1. Introduction

The rear axle, as a critical load-bearing component of passenger cars, can precipitate severe traffic accidents if it fractures during vehicle operation [

1]. The rear axle of a passenger car is subject to complex and variable loads over time due to road surface irregularities, vehicle acceleration and deceleration, steering, and braking [

2]. These loads, which vary in magnitude and direction depending on driving conditions, subject the rear axle to alternating stresses, thereby inducing fatigue damage and creating conditions conducive to crack initiation [

2,

3]. The vehicle’s own weight, along with that of passengers and cargo, is transmitted through the suspension system to the rear axle, subjecting it to vertical pressure. Impacts caused by the road surface lead to dynamic changes in the vertical load [

3]. The driving force output by the engine, transmitted through the drivetrain, generates torque in the rear axle, while braking forces acting in the opposite direction to travel induce shear and torsional stresses on the axle [

4]. Lateral forces during vehicle cornering cause bending stresses in the rear axle, particularly during high-speed turns or abrupt braking, when lateral forces may significantly increase [

1,

2]. Under the influence of these alternating loads, the microstructure within the axle material undergoes cumulative damage [

5]. In regions of stress concentration, such as at the axle shoulders, keyways, and surface defects, the movement of dislocations gradually forms microcracks, marking the initial stage of fatigue crack nucleation. As the number of load cycles increases, these microcracks gradually propagate under the influence of stress [

6]. The direction of crack propagation is typically perpendicular to the direction of maximum principal stress, and the rate of propagation is influenced by factors such as stress amplitude, material characteristics, and environmental conditions [

7]. When the crack extends to a certain extent, and the remaining load-bearing area of the rear axle is unable to sustain the applied load, a sudden fracture occurs [

5,

6,

7]. Given that the reliability of the rear axle directly affects the overall performance and safety of the vehicle, the strength, stiffness, and fatigue life of the rear axle must meet design specifications.

Automobiles may be conceptualized as complex elastic systems. When time-varying operational loads are applied to these systems, multiple vibration modes are excited [

8,

9]. The dynamic response of the system at a point sufficiently distant from the loading point manifests as a stress-time history, which differs in amplitude, phase, and frequency when compared to the load-time history [

10]. Such stress-time histories encapsulate two aspects: the effect of external loads and the dynamic response of the structure to these loads [

11]. In practical measurements, external loads are often not directly observable; rather, their effects are measured at specific points on the structure [

12,

13]. The output response functions measured at these points are collectively referred to as stress-time histories, irrespective of whether they represent stress, strain, or other physical quantities indicative of structural stress, such as torque, force, or acceleration. The measurement of the natural frequencies of critical automotive components is employed to evaluate the dynamic characteristics of the vibration system [

14]. The natural frequency refers to the first-order natural frequency, corresponding to the frequencies at which peaks occur in the frequency response curve, indicative of the natural frequencies of various modal orders. Resonance occurs when the system’s excitation frequency equals or approximates its natural frequency, leading to a maximal amplitude [

15]. The frequency distribution of dynamic alternating loads coinciding closely with the frequency distribution of the structure’s natural frequencies can cause vibration fatigue damage due to resonance. Resonance fatigue is often related to component resonance or local resonance [

16]. Dynamic load excitations frequently result in vibration coupling between localized modal responses and the loads, with damage typically occurring at regions of local resonance where strain is high and defects or stress concentrations exist, representing a combined effect of local resonance and stress concentration [

12,

14]. Therefore, when the system is subjected to external excitations, it is crucial to ascertain how close the excitation frequency is to the natural frequency of the structure to avoid resonance issues. In automotive design, it is typical to avoid resonance by ensuring a separation of 3-4Hz or 15%-20% of the natural frequency between the excitation and natural frequencies [

14,

15,

16].

This study focuses on the occurrence of fracture cracks in the rear axle during accelerated life testing in a PG for a passenger car. Measurements were taken of the strain near the crack, axle end acceleration, and vehicle speed, among other test data. Furthermore, the rear axle was subjected to bench testing under longitudinal bending conditions to measure the maximum operational stress. The fatigue damage of the rear axle during the accelerated life test, the power spectral density (PSD), and the RMS value of the acceleration signal were calculated. Vibrational modal frequency sweeps were performed on the rear axle and the car body to identify the correlation between vibration frequencies and fatigue damage. Based on these findings, the crack initiation mechanisms of the rear axle were analyzed.

2. Fatigue Damage of Structures

The fatigue refers to the localized damage process in components caused by cyclic loading [

17]. During the cycle of loading, localized plastic deformation occurs in areas of highest stress, leading to fatigue damage in components. Fatigue failure is one of the most common modes of failure, accounting for approximately 70-80% of total failure in various mechanical components [

17,

18]. Principally, fatigue fracture failure falls under the category of low-stress brittle fracture, and it is challenging to observe significant plastic deformation during fatigue since the deformation predominantly occurs at the inherent flaws of the structure [

19]. The primary methods for predicting the formation of fatigue cracks include the nominal stress method and the local stress-strain method. A major limitation of the nominal stress method is its failure to account for the plasticity at the notches, whereas the local stress-strain method reasonably considers the effects of localized plasticity and local mean stress at the notch roots [

18,

19,

20]. Although most components nominally experience cyclic elastic stress, components with notches, welds, or other stress concentrators undergo localized cyclic plastic deformation, thereby making the local stress-strain method more effective for predicting the fatigue life of components. Under random loading, each hysteresis loop formed in the material constitutes a fatigue damage unit [

21]. The rainflow counting method can process the load time history into a rainflow cycle counting matrix of amplitude-mean-cycles [

22]. With known material strain histories, using the material cyclic stress-strain curve and the rainflow counting method for local stress-strain analysis enables the determination of the number of each hysteresis loop, which lays the foundation for calculating fatigue life [

23]. The local stress-strain analysis is based on the cyclic stress-strain curve of the material, its memory characteristics, and the rainflow cycle counting method. Its purpose is to determine the number of hysteresis loops formed in the material under known load or strain histories [

22,

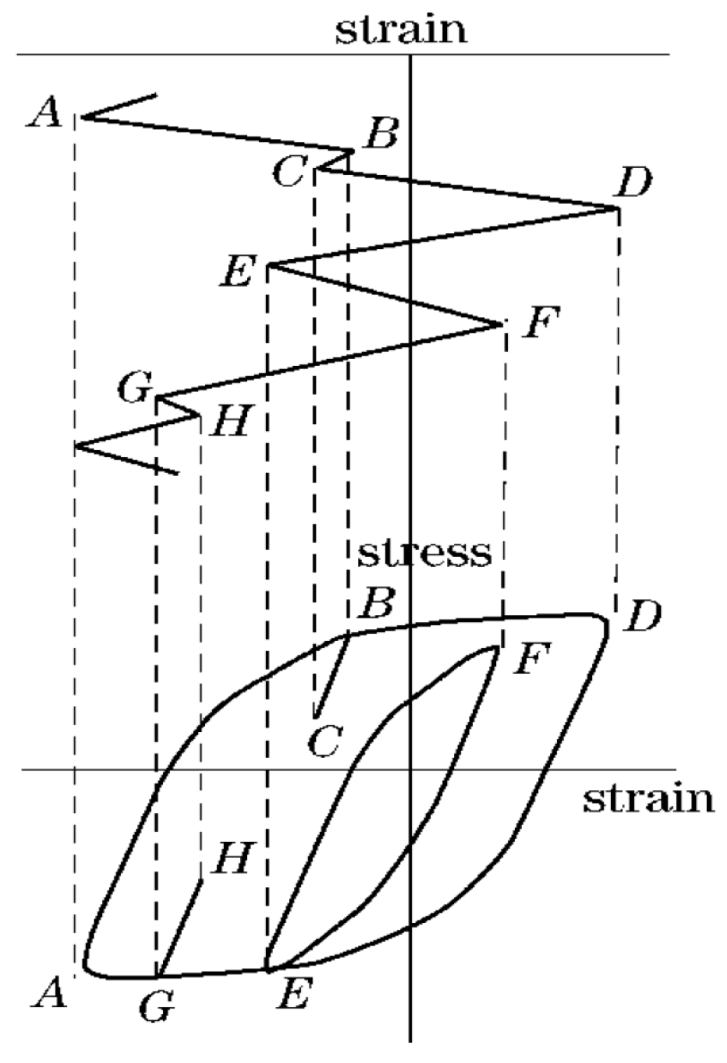

23]. The rainflow counting method is a statistical approach for fatigue analysis based on the characteristics of the material stress-strain hysteresis loops. It effectively converts complex load time histories into a series of stress amplitude-mean-cycles matrices through the rainflow cycle counting process, as illustrated in

Figure 1 [

21,

22,

23,

24]. During the cyclic loading process, the relationship between local stress and strain variations and the measured nominal stress and strain variations is depicted in

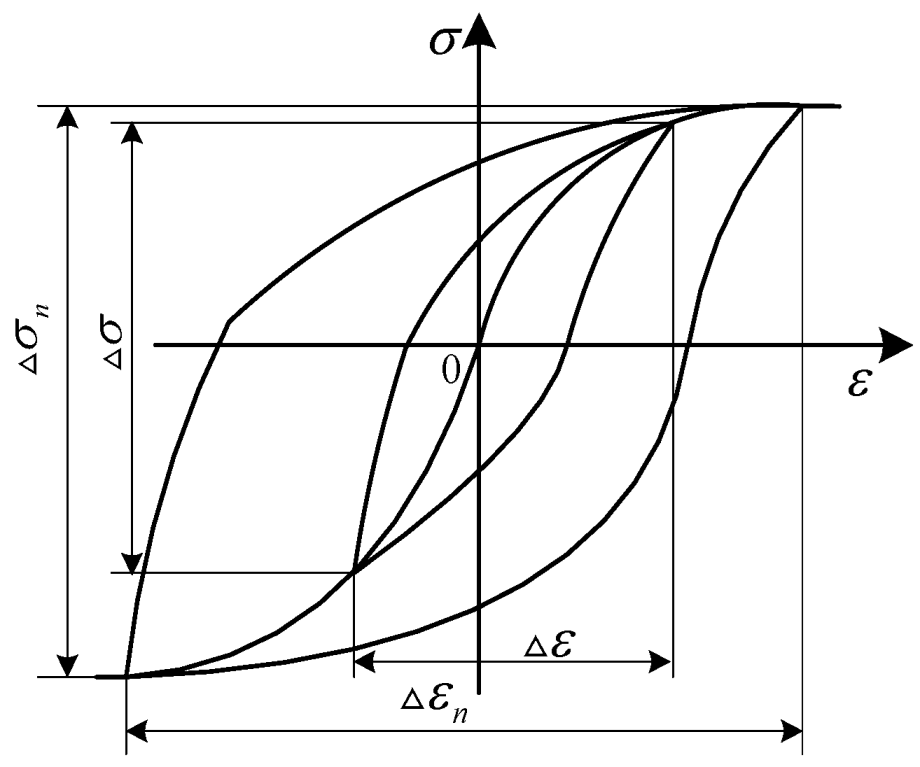

Figure 2.

Due to the difficulty of affixing strain gauges directly over the crack on the rear axle, it is only feasible to place them in proximity to the crack. In such circumstances, it becomes necessary to estimate the local stress-strain response at the crack based on the actual signals measured by the strain gauges [

25]. The Neuber’s Rule can be applied to convert the experimentally measured nominal strain spectrum into a local stress-strain response at the location of the crack, as follows:

Where

and

represent the local stress and strain amplitudes at the crack, respectively, while

and

are the nominal stress and strain amplitudes measured by the strain gauge.

denotes the fatigue notch factor, which is the ratio of the fatigue strength of a smooth specimen to that of a notched specimen.

The fatigue notch factor

can be calculated using the Neuber-Kuhn formula:

Where

is the theoretical stress concentration factor (the ratio of the maximum local elastic stress to the nominal stress),

is the radius of the fillet at the notch root, and

is a material constant related to the material’s ultimate strength and heat treatment condition.

Based on the hysteresis loop curve equation, the relationship between local stress and strain amplitudes at the position of the crack on the rear axle is given by:

Where

E is the modulus of elasticity,

is the cyclic strength coefficient, and

is the cyclic hardening exponent.

Transforming Equation (3) results in:

Introducing Equation (1) into Equation (4) yields:

By analyzing the strain time history measured by the strain gauges on the rear axle, the individual hysteresis loops and the corresponding stress and strain amplitudes at the location of the strain gauge can be determined [

26,

27]. Substituting

and

into Equation (5) to obtain

, and then substituting

into Equation (3) to obtain

, allows for calculating the local stress-strain response at the crack location of the rear axle in terms of the coordinates of the hysteresis loop vertices (

).

In the local stress-strain method, the material’s fatigue strength is represented by the strain-life curve [

6]. In a double logarithmic coordinate system, the components of the elastic strain amplitude

and plastic strain amplitude

within each hysteresis loop correlate linearly with the corresponding fatigue life, and their power law expressions can be represented as:

Where

is the fatigue strength coefficient,

is the fatigue plasticity coefficient,

is the fatigue strength exponent,

is the fatigue plasticity exponent, and

is the fatigue life for crack initiation.

The total strain amplitude is the sum of the elastic and plastic strain amplitudes, as:

The strain-life curve is typically derived from material tests conducted under symmetric cyclic strain control, where both the mean stress and mean strain are zero. However, in practical load signal processing, scenarios often arise where the mean stress and strain are not zero [

5,

6,

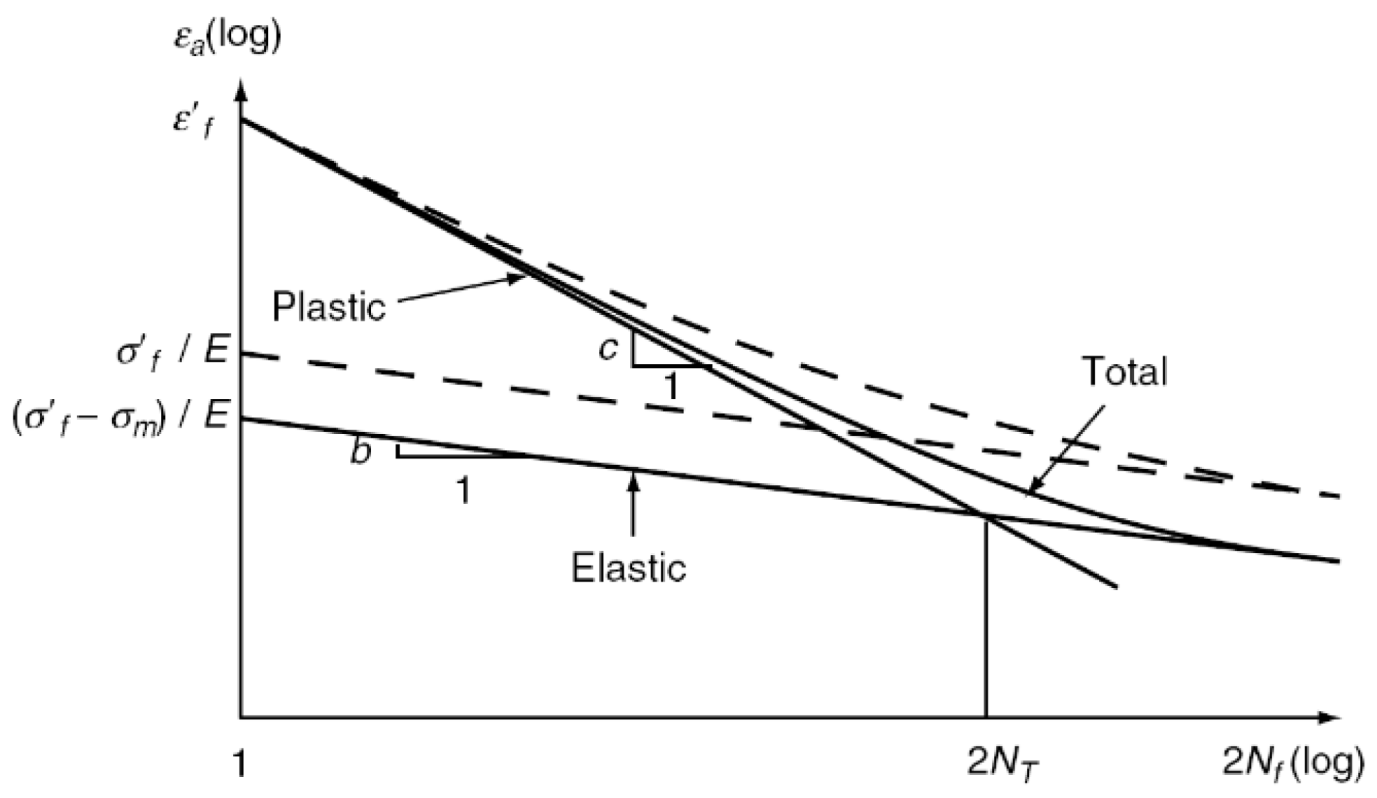

7]. While the effects of mean strain can generally be disregarded, it is necessary to correct for the impact of mean stress. Mean stress significantly influences fatigue life by altering the effective stress level within the material and the rate of crack propagation. The degree to which mean stress affects fatigue life is determined by a combination of factors including material properties, type of load, and environmental conditions. In engineering practice, it is essential to integrate correction models with experimental data to optimize design under specific operational conditions, thus ensuring the safety and reliability of engineering structures. When cyclic loading includes a mean tensile stress, the effective stress level inside the material significantly increases. This elevated stress level accelerates crack propagation, thereby substantially reducing the material’s fatigue life. As the magnitude of the mean tensile stress increases, the fatigue life of the material exhibits a marked nonlinear decline. Conversely, mean compressive stress inhibits crack propagation and effectively extends the fatigue life of the material. This is because compressive stress causes crack tips to close, significantly reducing stress concentration and delaying further crack propagation. In predicting fatigue life, accurate assessment of material performance under non-zero mean stress requires the use of correction models to equate non-zero mean stress to symmetric cyclic stress. The Morrow’s mean stress correction model is a pivotal method in addressing the effects of mean stress under asymmetric cyclic loading in fatigue life prediction. This model is widely used in engineering and focuses on modifying the strain-life relationship to reflect the cumulative effect of mean stress on material fatigue damage. The Morrow’s mean stress correction model is illustrated in

Figure 3. The Morrow’s mean stress correction equation is expressed as follows:

Where

represents the mean stress in the presence of a hysteresis loop.

