Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Survey Instrument

2.3. Variables and Categorization

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Anthropometric Characteristics

3.2. Frequency of SSB Consumption

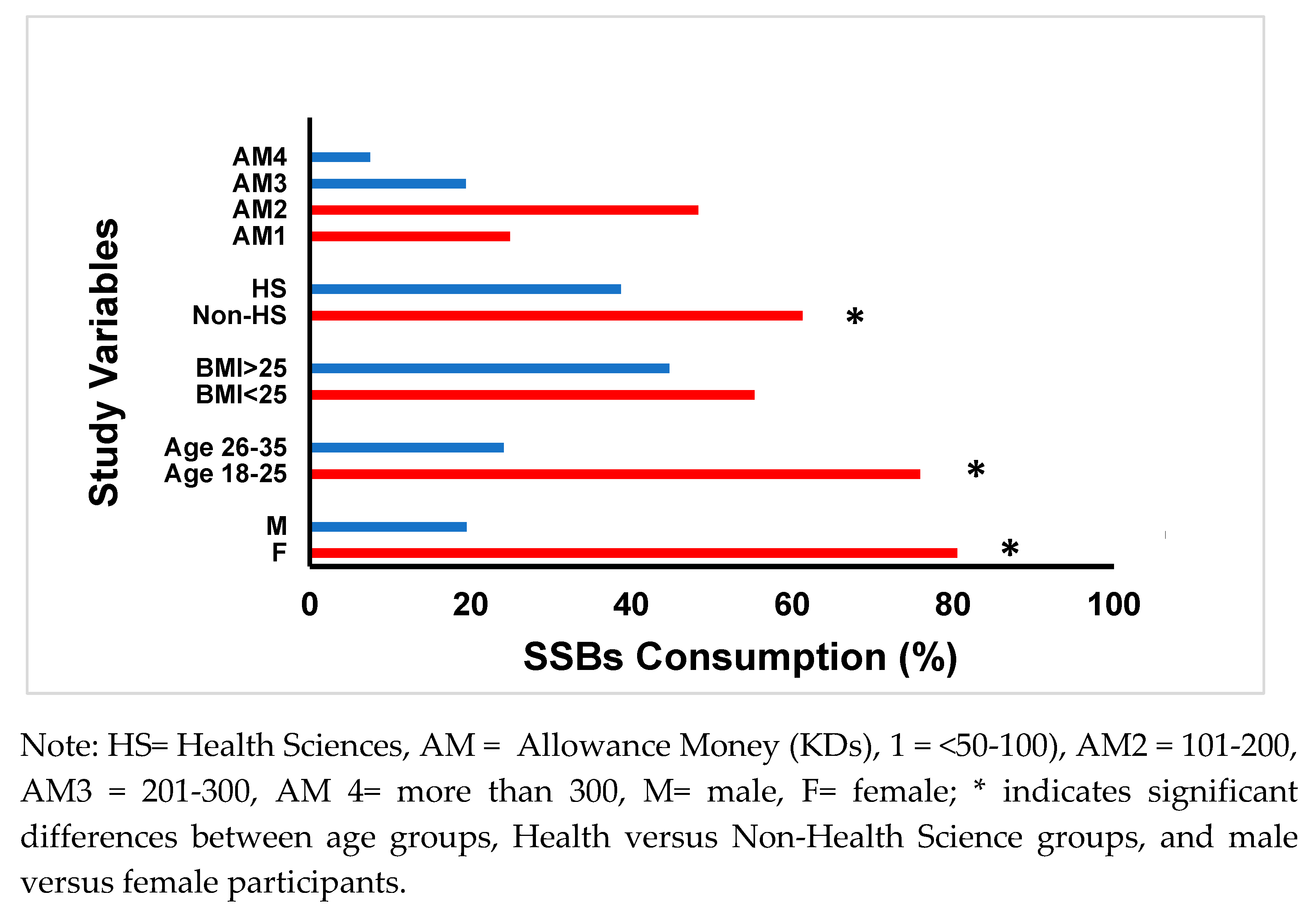

3.3. Associations between Frequency of SSB Consumption and the Sociodemographic Factors

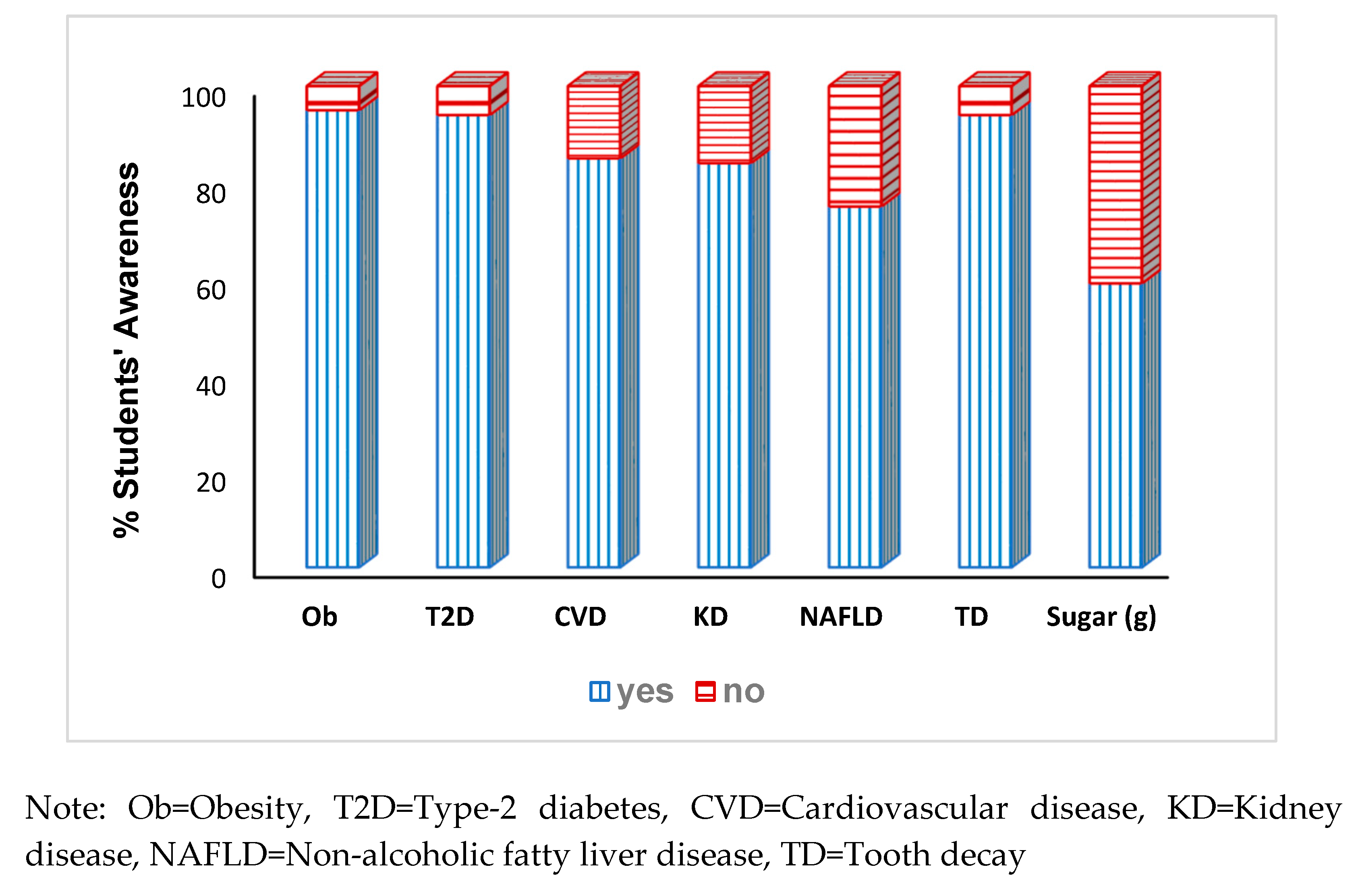

3.4. Behavior Towards SSB Consumption and Awareness of Health Risks

3.5. Sugar Intake from SSBs

3.6. Associations Between Sugar Intake from SSBs and Gender, Age, BMI, Major Area of Study, Allowance Money, Awareness of Disease Risk, and Behavior Towards Sugary Drinks

3.7. Regression Analysis of Sugar Intake from SSBs with Independent Variables and the Awareness of Disease Risk and Behavior Towards SSBs

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Public Health and Future Research Prospects:

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get the Facts: Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Consumption; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/data-statistics/sugar-sweetened-beverages-intake.html (accessed on February 20, 2022).

