Introduction

The collaborative research hierarchy is commonly represented as a pyramid with three tiers. These tiers include multidisciplinary research, which is generally regarded as the least cooperative and least integrated type of collaborative research (Dalton et al., 2022); interdisciplinary research (IDR), which places more emphasis on researcher cooperation and a degree of centralised control or purpose; and transdisciplinary research, which is thought to be the most integrated type of collaborative research and probably involves social, corporate, and political actors from outside the research process (Dalton et al., 2022; van Rijnsoever & Hessels, 2011). In IDR, "researchers from various disciplines come together at the boundaries and interfaces of their disciplines, and even cross boundaries to form new disciplines (van Rijnsoever & Hessels, 2011)." The main way that IDR differs from other types of collaborative research is that it uses a synergistic blend of discipline-specific perspectives to address a shared issue (Daniel et al., 2022).

Research conducted by teams or people that incorporates views, concepts, theories, methods, methodologies, information, and data from two or more bodies of specialised knowledge or research practice is known as IDR (Daniel et al., 2022; Nyahunda & Tirivangasi, 2021; Porter et al., 2006). Its goal is to address issues whose answers fall outside the purview of a particular discipline of study or to further basic understanding (Porter et al., 2006).

IDR is defined by the Roadmap, a new strategy plan for future National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding, as research that combines the analytical capabilities of two or more frequently divergent scientific fields to address a particular biological problem (Aboelela et al., 2007; Porter et al., 2008). To better address complicated health issues like pain and obesity, for example, behavioural scientists, molecular biologists, and mathematicians may pool their research instruments, methodologies, and technology (Aboelela et al., 2007).

IDR can involve a variety of activities, such as: Using concepts, models, or paradigms, tools, and methodologies from other domains; interfield theories (for example, evolution, atomic structure); Frontier problem-solving, particularly complicated social issues that need a variety of information sources (Porter et al., 2006). Furthermore, it is frequently believed that IDR is too hard, time-consuming, difficult to publish, and tough to obtain funding (Brown et al., 2019).

Why Do Interdisciplinary Research?

Many of the complex issues society is presently dealing with (such as those pertaining to health care, mobility, or the environment) call for creative solutions that integrate information from several scientific fields. It is possible to accomplish these combinations through Interdisciplinary research (van Rijnsoever & Hessels, 2011). Globally, every nation ratified the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 (Brown et al., 2019; Carlsen & Bruggemann, 2022). The range of subjects and issues they address is only one of the many reasons the aims are so ambitious (Brown et al., 2019). It seems commonly known that achieving the SDGs calls for solutions-focused, IDR that can bridge conventional gaps across disciplines and blend high-calibre research with pertinent effect (Brown et al., 2019).

Furthermore, traditional gaps in vocabulary, strategy, and technique may be gradually closed by involving disciplines that don't seem to be connected (Aboelela et al., 2007). When obstacles to possible cooperation are eliminated, a genuine convergence of ideas can occur, which can expand the scope of research into biological issues, provide new and potentially surprising findings, and even lead to the emergence of new hybrid disciplines with higher levels of analytical sophistication (Aboelela et al., 2007).

Importance of IDR in Africa

One of the greatest long-term challenges to human culture is climate change, which has been called a "wicked problem" due to its complexity and resistance to easy, one-time fixes (Gomes et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2016). Such wicked challenges are characterised by the requirement to use research that integrates techniques from several different fields (Xu et al., 2016). Improved understanding, technique, and cooperation amongst disciplines—such as soil science, marine science, atmospheric sciences, plant physiology, ecosystem science, hydrology, and computer science—are necessary for the study of climate change (Xu et al., 2016).

With respect to public health, the greatest Ebola epidemic ever documented occurred in Guinea in 2013, the first nation in West Africa to suffer the latest outbreak of the Ebola virus disease (EVD), which collectively caused over 28,000 cases and 11,000 fatalities across 10 countries (Calnan et al., 2012). Despite the massive mobilisation of staff, tools, and resources by national and international institutions, the pandemic took a long time to contain (Calnan et al., 2012). The need for IDR to study the epidemic's social aspects, the policy response to it, the communities' responses to the response, and how these elements interacted with the virus's biological transmission, physical containment strategies, and community medical care is also becoming more widely acknowledged (Calnan et al., 2012).

Even though Africans contribute little to the causes of climate change, its unstable effects are having a negative influence on African populations. Because of this, climate change has turned into a catastrophe affecting human rights, development, the economy, psychology, health, poverty, and war (Levy & Patz, 2015; Nyahunda & Tirivangasi, 2021). It is well acknowledged that interdisciplinarity is a leading strategy for integrating several disciplines to fully understand the intricacies of environmental degradation brought on by human behaviour and activities (Nyahunda & Tirivangasi, 2021). Espousing interdisciplinary approaches will be of great value to Africa's challenges such as climate change. Consequently, the next section explores the challenges facing IDR in Africa.

