Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

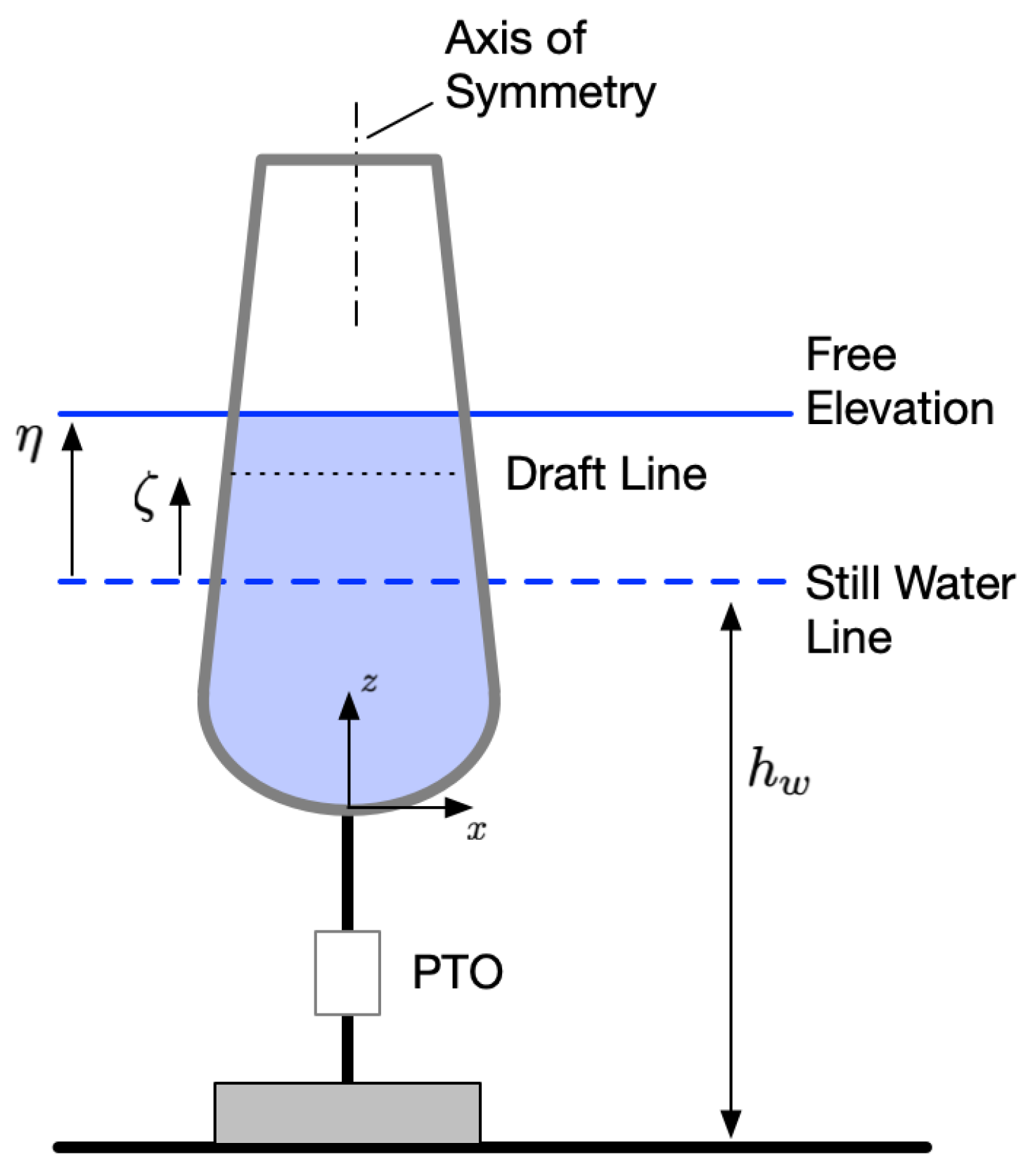

2. System Description

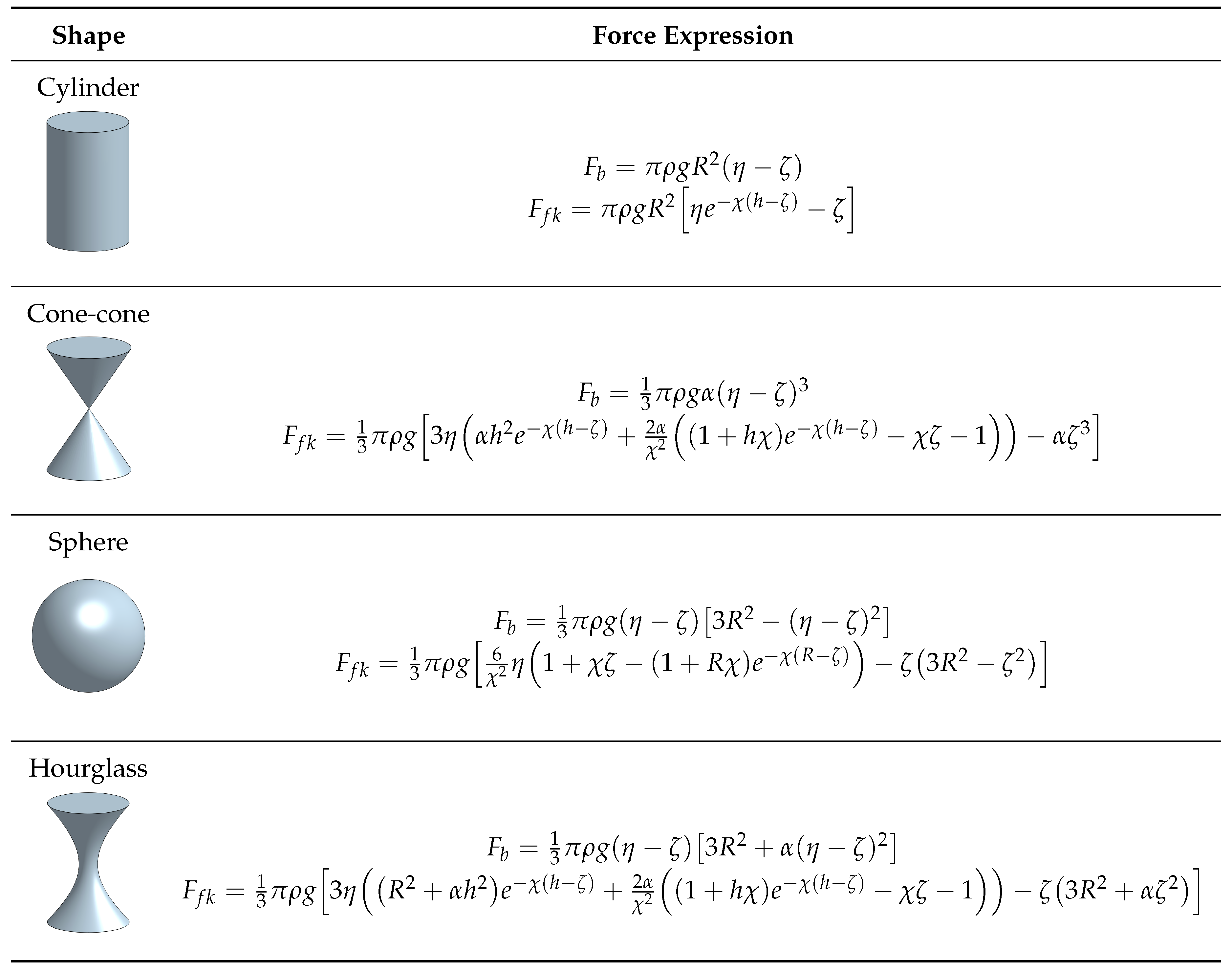

