Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Evidence

2.2. Empirical Evidence

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Preparation

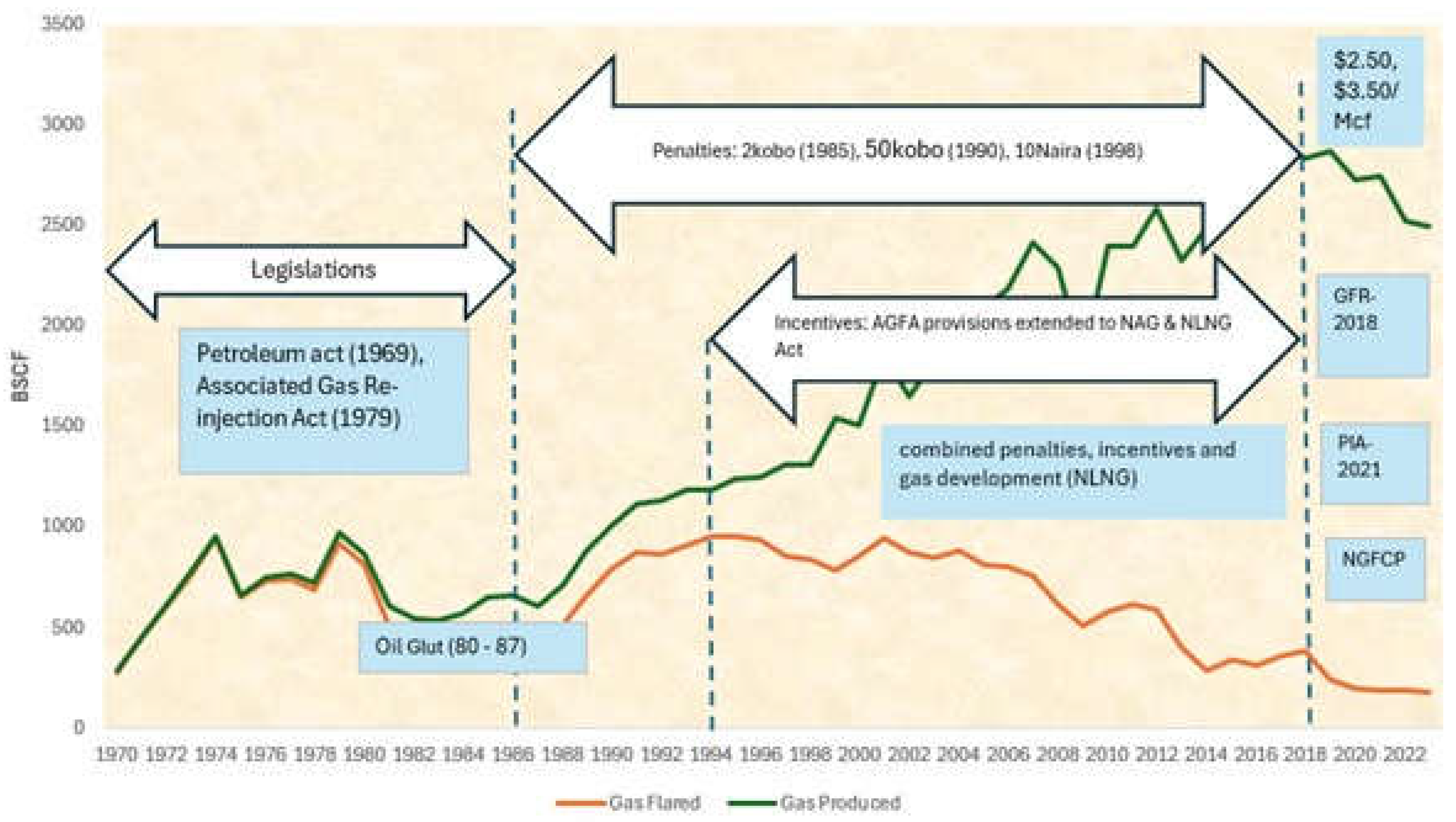

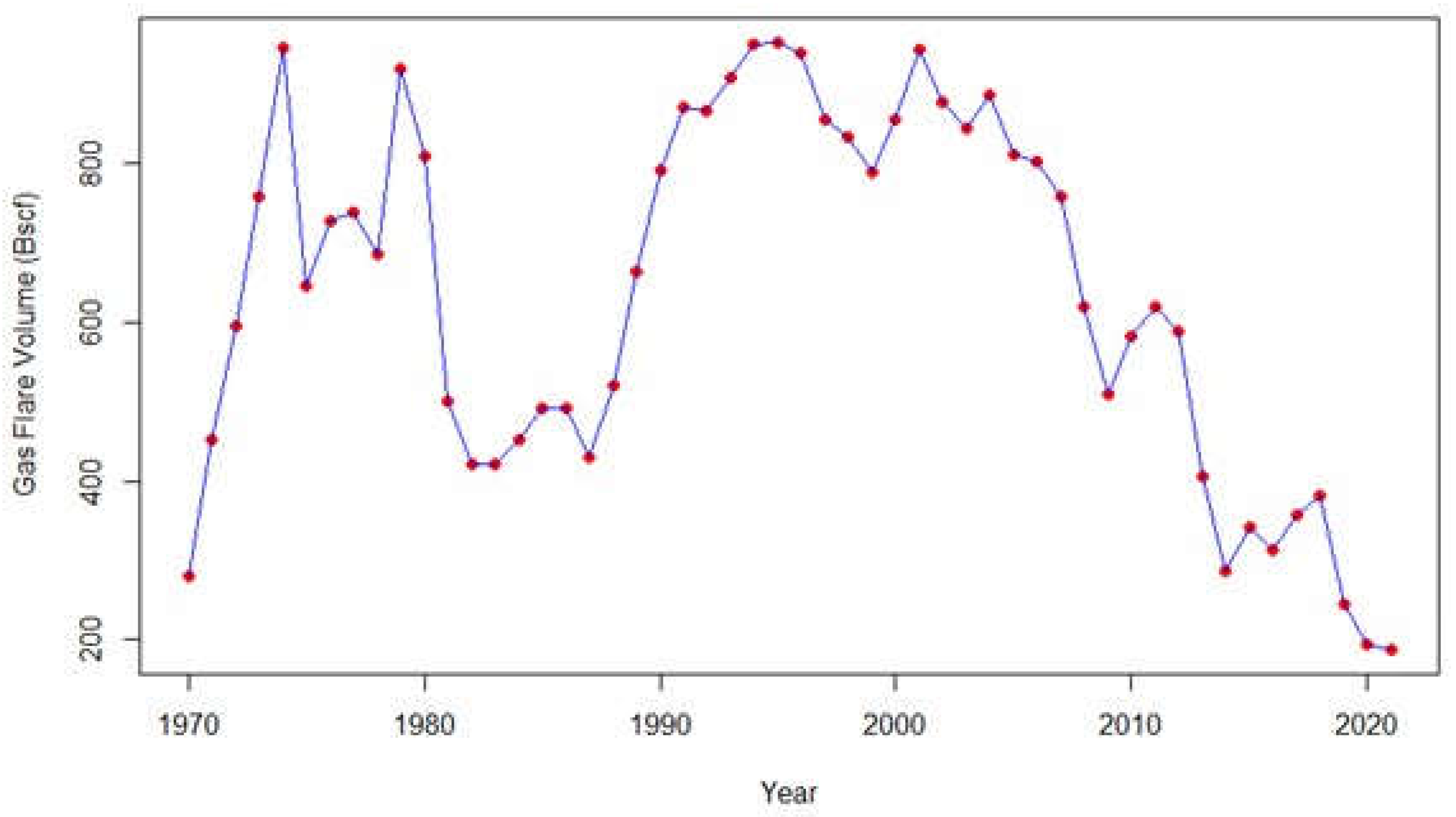

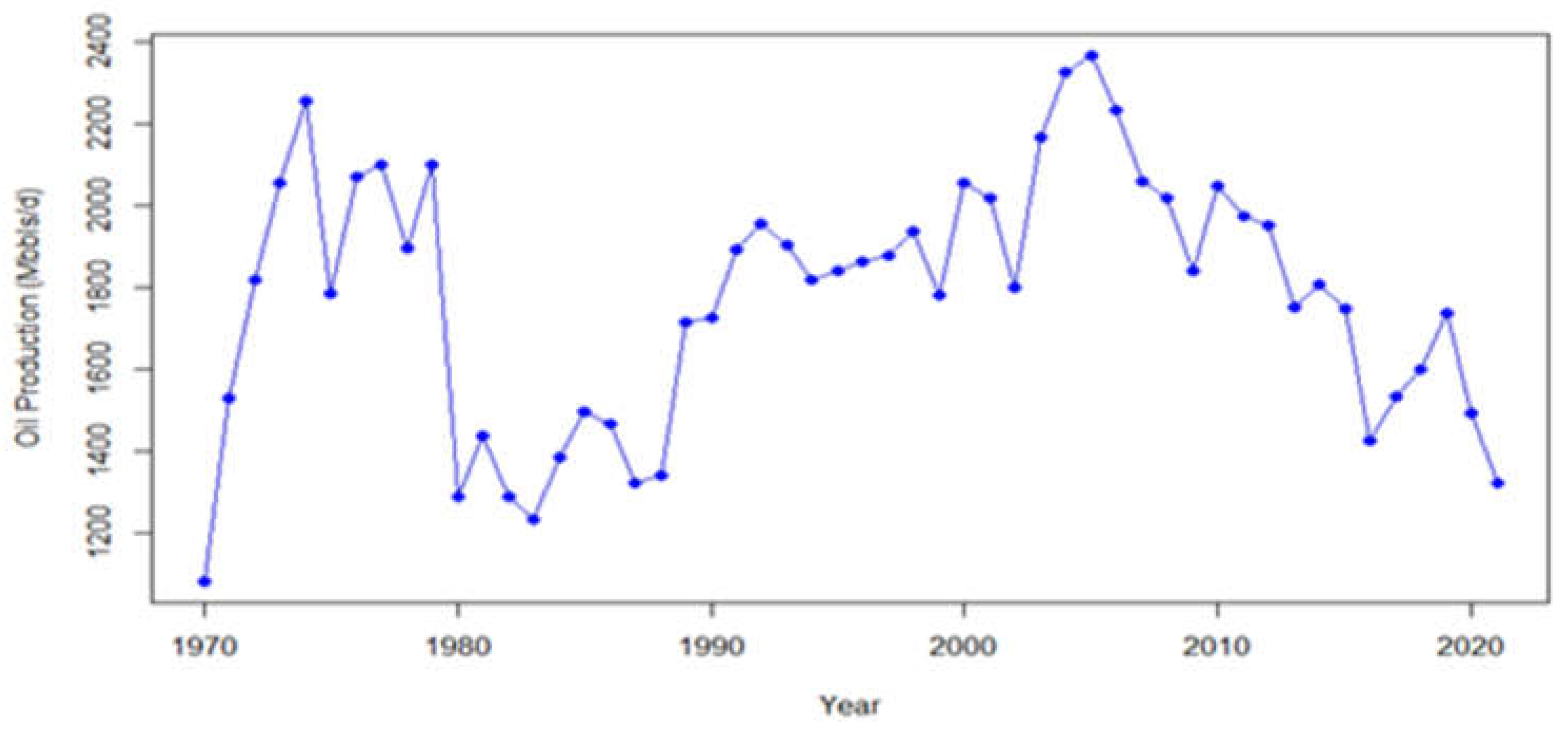

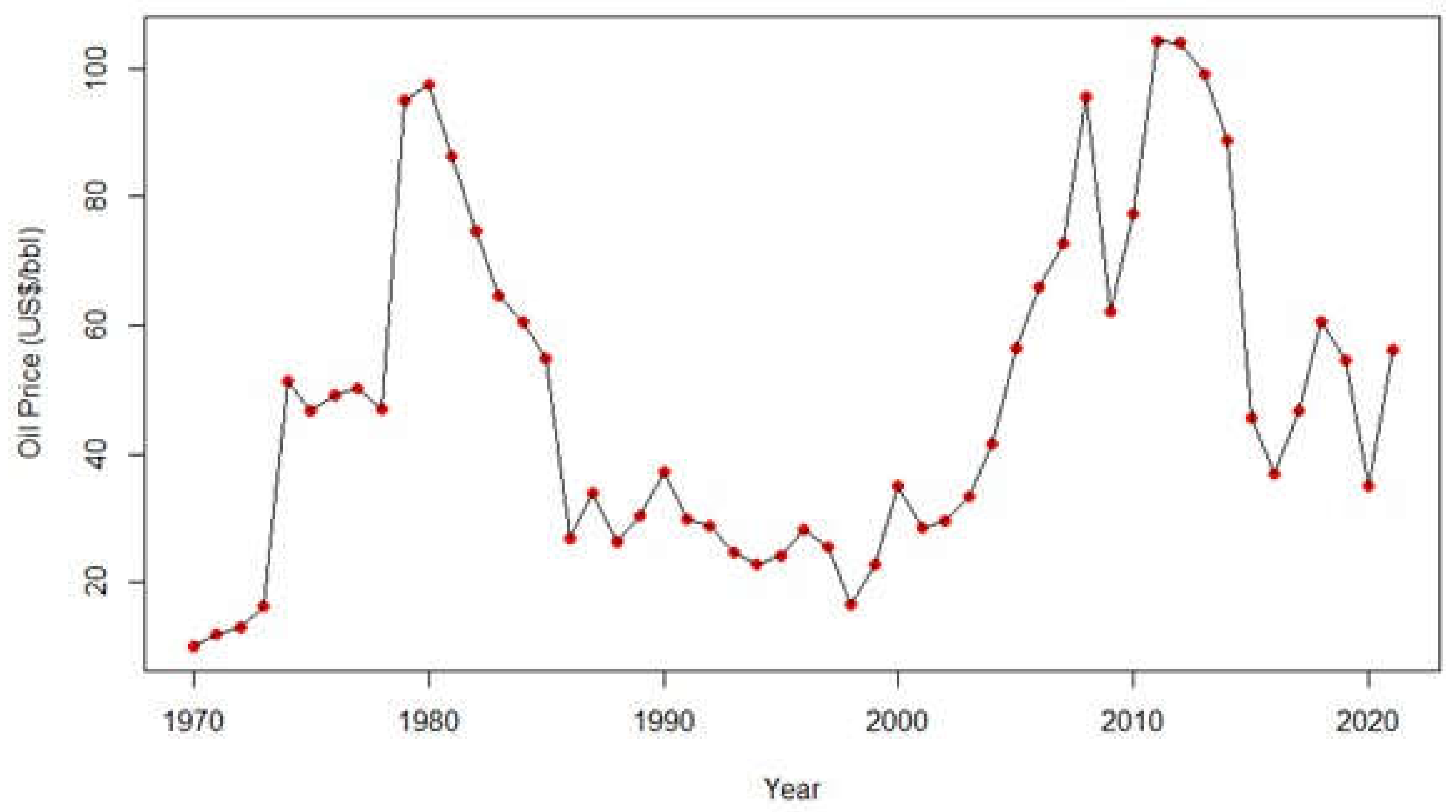

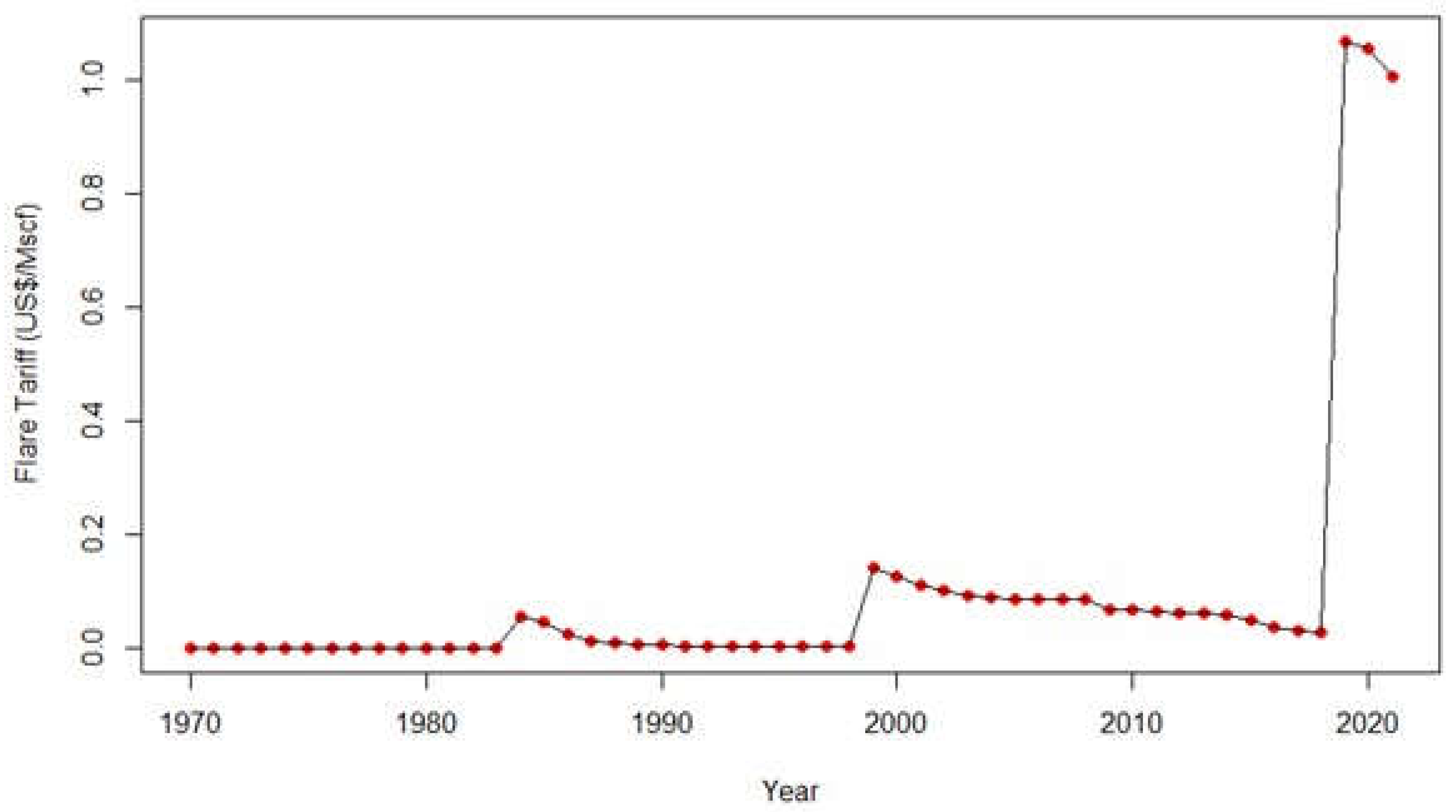

3.2. Data Visualization

3.3. Model Specification

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Summary statistics

4.2. Results of Level, Semi-Log and Log-Log Transforms

4.3. Results of the Tariff Regime Change

5. Conclusion/Policy Implication

