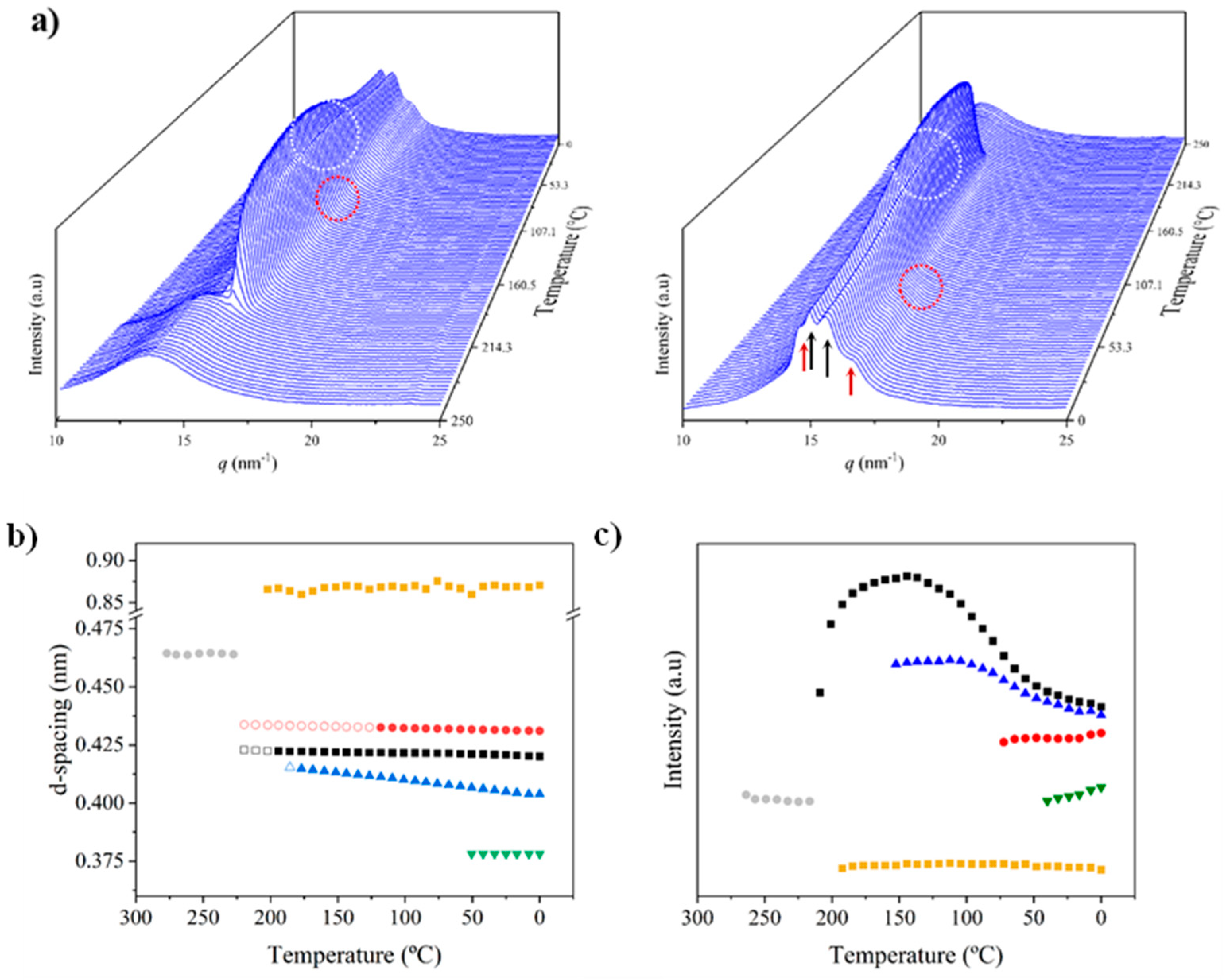

3.4. Structural Transitions of Nylon 6.7 During Heating/Cooling Processes

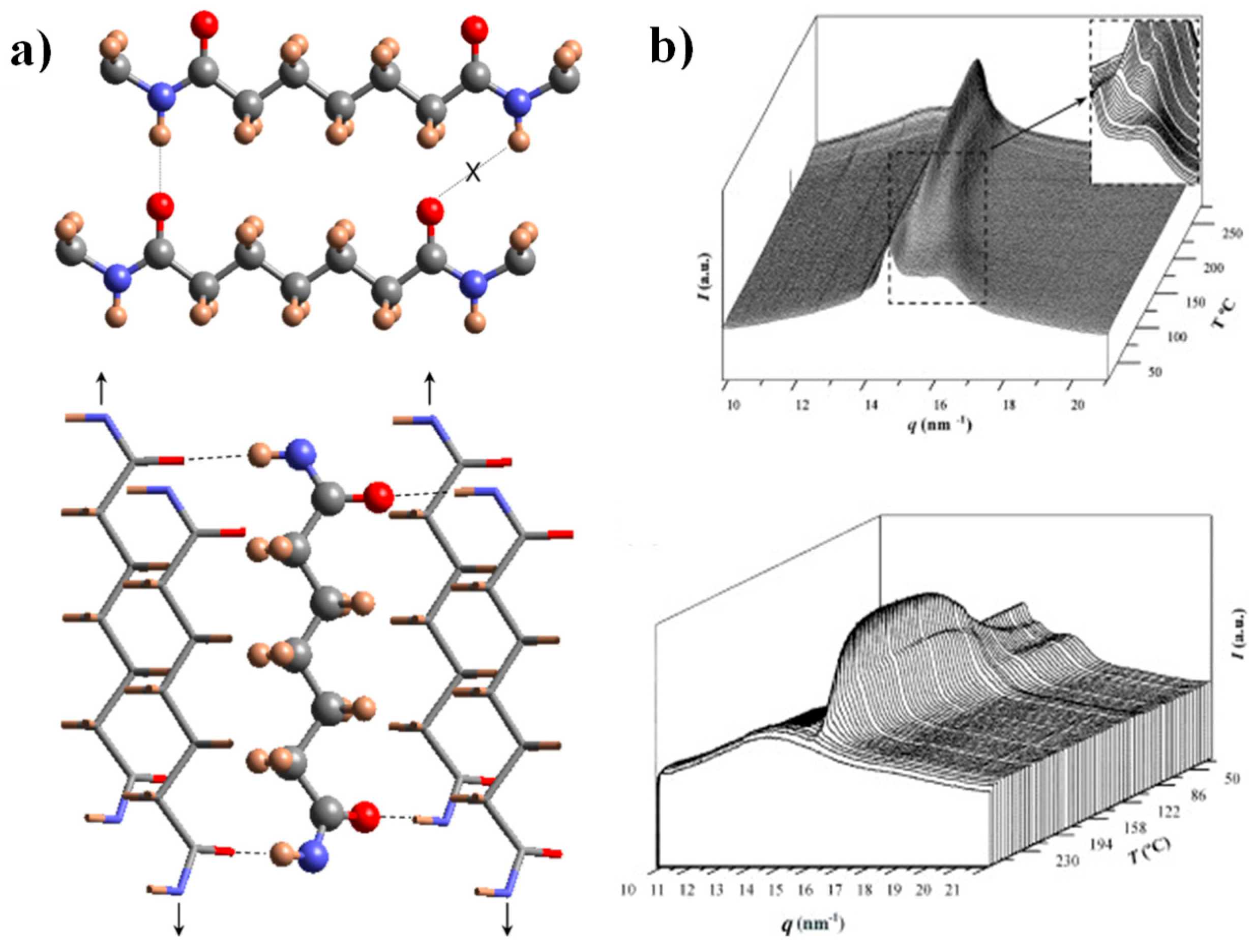

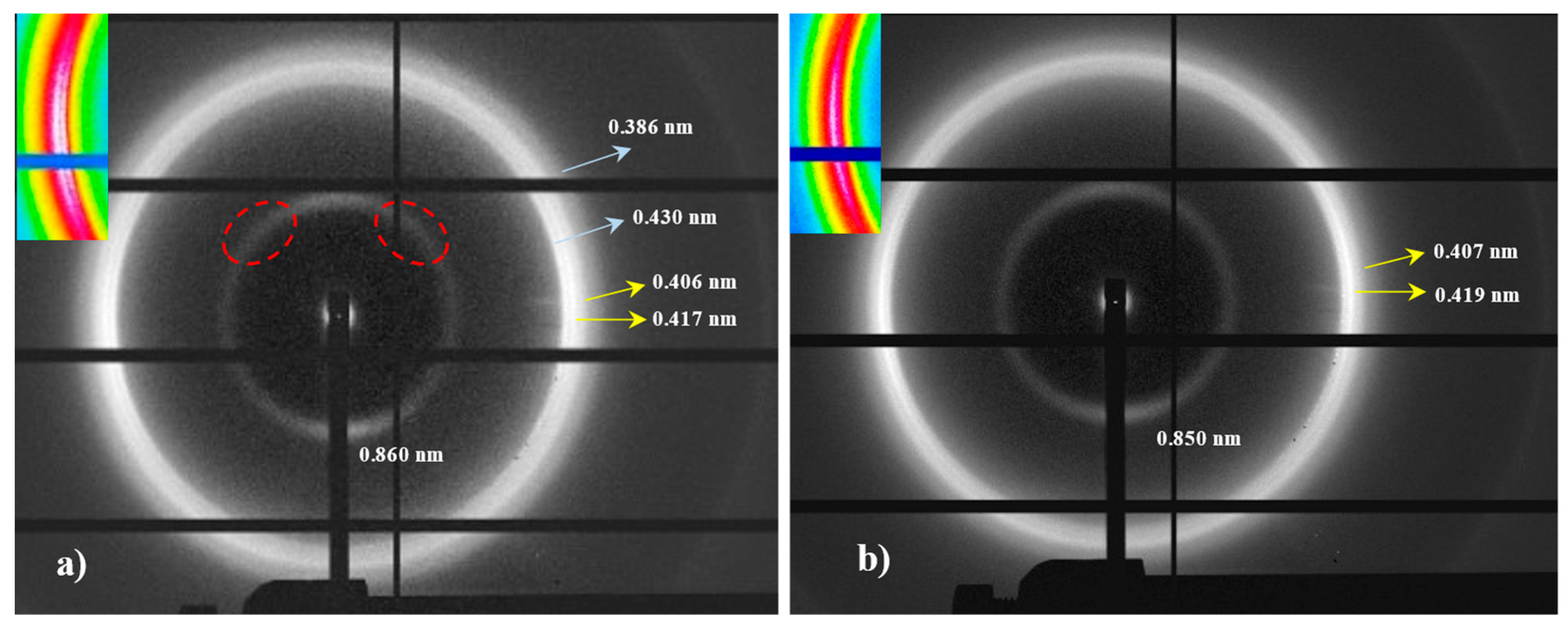

- The initial sample is characterized by the two typical reflections of the α-modified form (i.e., the narrow peak at 0.430 nm and the broad peak at 0.380 nm, see black arrows). In addition, two very small signals at 0.421 nm and 0.404 nm (blue arrows) can be intuited. These indicate a highly distorted pseudohexagonal form due to the clear deviation of a single spacing around 0.415 nm. Observed structures correlate perfectly with forms I and II indicated for nylon 4.7, but for the shake of completeness will be described in the present paper as a modified α-form (2H-bonding directions) and an intermediate distorted pseudohexagonal form.

- A continuous decrease of the intensity of the two reflections associated to the modified α-form can be observed while those associated to the distorted pseudohexagonal form also increased in a continuous way. The process seems to end at a temperature close to 91 °C (see profile in Figure 7b and also the intensity evolution indicated in