1. Introduction

Myopia is an emerging global health issue, with projections estimating that by 2050, 50% of the world’s population will be myopic and 10% will develop high myopia [

1]. This growing prevalence, accentuated by behavioral changes particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, is expected to increase visual impairment and impose significant socioeconomic burdens [

2,

3].

In high myopia, elongation of the eyeball induces structural eye changes, including the optic nerve head (ONH) [

4]. This involves ovalization of the optic disc [

5], along with the presence and accentuation of gamma peripapillary atrophy (γPPA), which is characterized by an atrophic region adjacent to the optic disc, most commonly located temporally in myopic eyes, and resulting from a mismatch between the termination of Bruch’s membrane and the optic disc opening [

4,

6].

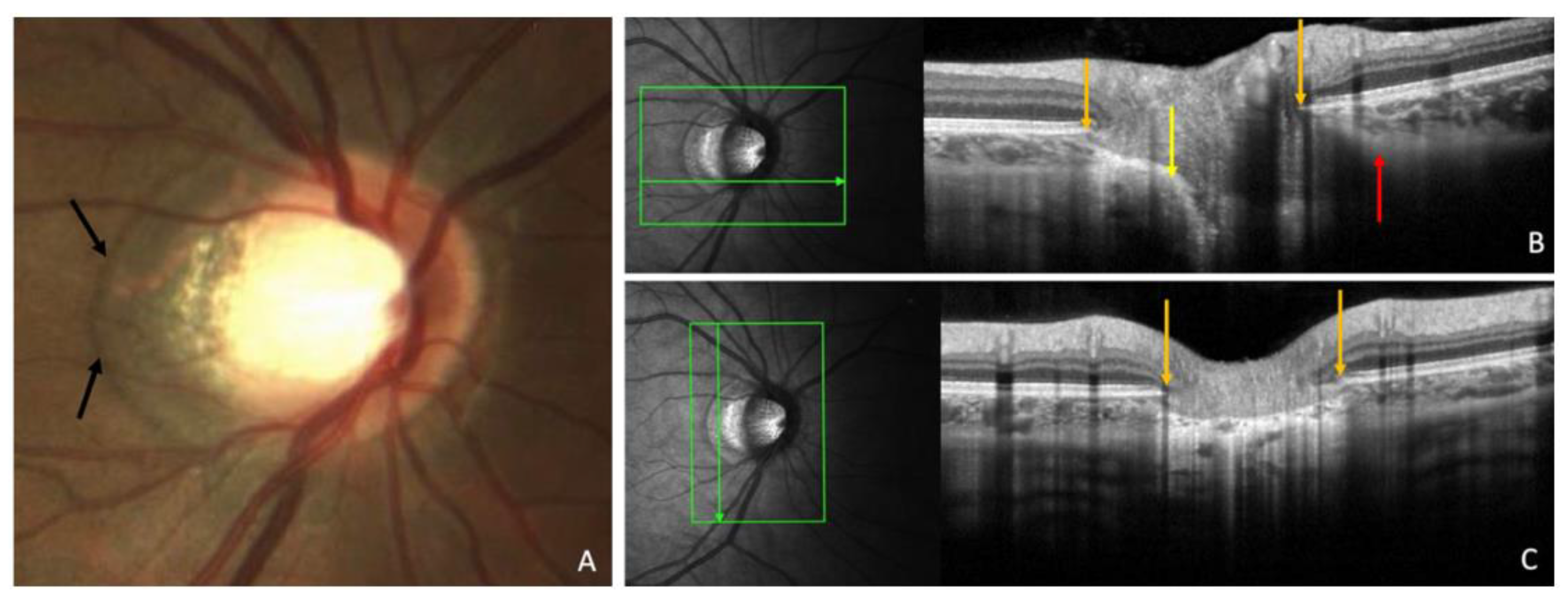

As illustrated in

Figure 1, γPPA represents the zone between the end of Bruch’s membrane and the optic disc border [

7].

Histological and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) imaging studies confirm the absence of Bruch’s membrane in γPPA [

8,

9], which extends from the edge of Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO) to the anterior scleral opening (ASO). The degree of optic disc deformation is approached by the ovality index (OI), calculated as the ratio of the shortest to longest disc diameters [

10].

Recent biomechanical hypothesis suggests that the traction force exerted by the optic nerve sheaths (ONS) may contribute to axial elongation in myopia [

11]. This hypothesis draws on prior research demonstrating that the ONS’s traction force aligns with the magnitude of forces generated by the extraocular muscles and acts in the axial direction. Such traction is proposed to induce significant peripapillary forces, particularly during adduction movements exceeding 26 degrees [

12].

Such forces have been implicated in a spectrum of clinically relevant peripapillary myopic complications, in particular visual impairment or associated visual field defects mimicking those of glaucomatous optic neuropathy [

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, the factors that determine these peripapillary complications remain to be clarified.

Both the OI and γPPA are proposed to quantify structural ONH and peripapillary changes in myopic eyes. Biometric factors such as interpupillary distance (IPD), which has been shown to influence vergence amplitudes [

17], may also influence adduction amplitudes. Based on geometric considerations, we hypothesize that a larger IPD might be associated with greater adduction, increasing therefore optic nerve traction and favoring these structural alterations. However, no study has explored this relationship as far as we know.

The objective of this study was to investigate whether IPD is associated with measures of ONH and peripapillary changes, namely the OI and γPPA.

2. Materials and Methods

This was an observational, cross-sectional, monocentric study approved by the Ethics Committee of Erasmus Hospital (Brussels, Belgium), (reference P2024/450) and the institutional review board (reference SRB2024239). The study complied with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and written informed consent was acquired from all participants.

Inclusion Population

Subjects without a history of strabismus, strabismus surgery, posterior segment surgery or trabeculectomy, and aged 18 years or older, were recruited over 2 months (between January and February 2025). Participants were approached during their routine visit to our glaucoma outpatient department.

The classification of myopia was primarily based on spherical equivalent (SE ≤ −0.50 D), in accordance with the International Myopia Institute [

18]. A target of at least 50 myopic eyes was set, as this is a pilot study and the correlation between IPD and the values of peripapillary myopic changes has never been studied before. In cases where refractive error (RE) data were missing or unreliable, an axial length (AL) threshold of ≥ 26.0 mm, defining high myopia was used to classify the eye as myopic. This methodological choice was made to ensure that only clearly myopic eyes were classified as such, despite the absence or unreliability of RE data.

This includes the following situations: (a) eyes with a history of refractive surgery, for which preoperative refraction was not available for analysis; (b) eyes with a history of cataract surgery without available preoperative remote refraction from cataract documentation; and (c) eyes with unoperated but clinically significant cataract at the time of inclusion, for which no reliable pre-cataract refraction could be retrieved. This approach allowed for the classification of myopic eyes based on AL, even when refractive data were not available or not reliable.

