1. Introduction

In Namibia, unplanned rapid urbanization has led to the growth of informal settlements. Weber and Mendelsohn [

1] projected that by 2025, the predominant form of housing in Namibia will be urban shacks. Inhabitants occupying these shacks do not own the land, lack basic services, do not comply with planning regulations, and often lack permits [

2]. The housing programs introduced in 1992 the earliest by the government of Namibia, focused on providing houses and loans to the impoverished inhabitants, whereas the current ones introduced after 2010, focus on providing tenure security [

1]. Tenure security is a key factor for suitable housing, enabling access to other important factors like services and habitability [

3]. According to Chigbu and Enemark [

4], secure tenure rights enable impoverished people to invest in their property and livelihood without fear of eviction.

In the informal settlements of Namibia, land tenure security is ensured through an upgrading process. The Flexible Land Tenure System (FLTS) is utilized to deliver land. The Flexible Land Tenure Act (FLTA), passed in 2012, is the foundation of the FLTS, which ensures land tenure security through several titles with reduced requirements [

5]. Low-income families living in informal settlements in urban areas throughout Namibia are the main recipients of this system. According to Ulrich and Meurers [

5], the FLTS is a rapid and cost-effective method of land delivery and it is not a replacement for urban planning. Planned urbanization is pivotal in creating inclusive cities. The New Urban Agenda [

6] also highlights the importance of urban planning in providing secure land rights and suitable housing for women and girls and delivering the basic services to meet their needs and rights. In the Global South, women are less likely to own or control land, even though they perform more than half of all agricultural activities. This imbalance impacts general development activities as well. Hence, the need to close the gender gap in land ownership becomes evident [

4].

Namibia has made significant progress in closing its gender gap—reaching 80.5% according to the World Economic Forum [

7]. However, this data does not specifically address the gender gap among the marginalized inhabitants of the informal settlements, which constitute 25% of the population [

8]. To close the gender gap a widely accepted approach is gender mainstreaming [

9]. This approach ensures that a gender sensitive perspective is central to all activities such as policy development, research, advocacy, dialogue, legislation, resource allocation, planning, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of policies and programs [

10]. Gender-mainstreamed approaches are necessary in informal settlements already suffering from resource imbalances.

One example of a land tenure securing process that is considered gender-sensitive is Freedom Square, one of the largest former informal settlements in Gobabis, Omaheke, Namibia. Formalized through a decade-long upgrading process, the inhabitants now have security of tenure and access to some basic services. There, land was co-produced with the inhabitants and the local authority of Gobabis, and is considered to be a women-led process by the involved stakeholders [

11,

12]. This research has explored the perspective of the women from Freedom Square actively engaged in the upgrading process, which was one of the pilots implementing the FLTA. The research was conducted under the umbrella of the SDGs GoGlocal! project as a trilateral partnership between the University of Stuttgart, Ain Shams University and Namibia University of Science and Technology. The 2-month field data collection took place between April and May 2024.

2. Research Objectives

The women inhabitants of Freedom Square provided input for initiating the upgrading process in Freedom Square through their active engagement and leadership. The first research objective was to analyze how challenging or accommodating the process was for women’s participation, whether they faced barriers, and whether the process acknowledged their social and economic challenges. Additionally, analyzing the stakeholders involved at each phase of the upgrading process and cross-referencing these with women’s participation has helped identify their influence on women’s engagement. The second objective was to evaluate the immediate outcomes. Since the participating women were motivated by specific goals, it was crucial to first understand these goals and then compare them with the current situation to assess whether their participation yielded the desired outcomes. The final objective was to evaluate the long-term impact on the lives of the participating women by analyzing their current conditions. These objectives led to the development of the following research questions-

What motivated women to participate?

What was the influence of stakeholders on women’s participation?

What challenges did women face during their participation?

What was the output of women’s participation?

What is the impact of women’s participation?

3. Research Background

In the informal settlements of Namibia, resource imbalances are a major challenge [

13]. Therefore, the settlement upgrading processes need to be inclusive, ensuring that resource imbalances do not continue. According to UN-Habitat [

14], inclusivity in informal settlements means addressing the needs of vulnerable and marginalized populations, which include women. Chigbu, Paradza, and Dachaga [

15] argue that efforts to improve African women’s land tenure security often benefit the privileged while overlooking marginalized women. The marginalized women living in these informal settlements face particular obstacles such as being excluded from basic services both because they have not been recognized as planned urban area inhabitants and because they are women, a gender-based exclusion. The informal settlements offer no security or privacy for women. Moreover, they face constant fear of eviction, must walk long distances for water due to a lack of nearby connections, and lack of sanitation facilities which force them to relieve themselves in open areas or bushes. Being provided safe housing, marginalized women in Namibia’s informal settlements, who account for half of the population, can concentrate on improving their lives through economic and social advancement. Tenure security is one primary step of safe housing.

African women’s access to land and tenure security has not been one straightforward path throughout history. According to Alden Wily [

16], tenure means landholding and customary land tenure is the system through which most rural African communities manage ownership, possession, access, and the regulation of land use and transfer. Chigbu, Paradza, and Dachaga [

15] mention that women’s civil status within the community influences their access to land. Werner [

17] highlighted the eviction of widows from the land they cultivated as a major issue in Namibia’s communal system. Although further discourse is needed regarding women’s rights in the communal system, it can be deduced that within Namibia’s communal system, both women and men have access to land primarily through land use rights.

During the colonial period, foreign colonial administrators and local patriarchal tenure arrangements continued to deny women land rights, leading to a lack of tenure security [

18]. Since 1995, however, Namibia has initiated land reform policies focusing on women through Redistributive Reform, which recognizes ‘their rights within family and marriage through joint registration rights’ [

18]. The FLTS also aims to adopt a gender mainstream approach but fails to establish clear terminologies, particularly due to the complex family formations found in informal settlements. The guide to the FLTA published by the Ministry of Land Reform [

19], which explains the FLTS in key points to its target users, mentions that the landowner shall be the ‘Head of Household’. It provides examples that seem to reinforce the idea that a woman could be the ‘Head of Household’ only in the absence of a man in the family. Otherwise, it suggests joint tenure for couples married legally (not in community). However, this leaves women cohabiting with their partners without tenure security.