3. Derivation of

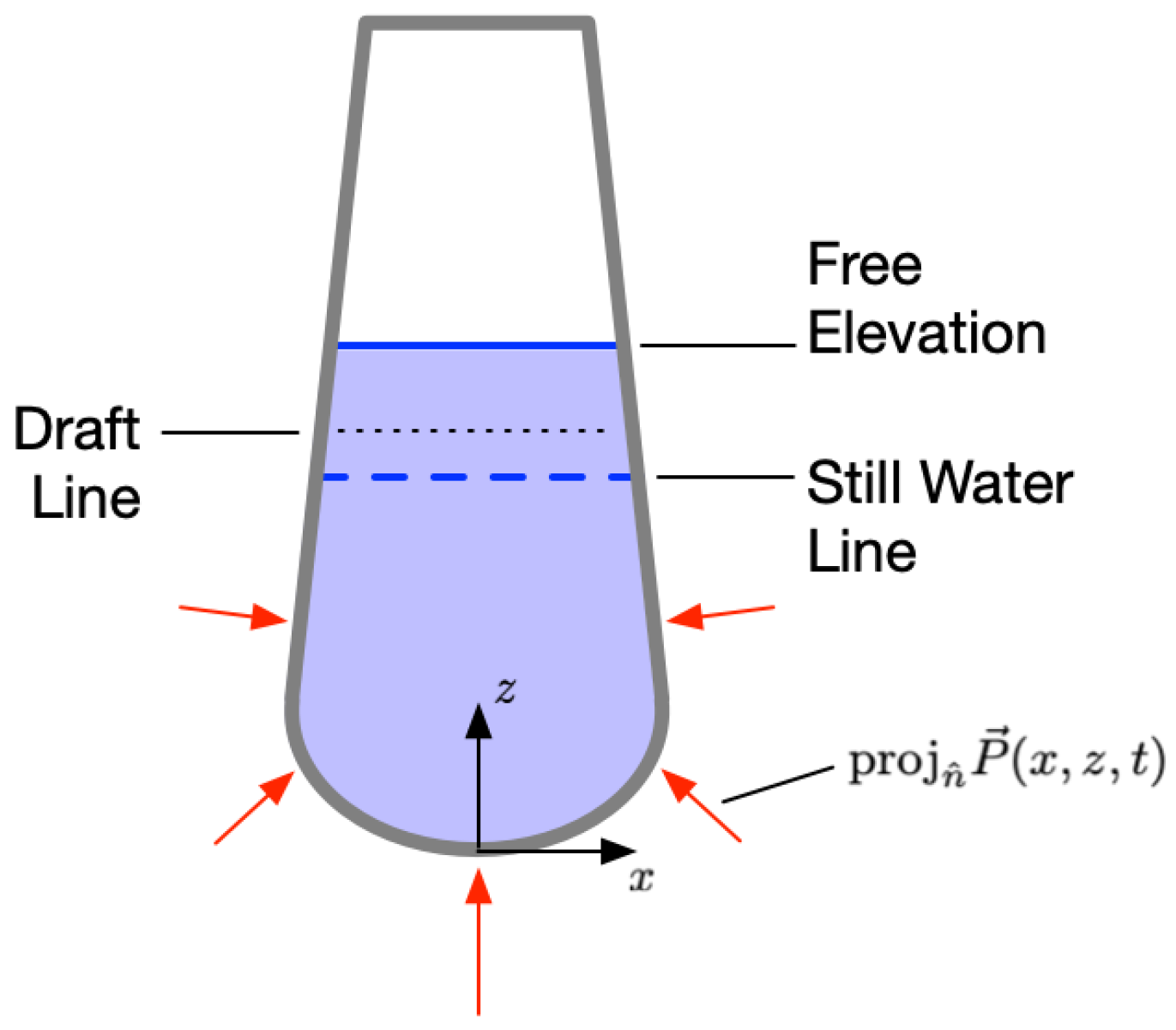

3.1. Pressure

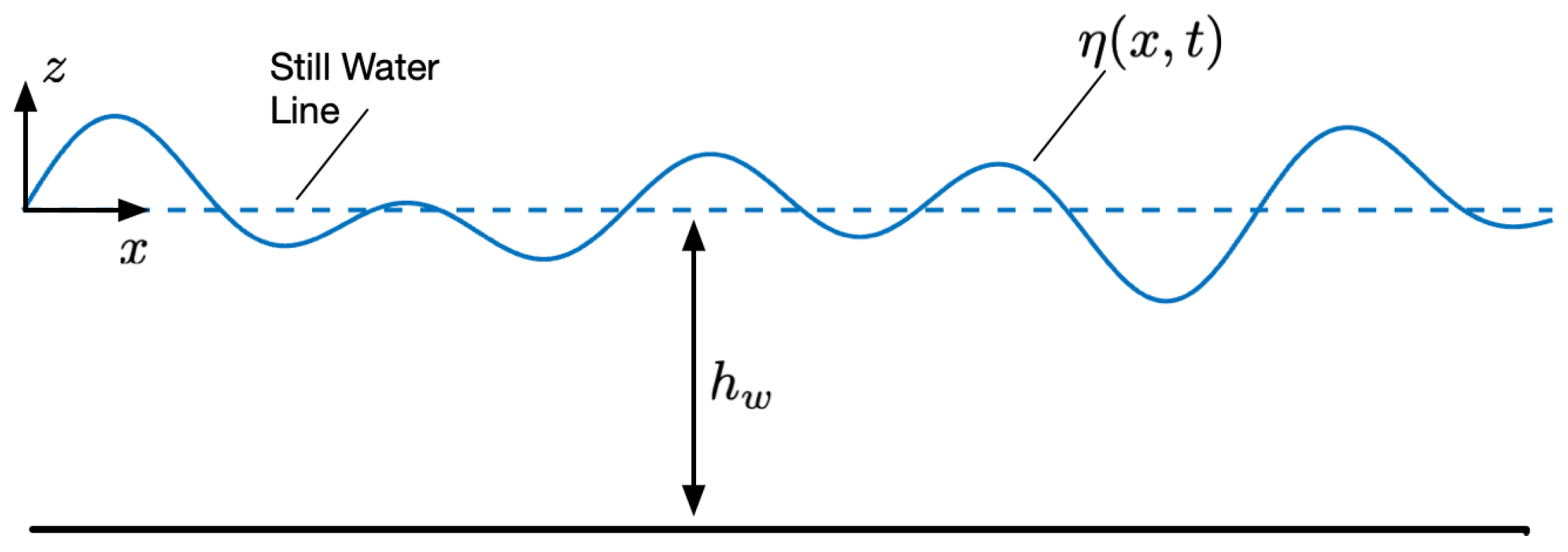

