Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods and Results

| Dosages | Types of terfez | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Red | Black | |

| (%) | |||

| Water | 68 | 75 | 77 |

| Dry matter | 38 | 25 | 23 |

| Protein | 1,9 | 1,7 | 1,2 |

| Lipids | 1 | 1 | 0,35 |

| Sugars | 8,5 | 5,1 | 2,1 |

| Ash | 1,4 | 1,8 | 2,1 |

| (µg. g-1) | |||

| N** | 640 | 125 | 391 |

| P* | 3,46 | 1,58 | 2,54 |

| K*** | 28,9 | 28,1 | 32,8 |

| Ca*** | 25,4 | 14,9 | 146,8 |

| Mg*** | 24,4 | 20,3 | 25,6 |

| Na*** | 13,7 | 8,4 | 10,7 |

| NO3-* | 00 | 00 | 00 |

| NH4+* | 1280 | 425 | 78 |

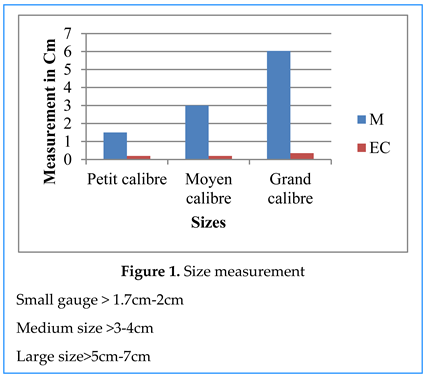

Truffe Size Measurement

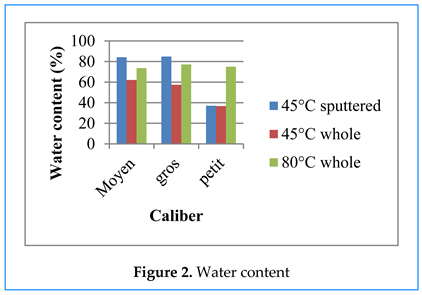

Water Content

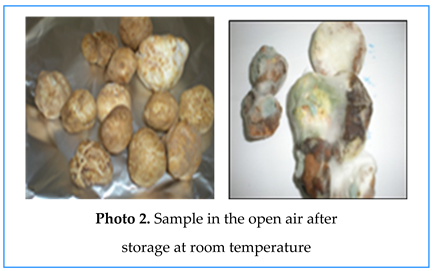

The Different Types of Preservation

- 1.

- In the open air

- 2.

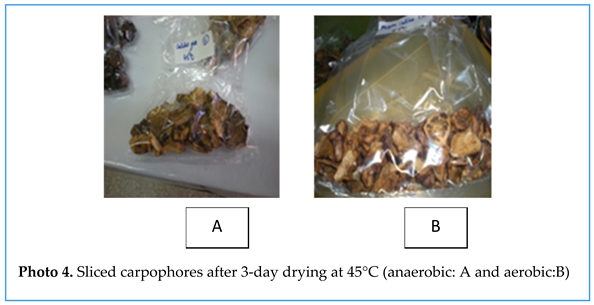

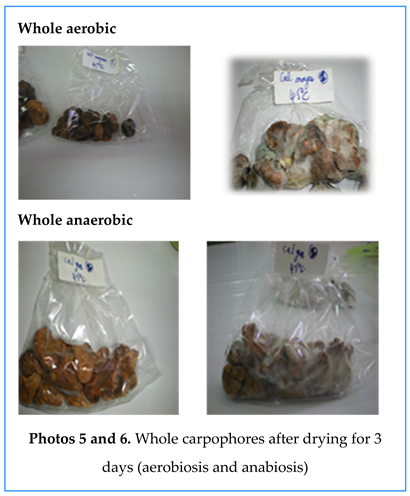

- Oven at 45°C

- 3.

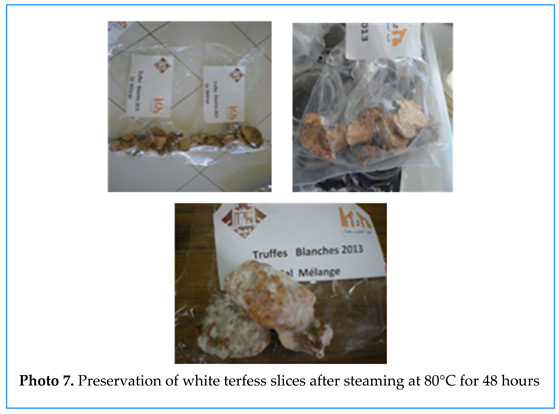

- Oven at 80°C

- 4.

