4.1. Result of data preprocessing

a. Annotation refinement

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Chest X-ray dataset, containing abnormality labels and classifications, was obtained from Kaggle. This dataset, while providing valuable image data, required careful pre-processing, particularly in terms of annotation refinement, to ensure the quality and consistency necessary for training a robust segmentation model. Our research focused on eight specific disease categories: consolidation, effusion, fibrosis, pneumonia, pneumothorax, nodule, no finding, and clinically relevant co-occurrences such as fibrosis combined with pneumothorax and atelectasis with infiltration. The dataset comprised a total of 1,061 images, with a notable class imbalance. The number of samples per disease category ranged from relatively frequent findings, such as "no finding" (200 samples), to rare co-occurrences, like fibrosis combined with pneumothorax (23 samples). This class imbalance presented a challenge for model training, as models can be biased towards more frequent classes.

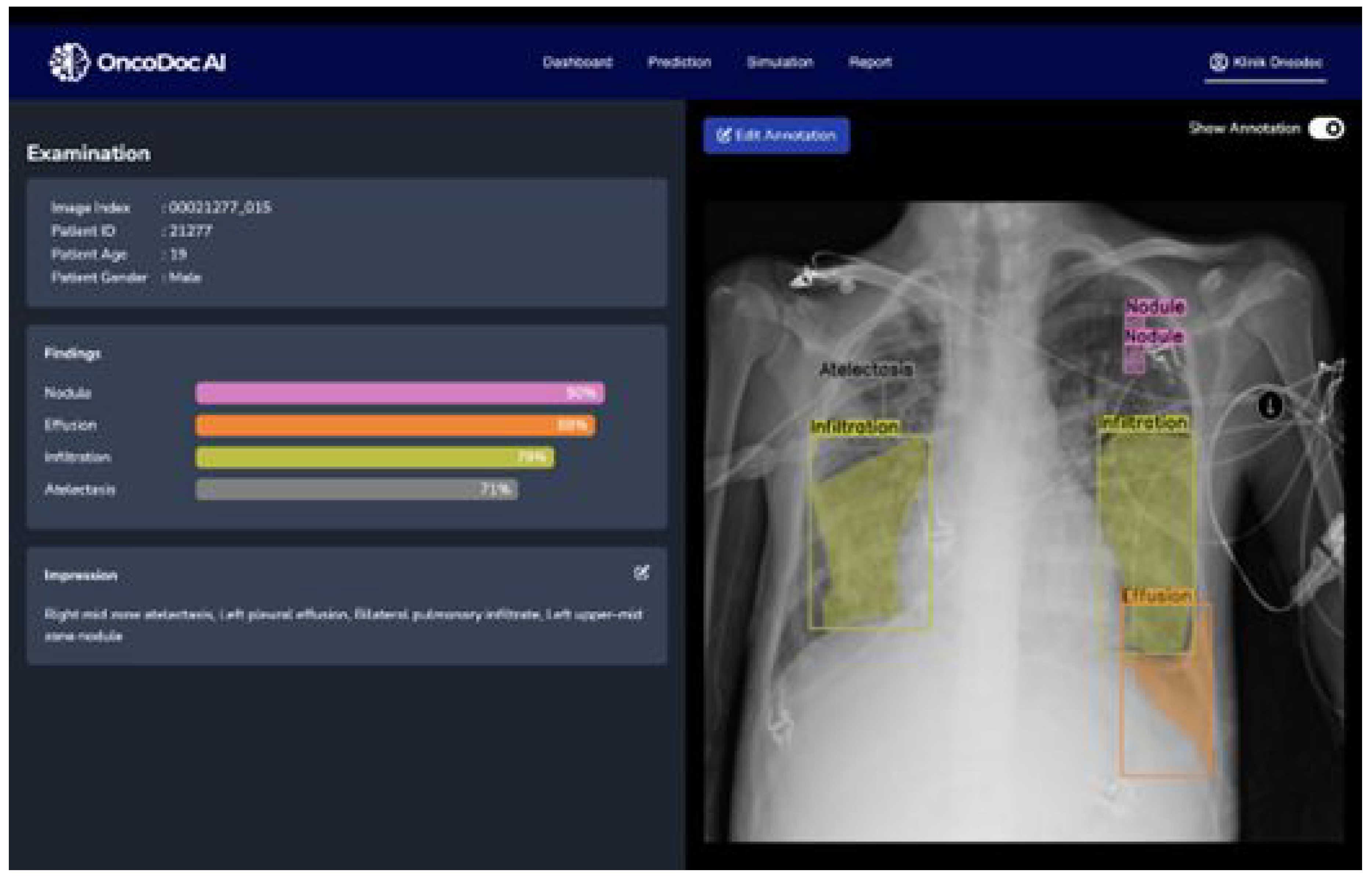

The original image-level labels provided with the NIH dataset were used as a starting point. However, given the potential for inaccuracies and inconsistencies in automatically generated labels, a rigorous annotation refinement process was implemented. Expert radiologists performed the semantic segmentation annotation, delineating regions of interest for each identified pathology. These regions were defined by coordinate points specifying the boundaries of the multi-label segmentation areas. To ensure consistency and accuracy, a second layer of validation was implemented. A different radiologist, blinded to the first radiologist’s annotations, independently reviewed and validated the annotated regions of interest using the OncodocAI application (ai.oncodoc.id). This double-reading approach, a standard practice in radiology, helped to minimize inter-observer variability and improve the overall quality of the annotations. Furthermore, in close collaboration with tuberculosis specialists acting as expert annotators, the annotations were iteratively refined using the segmentation correction interface within the OncoDocAI application (

Figure 2).

To clarify the annotation procedure, each abnormality within an image is counted individually. For example, if a CXR image contains two nodules, they are recorded as two separate abnormalities. Similarly, if the same image includes two nodules and one abnormality, it is counted as three distinct abnormalities in total. The final annotated dataset was split into training and validation subsets for semantic segmentation tasks. This annotation refinement process ensured high-quality segmentation maps that form the foundation for effective training and evaluation of the semantic segmentation model. Data distribution of training and validation samples per disease category after annotation refinement shown in

Table 2.