Figure 7d). It is therefore significant that the structural change does not take place at a specific temperature and corresponds to gradual transformation that involved the arrangement of hydrogen bonds towards the pseudohexagonal form. It was previously suggested that this transformation implied a slight change of conformational angles that lead to an angle close to 60° between consecutive amide bonds of the odd even unit. Note that in disagreement with structural changes described for conventional nylons the spacings of 4.30 nm and 0.380 nm reflections remained practically constant. Nevertheless, the increase of temperature is moderate (i.e., from 25 °C to 91 °C) and consequently changes caused by dilation effects should not be significant. The observed structural transition could not be demonstrated by DSC measurements since no evidence of exothermic or endothermic events were detected in the DSC trace of the first heating run in the temperature range between 25 °C and 91 °C (Figure 4). Similar observations were previously reported for nylon 4.7 [27].

- The two reflections at 0.421 nm and 0.404 nm progressively approach each one (Figure 7c) and join in a single spacing at 0.420 nm at a temperature of 231 °C (Figure 7b,c). Basically, the less intense reflection at the spacing of 0.404 nm has the higher shift and appear as shoulder of the main reflection at temperatures close to 130 °C (Figure 7b). Note that the intensity of the main reflection clearly increases as consequence of the indicated overlapping (Figure 7d).

- When the Brill structure is achieved the intensity of the single reflection at 0.420 is practically constant (Figure 7d).

- Melting process starts at a temperature of 210 °C as evidenced by the decrease of the Bragg reflection and the apparition of an amorphous halo centered at 0.468 nm (Figure 7b,c).

- Evidence of an increase of crystallinity as consequence of a lamellar reordering cannot be deduced from the synchrotron profile evolution (Figure 7a). Note that DSC data indicated a complex melting peak that was associated to an increase of the degree of perfection of constitutive lamellae.

- A long spacing (associated to the 004 reflection) is observed at a spacing of 0.860 nm. This spacing is practically constant during all heating process and consequently is not useful to detect structural transitions

