1. Introduction

Since the 1950s, the waterfront areas of Rabat-Salé have been the subject of extensive planning initiatives [1,3]. Notably, the land use plans devised by Ecochard in 1955 and by the Centre d’expérimentation, de recherche et de formation (CERF) between 1970 and 1976 designated these zones as non aedificandi (for the corniche) or as areas requiring sector-specific land use plans [3]. Subsequent efforts to develop the area with an emphasis on tourism also emerged [1,2]; however, these initiatives were largely unsuccessful. This failure can be attributed to a combination of institutional blockages, legal constraints in planning and land management [4], and the complex institutional arrangements surrounding land ownership [3]. These unsuccessful attempts occurred during the period between Morocco’s independence in 1956 and the end of King Hassan II’s reign in 1999.

In the early 2000s, under the leadership of King Mohammed VI, a series of significant initiatives were launched, with the development of the Rabat waterfront as a central focus. The King’s strategy emphasized transforming Rabat into a “showcase of the Kingdom” [5], while also addressing social tensions. To achieve these goals, he prioritized accelerating several flagship projects through attracting foreign investments. This approach proved effective, as evidenced by the 2006 agreements signed with Sama Dubai for the Bouregreg Valley project following the King’s visits to the United Arab Emirates [3].

To overcome the persistent institutional, legal, and operational challenges associated with the Bouregreg Valley project, a senior advisor to the monarch convened a multidisciplinary commission to provide scientific and strategic guidance [4]. The commission’s deliberations resulted in the establishment of SABR-Aménagement, a company that was later restructured into the Agency for the Development of the Bouregreg Valley (AAVB), hereafter referred to as “the Agency.” This institutional entity was formalized through Law No. 16-04, which provides the legal framework for planning procedures, expropriation processes, and delineates the Agency’s responsibilities within the Bouregreg Valley, an area covering approximately 6,000 hectares.

The Agency’s responsibilities encompass a wide range of activities including conducting detailed studies, formulating development plans—particularly the land use plan—securing financial resources, and issuing necessary authorizations (Law No. 16-04, Articles 27-31). It can act as either the project owner or contractor for public infrastructure projects, independently or in collaboration with private investors (Law No. 16-04, Articles 38 and 51). The land use plan incorporates exemptions such as freezes on real estate transactions and building permits and a moratorium on land activities during its development (Law No. 16-04, Articles 4 and 5). The law also facilitates land acquisition through expropriation processes for public utility, allowing the Agency to declare land as necessary for development and exercise expropriation powers (Law No. 16-04, Articles 32-35, 51 et seq.). key innovation of Law No. 16-04 requires the Agency’s director to personally notify affected parties about expropriation inquiries and provide them with draft decrees, a practice that has led to significant local opposition due to perceived injustices and insecurity about land tenure [3].

This paper will explore the interplay between spatial justice, property rights, and land tenure security within the Bouregreg Valley project. It will specifically examine how interactions among various stakeholders—including the Agency and local residents—and their strategies, alongside the resulting regulatory frameworks, influence land tenure security in a complex property rights system. The Bouregreg Valley project, emblematic of the Rabat-Salé region, also reflects broader trends across Morocco.

The Bouregreg project has been the subject of extensive academic discourse, with several works offering critical perspectives, particularly regarding the institutional structure and the derogations that ensued [3,6–10]. Other critiques have focused on the project’s outcomes, notably the high cost of real estate [3,4]. However, this paper aims not to critique the institutional structure per se but to analyze the interactions between key actors—specifically, the Agency and local inhabitants—within the complex framework of property rights, viewed through the lens of land tenure security and spatial justice. It aims to elucidate the relationship between these concepts in the context of the Bouregreg Valley, contributing to broader discussions on property rights and planning practices. The study is based on semi-structured interviews with key actors, complemented by documentary evidence and scientific literature to reinforce its conclusions.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. A Brief Review of the Theoretical Framework of Spatial Justice

The discourse on “justice” within scholarly literature encompasses a myriad of definitions, with objectives often displaying a spectrum of variance, and at times, even contradiction [11,12]. Within the realm of social justice, the conceptualizations that merit attention can be perceived as vacillating between two primary approaches [13]. The first, exemplified by John Rawls [14], endeavors to delineate the universal principles of social justice foundational to an ideal society. This perspective, termed “transcendental institutionalism,” focuses on conceptualizing just institutions and rules. In contrast, Sen [15] advocates for a comparative approach, which scrutinizes tangible social accomplishments. This framework prioritizes specific instances of injustice over the establishment of just societal institutions. Amartya Sen and John Rawls are prominent theorists within the liberal justice tradition, distinguishing their frameworks from other conceptions of justice, such as libertarian and environmental justice theories [4]. These alternative approaches are guided by different foundational principles, including individual freedom, environmental sustainability, property rights, and equity.

Amartya Sen’s theoretical framework provides a sophisticated understanding of social injustice, advancing beyond traditional Rawlsian principles. In his work [15], Sen refines concepts like freedom and primary goods by introducing the notion of “capability,” which he defines as the real opportunity an individual has to pursue a life aligned with their values. Sen [15] argues that freedom is central to his concept of justice, encompassing both substantial and procedural dimensions. The substantial dimension refers to the opportunity to achieve valued outcomes, irrespective of the methods used. For example, an individual might choose to spend a Sunday at home, reflecting their personal preference. The procedural dimension, on the other hand, emphasizes the autonomy in choosing among various possibilities and the importance of freedom from coercion, allowing individuals to make choices that genuinely reflect their preferences [4].

Combining the terms spatial and justice opens up a range of new possibilities for social and political action, as well as for social theorization and empirical analysis, that would not be as clear if the two terms were not used together [16]. It is essential to recognize that while the notion of justice encompasses various interpretations—ranging from liberal, egalitarian, Marxist, to libertarian perspectives—a geohistorical examination of the concept of spatial justice [4,16] suggests that the formulations of spatial justice, emerging in the 1960s and 1970s and since were predominantly influenced by a critical Marxian perspective. Paris during the 1960s, and notably the underexplored intellectual co-presence of Henri Lefebvre and Michel Foucault, became a crucial site for the development of a radically new conceptualization of space and spatiality. This period also saw the emergence of a distinctly urban and spatial conception of justice, most notably encapsulated in Lefebvre’s advocacy for reclaiming the “right to the city” and the “right to difference” [16]. Therefore, spatial justice should not be understood as merely the spatialization of a particular conception of justice but rather as “an intentional and focused emphasis on the spatial or geographical aspects of justice and injustice” [16].