- Consideration of irregular waves of Eq. 1.

- Inclusion of flat-bottomed buoys.

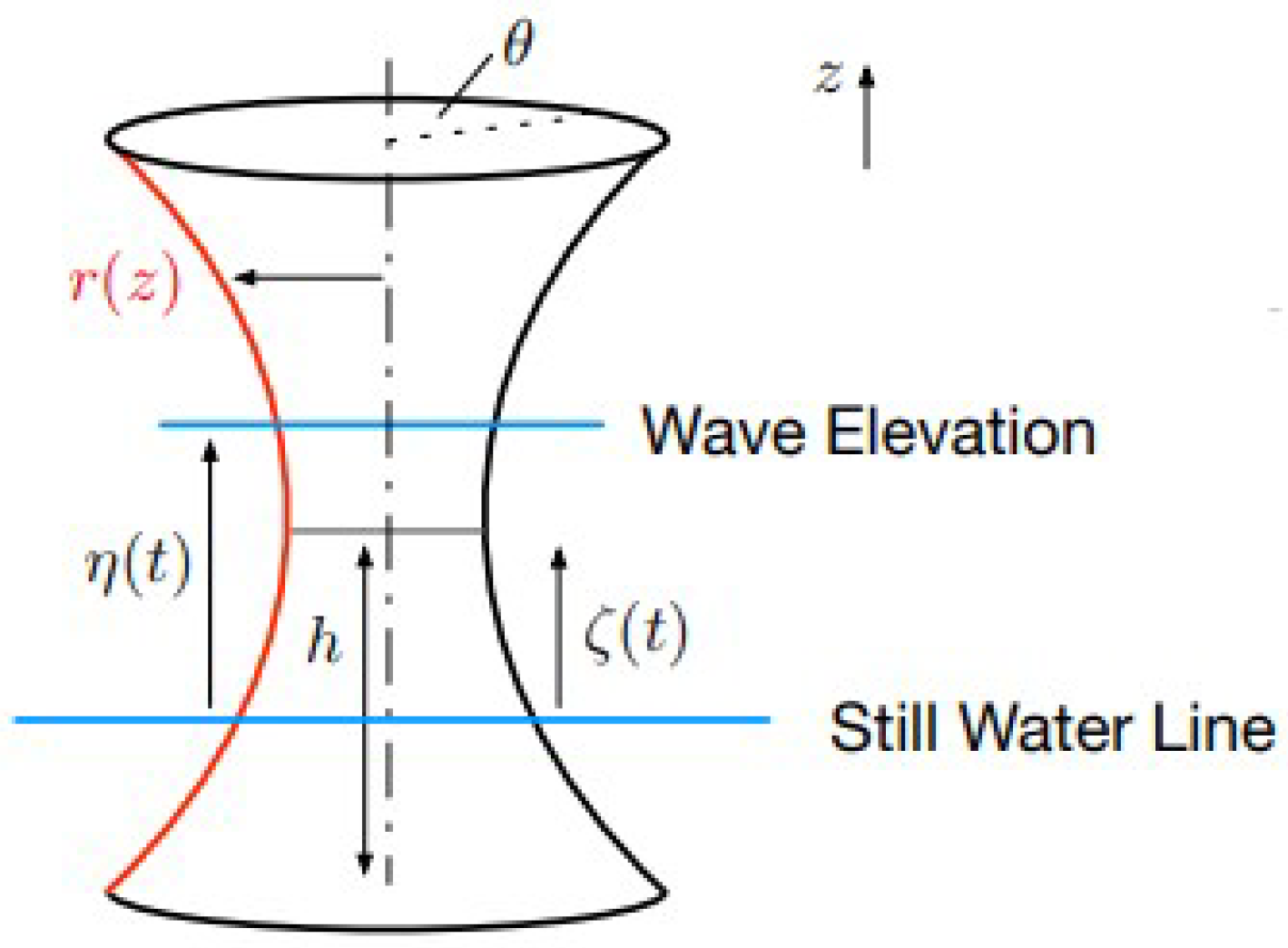

- A three-parameter buoy shape.