- Calcaterra, V.; Cena, H.; Magenes, V.C.; Vincenti, A.; Comola, G.; Beretta, A.; Di Napoli, I.; Zuccotti, G. Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Metabolic Risk in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 702. [CrossRef]

- Malik, V. S., & Hu, F. B. . The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2022, 18(4), 205–218. [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, L. R., Schwartz, M. B., & Brownell, K. D. . Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2007, 97(4), 667–675. [CrossRef]

- DiMeglio, D.P.; Mattes, R.D. Liquid versus Solid Carbohydrate: Effects on Food Intake and Body Weight. Int. J. Obes. 2000, 24, 794–800. [CrossRef]

- DiNicolantonio, J. J., O'Keefe, J. H., & Wilson, W. L. . Sugar addiction: Is it real? A narrative review. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018, 52(14), 910–913. [CrossRef]

- Weiderpass, E., Botteri, E., Longenecker, J. C., Alkandari, A., Al-Wotayan, R., Al Duwairi, Q., & Tuomilehto, J. The prevalence of overweight and obesity in an adult Kuwaiti population in 2014. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2019, 10, 449. [CrossRef]

- Alkandari, A.; Al Arouj, M.; Elkum, N.; Sharma, P.; Devarajan, S.; Abu-Farha, M.; Al-Mulla, F.; Tuomilehto, J.; Bennakhi, A. Adult Diabetes and Prediabetes Prevalence in Kuwait: Data from the Cross-Sectional Kuwait Diabetes Epidemiology Program. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3420. [CrossRef]

- Al-Haifi, A.R.; Al-Awadhi, B.A.; Al-Dashti, Y.A.; Aljazzaf, B.H.; Allafi, A.R.; Al-Mannai, M.A.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity among Kuwaiti Adolescents and the Perception of Body Weight by Parents or Friends. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0262101. [CrossRef]

- Al-Nesf, Y.; Kamel, M.; El-Shazly, M.K.; Makboul, G.M.; Sadek, A.A.; El-Sayed, A.M.; El-Fararji, A. Kuwait STEPS 2006. Kuwait Ministry of Health, GCC, WHO 2006.

- Alhareky, M.; Goodson, J.M.; Tavares, M.; Hartman, M.-L. Beverage Consumption and Obesity in Kuwaiti School Children. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1174299. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, W.W.; Cross, C.L. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences, 10th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA. 2019. Available online: https://view.publitas.com/uicneuro/neus444biostats/page/1.

- Nurses’ Health Study. 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2022, from https://nurseshealthstudy.org/sites/default/files/questionnaires/2019%20long.pdf.

- Rivard, C., Smith, D., McCann, S., & Hyland, A. Taxing sugar-sweetened beverages: A survey of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Public Health Nutrition. 2012, 15(8), 1355-1361. [CrossRef]

- West, D. S., Bursac, Z., Quimby, D., Prewitt, T. E., Spatz, T., Nash, C., Mays, G., & Eddings, K. Self-reported sugar-sweetened beverage intake among college students. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 2006, 14(10), 1825–1831. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E. Sugar-sweetened beverage intake among college students: A social-ecological model (Unpublished thesis dissertation). 2013, Ohio State University, USA.

- Bipasha, M.S.; Raisa, T.S.; Goon, S. Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Consumption among University Students of Bangladesh. Int. J. Public Health Sci. 2017, 6, 157–163. [CrossRef]

- Otaibi, H. H. A., & Kamel, S. M. Health-risk behaviors associated with sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among Saudi young adults. Biomedical Research. 2017, 28 (19), 8484-8491. https://www.alliedacademies.org/articles/healthrisk-behaviors-associated-with-sugarsweetened-beverage-consumption-among-saudi-young-adults-8644.html.

