1. Introduction

The global aging population presents significant challenges for maintaining health and well-being in older adults, with increased fall risk being a primary concern (World Health Organization, 2022). Age-related declines in physical activity are associated with cognitive impairments, compromised postural control, and increased vulnerability to geriatric syndromes such as frailty, cognitive decline, and dependency, significantly contributing to decreased quality of life (Falck et al., 2017; Iso-Markku et al., 2024; Thomas et al., 2019). Impairments in cognitive function and balance are well-recognized contributors to fall risk among older adults (Chantanachai et al., 2021; Chantanachai et al., 2022). Dynamic balance, involving complex interactions between sensory inputs, motor control, autonomic reflexes, and cognitive processing, is crucial for preventing falls and maintaining functional independence in aging populations (Bednarczuk & Rutkowska, 2022; Nashner, 2014). Even subtle cognitive declines can negatively impact dynamic postural stability, highlighting the importance of identifying specific cognitive domains most strongly linked to balance impairments (Chantanachai et al., 2022; Muir-Hunter et al., 2014).

While previous research has established correlations between cognitive function and dynamic balance (Divandari et al., 2023; Heaw et al., 2022), identifying precise cognitive predictors remains essential for developing effective, targeted exercise interventions that address aging-related balance deficits. Such interventions are critical for delaying age-associated diseases, reducing fall risks, and promoting functional independence (Hopkins et al., 2023). Identifying cognitive domains that most strongly predict balance could inform tailored exercise interventions, including those leveraging emerging technologies such as wearable devices, sensors, and digital therapeutics to enhance long-term adherence to physical activity and improve health outcomes for older adults.

This study builds on existing evidence by focusing on cognitive-motor interactions underlying dynamic balance using tasks that require higher-order cognitive processing (Stuhr et al., 2018). The Timed Up and Go (TUG) test is a well-established tool for examining the relationship between balance and cognition (Divandari et al., 2023). However, the Y Balance Test (YBT), a multidirectional balance assessment tool initially developed for athletic populations, has recently been adapted for use with older adults (Park et al., 2020; Freund et al., 2019). The YBT was specifically chosen as a challenging task to provide comprehensive insights into the cognitive factors involved in dynamic balance performance. Identifying cognitive domains significantly predictive of YBT performance could clarify its potential utility for assessing cognitive-motor function, monitoring balance-related changes, or guiding targeted fall-risk interventions. This study is among the first to explore relationships between YBT performance and cognitive domains in aging populations, complementing existing findings from the TUG.

The primary aims of this study are: 1. To examine the potential association between different cognitive domains and dynamic balance; 2. To investigate which cognitive domain contributes to a significant portion of the variance in dynamic balance beyond common confounders which shows a significant correlation with cognition and dynamic balance in our sample, and 3. To compare the predictive roles of cognitive domains for performance on the TUG and YBT, informing tailored cognitive-motor exercise interventions.

By identifying cognitive domains that significantly predict performance on the YBT and TUG, this study seeks to clarify which cognitive factors should be prioritized within personalized exercise interventions. The insights gained could directly inform the design of targeted cognitive-motor interventions, particularly those incorporating digital therapeutics and wearable technologies, enhancing dynamic balance and long-term physical activity adherence in older adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This study employed an observational cross-sectional design. Sixty-two participants aged 60 years or older, living independently in the community, functionally independent, and capable of walking without aid or assistance, were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were: 1. using a walking aid; 2. having any neurological, psychological, orthopedic, or cardiorespiratory problems; 3. having any pain that could affect their walking and standing ability.

2.2. Measurements

Demographic data were collected on age, gender, education, and falls history (

Table 1). Participants were asked in an initial survey whether they had experienced any falls in the past year. BMI was measured using bioelectrical impedance (Seca 804 Flat Scale with Chromed Electrodes).

Participants started by choosing a number from 1 to 4 to establish the order of cognitive tests, each linked to a specific assessment. They then proceeded to the balance tests, which were administered in a randomized sequence.

2.3. Cognitive Tests

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

Global cognition was screened using MMSE. MMSE, which includes 30 questions, evaluates orientation, attention, memory (both immediate and short-term), language abilities, and the capacity to follow verbal and written instructions. Scores range from 0 (poor) to 30 (optimal) (Nagaratnam et al., 2022).