Additionally, from the FLTS guidelines, it is apparent that how the existing institutions or the local authorities will conduct the process is still being determined. Whether the implementation of this act will require new institutions or burden the existing ones is yet to be explored. In the case study for this research, this task was conducted by a group consisting of ministries, local authorities, and inhabitants, thus co-creating land. Further application of this law in other informal settlements will help the responsible authorities to try out different combinations of stakeholders to figure out the easiest and most cost-effective way of implementation, resonating with the original intention of this law.

4. Materials and Methods

This research followed a qualitative method to answer the research questions set in article 2. Primary and secondary literature regarding land tenure in Namibia, informal settlements, and upgrading processes were analyzed as sources of background information and data validation. In Gobabis and Windhoek, Namibia, semi-structured interviews were conducted and validated through a focus group discussion. Eight experts from Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST), Namibia Housing Action Group (NHAG), and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) were interviewed for their knowledge and direct involvement in Freedom Square’s upgrading process.

The interview questions (

Appendix A) consisted of six main questions centered on women and their participation in the process. Additionally, seventeen women and three men inhabitants of Freedom Square were interviewed. The interviews were conducted in the local language, Afrikaans, and translated by an interpreter (Freedom Square inhabitant) during the interview. The interviewed women were contacted through the municipality and sampled according to the criteria of being a Freedom Square inhabitant, a women participant in the upgrading process, community leaders, and regular inhabitants. The interview questions (

Appendix B) focused on their family, initiation to participation, and relationship to the stakeholders. They were also asked to discuss the challenges faced during the process and what they currently face when they have land tenure. The interviews were followed by a visit to the Freedom Square settlement to observe the upgraded formal settlement. In the second phase of data collection, a focus group discussion was conducted at the Epako municipality. The interviewed inhabitants of Freedom Square were invited to participate and validate the extracted data from their interviews.

The collected data was also analyzed in two phases. While primary and secondary data were analyzed to get an overall background of the project and as supporting information to validate the analyzed data, the semi-structured interviews served as the main source of data to answer the research questions. A total of 28 interviews were recorded and transcribed. Four themes were extracted from the transcriptions to code the interviews. 33 codes (

Appendix C) were generated manually under the themes. Atlas.ti was used to code the relevant quotations of each transcription, resulting in a database of interview quotations under each theme and code. Initially, a timeline of the upgrading process was created from the database and the available secondary literature. The community later validated this timeline during the focus group discussion mentioned in the previous section. Missing information was added, resulting in the current timeline. The involved stakeholders were identified from the interview database and the secondary literature available before being validated by the workshop participants. Then, from the 17 interviewed women, a storyline of their participation was generated. This gave distinctive results for each of the participants. Their challenges were identified from there and later validated in the workshop. Women‘s motivations to participate were identified from the entry points and the interviews. They were validated in the same workshop. Finally, the current situation of the settlement, its built environment and services, and the socio-economic situation of the participating inhabitants were considered.

Due to the time limitations, the research could not consider all stakeholders’ perspectives. The Freedom Square upgrading process started twelve years before this research was conducted. Therefore, the complete timeline of the process and actions were derived from participants’ memories of the events, as documentation has only been done by stakeholders during each of their involvement phases.

5. Results

5.1. The Upgrading of Freedom Square

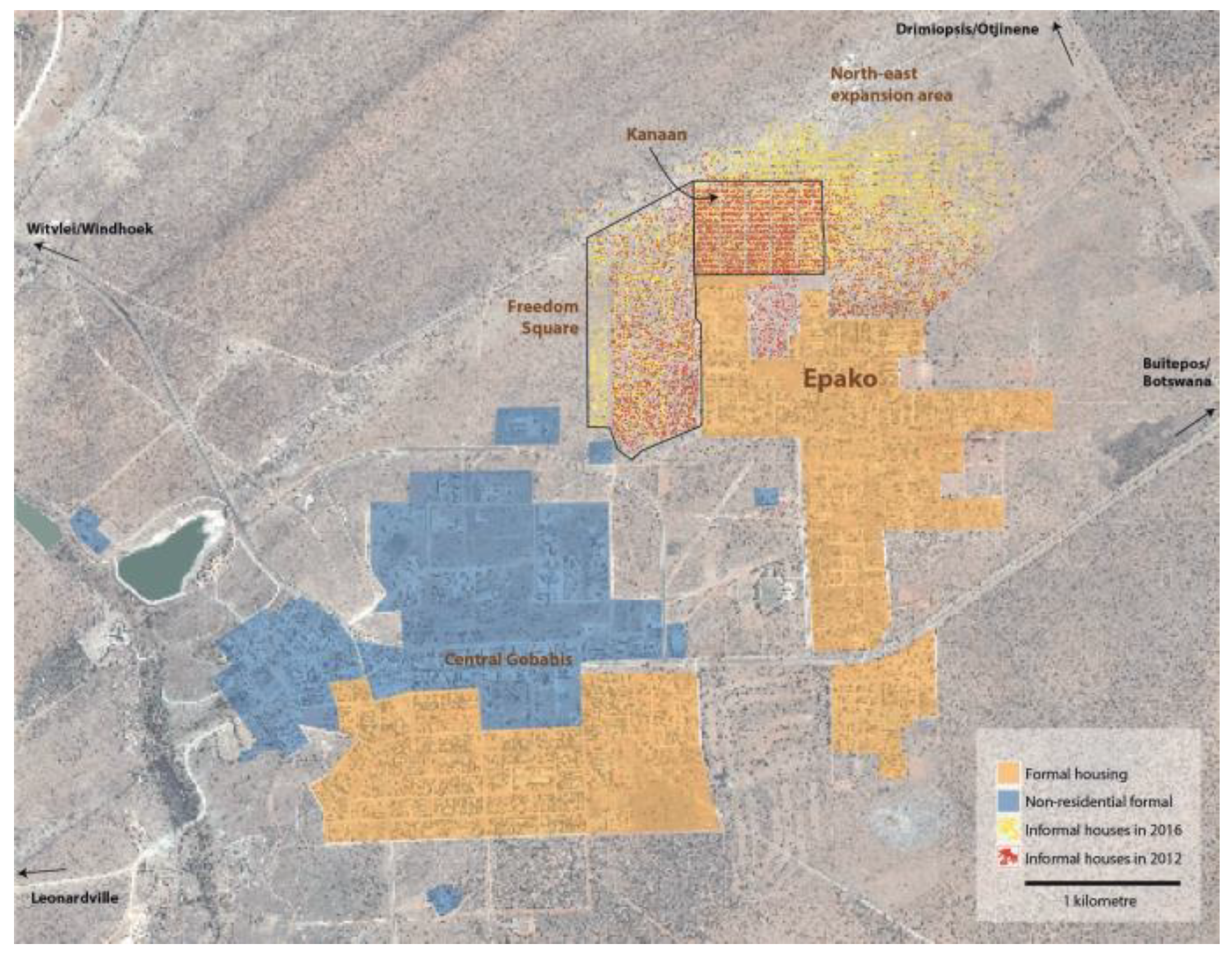

Gobabis, the capital of the Omaheke region of Namibia, is about 200 km from Windhoek. Around 19,000 people reside in Gobabis [