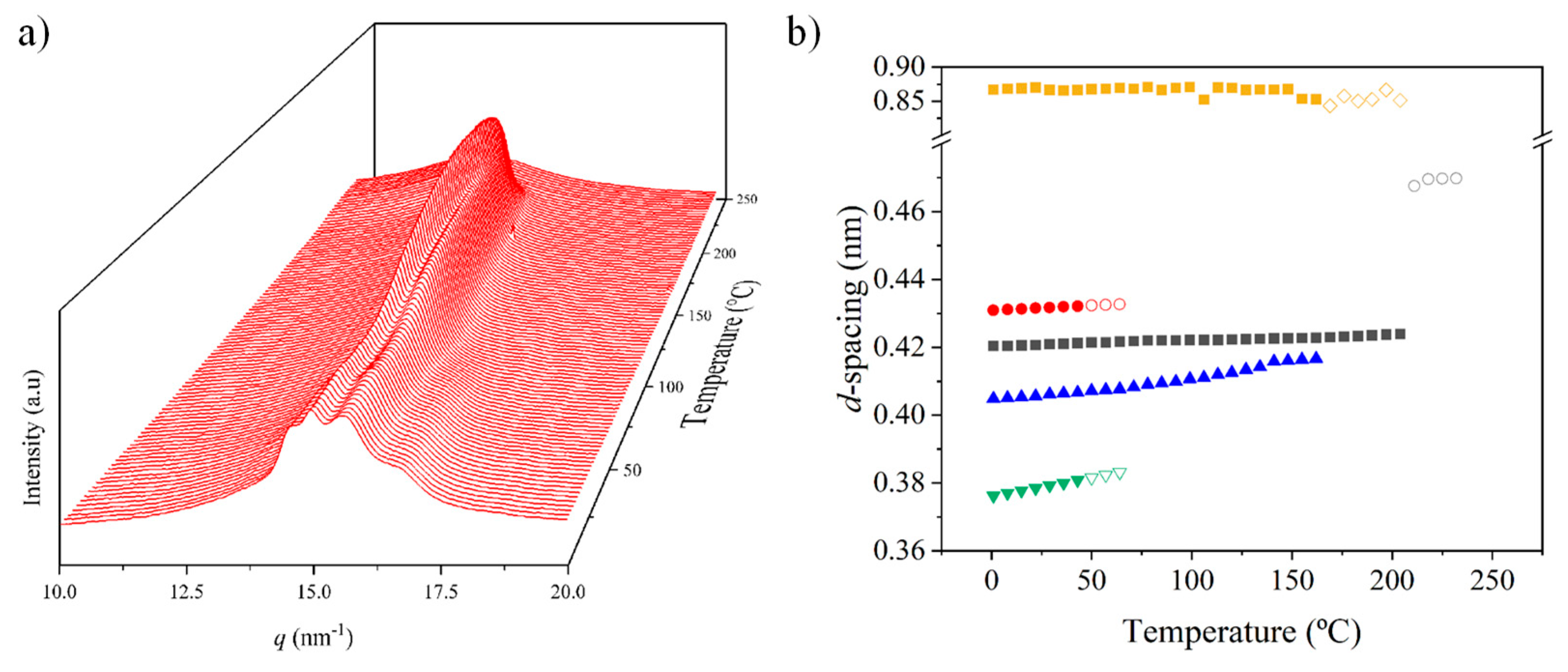

3.5. Structural Transitions of Nylon 8.7 During Heating/Cooling Processes

- The initial profile corresponds to a mixture of the α-modified form with reflections at 0.441 nm and 0.371 nm and the distorted pseudohexagonal form with reflections at 0.424 nm and 0.395 nm. The specific ratio between the two polymorphs becomes the main difference between the profiles of nylons 6.7 and 8.7. Thus, the distorted pseudohexagonal form appeared in a minority ratio in nylon 6.7, while it was slightly predominant in nylon 8.7.

- The intensity of the α-modified form reflections gradually decreased and practically disappeared at 115 °C (see the selected profiles in Figure 12b). The spacings of these reflections remained practically constant up to their disappearance (Figure 12c), being probably not significant a cell dilatation due to the relatively low temperature that was assumed.

- The intensity of reflections associated with the distorted pseudohexagonal form showed and increased with temperature, being possible to distinguish two steps (Figure 12a). The first one is characterized by a gradual and moderate increase and coincides with the intensity decrease of the modified α-form. Therefore, a gradual transformation from the modified α-form to the distorted pseudohexagonal form seems to take place. The second step corresponds to a greater intensity increase and appears associated with the gradual overlapping of the two characteristic reflections. As shown in Figure 12c, the spacing of the reflection at 0.395 nm experiments a remarkable increase with temperature while the spacing of the 0.424 nm reflection remained practically constant.

- At a temperature of 170 °C the Brill transition took place and only a single crystalline reflection at 0.423 nm was observed.

- All crystalline reflections disappeared when temperature reached 220 °C, being the most distinctive feature the presence of the broad amorphous halo at 0.465 nm.

- Only a long spacing reflection with a significant intensity was detected. This reflection corresponded to a spacing of 0.972 nm that was also practically constant during all the heating process.

