Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Tuberculosis as a Global Treat

1.1. Distribution of Tuberculosis and Its Pathogenesis

1.2. Common Features of Pathogenic and Non-Pathogenic Actinobacteria

2. Polyamine Metabolism in M. tuberculosis as a Part of Nitrogen Metabolism for Survival and Pathogenicity

2.1. Nitrogen Assimilation and Its Control in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis

2.2. GS-like Enzymes GlnA2, GlnA3 and GlnA4 in M. tuberculosis

2.3. Polyamine Metabolism in Actinobacteria

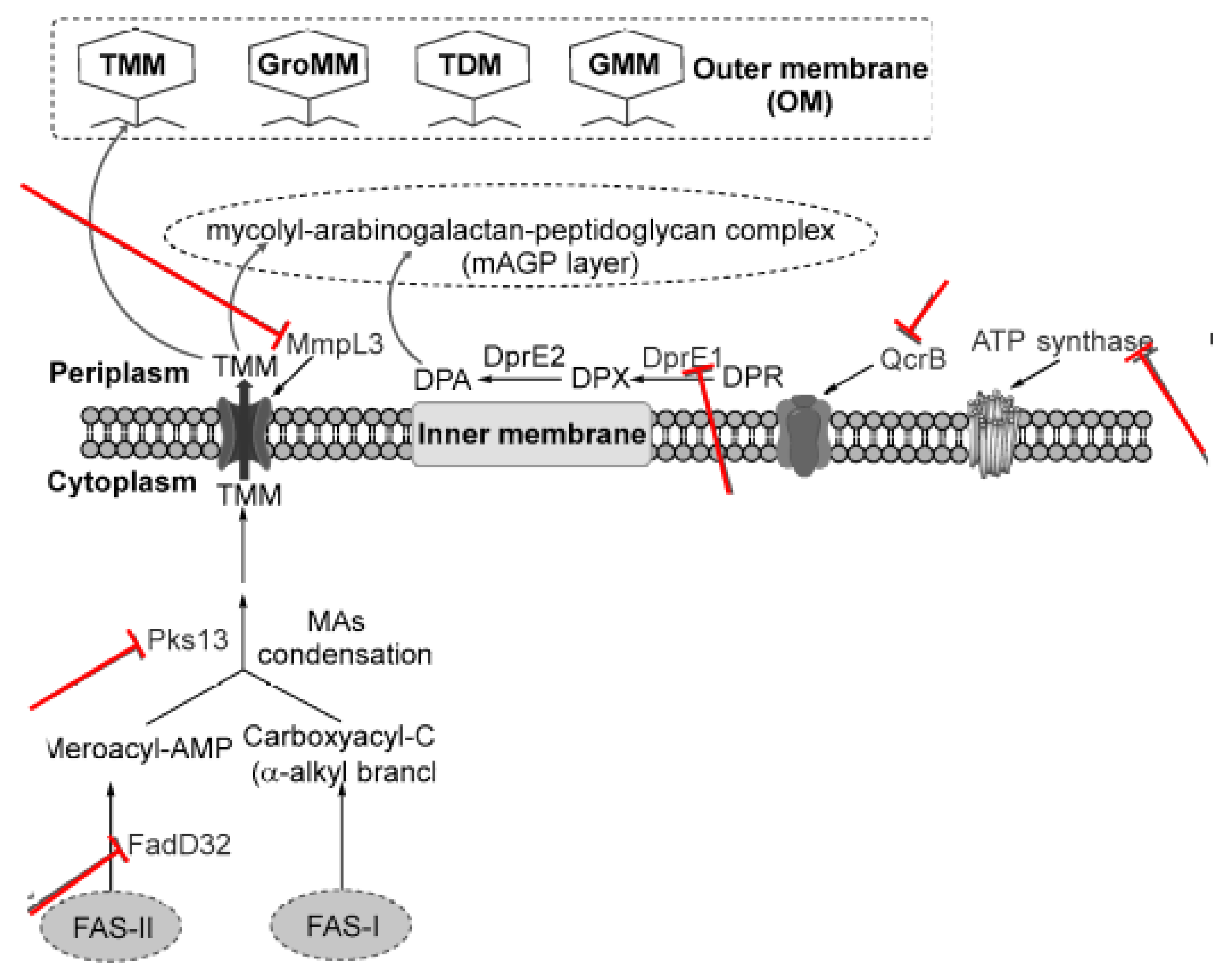

3. Current Tuberculosis Drug Targets and Validated Drug Candidates in Actinobacteria

3.1. Targeting the DNA Replication and Protein Synthesis (Transcription and Translation)

3.2. Targeting Cell Wall/Peptidoglycan Biosynthesis

3.3. Targeting Arabinogalactan

3.4. Targeting Bytochrome b Subunit QcrB

3.5. Targeting Clp Proteases

| Target | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Gyrase B, Leucyl tRNA synthetase, rRNA, RNA Polymerase | DNA replication and protein synthesis | Shetye et al., 2020; Alsayed & Gunosewoyo, 2023 |

| MurX, l,d-traspeptidases, l,d-transpeptidases + β lactamase, Lipid II | peptidoglycan biosynthesis | Capela et al., 2023 |

| WecA, DprE1 (Covalent inhibitors), DprE1 (Noncovalent inhibitors) | arabinogalactan biosynthesis | Capela et al., 2023 |

| MmpL3, InhA, β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (kasA), Inhibition of methoxy and keto mycolic acid (exact target unknown) | mycolic acid biosynthesis | Stec et al., 2016 |

| ATP synthase (AtpE), Cytochrome bc1/aa3 super, NDH-2, MenA, MenG, Isocitrate lyase (ICL) | energy metabolism | Haagsma et al., 2009 |

| ClpC | proteolysis | Culp & Wright, 2017 |

| Glutamine Synthetase GlnA1 | Primary metabolism, glutamine synthesis | Eisenberg et al., 2000 |

| Gamma-Glutamylpolyamine Synthetase GlnA3 | Polyamine metabolism | Krysenko et al., 2025 |

