1. Introduction

Crowd psychology has long been the focus of extensive scientific research. A key aspect of this field, relevant to the present study, concerns individual behaviour during crowd stampedes in panic evacuations. This phenomenon was first delineated and categorised in the psychological literature, drawing upon empirical data, by Mintz [

1] and Quarantelli [

2], among others, in the early 1950s. Later, the evacuation process was analysed in terms of decision-making mechanisms [

3,

4,

5]. Interest in modelling crowd behaviour emerged in the early 1990s [

6,

7], and soon thereafter, researchers began to incorporate panic situations into these models, with some of the first theoretical assumptions published by Helbing et al. [

8].

The motivation for developing simulation models of crowd evacuation, particularly those focussing on the dynamics of a crowd stampede, is understandable, given the numerous incidents that have led to disastrous outcomes and significant fatalities [

9]. Moreover, panic-inducing events not only cause human casualties but also incur considerable social and economic costs [

10]. Consequently, this subject remains a major focus within both social science and safety engineering.

At present, there are no explicit legal obligations in Poland requiring the analysis of building designs to reduce the likelihood of panic evacuations [

11,

12]. A similar situation exists in other countries, which is perhaps understandable given that crowd stampedes are neither common nor easily predictable. However, when such events do occur, the consequences can be tragic [

13,

14,

15]. This highlights the need for a dedicated analysis to assess the necessity and potential scope of legislative amendments. Despite the absence of explicit legal stipulations, existing knowledge on panic evacuation can be applied through the legal framework’s provision for so-called substitute solutions. These solutions allow for the use of existing buildings that do not fully comply with current requirements, as well as the design of new buildings that deviate from these standards. In such cases, replacement measures must be implemented to mitigate the adverse impact of non-conformities on fire safety. In Poland, the acceptance of replacement solutions is predicated on a technical expert opinion on the state of fire protection [

16], prepared by building and fire protection experts [

17]. In enclosed spaces intended for large numbers of people, it is considered good practice to assess the potential exposure to crowd stampedes, particularly because empirical evidence suggests that the aftermath of a panic evacuation may result in more casualties than the event itself [

18].

Panic during evacuation, often referred to as a crowd stampede, is inherently unpredictable and dangerous. Consequently, it is hypothesised that conducting full-scale experiments under real conditions is not feasible. Although analyses based on actual visual recordings have been conducted—for example, in the cases of earthquakes [

19,

20] or religious festivals [

21]—such opportunities are limited by the scarcity and poor quality of the available footage.

Notably, according to the extant literature, the dynamics observed in the orderly movement of people under normal conditions differ considerably from those that occur when self-control is lost during an evacuation. One of the aims of this article is to clarify the principles that have been studied and analysed thus far regarding how evacuees behave according to their emotional state. This study is based on a literature review, the findings of which are distilled into conclusions that outline prospective research directions and perspectives. Ultimately, the long-term objective of this research is to enhance the safety of building occupants by reducing the likelihood of a crowd stampede during a panic evacuation. The author also intends to conduct further research to develop a theoretical foundation for the advancement of panic evacuation modelling.

2. Panic Evacuation Characteristics

A comprehensive review of the existing literature, including sociological and psychological publications, media reports, empirical studies, and counselling books, allows us to identify the defining characteristics of runaway panic [

8]:

Individuals tend to move, or attempt to move, at speeds that exceed their usual pace.

Physical pushing occurs as interactions between people become increasingly forceful.

Movement, particularly when negotiating constricted spaces, becomes uncoordinated.

Crowds thicken at exits, often forming curved edges.

Congestion develops.

Physical interactions within the dense crowd generate pressures of up to 4450 N/m, which can bend steel barriers or knock down brick walls.

The egress process is further impeded by fallen or injured individuals, who become obstacles themselves.

A tendency to adopt uniform, crowd-like behaviour is evident.

Alternative exits are often overlooked or used ineffectively.

An interesting study using social network analysis examined 78 instances of panic evacuation, identifying 17 factors associated with the onset of crowd panic [

22]. The most prevalent risk factors include the following:

Crowds with densities that exceed critical thresholds.

Pedestrian trips and falls.

Inadequate implementation of safety measures.

Indirected movement of the crowd.

The absence of effective on-site monitoring.

During the literature review, a recurrent research challenge emerged: distinguishing between causes, effects, and accompanying phenomena, particularly in complex scenarios such as panic evacuations. A primary detrimental aspect of crowd evacuation is the formation of congestion at bottlenecks. This congestion can act both as a cause and an effect, creating positive feedback loops. Therefore, further investigation, ideally through experiments that closely resemble actual conditions, is imperative. Such research could reveal the underlying principles governing congestion during large-scale evacuations and identify measures to mitigate the negative impacts of crowd stampedes, potentially informing legislative changes.

One objective of this study is to assess the practical applicability of the research findings published to date, along with the analysis presented herein. To this end, the study has identified key areas related to legal technical and construction requirements for safe evacuation that may require modification in scenarios where a crowd stampede is a risk. The evacuation requirements to be analysed include the following:

The width of a single emergency exit.

The number of emergency exits.

The length of an evacuation passage (within the room).

The length of an evacuation access (from the room to the safe zone).

Provision of smoke ventilation.

Use of a voice alarm system.

Each of these phenomena will also be examined for its potential impact on evacuation requirements. The aim is to identify dependencies that can guide the selection or modification of measures to reduce the likelihood of panic evacuations or minimise their adverse impact on evacuation safety.

3. Phenomena Associated with Panic Evacuation

3.1. Velocity of Movement Is Contingent upon Crowd Density

Numerous studies have established a clear correlation between movement velocity and crowd density. These findings have been comprehensively summarised by Thompson and Marchant [

23].

