Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

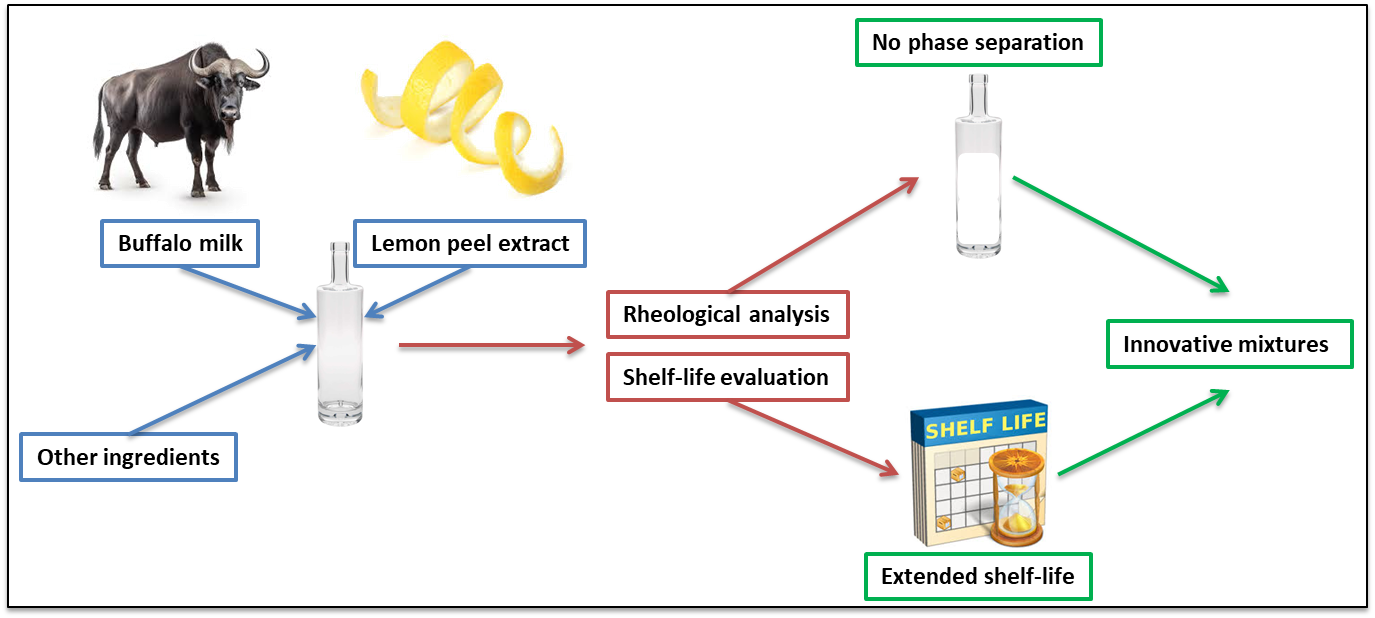

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Pectin Extraction

2.2. Formulation Development

2.3. Rheological and Shelf-life Testing

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.5. Sensory Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pectin Extraction Yield