- Otaibi, H. H. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption behavior and knowledge among university students in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Economics and Business Management. 2017, 5(4), 173–176. [CrossRef]

- Harguth, A. An assessment of knowledge, behavior, and consumption patterns surrounding sugar-sweetened beverages among young adults. 2020, (Unpublished thesis dissertation). Minnesota State University, USA.

- Malik, V. S., Pan, A., Willett, W. C., & Hu, F. B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013, 98(4), 1084–1102. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Castor, L., Micha, R., Cudhea, F., Miller, V., Shi, P., Zhang, J., Sharib, J. R., Erndt-Marino, J. E., Cash, S. B., Barquera, S., & Mozaffarian, D. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages among children and adolescents in 185 countries between 1990 and 2018: Population-based study. BMJ, 2024, 386, e079234. [CrossRef]

- Rosinger, A., Herrick, K., Gahche, J., & Park, S. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among U.S. youth, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief (271), 2017, 1–8.

- American Heart Association. Sugar 101. Retrieved December 16, 2023, from https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sugar/sugar-101.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (9th ed.). 2020, Retrieved December 17, 2023, from https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.

- Arab Times Kuwait. Eating Habits Make Kuwaitis Prone to Very High Sugar Intake. April 21, 2016.

- Alsunni, A.A. Energy Drink Consumption: Beneficial and Adverse Health Effects. Int. J. Health Sci. 2015, 9, 468. [CrossRef]

- Asaad, Y.A. Energy Drinks Consumption in Erbil City: A Population-Based Study. Zanco J. Med. Sci. 2017, 21, 1680–1687. [CrossRef]

- Ghozayel, M., Ghaddar, A., Farhat, G., Nasreddine, L., Kara, J., & Jomaa, L. Energy drinks consumption and perceptions among university students in Beirut, Lebanon: A mixed methods approach. PLOS ONE, 2020, 15(4), e0232199. [CrossRef]

- Malinauskas, B. M., Aeby, V. G., Overton, R. F., Carpenter-Aeby, T., & Barber-Heidal, K. A survey of energy drink consumption patterns among college students. Nutrition Journal, 2007. 6, 35. [CrossRef]

- Trapp, G. S., Allen, K. L., O'Sullivan, T., Robinson, M., Jacoby, P., & Oddy, W. H. Energy drink consumption among young Australian adults: Associations with alcohol and illicit drug use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2014, 134, 30–37. [CrossRef]

- Azagba, S., Langille, D., & Asbridge, M. An emerging adolescent health risk: Caffeinated energy drink consumption patterns among high school students. Preventive Medicine, 2014, 62, 54–59. [CrossRef]

- Alsunni, A.A.; Badar, A. Energy Drinks Consumption Pattern, Perceived Benefits, and Associated Adverse Effects amongst Students at University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad, 2011, 23, 3–9.

- Itany, M., Diab, B., Rachidi, S., Awada, S., Al Hajje, A., Bawab, W., et al. Consumption of energy drinks among Lebanese youth: A pilot study on the prevalence and side effects. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors and Addiction, 2014, 3(3), e18857. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S., Tambawel, J., Trooshi, F. M., & Alkhoury, Y. Consumption pattern of nutritional health drinks and energy drinks among university students in Ajman, UAE. Gulf Medical Journal, 2013, 2(1), 22–26.

- Muñoz-Urtubia, N., Vega-Muñoz, A., Estrada-Muñoz, C., Salazar-Sepúlveda, G., Contreras-Barraza, N., & Castillo, D. Healthy behavior and sports drinks: A systematic review. Nutrients, 2023, 15, 2915. [CrossRef]

- Malik, V. S., Popkin, B. M., Bray, G. A., Després, J. P., Willett, W. C., & Hu, F. B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care, 2010, 33, 2477–2483.

