1. Introduction

Maintaining balance is a complex process requiring the integration of multiple sensory, motor, and cognitive systems (Nashner, 2014; Nazrien et al., 2024). Central to this integration is cognitive processing, which encompasses the acquisition, analysis, storage, and retrieval of information (Lawlor, 2002). Executive function, a domain of cognition, encompasses goal-oriented behaviours, decision-making, and response inhibition, while processing speed relates to the rapid detection and response to stimuli, both of which can play a role in stabilizing posture during activities (Chantanachai et al., 2022; Muir-Hunter et al., 2014).

The majority of studies linking cognition and balance have focused on older adults (Divandari et al., 2023; Gatto et al., 2020; Heaw et al., 2022; Li et al., 2018). However, this raises a critical question: are these associations a direct reflection of the interplay between cognitive and sensorimotor systems, or are they merely a consequence of concurrent declines due to aging? Investigating the relationship between cognition and balance in young adults, who have yet to experience significant age-related cognitive or sensorimotor decline, seems essential. Previous studies on young athletes have suggested that cognitive processes such as reaction time and executive control are correlated with sport-specific motor skills, further indicating that cognition may be critical for maintaining proper balance (Furley, 2023; Kalén et al., 2021; Porter et al., 2022) However, the extent to which baseline cognitive functions influence balance in non-athletic, healthy young adults remains unclear.

Previous research has demonstrated that performing a cognitive and balance task simultaneously (dual-tasking) tends to affect dynamic postural stability (Talarico et al., 2017; Westwood et al., 2020). While these findings underscore the influence of cognitive processes on balance, focusing solely on dual-task performance may overlook important insights into how baseline cognitive abilities contribute to maintaining stability in everyday situations.

Additionally, research shows the association between cognition and sports performance and balance among athletes (Kalén et al., 2021; Trecroci et al., 2021) who often benefit from extensive training that optimizes their cognitive and motor skills (Gutiérrez-Capote et al., 2024). However, this focus limits our ability to generalize findings to the broader young adult population. Studying non-athletic, healthy young adults allows us to better understand the natural, untrained relationship between cognition and dynamic balance.

Understanding this relationship has important implications for clinical practice and preventative strategies. Identifying cognitive domains that correlate with balance in young adults could serve as biomarkers, offering valuable insights into their ability to predict balance performance. This understanding could facilitate the early identification of balance-related issues, leading to the development of targeted interventions and training programs to improve stability across the lifespan. If cognitive domains are confirmed to play a crucial role in maintaining balance during youth, early cognitive training could be a proactive strategy to prevent future balance impairments and promote long-term physical well-being.

The primary aims of this study are: 1. to examine the potential association between different cognitive domains and dynamic balance in young non-athletic people; 2. To determine which cognitive domain significantly predicts dynamic balance after accounting for confounding factors; 3. To investigate the correlation between common confounders and cognitive and balance functions.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

This observational, cross-sectional study involved 62 healthy young adults aged 18- to 50-year-old. A physiotherapist conducted the data collection over a 90-minute session. Participants were excluded if they had any neurological, psychological, orthopedic, or cardiorespiratory issues, or experienced pain that might affect their ability to stand or walk. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from Monash University and University of Tasmania, and informed consent was obtained from all participants following a comprehensive explanation of the study procedures. Participation was entirely voluntary, with participants having the freedom to withdraw at any point.

Measurements

Demographic information such as age, gender, education level, and history of falls or injuries was recorded (see

Table 1). Body Mass Index (BMI) was measured using bioelectrical impedance technology (Seca 804 Flat Scale with Chromed Electrodes).

Cognitive assessments were completed before the balance tests, with the sequence of cognitive tests being randomized. Participants selected a random number between 1 and 4 to determine the starting point, and this process was repeated for each cognitive test that followed. After completing all cognitive assessments, the balance tests were then conducted in a randomized order.

Cognitive Tests

PsyToolkit was used for conducting domain-specific cognitive tests (Kim et al., 2019; Stoet, 2010). This is a freely accessible, web-based platform which is highly effective for conducting both general and psycholinguistic experiments (Stoet, 2017). It is an effective approach for conducting both general and psycholinguistic experiments involving complex reaction time tasks, with findings consistently replicating for both response selection and reaction time (Kim et al., 2019). Tests are as follows:

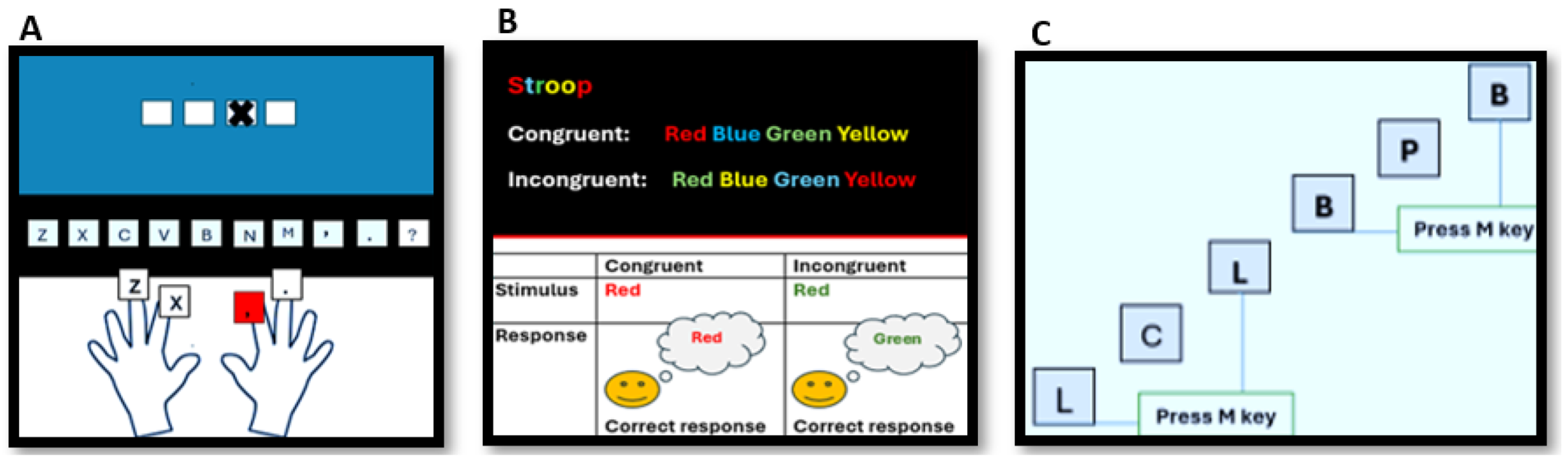

Deary-Liewald reaction time task:The Deary-Liewald reaction time task evaluated reaction time by displaying four white squares on a computer screen, each corresponding to a specific key: 'z,' 'x,' 'comma,' and 'period (Deary et al., 2011). Participants were instructed to promptly press the corresponding key whenever a cross appeared in one of the squares, which would cause the cross to vanish and trigger the appearance of the next one (

Figure 1, A). The median reaction times, measured in milliseconds, were used for subsequent data analysis (Deary et al., 2011). The Deary-Liewald Reaction Time Task is a valid and reliable measure of processing speed, demonstrating high test-retest reliability and strong correlations with established reaction time tasks (Deary et al., 2011; Ferreira et al., 2021)

Stroop Color–Word Test: This test assesses the capacity to inhibit cognitive interference (Stroop, 1935). Participants were asked to quickly name the colour of words displayed on a computer screen. The test presented both congruent (matching) and incongruent (non-matching) conditions (

Figure 1, B). Reaction times during the incongruent conditions were analysed to assess interference effects (Periáñez et al., 2020). The Stroop Color-Word Test is a widely used measure of cognitive inhibition, which has shown high test-retest reliability and good internal consistency (Jensen & Rohwer Jr, 1966; Siegrist, 1995; Strauss et al., 2005).

N-Back Test: The N-Back Test assesses working memory function (Kirchner, 1958). During the test, participants are presented with a sequence of letters and must determine whether the current letter matches the one shown in three positions earlier (

Figure 1C). The rate of correct responses is recorded and analysed (Gajewski et al., 2018). The N-back task is a widely used measure of working memory. Previous research has reported moderate test-retest reliability for accuracy scores, particularly in more difficult task levels (Hockey & Geffen, 2004). N-2 back task was used to assess working memory, as previous research suggests that more difficult working memory tasks show higher test-retest reliability (Dai et al., 2019).

