1. Introduction

The lighting system on a ship is made up of three distinct and separate networks:

- Main lighting, supplied by the ship's main electrical power sources.

- Emergency lighting, supplied by the ship's emergency source of electrical power. If the main power supply is interrupted, the required emergency lighting shall be automatically switched on.

- Escape (transitional) lighting, powered by a battery back-up (transitional) source of electrical power. The escape lighting system shall be activated automatically in the event of failure of the main and emergency power sources. This type of escape lighting is mandatory on ships where the emergency power supply is not automatically connected to the main emergency busbar within 45 seconds or where the class notation is passenger ship and ferry (IMORULES, 2024).

Escape (transitional) lighting is a safety lighting used to illuminate safe escape routes, as well as facilitate visibility and indicate the direction of the escape route. It is also used as an anti-panic lighting. This escape lighting is activated when the vessel is in blackout condition, so its maintenance and periodic functional tests are vitally important, since it is a lighting that only comes into operation in the event of a failure (Jelena, 2006; Aizlewood and Webber, 1995; Towle, 1994). A well-designed lighting environment in improving safety and comfort aboard ships (Zhang et al., 2023)

Escape lighting is connected to the emergency power supply, producing, in addition to emergency lighting, transitional lighting until the emergency generator starts and is connected to the main emergency busbars (Li et al., 2024). This type of escape lighting is based on the fact that the power does not depend on the ship's electrical networks (mains or emergency) but on an independent source of batteries that guarantee the lighting of said luminaries for a period of time (International Maritime Organization, 2020; American Bureau of Shipping, 2021; European Maritime Safety Agency, 2019), usually one or three hours, according to the manufactures datasheet. These batteries can be integrated into the luminaires themselves or through centralized battery systems (Uninterruptable Power Supply, UPS). Preventive maintenance of this escape lighting has been carried out through manual and obsolete manned tests that have often been eliminated in order to reduce maintenance costs or have been omitted (Achim, 2017).

The IEC 62034:2012 standard - Automatic test systems for battery powered emergency escape lighting - outlines the performance and safety requirements for automatic test systems used in emergency lighting systems operating at voltages up to 1,000 V. It covers the monitoring of timing circuits, functional requirements, handling of component and software failures, and specifies the necessary functional and duration tests to ensure system reliability and safety. This standard is essential for maintaining the effectiveness of emergency lighting systems during power outages or emergencies. The IEC 62034:2012 standard is based on the development of an automatic test system for battery-operated escape luminaires (centralized or individual), where the escape luminaires are tested through scheduled tests of in a reliable and safe manner, providing information on individual failures of each luminary and the escape lighting system itself, which will allow the generation of the necessary information to guarantee the correct functioning of the escape luminaires installed when required. To this purpose, the standard identifies the performance of the following two tests:

• Functional test: test to check the integrity of the circuit and the correct operation of a luminary, the changeover device and the back battery. A functional test shall be performed at least once a month.

• Duration test: test to check if the backup battery power supply source supplies the system within the limits of rated duration of emergency operation. A functional test shall be performed at least once a year.

In addition, information regarding of the status of each luminary is always available on the remote control station. Having said that, the application of this standard always requires human action for corrective maintenance.

Techno-economic analyses of escape lighting on ships is crucial for enhancing safety during emergencies while also considering the economic implications of lighting technologies. One of the primary considerations in the techno-economic analysis is the transition from traditional lighting systems to more advanced technologies, particularly LED lighting. Currently, lighting with LED has replaced the outdated, inefficient and polluting fluorescent lighting in shipbuilding for multiple reasons such as: reduction in the costs of generating electrical energy, increase in the useful life of the lamp with the consequent reduction of maintenance costs, ease of regulation and information on the status of the driver and the lamp as well as the control and monitoring of the luminaires (Shibabrata et al., 2019; Andrzej, 2016). Recent studies have highlighted the benefits of replacing traditional lighting systems with LED technology. For instance, Sędziwy et al. (2018) emphasize the financial benefits associated with energy-efficient installations, noting that retrofitting existing systems can lead to substantial cost savings over time due to reduced energy consumption and maintenance costs. This aligns with findings from Salata et al. (2015), who discuss energy optimization in lighting systems, suggesting that the initial investment in advanced lighting technologies can be offset by long-term savings and improved operational efficiency.