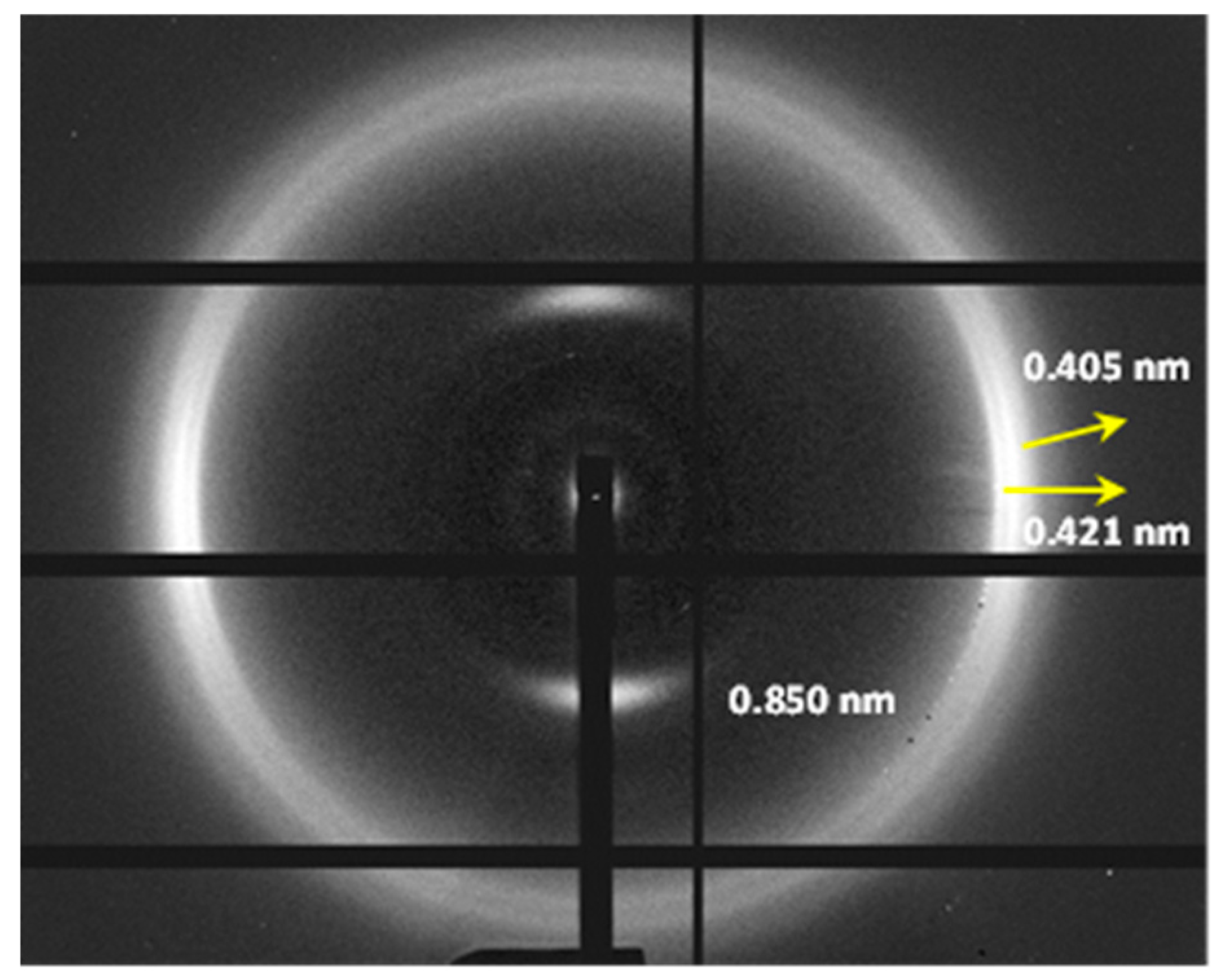

3.6. Structural Transitions of Nylon 10.7 During Heating/Cooling Processes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xenopoulos, A.; Clark, E. Nylon Plastics Handbook; Kohan, M.I. (Eds.) ; Hanser: New York, 1995.