- Malik, V. S. Sugar-sweetened beverages and cardiometabolic health. Current Opinion in Cardiology, 2017, 32, 572–579.

- Beck, A.L.; Martinez, S.; Patel, A.I.; Fernandez, A. Trends in Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption among California Children. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 2864–2869.

- Muñoz, V. C., Rovira, M. U., Ibáñez, V. V., Domínguez, J. M. M., Blanco, G. R., Rovira, M. U., & Toran, P. Consumption of soft, sports, and energy drinks in adolescents: The BEENIS study. Anales de Pediatría, 2020, 93, 242–250.

- Khan, N., & Mukhtar, H. Tea and health: Studies in humans. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 2013, 19 (34), 6141–6147. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B. The health benefits of tea. Eat Right. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2022. Retrieved December 2024 from https://www.eatright.org.

- Tea Association of the U.S.A., Inc. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://worldteadirectory.com/item/tea-association-u-s-a-inc/ Accessed –.

- Stangl, S. F. Food addiction and added sugar consumption in college-aged females. Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day, 2015. 47. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/elce_cscday/47.

- Meriç, Ç., Yabanci, N., & Yılmaz, H. Evaluation of added sugar and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption by university students. Kesmas National Public Health, 2021, 16, 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Yu, D., & Zhao, L. Trend of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and intake of added sugar in China's nine provinces among adults. Journal of Hygiene Research, 2014, 43(1), 70–72.

- Lee, S. H., Zhao, L., Park, S., Moore, L. V., Hamner, H. C., Galuska, D. A., & Blanck, H. M. High added sugars intake among US adults: Characteristics, eating occasions, and top sources, 2015–2018. Nutrients, 2023, 15(2), 265. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. K., Appel, L. J., Brands, M., Howard, B. V., Lefevre, M., Lustig, R. H., Sacks, F., Steffen, L. M., Wylie-Rosett, J., & American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism and the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2009, 120(11), 1011–1020. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, W.; Zhang, N.; Bak, K.H.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y. Sugar Reduction in Beverages: Current Trends and New Perspectives from Sensory and Health Viewpoints. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112076. [CrossRef]

- Alkazemi, D.; Zafar, T.A.; Ebrahim, M.; Kubow, S. Distorted Weight Perception Correlates with Disordered Eating Attitudes in Kuwaiti College Women. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 449–458. [CrossRef]

- Göbel, P.; & Dogan, H. Evaluation of eating attitudes, nutritional status, and anthropometric measurements of women who exercise: The case of Karabük. Black Sea Journal of Health Science, 2023, 6(2), 224–232. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S. H.; Merlo, C.; & Blanck, H. M. Associations between knowledge of health risks and sugar-sweetened beverage intake among US adolescents. Nutrients, 2023, 15(10), 2408. [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Dono, J.; Scully, M.; Morley, B.; & Ettridge, K. Adolescents' knowledge and beliefs regarding health risks of soda and diet soda consumption. Public Health Nutrition, 2022, 25(11), 3044–3053. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Onufrak, S.; Sherry, B.; & Blanck, H. M. The relationship between health-related knowledge and sugar-sweetened beverage intake among US adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2014, 114(7), 1059–1066. [CrossRef]

|

Variables |

Female n=331 (81%) |

Male n=80 (19%) |

Total n=411 (100%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age n (%) 18-25 26-35 |

