Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Samples

2.2.1. Sweet-Liker Status Solutions

2.2.2. Carbonated Beverage Samples

2.3. Sample Preparation and Testing Environment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Consumer Demographics

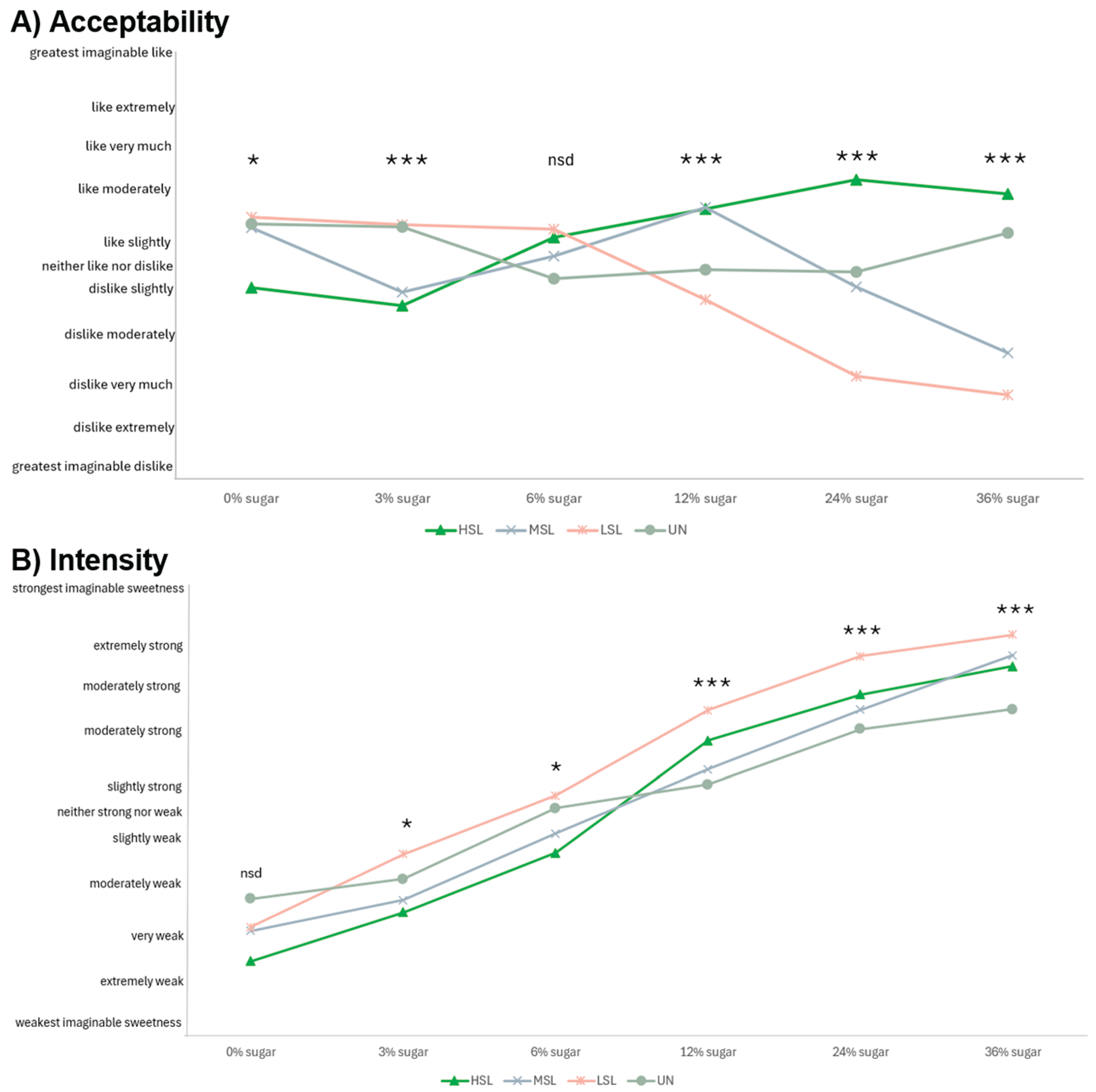

