1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major public health challenge, affecting approximately 463 million people worldwide, with projections reaching 700 million by 2045 [

1]. This metabolic disorder leads to prolongated hyperglycemia, which, if untreated, can result in severe complications such as neuropathy, nephropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular diseases [

2,

3]. Notably, 90% of people with diabetes have type 2 diabetes.

The primary goal of all diabetes treatment and management is to maintain an adequate blood glucose concentration. Currently, available pharmacological drugs are expensive with adverse effects, which include hypoglycemia, hepatotoxicity, and dyslipidemia. They often come with side effects and the risk of drug resistance [

4,

5]. Consequently, interest has grown in dietary approaches, particularly functional foods, as complementary strategies for diabetes prevention and management[

6]. Some plant-derived bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols, have shown promise in inhibiting carbohydrate-digestive enzymes like α-glucosidase and α-amylase, thereby reducing postprandial glucose levels and improving insulin sensitivity [

7,

8,

9].

Among bioactive compounds, betalains, a group of water-soluble nitrogen-containing pigments found in plants of the order Caryophyllales, have gained attention for their potential health benefits (antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties) beyond their role as natural colorants [

10]. Studies suggest that betalains may contribute to glucose homeostasis in a specific pathway by enhancing the activity of glycolytic enzymes (glucokinase and pyruvate kinase) while inhibiting gluconeogenic enzymes (glucose-6-phosphatase and fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase), thereby reducing blood glucose levels [

11,

12,

13]. Other works have studied betalains as a therapeutic approach for treating type 2 diabetes by lowering glucose absorption by inhibiting intestinal carbohydrate-hydrolyzing enzymes (alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase) [

14,

15,

16]. However, most studies evaluating these effects have used purified betalains or whole food matrices. This is a critical distinction because functional foods are complex systems where interactions between bioactive compounds and other food components can significantly alter their bioaccessibility [

17].

A common assumption is that bioactive compounds within functional foods will be readily bioaccessible and exert their beneficial effects; however, this is not always the case. The food matrix and digestive processes can modulate the bioaccessibility of these compounds, either enhancing their stability and absorption (synergistic effect) or reducing their effectiveness through interactions with other components [

17,

18]. Therefore, evaluating the impact of the food matrix on betalains bioaccessibility —defined as the fraction that remains available for absorption after digestion— is essential for understanding their real potential in functional foods and their physiological impact.

Red prickly pear (

Opuntia spp.) is an excellent source of betalains alongside other bioactive components such as soluble fibers, polyphenols, and flavonoids, which may contribute to betalains stability and bioaccessibility [

15,

19,

20]. The physicochemical properties of betalains, including their charge distribution and interaction potential with other food components, can affect their release and absorption during digestion. Additionally, their efficacy in modulating carbohydrate metabolism at the gastrointestinal level by inhibiting α-amylase and α-glucosidase may vary depending on these interactions [

13,

21,

22].

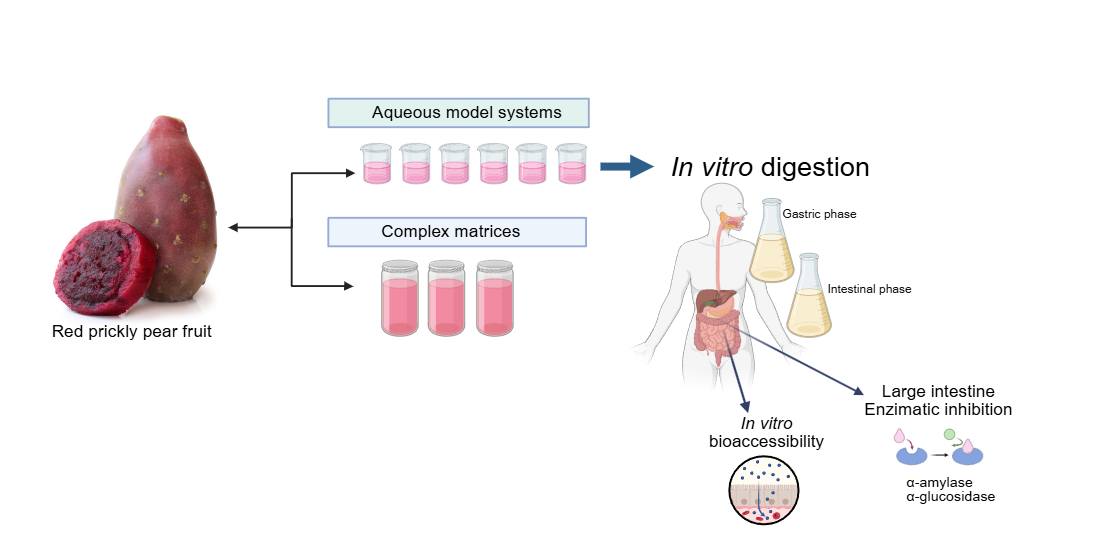

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of food matrix components of red prickly pear fruit on betalains bioaccessibility and carbohydrate degrading enzyme inhibition potential after in vitro digestion. Aqueous model systems were formulated using betalains and key juice components (pectin, mucilage, citric acid, and glucose), along with complex food matrices, including fresh red prickly pear juice (reference sample), a formulated beverage (fresh and pasteurized), to assess the influence of matrix complexity and thermal processing on betalains bioaccessibility and functionality. These findings provide insights into optimizing functional foods with betalains or red prickly pear fruit juice as ingredients for glucose level control.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

Red prickly pear fruits belonging to the Opuntia genus, "Zacatecas" variety (Opuntia spp.), were obtained from a local market in Jalisco, Mexico, and came from the state of Zacatecas, Mexico. Fruits selected for the study were free from mechanical or microbiological damage on the skin and were at a stage of commercial ripeness. They were washed with water and soap and stored at 5°C until juice was obtained. For juice obtention, the red prickly pear fruits were peeled, the seeds were separated from the peel using a strainer, and the juice was frozen until use.

2.2. Betalains Extract Obtention of Red Prickly Pear Juice

2.2.1. Betalains Extraction

In preliminary tests, seven different methods previously reported were evaluated. The methods varied in solvent polarity, extraction time, presence/absence of light, and purification method and times. The method reported by Cervantes-Arista et al. [

23] was selected, considering the amount of betalains and the polar green solvent used. To obtain a betalains extract, 150 g of fresh Zacatecas variety of red prickly pear juice were used, 675 ml of the solvent (distilled water) were added and stirred for 2 minutes in a dark room, then centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 5 minutes and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was frozen at -20°C for 72 h for subsequent lyophilization, aiming to concentrate and prevent the degradation of betalains.

2.2.3. Purification of Betalains Extract by Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

Considering that due to the use of water as a polar solvent to obtain the betalains extract (BE), the extract also contained sugars, so gel permeation chromatography (GPC) was used to remove these sugars following the method reported by Gonçalves et al. [

24]. The °Bx of each fraction obtained was determined and the identity of residual sugars was determined using Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC).

Finally, the fractions obtained were lyophilized. The content of betalains was measured using a spectrophotometric method (Thermo Scientific ™ Multiskan ™ GO Microplate, Waltham, MA), and the UV/vis absorption spectra were recorded from 200 to 700 nm to obtain absorption values at their respective absorption maxima. Measurements were performed in triplicate, and the betalains content (BC) was calculated according to the method reported by Gonçalves et al. [

24] (Equation 1):

"Equation 1: Betalains content [mg/g] =[(A(DF)(MW) V*1000 ⁄(εLPL)] "

Where A is the maximum absorption value at 538 and 483 nm for betacyanins and betaxanthins, respectively, DF is the dilution factor, V is the volume of initially extracted solution (in liters), LP is the lyophilized pulp weight (g), and L is the path-length (0.64 cm) of the plate. The molecular weight (MW) and molar extinction coefficient (ε) of betanin [MW= 550 g/mol; ε=60,000 L/ (mol cm) in H2O] were applied to quantify the betacyanins and quantitative equivalents of the major betaxanthins (Bx) were determined by applying the mean molar extinction coefficient [ε=48,000 L/ (mol cm) in H2O].

2.3. Aqueous Model Systems Formulation

Different aqueous model systems (AMS) were formulated (S1-S6) to simulate the complexity of red prickly pear juice, containing a fixed concentration of betalains extract (BE). The most abundant components in the prickly pear juice ranged from small molecules such as citric acid and glucose to more complex compounds such as polysaccharides (mucilage and low-methoxyl pectin). The exact amount of each component was previously determined in the juice. The aqueous model systems (AMS) were formulated by combining betalains extract (BE) with each component individually (glucose, citric acid, low methoxyl pectin, and mucilage) in water (S1-S5), as well as by creating a final, more complex system that closely resembles the composition of red prickly pear juice (S6). The concentrations of each component were established based on their content per 100 g of fresh red prickly pear juice (JF) and compared against it.

Additionally, two more complex model systems were formulated. The first formulated beverage (BF) (patented formulation) was based on red prickly pear juice, and the second was the same drink subjected to a conventional pasteurization process following the method described by Ayala Bendezú [

25] to obtain the beverage pasteurized (BP).

