1. Introduction

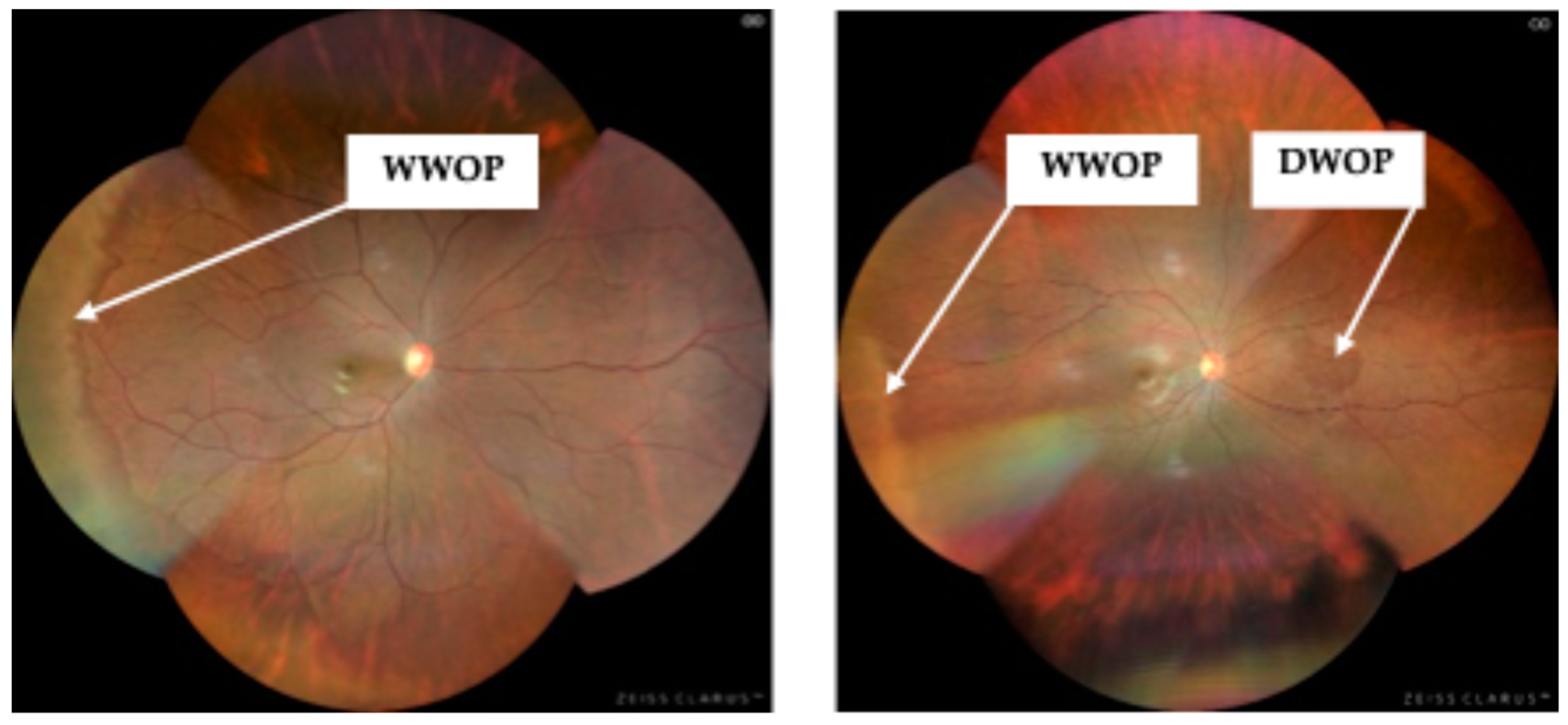

Peripheral retinal degenerations (PRD) comprise a broad group of abnormalities affecting the peripheral retina and choroid. While some PRDs, such as White Without Pressure (WWOP), and Dark Without Pressure (DWOP), are often considered clinically benign, others, most notably lattice degeneration (LD), retinal holes and tears, can increase the risk of retinal detachment. Reported prevalence rates of PRDs vary widely across studies, ranging from approximately 7% to 62% [

1,

2]. These degenerations typically develop during the second and third decades of life, with the risk of a retinal detachment increasing significantly with age, particularly in cases involving LD [

3,

4]. Therefore, early detection and ongoing monitoring of PRDs in younger adults is essential for reducing the risk of vision loss associated with retinal detachment.

To date, most population-based studies investigating PRDs have been conducted on Asian populations with myopia, with findings indicating a strong association between PRDs, high myopia, and longer ALs [

2,

5,

6,

7,

8].

At birth, the average axial length (AL) is approximately 16 mm, increasing to about 24 mm by early adulthood [

9], with further elongation being associated with the progression of myopia and a range of retinal pathologies. Research findings indicate that Southeast Asian subjects with ALs >26mm have a significantly higher odds ratio (OR) of developing a PRD (OR:3.37 – any peripheral change, OR:2.93 - WWOP and OR:1.44 - LD) [

2,

6], while ALs ≥30mm are positively correlated with retinal holes [

10]. Given that longer ALs are considered a strong predictor for PRD development, measuring AL could serve as a key biometric parameter for eye care practitioners to assess individuals at higher risk for PRDs.