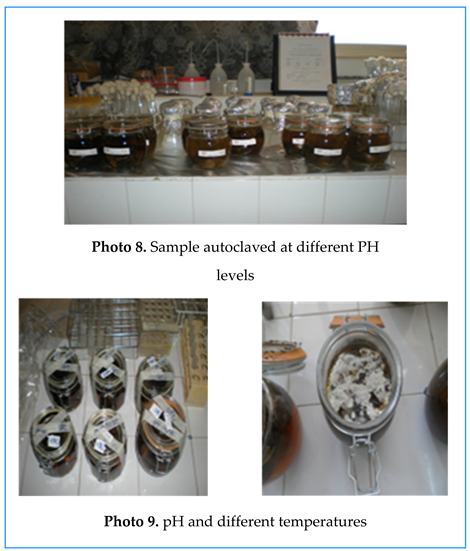

- Autoclave in aqueous media

- 5.

- NaCl + citric acid solutions

- 6.

- Freezing

- 7.

- Powder

- 8.

- Processing into jam

- 9.

- Aqueous extraction

Discussion

Conclusion

References

- Awameh and Alsheish (1978) Laboratory and field study of for kinds of truffle (Kameh) ; Terfezia and Tirmania species, for cultivation.Mushroom science (Part II).Proceedings of the Trent International Congress on the Science and Cultivation Of Edible Fungi ; France ; 507-517.

- Alsheish, (1984) Myccorhizae of annual Helianthenum speciesformed with desert.Proceedings of the sixth N.Am.Comf.On Mycorrhizae. (R. Molina ; Ed) Bend.Or ; 25-29 June.

- Dexheimer et al. (1985) Comparaison ultrastructural study of symbiotic mycorrhizal associations between Helianthemum salicifolium Terfezia Claveryi and Helianthemum salicifolium Terfezia leptoderma. Canadian Journal of botany 63.582-591.

- Fortas, Z (1990) Etude de trois espèces de terfez, caractères culturaux et cytologie du mycélium isolé et associé à Helianthemum gutattum." PhD thesis, University of Oran (Es-sénia) and INRA Clermont-Ferrand.

- Roth-Bejerano N., Livne D.,Kagan-Zur V (1990) Helianthemum-Terfezia relations in different growth media. New Phytol. 1990 ;114 :235-238.

- Fortas Z and Chevalier (1992) a Characteristics of ascospore germination of Terfezia arenaria (Moris) Trappe, collected in Algeria." Cryptogamie, Mycol. 13 : 21-9.

- Fortas Z and Chevalier (1992) b Characteristics of ascospore germination of Terfezia arenaria (Moris) Trappe, collected in Algeria." Cryptogamie, Mycol. 13 : 21-9.

- Morte A., and Honrubia, M (1994) Patent no. P9402430. Madrid.

- Khabar L (2002) Etude pluridisciplinaires des truffes du maroc et perspectives pour l'amélioration de production des (terfessde la foret de la Mamora. PhD thesis, Mohamed V-Agdal University, Rabat, Morocco.

- Zitouni (2010) Etude des associations mycorhiziennes entre quatre espèces de terfez et diverses plantes cistacées et ligneuses en conditions controlées. Magister's thesis, University of Oran Es-sénia.

- Slama et al. (2010) Biochemical composition of desert truffle Terfezia boudieri Chatin. Acta Horticulturae 853 :285-289, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, 2009.

- Slama A., Gorai, M., Fortas, Z., Boudabous, A., & Neffati, M (2012) Growth, root colonization and nutrient status of Helianthemum sessiliflorum Desf. inoculated with a desert truffles, Terfezia boudieri Chatin. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 19, 25-29. [CrossRef]

- Diez J., Manjon, J. L., & Martin, F. (2002) Molecular phylogeny of the mycorrhizal desert truffles (Terfezia and Tirmania), host specificity and edaphic tolerance, 94 pages 247-259.

- Chafi M.E.H, Fortas Z et Bensoltane A (2004) Bioclimatic survey of the terfez zones of the South West of Algeria and an essay of the inoculation of Pinus halepensis Mill. with Tirmania pinoyi.Egypt.JAppl.Sc ;19 (3) : 88-100.

- Morte A., Honrubia, M., & Gutiérrrez, A. (2008) Biotechnology and cultivation of desert truffles. In : Varma A (ed) Mycorrhiza, 467-483.