Wati et al. (2023) indicate that the integration of LED technology into ship lighting systems significantly enhances operational efficiency and sustainability. LEDs consume less power and have a longer lifespan compared to conventional lighting, which translates to lower maintenance and replacement costs over time. Furthermore, Suardi et al. (2023) demonstrate that the application of LED lamps can reduce generator power requirements on ships, thereby decreasing fuel consumption and associated operational costs. This reduction in energy demand not only lowers expenses but also contributes to a ship's overall environmental sustainability. Even the classification societies have adapted their rules to the LED technology, including in their standards a section for lighting based on controllers (DNV, 2012). Other authors proposed energy-efficient lighting systems for ships based on solar-powered systems (Muzaki et al., 2024) and integrate smart technologies into escape lighting systems such as intelligent lighting controls that optimize energy use and enhance safety by adjusting lighting levels based on real-time conditions (Yao et al., 2023; Talluri et al., 2016). This adaptability not only improves safety outcomes but also contributes to further cost savings through efficient energy management. Lin et al. (2022) highlight that the financial performance of shipping companies can be improved through investments in energy-efficient technologies, which can lead to lower operational costs and enhanced safety measures. This aligns with findings from Wang and Lee (2010), who emphasize the importance of evaluating financial performance through various indices, suggesting that companies that invest in efficient technologies may rank higher in financial assessments. Moreover, the initial investment in advanced lighting systems must be weighed against long-term savings. Christodoulou et al. (2021) discuss the economic impacts of regulatory frameworks, such as the EU Emissions Trading System, which can influence operational costs for shipping companies. The implementation of escape lighting systems that comply with safety regulations can be viewed as a necessary investment that not only enhances safety but may also mitigate potential costs associated with non-compliance during inspections or emergencies.

The economic benefits of escape lighting extend beyond direct savings. Effective lighting can enhance the overall safety of the vessel, potentially reducing liability and insurance costs. Jin and Schinas (2019) note that shipping companies that prioritize safety and compliance with regulations are often viewed more favorably by investors, which can lead to better financing opportunities. This perspective aligns with the findings of Lin et al. (2024), who indicate that financial indicators play a crucial role in attracting investment, particularly in the context of emergency preparedness and safety measures.

The present work analyzes the implementation of the 62034:2012 standard in a multipurpose (MPV) vessel from a techno-economic point of view. Traditionally, emergency and escape lighting, which is mandatory on most merchant ships, has only been analysed from the point of view of its power supply from the ship's emergency source, so that the only thing that mattered for shipowners, crew and classification societies was that when the ship was in an emergency situation, the emergency and escape lighting would be switched on automatically, thus generating the minimum required lux. This article shows the advantages of implementing the IEC62034 standard, which is never applied to ships, to reduce maintenance costs and above all, to avoid any failure due to human negligence in an emergency situation, where there can be no failures as the life of the crew or the integrity of the ship may be affected and not to depend on obsolete maintenance techniques, which are often obsolete due to lack of time or resources. The ease of implementation, cost reduction and improved safety mean that the application of the IEC 62034:2012 standard (Automatic test systems for battery powered emergency escape lighting, which is currently not applied on any ship, can be another tool to improve safety on board.