Although PRDs are less frequently observed in hyperopic and emmetropic eyes, WWOP has been reported in up to 7% of hyperopes and 5% of emmetropes among young Southeast Asian adults [

8]. Degenerative retinoschisis, which is linked with hyperopia, affects approximately 5% of the population over the age of 20 [

11,

12], while LD has been reported in 1.4% of emmetropes [

8]. While several studies have explored the relationship between AL, refractive error (RE) and PRDs in Southeast Asian cohorts, to the best of our knowledge, research on this topic in young Australian adults with diverse ethnic backgrounds remains limited. Given the potential risk of sight-threatening complications associated with certain PRDs, further research into the relationship between PRDs, AL, and RE could greatly assist eye care practitioners in identifying high-risk individuals at an earlier age and implement preventative management strategies.

The gold standard for evaluating the mid and far peripheral retina, defined as the field of view between 60°-220° [

13], is a dilated fundus examination (DFE) with scleral indentation [

14]. However, in some sectors, Australian optometrists do not routinely dilate their patients without a clinical indication. Refractive error greater than -4.00D is used by many as this clinical indication. This may be due to factors such as the additional consultation time required or the temporary visual impairment it causes, which can be inconvenient for patients. With the advent of ultra-widefield (UWF) imaging techniques, it is now possible to capture more than 80% (200°) of the retina swiftly without mydriasis [

15]. This field of view is comparable to what an experienced eye care practitioner can achieve with a DFE and makes UWF imaging a very useful adjunct for screening and detecting potentially sight-threatening retinal conditions, most of which are found within the mid-peripheral 60°-200° area.

As UWF imaging becomes increasingly integrated into clinical practice in Australia, it could serve as a valuable screening tool in assessing the peripheral retina, particularly in cases where a DFE is not performed. This would then be the impetus for the ‘gold standard’ undilated examination.

The aims of this study were to:

Determine the prevalence of peripheral retinal degenerations in a young Australian adult population.

Assess the relationship between PRD, AL, and RE and their potential to predict the likelihood of a PRD being present.

2. Materials and Methods

Two hundred and twenty-one participants (442 eyes) from a mixed ethnicity population (Caucasian, Mediterranean, Sub-Saharan African, Indian subcontinental, Southeast Asian) were recruited via flyers posted on Deakin University Waurn Ponds optometry noticeboards between April 2022 and August 2024. Eligibility criteria required participants to be at least 18 years old, for consent purposes, and no older than 40 years, as this age range was used to define a ‘young adult’ [

16].

Those participants undergoing orthokeratology treatment or who had previously undergone refractive surgery were excluded, as both treatments affect AL measurements and the relationship between AL and RE. Additionally, participants with media opacities that would prevent clear ultra-widefield retinal imaging were also excluded.

This study employed a cross-sectional design, selected for its ability to examine a representative cross-section of the population and generate findings that could be generalised to the entire target population. Each participant attended a single session, during which demographic data (including age and gender information) were collected. RE and AL measurements were obtained for both eyes using the Lenstar® LS 900 (Haag-Streit, Köniz, Switzerland) and an open-field autorefractor (Shin-Nippon NVision-K 5001), respectively. The average of three AL readings was recorded in millimetres (mm), while RE measurements were recorded in dioptres (D). A four-image auto-montage (superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal) UWF digital image was captured for both eyes (without dilation), using the Clarus 500™ (Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc., Dublin, CA, USA).

UWF images captured with the ClarusTM 500 were downloaded, and two principal researchers independently assessed the images to identify any peripheral retinal degenerations. In cases of disagreement, consensus was reached through discussion, or the third principal investigator was consulted.

All peripheral retinal changes were classified and documented in an Excel spreadsheet using Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365 (Version 2409 Build 16.0.18025.20160). However, only PRDs known to be associated with retinal detachment (retinal holes and LD), along with those PRDs (WWOP & DWOP), commonly observed alongside these conditions, were used in the statistical analysis. While WWOP & DWOP typically have minimal retinal complications, their potential retinal detachment risk warrants consideration. WWOP, in particular, is associated with LD [

17], and both WWOP & DWOP are linked to longer ALs and high myopia - two key risk factors for retinal detachment [

7,

17].

Retinal changes not commonly associated with retinal detachment, including Congenital Hypertrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium (CHRPE) and Choroidal Naevi [

18,

19,

20], were also classified, but not included in the overall PRD statistical analysis.

