1. Introduction

Knowledge of the interaction between the lithospheric plates is essential for understanding the geodynamic processes that shape the Earth's surface, for geohazard assessment, and has significant importance with implications for safety, natural resources and fundamental research.

Seismic tomography is an imaging technique that uses seismic waves generated by earthquakes or explosions to analyze the Earth's internal structure. It provides information about seismic wave velocity variations. Thus, areas with low velocities indicate warm, weakly consolidated or fluid-rich regions, such as magmatic chambers or active faults, and areas with high velocities reflect cold, rigid regions, such as stable lithospheric blocks or dense rocks. Although seismic tomography is still an imperfect tool (and as proof, different authors often provide inconsistent images for the same areas and even for the same datasets), it contributes significantly to our understanding of plate interactions and tectonic processes.

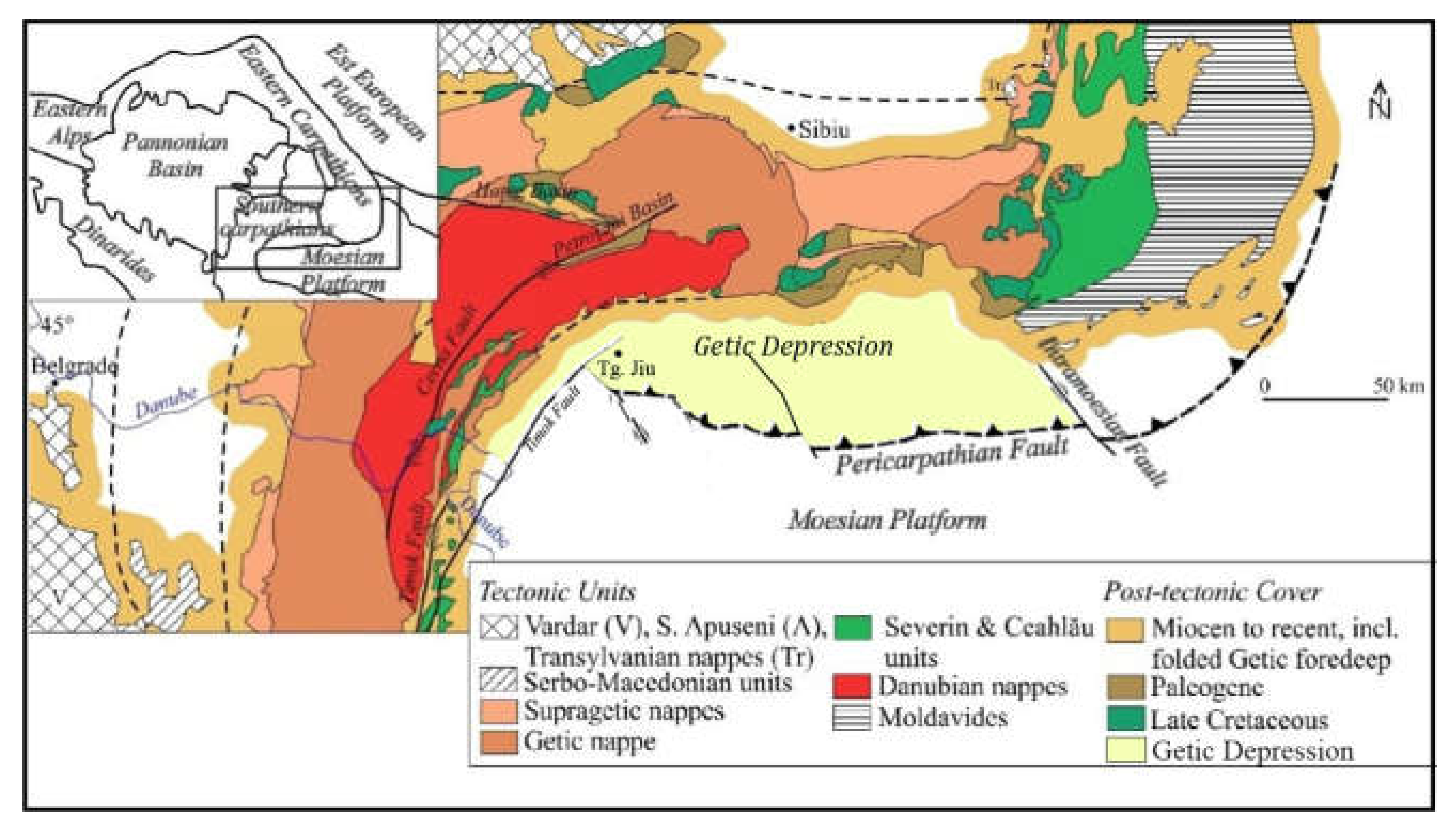

The Târgu Jiu region, located in the southwestern part of Romania, close to the contact of Getic Depression with the South Carpathians, has been considered until 2023 as an area of low seismic activity, not included in the seismogenic zones of Romania. Seismic activity in the Getic Depression (

Figure 1) is generally manifested by earthquakes of moderate size, rarely exceeding magnitude 5 [

1]. The most significant earthquakes before 2023 were recorded on June 20, 1943 (Mw=5.2) produced east of Tismana, on July 9, 1912 (Mw=4.5) occurred, about 9 km south of Târgu Jiu and on May 4, 1963 (Mw=4.5), at about 22 km NW of the same location. However, since February 2023, the area has experienced a significant intensification of the seismic activity, highlighting more complex seismotectonic processes than initially thought. The earthquake sequence that started in February 2023 outlines a notable potential to generate significant earthquakes and draws the attention to the scientific community to the complex tectonic mechanisms that are still active at present in this area. Recent events underline the need for in-depth research to better understand the tectonic dynamics and to adequately prepare for seismic hazards. Note also that the Getic Depression is a geological unit characterized by the presence of sedimentary formations favorable for the accumulation of hydrocarbons, and the first exploration and drilling activities for hydrocarbon extraction in this area started in the 1960s. Considering these particularities, the need to know in detail the geological structure in correlation with the geodynamics of the area becomes increasingly a demanding issue with implications on seismic hazard assessment.

2. Seismotectonic Context

The South Carpathians is one of the most twisted segments of the Alpine orogen where the orientation of the orogen range suddenly shifts from east-west to north-south and then turns back to east-west towards the Balkans. The present-day configuration of the South Carpathians system is the result of a long evolution that includes multiple tectonic processes like: plate convergence and collision, lithospheric stretching and break-up, orogen-parallel extension, rotation and wrenching and basin opening and inversion [

6,

7].

The Getic foreland basin (

Figure 1) is located along the northern edge of the Moesian Plate, within the Getic Depression, and is composed of Neogene sediments that reach thicknesses of up to 3,000 meters [

8]. The Getic Depression is well-known as a hilly region connecting the Moesian Platform with the South Carpathians. It extends between the Dâmbovița River in the east and the Danube Valley in the west, with its southern boundary marked by the Pericarpathian Fault. The Getic Depression was formed as a result of large-scale transcurrent movements generated by the Paleogene to Early Miocene displacement and clockwise rotation of the Tisza-Dacia Unit around the western Moesia corner, followed by the Badenian-Sarmatian uplift of the South Carpathian units [

9,

10]. The Getic Depression initially formed in the Late Paleogene-Early Miocene as a pull-apart basin, with its development controlled by the Timok-Cerna Jiu fault system [

11]. Later, during the Sarmatian tectonic event, the pre-existing E-W fault system was inverted by oblique compression generated by the eastward movement of the Tisza-Dacia tectonic block [

12].

The tectonic molding around the Moesian platform of the South Carpathians observed west of Târgu Jiu began in the Oligocene and was mostly shaped by dextral wrenching along the Cerna Fault [

13]. The dextral wrenching continued into the Early Miocene, but more externally along the Timok Fault, with a dextral displacement of 65 km. In the Middle Miocene, dextral faults cut in the E-W and NW-SE direction the sedimentary cover of the Getic Depression [

7,

14]. Beneath the sedimentary cover of the Getic depression and in the area lined up in the extension of the Timok Fault, a perpendicular normal fault system is found along the western edge of the Moesian Platform. The N-S fault system originates from the Permo-Triassic rift and a younger E-W normal fault system mostly formed during the Mid-Tertiary period [

7].