3.2. Rheological Properties and Formulation Optimization

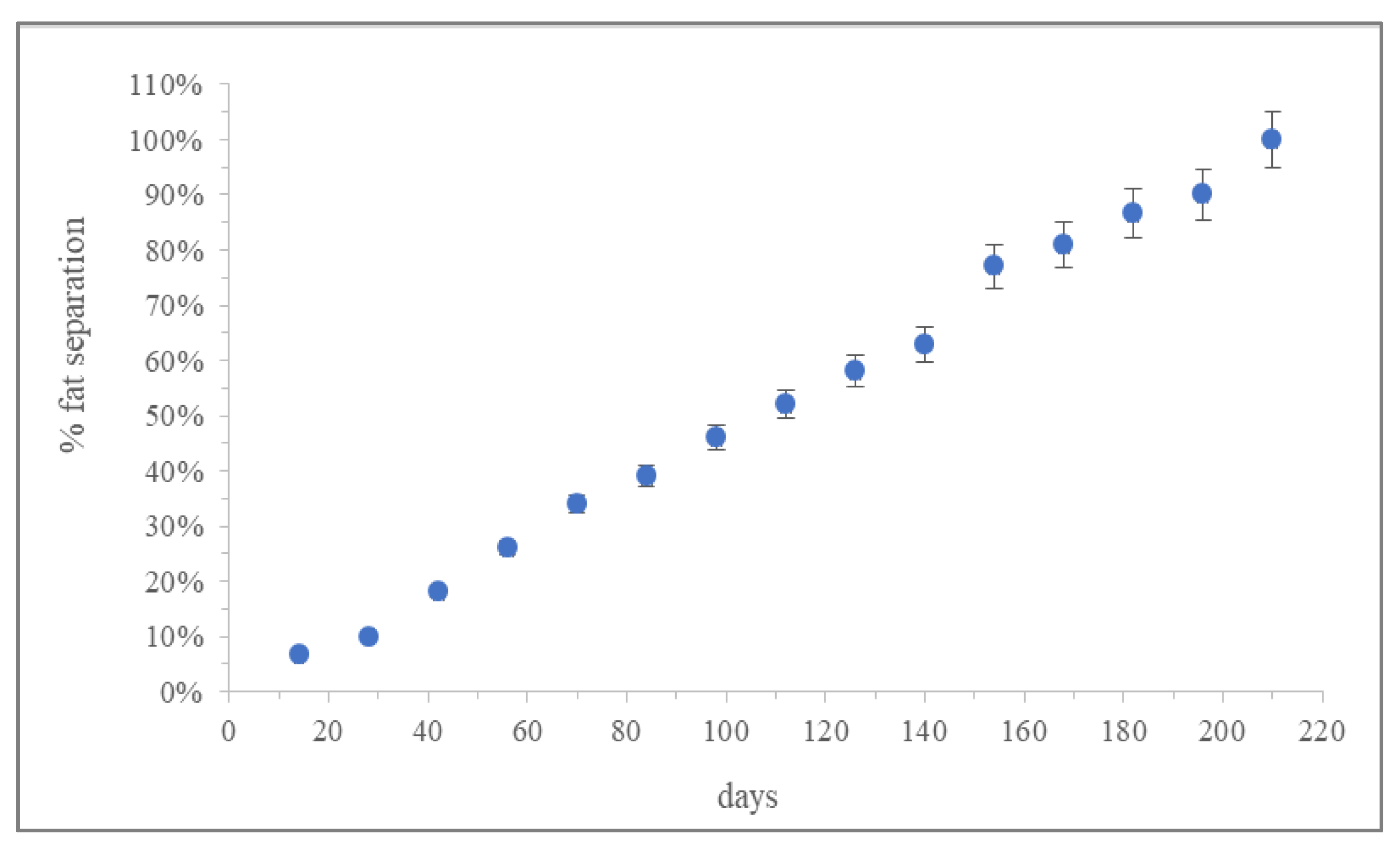

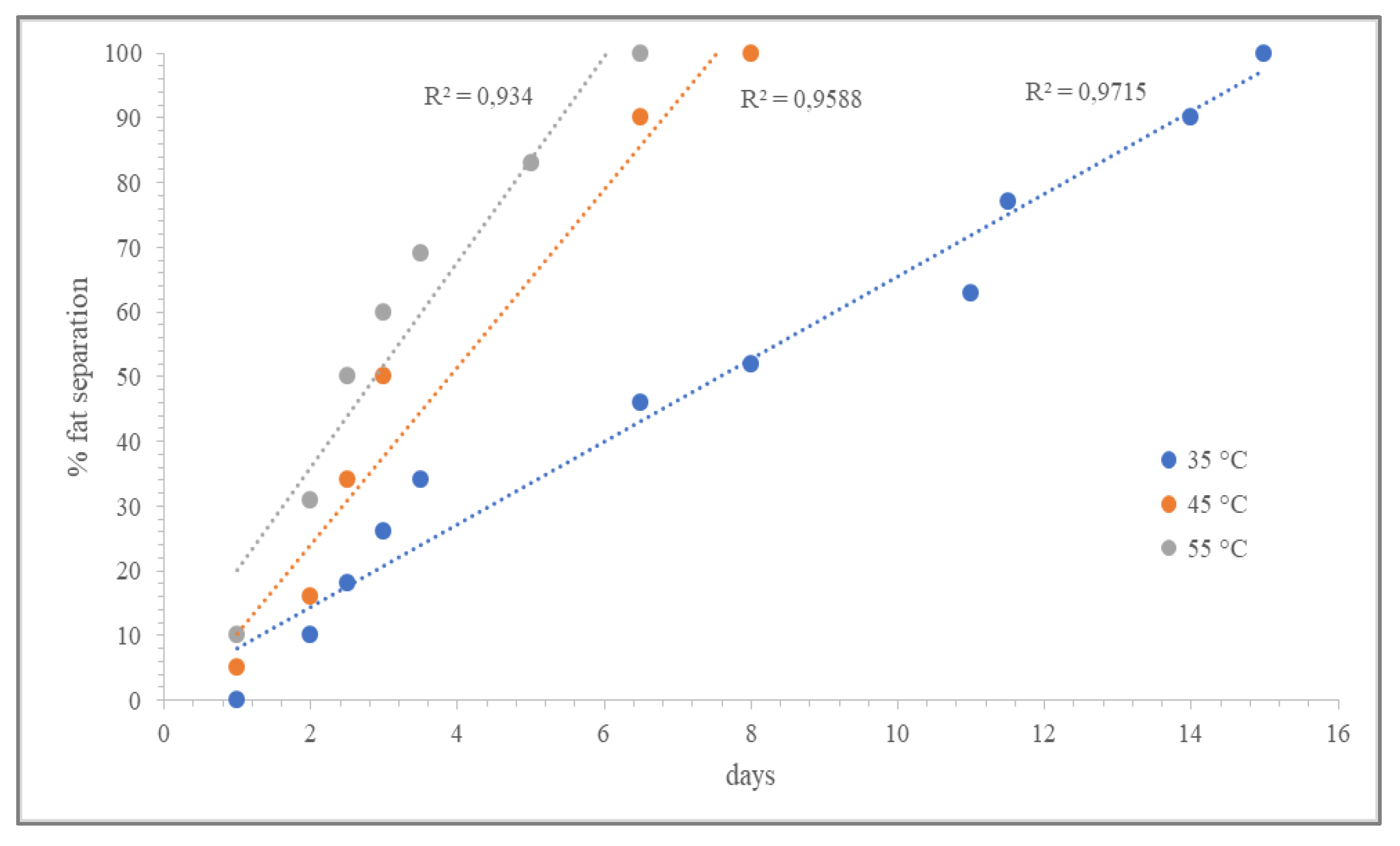

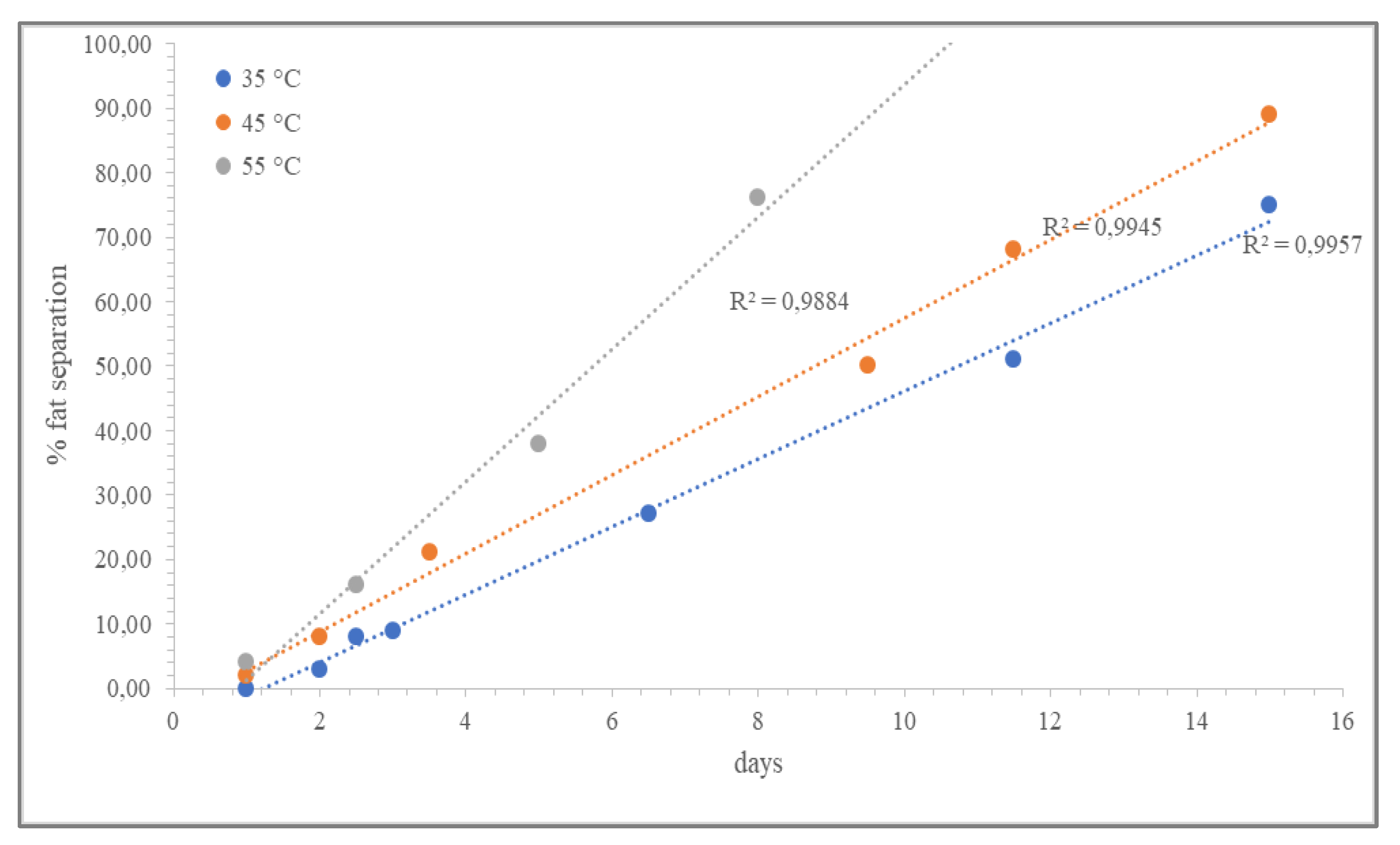

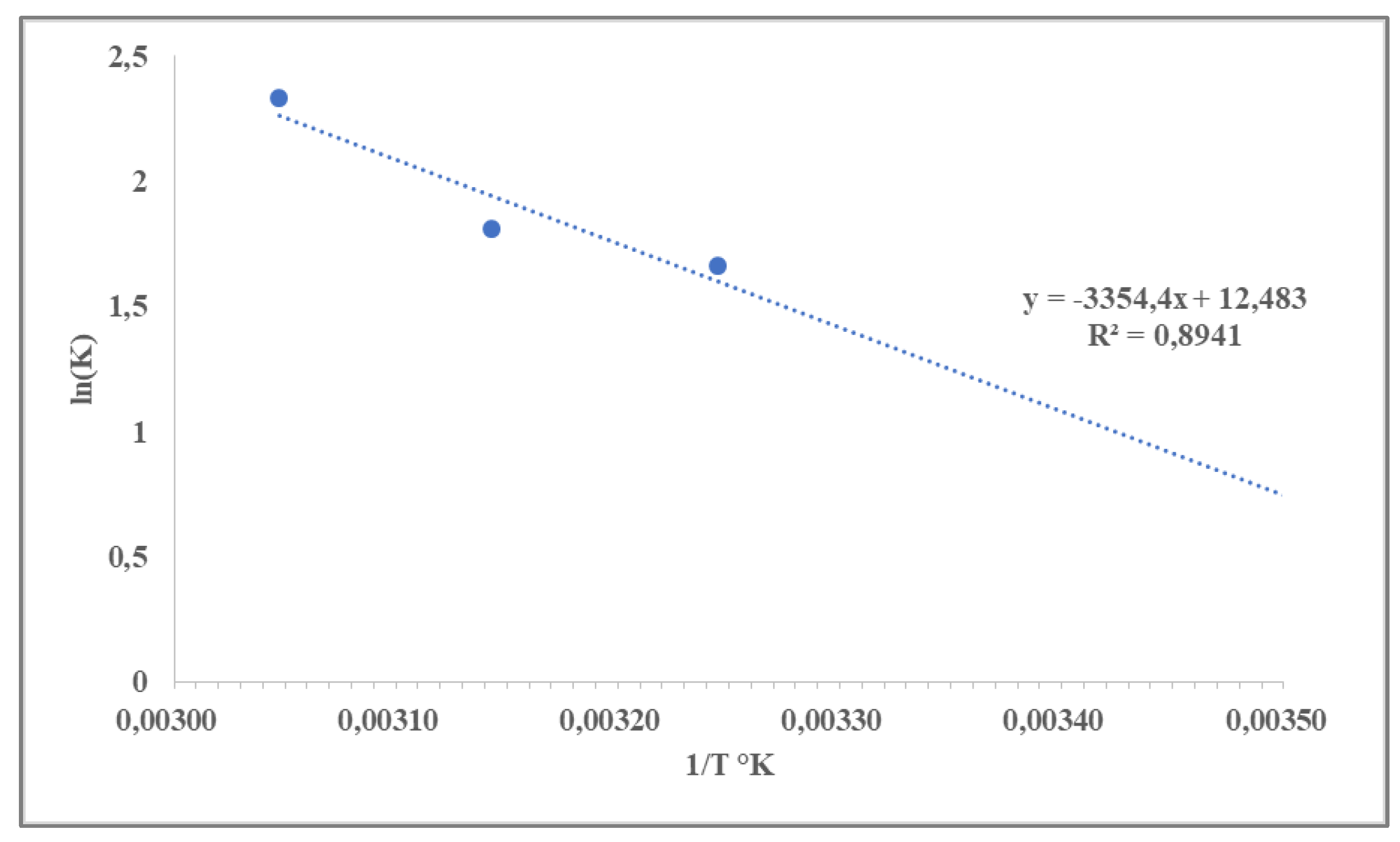

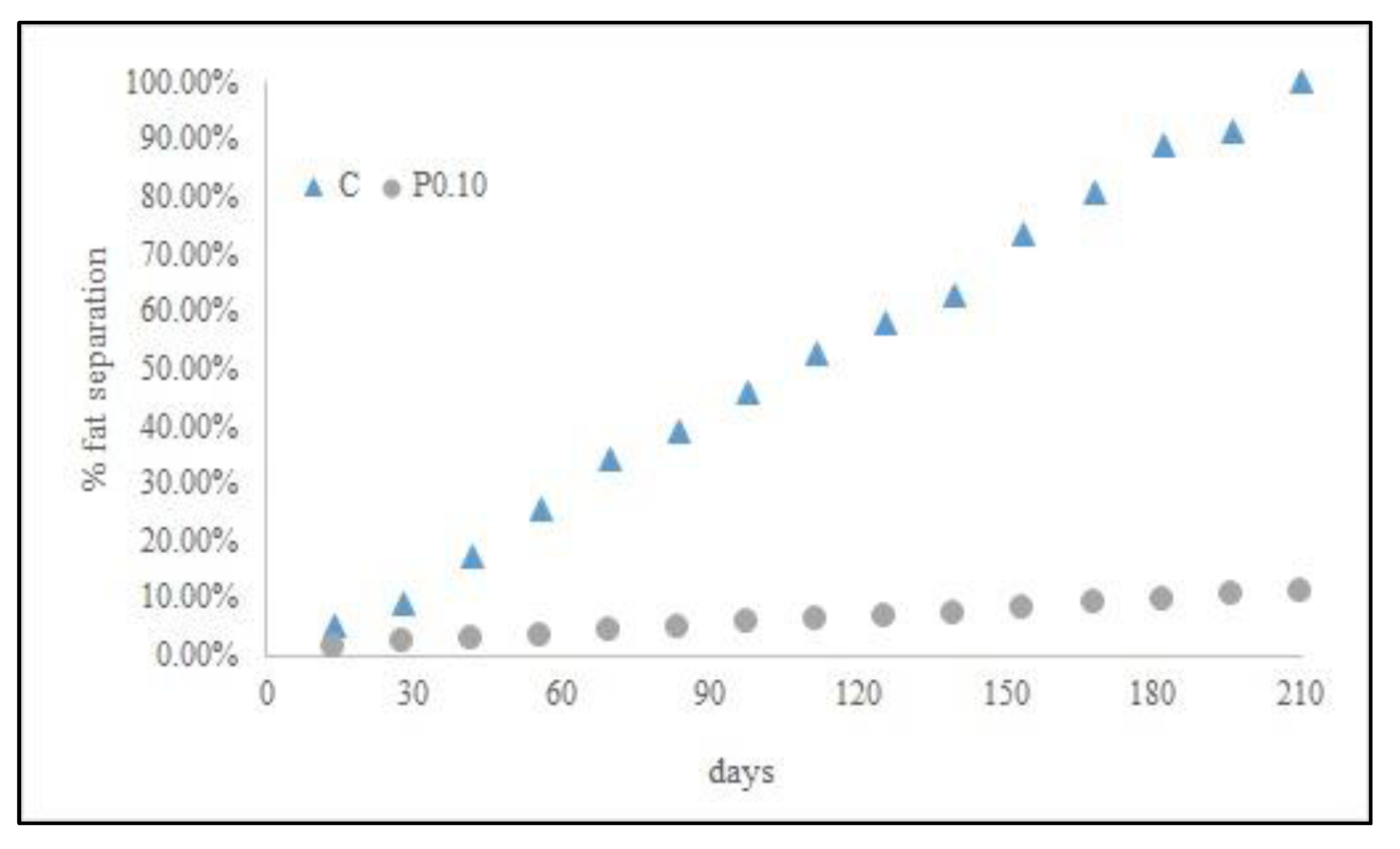

3.3. Shelf-Life Predictions

