Submitted:

05 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

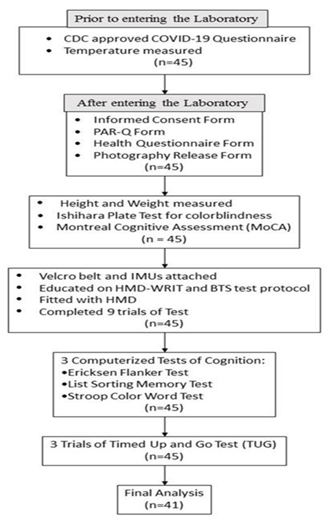

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment

2.2. Inclusion

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Procedures

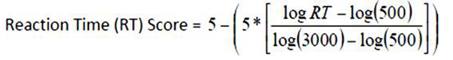

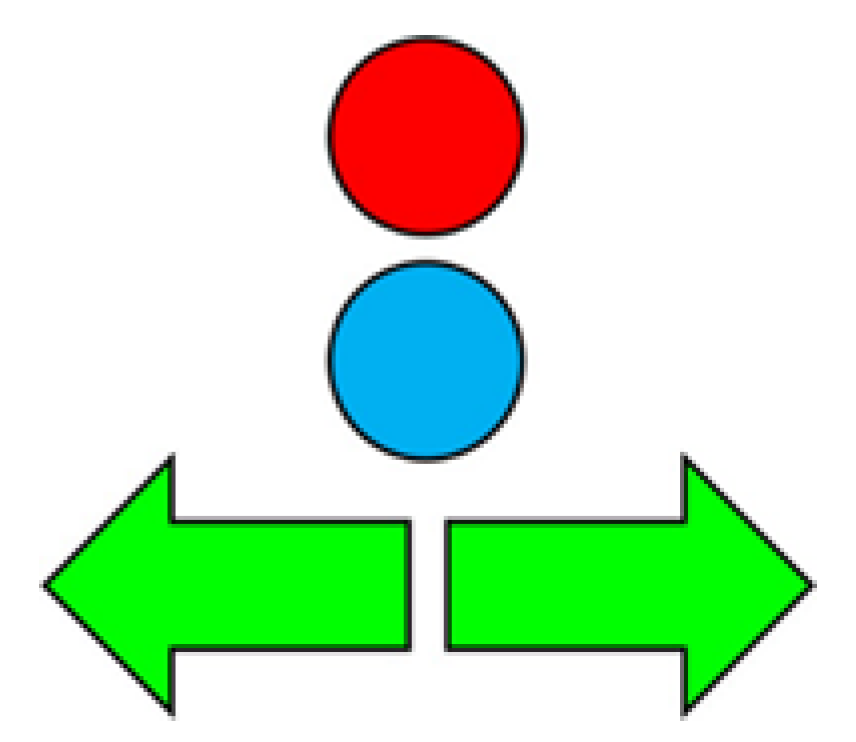

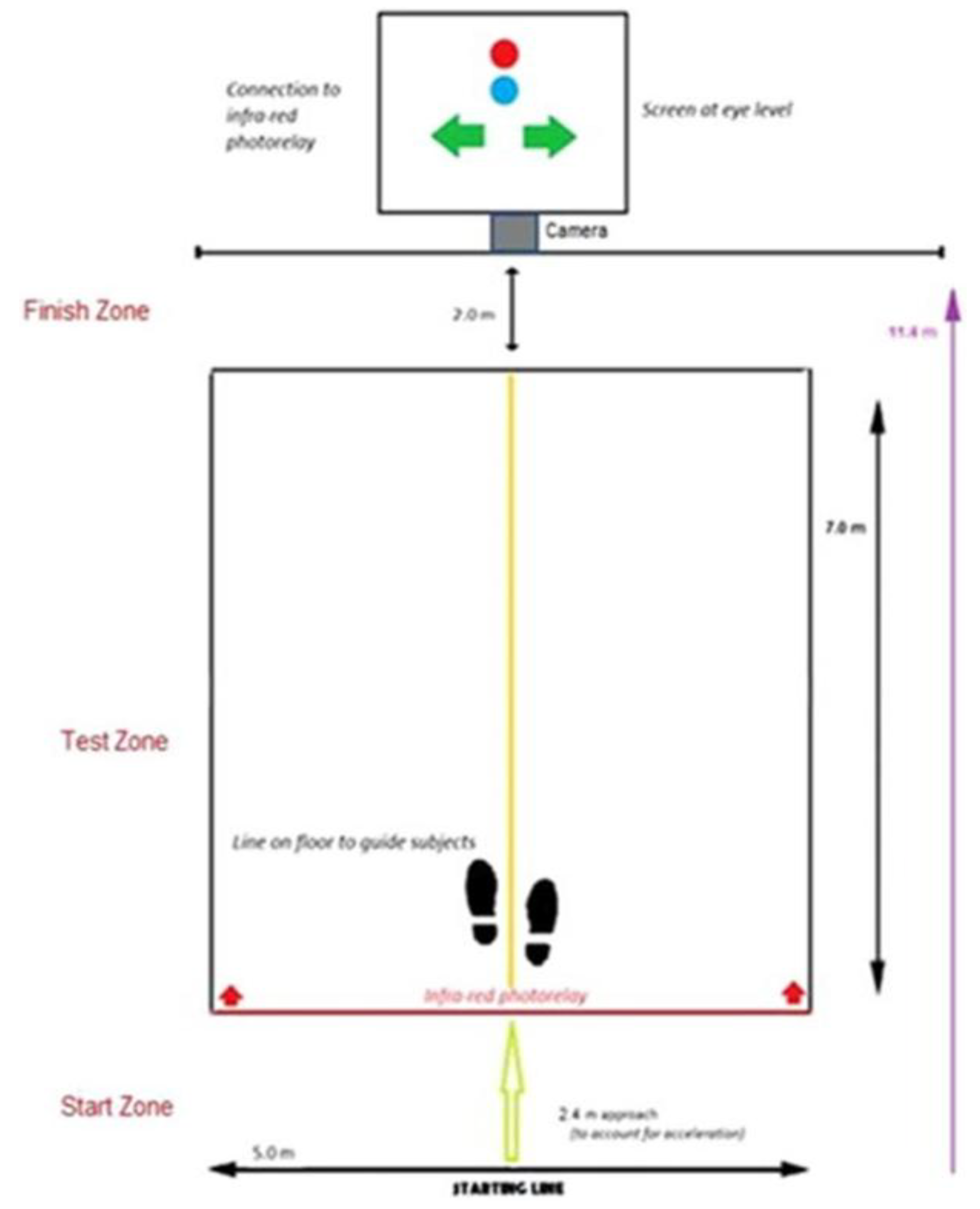

2.5. HMD-WRIT

3. Statistical Analyses

- 1)

- After applying the newly formed criteria for “purposeful” HMD-WRIT postural responses, data were analyzed by Pearson correlation analyses, comparing the HMD-WRIT to the two 3D motion analysis systems (BTS and QTM) outputs for LAT, ACC, and calculated EF scores. Bland-Altman plots provided further relationships analyses. The standard error of measurement (SEm) was computed (as a measure of the error in the scores not due to true changes) using the formula:

- 2)

- Pearson correlation analyses compared the three computer-based cognition tests ACC and LAT data to the HMD-WRIT.

- 3)

- Finally, Pearson correlation analyses tested the HMD-WRIT LAT scores to the mean of the three timed TUG scores.