General and Ocular Data

Age and gender were recorded for each subject. Data from the comprehensive ophthalmic examination were retrieved for both eyes of the subjects. For each eye, the following parameters were recorded: RE in SE, AL values using IOL Master® (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany) and IPD measurement with auto-refraction (Nidek TONOREF2 RKT 2014, Japan). Color fundus pictures using a Clarus® (Carl Zeiss Meditec) and Spectral Domain OCT imaging using Spectralis® S3300 model, version 6.16.2 (Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) were analyzed.

Color Fundus Photographs

These images were used to exclude eyes with retinal or optic nerve anomalies unrelated to myopia or glaucoma, in order to eliminate potential confounding factors in the interpretation of structural findings.

Eye Selection

Although a full ophthalmic examination was available for both eyes of each participant, only the right eye was included in the study unless it met an exclusion criterion, in which case the left eye was used instead. This approach was adopted to account for inter-eye correlation.

OCT Imaging

Radial OCT section acquisitions using the commercialized Glaucoma Premium Edition module of the Spectralis® performed for routine glaucoma documentation were used, specifically the 24 radial line B-scans centered on optic disc of each participant for tomographic analyses of the peripapillary region.

OCT Analysis

OCT sections and infrared images were opened in display mode, then γPPA width and OI were measured.

Figure 2,

Figure 4, and

Figure 5 are from the same patient to ensure consistency in anatomical representation across measurements.

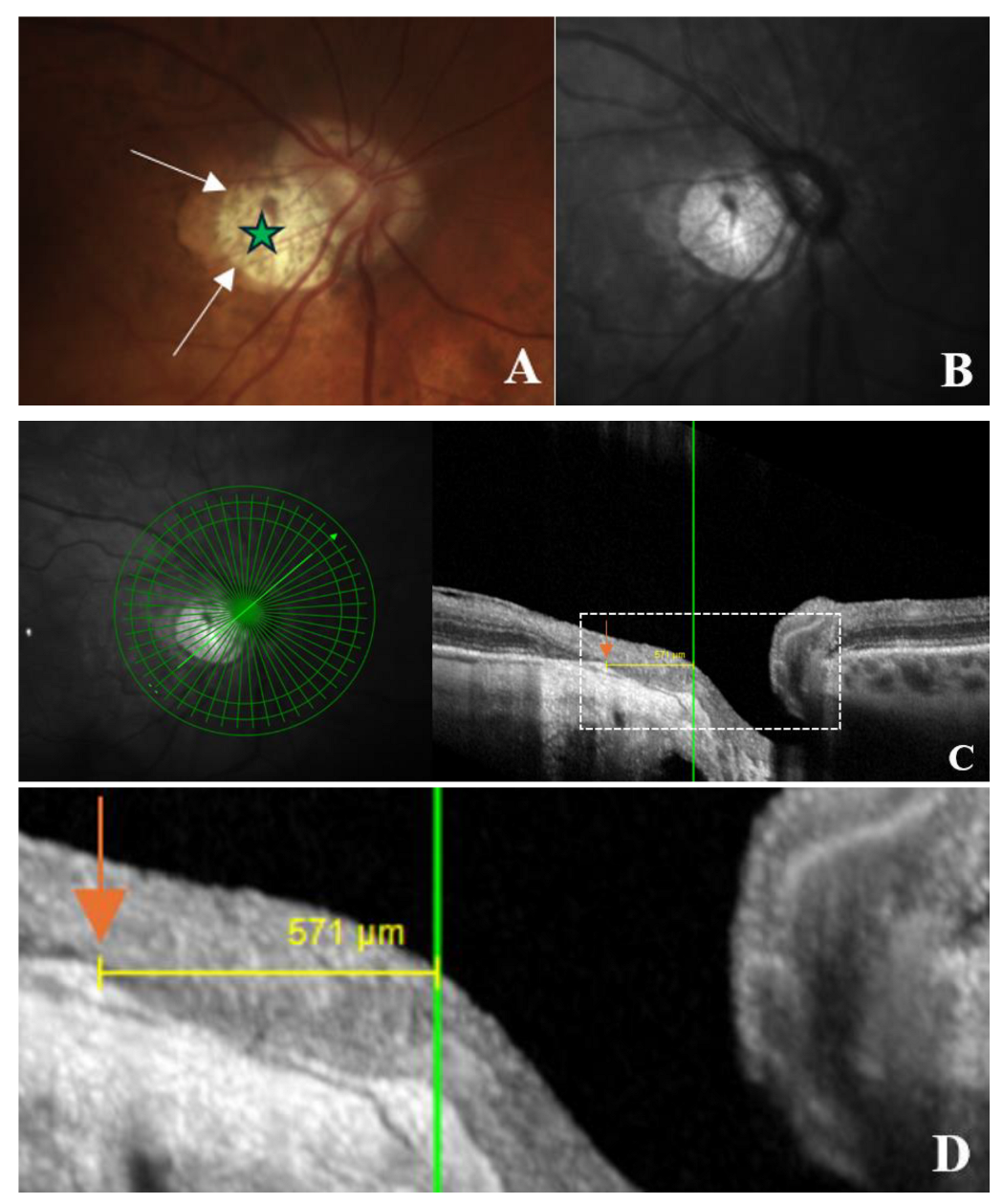

Figure 2.

OCT-based measurement of γ-zone peripapillary atrophy (γPPA) width. (A) Fundus image illustrating the end of γPPA (white arrows) and temporal myopic conus (green star); (B) Infrared image without the radial line scan tool; (C) Section along the green arrow in the infrared image. The γPPA is visualized as the atrophic zone between the Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO; orange arrow) and the anterior scleral opening (ASO; green line). The yellow arrows with calipers indicate the γPPA width measured along the short axis; (D) A magnified view of the white dashed rectangle in (C) is provided to improve the readability of the measurements. In this case, the γPPA measures 571 µm.

Figure 2.

OCT-based measurement of γ-zone peripapillary atrophy (γPPA) width. (A) Fundus image illustrating the end of γPPA (white arrows) and temporal myopic conus (green star); (B) Infrared image without the radial line scan tool; (C) Section along the green arrow in the infrared image. The γPPA is visualized as the atrophic zone between the Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO; orange arrow) and the anterior scleral opening (ASO; green line). The yellow arrows with calipers indicate the γPPA width measured along the short axis; (D) A magnified view of the white dashed rectangle in (C) is provided to improve the readability of the measurements. In this case, the γPPA measures 571 µm.