Challenges Facing IDR in Africa

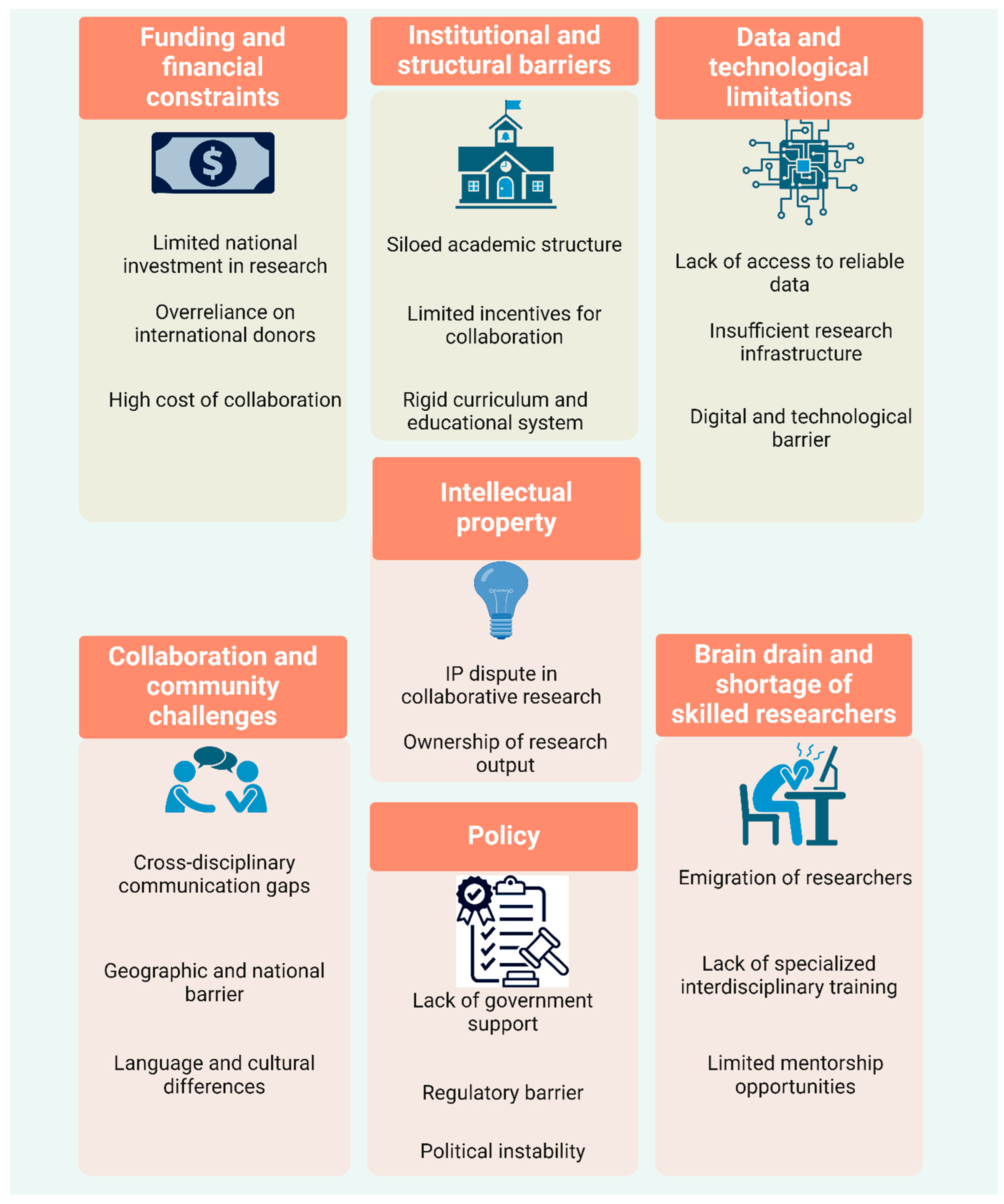

IDR in Africa faces diverse challenges (

Figure 1) classified into Funding and Financial Constraints, Institutional and Structural Barriers, Data and Technological Limitations, Policy and Governance Issues, Brain Drain and Shortage of Skilled Researchers, and IP and Ownership Issues. These are explored in this section.

Funding and Financial Constraints

To successfully implement IDR, adequate funding would be needed. That is to say that among many other factors, financial constraints play a key role in determining the landscape of interdisciplinary research. These financial constraints could arise from a number of issues like limited national investment in research and development, an overdependence on international funding, and the high costs of collaboration. These factors can frustrate IDR initiatives thereby resulting in hindering the potential to solve complex societal issues.

The lack of national investment in research and development (R&D) in African nations is one of the main obstacles to IDR in Africa. Many African governments allocate little funding towards R&D which does not encourage IDR (Simpkin et al., 2019). In Kenya for example, total government financing for research is insufficient to support the wide IDR projects, despite the efforts of the Kenya's National Research Fund (Otieno-Omutoko, 2017).

The importance of government-funded research and development (R&D) for Africa's future has been a focal point of discussion among experts, stressing that without sufficient national investment, African countries would struggle to support critical research initiatives and rely on external sources, which may not align with local priorities. Thus, hampering the continent's ability to address its unique challenges and achieve self-sufficiency (Adepoju, 2022). Because IDR projects often require more resources due to their complexity and the need to coordinate across multiple fields of expertise, the absence of dedicated financial support exacerbates the situation, as such projects are often overlooked in favour of single-discipline studies (Bromham et al., 2016).

Africa's heavy reliance on foreign donors for research financing is another major issue which often exacerbates these challenges facing IDR (Confraria & Wang, 2020). A consequence of this is that African researchers may not receive financing that is in line with local research interests due to specific agendas of international donors (Jaworski et al., 2020). For instance, rather than addressing particular local challenges, donor-driven research instead concentrates on global issues (Kok et al., 2017). This misalignment can limit the relevance and applicability of research findings by directing attention toward initiatives that do not promote African scholars' capacity to adequately address the urgent needs of the local communities (El Hajj et al., 2020).

Due to the complexity of IDR (Dalton et al., 2022), it often requires high costs related to data collection, travel, and combination of several approaches (Menyeh, 2024). Collaboration across different domains typically demands more financial resources which may result in higher operational and logistical expenses. The burden created by these high costs may discourage researchers from exploring interdisciplinary approaches, especially in resource limited settings where academics are often expected to self-finance or rely on external money that may not fully cover all expenses (Fon, 2023). The lack of administrative frameworks and efficient research management systems needed to foster IDR in many institutions in Africa also contributes to high cost of collaboration (Ogega & Matta, 2023). This shortcoming impacts on the overall quality and output of the research as well as the capacity to obtain funding.

