1. Introduction

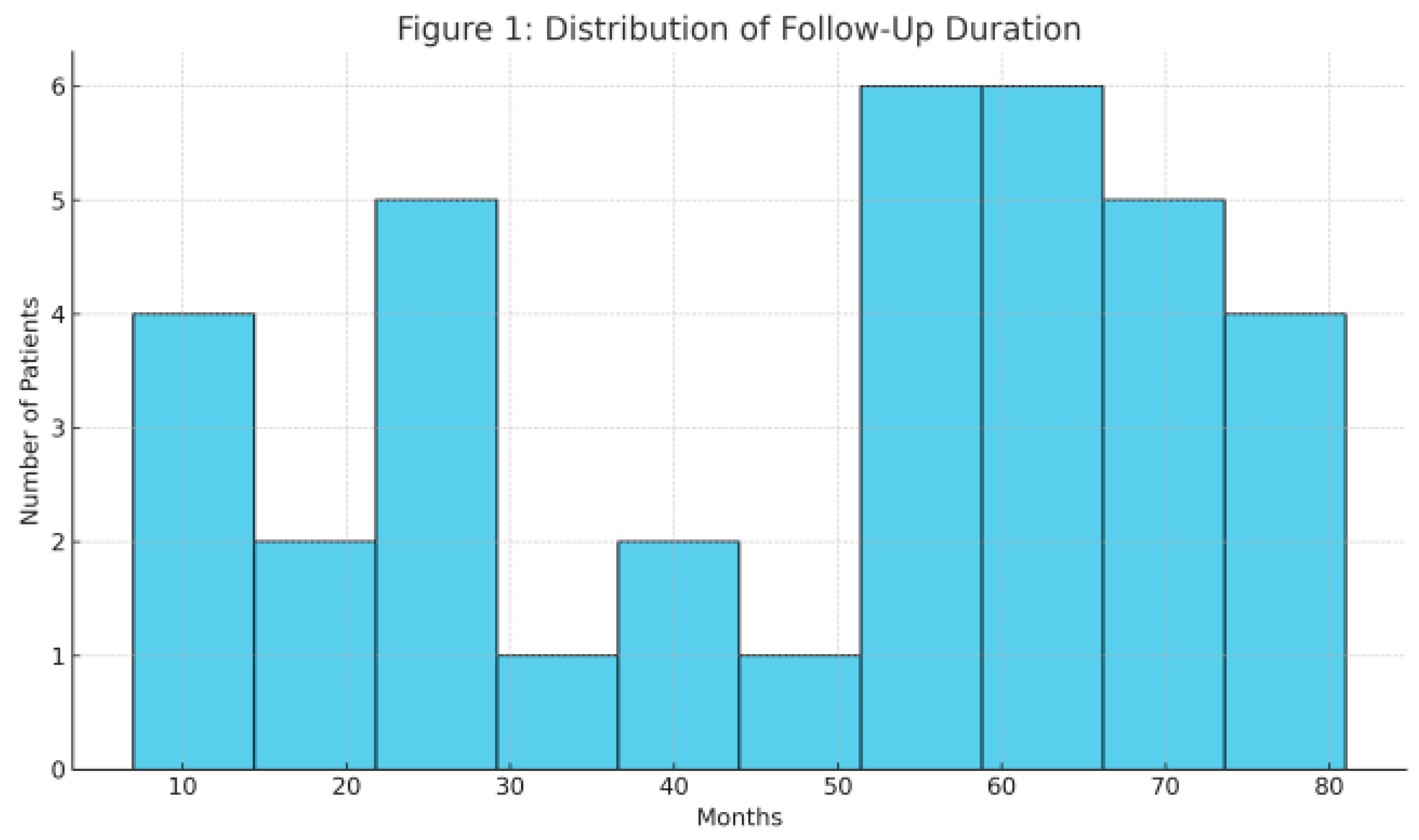

Figure 1. Distribution of surgical indications among the 36 pediatric patients.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier survival curve up to 7 years.

Figure 3. Incidence of complications (early and midterm).

Figure 4. Spearman correlation analysis between follow-up duration and mean gradient.