20], and according to the settlement enumeration called Community Land Information Program (CLIP) conducted in 2012, 47% of this population lived in its four informal settlements. When the council of Gobabis planned to establish a designed formal township in the location of Freedom Square, it had planned to relocate the inhabitants; however, due to the large size of the settlement (

Figure 1) and possibly not to lose political ground, the council eventually surrendered to the inhabitants’ demands supported by NHAG and The Shack Dwellers Federation of Namibia (SDFN) and agreed to sell the land to them at a subsidized price. This was the start for the upgrading process.

It aimed to secure land tenure and started in 2012 with the enumeration of all four informal settlements in Gobabis. The inhabitants’ direct involvement in the enumeration was followed by them identifying and prioritizing their needs to formalize their settlements. In Freedom Square, tenure security was identified as a means to achieve all the other services, such as water and sanitation. Few selected inhabitants also travelled abroad as part of the learning exchanges within the international network Slum Dwellers International (SDI) of which SDFN is part. They gathered knowledge of participatory processes and learned about re-blocking settlements in particular. They implemented the re-blocking of their settlement with NUST students during the next phase in 2014. As things proceeded, the inhabitants moved into their re-blocked plots and provided physical labor to excavate trenches for service line installation. At this point, the Ministry of Land Reform (MLR) equipped the inhabitants with training and informed them about their tenure security options, to implement the FLTA. Along the line, the inhabitants were assisted to form management committees within each administrative block. A final survey by the government, with the inhabitants’ help, provided the updated land occupancy data, and afterwards, the inhabitants were handed over the certificates of tenure and a photocopy of the land deed in early 2021.

Freedom Square (

Figure 2) consists now of nine blocks, with 12-meter-wide roads reaching each block and plots within. Although all households now have access to service connections, not all households have been able to afford the machines and equipment required for installation. Lack of trust in the municipality billing system has led the inhabitants to decide on costly prepaid water meters. Initially purchased from NHAG and now the municipality, the inhabitants face maintenance issues with the meters and often cannot afford to repair or re-purchase. Therefore, water is not yet readily available to all. Additionally, very few households have been able to afford to build toilets and as there is still a lack of electricity, and limited street lights, women’s struggles with lack of safety persist. Therefore, women go to the fields in groups to relieve themselves. It is also apparent that the government is struggling to provide all basic infrastructure and services, and the previously informal inhabitants are yet to grasp the service charges of being formalized.

5.2. Motivations to Participate

The women of Freedom Square had certain initial goals that motivated them to participate in this process, which range from tangible to intangible. At the inception, SDFN members and NHAG motivated women to participate. Young women were also encouraged to use their time to help the community. During the semi-structured interviews, the women also mentioned that the fear of eviction was a key motivation. As they moved forward, they identified that having land tenure is the mean to receiving their primary needs, such as water and toilets. During an interview for this research with Tapiwa Maruza from NHAG, speaking of the involvement of single mother inhabitants, she mentioned, ‘‘I think women, especially women-headed households, are probably in need more than the average household. So they are more vulnerable. Moreover, because these women don‘t have access to other opportunities that perhaps are accessible to most, they become more involved.”

Although women‘s basic needs overpower everything else in an informal setting, during the interviews, the participants mentioned the intangible things that motivated them to participate in this process. The joy of planning with their peers and professionals and valuing their opinions motivated them to continue being in the process. For some, the image of a livable community acted as inspiration, while others enjoyed the group interactions and kept returning for more. Even though the process had not yielded any tangible results for the first four years, the women being motivated for these various reasons gave momentum to this process to initiate and continue.

Moreover, Freedom Square‘s women‘s economic activities consist of informal work. This refrains them from getting a loan to develop their housing. They can only fulfil their housing goals by participating in this process. As Tapiwa Maruza from NHAG further mentioned during her interview for this research, ‘‘So if you look, for example, at informal economy, it‘s mainly women. And so already you can see that there‘s a big chunk of people who are working. The biggest chunk of people who are working informally are the same people who can benefit from this process, because they don‘t have pay slips. They don‘t have all of the things that would make it possible for them to get a loan at the bank or for them to join any other housing process like NHE and all of that. So I think because women are vulnerable more than men, they participate more because they see this as a final opportunity for them to actually get housing„

During the semi-structured interviews, many participating women from Freedom Square mentioned that they had no formal commitment to any job. Therefore, they had the flexibility to manage their schedules and be present in the community gatherings. The involved stakeholders also provided lunch to the participants. To motivate the community, especially women, to attend, they held the meetings within the community‘s reach, under a large tree, so that women did not have to travel far from their households and could attend. Most women responsible for looking after their children could leave them with the neighbor for the time being and attend meetings. Bringing the discussion to their households motivated them to attend the meetings.

During the focus group discussion, when presented with the participation motivations from interviews and asked to select their three most important goals, it was visible that everyone selected their needs for basic services as their highest priority. The results of the validated data are summarized in

Table 1.

Identification of these goals assist in analyzing two things. One, how far the goals have been achieved and two, what is the effect of women’s participation in the upgraded settlement, which is discussed in detail in section 5.5.

