Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

Multiple Sequence Alignment

Phylogenetic tree

Motif and Domain Analyses

Gene structure Analysis

Physiochemical Properties

Structural Characterizations

Results

Multiple Sequence Alignment

Physiochemical Analysis

Phylogenetic Analysis

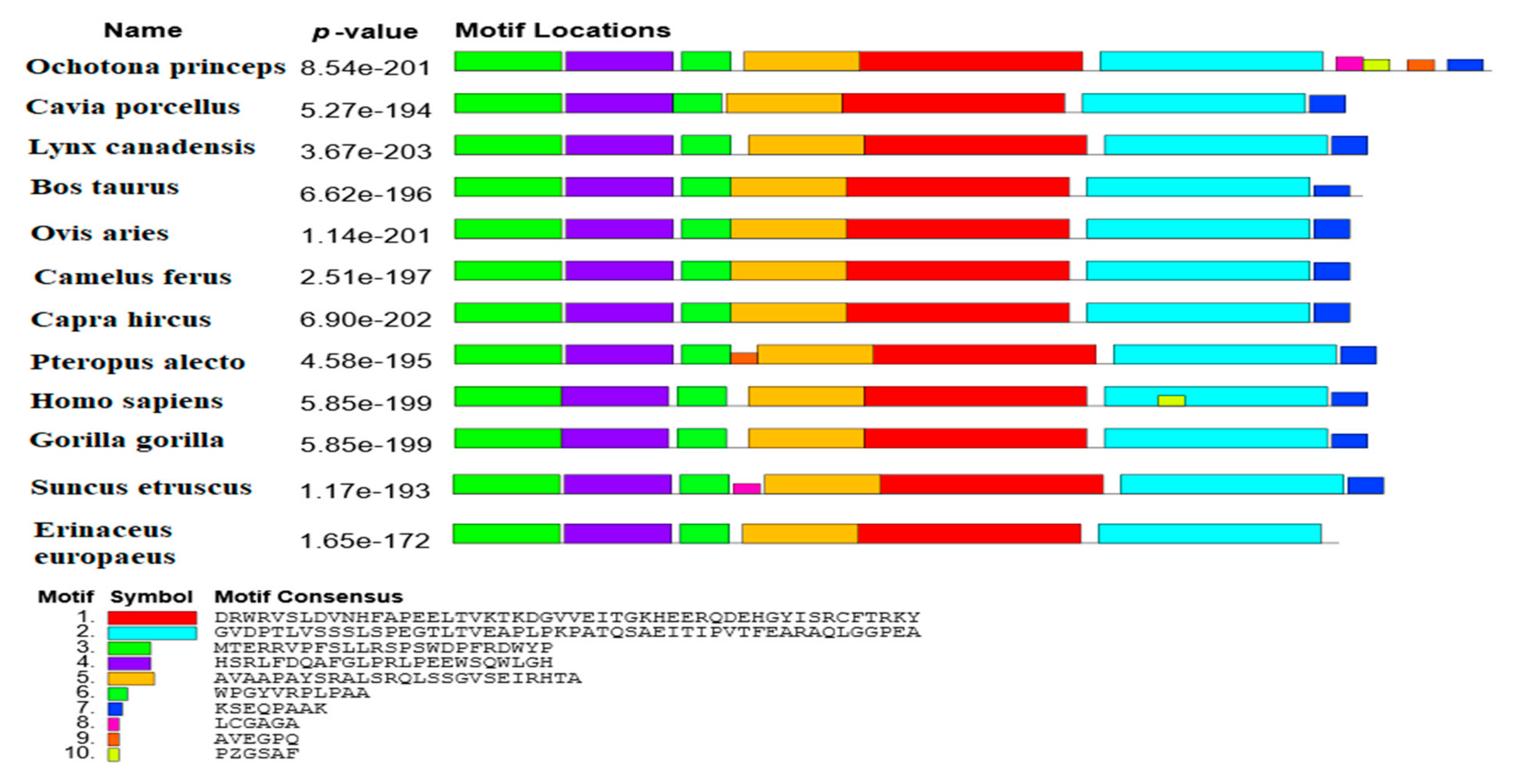

Motif Analysis