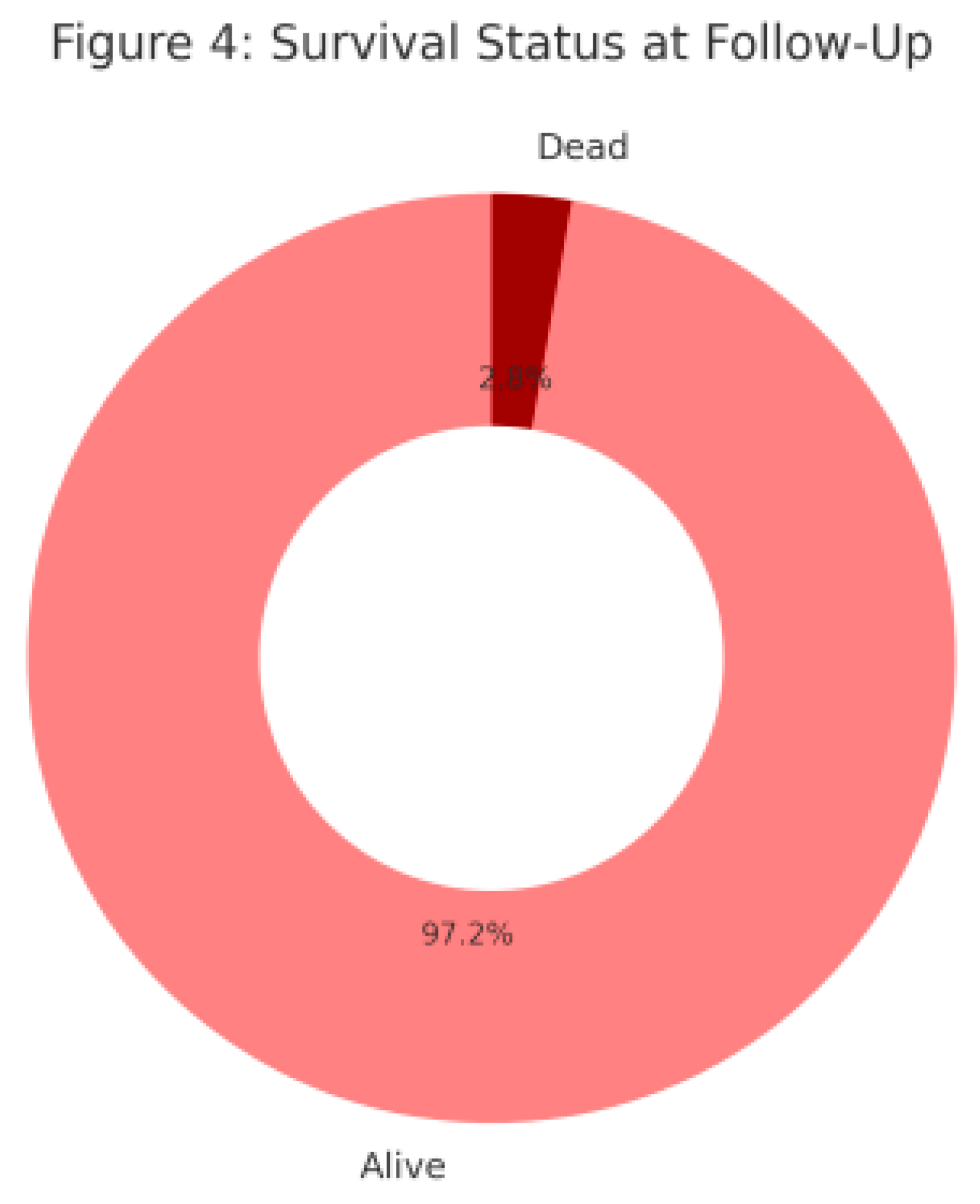

Figure 4.

Survival Status at Follow-Up. A donut chart demonstrating patient survival during the study. One patient (2.8%) died at home during late follow-up.

Figure 4.

Survival Status at Follow-Up. A donut chart demonstrating patient survival during the study. One patient (2.8%) died at home during late follow-up.