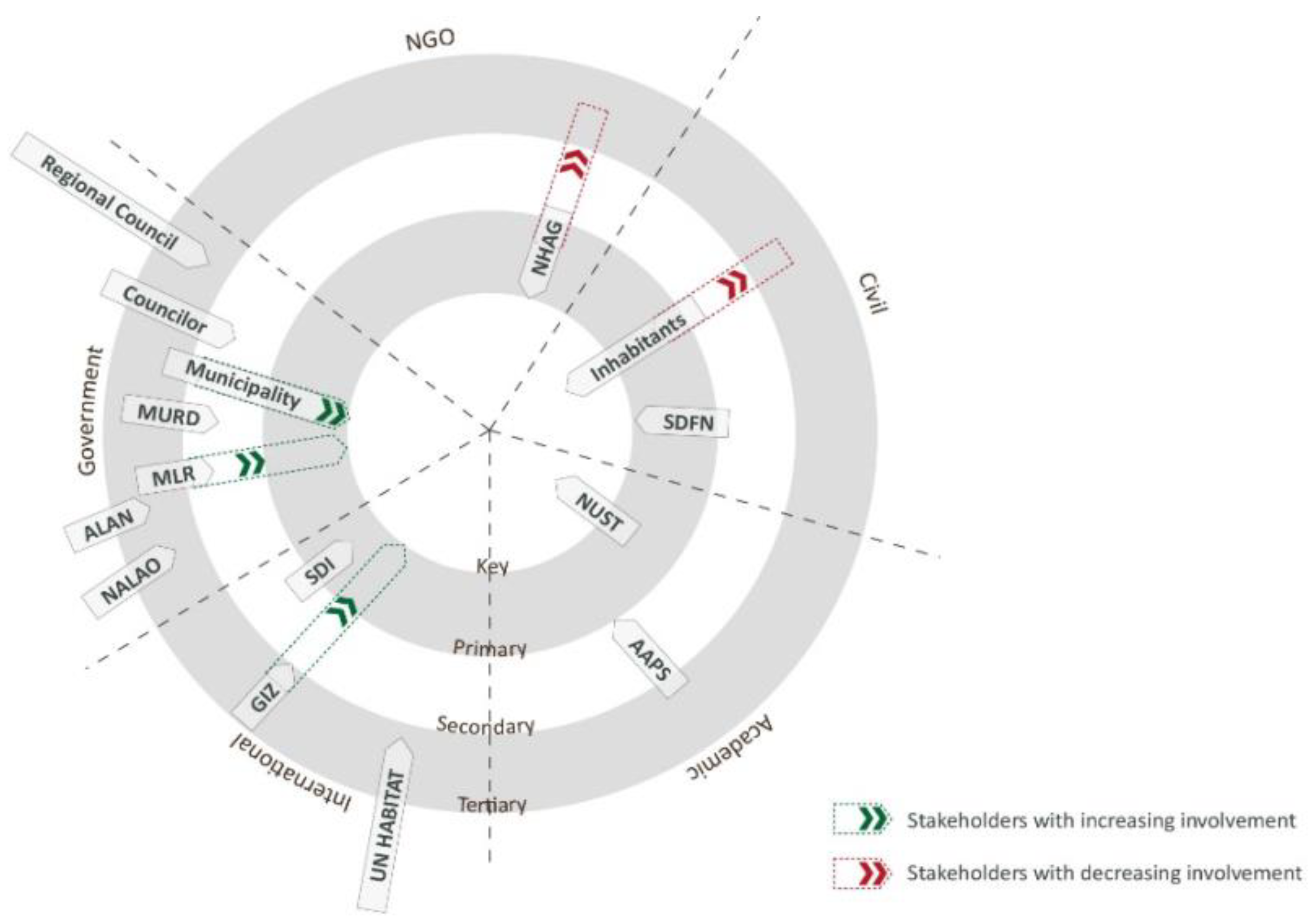

5.3. Stakeholders’ Influence on the Participation by Women

The dynamics of stakeholders changed according to their roles throughout the upgrading process. Initially, the key stakeholders were NHAG and SDFN, who conducted the settlement enumeration according to their contract with the Gobabis Municipality. At that time and immediately afterwards, the community was more involved and made key decisions regarding upgrading and planning the re-blocked settlement, along with the town planning students of NUST. The next phase proceeded as the Ministry of Urban and Rural Development (MURD) allocated funds for service installation and the inhabitants, along with NHAG and SDFN provided physical labor to relocate themselves to their new plots and excavate trenches. Enumeration data was updated and the Social Tenure Doman Model (STDM) by the Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) was followed to register data and selected inhabitants were recruited to assist. The next steps included the participation of MLR and the Municipality as primary stakeholders, which excluded the direct participation of NHAG and SDFN. The impact of this changing relationship between stakeholders influenced the outputs of inhabitants and especially women‘s participation in the process.

Figure 3 visualizes this changing relationship of stakeholders.

While achieving the earlier milestones, the women inhabitants were directly involved in every step; thus, the outputs were positive and left little room for complaints, as the direct involvement created a sense of responsibility within the inhabitants. They felt valued and liable for their own development alongside the local authorities and donors. During an interview for this research, Tapiwa Maruza from NHAG mentioned from her experiences in Gobabis, “Most of the time, especially when you look at these communities who are impoverished and who do not have the resources to improve their situation, and what ends up happening is that people end up losing hope. So I think a participatory process actually encourages them and that it empowers them to say, okay, I actually can do something and make decisions and be an active stakeholder in my own development.” However, later in the phase, when government involvement increased, Delgado et al. 2020 [

12] mentioned that they treated the community as beneficiaries instead of partners in development. The active stakeholders of the later phase focused more on mass service provision and less on community participation, resulting in complaints and raised inhabitants’ expectations. This impacted the sense of responsibility of the inhabitants and led them to the backseat where they could make the authorities liable for all the decisions and developments. This has directly impacted on the management committee. One interviewed committee leader, while discussing the lack of community efforts and responses mentioned her frustration by saying, “But the things in the beginning were very good, we finished together, the trenches, we did it together. Every time, there is a meeting, they were there, but I don‘t know what happened with the people.”

The second impact of changing stakeholder relationships directly affected the women participants. According to the interviewed experts, women have been excluded along the way and their involvement decreased towards the end of the upgrading process. As was visible during the progression of the upgrading process, the involvement of women decreased near the end. There are multiple reasons behind this decreasing involvement of women, one of which is the change in stakeholder relationship. As NHAG and SDFN were less directly involved and the government organizations led the process, more men became dominant. This might have resulted from men‘s political ambitions rising due to the opportunities of networking with the government organizations, or the absence of organizations inviting women and led by women. Tapiwa Maruza from NHAG confirmed this assumption, stating, ‘‘In terms of leadership, it was very interesting to see more female leadership and females driving the process at the beginning. But then towards the end, when things were becoming a lot more formal, it became very male, more men representing the process than before.”