262 (79.2) 69 (20.8) |

50 (62.5) 30 (37.5) |

312 (75.9) 99 (24.1) |

|

Anthropometrics mean ± SD Height a, cm Weight,b kg BMI,c kg/m2 |

158.75 ± 8.42 62.13 ± 14.99 24.63 ± 5.31 |

174.34 ± 6.67 87.02 ± 30.69 28.73 ± 10.66 |

161.80 ± 10.19 66.99 ± 21.45 25.44 ± 6.88 |

|

Study Major, n (%) Health Sciences Non-Health Sciences |

147 (44.4) 184 (55.6) |

12 (15.0) 68 (85.0) |

159 (38.7) 252 (61.3) |

|

Allowance money, d n (%) < 50-100 KD 101-200 KD 201-300 KD 301 KD and more |

82 (25.2) 167 (51.2) 54 (16.6) 23 (7.1) |

18 (23.7) 27 (35.5) 24 (31.6) 7 (9.2) |

100 (24.9) 194 (48.3) 78 (19.4) 30 (7.5) |

|

BMI e (kg/m2 ) n (%) ≤ 25 >25 |

194 (59.0) 135 (41.0) |

32 (40.0) 48 (60.0) |

226 (55.3) 183 (44.7) |

| SSBs | ≤1/month n (%) |

≤1/week n (%) |

2-4 /week n (%) |

5-6 /week n (%) |

≥7/week n (%) | Total n (%) | Total n (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Consumers* |

Consumers** |

||||||||

| Regular Sodaa | 115 (28) | 102 (35) | 66 (23) | 29 (10) | 92 (32) | 289 (71.5) | 404 (98.3) | ||

| Energy Drinksb | 291 (72) | 67 (58) | 20 (17) | 5 (4) | 23 (21) | 115 (28.3) | 406 (98.8) | ||

| Sports Drinksc | 359 (89) | 26 (60) | 9 (21) | 4 (10) | 4 (9) | 43 (10.7) | 402 (97.8) | ||

| Sweetened Iced Tea d | 273 (67) | 83 (61) | 26 (19) | 9 (7) | 17 (13) | 135 (33.1) | 408 (99.3) | ||