4. Results

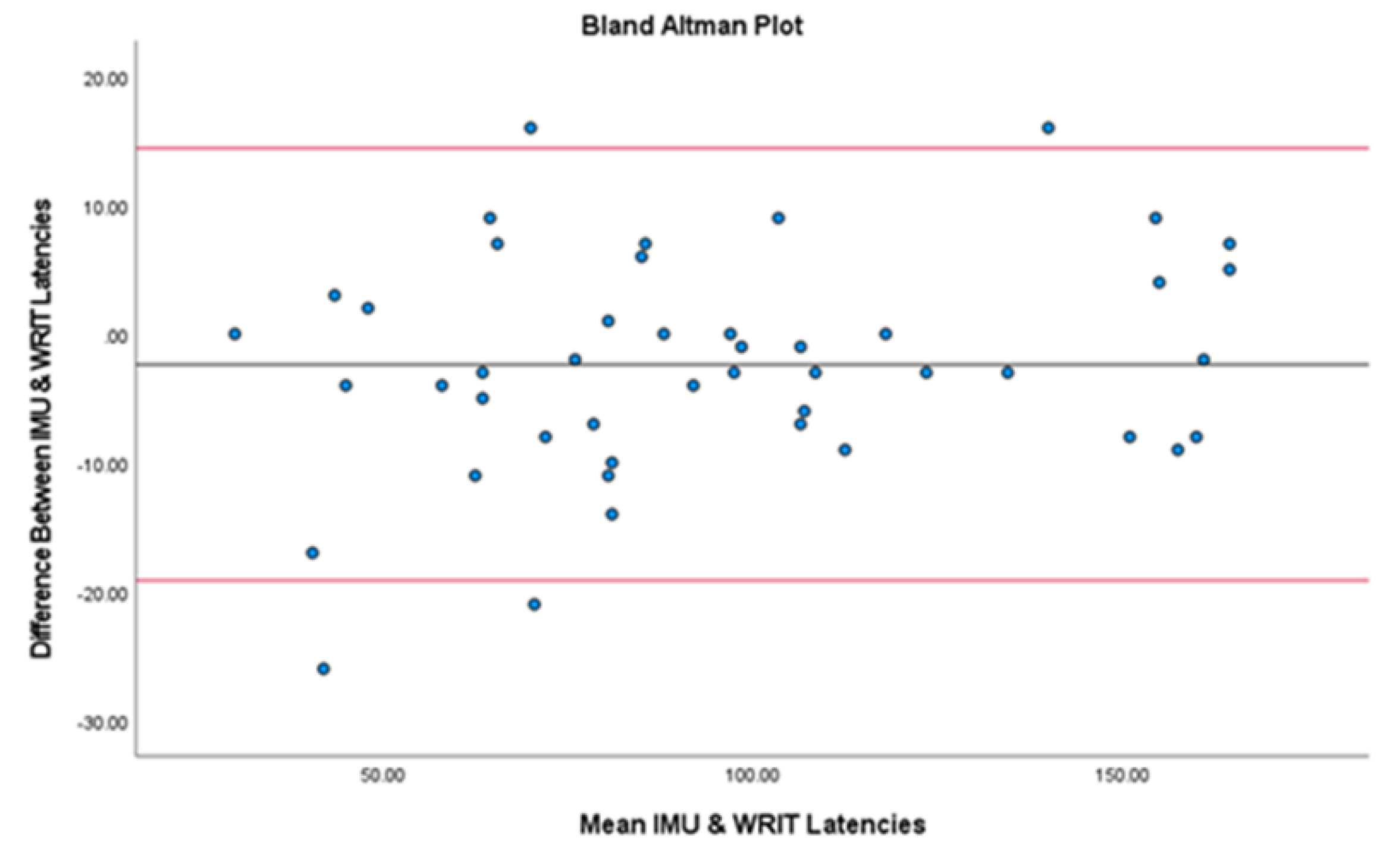

- A significant, Strong correlation existed between the HMD-WRIT and the QTM 3D Motion Analysis system (r=0.98, p<.001), confirmed by Bland-Altman analyses, showing no significant statistical difference between the two devices (t(43)=1.66, p=.104) (Figure 6 and Appendix Table 5).

- 2.

- Statistically significant height and weight differences existed in the younger adults, therefore results were interpreted by gender, rather than in aggregate (Appendix Table 6). Males had a significantly shorter mean LAT (0.76s) compared to females (0.92s, p=0.003), and males had significantly higher ACC (85.89%) to females (71.00%, p=0.008).

- 3.

- A significant, Moderate positive correlation existed for MoCA to group ACC (r=.398, p=.007) and no correlation existed between TUG to group LAT (r=.071, p=.647). A significant positive correlation of MoCA to group EF (r=.331, p=.028) existed, and a negative correlation of TUG to group EF (r= -.202, p=.189) was shown (Appendix Table 7).