Table 1 summarizes and represents the formulated aqueous model systems, their components, chemical features, and their classification based on complexity and the three complex food matrices used: the fresh juice (JF), the formulated beverage (BF) and the formulated beverage pasteurized (BP).

Subsequently, the antioxidant potential of the samples was determined by two different methods (ABTS and DPPH assays) to understand the effect of the interaction of betalains components of the food matrix and its impact on its bioaccessibility.

2.4. Antioxidant Potential

2.4.1. DPPH Assay

DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) assay was carried out according to the method reported by Virgen-Carrillo et al. [

26] with some modifications. The AMS and the complex food matrices were diluted to a 1:4 ratio with distilled water (0.075 mg/ml). In a 96-well flat-bottom plate, 20 μl of the diluted samples, Trolox standard (0.1- 1.5 mM) or blank (distilled water) were loaded, followed by the addition of 180 μl of 0.06 mM DPPH in 80% methanol, and then incubated in the dark for 30 min. After incubation, the absorbance was read at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific ™ Multiskan ™ GO Microplate, Waltham, MA), and the results were expressed as micromoles of Trolox equivalents.

2.4.2. ABTS Assay

ABTS (2,2-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) assay was performed according to the method reported by Virgen-Carrillo et al. [

26] with some modifications. Samples were diluted to a 1:4 ratio with distilled water (0.075 mg/ml). In a 96-well flat-bottom plate, 20 μl of the diluted samples, Trolox standard (0.05-0.75 mM) or blank (deionized water) were added, followed by the addition of 180 μl of 7 mM ABTS

+ radical solution. The absorbance was read at 734 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific ™ Multiskan ™ GO Microplate, Waltham, MA). Trolox was used as a standard for the calibration curve, and the results were expressed as micromoles of Trolox equivalents.

2.5. In Vitro Digestion

The six aqueous model systems, the betalains extract (BE), the two drinks and the fresh juice, were subjected to

in vitro digestion following the methodology proposed by Domínguez-Murillo and Urías-Silvas [

27] with some modifications.

Gastric stage: One ml of each sample was taken and mixed with 90 ml of a 2% w/v NaCl electrolyte solution, 3.2 g/L of porcine pepsin enzyme w/v [≥250 units mg−1] (EC. 3.4.23.1, Sigma-Aldrich, Mexico) was also solubilized at 25000 U ml−1, the pH of each sample was adjusted at pH 2.0 with HCl (1 N), the samples were left under constant stirring (100 rpm) in a water bath at 37°C for 2 h. 1 ml of the samples submitted to the gastric phase was saved for subsequent analysis; the remaining volume was used to continue with the intestinal stage.

Intestinal stage: The pH of the samples was adjusted to 7.0 with NaOH (1 N), then 1 ml of aqueous solution of pancreatin enzyme [8×UPS] (EC. 232–468-9, Sigma-Aldrich, Mexico) (0.2%) w/v and 1 ml of aqueous solution of bile salts at 3% w/v were added to the remaining volume of the previous phase. The digestion was incubated for 4 h in a shaking water bath (100 rpm) at 37°C.

Bioaccessibility was calculated based on the concentration of betalains determined by spectrophotometry. The relationship between the concentration of betalains in the intestinal aqueous phase at the end of digestion (supernatant) and its initial concentration in the aqueous model system (AMS) were obtained. (Equation 2).

"Equation 2: % Bioaccessibility = ["Betalains content supernatant" /"Betalains content AMS"] X100"

The final volume was used to perform enzymatic inhibition tests of two enzymes in the small intestine responsible for food degradation.

2.6. Enzymatic Inhibition Assay

For this stage, all aqueous model systems were evaluated; also, the components of each model system (without betalains) were used to find out if any of them individually had an inhibitory effect on the activity of the enzyme or if they promoted synergy with the betalains. The drug acarbose (1mM) in two different presentations, Pharmalife® drug grade and Sigma® A8980-1G reagent grade, were used as a positive control. This procedure was done following the methodology of Gómez-Maqueo and García-Cayuela; Mojica et al.; Oluwagunwa et al. [

15,

28,

29], and the Merck method for the enzyme α-amylase [

30], with modifications.

2.6.1. α-Amylase Inhibition

Samples and acarbose (positive control) or PBS (negative control) were prepared in water. Inhibition α-amylase activity was determined by quantifying reducing sugars using dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS). Samples or controls of 100 μl of (0.3 mg/ml of betalains) in AMS and the complex food matrices were added to 100 μl of α-amylase (1U/ml) and 200 μl of sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 6.9) to obtain 0.075 mg/ml final concentration of betalains. The samples were pre-incubated at 25 °C for 10 min, and 200 μl of 1% starch prepared in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) was added. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 25°C for 10 min. The reactions were stopped by incubating the mixture in a boiling water bath for 5 min after adding 1 ml of dinitrosalicylic acid. The reaction mixtures were cooled to room temperature and diluted with distilled water to reach a final volume of 12 ml. The amount of reducing sugars released by its enzymatic action was determined spectrophotometrically (Thermoscientific TM multiscan TM Go, USA) using a maltose standard curve (0.5 to 2 mg/ml) at 540 nm in a 96 multiwell plate with 300 µl of each sample. A control and blank sample were used to subtract the betalains interference at 540 nm. This procedure was also carried out for all samples with and without enzyme, to subtract the noise value from the samples with enzyme and have the net values of the enzyme inhibition. The results obtained by these three independent experiments were considered to calculate the enzymatic inhibition percentage with equation 3, reported by Oluwagunwa [

29]:

Equation 3: % enzymatic inhibition =AbsControl-(AbsSample-AbsSaBco)) /AbsControl x100

Where:

AbsControl: It is the maximum absorbance of starch without enzyme (C -)

AbsSample: Net absorbance of each sample

AbsSaBco: Absorbance of each sample without enzyme

2.6.2. α-Glucosidase Inhibition

For the α-glucosidase inhibition assay, the method reported by Virgen-Carrillo et al. [

26] was used with slight modifications. The samples were diluted 1:8 [0.07 mg/ml of betalains] in distilled water. Then 50 μl of each diluted sample, acarbose (positive control), or PBS (negative control) were added to a 96-well plate, followed by 100 μl of alpha-glucosidase enzyme (1U ml

−1 from

Saccharomyces cerevisiae PBS, 0.1M pH 6.9) and incubated for 10 min at 37°C with stirring intervals (10 seconds), after 10 min the absorbance was measured at 405 nm in a spectrophotometer (ThermoscientificTM multiscanTM Go, USA) to subtract the betalains interference. Then, 50 μl of substrate 4-nitrophenyl alpha-D-glucopyranoside (4p-NPG [5mM] in PBS [0.1 M], pH 6.9) were added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 405 nm, which represents the 4-nitrophenol released by the enzymatic activity. The results were expressed as alpha-glucosidase inhibition percentage.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analyses were conducted using R (R Core Team 2024). Data visualization was performed using the ggplot2 package [

31], while data manipulation was carried out with the dplyr package [

32]. Post-hoc comparisons were visualized using the multcompView package [

33]. Data represents the mean and standard deviations of three replications. Tukey HSD test was used to detect statistical differences between treatments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Betalains Extract Obtention of Red Prickly Pear Juice

Using water as solvent (eco-friendly), 2.224 mg betalains/g juice was obtained. Starting with 150 g of juice resulted in a total extraction of 336 mg of betalains (

Table 2). The purification of the extract was achieved through gel permeation chromatography (GPC), a technique that effectively eliminated sugars from the sample, as corroborated. This purification process significantly improved the extract's quality by minimizing impurities and increasing the concentration of betalains. The extract was used to simulate a food matrix, preserving the full diversity of betalains in red prickly pear juice.