The final annotated dataset underwent image multiplications as part of the augmentation strategy, which aimed to balance the class distributions by increasing the representation of underrepresented categories. This augmentation process involved multiplying the existing images in each folder to expand the dataset size and enhance the model’s generalization capability. The detailed results are presented in

Table 3. Column X represents the multiplication factor applied to the original images to generate augmented files.

Following the image augmentation process, meticulous attention was given to updating the corresponding label annotations for the newly generated training data.

Table 4 presents a comprehensive overview of the number of abnormality labels in the training dataset before and after augmentation. The

Table 4 clearly distinguishes between the original label counts, the counts after basic augmentation (Aug), and the counts after mixed augmentation (Mix Aug). This detailed breakdown allows for a direct comparison of the impact of each augmentation strategy on the label distribution.

For example, in Folder 0 (representing "Consolidation"), the original dataset contained 140 images. These images were multiplied by a factor of 2, resulting in 280 augmented images. Therefore, the final number of images in Folder 0 became 420, comprising 140 original images and 280 augmented images. This process was repeated for all categories to ensure a balanced dataset for the training phase.

As can be seen, the augmentation and annotation process significantly increased the number of labeled abnormalities, effectively enhancing both the size and, more importantly, the diversity of the dataset. This increase in labeled abnormalities contributes to a more balanced representation of the different pathological conditions, mitigating the challenges posed by the inherent class imbalance in the original dataset. A more balanced dataset, coupled with the increased diversity introduced by the augmentations, supports more robust and generalizable training of the semantic segmentation model, leading to improved performance on unseen data. The augmented dataset provides the model with a richer set of examples, enabling it to learn more discriminative features and better handle the variations present in real-world clinical data.

After augmenting and annotating the training data to improve class balance and representation, the validation dataset remained unchanged to provide a consistent baseline for evaluating the model’s generalization capabilities.

Table 5 presents the distribution of label annotations in the validation dataset, which is also used as the testing dataset. The validation dataset comprises a total of 220 labelled abnormalities across nine thoracic conditions, providing a comprehensive benchmark for evaluating the performance of the semantic segmentation model.

b. Image Resizing

All images in the dataset were resized to a uniform dimension of 800×800 pixels prior to training. This specific size was chosen as a compromise between preserving sufficient image detail for accurate segmentation and maintaining computational efficiency [

38,

43]. Larger input sizes can capture finer details but increase computational demands, while smaller sizes reduce computational load but may lose important diagnostic information.

The 800x800 pixel dimension was empirically determined to provide a suitable balance for chest Xray analysis. This resizing step is essential for batch processing during model training, as deep learning models typically require input images of consistent dimensions. It also contributes to more stable and efficient training by ensuring that all images contribute equally to the gradient calculations during backpropagation.

c. Intensity Normalization

To standardize input features and facilitate efficient model convergence, pixel values were normalized to a 0–1 scale [

43,

44]. This normalization process involved scaling the pixel intensities to this specific range, ensuring consistency across all images in the dataset. Normalizing pixel values addresses variations in image brightness and contrast that can arise from differences in X-ray exposure settings, imaging equipment, and patient-specific factors

By providing the model with inputs that have uniform dynamic ranges, normalization prevents these variations from unduly influencing the learning process. This standardization allows the model to focus on learning the underlying pathological features rather than being sensitive to variations in image acquisition parameters. Furthermore, normalizing pixel values to a 0-1 range is a common practice in deep learning as it can improve the numerical stability of the training process and prevent issues such as vanishing or exploding gradients.

d. Comparison of NIH Labels and Expert Annotations

A crucial component of the pre-processing pipeline involved a detailed comparison and reconciliation of discrepancies between the original NIH image labels and the expert-generated annotations. These discrepancies were expected due to the inherent differences between the automated label generation process used for the NIH dataset and the refined expert annotations, which were manually reviewed and corrected to enhance labelling accuracy. The automated labelling process, while efficient for large datasets, can be prone to inaccuracies, particularly in complex cases with overlapping pathologies or subtle visual cues.

The manual review and correction by expert radiologists aimed to address these limitations and create a high-quality ground truth dataset for training the segmentation model.

Table 6 and

Table 7 provide a detailed comparison of the label distributions derived from the original NIH dataset and the refined expert annotations. This comparison highlights the specific areas where discrepancies existed and provides insight into the extent of the annotation refinement required to ensure data quality. Analysing these discrepancies is essential for understanding the limitations of the original NIH labels and for justifying the need for expert annotation in medical image analysis tasks.

As detailed in

Table 6 and

Table 7, our analysis of the initial annotations revealed significant discrepancies in labelling patterns, particularly in cases presenting multiple, concurrent pathological conditions. These inconsistencies, likely arising from subjective interpretations of subtle visual cues and the inherent complexity of multi-label annotation in chest X-rays, underscored the critical need for a systematic annotation refinement process. Ensuring both consistency and accuracy in the training data is paramount, as inaccurate or inconsistent labels can severely hinder the model’s ability to learn discriminative features and subsequently compromise its semantic segmentation performance.

Specifically, these labelling variations can introduce both noise and bias into the training process. Noise, in the form of randomly incorrect labels, can confuse the model and prevent it from converging to an optimal solution. Bias, on the other hand, can arise from systematic errors in labelling, such as consistently misidentifying a particular type of pathology. This can lead the model to develop a skewed understanding of the data, resulting in poor generalization performance on unseen examples and reduced clinical applicability.

The refinement process involved a detailed review of the discordant annotations by expert radiologists. This review focused on establishing clear, standardized criteria for identifying and delineating each pathological condition, ensuring consistent interpretation of imaging features and minimizing inter-observer variability. Particular attention was paid to cases with overlapping or ambiguous pathologies, where the distinction between different conditions could be challenging.