3.6. Targeting Primary Metabolism

3.6.1. Targeting Carbon Metabolism

3.6.2. Targeting Sulfur Metabolism

3.6.3. Targeting Phosphate/ATP Metabolism

3.6.4. Targeting Nitrogen and Metabolism of Polyamines

4. Drug Repurposing Targeting Polyamines in Actinobacteria

4.1. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) as Drug Targets for TB

4.2. The Synergy of Abscisic Acid and Nitric Oxide as a Therapeutic Target

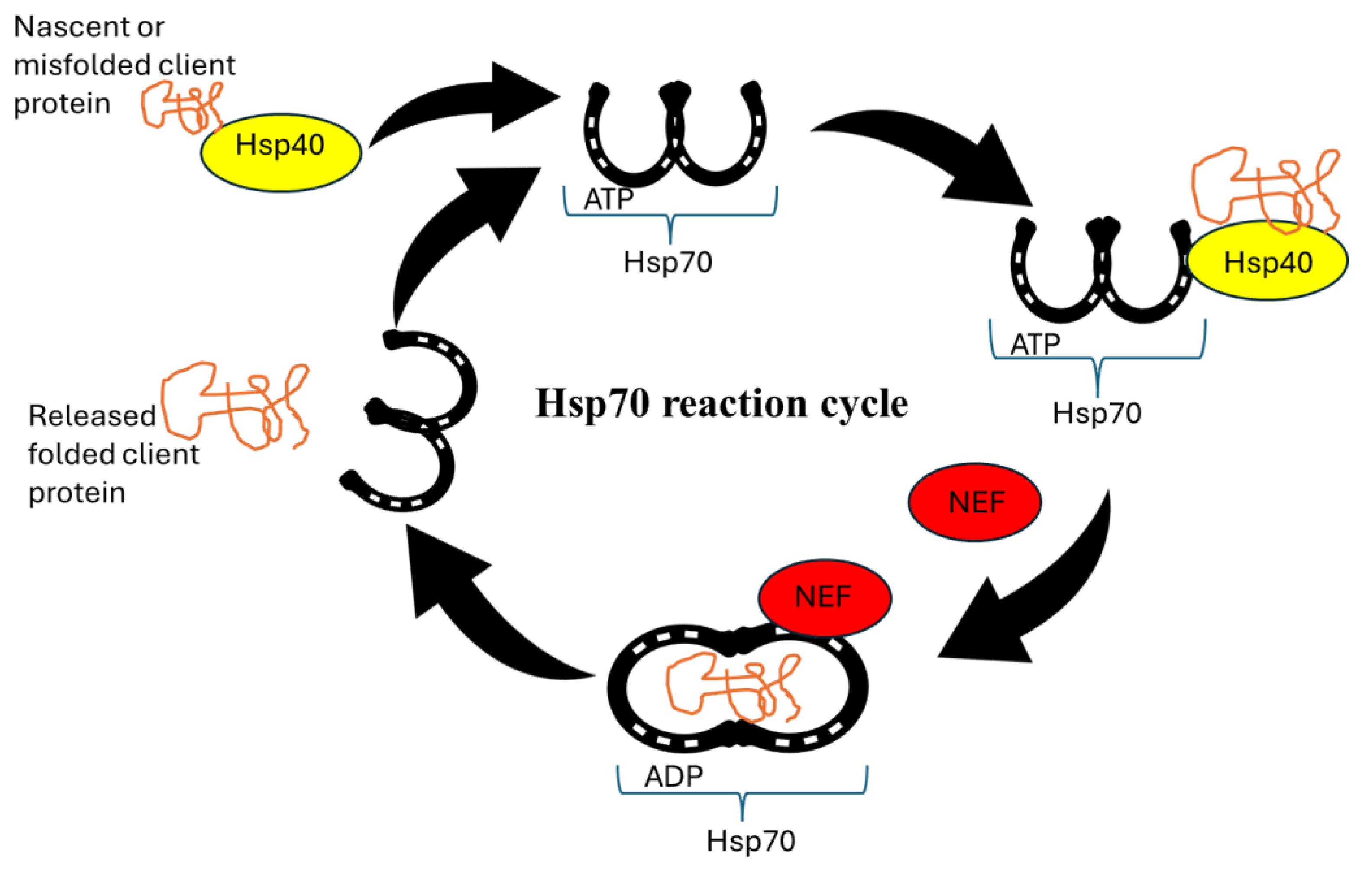

4.3. Molecular Chaperones as Drug Targets

4.4. Targeting Chaperone Networks

5. Combination Therapies for Actinobacteria Treatments

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. 2023. Global tuberculosis report; Geneva; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Natarajan, A.; Beena, P.; Devnikar, A.V.; Mali, S. A systemic review on tuberculosis. Indian J. Tuberc. 2020, 67, 295–311. [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, A.; Martinez, L.; Gupta, R.K.; Hamada, Y.; Ness, T.; Kay, A.; Bonnet, M.; Sester, M.; Kaufmann, S.H.; Lange, C.; et al. Tuberculosis prevention: current strategies and future directions. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 30, 1123–1130. [CrossRef]