The number of luminaires to be installed for each network of the ship was calculated, focusing on the luminaires affected by the IEC 62034:2012 standard (escape luminaires), as well as the installed battery power. There are some manufactures of marine luminaries which has implemented is own system of monitoring the luminaries. In this report, DALI protocol is used in order to do not depend to any kind of marine naval manufacture so installed naval luminaries only needs to have a DALI driver. The manufacturer selected for the luminaries is the well-known manufacturer LIGHTPARTNER, but others can be used and also combine with others, mixing the manufactures. The economic analysis of the necessary investment was carried to analyze the following indicators: NPV (Net Present Value), IRR (Internal Rate of Return) and discounted pay-back period (DPBP), in order to analyze its feasibility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case of Study

A MPV includes a wide variety of tonnage and length vessels which it is capable of supporting the following activities:

• Oceanographic Research

• Fisheries Research

• Acoustic Fisheries Surveys

• Underwater TV Surveys

• Ichtyplankton Surveys

• Hydrographic Surveys

• ROV Surveys

• AUV/ASV Surveys

• Coring/Grab Sampling

• Drop Camera

• Buoy/Mooring Operations

Given the previous operation of the vessel, the accommodation on the surveyed vessel is designed for a mixture of crew and scientists (and other passengers). These scientists are not sailors, so escape lighting is normally installed for the safety of this type of passenger.