Domain Analysis

Gene Structure Analysis

Percentage Identity and Similarity of HSPB1 Gene

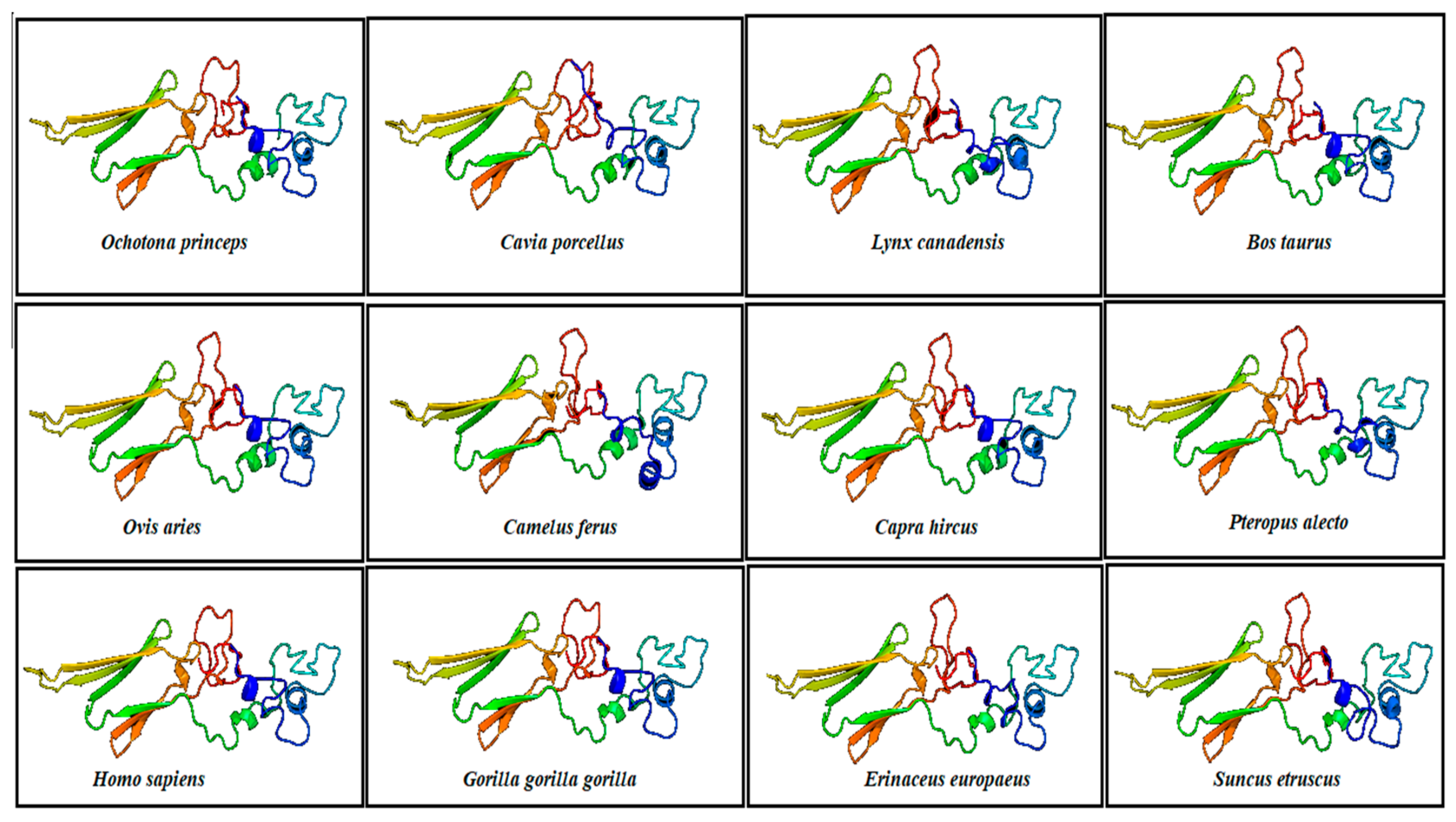

Structural Analysis

Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mymrikov, E.V., A.S. Seit-Nebi, and N.B. Gusev, Large Potentials of Small Heat Shock Proteins. Physiological Reviews, 2011. 91(4): p. 1123-1159.