- Awameh and Alsheish (1979) Mycorrhizal synthesis between Heilanthemum ledifolium, H. salicifolium, and four species of the genera Terfezia and Tirmania using ascospores and mycelia! Cultures obtained from ascospore germination. Abstracts of 4th N. Am. Conf. on Mycorrhizae, No. 23, June 24-28, 1979. Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Awameh (1981) The response of Helianthemum salicifolium and H.ledifolium to infection by the desert truffle Terfezia boudieri. Mushroom Sci. 11 :843-853.

- Alsheish and Trappe (1983) a Desert truffles : The genus Tirmania. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 81 :83-90.

- Alsheish and Trappe (1983) b Taxonomy of Phaeangium lefebvrei, a desert truffle eaten by birds. Can. J. Bot. 61 :1919-1925.

- Chevalier G., Riousset, L., Dexheimer, J., & Dupre, C. (1984) Synthese mycorrhizae between Terfezia leptoderma Tul. And various Cistac6es. Agronomie 4 :210-211.

- Fortas Z and Chevalier (1988) Effect of growing conditions on mycorrhization of Helianthemum guttatum by three species of the genus Terfezia and Tirmania (desert truffles). 2ème congresso Internazionale Sul tartufo Spoleto, (pp. 197-203).

- Fortas (2009) Diversity of terfez (sand truffle) species from Algerian arid zones. Oran : Researchgate.

- Bratek Z, E. Jakucs, G. Szedlay (1996) Mycorrhizae between black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) and Terfezia terfezioides Mycorrhiza volume 6, pages271-274.

- Morte A., LovisoloC, and Schubert, A (2000) Effect of drought stress on growth and water relation of the mycorrhizal association Helianthemum almeriense- Terfezia claveryi. Mycorrhiza, 10, 115-119. [CrossRef]

- Slama et al. (2006) Etude taxinomique de quelques Ascomycota hypogés (Terfeziaceae) de la Tunisie méridionale. Bull. Soc. Mycol. Fr, 122 (2-3), pp. 187-195.

- Mandeel Q.A and AL-Laith, A.A (2007) Ethnomycological aspects of the desert truffle among native Bahraini and non Bahraini peoples of the Kingdom of Bahrain. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 110, 118-129. [CrossRef]

- Trappe and al. (2008) Desert Truffles of the African Kalahari : Ecology, Ethnomycology, and Taxonomy. Econ Bot (62), pp521-529.

- Honrubia M, Cano A, MolinaNiñirola C. (1992) Hypogeous fungi from Southern Spanish semiarid lands. Persoonia 14 :647-653.

- Bradai M.N., Saïdi B., Enajjar S. & Bouaïn A. (2006) The Gulf of Gabès : a spot for the Mediterranean elasmobranchs. In N. Başusta, Ç. Keskin, F. Serena, B. Seret, eds. The Proceedings of the International Workshop on Mediterranean Cartilaginous Fish with Emphasis on Southern and Eastern Mediterranean, Istanbul, 2005, Turkish Marine Research Foundation, Turkey. pp. 107–117.

- Al-Delaimy (1977) Protein and amino acid composition of truffle, Journal of the Canadian Institute of Food Science and Technology 10 ; 221-222.

- Bokhary H.A, and Bokhary M.A (1987) Chemical composition of desert truffles from Saudi Arabia. Calif Inst Sci Tech 20 :336-341.

- Ahmed AA, Mohamed MA, Hami MA (1981) Libyan truffles "Terfezia boudieri Chatin» : chemical composition and toxicity. J Food Sci 11 :927-929. [CrossRef]

- Bokhary and Parvez (1993) Chemical composition of desert truffles Terfezia claveryi. J Food Compos Anal 6 :285-293.

- Omer et al. (1994) The volatiles of desert truffle : Tirmania nivea. Plant foods for human nutrition, , 45:247- 249.

- Hussain G and Al-Ruqaie I.M (1999) Occurrence in chemical composition, and nutritional value of truffles : overview. Pakistan J Biol Sci 2 :510-514.

- Dabbour and Takuri (2002) a Protein quality of four types of edibles moushroom found in Jordan. Plant Foods Human Nutr 57 :1-11.

- Dabbour and Takuri (2002) b Protein digestibility using corrected amino acid score method (PDCAAS) of four types of mushrooms grown in Jordan. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 57 :13-24.

- Murcia et al. (2002) Antioxidant activity of edible fungi (truffles and mushrooms) : losses during industrial processing. J Food Pro 65 :1614-1622.