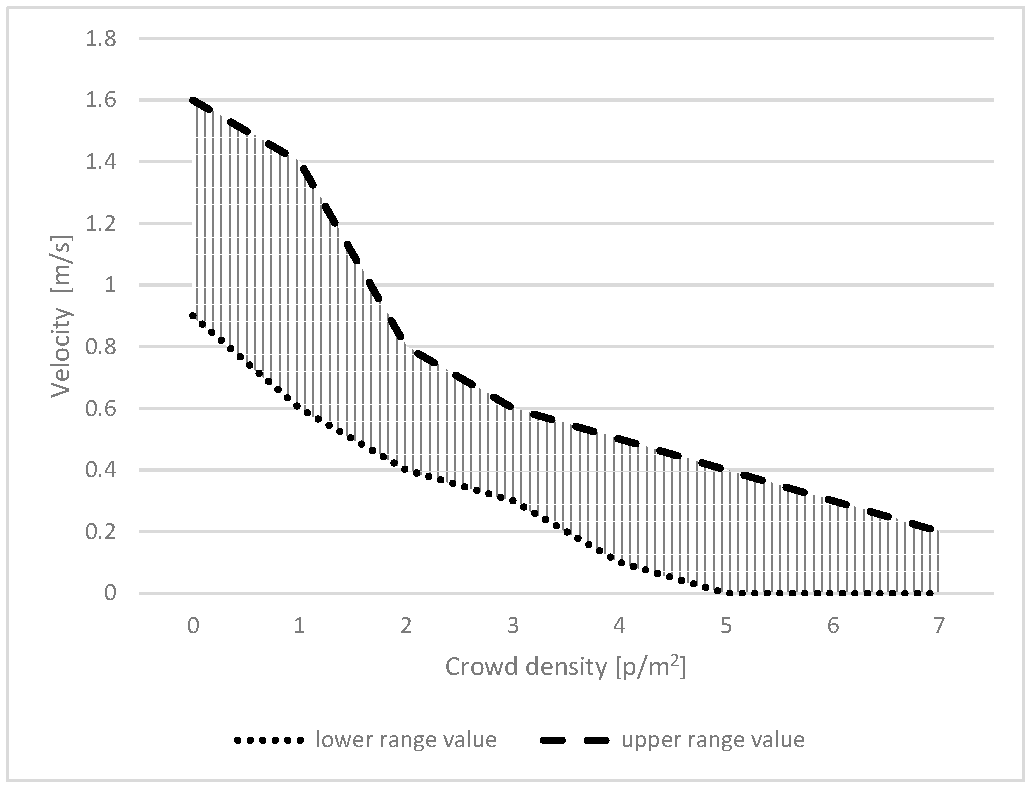

Figure 1 provides an overview of empirical studies on this relationship [

24,

25,

26,

27], illustrating the approximate range of values (indicated by the hatched area).

As shown in

Figure 1, movement velocity (

[m/s]) decreases as crowd density (

[p/m

2]), measured in people per square metre, increases. The differences observed across studies can be attributed to varying conditions and methodologies, which is to be expected. Additional research on this topic is available in the literature [

28], though the principal assumptions and relationships outlined in 1995 remain both valid and widely utilised.

A detailed analysis of the relationship between evacuee movement speed and evacuation requirements leads to several key conclusions:

Operating at speeds greater than the design speed can reduce evacuation time; however, the impact of increased inhalation associated with heightened emotional states appears to be relatively minor.

A reduction in speed due to increased crowd density may negatively affect evacuation safety, as it prolongs exposure to hazardous substances for those trapped in congestion.

These adverse effects can be mitigated or even eliminated by shortening evacuation passages and access routes, as well as by equipping escape routes with effective smoke ventilation.

Figure 1.

Range of movement speed values depending on crowd density.

Figure 1.

Range of movement speed values depending on crowd density.