Institutional and Structural Barriers

One of the primary challenges facing IDR in Africa is the rigid, discipline-centric organisation of universities and research institutions. Many African academic institutions are structured around strict disciplinary boundaries, with faculties and departments operating independently. This siloed approach limits cross-disciplinary collaboration, making it difficult for researchers from different fields to work together on complex, real-world problems. The commencement of the current millennium saw an increased introduction of interdisciplinary education programmes at higher education institutions translating to increased IDR (Schmidt et al., 2012; Vázquez et al., 2011). However, most of these interdisciplinary programmes and research were based in developed countries. Though pockets of African universities have incorporated interdisciplinary curricula (Esler et al., 2016), many still maintain traditional curricula that do not adequately integrate interdisciplinary learning. Especially in developing countries, the disciplinary divide in universities is well established in literature (Kinzig, 2001). Consequently, students are trained within narrow disciplinary frameworks, limiting their exposure to methodologies, perspectives, and problem-solving approaches from other fields (Mourshed et al., 2013; Muir & Schwartz, 2009). As a result, future researchers may lack the requisite skills to solve complex problems in a dynamic world that requires interdisciplinary approach and engagement with diverse stakeholders/disciplines (Palmer et al., 2005; Raworth, 2012). On the other hand, Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) pedagogies presents an excellent opportunity for interdisciplinary education which could translate to IDR. However, this opportunity seems not maximised as most COIL programmes seem specific subject-oriented in design. It is debatable that intracultural interactions, digital literacy, communication skills, and receptiveness to knowledge pluralisation which are the benefits of COIL programmes presents interdisciplinary perspective (Wimpenny & Orsini-Jones, 2020). However, these could be termed as byproducts of this pedagogic approach while the curriculum content remains subject/discipline specific. The absence of interdisciplinary training at undergraduate and postgraduate levels means that students do not develop the mindset or competencies required for collaborative research. Without educational reforms, African researchers will continue to face difficulties in bridging knowledge gaps across disciplines. Additionally, existing administrative frameworks do not always support or facilitate interdisciplinary engagements. Many funding opportunities, research grants, and institutional policies are designed for single-discipline projects or prioritise discipline-specific studies, making it challenging for interdisciplinary initiatives to secure necessary resources. This seems obtainable in both developed and developing countries’ research landscape. For instance, in the UK, in what was labelled “shaping capability”, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (ESPRC) in 2011 announced subjects within its portfolio that it will focus to either grow, maintain, or reduce funding for interdisciplinary research (Grove, 2018). Moreover, over the last couple of years, the funding calls put out by Research Councils in the UK seems more ‘directed’, topic oriented. There has also been a tilt in balance in Research Council funding with more funding going into applied research as opposed to fundamental research (Bentley et al., 2015). Furthermore, there has been a drive towards economic impact-oriented research funding especially in the current economic crisis, hence, more funding seems to be channelled to research with governmental or societal impact (Singhania & Swami, 2024). It could be deducible from these discussions that often than not, topic-oriented, applied research, and impact-oriented research are disciplinary in nature. While very little of these natures of research incorporate interdisciplinary approaches, especially applied and impact-oriented research, there is need for funding bodies to favour research projects incorporating interdisciplinary approaches. These reinforce the argument about most funding bodies and policies being in favour of subject-specific or single-disciplined projects. This minimal financial and institutional incentives discourage researchers from venturing beyond their disciplines, further perpetuating academic silos. Without deliberate efforts to integrate disciplines, innovative research that requires multiple perspectives remains stifled.

Academic reward systems in Africa often fail to acknowledge or support interdisciplinary research. Promotion, tenure, and professional recognition are traditionally based on individual contributions within a single discipline. Researchers who engage in interdisciplinary projects may struggle to gain career advancement since their contributions do not always align with existing evaluation criteria. Without reforms in academic evaluation systems, IDR will continue to be undervalued.

Data and Technological Limitations

Over the last few years, IDR (a scientific approach that seeks to integrate information, data, techniques, tools, perspectives, concepts or theories from two or more disciplines or bodies of specialised knowledge), has gained relevance in Africa in tackling complex societal problems, including climate change, food systems, poverty, and health disparities (Gomes et al., 2024; Otieno-Omutoko, 2017; Vajaradul et al., 2021). Besides, this approach to scientific enquiry has helped researchers to gain invigorating perceptions, creative solutions, and innovative breakthroughs that would not have been feasible through the traditional, discipline-specific approaches. Notwithstanding these strides, most African scientists are faced with hefty challenges, especially those regarding data and technological limitations, in their pursuit of IDR (Agbona et al., 2023; Mwelwa et al., 2020; Obiora et al., 2024).

The intricacies involved in obtaining comprehensive and reliable datasets across diverse disciplines and the management of such data, has been a major challenge facing interdisciplinary researchers in Africa (Chawinga & Zinn, 2019; Mosha & Ngulube, 2024). In most African countries, there is the lack of well-established research data management plans or systems, and this often leads to incomplete, inaccurate, outdated and lost data (Patterton et al., 2018). In many instances, this challenge impedes researchers’ efficiency in producing evidence-based research and this can lead to questions relating to the validity and reliability of such findings. This challenge also involves instances where even when the data is available, access, in most instances is restricted, because of poor internet infrastructure and restrictive sharing policies (Bezuidenhout et al., 2017). The lack of standardised regulation in data collection and management can lead to other challenges in matching and incorporating evidence across different studies and disciplines. This can frustrate the design of thorough solutions to complex problems, which is a principal aim of interdisciplinary research.

As well, most scientists involved in IDR in Africa are confronted with the challenge of inadequacies of contemporary research facilities, laboratories, and technology to support their investigations (Horton et al., 2018; Osabutey & Jackson, 2019). In Africa, many research institutions still struggle with getting access to modern equipment, software and digital tools, essential for undertaking trailblazing research (Hamdi et al., 2021; Inzaule et al., 2021). Apart from hindering African interdisciplinary scientists’ efforts to effectively collect and analyse data, this infrastructural divide, also affects their capacity to collaborate and even publish in high indexed journals, affecting the visibility and discoverability of their research outputs.

In spite of the critical role of IDR in Africa, challenges like unreliable data, low investments in research infrastructure, and restricted access to modern technologies continue to impede the effectiveness of using IDR to address complex societal problems. Overcoming these limitations is vital to exploiting the maximum potential of IDR in Africa, leading to the promotion of evidence-based solutions to drive sustainable development.

Collaboration and Communication Challenges

Africa faces a lot of complex problems, from health crises and environmental issues to the need for economic growth and technological progress. Tackling these challenges effectively often requires us to look beyond single, isolated fields of study. Combining different fields of knowledge can lead to much more comprehensive and creative solutions. This interdisciplinary way of thinking is incredibly promising for Africa's development and policymaking. However, it's often a real struggle to get people from different backgrounds to work together effectively and make a tangible difference. There are lots of obstacles in the way.

One of the biggest hurdles for researchers working across different fields in Africa is simply the difficulty of communication (Igbinenikaro et al., 2024). Different disciplines often have their own specialised vocabulary, preferred methods, and unique perspectives, which can easily lead to misunderstandings and make it hard to share research findings effectively (Doyle et al., 2024). A core problem is the lack of a shared understanding of fundamental concepts and goals (Nordgreen et al., 2021). For example, in e-mental health research, a computer scientist, a psychologist, and a healthcare professional might all have very different ideas about what makes an intervention "successful" (Nordgreen et al., 2021). This kind of "language barrier" can cause misinterpretations and hamper the development of coherent research strategies. We need to establish clear communication channels, foster a collaborative environment, and encourage mutual respect for each discipline's approach (Igbinenikaro et al., 2024).