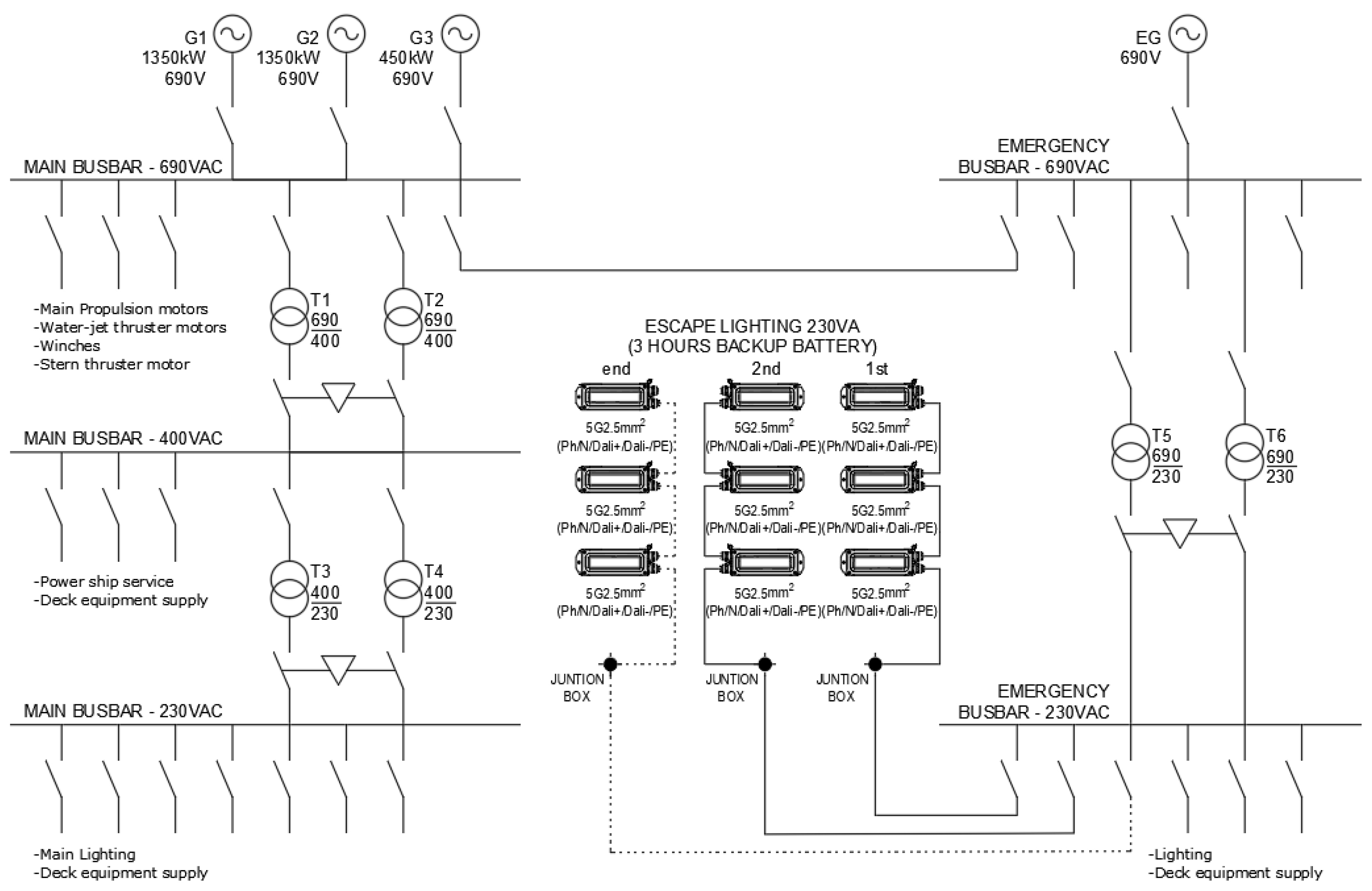

The LED lighting on this vessel consists of the following systems:

- Main lighting system supplied by three 690V main generators via main transformers.

- Emergency lighting system powered by the emergency generator via emergency transformers. Under normal conditions, the emergency lighting is supplied from the main switchboard via an interconnecting circuit breaker.

- Escape (transitional) lighting with 3 hour integral battery system connected as an extension to the emergency lighting.

Figure 1 shows the main networks of the vessel.

The dimensions of the MPV analyzed are shown in

Table 1.

The ship must be adequately illuminated with the lighting levels required by National Authorities and legislation (ISO, 2006), and at least the lighting levels measured at 700 mm above the deck indicated in

Table 2.

According to the manufacturer's instructions (LIGHTPARTNER LICHTSYSTEME GMBH & CO. KG), the standard useful life of this type of LED luminaires is estimated at 80,000 hours, which is equivalent to approximately 10 years.

2.2. Economic Indicators

The economic viability of the proposal was assessed using economic parameters. To evaluate the economic feasibility, the Cash Flow was calculated over its useful life, along with the net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR) and discounted pay-back period (DPBP).

The NPV represents the present value of the cash flows at the required rate of return of economic savings generated by the implementation of the IEC 62034:2012 standard compared to the initial investment, Equation (1).

where CF

t is the cash flow in year t, r the discount rate r, n the number of time periods, and G

0 the initial investment.

If the NPV is higher than 0, the investment will generate earnings above the required return (r). This will imply that the acceptance of the proposal is recommended. On the contrary, if the NPV is less than 0, the investment produces returns below the required minimum return (r) and it is not recommended to accept the proposal. In case NPV equals 0, the proposal does not add monetary value above the required profitability (r) and the decision must be based on other criteria.

The IRR represents the interest generated by the proposal over its useful life. It is calculated as the discount rate that returns the NPV to zero, Equation (2), meaning it is the interest rate that makes the future cash flows financially equivalent to the initial investment.

The proposal's economic feasibility hinges on the IRR. If the IRR is less than the required rate of return (r), the proposal's profitability falls short of the minimum threshold, making the investment inadvisable. Conversely, if the IRR exceeds r, the proposal's profitability surpasses the minimum requirement, making it a favorable investment. In case the IRR equals r, the profitability matches the required rate, similar to a scenario where the Net Present Value (NPV) is zero, and the decision then depends on other criteria.

The DPBP measures the amount of time it takes to number of years it takes to break even from undertaking the initial expenditure, Eq. (3).

The ideal DPBP is as short as possible. If the DPBP is less than the proposal's lifespan (t), the initial investment is recovered more quickly than the proposal's duration, making it advisable to accept the proposal. If the DPBP equals the proposal's lifespan, the recovery time matches the proposal's duration, making the decision neutral. However, if the DPBP exceeds the proposal's lifespan, the initial investment takes longer to recover than the proposal's duration, suggesting that the proposal should be rejected.

2.3. Modification of Lighting to Implement the IEC 62034:2012 Standard

To comply with the IEC 62034:2012 standard, the following implementations/modifications must be made to the installation:

1. Modify the luminaire internally, because the current driver must be replaced by a driver that allows control of the luminaire, which must be a driver with Dali technology or similar (currently, the technology used is Dali-2), in addition to modifying the number of internal connectors to install the wires corresponding to the Dali bus. If luminaries with DALI driver are installed, this step is not necessary.