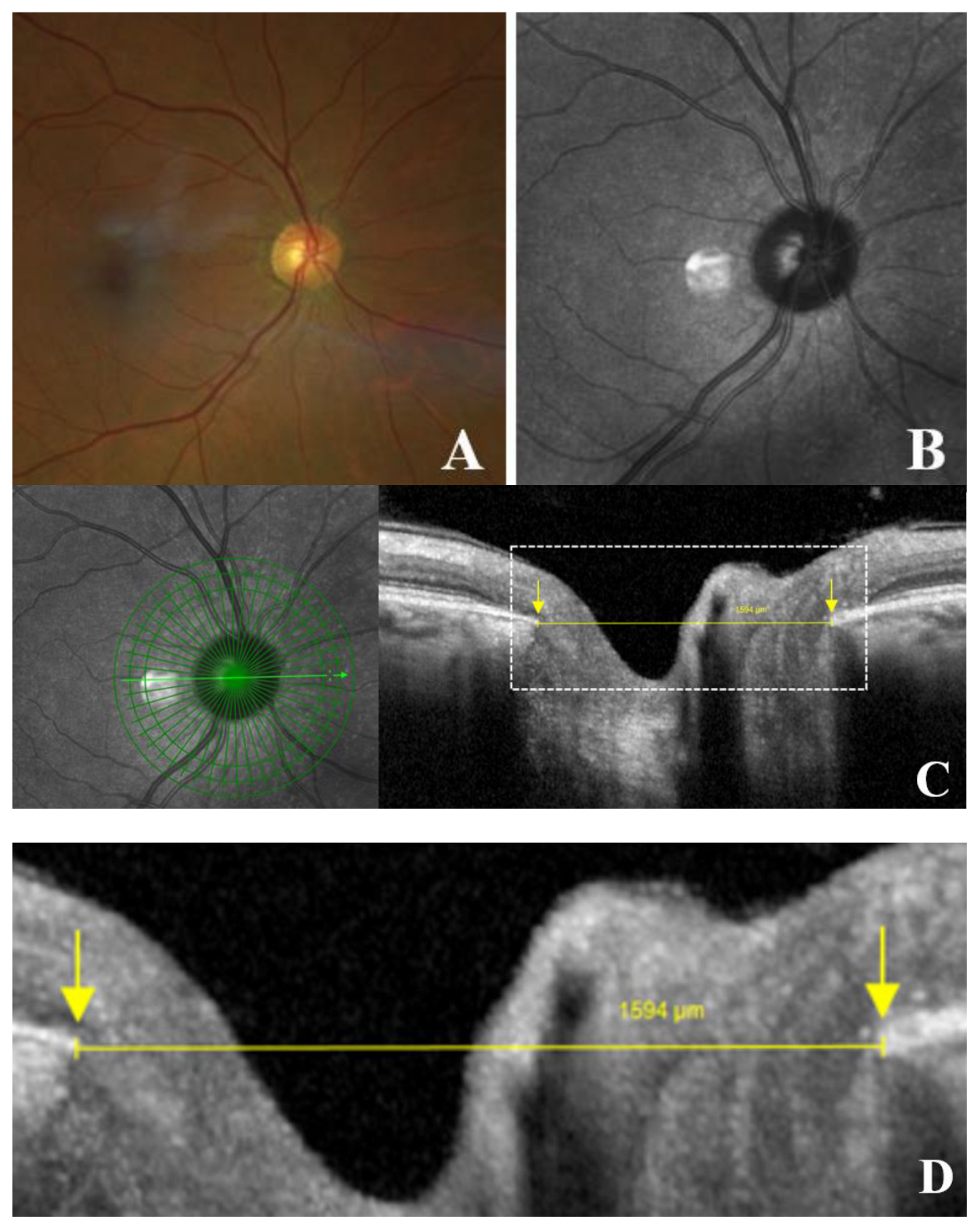

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of optic disc measurements in an eye without gamma peripapillary atrophy (γPPA). (A) Normal fundus image of right eye; (B) Infrared image without the radial line scan tool; (C) Section along the green arrow in the infrared image. Yellow arrow calipers indicating the measurement between temporal Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO) and nasal BMO (1594 μm). Arrows indicate BMO (yellow); (D) Magnified view of the area within the white dashed rectangle, showing the same structures to improve the readability of the measurements.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of optic disc measurements in an eye without gamma peripapillary atrophy (γPPA). (A) Normal fundus image of right eye; (B) Infrared image without the radial line scan tool; (C) Section along the green arrow in the infrared image. Yellow arrow calipers indicating the measurement between temporal Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO) and nasal BMO (1594 μm). Arrows indicate BMO (yellow); (D) Magnified view of the area within the white dashed rectangle, showing the same structures to improve the readability of the measurements.

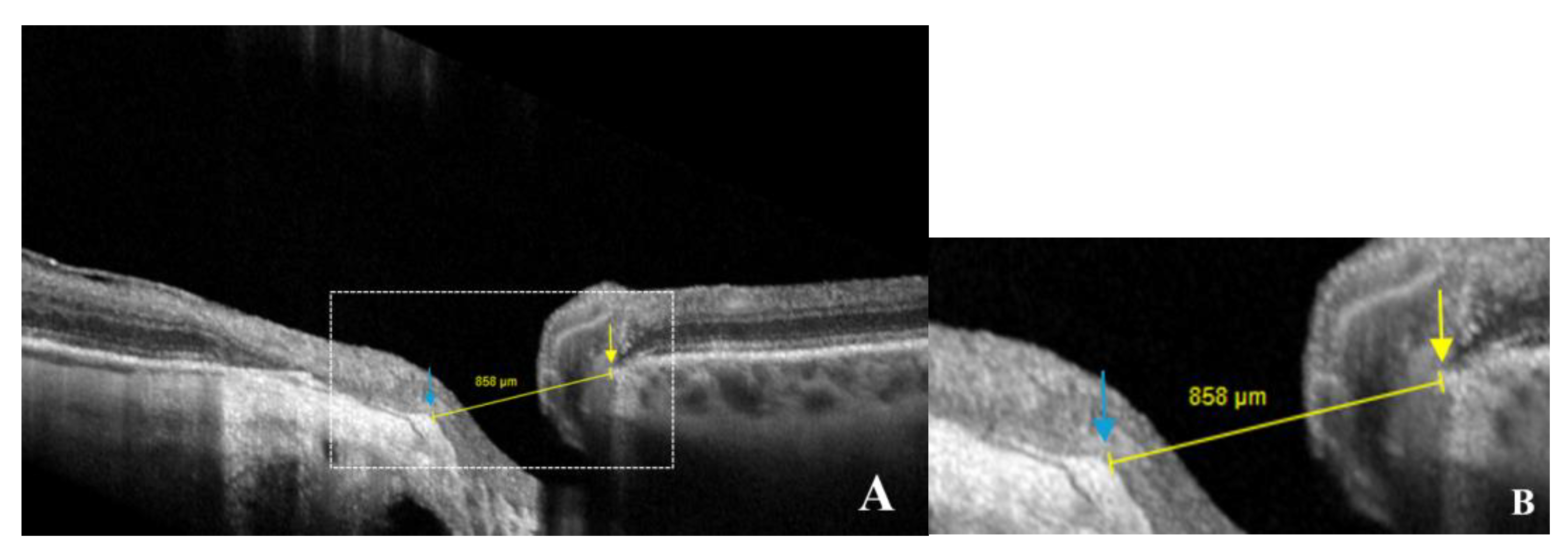

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of optic disc measurements in an eye with gamma peripapillary atrophy (γPPA). (

A) Yellow arrow calipers indicating the measurement between the anterior scleral opening (ASO) (temporal) and the nasal Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO) (858 μm). Arrows indicate ASO (blue) and BMO (yellow); (

B) Magnified view of the area within the white dashed rectangle, showing the same structures in greater detail to improve the readability of the measurements. (Same patient as in

Figure 2.).