3.2. Acceptance and Perceived Sweetness Intensity of Sweet-Liker Status Clusters

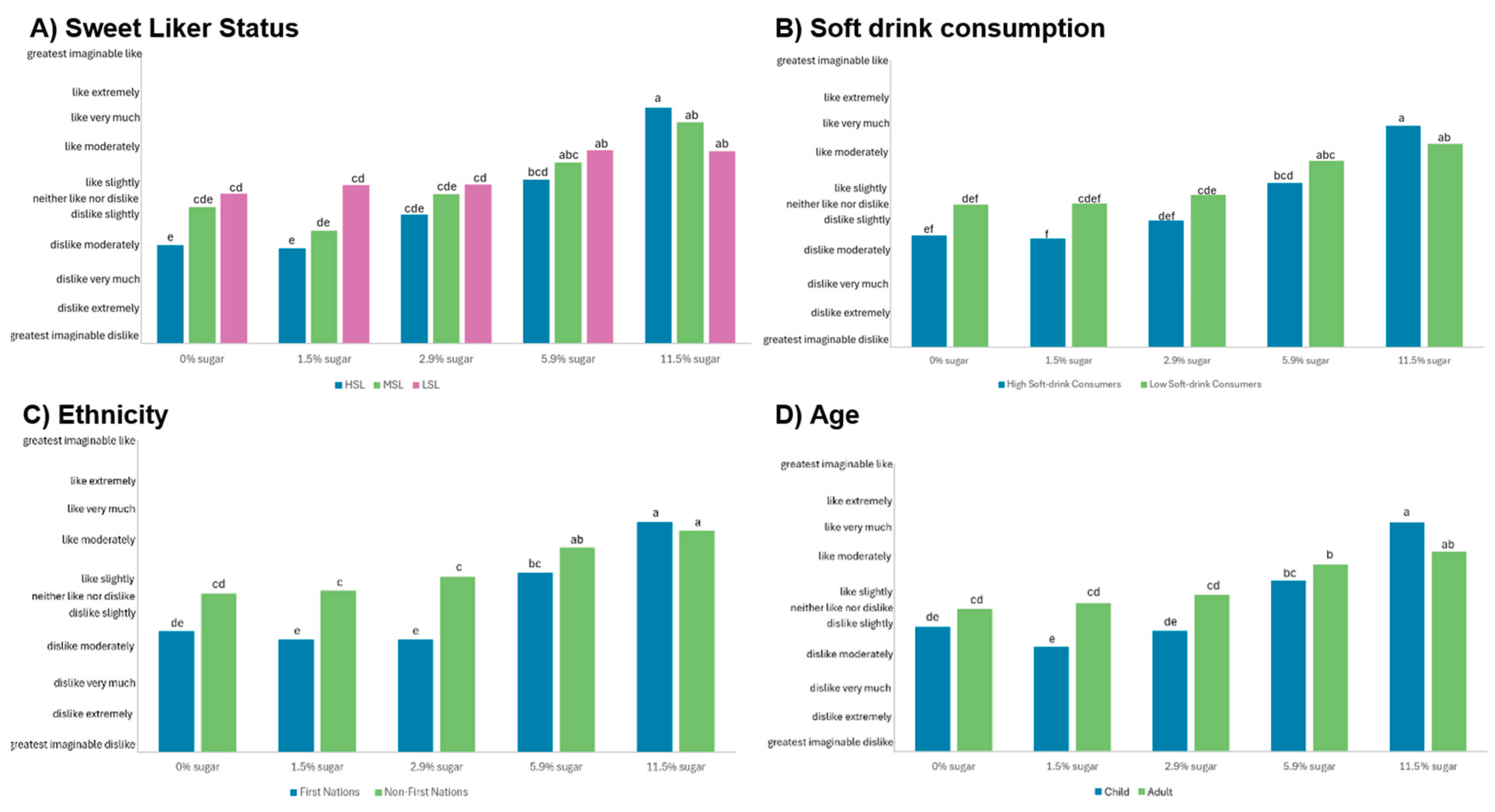

3.3. Sweet-Liker Status Clusters’ Sensory Acceptability of Carbonated Beverages Compared to Other Demographic Groups

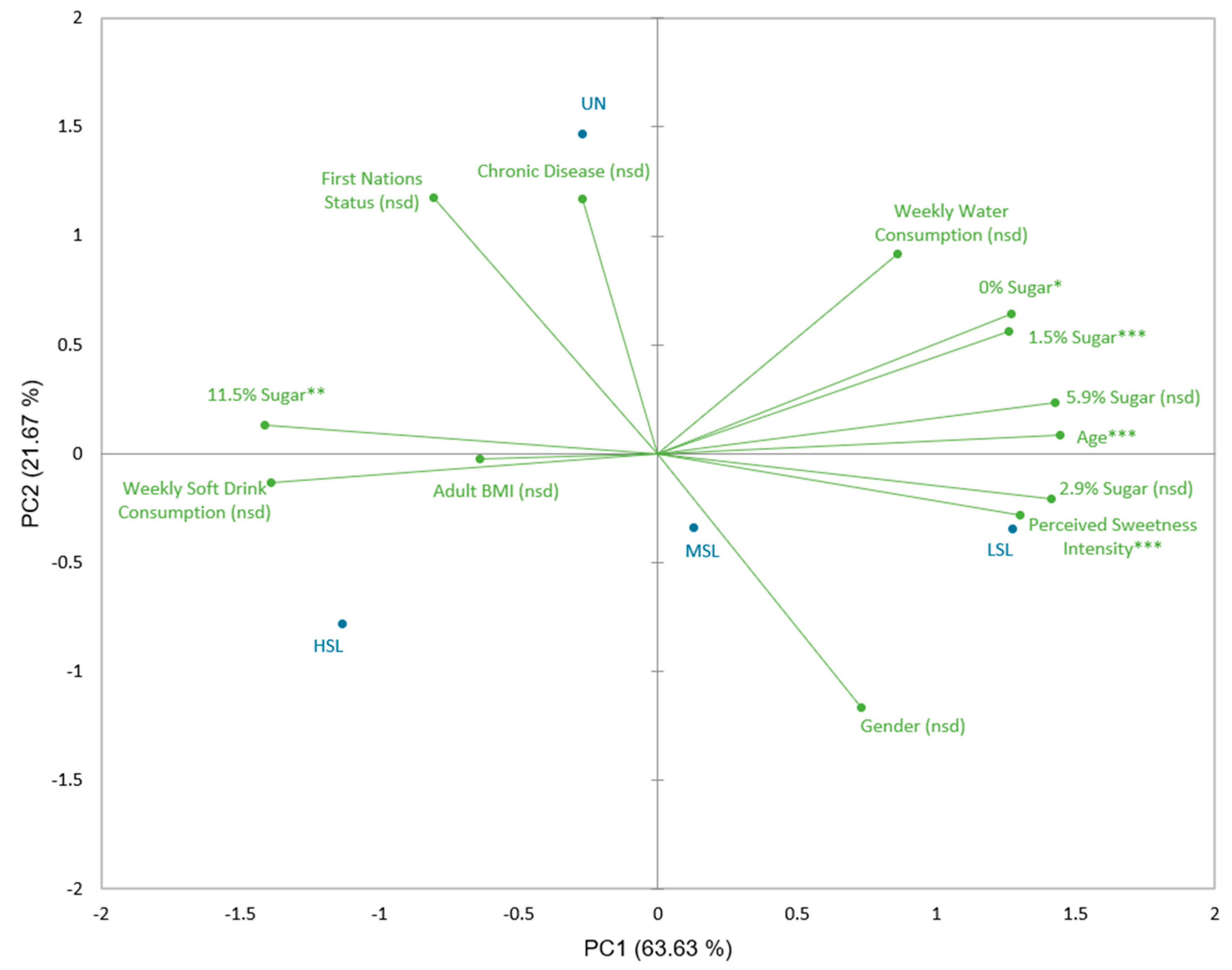

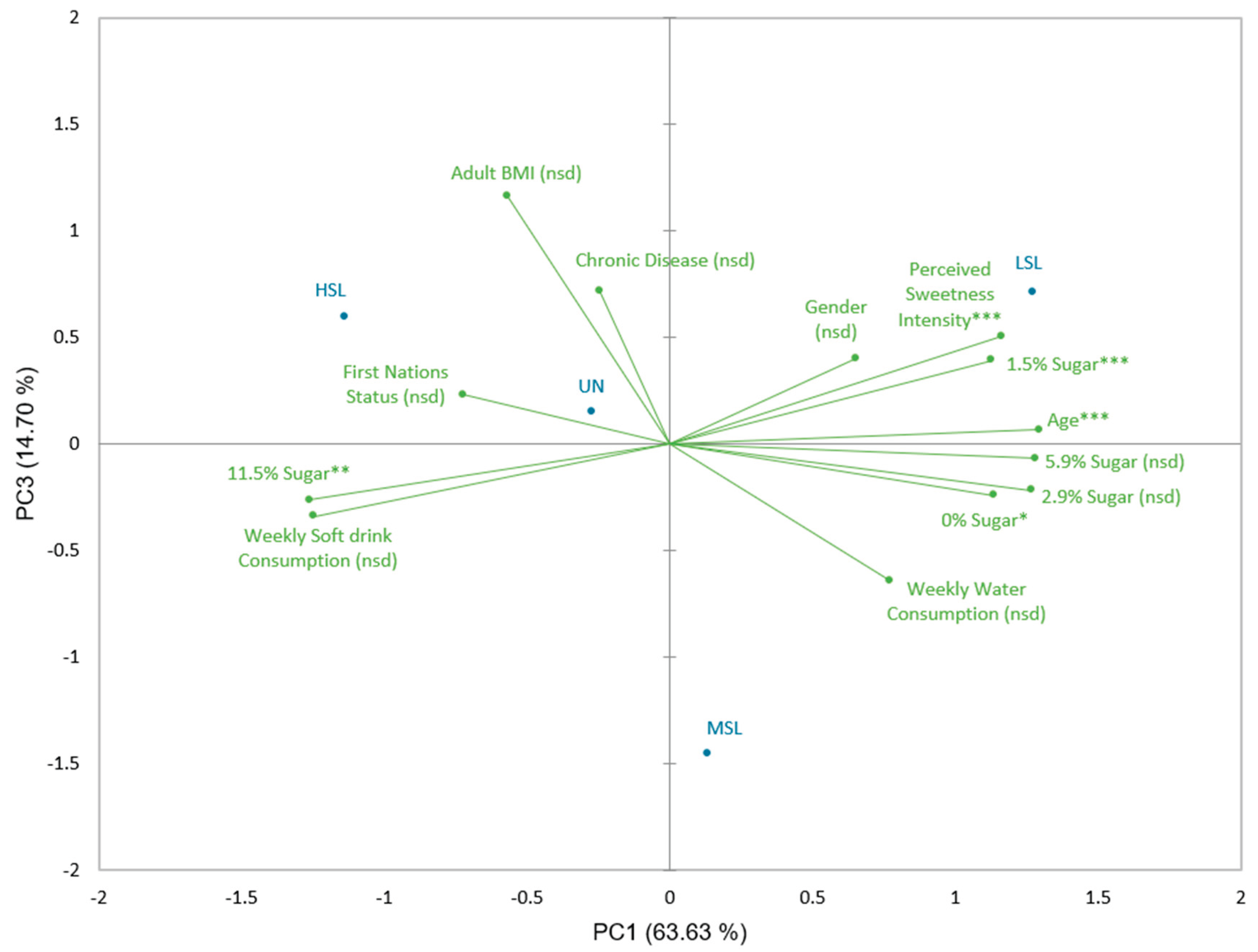

3.4. Sweet-Liker Status and Relationship with Demographics, Food Behaviour, and Health Status

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Examining the Basis of Sweet-Liker Status

4.3. Individual Level: The Future of Sweet-Liker Status

4.4. Policy Level: The Future of Sugar Reduction in Beverages

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SLS | Sweet liker status |

| SSB | Sugar-sweetened beverage |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| LSL | Low-sweet liker |

| MSL | Medium-sweet liker |

| HSL | High-sweet liker |

| UN | Unclassified |

| LAM | Labelled affective magnitude |

| gLMS | Generalized labelled magnitude scale |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