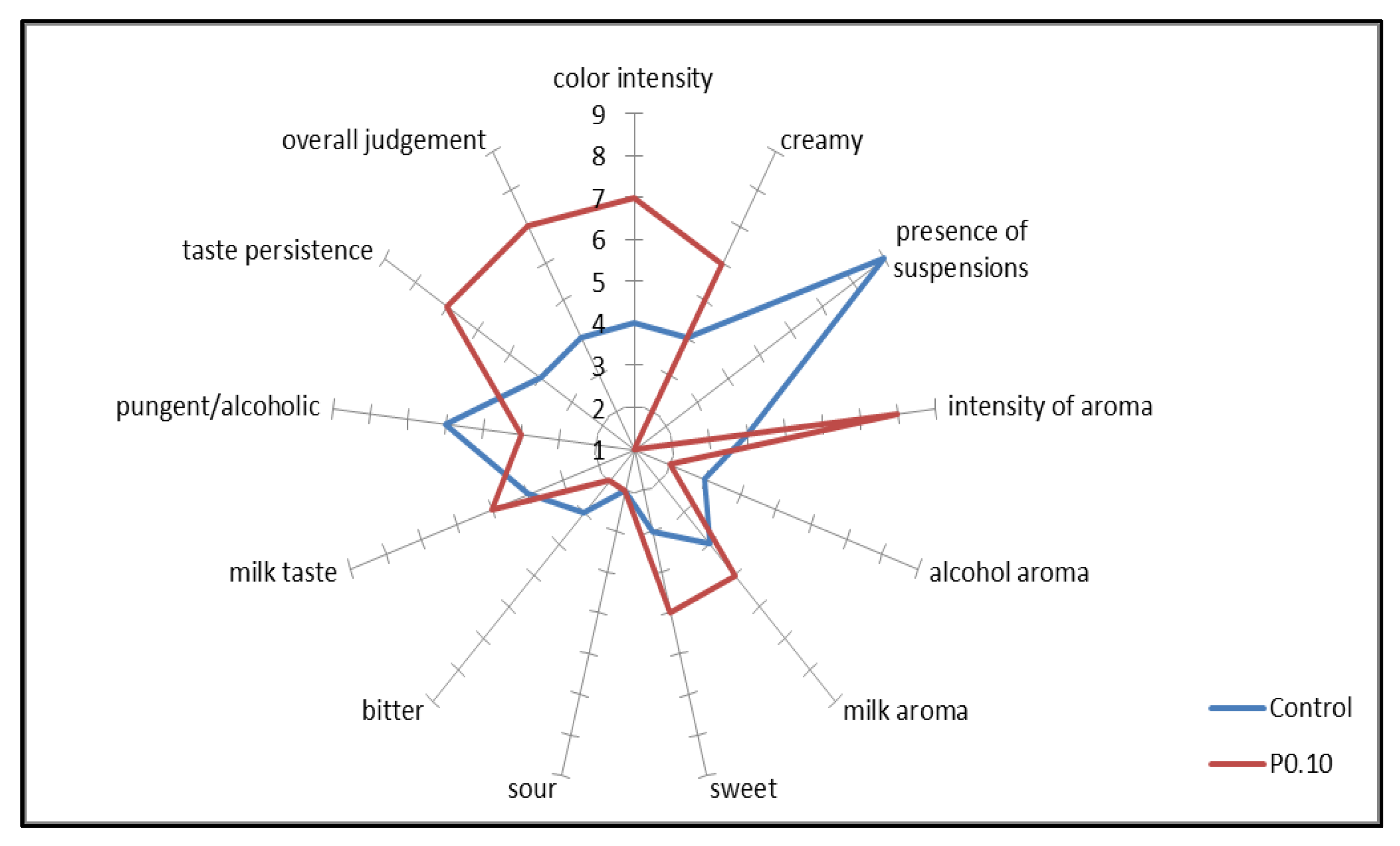

3.4. Sensory Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Current Formulation

4.2. Future Perspective

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Banks, W.; Muir, D.D. Effect of alcohol content on emulsion stability of cream liqueurs. Food Chem. 1985, 18(2), 139-152. [CrossRef]

- Mc Clements, D.J. Food Emulsions: Principles, Practices, and Techniques, Second Edition (2nd ed.). CRC Press. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Rai, D.; Popovic, T.; Jancic, D., Šukovic, D.; Pajovic-Šcepanovic, R. The Impact of Type of Brandy on the Volatile Aroma Compounds and Sensory Properties of Grape Brandy in Montenegro. Mol. 2022, 27, 2974. [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019: Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2019. ISBN 978-92-5-131789-1.