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of optic disc measurements in an eye with gamma peripapillary atrophy (γPPA). (

A) Yellow arrow calipers indicating the measurement between the anterior scleral opening (ASO) (temporal) and the nasal Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO) (858 μm). Arrows indicate ASO (blue) and BMO (yellow); (

B) Magnified view of the area within the white dashed rectangle, showing the same structures in greater detail to improve the readability of the measurements. (Same patient as in

Figure 2.).

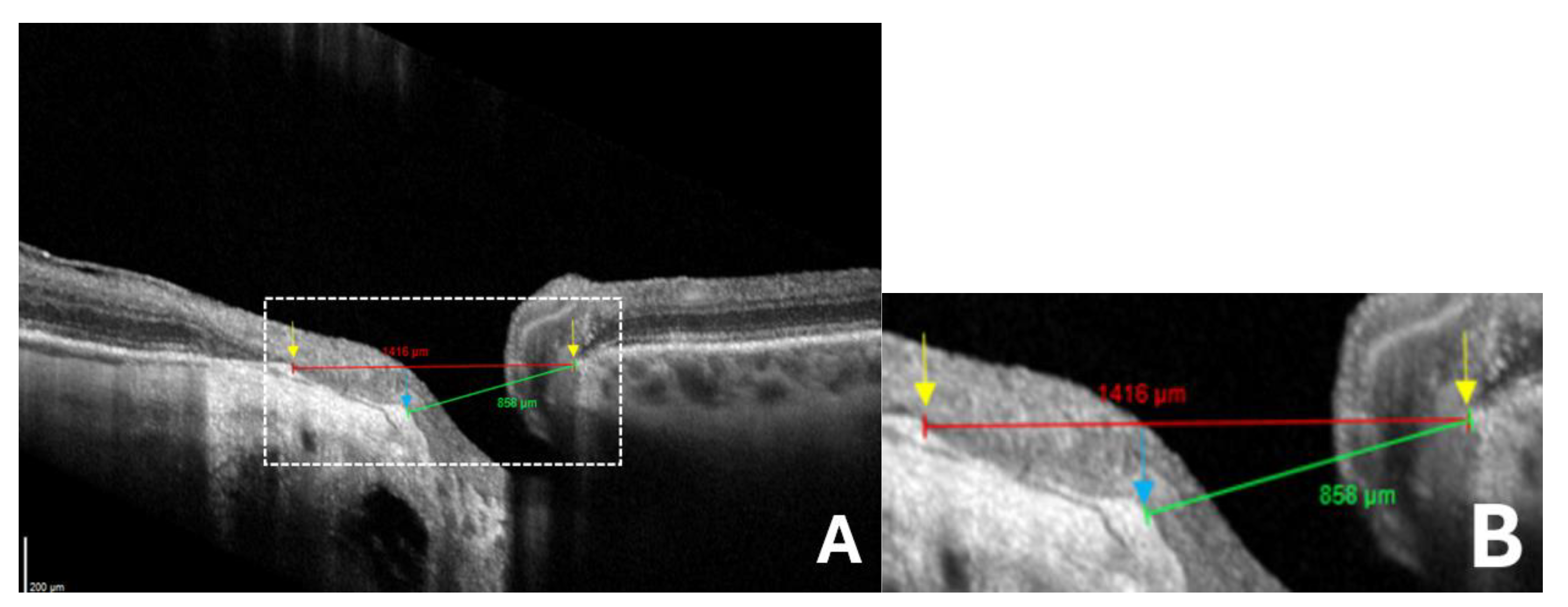

Figure 5.

Comparison between standard and anatomically adjusted optic disc measurements for ovality index calculation in eyes with gamma peripapillary atrophy (γPPA). (

A) Red arrow calipers indicating the standard measurement of the disc diameter between temporal Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO) and nasal BMO (1416 μm) which is overestimated due to the temporal shifting of the Bruch’s membrane. Green arrow calipers show the neural canal opening measurement between the temporal anterior scleral opening (ASO) and nasal BMO (858 μm), reflecting the landmarks that we considered for disc ovality index measurement. Arrows indicate ASO (blue) and BMO (yellow); (

B) Magnified view of the area within the white dashed rectangle, showing the same structures in greater detail to improve the readability of the measurements. (Same patient as in

Figure 2.).

Figure 5.

Comparison between standard and anatomically adjusted optic disc measurements for ovality index calculation in eyes with gamma peripapillary atrophy (γPPA). (

A) Red arrow calipers indicating the standard measurement of the disc diameter between temporal Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO) and nasal BMO (1416 μm) which is overestimated due to the temporal shifting of the Bruch’s membrane. Green arrow calipers show the neural canal opening measurement between the temporal anterior scleral opening (ASO) and nasal BMO (858 μm), reflecting the landmarks that we considered for disc ovality index measurement. Arrows indicate ASO (blue) and BMO (yellow); (

B) Magnified view of the area within the white dashed rectangle, showing the same structures in greater detail to improve the readability of the measurements. (Same patient as in

Figure 2.).

The width of γPPA, which is the peripapillary atrophy (PPA) without the Bruch’s membrane [

8,

9], was assessed using radial OCT. This atrophic zone extends from the BMO to the ASO (

Figure 2, A-D). The measurement of the γPPA width was performed along the minor axis, from the BMO indicated by the orange arrow to the ASO, indicated by the vertical green line (

Figure 2, C-D).

The degree of disc deformation was quantified using the OI, calculated as the ratio of the shortest (minor axis) to longest disc diameters (major axis) [

10] (

Figure 3, A-D). In the presence of internally oblique or non-oblique border tissue (the fibroastrocytic differentiation separating the optic nerve fibers from the neighboring sclera or choroid), the diameter was measured from the BMO to BMO [

19] (

Figure 3, C-D).

When the border tissue was externally oblique, resulting from temporal shifting of the BMO relative to the ASO, the diameter was measured from the ASO (temporal) to BMO (nasal) (

Figure 4, A-B).

A standard minor axis measurement between BMO (nasal) and BMO (temporal) would overestimate its length, leading to an artificially high OI (

Figure 5).

Analysis Procedure

OCT images from all eyes were analyzed by the investigator (Butt Sameer, BS), who performed the measurements. These measurements were subsequently reviewed and verified by the principal investigator, an experienced ophthalmologist (Ehongo Adèle, EA) to ensure accuracy.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were presented as mean, standard deviation (SD), and range for continuous variables, and as proportions and percentages for categorical variables. The IBM-SPSS V30.0 statistical software was used. A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Pearson correlation analyses and multivariable regression models were conducted. The three outcome variables, namely γPPA, OI, and AL, were analyzed separately as dependent variables. IPD was used as the main independent variable in all models, which were adjusted for age, gender, and myopia.