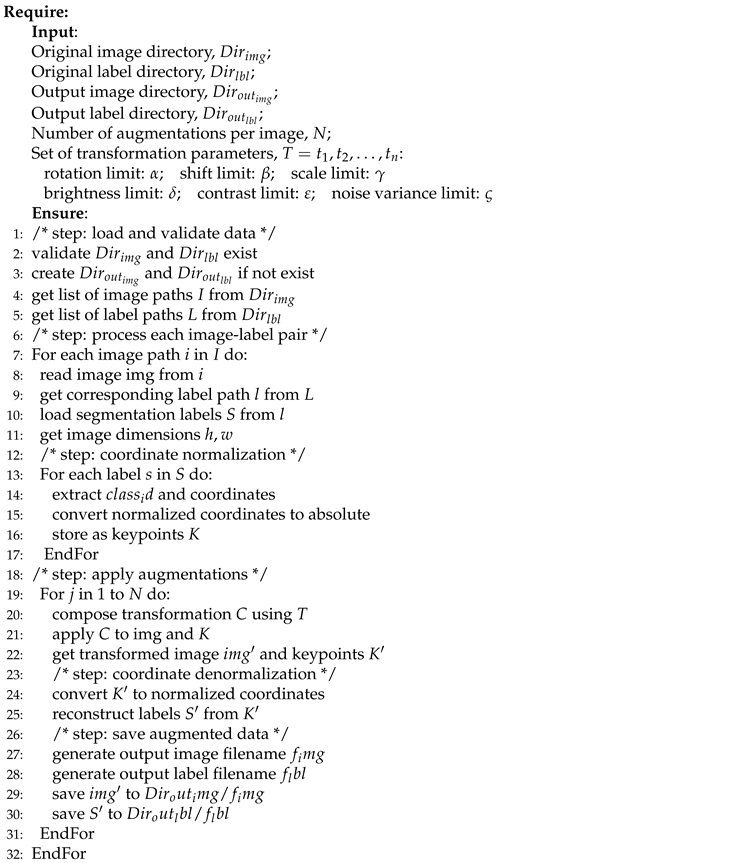

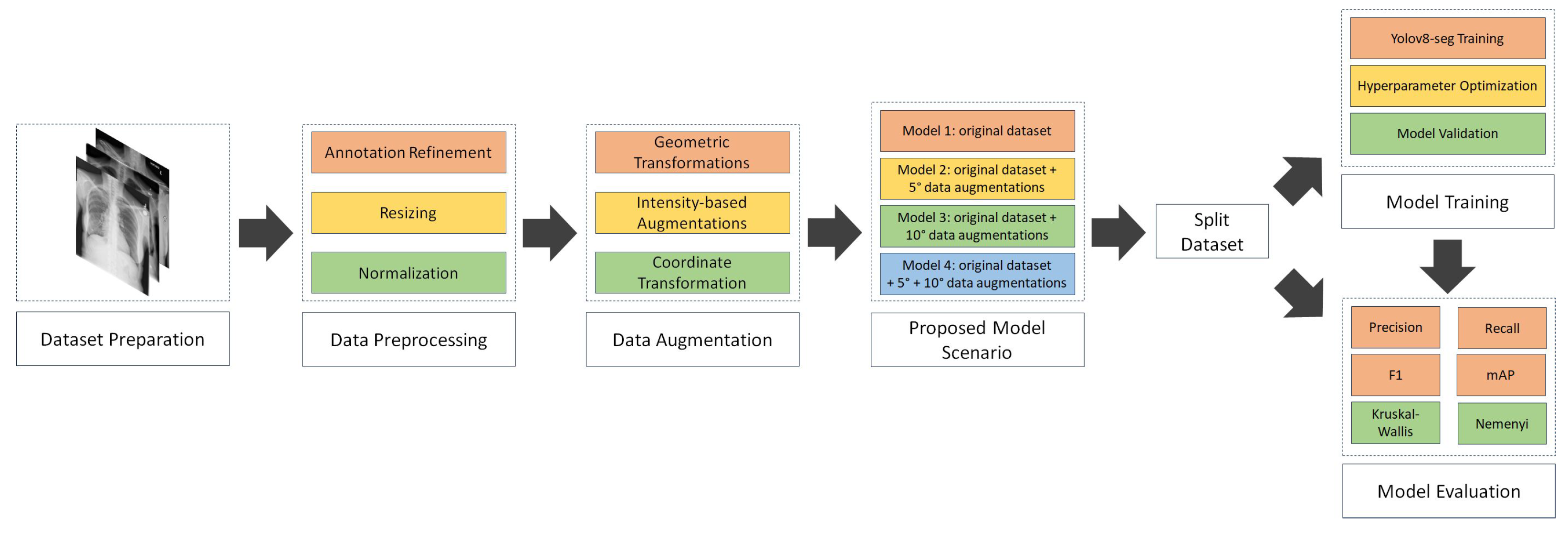

4.2. Result of NCT-CXR augmentation strategies

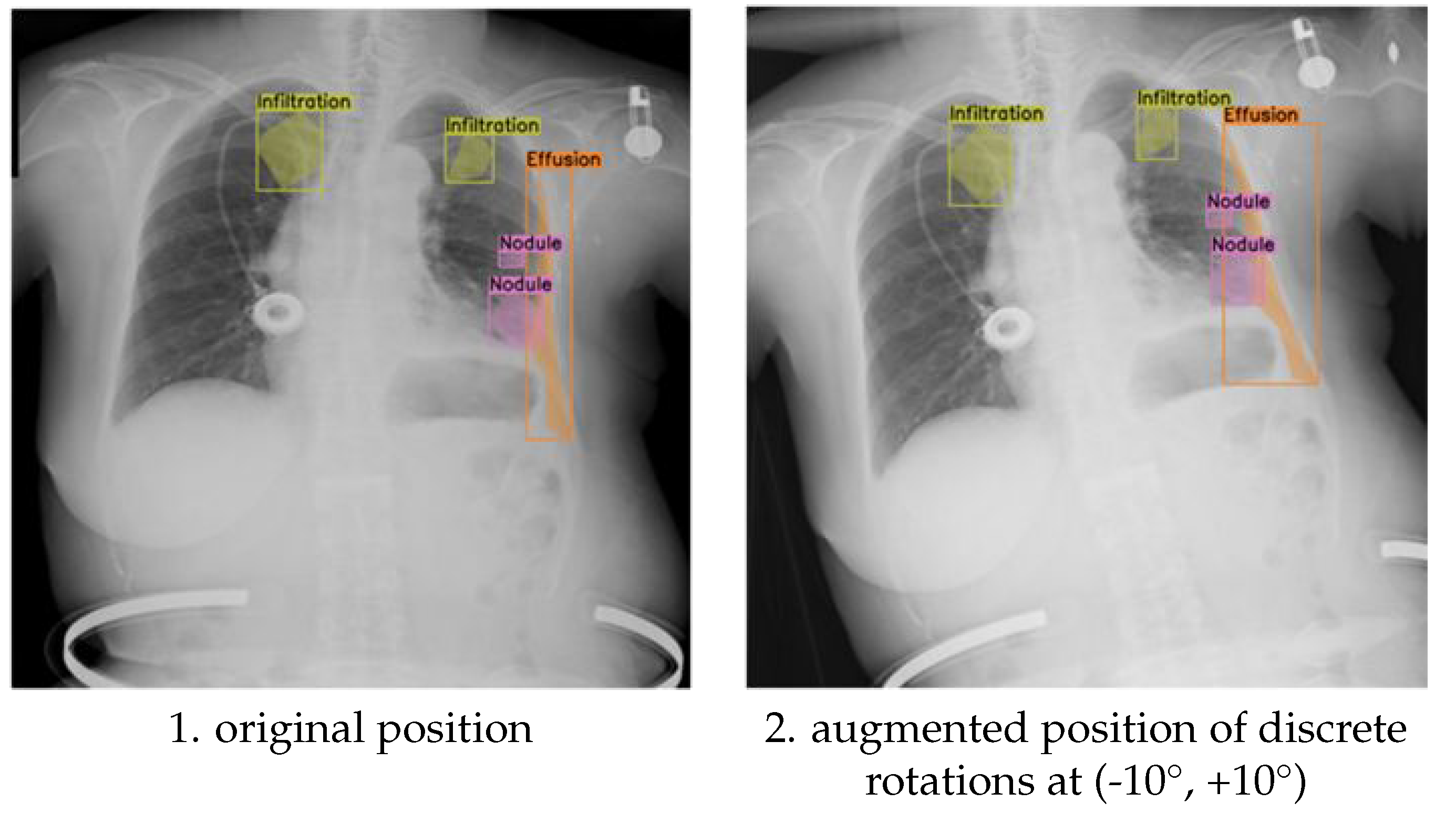

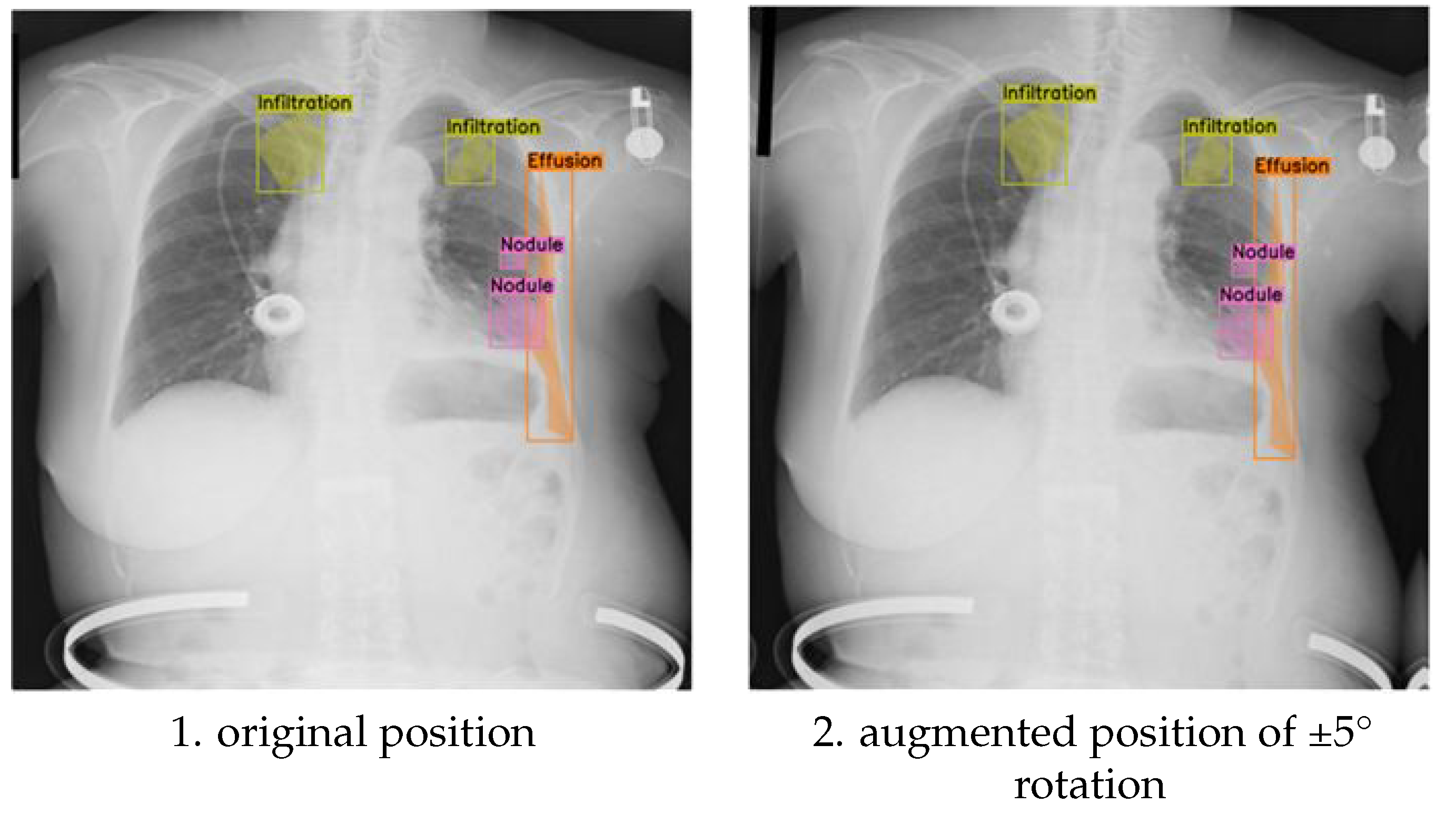

This section presents the experimental results, focusing on the differential impact of discrete rotations at (-10°, +10°,-5°,+5°) rotation augmentations on the semantic segmentation performance for detecting multiple pathological conditions in chest X-ray images. We hypothesized that the magnitude of rotation would influence the model’s ability to generalize to variations in patient positioning during image acquisition. We further hypothesized that a moderate degree of rotation would provide sufficient variability to improve model robustness without excessively distorting anatomical features. The results obtained with the discrete rotations at (-10°, +10°) rotation augmentation provide insights into how larger positional adjustments influence the placement of multi-label annotations for pathological conditions.

Figure 3 presents a visual comparison between original and (-10°, +10°) rotated images, demonstrating the effect of this transformation on the spatial distribution of labels for specific pathologies, including infiltration, effusion, and nodules. This visualization allows for a direct assessment of how the rotation affects the anatomical context of the annotations, which is crucial for evaluating the clinical relevance of the augmented data.

For instance, we examined whether the rotation preserved the relative spatial relationships between different pathologies within the same image. Maintaining these spatial relationships is critical for ensuring that the model learns to recognize the co-occurrence patterns of different pathologies, which can be important for diagnosis.

Furthermore, we analysed how the rotation affected the annotation of pathologies located near anatomical boundaries, where even small positional changes can significantly alter the visible features and potentially lead to annotation errors. Beyond visual inspection, we quantified these observations by measuring the changes in the centroid coordinates and bounding box areas (or the area of segmentation masks) of the annotated regions.