- Healthy young adults had shorter LAT values than the older group (0.84s ± .18s compared to 1.29s ± .21s),

- Young males had higher mean ACC, (85.89% ± SD12.57% to 81.5% ± SD19.1%), but young females did not (71% ± SD21.28%),

- Due to shorter LAT values, the young adults’ calculated mean EF scores were lower (63.15 ± SD11.09 to 103.66 ± SD24.8), where EF = LAT (sec) * ACC (%)

- The young adults had less variable EF scores (122.87 ± 11.08 to 615.04 ± 24.8), where EF = LAT (sec) * ACC (%).

5. Discussion

Limitations

6. Conclusions

| Older adult cohort | |||

| Variable | Men | Women | Sample |

| N | 22 | 23 | 45 |

| Age | 69.5 ± 10.4 | 69.6 ± 9.8 | 69.5 ± 10.0 |

| Height (in) | 70.47 ± 3.15* | 64.17 ± 3.54 | 67.32 ± 4.72 |

| Weight (lb) | 198.2 ± 29.98* | 143.52 ± 29.1 | 170.42 ± 40.12 |

| Younger adult cohort | |||

- Variable Men Women Sample

- N 21 23 44

- Age 26 ± 6.74 26.47 ± 6.36 26.25 ± 6.47

- Height (in) 70.76 ± 2.3* 64 ± 3.11 67.23 ± 4.37

- Weight (lb) 182.95 ± 30.32* 145.87 ± 28.79 163.57 ± 34.68

- All values are Mean ± SD *Significantly greater than women, p<.001.