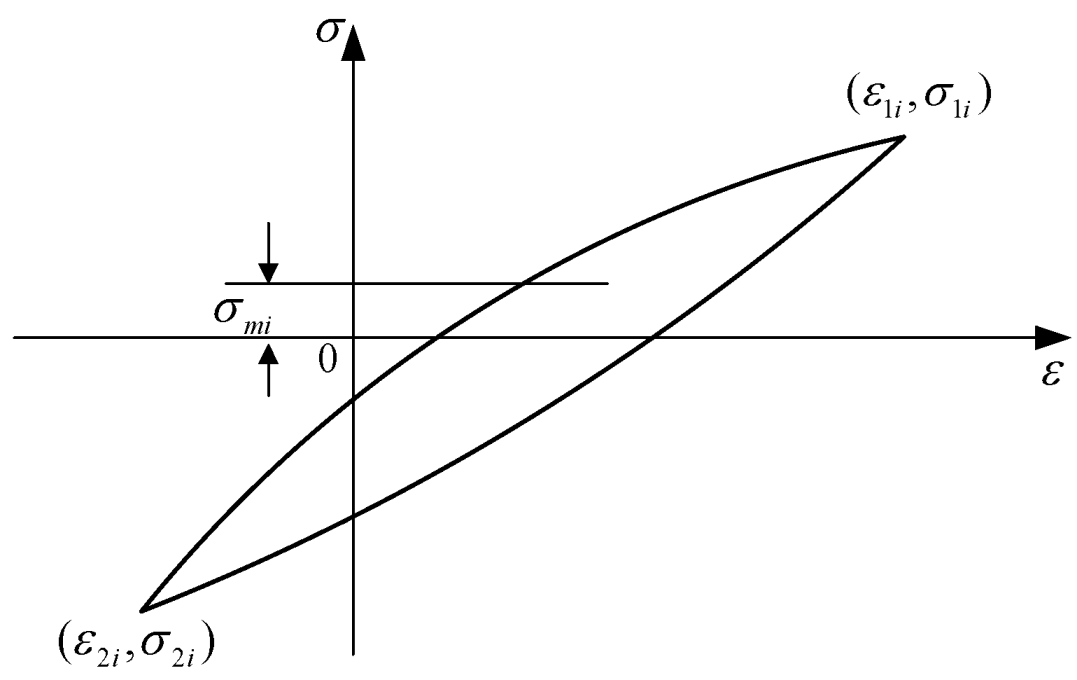

The Morrow’s equation accounts for the influence of mean stress on fatigue life and modifies the elastic component of the strain-life curve. This equation is extensively applied to steel materials. Under dynamic loading, the rear axle of a car experiences fatigue damage in each rainflow cycle [

6]. Using known strain-life curves and the number of rainflow cycles, it is possible to calculate the fatigue damage induced by each rainflow cycle. Assume that a load history generates

k rainflow cycles in the material, with the coordinates of each cycle’s two vertices represented as

and

, where

i = 1, 2, ...,

k, as shown in

Figure 4.

The mean stress

and strain range

for each rainflow cycle are given by:

By substituting Equations (10) and (11) into the Morrow’s mean stress correction Equation (9), we obtain:

From Equation (12), the crack initiation life

for each rainflow cycle

i = 1, 2, ...,

k can be calculated. Assuming that the fatigue damage caused by the

-th stress amplitude level is denoted as

, we have

Where

k is the stress amplitude level, and

is the number of rainflow cycles at the

-th amplitude level.

Using Miner’s linear cumulative damage rule, the total fatigue damage

D is accumulated from all amplitude levels:

Theoretically, when the total cumulative damage D equals 1, fatigue failure occurs in the rear axle, marked by the appearance of engineering cracks. Currently, there is no uniform standard for the length of engineering cracks, which typically range from 0.1 to 2 mm.

The suspension system of the test car features a MacPherson strut-type independent front suspension. The rear suspension is a longitudinal trailing arm-type semi-independent suspension, consisting of a torsion bar and a U-shaped shell surrounding the torsion bar, connected to the lateral bent arms. Each bent arm attaches to the car frame at one end and to the wheel at the other, with the U-shaped shell and torsion bar situated in the middle of the bent arm. As the left and right wheels move vertically, the rear axle absorbs some of the vibrations, maintaining a degree of body balance and achieving vehicle stability. The material used for the rear axle is 45 steel plate, with a fabricated structure, a yield strength of 355 MPa, and a tensile strength of 600 MPa. Material-related parameters used in the damage calculations are provided in

Table 1.

3. Analysis of Vibration Modes

3.1. Determination of Modal Parameters

The modal characteristics are inherent vibratory properties of a structural system [

8,

9]. In the case of linear vibrational systems, there exist characteristic inherent vibrational modes, and the response of the system is a linear combination of these modes. The free vibration of a linear system can be decomposed into several orthogonal single-degree-of-freedom vibrational systems, which manifest as vibrational patterns at different frequencies [

10]. Each mode corresponds to a specific set of natural frequencies, damping ratios, and mode shapes. The natural frequency is the frequency of vibration in that mode, the damping ratio describes the characteristics of vibrational energy dissipation, and the mode shape represents the spatial distribution of vibrational displacement. These modal parameters can be obtained through computational or experimental analysis [

11,

12,

13]. The objective of modal analysis is to identify the modal parameters of the system, providing a basis for the analysis of structural system vibrational characteristics, and for the prediction and diagnosis of vibrational faults. Modal analysis is based on the theory of vibration. Initially, a physical parameter model of the structure is established, which is a vibrational differential equation concerning displacement, characterized by mass, damping, and stiffness parameters. Subsequently, the characteristic value problem is studied to obtain eigenvalues and eigenvectors, leading to the determination of modal model parameters, such as modal frequencies, modal vectors, modal damping ratios, modal mass, and modal stiffness [

14,

15]. By measuring the system’s transfer function, information such as the system’s frequency response and damping ratio can be obtained, thereby facilitating an understanding of the system’s vibrational characteristics and stability [

15,

16,

17]. This knowledge is crucial for the design and optimization of various dynamic systems. The transfer function is used to describe the system’s response to input signals or the system’s frequency response [

13,

14]. It is derived using the Laplace transform, which is suitable for describing the dynamic characteristics of a system–specifically, how the system responds to time-varying inputs. For linear time-invariant systems, the relationship between input

x(

t) and output

y(

t) can be described by a constant-coefficient linear differential equation:

Where

an,

an-1, …,

a0 and

bm,

bm-1, …,

b0 are the physical parameters of the system.

For linear time-invariant systems, assuming initial conditions are zero, applying the Laplace transform to both sides of the differential equation yields:

Consequently, the transfer function

H(

s) of the system is

Where s is the complex frequency variable, and the power n of the denominator s indicates the order of the transfer function.

By conducting a frequency domain analysis of the transfer function, the system’s response to specific frequency input signals can be determined.

Substituting

into Equation (18) results in the frequency response function (FRF):

Where

is the imaginary unit, with

,

represents the angular frequency,

is the system’s FRF,

,

.

Therefore, the FRF is a representation of the transfer function in the frequency domain, quantifying the system’s output Fourier transform relative to its input Fourier transform. The Fourier transform facilitates the conversion of time-domain signals into frequency-domain signals, which is utilized to analyze the system’s frequency domain characteristics. The FRF is an inherent property of the system, related to the system’s own characteristics and independent of external factors such as excitation and response. Any complex high-order vibrational system consists of a combination of first-order and second-order systems connected in series, parallel, or through feedback. A typical second-order system transfer function is:

In this equation, m denotes the system’s mass, c the viscous damping, and k the system stiffness. Define , where is the natural frequency of the undamped system, and is the critical damping value; is the damping ratio, calculated as .

The relationship between amplitude and frequency for a second-order vibrational system is described by:

At , the system experiences resonance, where the amplitude-frequency characteristic peaks, and the amplitude reaches its maximum. The characteristics of the resonance amplitude not only form the basis for efficient energy transfer but also represent a potential risk source.

The dynamic response

y(

t) of a multi-degree-of-freedom vibrational system can be decomposed into a linear combination of various order vibrational modes, indicating that the system’s vibration comprises a superposition of multiple order natural frequencies and mode shapes.

Where

represents the mode shape of the

ith order;

and

are the amplitude and phase angle of the corresponding mode;

is the frequency of the

ith order mode.

During modal analysis of a multi-degree-of-freedom vibrational system, by solving the characteristic value equation, one can precisely determine the system’s natural frequencies and mode shapes. The relationship among the modal parameters is described by

Where

K is the system’s stiffness matrix, and

M is the mass matrix.

Increasing stiffness leads to a higher resonance frequency and reduces the amplitude of the FRF at lower frequencies. Adding damping slightly decreases the resonance frequency, but its primary effect is to reduce the amplitude at the resonance point and smooth the phase change. Increasing mass decreases the resonance frequency and also lowers the amplitude of the FRF at higher frequencies.

3.2. Estimation of Modal Parameters

The central aspect of frequency-domain modal testing involves the measurement of the FRF and curve fitting of the measured data. To measure a system’s FRF, it is essential to record both the input (excitation signal) and output (response signal) of the system. By fitting experimental data to the response function, a series of modal parameters can be extracted, including natural frequencies, damping ratios, and mode shapes. This method of extracting parameters through experimental modal analysis is highly accurate in practical engineering applications. The most common form of experimental modal analysis is the rational fraction polynomial form, which clearly depicts the poles and their conjugates. The estimation of point-to-point FRF involves applying an excitation at point

j in the system and measuring the response at point

i. For a specific

i-

j (input-output) configuration, the FRF is an estimation of the transfer function along the

axis, defined as follows

In this equation,

Hij(

jω) is the FRF between response degree of freedom

i and reference degree of freedom

j;

N is the number of vibrational modes contributing to the dynamic response of the structure within the considered frequency range;

rijk is the residue of mode k;

λk is the pole of mode k; and * denotes complex conjugate.

The poles λ

k in Equation (24) can be expressed as

Or

Where

is the damped natural frequency of mode

k,

is the undamped natural frequency of mode

k,

is the damping factor for mode

k, and

ζk is the damping ratio for mode

k.

Parameter estimation involves adjusting the parameters in the model so that the model’s predicted data matches the measured data, thereby accomplishing the identification of modal parameters. The measurement of the test signal’s FRF is carried out using a spectrum analyzer, and the estimated modal parameters are determined through curve fitting using modal analysis software. Once the modal parameters are estimated, the vibration characteristics of the structure can be described through the mode shapes.