Appendix A

| Sucrose Concentration (%) | HSL | MSL | LSL | UN | F statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 44.8 (B) | 58.8 (AB) | 61.3 (A) | 59.7 (A) | 2.9* |

| 3 | 40.5 (B) | 43.7 (B) | 59.4 (A) | 58.9 (A) | 6.8*** |

| 6 | 56.5 (AB) | 52.1 (AB) | 58.5 (A) | 46.8 (B) | 2.3 NSD |

| 12 | 63.1 (A) | 63.6 (A) | 42.0 (B) | 48.9 (B) | 8.2*** |

| 24 | 70.1 (A) | 44.9 (B) | 24.0 (C) | 48.4 (B) | 30.7*** |

| 36 | 66.7 (A) | 29.4 (B) | 19.6 (B) | 57.6 (A) | 46.5*** |

Appendix B

| Sucrose Concentration (%) | HSL | MSL | LSL | UN | F statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.6 (B) | 23.4 (AB) | 24.2 (AB) | 30.5 (A) | 1.4 NSD |

| 3 | 27.5 (B) | 30.3 (B) | 40.5 (A) | 34.9 (AB) | 3.2* |

| 6 | 40.8 (B) | 45.1 (AB) | 53.6 (A) | 50.8 (AB) | 2.9* |

| 12 | 65.9 (AB) | 59.5 (B) | 72.6 (A) | 56.1 (B) | 7.6*** |

| 24 | 76.1 (B) | 72.7 (B) | 84.7 (A) | 68.4 (B) | 8.3*** |

| 36 | 82.5 (A) | 84.9 (A) | 89.5 (A) | 72.9 (B) | 8.9*** |

Appendix C

| HSL | MSL | LSL | UN | F statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of consumers | 9 | 14 | 73 | 15 | N/A |

| Age (years old) | 34.2 (A) | 37.8 (A) | 41.26 (A) | 37.267 (A) | 1.08 NSD |

| Gender (% female) | 55.6% (A) | 57.1% (A) | 74% (A) | 66.7% (A) | 0.85 NSD |

| Chronic disease status (%) | 11.1% (A) | 0% (A) | 5.5% (A) | 13.3% (A) | 0.87 NSD |

| Mean weekly soft drink consumption (L) | 0.688 (AB) | 0.759 (A) | 0.329 (AB) | 0.083 (B) | 1.57 NSD |

| Mean weekly water consumption (L) | 4.951 (A) | 6.5 (A) | 7.187 (A) | 7.083 (A) | 0.46 NSD |

| First Nations status (%) | 11.1% (A) | 7.1% (A) | 15.1% (A) | 20% (A) | 0.35 NSD |

| Perceived sweetness intensity | 47.056 (C) | 55.190 (B) | 60.63 (A) | 51.6 (B) | 6.98*** |