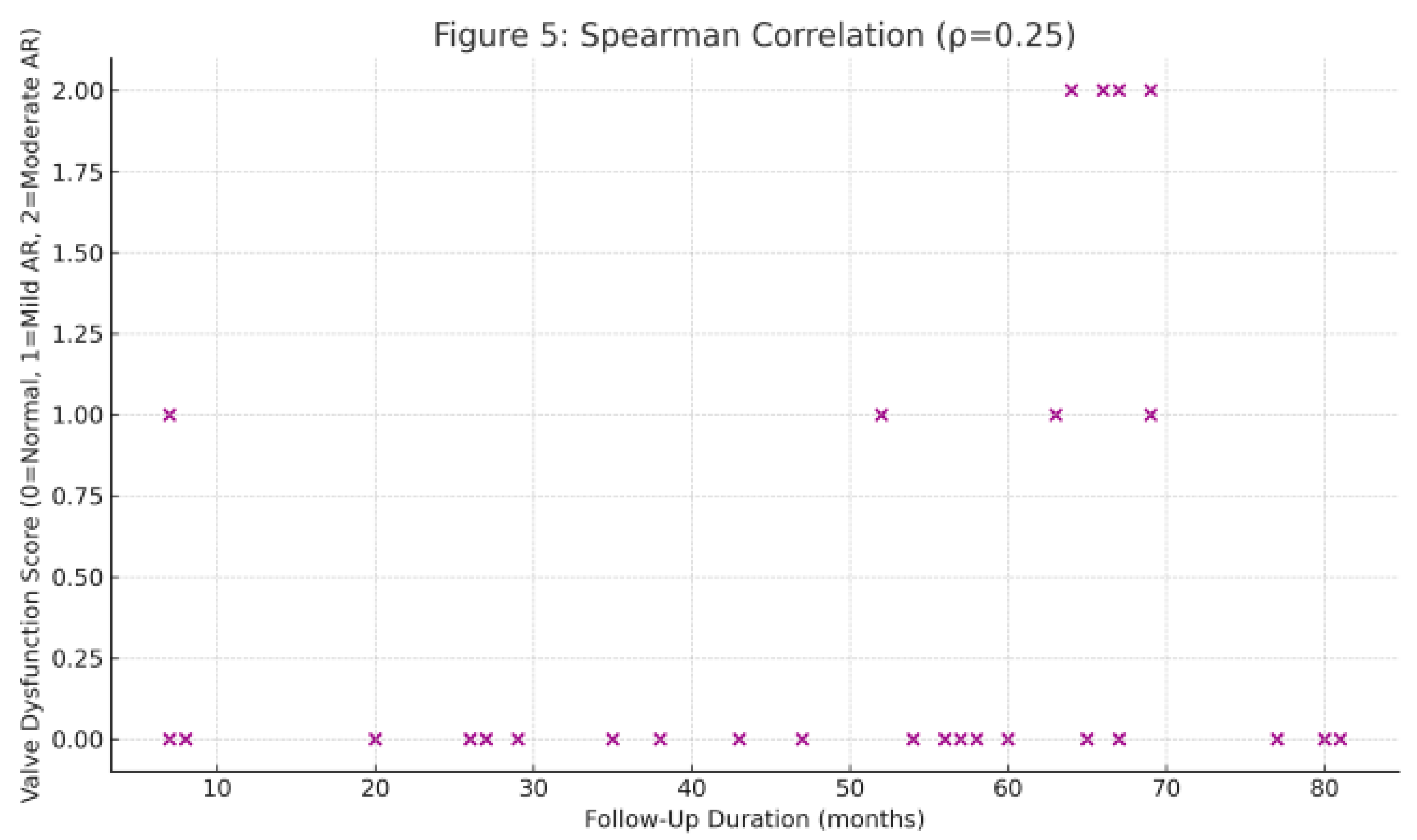

Figure 5.

Spearman Correlation Between Follow-Up Duration and Valve Function.This scatter plot shows the correlation between follow-up duration and valve dysfunction score. A positive trend is observed.

Figure 5.

Spearman Correlation Between Follow-Up Duration and Valve Function.This scatter plot shows the correlation between follow-up duration and valve dysfunction score. A positive trend is observed.

Aortic valve and root diseases in children represent a significant surgical challenge due to anatomical complexity, somatic growth potential, and limitations of traditional valve substitutes. Although mechanical valve replacement remains effective, its disadvantages—such as lifelong anticoagulation, increased risk of thromboembolic events, and valve-related complications—are particularly concerning in the pediatric population [

1,

2]. In this context, cryopreserved aortic homografts (CH) have emerged as a valuable alternative in selected pediatric patients. Their low thrombogenicity, reduced susceptibility to infection, and favorable hemodynamic properties support their clinical use [

3,

4]. Homografts are particularly preferred in cases of active infective endocarditis, complex congenital aortic valve disease with annular hypoplasia, or contraindications to anticoagulation therapy [

5,

6].