This quantitative analysis allowed us to correlate the magnitude of the annotation shift with the observed segmentation performance, providing a more objective and statistically rigorous measure of the augmentation’s impact. The following subsections will detail the quantitative results obtained with both (-10°, +10°) and (-5°,+5°) rotations, comparing their performance against the baseline model and discussing their implications for model performance and clinical applicability.

The results obtained with the discrete (-5°,+5°) rotation augmentation demonstrate how subtle positional adjustments impact the placement of multi-label annotations for pathological conditions in chest X-ray images.

Figure 3-1 provides a visual comparison between original and discrete (-5°,+5°) rotated images, illustrating the effect of this subtle transformation on the spatial distribution of labels for specific pathologies, including infiltration, effusion, and nodules. In the original, unaugmented images, the annotations align precisely with the anatomical features as identified during the initial labelling process.

After applying the discrete (-5°,+5°) rotation, the augmented images display minimal, yet noticeable, shifts in the bounding boxes (or segmentation masks), which remain closely aligned with their respective anatomical locations. This precise adjustment ensures that the semantic integrity of the annotations is preserved despite the transformation. The controlled discrete (-5°,+5°) rotation introduces realistic variability into the training data, simulating subtle changes in image orientation that can occur in clinical imaging. This augmentation enhances the model’s robustness by improving its ability to generalize across these small, but clinically relevant, positional variations, which are commonly encountered in real-world diagnostic scenarios.

The primary difference between the discrete (-10°, +10°) and discrete (-5°, +5°) rotation augmentations lies in the magnitude of the positional adjustment introduced to the multi-label annotations. In the case of the ±10° rotation (