- Gouzy, A.; Poquet, Y.; Neyrolles, O. Nitrogen metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis physiology and virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 729–737. [CrossRef]

- Mazlan, M.K.N.; Tazizi, M.H.D.M.; Ahmad, R.; Noh, M.A.A.; Bakhtiar, A.; Wahab, H.A.; Gazzali, A.M. Antituberculosis Targeted Drug Delivery as a Potential Future Treatment Approach. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 908. [CrossRef]

- Capela, R.; Félix, R.; Clariano, M.; Nunes, D.; Perry, M.d.J.; Lopes, F. Target Identification in Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10482. [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, S.S.R.; Gunosewoyo, H. Tuberculosis: Pathogenesis, Current Treatment Regimens and New Drug Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5202. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bustamante, E.; Gómez-Manzo, S.; Valle, A.D.O.F.d.; Arreguín-Espinosa, R.; Espitia-Pinzón, C.; Rodríguez-Flores, E. New Alternatives in the Fight against Tuberculosis: Possible Targets for Resistant Mycobacteria. Processes 2023, 11, 2793. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Li, J.; Cao, L.; Yan, C. Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence protein ESAT-6 influences M1/M2 polarization and macrophage apoptosis to regulate tuberculosis progression. Genes Genom. 2023, 46, 37–47. [CrossRef]

- Muraille, E.; Leo, O.; Moser, M. Th1/Th2 Paradigm Extended: Macrophage Polarization as an Unappreciated Pathogen-Driven Escape Mechanism? Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 603. [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Emani, C.S.; Bäuerle, M.; Oswald, M.; Kulik, A.; Meyners, C.; Hillemann, D.; Merker, M.; Prosser, G.; Wohlers, I.; et al. GlnA3 Mt is able to glutamylate spermine but it is not essential for the detoxification of spermine in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 2025, 207, e0043924. [CrossRef]

- Emani, C.S.; Reiling, N. Spermine enhances the activity of anti-tuberculosis drugs. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0356823. [CrossRef]

- Pai M, Behr MA, Dowdy D, Dheda K, Divangahi M, Boehme CC, Ginsberg A, Swaminathan S, Spigelman M, Getahun H. 2016. Tuberculosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2:16076. [CrossRef]

- Siavashifar, M.; Rezaei, F.; Motallebirad, T.; Azadi, D.; Absalan, A.; Naserramezani, Z.; Golshani, M.; Jafarinia, M.; Ghaffari, K. Species diversity and molecular analysis of opportunistic Mycobacterium, Nocardia and Rhodococcus isolated from the hospital environment in a developing country, a potential resources for nosocomial infection. Genes Environ. 2021, 43, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Miller-Fleming, L.; Olin-Sandoval, V.; Campbell, K.; Ralser, M. Remaining mysteries of Molecular Biology: The role of polyamines in the cell. [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Wohlleben, W. Polyamine and Ethanolamine Metabolism in Bacteria as an Important Component of Nitrogen Assimilation for Survival and Pathogenicity. Med Sci. 2022, 10, 40. [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Mazumder, A.; Sikdar, S.; Zhao, Y.-M.; Hao, J.; Song, C.; Wang, Y.; Sarkar, R.; Islam, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Streptomyces: The biofactory of secondary metabolites. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 968053. [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Wohlleben, W. Role of Carbon, Nitrogen, Phosphate and Sulfur Metabolism in Secondary Metabolism Precursor Supply in Streptomyces spp.. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1571. [CrossRef]

- Hamana K, Matsuzaki S. 1987. Distribution of polyamines in actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiology Letters 41:211-215. [CrossRef]

- Paulin, L.G.; E Brander, E.; Pösö, H.J. Specific inhibition of spermidine synthesis in Mycobacteria spp. by the dextro isomer of ethambutol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1985, 28, 157–159. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Tyagi, A.K. Role of polyamines in the synthesis of RNA in mycobacteria. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1987, 78, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Kusano T, Suzuki H. 2015. Polyamines: a universal molecular nexus for growth, survival, and specialized metabolism. Springer, Tokyo.

- Davis, R.H.; Ristow, J.L. Polyamine toxicity in Neurospora crassa: Protective role of the vacuole. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1991, 285, 306–311. [CrossRef]

- Pegg, A.E. Toxicity of Polyamines and Their Metabolic Products. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2013, 26, 1782–1800. [CrossRef]

- Lasbury, M.E.; Merali, S.; Durant, P.J.; Tschang, D.; Ray, C.A.; Lee, C.-H. Polyamine-mediated Apoptosis of Alveolar Macrophages during Pneumocystis Pneumonia. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11009–11020. [CrossRef]

- Tome, E.M.; Fiser, M.S.; Payne, M.C.; Gerner, W.E. Excess putrescine accumulation inhibits the formation of modified eukaryotic initiation factor 5A (eIF-5A) and induces apoptosis. Biochem. J. 1997, 328, 847–854. [CrossRef]

