Submitted:

13 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site & Passive Sampling Method

2.2. Passive Sampler Elution & Total Nucleic Acid Extraction

2.3. Digital PCR

2.4. 16S rRNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics

2.5. Clinical Surveillance Data

2.6. Data Analyses & Availability

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. dPCR QA/QC

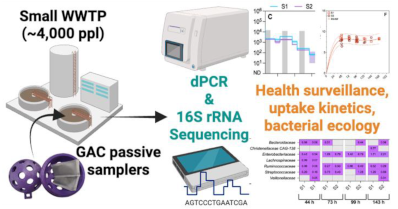

3.2. Endogenous Wastewater Viruses

3.3. Endogenous Wastewater Bacteria & ARGs

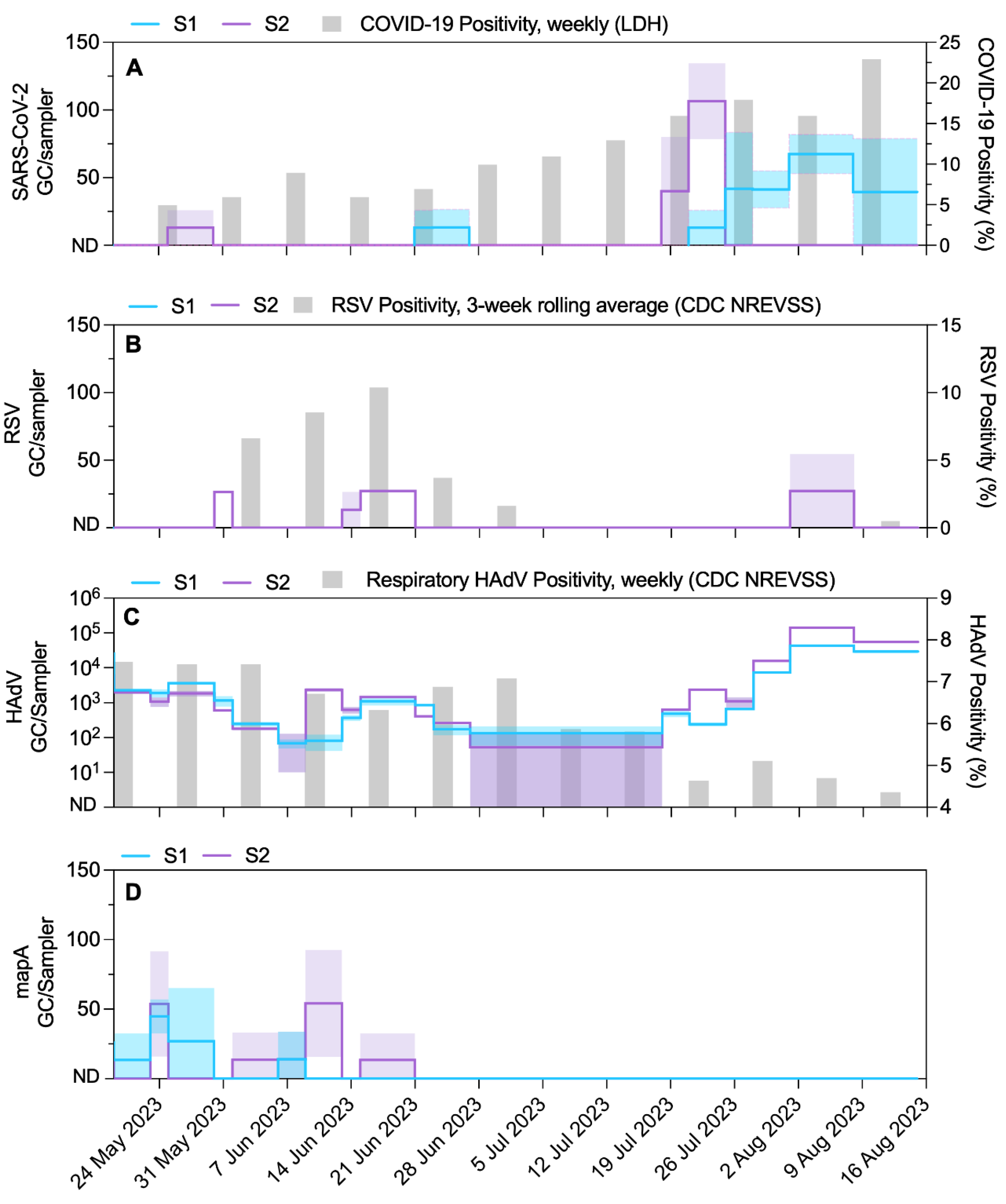

3.4. GAC-Derived Bacterial Community Inferred by 16S rRNA

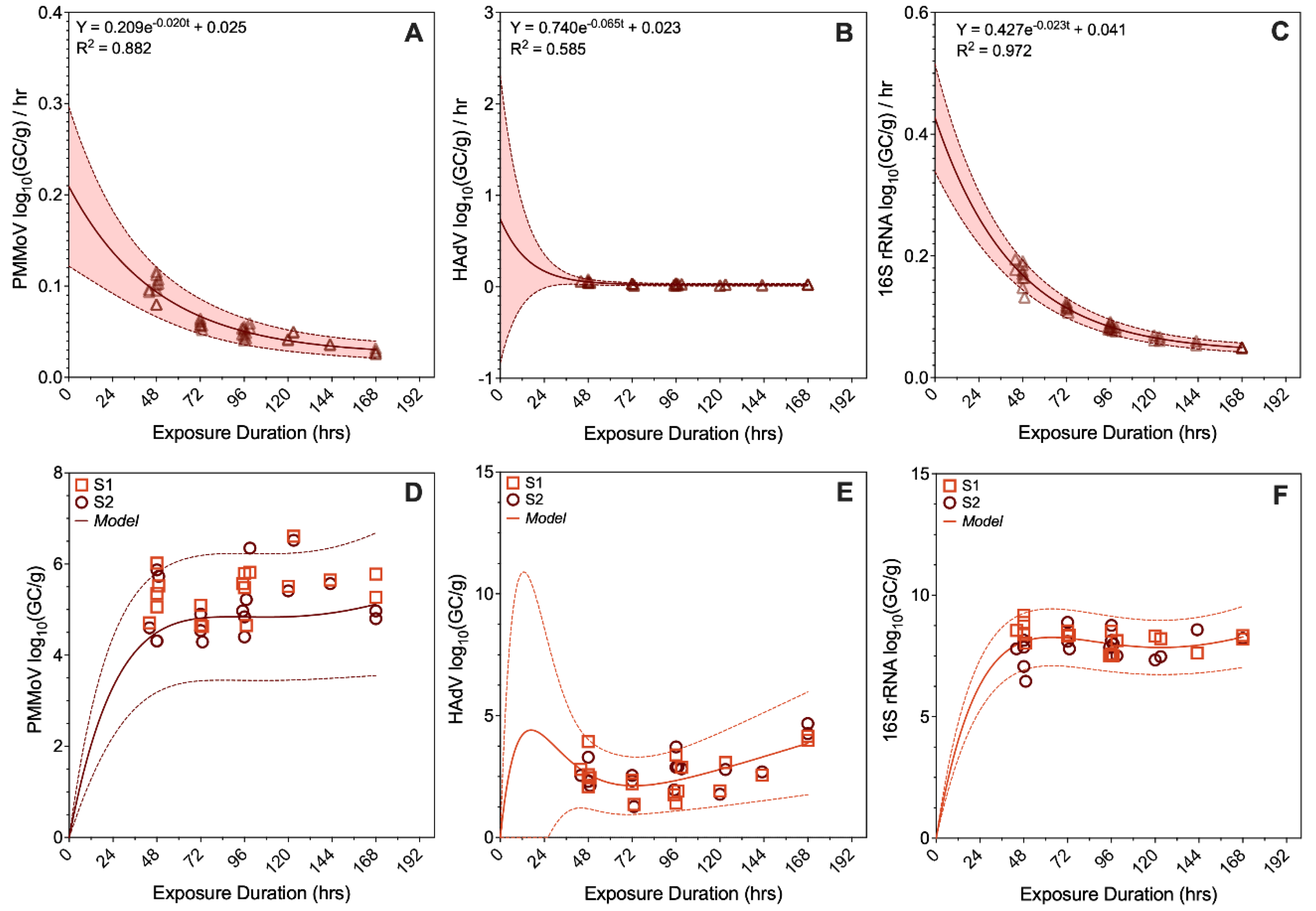

3.5. Analyte Adsorption Rate

3.6. Implications for Wastewater and Environmental Surveillance

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Daughton, C.G. Wastewater Surveillance for Population-Wide Covid-19: The Present and Future. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, A.E. Using Wastewater Surveillance Data to Support the COVID-19 Response — United States, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, B.; Duong, D.; White, B.J.; Wigginton, K.R.; Chan, E.M.G.; Wolfe, M.K.; Boehm, A.B. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) RNA in Wastewater Settled Solids Reflects RSV Clinical Positivity Rates. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2022, 9, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branda, F.; Ciccozzi, M.; Scarpa, F. Tracking the Spread of Avian Influenza A(H5N1) with Alternative Surveillance Methods: The Example of Wastewater Data. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e604–e605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, M.K.; Yu, A.T.; Duong, D.; Rane, M.S.; Hughes, B.; Chan-Herur, V.; Donnelly, M.; Chai, S.; White, B.J.; Vugia, D.J.; Boehm, A.B. Use of Wastewater for Mpox Outbreak Surveillance in California. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 570–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, C.; Crank, K.; Papp, K.; Innes, G.K.; Schmitz, B.W.; Chavez, J.; Rossi, A.; Gerrity, D. Community-Scale Wastewater Surveillance of Candida Auris during an Ongoing Outbreak in Southern Nevada. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 1755–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.L.; Gu, X.; Armas, F.; Leifels, M.; Wu, F.; Chandra, F.; Chua, F.J.D.; Syenina, A.; Chen, H.; Cheng, D.; Ooi, E.E.; Wuertz, S.; Alm, E.J.; Thompson, J. Monitoring Human Arboviral Diseases through Wastewater Surveillance: Challenges, Progress and Future Opportunities. Water Res. 2022, 223, 118904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassly, N.C.; Shaw, A.G.; Owusu, M. Global Wastewater Surveillance for Pathogens with Pandemic Potential: Opportunities and Challenges. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshaviah, A.; Diamond, M.B.; Wade, M.J.; Scarpino, S.V.; Ahmed, W.; Amman, F.; Aruna, O.; Badilla-Aguilar, A.; Bar-Or, I.; Bergthaler, A.; Bines, J.E.; Bivins, A.W.; Boehm, A.B.; Brault, J.-M.; Burnet, J.-B.; Chapman, J.R.; Chaudhuri, A.; de, R. Husman, A.M.; Delatolla, R.; Dennehy, J.J.; Diamond, M.B.; Donato, C.; Duizer, E.; Egwuenu, A.; Erster, O.