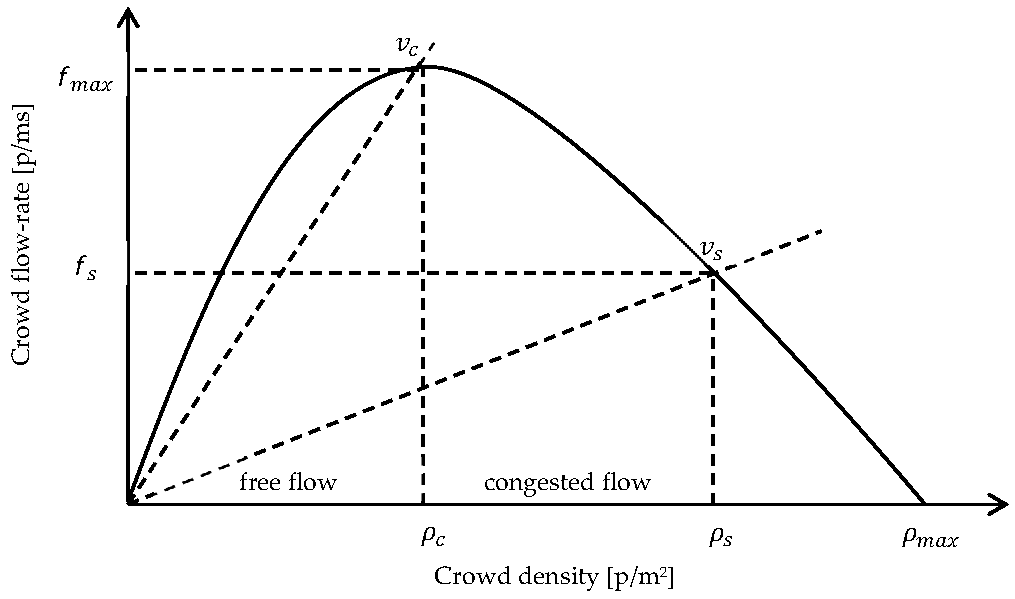

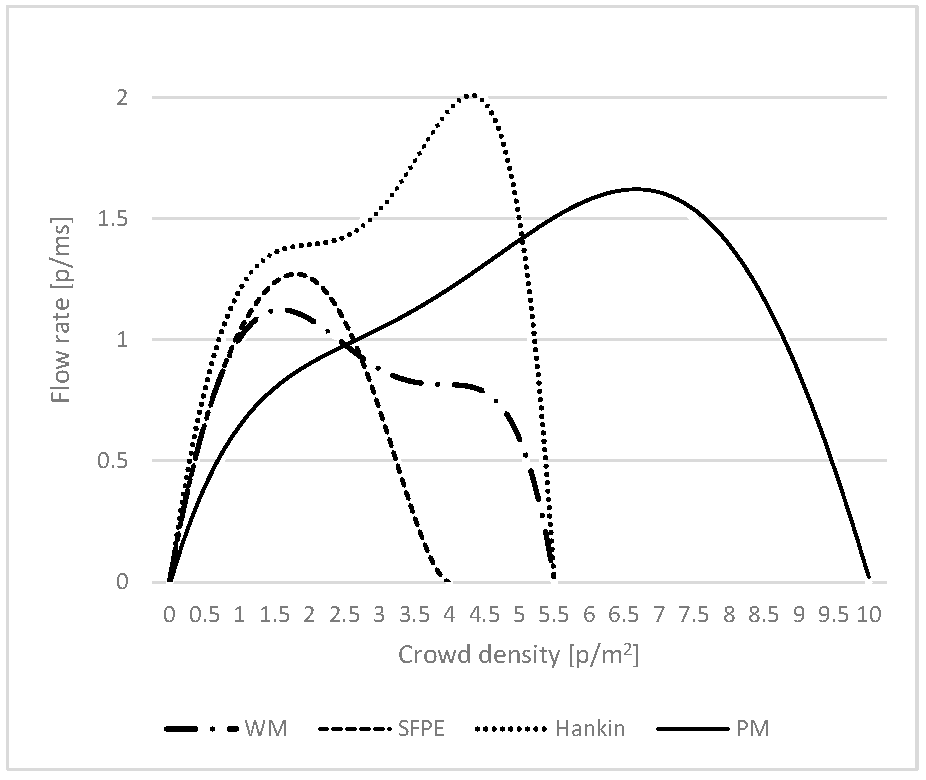

3.2. Flow Rate Is Contingent upon the Density and Velocity of the Crowd

The theoretical relationship between flow rate and crowd density has been extensively examined in the literature [

29].

Figure 2 shows the fundamental relationship between flow rate, velocity, and density. The graph’s characteristic shape is a common feature in many theoretical discussions on the subject. Here, the parameter of interest is the flow rate

[p/ms], which reaches its maximum at the critical parameters

and

. When crowd density is below the critical threshold, the flow rate increases with density, as pedestrian movement is relatively smooth. However, when density exceeds this critical level, blockages occur, causing both flow rate and velocity to decline. The safe density

is defined as the point at which the crowd congregates but maintains a slow flow, while the maximum density

represents the threshold beyond which movement ceases entirely.

Adopting precise values for each parameter remains challenging owing to considerable variations between different data sources. For example, according to the Green Guide [

31],

is 4 p/m

2 and

is 7.4 p/m

2; Chen et al. [

32] report

as 3.57 p/m

2 and

as 8 p/m

2; meanwhile, CFPA-E [

33] provides

as 1.9 p/m

2 (with

not specified) and

as 3.8 p/m

2. These variations suggest that parameter values depend on specific boundary conditions and should be selected on a case-by-case basis.

A comprehensive review of both the literature and empirical data on the relationship between crowd density and flow rate is available [

34].

Figure 3 presents several approximations of this relationship, illustrating models such as WM [

35], SFPE [

36], Hankin [

27], and PM [

25].

The studies indicate that the reduced throughput caused by high crowd density significantly increases the time required to navigate bottlenecks. Consequently, implementing appropriate evacuation measures can mitigate these risks, as follows:

Increasing the width of emergency exits: This reduces pressure along the exit axis and facilitates a more efficient flow.

Increasing the number of emergency exits: This distributes the flow of evacuees, thereby reducing the likelihood of congestion.

Shortening evacuation passages: This decreases the time needed to leave a room, thus limiting exposure to hazardous substances.

Equipping escape routes with smoke ventilation: This effectively removes dangerous substances from the environment.

Installing a voice alarm system: Such systems are recommended as they can help maintain calm and guide evacuations in the correct direction.

Two predictions, which require further empirical validation, are as follows:

Under free-flow conditions: The relationship between exit width and flow rate may be non-linear, exhibiting a stepwise improvement as the exit width increases to accommodate successive individuals side by side. This phenomenon, often referred to as the “zipper effect” [

34], merits further investigation.

Under congested conditions: The relationship between exit width and flow rate may also be non-linear owing to the highest crowd pressure being exerted at the edges of the exit [

37]. With a sufficiently wide exit, the pressure at the centre may not be enough to significantly impede flow.

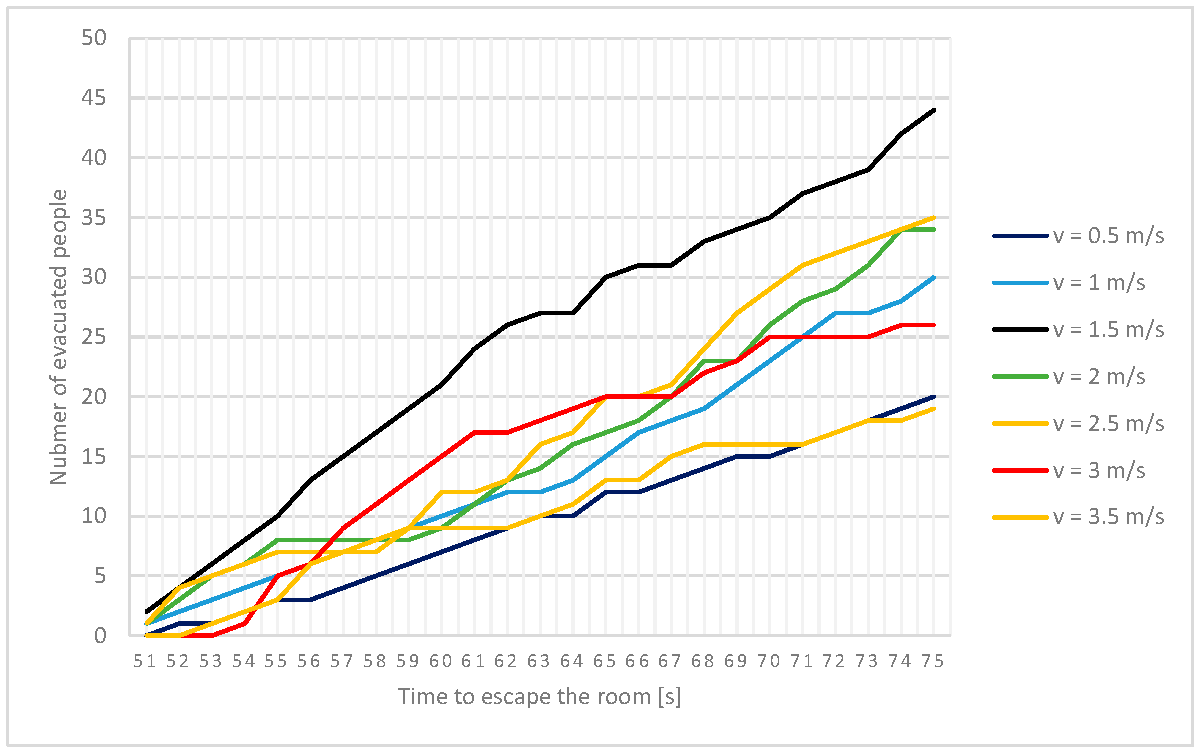

3.3. Congestion Prevents Coordinated Evacuation

As illustrated in

Figure 4 and detailed in

Table 1, the temporal dynamics of egress from a reference room (15 × 15 m, with a 1 m wide door) depend on the velocity at which individuals move [

8].