Balance Tests

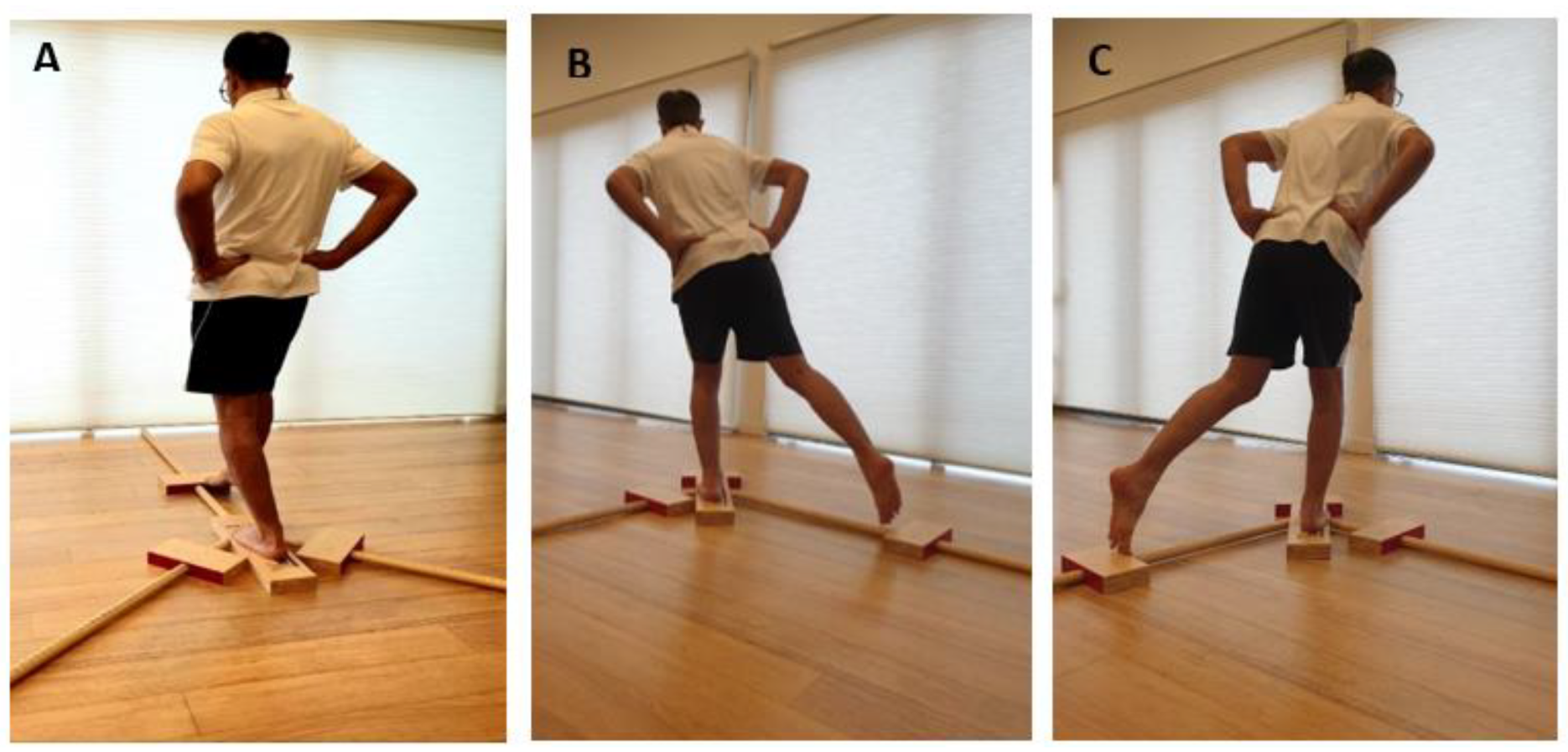

The Y Balance Test (YBT) is a valid and reliable tool for assessing dynamic balance (Plisky et al., 2009; Sipe et al., 2019). The reliability and validity of this test were already checked among young in a systematic review (Powden et al., 2019). Participants stood barefoot on a central footplate with their hands resting on their hips, using their dominant leg to push a block in three specific directions: anterior, posteromedial, and posterolateral, while balancing on their non-dominant leg. Each direction was tested three times, and the average reach distance was calculated for each direction (Sipe et al., 2019). Reach distances were measured to the nearest 0.5 cm, following a consistent sequence: dominant-leg anterior (

Figure 2A), posteromedial (

Figure 2B), and posterolateral (

Figure 2, C). Trials were considered invalid if participants failed to return to the starting position, pushed the block with additional kicks, or stepped on the indicator (Sipe et al., 2019). To calculate the normalized score, the sum of the three reach distances is divided by three times the limb length and multiplied by 100. The YBT-LQ composite score is the average of these normalized scores (Sipe et al., 2019). Limb length is measured from the anterosuperior iliac spine to the medial malleolus while the participant lies supine (Sipe et al., 2019)