Figure 3), the annotations for pathological conditions such as infiltration, effusion, and nodules undergo more noticeable shifts. This is a direct consequence of the larger rotation angle, which results in more significant displacements of the bounding boxes (or segmentation masks), while still maintaining their general alignment with the relevant anatomical structures. In contrast, the ±5° rotation (

Figure 4-1) introduces only slight positional changes, causing minimal displacement of the annotations. This subtle adjustment preserves the original spatial relationships between pathologies and anatomical landmarks while still adding valuable variability to the training dataset.

The larger rotation angle of ±10° increases the variability in the training data, which can make the model more robust against more substantial changes in image orientation that may occur in real-world clinical settings. This increased robustness comes at a potential cost, however. The larger rotations may introduce minor misalignments between annotations and anatomical features, especially in cases where the pathological features are small, subtle, or closely spaced. This potential for misalignment is less pronounced with the ±5° rotation. The ±5° rotation provides controlled variability that improves the model’s generalization capabilities without drastically altering the positions of key features. This makes it particularly useful for detecting subtle abnormalities with a minimized risk of annotation misalignment.

In summary, the (-10°, +10°) rotation augmentation is more effective for training the model to handle more substantial positional variations in chest X-ray images, enhancing its overall robustness. The (-5°, +5°) rotation, on the other hand, is ideally suited for fine-tuning the model’s performance by simulating minor orientation changes, ensuring both robustness to small variations and precision in the model’s predictions. The choice between these two augmentation strategies, or the combination thereof, depends on the specific clinical application and the desired balance between sensitivity and specificity.