Another major challenge stems from the diverse ways different fields approach research and interpret data. A study on natural hazards in New Zealand, involving scientists, professionals, and the public, found that scientists tended to focus on complex risk models, while the public was more concerned with immediate safety and control (Doyle et al., 2024). These differing perceptions of risk can lead to communication breakdowns and a lack of trust in scientific research, ultimately limiting its impact on policy and practice. Similar issues can arise in Africa, where researchers from various disciplines bring their own, sometimes incompatible, methodologies. Research on digital health for mothers and children in Africa, for example, has been published across various fields, including public health, social sciences, and human-computer interaction (Till et al., 2023), making it difficult to synthesise the knowledge and develop a comprehensive understanding.

Finally, a lack of cross-disciplinary training and skills can hinder collaborative research efforts in Africa. Researchers in global health programmes, for instance, often have different skill sets depending on their backgrounds (e.g., clinical, social, health systems, economics, and policy) (Ding et al., 2022). Providing training in cross-disciplinary research methods and communication strategies can help bridge these gaps and promote more effective collaboration (Nordgreen et al., 2021). This involves creating opportunities for researchers to learn from one another, understand the strengths and limitations of different disciplinary perspectives, and collaboratively develop research goals and methods (Igbinenikaro et al., 2024).

Furthermore, Language and cultural diversity present significant challenges to interdisciplinary research. In Africa, over 2,000 languages are spoken which can impede effective communication among researchers from different backgrounds, as well as the communities they study (Omutoko et al., 2024). However, the use of a dominant language, such as English, can exclude non-fluent participants leading to biased data collection and misinterpretation of local knowledge (Galindo et al., 2025). While translating for understanding and collaboration, there will likely be loss of the variation in cultural expression leading to barriers in IDR. Cultural diversity also affects the methodologies used in research. Standard research practices developed in certain geographical location may not be culturally appropriate in other settings in Africa (Ng, 2023; Oluka, 2024). For example, direct questioning might be seen as intrusive in some cultures, while in others, participants may be hesitant to share information with outsiders (Ng, 2023; Oluka, 2024). Additionally, the interpretation of research data is often influenced by the cultural background of the researchers, potentially introducing biases.

Policy and Governance Issues

IDR is vital in enabling researchers view research questions or a hypothesis from different disciplines and (or) perspectives. Ultimately this generates relevant data viewed by different experts though varied lens rather than a single discipline. This is relevant in providing baseline data or recommendations for real world problems accentuating the interconnectedness of existing societal problems or phenomena (Aboelela et al., 2007). With its infinite list of benefits, fostering, promoting and maintaining research between two or more disciplines or bodies of specialised knowledge is not thriving as one would expect in Africa. This hinges on numerous challenges (Kafatos, 1998) with a few expounded further below.

Researchers and policy makers alike care about the wellbeing of the populace, however, they often have different priorities which have led to a neglect in enacting policies that foster research across disciplines. More often than not, policy makers focus on programmes that improve their political record, interest or considerations. They do not recognise how effective the use of research findings can provide sustainable and evidence-based solutions to societal problems and effectively enhance policy development (Oliver et al., 2014). Budgetary restrictions, lack of opportunities for engagement and communication between researchers and policy makers which may be due to inaccurate reporting of research finding or use of complex technical jargons may also be accountable in hindering policy makers from the passing substantial and effective policies supporting IDR (Khomsi et al., 2024).

Acquiring ethical approval from a committee or board before the start of any project is crucial owing to the fact that this demonstrates adherence to the accepted standards and ethical principles of the research process. However, the approval processes of research proposal involving different disciplines faces complex bureaucratic and documentation red tape. Policies regulating such collaborations are fragmented with the finalisation of the approval process time-consuming. Other factors like incoherent feedback from reviewers due to them lacking the expertise in various disciplines may also contribute to decreasing the motivation for researchers wanting to be involved in IDR (Dadipoor et al., 2019).

Since the 1960s, there have been significant numbers of coup d’états within African countries that achieved their independence, and this is still prevalent in certain regions of the continent (Mbaku, 1988). More often than not, some factors responsible for political instability in Africa include weak governance, electoral disputes, ethnic tensions or corruption. Funding and timelines from funding organisations are usually time bound due to the unpredictable nature of politically instigated unrest and its devasting effect these have on growth and development, as well as the ability to interfere with research collaborations or activities, IDR remains limited or untapped in regions with potentially high political and social instability.

Brain Drain and Shortage of Skilled Researchers

The complex, multifaceted issues facing Africa could be effectively addressed by interdisciplinary research. However, several obstacles, most notably the brain drain and lack of qualified researchers, make it difficult for the continent to support and maintain this kind of study.

IDR in Africa is continually confronted by the brain drain phenomenon, where highly qualified researchers frequently depart the continent in quest of better economic prospects, better infrastructure, and more favourable working conditions, especially those trained in specialised subjects that call for interdisciplinary collaboration (Adetayo, 2010). According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Africa loses over 20,000 professionals to wealthy countries each year, and this trend is made worse by global disparities in research funding and resource allocation (Kariuki & Kay, 2017).

The number of scholars with the knowledge and cultural background required to tackle Africa's complex problems is greatly diminished by emigration. For instance, there are deficits in research capacity due to a significant professional exodus in the healthcare industry (Ogilvie et al., 2007). Although their movement advances global science, African institutions find it difficult to retain qualified individuals who could otherwise spearhead creative, context-specific research projects.

The ability of researchers to successfully traverse several fields of knowledge is essential for interdisciplinary research. However, there aren't many specialist training programmes in Africa that are designed to give researchers the multidisciplinary methodologies and teamwork skills they need (Roshania et al., 2023). There are few courses or initiatives that encourage cross-disciplinary problem-solving at most African colleges, which still maintain strict disciplinary boundaries (Esler et al., 2016).

Lack of this kind of training keeps a research gap that combines knowledge from several fields, which is essential for solving complicated social issues including food shortages, public health emergencies, and climate change. Initiatives that need cooperation between environmental scientists, public health specialists, and economics, for example, are frequently hindered because there aren't enough scholars skilled at negotiating these intersections. Thus, the sluggish development of creative solutions suited to African situations is a result of the scarcity of interdisciplinary training.

A key component of academic and scientific progress is mentoring. However, there aren't many older researchers with interdisciplinary expertise in Africa's academic landscape to guide younger researchers (Kumwenda et al., 2017). Further, many prominent academics and researchers in African institutions have specialised in specific fields of study and are not familiar with collaborative, interdisciplinary frameworks (Otieno-Omutoko, 2017).