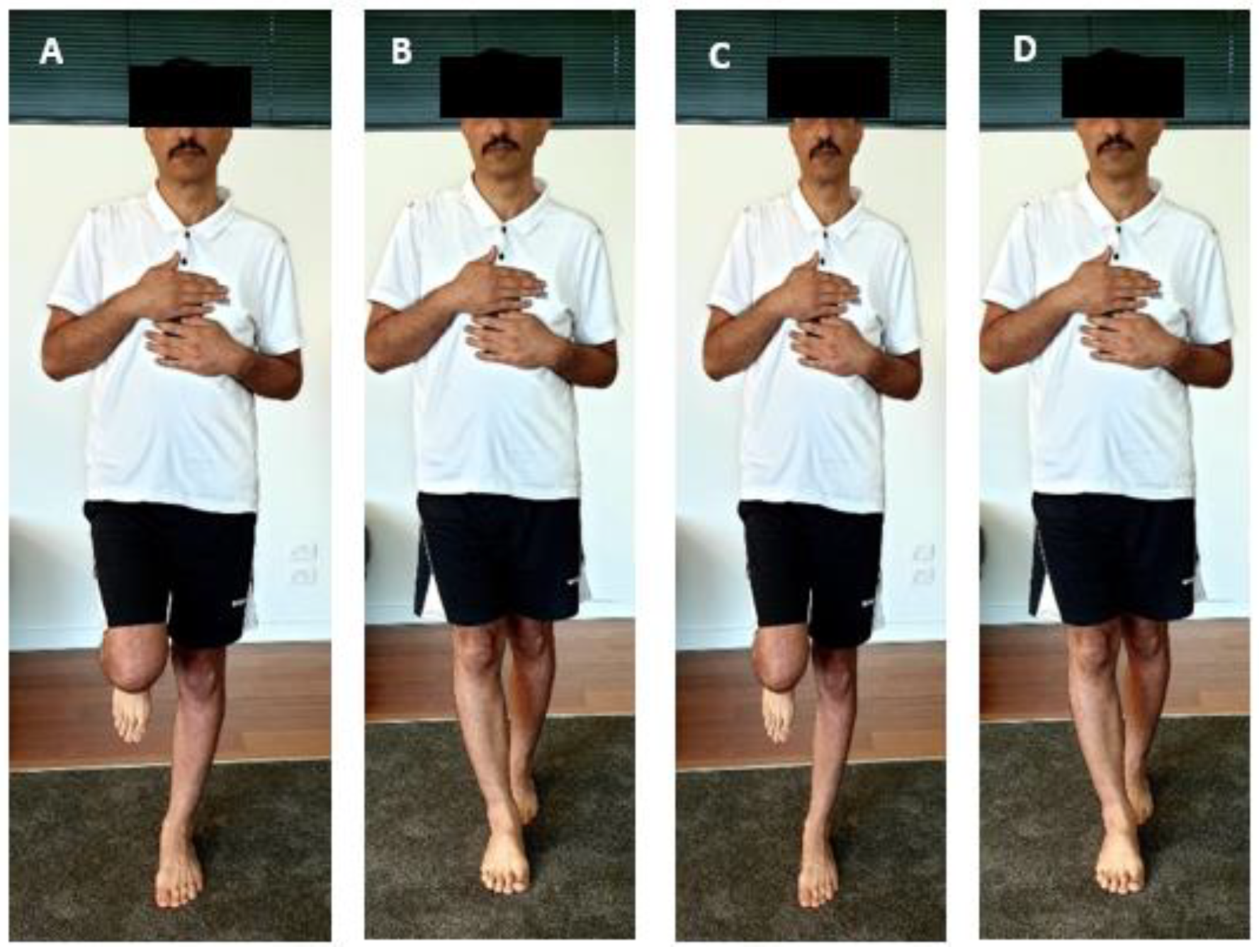

The static balance test was conducted using the Sway Balance Mobile Application (SWAY; Sway Medical, Tulsa, OK) (Vincenzo et al., 2016). This FDA-approved, reliable, and validated method assesses postural stability through accelerometers (Jeremy et al., 2014). Its validity and reliability were tested in the previous studies (R. Amick et al., 2015; Burghart et al., 2017; Dunn et al., 2016). Participants held the device at their sternum, and the accelerometers recorded movement during single-leg (

Figure 2A) and tandem (

Figure 2B) stances, both with eyes open and closed. The app converted the data into balance scores ranging from 0 to 100, with lower scores reflecting poorer balance (

Figure 2C and 2D) (Amick et al., 2013). Each test comprised a practice trial and three repetitions, with the average score calculated. Positions were timed for 10 seconds with a 3-second countdown. (Vincenzo et al., 2016).

Data Management and Analysis

Initially, a descriptive analysis was performed on the demographic data of all participants. Normality of quantitative variables was assessed, which helped determine the appropriate statistical tests (parametric or nonparametric) to be applied. To evaluate the size and direction of linear relationships between variables, bivariate correlations were conducted for each pair of variables (Gatto et al., 2020). Before conducting these correlations, the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity were assessed to ensure the validity of the analysis (Tabachnick, 2019). A confidence level of 95% was used for all analyses, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS statistical package (version 24.0). All data with the exception of Stroop incongruent time was normally distributed (Gatto et al., 2020) (

Table 2). BMI and age were identified as a potential confounder for inclusion in the regression models for YBT and gender as a potential confounder for static balance tests, as it showed significant correlations with balance variable compared to other variables. Therefore, partial correlation was conducted to check the relationship between cognitive domains and balance tests controlled for those confounders. To make sure that cognition significantly does not contribute to the variance in balance beyond the effect of those confounders, hierarchical multiple regression analysis (MRA) was performed (p<0.05, 0.01, & 0.001) (Tabachnick, 2019). The analysis comprised three models, with the process repeated for each cognitive domain in relation to the balance tests. In the first step, confounders were entered as a predictor. In the second step, individual cognitive domains were added to assess whether that cognitive domain can significantly increase the explained variance (indicated by a significant change in R²) of the model (Tabachnick, 2019). Before interpreting the MRA results, various assumptions were tested. Stem-and-leaf plots and boxplots were utilized to check for normal distribution and the absence of univariate outliers among the regression variables. Normal probability plots of standardized residuals and scatterplots of standardized residuals versus standardized predicted values were examined to ensure the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity of residuals were met (Tabachnick, 2019). The required sample size was calculated using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007).

3. Results

3.1. Participants:

The sample consisted of 62 participants with a median age of 35.5 years (ranging from 18-50) and a median BMI of 2 (ranging from 19.4-40.9). The sample was 60 % female, and 56.5% had tertiary education (

Table 1). Baseline cognitive and balance test results are detailed in

Table 2.