As a starting point, this involves the fair and equitable distribution in the space of socially valued resources and the opportunities to use them [16]. Spatial justice, in this sense, does not serve as a replacement or alternative to social, economic, or other forms of justice but rather offers a critical spatial lens through which justice can be examined. As Soja [17] posits, spatial justice is a tool that brings out the dialectical links between space and justice, suggesting that a critical understanding of the spatiality of injustice occurs within the context of space. To support his argument, Soja [16,17] refers to the concept of locational discrimination—biases imposed on certain populations due to their geographical location—to highlight the manifestations of spatial justice and the spatiality of injustice. He emphasizes how these factors are “fundamental to the production of spatial injustice and the creation of lasting spatial structures of privilege and advantage” [16].

David Harvey’s contributions to the literature expanded and redirected the trajectory of these developments in critical spatial perspectives. For example, David Harvey [18] extended Young’s typology of injustice to the field of geography, demonstrating how these forms of injustice manifest within spatial contexts. In her seminal work [19], Marion Young delineates two primary forms of injustice: domination and oppression. She further distinguishes five specific forms of oppression, prioritizing the collective experiences of social groups over individual perspectives. Domination operates as a constraint impeding certain groups from exercising autonomy in decision-making processes, while oppression constrains these groups from accessing the requisite means to enact their choices. Consequently, just processes are characterized by the absence of both domination and oppression in the interactions among various actors [4]. However, it is pertinent to acknowledge that these forms of injustice may manifest within processes and be reproduced within spatial configurations. This assertion is elucidated by Dikec [20], who conceptualizes spatial justice as “a critique of systematic exclusion, domination, and oppression; a critique aimed at cultivating new sensibilities that would animate actions towards injustice embedded in space and spatial dynamics”.

Peter Marcuse [21] aligns with this framework by delineating two forms of spatial injustices, which extend beyond mere outcomes to encompass the processes underlying spatial arrangements. The first form pertains to the involuntary confinement of particular groups within delimited spaces, characterized by phenomena such as segregation and ghettoization. Marcuse underscores the distinction between voluntary clustering, which does not necessarily entail injustice, and involuntary clustering, which constitutes a significant manifestation of spatial injustice. While statistics may serve as a metric for assessing ghettoization, the essential difference between a ghetto and an enclave lies in the voluntary nature of the clustering [21]. Consequently, the involuntary confinement of groups represents a prominent facet of spatial injustice.

The second form revolves around the unequal distribution of resources over space, encompassing disparities in access to employment, political influence, social standing, income, and wealth [21]. Peter Marcuse [21] clarifies that justice in this context does not advocate for absolute equality but “rather inequality not based on need or other rational distinction, one agreed up by open, informed, democratic processes, one based on legitimate authority rather than relations of power”. While Marcuse does not expound extensively on the spatial manifestations of this injustice, he intimates that it stems primarily from procedural injustices and power differentials. It is noteworthy that various forms of unequal resource allocation can emanate from different manifestations of unjust distribution of power.

These conceptualizations of spatial justice not only elucidate the spatial dimension of justice but also emphasize the critical dialectic between spatiality and justice. Our interpretation of this dialectical relationship is informed by a liberal-egalitarian conception of justice, which is further enriched by the principles of equity, freedom, and implicitly, capabilities. In this paper, our conceptualization of spatial justice is similarly grounded in this framework, integrating the liberal conception of justice, particularly the capabilities approach, with a critical Marxian perspective on spatial justice. This synthesis is employed to demonstrate how the urban fabric inherently raises spatial or geographical questions of justice and injustice. Thus, in the realm of urban (re)development project, the advancement of capabilities can be pursued on dual fronts: firstly, through a substantive lens evaluating whether the project ultimately bolsters the capabilities of the least advantaged groups, thereby mitigating their risk of exclusion and displacement from the project, as elucidated by Peter Marcuse, Edouard Soja and Mostafa Dikec. Secondly, through a procedural perspective, which scrutinizes the project’s processes and engagements with diverse stakeholders, with a particular emphasis on fostering their inclusion in decision-making processes, as articulated by both Peter Marcuse, David Harvey and Iris Marion Young. In the latter approach, the enhancement of capabilities occupies a central position within various participation theories in urban planning, advocating for the empowerment of marginalized groups, often referred to as the “have-nots.” This approach underscores the importance of fostering meaningful participation among these groups to ensure their voices are heard and their needs are addressed effectively.

Hence, we illuminate the interconnection between the capability approach and its spatial understanding, particularly in addressing the forms of spatial injustices outlined by Soja [16], Harvey [18], Young [19], Dikec [20], and Marcuse [21]. By promoting the capabilities of the most disadvantaged groups, we can mitigate instances of domination, oppression, and systematic exclusion, as delineated by these scholars. This intervention primarily operates within the procedural dimension, emphasizing the empowerment of marginalized groups through inclusive decision-making processes. Additionally, addressing the two identified forms of unequal resource allocation highlighted by Marcuse [21] can also be advanced through enhancing capabilities among the least advantaged groups.

2.2. A Brief Review of Land Tenure Security and Property Rights

In this paper, we provide descriptions and definitions of property rights, tenure form, institutions, and tenure security to facilitate consistent discussion on tenure security. These are all concepts that are important for understanding tenure security [22–24]. Here, rights are “particular actions that are authorized,” and a property right is “the authority to undertake particular actions related to a specific domain” [25]. A common way of describing types of rights is the right of access, withdrawal, management, alienation (the ability to sell), and due process of land [26]. Sets and subsets of these right “bundles” are often implied in common ways of discussing different types of property in terms of private, common, or public land [23]. For example, western thought traditions consider rights “well-defined” when all possible rights are held by a single entity or landholder, what is generally referred to as full ownership or private property [26].

Tenure form “determine[s] who can use what resources, for how long, and under what conditions” [27]. Finally, land tenure security is defined as the landholder’s perception that society will uphold rights [28]. It derives from being free of interference from outside sources in individuals’ property ownership and the ability to reap the benefits that accrue from the investments made in that land or free transfer of an individual’s property rights to another person [29,30]. Land tenure security protects landholders from arbitrary removal from their land or residence and, to some extent, makes them feel secure in making sustainable investments in land and property. The loss of those properties can occur in specific circumstances through a legal procedure which must be objective and equally applicable to all properties’ owners [31].

