Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. RIF Regression

2.1. RIF Regression Framework for Pure Location-Shifts

2.2. General Unconditional Effects

- Location shift This is the case developed above taken from [1] analysis that consider a location shift change in one covariate of the form

- Location-scale shiftwhere , and are continuously differentiable functions with and , respectively. Here acts as a shrinking parameter such that an increment in this parameter reduces the overall impact of the X variable. The pure location shift in [1] can be obtained by setting and . [9] have a similar shift written in a different manner. In fact different alternatives can be developed based on how to combine the location and scale joint shifts.

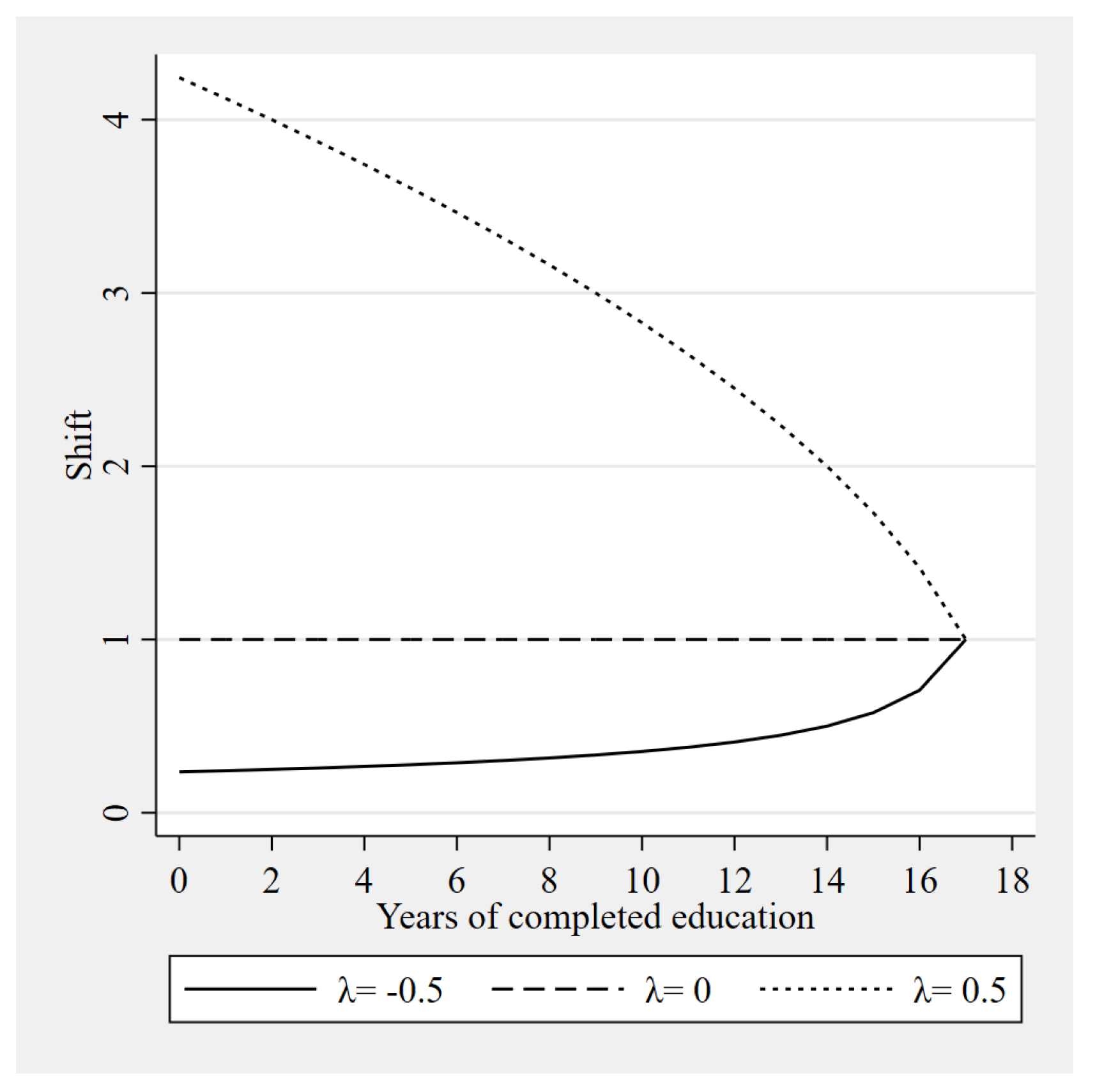

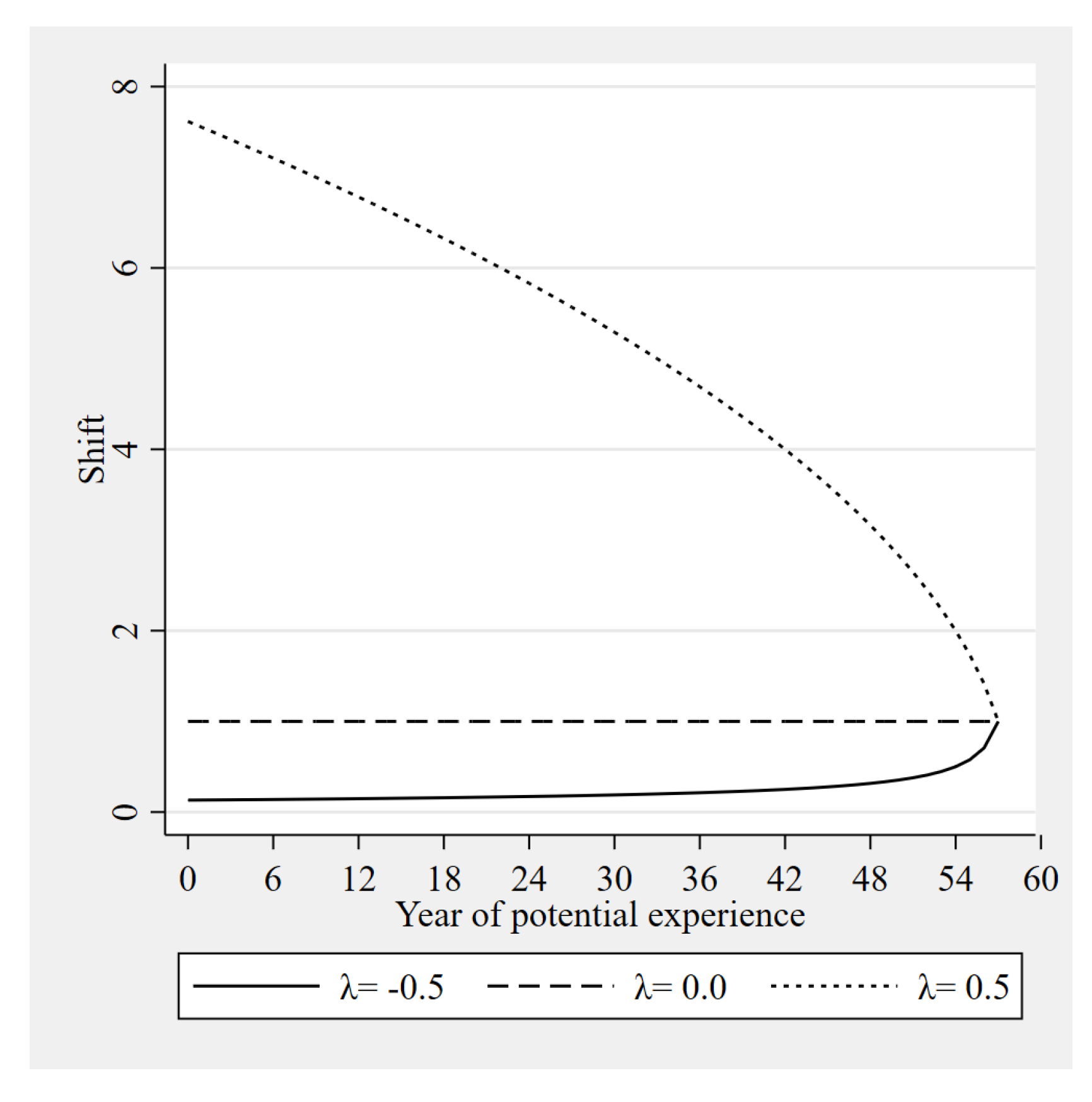

- Asymmetric shiftwhere , and the map satisfies: , , and is continuously differentiable. The factor is maximum value in the support of X or an upper bound. The parameter determines the asymmetry of the shift effecs: if then the shift is biased towards upper values, if the shift is biased towards lower values, if this would be a pure location-shift. Although this type of shift was applied as a numerical simulation exercise in [14], the novelty of our proposal is to include it analytically within the RIF regression strategy.

-

Location shiftThis is indeed the estimand of [1] and the most popular amongst RIF regression empirical applications.

-

Location-scale shift

- Asymmetric shift

2.3. Empirical Examples to Motivate the Estimands

3. Generalized RIF Estimator

4. Monte Carlo Experiments

- Pure location shift: and .