3.2. Association of Demographic Information with Cognitive and Balance Measures

The correlation analysis revealed significant associations between BMI and the YBT in all three directions, though no significant associations were observed with cognitive domains. Age demonstrated a significant association with processing speed and inhibition, but no significant associations were found with working memory or the YBT, except for the YBT Posteromedial (PM) direction. Education level did not show any significant association with the YBT across any direction or average score; however, a significant association was noted with processing speed, with no associations observed for inhibition or working memory. Gender was significantly associated with the average YBT score and the YBT in the posteromedial direction, as well as with inhibition, while no associations were found with other measures (

Table 2). The correlation analysis shows that static balance measures (SLS EC, Tandem EO, Tandem EC) have varying relationships with demographic information. Gender is significantly associated with Tandem EO and SLS EC, while age and BMI show no significant correlations with these measures.

3.3. Association Between Cognition and Balance Measures

All cognitive measures including inhibition, working memory, and processing speed showed no significant association with none of static or dynamic balance tests. Descriptive statistics for cognitive domains and balance test results and their correlations with cognitive domains are provided in

Table 3 and 4.

3.4. Cognitive Domains Predicting Postural Balance

Simple associations alone are not sufficient evidence for functional relationships (Rabbitt et al., 2006). To establish a functional relationship and determine which cognitive domain significantly contributes to the variance in dynamic balance beyond the effect of BMI hierarchical multiple regression analyses (MRA) were conducted. First, MRA was performed to predict balance scores based on BMI, calculating the initial R² values. Next, cognitive scores were added to each model to compute new R² values. The significance of the changes in R² was assessed to determine whether cognitive scores accounted for additional variance in balance test scores. In the first step of the hierarchical MRA, BMI accounted for a significant variance in compliance. In the second step, none of the cognitive domains contributed significant additional variance for none of our balance tests, a part of the results are reported in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the associations of cognitive domains, inhibition, working memory, and processing speed with dynamic and static postural balance among young adults. We also aimed to determine which cognitive domain contributes significantly to the variance in postural balance beyond the effect of confounders. Contrary to findings often seen in older adults, the results indicated no significant association between these cognitive domains and postural balance measures in the younger adults.

The lack of a detectable correlation between cognitive functions and balance in young adults aligns with the findings of Stuhr and colleagues, who also observed no significant associations between any of their cognitive domain tasks, including processing speed, inhibition, and working memory, and the Star Excursion Balance Test among young adults. This similarity in results further supports the notion that, in young adults, postural balance may be maintained through mechanisms less reliant on higher-order cognitive processes (Stuhr et al., 2020). The results may be attributable to the high level of motor skill automation observed in this age group. Automation refers to the ability to perform skilled tasks without conscious executive control, a process that reduces cognitive load and allows for efficient movement control (Poldrack et al., 2005).

In young adults, sensorimotor performance is probably highly automated, which enhances the specificity of movement control while minimizing the need for cognitive resources (Schedler et al., 2021; Stuhr et al., 2020). This high level of automaticity suggests that young adults rely less on top-down cognitive processes to maintain balance compared to older adults. Previous studies have shown the association of balance and cognition among older adults (Divandari et al., 2023). Older adults have greater difficulty achieving automaticity (Rogers et al., 1994), which can lead to increased reliance on cognitive resources for balance tasks. Individuals with more automatic and efficient movement control such as young adults, rely less on higher-order cognitive processes for balance maintenance (Schedler et al., 2021). This could explain why older adults demonstrate stronger associations between cognitive domains and balance, whereas young adults do not. The ability to automate sensorimotor tasks reduces the cognitive load required for balance, potentially leading to a diminished influence of cognitive domains on dynamic balance performance (Sakamoto & Iguchi, 2018). The lack of significant associations between cognitive measures and balance in young adults suggests that their ability to maintain balance relies more on automated motor responses rather than on higher-order cognitive processing. This supports the idea that cognitive-motor performance in young adults is largely automatized, reducing the need for top-down cognitive control in this age group (Stuhr et al., 2020). Motor performance has been shown to progress from early childhood to early adulthood, involving both qualitative (efficient movement pattern) and quantitative (greater smoothness, faster time to peak velocity, and better motor planning) advancements (Stöckel & Hughes, 2015). Similarly, executive functions mature from childhood through adolescence and into early adulthood, primarily due to the maturation of the frontal lobes and other critical brain areas, as well as increased volumes of cortical white and grey matter (Huizinga et al., 2006).

Interestingly, the absence of a discernible relationship between cognitive functions and postural balance in young adults can also be contextualized through the lens of task complexity. As noted by Vuillerme and Nougier (2004), attentional demands for postural control intensify with increasing task difficulty, suggesting that balance tasks require more cognitive input when complexity escalates (Lajoie et al., 1993). For example, it has been shown that if the balance task becomes more challenging, the reaction time obtained while maintaining the equilibrium becomes longer (Vuillerme & Nougier, 2004). Aging necessitates allocating a greater share of attentional resources to meet the balance demands of postural tasks (Lajoie et al., 1996). However, given the typically higher level of motor skill automation in young adults, these tasks may not impose sufficient cognitive strain to reveal meaningful associations between cognitive functions and balance. Therefore, the reason for relatively easy performing dynamic balance tasks by young adults stems from their ability to execute movements with minimal conscious effort, thereby reducing the need for higher-order cognitive involvement (Schedler et al., 2021).