The existing literature distinguishes three types of land tenure security: legal (or de jure), de facto, and perceived security [24,32,33]. Legal or de jure tenure security entails the provision of documented evidence to landholders substantiating their ownership rights over property. These documents originate from formalized rights frameworks, encompassing laws, regulations, zoning ordinances, policies, management plans, protected area designations, or private easements. Such tenure security shields property rights owners from arbitrary dispossession stemming from legal considerations.

The de facto tenure security results from social and political institutions which recognise or accept “legitimate” property rights of people, even if the (formal) registration is absent. In these cases, the role of higher levels of governance and administration can be unclear, poorly enforced, or purposefully disengaged (via “devolution” of management or within autonomous regions, for instance). This leaves land tenure and land governance decisions to local communities [23].

Finally, the concept of perceived tenure security pertains to individuals’ assessments of the probability of eviction, the potential for spatial fragmentation, and the occurrence of land disputes [34].

This study contends that perceived security emerges due to preceding manifestations of land tenure security. Therefore, our analysis centers on these two constructs: de facto and de jure land tenure security, acknowledging perceived security as an outcome resulting from previous forms of land tenure security. The subsequent sections of this paper delve into the nuanced interplay between these distinct yet interconnected facets of land tenure security and spatial justice.

2.3. Relating Spatial Justice to Land Tenure Security

From the preceding examination of the theoretical framework of spatial justice, three distinct forms emerge: procedural, recognitional, and redistributive. Procedural justice, as articulated by [4,16,19,20], constitutes a critique of systemic exclusion, domination, and oppression. This critique primarily scrutinizes the justness of the rules and processes governing the allocation and management of spatial resources, as highlighted by Uwayezu and de Vries [34]. As Achmani et al. [13] suggest, such processes must be “decentred from a democratic and more open process, in which social movements press strong demands, will incorporate equity goals and thereby reduce injustice” [13]. Recognitional justice aims to advocate for the empowerment of the most marginalized groups (the have-nots) by including them in the decision-making as well as and the spatial allocation of resources. It reflects the principle of a fair allocation of spatial resources to all people, especially the creation of opportunities for people who suffer from resource deprivation to access and/or use spatial resources [34]. Redistributive justice aims to strengthen the capabilities of the most disadvantaged by preventing them from exclusion and eviction from the project as well as to avoid the two forms of spatial injustices as defined by Peter Marcuse [21]. It seeks a fair distribution of spatial resources to all users, including the poor and disadvantaged groups, or equal opportunities to use their properties relative to their needs [34].

The three forms of spatial justice portray patterns that can promote land tenure security for all individuals, including the poor and low-income groups. Procedural justice contributes to land tenure security by fostering the capabilities of various stakeholders in the institutionalization of land management rules and processes, which are crafted and implemented in a participatory manner. Participation provides opportunities for voicing, hearing, and recognizing all people’s needs. This allows the local community to adopt strategies that preserve its rights over land resources for their livelihoods (34-35). However, when spatial development programs infringe upon those land rights, the pursuit of procedural justice in combination with recognition and redistribution permits the design and implementation of rules and strategies for fair compensation to affected people so that they can continue their lives [34,36].

In essence, recognition justice promotes land tenure security by advancing the capabilities of diverse stakeholders, particularly those belonging to the most disadvantaged groups. This is achieved by acknowledging and protecting every individual’s right to land resources via inclusive and participatory land management practices, thereby fostering the empowerment of disadvantaged groups. The amalgamation of these forms of spatial justice can facilitate access to land for impoverished individuals and others who lack access to land resources through strategies like land redistribution [35] and other spatial organization processes, such as relocating squatters or slum dwellers to serviced sites. Consequently, while these approaches enhance land tenure security by strengthening people’s connections to land, this research paper will deepen the understanding of the interrelation between spatial justice and land tenure security, specifically how and in which way spatial justice could promote or prevent land tenure security, within an urban re-/development project, in a context of a complex property rights regimes? In this research paper, we aim to discuss these two assumptions:

Assumption 1: Spatial justice, encompassing its three distinct forms, promotes land tenure security by transitioning from de facto land tenure security to de jure land tenure security.

Assumption 2: In the context of urban redevelopment projects characterized by a complex property rights regime, land tenure security is not primarily determined by private property ownership.