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCM | Billion Cubic Metre |

| M3/BBl | Cubic Metre per Barrel |

| MSCF | Thousand Standard Cubic Feet |

| MNCs | Multi National Companies |

| NGFCP | Nigerian Gas Flare Commercialization Programme |

| PIA | Petroleum Industry Act |

| BSCF | Billion Standard Cubic Feet |

| AFT | Adjusted Flare Tariff |

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 27]. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- Okoye, LU.Adeleye, BN.Okoro, EE.Okoh, JI.Ezu, GK.Anyanwu, FA. Effect of gas flaring, oil rent and fossil fuel on economic performance: The case of Nigeria. Resources Policy [Internet]. 2022;77(December 2021):102677. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B. bakerhughes.com. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 13]. 5 things you should know about flaring. Available online: https://www.bakerhughes.com/company/energy-forward/5-things-you-should-know-about-flaring.

- Joshua, OI.Wisdom, PE.Queendarlyn, AN. Re-evaluating the problems of gas flaring in the Nigerian petroleum industry. World Sci News. 2020;147(June):76–87.

- Ejiogu, A. Gas flaring in nigeria: Costs and policy. Energy and Environment [Internet]. 2013;24(6):983–98. [CrossRef]

- Nwanya, SC. Climate change and energy implications of gas flaring for Nigeria. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies. 2011;6(3):193–9. [CrossRef]