| BMI | 26.357 (A) | 24.346 (A) | 25.550 (A) | 25.673 (A) | 0.42 NSD |

References

- Feeney, E.; O'Brien, S.; Scannell, A.; Markey, A.; Gibney, E.R. Genetic variation in taste perception: does it have a role in healthy eating? Proc Nutr Soc. 2011, 70, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Basil, M.; Maibach, E.; Goldberg, J.; Snyder, D.A.N. Why Americans Eat What They Do: Taste, Nutrition, Cost, Convenience, and Weight Control Concerns as Influences on Food Consumption. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998, 98, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bailo, B.; Toguri, C.; Eny, K.M.; El-Sohemy, A. Genetic Variation in Taste and Its Influence on Food Selection. OMICS 2009, 13, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangborn, R.M. Individual variation in affective responses to taste stimuli. Psychonomic science 1970, 21, 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, K.C.; Ho, C.-Y.; Richard, J.M.; DiFeliceantonio, A.G. The tempted brain eats: Pleasure and desire circuits in obesity and eating disorders. Brain Res. 2010, 1350, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iatridi, V.; Hayes, J.E.; Yeomans, M.R. Reconsidering the classification of sweet taste liker phenotypes: A methodological review. Food quality and preference 2019, 72, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaliauskaite, G.; Thibodeau, M.; Ford, R.; Yang, Q. Using correlation matrices to standardise sweet liking status classification. Food quality and preference 2023, 104, 104759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Kraft, M.; Shen, Y.; MacFie, H.; Ford, R. Sweet Liking Status and PROP Taster Status impact emotional response to sweetened beverage. Food quality and preference 2019, 75, 133–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.; Tucker, R.M. Sweet taste as a predictor of dietary intake: A systematic review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.H.A.; Cobiac, L.; Beaumont-Smith, N.E.; Easton, K.; Best, D.J. Dietary habits and the perception and liking of sweetness among Australian and Malaysian students: A cross-cultural study. Food quality and preference 2000, 11, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garneau, N.L.; Nuessle, T.M.; Mendelsberg, B.J.; Shepard, S.; Tucker, R.M. Sweet liker status in children and adults: Consequences for beverage intake in adults. Food Qual Prefer. 2018, 65, 175–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-McGrievy, G.; Tate, D.F.; Moore, D.; Popkin, B. Taking the Bitter with the Sweet: Relationship of Supertasting and Sweet Preference with Metabolic Syndrome and Dietary Intake. Journal of Food Science 2013, 78, S336–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, F.; Donaldson, L.F.; Markland, D.A.; Loveday, H.; Jackson, M.J.; Kubis, H.-P. Taste perception and implicit attitude toward sweet related to body mass index and soft drink supplementation. Appetite 2011, 57, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methven, L.; Xiao, C.; Cai, M.; Prescott, J. Rejection thresholds (RjT) of sweet likers and dislikers. Food quality and preference 2016, 52, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatridi, V.; Hayes, J.E.; Yeomans, M.R. Quantifying sweet taste liker phenotypes: Time for some consistency in the classification criteria. Nutrients 2019, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asao, K.; Miller, J.; Arcori, L.; Lumeng, J.C.; Han-Markey, T.; Herman, W.H. Patterns of sweet taste liking: A pilot study. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7298–7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A.; Henderson, S.A.; Shore, A.B.; Barratt-Fornell, A. Nontasters, Tasters, and Supertasters of 6- n-Propylthiouracil (PROP) and Hedonic Response to Sweet. Physiol Behav. 1997, 62, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeomans, M.R.; Tepper, B.J.; Rietzschel, J.; Prescott, J. Human hedonic responses to sweetness: Role of taste genetics and anatomy. Physiol Behav. 2007, 91, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, R.M.; Iatridi, V.; Sladekova, M.; Yeomans, M.R. Comparing body composition between the sweet-liking phenotypes: experimental data, systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond). 2024, 48, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugnaloni, S.; Alia, S.; Mancini, M.; Santoro, V.; Di Paolo, A.; Rabini, R.A.; et al. A study on the relationship between type 2 diabetes and taste function in patients with good glycemic control. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.H.; Shin, M.-S.; Lee, J.R.; Choi, J.H.; Koh, E.H.; Lee, W.J.; et al. Decreased sucrose preference in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014, 104, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, J.; Smyth, H.E.; Netzel, M.E.; Sultanbawa, Y.F.; Wright, O.R.L. A Hedonic Sensory Trial: Exploring the Relationship Between Sweet-Liker Status, Demographics, and Health Measures on Acceptability in a Beverage System. Journal of sensory studies 2025, 40, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennella, J.A.; Bobowski, N.K.; Reed, D.R. The development of sweet taste: From biology to hedonics. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2016, 17, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldwell, S.E.; Oswald, T.K.; Reed, D.R. A marker of growth differs between adolescents with high vs. low sugar preference. Physiol Behav. 2009, 96, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desor, J.A.; Beauchamp, G.K. Longitudinal changes in sweet preferences in humans. Physiol Behav. 1987, 39, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children (ISBN 978-92-4-154902-8). 2015. [Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549028.

- World Health Organization. Taking Action on Childhood Obesity 2018. [Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/274792/WHO-NMH-PND-ECHO-18.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- Hu, F.B. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. 2013, 14, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.A.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Controversies about sugars: results from systematic reviews and meta-analyses on obesity, cardiometabolic disease and diabetes. Eur J Nutr. 2016, 55 (Suppl 2), 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Hu, F.B. The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Welcome to the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2024. [Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/.