Both eyes were included in the analysis to obtain the most accurate estimate of PRD prevalence, as PRDs can occur unilaterally or bilaterally [

11,

21,

22]. Each identified PRD was assigned a value of 1, while the absence of a PRD was recorded as 0. These data, along with demographic information (age and gender), AL, and RE measurements, were also recorded in the Excel spreadsheet. RE measurements were converted to spherical equivalent in dioptres (D) by adding the sum of the sphere power with half of the negative cylinder power and classified based on criteria from previous studies (

Table 1) [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. AL values were also binned and classified as per Khan et al.[

29] (

Table 2).

The Excel spreadsheet data was transferred to IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29.0.2.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) for further statistical analysis.

Descriptive statistics, Chi-square (χ²) and independent t-tests were conducted in SPSS to analyse the data. Binary logistic regression was used to evaluate the likelihood and OR for the presence of a PRD and the variables AL and RE. Logistic regression coefficients and intercept values obtained from SPSS were further utilised in Excel to calculate curve values, facilitating the plotting of logistic regression graphs. A significance level of p=0.05 was applied to all tests.

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was granted by Deakin University’s Faculty of Health Human Ethics Advisory Group (HEAG_H 15_2022) on 29th March 2022. Participants were all given a hard copy of the plain language statement and provided written consent for research participation before data was collected. Upon enrolment, participants were allocated a unique identifier to ensure all data remained anonymous. Referrals to an external eye care practitioner were provided for all cases where a PRD was noted, in order for participants to seek further independent clinical advice.

3. Results

There were 150 male eyes (33.9%) and 292 female eyes (66.1%) analysed in the study. The mean age of participants was 22.43±3.11 years (range 18-39 years old), with males averaging 22.52±3.17 years and females 22.38±3.10 years.

Participants without a PRD had a mean age of 22.43±3.15 years, while for those with a PRD, it was 22.39±2.74 years. Overall, no significant association was found between gender (χ2 (1)=2.399, p=0.121) or age (t(440)=0.073, p<0.942) and the presence of a PRD. The mean RE did not differ significantly between males and females (t(440)=-1.53, p<0.063), however, males had a slightly longer mean AL (24.45±1.17mm) compared to females (23.80±1.11mm), (t(440)= 5.714, p<0.001).

PRDs were detected in thirty-six eyes (8.15%), with eight eyes from males (1.81%) and twenty-eight from females (6.33%). The most commonly observed PRD were WWOP (

Figure 1a) and DWOP (

Figure 1b), each occurring in 3.39% (n=16/442) of cases (

Table 3). One participant had two different PRDs identified in the same eye, accounting for the thirty-seven PRDs reported in

Table 3.

Table 4 displays the PRD frequencies associated with AL and RE. PRD prevalence was 0.61% (n=1/165) in emmetropes, 2.86% (n=1/35) in hyperopes, and 14.05% (n=34/242) in myopes. Within the myopic group, PRD prevalence was 3.95% (n=6/152) for mild myopia, 22.06% (n=15/68) for moderate myopia, and 59.09% (n=13/22) for high myopia. For AL, PRD prevalence was 15.23% (n=30/197), for eyes longer than the mean AL of 24.02±1.17mm.

The overall mean RE was -1.43±2.21D. For eyes without a PRD, the mean RE was -1.13±1.94D, while for eyes with a PRD, it was -4.78±2.33D. The largest hyperopic RE observed with a PRD was +0.75D, while the lowest for myopia was -1.00D. For the emmetropic eyes, one PRD was noted at +0.50D. PRDs were significantly associated with a moderate to high myopic RE (t(10.62)=0.035, p<0.001) (

Table 5).

For eyes without a PRD, the mean AL was 23.89±1.08mm, whereas for eyes with a PRD, it was 25.46±1.13mm. Whilst the shortest AL with a PRD was 22.96mm, PRDs were significantly associated with longer axial lengths (t(440)=0.643, p<0.001) (

Table 5).

Binary logistic regression analysis showed that the risk of having a PRD compared to emmetropia significantly increased with higher degrees of myopia (moderate myopia OR:3.84; 95% CI, 1.79-5.86; p<0.001, high myopia OR:5.47; 95% CI, 3.33-7.61; p<0.001) (

Table 6). Moreover, PRD risk also increased with axial elongation >24.50mm and remained statistically significant across all AL classifications - mild, moderate and high myopia (p<0.001) compared with ALs between 23.50mm and 24.50mm (emmetropia). Interestingly, the OR for ALs over 26.50mm (high myopia) was slightly lower than that for ALs between 25.50mm and 26.50mm (moderate myopia) (

Table 6).