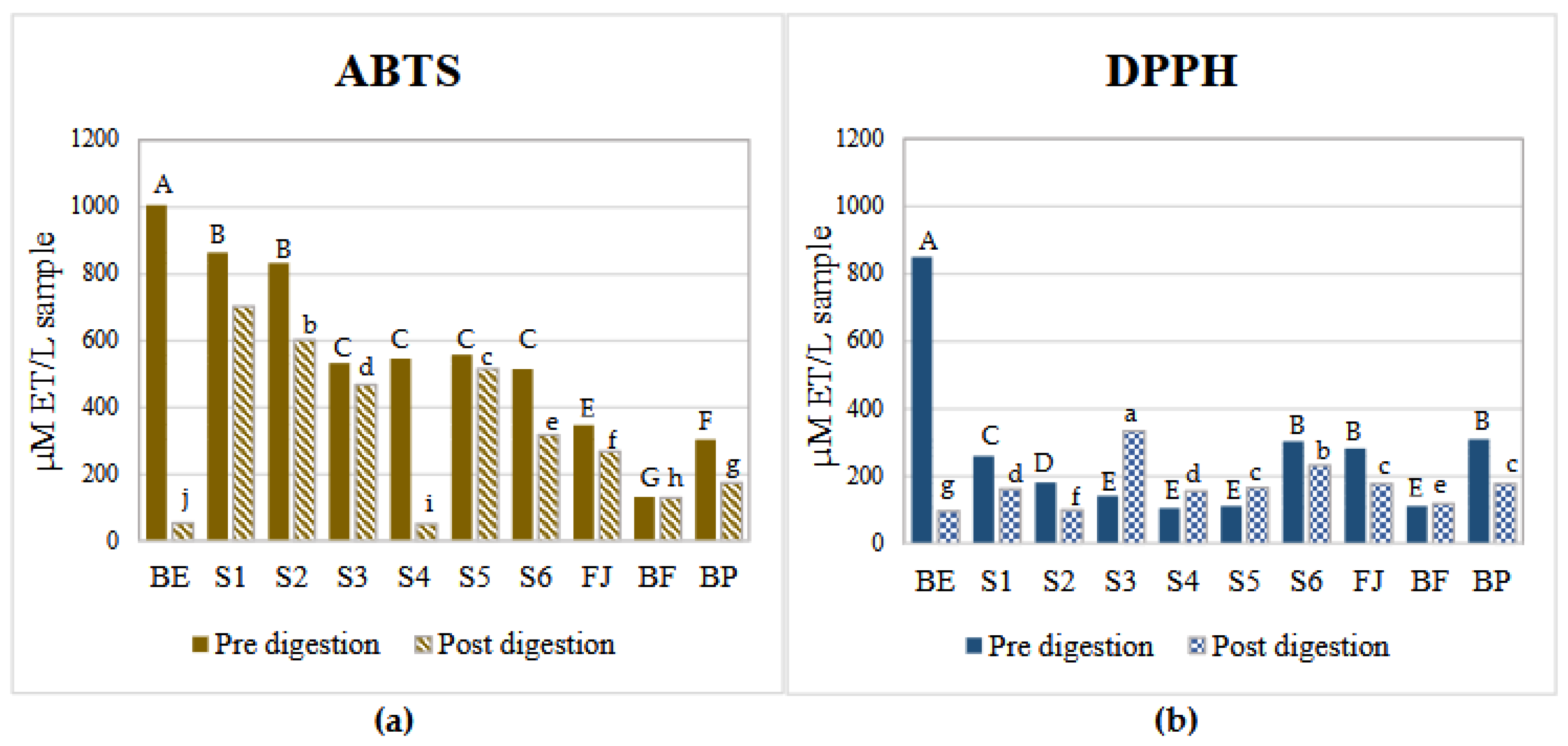

3.2. Antioxidant Potential of Betalains and AMS (DPPH and ABTS Assay)

Figure 1 shows the antioxidant potential of AMS formulated with the betalains extracts and the complex food matrices FJ, BF, and BP against two different radicals (DPPH and ABTS) before and after the digestion process. A decrease in the antioxidant potential of all samples against the ABTS radical was observed after digestion. Before digestion, complex model systems presented a lower reduction potential against the DPPH compared to the ABTS radical (

Figure 1a and 1b). Before digestion and against the two radicals, the sample with the highest antioxidant activity was BE (betalains extract), followed by the model systems (S1-S5), verifying that the bioactive compounds of the prickly pear juice are betalains and their interaction with the components of the juice matrix affects and reduces the amount of free betalains and therefore, their antioxidant potential. After digestion, the sample with the lowest antioxidant potential was BE (betalains extract), which also confirms that the components of the food matrix are necessary to protect betalains during the digestion process.

Comparing the results of the fresh (BF) and pasteurized beverage (BP), it was observed that the BF had a lower antioxidant potential compared to BP. This could be due to pasteurization that degrades complex polysaccharides, allowing the release of betalains and improving their interaction with the free radicals. This tendency was observed before and after digestion.

It has been reported that the common mechanisms by which betalains reduce free radicals involve a single proton transfer followed by electron transfer (SPLET) or hydrogen atom transfer/proton-coupled electron transfer (HAT/PCET). The difference between both is that (HAT/PCET) is the possible mechanism due to the low bond dissociation energy (BDE) required and their charge stability in aqueous media [

24,

34]. The values of antioxidant potential are shown in

Table 3.

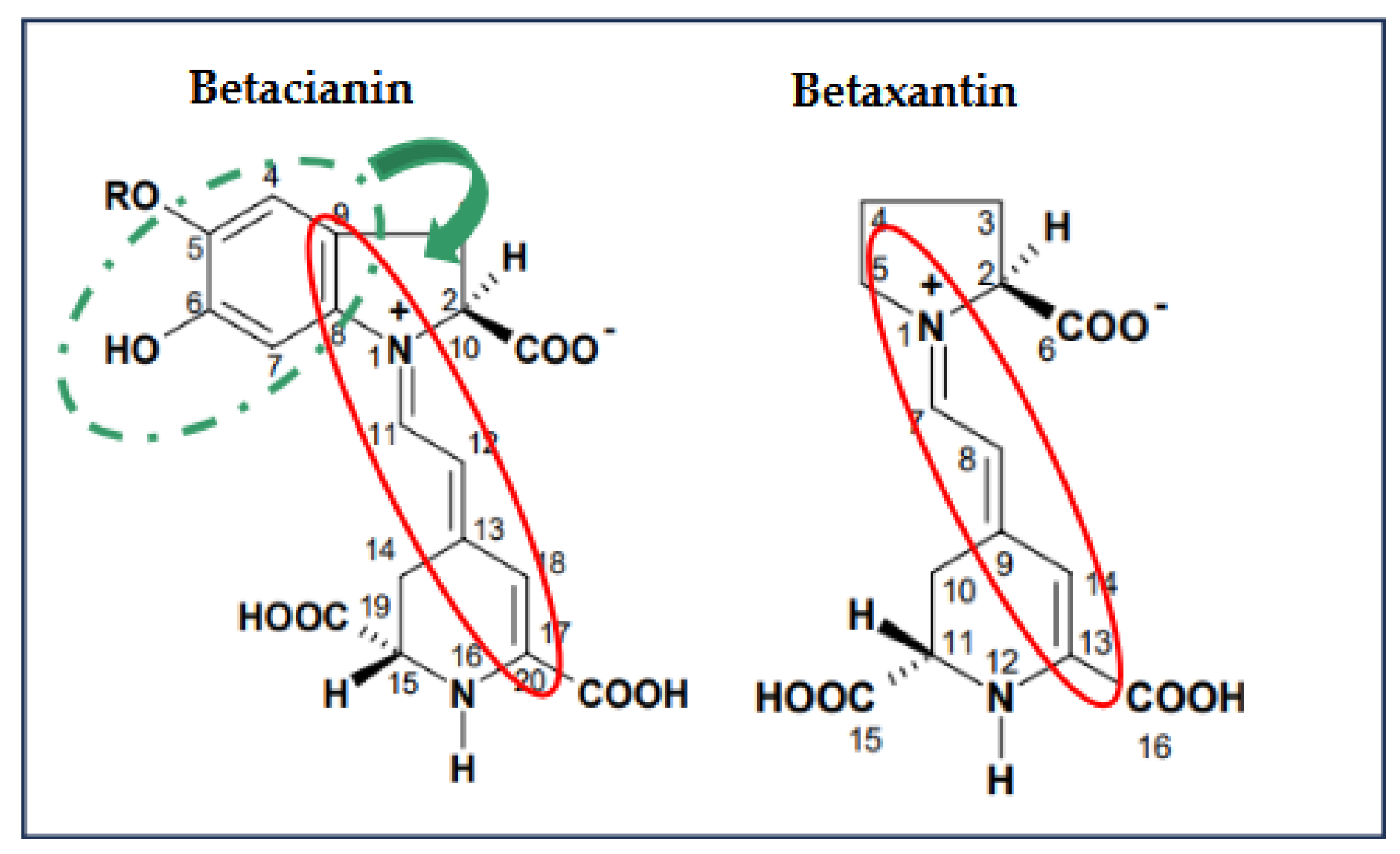

To reduce the ABTS

+ radical, the transfer of hydrogen atoms is necessary by the betalains. Therefore, in S1 (betalains + water), the phenolic group is possibly not conjugated with the diazapolymethine system and is free to perform its function (

Figure 2). Still, when there are more components in the aqueous model systems, the formation of interactions that stabilize betalains is favored, as may occur in samples FJ (fresh juice), BF (fresh beverage), and BP (pasteurized beverage), thus compromising the free functional groups that could perform the antioxidant function of the betalains by reducing the radical.