The development of early-career researchers is hampered by this mentorship gap, as they are frequently left to handle the challenges of IDR alone. A lack of succession planning results from inadequate mentoring as well, since the next generation does not acquire the knowledge and abilities required to promote interdisciplinary collaboration. Research funding and publication in high-impact journals are critical for career advancement and institutional prestige, and studies indicate that researchers who have access to good mentorship are more likely to achieve these goals (Gutierrez et al., 2021).

Intellectual Property (IP) and Ownership Issues

Research indicates that the topic of IP has become more significant in inter-firm research and development partnerships (Bader, 2007, 2008). The fact that the percentage of jointly held patents has progressively grown over the past several decades serves as proof of this. However, it can be challenging to address IP concerns in research and development partnerships early on because the partners may not fully understand their future circumstances or may not choose to divulge all expectations (Bader, 2007). There are very few scholarly findings on managing IP in the early phases of research and development collaborations, particularly in the new economy industrial sector where joint activities are common (Bader, 2007). The early stage is particularly vulnerable due to the high level of risk and uncertainty.

Challenges in Managing IP Rights Across Multiple Disciplines and Institutions

For research and development (R&D) partnerships, IP management has therefore become a crucial component of success. As a result, firms usually want to get as much IP as possible before engaging in cooperation. Choosing how to handle the IP that results from and emerges during a partnership is a difficult task in practice (Bader, 2008).

Academic institutions across the United States have placed a growing emphasis on IP in recent years. Both new and old problems with study findings surface when research projects grow and persist, partly due to accreditation requirements (Van Dusen, 2013). These concerns include technology transfer rules, ownership of research findings, sharing of new information, and business sector support of academic research. Whether or not colleges will let commercial interests dictate their scholarly objectives and pedagogical missions is another topic of discussion today (Van Dusen, 2013).

Therefore, early on in collaborative processes, IP management in R&D partnerships is crucial. Cooperation partners must have an early and clear agreement on the general distribution of IP ownership and benefits (Bader, 2008). One of the biggest challenges facing the cooperation partners and their strategists is figuring out how to handle the IP that results from R&D collaborations. However, the cooperation partners' prior experiences with the joint patenting procedure determine their readiness to resolve IP concerns and the success rate of R&D partnerships (Bader, 2008).

Regarding IP, universities have adopted a stance in recent years that all innovations, patented goods, and copyrightable materials are governed by university policy, which normally grants the institution first claim to ownership (Van Dusen, 2013). Universities may be able to assert ownership under such regulations, although they frequently specifically recognise that the institution may waive or release this right in favour of the author or inventor (Van Dusen, 2013).

In many educational research centres, communication and cooperation between scientists from universities and business companies have grown commonplace. Today's scientists are fully aware of the potential for financial rewards and stability based on the commercial success of licensed goods because of this relationship, which might lead to an ongoing discussion over IP ownership (Van Dusen, 2013). Conflict may arise between people who feel they have a claim to a vested ownership interest if creativity and money begin to coexist. It is simple for IP creators and inventors to justify their ownership of a thing if they developed it (Van Dusen, 2013). But this presumption is usually changed by university regulations. Policies should be written to clarify ownership rights so that students, staff, instructors, and administrators may live together in harmony. Broadly speaking, university IP rules cover a wide range of creations for the policy (Van Dusen, 2013).

Figure 1.

Challenges Facing IDR in Africa.

Figure 1.

Challenges Facing IDR in Africa.

Addressing Challenges and Prospects of IDR in Africa

Some of the potential solutions to address the challenges facing IDR in Africa are discussed below

Strategic Funding Solutions

Increasing national investment in R&D is crucial to actively support IDR because it gives researchers from various disciplines the funds, they need to support collaborative projects that transcend conventional academic boundaries and inspire them to collaborate on challenging issues. To address this, African governments need to prioritise funding for R&D by increasing their allocation to R&D. This investment in R&D will provide a solid foundation for interdisciplinary initiatives that would promote economic growth and development in addition to advancing scientific understanding (Adepoju, 2022). Establishing national funding agencies dedicated to IDR is crucial. These agencies can prioritise IDR projects, that addresses complex national priorities. For instance, Rwanda's government recently provided $1 million to match funding from the Science for Africa Foundation for Grand Challenges Rwanda, supporting country-based priorities (World Economic Forum, 2023).

In order to establish a more stable financial foundation for IDR projects, governments throughout Africa should be urged to devote a larger portion of their GDP to research and development (Simpkin et al., 2019). Additionally, creating national funding organisations that give priority to interdisciplinary initiatives can guarantee that many research fields obtain sufficient money, encouraging interdisciplinary cooperation (Lyall et al., 2013).

Increasing funding for IDR can also be achieved strategically through public-private partnerships (PPPs) (Meissner, 2019). Co-funding research projects with private sector firms can result in definite advantages for both parties, which encourages cooperation. Successful PPPs in the health sector, like the creation of the MenAfriVac vaccine, show how teamwork may result in major improvements in public health while simultaneously obtaining financial and technical assistance from private organisations (Ota et al., 2018). By enabling the sharing of resources and skills, these collaborations can also aid in closing the funding gap that frequently occurs in interdisciplinary research.

Furthermore, in order to match local research demands with external financial support, it is crucial to strategically leverage international financing. It is possible to guarantee that local communities' goals are fairly represented by actively including African scholars in the agenda-setting process for international financing (Cameron et al., 2025). Innovative solutions to urgent problems can also be developed more easily if international funding organisations are encouraged to sponsor adaptable, IDR projects. A framework for IDR tackling both local and global challenges, can be provided by matching financing with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Brown et al., 2019).

IDR and cost-sharing approaches are essential for improving scientific cooperation (Kulage et al., 2011). For example, to address complex health concerns an interprofessional collaboration in research would highlight the importance of pooling resources and expertise from several disciplines to tackle complicated health issues. Thus, this strategy will enable more efficient use of finances and resources and be a feasible cost-sharing model for IDR in Africa (Dine et al., 2024). IDR projects become more feasible and sustainable when total costs are reduced, and task duplication is minimised. In conclusion, multidimensional strategic funding solutions are necessary to effectively address the financial challenges of IDR in Africa.

Addressing Institutional and Structural Barriers

To unlock the full potential of IDR in Africa, it is imperative to address the institutional and structural barriers that hinder its growth. Many academic institutions on the continent still operate under rigid, discipline-centric models that discourage cross-disciplinary collaboration. Reforming these structures is crucial for fostering a research ecosystem that integrates knowledge across fields to solve Africa’s pressing challenges. As Wimpenny and Orsini-Jones (2020) illustrated in their case study, African universities could incorporate Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) pedagogy in academic programmes. However, it is pertinent to ensure that the curriculum content of such COIL project is interdisciplinary. Building a strong IDR culture in Africa requires training future researchers to think beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries. Universities could integrate interdisciplinary courses into their curricula, exposing students to problem-solving approaches that draw from multiple fields. Graduate and doctoral programmes should encourage interdisciplinary dissertation projects, ensuring that students develop the skills necessary to collaborate across disciplines. Furthermore, mentorship programmes should connect young researchers with established interdisciplinary scholars to provide guidance and foster a culture of collaboration.