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Gaggero, A.; Gilpin, D.F.; Gilpin, B.J.; Graber, T.E.; Green, C.A.; Handley, A.; Hewitt, J.; Holm, R.H.; Insam, H.; Johnson, M.C.; Johnson, R.; Jones, D.L.; Julian, T.R.; Jyothi, A.; Keshaviah, A.; Kohn, T.; Kuhn, K.G.; Rosa, G.L.; Lesenfants, M.; Manuel, D.G.; D’Aoust, P.M.; Markt, R.; McGrath, J.W.; Medema, G.; Moe, C.L.; Murni, I.K.; Naser, H.; Naughton, C.C.; Ogorzaly, L.; Oktaria, V.; Ort, C.; Karaolia, P.; Patel, E.H.; Paterson, S.; Rahman, M.; Rivera-Navarro, P.; Robinson, A.; Santa-Maria, M.C.; Scarpino, S.V.; Schmitt, H.; Smith, T.; Stadler, L.B.; Stassijns, J.; Stenico, A.; Street, R.A.; Suffredini, E.; Susswein, Z.; Trujillo, M.; Wade, M.J.; Wolfe, M.K.; Yakubu, H.; Sato, M.I.Z. Wastewater Monitoring Can Anchor Global Disease Surveillance Systems. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e976–e981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, E. Increasing the Utility of Wastewater-Based Disease Surveillance for Public Health Action: A Phase 2 Report; 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wastewater-Based Disease Surveillance for Public Health Action; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Naughton, C.C.; Roman, F.A., Jr.; Alvarado, A.G.F.; Tariqi, A.Q.; Deeming, M.A.; Kadonsky, K.F.; Bibby, K.; Bivins, A.; Medema, G.; Ahmed, W.; Katsivelis, P.; Allan, V.; Sinclair, R.; Rose, J.B. Show Us the Data: Global COVID-19 Wastewater Monitoring Efforts, Equity, and Gaps. FEMS Microbes 2023, 4, xtad003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, R.; Malema, S.; Mahlangeni, N.; Mathee, A. Wastewater Surveillance for Covid-19: An African Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.; Vikesland, P.; Pruden, A.; Krometis, L.-A.; Lee, L.M.; Darling, A.; Yancey, M.; Helmick, M.; Singh, R.; Gonzalez, R.; Meit, M.; Degen, M.; Taniuchi, M. Making Waves: The Benefits and Challenges of Responsibly Implementing Wastewater-Based Surveillance for Rural Communities. Water Res. 2024, 250, 121095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Bias, M.; Welsh, R.M.; Webb, J.; Reese, H.; Delgado, S.; Person, J.; West, R.; Shin, S.; Kirby, A. The National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS): From Inception to Widespread Coverage, 2020–2022, United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosher, J.R.; Banta, J.E.; Spencer-Hwang, R.; Naughton, C.C.; Kadonsky, K.F.; Hile, T.; Sinclair, R.G. An Environmental Equity Assessment Using a Social Vulnerability Index during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic for Siting of Wastewater-Based Epidemiology Locations in the United States. Geographies 2024, 4, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadonsky, K.F.; Naughton, C.C.; Susa, M.; Olson, R.; Singh, G.L.; Daza-Torres, M.L.; Montesinos-López, J.C.; Garcia, Y.E.; Gafurova, M.; Gushgari, A.; Cosgrove, J.; White, B.J.; Boehm, A.B.; Wolfe, M.K.; Nuño, M.; Bischel, H.N. Expansion of Wastewater-Based Disease Surveillance to Improve Health Equity in California’s Central Valley: Sequential Shifts in Case-to-Wastewater and Hospitalization-to-Wastewater Ratios. Front. Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, W.M.; Dayton, R.D.; Bivins, A.W.; Scott, R.S.; Yurochko, A.D.; Vanchiere, J.A.; Davis, T.; Arnold, C.L.; Asuncion, J.E.T.; Bhuiyan, M.A.N.; Snead, B.; Daniel, W.; Smith, D.G.; Goeders, N.E.; Kevil, C.G.; Carroll, J.; Murnane, K.S. Highly Socially Vulnerable Communities Exhibit Disproportionately Increased Viral Loads as Measured in Community Wastewater. Environ. Res. 2023, 222, 115351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.G.; Troman, C.; Akello, J.O.; O’Reilly, K.M.; Gauld, J.; Grow, S.; Grassly, N.; Steele, D.; Blazes, D.; Kumar, S. Defining a Research Agenda for Environmental Wastewater Surveillance of Pathogens. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2155–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannigama, D.L.; Amarasiri, M.; Hongsing, P.; Hurst, C.; Modchang, C.; Chadsuthi, S.; Anupong, S.; Phattharapornjaroen, P.; M, A.H.R.S.; Fernandez, S.; Huang, A.T.; Vatanaprasan, P.; Jay, D.J.; Saethang, T.; Luk-in, S.; Storer, R.J.; Ounjai, P.; Ragupathi, N.K.D.; Kanthawee, P.; Sano, D.; Furukawa, T.; Sei, K.; Leelahavanichkul, A.; Kanjanabuch, T.; Hirankarn, N.; Higgins, P.G.; Kicic, A.; Singer, A.C.; Chatsuwan, T.; Trowsdale, S.; Abe, S.; McLellan, A.D.; Ishikawa, H. COVID-19 Monitoring with Sparse Sampling of Sewered and Non-Sewered Wastewater in Urban and Rural Communities. iScience 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivins, A.; Kaya, D.; Ahmed, W.; Brown, J.; Butler, C.; Greaves, J.; Leal, R.; Maas, K.; Rao, G.; Sherchan, S.; Sills, D.; Sinclair, R.; Wheeler, R.T.; Mansfeldt, C. Passive Sampling to Scale Wastewater Surveillance of Infectious Disease: Lessons Learned from COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 835, 155347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schang, C.; Crosbie, N.D.; Nolan, M.; Poon, R.; Wang, M.; Jex, A.; John, N.; Baker, L.; Scales, P.; Schmidt, J.; Thorley, B.R.; Hill, K.; Zamyadi, A.; Tseng, C.-W.; Henry, R.; Kolotelo, P.; Langeveld, J.; Schilperoort, R.; Shi, B.; Einsiedel, S.; Thomas, M.; Black, J.; Wilson, S.; McCarthy, D.T. Passive Sampling of SARS-CoV-2 for Wastewater Surveillance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 10432–10441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, G.; Graham, K.E.; Zhu, K.J.; Rao, G.; Lindner, B.G.; Kocaman, K.; Woo, S.; D’amico, I.; Bingham, L.R.; Fischer, J.M.; Flores, C.I.; Spencer, J.W.; Yathiraj, P.; Chung, H.; Biliya, S.; Djeddar, N.; Burton, L.J.; Mascuch, S.J.; Brown, J.; Bryksin, A.; Pinto, A.; Hatt, J.K.; Konstantinidis, K.T. Parallel Deployment of Passive and Composite Samplers for Surveillance and Variant Profiling of SARS-CoV-2 in Sewage. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, G.; Zhu, K.J.; Fischer, J.M.; Flores, C.I.; Brown, J.; Pinto, A.; Hatt, J.K.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Graham, K.E. Metagenomic Evaluation of the Performance of Passive Moore Swabs for Sewage Monitoring Relative to Composite Sampling over Time Resolved Deployments. Water Res. 2024, 253, 121269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, E.K.; Stoddart, A.K.; Gagnon, G.A. Adsorption of SARS-CoV-2 onto Granular Activated Carbon (GAC) in Wastewater: Implications for Improvements in Passive Sampling. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 847, 157548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, E.K.; Gouthro, M.T.; LeBlanc, J.J.; Gagnon, G.A. Simultaneous Detection of SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, and Measles in Wastewater by Multiplex RT-qPCR. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 889, 164261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, E.K.; Gouthro, M.T.; Fuller, M.; Redden, D.J.; Gagnon, G.A. Enhanced Detection of Viruses for Improved Water Safety. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, E.K.; Sweeney, C.; Stoddart, A.K.; Gagnon, G.A. Detection of Omicron Variant in November 2021: A Retrospective Analysis through Wastewater in Halifax, Canada. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2024, 11, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrana, B.; Allan, I.J.; Greenwood, R.; Mills, G.A.; Dominiak, E.; Svensson, K.; Knutsson, J.; Morrison, G. Passive Sampling Techniques for Monitoring Pollutants in Water. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2005, 24, 845–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamati N․, E.; Law, I.; Weese, J.S.; McCarthy, D.T.; Murphy, H.M. Passive Sampling of Microbes in Various Water Sources: A Systematic Review. Water Res. 2024, 266, 122284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, E.K.; Sweeney, C.L.; Anderson, L.E.; Li, B.; Erjavec, G.B.; Gouthro, M.T.; Krkosek, W.H.; Stoddart, A.K.; Gagnon, G.A. A Novel Passive Sampling Approach for SARS-CoV-2 in Wastewater in a Canadian Province with Low Prevalence of COVID-19. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 1576–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggett, J.F.; Foy, C.A.; Benes, V.; Emslie, K.; Garson, J.A.; Haynes, R.; Hellemans, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.D.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; Vandesompele, J.; Wittwer, C.T.; Bustin, S.A. The Digital MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Digital PCR Experiments. Clin. Chem. 2013, 59, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, A.; Ebnet, C.; Harste, G.; Pring-Åkerblom, P. Rapid and Quantitative Detection of Human Adenovirus DNA by Real-Time PCR. J. Med. Virol. 2003, 70, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, E.L.; Powell, E.J.; Swift, C.; Grant, K.A.; Frost, J.A. Applicability of a Rapid Duplex Real-Time PCR Assay for Speciation of Campylobacter Jejuni and Campylobacter Coli Directly from Culture Plates. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 229, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritalahti, K.M.; Amos, B.K.; Sung, Y.; Wu, Q.; Koenigsberg, S.S.; Löffler, F.E. Quantitative PCR Targeting 16S rRNA and Reductive Dehalogenase Genes Simultaneously Monitors Multiple Dehalococcoides Strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 2765–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coster, W.; Rademakers, R. NanoPack2: Population-Scale Evaluation of Long-Read Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; Bai, Y.; Bisanz, J.E.; Bittinger, K.; Brejnrod, A.; Brislawn, C.J.; Brown, C.T.; Callahan, B.J.; Caraballo-Rodríguez, A.M.; Chase, J.; Cope, E.K.; Da Silva, R.; Diener, C.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Douglas, G.M.; Durall, D.M.; Duvallet, C.; Edwardson, C.F.; Ernst, M.; Estaki, M.; Fouquier, J.; Gauglitz, J.M.; Gibbons, S.M.; Gibson, D.L.; Gonzalez, A.; Gorlick, K.; Guo, J.; Hillmann, B.; Holmes, S.; Holste, H.; Huttenhower, C.; Huttley, G.A.; Janssen, S.; Jarmusch, A.K.; Jiang, L.; Kaehler, B.D.; Kang, K.B.; Keefe, C.R.; Keim, P.; Kelley, S.T.; Knights, D.; Koester, I.; Kosciolek, T.; Kreps, J.; Langille, M.G.I.; Lee, J.; Ley, R.; Liu, Y.-X.; Loftfield, E.; Lozupone, C.; Maher, M.; Marotz, C.; Martin, B.D.; McDonald, D.; McIver, L.J.; Melnik, A.V.; Metcalf, J.L.; Morgan, S.C.; Morton, J.T.; Naimey, A.T.; Navas-Molina, J.A.; Nothias, L.F.; Orchanian, S.B.; Pearson, T.; Peoples, S.L.; Petras, D.; Preuss, M.L.; Pruesse, E.; Rasmussen, L.B.; Rivers, A.; Robeson, M.S.; Rosenthal, P.; Segata, N.; Shaffer, M.; Shiffer, A.; Sinha, R.; Song, S.J.; Spear, J.R.; Swafford, A.D.; Thompson, L.R.; Torres, P.J.; Trinh, P.; Tripathi, A.