3. Materials and Methods

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

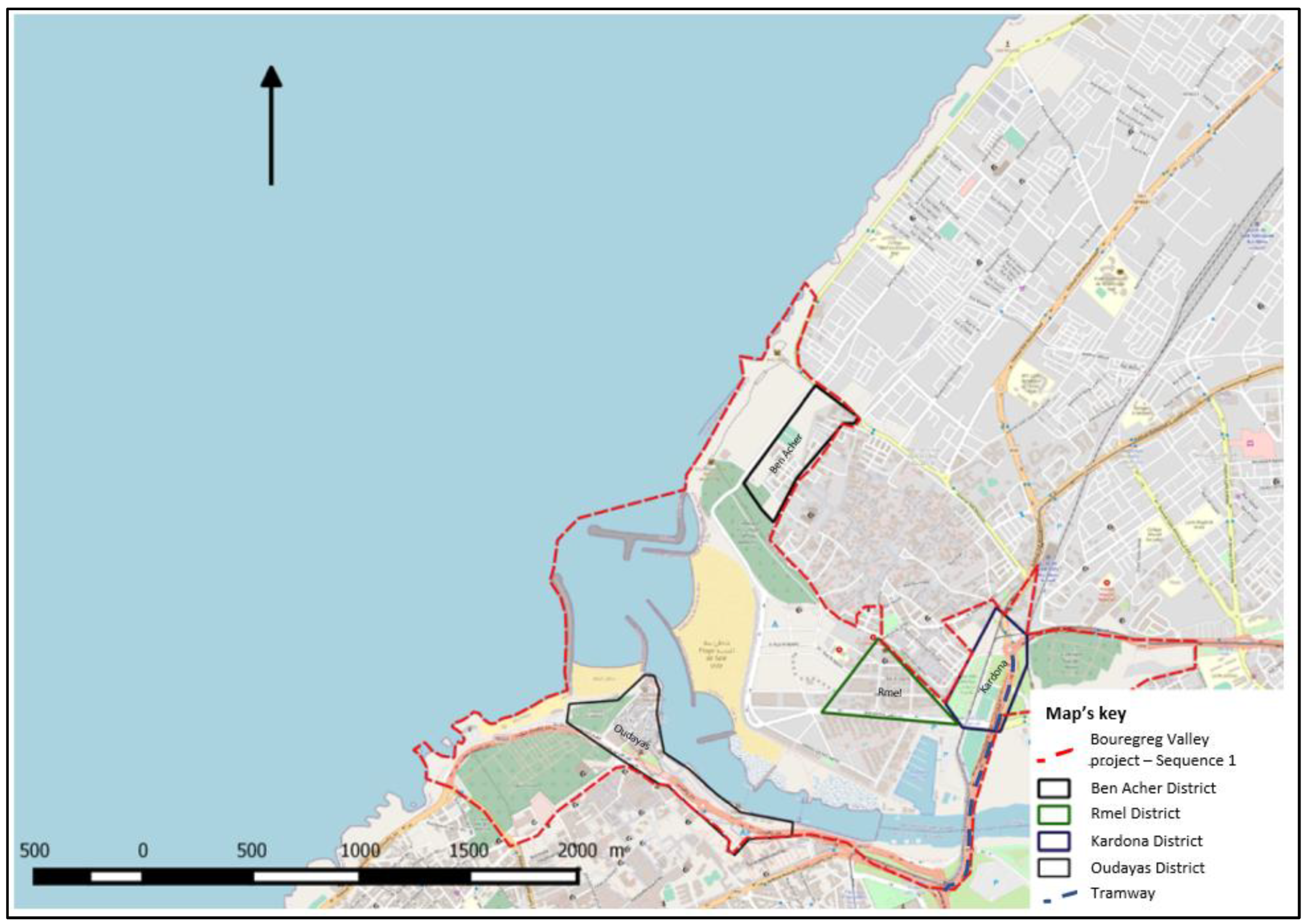

This paper draws upon two illustrative cases of mobilization and interplay among actors observed within the context of the Bouregreg Valley Development in Rabat-Salé, Morocco. These cases pertain to the mobilization efforts in the Ben Acher and Kardona districts, which were investigated as part of my doctoral research defended in 2023. The research commenced in 2020 and received funding from the French Agency for Development.

Figure 1.

Geographical Positioning of the Ben Acher and Kardona Districts within the Bouregreg Valley (Source: [4]).

Figure 1.

Geographical Positioning of the Ben Acher and Kardona Districts within the Bouregreg Valley (Source: [4]).

The research methodology employed a structured approach encompassing three main elements: scientific literature review, analysis of press and official documents, and conducting semi-structured interviews. Official documents consisted of reports, meeting minutes, and deliberations sourced either from public records or directly obtained from local authorities. Special emphasis was placed on scrutinizing the deliberations of the Municipal Councils of Rabat and Salé conducted between 2006 and 2010. Additionally, specific documents published by the Agency were examined, including the Parti d’Aménagement Global [37] and the land use plans known as “le plan d’aménagement special” released in 2008 and 2009.

In addition to technical and administrative documents, the research drew upon various bibliographic sources such as dissertations, books, and scientific articles. Semi-structured interviews were conducted between 2020 and 2022 to elucidate the involvement of various stakeholders, their contributions to the process, and the nature of their demands. Key interviewees included representatives from the municipalities of Salé and Rabat, the Agency, some local associations, and external actors. The selection of actors was carefully planned to capture the perspectives of all parties involved in the conflict. While meeting with representatives of the Agency was crucial, gaining access to them proved challenging due to extensive administrative procedures, which ultimately led to permission being denied. Despite these difficulties, we successfully conducted three interviews, including two with current employees and one with a former one. Although these interviews were not recorded, we promptly drafted memos immediately afterward to ensure the information was preserved.