African universities could establish dedicated IDR centres that bring together experts from various fields to tackle complex societal issues. These centres should be well-funded, equipped with advanced research facilities, and supported by policies that encourage collaboration. Research funding bodies could place more interest in IDR rather than directed/topic-based funding. Perhaps, these funding bodies could adopt the multilayer network approach pin assessing the impact of IDR to make funding decisions (McLeish & Strang, 2016). Additionally, universities could facilitate partnerships between academic institutions, industries, and government agencies to ensure that IDR translates into real-world solutions.

One of the key obstacles to IDR is the deep-rooted culture of departmental isolation, where researchers remain confined within their respective disciplines. To overcome this, universities could create mechanisms that encourage joint appointments of faculty across multiple departments, fostering collaboration. Moreover, cross-departmental projects should be prioritised in funding allocation and academic recognition, ensuring that IDR is not sidelined by traditional disciplinary boundaries.

Traditional academic reward systems often prioritise single-discipline research outputs, making it difficult for interdisciplinary researchers to gain recognition for their work. African universities could reform tenure and promotion criteria to explicitly reward IDR efforts. Granting agencies and academic bodies could also introduce awards that recognise impactful interdisciplinary work, encouraging more scholars to engage in cross-disciplinary collaborations. This is substantiated by evidence as IDR in the long run is proven to outperform subject specialised research (Sun et al., 2021). Perhaps the need for a quick fix/outcome/impact which in some cases amount to resources wastage has driven the high propensity of single-discipline research funding. Moreover, IDR has been proven to have higher likelihood of receiving patent citations, have higher technological impact, and contribute to the quality of research outcomes (Ke, 2023; Yang et al., 2024). Additionally, journal editorial boards could be encouraged to accept and promote IDR publications.

Infrastructural and Technological Advancements

To help address the data and technological limitations impeding IDR in Africa, substantial commitments in the form of investments in infrastructural and technological advancements are required from all stakeholders in the research ecosystem. Evidence exists on how investments in building robust open access platforms, improving research infrastructure and digital technologies have led to enhanced access to reliable data, promoted collaboration, and fostered innovations in science (Bühler et al., 2023; Shukla et al., 2023).

Open science, through its various open frameworks, has emerged as a great movement that has helped to overcome most of the challenges faced by interdisciplinary researchers in Africa. It has, for instance, ensured that most research knowledge is made available through digital and collaborative technologies, and is fostering the reuse and reproducibility of research materials. Of interest is the open access model to scholarly communication, which has significantly helped bridge the digital divide by minimising access cost encountered by most researchers in the global south (Sheikh & Richardson, 2023). To help realise the full benefits of open access, however, more commitments and investments have to be made. For instance, there has been calls for the development of regional open data repositories, that can help enhance access to reliable datasets and promote data-sharing agreements among institutions and researchers (Chabilall et al., 2024). Already, Mwanga et al. (2024) have identified the lack of standardised data sharing guidelines, challenges with data localisation, data systems interoperability, administrative and bureaucratic barriers to data sharing, inadequate data sharing platforms and mistrust arising from fear of data misrepresentation and misuse as challenges calling for the establishment of regional data hubs. Thus, more resources should be channelled to the creation of platforms like the African Open Science Platform and the INSPIRE datahub, which can help to centralise and standardise data management as well as facilitating collaboration and reducing data duplication (Bhattacharjee et al., 2024).

Another important area that needs focus is investment in research infrastructure, as this represents an increasingly large and important part of modern scientific and technological development. Such investment could take the form of an organisational structure dedicated to facilitate or conduct research, provide scientific equipment and manage data for use in basic or applied research (Järvinen et al., 2023). To help sustain interdisciplinary research, governments, private enterprises and research institutions in Africa need to have a workable approach to upgrading existing research infrastructure, like laboratories, libraries, and digital repositories, as these hubs are essential determinants of quality research. Additionally, researchers pursuing interdisciplinary investigations should leverage digital technologies to overcome the physical and technical barriers. Tools like virtual conferences, shared online workspaces and social media platforms could help remove cross-border challenges that most researchers encounter in Africa.

By implementing these solutions, scientists in Africa can overcome challenges involving data and technological limitations that hinder interdisciplinary research, unlocking its full potential to drive sustainable development. It is essential for stakeholders, including governments, institutions and researchers, to collaborate and invest in these initiatives to promote a culture of open science, innovation and collaboration.

Community Building, Networking and Diversity

IDR holds immense promises for tackling the complex challenges facing Africa. It brings together knowledge and methods from different academic fields, offering a more holistic approach. However, realising this potential isn't straightforward. We have to overcome several hurdles, including structural, institutional, and cultural barriers that can make collaboration difficult. A key step is building strong research communities that truly support interdisciplinary work.

Creating inclusive research communities is essential. We need environments where diverse perspectives can contribute to innovative solutions. These communities should include researchers from various disciplines, backgrounds, and experiences, ensuring a wide range of insights contribute to our knowledge (D’Este & Robinson-García, 2023). Diversity in gender, ethnicity, and professional background are crucial. It enriches research by offering multiple viewpoints, leading to more robust and relevant findings (Swartz et al., 2019). But we can't ignore the historical power imbalances and underrepresentation that exist. These can hinder genuine collaboration, so actively promoting inclusivity is a must. Beyond diversity, networking is also critical. It connects researchers, institutions, and stakeholders within Africa and globally, facilitating the exchange of ideas, resources, and expertise (Olatunji et al., 2023).

Networking isn't just about making connections; it also opens doors to interdisciplinary training, which is vital for cross-disciplinary researchers. Traditional academic training often focuses on a single discipline, leaving researchers unprepared for interdisciplinary work. Interdisciplinary training programmes should focus on methodologies, communication, and collaboration skills – all essential for interdisciplinary projects (Ye & Xu, 2023). Workshops are particularly valuable for knowledge exchange. They allow researchers to learn from each other, share best practices, and develop joint research proposals. For these programmes to be effective, they need to be context-specific, addressing the unique challenges and opportunities within different African regions.