3. Data & Methodology of Inversion

3.1. Data Description

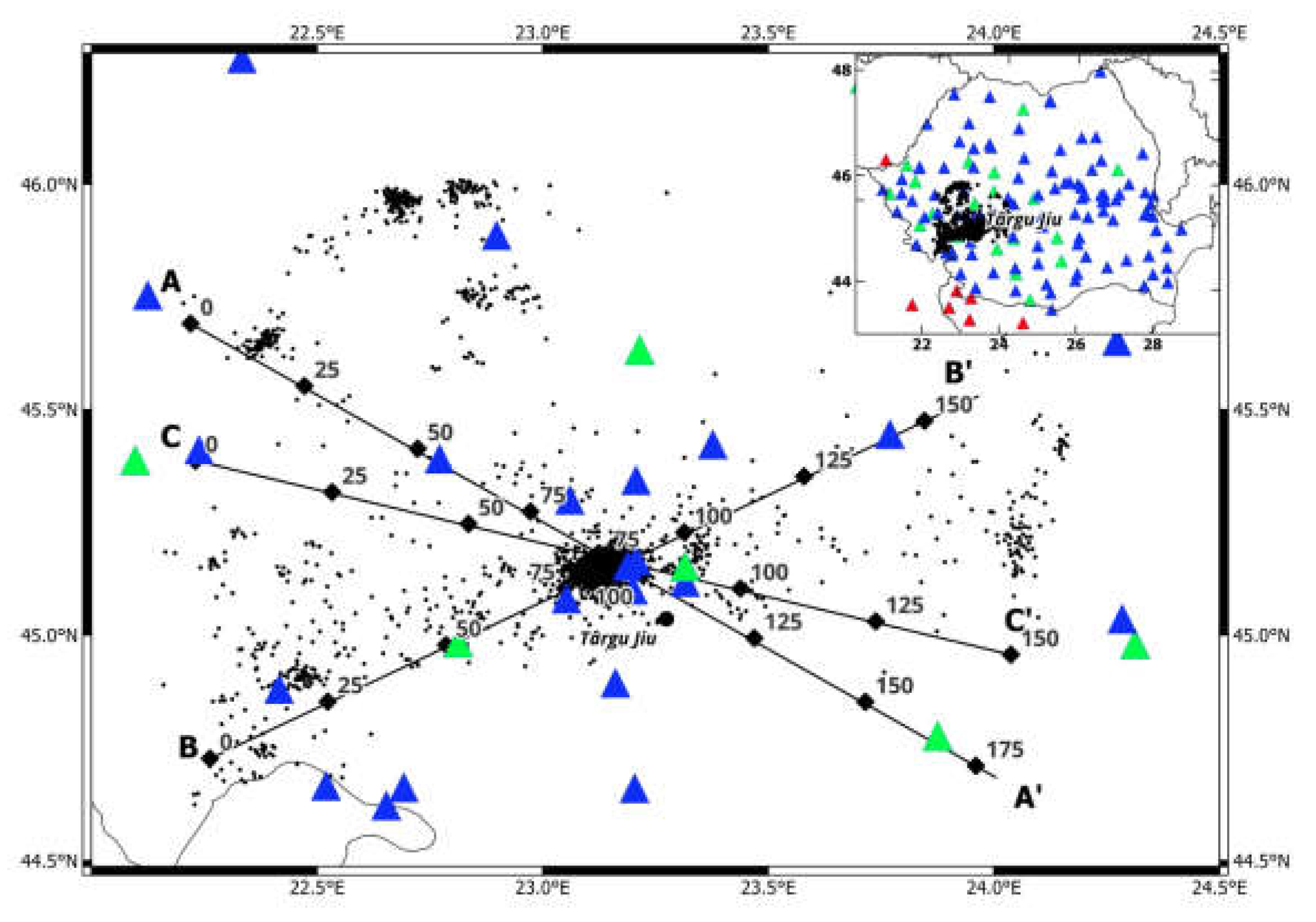

The Târgu Jiu earthquake sequences have their epicenters located in a distinctive area at the interface between the South Carpathian curvature and the Getic Depression (South Carpathian Foredeep). The seismic sequence of 2023 began on February 13th with a significant double shock of magnitudes 4.8 and 5.4 (Mw), followed by over 4,000 aftershocks, with magnitudes ranging from 1.1 to 4.6 [

16,

17,

18]. Considering that the layout of the seismic network during the seismic sequence was not the most suitable for a seismic tomography study, the dataset was extended with more than 1000 seismic events that occurred in the regions surrounding the studied area recorded since 2016. The dataset used in the study consists of 5323 earthquakes (see

Figure 2) that occurred in the Targu Jiu region and its surroundings from 2016 until December 2023. More than 3900 earthquakes are derived from the seismic sequence that started on February 13, 2023, in the northwest part of Targu Jiu.

The initial locations were performed using the Antelope software [

19], which is operated by the National Institute for Earth Physics (NIEP) for routine earthquake locations. A total number of 108016 picks with 51598 P - data and 56418 S - data from 133 seismic stations (

Figure 2) were processed. Most of the seismic stations are part of the National Seismic Network (NSN) [

20] operated by the NIEP and designed to monitor and analyze the seismicity of Romania. The NSN's capabilities are further strengthened by collaboration protocols with neighbouring countries, allowing NIEP to acquire and archive seismic data from additional seismic stations located outside Romania. This cross-border integration enhances the network’s ability to detect and analyze borders or regional seismic events. Some stations belong to the Adria Array project [

21] which aimed to investigate the entire Adriatic plate in south-eastern Europe by covering the area with a dense temporary seismic network.

All these events have been reviewed and included in the ROMPLUS earthquake catalog [

22], respecting localization quality criteria such as GAP < 120 or RMS < 1s. For the tomographic inversion, we applied additional criteria to select the input data set: at least 6 picks per event and the absolute values of residuals after source location in the 1-D model should not exceed 0.7 s. The final data set consists of 105976 arrival times from 5281 events with 50533 P - wave and 55443 S - wave arrival times.

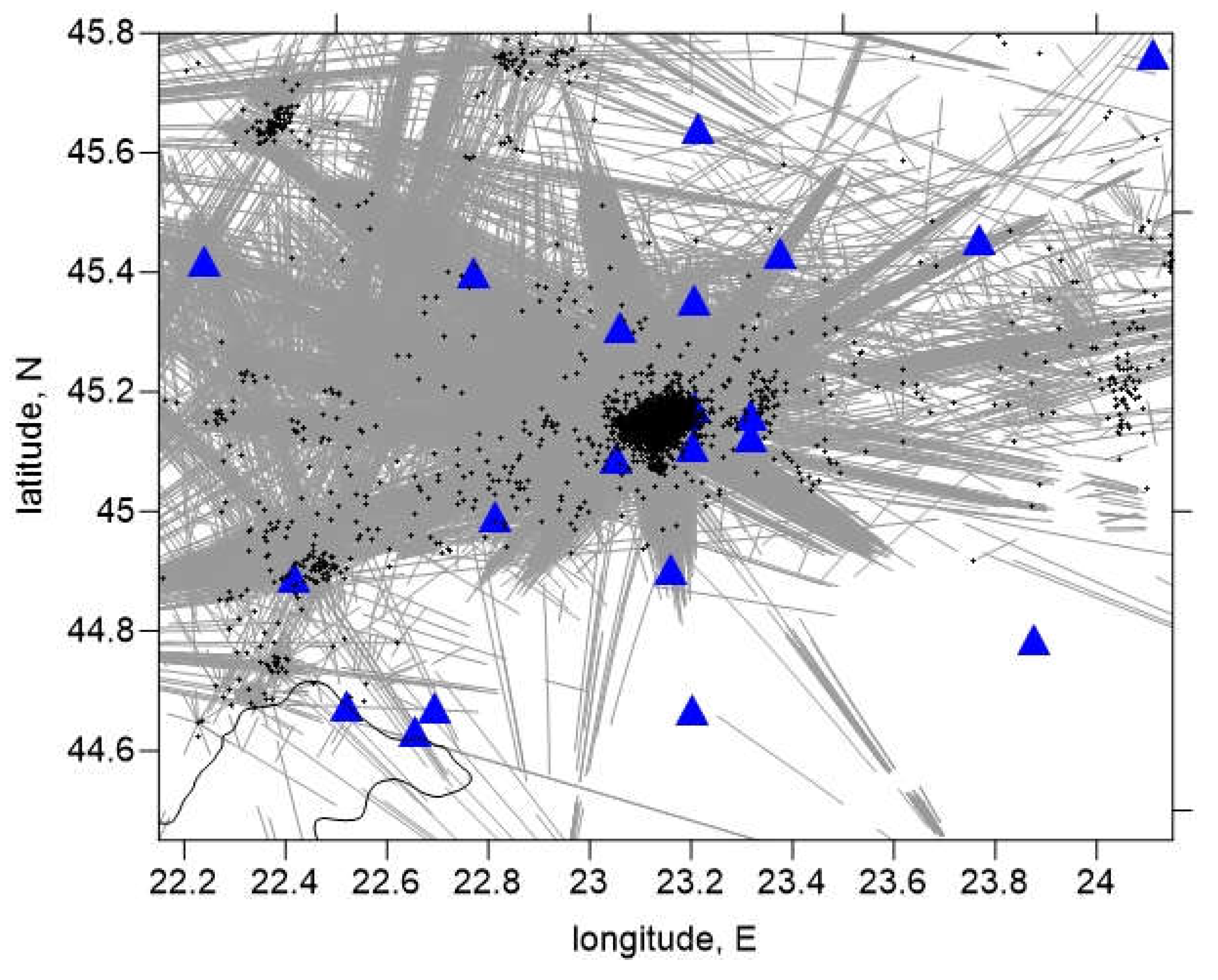

Figure 3 plots the ray coverage of the dataset.