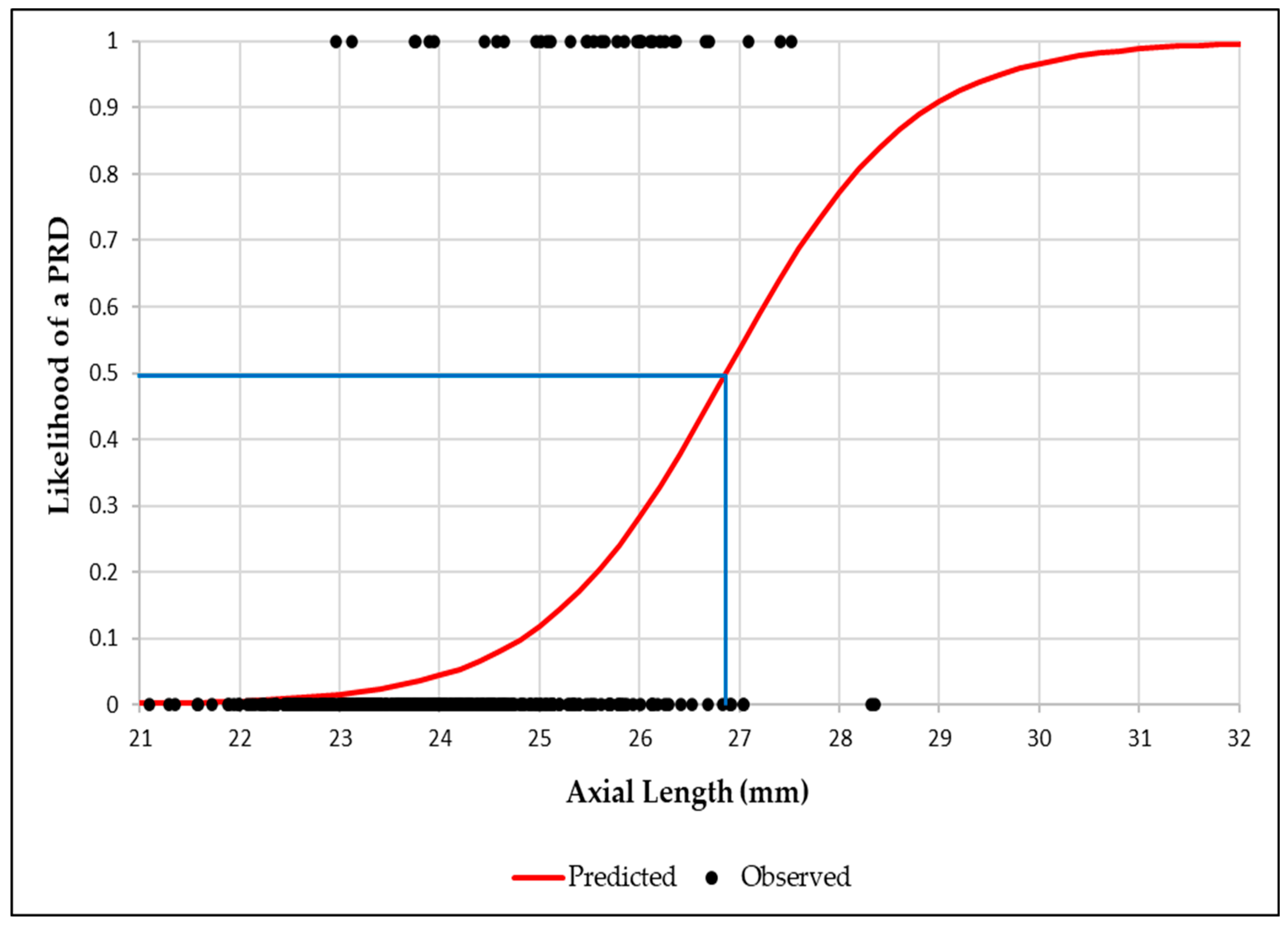

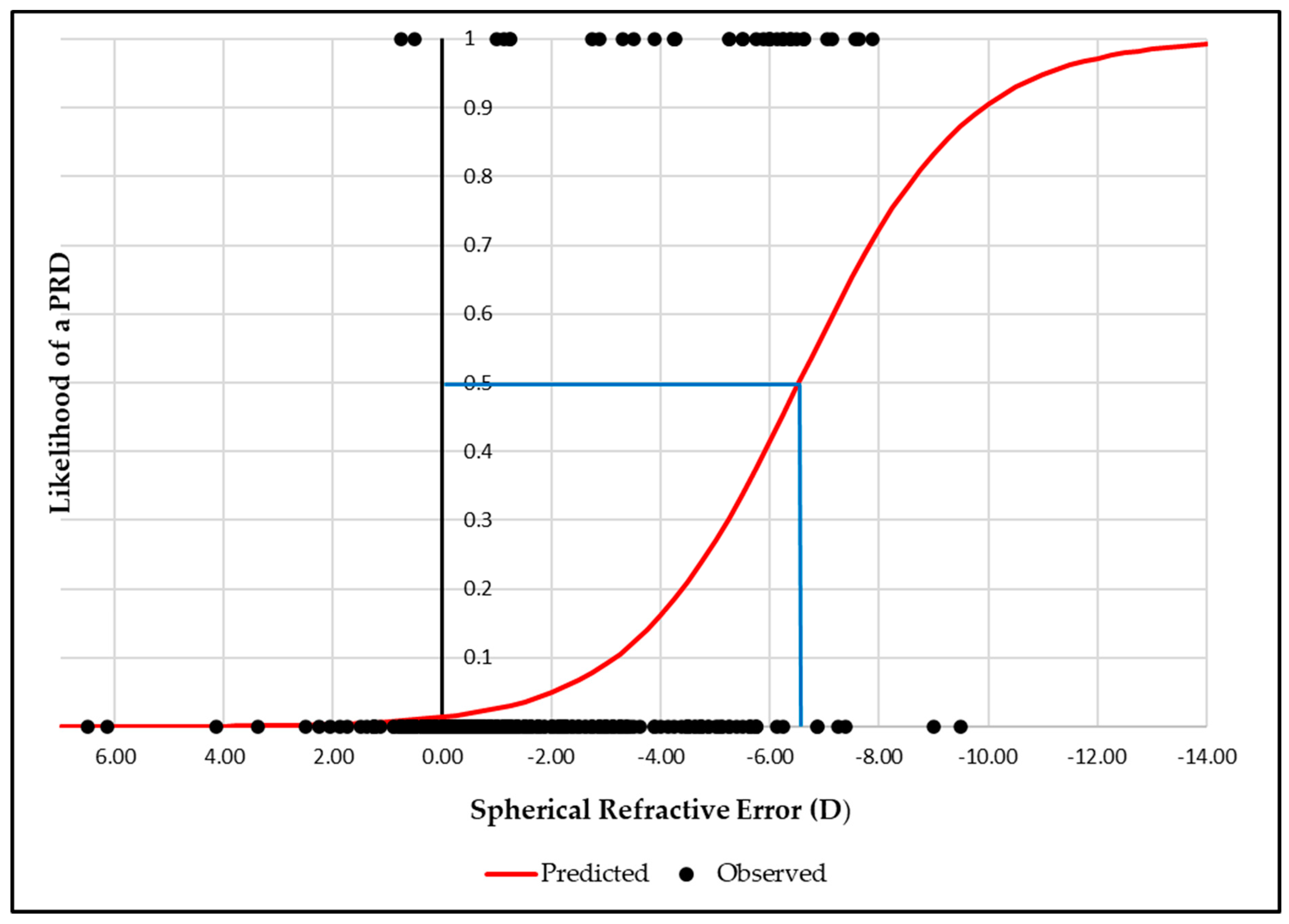

Binary logistic regression graphs showed that the likelihood of a PRD reached 50% at an AL of 26.9 mm, increasing to 95% at 29.6mm (

Figure 2). Similarly, for RE, a 50% likelihood was observed at -6.50D, rising to 95% at -11.00D (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

The clinical significance of PRDs stems from their association with having an increased risk of retinal detachment. Although many PRDs, such as WWOP and DWOP, are not directly linked to retinal detachment, unlike LD or retinal holes, their potential risk still merits attention. This is because WWOP is associated with LD [

17], and both WWOP & DWOP are connected to longer ALs and high myopia - two major risk factors for retinal detachment development [

7,

17].

In this study, PRDs were identified in 8.15% of eyes among young Australian adults aged 18 to 40 years from a diverse ethnic background. Although the literature regarding PRDs in this age group remains somewhat limited, our findings closely align with Michaud and Forcier [

1], who reported a prevalence of 7.74% in the Canadian adult population, a country with similar demographics to Australia [

30]. Higher prevalence rates have been reported in other studies; however, direct comparisons to this study are challenging due to differences in study populations. Many of these studies included older participants, a Southeast Asian demographic and/or exclusively recruited myopic individuals - a group known to have an increased predisposition to developing PRDs [