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ul-Hasan, S.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; Vargas, F.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Vogtmann, E.; von Hippel, M.; Walters, W.; Wan, Y.; Wang, M.; Warren, J.; Weber, K.C.; Williamson, C.H.D.; Willis, A.D.; Xu, Z.Z.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Knight, R.; Caporaso, J.G. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An Ordination of the Upland Forest Communities of Southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, R.S.; Nelson, K.L.; Greenwald, H.D.; Kennedy, L.C. Challenges in Measuring the Recovery of SARS-CoV-2 from Wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 3514–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. COVID Data Tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Pruden, A.; Vikesland, P.J.; Davis, B.C.; de Roda Husman, A.M. Seizing the Moment: Now Is the Time for Integrated Global Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Wastewater Environments. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 64, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto Riquelme, M.V.; Garner, E.; Gupta, S.; Metch, J.; Zhu, N.; Blair, M.F.; Arango-Argoty, G.; Maile-Moskowitz, A.; Li, A.; Flach, C.-F.; Aga, D.S.; Nambi, I.M.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Bürgmann, H.; Zhang, T.; Pruden, A.; Vikesland, P.J. Demonstrating a Comprehensive Wastewater-Based Surveillance Approach That Differentiates Globally Sourced Resistomes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 14982–14993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, S.L.; Roguet, A. The Unexpected Habitat in Sewer Pipes for the Propagation of Microbial Communities and Their Imprint on Urban Waters. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 57, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roguet, A.; Newton, R.J.; Eren, A.M.; McLellan, S.L. Guts of the Urban Ecosystem: Microbial Ecology of Sewer Infrastructure. mSystems 2022, 7, e00118–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueholm, M.K.D.; Nierychlo, M.; Andersen, K.S.; Rudkjøbing, V.; Knutsson, S.; Albertsen, M.; Nielsen, P.H. MiDAS 4: A Global Catalogue of Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequences and Taxonomy for Studies of Bacterial Communities in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pot, B.; Gillis, M.; De LEY, J. The Genus Aquaspirillum. In The Prokaryotes: Volume 5: Proteobacteria: Alpha and Beta Subclasses; Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.-H., Stackebrandt, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röling, W.F.M. The Family Geobacteraceae. In The Prokaryotes: Deltaproteobacteria and Epsilonproteobacteria; Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E.F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., Thompson, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.H.; Mielczarek, A.T.; Kragelund, C.; Nielsen, J.L.; Saunders, A.M.; Kong, Y.; Hansen, A.A.; Vollertsen, J. A Conceptual Ecosystem Model of Microbial Communities in Enhanced Biological Phosphorus Removal Plants. Water Res. 2010, 44, 5070–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.; Pirbazari, M.; Melson, G. Biological Growth on Activated Carbon: An Investigation by Scanning Electron Microscopy. 1978. [CrossRef]