5.4. Challenges of Participation for Women

During the nine years long (2012-2021) upgrading process, women from Freedom Square joined and withdrew from time to time, to balance their other responsibilities. Eva (fictitious name), 35, a married women inhabitant was living in Freedom Square with her husband, mother-in-law and three children. Her involvement in the upgrading process started in 2014 with attending the planning studios with NUST students after the community achieved the first milestone. She wanted her family to own a plot and did not have a formal income back then, which encouraged and facilitated her participation. During the semi-structured interview, Eva mentioned that, in the beginning, there was no street in the settlement. So it was difficult for them to reach their place when they came with a taxi if they had a lot of things to carry. Her husband was working outside the settlement, so he could not participate in the process even if he wanted to. On the days of community meetings, she would wake up earlier than usual to make food for the family, feed her children, and leave them with her mother-in-law so she could go attend the meetings. After a period of unpaid participation and a lack of visible results, her husband started restraining her participation. She argued and continued until they received joint land tenure as a married couple. She also mentioned during the interview, ‘‘yes, it’s also easier to stop because of the complaints (from her family). Also, the work was in the hot sun and all those things, but we went on until the end.” Although not satisfied that they have to pay for the land and services even though they provided physical labor during service connection installation phase, Eva is still happy to be able to take a taxi to her doorstep when needed.

All of the interviewed participants shared similar stories with varied level of challenges faced during their participation. During the focus group discussion for data validation, the participating women were presented with the challenges identified from the semi-structured interviews and were asked to choose three of the most crucial challenges they faced. Lack of payment for participation and time consuming particiaptory process were chosen as the main challenges women, especially single mothers, faced during the process. From unhelpful family members to non-supportive husbands forbidding their wives to attend the processes, the women also faced restraints within their families.

Table 2 summarizes the challenges identified from their responses.

Some women stopped participating, while others continued with support from their female friends and neighbors. During an interview with Dr. Anna Muller from NHAG she mentioned, ‘‘we had one member that was so strong and fluent in understanding and explaining the steps that she ended up in Johannesburg at the presentation of the governor to make it work. And her husband blocked her from further involvement. She was not allowed to do it.” Additionally, another major challenge identified in the workshop and by expert interview (Anna Muller) was alcoholism in the family. This situation often restricted women from being able to participate.

It was long before the upgrading process started showing tangible results. This is also one major reason women kept slowly falling out of the process. A lot of the participating women got pregnant, stepped away and came back when possible- as the process was strenuous and required physical labor. This also prohibited elderly people from participating. Additionally, since this process required reading maps, speaking up and voicing their needs, illiterate and shy women often stayed away for fear of embarrassment.

Women also faced challenges due to their economic condition during the participation since the upgrading process did not provide any form of income. Instead, it involved saving from their current income to pay for land, services, and a house. Spending time on something unpaid also made them face retribution from their families, who were questioning their motives and choices to participate. Single mothers even had to hire help to excavate trenches for service connections for them during the upgrading process. Earning and taking care of houses and their children did not leave them any spare time or energy to participate in the process. Since this was a mandatory step that the community agreed to partake in, the single mothers were forced to spend money which other inhabitants did not need to. Several women participants left the process to seek work, as they were aware of the upcoming costs. They traveled to nearby areas, often to Windhoek, in search of domestic work. Some interviewees mentioned that participating in the upgrading process did not provide any income, and they had to prioritize building a house when the opportunity arose. The lack of job opportunities in Gobabis impacted their overall participation. Many married or cohabiting women did not have a formal income and depended on their partner’s income and economic decisions. The social norm of the earning member controlling the ‘Head of Household’, in some cases, prohibited women from participating in the process.

5.5. Output of Participation

It is possible that at the initial phase of the upgrading process land tenure and the necessity of water were chosen as the highest priorities because the majority of the participants were women from the settlements. Their suffering due to the lack of water connections made this their priority. This resulted in water connections in all houses, along with sanitary connections. Planning processes acknowledging women’s point of view focuses on the household needs of the inhabitants spending more time inside the settlements. The block planning of Freedom Square has agricultural plots for shared farming, business plots for shared informal businesses, and open spaces for playing and gathering. This could be the result of women’s input, where they wanted to have gathering spaces and play areas close to their households and agricultural and business plots within the blocks so they could contribute or sell informally without having to go further away from their households. This plan to decentralize common facilities and put them within the range of each resident supports the women staying inside the settlement but performing different household duties.

Although the process was driven by women, it seems like ownership at the end of the process was often transferred to men. Women often chose the husband to be the ‘head of Household’ thereby making him the plot owner. During his interview for this research, Robson Mazambani from GIZ mentioned that, during the final ‘Head of Household’ survey by GIZ, the heads were decided by several factors- the owner of the existing structure, earning member or simply, socially hierarchical head. Participating women chose their husbands as ‘Head of Households’ and handed off land ownership because it was a socially acceptable decision. Nevertheless, single mothers own their structures themselves and couples married by law (contrary to the couples married in the community) also hold joint tenures, as advised by the stakeholders’ active at that time. In cases of married in the community or cohabiting relationships, it is single ownership, leaving the other partner with no security of tenure.

Moreover, it is notable that when land ownership was becoming more of a possibility during the upgrading process, men started involving themselves more. During the semi-structured interviews with Freedom Square inhabitants, three interviews were conducted with men inhabitants, in addition to the 17 women inhabitants. Whereas men indicated their concerns with regards to payments for the land, women stated more about the issues of lack of services.

Many residents are prioritizing building their homes over paying for the land due to a lack of job opportunities or unclear information about payment terms. However, until the payments are completed, they do not receive their original land tenure certificates, and this raises concerns about inheritance, specifically whether their children will be able to safely inherit the land. This was highlighted by women residents during semi-structured interviews.

The women feel safer because they do not have to move around with their children and have land to settle down. This primary assurance helps them move forward in daily life. They can extend their shacks and run an informal business from within. Previously, businesses were often victims of vandalism, but they are not anymore. Ownership has opened certain possibilities they can now build upon if they want to.

5.6. Impact of Participation

Previously shy to speak in gatherings, let alone make decisions, the women of Freedom Square have built immense leadership capacities by participating as a group. Freedom Square has management committees in each block, where the elected leaders are gender-balanced and representative of each tribe. Some participant women were elected as community leaders and some others are in important roles within SDFN. However, it is also notable that this percentage is not proportionate to the number of participating women.