- Bouziani (2009) Contribution à l'étude et à la mise en valeur du potentiel truffier de la region orientale du Maroc. Thesis.Doc.Sc.Agro.Univ.Mohame 1er d’Oujda.

- Haloubi A (1988) Les plantes des terrains sales et désertiques, vues par les anciens arabes ; confrontation des données historiques avec la classificatiodes végétaux, leur état et leur répartition actuel en Proche-Orient. Doctoral thesis, Univ. Scien. Tech. Languedoc, Montpelier,p 86, p 311.

- Hannan MA, Al-Dakan AA, Aboul-Enein HY, Al-Othaimeen AA. (1989) Mutagenic and antimutagenic factor(s) extracted from a desert mushroom using different solvents. Mutagen, 4 : 111-114. [CrossRef]

- Pervez-Gilabert M, Sanchez- Felipe I, Garcia- Carmona F (2005) b Purification and partial characterization of lipoxygenase from desert truffle (Terfezia clavery i Chatin) ascocarps. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53 : 3666-3671.

- Al-Laith A.A (2010) Antioxidant components and antioxidant/antiradical activities of desert truffle (Tirmania nivea) from various Middle Eastern origins. J Food Compos Anal 23 :15-22. [CrossRef]

- Pervez Gilabert Gilabert M, SanchezFelipe I, Garcia- Carmona F. (2005) a and b Purification and partial characterization of lipoxygenase from desert truffle (Terfezia clavery i Chatin) ascocarps. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53 : 3666-3671. [CrossRef]

- Rougieux R (1963) Antibiotic and stimulant actions of the Desert truffle (Terfezia boudieri Chatin). An. Insti. Past. 105 : 315-318.

- Chellal and Lukasova (1995) Evidence for antibiotics in the two Algerien truffles Terfezia and Tirmania, 50(3) :228-9.

- Dennouni (1996) Mise en évidence des activités antibactériennes et Antifongiques chez deux espèces de Terfez d'Algérie (Tirmania nivea et Tirmania pinoyi). Magister's thesis, University of Tlemcen, 97 p.

- Mohamed Benkada M (1999) Extraction et essai d'isolement des principes antimicrobiens de Terfezia Claveryi Chat.Thèse de Magister.Univ.D'Es-Sénia Oran 81p.

- Janakat S., Al-Fakhiri S. and Sallal A.K. A (2004) A promising peptide antibiotic from Terfezia claveryi aqueous extract against Staphylococcus aureus in vitro. Physiother Res 18 :810-813. [CrossRef]

- Janakat S., Al-Fakhiri S. and Sallal A.K (2005) Evaluation of antibacterial activity of aqueous and methanolic extracts of the truffle Terfezia claveryi against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Saudi Med J 26 :952-955.

- Fortas Z and Bellahouel-Dib (2007) Extraction of bioactive substances from Algerian terfez and demonstration of their antimicrobial activity. Revue des régions arides, 1 : 280-282.

- Neggaz (2010) Tests of antibiotic properties from Tirmania pinoyi against bacteria and fungi 2eme Colloque International en Biotechnologie Bio Tech World 2010, 29-29 Avril 2010 Oran ; Algerie.

- Abdalla et al. (1979) Studies on the nutritive value of Saudi truffles and the possibility of their preservation by canning.Proc 2 nd Arab Conf.Food Sci.Technol , 2 :369-376.

- Al-Shabibi M.M.A., Toma, S.J.and Haddad, B.A (1982) Studies on Iraqi Truffles. I. Proximate Analysis and Characterization of Lipids. Canadian Institute of Food Science and Technology Journal Volume 15, Issue 3, 1982, Pages 200-202.

- Sawaya WN, Al-Shalhat A, AlSogair A, Mohammad M (1985) Chemical composition and nutritive value of truffles of Saudi Arabia. J Food Sci 50 :450-453. [CrossRef]

- Alais and Linden (1987) Biochimie Alimentaire Ed. Masson.

- Ashour R, A., M. A. Mohamed, and M. A. Hami. (1981) Mushroom science.XI.PART II.In : Proceedings of the 11th International Congress on the Cultivation of Edible Fungi. Sydney ; Australia ; pp.833-42.

- Ackerman LGJ, Vanwyk PJ, Du Plassis LM (1975) Some aspects of the composition of the Kalahari truffle or N'abba. S Afr Food Rev 2 :145-147.

- Al-Naama N.M., Ewaze J.O.,Nema J.H (1988) Chemical constituents of Iraqi truffles, Iraqi Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 6, 51-56.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).