- Russo Krauss, I., et al., An Overview of Biological Macromolecule Crystallization. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2013. 14(6): p. 11643-11691.

- Salahuddin, P., et al., Structure of amyloid oligomers and their mechanisms of toxicities: Targeting amyloid oligomers using novel therapeutic approaches. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2016. 114: p. 41-58.

- Eyles, S.J. and L.M. Gierasch, Nature’s molecular sponges: Small heat shock proteins grow into their chaperone roles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2010. 107(7): p. 2727-2728.

- Jaspard, E. and G. Hunault, sHSPdb: a database for the analysis of small Heat Shock Proteins. BMC Plant Biology, 2016. 16(1): p. 135.

- Feng, P., et al., Classifying the superfamily of small heat shock proteins by using g-gap dipeptide compositions. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2021. 167: p. 1575-1578.

- Acunzo, J., M. Katsogiannou, and P. Rocchi, Small heat shock proteins HSP27 (HspB1), αB-crystallin (HspB5) and HSP22 (HspB8) as regulators of cell death. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 2012. 44(10): p. 1622-1631.

- Bakthisaran, R., R. Tangirala, and C.M. Rao, Small heat shock proteins: Role in cellular functions and pathology. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics, 2015. 1854(4): p. 291-319.

- Borgo, C., et al., Protein kinase CK2: a potential therapeutic target for diverse human diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2021. 6(1): p. 183.

- Bolhassani, A. and E. Agi, Heat shock proteins in infection. Clinica Chimica Acta, 2019. 498: p. 90-100.

- Mebarek, S., et al., Phospholipases of Mineralization Competent Cells and Matrix Vesicles: Roles in Physiological and Pathological Mineralizations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2013. 14(3): p. 5036-5129.

- Coordinators, N.R., Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Research, 2015. 44(D1): p. D7-D19.

- McDonald, E.T., et al., Sequence, Structure, and Dynamic Determinants of Hsp27 (HspB1) Equilibrium Dissociation Are Encoded by the N-Terminal Domain. Biochemistry, 2012. 51(6): p. 1257-1268.

- Baharum, S. and A.w.A. Nurdalila, Phylogenetic Relationships of Epinephelus fuscoguttatus and Epinephelus hexagonatus Inferred from Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Gene Sequences using Bioinformatic Tools. International Journal of Bioscience, Biochemistry and Bioinformatics, 2011. 1(1): p. 47.

- Bailey, T.L., et al., The value of position-specific priors in motif discovery using MEME. BMC Bioinformatics, 2010. 11(1): p. 179.

- Blum, M., et al., The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Research, 2020. 49(D1): p. D344-D354.

- Iqbal Qureshi, A.M., et al., Insilco identification and characterization of superoxide dismutase gene family in Brassica rapa. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 2021. 28(10): p. 5526-5537.

- Sahay, A., A. Piprodhe, and M. Pise, In silico analysis and homology modeling of strictosidine synthase involved in alkaloid biosynthesis in catharanthus roseus. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, 2020. 18(1): p. 44.

- CoSec: a hub of online tools for comparing secondary structure elements. International Journal of Bioinformatics Research and Applications, 2023. 19(1): p. 56-69.

- Kurashova, N.A., I.M. Madaeva, and L.I. Kolesnikova, Expression of HSP70 Heat-Shock Proteins under Oxidative Stress. Advances in Gerontology, 2020. 10(1): p. 20-25.

- Sultana, M., et al., In silico molecular characterization of TGF-β gene family in Bufo bufo: genome-wide analysis. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics: p. 1-15.