3.2. Tomographic Inversion

The tomographic inversion was performed using the LOTOS code for body wave tomography and passive sources [

2]. This code has also been applied in several studies on seismic areas in Romania [

3,

4,

5] as well as on regions worldwide where, among seismicity, volcanoes have been studied [

23,

24,

25,

26].

The calculation procedure begins with the absolute location of the sources within the reference 1D velocity model, using a grid search method to determine the optimal coordinates of the events. At this stage, travel times are calculated in a simplified manner along straight lines using the 1D velocity distributions. In the next stage, the sources are relocated using a more precise algorithm based on the 3D ray-bending method initially proposed by [

27].

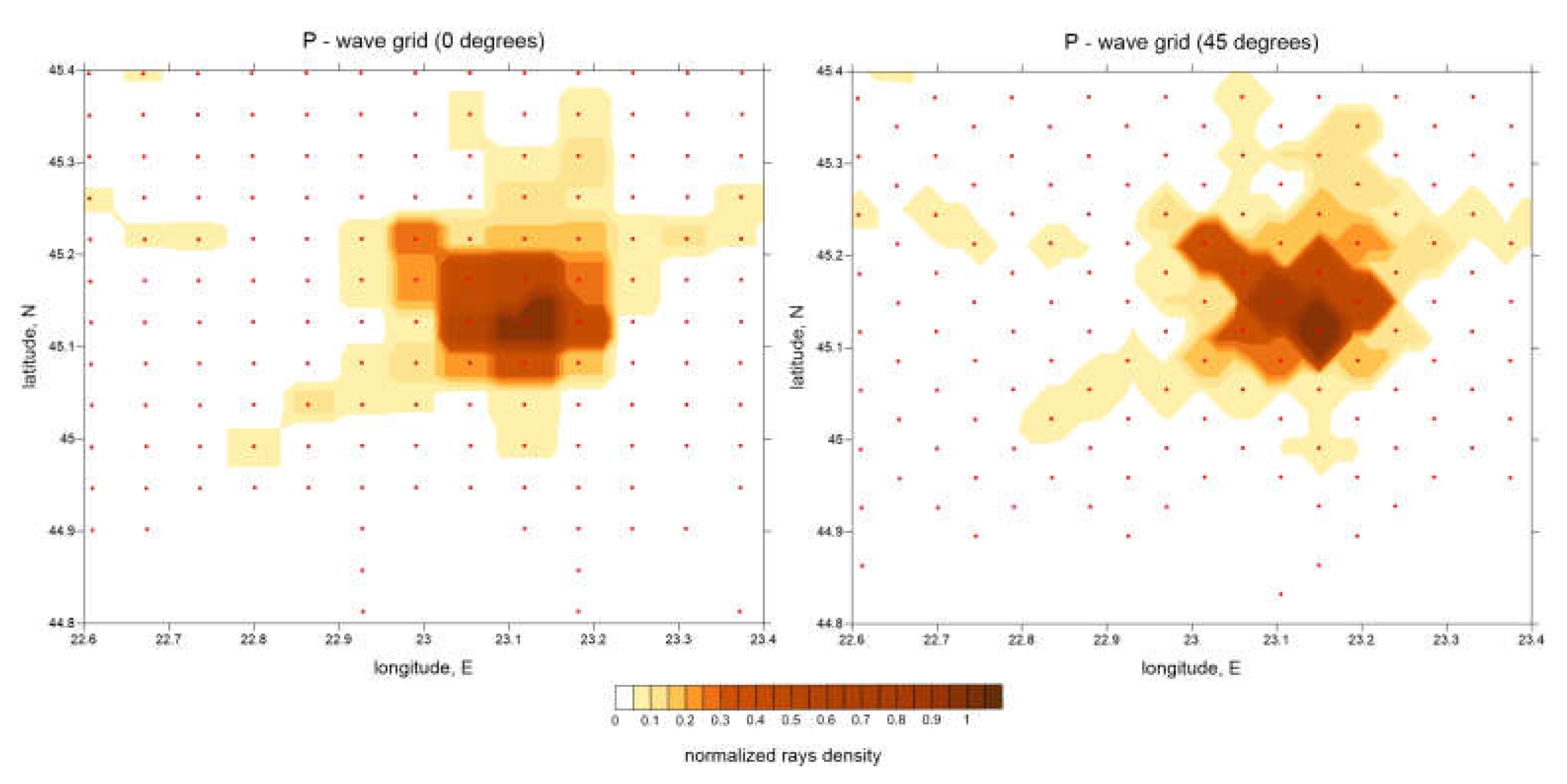

The velocity model was parameterized using a set of nodes distributed throughout the study volume, depending on ray coverage. Horizontally, these nodes were distributed regularly with a constant spacing of 5 km only in areas with sufficient ray coverage (

Figure 4), while vertically, the distance between nodes was set to 2 km.

To minimize potential artefacts related to the node geometry, the LOTOS code allows to perform the inversion using four grids with different baseline azimuths for node distribution (i.e., 0°, 22°, 45°, and 67°). After calculating the models for all grids, they were averaged and combined into a model with regular spacing, which was then used in the next iteration for source relocation. In total, we stopped at five iterations as a compromise between computational cost and minimizing nonlinear effects.

The inversion was performed using the Least Squares with QR decomposition (LSQR) [

28,

29]. Its stability was controlled by amplitude damping and flattening regularization which was defined from synthetic modeling as giving the best recovery of known structures. In our case, the coefficients were: amplitude damping and flattening of 4 and 7 for dVp and dVs, respectively.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. D Model Optimization

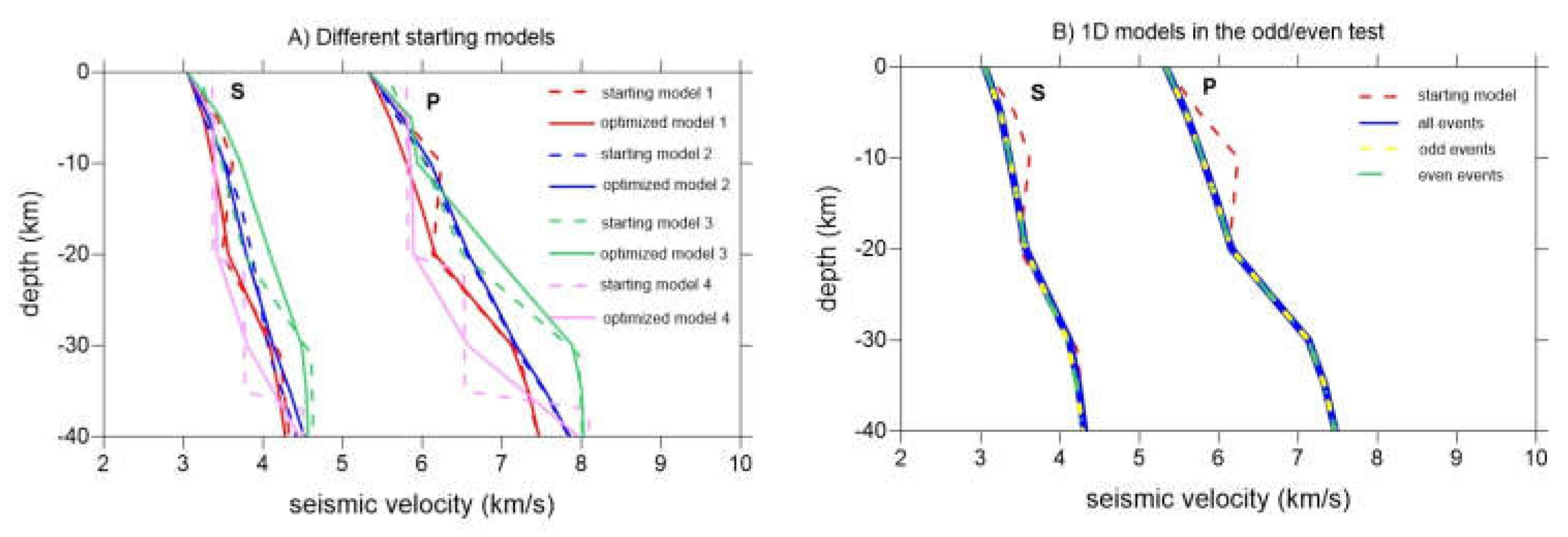

Data processing starts with preliminary source localization and 1D model optimization. The best 1D model that describes our data set was determined using several starting velocity models (

Figure 5A). We tested several 1D models previously developed by [

4] (model 2), [

30] (model 3) or [

31] (model 4), and we also developed a model (model 1) based on our data using the VELEST code [

32].

Figure 5A shows the starting models and their optimizations, and

Table 1 shows the RMS residuals after the first and fifth iterations.