- Anejionu, OCD.Whyatt, JD.Blackburn, GA.Price, CS. Contributions of gas flaring to a global air pollution hotspot: Spatial and temporal variations, impacts and alleviation. Atmos Environ [Internet]. 2015;118:184–93. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, OS.Umukoro, GE. Global impact of gas flaring. Energy Power Eng. 2012;04(04):290–302.

- Ajugwo, a. O. Negative effects of gas flaring: The Nigerian experience. Journal of Environment Pollution and Human Health [Internet]. 2013;1(1):6–8. Available online: http://pubs.sciepub.com/jephh/1/1/2/index.html.

- Ubani, E.Onyejekwe, I. Environmental impact analyses of gas flaring in the Niger delta region of Nigeria. American Journal of Scientific and Industrial Research. 2013;4(2):246–52.

- Edino, MO.Nsofor, GN.Bombom, LS. Perceptions and attitudes towards gas flaring in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Environmentalist. 2010;30(1):67–75. [CrossRef]

- Teye, ET.Rufai, OH.Alademomi, RO.Ashu, HA.Said, F hiya A.Oludu, VO.et al. A mixed method inquiry of gas flaring consequences, mitigation strategies and policy implication for environmental sustainability in Nigeria. Journal of Environment and Earth Science. 2019;46–58. [CrossRef]