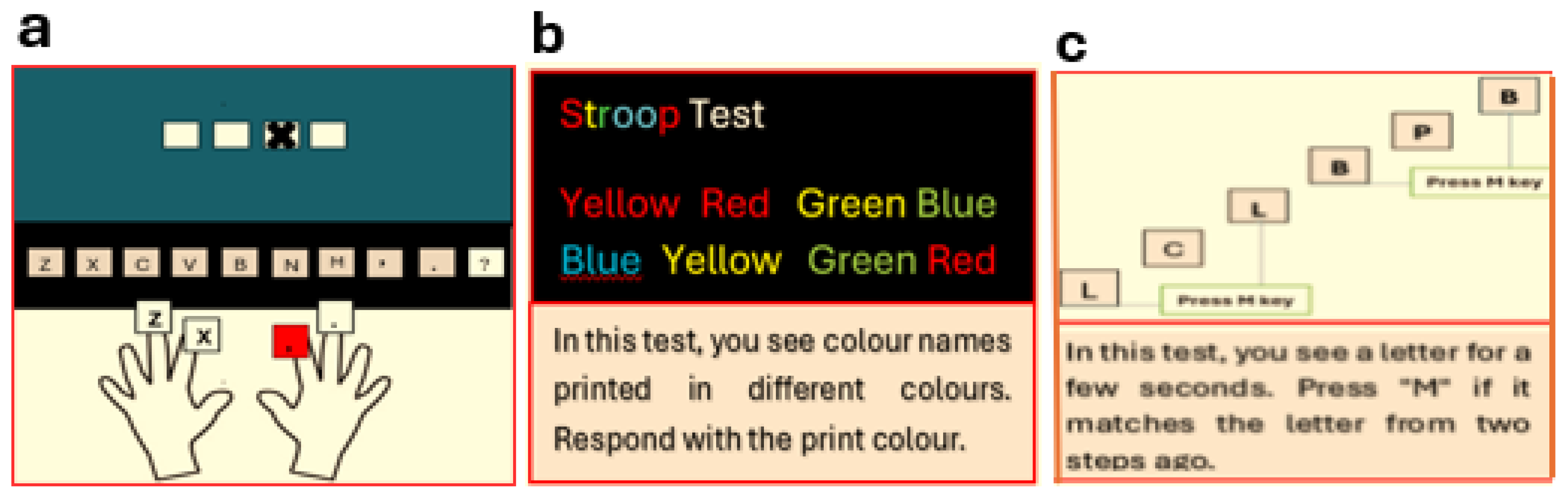

Domain-specific cognition tests were evaluated using PsyToolkit. This platform is an effective tool for carrying out both general and psycholinguistic experiments involving complex reaction time tasks (Kim et al., 2019). Tests were conducted as follows:

Stroop Colour–Word Test

This test assesses the capacity to inhibit cognitive interference. Participants quickly name the ink colour of words on a computer screen. This test has high test-retest reliability and good internal consistency (Strauss et al., 2005). The test includes congruent (matching) and incongruent (mismatching) conditions (

Figure 1b). Reaction time to incongruent conditions is analysed as a measure of interference effects (Periáñez et al., 2020).

N-Back Test

This test evaluates the working memory function (Kirchner, 1958). Participants are shown a series of letters and must decide if the current letter matches one presented three trials earlier (

Figure 1c). The accuracy of their responses is then analysed (

Figure 1c). Previous research has reported moderate test-retest reliability for accuracy scores (Hockey & Geffen, 2004). N-2 back task was used to assess working memory, as previous research suggests that more difficult working memory tasks show higher test-retest reliability (Dai et al., 2019).

2.4. Balance Tests

The Y Balance Test (YBT)