- Norris, V.; Reusch, R.N.; Igarashi, K.; Root-Bernstein, R. Molecular complementarity between simple, universal molecules and ions limited phenotype space in the precursors of cells. Biol. Direct 2015, 10, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.L.; Reitzer, L. Pathway and Enzyme Redundancy in Putrescine Catabolism in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 4080–4088. [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, S.; Oda, S.; Tsuboi, Y.; Kim, H.G.; Oshida, M.; Kumagai, H.; Suzuki, H. γ-Glutamylputrescine Synthetase in the Putrescine Utilization Pathway of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 19981–19990. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; He, W.; Lu, C.-D. Functional Characterization of Seven γ-Glutamylpolyamine Synthetase Genes and the bauRABCD Locus for Polyamine and β-Alanine Utilization in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 3923–3930. [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.; Barnes, N.; Speight, R.; Keane, M.A. Genomic organisation, activity and distribution analysis of the microbial putrescine oxidase degradation pathway. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 36, 457–466. [CrossRef]

- Forouhar, F.; Lee, I.-S.; Vujcic, J.; Vujcic, S.; Shen, J.; Vorobiev, S.M.; Xiao, R.; Acton, T.B.; Montelione, G.T.; Porter, C.W.; et al. Structural and Functional Evidence for Bacillus subtilis PaiA as a Novel N1-Spermidine/Spermine Acetyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 40328–40336. [CrossRef]

- Campilongo, R.; Di Martino, M.L.; Marcocci, L.; Pietrangeli, P.; Leuzzi, A.; Grossi, M.; Casalino, M.; Nicoletti, M.; Micheli, G.; Colonna, B.; et al. Molecular and Functional Profiling of the Polyamine Content in Enteroinvasive E. coli: Looking into the Gap between Commensal E. coli and Harmful Shigella. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106589. [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Okoniewski, N.; Kulik, A.; Matthews, A.; Grimpo, J.; Wohlleben, W.; Bera, A. Gamma-Glutamylpolyamine Synthetase GlnA3 Is Involved in the First Step of Polyamine Degradation Pathway in Streptomyces coelicolor M145. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 726. [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Matthews, A.; Busche, T.; Bera, A.; Wohlleben, W. Poly- and Monoamine Metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor: The New Role of Glutamine Synthetase-Like Enzymes in the Survival under Environmental Stress. Microb. Physiol. 2021, 31, 233–247. [CrossRef]

- Krysenko S, Okoniewski N, Nentwich M, Matthews A, Bäuerle M, Zinser A, Busche T, Kulik A, Gursch S, Kemeny A. 2022. A second gamma-Glutamylpolyamine synthetase, GlnA2, is involved in polyamine catabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor. Int J Mol Sci 23:3752. [CrossRef]

- Purder PL, Meyners C, Krysenko S, Funk J, Wohlleben W, Hausch F. 2022. Mechanism-Based Design of the First GlnA4-Specific Inhibitors. Chembiochem 23:e202200312. [CrossRef]

- Harth, G.; Masleša-Galić, S.; Tullius, M.V.; Horwitz, M.A. All four Mycobacterium tuberculosis glnA genes encode glutamine synthetase activities but only GlnA1 is abundantly expressed and essential for bacterial homeostasis. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 58, 1157–1172. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Gill, H.S.; Pfluegl, G.M.; Rotstein, S.H. Structure–function relationships of glutamine synthetases. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Protein Struct. Mol. Enzym. 2000, 1477, 122–145. [CrossRef]

- Michael, A.J. Polyamine function in archaea and bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 18693–18701. [CrossRef]

- Bryk, R.; Arango, N.; Venugopal, A.; Warren, J.D.; Park, Y.-H.; Patel, M.S.; Lima, C.D.; Nathan, C. Triazaspirodimethoxybenzoyls as Selective Inhibitors of Mycobacterial Lipoamide Dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 1616–1627. [CrossRef]

- Bald, D.; Villellas, C.; Lu, P.; Koul, A. Targeting Energy Metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a New Paradigm in Antimycobacterial Drug Discovery. mBio 2017, 8, e00272-17. [CrossRef]

- Rexer, H.U.; Schäberle, T.; Wohlleben, W.; Engels, A. Investigation of the functional properties and regulation of three glutamine synthetase-like genes in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Arch. Microbiol. 2006, 186, 447–458. [CrossRef]

- Harth, G.; Clemens, D.L.; A Horwitz, M. Glutamine synthetase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: extracellular release and characterization of its enzymatic activity.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1994, 91, 9342–9346. [CrossRef]

- Paulin, L.G.; E Brander, E.; Pösö, H.J. Specific inhibition of spermidine synthesis in Mycobacteria spp. by the dextro isomer of ethambutol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1985, 28, 157–159. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Tyagi, A.K. Role of polyamines in the synthesis of RNA in mycobacteria. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1987, 78, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Culp, E.; Wright, G.D. Bacterial proteases, untapped antimicrobial drug targets. J. Antibiot. 2016, 70, 366–377. [CrossRef]

- Malm, S.; Tiffert, Y.; Micklinghoff, J.; Schultze, S.; Joost, I.; Weber, I.; Horst, S.; Ackermann, B.; Schmidt, M.; Wohlleben, W.; et al. The roles of the nitrate reductase NarGHJI, the nitrite reductase NirBD and the response regulator GlnR in nitrate assimilation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 2009, 155, 1332–1339. [CrossRef]

- Tiffert, Y.; Supra, P.; Wurm, R.; Wohlleben, W.; Wagner, R.; Reuther, J. The Streptomyces coelicolor GlnR regulon: identification of new GlnR targets and evidence for a central role of GlnR in nitrogen metabolism in actinomycetes. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 67, 861–880. [CrossRef]