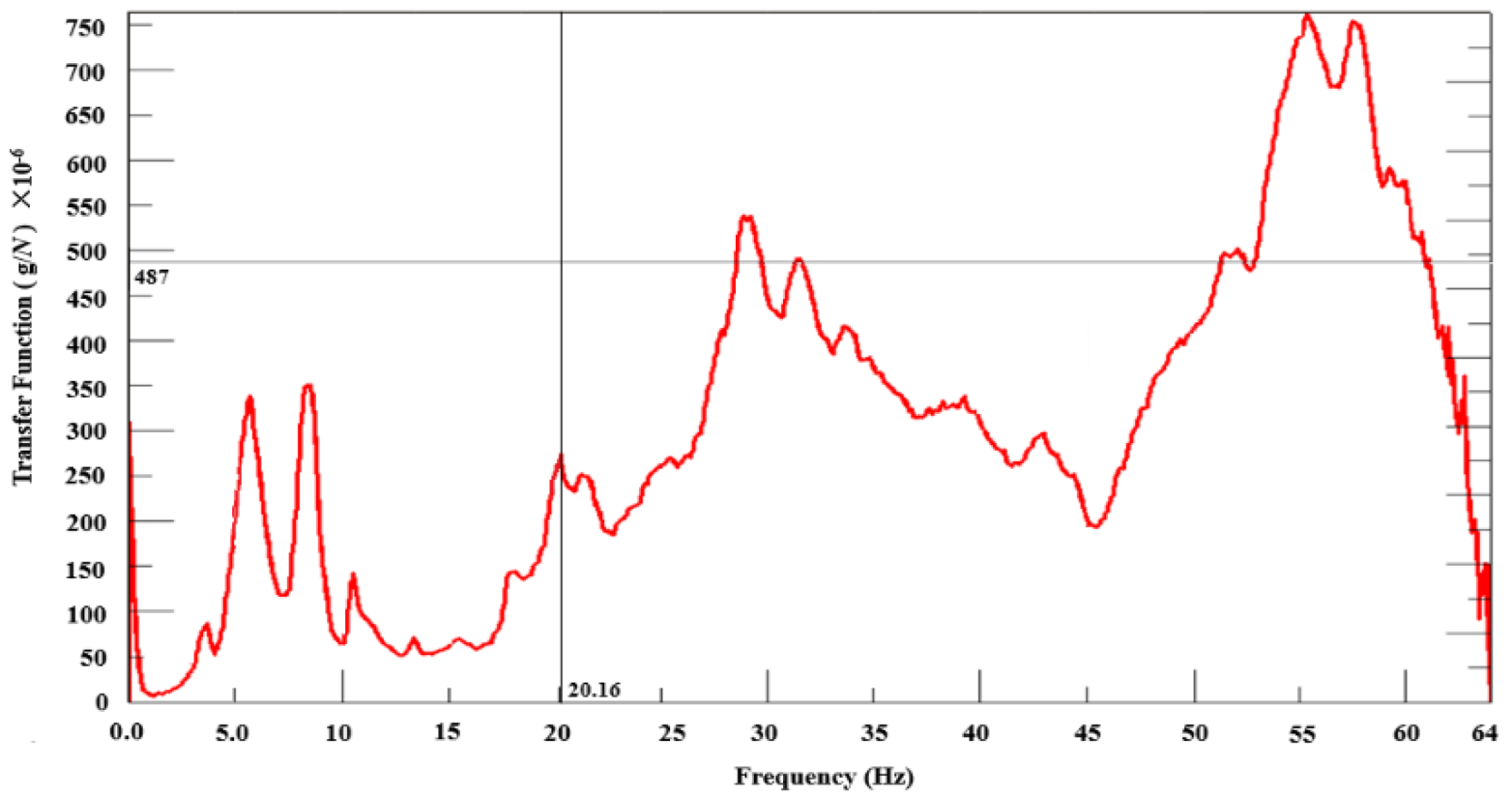

3.2. Frequency Sweeping of Vibrational Mode

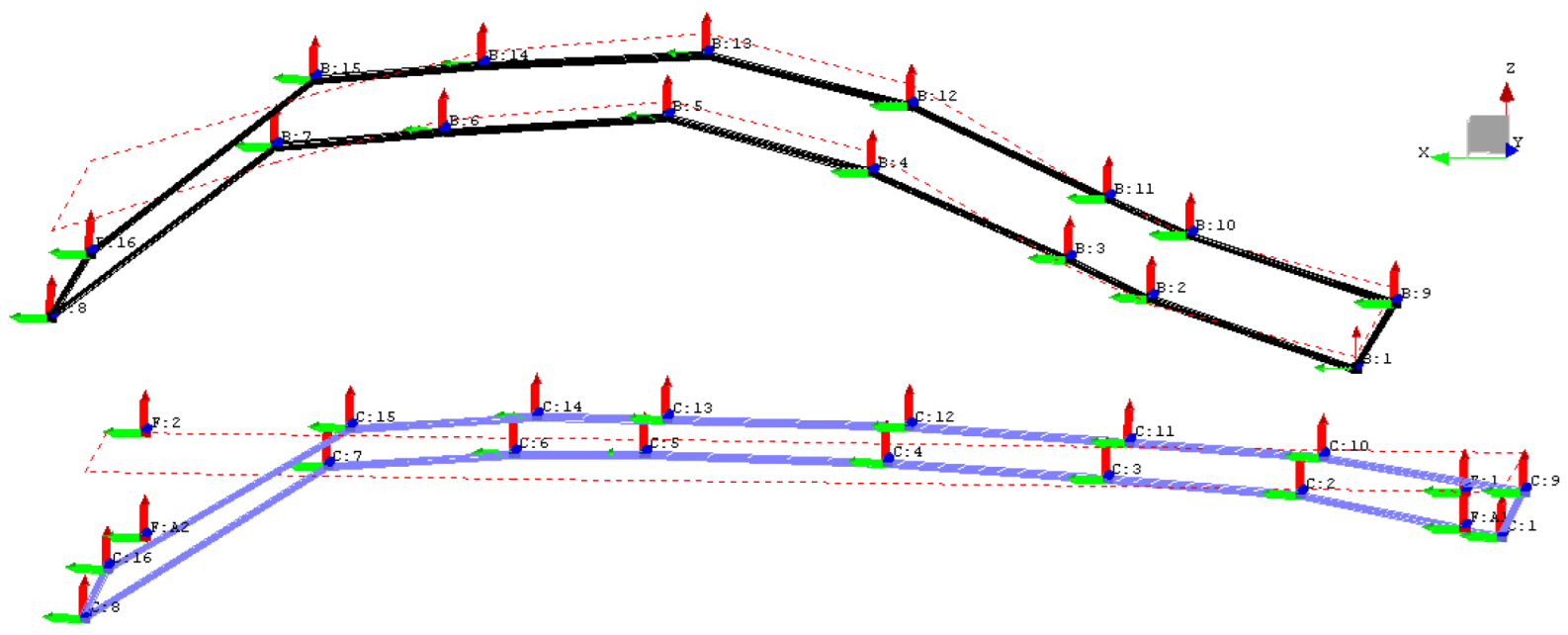

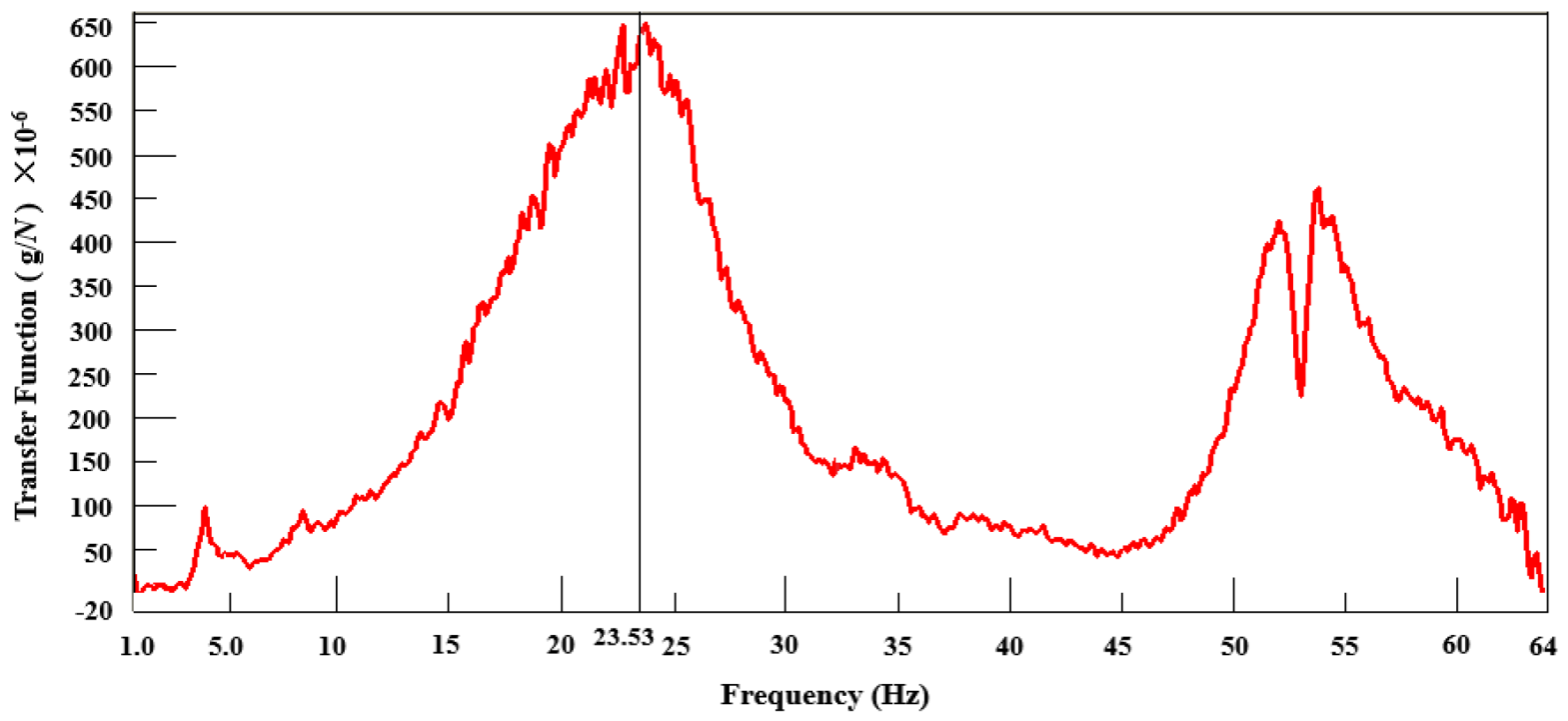

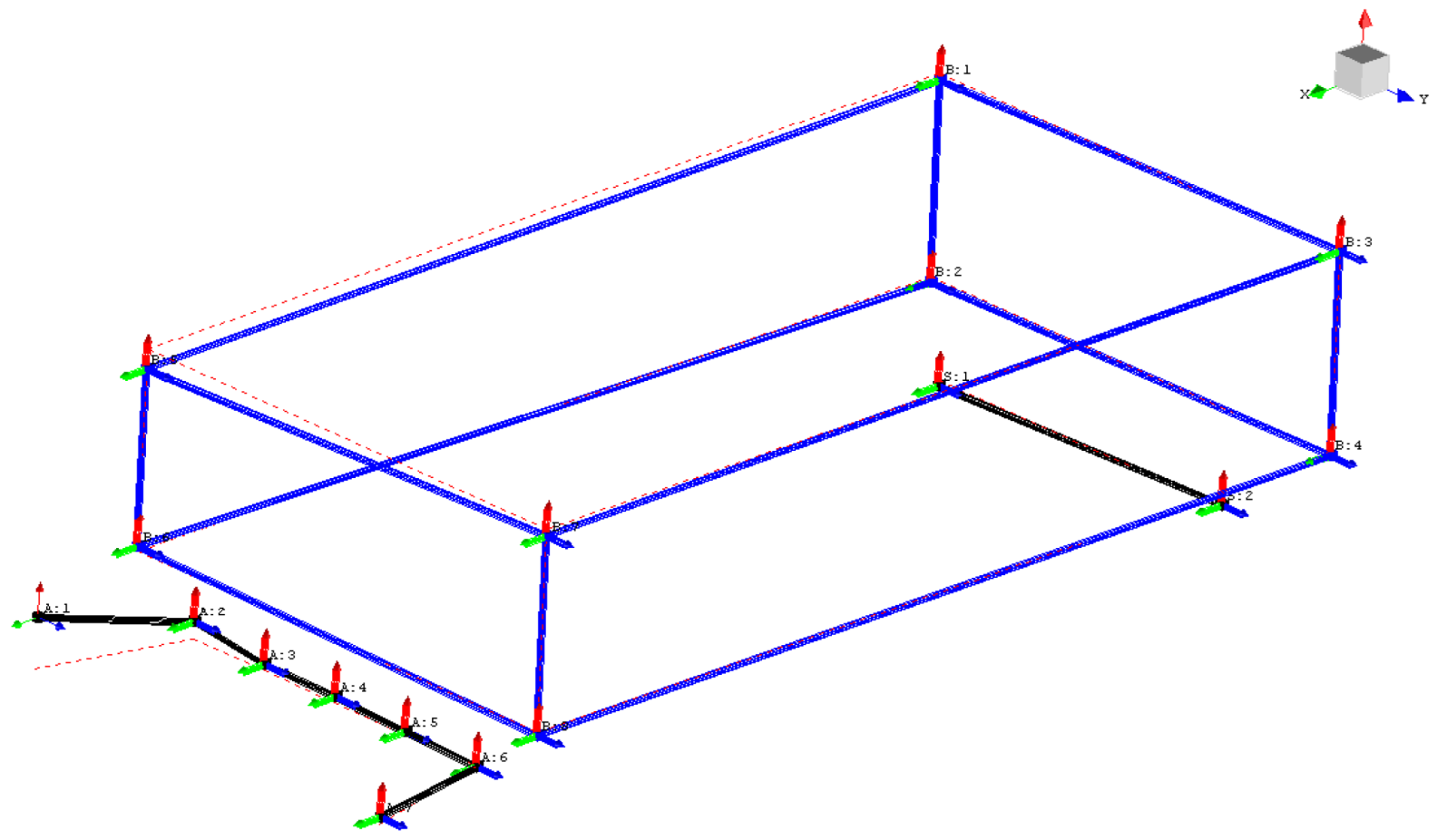

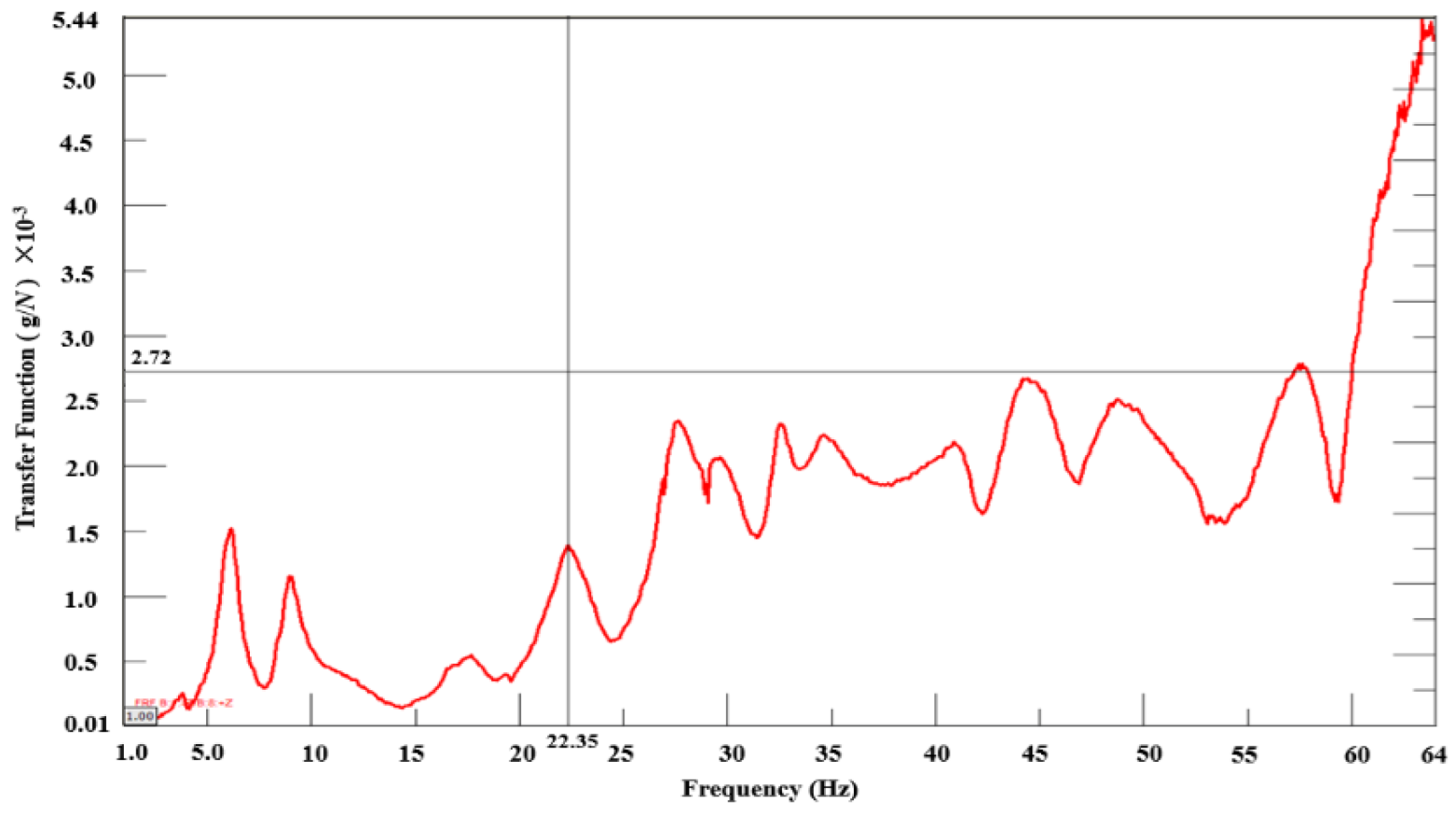

The modal frequency sweeping was conducted on both the target car and the comparative car to identify the modal parameters of their bodies and rear axles. This analysis aimed to discern the differences in the vibrational frequencies of the rear axles between the two cars, as well as their relationship to the body vibration frequencies. During the frequency sweeping of vibrational mode tests, all four wheels of each test car were elevated to a specified height and placed upon steel boxes. Electromagnetic exciters were initially positioned on either side of the rear axle to stimulate vibrations, followed by their placement at the rear-left and front-right positions of the car body to induce vertical vibrations. Acceleration sensors recorded the vertical vibrational accelerations. At the time of testing, both cars were unladen, and tire pressures were adjusted to the values specified by technical requirements. Modal transfer functions and mode shapes for the target car’s body and rear axle are presented in

Figure 25,

Figure 26,

Figure 27,

Figure 28 and

Figure 29, while those for the comparative car are shown in

Figure 30,

Figure 31,

Figure 32 and

Figure 33. The modal parameters and mode shapes were identified through fitting the modal transfer functions, establishing the system’s natural frequencies or damping characteristics. Results of the modal parameter frequency sweeping are detailed in

Table 6.