- Hedrick, V.E.; Savla, J.; Comber, D.L..; Flack, K.D.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Nsiah-Kumi, P.A.; et al. Development of a Brief Questionnaire to Assess Habitual Beverage Intake (BEVQ-15): Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Total Beverage Energy Intake. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012, 112, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Sensory Evaluation of Food; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, H.G.; Cardello, A.V. A LABELED AFFECTIVE MAGNITUDE (LAM) SCALE FOR ASSESSING FOOD LIKING/DISLIKING. Journal of sensory studies. 2001, 16, 117–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoshuk, L.M.; Duffy, V.B.; Fast, K.; Green, B.G.; Prutkin, J.; Snyder, D.J. Labeled scales (e.g., category, Likert, VAS) and invalid across-group comparisons: what we have learned from genetic variation in taste. Food quality and preference 2003, 14, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. Standard Guide for Preferred Methods for Acceptance of Product; p. 2018.

- BS EN ISO 11136:2017+A1:2020; Sensory analysis. Methodology. General guidance for conducting hedonic tests with consumers in a controlled area. British Standards Institute, 2020.

- Gascoyne, C.; Scully, M.; Wakefield, M.; Morley, B. Sugary drink consumption in Australian secondary school students; Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, Cancer Council: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Australia. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child New South Wales (AU): UNICEF. 2025. [cited 2025 Apr 2]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.au/united-nations-convention-on-the-rights-of-the-child?srsltid=AfmBOooDaS3ugM0zs4-ij0kngnsdKeNQbd7iqRNRk0URd3TNJyq6OqJL.

- Slocombe, B.G.; Carmichael, D.A.; Simner, J. Cross-modal tactile–taste interactions in food evaluations. Neuropsychologia 2016, 88, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Hu, Y.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, B. Five representative esters and aldehydes from fruits can enhance sweet perception. Food science & technology 2024, 194, 115804. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, T.P.; Melichar, J.K.; Nutt, D.J.; Donaldson, L.F. Human Taste Thresholds Are Modulated by Serotonin and Noradrenaline. J Neurosci. 2006, 26, 12664–12671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, K.M. Liking for Sweet Taste, Sweet Food Intakes, and Sugar Intakes. Nutrients. 2024, 16, 3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, D.G.; de Graaf, C. Sweet and sour preferences in young children and adults: role of repeated exposure. Physiol Behav. 2004, 83, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Prescott, J.; Kim, K.-O. Patterns of sweet liking in sucrose solutions and beverages. Food quality and preference 2014, 36, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R.M.; Iatridi, V.; Thanh Vi, C.; Yeomans, M.R. Phenotypic differences in taste hedonics: The effects of sweet liking. Food quality and preference 2023, 107, 104845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A. Taste preferences and food intake. Annu Rev Nutr. 1997, 17, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Sorokowska, A.; Marczak, M.; Niemczyk, A.; Butovskaya, M.; Huanca, T.; et al. Mapping sweetness preference across the lifespan for culturally different societies. Journal of environmental psychology 2018, 58, 72–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, C.; Zandstra, E.H. Sweetness Intensity and Pleasantness in Children, Adolescents, and Adults. Physiol Behav. 1999, 67, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Ginieis, R.; Abeywickrema, S.; McCormack, J.; Prescott, J. Rejection thresholds for sweetness reduction in a model drink predict dietary sugar intake. Food quality and preference 2023, 110, 104965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrico, D.D.; Tam, J.; Fuentes, S.; Gonzalez Viejo, C.; Dunshea, F.R. Consumer rejection threshold, acceptability rates, physicochemical properties, and shelf-life of strawberry-flavored yogurts with reductions of sugar. J Sci Food Agric. 2020, 100, 3024–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineli, L.d.L.d.O.; Aguiar LAd Fiusa, A.; Botelho, R.B.d.A.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Melo, L. Sensory impact of lowering sugar content in orange nectars to design healthier, low-sugar industrialized beverages. Appetite 2016, 96, 239–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population: Census 2021. [Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/population-census/latest-release.