To account for the high number of zero values in γPPA width (eyes with no γPPA), a dummy variable (0 = absence, 1 = presence of γPPA) was created and served as an additional control variable in regression models involving γPPA width.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Overall, 100 eyes of 100 subjects were included, 60 of whom were females. The sample comprised 96 right eyes and 4 left eyes. A total of 83 eyes had reliable RE data. Among the 17 eyes without reliable RE, 7 were classified as myopic based on AL (≥ 26.0 mm), and 10 could not be classified due to missing or inconclusive data. Ultimately, 52 eyes were classified as myopic, 38 as non-myopic, and 10 remained unclassified. The mean age ± SD was 62.6 ± 13.7 years, range (20–83). The demographic and ocular features of the sample population are summarized in

Table 1.

Ten eyes had a history of phacoemulsification; since no remote pre-cataract refractive data were available for these eyes, they were excluded from the refractive analyses. Similarly, refractive data were excluded from five eyes with unoperated but clinically significant cataract, for which no prior refraction was available. Finally, two eyes with a history of refractive surgery were identified, and their refractive data were excluded, as no preoperative refraction was available.

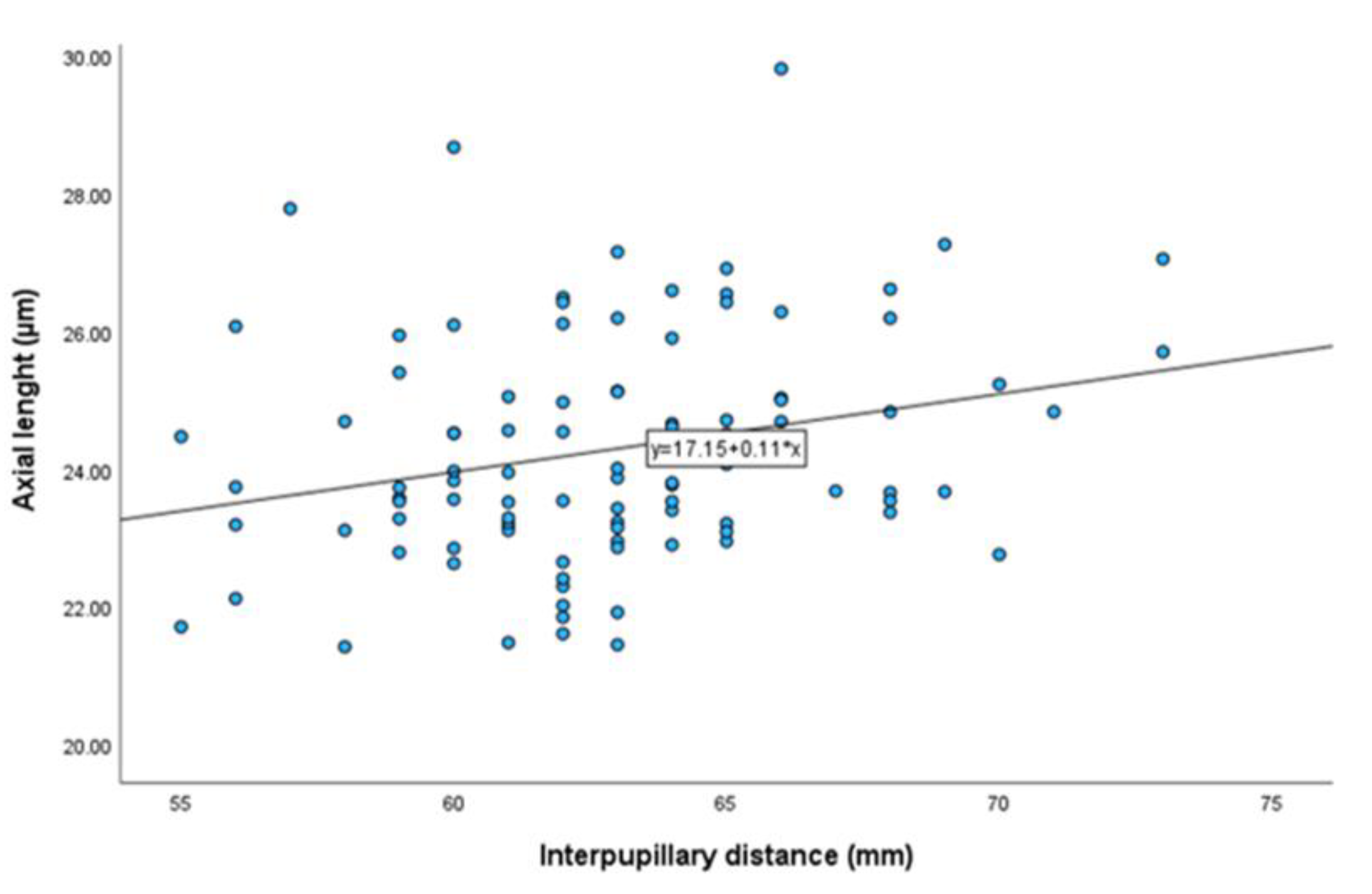

3.2. Correlation Analyses

Pearson correlation analyses revealed no significant association between IPD and OI (r = 0.001, p = 0.989), nor between IPD and γPPA width (r = -0.028, p = 0.789). There was a significant but weak positive correlation between IPD and AL (r = 0.256, p = 0.011) (

Table 2,

Figure 6). Additionally, a significant correlation was observed between γPPA width and OI. Both parameters also showed significant associations with AL (

Table 2).

3.3. Multivariable Regression Analyses

Multivariable linear regression models were performed, including age, gender, and myopia as control variables. In models involving γPPA width, the dummy variable was included as an additional control. No significant association was found between IPD and γPPA width after adjustment (β = -3.814; 95% CI: -13.67 to 6.04; p = 0.44). Similarly, no significant association was observed between IPD and OI (β = -0.001; 95% CI: -0.006 to 0.005; p = 0.85). A marginal trend toward significance was noted between IPD and AL (β = 0.078; 95% CI: -0.003 to 0.160; p = 0.059).

3.4. Sensitivity Analyses

Complementary analyses were conducted, including a logarithmic transformation of γPPA and Spearman correlation testing. Since the transformation did not meaningfully alter the results, it was not retained. Similarly, as the Spearman results were comparable to those of Pearson, only Pearson correlations were used in the main analyses. These additional analyses are detailed in Annex 1.

4. Discussion

Structural changes of ONH and peripapillary region in myopic eyes have become a major focus of current research, given their clinical relevance, particularly their potential to mimic or overlap with glaucomatous visual field defects, including those seen in normal-tension glaucoma [

13,

15]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship between IPD and structural changes of the ONH, namely the OI and γPPA width. Our findings showed no significant association, suggesting that IPD-related adduction forces may not play a major role in shaping ONH morphology in myopic eyes.