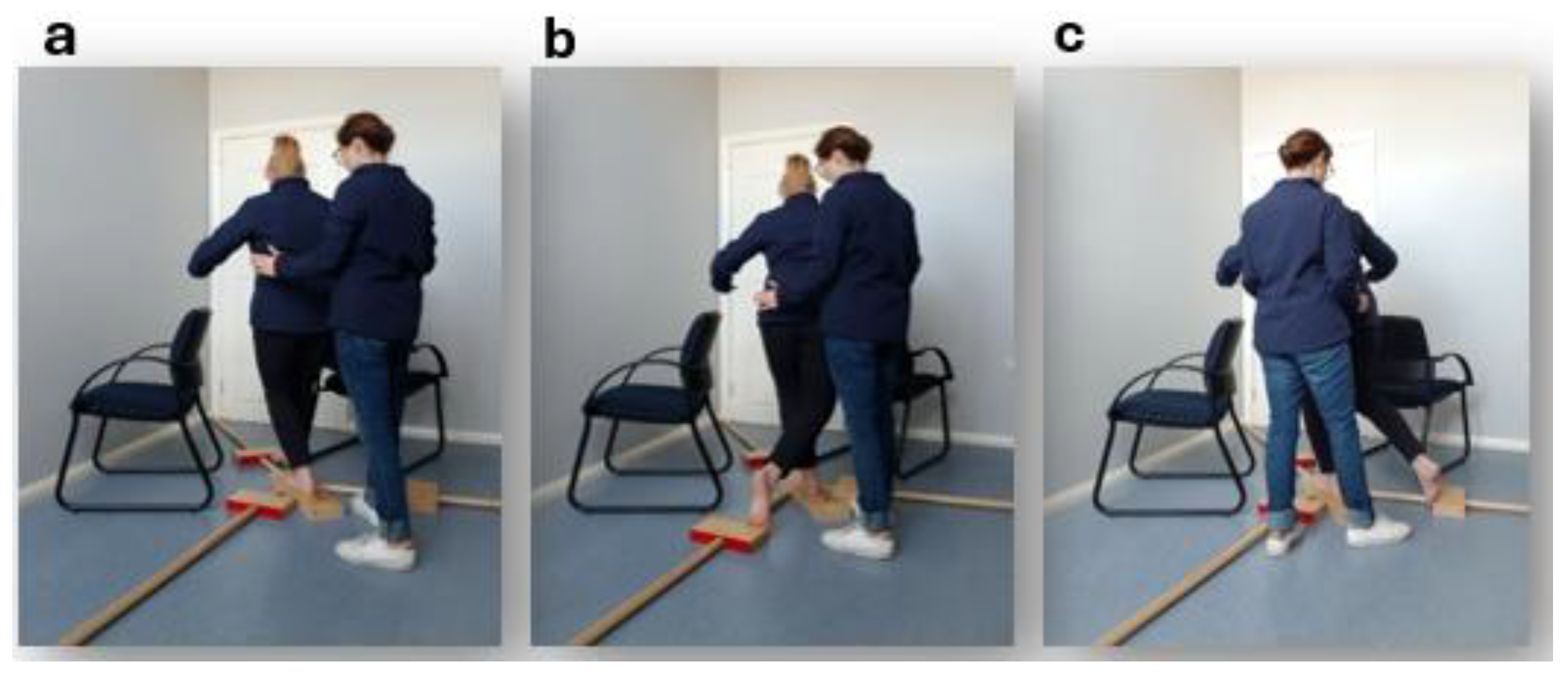

YBT

, a reliable and valid dynamic balance tool (Plisky et al., 2009), was used to assess dynamic balance among older adults (Sipe et al., 2019). Participants stood barefoot on a central wooden footplate and pushed a block in three directions using their dominant leg while balancing on their non-dominant leg to increase the challenge. They performed six practice trials per direction before completing three test trials, with the mean of the test trials analysed for each direction (Sipe et al., 2019). Adequate rest period was provided between practice and recorded trials, but not between individual trials (Sipe et al., 2019). Reach distance, measured to the nearest 0.5 cm, indicated where participants pushed the indicator block closest to the central footplate. For safety, the examiner stood one step back behind the participant. There were also two solid chairs on both sides of the YBT (

Figure 2). A trial was considered invalid if the participant failed to return to the starting position, used the reaching foot to kick the plate for additional distance, and stepped on the reach indicator for support (Sipe et al., 2019). Participants were allowed to use their arms for balance. If a participant failed to maintain a unilateral stance on the platform, touched the floor, or touched the chairs and/or examiner with hands, the score was considered zero. The normalised value was determined by dividing the total of the three reach directions by three times the limb length and multiplying the result by 100. After that, the composite limb scores (average of all three directions) were averaged to generate an overall YBT-LQ composite score (Sipe et al., 2019). The measurements of the participants' dominant lower limb length were taken in centimetres while they were lying in the supine position. The measurement involved assessing the distance from the anterosuperior iliac spine to the centre of the ipsilateral medial malleolus (Sipe et al., 2019).

The Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)

TUG is a dynamic balance assessment (Podsiadlo & Richardson, 1991). Participants sat on a 45 cm chair with arms comfortably placed on their lap. The test involved timing participants as they executed a sequence of movements: standing up, walking a 3-meter distance, turning around, walking back, and sitting down (Zhao et al., 2022).