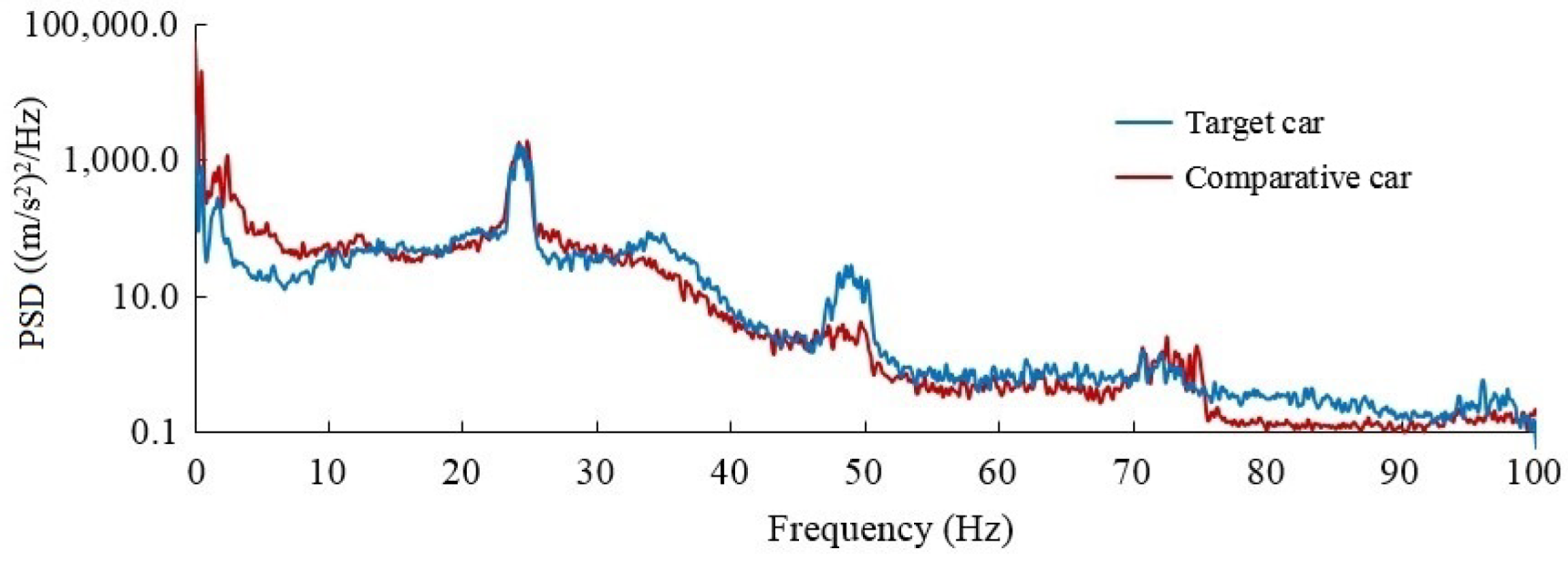

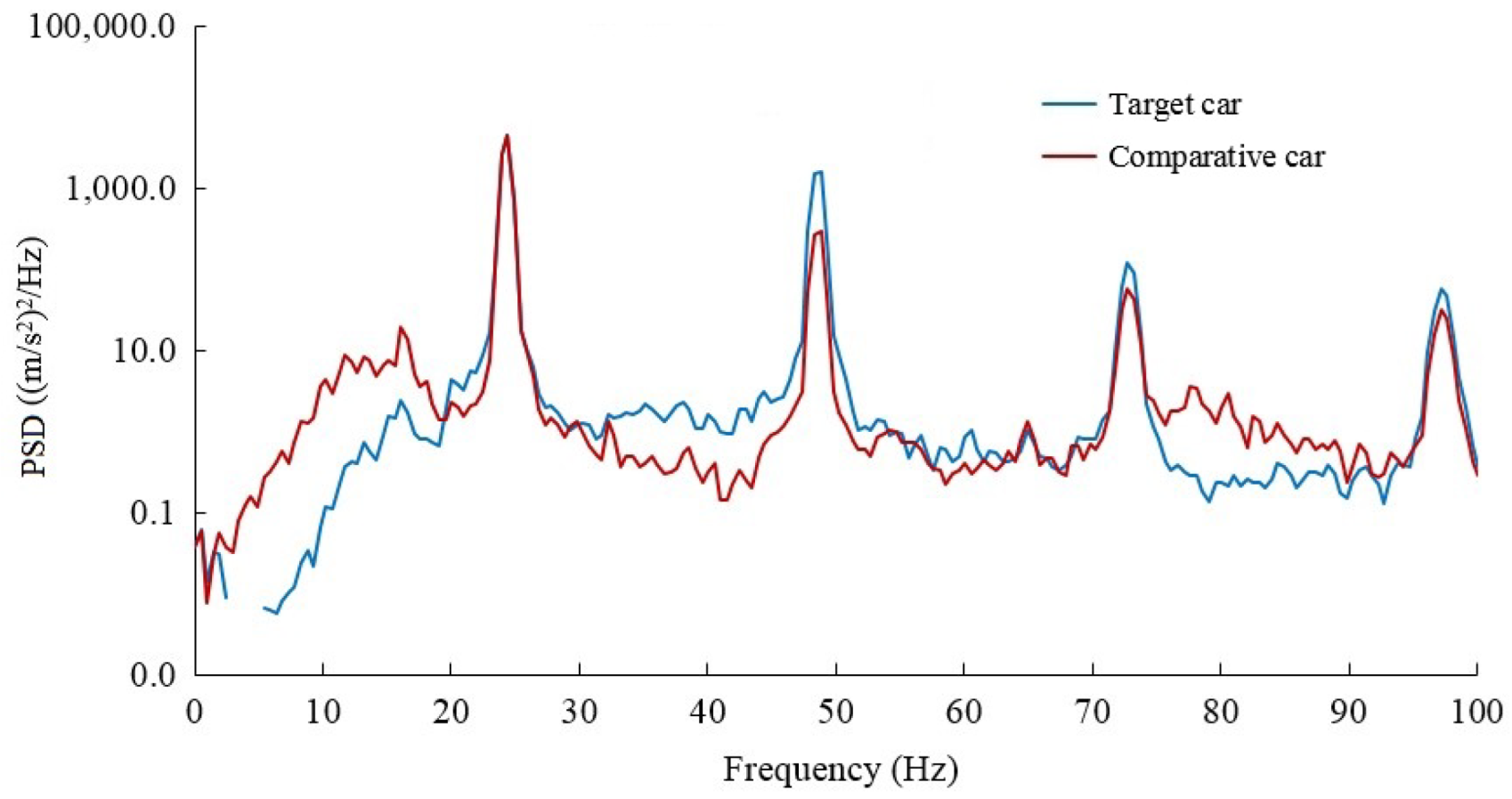

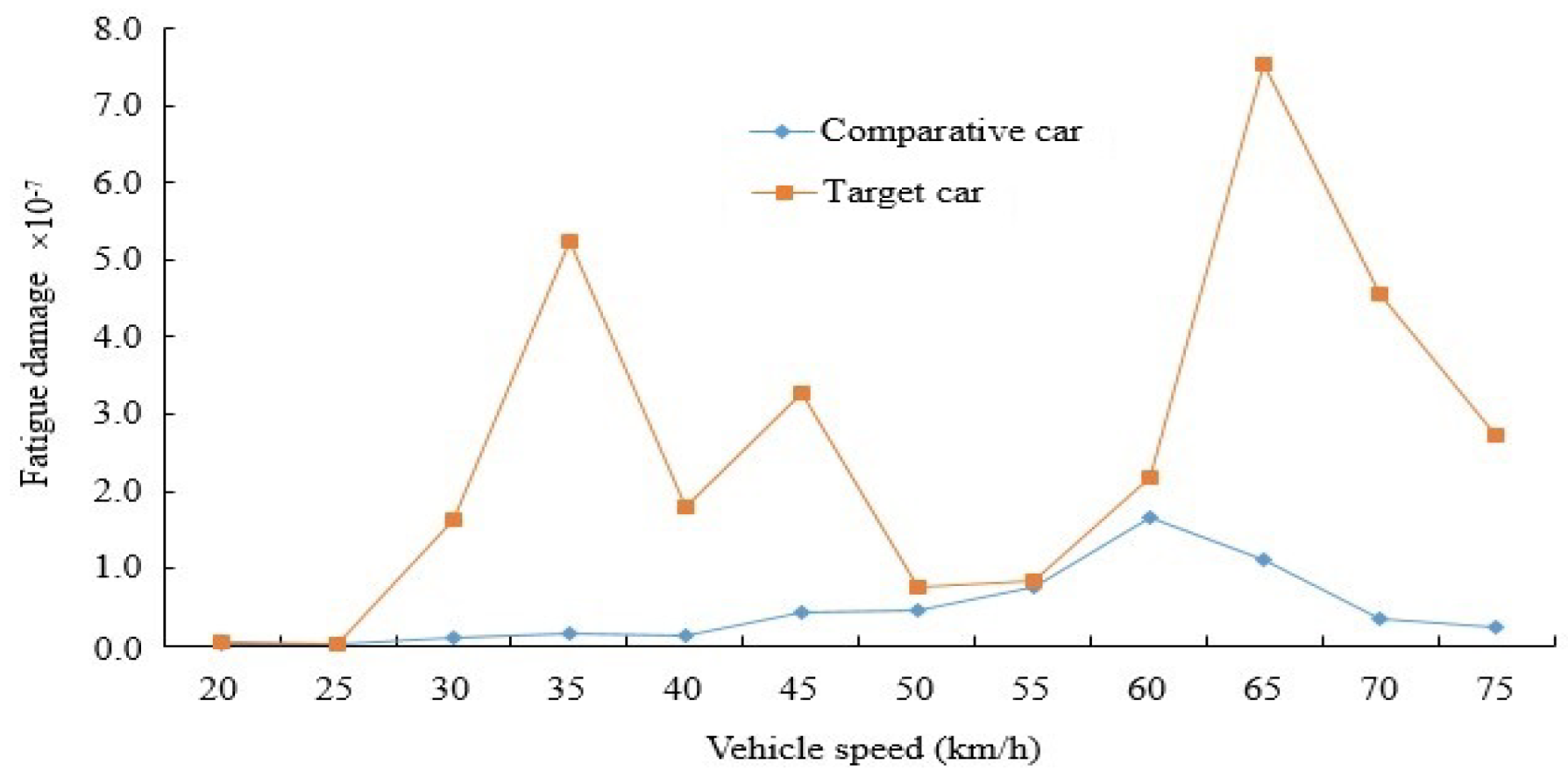

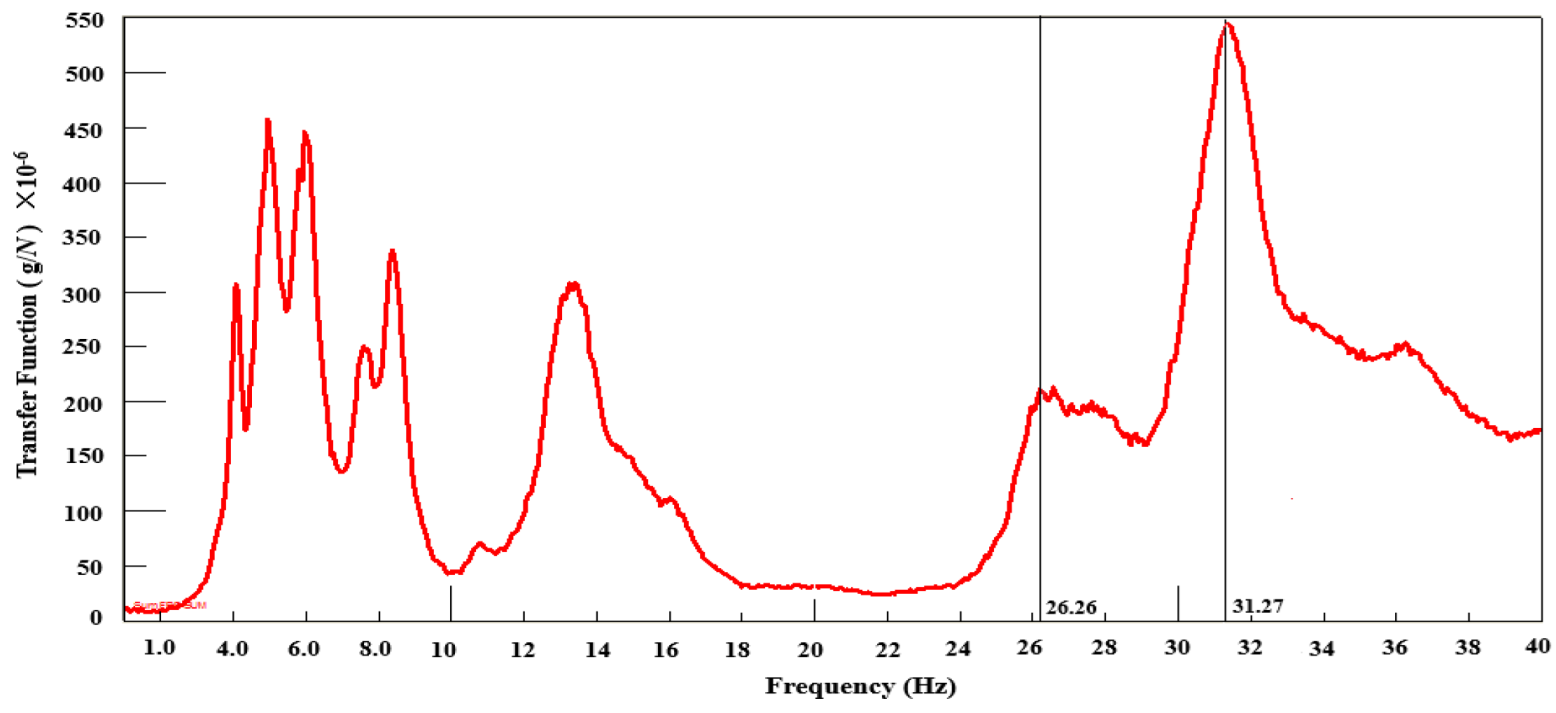

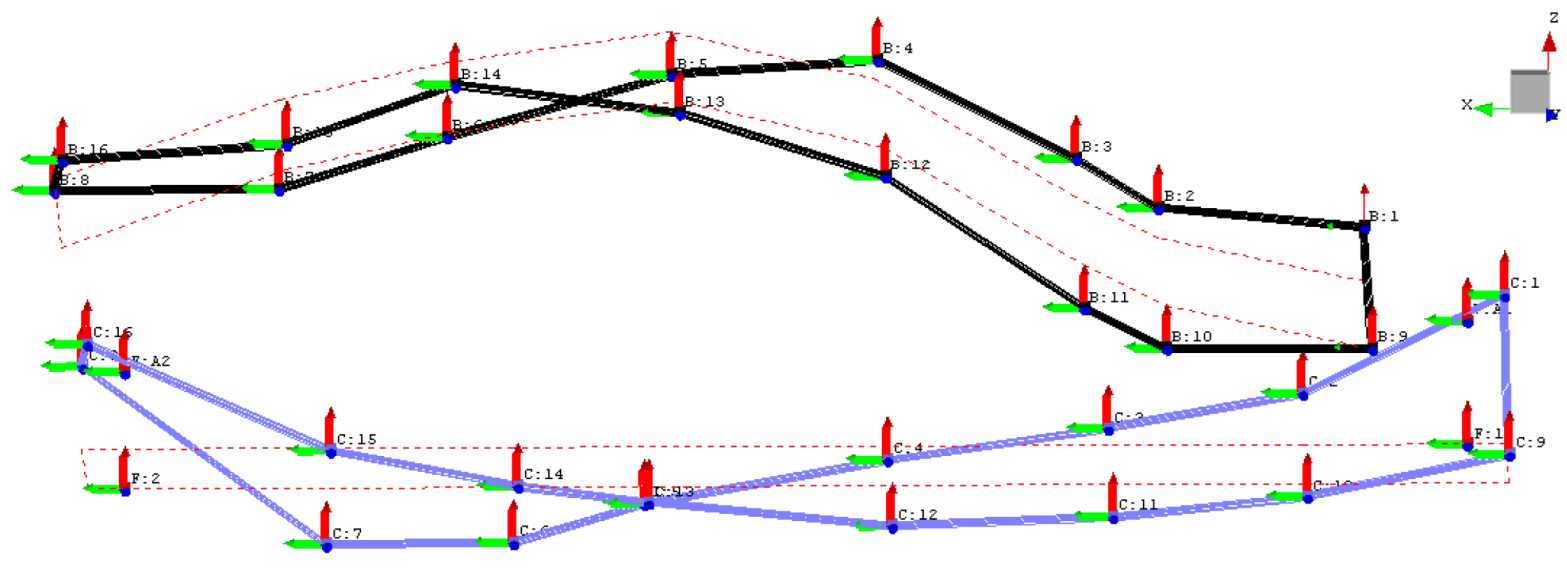

From the results of the modal frequency sweeping tests, it is evident that the first-order torsional modal frequency of the target car’s body is 3.91Hz higher than that of the comparative car, and the vertical vibrational modal frequency of the rear axle is 3.37Hz higher. Structurally, this suggests that the stiffness of the target car’s body and the rigidity of its rear axle suspension are greater than those of the comparative car. Given that the cars were unladen during these tests, it is expected that the first-order torsional and bending modal frequencies would decrease when the cars are fully loaded. During rear axle stress tests on the PG durability road surface, the high-stress amplitude frequency of the target car’s rear axle was 24Hz, closely aligning with the body’s first-order torsional frequency. In contrast, the comparative car’s rear axle high-stress amplitude frequency was 18Hz, which is significantly distant from its body’s first-order torsional frequency. Examination of the modal transfer function curves for the target car’s body and rear axle reveals an overlap in their ranges of natural frequencies, due to damping effects. When the target car traversed a washboard road at a speed of 65km/h on the PG, the rear axle’s PSD at a high-stress frequency of 24Hz was related to the body’s torsional mode.

Figure 1.

Generation of rainflow counting cycles.

Figure 1.

Generation of rainflow counting cycles.

Figure 2.

Cyclic curves of nominal and local stress-strain.

Figure 2.

Cyclic curves of nominal and local stress-strain.

Figure 3.

Morrow mean stress correction model.

Figure 3.

Morrow mean stress correction model.

Figure 4.

Vertex coordinates and mean stress of hysteresis loop.

Figure 4.

Vertex coordinates and mean stress of hysteresis loop.