Conversely, evaluating the antioxidant potential of the samples against the DPPH radical revealed a progressive increase with the growing complexity of the model system. This is because the reduction mechanism of this radical (DPPH) is through the transference of electrons by the conjugated double bonds within the aromatic rings, enhancing their overall antioxidant potential, so betalains require an ionization potential (IP) and an energy transfer enthalpy (EFE) more significant than those required to give up an H

+ atom, these results corroborate that the primary mechanism by which betalains reduce free radicals is through the transfer of hydrogen atoms. However, when betalains interact with other food matrix components, this mechanism may be hindered, allowing betalains to transfer electrons instead of releasing an H+, even though this process requires more energy; this is possible due to their diazapolymethine system (

Figure 2) [

24]. It can be inferred from systems S4 (BE + pectin) and S5 (BE + mucilage), where betalains are combined with hydrophilic polysaccharides, that they can interrelate through dipole-dipole interactions, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions due to the slightly acidic pH of the aqueous model systems, additionally, in more complex systems such as S6 (BE + all the components), JF (fresh juice), and beverages (BF and BP), where betalains, being polar nitrogen compounds, can interact with food matrix components such as carbohydrates (e.g., mucilage, pectin, and dietary fiber), proteins, and other small molecules through weak non-covalent forces (e.g., hydrogen and van der Waals bonds), the interactions are increased. These complex interactions may contribute to the enhanced antioxidant potential observed in these systems. Although JF, BF, and BP were not formulated in this study, the model systems (S1–S6) were designed to preserve the betalain content comparable to that of natural matrices.

Other studies have explored the role of the structure in the antioxidant potential of betalains and betalamic acid, concluding that phenolic betalains exhibit higher antioxidant capacity compared to non-phenolic derivatives [

12,

35,

36,

37,

38]. However, the knowledge of structure-property relationships of betalains is still limited compared to other important classes of plant pigments, such as polyphenols, anthocyanins, and carotenoids.

The antioxidant potential of betalains is attributed to their unique structure (

Figure 3), which includes phenolic groups and conjugated systems that facilitate electron or proton donation, depending on the interactions occurring within the food matrix, enabling them to neutralize free radicals effectively. As a result, betalains demonstrate promising applications in treating oxidative stress. These results highlight the significant antiradical capacity of betalains, and such interactions might also hinder betalains from performing other crucial biochemical functions in the body.

3.3. Betalains Bioaccessibility and Hypoglycemic Effect After In Vitro Digestion

3.3.1. In Vitro Digestion Bioaccessibility

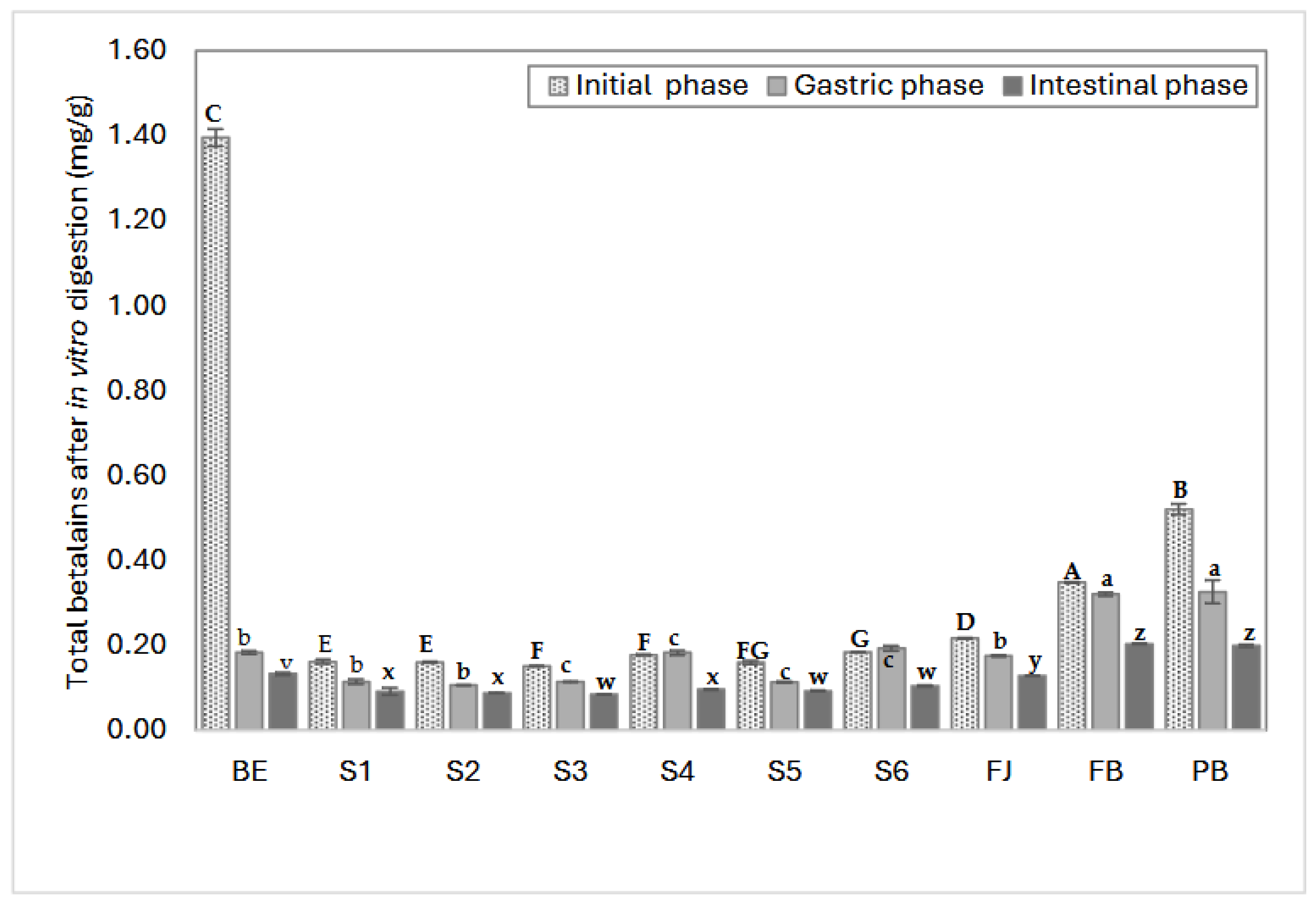

The content of betalains and bioaccessibility percentage after

in vitro digestion is shown in

Figure 3. The results show that the amount of free betalains in the evaluated samples varied according to the ingredient with which they were mixed, the extract containing 7 times more betalains (1.3 mg/g) than the formulated model systems (S1-S6), which had values ranging between 0.30 and 0.32 mg/g. Various studies have reported that betalain content in prickly pear fruit ranges from 0.11 to 0.6 mg/g (fresh weight) [

21,

39,

40]. In this work, model systems were designed with approximately 0.3 mg/g of betalains, and the complex systems such as FJ, BF, and BP contained between 0.2 and 0.5 mg/g of betalains, representing the average betalain content in red prickly pear fruit.

During digestion, the gastric phase was the most critical for betalain degradation, as this phase caused a significant reduction in betalains. This is due to the low pH produced by gastric acids, which promotes the protonation and destabilization of betalains, rendering them highly susceptible to degradation [

41]. For instance, the BE, despite having the highest initial concentration of betalains (1.3 mg/g), exhibited a marked reduction (87%, 0.18 mg/g) during the gastric phase when compared to the other systems and complex matrices. This observation highlights that betalains do not inherently possess resistance to digestive conditions, and their bioaccessibility mainly depends on the composition and structure of the food matrix in which they are embedded. It also confirms that bioaccessibility is more relevant than the initial concentration of the compound, as interactions with the matrix can either limit or enhance the stability and final biological activity of betalains [

21,

42].

During the gastric phase, the BP (pasteurized beverage), S2 (BE + glucose), and S5 (BE + mucilage) systems exhibited the highest degradation rates (62%, 46%, and 42%, respectively). In the case of pasteurized beverage (BP), the high degradation rate could be attributed to the heating process (80°C) inherent to the pasteurization, which may promote the degradation of both betalains and polysaccharides (S2 and S4), in particular, heating can cause chain fragmentation through the cleavage of α-(1→4) linkages or the removal of methyl groups, reducing their stability and size during digestion [

43].

Fresh juice (FJ) exhibited a high percentage of bioaccessibility (59%), followed by the beverage formulated (BF) (58%), equivalent to 0.1-0.2 mg/g of remaining betalains. This suggests that betalains require other components, sugar-rich compounds such as polysaccharides (pectin and mucilage) to stabilize their structure during digestion, for example, systems S4 (BE + pectin), S5 (BE + mucilage), and S6 (BE + citric acid, glucose, pectin, mucilage) helps to stabilize the betalains’ conjugated double bond system [

44,

45,

46] and glucose, when dissolved, can interact with protons (H⁺) in solution, reducing the effective protonation activity in the immediate environment of betalains and lowering degradation rates due to excessive protonation at betalains' functional sites [

41]. All the bioaccessibility percentages and betalain content during

in vitro digestion are presented in

Table A1.

The S5 system, which contains betalains extract and mucilage, showed one of the lowest betalains reduction rates. It is suggested that mucilage may interact with betalains, stabilizing them and allowing them to reach the intestinal phase, where they must be absorbed to carry out specific mechanisms in the body. The main functional groups in betalains interacting with other components are carboxyl or hydroxyl groups, specifically carbons C10, C19, and C20 [

42,

47,

48]. Additionally, the S4 system, which contains pectin, another abundant polysaccharide in red prickly pear juice, exhibited higher betalain content after the gastric phase than the other systems. This could be due to pectin’s low degree of methoxylation, which may favor the exposure of free polar regions (COO

-) capable of interacting with betalains, promoting the formation of esterified betalains, and protecting them from oxidation during digestion [

41].