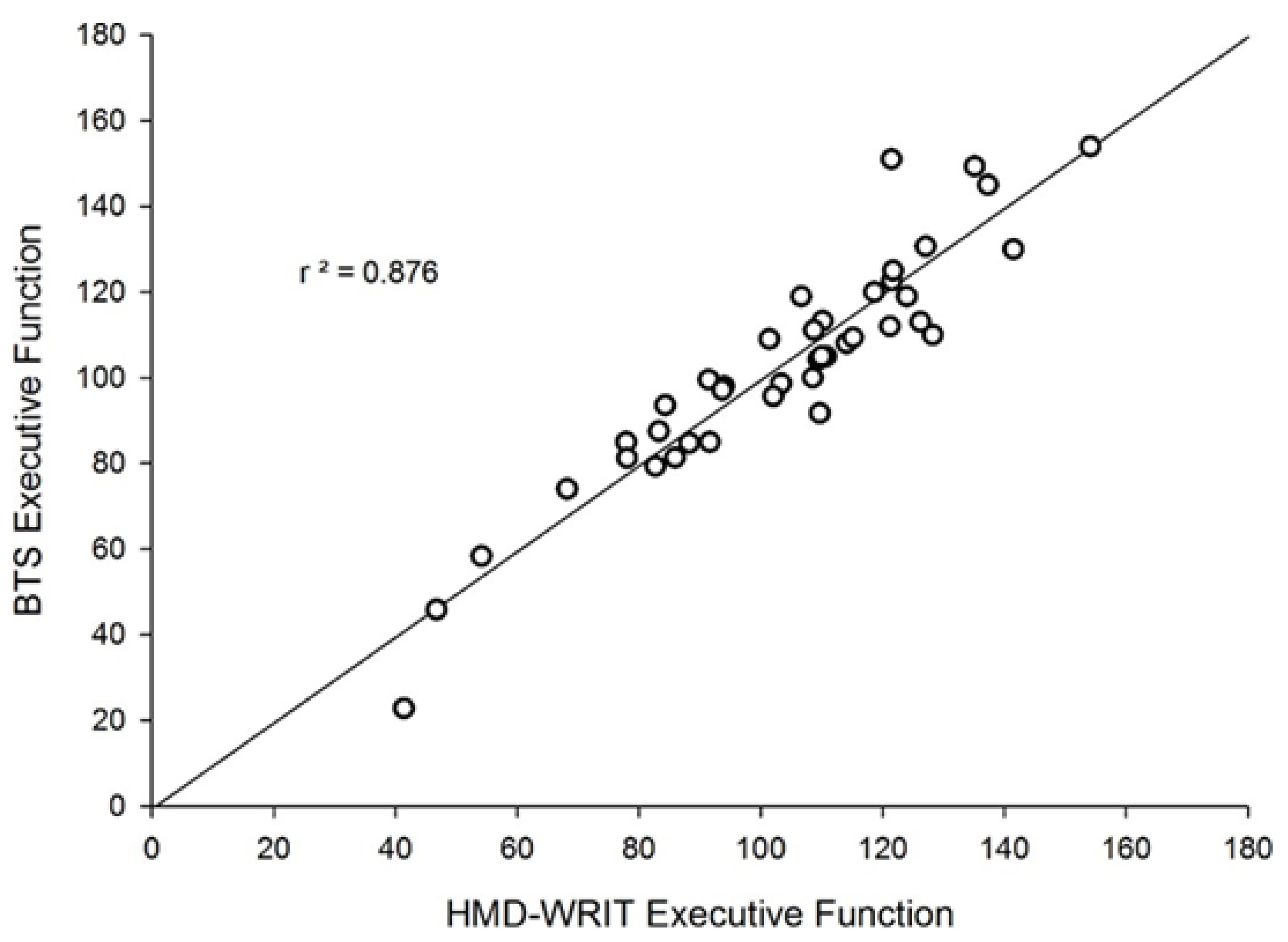

| Variable | N | HMD-WRIT | BTS | r | p |

| ACC (%) | 41 | 81.5 ± 19.1 | 81.5 ± 20.20 | .994* | <.0001 |

| LAT (s) | 41 | 1.29 ± 0.24 | 1.29 ± 0.20 | .916* | <.0001 |

| EF | 41 | 103.66 ± 24.80 | 103.05 ± 26.52 | .936* | <.0001 |

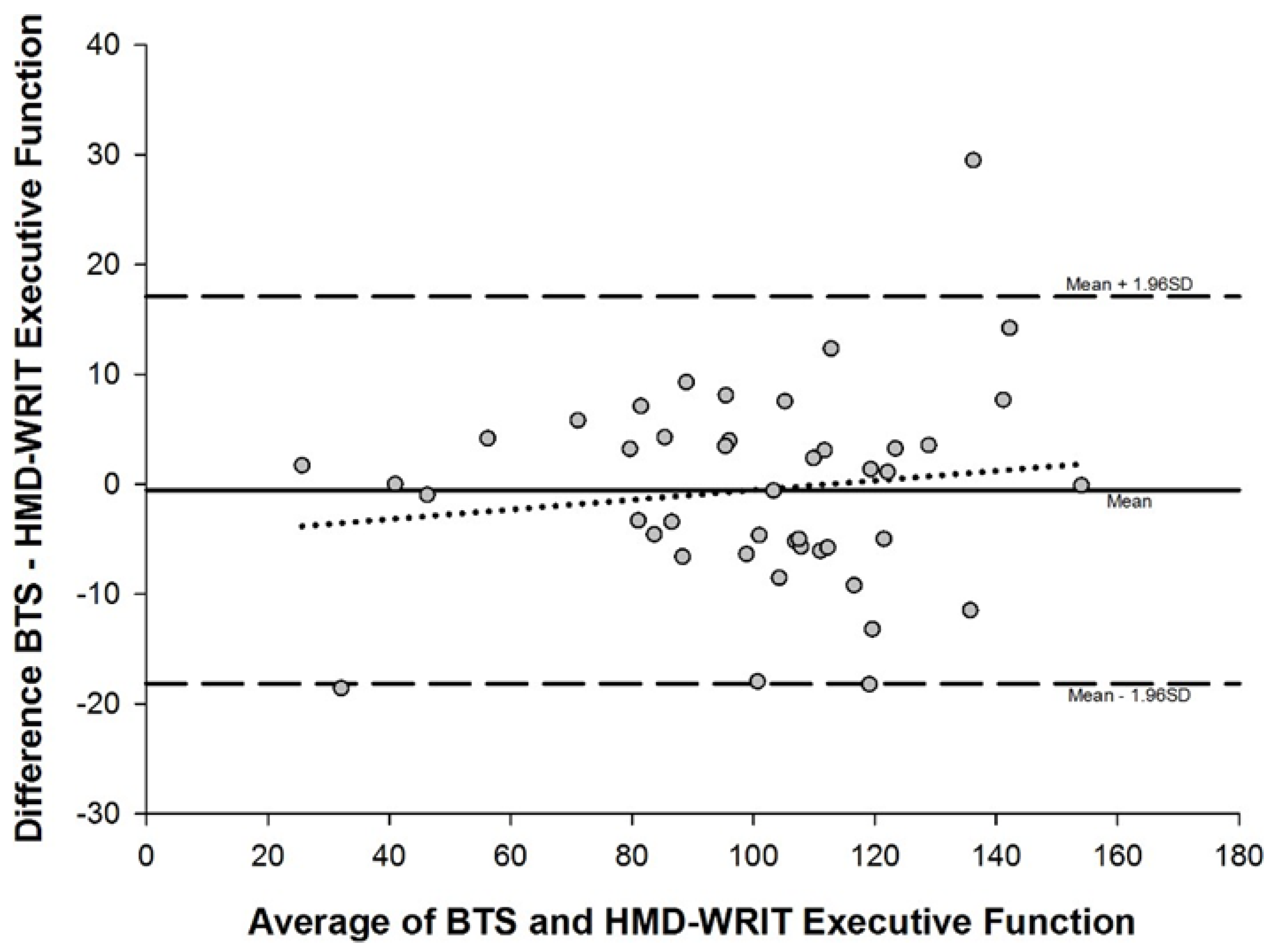

| Variable | Bias ± SD | Bias 95% CI |

LOA | Lower LOA 95% CI |

Upper LOA 95% CI |

| Accuracy (%) | 0.00 ± 2.48 |

-0.78 to 0.78 | -4.87 to 4.87 | -6.23 to -3.51 | 3.51 to 6.23 |

| Latency (s) | 0.00 ± 0.96 |

-0.03 to 0.03 | -0.03 to 0.03 | -0.24 to -0.13 | 0.14 to 0.24 |

| EF |

-0.51 ± 0.90 |

-0.98 to -0.05 | -2.27 to 1.25 |

-3.08 to -1.47 | 0.44 to 2.051 |

| Variable | N | HMD-WRIT | Flanker | r | p |

| ACC (%) | 41 | 81.5± 19.1 | 99.98 ± 0.16 | .310† | .052 |

| LAT (s) | 41 | 1.29 ± 0.21 | 0.90 ± 0.18 | .166 | .306 |

| EF | 41 | 103.37 ± 25.05 | 89.78 ± 17.48 | .146 | .368 |

| Variable | N | HMD-WRIT | List Sort | r | p |

| ACC (%) | 41 | 81.5 ± 19.1 | 63.40 ± 10.65 | .076 | .640 |

| Variable | N | HMD-WRIT | Stroop | r | p |

| ACC (%) | 41 | 81.5 ± 19.1 | 94.90 ± 9.39 | .053 | .748 |

| LAT (s) | 41 | 1.29 ± 0.21 | 1.49 ± 0.43 | .170 | .295 |

| EF | 41 | 103.37 ± 25.05 | 139.88 ± 34.82 | .236 | .142 |

