Submitted:

13 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. RQ 1: Is Quantitative Research Helpful Despite Limited Data Points for Short-Term Studies?

- Income: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) (Hourly wage*8*22)

- Unemployment Rate: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Wage Growth: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)*

- Consumer Spending [personal consumption expenditures (PCE)]: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)

- Debt-to-Income Ratio (DTI): Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

- Inflation Rate: Trading Economics1

- Trump-Era Tariffs: Atlantic Council Trump Tariff Tracker

- Income Grouping: Calculated based on percentile distribution of income data**

2.2. RQ 2: Does Qualitative Research Add Value?

2.3. RQ 3: Do Microeconomic, Small-Sample Surveys Help Us Humanize Research?

2.4. RQ 4: Which Sequencing (Quantitative>Qualitative or Qualitative>Quantitative; Closed-Ended>Open-Ended or Open-Ended>Closed-Ended) is Preferable and More Insightful?

- Set 1: Quantitative → Qualitative

- Set 2: Qualitative → Quantitative

- Set 1: Closed-ended → Open-ended

- Set 2: Open-ended → Closed-ended

3. Results

3.1. RQ 1: Is Quantitative Research Helpful Despite Limited Data Points for Short-Term Studies?

- 1.

- Income

- 2.

- Inflation

- Inflation Rate

- Wage Growth

- Debt-to-Income Ratio

- Consumer Spending

- Unemployment Rate

- Trump Tariffs

- Income Group (used in interaction term)

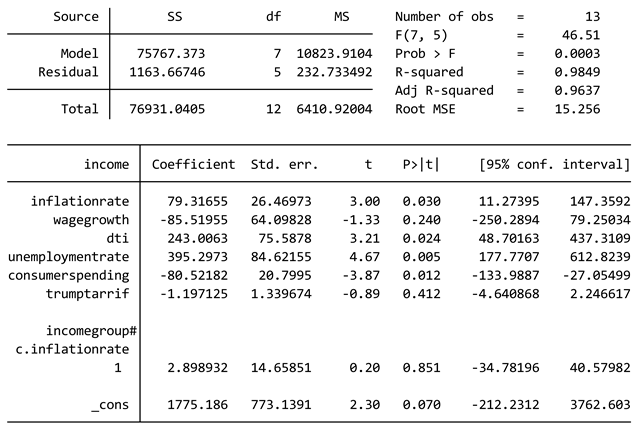

- Inflation Rate × Income Group (interaction term to assess differential effects of inflation across income levels)

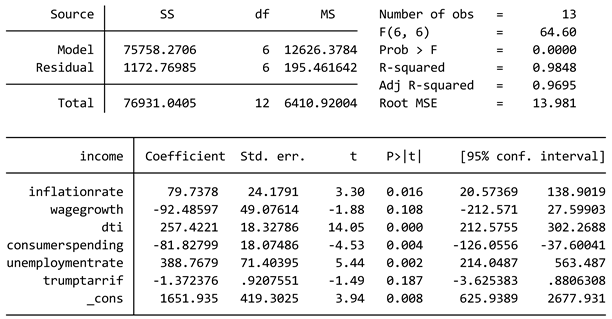

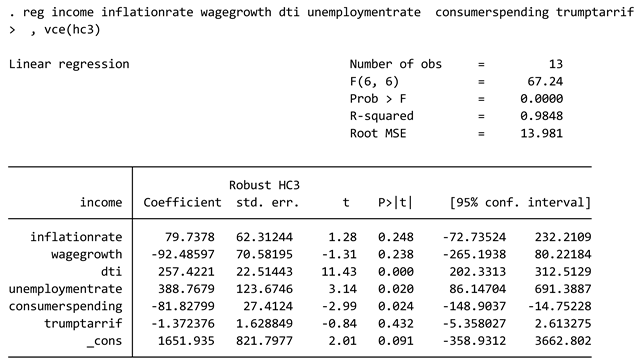

- Inflation Rate (β = 79.74, p = 0.0165): A statistically significant positive coefficient suggests that higher inflation is correlated with an increase in income. This could indicate nominal wage adjustments in response to inflation, though real income effects should be further examined.

- Wage Growth (β = -92.49, p = 0.1085): The negative but statistically insignificant coefficient suggests that wage growth does not strongly predict income changes. This could imply that wage increases have not kept pace with inflation or that real wage stagnation limits its effect.2

- Debt-to-Income Ratio (β = 257.42, p = 0.0000): A highly significant positive relationship indicates that individuals or households with higher debt-to-income ratios tend to report higher income levels. This seems to reflect debt access rather than debt necessity.