- Gibert, O.; Lefèvre, B.; Fernández, M.; Bernat, X.; Paraira, M.; Calderer, M.; Martínez-Lladó, X. Characterising Biofilm Development on Granular Activated Carbon Used for Drinking Water Production. Water Res. 2013, 47, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camper, A.K.; LeChevallier, M.W.; Broadaway, S.C.; McFeters, G.A. Bacteria Associated with Granular Activated Carbon Particles in Drinking Water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1986, 52, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhu, P.; Fan, H.; Piao, S.; Xu, L.; Sun, T. Effect of Biofilm on Passive Sampling of Dissolved Orthophosphate Using the Diffusive Gradients in Thin Films Technique. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 6836–6843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, D.; Liu, X.; Ye, Y. Utilizing Microorganisms Immobilized on Carbon-Based Materials for Environmental Remediation: A Mini Review. Water Emerg. Contam. Amp Nanoplastics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Shan, Y.; Li, F.; Shi, L. Biofilm Biology and Engineering of Geobacter and Shewanella Spp. for Energy Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbrodt, D.; Lochmatter, S.; Neu, T.R.; Holliger, C. Significance of Rhodocyclaceae for the Formation of Aerobic Granular Sludge Biofilms and Nutrient Removal from Wastewater. In IWA Biofilm Conference 2011 - Processes in Biofilms; Tongji University, 2011; pp 106–107.