- Su, J., et al., Comparative evolutionary and molecular genetics based study of Buffalo lysozyme gene family to elucidate their antibacterial function. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2023. 234: p. 123646.

- Akbari Rokn Abadi, S., et al., An accurate alignment-free protein sequence comparator based on physicochemical properties of amino acids. Scientific Reports, 2022. 12(1): p. 11158.

- Hassan, F.-u., et al., Genome-wide identification and evolutionary analysis of the FGF gene family in buffalo. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 2024. 42(19): p. 10225-10236.

- Lee, D., O. Redfern, and C. Orengo, Predicting protein function from sequence and structure. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2007. 8(12): p. 995-1005.

- Amrhein, S., et al., Molecular Dynamics Simulations Approach for the Characterization of Peptides with Respect to Hydrophobicity. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2014. 118(7): p. 1707-1714.

- as, J.K., et al., Mapping sequence to feature vector using numerical representation of codons targeted to amino acids for alignment-free sequence analysis. Gene, 2021. 766: p. 145096.

- M. F. Khan et al., “Evolution and comparative genomics of the transforming growth factor-β-related proteins in Nile tilapia,” Mol Biotechnol, pp. 1–15, 2024.

- S. Parveen, M. F. Khan, M. Sultana, S. ur Rehman, and L. Shafique, “Molecular characterization of doublesex and Mab-3 (DMRT) gene family in Ctenopharyngodon idella (grass carp),” J Appl Genet, pp. 1–12, 2024.

| Species | Protein-ID | Length | Database | Accession-ID | Database |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ochotona princeps | XP_004587250.1 | 233 | NCBI | XM_004587193.1 | NCBI |

| Cavia porcellus | XP_003470158.1 | 200 | NCBI | XM_003470110.4 | NCBI |

| Lynx Canadensis | XP_030157330.1 | 205 | NCBI | XM_030301470.1 | NCBI |

| Bos Taurus | NP_001020740.1 | 204 | NCBI | NM_001025569.1 | NCBI |

| Ovis aries | XP_027817273.1 | 201 | NCBI | XM_027961472.2 | NCBI |

| Camelus ferus | XP_032315487.1 | 201 | NCBI | XM_032459596.1 | NCBI |

| Capra hircus | XP_017896392.1 | 201 | NCBI | XM_018040903.1 | NCBI |

| Pteropus Alecto | XP_006918629.1 | 207 | NCBI | XM_006918567.3 | NCBI |

| Homo sapiens | NP_001531.1 | 205 | NCBI | NM_001540.5 | NCBI |

| Gorilla gorilla | XP_004045665.1 | 205 | NCBI | XM_004045617.3 | NCBI |

| Erinaceus europaeus | XP_007518007.1 | 199 | NCBI | XM_007517945.2 | NCBI |

| Suncus etruscus | XP_049643837.1 | 209 | NCBI | XM_049787880.1 | NCBI |

| Species | AA length | Molecular Weight | Theoretical PI | Instability index | Aliphatic index | Gravy | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ochotona princeps | 233 | 25476.85 | 6.60 | 58.61 | 77.47 | -0.289 | Mitochondria |

| Cavia porcellus | 200 | 22284.03 | 6.12 | 61.85 | 68.25 | -0.562 | Nuclear |

| Lynx Canadensis | 205 | 22720.55 | 6.23 | 65.03 | 67.61 | -0.524 | Mitochondria |

| Bos Taurus | 204 | 22679.34 | 5.77 | 59.53 | 69.36 | -0.597 | Mitochondria |

| Ovis aries | 201 | 22334.03 | 6.22 | 63.46 | 70.40 | -0.568 | Nuclear |

| Camelus ferus | 201 | 22410.17 | 6.09 | 65.52 | 70.85 | -0.551 | Nuclear |

| Capra hircus | 201 | 22349.00 | 6.22 | 62.71 | 68.46 | -0.604 | Nuclear |

| Pteropus alecto | 207 | 22853.71 | 6.32 | 73.49 | 66.43 | -0.549 | Nuclear |

| Homo sapiens | 205 | 22782.52 | 5.98 | 62.82 | 68.54 | -0.567 | Nuclear |

| Gorilla gorilla | 205 | 22782.52 | 5.98 | 62.82 | 68.54 | -0.567 | Nuclear |

| Erinaceus europaeus | 199 | 22032.94 | 6.08 | 68.37 | 75.43 | -0.438 | Nuclear & <break/>Mitochondria |