- Consumer Spending (β = -81.82, p = 0.0040): The significant negative coefficient indicates that increased consumer spending is associated with lower income. While high-income groups tend to spend more in absolute terms, this finding may reflect financial pressure among lower- and middle-income groups—where spending, especially on essentials, rises despite stagnant earnings. Future research could explore spending-to-income ratios to capture this relationship with greater nuance.3

- Unemployment Rate (β = 388.76, p = 0.0016): A strong positive relationship suggests that higher unemployment is linked to increased income levels. While counterintuitive at first glance—and seemingly at odds with traditional expectations such as the Phillips Curve—this result may reflect sample-specific dynamics or compositional effects. For instance, during certain economic adjustments, job losses may be concentrated in lower-wage sectors, skewing the income distribution of those who remain employed upward. This does not imply that unemployment causes higher income overall, but that in the observed data, the employed sample includes a relatively higher proportion of middle- to high-income earners. Additionally, in a post-COVID context shaped by gig work, remote employment, and selective sectoral recovery, standard relationships between labor indicators and income may appear disrupted or reconfigured. Future research could disaggregate employment effects further, distinguishing between temporary layoffs, underemployment, or sector-specific shocks.4

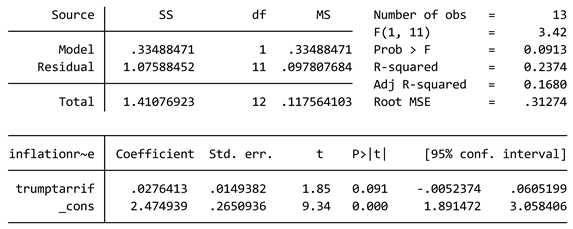

- Trump Tariffs (β = -1.37, p = 0.1867): The negative but statistically insignificant coefficient suggests that tariff-driven price changes have not had a direct significant impact on income levels, though their broader inflationary effects may play a role.

- An R-squared of 0.9847 indicates that the model explains 98.47% of the variation in income, suggesting strong explanatory power.

- The F-statistic (p = 0.000035) confirms that the overall regression is statistically significant.

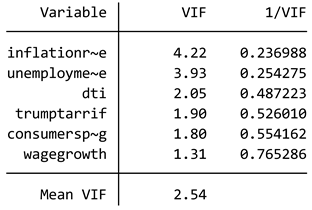

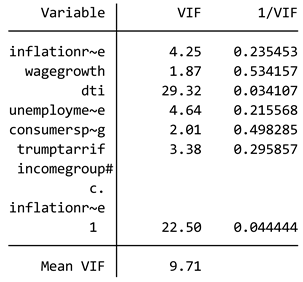

- The results of the heteroscedasticity test indicate no evidence of heteroscedasticity in the model. The null hypothesis (H₀) assumes constant variance, and the test yielded a chi-square value of 0.00 with a corresponding p-value of 0.9712, which is well above the conventional significance level of 0.05. This suggests that the assumption of homoscedasticity holds true. Additionally, the multicollinearity test revealed that none of the coefficients had a centered variance inflation factor (VIF) value greater than 10 (Table 2), indicating that multicollinearity is not a concern in the model.

3.2. RQ 2: Does Qualitative Research Add Value?

3.3. RQ 3: Do Microeconomic, Small-Sample Surveys Help Us Humanize Research?

3.4. RQ 4: Which Sequencing (Quantitative>Qualitative or Qualitative>Quantitative; Closed-Ended>Open-Ended or Open-Ended>Closed-Ended) Is Preferable and More Insightful?

- “By synthesizing the empirical findings of Analysis 1 and the thematic insights from Analysis 2, we can develop a more comprehensive understanding of inflation’s multifaceted effects…”

-

“This financial strain exacerbates economic inequality and limits upward mobility.”(A conclusion grounded in both quantitative DTI patterns and qualitative themes like savings depletion and constrained consumption.)

-

“Consumer spending’s significant negative impact on income… signals financial stress and decreased economic participation, further reinforcing inequality.”(Showing alignment between regression trends and macro-level social impacts.)

-

“A key anomaly in Analysis 1 is that higher unemployment rates are positively correlated with income… Analysis 2 provides context…”(An example of one dataset contextualizing another.)