- Gawronski, J.D.; Benson, D.R. Microtiter assay for glutamine synthetase biosynthetic activity using inorganic phosphate detection. Anal. Biochem. 2004, 327, 114–118. [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; De Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.S.; Pfluegl, G.M.U.; Eisenberg, D. Multicopy Crystallographic Refinement of a Relaxed Glutamine Synthetase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis Highlights Flexible Loops in the Enzymatic Mechanism and Its Regulation. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 9863–9872. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, Z.S.; Rather, M.A.; Maqbool, M.; Ahmad, Z. Drug targets exploited in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Pitfalls and promises on the horizon. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 1733–1747. [CrossRef]

- Mougous, J.D.; E Green, R.; Williams, S.J.; E Brenner, S.; Bertozzi, C.R. Sulfotransferases and Sulfatases in Mycobacteria. Chem. Biol. 2002, 9, 767–776. [CrossRef]

- Hatzios, S.K.; Bertozzi, C.R. The Regulation of Sulfur Metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLOS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002036. [CrossRef]

- Shetye, G.S.; Franzblau, S.G.; Cho, S. New tuberculosis drug targets, their inhibitors, and potential therapeutic impact. Transl. Res. 2020, 220, 68–97. [CrossRef]

- Brotzoesterhelt, H.; Brunner, N. How many modes of action should an antibiotic have?. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2008, 8, 564–573. [CrossRef]

- Haagsma, A.C.; Abdillahi-Ibrahim, R.; Wagner, M.J.; Krab, K.; Vergauwen, K.; Guillemont, J.; Andries, K.; Lill, H.; Koul, A.; Bald, D. Selectivity of TMC207 towards mycobacterial ATP synthase compared with that towards the eukaryotic homologue. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 1290–1292. [CrossRef]

- Radkov, A.D.; Hsu, Y.-P.; Booher, G.; VanNieuwenhze, M.S. Imaging Bacterial Cell Wall Biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2018, 87, 991–1014. [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, W.W.; Jones, T.A.; Mowbray, S.L. Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase in complex with a transition-state mimic provides functional insights. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102, 10499–10504. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson MT, Mowbray SL. 2012. Crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthethase in complex with imidazopyridine inhibitor ((4-(6-Bromo-3-(Butylamino)imidazo(1,2-A)Pyridin-2-YL)Phenoxy) Acetic acid) and L-Methionine-S-Sulfoximine phosphate. MedChemComm 3:620. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson MT, Mowbray SL. 2012. Crystal structure of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Glutamine Synthetase in complex with tri-substituted imidazole inhibitor (4-(2-tert-butyl- 4-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)-1H-imidazol-5-yl)pyridin-2-amine) and L- methionine-S-sulfoximine phosphate. J Med Chem 55.

- Benkert, P.; Biasini, M.; Schwede, T. Toward the estimation of the absolute quality of individual protein structure models. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 343–350. [CrossRef]

- Hooft, R.W.; Sander, C.; Vriend, G. Objectively judging the quality of a protein structure from a Ramachandran plot. Bioinformatics 1997, 13, 425–430. [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.B.; Arendall, W.B., III; Headd, J.J.; Keedy, D.A.; Immormino, R.M.; Kapral, G.J.; Murray, L.W.; Richardson, J.S.; Richardson, D.C. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 12–21.

- Ladner, J.E.; Atanasova, V.; Dolezelova, Z.; Parsons, J.F. Structure and Activity of PA5508, a Hexameric Glutamine Synthetase Homologue. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 10121–10123. [CrossRef]

- Chanphai, P.; Thomas, T.; Tajmir-Riahi, H. Conjugation of biogenic and synthetic polyamines with serum proteins: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 92, 515–522. [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.Y.; de Carvalho, L.P.S.; Bryk, R.; Ehrt, S.; Marrero, J.; Park, S.W.; Schnappinger, D.; Venugopal, A.; Nathan, C. Central carbon metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: an unexpected frontier. Trends Microbiol. 2011, 19, 307–314. [CrossRef]

- Sakharkar, K. R., Sakharkar, M. K., & Chow, V. T. (2008). Biocomputational strategies for microbial drug target identification. Methods in molecular medicine, 142, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, K.R.; Sauer, R.T. Substrate delivery by the AAA+ ClpX and ClpC1 unfoldases activates the mycobacterial ClpP1P2 peptidase. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 93, 617–628. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Dubnau, E.; Quemard, A.; Balasubramanian, V.; Um, K.S.; Wilson, T.; Collins, D.; de Lisle, G.; Jacobs, W.R. inhA, a Gene Encoding a Target for Isoniazid and Ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 1994, 263, 227–230. [CrossRef]

- Bayer, E.; Gugel, K.H.; Hägele, K.; Hagenmaier, H.; Jessipow, S.; König, W.A.; Zähner, H. Stoffwechselprodukte von Mikroorganismen. 98. Phosphinothricin und Phosphinothricyl-Alanyl-Alanin [Metabolic products of microorganisms. 98. Phosphinothricin and phosphinothricyl-alanyl-analine]. Helvetica Chim. Acta 1972, 55, 224–239. [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Purder, P.; Hausch, F.; Wohlleben, W. Neuartige synthetische Wirkstoffe zur Tuberkulosebekämpfung. BIOspektrum 2024, 30, 819–821. [CrossRef]

- Selim, M.S.M.; Abdelhamid, S.A.; Mohamed, S.S. Secondary metabolites and biodiversity of actinomycetes. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 72–13. [CrossRef]

- Parish, T.; Stoker, N.G. Use of a flexible cassette method to generate a double unmarked Mycobacterium tuberculosis tlyA plcABC mutant by gene replacement. Microbiology 2000, 146, 1969–1975. [CrossRef]

- Sao Emani C, Williams MJ, Van Helden PD, Taylor MJC, Carolis C, Wiid IJ, Baker B. 2018. Generation and characterization of thiol-deficient Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants. Sci Data 5:180184.