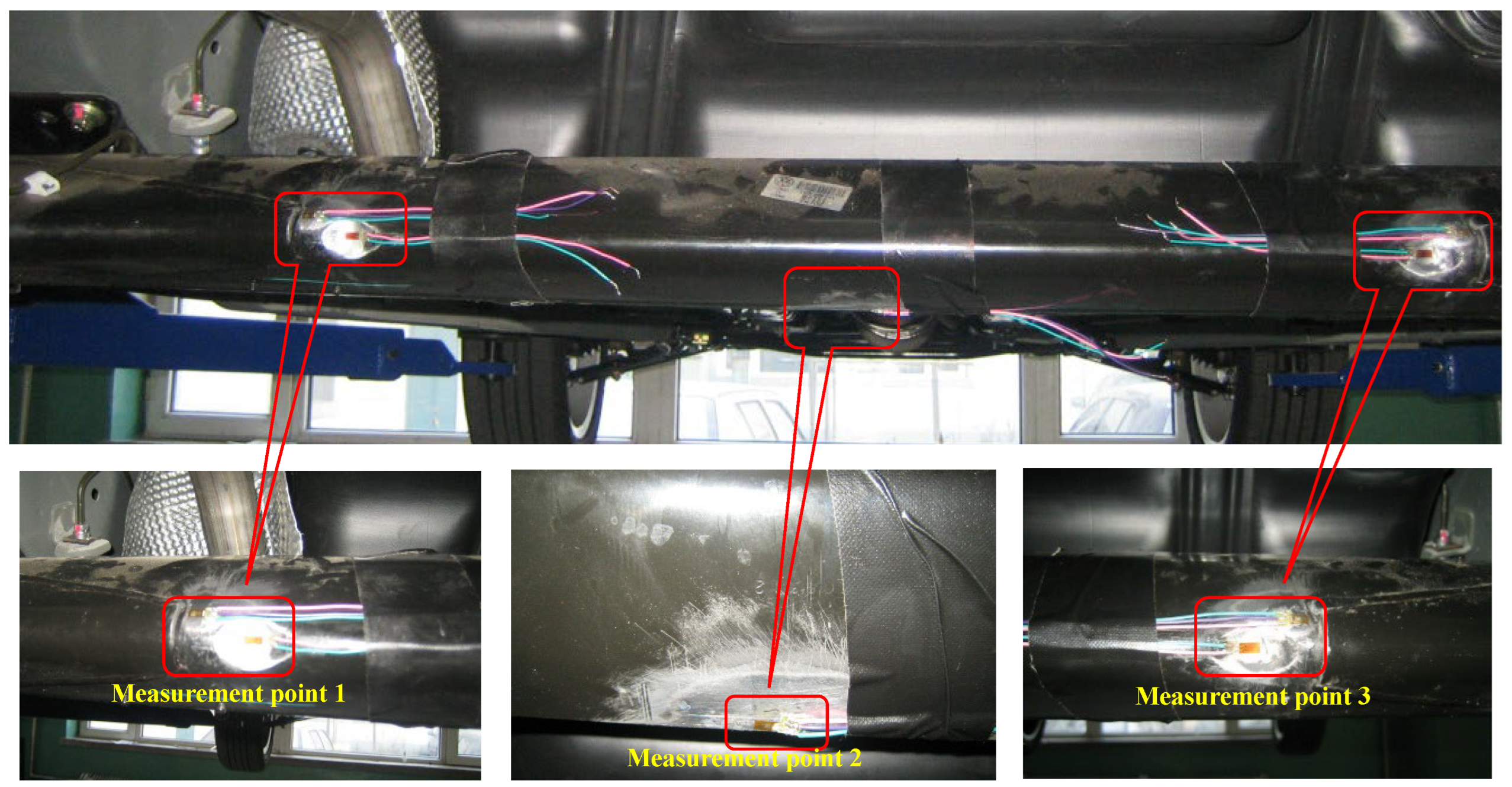

Figure 5.

Strain measurement points on rear axle.

Figure 5.

Strain measurement points on rear axle.

Figure 6.

Acquisition instrument of test data.

Figure 6.

Acquisition instrument of test data.

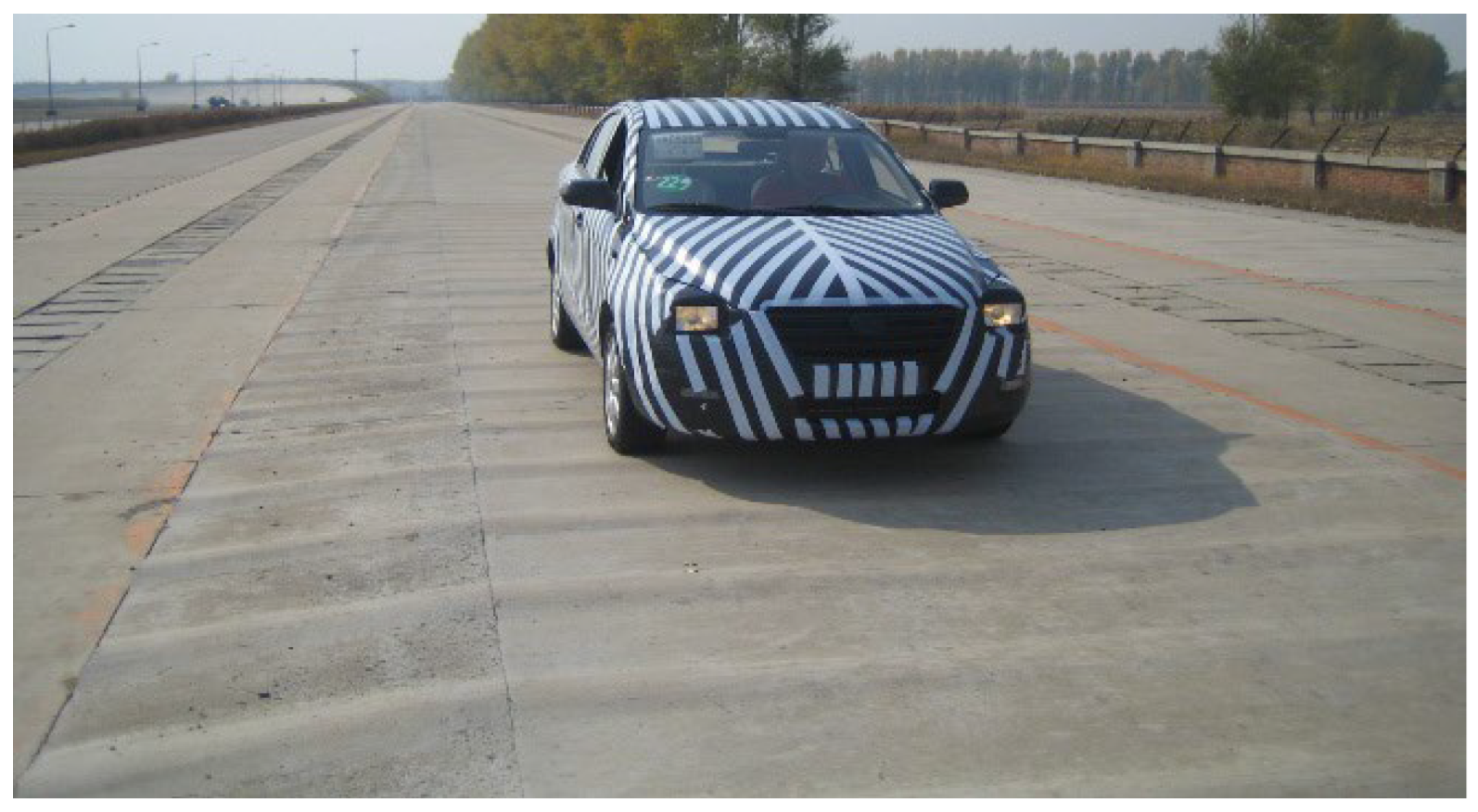

Figure 7.

Real car testing on washboard road.

Figure 7.

Real car testing on washboard road.

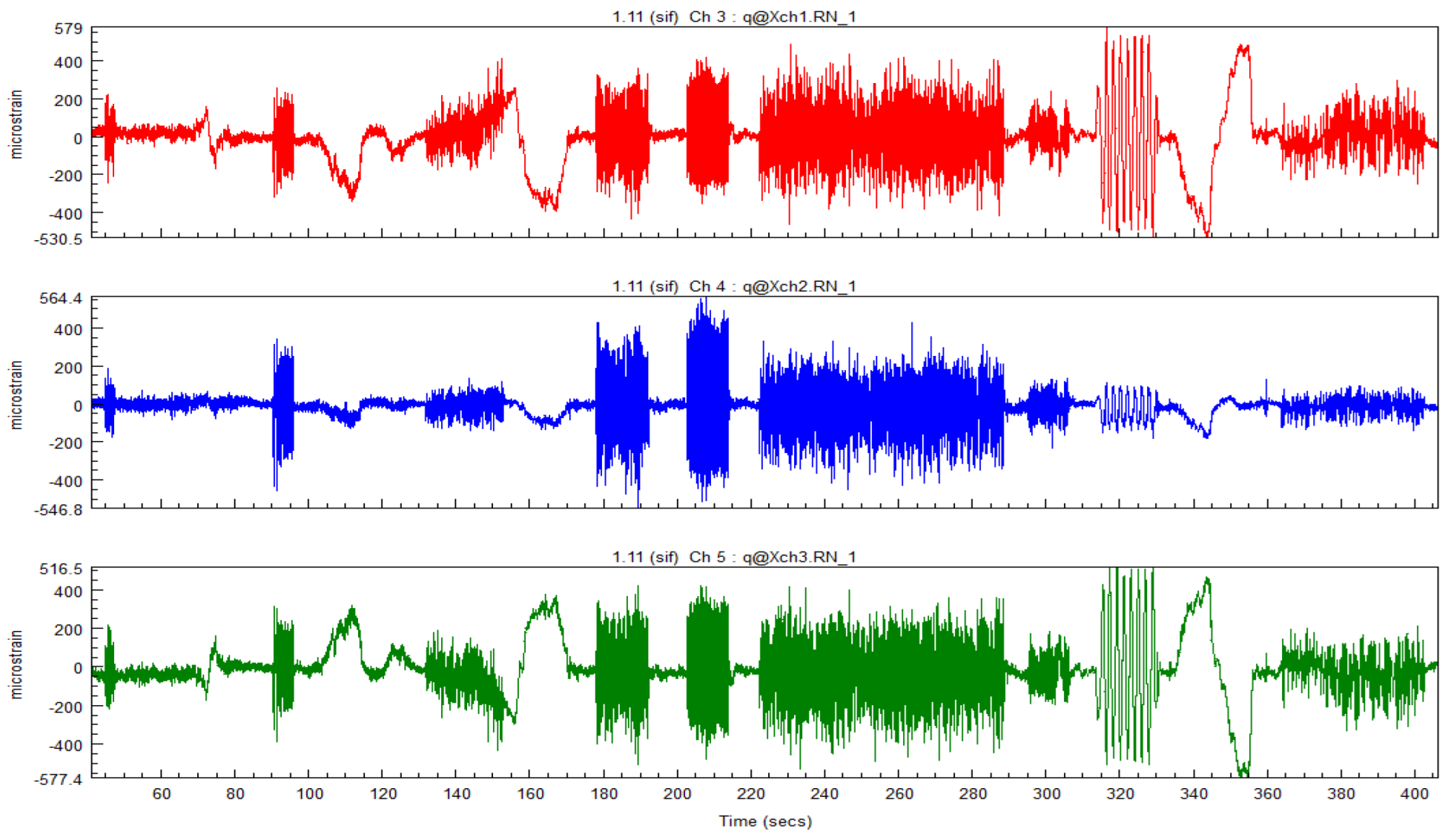

Figure 8.

Strain time-domain signal of three measurement points on rear axle.

Figure 8.

Strain time-domain signal of three measurement points on rear axle.

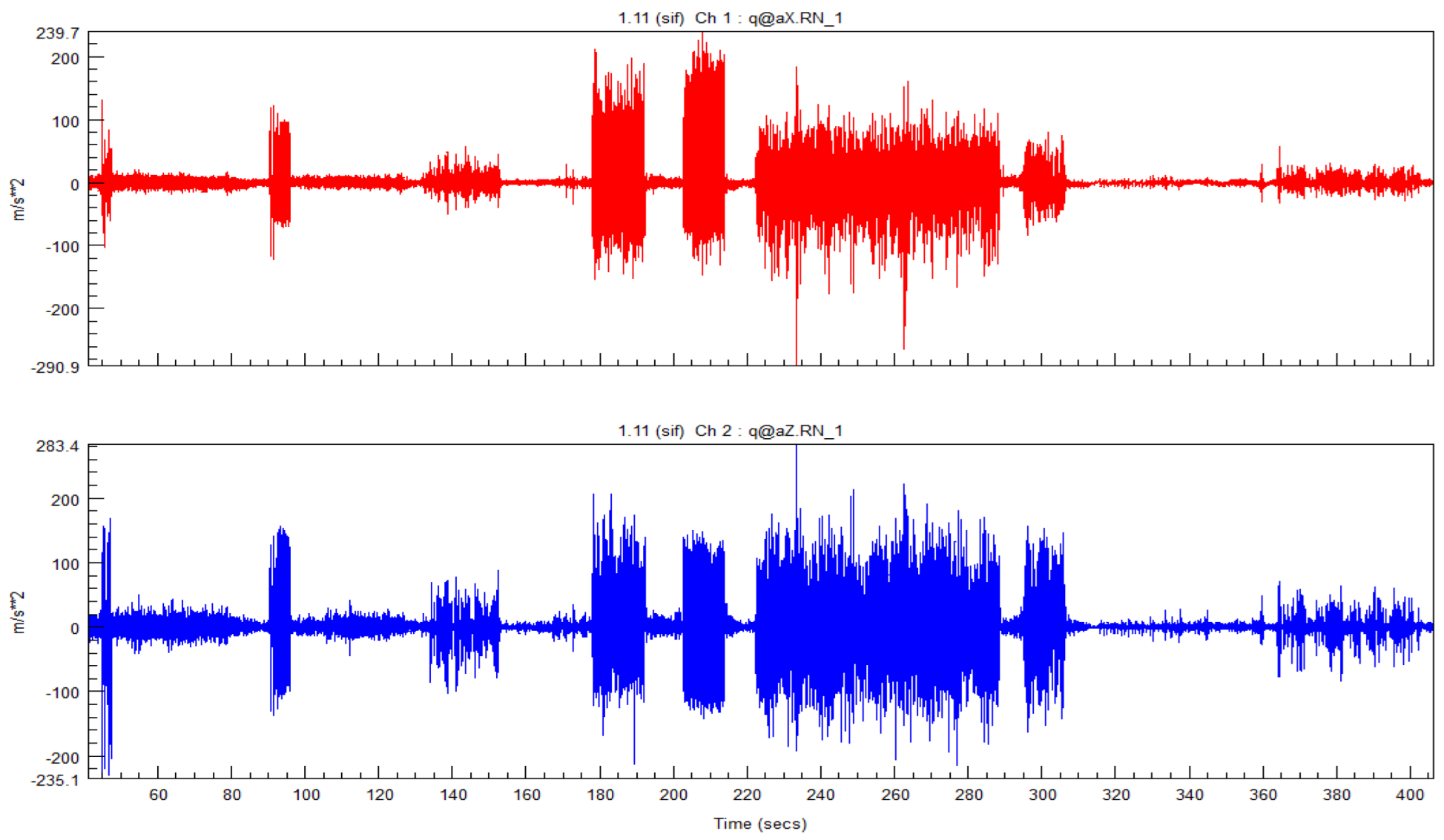

Figure 9.

Acceleration time-domain signals on rear axle end.

Figure 9.

Acceleration time-domain signals on rear axle end.

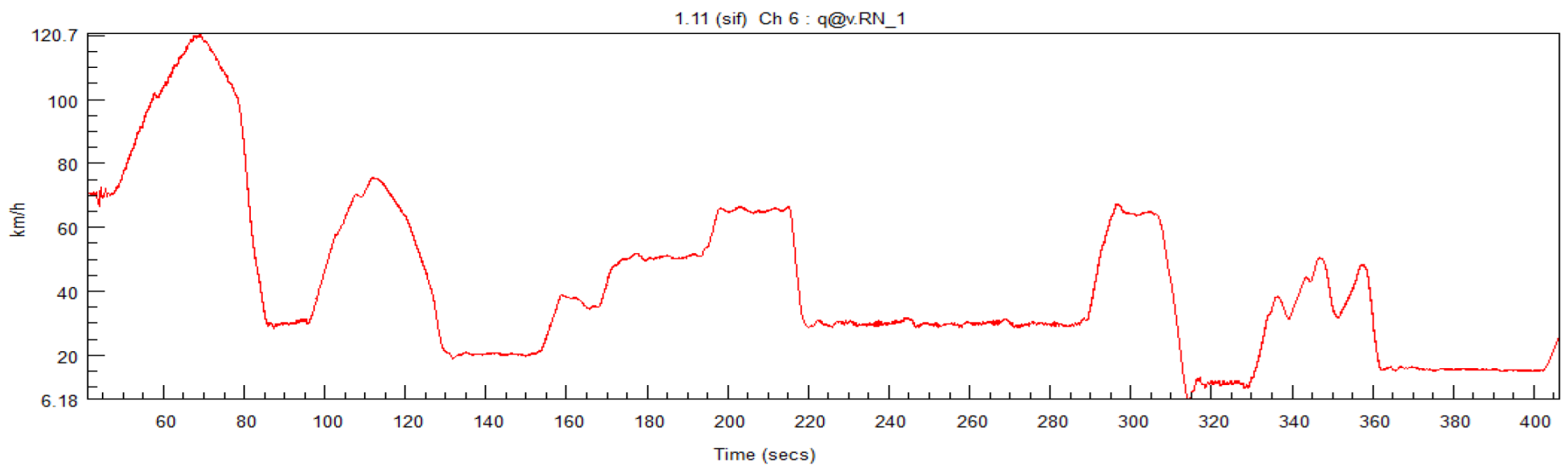

Figure 10.

Test vehicle speed signal.

Figure 10.

Test vehicle speed signal.

Figure 11.

Stress measurement of rear axle on test rig.

Figure 11.

Stress measurement of rear axle on test rig.