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

First, a descriptive analysis of all participants’ demographic data was performed. Then, the distribution of all data was checked for normality (p<0.05). Pearson’s correlation coefficients between all demographic, cognitive, and balance variables were computed to evaluate the interrelationships between them (

Table 2). Age and education were selected as potential confounders for inclusion in the regression models because they were the only confounders that exhibited significant correlations with cognitive and balance variables among all other variables such as gender, fall history, BMI, and fat mass. To investigate whether cognition contributes to a significant portion of the variance in balance beyond age and education, hierarchical multiple regression analysis (MRA) was conducted (p<0.05, 0.01 and 0.001) (Tabachnick, 2019). There are 4 models as this process was repeated for each cognitive domain (Models 1 to 4) in relation to each balance test. In step one, age and education were examined as predictors. In step two, each cognitive domain was added individually to the regression equation to determine if it significantly increased the variance explained by the model (significant change in R

2). This process was repeated for each cognitive domain in relation to each balance test (Tabachnick, 2019).

Before interpreting the MRA results, several assumptions were assessed. Stem-and-leaf displays and boxplots were utilised to confirm that each regression variable followed a normal distribution and did not include univariate outliers. Additionally, normal probability plots and scatterplots of standardized residuals versus predicted values were examined to validate that the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity were satisfied (Tabachnick, 2019).

3. Result

3.1. Participants

The sample had a mean age of 74.8 years (ranging from 60 to 90) and a mean BMI of 28 (ranging from 17.3 to 42). It included 66% females and 53% had tertiary education (

Table 1). Notably, 40% of participants reported recent falls.

3.2. Association Between Demographic Information and Cognitive and Dynamic Balance Measures

The correlation analysis revealed significant associations between education level and all cognitive as well as dynamic balance measures in the group of participants. Age showed significant associations with all dynamic balance tests and cognitive measures, excluding working memory. Falls history displayed a significant correlation solely with the TUG test. The other demographic variables exhibited no correlations with cognitive and dynamic balance measures.

3.3. Association Among Cognitive and Dynamic Balance Measures

All cognitive measures, including global cognition, inhibition, working memory, and processing speed showed significant moderate association (ranging from 0.346 to 0.607, p<0.01) with normalised average reach distance in YBT. It indicates that people with better performance in all cognitive measures showed better balance function in YBT. All cognitive measures except working memory showed a significant moderate association (ranging from 0.405 to 0.501, p<0.01) with the TUG test. Baseline cognitive and balance test results and correlations are provided in

Table 2.

3.4. Cognitive Domains Predicting Dynamic Balance Beyond the Effect of Age and Education

Simple associations alone are not sufficient evidence for functional relationships (Rabbitt et al., 2006). To establish a functional relationship and determine which cognitive domain significantly contributes to the variance in dynamic balance beyond age and education, hierarchical multiple regression analyses (MRA) were conducted.

First, MRA was performed to predict dynamic balance scores based on age and education, calculating the initial R² values. Next, cognitive scores were added to the model to compute new R² values. The significance of the changes in R² was assessed to determine whether cognitive scores accounted for additional variance in dynamic balance test scores.

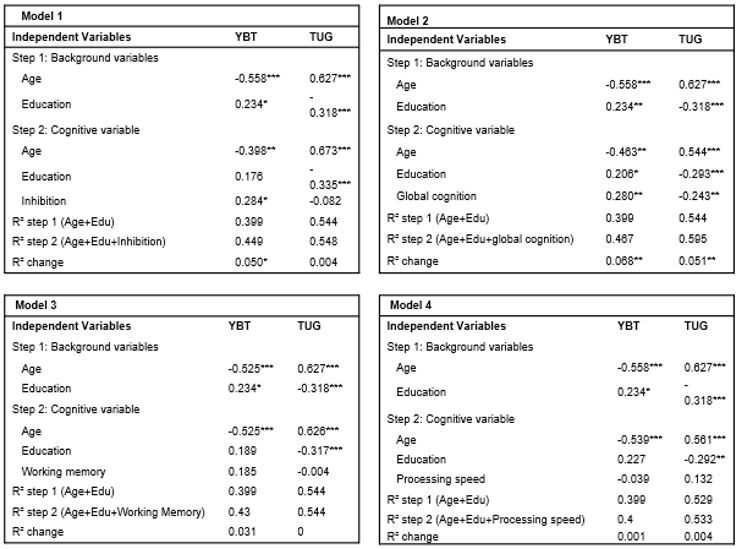

In the first step of the hierarchical MRA, age and education accounted for a significant variance in compliance. In the second step, global cognition and inhibition contributed significant additional variance, whereas processing speed and working memory did not (

Table 3).

3.5. Cognitive Domains Predicting TUG Versus YBT

In this study, hierarchical MRA was conducted with four models, each including age and education in step one, and adding a cognitive domain in step two in each model, to predict dynamic balance test scores. The results are described for both TUG and YBT in each model as follows:

Step 1: background variables

Age and education significantly predict balance performance (F (1,62) = 19.612, P = 0.000, R² = 0.399) in step one in all four models. Step 2 in each model for each cognitive domain as a predictor of TUG and YBT is as follows:

Model 1: Inhibition:

The initial model (Model 1) demonstrated a statistically significant fit during the first step of the analysis. Adding the inhibition score in step 2 did not significantly alter the model's fit (ΔR² = 0.004), although the overall model remained significant (F, 2, 62) = 23.473, P < 0.001, R² = 0.548).