Figure 3 shows the values of bioaccessibility, comparing the variations in betalains content (mg/g) due to the action of digestion in each model system, the fresh juice and the two beverages, highlighting the protective effect of the juice matrix on the remaining betalains after

in vitro digestion. Fresh juice (FJ) retained the highest amount of total betalains after digestion, followed by system S6, which mimics the complexity of juice with its most representative components.

Systems containing pectin (S4), and mucilage (S5) exhibited higher remaining betalains. It is important to note that while these systems retained higher amounts of betalains, the percentage of bioaccessibility varies.

A comparison between betacyanins and betaxanthins showed that betacyanins predominated in red prickly pear juice, even after the gastric phase. However, betaxanthins became more prevalent by the end of the digestion process. This could be attributed to the degradation of betalains into colorless structures or their precursors, such as cyclo-DOPA and betalamic acid, reducing their chromophore capacity [

41].

The results obtained in this study align with those reported in other works that also studied the effect of the food matrix on betalains' bioaccessibility, further validating the protective effect of the food matrix. However, the bioaccessibility of betalains in red prickly pear juice (58%) was higher than reported beetroot and cactus berry fruits [

21,

39]. The food matrix components and their interactions with betalains prevented them from degradation through the gastrointestinal tract until they reached their active site. The protection level provided by the food matrix is an important factor to consider. It could be possible that the juice matrix protects betalains during the digestion process, increasing the amount of betalains that finally reach the intestine so they can perform other specific functions, such as inhibiting digestive enzymes. This study found that as the complexity of the food matrix increases, the bioaccessibility of betalains also increases. At the same time, the antioxidant activity decreases due to the interactions between betalains and the food matrix. Complex matrices can confer protection during digestion, thereby promoting bioaccessibility by mitigating the degradation of compounds. Nevertheless, excessive protection could potentially hinder the release and subsequent absorption of betalains in the small intestine. So, it’s necessary to achieve an optimal balance between enhancing stability throughout digestion and ensuring effective bioaccessibility.

3.3.2. Hypoglycemic Effect

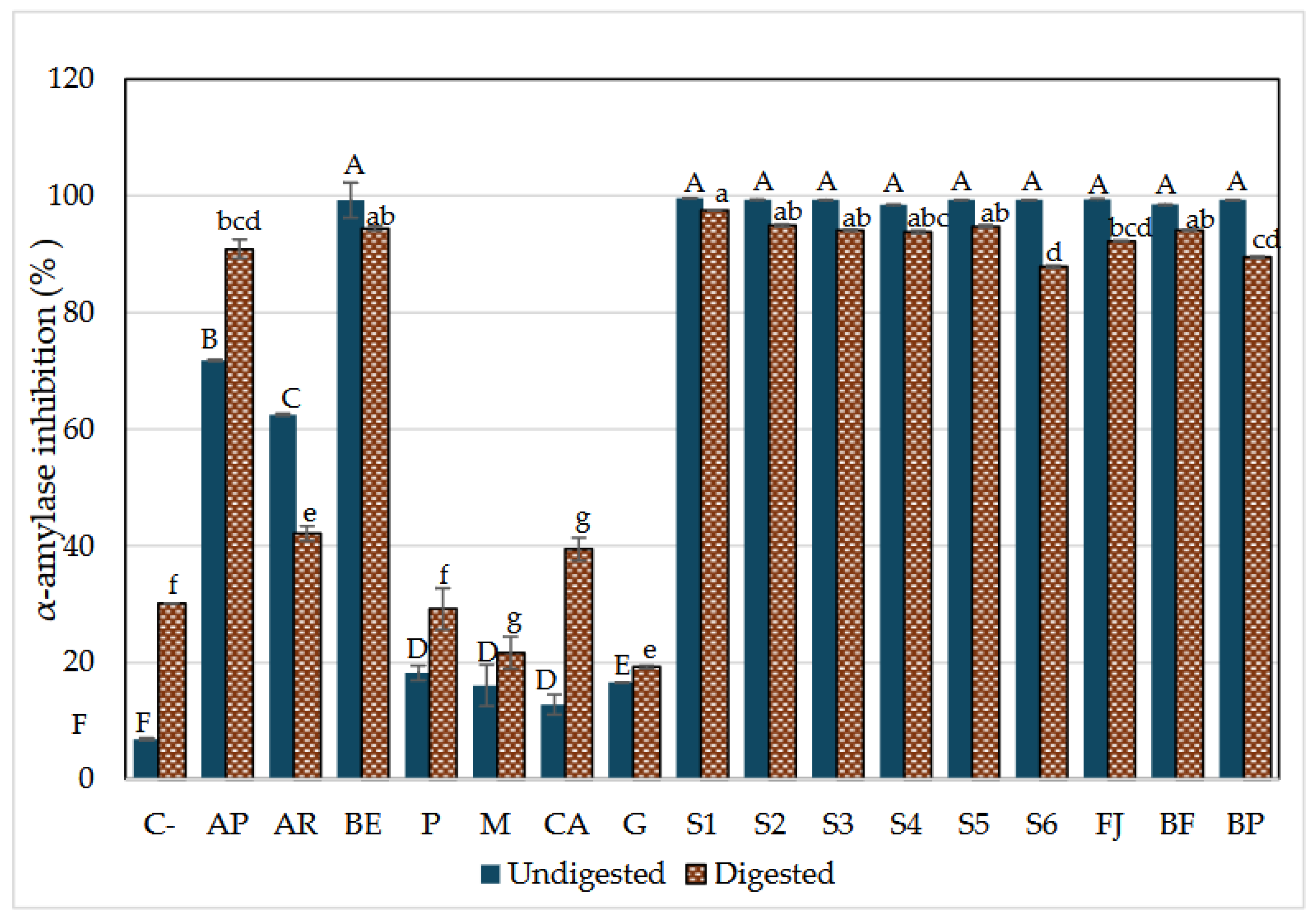

3.3.3.1. α-.Amylase Inhibition

α-amylase is an enzyme responsible for breaking down dietary starch into oligosaccharides and then into monosaccharides that can be absorbed by epithelial cells [

29]. Therefore, its inhibition is considered an active strategy to reduce the amount of glucose available, which can help manage type 2 diabetes. The inhibitory potential of AMS (aqueous model systems) was compared with the acarbose, which is responsible for lengthening duration of the carbohydrate absorption and hence reducing plasma glucose levels over time [

8].

Figure 4 shows the potential inhibitory effect of all model systems before and after

in vitro digestion. The components of the model systems were individually assessed for their potential inhibitory effects. Although ingredients without betalains had an inhibitory effect on enzyme activity, this was significantly lower than when combined with betalains. However, it is important to notice that P (pectin), M (mucilage), CA (citric acid), and G (glucose) inhibited α-amylase activity after digestion; this could be due to that P and M are soluble fibers that create steric hindrance between the enzyme and its active site during digestion inducing changes in enzyme conformation. Also, the enzymes are sensitive to pH, so the presence of CA can influence its activity by altering the ionization state of key amino acid residues in both the active site and other parts of the enzyme structure that affect its activity [

2].

The AMS (aqueous model systems), both beverages (formulated and pasteurized beverages) as well the betalains extract (BE) inhibited between 87% and 98% the α-amylase activity; the S1 (BE + water) and S5 (BE + mucilage) were the most potent models to inhibit α-amylase even after digestion and compared to acarbose in its two presentations pharmaceutical (AP) and reagent grade (AR). Moreover, AP increased its inhibitory potential after in vitro digestion, which is associated with the formulation requirements of medications to ensure their efficacy through the digestive process (excipient), in contrast to the inhibitory capacity of AR, which diminished after digestion.

Given the low inhibitory effect observed in the ingredient solutions without betalains, it is clear that betalains play a crucial role in enhancing the inhibitory effect. This is demonstrated by the significant inhibition achieved with both AMS and JF (fresh juice), where an increase in the inhibition of α-amylase activity is evident compared to systems without betalains. These results suggest that the hypoglycemic effect is primarily attributable to the presence of betalains. A potential interaction between betalains and other components in the model systems may be responsible for this effect. However, it was also observed that a greater complexity of the matrix (S6, FJ, BP) tends to reduce the inhibitory effect on the enzyme.

Currently, limited information is available to discuss the precise mechanism of action of betalains to block this enzyme. α-amylase consists of two regulation sites (Ca

+ binding, Cl

- binding) responsible for maintaining its structural integrity and could be related to activating its enzymatic function [

2,

49]. The enzyme also has an active site, made mainly of three amino acid residues (Asp 197, Asp 300, and Glu233) where it has been reported to have a strong interaction with other bioactive compounds (mainly polyphenols), reducing its enzymatic efficiency [

2,

26,

29].