In discussions with the community leaders during the data collection, they mentioned their frustration regarding the current management situation. Since the committee leaders have no authority to change their settlements’ conditions, their leadership has become a symbol of tokenism to themselves and the rest of the inhabitants. Nonetheless, existing women leaders feel more accountable for their blocks due to their long-term direct involvement in this process and at least one woman per block is active in maintaining communication between inhabitants and local authority. The interviewed women, who were not committee leaders, mentioned they feel more comfortable sharing their issues regarding lack of services to a women committee leader.

It was noticeable during the site visit and interview in Gobabis that women are less visible in governance with actual authority. Even though they are part of the management committees, the social norms and stigmas surrounding the gender of leadership persist. During the interview, a group of male inhabitants of Freedom Square also attended to discuss the possibilities of help regarding not having to pay for the land. It was visible that men were now leading the decisions of inhabitants, and the rest of the inhabitants were following this because it also served their needs since they barely had any money left to pay for land after paying for the necessary services and saving for building a house. Robson Mazambani also highlighted that it is worth looking at whether women are making decisions in Freedom Square anymore. However, during the brief interaction with the community while data collection, it was not visible as such. Women seemed hopeless about the situation, while men advocated for not paying.

During the upgrading process, other stakeholders informed the inhabitants that they could get recommendation letters for their participation, which might lead to more work opportunities. The inhabitants of Freedom Square, being the pilot in implementing the FLTA, continue to help other communities by sharing their experiences. Committee leaders, mostly women, are often invited by NHAG and SDFN to travel to other settlements. Some inhabitants also had temporary jobs with the municipality during the re-enumeration process, and some received jobs in NGOs and international organizations after they participated in the upgrading. However, this number is quite low.

By sharing opinions, participating in public gatherings, and public speaking to share knowledge, the women of Freedom Square have built or increased their social and technical capacities. They can negotiate with the municipalities and committee leaders for their needs and voice their frustrations. However, their visibility is significantly lower now than at the beginning of this process. The participating women are not visible as final decision makers or politicians; that arena is still navigated by men who stepped in later in the process that women had started. Additionally, according to Delgado et al. [

4], the participants have been empowered with the technical skills they acquired, social organizing, engagement with authorities, and understanding of urban development processes- which is a valuable result of every co-creation process and could have been put to better use in Freedom Square for the longer-term betterment of the inhabitants.

During interviews, the women inhabitants mentioned not completely understanding the costs associated with their development and role. In the case of Freedom Square, although NHAG and SDFN had disseminated information in earlier stages in detail, but often due to a lack of time and required emergency actions, the pre-process information dissemination failed to continue throughout the process. During the relocation and service installation, initially, active stakeholders were less concerned with information dissemination and more with distributing labor. The participating women inhabitants did not completely understand the cost of being formalized and that the urban area’s formal inhabitants pay lifelong service charges for each service they receive, such as water, waste management, or electricity.

6. Discussion

The research findings confirm that women were key to initiate this process and led the process in the beginning. Therefore, women’s engagement was not a by-product of the process but drove it. However, the findings also indicates that their pattern of involvement changed due to several factors as the tenure certificates were about to be received.

Stakeholders involved in the upgrading process directly influenced women’s engagement over the process’s lifespan. NHAG and SDFN created an environment for women to engage and lead; therefore, their participation advanced the process and benefited them personally. However, the government’s centralized approach reduced women’s active engagement after relocating to their plots. Additionally, the increased involvement of men just before and after the relocation further reduced women’s participation. This trend appears common in processes that lack a gender mainstreaming agenda and gender sensitive actions.

The findings also indicate that the participating women faced certain social and economic challenges within their households and settlements. These challenges often went unnoticed for two reasons. First, the lack of a gender mainstreaming agenda did not prompt other stakeholders to address the challenges faced by the women driving the process. Second, the upgrading process relied heavily on the time and labor of women, which may have led stakeholders to encourage their participation without acknowledging their additional burdens. The women’s economic struggles were also overlooked due to the absence of a holistic plan for the economic development of the women inhabitants, most of whom lacked formal income or any income opportunities. While NHAG and SDFN introduced the women to savings programs and the possibility of loans for building permanent houses, they did not address the lack of income.

The research shows that the primary motivation for women was to settle in their lands, which has been achieved by land occupation. However, their need for services has only been partially fulfilled, and since these services entail ongoing costs, women without economic solvency, especially single mothers, cannot afford them. Moreover, original land tenure certificates have not been provided to the inhabitants due to remaining land payment instalments. Currently, the inhabitants occupy the land with photocopies of the certificates. Not having an original formal document might hinder them from enjoying the full benefits of land ownership. The women inhabitants of Freedom Square are largely unaware of these legal issues due to a lack of legal knowledge or information.

Finally, the findings provide evidence that the women participating in Freedom Square who have been elected as leaders of block management committees have no actual power to ensure proper management. As a result, this leadership position burdens them instead of empowering them. Notably, women leading the upgrading process did not have the opportunity to be part of the governance later. The local authority is predominantly composed of men in decision-making positions. The conclusion for this research is drawn from the synthesis of these findings.

According to discussion at the beginning of this article, in Namibia, women’s civil status had been a criterion in determining their status and land ownership. As also mentioned, FLTA does not set any criteria for choosing the ‘Head of Households’, leaving this decision to the applying family. Social norms heavily impact these decisions, which help strengthen its connection with the traditional communal laws. The assumptions of the consequences of the lack of explanation regarding terminologies such as the ‘Head of Household’ are visible in the Freedom Square process, where even the non-participating or uninterested male participants own land. The lack of direction on the situation after any separation makes it hard to assume the future situation of the women inhabitants who actively engaged in the process to make it happen. Such situations require clear descriptions of terms and lawmakers’ farsighted decision-making.

Additionally, the findings highlight the lengthy process and women dropping out due to various challenges. Women’s biological needs and social responsibilities are major considerations when designing activities for women. This reinforces the importance of gender mainstreaming with evidence from the case study. In a gender mainstreamed system, the necessity of the participating women would have been weighed along with the necessities of the process itself, thus creating a balanced output and having a more positive impact on the participating women than it has now.