- Pure scale shift: and .

- Location-Scale shift: and .

- Asymmetric shift: and . Here we set such that no values in the simulations will exceed this.

5. Empirical Application

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Functionals and Their RIF

Appendix A.1. Gini Index

Appendix Sample Estimator

Appendix Theil Index

Appendix Sample Estimator

Appendix Atkinson Index

Appendix Sample Estimator

References

- Firpo, S.; Fortin, N.; Lemieux, T. Unconditional quantile regression. Econometrica 2009, 77(3), 953–973. [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart, A. Asymptotic Statistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Essama-Nssah, B.; Lambert, P. Chapter 6. Influence Functions for Policy Impact Analysis. In Inequality, Mobility and Segregation: Essays in Honor of Jacques Silber Research on Economic Inequality; 2015; Vol. 20, pp. 135–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, N.; Lemieux, T.; Firpo, S. Ashenfelter, O., Card, D., Eds.; Decomposition methods in economics. In Handbook of Labor Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Firpo, S.; Pinto, C. Identification and Estimation of Distributional Impacts of Interventions Using Changes in Inequality Measures. Journal of Applied Econometrics 2016, 31(3), 457–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firpo, S.; Fortin, N.; Lemieux, T. Decomposing Wage Distributions Using Recentered Influence Function Regressions. Econometrics 2018, 6(3), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Fernández-Val, I.; Melly, B. Inference on counterfactual distributions. Econometrica 2013, 81(6), 2205–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Iriarte, J. Sensitivity Analysis in Unconditional Quantile Effects. Working Paper.

- Martínez-Iriarte, J.; Montes-Rojas, G.; Sun, Y. Unconditional Effects of General Policy Interventions. Journal of Econometrics 2024, 238(2), 105570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Li, T.; Xu, Q. Two Sample Unconditional Quantile Effect. ARXIV. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2105.09445.pdf.

- Sasaki, Y.; Ura, T.; Zhang, Y. Unconditional quantile regression with high-dimensional data. Quantitative Economics 2022, 13, 955–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo, J.; Galvao, A.F.; Martinez-Iriarte, J.; Montes-Rojas, G. Unconditional Quantile Partial Effects via Conditional Quantile Regression. Journal of Econometrics 2024, 105678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan, A.; Ullah, A. Nonparametric Econometrics 1999.

- Battiston, D.; Garcia-Domench, C.; Gasparini, L. Could an Increase in Education raise Income Inequality? Evidence for Latin America. Latin American Journal of Economics 2014, 51, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, F.; Lustig, N.; Ferreira, F. The Microeconomics of Income Distribution Dynamics; Oxford University Press: Washington, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, C.; Ziebarth, N.L. The Effects of the National War Labor Board on Labor Income Inequality. Working Paper.

- Newey, W.K.; McFadden, D. Engle, R.F., McFadden, D.L., Eds.; Large Sample Estimation and Hypothesis Testing. In Handbook of Econometrics; chapter 36; Elsevier, 1994; Vol. 4, pp. 2111–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux, T. Increasing residual wage inequality: Composition effects, noisy data, or rising demand for skill? American Economic Review 2006, 96(3), 461–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, P. The distribution and redistribution of income; Manchester University Press: Manchester, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For some theory, see [2]. |

| 2 | [8] develops a sensitivity analysis procedure that considers both the marginal and non-marginal (global) effects on unconditional quantiles when covariates are discrete. |

| 3 | Another interesting aspect of UQEs is that there is a variety of methods to estimate them. Indeed, [1] rigorously derive three methods. |

| Effect | n | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | Var | MSE | Bias | Var | MSE | ||