Considering previous studies on polyphenols such as ellagic acid and epicatechin [

26,

29] which share structural similarities with betalains, particularly their double bond system, aromatic rings, and some polar regions, it can be postulated that betalains inhibit α-amylase activity through a competitive mechanism. This inhibition likely occurs due to betalains' affinity of the amino acids of the catalytic site as reported to other compounds with similar chemical structures such as benzene sulfonamides [

50]. Their polarity favors the formation of hydrogen bonds and Van der Waals forces, promoting stable binding, distorting the substrate, and reducing enzymatic efficiency. Additionally, in prickly pear juice (FJ), the components of the food matrix might enhance this effect by inducing changes at the enzyme's regulatory sites, thereby promoting the inhibition and stabilizing betalains during digestion, allowing them to exhibit a stronger inhibitory effect on α-amylase compared to recognized inhibitors such as acarbose.

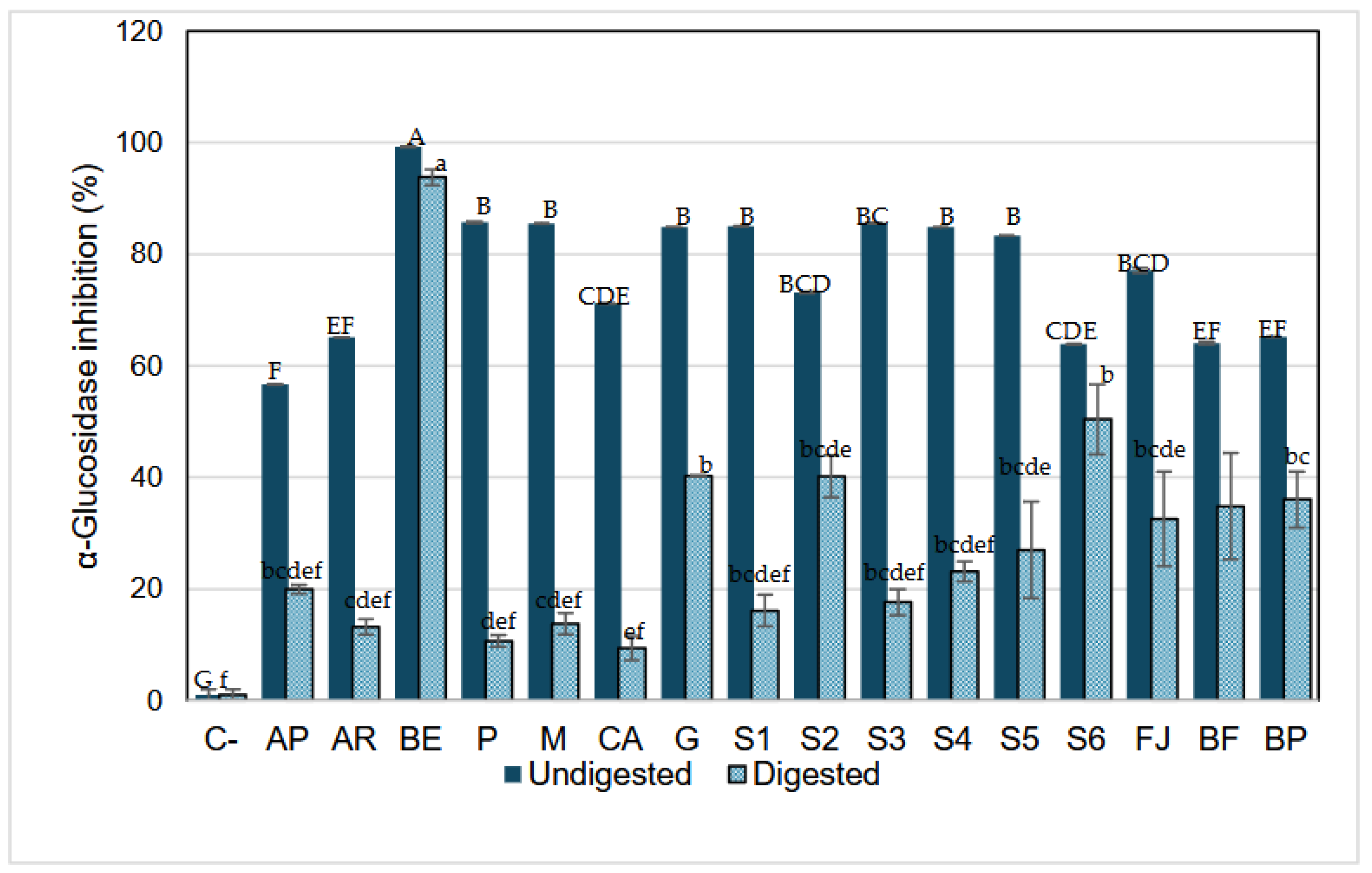

3.3.3.2. α-.Glucosidase Inhibition

α-glucosidase is a naturally occurring enzyme in the intestine, responsible for releasing glucose molecules from disaccharides previously broken down by the action of other enzymes, such as α-amylase, which cleaves α-glycosidic bonds. As shown in

Figure 5, acarbose (a drug known for its hypoglycemic effect due to its ability to inhibit α-glucosidase) shows a lower inhibition capacity against this enzyme (13% and 20% after digestion) compared to its effect on α-amylase and to the inhibition observed in model systems containing betalains, these results agreed with those reported by Virgen-Carrillo et al. [

26] likewise a significant decrease in the inhibition capacity of all samples was observed after

in vitro digestion.

However, BE has the greatest inhibition effect against α-glucosidase, followed by systems S2, S6, and JF that, in addition to betalains, have 13.7% of glucose (average amount present in fresh juice). This indicates that there could be an inhibition by product formulation but does not inherently lead to a decrease in blood sugar levels, that is because other mechanisms, such as the presence of free monosaccharides or alternative enzymatic pathways, can compensate for the partial inhibition of α-glucosidase. Thus, while elevated glucose levels in the intestine may suppress α-glucosidase activity, the overall effect on blood sugar regulation is influenced by the availability of alternative sugar sources and the efficiency of compensatory absorption pathways.

Also, the inhibition by product occurs when the accumulation of glucose, the enzyme's reaction product, slows or inhibits further enzymatic activity. Specifically, glucose competes with the substrate for binding at the enzyme's active site, reducing its ability to process additional substrates. This suggests that, within the context of digestion, excess glucose may naturally limit α-glucosidase activity as a regulatory mechanism to prevent an overload of glucose entering the bloodstream. Betalains might function as competitive inhibitors by mimicking the structure of the enzyme's natural substrates. In this scenario, betalains could occupy the enzyme's active site, preventing access to disaccharides such as maltose or sucrose, which are normally cleaved by α-glucosidase to release monosaccharides. Therefore, systems containing betalains and glucose may exhibit the highest effect in inhibiting this enzyme as a competitive inhibition. For instance, the S2 system (BE + glucose), as well as the more complex systems e.g., fresh juice (JF), formulated beverage (BF), and pasteurized beverage (BP), where glucose is predominant, could exhibit enhanced inhibition capacity of betalains against the enzymes. This is likely due to a higher predisposition to form glycosylated structures. As often observed for phenols, glycosylation drastically increases the stability of the compounds, mainly by impeding their oxidative degradation by blocking phenolic groups [

44,

51]. In nature, many natural products, especially the secondary metabolites of microbes and plants, are glycosylated, which changes metabolites' bioactivity and physiochemical properties. The addition of sugar moiety increases polarity and solubility and often results in improved stability of natural products [

52].

The inhibition by betalains extract (BE) could be by competition inhibition of betalains against glucose molecules, as reported by other bioactive compounds [

53]. Also, it has been reported that Vander Waals and hydrogen bonds are common bonds observed in all interactions between some bioactive compounds (p-coumaric acid, vanillin, hexahydrofarnesyl acetone, and phytol) and α-amylase and α-glucosidase. These changes observed in the bonds formed during interactions can be associated with the different amino acid content of each enzyme and its accessibility. As a result, these interactions of betalains with the enzymes can cause changes in the three-dimensional structure and loss of function, triggering its inhibition [

54].