2,

6,

7,

8].

The most frequently observed PRDs in this study were WWOP and DWOP, each with a prevalence of 3.39%. This is lower than the prevalence rates reported in the current literature, which range from approximately 6% to 46% [

6,

7,

8,

21,

31] for WWOP and 30% for DWOP [

7]. However, as previously mentioned, many of these studies predominantly recruited participants with high myopia, which may limit the generalisability of their findings to the broader population. Dhull et al. [

21], reported a WWOP prevalence rate of 6.11%, a value closer to the findings of our study. This similarity is likely attributable to the inclusion of a more balanced distribution of refractive errors incorporating myopia, emmetropia and hyperopia. However, in contrast, Zhang et al. [

8], reported a considerably higher WWOP prevalence rate of 15.5%, despite recruiting participants with refractive errors similar to those in our study.

Dhull et al. [

21] found a retinal hole prevalence of 0.6%, comparable to our finding of 0.5%, whereas other studies have reported higher prevalence rates ranging from 1.67% to 6.20% [

31,

32,

33]. The prevalence of LD in this study was also relatively low at 0.7%, which is in contrast to previously reported rates varying between 2% to 20% [

2,

6,

8,

10,

31,

32,

33]. Since LD is strongly associated with longer ALs and high myopia, this lower prevalence is not unexpected, given that our study had a smaller proportion of participants with high myopia compared to these other studies.