| 50 | -0.0044 | 0.7563 | 0.7564 | -0.1031 | 2.9639 | 2.9745 | |

| 100 | 0.0081 | 0.3482 | 0.3483 | -0.0416 | 1.3842 | 1.3860 | |

| Location | 500 | -0.0086 | 0.0547 | 0.0548 | -0.0260 | 0.2176 | 0.2183 |

| 1000 | -0.0066 | 0.0299 | 0.0299 | -0.0184 | 0.1153 | 0.1157 | |

| 5000 | -0.0005 | 0.0062 | 0.0062 | 0.0020 | 0.0252 | 0.0252 | |

| 50 | -0.1141 | 2.2196 | 2.2326 | 0.0156 | 6.9623 | 6.9625 | |

| 100 | -0.1114 | 1.0436 | 1.0560 | 0.0144 | 3.3553 | 3.3555 | |

| Scale | 500 | -0.0601 | 0.2052 | 0.2088 | -0.0307 | 0.6320 | 0.6329 |

| 1000 | -0.0418 | 0.1078 | 0.1096 | -0.0195 | 0.3407 | 0.3411 | |

| 5000 | -0.0088 | 0.0205 | 0.0206 | -0.0039 | 0.0606 | 0.0606 | |

| 50 | -0.1185 | 3.5751 | 3.5891 | -0.0876 | 10.4689 | 10.4766 | |

| 100 | -0.1033 | 1.7181 | 1.7288 | -0.0273 | 5.2379 | 5.2387 | |

| Both | 500 | -0.0688 | 0.2923 | 0.2970 | -0.0568 | 0.8887 | 0.8920 |

| 1000 | -0.0485 | 0.1612 | 0.1635 | -0.0379 | 0.4704 | 0.4718 | |

| 5000 | -0.0094 | 0.0324 | 0.0325 | -0.0019 | 0.0882 | 0.0883 | |

| 50 | 0.0048 | 0.1453 | 0.1453 | -0.0455 | 0.5998 | 0.6019 | |

| 100 | 0.0112 | 0.0658 | 0.0659 | -0.0179 | 0.2760 | 0.2763 | |

| Asymmetric | 500 | 0.0016 | 0.0107 | 0.0107 | -0.0098 | 0.0439 | 0.0440 |

| () | 1000 | 0.0019 | 0.0057 | 0.0057 | -0.0066 | 0.0235 | 0.0236 |

| 5000 | 0.0033 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | 0.0018 | 0.0052 | 0.0052 | |

| 50 | -0.0044 | 0.7563 | 0.7564 | -0.1031 | 2.9639 | 2.9745 | |

| 100 | 0.0081 | 0.3482 | 0.3483 | -0.0416 | 1.3842 | 1.3860 | |

| Asymmetric | 500 | -0.0086 | 0.0547 | 0.0548 | -0.0260 | 0.2176 | 0.2183 |

| () | 1000 | -0.0066 | 0.0299 | 0.0299 | -0.0184 | 0.1153 | 0.1157 |

| 5000 | -0.0005 | 0.0062 | 0.0062 | 0.0020 | 0.0252 | 0.0252 | |

| 50 | -0.0365 | 4.3397 | 4.3410 | -0.2329 | 16.0205 | 16.0748 | |

| 100 | -0.0086 | 2.0279 | 2.0280 | -0.0939 | 7.6135 | 7.6223 | |

| Asymmetric | 500 | -0.0350 | 0.3114 | 0.3127 | -0.0665 | 1.1873 | 1.1917 |

| () | 1000 | -0.0270 | 0.1729 | 0.1737 | -0.0473 | 0.6259 | 0.6281 |

| 5000 | -0.0059 | 0.0362 | 0.0363 | 0.0031 | 0.1357 | 0.1357 | |

| Effect | n | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | Var | MSE | Bias | Var | MSE | ||