- Laurent, M.A.; Boulenguer, P. Stabilization mechanism of acid dairy drinks (ADD) induced by pectin. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17(4), 445-454. [CrossRef]

- Chandel, V.; Biswas, D.; Roy, S.; Vaidya, D.; Verma, A.; Gupta, A. Current advancements in pectin: extraction, properties and multifunctional applications. Foods, 2022, 11(17), 2683. [CrossRef]

- Voragen, A. G. J.; Coenen, G.J.; Verhoef, R. P.; Schols, H. A. Pectin, a versatile polysaccharide present in plant cell walls. Structural Chemistry, 2009, 20, 263-275. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.M.; Li, T.; Liang, R.H.; Luo, S.J. Pectin modifications: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55(12), 1684-1698. [CrossRef]

- Ropartz, D.; Ralet, M.C. Pectin structure. Pectin: Technological and physiological properties 2020, 17-36. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, K.; Chen, K.; Deng, P.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, F.; Li, C. Improved stability and mechanical properties of citrus pectin-zein emulsion gels by double crosslinking with calcium and transglutaminase. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 211, 118305. [CrossRef]

- Said, N.S.; Olawuyi, I.F.; Lee, W.Y. Pectin hydrogels: Gel-forming behaviors, mechanisms, and food applications. Gel 2023, 9(9), 732. [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.I.; Luo, Y. Casein and pectin: Structures, interactions, and applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 97, 391-403. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, B. R.; Singh, R. K.; Handa, A. K.; Rao, M. A. Chemistry and uses of pectin-a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition, 1997, 37(1), 47-73. [CrossRef]

- Einhorn-Stoll, U.; Benthin, A.; Zimathies, A.; Görke, O.; Drusch, S. Pectin-water interactions: Comparison of different analytical methods and influence of storage. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 577-583. [CrossRef]

- Einhorn-Stoll, U. Pectin-water interactions in foods from powder to gel. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 78, 109-119. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Espinoza, C.; Carvajal-Millán, E.; Balandrán-Quintana, R.; López-Franco, Y.; Rascón-Chu, A. Pectin and pectin-based composite materials: Beyond food texture. Mol. 2018, 23(4), 942. [CrossRef]

- Naseri, A.T.; Thibault, J.F.; Ralet-Renard, M.C. Citrus pectin: Structure and application in acid dairy drinks. Tree and Forestry Science and Biotechnology 2008, 2 https://hal.science/hal-01602038v1.

- Canteri-Schemin, M.H.; Fertonani, H.C.R.; Waszczynskyj, N.; Wosiacki, G. Extraction of pectin from apple pomace. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2005, 48(2), 259-266. [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, Z.; Khalid, W.; Atiq, H.T.; Koraqi, H.; Javaid. Z.; Alhag, S.K.; Al-Shuraym, L.A.; Bader, D.M.D.; Almarzuq, M.; Afifi, M.; AL-Farga, A. Citrus waste as source of bioactive compounds: extraction and utilization in health and food industry. Mol. 2023, 28(4), 1636. [CrossRef]

- Vilela, A.; Cosme, F.; Pinto, T. Emulsions, foams, and suspensions: The microscience of the beverage industry. Bev., 2018, 4(2), 25. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.M.P.; Coimbra, J.S.R.: Souza, V.G.L.; Sousa, R.C.S. Structure and applications of pectin in food, biomedical, and pharmaceutical industry: A review. Coatings. 2021, 11(8), 922. [CrossRef]

- Vanitha, T.; Khan, M. Role of pectin in food processing and food packaging. Pectins-extraction, purification, characterization and applications. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Hulle, N.R.S. Citrus pectins: Structural properties, extraction methods, modifications and applications in food systems–A review. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2(2), 100215. [CrossRef]

- Tárrega, A.; Durán, L.; Costell, E. Rheological characterization of semisolid dairy desserts. Effect of temperature. Food Hydrocoll. 2005, 19(1), 133-139. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Chauhan, S.K.; Shinde, G.; Subramanian, V.; Nadanasabapathi, S. Whey Proteins: A potential ingredient for food industry-A review. Asian J. Dairy Res. 2018, 37(4), 283-290. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Ma, C.; Cui, F.; McClements, D.J.; Liu, X.; Liu, F. Protein-stabilized Pickering emulsions: Formation, stability, properties, and applications in foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 103, 293-303. [CrossRef]

- Mc Clements, D.J.; Bai, L.; Chung, C. Recent advances in the utilization of natural emulsifiers to form and stabilize emulsions. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 8(1), 205-236. [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Wang, Y.; Selomulya, C. Dairy and plant proteins as natural food emulsifiers. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 261-272. [CrossRef]

- Erxleben, S.W.; Pelan, E.; Wolf, B. Effect of the interplay between lipid phase properties and ethanol concentration on the stability of model cream liqueurs. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 685, 133233. [CrossRef]

- Dalgleish, D.G. Food Emulsions: Their Structures and Properties 2004. ISBN 0-8247-4696-1.