The correlation analysis demonstrated significant associations between BMI and performance on the Y Balance Test (YBT) in all three directions. This result is consistent with findings from other studies, which have reported that young adults with overweight or obesity tend to exhibit poorer dynamic balance performance compared to their normal-weight peers (Alice et al., 2022; Do Nascimento et al., 2017). Weight gain can alter body shape and posture, shifting the center of gravity (COG) anteriorly relative to the base of support (BOS), making balance maintenance more challenging (Porto et al., 2012). As BMI increases, changes in body structure impact balance, with excessive fat accumulation often leading to impaired equilibrium (Alice et al., 2022). Mocano and colleagues found no significant differences between the overweight student group and the normal weight group in terms of balance performance. However, they proposed that these results might be affected by factors like the students’ field of study, regular participation in physical activities, and involvement in academic or recreational programs, all of which could contribute to improved balance performance in overweight students (Mocanu et al., 2022). This underscores the importance of accounting for physical health factors—such as BMI—when assessing balance performance, since a higher BMI can compromise an individual’s stability by affecting biomechanics and reducing mobility.

Gender differences also emerged in the current findings, with significant associations noted between gender and Y Balance Test and also static balance in the tandem position with eyes open and in single leg stance position with eyes closed which is aligned with findings of the recent meta-analysis (Plisky et al., 2021). This may indicate that other factors, such as differences in physical strength, flexibility, or habitual activity levels, could be more influential on postural balance within this population. Moreover, the association between gender and inhibition could be reflective of inherent differences in response inhibition capabilities, which warrants further exploration.

The findings in this study should be interpreted considering the following limitations. Firstly, while we examined the correlation of sex, age, BMI, education, falls or injury history, and body fat mass on the cognitive and balance functions of young adults, there are other factors that may affect cognition and balance that were not accounted for, such as flat foot (Febriyanti et al., 2024), decreased foot arch, and arthritis changes in lower limbs (John et al., 2024). Secondly, the tests may not be challenging enough to show the relationship between cognitive domains and balance among young adults. While the study incorporated multiple cognitive tests, including the MMSE, Stroop test, and N-back test, it did not account for other potentially influential factors, such as sensory deficits, muscle strength, or unreported medical conditions, which could also affect dynamic balance. Future studies should employ longitudinal designs and include a broader range of physiological and environmental factors and use highly challenging tests to better understand the interplay between cognition and balance.

This study needs to be conducted among a larger sample size and also consider more challenging balance tasks for young adults. It is suggested for future studies longitudinal designs to be employed to establish causal relationships between cognition and balance while expanding to diverse populations, including athletes and young individuals with cognitive impairments, and those with varying health conditions. The absence of a cognitive-balance association in young adults may be due to their highly automated motor skills, which allow them to perform balance tasks with minimal cognitive effort. More challenging assessments, such as dual-task balance tests, neuroimaging techniques, and biomechanical analyses, should be incorporated to detect subtle interactions. By addressing these factors, future research can better elucidate the complex interplay between cognition and balance and inform more effective interventions.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the minimal role of cognitive processes in balance maintenance among young adults, emphasizing the dominance of automated motor skills. Balance interventions might focus on more challenging, task-specific exercises that engage cognitive contributions, such as dual-task or perturbation-based activities. The significant association between BMI and dynamic balance underscores the importance of incorporating physical health factors like weight management and core stability into training. Gender-specific differences in inhibition and balance measures suggest tailored approaches to training, addressing distinct neuromuscular characteristics. While these findings provide valuable insights, future research should further investigate the contributions of sensory and motor systems, the role of cognitive-motor integration in challenging tasks, and the implications for proactive balance training and injury prevention. These areas could refine training protocols to improve outcomes and build resilience against age-related declines in balance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Nahid Divandari, Marie-Louise Bird and Shapour Jaberzadeh; Data curation, Shapour Jaberzadeh; Formal analysis, Nahid Divandari and Shapour Jaberzadeh; Investigation, Nahid Divandari and Shapour Jaberzadeh; Methodology, Nahid Divandari and Shapour Jaberzadeh; Resources, Nahid Divandari and Fefe Vakili; Software, Shapour Jaberzadeh; Supervision, Marie-Louise Bird and Shapour Jaberzadeh; Writing – original draft, Nahid Divandari; Writing – review & editing, Nahid Divandari, Marie-Louise Bird, Maryam Zoghi, Fefe Vakili and Shapour Jaberzadeh.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC) in 2023 and the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) at the University of Tasmania in 2023. The approval numbers assigned are 31380 for MUHREC and 27343 for HREC at the University of Tasmania.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All participants gave their informed consent after receiving thorough information about the study. Participation was voluntary, allowing them the freedom to withdraw at any time.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Tim Power, Consultant in Data Science, AI, and Sensitive Data Platforms at the Monash Research Centre, for his invaluable assistance with the statistical analysis in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| YBT |

Y Balance Test |

| SLS |

Single Leg Stance |

| EO |

Eyes Open |

| EC |

Eyes Closed |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| Ant |

Anterior |

| PL |

Posterolateral |

| PM |

Posteromedial |

References

- Alice, A., Yadav, M., Verma, R., Kumari, M., & Arora, S. (2022). Effect of obesity on balance: A literature review. International journal of health sciences, 6(S4), 3261-3279.