4.3. Result of Chest X-ray segmentation and hyperparameter optimization

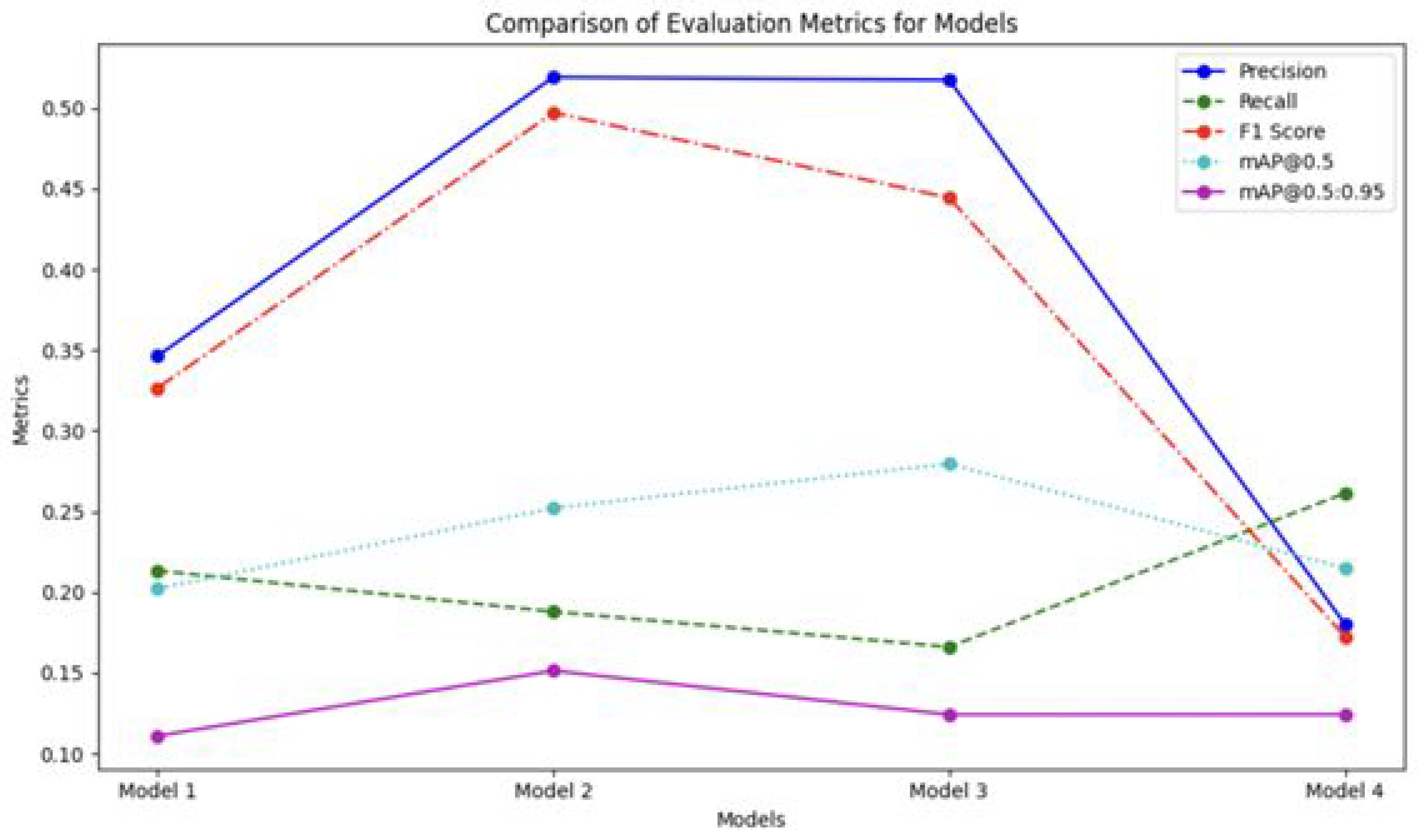

The results of the chest X-ray segmentation experiments highlight the significant impact of both data augmentation strategies and hyperparameter tuning on the performance of the YOLOv8 model. This section provides an in-depth analysis of the model’s performance across key evaluation metrics, including precision, recall, F1-score, and mean Average Precision (mAP). The comparison between the baseline model (trained without augmentation) and the augmented models clearly demonstrates how targeted transformations influence the model’s ability to generalize across diverse thoracic abnormalities.

Figure 5 illustrates the comparative performance of the models across multiple evaluation metrics, revealing the varying effectiveness of the different augmentation strategies. The most notable impact was observed in precision scores. Model 2 (trained with (-10°, +10°) rotation) and Model 3 (trained with (-5°, +5°) rotation) achieved significantly higher precision values of 0.519 and 0.517, respectively, compared to the baseline Model 1 (0.346) and Model 4 (trained with mixed ±5° and ±10° rotations) (0.180). This substantial improvement in precision is particularly significant, given the clinical importance of minimizing false positive detections in medical diagnosis. False positives can lead to unnecessary follow-up procedures, increased patient anxiety, and added burden on healthcare resources.

Figure 5 also depicts the performance of the models across other evaluation metrics, including recall.

Table 8 presents the recall values for different pathological conditions across the four model configurations: the baseline Model 1 (no rotation augmentation), Model 2 ((-10°, +10°) rotation), Model 3 ((-5°, +5°) rotation), and Model 4 (mixed ±5° and ±10° rotation). Recall, which measures the proportion of actual positive instances correctly identified by the model, is a crucial metric for evaluating the model’s sensitivity, particularly in medical diagnosis where missing abnormalities can have serious implications. A high recall value indicates that the model is effectively capturing most of the true positives, minimizing the risk of missed diagnoses.

As depicted in

Figure 5, the experimental results show the varying effectiveness of augmentation strategies on segmentation performance across multiple evaluation metrics, including recall.

Table 8 presents the recall values for different pathological conditions across the four model configurations: the baseline Model 1 (no rotation augmentation), Model 2 ((-10°, +10°) rotation), Model 3 ((-5°, +5°) rotation), and Model 4 (mixed ±5° and ±10° rotation). Recall measures the proportion of actual positive instances correctly identified by the model, making it a crucial metric for evaluating the model’s sensitivity, particularly in medical diagnosis where missing abnormalities can have serious implications.

For the overall recall (all classes combined), Model 4 achieved the highest recall value of 0.2610, outperforming the baseline Model 1 (0.2130) and the rotation-specific Models 2 and 3. This indicates that the mixed rotation strategy improves the model’s ability to detect abnormalities across different conditions. However, this improvement in recall suggests a potential trade-off between precision and recall that warrants careful consideration in clinical applications. While higher recall reduces the likelihood of missing abnormalities, it may come at the cost of increased false positives, which could lead to unnecessary follow-ups or interventions.