The process for obtaining the 1D minimum velocity model for the Targu-Jiu region started with the selection of the initial realistic velocity models already tested for the western part of Romania [

4,

17,

30,

33]. The concept of the 1D minimum velocity model involves several parameters like station corrections, reference station and velocity. The station corrections influence the correctness of the 3D tomographic model [

32,

34] recommended using the VELEST method to start the 1D inversion process with a large number of small-depth layers and combined layers where the velocities converge to similar values during the inversion trial-and-error process. The 1D minimum velocity model is obtained from the inversion of the arrival times recorded at the station for each event.

Analyzing the values of the RMS residuals presented in

Table 1 we conclude that the most likely 1D model for our data is model 1, presented in

Table 2. The stability of the model was assessed by the "odd/even" test [

35]. The test consists of running inversions on subsets of the data obtained by separating events with even and odd identification numbers. The starting model for the odd and even subsets of data and for the entire data set is the same and corresponds to model 1 in

Figure 5A. The optimization results are similar for all cases and are shown in

Figure 5B. This test reveals that the dataset does not affect the stability of the 1D model optimization.

As shown in

Figure 5, the IASPEI91 model [

31], which is a global model, greatly underestimates the velocity values over the entire depth range and for this reason deviates the 1-D model obtained by inversion towards low values. On the contrary, the model proposed by [

30] (model 3) for the intra-Carpathian area overestimates the velocities, especially for larger depths (below 10 km). The most suitable models are located between these two extremes (models 1 and 2). We note that model 2 varies quasi-continuously with depth (no jumps in the velocity).