- De Rossi, E.; Branzoni, M.; Cantoni, R.; Milano, A.; Riccardi, G.; Ciferri, O. mmr, a Mycobacterium tuberculosis Gene Conferring Resistance to Small Cationic Dyes and Inhibitors. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 6068–6071. [CrossRef]

- Zelmer, A.; Carroll, P.; Andreu, N.; Hagens, K.; Mahlo, J.; Redinger, N.; Robertson, B.D.; Wiles, S.; Ward, T.H.; Parish, T.; et al. A new in vivo model to test anti-tuberculosis drugs using fluorescence imaging. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 1948–1960. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P.; Schreuder, L.J.; Muwanguzi-Karugaba, J.; Wiles, S.; Robertson, B.D.; Ripoll, J.; Ward, T.H.; Bancroft, G.J.; Schaible, U.E.; Parish, T. Sensitive Detection of Gene Expression in Mycobacteria under Replicating and Non-Replicating Conditions Using Optimized Far-Red Reporters. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9823. [CrossRef]

- Stec, J.; Onajole, O.K.; Lun, S.; Guo, H.; Merenbloom, B.; Vistoli, G.; Bishai, W.R.; Kozikowski, A.P. Indole-2-carboxamide-based MmpL3 Inhibitors Show Exceptional Antitubercular Activity in an Animal Model of Tuberculosis Infection. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 6232–6247. [CrossRef]

- Boutte, C.C.; E Baer, C.; Papavinasasundaram, K.; Liu, W.; Chase, M.R.; Meniche, X.; Fortune, S.M.; Sassetti, C.M.; Ioerger, T.R.; Rubin, E.J. A cytoplasmic peptidoglycan amidase homologue controls mycobacterial cell wall synthesis. eLife 2016, 5. [CrossRef]

- Shaner, N.C.; Campbell, R.E.; Steinbach, P.A.; Giepmans, B.N.; Palmer, A.E.; Tsien, R.Y. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 1567–1572. [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.G.T.; Herbert, D.; Tempest, D.W. Chapter XIII The Continuous Cultivation of Micro-organisms. Methods Microbiol. 1970, 2, 277–327. [CrossRef]

- Gust, B.; Challis, G.L.; Fowler, K.; Kieser, T.; Chater, K.F. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 1541–1546. [CrossRef]

- Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. 2000. Practical streptomyces genetics, vol 291. John Innes Foundation Norwich, Berlin.

- Jumde, R.P.; Guardigni, M.; Gierse, R.M.; Alhayek, A.; Zhu, D.; Hamid, Z.; Johannsen, S.; Elgaher, W.A.M.; Neusens, P.J.; Nehls, C.; et al. Hit-optimization using target-directed dynamic combinatorial chemistry: development of inhibitors of the anti-infective target 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 7775–7785. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.J.; Nash, D.R.; Steele, L.C.; Steingrube, V. Susceptibility testing of slowly growing mycobacteria by a microdilution MIC method with 7H9 broth. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1986, 24, 976–981. [CrossRef]

- Palomino, J.-C.; Martin, A.; Camacho, M.; Guerra, H.; Swings, J.; Portaels, F. Resazurin Microtiter Assay Plate: Simple and Inexpensive Method for Detection of Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2720–2. [CrossRef]

- Merker, M.; Kohl, T.A.; Roetzer, A.; Truebe, L.; Richter, E.; Rüsch-Gerdes, S.; Fattorini, L.; Oggioni, M.R.; Cox, H.; Varaine, F.; et al. Whole Genome Sequencing Reveals Complex Evolution Patterns of Multidrug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing Strains in Patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82551. [CrossRef]

- Andreu, N.; Zelmer, A.; Fletcher, T.; Elkington, P.T.; Ward, T.H.; Ripoll, J.; Parish, T.; Bancroft, G.J.; Schaible, U.; Robertson, B.D.; et al. Optimisation of Bioluminescent Reporters for Use with Mycobacteria. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10777. [CrossRef]

- Biasini, M.; Bienert, S.; Waterhouse, A.; Arnold, K.; Studer, G.; Schmidt, T.; Kiefer, F.; Cassarino, T.G.; Bertoni, M.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W252–W258. [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, M.; Kiefer, F.; Biasini, M.; Bordoli, L.; Schwede, T. Modeling protein quaternary structure of homo- and hetero-oligomers beyond binary interactions by homology. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Biasini, M.; Schmidt, T.; Bienert, S.; Mariani, V.; Studer, G.; Haas, J.; Johner, N.; Schenk, A.D.; Philippsen, A.; Schwede, T. OpenStructure: an integrated software framework for computational structural biology. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Struct. Biol. 2013, 69, 701–709. [CrossRef]

- Guex, N.; Peitsch, M.C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-Pdb Viewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 2714–2723. [CrossRef]

- Zheng L, Baumann U, Reymond J-L. 2004. An efficient one-step site-directed and site-saturation mutagenesis protocol. Nucleic Acids Res 32:e115-e115.