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the significant impact of the food matrix on the bioaccessibility and hypoglycemic effect of betalains from red prickly pear juice. The presence of mucilage and pectin plays an important role in the food matrix because, despite being a polysaccharide with polar regions and interacting with betalains, it protects the structure of betalains through digestion. This protective effect is attributed to non-covalent interactions between betalains and matrix components, such as polysaccharides (mucilage and pectin), stabilizing betalains' structure and mitigating oxidative degradation. Moreover, betalains exhibited significant inhibitory effects on carbohydrate-digesting enzymes, α-amylase and α-glucosidase, with fresh juice (FJ) showing the highest inhibition rates (72% for α-amylase and 68% for α-glucosidase). This suggests that red prickly pear juice could be a natural alternative for managing postprandial glucose levels, potentially complementing dietary strategies for type 2 diabetes management. Red prickly pear juice, with its natural composition of betalains, mucilage, and pectin, emerges as a promising candidate for low-cost, sustainable functional food, especially in arid and semi-arid regions where Opuntia species thrive with minimal water requirements. Future research should focus on evaluating the hypoglycemic effects of red prickly pear juice in human trials, investigating processing techniques that minimize betalains' degradation while maintaining their bioactivity, and exploring the molecular interactions between betalains and matrix components to understand their stabilization and inhibitory mechanisms better.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, R.M.Y and V.R.S.J; methodology, V.R.S.J; M.L; U.S.J; software, R.M.Y; V.R.S.J; validation, V.R.S.J; M.L; formal analysis, R.M.Y; V.R.S.J; M.L; investigation, R.M.Y; resources, V.R.S.J; M.L; U.S.J data curation, R.M.Y; V.R.S.J; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.Y; V.R.S.J; writing—review and editing, R.M.Y; V.R.S.J; M.L; visualization, R.M.Y; V.R.S.J; M.L; supervision, V.R.S.J; M.L;” All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank CONAHCYT for supporting this work through the Ph.D. scholarship awarded to the author R.M.Y.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMS |

Aqueous Model Systems |

| BE |

Betalains Extract |

| BF |

Formulated Beverage |

| BP |

Pasteurized Beverage |

| JF |

Fresh red prickly pear juice |

| GPC |

Gel Permeation Chromatography |

| G |

Glucose |

| M |

Mucilage |

| P |

Pectin |

| CA |

Citric Acid |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Total betalains and their bioaccessibility percentage after in vitro digestion.

Table A1.

Total betalains and their bioaccessibility percentage after in vitro digestion.

| |

Initial phase (mg/g) |

Gastric phase (mg/g) |

Intestinal phase (mg/g) |

Bioaccessibility (%) |

Bioaccessibility (%) |

| Sample |

Betacyanins |

Betaxantins |

Total

betalains

|

Betacyanins |

Betaxantins |

Total

betalains

|

Betacyanins |

Betaxantins |

Total betalains |

Betacyanins |

Betaxanthins |

Total betalains |

| BE |

0.7700f

±0.000 |

0.6252g

±0.020 |

1.3952 |

0.1001d ±0.002 |

0.0828c ±0.001 |

0.1829 |

0.0695f ±0.001 |

0.0635f ±0.001 |

0.133 |

5.0a

±0.001 |

4.6a

±0.001 |

9.53a ±0.001 |

| S1 |

0.0883a

±0.002 |

0.0733b

±0.002 |

0.1616 |

0.0601b ±0.003 |

0.0543b ±0.002 |

0.1144 |

0.0426a ±0.001 |

0.0489d ±0.007 |

0.0915 |

26.4c ±0.001 |

30.2f ±0.002 |

56.61d ±0.002 |

| S2 |

0.0891a

±0.001 |

0.0717b

±0.000 |

0.1608 |

0.0554a ±0.000 |

0.0514a ±0.000 |

0.1068 |

0.0424a ±0.000 |

0.0455b ±0.000 |

0.0879 |

26.3c ±0.000 |

28.3d ±0.001 |

54.62c ±0.001 |

| S3 |

0.0837a

±0.000 |

0.0676a

±0.000 |

0.1513 |

0.0613b ±0.000 |

0.0528b ±0.000 |

0.1141 |

0.0434a ±0.000 |

0.0417a ±0.000 |

0.0851 |

28.7f ±0.000 |

27.6c ±0.001 |

56.25d ±0.001 |

| S4 |

0.0983b

±0.000 |

0.0792b

±0.000 |

0.1775 |

0.0983e ±0.003 |

0.0846d ±0.002 |

0.1829 |

0.0480c ±0.000 |

0.0485d ±0.001 |

0.0965 |

27.0d ±0.000 |

27.3c ±0.001 |

54.36c ±0.001 |

| S5 |

0.0875a

±0.002 |

0.0728b

±0.001 |

0.1603 |

0.0603b ±0.001 |

0.0535b ±0.000 |

0.1138 |

0.0459b ±0.000 |

0.0471c ±0.001 |

0.093 |

28.7f ±0.000 |

29.4e ±0.001 |

58.03e ±0.001 |

| S6 |

0.1014c

±0.000 |

0.0825c

±0.000 |

0.1839 |

0.1004d ±0.003 |

0.0929e ±0.002 |

0.1933 |

0.0508d ±0.000 |

0.0534e ±0.001 |

0.1042 |

27.6e ±0.007 |

29.0e ±0.001 |

56.67d ±0.001 |

| FJ |

0.1024c

±0.001 |

0.1144d

±0.000 |

0.2168 |

0.0883c ±0.000 |

0.0871d ±0.001 |

0.1754 |

0.0585e ±0.000 |

0.0697g ±0.001 |

0.1282 |

27.0d ±0.000 |

32.1h ±0.001 |

59.13f ±0.001 |

| BF |

0.1884d

±0.001 |

0.1599e

±0.000 |

0.3483 |

0.1887e ±0.002 |

0.1321f ±0.001 |

0.3208 |

0.0929g ±0.001 |

0.1105i ±0.002 |

0.2034 |

26.7cd ±0.002 |

31.7g ±0.003 |

58.40e ±0.003 |

| BP |

0.2803e

±0.007 |

0.2402f

±0.005 |

0.5205 |

0.1730e ±0.016 |

0.1531f ±0.000 |

0.3261 |

0.0914g ±0.000 |

0.1076h ±0.002 |

0.199 |

17.6b ±0.007 |

20.7b ±0.003 |

38.23b ±0.004 |

References

- Kumari, S.; Kumar, D.; Mittal, M. An Ensemble Approach for Classification and Prediction of Diabetes Mellitus Using Soft Voting Classifier. International Journal of Cognitive Computing in Engineering 2021, 2, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi, O.M.; Gyebi, G.A.; Saheed, A.; Paul, J.; Nwaneri-Chidozie, V.; Olorundare, O.; Adebayo, J.; Koketsu, M.; Aljarba, N.; Alkahtani, S.; et al. Inhibition Mechanism of Alpha-Amylase, a Diabetes Target, by a Steroidal Pregnane and Pregnane Glycosides Derived from Gongronema Latifolium Benth. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz, Z.; Ali, M.N.; Qureshi, Z.; Mohsin, M. In Vitro Investigation and Evaluation of Novel Drug Based on Polyherbal Extract against Type 2 Diabetes. J Diabetes Res 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovinskaia, O.; Wang, C.K. The Hypoglycemic Potential of Phenolics from Functional Foods and Their Mechanisms. Food Science and Human Wellness 2023, 12, 986–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, O.J.; Scholle, J.M.; Talwar, M.; Coleman, C.I. Effect of Noninsulin Antidiabetic Drugs Added to Metformin Therapy on Glycemic Control, Weight Gain, and Hypoglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA 2010, 14, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, A.; Tsang, C.; Tiss, A.; Bahorun, T.; Arefanian, H.; Barake, R.; Khadir, A.; Tuomilehto, J. Functional Foods and Lifestyle Approaches for Diabetes Prevention and Management. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Y.; Durmaz, L.; Taslimi, P.; Gulçin, İ. Antidiabetic Properties of Dietary Phenolic Compounds: Inhibition Effects on α-Amylase, Aldose Reductase, and α-Glycosidase. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 2019, 66, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakalukwa, R.; Amen, Y.; Nagata, M.; Shimizu, K. Postprandial Hyperglycemia Lowering Effect of the Isolated Compounds from Olive Mill Wastes - An Inhibitory Activity and Kinetics Studies on α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase Enzymes. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 20070–20079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatakrishnan, K.; Chiu, H.F.; Wang, C.K. Popular Functional Foods and Herbs for the Management of Type-2-Diabetes Mellitus: A Comprehensive Review with Special Reference to Clinical Trials and Its Proposed Mechanism. J Funct Foods 2019, 57, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi, E.; Mazloum-Ravasan, S.; Yu, J.S.; Ha, J.W.; Hamishehkar, H.; Kim, K.H. Therapeutic Application of Betalains: A Review. Plants 2020, 9, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhananjayan, I.; Kathiroli, S.; Subramani, S.; Veerasamy, V. Ameliorating Effect of Betanin, a Natural Chromoalkaloid by Modulating Hepatic Carbohydrate Metabolic Enzyme Activities and Glycogen Content in Streptozotocin – Nicotinamide Induced Experimental Rats. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2017, 88, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandía-Herrero, F.; Escribano, J.; García-carmona, F. Biological Activities of Plant Pigments Betalains. Food Sci Nutr 2014, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Thawkar, B.; Dubey, S.; Jadhav, P. Pharmacological Potentials of Betalains. J Complement Integr Med 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves de Souza, R.L.; Santana, M.F.S.; de Macedo, E.M.S.; de Brito, E.S.; Correia, R.T.P. Physicochemical, Bioactive and Functional Evaluation of the Exotic Fruits Opuntia Ficus-Indica AND Pilosocereus Pachycladus Ritter from the Brazilian Caatinga. J Food Sci Technol 2015, 52, 7329–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Maqueo, A.; García-Cayuela, T. Inhibitory Potential of Prickly Pears and Their Isolated Bioactives against Digestive Enzymes Linked to Type 2 Diabetes and Inflammatory. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, A.; Ulrih, N.P. An Overview of Herbal Products and Secondary Metabolites Used for Management of Type Two Diabetes. Front Pharmacol 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čepo, D.V.; Radić, K.; Šalov, M.; Turčić, P.; Anić, D.; Komar, B. Food (Matrix) Effects on Bioaccessibility and Intestinal Permeability of Major Olive Antioxidants. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.I.; Saraiva, J.M.A.; Vicente, A.A.; Moldão-martins, M. Methods for Determining Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility of Bioactive Compounds and Nutrients. In Innovative Thermal and Non-Thermal Processing, Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds; Elsevier Inc., 2019; pp. 23–54 ISBN 9780128141748.