7. Conclusion

Analyzing the case of Freedom Square reveals that for women to be included in designed spaces, they must participate in the process and voice their needs. The urban planning and development standards are developed with average men’s standards over time and often fail to be inclusive towards the needs of others who do not identify as such, physically or socially. Women, blending into the ‘others’ category, are excluded from decisions and planning, and the outcome often does not suit their needs. Alternatively, in some cases, women are categorized as secondary users of the space with certain facilities provided targeting them, again from the point of view of men, most of the time without consultation. Relaying the previously shared examples of walking several miles daily for water or relieving themselves in open spaces- women’s active engagement ensures a better outcome by avoiding these unfortunate incidents and making their lives easier. Unfortunately for women, in a society with a persisting gender gap, the change often happens when they advocate for it themselves. Although this overburdens the pioneers of the process, hopefully, in a better context in the future, inclusivity regarding basic services will not need to be ensured only through active participation.

However, on a positive note, the process also translates into a bottom-up planning processes for creating inclusive spaces. Unlike top-down planning, where the authorities decide the needs of communities, women residing in those communities have more opportunities to contribute as users of bottom-up planning processes. However, for this process to follow through, it is important that the women’s needs are not only conveyed but fulfilled and the results are evaluated and monitored. As seen in the case study, the lack of monitoring in Freedom Square has resulted in the women not receiving full participation benefits. This also connects their participation to Arnstein’s [

21] ladder, and the research of this case of Freedom Square indicates that the participating women have not been able to reach the final steps of the ladder. The post-upgrading situation indicates that the citizens, or in this case, the inhabitants, do not have delegated power or have not achieved citizen control in their true sense. They had been in partnership with the stakeholders during the upgrading process, but the current situation does not indicate they are in partnership anymore; it puts them back on the receiving end of services they fail to afford.

Annan-Aggrey, Bandauko and Arku [

22] highlighted multi-stakeholder engage ment in development processes as an opportunity to create inclusive cities in the African context. However, this case study research can add to such multi-stakeholder engagement recommendations, highlighting the necessity of common goals among stakeholders. The lack of a common framework among stakeholders might lead to the exclusion of certain active groups from the community. Gender mainstreaming, for example, depends on conducting a process by inviting all genders and allowing the inhabitants to understand the necessity of mainstreaming. If not understood, the challenges women face in their households during their participation will continue to burden them. In between social norms, practices, and inclusive planning processes- the inhabitants, regardless of their gender, need to acknowledge the necessity and reasoning of these actions so they can accommodate them within their lives. When provided the much-required support from their households, women can continue contributing in various ways, especially in creating their settlements. This calls for door-to-door advocacy, highlighting the challenges women face when they participate in something in addition to their social responsibilities and how reducing these challenges goes a long way in creating inclusive cities. The research concludes by presenting recommendations based on the analysis of Freedom Square.

7.1. Policy Recommendations

According to the discussion in the previous section, the Flexible Land Tenure Act shall take gender mainstreaming into consideration and clarify gender terminologies in terms of land ownership. This will separate the law from being attached to women’s civil status.

Additionally, bottom-up development policies must acknowledge the term ‘inclusivity’. This will prevent women’s needs from being overlooked if they do not physically involve themselves throughout the process.

Finally, the decentralised development policies shall clearly be implemented so that political parties in power do not override the local authorities and hamper an ongoing development process.

7.2. Development Process Recommendations

Inclusive development processes must be assessed promptly. Strategic planning of actions with periodical assessment and post-process monitoring and evaluation is required to successfully conduct an inclusive process and also for the process to make a lasting impact, thus localising a sustainable goal. Criteria must be set according to the context for each process to be assessed midway and monitored later. For integrated processes working towards localising multiple goals, the assessment criteria or indicators must be set as such, covering all the targets.

Also, for participatory processes, the local authorities play a crucial role in continuing the interaction with the community. Thus, sharing responsibilities with the community and, in turn, empowering them will help the community to move forward and take more responsibility and control over their development. Certain powers need to be handed over to the community post bottom-up development process, utilising the capacity developed by the community during the process and relieving certain responsibilities of the local authorities, which, in most cases, are overburdened.

7.3. Social Awareness Recommendations

Gender mainstreaming requires policies and social awareness to establish its importance to the participants of any process. Stakeholders of the process play a crucial role in raising awareness in the participating community. In addition to their advocacy for participation, they can map out the possible future benefits of gender mainstreaming and how it requires cooperation that should start from the household scale. It is also important that these awareness-raising actions are shaped according to the community’s social norms.

Finally, the research concludes by stating that, for women to be included in processes without having to advocate for case by case, a culture of inclusiveness needs to be raised from within the house. Inclusive decision-making regarding everyday decisions, considering the needs of all family members, can create a firm root for the community to conduct inclusive processes in their neighbourhood.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A., J.K., A.L. and M.S.; methodology, T.A., A.L. and M.S.; software, T.A.; validation, T.A. and J.K.; formal analysis, T.A., A.L. and M.S.; resources, A.L.; data curation, T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.; writing—review and editing, T.A., J.K., A.L. and M.S.; visualization, T.A.; supervision, A.L. and M.S.; project administration, A.L., M.S.; funding acquisition, A.L. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted under the umbrella of the SDGs GoGlocal! project as a trilateral partnership between the University of Stuttgart, Ain Shams University and Namibia University of Science and Technology, co-funded by German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The APC was funded by DFG research funding and University of Stuttgart, Institute of Urban Planning and Design.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to Namibia Housing Action Group (NHAG), Slum Dwellers Federation of Namibia (SDFN), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the inhabitants of Freedom Square for their support in fieldwork in Namibia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Expert interview questions (Sample):

1. In your experience, what has motivated women to participate in the land tenure securing process of Freedom Square, Gobabis?

2. In your experience, what kind of socio-economic challenges women in Gobabis has faced that has an impact on their ability to secure land tenure there?

3. Also, what are the setbacks that affect them during the participatory planning process that hinder their active participation throughout the process? (Example: as married, single, widowed women)

4. In your knowledge, how far has women been involved during the land tenure securing process in Freedom Square, Gobabis?

5. How has participation in the land tenure securing process positively mitigated the social challenges women face in Gobabis?