2. The Dali bus must be included to connect each luminaire and the controller, so a 3G1.5mm2 (Ph/N/PE) cable will be changed to 5G1.5mm2 (Ph/N/Dali+ /Dali-/PE) or 3G1.5 (power lighting)+2x1.5mm2 (DALI bus). There are other solutions, but this is the one that least affects the electrical installation and the one that is commonly accepted, since it allows the same number of cables to be installed, slightly increasing the core numbers of cable or installing only the additional bus DALI, if the power cables are already installed.

3. Include in the emergency lighting a distribution board for monitoring the escape luminaires: Giving that DALI-2 system is implemented, not specific manufactures devices are need and only open devices (BECKHOFF, WAGO,….) will be implemented. In this case, the following equipment was considered:

a. 1 x Basic CP module of PLC

b. 1 x 16-channel digital input card

c. 1 x 16-channel digital output board

d. 1 x master card-Dali (64 drivers)

e. 1 x end card

f. 5 x 24Vdc relays

g. HMI touch screen (if automation system is not installed)

h. Various (protections, terminals and other small material)

4. System programming hours: 30 hours.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Subsection

As indicated above, the selected luminaire manufacturer was LIGHTPARTNER LICHTSYSTEME GMBH & CO. KG, which is one of the most common and world-known manufacturers in the naval and offshore sector. All proposed luminaries are marine LED luminaries with DALI driver.