- Political Implications

- 6.

- Wage Stagnation

- 7.

- Debt-to-Income and Credit Dependency

- 1.

- Closed>Open-ended:

- 2.

- Closed>Open-ended:

- 3.

- Closed>Open-ended:

- 4.

- Closed>Open-ended:

- 5.

- Closed>Open-ended:

- 6.

- Closed>Open-ended:

- 7.

- Consistency and polarization issues: While some observations in the Open>Closed-ended set indicate that the middle-income group is more strained, others emphasize the sheer severity of low-income struggles. Closed>Open-ended is more balanced and consistent in this sense.

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ 1: Is Quantitative Research Helpful Despite Limited Data Points for Short-Term Studies?

4.2. RQ 2: Does Qualitative Research Add Value?

4.3. RQ 3: Do Microeconomic, Small-Sample Surveys Help Us Humanize Research?

4.4. RQ 4: Which Sequencing (Quantitative>Qualitative or Qualitative>Quantitative; Closed-Ended>Open-Ended or Open-Ended>Closed-Ended) is Preferable and More Insightful?

5. Conclusions

5.1. RQ1: Is Quantitative Research Helpful in Short-Term Studies with Limited Data?

5.2. RQ2: Does Qualitative Research Add Value?

5.3. RQ3: Do Small-Scale Surveys Help Humanize Research?

5.4. RQ4: Which Sequencing (Quantitative>Qualitative or Qualitative>Quantitative; Closed-Ended>Open-Ended or Open-Ended>Closed-Ended) is Preferable and More Insightful?

5.5. Limitations, Future Scope, and Implications

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Data Sources

- Income: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

- Unemployment Rate: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Wage Growth: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

- Consumer Spending: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)

- Debt-to-Income Ratio (DTI): Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

- Inflation Rate: Trading Economics

- Trump-Era Tariffs: Atlantic Council Trump Tariff Tracker

- World Economic Outlook (2025) https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-economic-surveys-united-states-2024_cdfff156-en.html

- International Monetary Fund (2025) https://www.imf.org/en/Videos/view?vid=6367238532112

- World Bank Group (2024) https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/poverty-prosperity-and-planet

| 1 | While this study references primary sources like BEA and BLS in other sections, Trading Economics was used here to enable efficient cross-indicator alignment across uniform monthly timeframes, especially for regression modeling. Its curated datasets offer immediate usability, minimizing preprocessing efforts and allowing for smoother integration of macro-level variables within a short-term, mixed-methods framework. Given the study’s focus on temporal sensitivity and rapid economic shifts, this streamlined access supported timely analysis while maintaining data fidelity. All figures used were archived and are available to ensure transparency and facilitate future comparative research. |

| 2 | Wage growth is a key component of household income and is often used as a proxy for labor market strength. Analyzing its relationship with income changes helps determine whether reported income increases are due to actual improvements in compensation or other factors like borrowing or inflation-driven adjustments. In this model, the weak and negative coefficient for wage growth may suggest that nominal wage increases have not translated into meaningful income gains—possibly due to inflation eroding real wages or wage growth being concentrated in sectors not well-represented in the sample. Including wage growth in the model is therefore essential to understand whether income gains are substantive or illusory, especially in volatile, post-crisis conditions. |

| 3 | Consumer spending in this study is measured using monthly percentage changes in Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE), sourced from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). This macro-level indicator reflects the overall direction and momentum of household consumption in the economy. As such, the regression captures the association between income changes and the aggregate fluctuation in consumer demand, rather than individual or group-specific dollar amounts. While higher-income groups may indeed spend more in absolute terms, this model interprets broader spending trends as proxies for economic strain or resilience across the income distribution. The data used in this analysis are available to facilitate future comparison or replication. |

| 4 | While traditionally the Phillips Curve posits an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment, recent labor market trends—particularly post-pandemic—have shown greater heterogeneity. High-income earners in knowledge-based sectors may maintain or increase earnings despite rising unemployment in lower-income service sectors. This compositional effect may help explain the observed positive correlation in the model. Moreover, the regression does not claim a causal relationship but identifies patterns in aggregate data that warrant deeper stratified analysis. |