These regional differences are important. Strengthening regional research networks can help mitigate resource limitations and encourage collaboration between researchers in different countries. These networks can facilitate data sharing, access to specialised equipment, and joint capacity-building initiatives. They also help establish shared research priorities aligned with the specific needs of different regions. However, building and maintaining these networks isn't easy. We face political and logistical challenges, like differing research policies and inconsistent funding. Overcoming these requires coordinated effort to harmonise research policies and funding structures across the continent.

Beyond the institutional and logistical, language barriers and cultural differences can also impede effective collaboration and the translation of research into action. Researchers from different language backgrounds may struggle to communicate, hindering knowledge exchange. Translation and cultural mediation services can bridge these gaps, making research more accessible to wider audiences, including local communities and policymakers (Squires et al., 2020). Cultural mediation also ensures research is grounded in local contexts, increasing its relevance and potential impact. Unfortunately, these services are often overlooked, highlighting the need for greater investment in communication strategies that support interdisciplinary work.

Despite these challenges, there are significant opportunities. The growing recognition of interdisciplinary approaches as crucial for addressing complex global issues like climate change and public health crises has led to new funding and international collaborations (Goniewicz et al., 2025; King et al., 2023). The increasing number of trained African researchers and expanding research institutions also provide a solid foundation for building strong IDR programmes. By nurturing inclusive research communities, improving interdisciplinary training, strengthening regional networks, and addressing language and cultural barriers, Africa can truly unlock the potential of IDR and drive sustainable solutions to its most pressing problems.

Policy Advocacy and Political Stability

The world has indeed become a global village, however, is prudent to highlight that there are problems and challenges that are unique to the African continent with similar societal burden by virtue of similarities in geographical location, lifestyle and beliefs. Fostering national, continental and international collaborations amongst researchers tends to provide a more sustainable solution and approach to societal dilemmas. Some initiatives (Local or International) have been commenced to support this agenda. Locally, the interdisciplinary policy-oriented research on Africa (IPORA) is one of such committed to working with researchers from different disciplines to support research that benefits populations within Africa and advance the concept of interdisciplinarity (Interdisciplinary Policy-Oriented Research on Africa (IPORA), 2024). Internationally, the international science council (ISC) works at a global level with regional presence in various continents including Africa. In Africa, there is the presence of members in countries such as Burkina Faso, south Africa, Cameroon just to mention a few. The Center for Scientific and Technological Research (CNRST) in Burkina Faso; made up of 4 institutions namely the Environment and Agricultural Research Institute (INERA), the Applied Sciences and Technological Research Institute (IRSAT), the Health Sciences Research Institute (IRSS) and the Institute of Sciences of Society (INSS) aims to the design, the implementation and monitoring of government policy on research and innovation for economic and social development in Burkina Faso. Even though there seems to be some effort to encourage interdisciplinary research, more collaboration between researchers and policy makers might be needed to influence regulatory reforms. Also, the creation of policies for funding or grant tailored for IDR will enable sustainability and provide needed financial support.

There is a need for the creation of unified regulatory bodies which establish national or regional agencies to streamline approval processes explicitly for IDR (Domino et al., 2007). This could be done through collaboration with bodies like the African union or ECOWAS. This would cut down on unnecessary repetition of procedures. The development of common ethical review guidelines across disciplines, institutions, regions and countries will reduce redundancy in the ethical review process. Also, researchers can be provided with training on how to navigate regulatory frameworks and perhaps, institutions and universities may integrate IDR methods into their curricula.

Some countries like Ghana, Botswana and Namibia have proven the ability for political stability in some regions and countries within Africa (Institute for Economics & Peace, 2024). Researchers can be intentional about fostering collaborations within countries or regions that have enjoyed extended periods of political stability and have the requisite systems in place to maintain that peace. In conjunction with the African union, Ecowas and other national peacekeeping missions, procedures for conflict resolutions can be put in place to ensure that minor conflicts are addressed swiftly and prevented from escalating into full blow wars or riots (Apuuli, 2021; Obi, 2009).

Capacity Building and Professional Development

Building and maintaining capacity while guaranteeing ongoing professional development is critical to the growth of multidisciplinary research in Africa. Implementing retention programmes, offering specialised training, creating mentorship networks, and increasing IP management capability are all strategic ways to get beyond obstacles.

To stop brain drain and ensure the continent's long-term supply of qualified researchers, retention initiatives should prioritise competitive pay, strong research funding, and access to cutting-edge infrastructure. African scholars have historically migrated to nations with greater possibilities due to a lack of financial incentives and sufficient resources (Aregbeshola & Adekunle, 2024). To develop funding packages and grant opportunities specifically suited to transdisciplinary research, governments, academic institutions, and business stakeholders should work together. For instance, there should be creation of centres of excellence that incorporate finance, and competitive compensation, as encouraged by the African Union's Agenda 2063 (African Union Commission, 2015).

To do interdisciplinary research, researchers must transcend disciplinary boundaries and cultivate methodological and collaborative proficiency in multiple domains. Thus, priority should be given to specialised multidisciplinary training programmes and fellowships. More so, curriculum that offers researchers the theoretical frameworks, instruments, and methods necessary to approach complicated societal issues might be incorporated into these programmes. For example, the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA) has successfully provided multidisciplinary skills to African researchers (Khisa et al., 2019). Contextual relevance can also be guaranteed via fellowship programmes designed to address issues unique to Africa, such as public health, food security, and climate change.

Early career academics' professional development and interdisciplinary collaboration depend heavily on mentoring networks. Mentorship programmes help novice researchers navigate the challenges of cross-disciplinary work by matching them with more seasoned interdisciplinary scholars. Research networks are strengthened, and knowledge sharing is facilitated by such initiatives. To develop research capacity, the African Research Universities Alliance (ARUA) has effectively established mentorship opportunities (African Research Universities Alliance (ARUA), 2022). Similar initiatives could be implemented by academic institutions and research centres to develop a pool of multidisciplinary researchers capable of coming up with novel answers to Africa's particular problems.

The inadequate knowledge and administration of IP rights is one major deficiency in Africa's research ecosystem. Researchers and institutions will be better equipped to safeguard their discoveries, negotiate fair agreements, and draw in investment if IP management capabilities are strengthened. Multidisciplinary research projects should incorporate training courses on IP laws, patent procedures, and negotiation techniques. Organizations such as the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO), for instance, provide capacity-building initiatives that can be extended to accommodate researchers' expanding needs (African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO), 2024). African researchers can optimise their ideas by coordinating IP management techniques with transdisciplinary initiatives.