| Variable | N | HMD-WRIT | QTM | r | p |

| Variable | N | Males (n=21) | Females (n=22) | F | p |

| ACC (%) | 43 | 85.89 ± 12.57 | 71 ± 21.28 | 7.799* | 0.008 |

| LAT (s) | 43 | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 0.92 ± 0.19 | 9.946* | 0.003 |

| EF | 43 | 64.67 ± 9.19 | 61.77 ± 12.62 |

| Variable | N | Mean | r (TUG) r (MoCA) | p | |

| ACC (%) | 43 | 78.27 ± 17.03 | .398* | .007 | |

| LAT (s) | 43 | 0.84 ± 0.15 | .071 | .647 | |

| EF TUG (s) MoCA |

43 43 43 |

63.19 ± 10.94 5.097 ± 1.01 28.47 ± 1.25 |

-.202 .331* | .189, .028 |

| Variable | Younger Males | Younger Females | Older adults |

| Latency (LAT) sec | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 0.92 ± 0.19 | 1.29 ± 0.24 |

| Accuracy (ACC) % | 85.89 ± 12.57 | 71.00 ± 21.28 | 81.50 ± 19.10 |

| EF | 64.67 ± 9.19 | 61.77 ± 12.62 | 103.66 ± 26.52 |

| Younger Adults | Older Adults | ||

| EF Variance 122.99 | 703.31 | ||

| TUG 5.09 ± 1.00 | 6.23 ± 1.46 | ||

| MoCA 28.47 ± 1.25 | 28.07 ± 1.84 | ||

References

- Huang SF, Liu CK, Chang CC, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of executive function tests for Alzheimer’s disease. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2017; 24(6):493- 504. [CrossRef]