Moreover, homografts are widely used in reoperative scenarios following failed Ross procedures, in aortic root reconstructions, and in neonates or small children for whom prosthetic valves are not feasible due to size limitations [

7,

8]. Despite concerns regarding long-term durability and availability, midterm outcomes in children remain promising, with acceptable rates of structural valve deterioration [

9,

10]. Given the challenges posed by small annular dimensions and growth potential in this age group, homografts offer a viable solution due to their infection resistance and the absence of anticoagulation requirements. In this study, we present our single-center experience of aortic homograft implantation in 36 pediatric patients aged 2 to 7 years. Our objective is to evaluate the surgical indications, early and midterm outcomes, and the clinical role of homografts in pediatric aortic valve and root surgery.

3. Results

Demographic characteristics and surgical indications of the 36 patients were analyzed. The mean age was 4.3 ± 1.6 years, with 60% (n=22) being male. Surgical indications are summarized in

Table 1. The average homograft diameter was 13.2 ± 2.1 mm, reflecting the need for anatomical adaptation in this young cohort. The mean cardiopulmonary bypass time was 112 ± 35 minutes, and the mean aortic cross-clamp time was 91 ± 28 minutes.

Regarding early outcomes, there was no 30-day mortality (0%), indicating a high safety profile of the procedure in this cohort. Postoperative complications were limited to one case of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) (2.8%, n=1), which was successfully managed medically. No bleeding complications were reported. Echocardiographic assessment revealed a mean aortic gradient of 8.4 ± 3.2 mmHg with minimal regurgitation (<5% moderate to severe, n=1), confirming satisfactory hemodynamic performance of the homografts. During the first year, all valves maintained function and structural integrity without the need for reoperation.