| 5 | This analysis focuses on consumer inflation, where the extent of price increases depends on the degree to which companies pass on tariff-related costs to consumers. Further analysis, including interaction models, can refine these insights on inflation’s impact across income strata—specifically in the context of consumer inflation, where the extent of price increases depends on how much of the tariff-related cost is passed through by companies to end consumers. |

| 6 | The inclusion of a time-based income trend graph provides essential context for interpreting the regression results and understanding the dynamics of income movement across the study period. While the regression models assess the strength and direction of relationships between variables, the trend graph offers a visual overview of the dataset’s temporal stability. This helps establish whether the income data exhibits anomalous shifts, cyclical patterns, or structural breaks, any of which could influence the robustness of the model. Additionally, the visual cue of linearity strengthens confidence in the assumption of temporal consistency, which supports the model’s validity for short-term policy inferences. Including this figure also enables future researchers to compare or extend the dataset using the same time frame. |

References

- Aspachs, O., Durante, R., Graziano, A., Mestres, J., Reynal-Querol, M., and Montalvo, J. G. 2021. “Tracking the Impact of COVID-19 on Economic Inequality at High Frequency.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(31): e2105784118. [CrossRef]

- Friese, S., Soratto, J., and de Pires, D. E. P. 2018. “Carrying Out a Computer-Aided Thematic Content Analysis with ATLAS.ti.” ResearchGate. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324720405_Carrying_out_a_computer-aided_thematic_content_analysis_with_ATLASti.

- Furceri, D., Loungani, P., Ostry, J. D., and Pizzuto, P. 2021. Will COVID-19 Have Long-Lasting Effects on Inequality? Evidence from Past Pandemics (IMF Working Paper No. 2021/105). International Monetary Fund. [CrossRef]

- Harding, M., Lindé, J., and Trabandt, M. 2023. Understanding Post-COVID Inflation Dynamics (IMF Working Paper No. 2023/017). International Monetary Fund. [CrossRef]

- Jayashankar, S., and Murphy, A. 2023. “High Inflation Disproportionately Hurts Low-Income Households.” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Retrieved from https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2023/0110.

- Knicker, F., Naumann-Woleske, J., Bouchaud, J.-P., and Zamponi, F. 2024. “Post-COVID Inflation & the Monetary Policy Dilemma: An Agent-Based Scenario Analysis.” arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.01284.

- Sintos, D. 2023. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Labor Markets and Inequality.” ResearchGate. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373762681_Does_inflation_worsen_income_inequality_A_meta-analysis.

- Vindrola-Padros, C., Chisnall, G., Cooper, S., Dowrick, A., Djellouli, N., Mulcahy Symmons, S., Martin, S., Singleton, G., Vanderslott, S., Vera, N., and Johnson, G. A. 2020. “Carrying Out Rapid Qualitative Research During a Pandemic: Emerging Lessons from COVID-19.” Qualitative Health Research 30(14): 2192–2204. [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Theme | Insight | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Inflation Control and Monetary Policies | Emphasizes the need for monetary policy adjustment and fiscal consolidation to manage inflationary pressures. | OECD Economic Surveys: United States 2024 |

| Discusses global inflation trends and the divergent responses of central banks, highlighting the cautious approach in places where inflation is more persistent. | World Economic Outlook 2025 | |

| Consumer Behavior and Economic Growth | Focuses on global poverty and its impact on consumer behavior, with specific emphasis on shared prosperity and economic inclusion. | Poverty, Prosperity, and Planet Report 2024 |

| Notes changes in consumer confidence and its effects on economic performance, particularly in China and the United States. | World Economic Outlook 2025 | |

| Social Impacts and Inequality | Highlights the stalled progress in global poverty reduction and inequality, discussing the need for comprehensive strategies to tackle structural sources of inequality. | Poverty, Prosperity, and Planet Report 2024 |

| Addresses income inequality and its implications for fiscal policies and social stability. | OECD Economic Surveys: United States 2024 |

| Source | Inflation Control | Consumer Behavior | Social Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| OECD Economic Surveys: United States 2024 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Poverty, Prosperity, and Planet Report 2024 | No | Yes | Yes |

| World Economic Outlook 2025 | Yes | Yes | No |

| Thematic Item | Explains/Contextualizes These Aspects of the Quantitative Analysis |

|---|---|

| Item 1: Overview of the Analysis This analysis examines inflation-related policies, consumer behavior, and social impacts using thematic analysis via Atlas.ti 2025. It synthesizes key economic insights from three major reports:

|

- Positions the U.S.-focused regression within a broader global policy context (OECD, IMF, World Bank). - Explains the relevance of inequality, environmental, and social dimensions that are not directly modeled but affect outcomes like spending and income. |

| Item 2: Key Themes and Insights Theme 1: Inflation Control & Monetary Policies

Theme 2: Consumer Behavior & Economic Growth

Theme 3: Social Impacts & Inequality

|

- Theme 1 (Inflation Control & Monetary Policies): Contextualizes the limited real wage growth (insignificant wage-inflation link) as a global policy outcome. - Theme 2 (Consumer Behavior): Supports finding that consumer spending negatively affects income, especially in lower brackets. - Theme 3 (Social Impacts): Aligns with findings that only DTI significantly affects low-income earners, showing deeper structural vulnerability. |

| Item 3: Findings on Inflation’s Impact by Income Groups High-Income Groups:

Middle-Income Groups:

Low-Income Groups:

|

How it connects:

- Directly supports stratified regression findings: • High-income: Positive inflation-income correlation due to asset appreciation. • Middle-income: Income squeezed, mirroring weak wage growth and reduced spending. • Low-income: High DTI reliance and consumer cutbacks match regression results. |

| Item 4: Policy & Economic Trends Inflation Worsens Inequality:

|

- Explains why inflation correlates with income (nominal gains for asset holders, not wage earners). - Adds depth to the DTI-income link in lower-income groups (credit reliance). - Clarifies lack of tariff-income correlation (tariffs’ indirect inflationary role). - Supports observed consumer spending drop as a systemic effect of inequality and wage stagnation. |

Item 5: Conclusion

|

- Reinforces empirical study’s call for integrated fiscal/monetary responses. - Aligns with recommendation to focus on employment and debt management. - Validates need for quantile regression and non-linear models to capture unequal effects. |

| Open-Ended Survey Finding | What It Shows | How It Explains the Closed-Ended Results (indicating a higher burden on middle-income groups) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Key Findings: Inflation’s Effects on Different Income Groups | Spending Adjustments: Lower-income groups eliminate discretionary spending, while middle-income groups shift strategies but keep spending. | Middle-income groups appear more vocal about inflation because they still have spending flexibility—they are adjusting rather than eliminating. Lower-income groups, already cutting back for survival, aren’t experiencing a drastic new change—they were struggling before. |

| 2. Unexpected Impacts of Inflation | Life Disruptions: Lower-income groups struggle with basic needs, while middle-income groups struggle with savings and security. | The middle class feels the crisis differently—they are losing financial progress, not just struggling to survive. This fuels their anxiety and makes them perceive inflation as a bigger disruption than lower-income groups. |

| 3. Suggested Policy Solutions | Policy Priorities: Lower-income respondents want immediate relief (wage growth, rent control), while middle-income respondents want structural reforms (lower taxes, anti-price gouging laws). | Middle-income respondents have more faith in systemic change because they still have assets and financial options. Lower-income respondents need instant intervention since they lack financial buffers. |

| 4. Deep Interpretation: Inflation’s Disproportionate Burden | Survival vs. Stability: Lower-income groups are in crisis mode, while middle-income groups feel a gradual erosion of security. | The middle class is alarmed because they had stability before but are now slipping—this sudden loss of control makes them more vocal than lower-income groups, who were already struggling. |

| 5. The Psychology of Inflation: Stress and Uncertainty | Behavioral & Psychological Shifts: Lower-income respondents experience financial anxiety due to survival stress, while middle-income respondents feel growing insecurity due to inflation eating into their financial future. | Middle-income stress feels more “unexpected”—they weren’t prepared to struggle like this. Lower-income respondents are already conditioned to financial hardship, so their response doesn’t change as dramatically. |

| 6. The Inflation Tipping Point: Where Do Groups Break? | Critical Breaking Points: The lower-income group is already at maximum strain, while middle-income respondents have some resilience but are at risk of falling downward. | Middle-income respondents feel more threatened because they still have something to lose. Lower-income respondents have already hit rock bottom, so inflation doesn’t change their baseline as drastically. |

| 7. Final Interpretation: Inflation as a Social Turning Point | Long-Term Consequences: Inflation is not just economic—it is redefining class structure and mobility. | Without intervention, today’s middle class will become tomorrow’s struggling class. The anxiety middle-income respondents feel is justified because they sense they are on the brink of falling down the economic ladder. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).