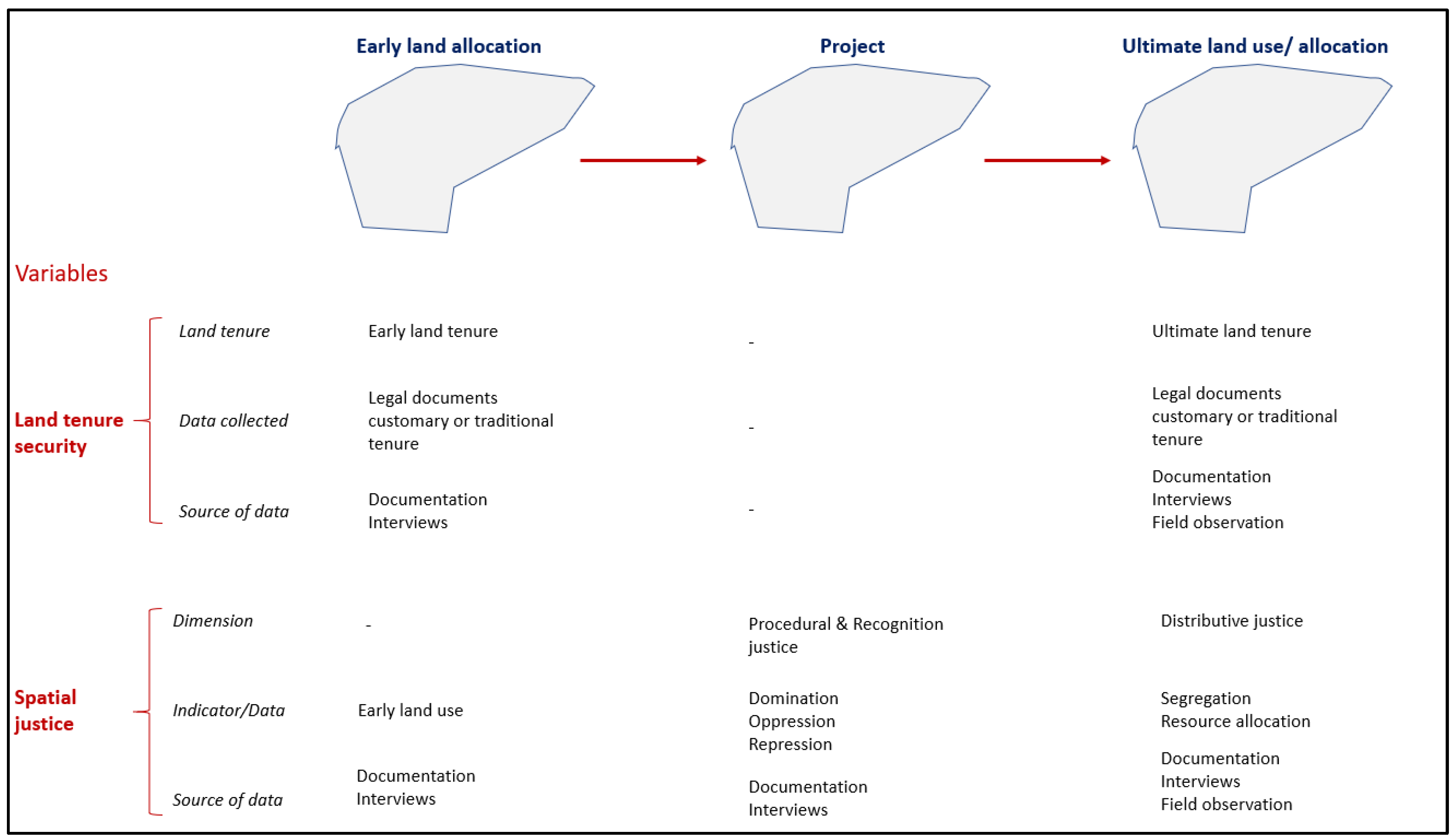

In the districts of Ben Acher and Kardona, the primary focus of our investigation, we engaged with two associations actively involved in the project: Association de Sala Al Mostaqbal and Association de Bouregreg. Unfortunately, some key figures identified in the literature were no longer available, as the negotiations took place over a decade ago. To address this, we triangulated the information by combining direct field observations and existing literature with interviews conducted with these associations. This approach ensured a comprehensive and well-rounded analysis. The following diagram provides an overview of our investigation methodology.

Figure 2.

Overview of our investigation methodology (Source: [4]).

Figure 2.

Overview of our investigation methodology (Source: [4]).

4. Implementing the theoretical framework of spatial justice and land tenure security on two conflicts occurred in the Bouregreg Valley re-/development

The following sections of this paper explore the interaction between spatial justice and land tenure security by examining two conflicts that have emerged within the Bouregreg Valley project.

4.1. Regulating the Conflict Between the Ben Acher District Residents and the Agency

The Bab Chaâfa-Sidi Ben Acher district, situated west of the medina of Salé overlooking the city’s seafront, constitutes a non-regulated housing fabric that originated in the 1960s [3]. This area falls within the development perimeter of the Bouregreg project and comprises predominantly privately owned land. Initially, the land consisted of agricultural parcels that were subdivided and sold to individuals, who constructed homes without formal building permits [3].

A significant event occurred on November 18, 2007, when a technician purportedly representing the Agency for the Development of the Bouregreg Valley approached residents of this district. He claimed to be conducting a survey of the houses with the intention of demolishing them to make way for hotels, cafes, and other amenities catering to foreign tourists [3]. Despite denials from the Agency, who asserted that the individual was associated with land speculators aiming to acquire property for resale, this incident served as a catalyst for the mobilization of district residents against the Bouregreg valley development project.

Following this incident, residents swiftly reactivated the “le bon voisinage” Association to advocate for defending residents’ interests and coordinating their mobilization efforts. Subsequently, a committee was established to organize and represent the residents’ concerns, leading to negotiations with the Agency. Just 21 days after the technician’s visit, on 9 December 2007, the committee dispatched an open letter to the director of the Agency.

In this letter, drafted in both Arabic and French, the committee issued a stern warning: “Given the Bouregreg project’s intention to construct new buildings in our neighborhood to cater to the entertainment needs of foreign visitors, the residents of these neighborhoods refuse to comply with the Agency’s demands” [38]. The Committee asserted that the inhabitants were unwilling to be displaced from their homes and resettled elsewhere, categorically rejecting the notion of agreeing to relocation in exchange for substantial compensation [38].

Nine months later, as the draft land use plan of the Bouregreg Valley entered the phase of public investigation and communal deliberations, the plan designated the Bab Chaâfa-Sidi Ben Acher district as a restructuring zone ZR-4 [39]. The land use plan outlined the envisaged transformation of this sector as part of the wider urban development strategy, emphasizing the planned expansion of the medina of Salé towards the sea. This expansion was envisioned to incorporate the development of green spaces and promenades along the ramparts and built front of the medina of Salé. Additionally, the land use plan stipulated that restructuring zones (RZ) and project zones (ZP) were to be declared as of public utility through a decree accompanying the promulgation of the land use plan [39]. Consequently, these zones would be subject to operational plans aimed at their development [39].

In response to the proposed developments outlined in the Bouregreg Valley project, the “le bon voisinage” Association transitioned into a public phase of contestation and mobilization. Seeking to avoid isolation in their negotiations with the Agency, the committee forged a collaboration with the National Instance for the Protection of Public Property in Morocco (INPBPM) on 5 October 2008 [3]. The INPBPM was actively engaged in a public awareness campaign against the approach adopted in the development of the Bouregreg Valley and had established a Coordinating Committee to combat the compensation resulting from land expropriation in the Wilaya of Rabat-Salé-Zemmour-Zaêr [9].

This collaboration empowered the “le bon voisinage” Association to organize a series of sit-ins in conjunction with other associations (Interview with Association Sala Al Mostaqbal, 11 Mars 2021). The first sit-in occurred on October 14, 2008, in front of the Parliament, followed by subsequent protests on October 28, 2008, in front of the Municipality of Salé headquarters and in front of the Prefecture of Salé. The last two sit-ins were held in the Kardona neighborhood (Salé-Lamrissa district) [3].

The efforts of the Committee yielded a significant breakthrough when the director of the Agency personally assured residents, during a visit to the Jamaâ Ben Ayyad Mosque, that there would be no expropriation in the sector [3]. Consequently, the Agency was compelled to reevaluate the provisions pertaining to the Bab Chaâfa-Sidi Ben Acher sector and modify the final version of the development regulations accordingly. The revised document indicated that the sector would only undergo “redevelopment of public spaces allowing the creation of esplanades, walking areas, and green spaces” [40]. Furthermore, the revised version stipulated that within the framework of operational studies conducted in this restructuring zone, the local population would be retained on-site, and existing buildings would be upgraded with necessary facilities to meet standard requirements [40].

4.2. Regulating the Conflict Between Kardona’s Residents and the Agency

In the Kardona neighborhood, a total of 15 parcels of undeveloped land were identified, which had not received authorization for urban development in accordance with prior planning schemes [41]. Concurrently, there existed 19 developed parcels accommodating 82 households, as documented by Plaa in 2009. According to the new land use plan, the neighborhood was situated along the Moulay El Hassan bridge axis [39]. This entailed the imminent demolition of existing structures to facilitate the implementation of a tramway system, the establishment of public amenities, and the establishment of an urban zone delineated as “medium-sized city M2.5,” characterized by a stipulated maximum building height of six stories [39].