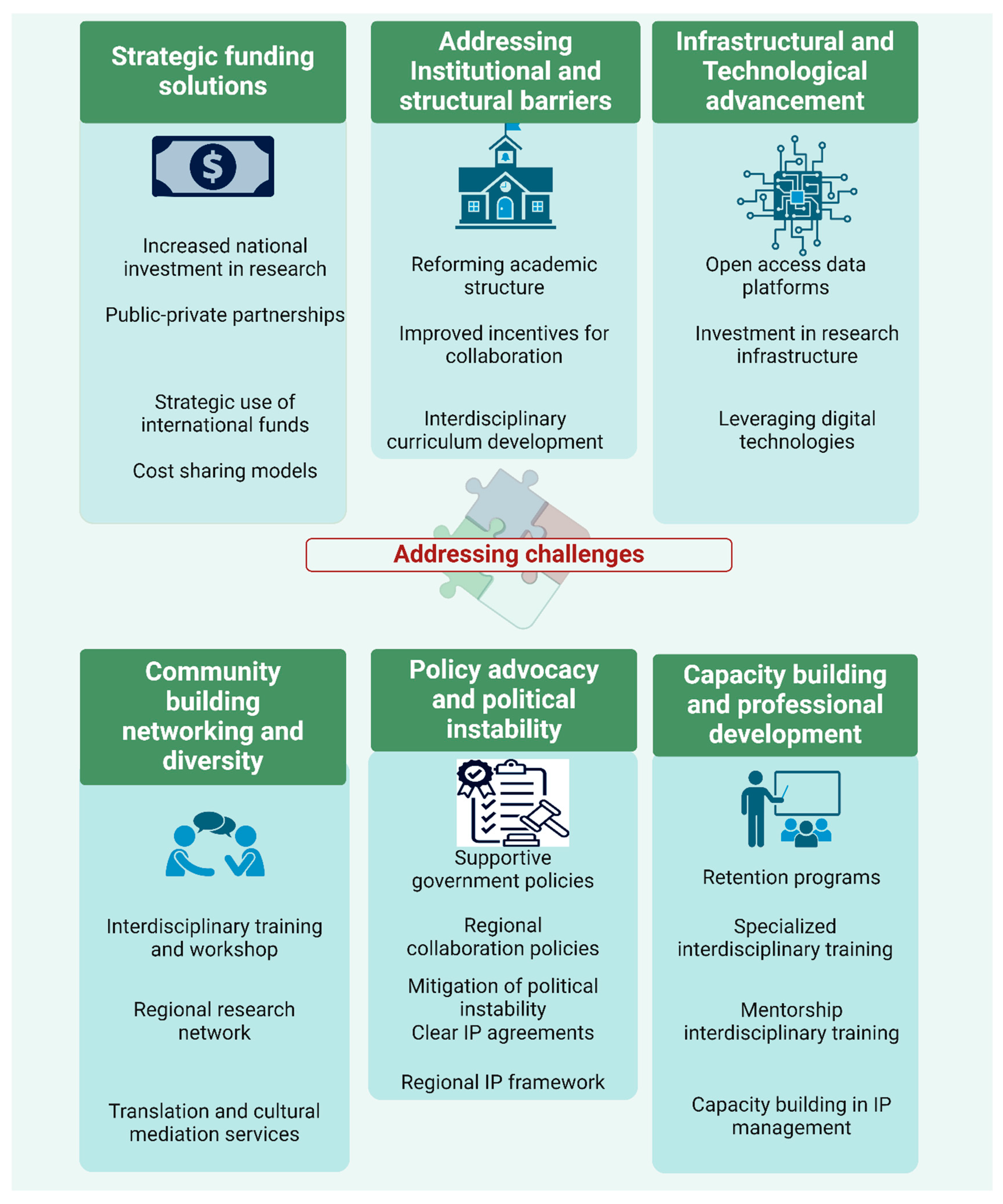

Figure 2.

Addressing Challenges and Prospects of IDR in Africa.

Figure 2.

Addressing Challenges and Prospects of IDR in Africa.

Conclusion

IDR in Africa presents immense potential for scientific innovation and socioeconomic transformation. However, its progress is hindered by several persistent challenges. Limited and inconsistent funding remains a critical barrier, as many African nations allocate insufficient resources to research and development, restricting opportunities for cross-disciplinary collaborations. Institutional and structural barriers, such as rigid academic frameworks, disciplinary silos, and outdated incentive systems, further discourage interdisciplinary work. Additionally, infrastructural and technological limitations, including inadequate research facilities, poor digital access, and fragmented data-sharing mechanisms, stifle collaboration and innovation. Furthermore, the absence of strong research communities, networking platforms, and diversity-driven policies limits interdisciplinary engagement, while policy inconsistencies and political instability in some regions create uncertainty in research funding and execution. Finally, capacity-building gaps, including the lack of specialised interdisciplinary training, mentorship programmes, and IP management skills, reduce the ability of African researchers to fully harness the benefits of IDR.

Addressing these challenges is essential to unlocking the full potential of IDR in Africa. As the continent grapples with complex issues such as public health crises, food security, climate change, and technological innovation, interdisciplinary approaches provide holistic and sustainable solutions. By integrating knowledge across disciplines, IDR fosters innovation, enhances research impact, and bridges the gap between science and societal needs. Strengthening IDR will also promote economic growth, advance scientific knowledge, and position African researchers as key players in global research agendas. Furthermore, fostering open science, investing in research infrastructure, and improving collaborative frameworks will enable Africa to take a leading role in solving its pressing developmental challenges.

To fully realise the potential of IDR in Africa, coordinated efforts from multiple stakeholders are imperative. Governments must increase national investment in research and development, establish funding agencies dedicated to IDR, and formulate policies that encourage cross-disciplinary collaborations. Academic institutions should restructure traditional frameworks to accommodate IDR centres, revise incentive systems to reward collaborative efforts, and integrate interdisciplinary training into curricula. International partners should align funding mechanisms with African research priorities, support regional data-sharing initiatives, and facilitate global networking opportunities for African researchers. Additionally, the private sector must play a more active role by fostering public-private partnerships, co-funding interdisciplinary projects, and leveraging research innovations for industrial growth.

A paradigm shift is needed—one that prioritises sustainable funding, fosters collaborative cultures, strengthens research infrastructure, and builds inclusive, diverse research networks. By collectively embracing these strategies, Africa can overcome the barriers to IDR and harness its transformative power to drive scientific progress, economic development, and social change.