| Daily Sugar Consumed (g) by SSB Type | ||

| SSB (n, %) | Median |

IQR [25%, 75%] |

| Regular Soda (337, 87) | 38.10 | [14.04, 56.29] |

| Energy Drinks (164, 42.4) | 11.49 | [4.66, 15.47] |

| Sports Drinks (66, 16.9) | 9.59 | [4.26, 13.66] |

| Sweet Iced Tea (192, 49.7) | 5.37 | [3.71, 6.46] |

| Daily Total Sugar Intake (Z-Scores) | ||

| High intake (n=160, 41.6%) | 0.70 | [0.38, 1.36] |

| Low intake (n=226, 58.4%) | -0.58 | [-0.87, -0.32] |

| Z-Score from all SSBs (n=387, 100%) | -0.24 | [-0.68, 0.48] |

| (A) | |||

| Variables | Low intake | High intake | χ2, P, Cramer’s V |

| Gender, n (%) |

14.25, <0.001, 0.19 |

||

| Females | 218 (68.3) | 101 (31.7) | |

| Males | 30 (44.1) | 38 (55.9) | |

|

Age (years), n (%) 18-25 26-35 |

183 (61.0) 65 (74.7) |

117 (39.0) 22 (25.3) |

4.01, <0.04, 0.04 |

|

BMI (kg/m2), n (%) ≤ 25 >25 |

143(66.8) 104 (60.8) |

71(33.2) 69 (39.2) |

1.48, 0.23, 0.06 |

|

Study Major, n (%) Health Sciences Non-Health Sciences |

114 (77.6) 134 (55.8) |

33 (22.4) 106 (44.2) |

16.64, <0.001,0.21 |

|

AM a, KD b, n (%) < 50-100 101-200 200-300 301 and above |

62 (70.5) 115(63.2) 39 (59.1) 13 (72.2) |

26 (29.5) 67 (36.8) 27 (40.9) 5 (27.8) |

2.05, 0.56, 0.07 |

| (B) | |||

| Variables | Low Intake | High Intake | χ2, P, Cramer’s V |

|

Obesity, n (%) Yes No |

238 (63.5) 5 (41.7) |

137 (36.5) 7 (58.3) |

15.27, <0.001, 0.184 |

|

Type 2 Diabetea, n (%) Yes No |

234 (62.9) 6 (40.0) |

138 (37.1) 9 (60.0) |

2.10, 0.020, 0.124 |

|

CardiovasculaDiseases n (%) Yes No |

211 (62.2) 28 (58.3) |

128 (37.8) 20 (41.7) |

2.06, 0.563, 0.033 |

|

Kidney Diseases n (%) Yes No |

211 (63.0) 31 (59.6) |

124 (37.0) 21 (40.4) |

1.74, 0.532, 0.050 |

|

NAFLD c, n (%) Yes No |

185 (62.2) 54 (60.7) |

113 (37.9) 35 (39.3) |

0.20, 0.532, 0.018 |

|

Tooth Decay, n (%) Yes No |

235 (63.2) 5 (33.3) |

137 (36.8) 10 (66.7) |

4.25, 0.03, 0.134 |

|

Aware of Sugar Content of SSBs, n (%) Yes No |

157 (68.3) 90 (57.3) |

73 (31.7) 67 (42.7) |

4.25, 0.048, 0.039 |

|

Preference for Unsweetened Juices, n (%) Yes No |

167 (69.0) 73 (50.3) |

75 (31.0) 72 (49.7) |

14.88, <0.001, 0.192 |

| Dependent Variable, High sugar from SSBs =1 |

B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% CL Lower Upper |

Nagelkerke R Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Can frequent intake of SSBs increase the risk of obesity? | -1.95 | .57 | 11.65 | 1 | <.001 | .142 | 0.046 0.435 |

.144 |

| Can frequent intake of SSBs increase the risk of T2DM? | .39 | .55 | .49 | 1 | .486 | 1.470 | 0.497 4.351 |

. 022 |

| Can frequent intake of SSBs increase the risk of CVD? | -.05 | .35 | .02 | 1 | .883 | .949 | 0.477 1.892 |

.012 |

| Can frequent intake of SSBs increase the risk of KD? | -.19 | .36 | .26 | 1 | .608 | .830 | 0.408 1.691 |

.001 |

| Can frequent intake of SSBs increase the risk of NAFLD? | .27 | .29 | .85 | 1 | .357 | 1.304 | 0.741 2.293 |

.007 |

| Can frequent intake of SSBs increase the risk of TD? | -.54 | .47 | 1.34 | 1 | .247 | .580 | 0.231 1.458 |

.013 |

| Do you know how much sugar is in SSBs? | -.43 | .21 | 4.23 | 1 | .040 | .653 | 0.435 0.980 |

.106 |

| Do you prefer sweetened fruit juices? | -.81 | .22 | 14.63 | 1 | <.001 | .447 | 0.295 0.675 |

.143 |

| Dependent Variable: High sugar from SSBs =1 |

B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% CL Lower Upper |

Nagelkerke R Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Can frequent intake of SSBs increase of risk of obesity? | -1.79 | .59 | 9.06 | 1 | .003 | .167 | 0.052 0.536 |

.144 |

| Age =1 | -.78 | .27 | 8.07 | 1 | .005 | .460 | 0.269 0.786 |

|

| Gender =1 | .87 | .28 | 9.95 | 1 | .002 | 2.378 | 1.388 4.074 |

|

| Non-health Sciences = 1 | .77 | .236 | 10.71 | 1 | .001 | 2.165 | 1.363 3.439 |

|

| Do you know how much sugar is in SSBs? | -.43 | .21 | 4.23 | 1 | .040 | .653 | 0.435 0.980 |

.106 |

| Age =1 | -.79 | .27 | 8.49 | 1 | .004 | .455 | 0.268 0.733 |

|

| Gender =1 | .88 | .27 | 10.59 | 1 | .001 | 2.412 | 1.420 4.098 |

|

| Non-health Sciences =1 | .83 | .23 | 12.63 | 1 | <.001 | 2.293 | 1.451 3.624 |

|

| Your preference for fruit juices? | -.69 | .22 | 10.02 | 1 | .002 | .498 | 0.323 0.767 |

.118 |

| Age =1 | -.74 | .27 | 7.25 | 1 | .007 | .478 | 0.279 0.818 |

|

| Gender =1 | .89 | .28 | 10.65 | 1 | .001 | 2.456 | 1.432 4.212 |

|

| Non-health Sciences =1 | .74 | .24 | 9.62 | 1 | .002 | 2.087 | 1.311 3.322 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).