Two significant observations can be drawn from the graph and table. Firstly, during the 51–75 s test period, the maximum number of individuals (44) evacuated at a velocity of 1.5 m/s. Comparable outcomes were observed in the other scenarios: 35 people at 2.5 m/s, 34 at 2 m/s, 30 at 1 m/s, and 26 at 3 m/s. The poorest performance was recorded at speeds of 3.5 m/s (19 people) and 0.5 m/s (20 people). For the purpose of analysing escape evacuation, it is crucial to understand how congestion forms in relation to speed—congestion is represented by horizontal lines in the graph and shaded cells in the table.

The data indicate that the greatest congestion occurred at the highest speeds—3.5 m/s resulted in six congestion episodes (three of which lasted ≥2 s), while 3 m/s produced five episodes (three long). In contrast, no congestion was observed at a speed of 0.5 m/s; the gaps (or “0” values) in the table reflect an insufficient density of people to sustain a continuous flow. Notably, significant congestion was not observed until speeds of 2 m/s and 2.5 m/s, and these instances were isolated. Notably, the room (225 m2) had only a single 1 m wide emergency exit; it is hypothesised that a wider or more numerous exit configuration would accentuate the effects of accelerated movement.

A fundamental question arising from these surveys is whether the number of individuals evacuated is the sole pertinent metric when assessing effectiveness of evacuation, whether analyse also congestions. Ultimately, the primary concern is to determine whether it is feasible to evacuate all occupants within the designated timeframe. It is also crucial to recognise that congestion can lead to injuries due to increased pressure, which may significantly reduce the effective width of the available passage.

The above observations are likely most relevant to situations involving a relatively high crowd density (i.e., a density near the emergency exit exceeding 2 p/m

2).

Figure 5 presents CCTV footage capturing the onset of panic in a gymnasium with a low overall density (only 19 people in the entire room). This footage was recorded in North Carolina in January 2020 during a storm that caused damage to the building’s wall and part of its roof. While a single recording cannot yield definitive conclusions, it provides a valuable starting point for further analysis, given the intuitive nature of the observations. It is hypothesised that the optimal walking speed exceeds the comfortable pace until the critical crowd density is reached and emergency exits are sufficiently numerous and spacious. However, the precise relationship between these parameters remains to be conclusively demonstrated. Detailed analysis of the video frames reveals that subjects were moving at an average speed of approximately 3.5 m/s, as evidenced by an individual in a white sweatshirt covering approximately 7 m in roughly 2 s. Notably, this movement did not result in congestion, and the subjects quickly vacated the potentially hazardous area.

The primary focus of this article and the numerous studies it references is congestion. This issue poses a significant research challenge because, depending on the event, heightened emotions during evacuation (e.g., a crowd stampede) can trigger congestion, and congestion, in turn, can exacerbate emotional distress. These two phenomena may even reinforce one another. Nevertheless, several evacuation measures have been shown to reduce the likelihood of congestion:

Increasing the width of emergency exits: This reduces pressure along the exit axis, addressing one of the root causes of congestion.

Reducing the length of evacuation passages: Shorter passages decrease the time required to leave the room, thus mitigating the adverse effects of congestion.

Implementing smoke ventilation: This measure can remove hazardous substances from the environment, alleviating the negative impact of congestion.

Installing a voice alarm system: When properly programmed and designed, such systems have the potential to calm emotions, thereby reducing the likelihood of congestion.

3.4. In a State of Panic, People Are Prone to Following the Crowd

Analyses of real-life events have demonstrated that individuals are more likely to follow the crowd when in a state of panic [

19].

Figure 6a shows the number of people evacuating through the two emergency exits following the earthquake at Chengdu Airport in China. Although the observed disparity in the graph is greater than would be expected under normal circumstances, this is largely because of staff directing people to exit 1 at one point. Even after this directive was withdrawn, most individuals continued to use exit 1, even as it began to congest, while exit 2 remained relatively unoccupied (see

Figure 6).

A similar phenomenon has been observed in ants [

38]. Under conditions of panic, ants showed a pronounced preference for one exit, with the ratio of ants choosing the left over the right exit at 38.3%. In contrast, in non-panic situations, the distribution of exit choices was considerably more even, with a ratio of just 12.4%.

Research has indicated that, in non-panic situations, individuals do not invariably proceed towards the nearest exit. Instead, the decision to evacuate is made on an individual basis, influenced by factors such as personal capabilities, the distance to the exit, crowd density, and psychological considerations [

39]. However, once panic ensues, a clear pattern emerges: individuals are less inclined to alter their chosen path and are more likely to follow well-established routes, often those they used when entering the building. Furthermore, as people draw closer together and exhibit crowd-like behaviour, a phenomenon known as “herding” [

40] becomes apparent, diminishing their individual sense of comfort.

Similar to the formation of traffic jams, the herd mentality in panic evacuations can both cause and result from congestion. A complete absence of individual decision-making is not conducive to a safe evacuation, and it is recommended that such behaviour be discouraged. By encouraging evacuees to make rational decisions about their escape routes—rather than simply following the crowd—the risk of congestion can be mitigated. Measures such as wider or additional emergency exits and the installation of a voice alarm system within the building can promote more rational decision-making, thereby ensuring a safer and more orderly evacuation process.