4.2. P & S Velocity Anomalies

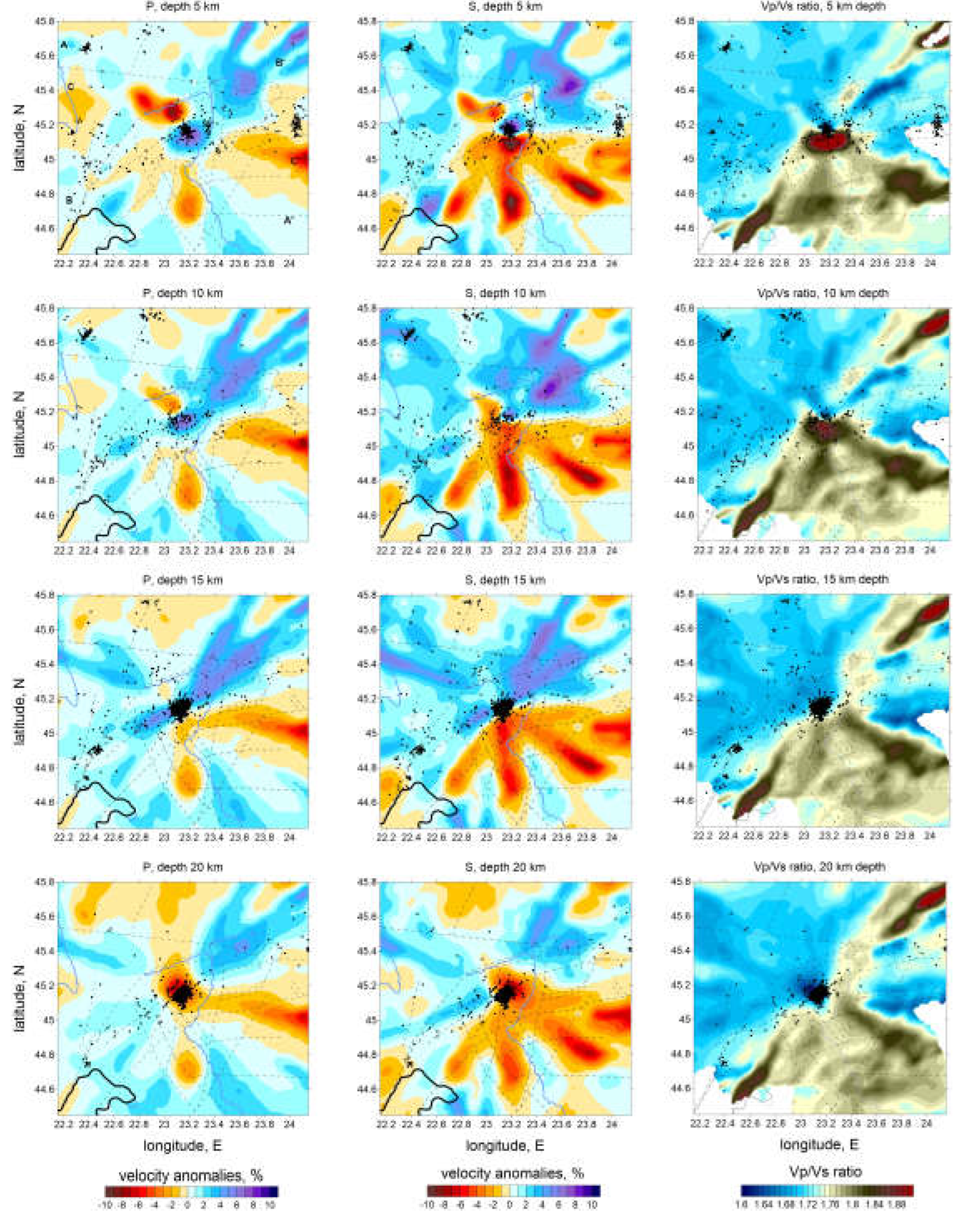

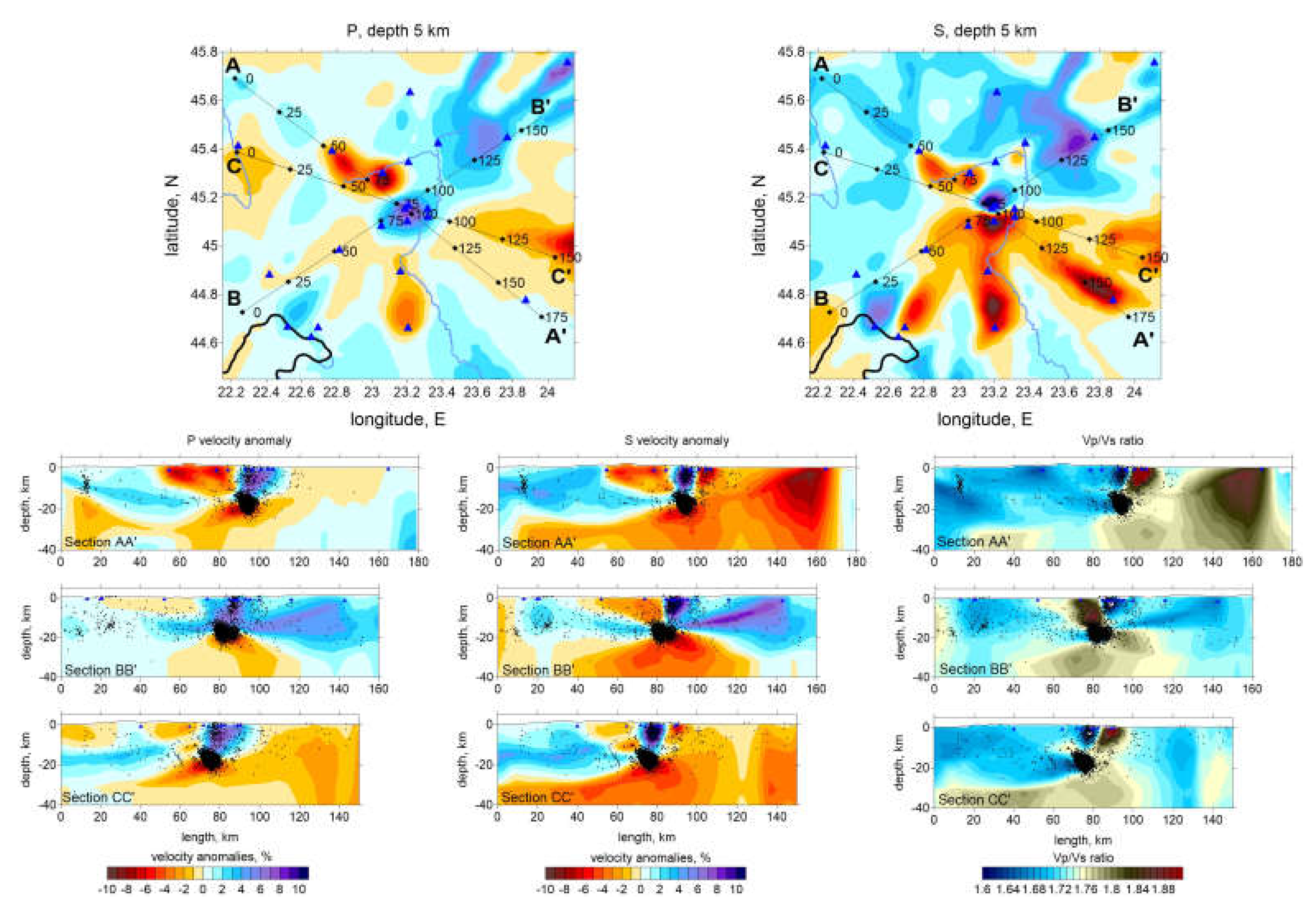

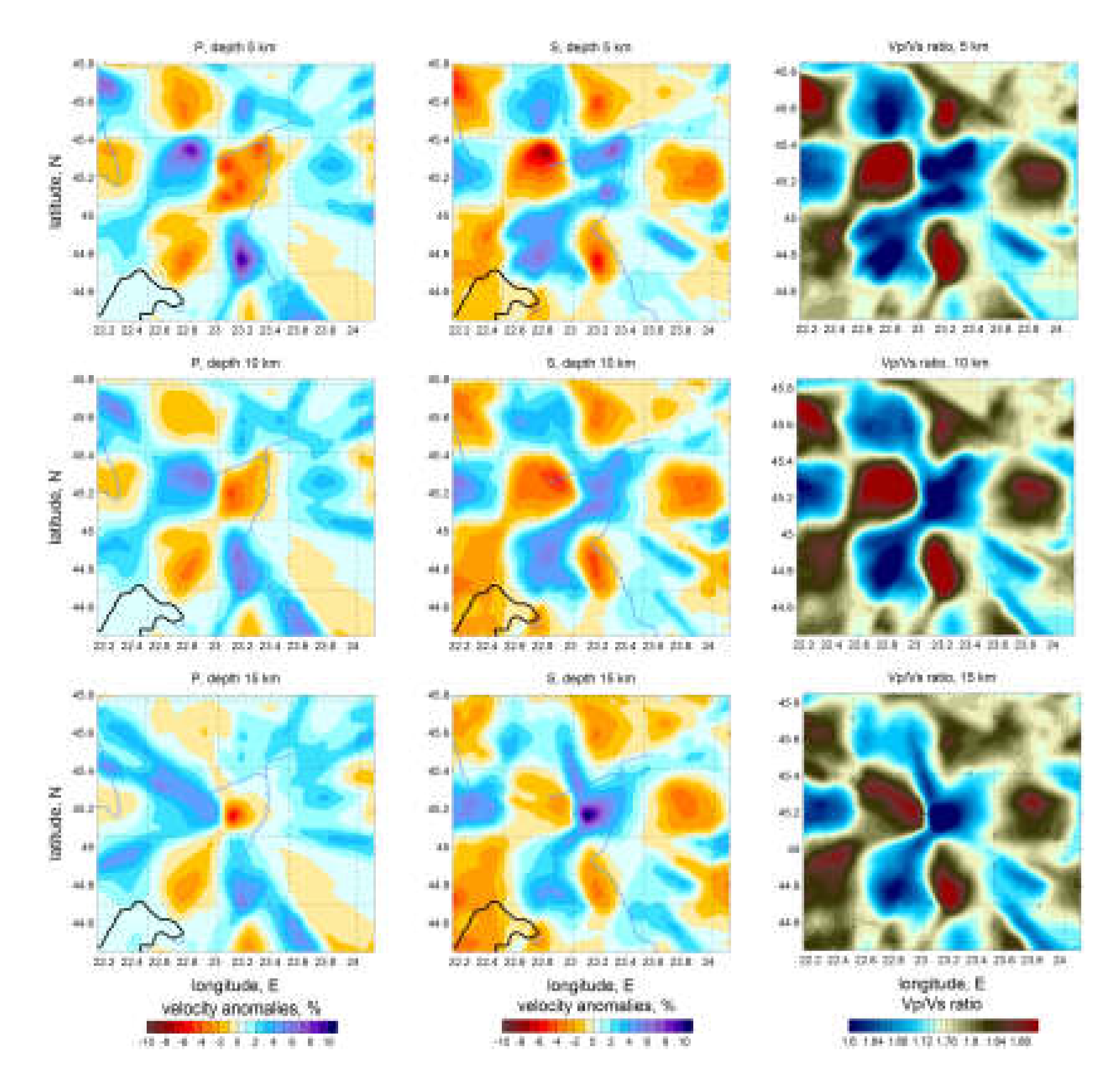

The main tomography results are the 3D models of P- and S-wave velocity models from a five-iteration inversion used to generate tomographic images, a compromise between computation time and quality of the solution (nonlinear effect reduction).

Figure 6 presents the results for P and S anomalies in horizontal slices at depths of 5, 10, 15 and 20 km and

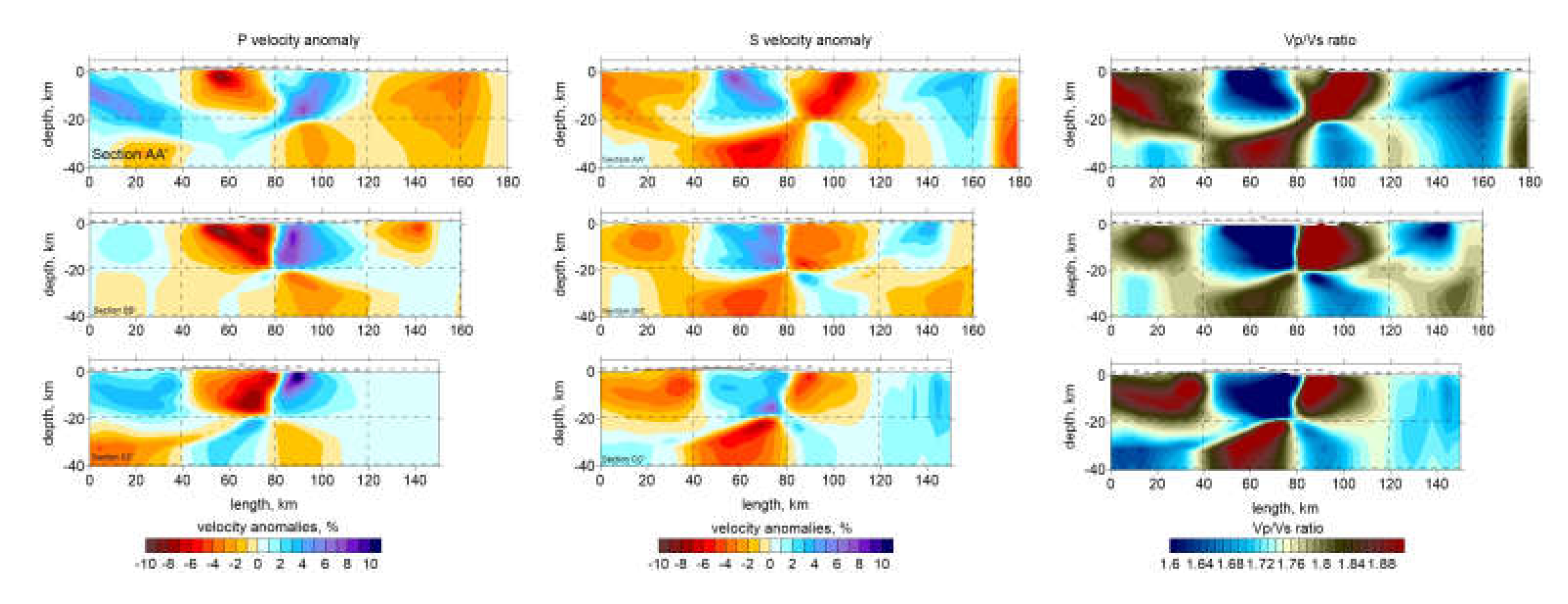

Figure 7 shows the anomalies for P and S and Vp/Vs ratio in three vertical sections passing through the study area.

P and S wave velocity structures are reasonably well correlated with each other in both horizontal and vertical representations. The vertical cross sections of the Vp/Vs ratio models, shown in

Figure 7, revealed similar structures as in the vertical cross sections of the resulting main P models. P and S models independently derived revealed the same structures and demonstrate that the existing data are sufficient to recover the discussed structures with confidence.

Analyzing the distribution of P-wave (Vp) and S-wave (Vs) velocities, distinct geophysical properties can be identified. First, a general NE-SW trend which separates two regions of contrast in velocity. The regions in the north and northeast of the maps, with high Vp and Vs values, indicate the presence of denser and more rigid rocks, possibly associated with consolidated geological units such as magmatic rock masses or closed and inactive faults. Areas with low Vp values may indicate the presence of less consolidated rocks, areas of intense fracturing, or the presence of fluids (groundwater, magmatic fluids, or gases). The NE-SW alignment crossing the epicentral area of the sequence of 2023 suggests the presence of an active fault oriented along this alignment. This is probably the fault on which the sequence was triggered in February 2023.

A significant low Vs anomaly overlaps with the central area of the map, where multiple earthquakes are located, suggesting the presence of weakly consolidated rocks with intense fracturing, as also observed in the representation of the main faults in the area [

36]. These negative anomalies also extend to the south and southeast to the Getic Depression, which is a sedimentary basin filled with 4–5 km of Paleozoic units [

37]. These units consist of loose formations with lower seismic velocities compared to the older and well-compacted Danubian units to the north. Seismic waves propagate more slowly through sedimentary formations [

38], but surface waves can be significantly amplified [

39]. This amplification effect increases the potential for destruction, as surface waves tend to cause more damage to buildings and infrastructure. Moreover, the numerous faults that cross the Getic Depression in a W-E direction represent a secondary factor that justifies the slow seismic velocities in this sedimentary basin.