| 50 | 0.0126 | 0.7075 | 0.7077 | 0.0170 | 3.8324 | 3.8327 | |

| 100 | 0.0100 | 0.2943 | 0.2944 | 0.0197 | 1.6137 | 1.6140 | |

| Location | 500 | 0.0077 | 0.0566 | 0.0567 | 0.0074 | 0.3119 | 0.3119 |

| 1000 | 0.0036 | 0.0266 | 0.0266 | 0.0085 | 0.1438 | 0.1439 | |

| 5000 | 0.0002 | 0.0057 | 0.0057 | -0.0035 | 0.0298 | 0.0299 | |

| 50 | -0.1601 | 1.8447 | 1.8704 | -0.0454 | 7.8484 | 7.8505 | |

| 100 | -0.1201 | 0.9508 | 0.9652 | -0.0340 | 3.9788 | 3.9800 | |

| Scale | 500 | -0.0499 | 0.2079 | 0.2104 | -0.0449 | 0.8343 | 0.8364 |

| 1000 | -0.0381 | 0.0933 | 0.0947 | 0.0000 | 0.3934 | 0.3934 | |

| 5000 | -0.0040 | 0.0209 | 0.0209 | 0.0034 | 0.0845 | 0.0845 | |

| 50 | -0.1477 | 2.2522 | 2.2741 | -0.0286 | 5.7489 | 5.7497 | |

| 100 | -0.1104 | 1.2147 | 1.2268 | -0.0144 | 3.1012 | 3.1014 | |

| Both | 500 | -0.0424 | 0.2608 | 0.2626 | -0.0375 | 0.6949 | 0.6963 |

| 1000 | -0.0347 | 0.1159 | 0.1171 | 0.0084 | 0.3021 | 0.3022 | |

| 5000 | -0.0040 | 0.0265 | 0.0265 | -0.0002 | 0.0645 | 0.0645 | |

| 50 | 0.0137 | 0.1493 | 0.1495 | 0.0089 | 0.8879 | 0.8880 | |

| 100 | 0.0118 | 0.0617 | 0.0618 | 0.0109 | 0.3816 | 0.3817 | |

| Asymmetric | 500 | 0.0084 | 0.0118 | 0.0119 | 0.0065 | 0.0728 | 0.0729 |

| () | 1000 | 0.0063 | 0.0056 | 0.0056 | 0.0048 | 0.0342 | 0.0343 |

| 5000 | 0.0036 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | 0.0000 | 0.0071 | 0.0071 | |

| 50 | 0.0126 | 0.7075 | 0.7077 | 0.0170 | 3.8324 | 3.8327 | |

| 100 | 0.0100 | 0.2943 | 0.2944 | 0.0197 | 1.6137 | 1.6140 | |

| Asymmetric | 500 | 0.0077 | 0.0566 | 0.0567 | 0.0074 | 0.3119 | 0.3119 |

| () | 1000 | 0.0036 | 0.0266 | 0.0266 | 0.0085 | 0.1438 | 0.1439 |

| 5000 | 0.0002 | 0.0057 | 0.0057 | -0.0035 | 0.0298 | 0.0299 | |

| 50 | -0.0075 | 3.6517 | 3.6517 | 0.0299 | 17.5340 | 17.5348 | |

| 100 | -0.0053 | 1.5628 | 1.5629 | 0.0385 | 7.3357 | 7.3372 | |

| Asymmetric | 500 | 0.0035 | 0.3033 | 0.3033 | 0.0060 | 1.4437 | 1.4437 |

| () | 1000 | -0.0031 | 0.1410 | 0.1410 | 0.0189 | 0.6523 | 0.6526 |

| 5000 | -0.0038 | 0.0307 | 0.0307 | -0.0088 | 0.1349 | 0.1349 | |

| Effect | Gini | Theil | Atkinson(1) | Atkinson(2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | 0.6086*** | 0.5699*** | 0.6282*** | 1.2625*** |

| (0.0173) | (0.0218) | (0.0151) | (0.0233) | |

| Scale | -4.8003*** | -4.7931*** | -4.1004*** | -6.4685*** |

| (0.0824) | (0.1074) | (0.0714) | (0.1047) | |

| Both | -4.1918*** | -4.2232*** | -3.4722*** | -5.2060*** |

| (0.0777) | (0.1019) | (0.0681) | (0.1031) | |

| Asymmetric () | 0.3303*** | 0.3111*** | 0.3347*** | 0.6600*** |

| (0.0086) | (0.0109) | (0.0075) | (0.0115) | |

| Asymmetric () | 0.6086*** | 0.5699*** | 0.6282*** | 1.2625*** |

| (0.0173) | (0.0218) | (0.0151) | (0.0233) | |

| Asymmetric () | -0.1681*** | -0.2530*** | 0.0941*** | 0.7458*** |

| (0.0383) | (0.0494) | (0.0343) | (0.0563) |

| Effect | Gini | Theil | Atkinson(1) | Atkinson(2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | -0.4025*** | -0.3963*** | -0.3291*** | -0.4686*** |

| (0.0059) | (0.0068) | (0.0053) | (0.0092) | |

| Scale | -4.5253*** | -4.5701*** | -3.7068*** | -5.2172*** |

| (0.0929) | (0.1259) | (0.0826) | (0.1267) | |

| Both | -4.9278*** | -4.9664*** | -4.0358*** | -5.6858*** |

| (0.0959) | (0.1292) | (0.0853) | (0.1314) | |

| Asymmetric () | -0.0620*** | -0.0607*** | -0.0512*** | -0.0744*** |

| (0.0010) | (0.0011) | (0.0009) | (0.0015) | |

| Asymmetric () | -0.4025*** | -0.3963*** | -0.3291*** | -0.4686*** |

| (0.0059) | (0.0068) | (0.0053) | (0.0092) | |

| Asymmetric () | -2.8433*** | -2.8099*** | -2.3207*** | -3.2877*** |

| (0.0410) | (0.0482) | (0.0370) | (0.0626) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).