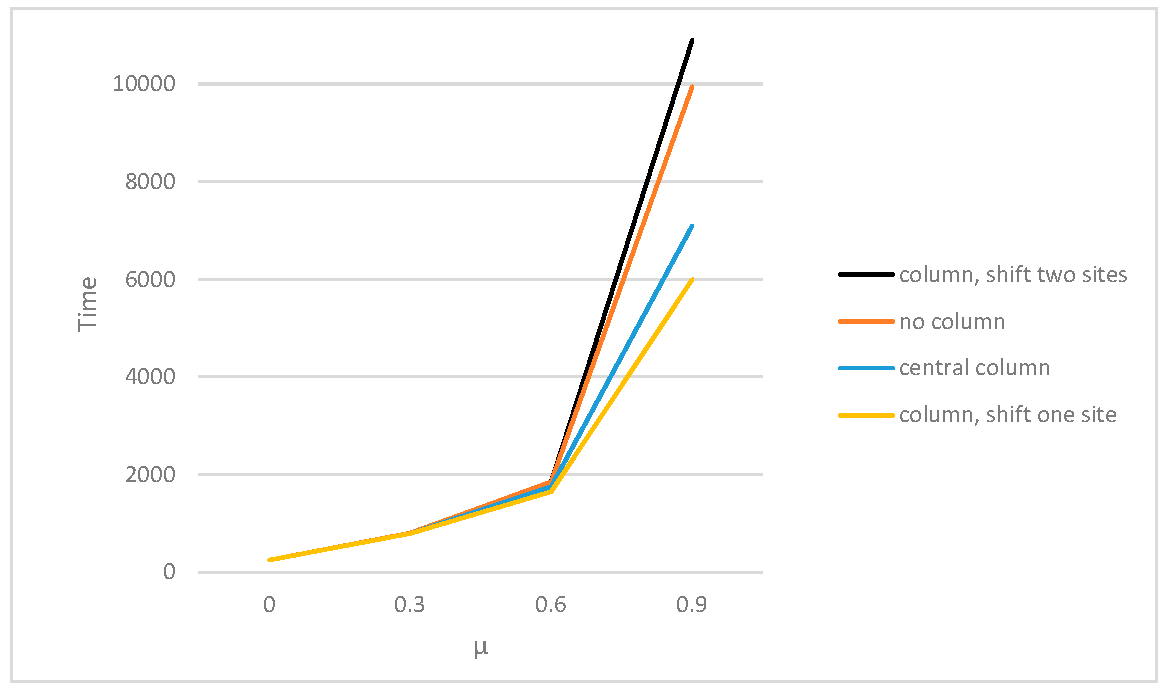

3.5. Optimal Evacuation Does Not Invariably Occur at a Comfortable Speed

Helbing et al. [

8] demonstrated in their seminal work that the shortest evacuation times are achieved under conditions of “incomplete” panic. As shown in

Figure 7, the effectiveness of an evacuation depends on the panic parameter,

, which represents the ratio of instances of individual decision-making to instances of herding behaviour. Each individual

can choose a direction of movement,

, either independently or by following the average direction of their neighbours,

(where

represents neighbours). It is hypothesised that these two influences are weighted by the panic parameter

, as expressed in the following equation:

This relationship indicates that at low values of , individual behaviour predominates, while at high values, herding behaviour becomes dominant.

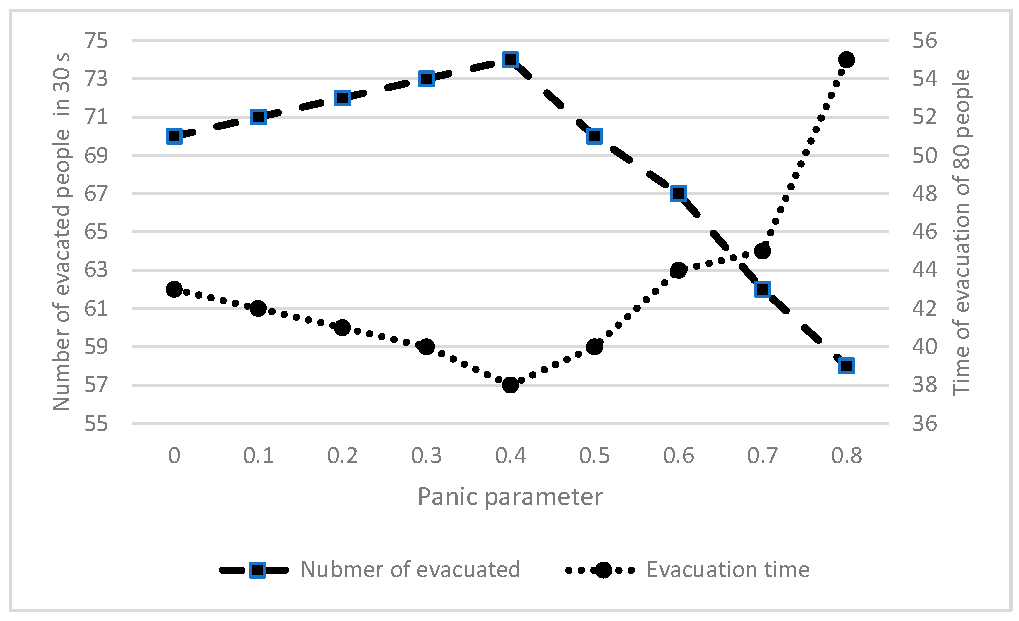

Figure 7.

Number of people evacuated and time to evacuate a smoky room as a function of the panic parameter.

Figure 7.

Number of people evacuated and time to evacuate a smoky room as a function of the panic parameter.

Figure 7 shows the evacuation process of 80 individuals from a reference smoky room (15 × 15 m) equipped with two invisible exits, each 1.5 m wide. The figure shows evacuation times under various scenarios that simulate both individual and herding behaviours. The analysis by Helbing et al. [

8] reveals that the most efficient evacuation occurs when

= 0.4, indicating an almost equal mix of individual and herding behaviour. This finding is in line with experimental studies [

41], which show that while collective behaviours often outperform isolated individual actions, they may be less effective at generating novel solutions to complex challenges.