For YBT, model 1 showed a significant overall fit at step 1. After adding the inhibition score in step 2, the overall fit of model 1 remained significant (F (2,62) = 15.750, P < 0.001, R² = 0.449), with a significant change to model fit (ΔR² = 0.050, P < 0.05). Inhibition significantly predicted YBT beyond the effect of age and education, see

Table 3.

Model 2: global cognition

For TUG, model 2 showed a significant overall fit in step 1. When global cognition scores were added in at step 2, the model 2 remained significant (F (2,62) = 24.221, P < 0.001, R² = 0.595). That accounted for a significant change (ΔR² = 0.051, P = 0.000). Global cognition significantly predicted TUG beyond the effect of age and education, see

Table 3.

When predicting YBT, the overall fit of model 2 was significant at step 1 and remained significant at step 2 (F (2,62) = 16.929, P = 0.009, R² = 0.467). The addition of global cognition scores resulted in a significant change in the overall model fit (ΔR² = 0.068, P = 0.009). Global cognition significantly predicted YBT beyond the effect of age and education, see

Table 3.

Model 3: Working Memory

For TUG, the overall model fit was significant at step 1. It remained significant at step 2 when correct rates in working memory were added (F (2,62) = 23.083, P < 0.001, R² = 0.544). However, there was no significant change to model fit (ΔR² = 0.000).

When predicting YBT, the overall fit of the model was significant at steps and remained significant in step 2 (F (2,62) = 14.581, P < 0.001, R² = 0.430). However, the change in step 2 was not significant (ΔR2 = 0.031).

Model 4: Processing speed

For TUG, there was a significant overall fit in step 1. When processing speed scores were added at step 2, the overall fit of model 3 remained significant (F (2,62) = 24.221, P < 0.001, R² = 0.533), but no significant change to model fit (ΔR² = 0.004).

For YBT, there was a significant overall fit in step 1. When processing speed scores were added in at step 2, the overall fit of model 4 remained significant (F1,45 = 17.96, P < 0.001, R2= 0.4) but no significant change to model fit (ΔR² = 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study addressed three key aims. Firstly, it identified significant associations between cognitive domains and dynamic balance performance. Secondly, it demonstrated that global cognition (MMSE) and inhibition (Stroop test) significantly predict dynamic balance beyond age and education, highlighting their unique contributions. Finally, it compared cognitive predictors of Y Balance Test (YBT) and Timed Up and Go (TUG) performance, showing that YBT was significantly predicted by global cognition and inhibition, whereas TUG performance was predominantly influenced by global cognition. These findings suggest that assessments of global cognition and inhibition could be particularly valuable in clinical practice for identifying older adults at risk for impaired balance. Incorporating tasks that specifically challenge these cognitive domains, such as dual-task exercises emphasizing attentional control and cognitive-motor integration, may enhance the effectiveness of dynamic balance interventions. Additionally, these targeted exercises could be effectively delivered and monitored using digital therapeutics and wearable technologies, aligning closely with personalized, technology-enhanced exercise programs for aging populations

Regarding aim one, global cognition, inhibition, and processing speed exhibited significant moderate associations with both dynamic balance tests, aligning with previous research (Jimenez-Garcia et al., 2024; Biasin et al., 2023). Interestingly, the N-back test, assessing working memory, showed a significant association only with YBT, differing from previous findings (Matoes et al. 2020). Given our robust study population, the TUG test may not have been sufficiently challenging cognitively, possibly explaining why working memory did not significantly associate with TUG performance.

Regarding aim two, hierarchical regression analysis demonstrated that cognitive function, age, and education collectively predict dynamic balance significantly. Notably, adding global cognition and inhibition improved prediction (significant increase in R² values), highlighting their unique contributions—global cognition for both YBT and TUG, and inhibition specifically for YBT. To our knowledge, this study uniquely highlights global cognition and inhibition as predictors of dynamic balance, whereas prior research primarily explored balance predicting cognition or general associations (Goto et al., 2018; Won et al., 2014). The observed inconsistencies between our findings and those reported by Zhao et al. (2022) and Won et al. (2014) may be attributable to methodological differences such as participant selection and assessment procedures, underscoring the importance of employing standardized protocols in future research. For instance, Zhao et al. (2022) recruited participants through community health service centres, whereas our study participants were a robust group. Additionally, Kwan et al. (2011) utilised the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, instructing participants to walk at their own comfortable pace, whereas our study instructed participants to walk as fast and safely as possible (Kwan et al., 2011). These methodological differences underscore the need to consider multiple factors influencing study outcomes.