- Walstra, P. Dairy technology: principles of milk properties and processes. CRC Press, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Horne, D.S. A balanced view of casein interactions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 28, 74-86. [CrossRef]

- Smialowska, A.; Matia-Merino, L.; Ingham, B.; Carr, A. J. Effect of calcium on the aggregation behaviour of caseinates. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 522, 113-123. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, U.; Gill, H.; Chandrapala, J. Casein micelles as an emerging delivery system for bioactive food components. Foods 2021, 10(8), 1965. [CrossRef]

- Dalgleish, D.G.; Corredig, M. The structure of the casein micelle of milk and its changes during processing. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 3(1), 449-467. [CrossRef]

- Ozcan-Yilsay, T.Ü.L.A.Y.; Lee, W.J.; Horne, D.; Lucey, J.A. Effect of trisodium citrate on rheological and physical properties and microstructure of yogurt. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90(4), 1644-1652. [CrossRef]

- Buňka, F.; Salek, R.N.; Kůrová, V.; Buňková, L.; Lorencová, E. The impact of phosphate-and citrate-based emulsifying salts on processed cheese techno-functional properties: A review. Int. Dairy J. 2024, 106031. [CrossRef]

- Murray, B.S.; Ettelaie, R.; Sarkar, A.; Mackie, A.R.; Dickinson, E. The perfect hydrocolloid stabilizer: Imagination versus reality. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 117, 106696. [CrossRef]

- Bayés-García, L.; Patel, A.R.; Dewettinck, K.; Rousseau, D.; Sato, K.; Ueno, S. Lipid crystallization kinetics-roles of external factors influencing functionality of end products. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 4, 32-38. [CrossRef]

- Hondoh, H.; Ueno, S., Sato, K. Fundamental aspects of crystallization of lipids. Crystallization of lipids: Fundamentals and applications in food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals 2018, 105-141. [CrossRef]

- Given, P.S. Encapsulation of flavors in emulsions for beverages. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 14, 43–47. [CrossRef]

- Todaro, A.; Peluso, O.; Catalano, A.E.; Mauromicale, G.; Spagna, G. Polyphenol Oxidase activity from three sicilian artichoke (Cynara cardunculus L. var. scolymus L. (Fiori)) cultivars: studies and technological application on minimally processed production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 1714-1718. [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [CrossRef]

- ISO 13299:2016; Sensory Analysis – Methodology - General Guidance for establishing a sensory profile. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/58042.html.

- ISO 3972:2011; Sensory analysis – Methodology– Method of investigating sensitivity of taste. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/50110.html.

- Hundie, K.B.; Abdissa, D. Extraction and characterization of pectin from lemon waste for commercial applications. J. Turk. Chem. Soc. A: Chem. 2021, 8(4), 1111-1120. [CrossRef]

- Twinomuhwezi, H.; Godswill, A.C.; Kahunde, D. Extraction and characterization of pectin from orange (Citrus sinensis), lemon (Citrus limon) and tangerine (Citrus tangerina). Am. J. Phys. 2023, 1(1), 17-30. [CrossRef]

- Smiddy, M.A.; Kelly, A.L.; Huppertz, T. Cream and related products. Dairy fats and related products, 2009. pp.61-85. [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, S.P.; Kelly, A.L.; Mulvihill, D.M. High-pressure-homogenised cream liqueurs: Emulsification and stabilization efficiency. Journal of Food Engineering, 2009, 95(3), 525-531. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Torres, L.; Calderas, F.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Rocha-Guzmán, N. Stability of alcoholic emulsions containing different caseinates as a function of temperature and storage time. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 352(1-3), 38-46. [CrossRef]

- Masuelli, M.A. Viscometric study of pectin. Effect of temperature on the hydrodynamic properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 48(2), 286-291. [CrossRef]

- Banks, W.; Muir, D.D.; Wilson, A.G. Formulation of cream-based liqueurs: a comparison of sucrose and sorbitol as the carbohydrate component. J. Dairy Technol. 1982, 35, 41–43. [CrossRef]

- Naseri, A.T.; Thibault, J.F.; Ralet-Renard, M.C. Citrus pectin: Structure and application in acid dairy drinks. Tree and Forestry Science and Biotechnology 2008, 2(1), 60-70. https://hal.science/hal-01602038v1.

- Power, P.C. The formulation, testing and stability of 16% fat cream liqueurs. 1996. https://hdl.handle.net/10468/1628.

- O’Sullivan, M.G. Principles of sensory shelf-life evaluation and its application to alcoholic beverages. In Alcoholic Beverages 2012, 42-65. [CrossRef]

- Weinbreck, F.; De Vries, R.; Schrooyen, P.; De Kruif, C.G. Complex coacervation of whey proteins and gum arabic. Biomacromolecules, 2003, 4(2), 293-303. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Hydrocolloids at interfaces and the influence on the properties of dispersed systems. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17(1), 25-39. [CrossRef]

- Celus, M.; Kyomugasho, C.; Van Loey, A.M.; Grauwet, T.; Hendrickx, M.E. Influence of pectin structural properties on interactions with divalent cations and its associated functionalities. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17(6), 1576-1594. [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, S.P.; Kelly, A.L.; Mulvihill, D.M.; Uwe, L.; Schuchmann, H.P. Efficiency of a range of homogenization technologies in the emulsification and stabilization of cream liqueurs. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 12, 628-634. [CrossRef]

- Fabroni, S.; Amenta, M.; Timpanaro, N.; Todaro, A.; Rapisarda, P.; Change in Taste-altering Non-volatile Components of Blood and Common Orange Fruit during Cold Storage. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 108916. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, S.; Wagner, G.; Urban, K.; Ulrich, J. High-pressure homogenization as a process for emulsion formation. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2004, 27(4), 361-368. [CrossRef]