The finger-like shape of the anomalies (the shape of a three-fingered hand) visible in Fig. 6 is reflecting an artificial modulation of the distribution of the anomalies due to the uneven ray coverage (the fact that the events are tightly clustered in the center and the stations are distributed over a large area giving a radial system of rays that does not provide sufficient ray intersections - see

Figure 3).

S-wave velocities are more sensitive to the presence of fluids, so their decrease in these regions may indicate the presence of fluids in crustal fissures. The Vp/Vs ratio in the central area is high, with values ≥1.8-1.9, which may suggest the presence of fluids in fractured rocks, contributing to a stronger decrease in S-wave velocity than in P-wave velocity. According to Fig. 6, this area matches with the seismically active region, suggesting that fluids [

40] play a role in fault rupture and slip processes. In the first stage of the sequence process, the hypocenters concentrated at lower depth (around 20 km) and then propagated upwards [

41]. Considering that the anomaly is located above this depth (roughly between 5 and 15 km depth), we can assume that the migration of hypocenters to the surface was facilitated by the presence of fluids. Fluids can also explain the anomalous long duration of the aftershock activity (more than one year). Additionally, high Vp/Vs values observed over a large area in the Getic Depression may be associated with the presence of weakly consolidated sedimentary rocks or hydrothermal alteration zones, which coincide with the extended area of hydrocarbon extraction.

Furthermore, the presence of thermal springs in the region is well known, reinforcing the idea of active hydrothermal processes. The anomalies in the southern part of the region could be correlated with sedimentary geological units, which exhibit low velocities and a high degree of fracturing.

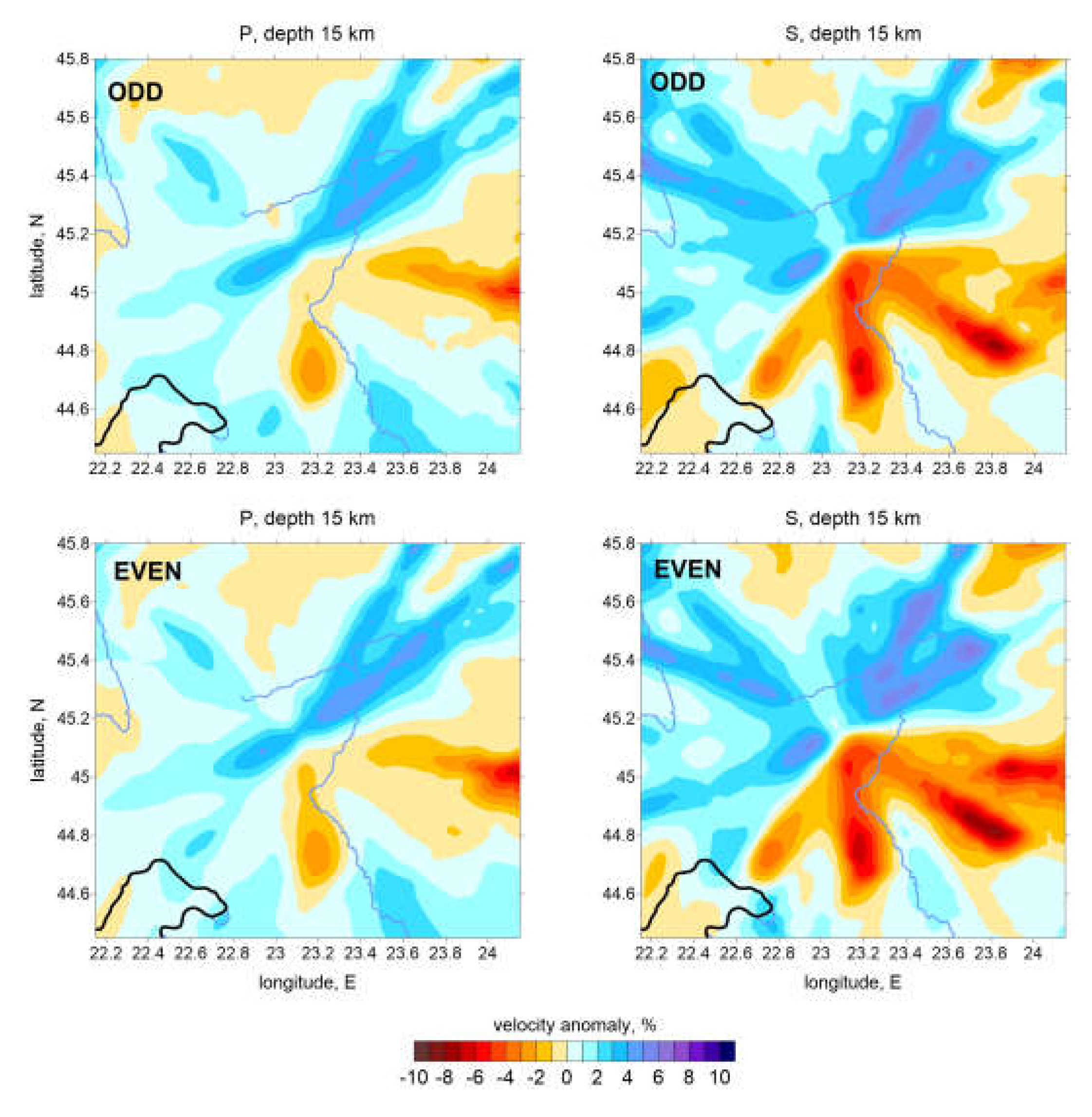

4.3. Data testing

To evaluate the random noise in the data, we performed an odd/even test in which we also evaluated the stability of the 1D model. Then, we compared the inversion results obtained with the same parameters. If the images are very different, it may indicate problems in the data or in the reconstruction algorithm. In our case, the results of the odd/even test for the P and S wave velocity anomalies at 15 km depth are presented in

Figure 8 and a good correlation of the structures can be observed.

The spatial resolution of the model was evaluated by synthetic tests in which we reproduced the same processing conditions of the experimental data. To define the modelling rays, we used the same source-receiver pairs as in the experimental dataset, with the event locations taken from the final solution of the main model.

The synthetic model was built by overlaying a set of 3D anomalies on a 1D reference model. Synthetic travel times were computed in the 3D model using a ray-tracing bending algorithm. To simulate realistic conditions, we introduced random noise with predefined standard deviations of 0.1 and 0.2 for the P-wave and S-wave data, respectively. These noise levels were selected to achieve a variance reduction comparable to that of inverting experimental data. The number of iterations and all control parameters during the synthetic model recovery were identical to those used to compute the main model. To optimize the recovery quality, we adjusted the control parameters during the synthetic tests and then applied these optimal values to the inversion of the experimental data in the main model. This process involved running the synthetic modelling and the experimental data inversion concurrently.

Figure 9 shows the results of a checkerboard test in which the synthetic anomalies were represented as 40 × 40 × 20 km. Within these cubes, alternating anomalies with amplitudes of ±5% were introduced. For dVp and dVs, anomalies were assigned opposite signs to enhance the contrast of the Vp/Vs ratio. Noise levels of 0.1 and 0.2 s were added to the P-wave and S-wave data, respectively. The inversion of the P and S wave data produced a variance reduction of about 55% and 50% for the P and S wave data, compared to those of the inversion of the experimental data, respectively 40% for P and 54% for S which shows a more accurate model than the original one. The recovered results in

Figure 9 are displayed in three depth sections, corresponding to the central regions of the anomalies in different layers.

The results show that in the first two layers, the recovered anomaly amplitudes are close to the original values for both P- and S-waves. However, in the deepest layer, the P-wave amplitudes appear slightly smaller. This suggests that a single set of damping parameters may not achieve optimal amplitude recovery across the entire survey volume. Increasing the damping to enhance recovery in deeper sections can result in amplitude loss in shallower regions, potentially obscuring important anomalies. To balance this, the damping value was selected to maintain the stability of anomaly shapes while minimizing noise artifacts.

To estimate the vertical resolution, we performed a synthetic test with anomalies defined along the vertical profiles. Typically, the vertical resolution is weaker than the horizontal resolution due to the trade-off between source depth and velocity distribution in tomography studies.

Figure 10 shows the vertical checkerboard P-wave vertical tests associated with the vertical profiles used to present the main results. In the horizontal direction, the anomalies were defined with a size of 40 km, and in the vertical direction, the anomaly signs changed at 20 km depth. The section thickness was 30 km. Model reconstruction was good, especially in regions with sources and ray intersections.