3.2. Pressure Integration and Buoy Shape Parameterization

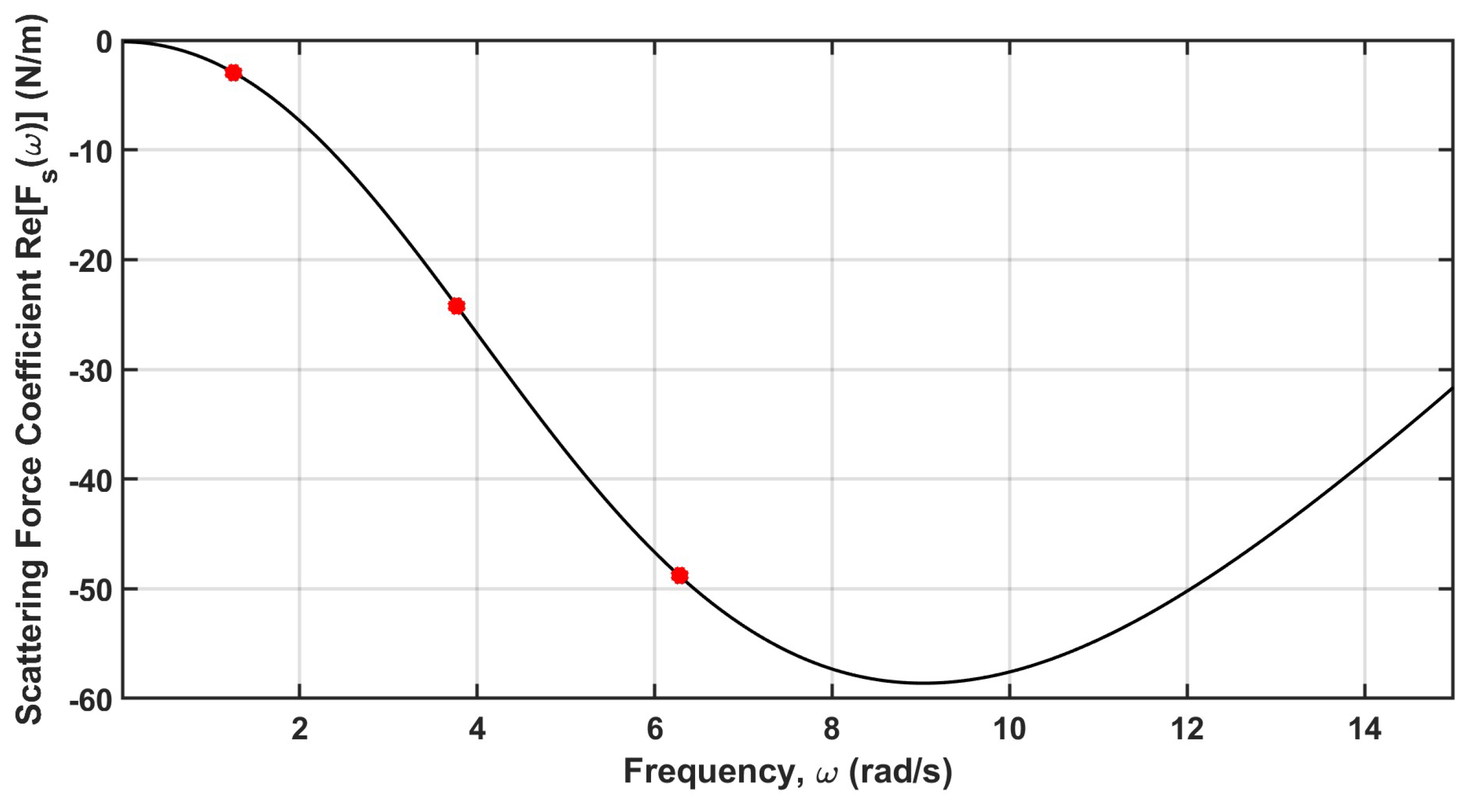

4. Derivation of

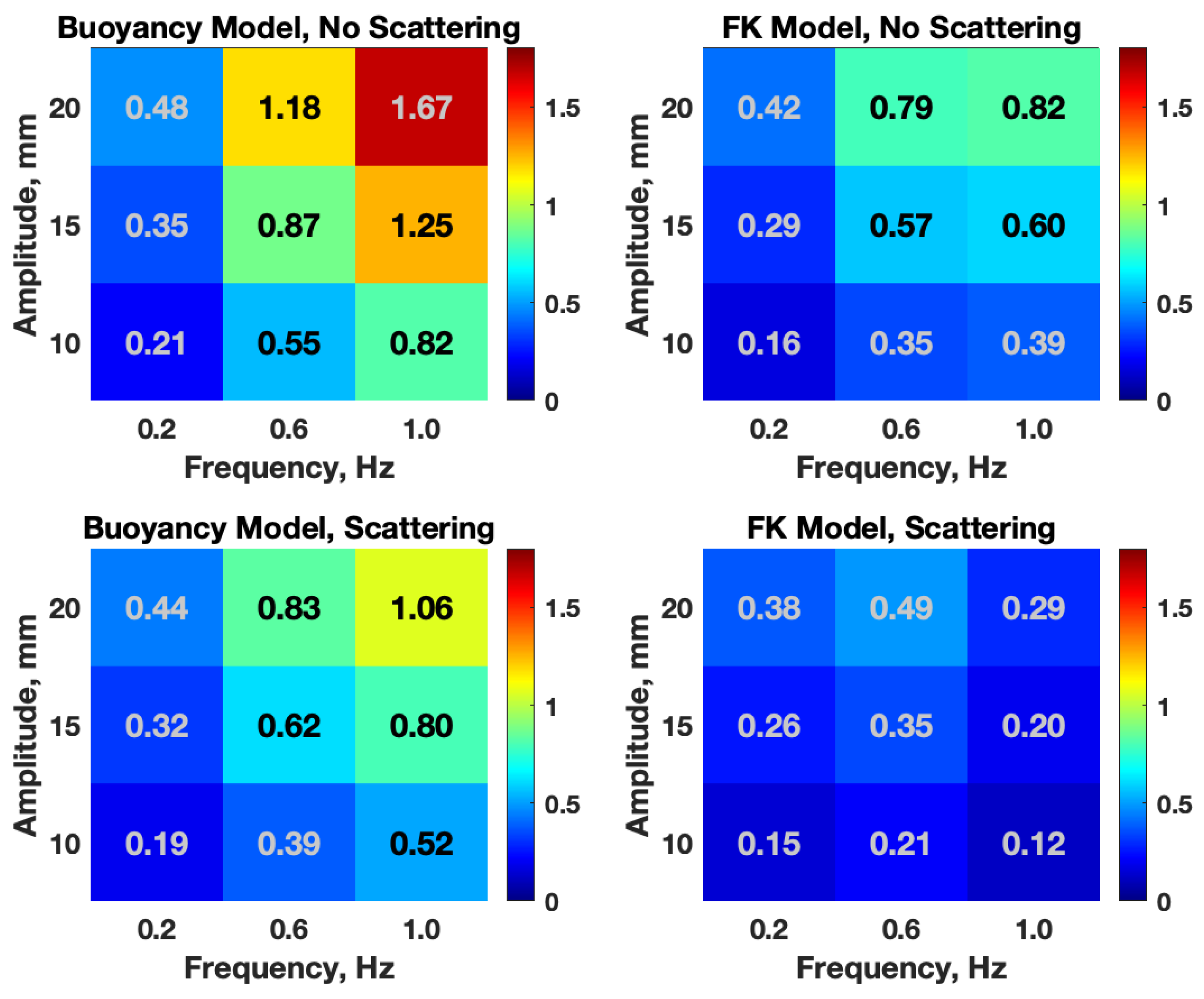

5. Model Form Comparison

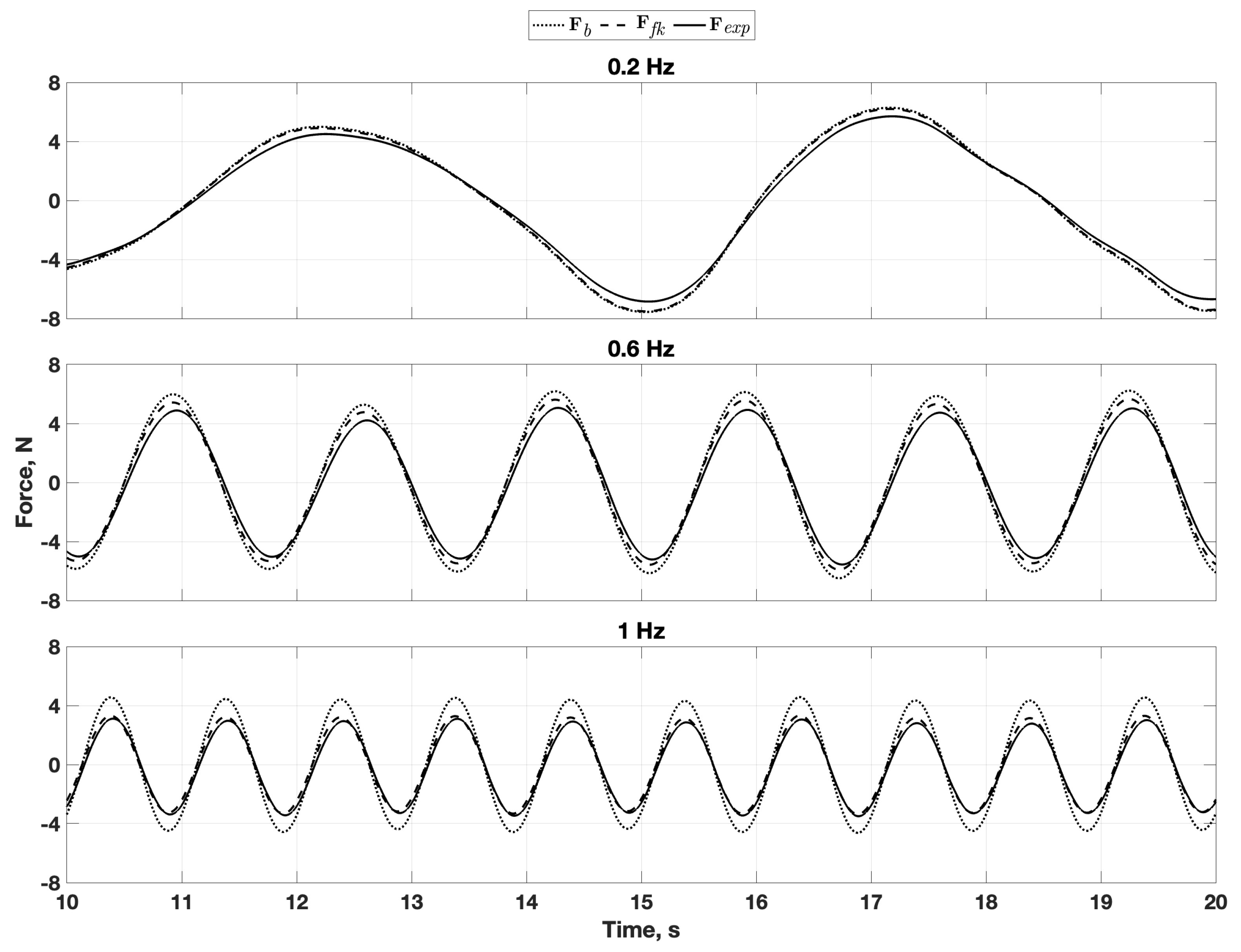