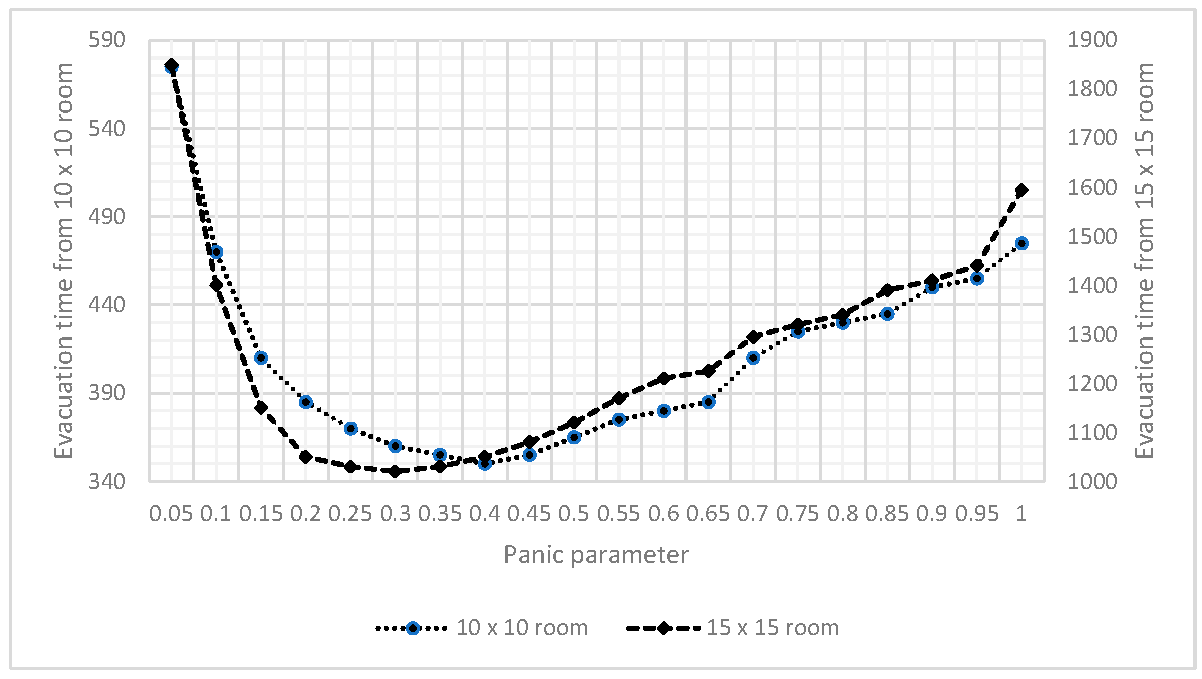

Similar observations were reported by Shen et al. [

42], who analysed the optimal values of the panic parameter for rooms of different sizes. Their results, shown in

Figure 8, indicate that optimal values range from 0.3 to 0.4, with a marginally lower optimal panic parameter observed for larger rooms compared to smaller ones.

In our earlier analysis (

Section 3.3,

Figure 4), we noted that increased velocity did not adversely affect the number of evacuees at low crowd densities. A further observation, pertinent to the current discussion, is that a moderate degree of panic improves evacuation efficiency. This enhancement results from faster movement as well as the distinctive characteristics of herding behaviour.

Figure 8.

Relationship between evacuation time and floor area for two rooms of different sizes.

Figure 8.

Relationship between evacuation time and floor area for two rooms of different sizes.

As demonstrated in other studies [

43], the issue remains complex. In some cases, “semi-panic” has been found to detrimentally affect evacuation times, while in others, it has proved beneficial (see

Table 2). Notably, the concept of “incomplete panic” from the 2000 study [

8] differs from the notion of “semi-panic” described in the 2014 study [

43]. In the latter, “semi-panic” is characterised not by a specific panic parameter but by the potential for confusion and the resultant increase in movement speed among various groups, including people with and without disabilities.

Further experimental research and analysis of real events will be necessary to fully describe this principle. Nonetheless, defining incomplete evacuation in terms of the panic parameter appears to facilitate a more universal framework for understanding evacuation dynamics.

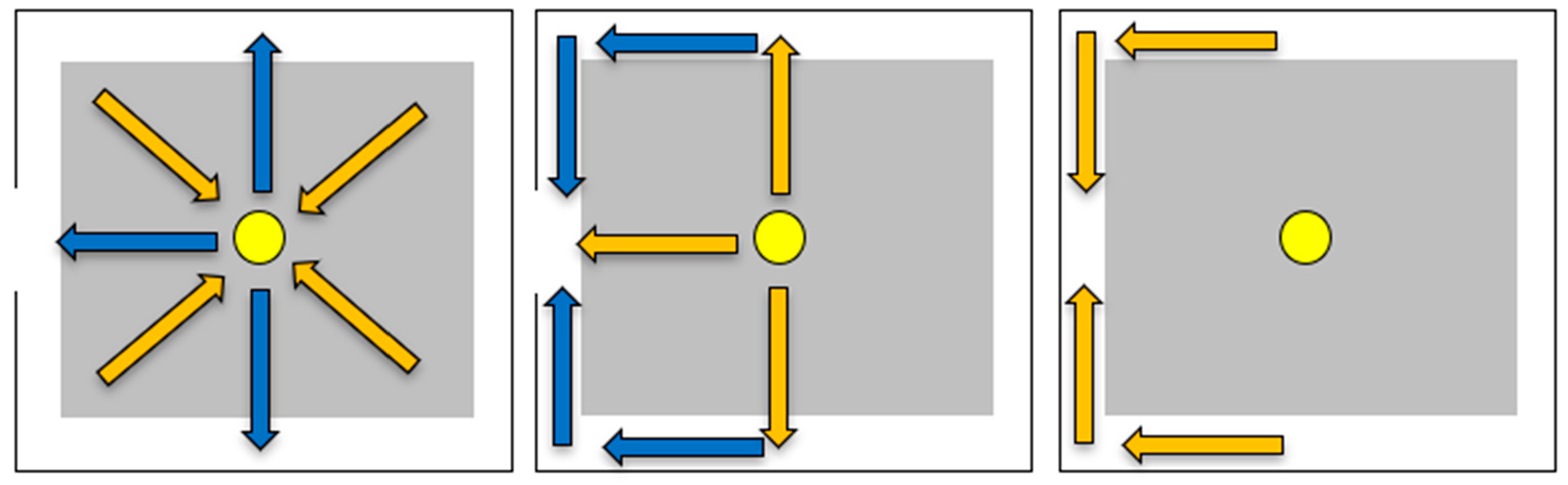

3.6. Obstacles Can Have a Positive Effect on the Evacuation Time

It is now widely acknowledged that the strategic placement of obstacles during crowd events can yield substantial benefits. A substantial body of experimental studies and simulations supports this assertion. In moderately sized crowds, the use of obstacles to compartmentalise evacuees has been shown to improve evacuation efficacy by approximately 30% [

44]. This benefit may be further enhanced in larger crowds.