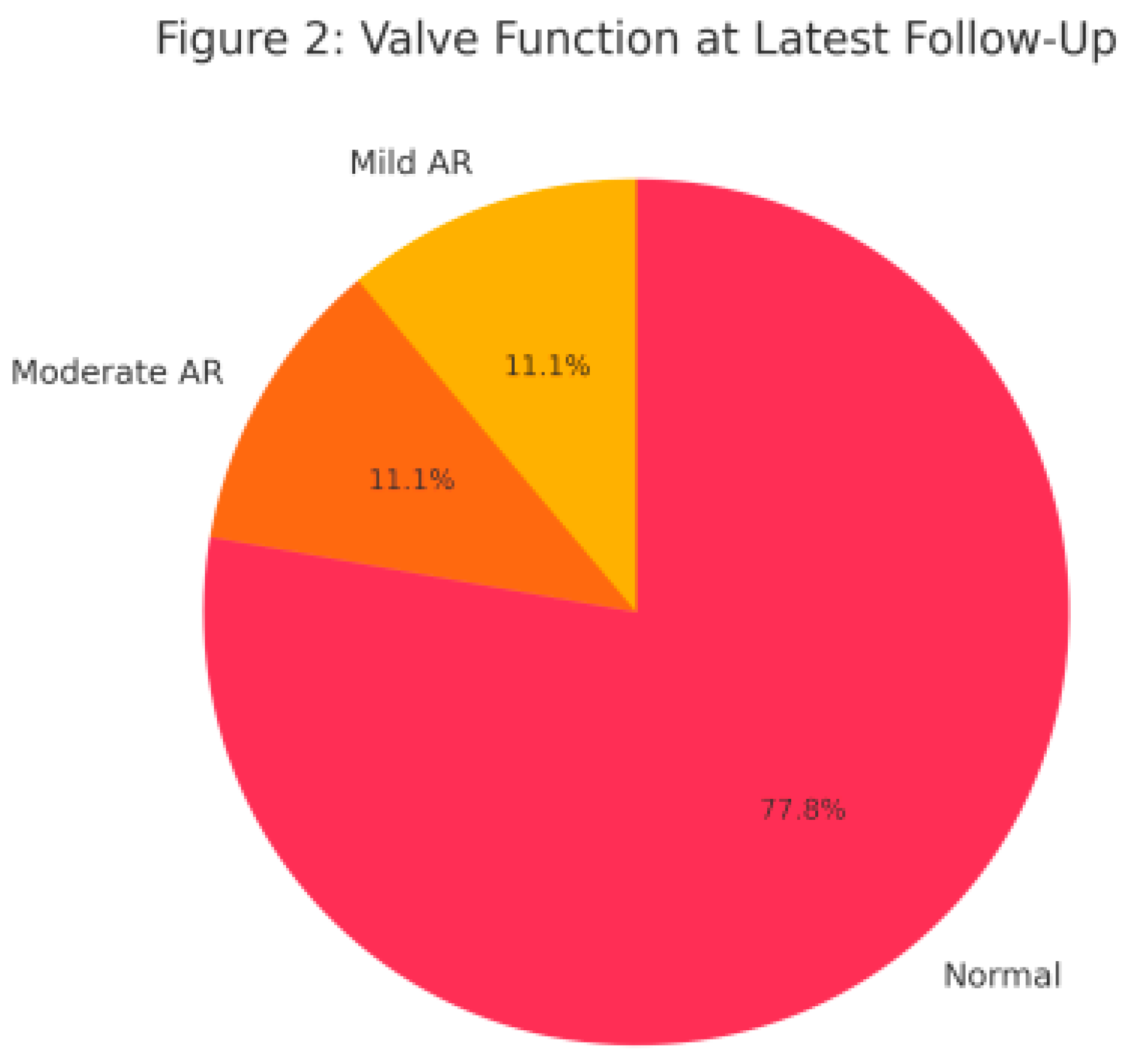

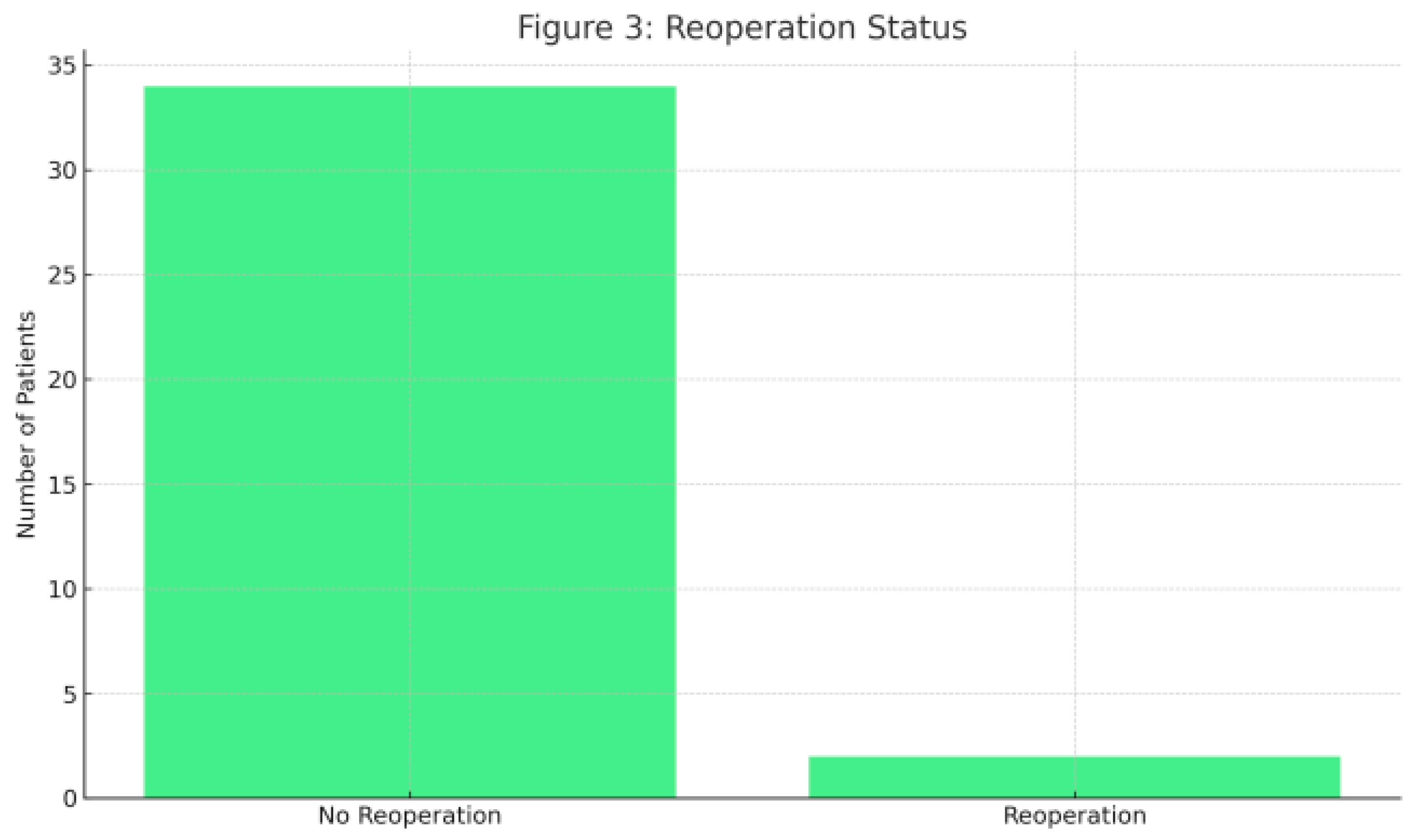

At midterm follow-up, 10 patients completed 3-year follow-up without any structural valve deterioration or reoperation. However, one patient died at home during the third year, with the cause of death unknown. In the long-term, one patient underwent reoperation in the fourth year due to homograft root aneurysm, and another—originally operated at an outside center—required homograft replacement in the seventh year due to severe AR. At 5-year follow-up (n=14), 13 patients (92.9%) showed normal valve function with no graft abnormalities; mild-moderate AR was observed in one patient (7.1%). Remaining patients are still under follow-up with stable valve function and graft integrity at an average of 24 ± 12 months. Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated a 5-year survival of 97.2% (35/36) and a 7-year survival of 94.4% (34/36)

4. Discussion

Cryopreserved homografts represent a valuable option for aortic valve replacement in pediatric patients due to their low thrombogenic potential and the absence of need for long-term anticoagulation. These valves, derived from human donor tissue, are particularly preferred in cases of active infective endocarditis owing to their biocompatibility and favorable hemodynamic performance [

11]. However, their lack of durability compared to mechanical valves and inability to accommodate somatic growth limit their long-term efficacy [

11]. In this study, we evaluated early and mid-term outcomes in 36 pediatric patients who underwent cryopreserved aortic homograft replacement, accompanied by a comprehensive literature review.

No early mortality was observed in our cohort, while one late mortality case (2.8%) occurred at home three years postoperatively, with an unknown cause. Similarly, Lounsbury et al. reported no early mortality in their series involving 38 pediatric patients undergoing aortic homograft implantation [

12]. The low mortality rates in both studies suggest that homograft use in the pediatric population is associated with an acceptable safety profile.

Lounsbury’s study further demonstrated that homograft function remained stable in 74% of patients over a median follow-up of 81 months. A 21% reoperation rate was noted, primarily due to homograft failure at an average of 92 months [