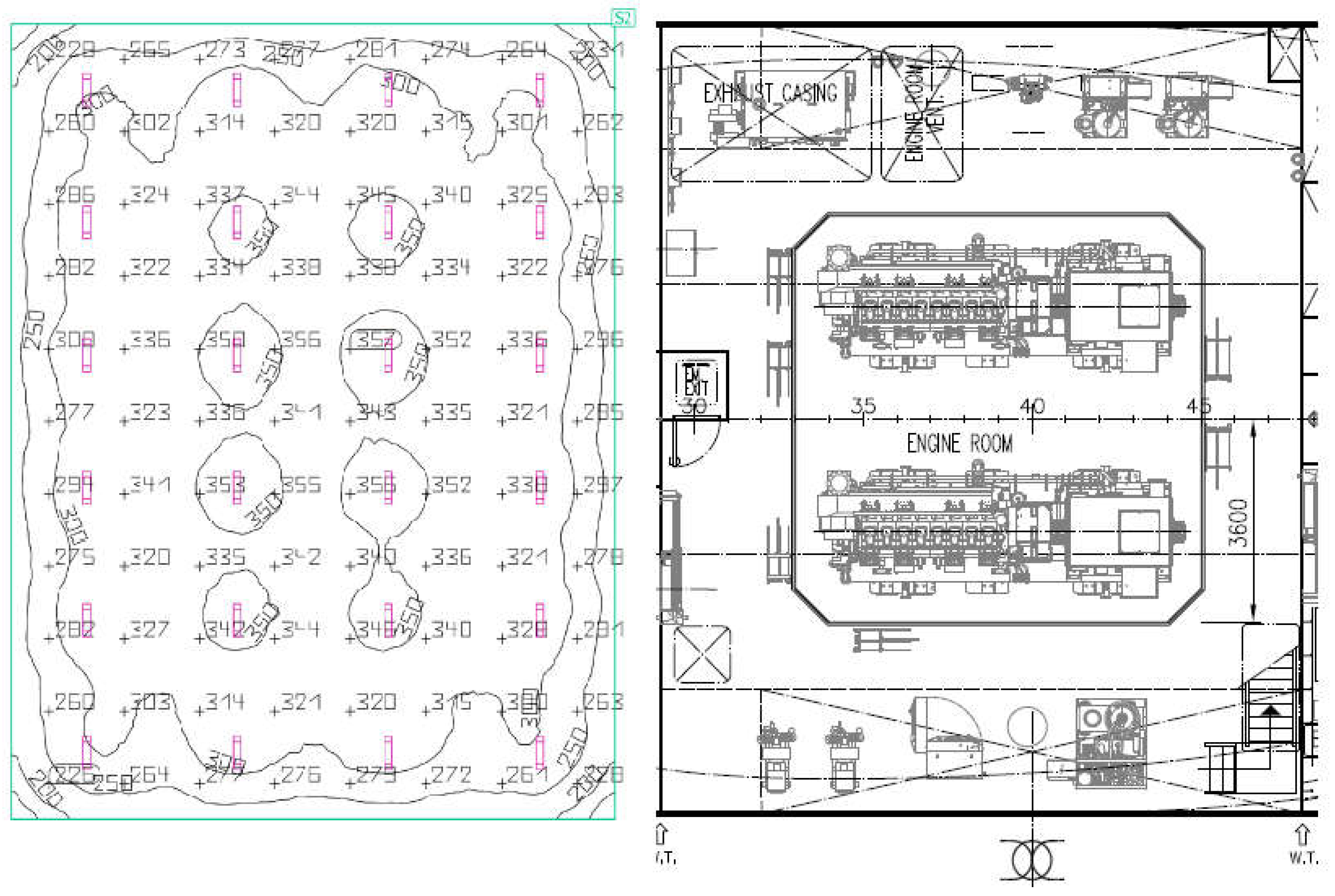

In other to calculate the number and type of lighting devices, lighting calculations have been carried out for each room of the ship's to meet the required lighting level,

Figure 3, by using the DIALUX EVO software.

Table 3 summarizes the number of luminaires for each room of the ship's networks.

Based on the previous table, the installed lighting power of each network is shown in

Table 4.

3.2. Economic Analysis

3.2.1. Results Without the IEC 62034:2012 Standard

According to

Table 4 and the manufacturer price list, the value of the ship's lighting devices amounts to 122,332 €, of which the escape lighting part amounts to 10,014 €.

The following preventive maintenance costs to correctly maintain the exhaust luminaires are estimated to be equivalent to the following annual hours:

• 44 luminaires x 1.25 hours/luminaire and year: 55 hours/year.

Which is equivalent to 55 hours/year x 45 €/hour = 2,475 €/year.

Estimating an expected useful life of 10 years for LED vessel, a maintenance cost for the exhaust lighting is calculated of 2,475x10 = 24,750 €.

3.2.2. Investment Costs

The estimated costs of the aforementioned investment are indicated in

Table 5.

3.2.3. Expected Maintenance Costs According to IEC 62034:2012 Standard

By applying this standard, there is real-time information on the operating status of each luminaire and driver, so any failure (communication, lamp failure, power failure or driver failure) is constantly automatically analyzed (in addition of the tests carried out) without human intervention.

A unit maintenance cost of 5 hours/year x 45 euros/hour = 225 euros is estimated.

Therefore, a preventive maintenance cost is estimated throughout the useful life of the LED of 225x10 = 2,250 €.

3.2.4. NPV

Considering a useful life of 10 years and a discount rate of 12%, taking into account an initial investment of 7,396 € and an expected annual savings of 2,250 €, a NPV of 5,317 € is obtained. Giving that this value is positive, the application of the IEC62034:2012 is economically feasible.

3.2.5. IRR

Taking into account the previous values, the rate that makes the NPV zero is 27%. The profitability is higher than the expected profitability. As it was indicated previously, it is confirmed that the application of the IEC62034:2012 is economically feasible.

3.2.6. DPBP

The discounted payback period is less than 5 years. The initial investment takes less time to recover than the life time of the project, which reaffirms the investment recommendation.