- Wang, L.; Dong, X.; Huang, M.; Müller, A.J.; Wang, D. Self-Associated Polyamide Alloys with Tailored Polymorphism Transition and Lamellar Thickening for Advanced Mechanical Application. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2017, 9, 19238–19247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arioli, M.; Puiggalí, J.; Franco, L. Nylons with Applications in Energy Generators, 3D Printing and Biomedicine. Molecules 2024, 29, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Nylon Industry Https://Www.Reportlinker.Com/P03993523/Global-Nylon-Industry.Html. (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Radzik, P.; Leszczyńska, A.; Pielichowski, K. Modern Biopolyamide-Based Materials: Synthesis and Modification. Polymer Bulletin 2020, 77, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, N.; Yagi, T.; Kojima, K. How Do Bioplastics and Fossil-Based Plastics Play in a Circular Economy? Macromol Mater Eng 2019, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.J.; Caldeira, K.; Matthews, H.D. Future CO 2 Emissions and Climate Change from Existing Energy Infrastructure. Science (1979) 2010, 329, 1330–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, T. Biodegradable and Bio-Based Polymers: Future Prospects of Eco-Friendly Plastics. Angewandte Chemie—International Edition 2015, 54, 3210–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.; Eghbali, N. Green Chemistry: Principles and Practice. Chem Soc Rev 2010, 39, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Chen, K.; Ouyang, P. The Production of Biobased Diamines from Renewable Carbon Sources: Current Advances and Perspectives. Chin J Chem Eng 2021, 30, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, S.; Wittmann, C. Bio-Based Production of the Platform Chemical 1,5-Diaminopentane. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 91, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Yang, J.E.; Ha, J.Y.; Chae, T.U.; Shin, J.H.; Gustavsson, M.; Lee, S.Y. Bio-Based Production of Monomers and Polymers by Metabolically Engineered Microorganisms. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2015, 36, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendisch, V.F.; Mindt, M.; Pérez-García, F. Biotechnological Production of Mono- and Diamines Using Bacteria: Recent Progress, Applications, and Perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 102, 3583–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, T.U.; Kim, W.J.; Choi, S.; Park, S.J.; Lee, S.Y. Metabolic Engineering of Escherichia Coli for the Production of 1,3-Diaminopropane, a Three Carbon Diamine. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 13040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Kyeong, H.H.; Choi, J.M.; Kim, H.S. Rational Design of Ornithine Decarboxylase with High Catalytic Activity for the Production of Putrescine. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 98, 7483–7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aceituno, J.E.; Tereshko, V.; Lotz, B.; Subirana, J.A. Synthesis and Characterization of Polyamides n,3. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiggalí, J.; Aceituno, J.E.; Navarro, E.; Campos, J.L.; Subirana, J.A. Structure of n,3 Polyamides, a Group of Nylons with Two Spatial Hydrogen-Bond Orientations. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 8170–8179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E.; Alemán, C.; Subirana, J.; Puiggalí, J. On the Crystal Structure of Nylon 55. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 5406–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E.; Franco, L.; Subirana, J.A.; Puiggalí, J. Nylon 65 Has a Unique Structure with Two Directions of Hydrogen Bonds. Macromolecules 1995, 28, 8742–8750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E.; Subirana, J.A.; Puiggalí, J. The Structure of Nylon 12,5 Is Characterized by Two Hydrogen Bond Directions as Are Other Polyamides Derived from Glutaric Acid. Polymer (Guildf) 1997, 38, 3429–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Cheng, K.; Liu, T.; Li, N.; Zhang, H.; He, Y. Fully Bio-Based Poly (Pentamethylene Glutaramide) with High Molecular Weight and Less Glutaric Acid Cyclization via Direct Solid-State Polymerization. Eur Polym J 2022, 180, 111618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, M.; Cronan, J.E. Pimelic Acid, the First Precursor of the Bacillus Subtilis Biotin Synthesis Pathway, Exists as the Free Acid and Is Assembled by Fatty Acid Synthesis. Mol Microbiol 2017, 104, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronan, J.E.; Lin, S. Synthesis of the α,ω-Dicarboxylic Acid Precursor of Biotin by the Canonical Fatty Acid Biosynthetic Pathway. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2011, 15, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohsugi, M.; Miyauchi, K.; Tachibana, K.; Nakao, S. Formation of a Biotin Precursor, Pimelic Acid, in Yeasts from C18 Fatty Acids. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1988, 34, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, M.J.; Ragni, M.C.; Hood, I.; Hale, D.E. Azelaic and Pimelic Acids: Metabolic Intermediates or Artefacts? J Inherit Metab Dis 1992, 15, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- “Pimelic Acid.” Merriam-Webster.Com Medical Dictionary. (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- Morales-Gámez, L.; Casas, M.T.; Franco, L.; Puiggalí, J. Structural Transitions of Nylon 47 and Clay Influence on Its Crystallization Behavior. Eur Polym J 2013, 49, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkweather, H.W. Transitions and Relaxations. In Nylon Plastic Handbook; Kohan, M.I., Ed.; Hanser: New York, 1995; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Seguela, R. Overview and Critical Survey of Polyamide6 Structural Habits: Misconceptions and Controversies. Journal of Polymer Science 2020, 58, 2971–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, N.S. Hydrogen Bonding, Mobility, and Structural Transitions in Aliphatic Polyamides. J Polym Sci B Polym Phys 2006, 44, 1763–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, A.Y.; Wachtel, E.; Vaughan, G.B.M.; Weinberg, A.; Marom, G. The Brill Transition in Transcrystalline Nylon-66. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 4455–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, B. Brill Transition in Nylons: The Structural Scenario. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileva, D.; Kolesov, I.; Androsch, R. Morphology of Cold-Crystallized Polyamide 6. Colloid Polym Sci 2012, 290, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, K.; Yoshioka, Y. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the Structural and Mechanical Property Changes in the Brill Transition of Nylon 10/10 Crystal. Polymer (Guildf) 2004, 45, 4337–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olf, H.G.; Peterlin, A. NMR Observations of Drawn Polymers. VII. Nylon 66 Fibers. Journal of Polymer Science Part A-2: Polymer Physics 1971, 9, 1449–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovinger, A.J. Crystallographic Factors Affecting the Structure of Polymeric Spherulites. I. Morphology of Directionally Solidified Polyamides. J Appl Phys 1978, 49, 5003–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovinger, A.J. Crystallographic Factors Affecting the Structure of Polymeric Spherulites. II. X-ray Diffraction Analysis of Directionally Solidified Polyamides and General Conclusions. J Appl Phys 1978, 49, 5014–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, J.H. Formation of Spherulites in Polyamide Melts: Part III. Even-Even Polyamides. Journal of Polymer Science Part A-2: Polymer Physics 1966, 4, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirami, M. SAXD Studies on Bulk Crystallization of Nylon 6.I. Changes in Crystal Structure, Heat of Fusion, and Surface Free Energy of Lamellar Crystals with Crystallization Temperature. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 1984, 23, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, B.; Cheng, S.Z.D.; Li, C.Y. Structure of Negative Spherulites of Even-Even Polyamides. Introducing a Complex Multicomponent Spherulite Architecture. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 5138–5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, C.W.; Garner, E. V.; Bragg, W.L. The Crystal Structures of Two Polyamides (‘Nylons’). Proc R Soc Lond A Math Phys Sci 1947, 189, 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.R.; Bunn, C.W.; Smith, D.J. The Crystal Structure of Polycaproamide: Nylon 6. Journal of Polymer Science 1955, 17, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, Y. The Crystal Structure of Polyheptamethylene Pimelamide (Nylon 77). Die Makromolekulare Chemie 1959, 33, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Gámez, L.; Ricart, A.; Franco, L.; Puiggalí, J. Study on the Brill Transition and Melt Crystallization of Nylon 65: A Polymer Able to Adopt a Structure with Two Hydrogen-Bonding Directions. Eur Polym J 2010, 46, 2063–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmo, C.; Casas, M.T.; Martínez, J.C.; Franco, L.; Puiggalí, J. Thermally Induced Structural Transitions of Nylon 4 9 as a New Example of Even-Odd Polyamides. Polymers (Basel) 2018, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, L.; Cooper, S.J.; Atkins, E.D.T.; Hill, M.J.; Jones, N.A. Nylon 6 9 Can Crystallize with Hydrogen Bonding in Two and in Three Interchain Directions. J Polym Sci B Polym Phys 1998, 36, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, S.K.; Casas, M.T.; Martínez, J.C.; Estrany, F.; Franco, L.; Puiggalí, J. Reversible Changes Induced by Temperature in the Spherulitic Birefringence of Nylon 6 9. Polymer (Guildf) 2015, 76, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmo, C.; Rota, R.; Carlos Martínez, J.; Puiggalí, J.; Franco, L. Temperature-Induced Structural Changes in Even-Odd Nylons with Long Polymethylene Segments. J Polym Sci B Polym Phys 2016, 54, 2494–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiggalí, J.; Franco, L.; Alemán, C.; Subirana, J.A. Crystal Structures of Nylon 5,6. A Model with Two Hydrogen Bond Directions for Nylons Derived from Odd Diamines. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 8540–8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Gámez, L.; Soto, D.; Franco, L.; Puiggalí, J. Brill Transition and Melt Crystallization of Nylon 56: An Odd-Even Polyamide with Two Hydrogen-Bonding Directions. Polymer (Guildf) 2010, 51, 5788–5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaseñor, P.; Franco, L.; Subirana, J.A.; Puiggalí, J. On the Crystal Structure of Odd-Even Nylons: Polymorphism of Nylon 5,10. J Polym Sci B Polym Phys 1999, 37, 2383–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiggalí, J.; Muñoz-Guerra, S.; Lotz, B. Extended-Chain and Three-Fold Helical Forms of Poly(Glycyl-β-Alanine). Macromolecules 1986, 19, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiggalí, J.; Muñoz-Guerra, S.; Subirana, J.A. Morphology and Crystalline Structure of Nylon-2/6. Polymer (Guildf) 1987, 28, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, J.; Puiggalí, J.; Subirana, J.A. Glycine Residues Induce a Helical Structure in Polyamides. Polymer (Guildf) 1994, 35, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormo, J.; Puiggalí, J.; Vives, J.; Fita, I.; Lloveras, J.; Bella, J.; Aymamí, J.; Subirana, J.A. Crystal Structure of a Helical Oligopeptide Model of Polyglycine II and of Other Polyamides: Acetyl-(Glycyl-β-alanyl)2-NH Propyl. Biopolymers 1992, 32, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arioli, M.; Franco, L.; Puiggalí, J. Non-Isothermal Crystallization and Thermal Degradation Studies on Nylons 7.10 and 10.7 as Isomeric Odd-Even and Even-Odd Polyamides. Thermochim Acta 2024, 735, 179721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Krevelen, D.W. Properties of Polymers; 3rd, *!!! REPLACE !!!* (Eds.) ; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, 1990; ISBN 9780080915104.