In contrast, we observed significant correlations between AL and both OI and γPPA width. These findings support the established role of axial elongation as a major driver of myopic structural changes [

4,

20,

21]. Moreover, the strong correlation between OI and γPPA suggests that papillary and peripapillary changes are closely related, likely due to a shared underlying mechanism. Previous studies have shown that these deformations develop simultaneously during ocular elongation [

4,

20]. It is important to emphasize that myopic complications result from several structural deformations that develop simultaneously as the eye elongates. Changes such as optic disc obliquity and γPPA often occur together and may interact with other anatomical alterations. This cumulative remodeling process likely underlies more complex forms of myopic damage, including peripapillary intrachoroidal cavitation [

16,

22].

Structurally, myopic eyes have a longer AL. This increased AL compromises the sclera’s structure and reduces its rigidity, making it more susceptible to deformation [

23]. In eyes with marked AL, traction on the optic disc may result from a short ONS or reduced sheath elasticity, both of which could restrict full ocular adduction [

24].

Although a weak correlation was observed between IPD and AL (r = 0.256, p = 0.011), potentially reflecting shared developmental pathways influencing craniofacial and ocular growth [

25], this relationship did not translate to structural ONH changes after adjusting for confounding factors. After adjusting for AL, age, and gender, the associations between IPD and OI (β = -0.001, p = 0.85), as well as between IPD and γPPA (β = -3.814, p = 0.44), remained statistically non-significant. These results suggest that axial elongation exerts a predominant influence, potentially overshadowing any biomechanical effects associated with IPD.

The advanced mean age of our cohort (62.6 ± 13.7 years) was considered a potential confounder in the analysis of γ-zone peripapillary atrophy, as age and lifetime myopic exposure are positively correlated due to the progressive nature of axial elongation over time [

26]. In our study, adjustments were made for the following parameters: age, gender, and myopia to account for potential confounding factors. Age was included because peripapillary changes naturally worsen with aging, independent of myopia [

27]. Gender was controlled for, as women generally exhibit smaller IPD compared to men, and this anatomical difference could indirectly influence outcomes [

28]. Myopia was adjusted for because its severity (assessed via axial elongation) is a major driver of ONH deformations [

29].

Retinal image magnification varies with ocular biometry, so lateral (retina-parallel) measurements obtained on OCT are inherently affected [

30,

31]. The Spectralis® OCT platform mitigates this automatically: its HEYEX software (v 6.16.2), built on the Gullstrand schematic eye, applies an individualized lateral scaling factor based on each eye’s biometry [

32,

33]. Even so, some investigators propose adding an extra correction for AL, while others contend that entering a patient’s mean keratometry during scan acquisition offers a more accurate adjustment than the default setting [

33]. Conversely, very recent work by Kirik et al. indicates that, with Spectralis® OCT, further AL compensation is unnecessary [

34]. Therefore, we did not perform any corrections.

Limitations

First, this was a cross-sectional and pilot study. This design limitation warrants future confirmatory and longitudinal investigations.

Second, differences in nasal bridge anatomy may influence the extent of the visual field. Specifically, flatter nasal bridges have been shown to allow greater visibility in the nasal field during extreme gaze due to reduced occlusion [

35]. This anatomical variation could partly explain population-level differences in ONH changes associated with myopia. In our study, nasal bridge structure was not assessed. Yet, for comparable IPD, differences in nasal anatomy, such as flatter bridges, may permit greater adduction, potentially contributing to the observed disparities in myopic ONH changes across populations. Including direct measurements of nasal morphology or stratifying analyses by ethnicity would have strengthened the interpretation of our findings.

Third, it is plausible that in individuals with larger IPD, maintaining binocular vision requires greater ocular movement amplitudes, which could theoretically impact the binocular visual field. However, this adaptation largely depends on each individual’s vergence capacity. Dag et al. have suggested that individuals with larger IPD may exhibit reduced vergence amplitudes, potentially indicating a less stable binocular fusion [

17]. While findings remain inconclusive, this raises the possibility that structural variations such as IPD might influence binocular visual performance. Since we did not assess binocular visual fields in this study, we cannot determine whether differences in IPD, γPPA width, or OI translate into functional differences in binocular vision. Future studies should include binocular visual field testing to explore these potential associations.

Fourth, measurements were performed by one investigator and reviewed by a senior ophthalmologist. This point should be addressed through independent double grading in future studies.

Fifth, the study cohort was ethnically homogeneous, consisting almost exclusively of individuals of Caucasian descent, with negligible representation from other populations. This lack of diversity may limit the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic populations, where myopic ONH changes are not only more prevalent but also tend to be more severe [

36]. This limitation was not accounted for in the study design and should be addressed in future research through more inclusive sampling or stratified analyses.

Sixth, as this was a pilot study, we arbitrarily enrolled 100 eyes, 52 of which were myopic. A larger sample might have yielded significant correlations. Therefore, future studies should include more myopic eyes.

Seventh, participants were recruited from a tertiary clinic, thus involving a relatively homogeneous group that is unlikely to represent the general population.

5. Conclusions

This study is the first to explore the relationship between IPD and structural changes of the ONH in myopia, specifically the OI and γPPA. Despite previous findings suggesting that IPD may influence vergence amplitude and that duction movements could promote optic nerve deformations, no association was observed between IPD and either OI or γPPA width after adjusting for confounding variables. These findings reinforce the predominant role of axial elongation in driving myopic ONH remodeling, outweighing any potential biomechanical influence of IPD. Future studies should consider longitudinal designs, a broader ethnic representation, and assess binocular visual field extent, to further elucidate the complex interplay between ocular structure, craniofacial features, and visual biomechanics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E. and S.B.; methodology, A.E. and S.B.; software, NA.; validation, NA.; formal analysis, A.E. and S.B.; investigation, A.E. and S.B.; resources, NA.; data curation, A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, A.E. and S.B.; visualization, NA.; supervision, NA.; project administration, NA.; funding acquisition, NA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (reference SRB2024239) and Ethics Committee (reference P2024/450, approved on 12 November 2024.) of HUB, Erasme Hospital, Brussels.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgments to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AL |

Axial Length |

| ASO |

Anterior Scleral Opening |

| BMO |

Bruch’s Membrane Opening |

| PPA |

Peripapillary Atrophy |

| γPPA |

Gamma Peripapillary Atrophy |

| IPD |

Interpupillary Distance |

| OCT |

Optical Coherence Tomography |

| OI |

Ovality Index |

| ONH |

Optic Nerve Head |

| ONS |

Optic Nerve Sheaths |

| RE |

Refractive Error |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SE |

Spherical Equivalent |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Sensitivity Analyses (Details)