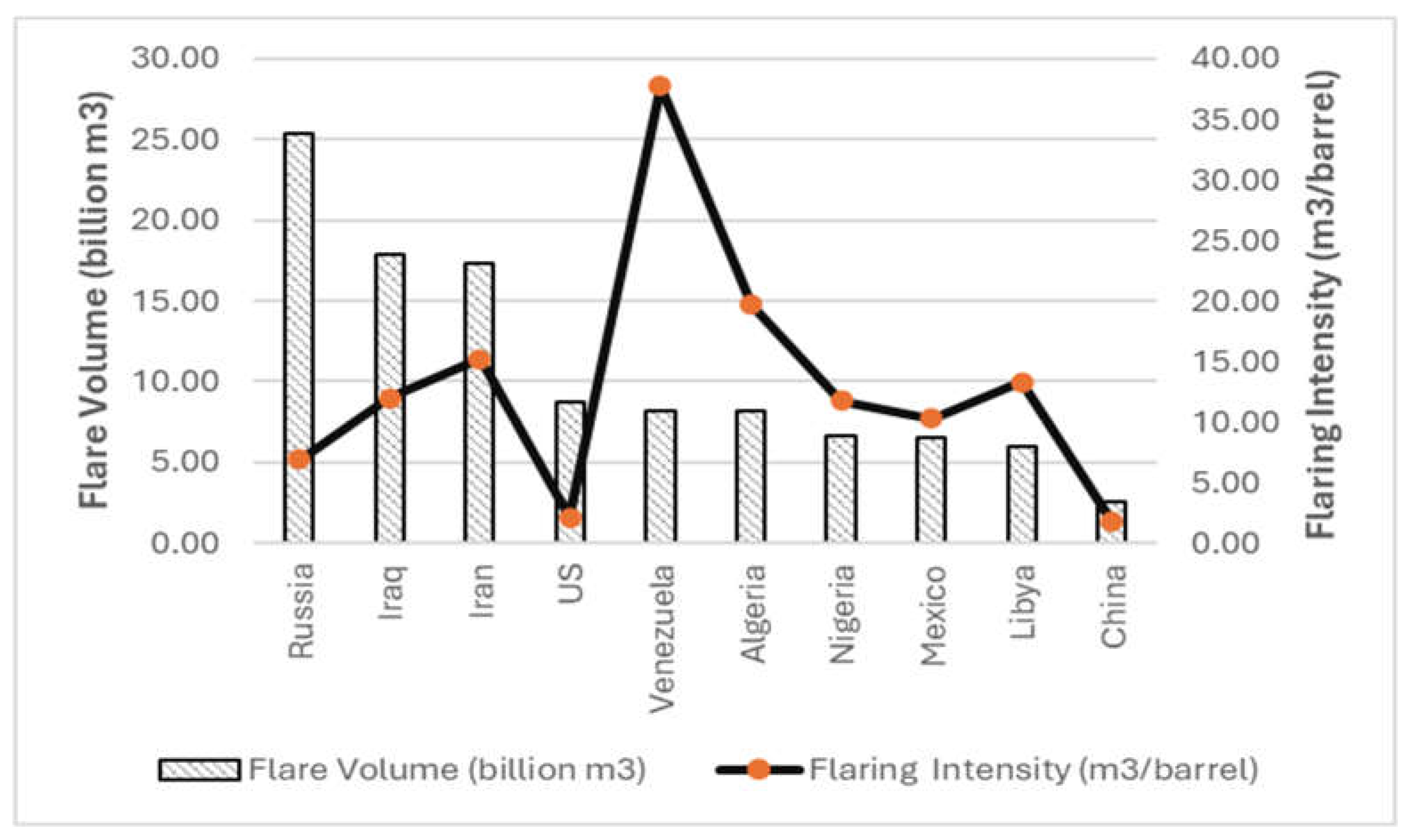

- GGFR. 2022 Global Gas Flaring Tracker Report. Https://Thedocs.Worldbank.Org. 2022.

- World Bank. Global Gas Flaring Tracker Report [Internet]. 2024 Jun. Available online: www.worldbank.org.

- World Bank. Global Gas Flaring Tracker Report [Internet]. 2023 Mar. Available online: www.worldbank.org.

- Rodrigues, ACC. Decreasing natural gas flaring in Brazilian oil and gas industry. Resources Policy. 2022;77(December 2021):102776.

- Hagos, FY.Abd Aziz, AR.Zainal, EZ.Mofijur, M.Ahmed, SF. Recovery of gas waste from the petroleum industry: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2022;20(1):263–81. [CrossRef]

- Agerton, M.Gilbert, B.Upton, G. The Economics of Natural Gas Flaring: An Agenda for Research and Policy. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020.

- Teye, ET.Rufai, OH.Alademomi, RO.Ashu, HA.Said, F hiya A.Oludu, VO.et al. A mixed method inquiry of gas flaring consequences, mitigation strategies and policy implication for environmental sustainability in Nigeria. Journal of Environment and Earth Science. 2019;46–58. [CrossRef]

- Madueme, S. Gas Flaring activities of major oil companies in Nigeria: An economic investigation. International Journal of Engineering Science and Technology. 2010;2(4):610–7.

- E. Ite, A.J. Ibok, U. Gas flaring and venting associated with petroleum exploration and production in the Nigeria’s Niger Delta. American Journal of Environmental Protection. 2013;1(4):70–7. [CrossRef]

- Orji, UJ. Moving from gas flaring to gas conservation and utilisation in Nigeria: a review of the legal and policy regime. OPEC Energy Review. 2014;38(2):149–83. [CrossRef]

- Udok, U.Enobong, &.Akpan, B. Gas flaring in Nigeria: Problems and prospects. Global Journal of Politics and Law Research. 2017;5(1):16–28.

- Aregbe, AG. Natural gas flaring—Alternative solutions. World Journal of Engineering and Technology. 2017;05(01):139–53. [CrossRef]

- Thurber, M. Gas Flaring : Why does it happen and what can stop it ? 2019. p. 7–9.