6. Experimental Validation

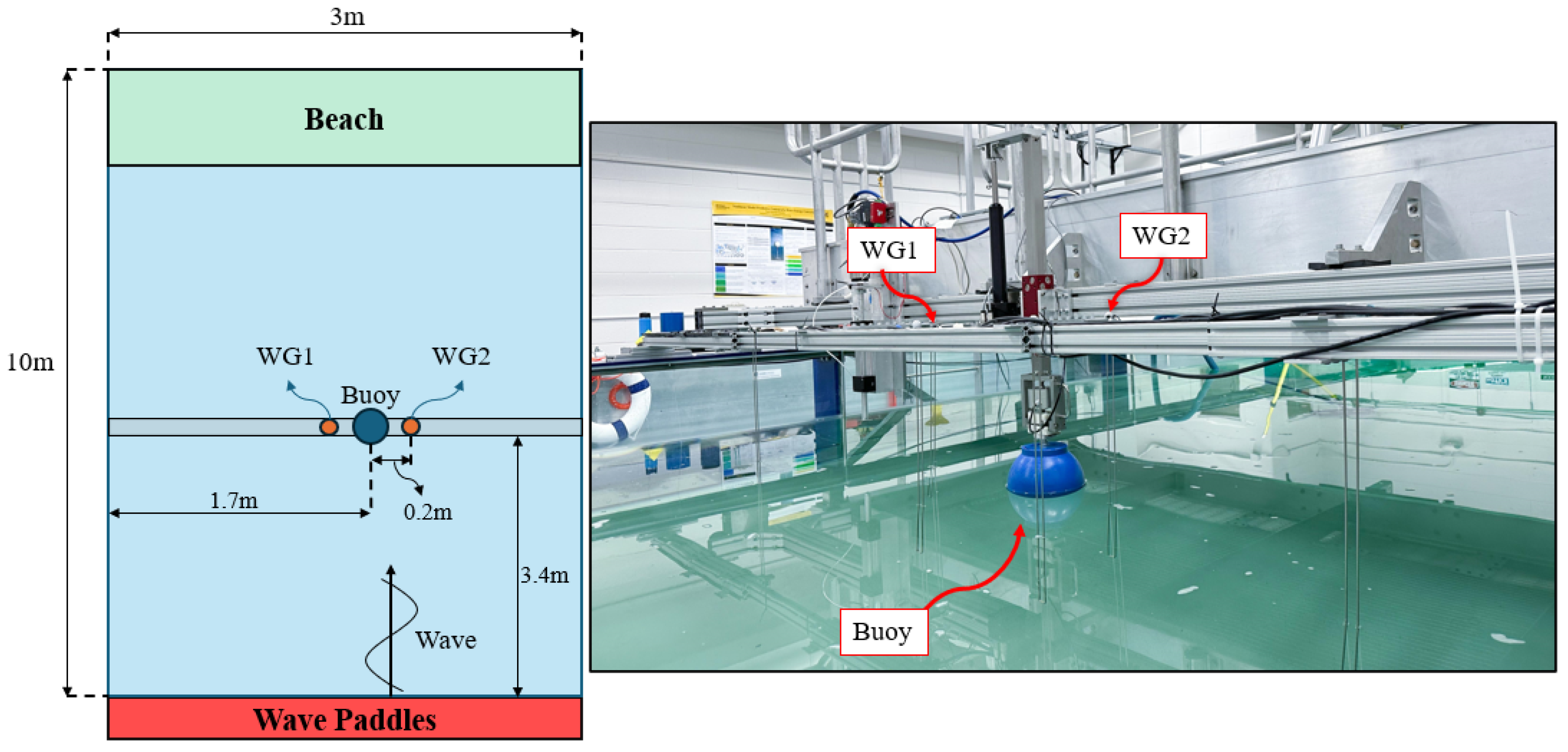

6.1. Experimental Setup

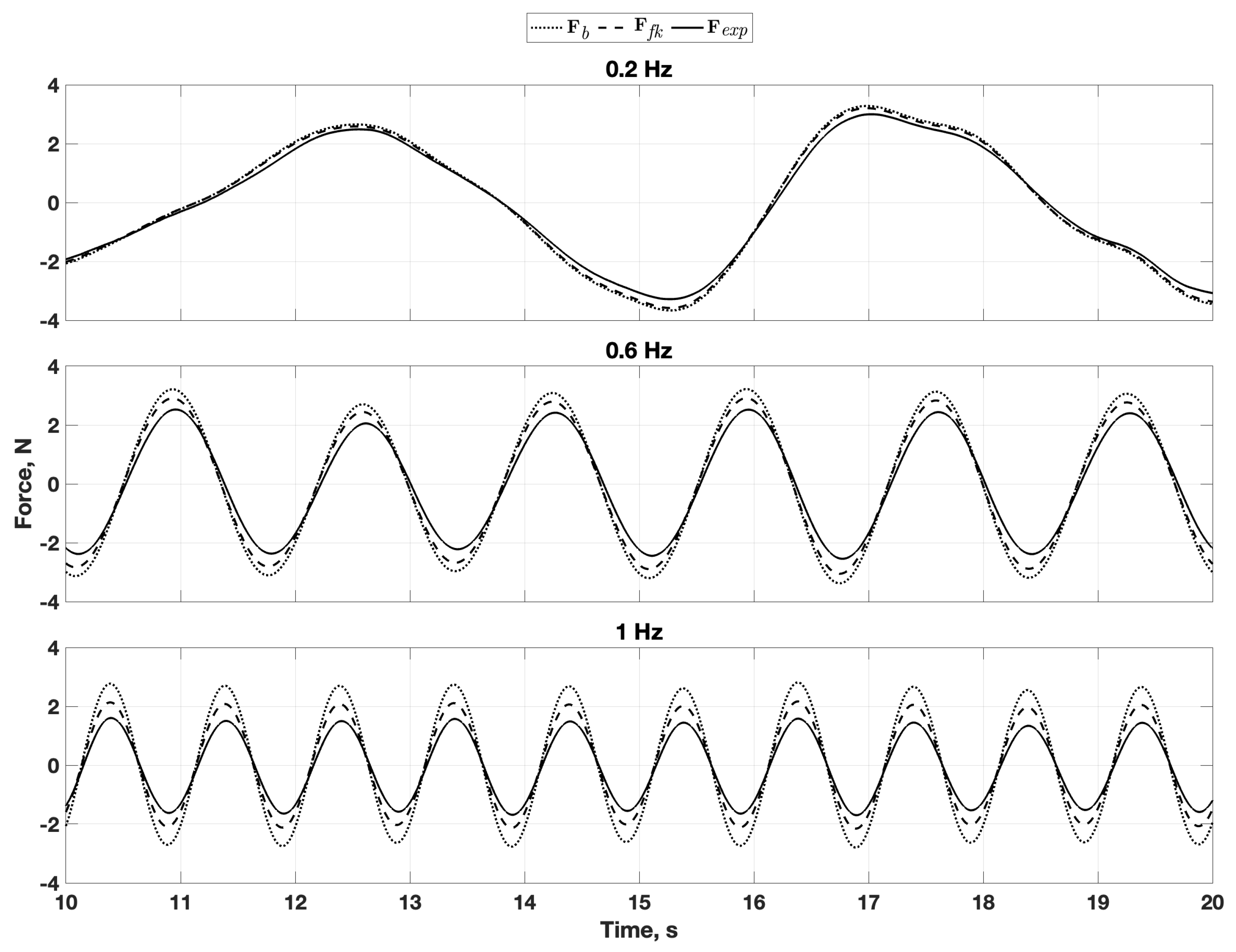

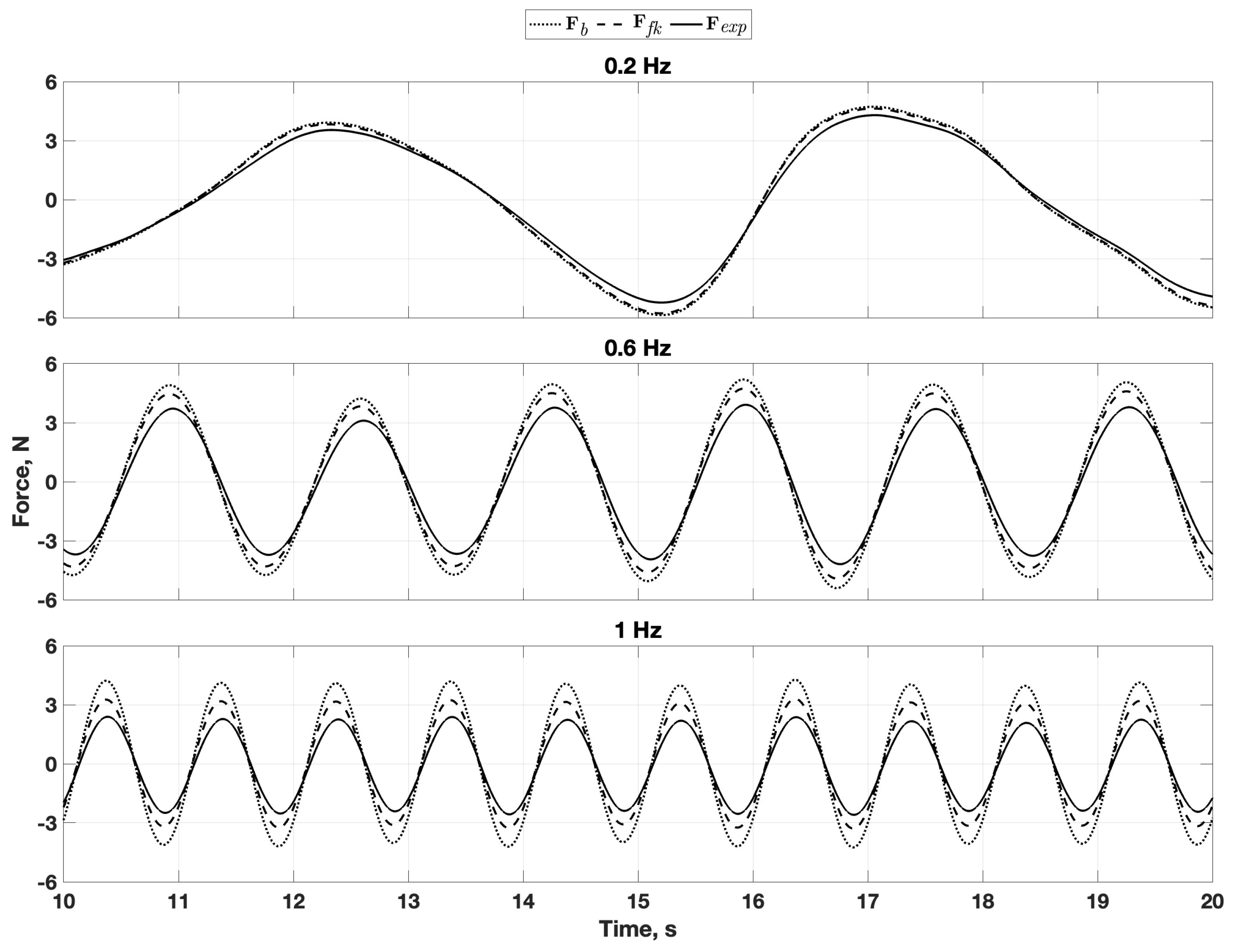

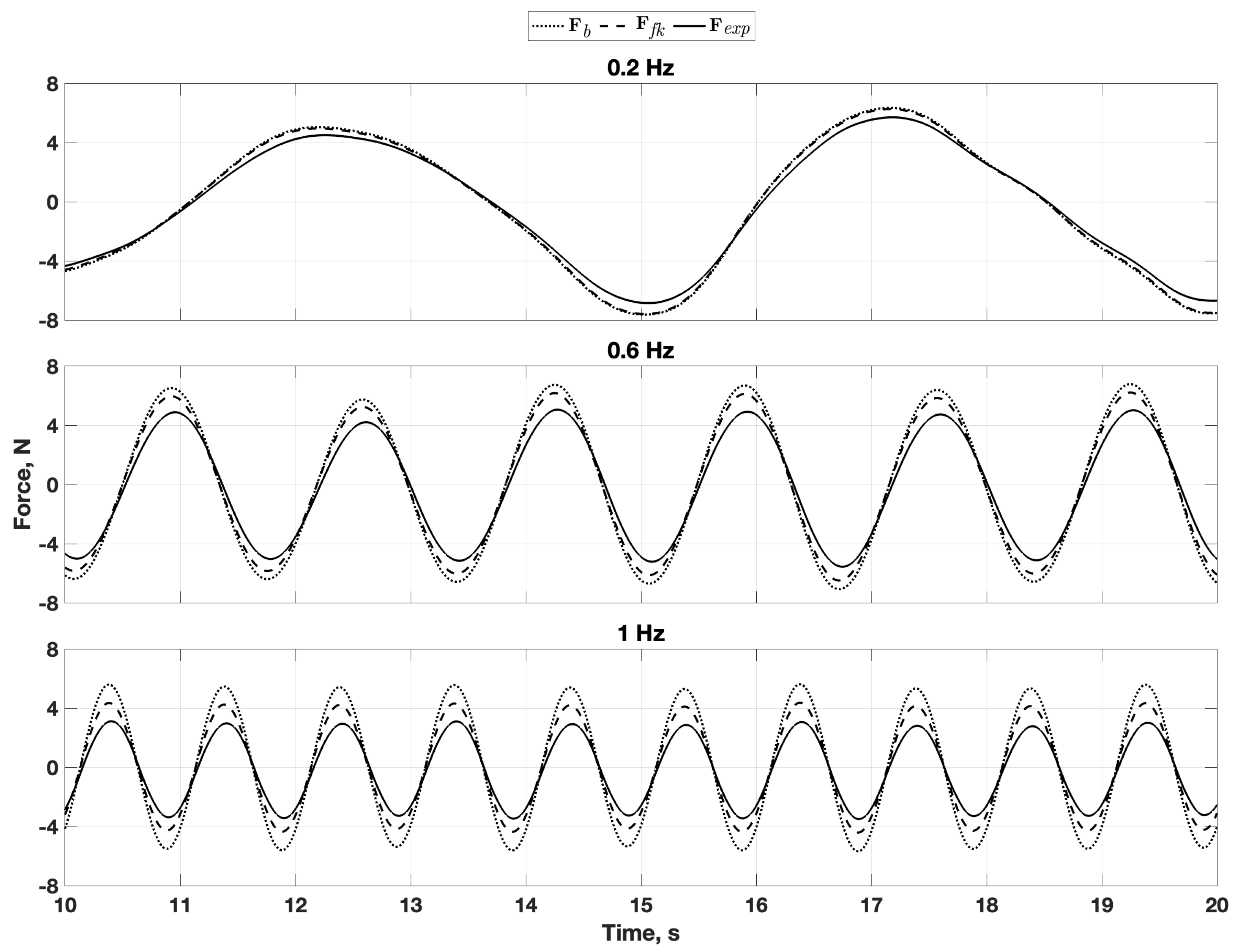

6.2. Data Comparison

7. Conclusion and Future Work

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

References

- Aderinto, T.; Li, H. Review on power performance and efficiency of wave energy converters. Energies 2019, 12, 4329.

- Guo, B.; Wang, T.; Jin, S.; Duan, S.; Yang, K.; Zhao, Y. A review of point absorber wave energy converters. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2022, 10, 1534.