- Pollock, J.; Glendinning, L.; Wisedchanwet, T.; Watson, M. The Madness of Microbiome: Attempting To Find Consensus “Best Practice” for 16S Microbiome Studies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02627–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouhy, F.; Clooney, A.G.; Stanton, C.; Claesson, M.J.; Cotter, P.D. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing of Mock Microbial Populations- Impact of DNA Extraction Method, Primer Choice and Sequencing Platform. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, J.P.; Edwards, D.J.; Harwich, M.D.; Rivera, M.C.; Fettweis, J.M.; Serrano, M.G.; Reris, R.A.; Sheth, N.U.; Huang, B.; Girerd, P.; Strauss, J.F.; Jefferson, K.K.; Buck, G.A.; Vaginal Microbiome Consortium (additional members). The Truth about Metagenomics: Quantifying and Counteracting Bias in 16S rRNA Studies. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Verhagen, R.; Ahmed, W.; Metcalfe, S.; Thai, P.K.; Kaserzon, S.L.; Smith, W.J.M.; Schang, C.; Simpson, S.L.; Thomas, K.V.; Mueller, J.F.; Mccarthy, D. In Situ Calibration of Passive Samplers for Viruses in Wastewater. ACS EST Water 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakallis, A.G.; Fallowfield, H.; Ross, K.E.; Whiley, H. Laboratory Analysis of Passive Samplers Used for Wastewater-Based Epidemiology Using F-RNA Bacteriophage MS2 as a Model Organism. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. A Comparison of Chemisorption Kinetic Models Applied to Pollutant Removal on Various Sorbents. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 1998, 76, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldowitsch, J. Über Den Mechanismus Der Katalytischen Oxidation Von CO a MnO2. URSS Acta Physiochim 1934, 1, 364–449. [Google Scholar]