As outlined by the Agency Director, the Kardona neighborhood is slated for expropriation and subsequent demolition due to its problematic location, presenting limited alternative options for intervention [42]. Consequently, the district is earmarked for expropriation, necessitating the identification of beneficiaries and the proposal of compensatory measures [42]. When property ownership presents no impediments, the Agency initiates negotiations for amicable acquisition (interview with a land officer at the Agency on May 28, 2021). However, in instances where negotiations fail to yield agreements, expropriation measures are enforced (interview with a land officer at the Agency on May 28, 2021).

However, the process of identifying the beneficiaries has unearthed complexities inherent to property ownership in Morocco (interview with a land officer at the Agency on May 28, 2021). Specifically, certain landowners are not registered in the national Cadastre, or possess joint ownership with irregularities in succession procedures, or occupy lands undergoing registration processes (Ibid.). In these circumstances, the Agency disburses funds to the “Central Bank,” also known as the “Caisse de Dépôt et de Gestion CDG,” in accordance with court decisions (interview with a land officer at the Agency on May 28, 2021).

Regarding tenants, the Bouregreg development law lacks specific provisions for compensation (interview with a land officer at the Agency on 28 May 2021). Consequently, compensation adheres to the guidelines stipulated in Law 7-81, which asserts that “the judicial authority, responsible for assessing compensation, may uphold the provisional compensation proposed by the expropriating authority as provisional compensation

1.” In instances where residents occupy properties informally, lacking formal contracts or legal coverage, the Agency integrates them into the compensation framework (interview with a land officer at the Agency on May 28, 2021).

To process this compensation, the Administrative Tribunal has established an Expertise Commission tasked with determining the compensation amount

2 (See, Plaa, 2009). The commission’s report, based on the chosen referential rental price for both developed and undeveloped land, harkens back to the rates of 2005 (Rapport de la commission du Tribunal Administratif portant sur la procédure d’expropriation pour utilité publique du quartier de Kardona in [41]). According to this report, tenants who have resided since 1995 are entitled to one year’s rent as compensation, those residing since 1981 receive two years’ rent, and those who have been residents since 1962 receive three years’ rent [41]. The compensation criteria remain consistent for both residential and commercial tenants [41].

5. Discussion and Results

The residents of the Ben Acher district inhabit an area lacking a formalized land use plan, thereby precluding them from possessing formal rights to private property. However, they enjoy a de facto tenure security due to their longstanding residence under a community-based arrangement facilitated with the involvement of local authorities. Recently, decisions made by the public developer have transitioned this tenure security from de facto to de jure.

The Agency has not dominated, oppressed, or excluded the residents throughout this development. On the contrary, they have been actively engaged in decision-making processes and have been retained in their current location by the latest decision from the agency. Consequently, the outcomes of this project have, to some extent, resulted in an enclaved area. However, as Peter Marcuse [21] noted, this does not constitute spatial injustice, as voluntary group confinement does not inherently signify a form of spatial injustice. Thus, the project’s outcomes and processes underscore the Agency’s commitment to enhancing the capabilities of residents, particularly those who are among the least advantaged individuals in the urban agglomeration.

This transformation has not only facilitated the promotion of land tenure security among the residents but has also provided them with legal documentation to substantiate their property rights in these lands. This underscores the notion that recognition and procedural justice play pivotal roles in enhancing land tenure security by upholding and safeguarding everyone’s right to land resources through inclusive and participatory management practices. The residents’ access to land and the advantages and benefits stemming from the land use change have been safeguarded and assured.

The residents of the Kardona district inhabit an area governed by a formal land use plan. However, informal practices persist, primarily among tenants who often lack formal contracts with landowners. Consequently, the issue of land tenure security manifests differently: it is de facto for informal tenants and de jure for landowners and tenants with formal contracts.

With the implementation of the new land use plan, the district is slated for redevelopment to accommodate public transportation infrastructure, specifically the tramway. This shift from residential to public infrastructure has raised significant concerns regarding the displacement of residents and, more broadly, the preservation of land tenure security as residents faces potential relocation. I will elaborate on these points in the following discussion.

Firstly, concerning the urban area’s inhabitants, the extensive infrastructure development presents numerous opportunities for equitable and dignified commuting while significantly enhancing access to resources for a sizable portion of the population. A pivotal document in this context is the 2020 report by the French Development Agency (AFD) [43] which examines the tramway’s impact on accessibility and population dynamics. According to the findings of this report, tramways account for 26% of public transportation usage, which is a substantial contribution to the transportation network. Particularly noteworthy is the tramway’s service to modest neighborhoods in Rabat, such as Yaacoub Al Mansour, and in Salé, notably Lamrissa, Bettana, Tabriquet, and Hay Karima (AFD, 2020). Importantly, the tramway’s fare is both affordable and competitive when compared to alternative modes of transportation, and in some instances, it even offers more cost-effective options than those provided by taxis (a typical journey from Salé Tabriquet to Rabat Agdal incurs a tramway fare of €0.60, whereas taxis charge a minimum fare of €1.00).

Therefore, while the transition from residential to public infrastructure may entail land tenure insecurity for local inhabitants in the form of displacement, it simultaneously opens up numerous opportunities for a significant portion of the population across the agglomeration. The tramway has significantly contributed to enhancing the capabilities of the neighborhood residents and those residing across the entire agglomeration. The construction of the tramway counters localizational discrimination [16,44] by providing accessible public transportation to both low- and middle-income residents of Salé and Rabat, rather than exclusively serving the elite residents of Rabat.

Secondly, although the Kardona district residents have been displaced to make way for the construction of the tramway, they were provided compensation for vacating their premises. While this displacement may ultimately enhance the capabilities of a significant number of individuals, questions arise regarding why residents whose premises were subject to a residential project were expropriated and evicted.

Moreover, crucial details such as the amount of compensation and the negotiation process remain undisclosed, leaving uncertainties regarding whether property owners received adequate compensation to secure equivalent properties, for instance. While delving into the intricacies of this discussion falls beyond the scope of this paper, it prompts considerations regarding the extent to which financial compensation can mitigate the insecurity of land tenure. Nonetheless, it can be argued that equitable compensation necessitates a process devoid of domination, oppression, and exclusion.