The study reinforces the well-established association between AL, high myopia, and the increased risk of developing PRDs [

2,

10,

32,

34]. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the likelihood of a PRD occurrence in a young Australian adult population with diverse ethnic backgrounds and a broad range of ALs and RE. Our logistic regression analysis of RE found that both moderate myopia (OR:3.84, p<0.001) and high myopia (OR:5.37, p<0.001) were found to significantly increase the risk of a PRD being present compared to emmetropes. This is consistent with the findings of Zhang et al. [

8], who reported a similar risk for moderate myopia (OR:3.64, p<0.001, but a higher risk for high myopia (OR:10.58, p<0.001). However, unlike Zhang et al. [

8], our study did not identify mild myopia as a significant risk factor.

For AL, logistic regression results indicated that eye elongation >24.50mm, classified in this study as mild, moderate and high myopia, was also associated with an increased risk of PRD development compared to ALs between 23.50mm and 24.50mm (emmetropia). This is interesting, as several studies have typically associated PRDs with ALs >26mm [

34,

35], while Akbani et al. [

5], reported the highest occurrence of PRDs in eyes with ALs between ALs of 28mm and 30mm.

Clinically, this is an important observation, as while extensive research has established a strong linear correlation between myopia and increased AL (i.e., the higher the myopia, the longer the AL [

36]), there can sometimes be discordance between these two parameters. For instance, some individuals with low myopia may have a longer AL than those with moderate myopia. This variation is often due to differences in the refractive components of the cornea and the lens, which can vary from one individual to the next. This highlights the importance of measuring AL alongside RE to better assess the risk of a PRD. If AL measurement is not feasible, reliance on RE becomes necessary. Our results, however, challenge the conventional practice of undertaking a DFE to screen for peripheral retinal changes when RE exceeds -4.00D. Given the significant PRD risk for moderate myopia (OR:3.84, p<0.001), there is a valid argument for reconsidering the threshold for DFE to -3.00D. Bhat [

37] also reported a higher prevalence of PRDs, particularly LD, not only in individuals with high myopia but also in those with mild and moderate myopia, further supporting the case for lowering the RE threshold for dilation in young patients.

The advancement of UWF imaging has greatly facilitated the ability of eye care practitioners to visualise, evaluate, document and monitor peripheral retinal changes. Midena et al. [

38] demonstrated that four-quadrant UWF imaging using the Clarus

TM 500 images, performed through a dilated pupil, achieved 99% sensitivity and a 100% specificity in detecting peripheral retinal changes and retinal detachments, compared to binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO). Similarly, Karatepe Hashas et al. [

39], evaluated the use of UWF imaging for detecting retinal breaks with the Zeiss Clarus

TM 700, a newer model of the Clarus

TM 500 with the same field of view. They also found high sensitivity and specificity in detecting retinal breaks, however, detection rates varied based on the number of images analysed. When only a single image was reviewed, more than 50% of retinal breaks were missed, while at least 75% were detected when two images were analysed. The highest detection rate occurred when six images were reviewed. Since the Zeiss Clarus

TM 500 can automatically montage up to six images, expanding the field of view to 267° degrees, future research could investigate whether increasing the number of auto-montaged images from four to six influences prevalence rates and the likelihood of detecting a PRD.

Karatepe Hashas et al. [

39] also compared UWF-based detection of retinal breaks with traditional retinal examinations using dilation. Reviewers analysing only UWF images missed retinal breaks in 10-21% of cases, compared to those conducting traditional retinal examinations. Therefore, until UWF imaging can reliably capture the entire peripheral retina, it should be regarded as an adjunct rather than a replacement for BIO in comprehensive ocular assessments. However, in situations where a DFE is not feasible, using UWF imaging to screen at-risk individuals for PRDs could be extremely valuable.

Participants were primarily recruited from a university optometry course. Since higher education attainment has been associated with myopia and the development of longer ALs [

28,

40], this recruitment approach may limit the generalisability of the findings. Additionally, participants did not undergo a dilated fundus examination using BIO, which, as aforementioned, is widely regarded as the gold standard for evaluating the peripheral retinal fundus, especially when combined with scleral depression. Although the Clarus

TM 500 can capture a field of view up to 200° with four montaged images through an undilated pupil, some PRDs may not have been detected, potentially leading to an underestimation of the prevalence.