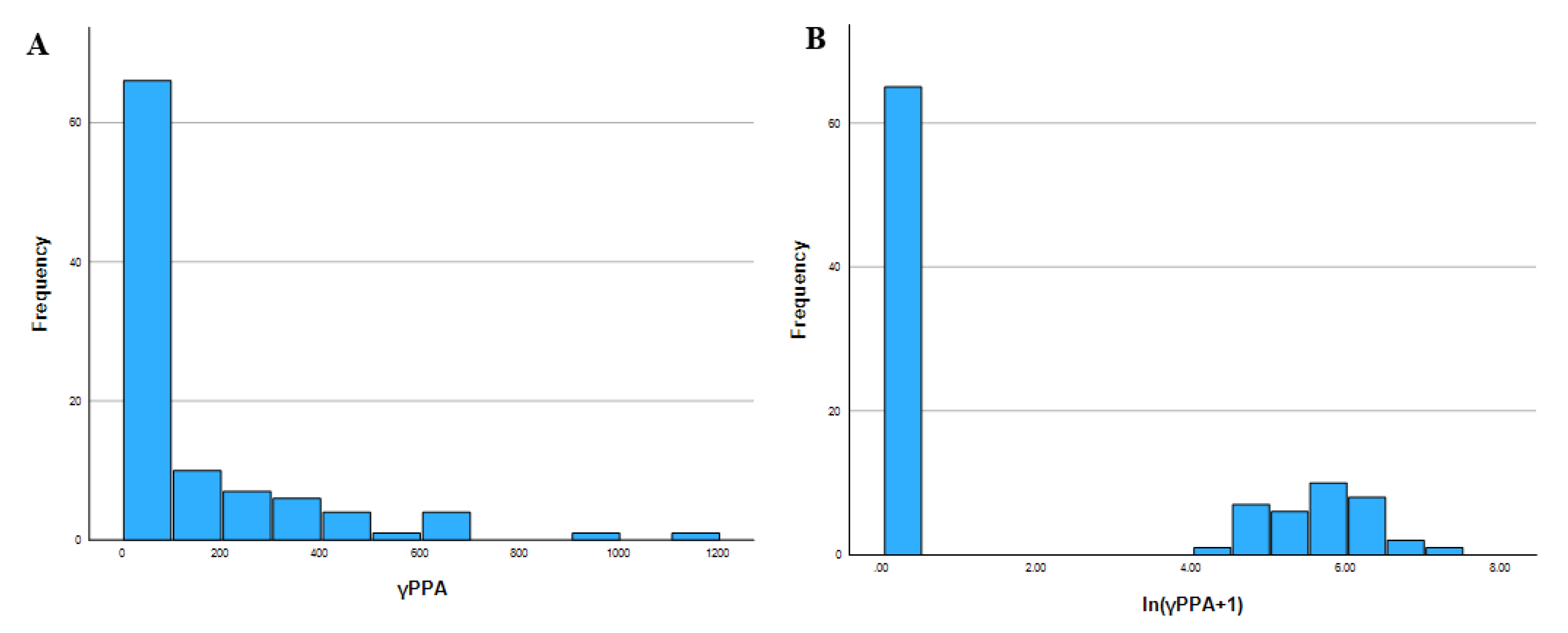

Given the right-skewed distribution of γPPA width and the substantial number of zero values, a logarithmic transformation ln (γPPA + 1) was explored in an attempt to improve the normality of the data (

Figure A1). However, due to the concentration of zero values, a binary variable (γPPA_dummy) was created to distinguish between absence and presence of γPPA.

Figure A1.

Distribution of gamma peripapillary atrophy (γPPA) before and after logarithmic transformation. (a) Histogram A: Original distribution of γPPA showing strong right skew and a high frequency of zero values; (b) Histogram B: The log-transformed variable ln (γPPA + 1) shows improved normality.

Figure A1.

Distribution of gamma peripapillary atrophy (γPPA) before and after logarithmic transformation. (a) Histogram A: Original distribution of γPPA showing strong right skew and a high frequency of zero values; (b) Histogram B: The log-transformed variable ln (γPPA + 1) shows improved normality.

However, this transformation did not meaningfully alter the overall results (

Table A1). Therefore, analyses were ultimately conducted using the original (untransformed) γPPA width values.

Table A1.

Adjusted multivariable regression models assessing the association between IPD and γPPA, in both original and log-transformed forms.

Table A1.

Adjusted multivariable regression models assessing the association between IPD and γPPA, in both original and log-transformed forms.

| Dependent variable |

Predictors included |

β (95% CI) for IPD |

p-value |

| γPPA |

IPD, age, gender, myopia, γPPA_dummy |

-3.814 (-13.67; 6.05) |

.444 |

| ln (γPPA+ 1) |

IPD, age, gender, myopia, γPPA_dummy |

-.016 (-0.041; 0.010) |

.231 |

In addition, due to the non-optimal normality of certain continuous variables, non-parametric Spearman correlation analyses were also performed alongside Pearson correlations (

Table A2). Since the results were comparable across both methods, only Pearson correlation coefficients were reported in the main text.

Table A2.

Pearson vs. Spearman correlation coefficients.

Table A2.

Pearson vs. Spearman correlation coefficients.

| Variable pair |

r (Pearson) |

p-value (Pearson) |

ρ (Spearman) |

p-value (Spearman) |

| IPD – γPPA |

-.028 |

.782 |

.028 |

.785 |

| IPD – OI |

.001 |

.989 |

-.006 |

.949 |

| IPD – AL |

.256* |

.011 |

.274** |

.006 |

| γPPA – OI |

-.694** |

<.001 |

-.403** |

<.001 |

| γPPA – AL |

.547** |

<.001 |

.554** |

<.001 |

| AL – OI |

-.417** |

<.001 |

-.275** |

.007 |

These additional exploratory analyses were conducted to ensure the robustness and reliability of the main statistical results presented.

References

- Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, Jong M, Naidoo KS, Sankaridurg P, Wong TY, Naduvilath TJ, Resnikoff S. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016 May;123(5):1036-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaridurg P, Tahhan N, Kandel H, Naduvilath T, Zou H, Frick KD, Marmamula S, Friedman DS, Lamoureux E, Keeffe J, Walline JJ, Fricke TR, Kovai V, Resnikoff S. IMI Impact of Myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021 Apr 28;62(5):2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Li Y, Musch DC, Wei N, Qi X, Ding G, Li X, Li J, Song L, Zhang Y, Ning Y, Zeng X, Hua N, Li S, Qian X. Progression of Myopia in School-Aged Children After COVID-19 Home Confinement. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021 Mar 1;139(3):293-300. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim TW, Kim M, Weinreb RN, Woo SJ, Park KH, Hwang JM. Optic disc change with incipient myopia of childhood. Ophthalmology. 2012 Jan;119(1):21-6.e1-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai Y, Jonas JB, Ling Z, Sun X. Ophthalmoscopic-Perspectively Distorted Optic Disc Diameters and Real Disc Diameters. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015 Nov;56(12):7076-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim M, Kim TW, Weinreb RN, Lee EJ. Differentiation of parapapillary atrophy using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2013 Sep;120(9):1790-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehongo, A. Optical coherence tomography analysis of peripapillary intrachoroidal cavitation. PhD thesis, Université libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, 2024.