6. How would you evaluate gender- sensitivity of the outcomes of the land tenure securing process?

Appendix B

Inhabitant interview questions (Sample):

Conducted in English through an Interpreter

1. What is her name?

2. How old is she?

3. Who does she live with, like her family?

4. Do you have children?

5. And who has the land?

6. And they are from Gobabis? Like from when?

7. Do they have land anywhere else?

8. And what did they do when they came here in 1998?

9. What did they do?

10. And who paid for it?

11. Now who is earning?

12. Are they paying for the land?

13. Do they have water or other services?

14. Why don’t they apply for water?

15. So when the land process started, who informed her?

16. So when was this?

17. Okay, so they came and told her what?

18. And who were in the committees?

19. Deena is here?

20. She was active?

21. Was she part of the process?

22. Was the new area far from where she was living?

23. Was anyone else in her family also doing this work?

24. How long were they involved in the process?

25. Beginning of what?

26. So it was 2015 and afterwards?

27. So who would she leave her kids with when she went to the process?

28. Did she know from before that they had to pay for the land?

29. How did she feel when she found out?

30. She asked who?

31. And what did they say?

32. And what happens if they cannot pay? Do their children pay?

33. Do they give you a receipt if you pay?

34. So what is her next plan with her house?

35. And is she part of any savings group?

36. What does she mean by that?

37. Was it Shack Dwellers or other groups?

38. Did she also lose her money?

39. For how long she saved?

40. Are there any committees in her block?

41. Are shack dwellers members the same as committee members?

42. So they don’t trust them anymore?

43. So no one of the seven people are working at the moment?

44. What does she want them to do?

45. What does she want the committee to do?

46. She goes outside for the toilet?

47. Is it safe?

48. But there were community toilets before?

49. Has having the land made her situation better than before?

50. Why does she think there were more women participating in the process?

Appendix C

Interview analysis codes:

Upgrading process timeline

Planning with community

Executing with community

Maintaining land & services

Planned settlement

Basic services and infrastructure

Payments of land and services

Management committees

Flexible Land Tenure Act

Initiating settlement

Planning with community

Executing with community

Participation motivation

Participation outcome

Perception of participation

Challenges of participation

Challenges of services

Economic challenges

Financial activities

Savings groups

Government stakeholders

Civil society stakeholders

Shack Dwellers Federation Namibia

NGO stakeholders

Private sector stakeholders

International stakeholders

Academic sector stakeholders

Stakeholder relationships

Civil status

Land ownership

Leadership

Social role

Gender perspective

References

- Weber, B. and Mendelsohn, J. (2017) Informal settlements in Namibia: their nature and growth: exploring ways to make Namibian urban development more socially just and inclusive. Windhoek, Namibia: Development Workshop Namibia.

- UN-Habitat (2018). Adequate housing and slum upgrading. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/06/indicator_11.1.1_training_module_adequate_housing_and_slum_upgrading.pdf. (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- United Nations (UN) (2015) Universal declaration of human rights (UDHR). Available at: https://www.un.org/en/udhrbook/pdf/udhr_booklet_en_web.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2024). .

- Chigbu, U.E. and Enemark, S. (2022) ‘Land governance and gender in support of the Global Agenda 2030’. Land governance and gender: the tenure-gender nexus in land management and land policy, pp. 35–50. 1st edn. UK: CABI. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, J. and Meurers, D. (2015) The Land Delivery Process in Namibia A legal analysis of the different stages from possession to freehold title. GIZ. Available at: http://the-eis.com/elibrary/sites/default/files/downloads/literature/The%20land%20delivery%20process%20in%20Namibia.pdf. (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- United Nations (UN) (2017) New urban agenda. Available at: https://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda/. (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- World Economic Forum. (2024) Global gender gap report 2024. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/publications/. (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Shack Dwellers Federation of Namibia (SDFN) (2009). Community Land Information Program (Clip): Profile of informal settlements in Namibia. Available at: https://sdinet.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/NAMclip_-1.pdf. (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Office of the Special Advisor on Gender Issues and Advancement of Women (OSAGI) (2001). Gender mainstreaming: strategy for promoting gender equality. Available at: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/pdf/factsheet1.pdf. (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- UN-Habitat, GIZ and Gender CC (2015). Gender and Urban Climate Policy Gender-Sensitive Policies Make a Difference. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/gender-and-urban-climate-policy. (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Namibia Housing Action Group (NHAG) & Shack Dwellers Federation of Namibia (SDFN) (2017). Gobabis informal settlement upgrading Freedom Square, Gobabis. Available at: https://shackdwellersnamibia.com/assets/img/other%20reports/informal%20settlement%20upgrading.pdf. (accessed on 17 Sep 2024).

- Delgado, G.; et al. (2020) ‘Co-producing land for housing through informal settlement upgrading: lessons from a Namibian municipality’, Environment and Urbanization, 32(1), pp. 175–194. [CrossRef]

- Orkpeh, A.K. and Adedire, F.M. (2024) ‘African urban peripheries and informal development: A review of challenges and sustainable approaches to inclusive cities. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography, 78, 40–53. [CrossRef]

- UN- Habitat (2022). GPP: UN-HABITAT policy and plan for gender equality and the rights of women in urban development and human settlements. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/11/gpp_draft_6.pdf. (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Chigbu, U. , Paradza, G. and Dachaga, W. (2019) ‘Differentiations in women’s land tenure experiences: Implications for women’s land access and tenure security in sub-Saharan Africa’, Land, 8(2), p. 22. [CrossRef]

- Alden Wily, L. (2012) Customary Land Tenure in the Modern World Rights to Resources in Crisis: Reviewing the Fate of Customary Tenure in Africa. Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI).

- Werner, W. (2008) ‘Protection for women in Namibia’s Communal Land Reform Act: is it working?’ Windhoek, Namibia: Land, Environment and Development Project, Legal Assistance Centre.

- Chigbu, U.E. (2020) ‘Negotiating land rights to redress land wrongs: women in Africa’s land reforms’, Rethinking land reform in Africa new ideas, opportunities and challenges, pp. 156–167.

- Ministry of Land Reform (MLR) (2016). Guide to Namibia’s Flexible Land Tenure Act, 2012. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the Land, Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre (LAC).

- Namibia 2011 population and housing census main report (2011). Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA). Available at: https://cms.my.na/assets/documents/p19dmn58guram30ttun89rdrp1.pdf. (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Arnstein, S. (1969) ‘A ladder of community participation’. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35, 216-224. [CrossRef]

- Annan-Aggrey, E. , Bandauko, E. and Arku, G. (2021) ‘Localizing the Sustainable Development Goals in Africa: implementation challenges and opportunities’, Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, pp. 4–23. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).