| Suncus etruscus | 209 | 22988.85 | 6.22 | 69.20 | 65.84 | -0.492 | Nuclear & <break/>Mitochondria |

| Organism Name | Homologous Super family<break/>HSP20_like_Chaperone<break/>IPR008978 | Domain 1<break/>ACD_HSPB1<break/> IPR037876 | Domain 2<break/>A Crystalline<break/>IPR002068 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ochotona princeps | 69-189 | 83-168 | 75-183 |

| Cavia porcellus | 62-187 | 79-164 | 71-179 |

| Lynx canadensis | 69-191 | 76-184 | 84-169 |

| Bos Taurus | 67-187 | 72-180 | 80-165 |

| Ovis aries | 67-187 | 72-180 | 80-165 |

| Camelus ferus | 65-187 | 80-165 | 72-180 |

| Capra hircus | 67-187 | 72-180 | 80-165 |

| Pteropus alecto | 72-193 | 78-186 | 86-171 |

| Homo sapiens | 69-197 | 84-169 | 76-184 |

| Gorilla gorilla | 69-197 | 84-169 | 76-184 |

| Erinaceus europaeus | 69-190 | 83-168 | 75-183 |

| Suncus etruscus | 69-190 | 83-168 | 75-183 |

| Ochotona princeps | Cavia porcellus | Lynx Canadensis | Bos taurus | Ovis aries | Camelus ferus | Capra hircus | Pteropus alecto | Homo sapiens | Gorilla gorilla | Erinaceus europaeus | Suncus etruscus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ochotona princeps | 100% | 76.56% | 81.58% | 75.31% | 76.98% | 76.15% | 76.56% | 75.73% | 76.15% | 76.15% | 71.54% | 75.31% |

| Cavia porcellus | 76.56% | 100% | 92.46% | 88.28% | 90.79% | 92.05% | 91.21% | 87.44% | 88.28% | 88.28% | 81.58% | 86.19% |

| Lynx canadensis | 81.58% | 92.46% | 100% | 89.12% | 92.05% | 91.21% | 91.63% | 90.37% | 90.37% | 90.37% | 83.68% | 89.53% |

| Bos taurus | 75.31% | 88.28% | 89.12% | 100% | 96.65% | 93.3% | 96.23% | 85.35% | 86.19% | 86.19% | 79.91% | 82.84% |

| Ovis aries | 76.98% | 90.79% | 92.05% | 96.65% | 100% | 95.81% | 99.58% | 87.86% | 89.12% | 89.12% | 82% | 85.77% |

| Camelus ferus | 76.15% | 92.05% | 91.21% | 93.3% | 95.81% | 100% | 95.39% | 89.53% | 87.86% | 87.86% | 82.42% | 85.35% |

| Capra hircus | 76.56% | 91.21% | 91.63% | 96.23% | 99.58% | 95.39% | 100% | 87.44% | 89.53% | 89.53% | 81.58% | 86.19% |

| Pteropus alecto | 75.73% | 87.44% | 90.37% | 85.35% | 87.86% | 89.53% | 87.44% | 100% | 89.12% | 89.12% | 83.68% | 89.12% |

| Homo sapiens | 76.15% | 88.28% | 90.37% | 86.19% | 89.12% | 87.86% | 89.53% | 89.12% | 100% | 100% | 82.42% | 88.7% |

| Gorilla gorilla | 76.15% | 88.28% | 90.37% | 86.19% | 89.12% | 87.86% | 89.53% | 89.12% | 100% | 100% | 82.42% | 88.7% |