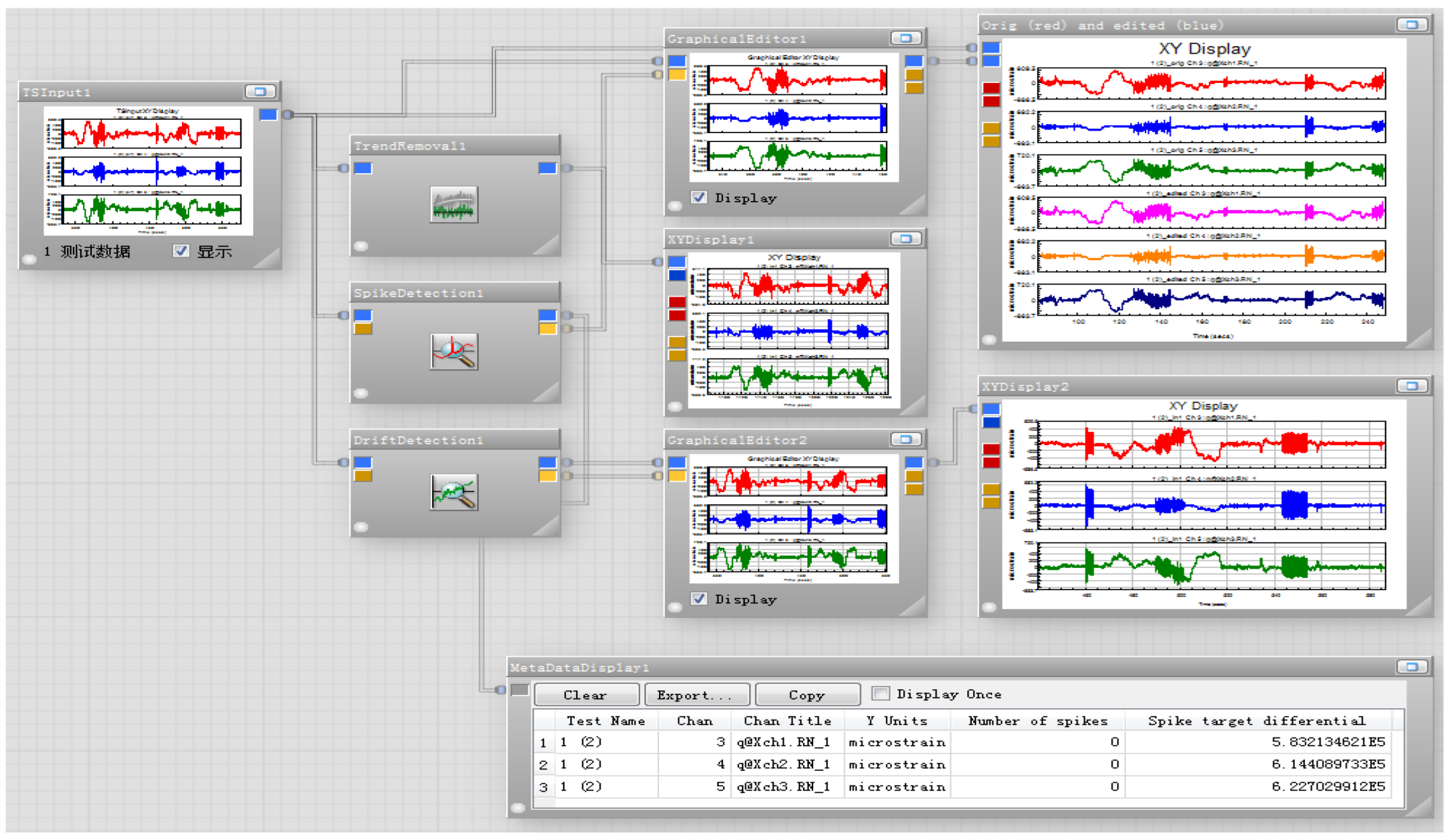

Figure 12.

Preprocessing model of test data based on Glyph Works.

Figure 12.

Preprocessing model of test data based on Glyph Works.

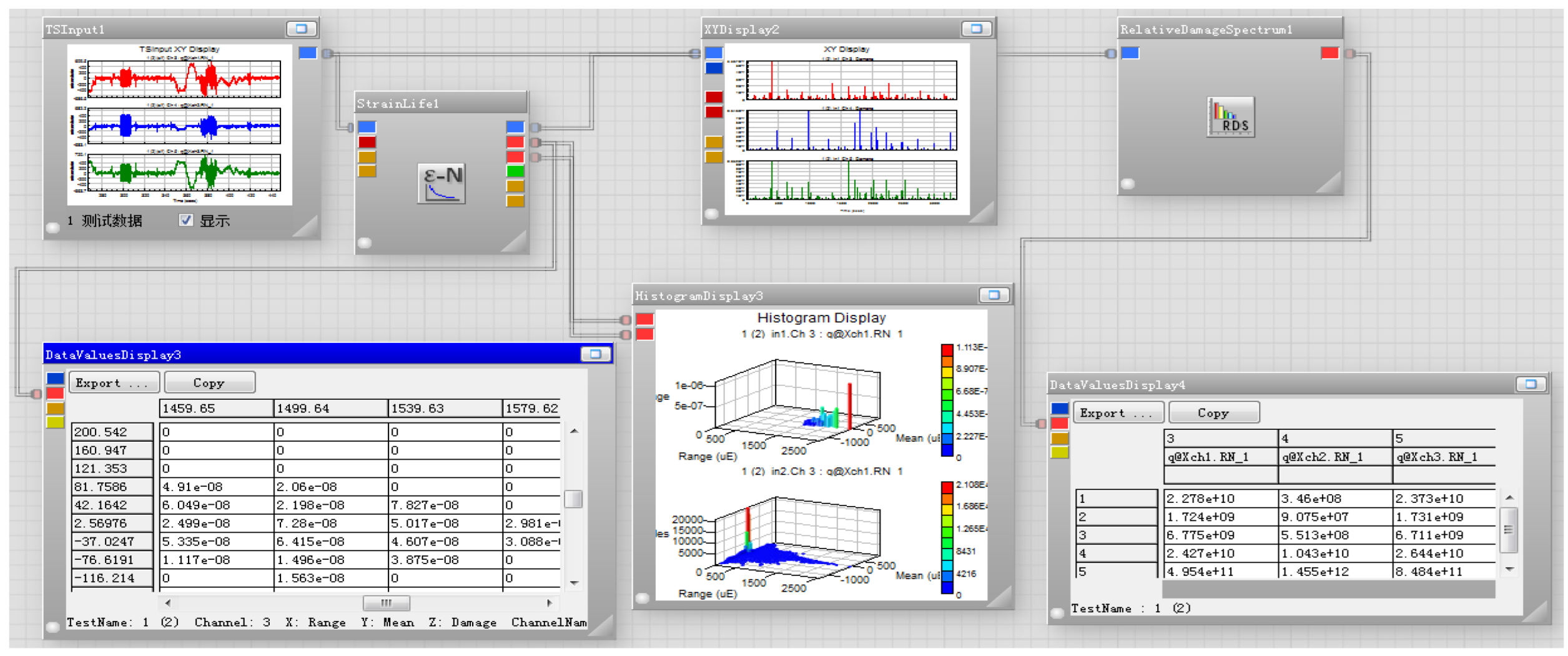

Figure 13.

Fatigue damage calculation model based on Glyph Works.

Figure 13.

Fatigue damage calculation model based on Glyph Works.

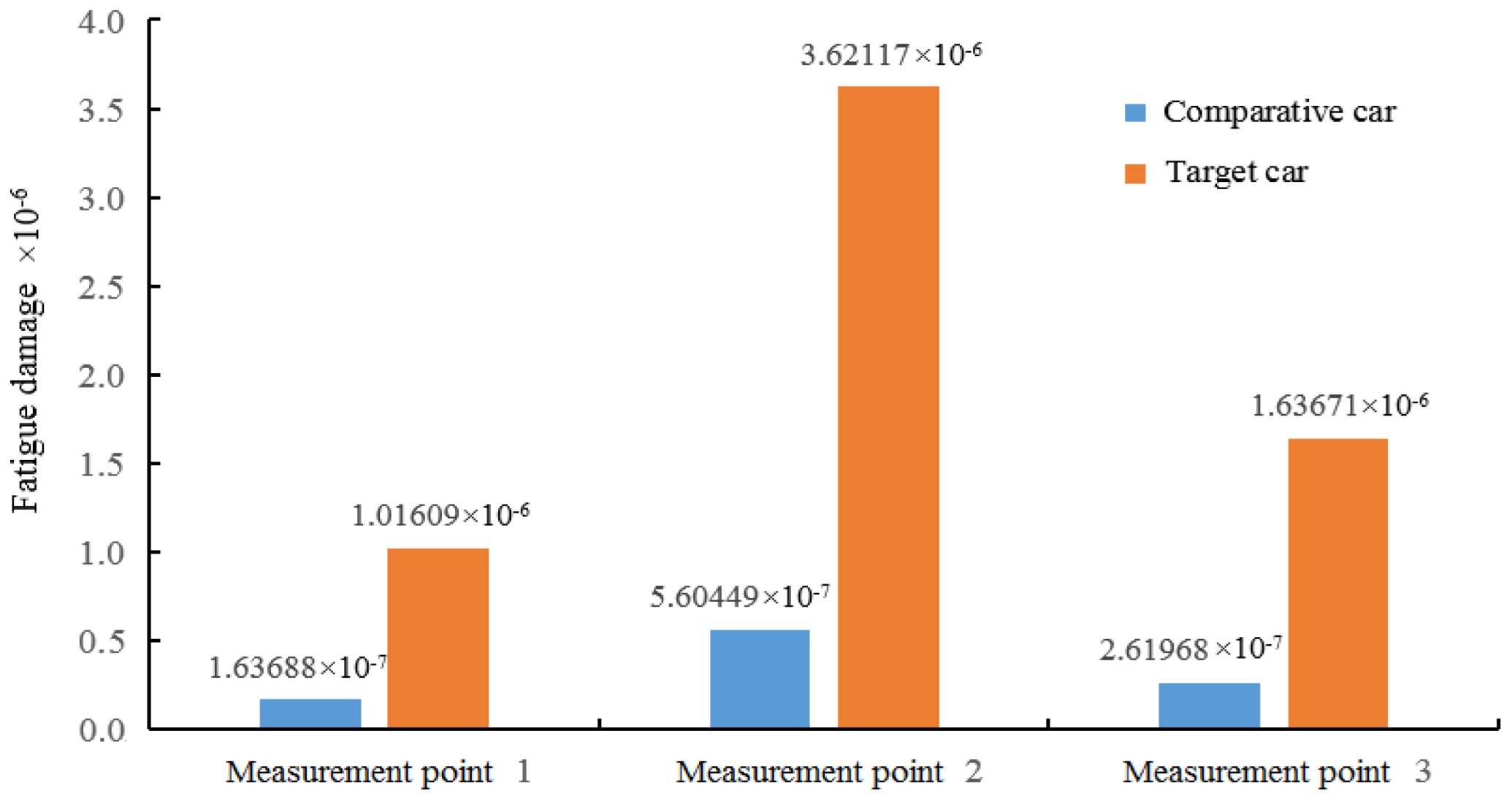

Figure 14.

Accumulated damage comparison of three measurement points.

Figure 14.

Accumulated damage comparison of three measurement points.