- Diugwu, IA.Mohammed, M.Egila, AE.Ijaiya, MA. The effect of gas production, utilization, and flaring on the economic growth of Nigeria. Natural Resources. 2013;04(04):341–8. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A. Dealing with vulnerability to carbon emission from gas flaring: the roles of transparency and utilisation policies in Nigeria. OPEC Energy Review. 2020;44(4):369–403. [CrossRef]

- Okoro, EE.Adeleye, BN.Okoye, LU.Maxwell, O. Gas flaring, ineffective utilization of energy resource and associated economic impact in Nigeria: Evidence from ARDL and Bayer-Hanck cointegration techniques. Energy Policy. 2021;153(March):112260. [CrossRef]

- Hydrocarbon Processing. Aggreko completes Middle East’s largest flare gas to power project. 2022 Jan 24 [cited 2025 Jan 30]. Available online: https://www.hydrocarbonprocessing.com/news/2022/01/aggreko-completes-middle-east-s-largest-flare-gas-to-power-project.

- Hoerbiger. Hoerbiger’s Sacha Central Project [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 30]. Available online: https://issuu.com/world.bank.publications/docs/9781464818509/s/15716421.

- NUPRC. About NGFCP [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 30]. Available online: https://ngfcp.nuprc.gov.ng/about-ngfcp/.

- World Bank. Global flaring and venting regulations [Internet]. 2023 Dec [cited 2024 Dec 9]. Available online: https://flaringventingregulations.worldbank.org/nigeria.

- Abu, R.Patchigolla, K.Simms, N. A Review on qualitative assessment of natural gas utilisation options for eliminating routine Nigerian gas flaring. Gases. 2023;3(1):1–24. [CrossRef]

- Ejiogu, AR. Gas flaring in Nigeria: Costs and policy. Sage Publications. 2018;24(6):983–98. [CrossRef]

- Department of Petroleum Resources. Nigerian Gas Flare Commercialization Programme (NGFCP): Key to Nigeria flare-out agenda Nigeria. In: DPR & Press Stakeholders retreat. Lagos; 2018.

- NUPRC. Gas flaring, venting and methane emissions (Prevention of Waste and Pollution) Regulations, 2023 [Internet]. Vol. 110. Lagos: The Federal Government Printer; 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 29]. Available online: https://www.nuprc.gov.ng/gazetted-regulations/.

- Gerner, F.Svensson, B.Djumena, S. Gas Flaring and Venting: A regulatory framework and incentives for gas utilization. The World Bank Group (Public Policy Journal). 2004;(279):4.

- Aghalino, SO. Gas flaring, environmental pollution and abatement measures in Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa. 2009;11(4):219–38.

- Olujobi, OJ.Olusola-Olujobi, T. Comparative appraisals of legal and institutional framework governing gas flaring in Nigeria’s upstream petroleum sector: How satisfactory? Environmental Quality Management. 2020;1–14.

- Akinola, AO. Resource misgovernance and the contradictions of gas flaring in Nigeria: A theoretical conversation. J Asian Afr Stud. 2018;53(5):749–63. [CrossRef]

- Adekomaya, O.Jamiru, T.Sadiku, R.Huan, Z.Sulaiman, M. Gas flaring and its impact on electricity generation in Nigeria. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2016;29:1–6. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, N. National energy policy and gas flaring in Nigeria. Journal of Environment and Earth Science. 2015;5(14):58–65.

- Dike, SC.Odimabo-nsijilem. Evaluating the gas flaring commercialisation policy in Nigeria: An agenda for mitigating gas flaring. Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization. 2020;96(2224–3259):130–40.

- Olujobi, OJ.Yebisi, TE.Patrick, OP.Ariremako, AI. The legal framework for combating gas flaring in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry: Can it promote sustainable energy security? Sustainability (Switzerland). 2022;14(13). [CrossRef]

- Okoye, LU.Adeleye, BN.Okoro, EE.Okoh, JI.Ezu, GK.Anyanwu, FA. Effect of gas flaring, oil rent and fossil fuel on economic performance: The case of Nigeria. Resources Policy. 2022;77(December 2021):102677.

- Hassan, A.Kouhy, R. Gas flaring in Nigeria: Analysis of changes in its consequent carbon emission and reporting. Accounting Forum. 2013;37(2):124–34. [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. World Development Indicators [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 6]. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/home.aspx.

- Korieh, CJ. The nigeria-biafra war, oil and the political economy of state induced development strategy in eastern nigeria, 1967–1995. Social Evolution and History. 2018 Mar 1;17(1):76–107.