12]. In comparison, our study reported only two reoperations (5.6%) during a mean follow-up of 36 months—one due to root aneurysm at year four and another due to severe aortic regurgitation at year seven. By year five, homograft function was preserved in 92.9% of our cases, with no calcification observed. These findings are consistent with the notion that homografts maintain high safety in the early period and that long-term durability is influenced by age, surgical technique, and patient selection.

A similar study [

13] indicated that younger pediatric patients demonstrated lower calcification tendencies, with reoperation rates remaining under 10% within 5–7 years, which aligns with our results. In a broader series by Binsalamah et al. including 206 pediatric patients, early mortality and early reoperation rates in the homograft group (n=83) were reported at 4.8% and 3.6%, respectively [

14]. Late mortality was 3.6%, while late reoperation occurred in 18.1% of cases, primarily due to graft dysfunction, valve deterioration, or root dilation [

14]. These findings support that homografts are safe in the early period but require careful long-term evaluation due to structural durability concerns.

In our cohort, one mid-term reoperation and one late at-home death were observed. Most patients followed up to five years showed preserved homograft function, with only one case of root aneurysm requiring reoperation and one patient developing late-onset sudden death. Echocardiographic evaluation revealed preserved valve function in 92.9% of cases at five years, with only one case of mild-to-moderate regurgitation. These results support the early safety of homografts while highlighting that long-term durability depends on patient selection, graft quality, and surgical technique.

Recent literature highlights both the advantages and limitations of cryopreserved homografts. Frankel et al. emphasized the low immunogenicity of these grafts but also noted limited long-term durability data and the ongoing risk of early calcification and structural deterioration [

3]. Anatomical compatibility and hemodynamic superiority of homografts make them particularly advantageous in young patients where Ross procedures are not feasible. Nevertheless, innovative strategies and individualized follow-up protocols remain necessary to enhance long-term outcomes [

15].