- Amick, R. Z., Patterson, J. A., & Jorgensen, M. J. (2013). Sensitivity of tri-axial accelerometers within mobile consumer electronic devices: a pilot study. Int J Appl, 3(2), 97-100.

- Deary, I. J., Liewald, D., & Nissan, J. (2011). A free, easy-to-use, computer-based simple and four-choice reaction time programme: the Deary-Liewald reaction time task. Behav Res Methods, 43(1), 258-268. [CrossRef]

- Divandari, N., Bird, M. L., Vakili, M., & Jaberzadeh, S. (2023). The Association Between Cognitive Domains and Postural Balance among Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Literature and Meta-Analysis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 23(11), 681-693. [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento, J., Silva, C., Dos Santos, H., de Almeida Ferreira, J., & De Andrade, P. (2017). A preliminary study of static and dynamic balance in sedentary obese young adults: the relationship between BMI, posture and postural balance. Clinical obesity, 7(6), 377-383.

- Febriyanti, I., Setijono, H., Wijaya, F. J. M., & Kusuma, I. D. M. A. W. (2024). Foot health and physical fitness: investigating the interplay among flat feet, body balance, and performance in junior high school students. Pedagogy of Physical Culture and Sports, 28(3), 168-174.

- Ferreira, S., Raimundo, A., del Pozo-Cruz, J., & Marmeleira, J. (2021). Psychometric properties of a computerized and hand-reaction time tests in older adults using long-term facilities with and without mild cognitive impairment. Experimental Gerontology, 147, 111271. [CrossRef]

- Furley, P., Schütz, L.-M., & Wood, G. . (2023). A critical review of research on executive functions in sport and exercise. . International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(3), 501–528. [CrossRef]

- Gatto, N. M., Garcia-Cano, J., Irani, C., Liu, T., Arakaki, C., Fraser, G., Wang, C., & Lee, G. J. (2020). Observed Physical Function Is Associated With Better Cognition Among Elderly Adults: The Adventist Health Study-2. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen, 35, 1533317520960868. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Capote, A., Jiménez-Martínez, J., Madinabeitia, I., de Orbe-Moreno, M., Pesce, C., & Cardenas, D. (2024). Sport as cognition enhancer from childhood to young adulthood: a systematic review focused on sport modality. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 22(2), 395-427.

- Heaw, Y. C., Singh, D. K. A., Tan, M. P., & Kumar, S. (2022). Bidirectional association between executive and physical functions among older adults: A systematic review. Australas J Ageing, 41(1), 20-41. [CrossRef]

- Hockey, A., & Geffen, G. (2004). The concurrent validity and test–retest reliability of a visuospatial working memory task. Intelligence, 32(6), 591-605. [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, M., Dolan, C. V., & van der Molen, M. W. (2006). Age-related change in executive function: developmental trends and a latent variable analysis. Neuropsychologia, 44(11), 2017-2036. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A. R., & Rohwer Jr, W. D. (1966). The Stroop Color-Word Test: A review. Acta Psychologica, 25(1), 36-93. [CrossRef]

- John, J. N., Ugwu, C. O., John, D. O., Okezue, O. C., Mgbeojedo, U. G., & Onuorah, O. C. (2024). Balance confidence and associated factors among patients with knee osteoarthritis. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 40, 500-506. [CrossRef]

- Kalén, A., Bisagno, E., Musculus, L., Raab, M., Pérez-Ferreirós, A., Williams, A. M., Araújo, D., Lindwall, M., & Ivarsson, A. (2021). The role of domain-specific and domain-general cognitive functions and skills in sports performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull, 147(12), 1290-1308. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Gabriel, U., & Gygax, P. (2019). Testing the effectiveness of the Internet-based instrument PsyToolkit: A comparison between web-based (PsyToolkit) and lab-based (E-Prime 3.0) measurements of response choice and response time in a complex psycholinguistic task. PLoS One, 14(9), e0221802. [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, W. K. (1958). Age differences in short-term retention of rapidly changing information. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 55(4), 352-358. [CrossRef]

- Lajoie, Y., Teasdale, N., Bard, C., & Fleury, M. (1993). Attentional demands for static and dynamic equilibrium. Experimental Brain Research, 97(1), 139-144. [CrossRef]

- Lajoie, Y., Teasdale, N., Bard, C., & Fleury, M. (1996). Upright Standing and Gait: Are There Changes in Attentional Requirements Related to Normal Aging? Experimental Aging Research, 22(2), 185-198. [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, P. G. (2002). The panorama of opioid-related cognitive dysfunction in patients with cancer: a critical literature appraisal. Cancer, 94(6), 1836-1853. [CrossRef]

- Li, K. Z. H., Bherer, L., Mirelman, A., Maidan, I., & Hausdorff, J. M. (2018). Cognitive Involvement in Balance, Gait and Dual-Tasking in Aging: A Focused Review From a Neuroscience of Aging Perspective. Front Neurol, 9, 913. [CrossRef]

- Mocanu, G., Murariu, G., & Onu, I. (2022). The Influence of BMI Levels on the Values of Static and Dynamic Balance for Students (Men) of the Faculty of Physical Education and Sports. Journal of Men's Health, 18, 156. [CrossRef]

- Nashner, L. M. (2014). Practical biomechanics and physiology of balance. Balance function assessment and management, 431.