Surprisingly, research has found that the most effective arrangement is an asymmetrical partition relative to the centre of symmetry of the emergency exit. This counterintuitive finding was analysed using the so-called coefficient of friction [

45]. Studies demonstrate that the shortest evacuation times are achieved when an off-centre obstacle is positioned marginally away from the exit axis. Furthermore, evacuation times are still improved when an obstacle is placed directly on the axis, compared to scenarios with no obstacle at all (see

Figure 9).

A more detailed examination of the optimal location of obstacles in relation to the exit axis reveals that the ideal placement should obstruct lateral pedestrian movement while allowing those moving perpendicularly to the wall to pass unimpeded [

46]. Furthermore, simulations [

37] indicate that both the position and the shape of an obstacle are crucial. In the simulations, the reference evacuation time was reduced from 101.1 s to 92.39 s with a column-type obstacle and to 77.95 s with a pre-wall-shaped obstacle.

From a practical perspective, it is clear that optimally placed obstacles can significantly enhance evacuation conditions by effectively widening the designated escape route. In situations where other measures, such as reducing pressure along the exit axis, are not feasible, the use of strategically positioned obstacles should be considered. Although retrofitting existing buildings with such features may be challenging, this approach is more viable for temporary settings such as exhibitions or events with unusually large numbers of participants.

The impact of obstacles on evacuation times has attracted sufficient interest to warrant optimisation of their location and shape using probabilistic distributions, a method already applied to other evacuation parameters [

47].

An additional factor to consider is the behaviour of individuals in conditions of limited visibility. Under poor visibility, evacuees are more likely to pause and maintain contact with walls or other obstacles rather than continue moving, even if in a prone position [

19]. It can be posited that if evacuees do move, they will tend to follow the walls, which may positively influence the evacuation process by providing a more directed flow.

Guo et al. [

48] demonstrated that during a panic evacuation, individuals initially congregate around a light source (typically at the centre of the room) before seeking an exit that may not be immediately visible. In contrast, in a non-panic evacuation scenario with an unchanged room layout, individuals promptly move toward the emergency exits, bypassing the illuminated central area. This evacuation sequence is shown in

Figure 10.

4. Conclusions

The characteristics of panic behaviour outlined in this article have served as a reliable theoretical foundation for understanding evacuation safety in engineering for over 25 years. Although the phenomena described do not exhaust all theoretical assumptions for modelling panic, they provide a contemporary summary of current knowledge in selected areas and clearly indicate potential directions for further research.

A thorough analysis of the characteristics of stampedes and the less intuitive aspects of crowd movement under emotional influence raises a challenging question: Is panic itself (a psychological factor) the primary issue, or are the physical bottlenecks in escape routes, particularly in narrow areas, the root cause? It can be argued that adverse reactions during panic increase the likelihood of congestion, and in turn, congestion intensifies these adverse reactions, creating a positive feedback loop in which each condition exacerbates the other.

The existing literature provides a solid basis for implementing measures that enhance the safety of large groups evacuating from confined spaces. The analysis suggests that several phenomena are associated with panic evacuation, highlighting significant potential for further research. This includes optimising evacuation times at speeds higher than those considered comfortable and determining the probabilistic distribution of optimal obstacle locations to prevent critical congestion. Other, yet to be fully explored, observations suggest that increasing the minimum required widths of emergency exits, potentially at the expense of the number of exits, could reduce the risk of crowd stampedes. The author posits that these findings not only inform the development of evacuation procedures by experts in the field but also support the case for legislative changes in this domain.

As detailed in

Table 3, the paper presents an in-depth analysis of the phenomena that accompany a crowd stampede during a panic evacuation. The study proposes to indicate the impact of these phenomena on various technical and construction requirements for evacuation.

Table 3 presents several hypotheses that can be regarded as both expert and intuitive. However, further research is needed to clarify these propositions and determine the interdependencies between the individual requirements. In this table, the designation “C” refers to measures that address the causes of the phenomenon, while “E” indicates measures that minimise its negative effects. It is important to note that these assignments reflect the author’s subjective evaluation, which must be validated through additional research.