Nappi et al. reported that cryopreserved allografts yielded acceptable long-term results in selected patients, with 27% structural valve degeneration and 33.8% reoperation rates over 20 years. All-cause mortality was 32.4%, with valve-related cardiac mortality at 13.8% [

13]. These findings suggest limited long-term durability in younger adults. In contrast, our study, with a mean follow-up of 36 months in patients aged 2–7 years, showed only a 5.6% reoperation rate and 2.8% late mortality, indicating strong durability and low complication rates in the early and mid-term period.

In a multicenter analysis by Horke et al., previous series linked cryopreserved homografts (CH) to 15–40% early structural degeneration and a high risk of calcification, especially in younger patients whose somatic growth could not be accommodated by the graft, leading to significant late regurgitation or stenosis [

16]. Pediatric series using CH also reported 20–40% reoperation rates within 5–10 years, attributed to both degeneration and immune responses. The presence of viable cells in CH may trigger immunologic activation, leading to early graft thickening and degeneration [

16]. Fukushima et al. reported a 48.2% reoperation rate in a series of 840 patients over 17 years, mostly due to structural degeneration [

10]. In our cohort, only two patients (5.7%) required reoperation by year seven, demonstrating a significantly lower rate and suggesting acceptable mid-term durability in selected pediatric patients. One case involved graft dysfunction, the other root dilatation—patterns similar to those in the Fukushima study.

In a randomized controlled trial by El-Hamamsy et al., 10-year survival and freedom from reoperation in Ross patients were 97% and 96%, respectively, compared to 83% and 86% in the homograft group [

5]. These results suggest superior durability for the Ross procedure. However, in our study, a cryopreserved homograft was successfully used to treat a failed Ross autograft, demonstrating its continued relevance in such cases.Lupinetti et al. reported a 16% calcification rate and limited annular expansion in homograft recipients, whereas these issues were absent in the autograft group. Reoperation was required in 12% of homograft patients vs. 6.4% in the autograft group [

17]. While homografts are safe and effective in the short term, autografts may offer better long-term outcomes in growing children. Therefore, homograft use should be individualized based on age, growth potential, and expected follow-up duration.

Cryopreserved homografts have been clinically used since the 1960s and became widespread in the 1980s with standardized cryopreservation techniques [

2,

14]. These grafts are stored in liquid nitrogen and offer advantages such as infection resistance and no need for anticoagulation [

3]. However, they carry a risk of immune reaction and calcification due to preserved donor cells [

18]. Decellularized homografts, developed in the early 2000s, aim to reduce these immune responses [

16].

Horke et al. reported a 1.4% 30-day mortality for decellularized homografts—lower than the 3.3–6.9% seen with CH—and suggested that reduced immunogenicity may be responsible [

16]. In our series, only 2.8% of patients developed supraventricular tachycardia, with no bleeding or infection. Horke et al. noted no major complications except 0.7% pacemaker implantation in decellularized homografts, possibly due to lower inflammatory responses.

ate complications differ significantly between CH and decellularized grafts. In our cohort, only 7.1% developed mild-to-moderate regurgitation at five years, and two reoperations were required at year seven. Literature suggests 10–15% structural failure for CH at five years [

14], exceeding our findings. Dignan et al. proposed that such degeneration is immune-mediated [

18], potentially explaining our late regurgitation case. Horke et al. reported a 6% explantation rate for decellularized homografts at five years, primarily due to outgrowth stenosis (62.5%), endocarditis (25%), or root aneurysm (12.5%). These grafts also showed favorable annular adaptation with growth [

16], a notable advantage over CH, which lack growth potential and are more prone to late degeneration and calcification [

2,

14].

Each graft type’s early and late complications stem from distinct processing differences. CH provides rapid access in infected cases [

6], while decellularized grafts offer superior immunologic stability [

16]. Future studies should focus on mitigating immune responses and enhancing long-term outcomes through advanced biotechnology and broader pediatric cohorts.

In conclusion, cryopreserved homografts remain a reliable option for aortic valve replacement in pediatric patients, offering low early complication rates. Despite a higher long-term risk of degeneration and calcification compared to decellularized homografts, CH remains a valuable solution in children aged 2–7 years due to their infection resistance and anticoagulation-free profile. We believe that addressing immunogenicity through emerging techniques will further improve homograft outcomes. Sarikouch et al. also reported promising early recellularization data for decellularized valves, suggesting their potential to promote physiological integration and reduce immune response