Age-related cognitive decline may partially explain why global cognition and inhibition predict dynamic balance. Previous longitudinal research suggests cognitive deterioration often precedes mobility limitations, potentially reducing physical activity and subsequent balance ability (Elovainio et al., 2009; Gothe et al., 2014). Further longitudinal studies are needed to confirm causality and deepen the understanding of cognitive-mobility relationships.

Previous studies have associated better balance with superior Stroop test performance though typically focusing on balance as a predictor of cognitive function though these studies focused on balance predicting cognition (Berryman et al., 2013; Zettel-Watson et al., 2017). Executive function is a predictor of mobility outcomes (Gothe et al., 2014). Executive function, particularly inhibition, is crucial for coordinating movement and interacting with the environment, suggesting it plays a significant role in maintaining balance through sensory integration processes (Levin et al., 2014; Redfern et al., 2009). Structural changes in brain regions linked to inhibition, such as the middle frontal gyrus and basal ganglia, may underpin age-related postural control declines (Boisgontier et al., 2017). Therefore, integrating inhibition assessments such as the Stroop test in balance evaluations could offer valuable insights for identifying older adults at heightened risk of balance impairment.

However, our regression analysis revealed inhibition did not independently predict TUG performance. Given the robustness of our sample, the TUG may not have presented sufficient challenge to reveal significant associations with inhibition. Consistent with Berryman et al. (2013), who found a correlation between cognitive flexibility but not inhibition (Stroop) and TUG performance, our findings suggest the TUG may not fully capture cognitive-motor integration in robust healthy older adults. This highlights the importance of task selection tailored to cognitive challenge in older populations (Horak & Macpherson, 2011).

Regarding aim three, this study compared how cognitive domains predict performance on the YBT versus TUG. Results indicated that YBT performance was significantly predicted by both global cognition and inhibition, highlighting its sensitivity to tasks requiring complex cognitive-motor integration. In contrast, TUG performance was predominantly influenced by global cognition and was significantly associated with a history of falls, reinforcing its utility in assessing functional mobility and real-world fall risk. These findings underscore the clinical importance of incorporating cognitive evaluations into balance assessments to identify older adults at risk of dynamic balance impairments. Clinically, while the TUG remains valuable for evaluating functional mobility and practical fall risk, the YBT provides complementary insights, particularly among populations with higher baseline mobility.

5. Clinical Implications

The findings of this study underscore the importance of incorporating cognitive training into exercise programs in older adults. Research has shown that combined motor and cognitive training, such as dual-task exercises, can significantly enhance balance and reduce fall risk in older adults (Ali et al., 2022). However, it remains unclear which cognitive domain is most effective for dual-task training programs. Given that global cognition and inhibition were significant predictors of dynamic balance, targeted exercise programs should include activities that enhance these cognitive domains. Additionally, it is crucial to select tasks that are appropriately challenging for each individual. Therefore, an outcome measure to assess the challenge level of cognitive and balance tasks before tailoring them to clients is necessary. Tailoring interventions based on cognitive profiles may optimize balance rehabilitation, particularly for individuals at risk of mobility decline and falls.

As this study was cross-sectional, future research should focus on longitudinal designs to establish causality and explore how incorporating these cognitive domains into dual-task balance training can impact balance outcomes. Investigating the effects of such targeted interventions will help determine the most effective strategies for promoting long-term adherence to physical activity in older adults

6. Limitations

This study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow for the establishment of causal relationships between cognitive domains and dynamic balance. Although the regression models identified significant predictors, the directionality of these relationships needs to be explored in longitudinal studies.

Second, the study population consisted of robust older adults, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to frailer populations or those with significant cognitive or physical impairments. The performance on TUG test may not have been sufficiently challenging for this group, potentially reducing its sensitivity to detect associations with certain cognitive domains. YBT proved to be a safe and effective tool for assessing dynamic balance in this group, particularly in capturing cognitive-motor integration. However, its applicability and validity in frailer populations require further investigation.

Third, while the study incorporated multiple cognitive tests, including the MMSE, Stroop test, and N-back test, it did not account for other potentially influential factors, such as sensory deficits, muscle strength, or unreported medical conditions, which could also affect dynamic balance.

7. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that global cognition and inhibition significantly predict dynamic balance performance among robust older adults, emphasizing their distinct roles in cognitive-motor integration. Specifically, the Y Balance Test was sensitive to both global cognition and inhibition, while the Timed Up and Go test primarily reflected global cognitive function. Clinically, these findings highlight the importance of incorporating assessments such as the MMSE and Stroop test to identify older adults at risk of impaired balance. Such cognitive assessments could inform personalized cognitive-motor interventions, leveraging emerging technologies like digital therapeutics and wearable devices. Future longitudinal studies should explore targeted, cognitively enriched balance programs to optimize mobility outcomes, enhance fall prevention strategies, and promote sustained adherence to physical activity in aging populations.

Author Contributions

Nahid Divandari: Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, formal analysis, visualization, original draft preparation, literature review. †Shapour Jaberzadeh: Supervision, conceptualization, methodology, statistical analysis, background research, manuscript finalization. †Marie-Louise Bird: Supervision, conceptualization, manuscript review and finalization. Maryam Zoghi: Manuscript review and finalization. Fefe Vakili: Manuscript editing, participant coordination, data collection, documentation. These authors contributed equally to work.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent Statements

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC) in 2023 and the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) at the University of Tasmania in 2023. The approval numbers assigned are 31380 for MUHREC and 27343 for HREC at the University of Tasmania. All participants gave their informed consent after receiving thorough information about the study. Participation was voluntary, allowing them the freedom to withdraw at any time.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Tim Power, Consultant in Data Science, AI, and Sensitive Data Platforms at the Monash Research Centre, for his invaluable assistance with the statistical analysis in this paper.

References

- Bednarczuk, G., & Rutkowska, I. (2022). Factors of balance determining the risk of falls in physically active women aged over 50 years. PeerJ, 10, e12952. [CrossRef]

- Berryman, N., Bherer, L., Nadeau, S., Lauzière, S., Lehr, L., Bobeuf, F., Kergoat, M. J., Vu, T. T. M., & Bosquet, L. (2013). Executive functions, physical fitness and mobility in well-functioning older adults. Experimental Gerontology, 48(12), 1402-1409. [CrossRef]

- Boisgontier, M. P., Cheval, B., Chalavi, S., van Ruitenbeek, P., Leunissen, I., Levin, O., Nieuwboer, A., & Swinnen, S. P. (2017). Individual differences in brainstem and basal ganglia structure predict postural control and balance loss in young and older adults. Neurobiology of aging, 50, 47-59. [CrossRef]

- Chantanachai, T., Sturnieks, D. L., Lord, S. R., Payne, N., Webster, L., & Taylor, M. E. (2021). Risk factors for falls in older people with cognitive impairment living in the community: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 71, 101452. [CrossRef]

- Chantanachai, T., Taylor, M. E., Lord, S. R., Menant, J., Delbaere, K., Sachdev, P. S., Kochan, N. A., Brodaty, H., & Sturnieks, D. L. (2022). Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people with mild cognitive impairment: a prospective one-year study. PeerJ, 10, e13484. [CrossRef]

- Deary, I. J., Liewald, D., & Nissan, J. (2011). A free, easy-to-use, computer-based simple and four-choice reaction time programme: the Deary-Liewald reaction time task. Behav Res Methods, 43(1), 258-268. [CrossRef]

- Divandari, N., Bird, M. L., Vakili, M., & Jaberzadeh, S. (2023). The Association Between Cognitive Domains and Postural Balance among Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Literature and Meta-Analysis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 23(11), 681-693. [CrossRef]

- Elovainio, M., Kivimäki, M., Ferrie, J. E., Gimeno, D., Vogli, R. D., Virtanen, M., Vahtera, J., Brunner, E. J., Marmot, M. G., & Singh-Manoux, A. (2009). Physical and cognitive function in midlife: reciprocal effects? A 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63(6), 468. [CrossRef]

- Falck, R. S., Davis, J. C., & Liu-Ambrose, T. (2017). What is the association between sedentary behaviour and cognitive function? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med, 51(10), 800-811. [CrossRef]

- Gothe, N. P., Fanning, J., Awick, E., Chung, D., Wójcicki, T. R., Olson, E. A., Mullen, S. P., Voss, M., Erickson, K. I., Kramer, A. F., & McAuley, E. (2014). Executive function processes predict mobility outcomes in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc, 62(2), 285-290. [CrossRef]

- Goto, S., Sasaki, A., Takahashi, I., Mitsuhashi, Y., Nakaji, S., & Matsubara, A. (2018). Relationship between cognitive function and balance in a community-dwelling population in Japan. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 138(5), 471-474.