Thirdly, the displacement of residents raises the question of whether formal rights and land tenure guarantee land tenure security systematically. However, this displacement was accompanied by compensation for both formal and informal tenants and landowners, indicating that the Agency has recognized their existence. While this recognition may not grant them equivalent land access, fair financial compensation serves as a form of non-material promotion of land tenure security. In other words, land tenure security does not always necessitate maintaining residents in their current location. Instead, equitable and fair compensation, coupled with the promotion of capabilities and opportunities through the new land use, can enhance land tenure security for a significant number of inhabitants.

In both cases, the Agency has instituted a participatory process, encompassing both formal and informal stakeholders, thereby providing opportunities for voicing, hearing, and recognizing all people’s needs. This inclusive approach enables the local residents to adopt strategies that safeguard their rights over land resources essential for their livelihoods. Furthermore, this study highlights that procedural justice plays a crucial role in bolstering land tenure security through the institutionalization of land management rules and processes. These rules and processes are crafted and implemented in a participatory and inclusive manner, ensuring that the interests and concerns of all stakeholders are considered and addressed.

It is crucial to acknowledge that distributional justice alone does not guarantee systematic land tenure security, especially when assessments cannot be made until hearings and participatory mechanisms have been conducted. In other words, distributional justice is contingent upon procedural and recognitional justice, which exerts a greater influence on land tenure security. For instance, an intervention in the Ben Acher district involving the demolition of existing structures and the construction of large, socially mixed buildings might appear to align with distributive justice principles. However, if this intervention goes against the will of the area’s inhabitants and is not conducted through inclusive and participatory processes, it does not truly embody distributive justice and consequently land tenure security. Instead, procedural justice, which involves fair and transparent decision-making processes, holds greater significance in promoting land tenure security.

6. Conclusions

The two case studies presented in this paper underscore the multifaceted nature of insecurity, which can manifest in both de facto and de jure contexts. We have demonstrated that spatial justice is a crucial factor in promoting land tenure security within complex property rights regimes. Our discussion has highlighted not only the centrality of space in the concept of spatial justice but also the dialectic between spatiality and justice or injustice. As Mustafa Dikec [10] noted, “Spatiality of injustice is based on the premise that justice has a spatial dimension to it, and that one can observe and analyze various forms of injustice manifest in space. Injustice of spatiality shifts focus from spatial manifestations of injustice to structural dynamics that produce and reproduce injustice through space.”

Through these case studies, we have shown that the formalization of land rights by the state does not necessarily equate to land tenure security for landholders. For example, in Kardona, privately owned land was expropriated, whereas residents of the Ben Acher district, who lacked formal property rights, were allowed to remain in situ. This illustrates that land tenure security is not always guaranteed by private property ownership or de jure frameworks: “Too often security is equated with private land and formalized title, but simply creating rules or allocating rights through some of these formal mechanisms does not guarantee the security of rights for an individual” [24].

Urban (re)development projects inherently challenge traditional notions of property rights and land tenure. The transformation of land allocation, use, and access creates significant challenges to land tenure security for both residents and developers. This paper has demonstrated that spatial justice, in its three dimensions—distributive, procedural, and recognitional—provides a pertinent and effective framework for promoting land tenure security within urban development projects and broader urban planning initiatives. Our understanding of spatial justice is informed by the capabilities approach and contemporary scholarly contributions from [16-21,44].

In complex property rights regimes, land tenure security is not primarily determined by private property ownership. Our case studies show that security arises from a just process—one that ensures procedural and recognitional spatial justice. As Robinson & Diop [23] argue, true security necessitates the presence of appropriate institutions capable of impartially adjudicating conflicts and claims.

Finally, security in land tenure does not merely involve transitioning from de facto to de jure status by distributing property rights to those with informal claims. Security also entails fair compensation in cases of compulsory expropriation, accompanied by just distributive outcomes. Therefore, expropriation, even when extending de jure property rights, does not necessarily imply de jure land insecurity. In conclusion, we demonstrated the dialectic between land tenure security and spatial justice, showing that, on the one hand, spatial justice is vital for securing land tenure within the property rights regime. On the other hand, land tenure security itself can be effectively observed and analyzed through the lens of spatial justice.

Notes

| 1 |

However, expropriated parties can challenge the amount of provisional compensation before the judge who may reassess it or seek assistance from experts whenever an evaluation difficulty arises" (Moroccan Agency for Solar Energy, July 2017; p.13). |

| 2 |

This commission includes the General Secretariat of the Salé Prefecture, the Housing Delegation, the Urban Planning Division, and the Local Communities Division of the Prefecture, and other services directly dependent on the ministry [41]. |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y.; methodology, A.Y.; validation, A.Y. and D.W; formal analysis, A.Y; investigation, A.Y.; resources, A.Y.; data curation, A.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Y.; writing—review and editing, A.Y. and D.W.; supervision, A.Y. and D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAVB |

Agence d’aménagement de la Vallée de Bouregreg |

| AFD |

Agence Française de Développement |

| PAG |

Parti d’Aménagement Global |

| PAS |

Plan d’Aménagement Spécial |

| SABR |

Société d’Aménagement de Bouregreg |

| INPBPM |

Instance Nationale pour la Protection des Biens Publics au Maroc |

References

- Bouchaf, Ouafae. Communication publique et négociation: cas de l’Agence pour l’Aménagement de la Vallée du Bouregreg. Thèse de doctorat, Université Côte d’Azur, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alillouch, Rachid, Majid Mansour, and Hassan Radoine. Le Projet d’aménagement de La Vallée Du Bouregreg. Contexte et Modalités de Conception et de Mise En Œuvre d’un Projet Urbain Pour Un Site Vulnérable. 2019; 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mouloudi, Hicham. Les Ambitions d’une Capitale: Les Projets d’aménagement Des Fronts d’eau de Rabat; Description Du Maghreb; Centre Jacques-Berque: Maroc, 2015; Available online: http://books.openedition.org/cjb/598.

- Achmani, Youness. Le projet urbain au prisme de la justice spatiale et du paradigme de la ville juste : des gagnants et des perdants. Cas des projets d’aménagement de la Vallée de Bouregreg (Rabat-Maroc) et de Saint-Sauveur (Lille-France). PhD Thesis, Tours, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zemni, Sami, and Bogaert Koenraad. Morocco and the Mirages of Democracy and Good Governance. UNISCI Discussion Papers; 1 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Amarouche, Maryame, and Koenraad Bogaert. Reshaping Space and Time in Morocco : The Agencification of Urban Government and Its Effects in the Bouregreg Valley (Rabat/Salé). MIDDLE EAST - TOPICS & ARGUMENTS 2019, 12, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouloudi, Hicham. La réaction de la société civile dans la production des grands projets urbains au Maroc : Entre le soutien inconditionnel et le rejet total. Les Annales de la recherche urbaine 2009, 106, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les Projets d’aménagement Des Fronts d’eau de Rabat, Entre Logiques de Développement Urbain et Internationalisation. In Le Maroc Au Présent : D’une Époque à l’autre, Une Société En Mutation, edited by Assia Boutaleb, Baudouin Dupret, Jean-Noël Ferrié, and Zakaria Rhani; Description Du Maghreb; Centre Jacques-Berque: Maroc, 2016; pp. 61–75. Available online: http://books.openedition.org/cjb/1000.