- Gómez-Maqueo, A.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Cano, M.P. Release Mechanisms of Bioactive Compounds in Fruits Submitted to High Hydrostatic Pressure: A Dynamic Microstructural Analysis Based on Prickly Pear Cells. Food Research International 2020, 130, 108909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, P.; Guerrero-Rubio, M.A.; Henarejos-Escudero, P.; García-Carmona, F.; Gandía-Herrero, F. Health-Promoting Potential of Betalains in vivo and Their Relevance as Functional Ingredients: A Review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2022, 122, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel-Sánchez, M.; García-Cayuela, T.; Gómez-Maqueo, A.; García, H.S.; Cano, M.P. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Stability, Bioaccessibility and Potential Biological Activities of Betalains and Phenolic Compounds in Cactus Berry Fruits (Myrtillocactus geometrizans). Food Chem 2020, 128087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Pan, Y. Influence of Food Matrix and Food Processing on the Chemical Interaction and Bioaccessibility of Dietary Phytochemicals: A Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 6421–6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Arista, C.; Roman-Guerrero, A.; Oidor-Chan, V.H.; Díaz de León-Sánchez, F.; Álvarez-Ramírez, E.L.; Pelayo-Zaldívar, C.; Sierra-Palacios, E. del C.; Mendoza-Espinoza, J.A. Chemical Characterization, Antioxidant Capacity, and Anti-Hyperglycemic effect of Stenocereus stellatus Fruits from the Arid Mixteca Baja Region of Mexico. Food Chem 2020, 328, 127076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.C.P.; Lopes, N.B.; Augusto, F.A.; Pioli, R.M.; Machado, C.O.; Freitas-Dörr, B.C.; Suffredini, H.B.; Bastos, E.L. Phenolic Betalain as Antioxidants: Meta Means More. Pure and Applied Chemistry 2020, 92, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala Bendezú, T. Proyecto de Instalación de Una Planta de Procesamiento de Tuna En El Distrito de Chincho Provincia de Angaraes Departamento de Huancavelica, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San marcos, 2008.

- Virgen-Carrillo, C.A.; Valdés Miramontes, E.H.; Fonseca Hernández, D.; Luna-Vital, D.A.; Mojica, L. West Mexico Berries Modulate α-Amylase, α-Glucosidase and Pancreatic Lipase Using in vitro and In Silico Approaches. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Murillo, A.C.; Urías-Silvas, J.E. Fermented Coconut Jelly as a Probiotic Vehicle, Physicochemical and Microbiology Characterisation during an in Vitro Digestion. Int J Food Sci Technol 2023, 58, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojica, L.; Gonzalez, E.; Mejia, D.; Granados-silvestre, M.Á.; Menjivar, M. Evaluation of the Hypoglycemic Potential of a Black Bean Hydrolyzed Protein Isolate and Its Pure Peptides Using in silico, in vitro and in vivo Approaches. J Funct Foods 2017, 31, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwagunwa, O.A.; Alashi, A.M.; Aluko, R.E. Inhibition of the in vitro Activities of α-Amylase and Pancreatic Lipase by Aqueous Extracts of Amaranthus Viridis, Solanum macrocarpon and Telfairia occidentalis Leaves. Front Nutr 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merck Enzymatic Assay of α-Amylase (EC 3.2.1.1).

- Wickham, Hadley. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2016.

- Wickham, H.; Romain, F.; Lionel, H.; Kirill, M.; Davis, V. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation 2023.

- Graves, S.; Hans-Peter, P.; Sundar, D.-R. MultcompView: Visualizations of Paired Comparisons 2024.

- Platzer, M.; Kiese, S.; Herfellner, T.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Miesbauer, O.; Eisner, P. Common Trends and Differences in Antioxidant Activity Analysis of Phenolic Substances Using Single Electron Transfer Based Assays. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandía-Herrero, F.; Escribano, J.; García-Carmona, F. The Role of Phenolic Hydroxy Groups in the Free Radical Scavenging Activity of Betalains. J Nat Prod 2009, 72, 1142–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandía-Herrero, F.; Escribano, J.; García-Carmona, F. Purification and Antiradical Properties of the Structural Unit of Betalains. J Nat Prod 2012, 75, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandía-Herrero, F.; Escribano, J.; García-Carmona, F. Structural Implications on Color, Fluorescence, and Antiradical Activity in Betalains. Planta 2010, 232, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Rubio, M.A.; Escribano, J.; García-Carmona, F.; Gandía-Herrero, F. Light Emission in Betalains: From Fluorescent Flowers to Biotechnological Applications. Trends Plant Sci 2020, 25, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igual, M.; Fernandes, Â.; Dias, M.I.; Pinela, J.; García-Segovia, P.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; Barros, L. The In vitro Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion Affects the Bioaccessibility and Bioactivity of Beta vulgaris Constituents. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Palestina, C.U.; Aguirre-Mancilla, C.L.; Raya-Pérez, J.C.; Ramírez-Pimentel, J.G.; Gutiérrez-Tlahque, J.; Hernández-Fuentes, A.D. The Effect of an Edible Coating with Tomato Oily Extract on the Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Garambullo (Myrtillocactus geometrizans) Fruits. Agronomy 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska-Bartosz, I.; Bartosz, G. Biological Properties and Applications of Betalains. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesoriere, L.; Fazzari, M.; Angileri, F.; Gentile, C.; Livrea, Maria, A. In vitro Digestion of Betalainic Foods . Stability and Bioaccessibility of Betaxanthins and Betacyanins and Antioxidative Potential of Food Digesta. J Agric Food Chem 2008, 56, 10487–10492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.M.; Amaral, R.A.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cardoso, S.M.; Saraiva, J.A. Effect of High-Pressure and Thermal Pasteurization on Microbial and Physico-Chemical Properties of Opuntia ficus-indica Juices. Beverages 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glitz, C.; Dyekjær, J.D.; Vaitkus, D.; Babaei, M.; Welner, D.H.; Borodina, I. Screening of Plant UDP-Glycosyltransferases for Betanin Production in Yeast. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I. Plant Betalains: Safety, Antioxidant Activity, Clinical Efficacy, and Bioavailability. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2016, 15, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimen, I.B.; Najar, T.; Abderrabba, M. Chemical and Antioxidant Properties of Betalains. J Agric Food Chem 2017, 65, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S.A.; Baumgartner, M.T. Betanidin p KaPrediction Using DFT Methods. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 13751–13759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, T.; Martinez-villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Wiczkowski, W.; Peñas, E.; Baczek, N.; Zielinski, H. The Effect of Processing and in vitro Digestion on the Betalain Profile and ACE Inhibition Activity of Red Beetroot Products. J Funct Foods 2019, 55, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payan, F. Structural Basis for the Inhibition of Mammalian and Insect α-Amylases by Plant Protein Inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 2004, 1696, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askarzadeh, M.; Azizian, H.; Adib, M.; Mohammadi-Khanaposhtani, M.; Mojtabavi, S.; Faramarzi, M.A.; Sajjadi-Jazi, S.M.; Larijani, B.; Hamedifar, H.; Mahdavi, M. Design, Synthesis, in vitro α-Glucosidase Inhibition, Docking, and Molecular Dynamics of New Phthalimide-Benzenesulfonamide Hybrids for Targeting Type 2 Diabetes. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slámová, K.; Kapešová, J.; Valentová, K. “Sweet Flavonoids”: Glycosidase-Catalyzed Modifications. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.M.; Liu, J.H.; Wu, H.; Wang, B. Bin; Zhu, H.J.; Qiao, J.J. Glycosyltransferases: Mechanisms and Applications in Natural Product Development. Chem Soc Rev 2015, 44, 8350–8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, S.T.; Yang, E.Y.; Chae, S.Y.; Song, M.; Lee, J.; Cho, M.C.; Jang, S. Alpha Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities of Plants with Focus on Common Vegetables. Plants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üst, Ö.; Yalçin, E.; Çavuşoğlu, K.; Özkan, B. LC–MS/MS, GC–MS and Molecular Docking Analysis for Phytochemical Fingerprint and Bioactivity of Beta vulgaris L. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).