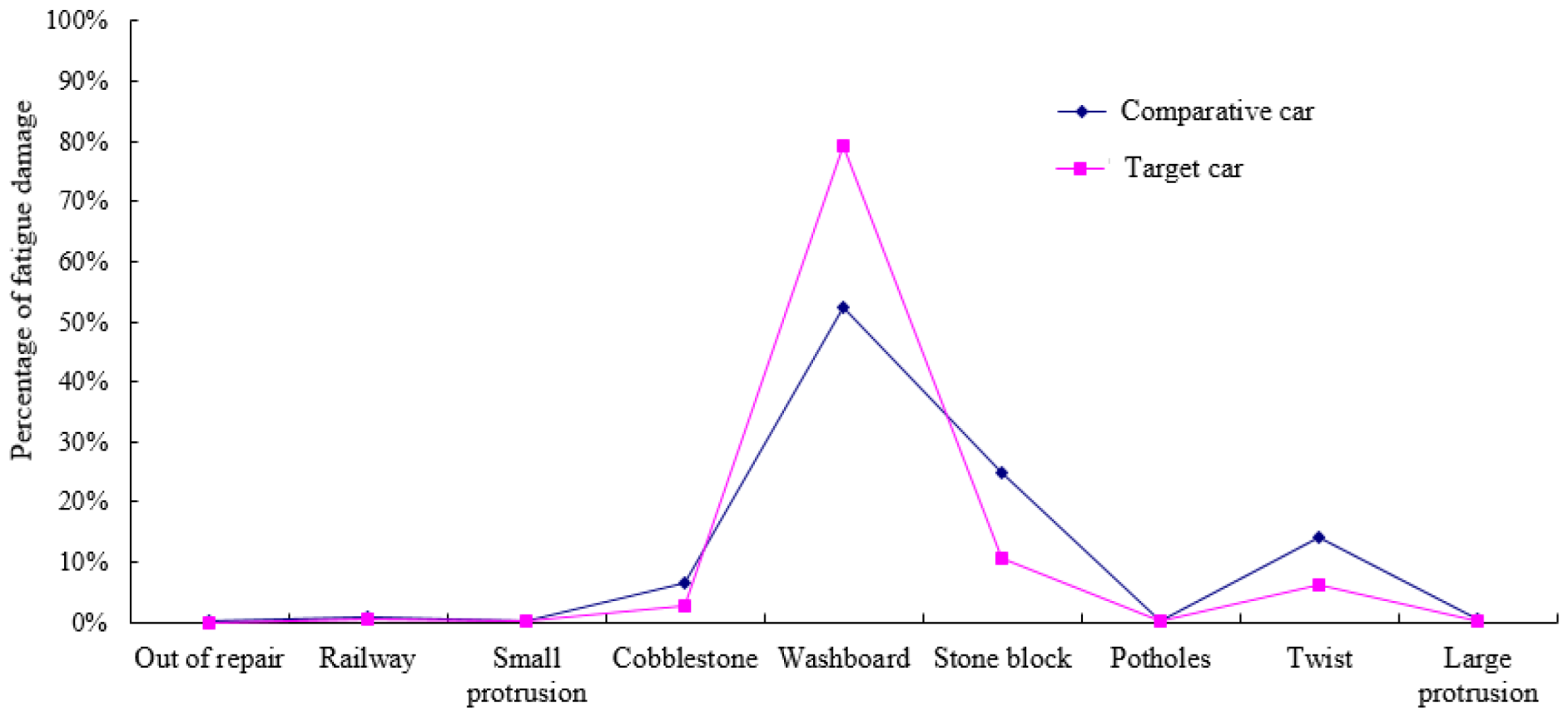

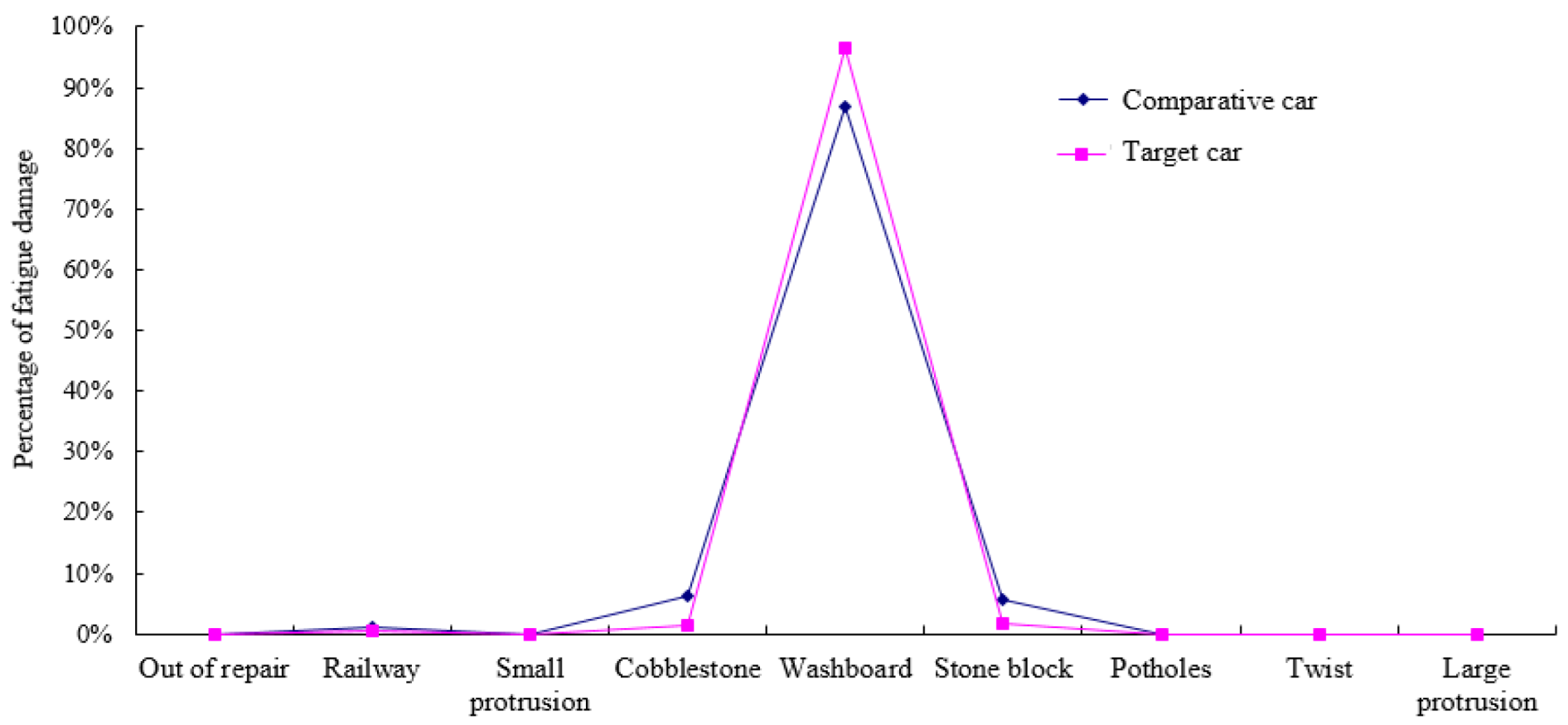

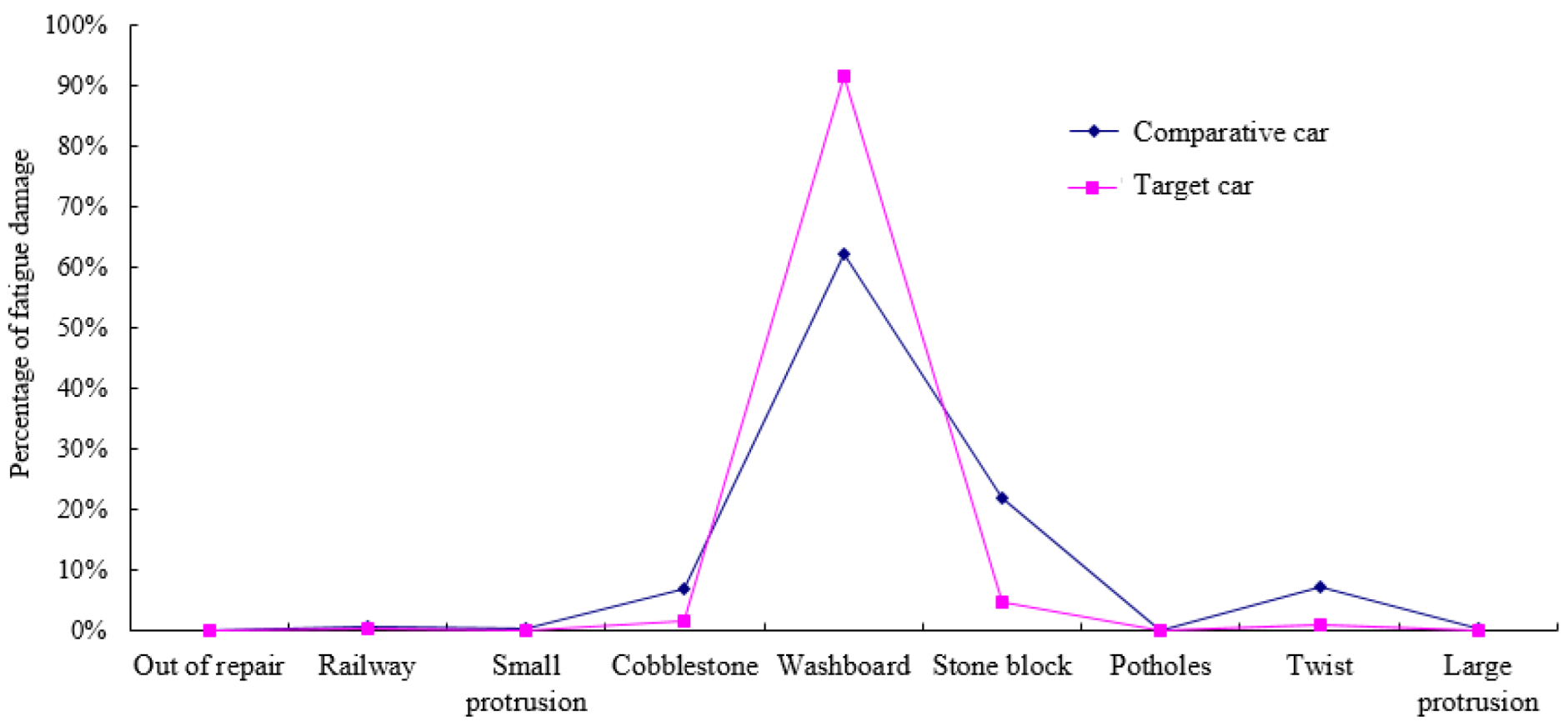

Figure 15.

Damage percentage of measurement point 1 on PG durability road.

Figure 15.

Damage percentage of measurement point 1 on PG durability road.

Figure 16.

Damage percentage of measurement point 2 on PG durability road.

Figure 16.

Damage percentage of measurement point 2 on PG durability road.

Figure 17.

Damage percentage of measurement point 3 on PG durability road.

Figure 17.

Damage percentage of measurement point 3 on PG durability road.

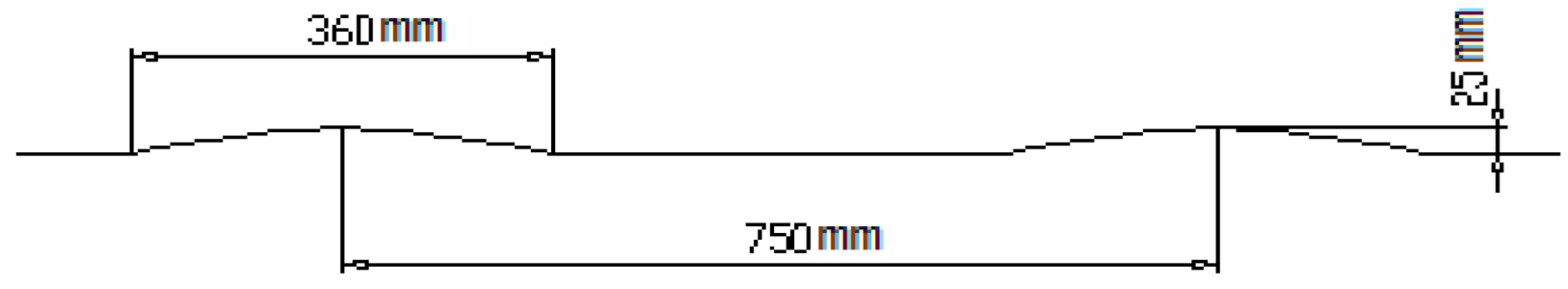

Figure 18.

Cross section of washboard road.

Figure 18.

Cross section of washboard road.

Figure 19.

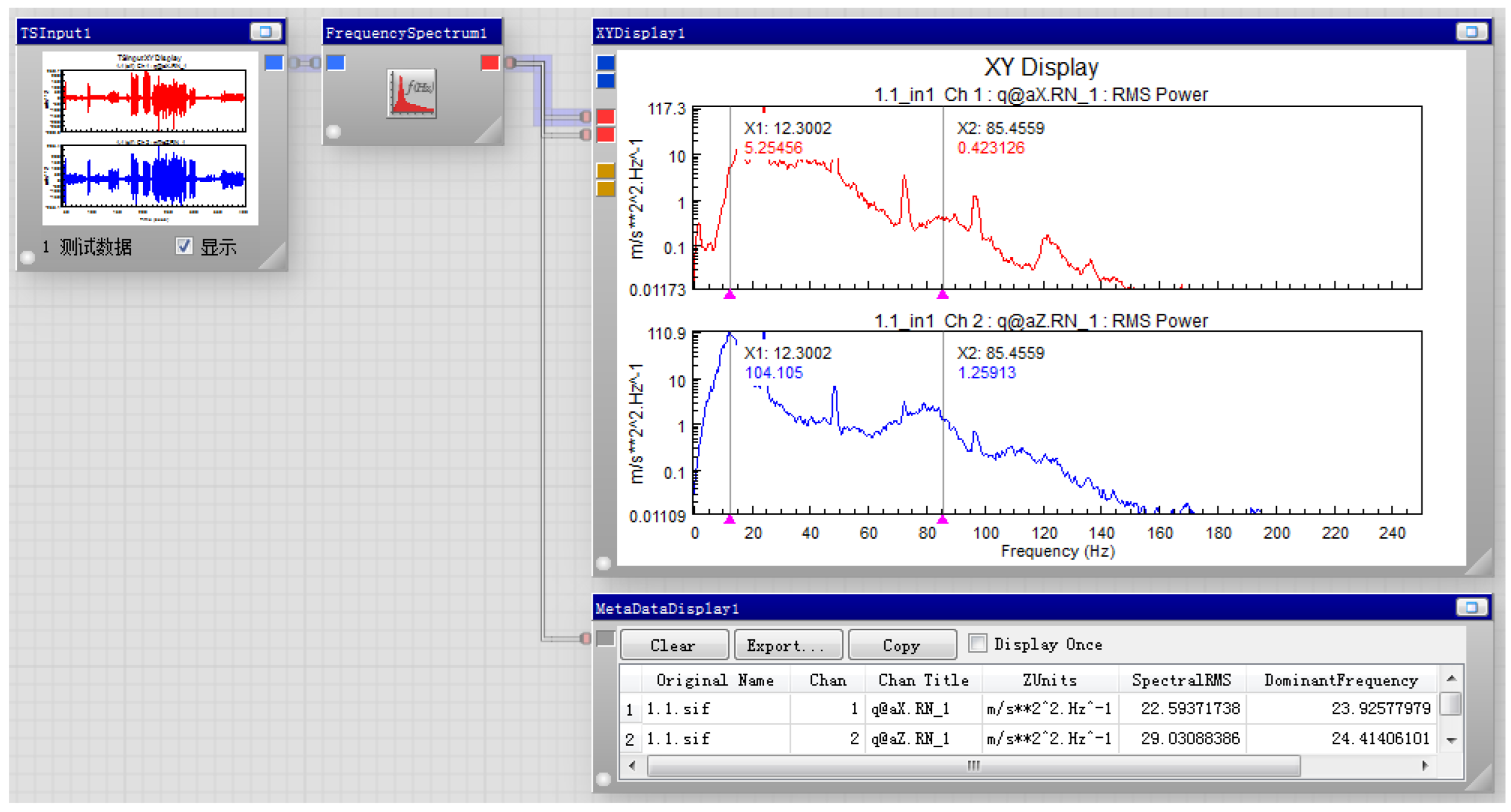

Generation model of PSD for acceleration responses.

Figure 19.

Generation model of PSD for acceleration responses.

Figure 20.

PSD of acceleration signal of rear axle end on PG durability road.

Figure 20.

PSD of acceleration signal of rear axle end on PG durability road.

Figure 21.

PSD of acceleration signal of rear axle end on washboard road.

Figure 21.

PSD of acceleration signal of rear axle end on washboard road.

Figure 22.

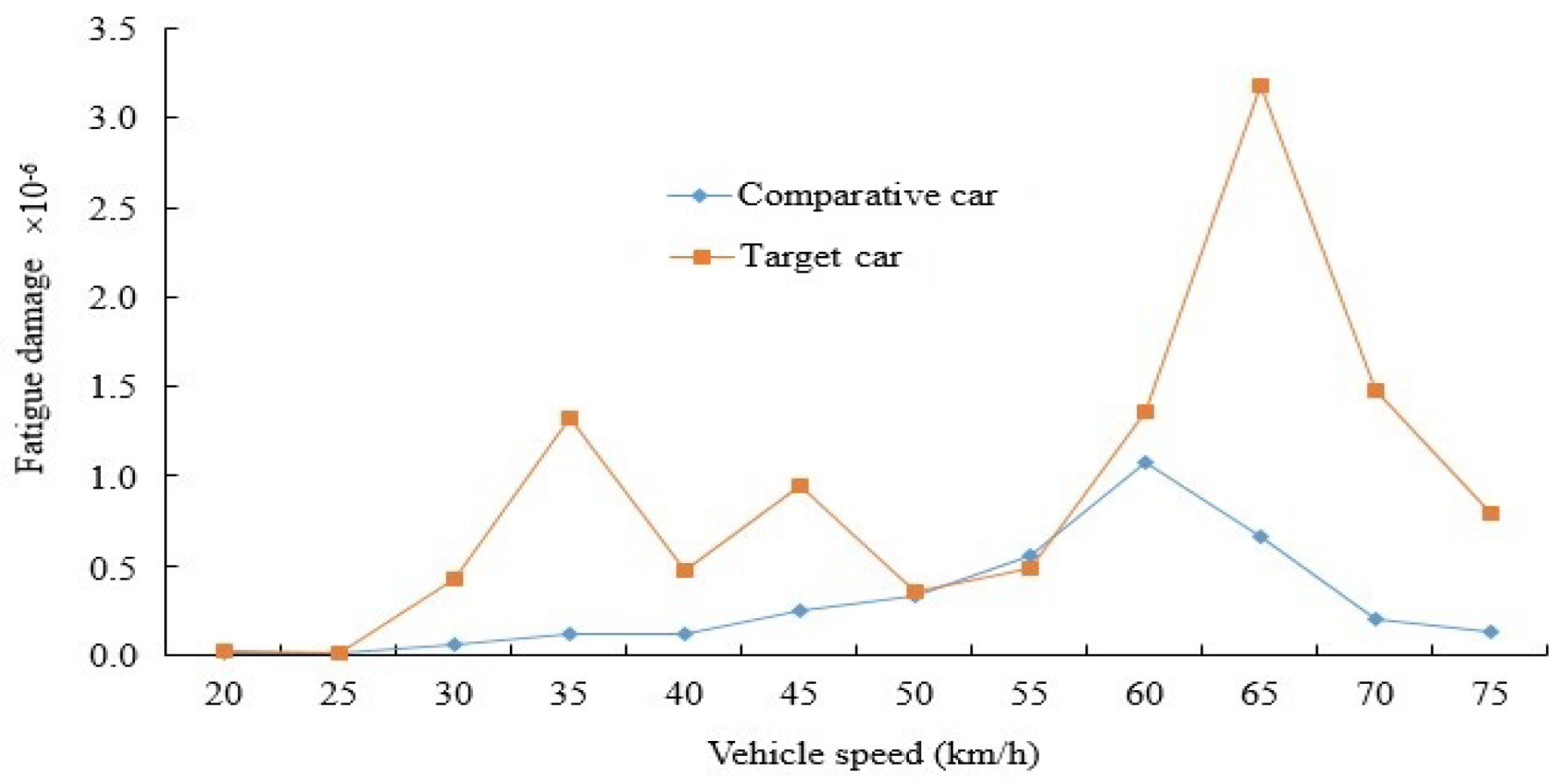

Damage comparison of measurement point 1 on washboard road.

Figure 22.

Damage comparison of measurement point 1 on washboard road.

Figure 23.

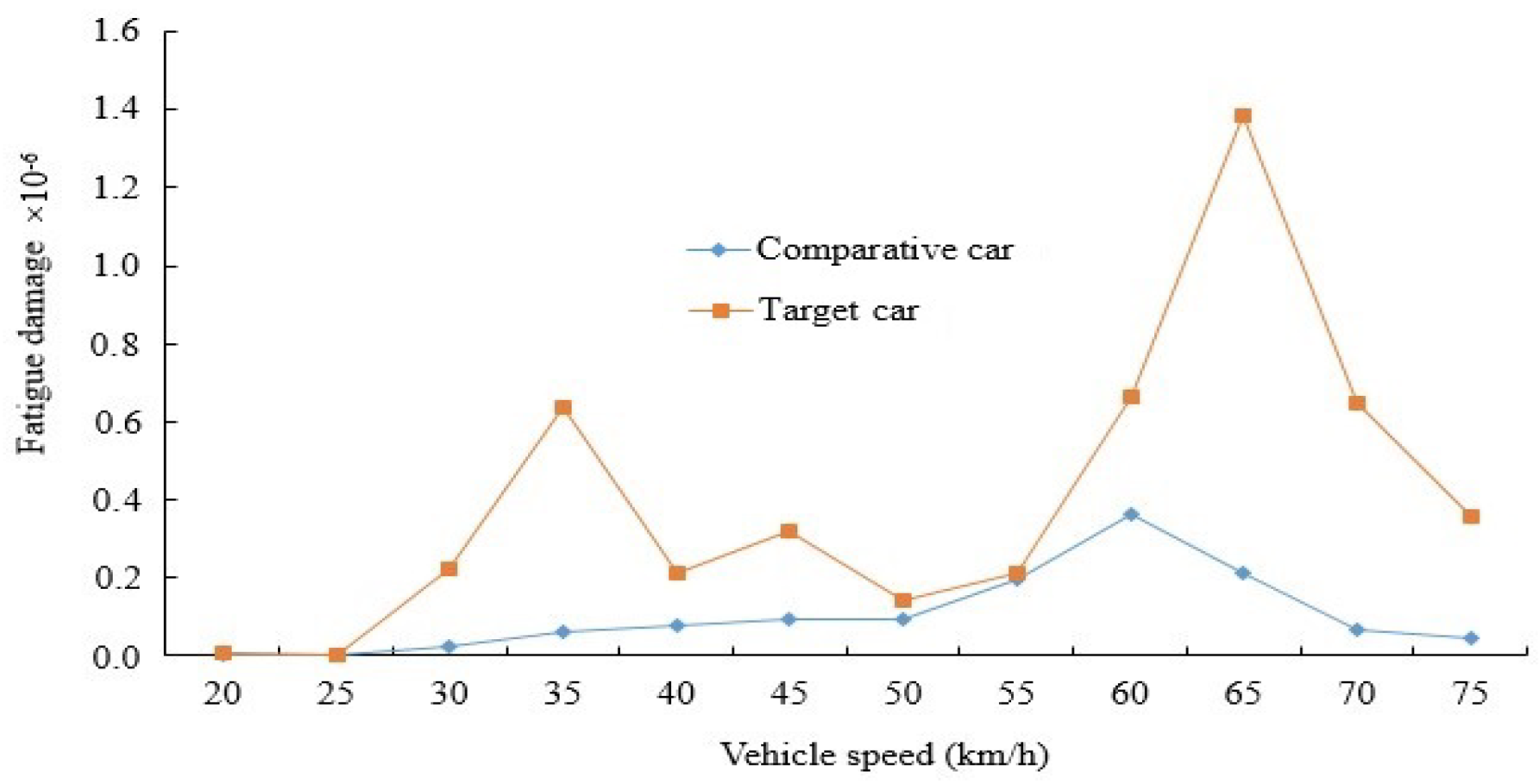

Damage comparison of measurement point 2 on washboard road.