The author’s future research will focus on real-life experiments and computer simulations to achieve a deeper understanding of the described phenomena and their interactions. A key question remains: Is it possible to recreate the panic of a stampede in an experimental setting, and if so, is it ethical? Any real-life experiments must be designed with utmost care, particularly with regard to the emotional states of the participants. Moreover, further clarification is needed on the actual movement speed of crowds, flow rates, and other physical parameters, especially concerning their dependence on local conditions and anthropogenic factors.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new research data has been created.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mintz, A. Non-adaptive group behavior. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1951, 46, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarantelli, E.L. The nature and conditions of panic. Am. J. Sociol. 1954, 60, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janis, I.L.; Mann, L. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Canter, D.; Breaux, J.; Sime, J.D. Domestic multiple occupancy and hospital fires. In Fires and Human Behaviour; Canter, D., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1980; pp. 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, D.; Canter, D. The decision to evacuate: A study of the motivations which contribute to evacuation in the event of fire. Fire Saf. J. 1985, 9, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebihara, M.; Ohtsuki, A.; Iwaki, H. A model for simulating human behavior during emergency evacuation based on classificatory reasoning and certainty value handling. Microcomput. Civ. Eng. 1992, 7, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Still, G.K. New computer system can predict human behaviour response to building fires. Fire 1993, 84, 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Helbing, D.; Farkas, I.; Vicsek, T. Simulating dynamic features of escape panic. Nature 2000, 407, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, D.; Smith, D. Football stadia disasters in the United Kingdom: Learning from tragedy? Ind. Environ. Crisis Q. 1993, 7, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecio, M. Społeczno-ekonomiczne koszty pożarów [Socio-economic cost of fires]. BiTP 2014, 35, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation of the Minister of Infrastructure of 12 April 2002 on the Technical Conditions to Be Met by Buildings and Their Location (Pol. J. Laws/Dz.U. 2002 no. 75 Item 690, as Amended). 2002. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20020750690 (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Regulation of the Minister of Internal Affairs and Administration of 7 June 2010 on Fire Protection of Buildings, Other Buildings and Areas (Pol. J. Laws/Dz.U. 2010 no. 109 Item 719, as Amended). 2010. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20101090719 (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Haase, K.; Kasper, M.; Koch, M.; Müller, S. A pilgrim scheduling approach to increase safety during the Hajj. Oper. Res. 2019, 67, 376–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkle, F.M.; Hsu, E.B. Ram Janki Temple: Understanding human stampedes. Lancet 2011, 377, 106–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Lin, D.; Jendryke, M.; Zuo, C.; Ding, L.; Meng, L. Geo-tagged social media data-based analytical approach for perceiving impacts of social events. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KG PSP. Procedury organizacyjno-techniczne w sprawie spełnienia wymagań w zakresie bezpieczeństwa pożarowego w inny sposób niż to określono w przepisach techniczno-budowlanych, w przypadkach wskazanych w tych przepisach, oraz stosowania rozwiązań zamiennych, zapewniających niepogorszenie warunków ochrony przeciwpożarowej, w przypadkach wskazanych w przepisach przeciwpożarowych, 2008. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/823f9cb8-928d-4292-bcf3-abb9cf4afa61 (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Pecio, M. Acceptance criteria of replacement solutions in fire protection. Sci. Rep. Fire Univ. 2023, 1, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarshar, P.; Radianti, J.; Gonzalez, J.J. Modeling panic in ship fire evacuation using dynamic Bayesian network. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Innovative Computing Technology (INTECH), London, UK, 29–31 August 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y. Difference between real-life escape panic and mimic exercises in simulated situation with implications to the statistical physics models of emergency evacuation: The 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Physical A 2011, 390, 2375–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, G.; Lovreglio, R.; Quagliarini, E. Proposing behavior-oriented strategies for earthquake emergency evacuation: A behavioral data analysis from New Zealand, Italy and Japan. Saf. Sci. 2019, 116, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, A.; Helbing, D.; A-Abideen, H.Z.; Al-Bosta, S. From crowd dynamics to crowd safety: A video-based analysis. Adv. Complex Syst. 2008, 11, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Niu, L.; Guan, H. The mechanism of crowd stampede based on case statistics through SNA method. Teh. Vjesn. 2021, 28, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.A.; Marchant, E.W. Computer and fluid modelling of evacuation. Saf. Sci. 1995, 18, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruin, J.J. Pedestrian Planning and Design; Metropolitan Association of Urban Designers and Environmental Planners: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Predtechenskii, V.M.; Milinski, A.I. Planning for Foot Traffic Flow in Buildings; Stroiizdat Publishers: Moscow, Russia, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, K.; Ota, H.; Oki, T. Forecasting the flow of people. Railw. Res. Rev. 1988, 45, 8–14. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Hankin, B.D.; Wright, R.A. Passenger flow in subways. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1958, 9, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Lo, S.M.; Lu, J.A. On the relationship between crowd density and movement velocity. Fire Saf. J. 2003, 38, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y. Dynamics-based stranded-crowd model for evacuation in building bottlenecks. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, 364791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.A.; Fang, Z.; Lu, Z.M.; Zhao, C. Mathematical model of evacuation speed for personnel in buildings. Eng. J. Wuhan Univ. 2002, 35, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Authority, F.L. Guide to Safety at Sports Grounds (Green Guide), TSO 5th ed.; Department for Culture, Media and Sport: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, P.J.; Yang, W.; Li, Q. Personnel evacuation strategy for theater based on systematic dynamics model. J. Nat. Disast. 2005, 14, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- CFPA-E, Guideline No 19:2023 F, Fire Safety Engineering Concerning Evacuation from Buildings. 2023. Available online: https://cfpa-e.eu (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Seyfried, A.; Passon, O.; Steffen, B.; Boltes, M.; Rupprecht, T.; Klingsch, W. New insights into pedestrian flow through bottlenecks. Transp. Sci. 2009, 43, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidmann, U.; der Fußgänger, T. Schriftenreihe Des IVT 90; ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, H.E.; Mowrer, F.W. Emergency movement. In SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering, 3rd ed.; DiNenno, P.J., Ed.; National Fire Protection Association: Quincy, MA, USA, 2002; Chapter 14; p. 367. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Lu, X.; Tian, L.; Yu, Z.; Huang, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, T. Optimal layout design of obstacles for panic evacuation using differential evolution. Physical A 2017, 465, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altshuler, E.; Ramos, O.; Yahaira, N.; Fernández, J.; Batista-Leyva, A.J.; Noda, C. Symmetry breaking in escaping ants. Am. Nat. 2005, 166, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstedde, C.; Klauck, K.; Schadschneider, A.; Zittartz, J. Simulation of pedestrian dynamics using a 2-dimensional cellular automaton. Physical A 2001, 295, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Q.; Yang, P.; Hu, X. Modeling and simulating for congestion pedestrian evacuation with panic. Physical A 2015, 428, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H.; Thibaut, J.W. Group problem solving. In The Handbook of Social Psychology; Lindzey, G., Aronson, E., Eds.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1969; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, L. The influence of panic on the efficiency of escape. Physical A 2018, 491, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, B. Estimating the effects of mental disorientation and physical fatigue in a semi-panic evacuation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 2379–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.; Buzna, L.; Johansson, A.; Werner, T. Self-Organized Pedestrian Crowd Dynamics: Experiments, Simulations, and Design Solutions. Transp. Sci. 2005, 39, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, A.; Nishinari, K.; Schadschneider, A. Friction effects and clogging in a cellular automaton model for pedestrian dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 67, 056122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa, D.; Kimura, A.; Tomoeda, A.; Nishi, R.; Suma, Y.; Ohtsuka, K.; Nishinari, K. Introduction of frictional and turning function for pedestrian outflow with an obstacle. Phys. Rev. E 2009, 80, 036110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasuski, A.; Kubica, P.; Pecio, M. Multisymulacje: Analiza ryzyka pożarowego [Multisimulations: Fire risk analysis]. Ochr. Przeciwpożarowa 2017, 60, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Huo, F.; Li, C.; Li, Y. An evacuation model considering the phototactic behavior of panic pedestrians under limited visual field. Physical A 2023, 615, 128602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).