5. Conclusions

PRDs appear to be less prevalent in a mixed population of young Australian adults compared to Asian populations. Validating existing literature, key risk factors for developing PRDs were longer ALs, particularly greater than 24.5mm, and moderate to high myopic refractive errors. However, most importantly, since AL was found to have a significantly stronger association with PRDs across myopia classifications than RE, incorporating AL measurements alongside RE assessments in clinical practice could enhance eye care practitioners’ ability to predict PRD risk and determine the most appropriate time for retinal evaluation. While a dilated biomicroscopic retinal examination remains the gold standard for assessing the retina, UWF imaging could serve as a suitable alternative when dilation is not possible, enabling early detection of PRDs and reducing the risk of sight-threatening complications, such as retinal detachment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.W. and N.H.; Methodology, N.W., N.H, and J.A.; Investigation, N.W, and N.H.; Formal Analysis, N.W, N.H., and J.A.; Data Curation, N.W., J.A., and N.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, N.W., and NH; Writing—review and editing, N.W., N.H., and J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Faculty of Health Human Ethics Advisory Group of Deakin University (HEAG H 15 2022 on 29th March 2022)

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the following individuals who assisted with image acquisition, axial length and refractive error quantification. Nivya Benny, Xenitty Crouch, Ooh Jin Kim, Chidera Okeleke, Bhumin Parekh, Shenara Perera, Nadine Rostom, Alex Taking, Elaina Truong, Salman Umar, Alexandra Birrell, Isabel Chuquipiondo, Anthony Ho, Kiranjot Kaur, Shanya Navaratne, Hayden Nguyen, Mai Phan, Sameer Raza, Tahiyat Tasnim, Thomas Tran, Georgia Alberti, Stephanie Cabusao, Catherine Campbell, Jocelyn Dao, Emefa Fiadonu, Tira Kyreakou, Jassica Vijayakumar, Jocelyn Wong, and Caren Zhu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PRD |

Peripheral Retinal Degeneration |

| RE |

Refractive Error |

| AL |

Axial Length |

| UWF |

Ultra-widefield |

| WWOP |

White Without Pressure |

| DWOP |

Dark Without Pressure |

| LD |

Lattice Degeneration |

| CHRPE |

Congenital Hypertrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| BIO |

Binocular Indirect Ophthalmoscopy |

| DFE |

Dilated Fundus Examination |

References

- Michaud L, Forcier P. Prevalence of asymptomatic ocular conditions in subjects with refractive-based symptoms. Journal of Optometry. 2014;7(3):153-60. [CrossRef]

- Cheng SC, Lam CS, Yap MK. Prevalence of myopia-related retinal changes among 12-18 year old Hong Kong Chinese high myopes. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2013;33(6):652-60. [CrossRef]

- Lewis H. Peripheral retinal degenerations and the risk of retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(1):155-60. [CrossRef]

- Mrejen S, Ledesma-Gil G, Engelbert M. Peripheral Retinal Abnormalities. In: Spaide RF, Ohno-Matsui K, Yannuzzi LA, editors. Pathologic Myopia. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 329-46.

- Akbani MI, Reddy KRK, Vishwanath K, Saleem H. Association of Posterior Pole Degeneration with Axial Length in the Cases of Myopia- A Cross Sectional Study. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2014;5(2):64-7.

- Chen DZ, Koh V, Tan M, Tan CS, Nah G, Shen L, et al. Peripheral retinal changes in highly myopic young Asian eyes. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96(7):e846-e51. [CrossRef]

- Yu H, Luo H, Zhang X, Sun J, Zhong Z, Sun X. Analysis of White and Dark without Pressure in a Young Myopic Group Based on Ultra-Wide Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. J Clin Med. 2022;11(16). [CrossRef]

- Zhang T, Wei YT, Huang WB, Liu RJ, Zuo YJ, He LW, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of peripheral myopic retinopathy in Guangzhou office workers. Int J Ophthalmol. 2018;11(8):1390-5. [CrossRef]

- Nilagiri VK, Lee SS-Y, Lingham G, Charng J, Yazar S, Hewitt AW, et al. Distribution of Axial Length in Australians of Different Age Groups, Ethnicities, and Refractive Errors. Translational Vision Science & Technology. 2023;12(8):14-. [CrossRef]

- Lam DS, Fan DS, Chan WM, Tam BS, Kwok AK, Leung AT, Parsons H. Prevalence and characteristics of peripheral retinal degeneration in Chinese adults with high myopia: a cross-sectional prevalence survey. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82(4):235-8. [CrossRef]

- Bowling B. Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology: A systematic approach 8th ed: W B Saunders; 2016.

- Byer NE. Clinical Study of Senile Retinoschisis. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1968;79(1):36-44. [CrossRef]

- Patel SN, Shi A, Wibbelsman TD, Klufas MA. Ultra-widefield retinal imaging: an update on recent advances. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2020;12:2515841419899495. [CrossRef]

- Nixon TRW, Davie RL, Snead MP. Posterior vitreous detachment and retinal tear - a prospective study of community referrals. Eye (Lond). 2024;38(4):786-91. [CrossRef]

- Abadia B, Desco MC, Mataix J, Palacios E, Navea A, Calvo P, Ferreras A. Non-Mydriatic Ultra-Wide Field Imaging Versus Dilated Fundus Exam and Intraoperative Findings for Assessment of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment. Brain Sci. 2020;10(8). [CrossRef]

- Klimczuk A. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Theory in Psychology.