- Kudlicka A, Hindle JV, Spencer LE, and Clare L. Everyday functioning of people with Parkinson’s disease and impairments in executive function: a qualitative investigation. Disabil Rehabil 2018; 40(20):2351-2363. [CrossRef]

- Eman Abdulle A and VDNaalt J. The role of mood, post-traumatic stress, post-concussive symptoms and coping on outcome after MTBI in elderly patients. Int Rev Psychiatry 2020; 32(1):3-11.

- Mirelman A, Herman T, Brozgol M, et al. Executive function and falls in older adults: new findings from a five-year prospective study link fall risk to cognition. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e40297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040297. Epub 2012 Jun 29. PMID: 22768271; PMCID: PMC3386974. [CrossRef]

- Hall CD, Herdman SJ, Whitney SL, et al. Treatment for vestibular disorders: How does your physical therapist treat dizziness related to vestibular problems? J Neurol Phys Ther 2016; 40(2):156.

- Alsalaheen BA, Whitney SL, Marchetti GF, et al. Relationship between cognitive assessment and balance measures in adolescents referred for vestibular physical therapy after concussion. Clin J Sport Med 2016; 26(1):46-52. [CrossRef]

- Gottshall KR and Hoffer ME. Tracking recovery of vestibular function in individuals with blast-induced head trauma using vestibular-visual-cognitive interaction tests. J Neurol Phys Ther 2010; 34(2):94-7. [CrossRef]

- Leyva A, Balachandran A, Britton JC, et al. The development and examination of a new walking executive function test for people over 50 years of age. Physiol Behav 2017; 171:100-109. [CrossRef]

- Perrochon A, Kemoun G, Watelain E, et al. The Stroop Walking Task: An innovative dual-task for the early detection of executive function impairment. Neurophysiol Clin 2015; 45(3):181-90. [CrossRef]

- Sulway S and Whitney SL. Advances in vestibular rehabilitation. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 2019; 82:164-169.

- Dunlap PM, Holmburg JM, and Whitney SL. Vestibular rehabilitation: advances in peripheral and central vestibular disorders. Curr Opin Neurol 2019; 32(1):137- 144. [CrossRef]

- Malinska M, Zuzewicz K, Bugajska J, et al. Subjective sensations indicating simulator sickness and fatigue after exposure to virtual reality. Med Pr 2014; 65(3):361-71. [CrossRef]

- Aldaba CN, White PJ, Byagowi A, et al. Virtual reality body motion induced navigational controllers and their effects on simulator sickness and pathfinding. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2017; 4175-4178.

- Kiryu T and So RH. Sensation of presence and cybersickness in applications of virtual reality for advanced rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2007; 4:34.

- Tal D, Wiener G, and Shupak A. Mal de debarquement, motion sickness and the effect of an artificial horizon. J Vestib Res 2014; 24(1):17-23. [CrossRef]

- Baus O and Bouchard S. Moving from virtual reality exposure-based therapy to augmented reality exposure-based therapy: a review. Front Hum Neurosci 2014; 8:112.

- Buskirk JK. Validation of a Head Mounted Display Augmented Reality Device with Inertial Measurement Unit for Anywhere Administration for Executive Function Testing. PhD Dissertation, University of Miami, USA, 2021.

- Sobolewski EJ, Thompson BJ, Conchola EC, et al. Development and examination of a functional reactive agility test for older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res 2017; 30(4):293-298. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen BA and Eriksen CW. Effects of noise letters upon identification of a target letter in a non-search task. Percept Psychophys 1974; 16:143-149. doi: 10.3758, bf03203267.