- Nazrien, N., Prabowo, T., & Arisanti, F. (2024). The Role of Cognition in Balance Control. OBM Neurobiology, 8(1), 1-12.

- Periáñez, J. A., Lubrini, G., García-Gutiérrez, A., & Ríos-Lago, M. (2020). Construct Validity of the Stroop Color-Word Test: Influence of Speed of Visual Search, Verbal Fluency, Working Memory, Cognitive Flexibility, and Conflict Monitoring. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 36(1), 99-111. [CrossRef]

- Plisky, P., Schwartkopf-Phifer, K., Huebner, B., Garner, M. B., & Bullock, G. (2021). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Y-Balance Test Lower Quarter: Reliability, Discriminant Validity, and Predictive Validity. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 16(5), 1190-1209. [CrossRef]

- Plisky, P. J., Gorman, P. P., Butler, R. J., Kiesel, K. B., Underwood, F. B., & Elkins, B. (2009). The reliability of an instrumented device for measuring components of the star excursion balance test. N Am J Sports Phys Ther, 4(2), 92-99.

- Poldrack, R. A., Sabb, F. W., Foerde, K., Tom, S. M., Asarnow, R. F., Bookheimer, S. Y., & Knowlton, B. J. (2005). The Neural Correlates of Motor Skill Automaticity. The Journal of Neuroscience, 25(22), 5356-5364. [CrossRef]

- Porter, K. L. H., Quintana, C., Morelli, N., Heebner, N., Winters, J., Han, D. Y., & Hoch, M. (2022). Neurocognitive function influences dynamic postural stability strategies in healthy collegiate athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 25(1), 64-69. [CrossRef]

- Porto, H. C. D., Pechak, C. M., Smith, D. R., & Reed-Jones, R. J. (2012). Biomechanical Effects of Obesity on Balance. International journal of exercise science, 5, 1.

- Rogers, W. A., Bertus, E. L., & Gilbert, D. K. (1994). Dual-task assessment of age differences in automatic process development. Psychology and Aging, 9(3), 398.

- Schedler, S., Abeck, E., & Muehlbauer, T. (2021). Relationships between types of balance performance in healthy individuals: Role of age. Gait Posture, 84, 352-356. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M. (1995). Reliability of the Stroop Test with Single-Stimulus Presentation. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 81(3_suppl), 1295-1298. [CrossRef]

- Sipe, C. L., Ramey, K. D., Plisky, P. P., & Taylor, J. D. (2019). Y-Balance Test: A Valid and Reliable Assessment in Older Adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 27(5), 663-669. [CrossRef]

- Stöckel, T., & Hughes, C. M. (2015). Effects of multiple planning constraints on the development of grasp posture planning in 6- to 10-year-old children. Dev Psychol, 51(9), 1254-1261. [CrossRef]

- Stoet, G. (2010). PsyToolkit: A software package for programming psychological experiments using Linux. Behavior Research Methods, 42(4), 1096-1104. [CrossRef]

- Stoet, G. (2017). PsyToolkit:A Novel Web-Based Method for Running Online Questionnaires and Reaction-Time Experiments. Teaching of Psychology, 44(1), 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, G. P., Allen, D. N., Jorgensen, M. L., & Cramer, S. L. (2005). Test-Retest Reliability of Standard and Emotional Stroop Tasks: An Investigation of Color-Word and Picture-Word Versions. Assessment, 12(3), 330-337. [CrossRef]

- Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18(6), 643-662. [CrossRef]

- Stuhr, C., Hughes, C. M. L., & Stöckel, T. (2020). The Role of Executive Functions for Motor Performance in Preschool Children as Compared to Young Adults [Original Research]. Frontiers in psychology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G. (2019). Using Multivariate Statistics (7th edition ed.). Published by Pearson.

- Talarico, M. K., Lynall, R. C., Mauntel, T. C., Weinhold, P. S., Padua, D. A., & Mihalik, J. P. (2017). Static and dynamic single leg postural control performance during dual-task paradigms. Journal of sports sciences, 35(11), 1118-1124.

- Trecroci, A., Duca, M., Cavaggioni, L., Rossi, A., Scurati, R., Longo, S., Merati, G., Alberti, G., & Formenti, D. (2021). Relationship between Cognitive Functions and Sport-Specific Physical Performance in Youth Volleyball Players. Brain Sci, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Vincenzo, J. L., Glenn, J. M., Gray, S. M., & Gray, M. (2016). Balance measured by the sway balance smart-device application does not discriminate between older persons with and without a fall history. Aging clinical and experimental research, 28(4), 679-686. [CrossRef]

- Vuillerme, N., & Nougier, V. (2004). Attentional demand for regulating postural sway: the effect of expertise in gymnastics. Brain Research Bulletin, 63(2), 161-165.

- Westwood, C., Killelea, C., Faherty, M., & Sell, T. (2020). Postural stability under dual-task conditions: Development of a post-concussion assessment for lower-extremity injury risk. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 29(1), 131-133.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).