5. Conclusions

Seismic tomography is an essential tool for exploring the Earth's internal structure, providing at the same time valuable information about the dynamics of geological processes. We applied the LOTOS algorithm to investigate as in detail as possible the seismic velocity variations in the area located in the proximity of Târgu Jiu city, where a large earthquake sequence was recorded in 2023. The distribution of Vp and Vs anomalies reveals significant variations in the crustal structure, highlighting compact rock zones and areas affected by a complex system of faults and fractures. A well-defined NE-SW alignment is emphasized, separating a zone of high velocity toward the north-western side from a zone of low velocity toward the south-eastern side. It reflects the structural contrast between the orogen and the depression areas. It also coincides with the epicentral distribution of the sequence of 2023 and could be considered the active fault that generated this sequence. The alternation between high-velocity and low-velocity anomalies is visible in the area where the hypocenters are located. On the one side, the hypocenters appear to be located mostly in a high-velocity body (

Figure 7), but on the other side in the immediate vicinity of low-velocity anomalies, which makes us believe that fluids played an important role at least in the migration process of the hypocenters and could explain the unusually long duration of the aftershocks. Thus, the evidence of an anomaly with high Vp/Vs in the epicentral area, at a depth of around 10 - 15 km, may be an important argument in favor of the hypothesis of the presence of fluids in the tectonic process studied. The outcome of our analysis provides new elements for a better understanding of the crustal structure and tectonics in the Târgu Jiu area and can help improve seismic hazard and risk modeling at a regional scale.

Author Contributions

Z.B. performed the tomographic model calculation and prepared a substantial part of the manuscript, A.M. supplied the geotectonic of the area, D.R. provided the 1D velocity model input for the study, A.M. developed the scripts for data conversion to LOTOS format, N.C. and S.C. supplied the information about the seismic station network, R.M. provided important feedback during the writing of the paper. All authors participated in discussions of the results and contributed to writing the manuscript and preparing figures.

Funding

The APC was funded by grant no. PN23360301/2023 from NUCLEU Progam “Cercetări avansate pentru modelarea fenomenelor naturale şi antropice din sistemul cuplat Pământ - Atmosferă în scopul reducerii riscurilor asociate – SOL4RISC” supported by the Ministry of Education and Research.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are available in the repository: Zaharia, B., Andrei, M., Dinescu, R., Anghel, M., Neagoe, C., Radulian, M., & Schiffer, C. (2025). Data and LOTOS code to reproduce the results from "Seismic Velocity Anomalies and Fault Activity in the Târgu Jiu - Romania Region: A Tomographic Perspective" - Journal of Applied Sciences [Data set]. Zenodo.

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15099788. The files are currently embargoed. The record is publicly accessible. On August 15, 2025 the files will automatically be made publicly accessible. Until then, the files can only be accessed by users specified in the permissions. The embargo can be lifted after the article is accepted for publication.

Acknowledgments

This work was done in the framework of grant no. PN23360301/2023 from NUCLEU Progam “Cercetări avansate pentru modelarea fenomenelor naturale şi antropice din sistemul cuplat Pământ - Atmosferă în scopul reducerii riscurilor asociate – SOL4RISC” supported by the Ministry of Education and Research. We would like to thank Ivan Koulakov for discussions on the use and configuration of the LOTOS code for obtaining tomographic images.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NIEP |

National Institute for Earth Physics |

| NSN |

National Seismic Network |

| LOTOS |

Local Tomography Software |

| RMS |

Root Mean Square |

References

- Diaconescu, M. Sisteme de fracturi active crustale pe teritoriul României. PhD thesis. Faculty of Geology and Geophysics, University of Bucharest, September 2017, Published abstract in romanian, https://gg.unibuc.ro/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/DIACONESCU-Mihail.pdf. (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Koulakov, I. LOTOS code for local earthquake tomographic inversion. Benchmarks for testing tomographic algorithms. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am 2009, 99, 194–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulakov, I.; Zaharia, B.; Enescu, B.; Radulian, M.; Popa, M.; Parolai, S.; and Zschau, J. Delamination or slab detachment beneath Vrancea? New arguments from local earthquake tomography, Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2010, 11, Q03002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, B.; Grecu, B.; Popa, M.; Oros, E.; Radulian, M. Crustal Structure in the Western Part of Romania from Local Seismic Tomography, 7 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 95, 032019. [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, B.; Enescu, B.; Radulian, M.; Popa, M.; Koulakov, I.; Parolai, S. Determination of the lithospheric structure from Carpathian arc bend using local data, Romanian Reports in Physics 2009, 61, 748–764.

- Sandulescu, M. Geotectonica româniei. Bucharest: Editura Tehnica, Romania,1984; p. 336.

- Tarapoanca, M.; Tambrea, D.; Avram, V.; Popescu, B. The Geometry of the South Leading Carpathian Thrust Line and the Moesia Boundary: The Role of Inherited Structures in Establishing a Transcurent Contact on the Concave Side of the Carpathians. In Thrust Belts and Foreland Basins: From Fold Kinematics to Hydrocarbon Systems 2007 (pp. 369–384). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Linzer, H.G.; Frisch, W.; Zweigel, P.; Girbacea, R.; Hann, H.P.; Moser, F. Kinematic evolution of the Romanian Carpathians. Tectonophysics 297, 133–156. [CrossRef]

- Tarapoanca, M. Architecture, 3D geometry and tectonic evolution of the Carpathians foreland basin. Ph.D. thesis, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 120p, 2004.

- Matenco, L.; and Schmid, S. Exhumation of the Danubian nappes system (South Carpathians) during the Early Tertiary: inferences from kinematic and paleostress analysis at the Getic/Danubian nappes contact. Tectonophysics 1999, 314, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabăgia, T.; Maţenco, L. Tertiary tectonic and sedimentological evolution of the South Carpathians foredeep: tectonic vs eustatic control. Marine and Petroleum Geology 1999, 16, 719–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maţenco, L.; Bertotti, G.; Dinu, C.; Cloetingh, S.A.P.L. Tertiary tectonic evolution of the external South Carpathians and the adjacent Moesian platform (Romania). Tectonics 1997, 16, 896–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berza, T.; Draganescu, A. The Cerna-Jiu fault system (South Carpathians, Romania), a major Tertiary transcurent lineament. DSS Inst. Geol. Geofiz, 1988; 72–73, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, S.; Berza, T.; Diaconescu, V.; Froitzheim, N.; Fugenschuh, B. Orogen parallel extension in the Southern Carpathians. Tectonophysics 1998, 297, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saramet, M.R.; Hamac, C.; Chelariu, C. Subsidence analysis of the Getic Depression on Totea-Vladimir structure. Analele Stiintifice de Universitatii AI Cuza din Iasi. Sect. 2, 2014; 60, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Armeanu, Iulia; Chircea, Andreea; Ciobanu, Iulia; Craiu, Andreea; Craiu, George Marius; Dinescu, Raluca; Mihai, Marius; Predoiu, Andreea ; Tolea, Andreea; Varzaru, Lavinia-Cristina; Borleanu, Felix; Neagoe, Cristian; Radulian, Mircea; Mihaela, Popa (2024), “Database of the 2023 seismic sequence recorded in Gorj area (Romania)”, Mendeley Data, V3. [CrossRef]

- Dinescu, R.; Borleanu, F.; Radulian, M.; Popa, M.; Chircea, A.; Marius, M.; Rau, A.; Poiata, N.; Munteanu, I. The 2023 Seismic Sequence in The South Carpathians (Targu Jiu Area, Romania): Relocation Using an Improved 1-D Velocity Model and Seismicity Characteristics. 8th edition of the Geoscience International Symposium, 2023, Bucharest, Romania.

- Craiu, A.; Diaconescu, M. Stress field in Targu Jiu seismotectonic are (Romania): Insights from the inversion of earthquake focal mechanisms. In: Trofymchuk O, Rivza B (eds) 23rd International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference - SGEM 2023, Albena, Bulgaria, Conference Proceedings of selected papers, vol 23 (1.1), pp 601-608. [CrossRef]

- BRTT- Antelope Seismic Software. 1996. Available online: https://brtt.com/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- National Institute for Earth Physics (NIEP Romania). (1994). Romanian Seismic Network [Data set]. International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. Available online. [CrossRef]

- Cristian Neagoe. (2022). AdriaArray Temporary Network: Bulgaria, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Ukraine [Data set]. International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. [CrossRef]

- Oncescu M., C.; Marza, V.; Rizescu, M.; Popa, M. The Romanian earthquakes catalogue between 984 – 1997, in Vrancea Earthquakes: Tectonics, Hazard and Risk Mitigation, edited by F. Wenzel and D. Lungu, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1999, pp. 43 – 47.