- Karlin DB, Curtin BJ. Peripheral chorioretinal lesions and axial length of the myopic eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;81(5):625-35. [CrossRef]

- Thiagalingam S, Wang JJ, Mitchell P. Absence of Change in Choroidal Nevi Across 5 Years in an Older Population. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122(1):89-93. [CrossRef]

- Chien JL, Sioufi K, Surakiatchanukul T, Shields JA, Shields CL. Choroidal nevus: a review of prevalence, features, genetics, risks, and outcomes. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28(3):228-37. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Moore AT. Congenital focal abnormalities of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(11):1973-88. [CrossRef]

- Dhull V, Manisha N, Sundan S, Rachana G. A Study of White Without Pressure Peripheral Retinal Lesions in Emmetropia, Myopia and Hypermetropia. Saudi J Med Pharm Sci. 2019;5(6):503-11.

- Celorio JM, Pruett RC. Prevalence of lattice degeneration and its relation to axial length in severe myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111(1):20-3. [CrossRef]

- Galvis V, Tello A, Otero J, Serrano A, Gómez L, Camacho Lopez P, Lopez-Jaramillo P. Prevalence of refractive errors in Colombia: MIOPUR study. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2018;102:bjophthalmol-2018. [CrossRef]

- Crim N, Esposito E, Monti R, Correa LJ, Serra HM, Urrets-Zavalia JA. Myopia as a risk factor for subsequent retinal tears in the course of a symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment. BMC Ophthalmology. 2017;17(1):226. [CrossRef]

- Wajuihian S, Hansraj R. Refractive Error in a Sample of Black High School Children in South Africa. Optometry and Vision Science. 2017;94:1. [CrossRef]

- Pu J, Fang Y, Zhou Z, Chen W, Hu J, Jin S, et al. The Impact of Parental Myopia and High Myopia on the Hyperopia Reserve of Preschool Children. Ophthalmic Research. 2023;67(1):115-24. [CrossRef]

- Lim LS, Cheung CY-l, Lin X, Mitchell P, Wong TY, Mei-Saw S. Influence of Refractive Error and Axial Length on Retinal Vessel Geometric Characteristics. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2011;52(2):669-78. [CrossRef]

- Foster PJ, Broadway DC, Hayat S, Luben R, Dalzell N, Bingham S, et al. Refractive error, axial length and anterior chamber depth of the eye in British adults: the EPIC-Norfolk Eye Study. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2010;94(7):827-30. [CrossRef]

- Khan MH, Lam AKC, Armitage JA, Hanna L, To CH, Gentle A. Impact of Axial Eye Size on Retinal Microvasculature Density in the Macular Region. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8). [CrossRef]

- Beaujot R, McDonald P. Introduction: Comparative demography of Australia and Canada. Canadian Studies in Population. 2016;43(1-2):1-4.

- Lai TY, Fan DS, Lai WW, Lam DS. Peripheral and posterior pole retinal lesions in association with high myopia: a cross-sectional community-based study in Hong Kong. Eye (Lond). 2008;22(2):209-13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Yang F, Chen S, Shi T. Peripheral and posterior pole retinal changes in highly myopic Chinese children and adolescents. BMC Ophthalmology. 2024;24(1):65. [CrossRef]

- Bansal AS, Hubbard GB, 3rd. Peripheral retinal findings in highly myopic children < or =10 years of age. Retina. 2010;30(4 Suppl):S15-9. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen HTT, Hoang TT, Pham CM, Nguyen TM, Dang TM, Fricke TR. Prevalence and related factors of myopic retinopathy - a hospital-based cross-section study in Vietnam. Clin Exp Optom. 2023;106(4):427-30. [CrossRef]

- Pierro L, Camesasca FI, Mischi M, Brancato R. Peripheral retinal changes and axial myopia. Retina. 1992;12(1):12-7. [CrossRef]

- Tideman JWL, Snabel MCC, Tedja MS, van Rijn GA, Wong KT, Kuijpers RWAM, et al. Association of Axial Length With Risk of Uncorrectable Visual Impairment for Europeans With Myopia. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2016;134(12):1355-63. [CrossRef]

- Bhat S. Comparing the prevalence of lattice degeneration and requirement of barrage laser in different grades of myopia. Kerala Journal of Ophthalmology. 2024;36(1):53-6. [CrossRef]

- Midena E, Marchione G, Di Giorgio S, Rotondi G, Longhin E, Frizziero L, et al. Ultra-wide-field fundus photography compared to ophthalmoscopy in diagnosing and classifying major retinal diseases. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):19287. [CrossRef]

- Karatepe Hashas AS, Popovic Z, Abu-Ishkheidem E, Bond-Taylor M, Svedberg K, Jarar D, Zetterberg M. A new diagnostic method for retinal breaks in patients with posterior vitreous detachment: Ultra-wide-field imaging with the Zeiss Clarus 700. Acta Ophthalmol. 2023;101(6):627-35. [CrossRef]

- Mirshahi A, Ponto KA, Hoehn R, Zwiener I, Zeller T, Lackner K, et al. Myopia and level of education: results from the Gutenberg Health Study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(10):2047-52. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).