- Smith, WE. The light that failed: Nigeria. Time Magazine [Internet]. 1984 Jan 16 [cited 2024 Dec 11]. Available online: https://time.com/archive/6855357/the-light-that-failed-nigeria/.

- The Washington Post. Oil, Coups and Nigeria. 1985 Aug 28 [cited 2024 Dec 11]. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1985/08/29/oil-coups-and-nigeria/c373f952-131e-4871-a6d0-a38d56b31654/.

- NLNG. Who we are [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 13]. Available online: https://www.nigerialng.com/the-company/Pages/Who-We-Are.aspx.

- Punch. Obasanjo’s $8bn power plants helping Nigeria. 2024 Feb 21.

- EIA. Crude oil prices peaked early in 2012 [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=7630.

- Okoro, EE.Adeleye, BN.Okoye, LU.Maxwell, O. Gas flaring, ineffective utilization of energy resource and associated economic impact in Nigeria: Evidence from ARDL and Bayer-Hanck cointegration techniques. Energy Policy [Internet]. 2021;153(March):112260. [CrossRef]

- Mu, X. Have the Chinese national oil companies paid too much in overseas asset acquisitions? International Review of Financial Analysis [Internet]. 2024;92(September 2023):103074. [CrossRef]

- Derefaka, J. Nigerian Gas Flare Commercialization Programme: Roadmap to end routine gas flaring by 2020. In: Nigerian International Petroleum Summit. Abuja; 2019.

- Yunusa, N.Idris, IT.Zango, AG.Kibiya, MU. Gas flaring effects and revenue made from crude oil in Nigeria. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy. 2016;6(3):617–20.

- Lade, GE.Rudik, I. Costs of inefficient regulation: Evidence from the Bakken. J Environ Econ Manage. 2020;102.

- Derefaka, J. Nigerian Gas Flare Commercialization Programme: Roadmap to end routine gas flaring by 2020. In: Nigerian International Petroleum Summit. Abuja; 2019.

| Total Gas flared (Bscf) | Total Oil produced (Mbbls/d) | Oil Price (US$/bbl) | Gas price (US$/Mscf) | Adjusted flare tariff (US$/Mscf) | |

| Statistics | TGF | TOP | OPR | GPR | AFT |

| Mean | 637.199 | 1780.385 | 48.773 | 8.152 | 0.217 |

| Median | 655.385 | 1819.350 | 46.095 | 6.830 | 0.005 |

| Maximum | 953.000 | 2366.000 | 104.210 | 16.900 | 3.417 |

| Minimum | 187.820 | 1084.500 | 10.120 | 2.650 | 0.000 |

| Kurtosis | -1.170 | -0.628 | -0.540 | 0.640 | 12.951 |

| Skewness | -0.300 | -0.295 | 0.656 | 1.193 | 3.739 |

| Range | 765.180 | 1281.500 | 94.090 | 14.250 | 3.417 |

| Std. Dev | 231.011 | 307.093 | 26.346 | 3.681 | 0.772 |

| Obs | 52 | 52 | 52 | 33 | 52 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Variables | Level form model | Semi-log model | Log-log model |

| Oil produced | 0.636*** | 0.001*** | 1.767*** |

| (0.089) | (0.000) | (0.252) | |

| Oil price | -4.856*** | -0.008*** | -0.350*** |

| (0.815) | (0.001) | (0.079) | |

| Gas price | -5.335 | -0.000 | 0.311*** |

| (12.841) | (0.023) | (0.094) | |

| Flare tariff | -277.324*** | -0.783*** | -0.115*** |

| (72.531) | (0.133) | 0.022 | |

| Constant | -224.160 | 4.886 | -6.366*** |

| (146.416) | (0.268) | (1.829) | |

| Observations | 52 | 52 | 52 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.779 | 0.80 | 0.83 |

| p-value of F-stat. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Variables | Level form model | Semi-log model | Log-log model |

| Oil produced | 0.642*** | 4.281*** | 1.837*** |

| (0.083) | (0.280) | (0.242) | |

| Oil price | -4.188*** | -0.006*** | -0.376*** |

| (0.820) | (0.000) | (0.076) | |

| Gas price | 2.033 | 0.020 | 0.199*** |

| (13.361) | (0.026) | (0.104) | |

| Pre2019AFT | -35.843*** | -0.089*** | -0.078*** |

| (15.101) | (0.029) | (0.027) | |

| Post2019AFT | -3223.327*** | -7.969*** | -6.918*** |

| 1799.598 | 3.467 | 3.299 | |

| Constant | -446.063*** | 4.281*** | -6.495*** |

| (145.229) | (0.280) | (1.744) | |

| Observations | 52 | 52 | 52 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.814 | 0.813 | 0.848 |

| P-value | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).