Figure 23.

Damage comparison of measurement point 2 on washboard road.

Figure 24.

Damage comparison of measurement point 3 on washboard road.

Figure 24.

Damage comparison of measurement point 3 on washboard road.

Figure 25.

Modal transfer function curve of target car body.

Figure 25.

Modal transfer function curve of target car body.

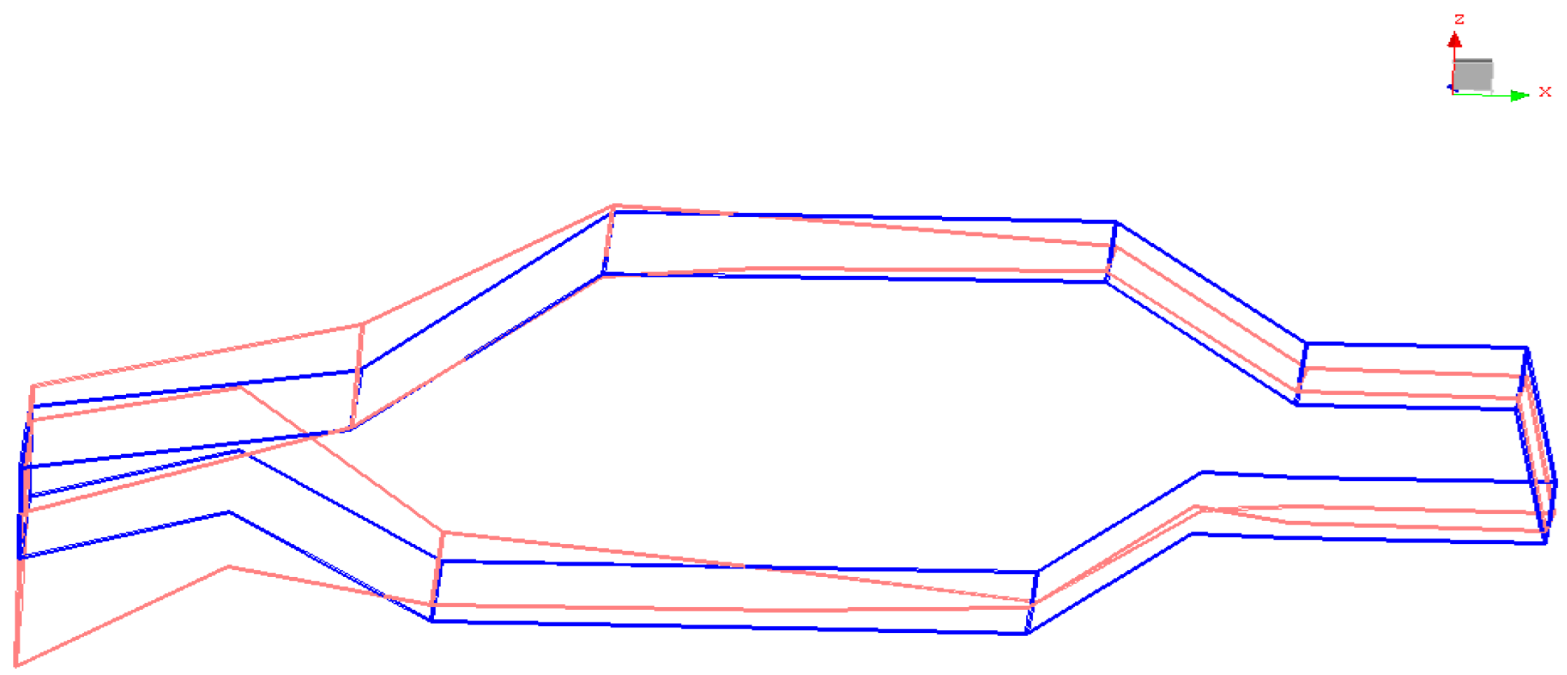

Figure 26.

First-order torsional mode shape of target car body.

Figure 26.

First-order torsional mode shape of target car body.

Figure 27.

First-order bending mode shape of target car body.

Figure 27.

First-order bending mode shape of target car body.

Figure 28.

Modal transfer function curve of rear axle for target car.

Figure 28.

Modal transfer function curve of rear axle for target car.

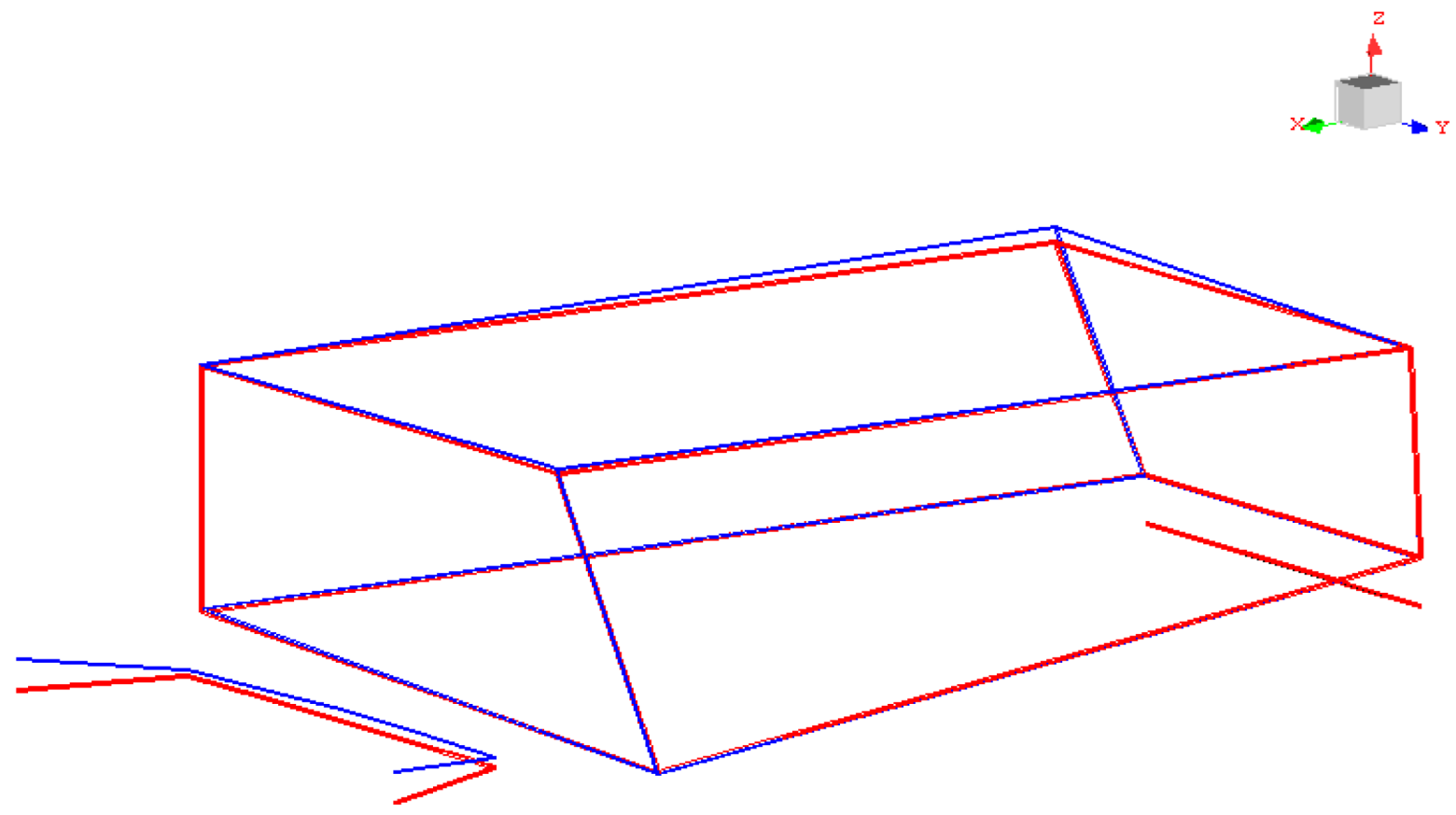

Figure 29.

Vertical vibration mode shape of rear axle for target car.

Figure 29.

Vertical vibration mode shape of rear axle for target car.

Figure 30.

Modal transfer function curve of comparative car body.

Figure 30.

Modal transfer function curve of comparative car body.

Figure 31.

First-order torsional mode shape of comparative car body.

Figure 31.

First-order torsional mode shape of comparative car body.

Figure 32.

Modal transfer function curve of rear axle for comparative car.

Figure 32.

Modal transfer function curve of rear axle for comparative car.

Figure 33.

Vertical vibration mode shape of rear axle for comparative car.

Figure 33.

Vertical vibration mode shape of rear axle for comparative car.

Table 1.

Material parameters of rear axle for damage calculation.

Table 1.

Material parameters of rear axle for damage calculation.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Material constant a

|

0.046mm |

| Fillet radius of notch root r

|

3.50mm |

| Theoretical stress concentration factor Kt

|

1.68 |

| Modulus of elasticity E

|

2.07×105MPa |

| Poisson’s ratio |

0.3 |

| Cyclic strength coefficient K’ |

2648MPa |

| Cyclic hardening exponent ń |

0.13 |

| Fatigue strength coefficient σ́́f

|

1350MPa |

| Fatigue ductility coefficient έf

|

0.501 |

| Fatigue strength exponent b

|

-0.103 |

| Fatigue ductility exponent c

|

-0.512 |

Table 2.

Maximum test stress at each measurement point.

Table 2.

Maximum test stress at each measurement point.

Measurement

location |

Measurement parameter value (MPa) |

Target

Car |

Comparative Car |

Ratio of target car to comparative car |

| Measurement point 1 |

Von Mises stress |

59 |

54 |

1.092 |

| Principal stress 1 |

65 |

62 |

1.048 |

| Principal stress 2 |

-67 |

-56 |

1.196 |

| Measurement point 2 |

Von Mises stress |

143 |

131 |

1.092 |

| Principal stress 1 |

160 |

135 |

1.185 |

| Principal stress 2 |

-131 |

-122 |

1.073 |

| Measurement point 3 |

Von Mises stress |

69 |

67 |

1.029 |

| Principal stress 1 |

52 |

48 |

1.083 |

| Principal stress 2 |

-56 |

-51 |

1.098 |

Table 3.

Damage distribution of three measurement points on PG durability road.

Table 3.

Damage distribution of three measurement points on PG durability road.

| PG durability road |

Comparative Car |

Target Car |

| Measurement point 1 |

Measurement point 2 |

Measurement point 3 |

Measurement point 1 |

Measurement point 2 |

Measurement point 3 |

| Out of repair |

1.2033×10-10

|

1.1545×10-10

|

1.1690×10-10

|

1.4018×10-10

|

7.2672×10-11

|

1.3760×10-10

|

| Railway |

1.2109×10-9

|

7.2828×10-9

|

2.5001×10-9

|

5.4458×10-9

|

1.6166×10-8

|

6.6532×10-9

|

| Small protrusion |

6.1943×10-10

|

5.9324×10-11

|

6.9517×10-10

|

1.2863×10-9

|

1.1871×10-10

|

5.2939×10-10

|

| Cobblestone |

1.0601×10-8

|

3.5937×10-8

|

1.7528×10-8

|

2.9251×10-8

|

4.8485×10-8

|

2.7530×10-8

|

| Washboard |

8.3171×10-8

|

4.7897×10-6

|

1.5561×10-7

|

8.2137×10-7

|

3.5005×10-6

|

1.5130×10-6

|

| Stone block |

4.3704×10-8

|

3.7872×10-8

|

6.3032×10-8

|

9.8639×10-8

|

5.5360×10-8

|

7.1334×10-8

|

| Potholes |

2.9043×10-10

|

1.4872×10-10

|

2.6931×10-10

|

5.9450×10-10

|

2.5382×10-10

|

4.6953×10-10

|

| Twisted |

2.3306×10-8

|

1.8745×10-11

|

2.1340×10-8

|

5.7418×10-8

|

8.1182×10-11

|

1.6155×10-8

|

| Large protrusion |

6.6385×10-10

|

4.4213×10-11

|

8.6716×10-10

|

1.9363×10-9

|

7.8974×10-11

|

8.0858×10-10

|

Table 4.

Standard deviation of strain signal on washboard road.

Table 4.

Standard deviation of strain signal on washboard road.

Vehicle speed

(km/h) |

Comparative Car |

Target Car |

| Measurement point 1 |

Measurement point 2 |

Measurement point 3 |

Measurement point 1 |

Measurement point 2 |

Measurement point 3 |

| 20 |

48.16 |

73.02 |

60.32 |

63.95 |

77.13 |

70.88 |

| 25 |

69.51 |

100.28 |

80.61 |

72.10 |

104.60 |

152.89 |

| 30 |

139.04 |

196.10 |

159.05 |

170.63 |

215.79 |

201.26 |

| 35 |

97.34 |

147.29 |

126.93 |

233.62 |

290.50 |

229.97 |

| 40 |

108.64 |

163.95 |

140.20 |

180.15 |

234.51 |

237.60 |

| 45 |

147.49 |

209.30 |

171.89 |

190.96 |

247.70 |

198.58 |

| 50 |

123.30 |

169.14 |

176.95 |

123.20 |

174.47 |

183.89 |

| 55 |

182.02 |

283.49 |

243.71 |

185.41 |

292.20 |

255.64 |

| 60 |

231.83 |

338.91 |

280.78 |

261.84 |

361.94 |

300.16 |

| 65 |

179.96 |

251.78 |

203.76 |

343.17 |

428.30 |

321.08 |

| 70 |

154.07 |

213.22 |

172.99 |

284.53 |

321.45 |

268.65 |

| 75 |

161.20 |

222.24 |

182.95 |

250.49 |

311.40 |

290.73 |

Table 5.

Root mean square (RMS) of acceleration signals on washboard road.

Table 5.

Root mean square (RMS) of acceleration signals on washboard road.

Vehicle speed

(km/h) |

Comparative Car |

Target Car |

|

ax (m/s2) |

az (m/s2) |

ax (m/s2) |

az (m/s2) |

| 20 |

28.477 |

55.436 |

29.234 |

59.579 |

| 25 |

24.824 |

48.922 |

25.480 |

49.954 |

| 30 |

33.333 |

70.991 |

38.297 |

76.634 |

| 35 |

57.502 |

100.267 |

61.796 |

102.267 |

| 40 |

56.231 |

104.147 |

64.037 |

107.124 |

| 45 |

52.986 |

93.972 |

62.027 |

95.394 |

| 50 |

68.805 |

81.098 |

69.838 |

90.852 |

| 55 |

82.314 |

72.753 |

87.306 |

77.161 |

| 60 |

90.917 |

69.925 |

92.015 |

73.326 |

| 65 |

90.169 |

80.356 |

96.015 |

88.315 |

| 70 |

68.566 |

64.734 |

68.850 |

68.061 |

| 75 |

65.464 |

80.378 |

67.349 |

82.465 |

Table 6.

Frequency sweep results of modal parameters.

Table 6.

Frequency sweep results of modal parameters.

| Testing vehicle |

Modal type |

Natural frequency (Hz) |

Damping ratio (%) |

| Target car |

First-order torsional mode of car body |

26.26 |

3.76 |

| First-order bending mode of car body |

31.27 |

3.51 |

| Vertical vibration mode of rear axle |

23.53 |

18.5 |

| Comparative car |

First-order torsional mode of car body |

22.35 |

3.45 |

| First-order bending mode of car body |

27.63 |

3.74 |

| Vertical vibration mode of rear axle |

20.16 |

5.46 |