- Hamidi, Leila. Le projet d’aménagement du Bou Regreg : un projet social ? Focus sur les populations des pêcheurs, poissonniers et barcassiers. Master thesis, École d’ingénieurs polytechnique de l’université de Tours, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel, Pierre-Arnaud. Faire du « grand projet » au Maghreb. L’exemple des fronts d’eau (Casablanca et Tunis). Géocarrefour 2008, 83, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, David M. Social Justice Revisited. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 2000, 32, 1149–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, David Marshall. Geography and Social Justice; Blackwell: Oxford, Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne et d’Irlande du Nord, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Achmani, Youness, Walter T. de Vries, José Serrano, and Mathieu Bonnefond. Determining Indicators Related to Land Management Interventions to Measure Spatial Inequalities in an Urban (Re)Development Process. Land 2020, 9, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, John. Théorie de La Justice. Translated by Catherine Audard; Éd. du Seuil: Paris, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Amartya. The idea of justice; London, Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne et d’Irlande du Nord, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, Edward William. The City and Spatial Justice. 2009. Available online: https://www.jssj.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JSSJ1-1fr3.pdf.

-

Seeking spatial justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, Etats-Unis d’Amérique, 2010.

- Harvey, David. Social Justice, Postmodernism and the City. In Readings in Urban Theory, edited by Susan S. Fainstein and Scott Campbell, 2nd ed.; London, 1992; pp. 386–402. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Iris Marion. Justice and the politics of difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton (N.J.), Etats-Unis d’Amérique, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dikeç, Mustafa. Justice and the spatial imagination. In Searching for the just city: debates in urban theory and practice, edited by Peter Marcuse, James Connolly, Johannes Novy, Ingrid Olivo, Cuz Potter, and Justin Steil, 72–88; London, Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne et d’Irlande du Nord, Etats-Unis d’Amérique, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuse, Peter. Spatial Justice: Derivative but Causal of Social Justice. In Justice et Injustices Spatiales, edited by Bernard Bret, Philippe Gervais-Lambony, Claire Hancock, and Frédéric Landy, 76–92. Sciences Humaines et Sociales; Presses universitaires de Paris Nanterre: Nanterre, 2009; Available online: http://books.openedition.org/pupo/420.

- Arnot, Chris D., Martin K. Luckert, and Peter C. Boxall. What Is Tenure Security? Conceptual Implications for Empirical Analysis. Land Economics 2011, 87, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Brian E., and Moustapha Diop. Who Defnes Land Tenure Security? De Jure and De Facto Institutions. Land Tenure Security and Sustainable Development 2022, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gelder, Jean-Louis van. What Tenure Security? The Case for a Tripartite View. Land Use Policy, Forest transitions 2010, 27, 449–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlager, Edella, and Elinor Ostrom. Property-Rights Regimes and Natural Resources: A Conceptual Analysis. Land Economics 1992, 68, 249–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooter, Robert, and Thomas Ulen. Law and Economics, 6th ed.; Berkeley Law Books, 1 July 2016; Available online: https://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/books/2.

- FAO LAND TENURE STUDIES. Land Tenure and Rural Development, FAO edition; Rome, Italy, 2002; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/y4307e/y4307e05.htm.

- Sjaastad, Espen, and Daniel W. Bromley. The Prejudices of Property Rights: On Individualism, Specificity, and Security in Property Regimes. Development Policy Review 2000, 18, 365–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, John W., and S. E. Migot-Adholla. Searching for Land Tenure Security in Africa; Kendall/Hunt: Dubuque, Iowa, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Clover, J., and S. Eriksen. The Effects of Land Tenure Change on Sustainability: Human Security and Environmental Change in Southern African Savannas. Environmental Science & Policy 2009, 12, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. The Habitat Agenda Goals and Principles, Commitments and the Global Plan of Action; International Law & World Order, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Simbizi, Marie Christine Dushimyimana, Rohan Mark Bennett, and Jaap Zevenbergen. Land Tenure Security: Revisiting and Refining the Concept for Sub-Saharan Africa’s Rural Poor. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 231–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asperen, PCM van, and JA Zevenbergen. Can Lessons Be Learnt from Improving Tenure Security in Informal Settlements?: ENHR Intenational Conference 2007; Edited by P Boelhouwer, D Groetelaers, and E Vogels; ENHR Sustainable Urban Areas, 2007; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Uwayezu, Ernest, and Walter T. de Vries. Indicators for Measuring Spatial Justice and Land Tenure Security for Poor and Low Income Urban Dwellers. Land 2018, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Nancy. Recognition without Ethics? In Recognition and Difference; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, 2001; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliarino, Nicholas K., Yakubu A. Bununu, Magbagbeola O. Micheal, Marcello De Maria, and Akintobi Olusanmi. Compensation for Expropriated Community Farmland in Nigeria: An In-Depth Analysis of the Laws and Practices Related to Land Expropriation for the Lekki Free Trade Zone in Lagos. Land 2018, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agence de Bouregreg. Parti d’Aménagement Global PAG; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Asoociation “le bon voisinage. Lettre Adressée Au Directeur de l’Agence d’aménagement de La Vallée de Bouregreg; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- AAVB. Plan d’aménagement Spécial; 20 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- AAVB. Plan d’aménagement Spécial; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Plaa, Clément. Les marges du Projet d’Aménagement de la Vallée du Bouregreg : Intégration et négociations; Mémoire de Maîtrise de Géographie, Université de Tours, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Conseil municipal de Salé. Délibération Du Conseil Municipal de Salé; 28 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dalahais, Thomas, Philippe Bossard, and Juliette Alouis. Évaluation Ex Post de La Phase 1 Du Tramway de Rabat-Salé et de La Ligne 1 Du Tramway de Casablanca; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, Edward William. Seeking spatial justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, Etats-Unis d’Amérique, 2010. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).