- Bushenkova, N.; Koulakov, I.; Senyukov, S.; Gordeev E., I.; Huang, H.-H.; El Khrepy, S. Tomographic images of magma chambers beneath the Avacha and Koryaksky volcanoes in Kamchatka. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2019, 124, 9694–9713. [CrossRef]

- García-Yeguas, A.; Ibáñez, J.M.; Koulakov, I.; Jakovlev, A.; Romero-Ruiz, M.C.; Prudencio, J. Seismic tomography model reveals mantle magma sources of recent volcanic activity at El Hierro Island (Canary Islands, Spain), Geophysical Journal International 2014, 199, 1739–1750. [CrossRef]

- Koulakov, I.; Shapiro N., M.; Sens-Schönfelder, C.; Luehr B., G.; Gordeev E., I.; Jakovlev, A. Mantle and crustal sources of magmatic activity of Klyuchevskoy and surrounding volcanoes in Kamchatka inferred from earthquake tomography. Journal of Geophysical Research: SolidEarth 2020, 125, e2020JB020097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulakov, I.; Komzeleva, V.; Smirnov S., Z.; Bortnikova S., B. Magma-fluid interactions beneath Akutan volcano in the Aleutian Arc based on the results of local earthquake tomography. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2021, 126, e2020JB021192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junho Um, Clifford Thurber; A fast algorithm for two-point seismic ray tracing. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 1987, 77, 972–986. [CrossRef]

- Nolet Gust. Seismic Tomography with Applications in Global Seismology and Exploration Geophysics. Published in Dordrecht by Reidel, 1987, pp. x + 386.

- Paige, C. C. , and M. A. Saunders. LSQR: An algorithm for sparse linear equations and sparse least squares, Trans.Math. Software 1982, 8, 43–71. [CrossRef]

- Oros, E. Cercetări privind hazardul seismic pentru Banat (in romanian). Edition: 1. Publisher: Editura Sfantul Nicolae, Romania, 2022; pp. 1–394. ISBN: 978-606-30-4261-4.

- Kennett, B.L.N.; Engdahl, E.R. Traveltimes for global earthquake location and phase identification. Geophysical Journal International 1991, 105, 429–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissling, E.; Ellsworth, W. L.; Eberhart-Phillips, D.; Kradolfer, U. Initial reference models in local earthquake tomography. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Dinescu, R. Seismotectonic Framework of the South-West Carpathian Bend Zone. PhD Thesis, University of Bucharest, Faculty of Geology and Geophysics, Romania, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kissling, E.; Schmid, S. M.; Ansorge, J. A new method to determine the P-wave velocity structure of the crust and the uppermost mantle from refracted seismic waves. Geophysical Journal International 1995, 121, 803–815. [Google Scholar]

- Koulakov, I.; Bohm, M.; Asch, G.; Lühr, B.-G.; Manzanares, A.; Brotopuspito, K.S.; Pak, Fauzi; Purbawinata, M.A.; Puspito, N.T.; Ratdomopurbo, A.; Kopp, H.; Rabbel, W.; Shevkunova, E. P and S velocity structure of the crust and the upper mantle beneath central Java from local tomography inversion, J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, B08310. [CrossRef]

- Raileanu, V. and CEEX project members. (2008). Map of the main fault systems in Romania. CEEX Project no. 647/2005.

- Schleder, Z.; Lăpădat, I.A.; Trandafir, G.; Fernández, O.; Tămaș, D.M.; Tămaș, A.; Filipescu, S.; Krézsek, C.; Rădoiaș, M.A.; Vasiliu, M. Structural inheritance and style within the Getic Depression, South Carpathians, Romania. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2023, 148, 106068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinetti, N.P.; Martini, F. Sedimentary basins investigation using teleseismic p-wave time delays. Geophysical Prospecting 2019, 67(6-Geophysical Instrumentation and Acquisition), pp.1676-1685.

- Feng, L.; Ritzwoller, M.H. The effect of sedimentary basins on surface waves that pass through them. Geophysical Journal International 2017, 211, 572–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaujia, J.; Kumar M., R.; Vengala P., K.; Shekar, M. Indication of Fluid-Driven Seismicity in the Palghar Region, India, from Local Earthquake Tomography. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2025, 115, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulian, M.; Popa, M.; Dinescu, R.; Bala, A. Location improvements for the twin crustal earthquakes recorded on February 2023 in Gorj county, Romania. In: Trofymchuk O, Rivza B (eds) 23rd International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference - SGEM 2023, Albena, Bulgaria, Conference Proceedings of selected papers, 23, 57-64. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Tectonic framework of the Getic Depression in relation to Carpathian orogen and the Moesian Platform (modified after [

15]).

Figure 1.

Tectonic framework of the Getic Depression in relation to Carpathian orogen and the Moesian Platform (modified after [

15]).

Figure 2.

Distribution of seismicity and vertical sections used for seismic tomography in the study region. Black dots are the events. Colored triangles are seismic stations (blue for NSN, green for Adria and red for outside the border stations).

Figure 2.

Distribution of seismicity and vertical sections used for seismic tomography in the study region. Black dots are the events. Colored triangles are seismic stations (blue for NSN, green for Adria and red for outside the border stations).

Figure 3.

Data used for seismic tomography in the study area. Black dots are the events, and blue triangles are the seismic stations. The gray lines are horizontal projections of the ray path.

Figure 3.

Data used for seismic tomography in the study area. Black dots are the events, and blue triangles are the seismic stations. The gray lines are horizontal projections of the ray path.

Figure 4.

Distributions of nodes of two parameterization P wave grids (red dots) with different basic orientations (0 degrees, left and 45 degrees, right) used for the inversions. The background is the normalized ray density in the depth range 12.5 - 17.5 km.

Figure 4.

Distributions of nodes of two parameterization P wave grids (red dots) with different basic orientations (0 degrees, left and 45 degrees, right) used for the inversions. The background is the normalized ray density in the depth range 12.5 - 17.5 km.

Figure 5.

Optimization of the 1D model for observed data. A.) Optimization results with observed data and different starting 1D models. Different colours indicate different models, dotted lines are starting models and bold lines of corresponding colours are the optimization results. B.) Optimization results for halved data subsets in the odd/even test.

Figure 5.

Optimization of the 1D model for observed data. A.) Optimization results with observed data and different starting 1D models. Different colours indicate different models, dotted lines are starting models and bold lines of corresponding colours are the optimization results. B.) Optimization results for halved data subsets in the odd/even test.

Figure 6.

P and S velocity anomalies in horizontal slices, in percent with respect to the optimized 1D velocity model. Black dots depict the relocated sources around the corresponding depth levels, the main faults are presented with dotted lines.

Figure 6.

P and S velocity anomalies in horizontal slices, in percent with respect to the optimized 1D velocity model. Black dots depict the relocated sources around the corresponding depth levels, the main faults are presented with dotted lines.

Figure 7.

P velocity anomalies in vertical sections (left), S velocity anomalies (middle) and Vp/Vs ratio (right). The locations of the profiles are shown on top in the horizontal section for P and S. Dots indicate the relocated sources at distances less than 20 km from the profile.

Figure 7.

P velocity anomalies in vertical sections (left), S velocity anomalies (middle) and Vp/Vs ratio (right). The locations of the profiles are shown on top in the horizontal section for P and S. Dots indicate the relocated sources at distances less than 20 km from the profile.

Figure 8.

Odd/ Even events test.

Figure 8.

Odd/ Even events test.

Figure 9.

Checkerboard test to assess the spatial resolution. The anomalies are defined in cubes of 40 × 40 × 20 km. The recovered results for the dVp, dVs, and Vp/Vs ratio are shown in three horizontal sections. The shapes of the synthetic anomalies are highlighted with dotted lines.

Figure 9.

Checkerboard test to assess the spatial resolution. The anomalies are defined in cubes of 40 × 40 × 20 km. The recovered results for the dVp, dVs, and Vp/Vs ratio are shown in three horizontal sections. The shapes of the synthetic anomalies are highlighted with dotted lines.

Figure 10.

Vertical checkerboard test.

Figure 10.

Vertical checkerboard test.

Table 1.

RMS values for P and S wave residuals after the first and fifth iterations for different starting models.

Table 1.

RMS values for P and S wave residuals after the first and fifth iterations for different starting models.

Model

description |

RMS of P

Residuals, One Iteration (s) |

RMS of S

Residuals, One Iteration (s) |

RMS of P

Residuals, Five Iterations (s) |

RMS of S

Residuals, Five Iterations (s) |

| MODEL 1 |

0.3149 |

0.4755 |

0.1955 |

0.2142 |

| MODEL 2 |

0.3302 |

0.5013 |

0.2154 |

0.2698 |

| MODEL 3 |

0.5441 |

0.7611 |

0.2753 |

0.3316 |

| MODEL 4 |

0.4422 |

0.6086 |

0.2609 |

0.3135 |

Table 2.

P and S Velocities in the Reference 1-D model after optimization.

Table 2.

P and S Velocities in the Reference 1-D model after optimization.

| Depth (km) |

Vp (km/s) |

Vs (km/s) |

| 0 |

5.33 |

3.05 |

| -5 |

5.5918 |

3.2525 |

| -10 |

5.8036 |

3.3729 |

| -15 |

5.9989 |

3.4787 |

| -20 |

6.1647 |

3.5644 |

| -25 |

6.6443 |

3.8253 |

| -31 |

7.1269 |

4.0849 |

| -35 |

7.3346 |

4.1981 |

| -40 |

7.4671 |

4.2787 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).