| Erinaceus europaeus | 71.54% | 81.58% | 83.68% | 79.91% | 82% | 82.42% | 81.58% | 83.68% | 82.42% | 82.42% | 100% | 82.84% |

| Suncus etruscus | 75.31% | 86.19% | 89.53% | 82.84% | 85.77% | 85.35% | 86.19% | 89.12% | 88.7% | 88.7% | 82.84% | 100% |

| Ochotona princeps | Cavia porcellus | Lynx canadensis | Bos taurus | Ovis aries | Camelus ferus | Capra hircus | Pteropus alecto | Homo sapiens | Gorilla gorilla | Erinaceus europaeus | Suncus etruscus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ochotona princeps | 100% | 75.73% | 80.33% | 74.47% | 75.73% | 75.73% | 75.31% | 76.56% | 75.73% | 75.73% | 71.12% | 76.56% |

| Cavia porcellus | 75.73% | 100% | 78.66% | 74.89% | 76.15% | 78.24% | 76.56% | 75.73% | 75.73% | 75.73% | 69.45% | 75.31% |

| Lynx canadensis | 80.33% | 78.66% | 100% | 76.15% | 77.82% | 77.82% | 77.4% | 78.24% | 77.4% | 77.4% | 71.12% | 77.82% |

| Bos taurus | 74.47% | 74.89% | 76.15% | 100% | 82% | 79.49% | 81.58% | 74.89% | 74.47% | 74.47% | 68.2% | 73.22% |

| Ovis aries | 75.73% | 76.15% | 77.82% | 82% | 100% | 80.75% | 83.68% | 76.15% | 76.15% | 76.15% | 69.03% | 74.89% |

| Camelus ferus | 75.73% | 78.24% | 77.82% | 79.49% | 80.75% | 100% | 80.33% | 76.98% | 75.73% | 75.73% | 69.45% | 75.31% |

| Capra hircus | 75.31% | 76.56% | 77.4% | 81.58% | 83.68% | 80.33% | 100% | 75.73% | 76.56% | 76.56% | 68.61% | 75.31% |

| Pteropus alecto | 76.56% | 75.73% | 78.24% | 74.89% | 76.15% | 76.98% | 75.73% | 100% | 78.24% | 78.24% | 72.38% | 78.66% |

| Homo sapiens | 75.73% | 75.73% | 77.4% | 74.47% | 76.15% | 75.73% | 76.56% | 78.24% | 100% | 85.77% | 70.71% | 78.66% |

| Gorilla gorilla | 75.73% | 75.73% | 77.4% | 74.47% | 76.15% | 75.73% | 76.56% | 78.24% | 85.77% | 100% | 70.71% | 78.66% |

| Erinaceus europaeus | 71.12% | 69.45% | 71.12% | 68.2% | 69.03% | 69.45% | 68.61% | 72.38% | 70.71% | 70.71% | 100% | 73.22% |

| Suncus etruscus | 76.56% | 75.31% | 77.82% | 73.22% | 74.89% | 75.31% | 75.31% | 78.66% | 78.66% | 78.66% | 73.22% | 100% |

| Organism Name | Alpha helix | Beta Bridge | Beta Turn | Extended strand | Random Coil |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ochotona princeps | 26.61% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 14.16% | 59.23% |

| Cavia porcellus | 21.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 11.00% | 68.00% |

| Lynx Canadensis | 26.83% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 12.20% | 60.98% |

| Bos Taurus | 21.08% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 17.75% | 61.27% |

| Ovis aries | 20.90% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 14.93% | 64.18% |

| Camelus ferus | 19.90% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 16.40% | 63.68% |

| Capra hircus | 20.90% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 12.94% | 66.17% |

| Pteropus Alecto | 18.36% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 13.53% | 68.12% |

| Homo sapiens | 13.66% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 13.17% | 73.17% |

| Gorilla gorilla | 13.66% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 13.17 | 73.17% |

| Erinaceus europaeus | 16.58% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 17.59% | 65.83% |

| Suncus etruscus | 18.66% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 12.44% | 68.90% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).