- Vaucher, A.C.D.S.; Dias, P.C.; Coimbra, P.T.; Costa, I.D.S.M.; Marreto, R.N.; Dellamora-Ortiz, G.M.; De Freitas, O.; Ramos, M.F. Microencapsulation of fish oil by casein-pectin complexes and gum arabic microparticles: oxidative stabilisation. J. Microencapsul. 2019, 36(5), 459-473. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Gao, W.; Tian, G.; Zhao, C.; Di Marco-Crook, C.; Fan, B.; Li, C.; Xiao, H.; Lian, Y.; Zheng, J. Citrus oil emulsions stabilized by citrus pectin: The influence mechanism of citrus variety and acid treatment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66(49), 12978-12988. [CrossRef]

- Ekene, U.S.; Okey, O.E. Studies on the Production of Cream Liqueur Using Whiskey and Milk Cream. SAR J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2022, 3(5), 73-80. [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.G.; Decker, E.A.; Mc Clements, D.J. Formation of biopolymer particles by thermal treatment of lactoglobulin–pectin complexes. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 1312–1321. [CrossRef]

- Ibanoglu, E. Effect of hydrocolloids on the thermal denaturation of proteins. Food Chem. 2005, 90(4), 621-626. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.M.; Ganje, M.; Dehnad, D.; Ghanbari, V.; Hajitabar, J. Arrhenius equation modeling for the shelf life prediction of tomato paste containing a natural preservative. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97(15), 5216-5222. [CrossRef]

- Nurhayati, R.; NH, E.R.; Susanto, A.; Khasanah, Y. Shelf-life prediction for canned gudeg using accelerated shelf life testing (ASLT) based on Arrhenius method. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2017, 193(1), 012025). IOP Publishing.

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, X.; Jin, H.; Feng, X.; Tian, F.; Song, Y.; Ren, Y.; Man, C.; Zhang, W. Shelf-life prediction and chemical characteristics analysis of milk formula during storage. LWT, 2021, 144, 111268. [CrossRef]

- Aniya, M.; Shinkawa, T. A model for the fragility of metallic glass forming liquids. Material Transactions. 2007, 48(7), 1793-1796. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, M.; Aniya, M. Bond Strength-Coordination Number Fluctuation Model of Viscosity: An Alternative Model for the Vogel-Fulcher-Tammann Equationand an Application to Bulk Metallic Glass Forming Liquids. Materials 2010, 3(12), 5246-5262. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.L. Temperature-dependence of the hydrophobic interaction in protein folding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. (1986) 8069. [CrossRef]

- Masuelli, M.A. Mark-Houwink parameters for aqueous soluble polymers and biopolymers at various temperatures. J. Polym. Sci. 2014, 6, 13-25. http://www.sciepub.com/reference/256766.

- Kar, F.; Arslan, N. Effect of temperature and concentration on viscosity of orange peel pectin solutions and intrinsic viscosity–molecular weight relationship. Carbohydrate Polymers. 1999, 40, 277-284. [CrossRef]

- Horne, D.S. Ethanol stability and milk composition. In McSweeney PLH and O’Mahony JA (eds), Advanced Dairy Chemistry. Vol 1B: Proteins: Applied Aspects. New York, USA: Springer, 2016, pp. 225–246.

- Ibáñez, R.A.; Vyhmeister, S.; Muñoz, M.F.; Brossard, N.; Osorio, F.; Salazar, F.N., Fellenberg, M.A.; Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E. Influence of milk pH on the chemical, physical and sensory properties of a milk-based alcoholic beverage. J. Dairy Res. 2019, 86(2), 248-251. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.; Petkova, N.; Todorova, M.; Dobreva, V.; Vlaseva, R.; Denev, P.; Hadjikinov, D.; Bouvard, V. Influence of citrus and celery pectins on physicochemical and sensory characteristics of fermented dairy products. Scientific Study & Research. Chemistry & Chemical Engineering, Biotechnology, Food Industry 2020, 21(4), 533-545..

- Shuai, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; Dong, H.; Dai, T.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, R. The effects of pectin structure on emulsifying, rheological, and in vitro digestion properties of emulsion. Foods 2022, 11, 3444. [CrossRef]

- Wiacek, A.; Chibowski, E. Stability of oil/water (ethanol, lysozyme or lysine) emulsions. Colloids Surf. B-Bioiinterfaces 2000, 17, 175–190. [CrossRef]

- Wiacek, A.E.; Chibowski, E.; Wilk, K. Studies of oil-in-water emulsion stability in the presence of new dicephalic saccharidederived surfactants. Colloids Surf. B-Biointerfaces 2002, 25, 243–256. [CrossRef]

| Ingredients 1 | C | P0.05 | P0.10 | P0.15 | P0.20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffalo milk | 45.00 | 45.00 | 45.00 | 45.00 | 45.00 |

| Water | 17.40 | 17.40 | 17.40 | 17.40 | 17.40 |

| Sugar | 17.00 | 17.00 | 17.00 | 17.00 | 17.00 |

| Brandy | 16.00 | 16.00 | 16.00 | 16.00 | 16.00 |

| Glucose sirup | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Maltodextrins | 1.66 | 1.61 | 1.56 | 1.51 | 1.46 |

| Pectin | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| Caseinate | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Sodium citrate | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Sample | Viscosity (mPA*s) ± SD |

|---|---|

| C | 79.3±3.2b1 |

| P0.05 | 68.5±2.7c |

| P0.10 | 81.1±3.6b |

| P0.15 | 92.9±5.1a |

| P0.20 | 94.7±5.5a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).