- Faÿ, F.X.; Henriques, J.C.; Kelly, J.; Mueller, M.; Abusara, M.; Sheng, W.; Marcos, M. Comparative assessment of control strategies for the biradial turbine in the Mutriku OWC plant. Renewable Energy 2020, 146, 2766–2784.

- Budar, K.; Falnes, J. A resonant point absorber of ocean-wave power. Nature 1975, 256, 478–479.

- Falnes, J. A review of wave-energy extraction. Marine structures 2007, 20, 185–201.

- Falnes, J.; Kurniawan, A. Ocean waves and oscillating systems: linear interactions including wave-energy extraction; Vol. 8, Cambridge university press, 2020.

- Korde, U.A.; Ringwood, J. Hydrodynamic control of wave energy devices; Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Faedo, N.; Pasta, E.; Carapellese, F.; Orlando, V.; Pizzirusso, D.; Basile, D.; Sirigu, S.A. Energy-maximising experimental control synthesis via impedance-matching for a multi degree-of-freedom wave energy converter. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 345–350.

- Lattanzio, S.; Scruggs, J. Maximum power generation of a wave energy converter in a stochastic environment. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE international conference on control applications (CCA). IEEE, 2011, pp. 1125–1130.

- Bacelli, G.; Nevarez, V.; Coe, R.G.; Wilson, D.G. Feedback resonating control for a wave energy converter. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2019, 56, 1862–1868.

- Yassin, H.; Demonte Gonzalez, T.; Nelson, K.; Parker, G.; Weaver, W. Optimal Control of Nonlinear, Nonautonomous, Energy Harvesting Systems Applied to Point Absorber Wave Energy Converters. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2024, 12, 2078.

- Zou, S.; Abdelkhalik, O.; Robinett, R.; Bacelli, G.; Wilson, D. Optimal control of wave energy converters. Renewable energy 2017, 103, 217–225.

- Abdelkhalik, O.; Darani, S. Optimization of nonlinear wave energy converters. Ocean Engineering 2018, 162, 187–195.

- Li, G.; Belmont, M.R. Model predictive control of sea wave energy converters–Part I: A convex approach for the case of a single device. Renewable Energy 2014, 69, 453–463.

- Brekken, T.K. On model predictive control for a point absorber wave energy converter. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Trondheim PowerTech. IEEE, 2011, pp. 1–8.

- Zou, S.; Abdelkhalik, O.; Robinett, R.; Korde, U.; Bacelli, G.; Wilson, D.; Coe, R. Model Predictive Control of parametric excited pitch-surge modes in wave energy converters. International journal of marine energy 2017, 19, 32–46.

- Demonte Gonzalez, T.; Anderlini, E.; Yassin, H.; Parker, G. Nonlinear Model Predictive Control of Heaving Wave Energy Converter with Nonlinear Froude–Krylov Forces. Energies 2024, 17, 5112.

- Wilson, D.G.; Robinett III, R.D.; Bacelli, G.; Abdelkhalik, O.; Coe, R.G. Extending complex conjugate control to nonlinear wave energy converters. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2020, 8, 84.

- Richter, M.; Magana, M.E.; Sawodny, O.; Brekken, T.K. Nonlinear model predictive control of a point absorber wave energy converter. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2012, 4, 118–126.

- Darani, S.; Abdelkhalik, O.; Robinett, R.D.; Wilson, D. A hamiltonian surface-shaping approach for control system analysis and the design of nonlinear wave energy converters. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2019, 7, 48.

- Giorgi, G.; Ringwood, J.V. Implementation of latching control in a numerical wave tank with regular waves. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Marine Energy 2016, 2, 211–226.

- Giorgi, G.; Ringwood, J.V. Nonlinear Froude-Krylov and viscous drag representations for wave energy converters in the computation/fidelity continuum. Ocean Engineering 2017, 141, 164–175.

- Faltinsen, O. Sea loads on ships and offshore structures; Vol. 1, Cambridge university press, 1993.

- Giorgi, G.; Ringwood, J.V. Computationally efficient nonlinear Froude–Krylov force calculations for heaving axisymmetric wave energy point absorbers. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Marine Energy 2017, 3, 21–33.

- Giorgi, G.; Ringwood, J.V. A Compact 6-DoF Nonlinear Wave Energy Device Model for Power Assessment and Control Investigations. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2019, 10, 119–126. [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Sirigu, S.; Bonfanti, M.; Bracco, G.; Mattiazzo, G. Fast nonlinear Froude–Krylov force calculation for prismatic floating platforms: a wave energy conversion application case. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Marine Energy 2021, 7, 439–457.

- Demonte Gonzalez, T.; Parker, G.G.; Anderlini, E.; Weaver, W.W. Sliding mode control of a nonlinear wave energy converter model. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2021, 9, 951.

- Yassin, H.; Demonte Gonzalez, T.; Parker, G.; Wilson, D. Effect of the Dynamic Froude–Krylov Force on Energy Extraction from a Point Absorber Wave Energy Converter with an Hourglass-Shaped Buoy. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 4316.

- Penalba, M.; Giorgi, G.; Ringwood, J.V. Mathematical modelling of wave energy converters: A review of nonlinear approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 78, 1188–1207. [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Ringwood, J.V. Comparing nonlinear hydrodynamic forces in heaving point absorbers and oscillating wave surge converters. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Marine Energy 2018, 4, 25–35.

- WAMIT, Inc. The State of the Art in Wave Interaction Analysis, 2023.

- Korde, U.A.; Ringwood, J. Hydrodynamic Control of Wave Energy Devices; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.N. Marine Hydrodynamics; The MIT Press, 1977. [CrossRef]

- Dingemans, M.W. Water wave propagation over uneven bottoms: Linear wave propagation; Vol. 13, World Scientific, 2000.

| Shape | R | h | |

| Spheroid, Oblate | Free | ||

| Sphere | Free | R | |

| Spheroid, Prolate | Free | ||

| Cylinder | 0 | Free | Free |

| Hyperboloid (Hourglass) | Free | Free | |

| Cone-Cone | 0 | Free |

|

| Frequency f, Hz | Amplitude A, mm | Number , 1/m | Length , m | Steepness |

| 0.2 | [10, 15, 20] | 0.4 | 15.2 | [0.0005, 0.0008, 0.001] |

| 0.6 | [10, 15, 20] | 1.6 | 4.0 | [0.005, 0.007, 0.009] |

| 1.0 | [10, 15, 20] | 4.0 | 1.6 | [0.013, 0.019, 0.026] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).