| Sample | Yield (%) a | Mw (g/mol) a | PDI a | Mw (g/mol) b | PDI b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nylon 6.7 | 70 | 22,500 | 4.20 | 27,500 | 2.15 |

| Nylon 8.7 | 67 | 26,100 | 3.70 | 28,100 | 1.65 |

| Nylon 10.7 | 75 | 29,000 | 3.90 | 35,000 | 1.84 |

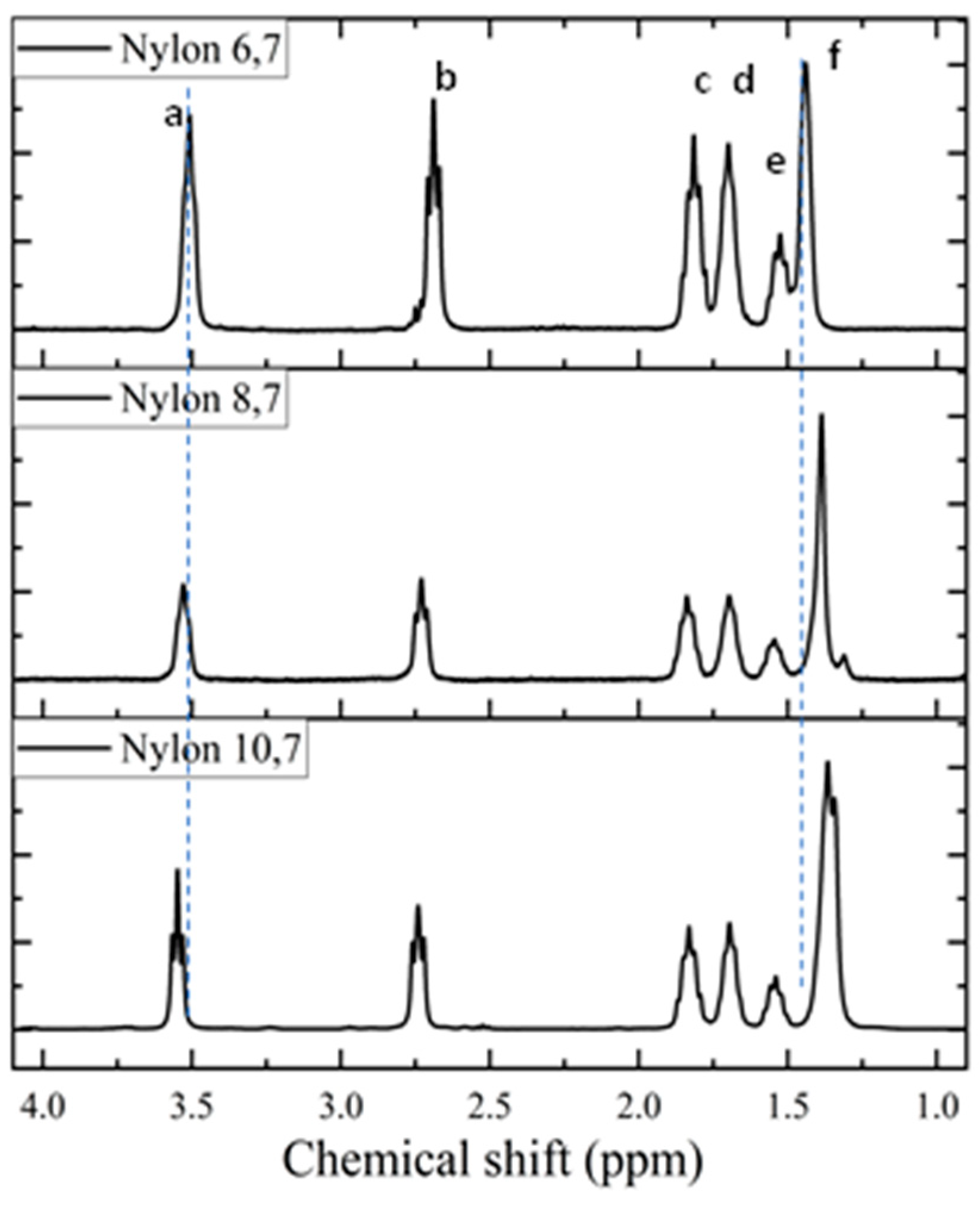

| Peak | δ (ppm) a | Integral | Assignation | Multiplicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 3.51, 3.53, 3.55 | 4H, 4H, 4H | CH2-NH- | t |

| b | 2.69, 2.73, 2.74 | 4H, 4H, 4H | CH2-CO- | t |

| c | 1.82, 1.84, 1.83 | 4H, 4H, 4H | CH2CH2-NH- | m |

| d | 1.70, 1.70, 1.70 | 4H, 4H, 4H | CH2CH2-CO- | m |

| e | 1.51, 1.54, 1.54 | 2H, 2H, 2H | CH2(CH2)2-CO- | m |

| f | 1.44, 1.39, 1.36 | 4H, 8H, 12H | Rest of methylene protons in diamine unit | m |

| Sample | 1st Heating | Cooling | 2nd Heating | 3rd Heating | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tf (°C) | ΔHf (J/g) | Tc (°C) | ΔHc(J/g) | Tg (°C) | Tf (°C) | ΔHf (J/g) | Tg (°C) | Tf (°C) | ΔHf (J/g) | |

| N. 4.7 b | 214, 227, 244 | 96 | 214 | 77 | -e | 227, 244 | 77 | 56 | 228, 243 | 71 |

| N. 6.7 | 190, 222 | 71 | 190 c | 66 | 57 | 213, 222 | 66 | 56 | 183 c, 222 | 66 |

| N. 8.7 | 154, 207 | 66 | 177 c | 60 | 46 | 208d | 60 | 46 | 182, 207 | 61 |

| N. 10.7 | 170, 191 d | 62 | 159 c | 55 | 30 | 177, 193 | 57 | 34 | 174, 193 | 54 |

| Sample | T Onset (°C) | T Max (°C) | 1st Step (%) | Last Step (% and °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nylon 6.7 | 410 | 447 | 5 | n.p. |

| Nylon 8.7 | 427 | 465 | 1 | 4.7, 539 |

| Nylon 10.7 | 421 | 467 | 5 | 6.6, 510 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).