Therefore, balancing recall and precision is essential to ensure optimal performance for reliable and efficient medical decision-making. The lower precision observed in Model 4 suggests that the mixed rotation strategy, while improving recall, may be leading to an increase in false positive detections. This trade-off highlights the importance of carefully evaluating the performance of different augmentation strategies and selecting the one that best suits the specific clinical needs and priorities.

A class-specific analysis of the model’s performance revealed significant variations in detection accuracy across different pathological conditions, underscoring the importance of considering the unique characteristics of each abnormality when evaluating and optimizing segmentation models. As shown in

Table 9, the precision achieved for pneumothorax detection was notably high in both Model 2 (0.829) and Model 3 (0.804), significantly outperforming the other conditions and model configurations.

This substantial improvement in pneumothorax detection is particularly remarkable considering the relatively small representation of pneumothorax cases in the original dataset (97 cases, accounting for only 9.14% of the total). This suggests that the augmentation strategies employed, particularly the (+10°,-10°) and (+5°,-5°) rotations, were particularly effective in improving the model’s ability to accurately identify pneumothorax, even with limited training examples. The high precision values indicate that the model is making relatively few false positive detections for pneumothorax, which is crucial for clinical applications where accurate diagnosis is essential.

In stark contrast, the detection of infiltration proved to be a persistent challenge across all models, with inconsistent precision values reflecting the inherent complexity of identifying diffuse and often subtle pathological patterns. Infiltration often presents as ill-defined areas of increased opacity in the lung parenchyma, making it difficult to distinguish from other conditions or normal variations in lung tissue. The inconsistent precision values across different models suggest that the augmentation strategies employed were not as effective in improving the detection of infiltration as they were for pneumothorax. This disparity in performance across different classes highlights the fact that the effectiveness of data augmentation strategies is significantly influenced by the unique characteristics of each pathological condition. While some conditions, like pneumothorax, may benefit significantly from specific geometric transformations, others, like infiltration, may require different augmentation techniques or more sophisticated model architectures to achieve satisfactory detection accuracy.

This underscores the need for tailored approaches to enhance detection accuracy for challenging abnormalities, potentially involving a combination of targeted data augmentation, specialized network architectures, and refined annotation strategies. Further research is needed to investigate the specific factors contributing to the difficulty in detecting infiltration and to develop targeted strategies to address this challenge.

The F1-scores across the four model configurations, as shown in

Table 10, highlight the balance between precision and recall for detecting thoracic abnormalities. Model 4, which applied mixed discrete rotations at (-10°, +10°) and discrete rotations at (-5°, +5°), achieved the highest overall F1-score (0.3840), outperforming the baseline Model 1 (0.2637) as well as Models 2 (0.2760) and 3 (0.2513). This indicates that the mixed augmentation strategy improved the model’s ability to generalize across different conditions.

Pneumothorax showed the most significant improvement, with Model 2 achieving an F1-score of 0.5442, indicating a strong balance between precision and recall. Similarly, the detection of effusion improved, with Model 4 reaching an F1-score of 0.4320, reflecting the effectiveness of the mixed rotation approach. However, infiltration detection remained challenging, with F1-scores consistently at 0.0000 across all models, indicating the complexity of detecting diffuse pathological patterns. Pneumonia detection also had low F1-scores, with Model 4 achieving only 0.0980, suggesting a need for further optimization. In contrast, performance for atelectasis remained relatively stable, with Model 4 achieving the highest score (0.4120), demonstrating enhanced generalization without a significant drop in precision or recall. These findings indicate that while mixed augmentations improve overall performance, further targeted strategies are necessary to enhance detection for more challenging conditions such as infiltration and pneumonia.

The mAP@0.5 values across the four model configurations highlight the model’s ability to accurately localize and detect thoracic abnormalities at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5. Model 3 (discrete rotations at (-5°, +5°)) demonstrated the highest overall mAP@0.5 value (0.2800), followed by Model 2 (discrete rotations at (-10°, +10°)) with 0.2520, as shown in

Table 11. In contrast, Model 4 (mixed discrete (-5°,+5°) and discrete (-10°,+10°) rotations) showed a slight decrease (0.2150) compared to the baseline Model 1 (0.2020), suggesting that combining multiple rotations may introduce variability that impacts localization accuracy.

The mAP@0.5:0.95 values across the four model configurations indicate the model’s performance over a range of IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95, providing a more robust evaluation of localization precision for varying overlap levels. As shown in

Table 12, Model 2 (discrete rotations at (-10°, +10°)) achieved the highest overall mAP@0.5:0.95 (0.1510), surpassing Model 1 (0.1110) and performing better than the other models, particularly for classes with complex positional patterns.