- Dai Y, Jonas JB, Huang H, Wang M, Sun X. Microstructure of parapapillary atrophy: beta zone and gamma zone. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 Mar 19;54(3):2013-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas JB, Jonas SB, Jonas RA, Holbach L, Dai Y, Sun X, Panda-Jonas S. Parapapillary atrophy: histological gamma zone and delta zone. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47237. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay E, Seah SK, Chan SP, Lim AT, Chew SJ, Foster PJ, Aung T. Optic disk ovality as an index of tilt and its relationship to myopia and perimetry. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005 Feb;139(2):247-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Chang S, Grinband J, Yannuzzi LA, Freund KB, Hoang QV, Girard MJ. Optic nerve tortuosity and displacements during horizontal eye movements in healthy and highly myopic subjects. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022 Nov;106(11):1596-1602. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Fisher LK, Milea D, Jonas JB, Girard MJ. Predictions of Optic Nerve Traction Forces and Peripapillary Tissue Stresses Following Horizontal Eye Movements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017 Apr 1;58(4):2044-2053. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehongo A, Bacq N, Kisma N, Dugauquier A, Alaoui Mhammedi Y, Coppens K, Bremer F, Leroy K. Analysis of Peripapillary Intrachoroidal Cavitation and Myopic Peripapillary Distortions in Polar Regions by Optical Coherence Tomography. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022 Aug 13;16:2617-2629. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang MY, Shin A, Park J, Nagiel A, Lalane RA, Schwartz SD, Demer JL. Deformation of Optic Nerve Head and Peripapillary Tissues by Horizontal Duction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017 Feb;174:85-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehongo A, Dugauquier A, Kisma N, De Maertelaer V, Nana Wandji B, Tchatchou Tomy W, Alaoui Mhammedi Y, Coppens K, Leroy K, Bremer F. Myopic (Peri)papillary Changes and Visual Field Defects. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023 Nov 1;17:3295-3306. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehongo A, Bacq N. Peripapillary Intrachoroidal Cavitation. J Clin Med. 2023 Jul 16;12(14):4712. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dag M, Demirkilinc Biler E, Ceper SB, Uretmen O. Association between interpupillary distance and fusional convergence-divergence amplitudes. EUROPEAN EYE RESEARCH. 2022;2(3):103–6. [CrossRef]

- Flitcroft DI, He M, Jonas JB, Jong M, Naidoo K, Ohno-Matsui K, Rahi J, Resnikoff S, Vitale S, Yannuzzi L. IMI - Defining and Classifying Myopia: A Proposed Set of Standards for Clinical and Epidemiologic Studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019 Feb 28;60(3):M20-M30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada Y, Araie M, Shibata H, Ishikawa M, Iwata T, Yoshitomi T. Optic Disc Margin Anatomic Features in Myopic Eyes with Glaucoma with Spectral-Domain OCT. Ophthalmology. 2018 Dec;125(12):1886-1897. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim M, Choung HK, Lee KM, Oh S, Kim SH. Longitudinal Changes of Optic Nerve Head and Peripapillary Structure during Childhood Myopia Progression on OCT: Boramae Myopia Cohort Study Report 1. Ophthalmology. 2018 Aug;125(8):1215-1223. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim YC, Moon JS, Park HL, Park CK. Three Dimensional Evaluation of Posterior Pole and Optic Nerve Head in Tilted Disc. Sci Rep. 2018 Jan 18;8(1):1121. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehongo A, Hasnaoui Z, Kisma N, Alaoui Mhammedi Y, Dugauquier A, Coppens K, Wellens E, de Maertelaere V, Bremer F, Leroy K. Peripapillary intrachoroidal cavitation at the crossroads of peripapillary myopic changes. Int J Ophthalmol. 2023 Dec 18;16(12):2063-2070. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee WJ, Kim YJ, Kim JH, Hwang S, Shin SH, Lim HW. Changes in the optic nerve head induced by horizontal eye movements. PLoS One. 2018 Sep 18;13(9):e0204069. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demer, JL. Optic Nerve Sheath as a Novel Mechanical Load on the Globe in Ocular Duction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016 Apr;57(4):1826-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams AL, Bohnsack BL. Neural crest derivatives in ocular development: discerning the eye of the storm. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2015 Jun;105(2):87-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee MW, Lee SE, Lim HB, Kim JY. Longitudinal changes in axial length in high myopia: a 4-year prospective study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020 May;104(5):600-603. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang XJ, Chau DKS, Wang YM, Cheung CSH, Chan HN, Shi J, Nip KM, Tang S, Chan RCF, Lau A, Kei SH, Kam KW, Young AL, Chen LJ, Tham CC, Ohno-Matsui K, Pang CP, Yam JC. Prevalence and Characteristics of Peripapillary Gamma Zone in Children With Different Refractive Status: The Hong Kong Children Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023 Apr 3;64(4):4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gantz L, Shneor E, Doron R. Agreement and inter-session repeatability of manual and automatic interpupillary distance measurements. J Optom. 2021 Oct-Dec;14(4):299-314. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng D, Ruan K, Wu M, Qiao Y, Gao W, Lian H, Shen M, Bao F, Yang Y, Zhu J, Huang H, Meng X, Shen L, Ye Y. Characteristics of the Optic Nerve Head in Myopic Eyes Using Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2022 Jun 1;63(6):20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett AG, Rudnicka AR, Edgar DF. Improvements on Littmann’s method of determining the size of retinal features by fundus photography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994 Jun;232(6):361-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudnicka AR, Burk RO, Edgar DF, Fitzke FW. Magnification characteristics of fundus imaging systems. Ophthalmology. 1998 Dec;105(12):2186-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delori F, Greenberg JP, Woods RL, Fischer J, Duncker T, Sparrow J, Smith RT. Quantitative measurements of autofluorescence with the scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 Dec 9;52(13):9379-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ctori I, Gruppetta S, Huntjens B. The effects of ocular magnification on Spectralis spectral domain optical coherence tomography scan length. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015 May;253(5):733-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirik F, Ersoz MG, Atalay F, Ozdemir H. Should we perform ocular magnification for lateral measurements in Heidelberg spectralis optical coherence tomography? Eur J Ophthalmol. 2024 Jan;34(1):NP152-NP153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapp AP, Ono H. The rhino-optical phenomenon: ocular parallax and the visible field beyond the nose. Vision Res. 1986;26(7):1163-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu R, Wu Q, Yi Z, Chen C. Multimodal imaging of optic nerve head abnormalities in high myopia. Front Neurol. 2024 Apr 23;15:1366593. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).