- Robertson, S.; Clarke, E.D.; Gómez-Martín, M.; Cross, V.; Collins, C.E.; Stanford, J. Do Precision and Personalised Nutrition Interventions Improve Risk Factors in Adults with Prediabetes or Metabolic Syndrome? A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinnette, R.; Narita, A.; Manning, B.; McNaughton, S.A.; Mathers, J.C.; Livingstone, K.M. Does Personalized Nutrition Advice Improve Dietary Intake in Healthy Adults? A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md). 2021, 12, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.E.; Garza, J. Consumer likings of different miracle fruit products on different sour foods. Foods 2021, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čad, E.M.; van der Kruijssen, M.; Tang, C.S.; Pretorius, L.; de Jong, H.B.T.; Mars, M.; et al. Three independent measures of sweet taste liking have weak and inconsistent associations with sugar and sweet food intake - insights from the sweet tooth study. Food quality and preference 2025, 130, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; He, F.J.P.; Yin, Y.B.; Hashem, K.M.M.; MacGregor, G.A.P. Gradual reduction of sugar in soft drinks without substitution as a strategy to reduce overweight, obesity, and type 2 diabetes: a modelling study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, C.; Baker, P.; Grimes, C.; Lawrence, M.A. What are the benefits and risks of nutrition policy actions to reduce added sugar consumption? An Australian case study. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 2025–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food Regulation. Policy context relating to sugars in Australia and New Zealand: Australian Government; 2017 [updated 4 Jan 2024. Available from: https://www.foodregulation.gov.au/resources/publications/policy-context-relating-sugars-australia-and-new-zealand.

- Australian Beverages. Sugar Reduction Pledge 2024. [Available from: https://www.australianbeverages.org/initiatives-advocacy-information/sugar-reduction-pledge/.

- Breadon, P.; Geraghty, J. Sickly sweet: It’s time for a sugary drinks tax: Grattan Institute; 2024. [Available from: https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Sickly-Sweet-Grattan-Institute-Report-May-2024.pdf.

- Jeffrey, D. Increasing sugar in Fanta sparks call for new tax on soft drinks 2024. [Available from: https://www.9news.com.au/national/fanta-increased-sugar-calls-tax-ama/554c7ba1-ca75-4084-9741-0a3f42424d7b.

- Department of Health and Aged Care. Partnership Reformulation Program: Australian Government; 2024. [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/healthy-food-partnership/partnership-reformulation-program.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Healthy Food Partnership Reformulation Program: Wave 2, two-year progress 2024. [Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/healthy-food-partnership-reformulation-program-wave-2-two-year-progress.

- Australian Medical Association. AMA welcomes sweet push on sugar tax reform 2024. [Available from: https://www.ama.com.au/media/ama-welcomes-sweet-push-sugar-tax-reform.

| Number of participants | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total participants | 142 | N/A |

| Adults | 111 | 78 |

| Children | 31 | 22 |

| First Nations | 32 | 23 |

| Non-First Nations | 110 | 77 |

| Male | 45 | 32 |

| Female | 96 | 68 |

| Non-binary/other | 1 | 0.7 |

| Chronic disease | 8 | 5.6 |

| No chronic disease | 134 | 94 |

| HSL | MSL | LSL | UN | F statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of consumers | 19 | 20 | 79 | 24 | N/A |

| Number of children | 10 | 6 | 6 | 9 | N/A |

| Age (years old) | 21.8 (C) | 30.3 (B) | 39.3 (A) | 28.8 (BC) | 8.67*** |

| Gender (% female) | 65% (A) | 67% (A) | 72.2% (A) | 58.3% (A) | 0.58 NSD |

| Chronic disease status (%) | 5.3% (AB) | 0% (B) | 5.1% (AB) | 12.5% (A) | 1.12 NSD |

| Mean weekly soft drink consumption (L) | 1.0 (A) | 0.82 (AB) | 0.39 (B) | 0.77 (AB) | 1.41 NSD |

| Mean weekly water consumption (L) | 6.3 (A) | 7.3 (A) | 7.1 (A) | 7.4 (A) | 0.14 NSD |

| First Nations status (%) | 26.3% (AB) | 20% (AB) | 17.7% (B) | 37.5% (A) | 1.46 NSD |

| Perceived sweetness intensity | 51.6 (B) | 52.6 (B) | 60.8 (A) | 52.3 (B) | 7.36*** |

| Adult BMI | 26.4 (A) | 24.4 (A) | 25.6 (A) | 25.7 (A) | 0.42 NSD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).