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows—Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. feature Counts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [CrossRef]

- Latour, Y.L.; Gobert, A.P.; Wilson, K.T. The role of polyamines in the regulation of macrophage polarization and function. Amino Acids 2019, 52, 151–160. [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.M.; Hards, K.; Dunn, E.; Heikal, A.; Nakatani, Y.; Greening, C.; Crick, D.C.; Fontes, F.L.; Pethe, K.; Hasenoehrl, E.; et al. Oxidative Phosphorylation as a Target Space for Tuberculosis: Success, Caution, and Future Directions. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.; Qi, Y.; Yan, X.; Qi, G.; Peng, Q. The progress of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug targets. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1455715. [CrossRef]

- Paritala, H.; Carroll, K.S. New Targets and Inhibitors of Mycobacterial Sulfur Metabolism. Infect. Disord. - Drug Targets 2013, 13, 85–115. [CrossRef]

- Rath, V.L.; Verdugo, D.; Hemmerich, S. Sulfotransferase structural biology and inhibitor discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2004, 9, 1003–1011. [CrossRef]

- Bhave, D.P.; Iii, W.B.M.; Carroll, K.S. Drug Targets in Mycobacterial Sulfur Metabolism. Infect. Disord. - Drug Targets 2007, 7, 140–158. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, E.; Ding, S.; Schultz, P.G.; Wong, C.-H. A Potent and Highly Selective Sulfotransferase Inhibitor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 14524–14525. [CrossRef]

- Silver, R.F.; Myers, A.J.; Jarvela, J.; Flynn, J.; Rutledge, T.; Bonfield, T.; Lin, P.L. Diversity of Human and Macaque Airway Immune Cells at Baseline and during Tuberculosis Infection. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016, 55, 899–908. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, G.J.; Fang, L.; Schaefer, J.; Singh, S.; Bowman, G.R.; Wencewicz, T.A. Mechanistic Basis for ATP-Dependent Inhibition of Glutamine Synthetase by Tabtoxinine-β-lactam. Biochemistry 2017, 57, 117–135. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.G.; Dubos, R.J. The effect of spermine on tubercle bacilli. J. Exp. Med. 1952, 95, 191–208. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.S.; Spontak, J.S.; Klapper, D.G.; Richardson, A.R. Arginine catabolic mobile element encoded speG abrogates the unique hypersensitivity of Staphylococcus aureus to exogenous polyamines. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 82, 9–20. [CrossRef]

- Tullius, M.V.; Harth, G.; Horwitz, M.A. Glutamine Synthetase GlnA1 Is Essential for Growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Human THP-1 Macrophages and Guinea Pigs. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 3927–36. [CrossRef]

- Kruh, N.A.; Troudt, J.; Izzo, A.; Prenni, J.; Dobos, K.M. Portrait of a Pathogen: The Mycobacterium tuberculosis Proteome In Vivo. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13938. [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.T.; Brosch, R.; Parkhill, J.A.; Garnier, T.; Churcher, C.; Harris, D.R.; Gordon, S.V.; Eiglmeier, K.; Gas, S.; Barry, C.E., III; et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 1998, 393, 537–544. [CrossRef]

- Sassetti, C.M.; Boyd, D.H.; Rubin, E.J. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 77–84. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, B.; DeJesus, M.A.; Poulton, N.C.; Zhang, W.; Engelhart, C.A.; Zaveri, A.; Lavalette, S.; Ruecker, N.; Trujillo, C.; Wallach, J.B.; et al. Genome-wide gene expression tuning reveals diverse vulnerabilities of M. tuberculosis. Cell 2021, 184, 4579–4592.e24. [CrossRef]

- De Rossi, E.; Arrigo, P.; Bellinzoni, M.; Silva, P.E.A.; Martin, C.; Aínsa, J.A.; Guglierame, P.; Riccardi, G. The Multidrug Transporters Belonging to Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Med. 2002, 8, 714–724. [CrossRef]

- Balganesh, M.; Dinesh, N.; Sharma, S.; Kuruppath, S.; Nair, A.V.; Sharma, U. Efflux Pumps of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Play a Significant Role in Antituberculosis Activity of Potential Drug Candidates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 2643–2651. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, N.K.; Mehra, S.; Kaushal, D. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis Sigma Factor Network Responds to Cell-Envelope Damage by the Promising Anti-Mycobacterial Thioridazine. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10069. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.; Villellas, C.; Bailo, R.; Viveiros, M.; Aínsa, J.A. Role of the Mmr Efflux Pump in Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 751–757. [CrossRef]

- Krysenko, S.; Matthews, A.; Okoniewski, N.; Kulik, A.; Girbas, M.G.; Tsypik, O.; Meyners, C.S.; Hausch, F.; Wohlleben, W.; Bera, A. Initial Metabolic Step of a Novel Ethanolamine Utilization Pathway and Its Regulation in Streptomyces coelicolor M145. mBio 2019, 10, e00326-19. [CrossRef]

- Bullock WO, Fernandez JM, Short JM. 1987. XL1-blue: a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta-galactosidase selection. BioTechniques 5:376.