- Heaw, Y. C., Singh, D. K. A., Tan, M. P., & Kumar, S. (2022). Bidirectional association between executive and physical functions among older adults: A systematic review. Australas J Ageing, 41(1), 20-41. [CrossRef]

- Iso-Markku, P., Aaltonen, S., Kujala, U. M., Halme, H.-L., Phipps, D., Knittle, K., Vuoksimaa, E., & Waller, K. (2024). Physical Activity and Cognitive Decline Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Network Open, 7(2), e2354285-e2354285. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Gabriel, U., & Gygax, P. (2019). Testing the effectiveness of the Internet-based instrument PsyToolkit: A comparison between web-based (PsyToolkit) and lab-based (E-Prime 3.0) measurements of response choice and response time in a complex psycholinguistic task. PLoS One, 14(9), e0221802. [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, W. K. (1958). Age differences in short-term retention of rapidly changing information. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 55(4), 352-358. [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M. M.-S., Lin, S.-I., Chen, C.-H., Close, J. C. T., & Lord, S. R. (2011). Sensorimotor function, balance abilities and pain influence Timed Up and Go performance in older community-living people. Aging clinical and experimental research, 23(3), 196-201. [CrossRef]

- Levin, O., Fujiyama, H., Boisgontier, M. P., Swinnen, S. P., & Summers, J. J. (2014). Aging and motor inhibition: A converging perspective provided by brain stimulation and imaging approaches. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 43, 100-117. [CrossRef]

- Muir-Hunter, S. W., Clark, J., McLean, S., Pedlow, S., Van Hemmen, A., Montero Odasso, M., & Overend, T. J. (2014). Identifying balance and fall risk in community-dwelling older women: the effect of executive function on postural control. Physiotherapy Canada. Physiotherapie Canada, 66 2, 179-186.

- Nagaratnam, J. M., Sharmin, S., Diker, A., Lim, W. K., & Maier, A. B. (2022). Trajectories of Mini-Mental State Examination Scores over the Lifespan in General Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. Clinical Gerontologist, 45(3), 467-476. [CrossRef]

- Nashner, L. M. (2014). Practical biomechanics and physiology of balance. Balance function assessment and management, 431.

- Periáñez, J. A., Lubrini, G., García-Gutiérrez, A., & Ríos-Lago, M. (2020). Construct Validity of the Stroop Color-Word Test: Influence of Speed of Visual Search, Verbal Fluency, Working Memory, Cognitive Flexibility, and Conflict Monitoring. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 36(1), 99-111. [CrossRef]

- Plisky, P. J., Gorman, P. P., Butler, R. J., Kiesel, K. B., Underwood, F. B., & Elkins, B. (2009). The reliability of an instrumented device for measuring components of the star excursion balance test. N Am J Sports Phys Ther, 4(2), 92-99.

- Podsiadlo, D., & Richardson, S. (1991). The timed "Up & Go": a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc, 39(2), 142-148. [CrossRef]

- Rabbitt, P. M., Scott, M., Thacker, N., Lowe, C., Horan, M., Pendleton, N., Hutchinson, D., & Jackson, A. (2006). Balance marks cognitive changes in old age because it reflects global brain atrophy and cerebro-arterial blood-flow. Neuropsychologia, 44(10), 1978-1983. [CrossRef]

- Redfern, M. S., Jennings, J. R., Mendelson, D., & Nebes, R. D. (2009). Perceptual Inhibition is Associated with Sensory Integration in Standing Postural Control Among Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 64B(5), 569-576. [CrossRef]

- Sipe, C. L., Ramey, K. D., Plisky, P. P., & Taylor, J. D. (2019). Y-Balance Test: A Valid and Reliable Assessment in Older Adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 27(5), 663-669. [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. . (2019). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson.

- Thomas, E., Battaglia, G., Patti, A., Brusa, J., Leonardi, V., Palma, A., & Bellafiore, M. (2019). Physical activity programs for balance and fall prevention in elderly: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore), 98(27), e16218. [CrossRef]

- Won, H., Singh, D. K. A., Din, N. C., Badrasawi, M. M., Manaf, Z. A., Tan, S. T., Tai, C. C., & Shahar, S. (2014). Relationship between physical performance and cognitive performance measures among community-dwelling older adults. Clinical Epidemiology, 6, 343 - 350.

- World Health Organization, W. (2022).

- Zettel-Watson, L., Suen, M., Wehbe, L., Rutledge, D. N., & Cherry, B. J. (2017). Aging well: Processing speed inhibition and working memory related to balance and aerobic endurance. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 17(1), 108-115. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Huang, H., & Du, C. (2022). Association of physical fitness with cognitive function in the community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 868. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).