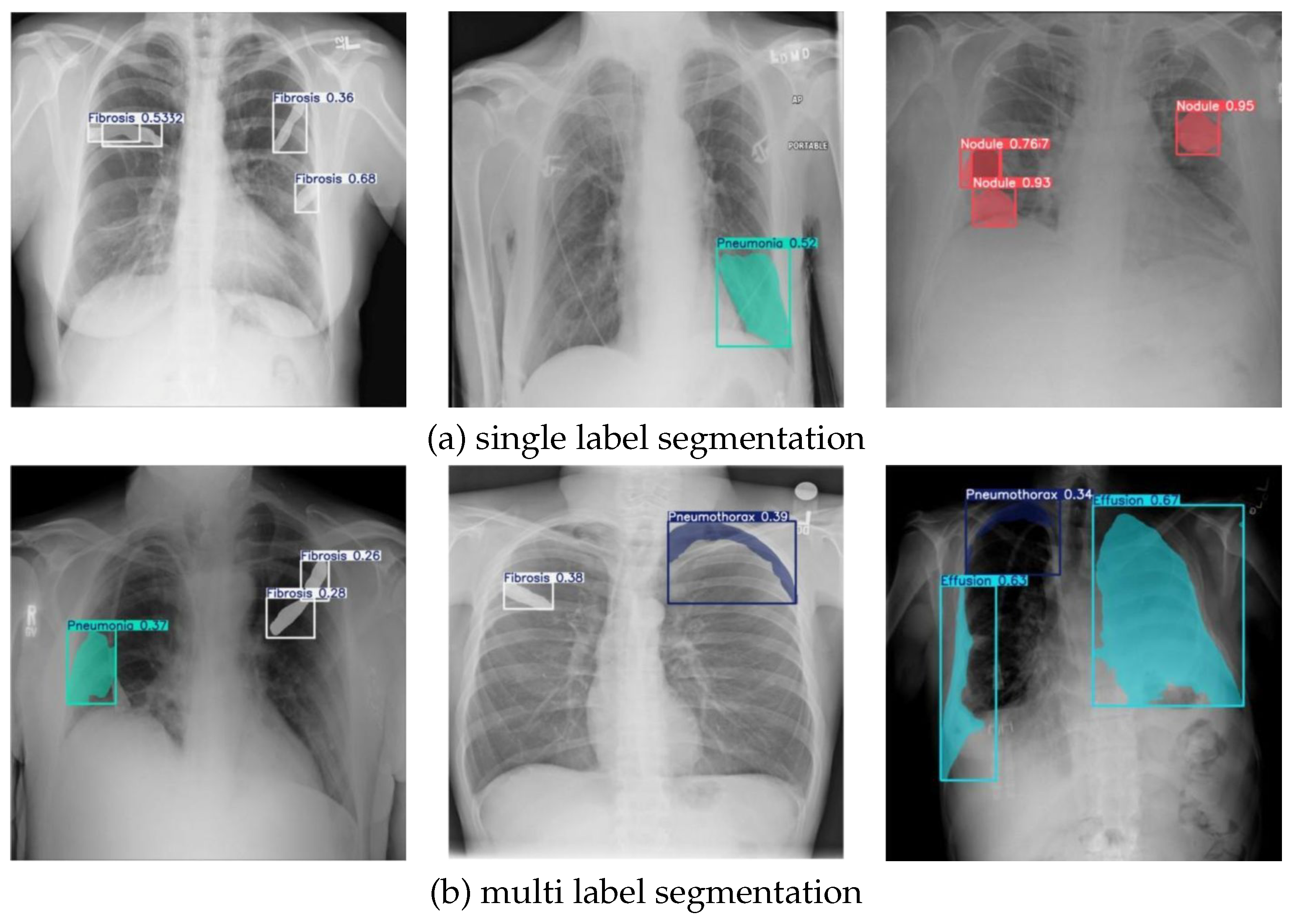

The results of chest X-ray segmentation, enhanced by the NCT-CXR framework, are shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6(a) presents the outcomes of single-label segmentation, while

Figure 6(b) demonstrates multi-label segmentation. In

Figure 6(a), the model’s effectiveness in single-label detection is highlighted, showcasing its ability to accurately identify and localize specific pathological conditions. The first image illustrates the segmentation of fibrosis regions, with confidence scores affirming the reliability of the detections. Similarly, the second image focuses on pneumonia, where a clear mask identifies the affected area with precision. The third image highlights the detection of nodules, with high confidence scores further validating the model’s accuracy in identifying these abnormalities.

Figure 6(b) illustrates the model’s performance in multi-label segmentation, where multiple pathological conditions are detected within the same image. The first image demonstrates the simultaneous segmentation of fibrosis and pneumonia, supported by confidence scores that validate the detection’s reliability. In the second image, the model effectively identifies both fibrosis and pneumothorax, showcasing its capacity to handle multiple abnormalities in a single chest X-ray. The third image highlights the detection of effusion and pneumothorax, with clear segmentation masks and confidence scores validating the model’s precision. These results demonstrate the NCT-CXR framework’s ability to accurately segment complex cases involving overlapping or co-occurring abnormalities, reinforcing its potential for clinical application in chest X-ray analysis.

4.4. Statistical Evaluation

The performance evaluation phase incorporates comprehensive statistical analyses to validate the significance of observed differences across model variations. Here, Kruskal-Wallis as Non-parametric statistical tests were employed to account for the potential non-normal distribution of performance metrics, the presence of outliers in the evaluation data and due to we are using relatively small sample.

The Kruskal-Wallis test was first conducted to determine whether statistically significant differences existed across the four model configurations: (1) the baseline model without augmentation, (2) the model with discrete rotations at (-10°, +10°), (3) the model with discrete rotations at (-5°, +5°), and (4) the mixed rotation model. This analysis was performed across all performance metrics (precision, recall, F1-score, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95) with a significance level of 0.05.

Following the significant Kruskal-Wallis result for precision as seen in

Table 13, a Nemenyi post-hoc test was conducted to identify specific pairwise differences between models.

As seen in

Table 14, the Nemenyi test revealed significant differences between: Model 2 (discrete rotations at (-10°, +10°)) and Model 4 (mixed rotation) (p = 0.005602). Then, Model 3 (discrete rotations at (-5°, +5°)) and Model 4 (mixed rotation) (p = 0.013806). Notably, while Model 1 (baseline) did not show statistically significant differences with other models, its comparison with Model 4 approached significance (p = 0.153177). Additionally, Model 2 and Model 3 demonstrated highly similar precision performance (p = 0.992827), suggesting that both moderate-angle rotation strategies (discrete rotations at (-5°, +5°) and discrete rotations at (-10°, +10°)) achieved comparable improvements in precision. These statistical findings provide strong evidence that the choice of rotation angle in the augmentation strategy significantly impacts the model’s precision in detecting pulmonary abnormalities, with moderate-angle rotations (Models 2 and 3) outperforming the mixed rotation approach (Model 4). The lack of significant differences in other metrics suggests that the augmentation strategies primarily influenced the model’s precision while maintaining consistent performance in other aspects of detection and segmentation.