- Low, M.J.D. Kinetics of Chemisorption of Gases on Solids. Chem. Rev. 1960, 60, 267–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.-C.; Tseng, R.-L.; Juang, R.-S. Characteristics of Elovich Equation Used for the Analysis of Adsorption Kinetics in Dye-Chitosan Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 150, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largitte, L.; Pasquier, R. A Review of the Kinetics Adsorption Models and Their Application to the Adsorption of Lead by an Activated Carbon. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2016, 109, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, R.-L.; Wu, F.-C.; Juang, R.-S. Liquid-Phase Adsorption of Dyes and Phenols Using Pinewood-Based Activated Carbons. Carbon 2003, 41, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajjumba, G.W.; Emik, S.; Öngen, A.; Aydın, H.K. Ö. and S.; Kajjumba, G.W.; Emik, S.; Öngen, A.; Aydın, H.K. Ö. and S. Modelling of Adsorption Kinetic Processes—Errors, Theory and Application. In Advanced Sorption Process Applications; IntechOpen, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Canzano, S.; Iovino, P.; Leone, V.; Salvestrini, S.; Capasso, S. Use and Misuse of Sorption Kinetic Data: A Common Mistake That Should Be Avoided. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2012, 30, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan-Hernandez, L.; Boehm, A. Adsorption of Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Rhinovirus, SARS-CoV-2, and F+ Bacteriophage MS2 RNA onto Wastewater Solids from Raw Wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Ellenberg, R.M.; Graham, K.E.; Wigginton, K.R. Survivability, Partitioning, and Recovery of Enveloped Viruses in Untreated Municipal Wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Voice, T.C.; Tarabara, V.V.; Xagoraraki, I. Sorption of Human Adenovirus to Wastewater Solids. J. Environ. Eng. 2018, 144, 06018008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanious, A.; Aeppli, M.; Jacak, R.; Refardt, D.; Sigstam, T.; Kohn, T.; Sander, M. Viruses at Solid-Water Interfaces: A Systematic Assessment of Interactions Driving Adsorption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.; Newcombe, G. Granular Activated Carbon: The Variation of Surface Properties with the Adsorption of Humic Substances. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1993, 159, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Mukherjee, B.; Kahler, A.M.; Zepp, R.; Molina, M. Influence of Inorganic Ions on Aggregation and Adsorption Behaviors of Human Adenovirus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11145–11153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canh, V.D.; Furumai, H.; Katayama, H. Removal of Pepper Mild Mottle Virus by Full-Scale Microfiltration and Slow Sand Filtration Plants. Npj Clean Water 2019, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, T.J.; Graham, L.L. Surface Layers of Bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1991, 55, 684–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.J.; Sharifian, G., M.; Wu, T.; Li, Y.; Chang, C.-M.; Ma, J.; Dai, H.-L. Determination of Bacterial Surface Charge Density via Saturation of Adsorbed Ions. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 2461–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, D.A. Towards a Precision Model for Environmental Public Health: Wastewater-Based Epidemiology to Assess Population-Level Exposures and Related Diseases. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2024, 11, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saingam, P.; Jain, T.; Woicik, A.; Li, B.; Candry, P.; Redcorn, R.; Wang, S.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bryan, A.; Gattuso, M.; Winkler, M.K.H. Integrating Socio-Economic Vulnerability Factors Improves Neighborhood-Scale Wastewater-Based Epidemiology for Public Health Applications. Water Res. 2024, 254, 121415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muralidharan, A.; Olson, R.; Bess, C.W.; Bischel, H.N. Equity-Centered Adaptive Sampling in Sub-Sewershed Wastewater Surveillance Using Census Data. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2024, 11, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.A.; Wade, M.J.; Barnes, K.G.; Street, R.A.; Paterson, S. Wastewater-Based Epidemiology as a Public Health Resource in Low- and Middle-Income Settings. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 351, 124045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, F.G.B.; Ban, R.; Barr, D.B.; Brown, J.; Cannon, J.; Colford, J.M., Jr.; Eisenberg, J.N.S.; Ercumen, A.; Petach, H.; Freeman, M.C.; Levy, K.; Luby, S.P.; Moe, C.; Pickering, A.J.; Sarnat, J.A.; Stewart, J.; Thomas, E.; Taniuchi, M.; Clasen, T. Measuring Environmental Exposure to Enteric Pathogens in Low-Income Settings: Review and Recommendations of an Interdisciplinary Working Group. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 11673–11691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).