- Simon, R.; Priefer, U.; Pühler, A. A Broad Host Range Mobilization System for In Vivo Genetic Engineering: Transposon Mutagenesis in Gram Negative Bacteria. Bio/Technology 1983, 1, 784–791. [CrossRef]

- Davanloo, P.; Rosenberg, A.H.; Dunn, J.J.; Studier, F.W. Cloning and expression of the gene for bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1984, 81, 2035–2039. [CrossRef]

- Kubica, G.P.; Kim, T.H.; Dunbar, F.P. Designation of Strain H37Rv as the Neotype of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1972, 22, 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Krysenko S, and Wohlleben W. Polyamine and Ethanolamine Metabolism in Bacteria as an Important Component of Nitrogen Assimilation for Survival and Pathogenicity. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 40. [CrossRef]

- León, J.; Castillo, M.C.; Coego, A.; Lozano-Juste, J.; Mir, R. Diverse functional interactions between nitric oxide and abscisic acid in plant development and responses to stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 65, 907–921. [CrossRef]

- Astier J, Gross I, Durner J (2018) Nitric oxide production in plants: an update. J. Exp. Bot. 69(14):3401–3411. [CrossRef]

- Bajeli, S.; Baid, N.; Kaur, M.; Pawar, G.P.; Chaudhari, V.D.; Kumar, A. Terminal Respiratory Oxidases: A Targetables Vulnerability of Mycobacterial Bioenergetics?. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.M.; Hards, K.; Dunn, E.; Heikal, A.; Nakatani, Y.; Greening, C.; Crick, D.C.; Fontes, F.L.; Pethe, K.; Hasenoehrl, E.; et al. Oxidative Phosphorylation as a Target Space for Tuberculosis: Success, Caution, and Future Directions. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [CrossRef]

- Gunjan, S.; Sharma, T.; Yadav, K.; Chauhan, B.S.; Singh, S.K.; Siddiqi, M.I.; Tripathi, R. Artemisinin Derivatives and Synthetic Trioxane Trigger Apoptotic Cell Death in Asexual Stages of Plasmodium. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 256. [CrossRef]

- Lievens, L.; Pollier, J.; Goossens, A.; Beyaert, R.; Staal, J. Abscisic Acid as Pathogen Effector and Immune Regulator. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 587. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Lan, W.; Wei, Z.; Yu, W.; Li, C. Interaction between ABA and NO in plants under abiotic stresses and its regulatory mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1330948. [CrossRef]

- Makhoba, X.H. Two sides of the same coin: heat shock proteins as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for some complex diseases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1491227. [CrossRef]

- Fournier, P.E.; Richet, H.; Weinstein, R.A. The Epidemiology and Control of Acinetobacter baumannii in Health Care Facilities. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 692–699. [CrossRef]

- Lolans, K.; Rice, T.W.; Munoz-Price, L.S.; Quinn, J.P. Multicity Outbreak of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates Producing the Carbapenemase OXA-40. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2941–2945. [CrossRef]

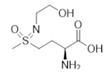

| Name | Mode of action | Reference | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

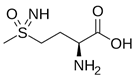

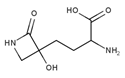

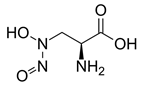

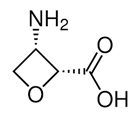

| Methionine sulfoximine (MetSox/MSO) | Potent ATP-dependent inactivator of GS. | Krajewski et al., 2005 |  |

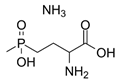

| Phosphinothricin (PPT) | Potent ATP-dependent inactivator of GS that is produced as part of a tripeptide antibiotic by Streptomyces viridochromogenes. | Bayer et al., 1972 |  |

| Tabtoxinine β-lactam | Potent ATP-dependent inactivator of GS produced by Pseudomonas pv. tabaci. | Patrick et al., 2018 |  |

| Alanosine | Antibiotic produced by Streptomyces alanosinicus. | Eisenberg et al., 2000 |  |

| Oxetin | Antibiotic produced by Streptomyces sp., inhibitor of GS | Eisenberg et al., 2000 |  |

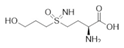

| 7b (PPU301) | Synthetic inactivator of the GS-like enzyme GlnA4 from Streptomyces coelicolor | Purder et al., 2022 |  |

| PPU268 | Synthetic inactivator of the GS-like enzyme GlnA2 from Streptomyces coelicolor | Krysenko et al., 2023 |  |

| Name | Roles | Inhibitor | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp90 (Grp94) | Holdase | Geldanamycin and its derivatives | These compounds bind to the N-terminal ATP-binding domain of Hsp90, inhibiting its chaperone activit |

| Hsp70 (Dnak) | Foldase | VER-155008 | A small molecule inhibitor that binds to the ATPase domain of Hsp70, inhibiting its activity |

| ClpB | Holdase | Ecumicin | A cyclic peptide that targets the ClpC1 ATPase component of the Clp protease complex, enhancing its ATPase activity but preventing proteolysis |

| Combination | Mechanism | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Colistin + Rifampicin | Synergistic effect | Multidrug-resistant strains |

| Tigecycline + Sulbactam | Enhanced efficacy | Severe infections |

| Meropenem + Polymyxin | Broad-spectrum activity | Carbapenem-resistant strains |

| Beta-lactam + Aminoglycoside | Synergistic effect | General use in resistant infection |

| Fluoroquinolone + Beta-lactam | Targeting different pathways | Reducing resistance development |

| Spermine + isoniazid, rifampicin, aminosalicylic acid, bedaquiline | Enchancing effect of spermine on conventional drugs | General use in resistant infection |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).