- Davelaar EJ. When the ignored gets bound: Sequential effects in the Flanker Task. Front Psychol 2013; 3:552. [CrossRef]

- Tulsky DS, Carlozzi N, Chiaravalloti ND, et al. NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery (NIHTB-CB): list sorting test to measure working memory. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2014; 20(6):599-610. [CrossRef]

- Lamers MJ. Selective attention and response set in the Stroop Task. Memory & Cognition 2010; 38(7):893-904. [CrossRef]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol 1935; 18(6):643-662.

- Scarpina F and Tagini S. The Stroop Color and Word Test. Front Psychol 2017; 8:557.

- Howieson DB, Lezak MD, and Loring DW. Orientation and attention: Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. 2004 p.365–367. ISBN 978-0-19-511121-7.

- Strauss E, Sherman E, and Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: Administration, norms, and commentary. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. 2006. p. 477–499. ISBN 978-0-19-515957-8.

- Podsiadlo D and Richardson S. The Timed Up and Go: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991; 39(2):142-148.

- Tan JP, Li N, Gao J, et al. Optimal cutoff scores for dementia and mild cognitive impairment of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment among elderly and oldest-old Chinese population. J Alzheimers Dis 2015; 43(4):1403-12. [CrossRef]

- Moriwaka F, Tashiro K, and Itoh K. Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan. Intern Med 1996; 35:276. [CrossRef]

- Cabeza R, Grady CL, Nyberg L, et al. Age-related differences in neural activity during memory encoding and retrieval: A positron emission tomography study. J Neurosci 1997; 17:391–400. [CrossRef]

- Madden DJ, Turkington TG, Provenzale JM, et al. Adult age differences in the functional neuroanatomy of verbal recognition memory. Hum Brain Mapp 1999; 7:115–135.

- Reuter-Lorenz PA, Jonides J, Smith EE, et al. Age differences in the frontal lateralization of verbal and spatial working memory revealed by PET. J Cogn Neurosci 2000; 12:174–187. [CrossRef]

- Logan JM, Sanders AL, Snyder AZ, et al. Under- recruitment and nonselective recruitment: Dissociable neural mechanisms associated with aging. Neuron 2002; 33:827–840.

- Rosen AC, Prull MW, O’Hara R, et al. Variable effects of aging on frontal lobe contributions to memory. Neuroreport 2002; 13:2425–2428. [CrossRef]

- Juan MC, Mendez-Lopez M, Perez-Hernandez E, et al. Augmented reality for the assessment of children’s spatial memory in real settings. PLoS One 2014; 9(12):e113751. [CrossRef]

- Gothe NP, Fanning J, Awick E, et al. Executive function processes predict mobility outcomes in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62(2):285-90. [CrossRef]

- Gothe NP, Fanning J, Awick E, et al. Executive function processes predict mobility outcomes in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62(2):285-290.

- Mitchell M and Miller LS. Prediction of functional status in older adults: the ecological validity of four Delis–Kaplan executive function system tests. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2008; 30(6): 683-690. [CrossRef]

- De Weerd P, Reinke K, Ryan L, et al. Cortical mechanisms for acquisition and performance of bimanual motor sequences. Neuroimage 2003; 19(4):1405-16.

- Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 2011; 305(1):50-8.

- Hultsch DF, MacDonald SW, and Dixon RA. Variability in reaction time performance of younger and older adults. J Gerontol B Ssychol Sci Soc Sci 2002; 57(2):101- 115. [CrossRef]

- Gorus E, DRaedt R, and Mets T. Diversity, dispersion and inconsistency of reaction time measures: effects of age and task complexity. Aging Clin Exp Res 2006; 18(5):407-17. [CrossRef]

- Grand JH, Stawski RS, and MacDonald SW. Comparing individual differences in inconsistency and plasticity as predictors of cognitive function in older adults. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2016; 38(5):534-50. [CrossRef]

- Bielak AA, Hultsch DF, Strauss E, et al. Intraindividual variability is related to cognitive change in older adults: evidence for within-person coupling. Psychol Aging 2010; 25(3):575-86. [CrossRef]

- Kail R and Salthouse TA. Processing speed as a mental capacity. Acta Psychol (Amst) 1994; 86(2-3):199-225.

- Engel BT, Thorne PR, and Quilter RE. On the relationship among sex, age, response mode, cardiac cycle phase, breathing cycle phase, and simple reaction time. J Gerontol 1972; 27(4):456-460. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).