4. Conclusions

The present work analyzes the implementation of the IEC 62034:2012 standard (automatic test system for battery-powered emergency evacuation lighting) in a MPV vessel. Given that part of the crew of these vessels are scientists, an escape (transitional) lighting is recommended for safety and security reasons. The implementation of the IEC 62034:2012 standard for automatic test systems governing battery-powered emergency escape lighting has revealed considerable enhancements in safety and operational efficiency for multipurpose vessels. By enabling real-time monitoring and management of escape lighting systems, this standard ensures their reliability during critical events, significantly enhancing safety for both crew and passengers. Moreover, the shift from manual to automated testing not only leads to reduced maintenance costs but also guarantees that the escape lighting remains in optimal working condition, which is crucial during emergencies. The techno-economic analysis conducted demonstrates a favorable return on investment, further advocating for the integration of these standards in both new and existing maritime vessels.

Looking ahead, the methodologies and insights gleaned from this study have broader applicability beyond the specific vessel analyzed, making them relevant for various types of maritime operations requiring effective escape lighting systems. Future research should focus on evaluating the long-term impacts of the IEC 62034:2012 standard’s implementation across diverse marine environments, alongside investigating the integration of innovative technologies, such as intelligent lighting controls and renewable energy sources. This proactive approach will enhance both safety and sustainability in maritime operations. Ultimately, the effective adoption of the IEC 62034:2012 standard represents a critical advancement in maritime safety, underscoring the need for continuous investment in safety technologies within the shipping industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.R. and M.I.L.; methodology, L.C.S.; software, L.G.R., formal analysis, L.G.R., M.I.L, and L.C.S.; investigation, L.G.R., M.I.L, and L.C.S.; resources, L.C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.R. and M.I.L.; writing—review and editing, M.I.L. and L.C.S.; visualization, L.C.S.; supervision, L.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Project 101181231 “Multi-disciplinary risk management for stable, safe, and sustainable offshore wind-powered hydrogen production” (WINDHY), financed by the European Commission under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie (MSCA) Staff Exchanges Actions of the Horizon Europe. This research was also partially funded by Project TED2021-132534B–I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”. Besides, this study contributes to the international project 3E-Partnership (proposal number 101128576) funded with support from the European Commission under the Action ERASMUS-LS and the Topic ERASMUS-EDU-2023-CBHE-STRAND-2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Achim, W. Emergency lighting. Illuminating engineering optimization of emergency lights. Lights, 36, 2017.

- American Bureau of Shipping. Guidance Notes on the Application of Escape Lighting Systems. Houston: ABS Publications. 2021.

- Andrzej, P. Comparison of results of computer simulations for the escape route lighting installation. Przeglad Elektrotechniczny, 92, 169-177, 2016.

- Aizlewood, C.E.; Webber, G.M.B. Escape route lighting: comparison of human performance with traditional lighting and wayfinding systems. Lighting Research & Technology, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, A.; Dalaklis, D.; Ölçer, A. Inclusion of Shipping in the EU-ETS: Assessing the Direct Costs for the Maritime Sector Using the MRV Data. Energies. 2021. [CrossRef]

- DNV. Rules for classification. Ships. Part 4: systems and components. Chapter 8: Electrical Installations. 6.2, Lighting. 2021.

- European Maritime Safety Agency. Guidelines for the Installation of Emergency Lighting on Ships. Lisbon: EMSA. 2019.

- IEC 62034:2012. Automatic test systems for battery powered emergency escape lighting.

- International Maritime Organization. International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS). London: IMO Publishing. 2020.

- IMORULES - Guidelines for the Evaluation, Testing and Application of Low-Location Lighting on Passenger Ships. Section 18 Crew and Passenger Emergency Safety Systems.

- ISO 9885-3_2006 Lighiting of work places, part 1: indoor.

- Jelena, A. Emergency escape lighting systems. 1st International Conference on Electrical and Control Technologies, ECT, 2006.

- Jin, H.; Schinas, O. Ownership of assets in Chinese shipping funds. Iternational Journal of Finantial Studies. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Liu, Y.A.; Wang, L. Development of a mixed reality assisted escape system for underground mine-based on the mine water-inrush accident background. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, 143, 105471, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.J.; Chang, H.Y.; Hung, B. Identifying Key Financial, Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG), Bond, and COVID-19 Factors Affecting Global Shipping Companies—A Hybrid Multiple-Criteria Decision-Making Method. Sustainability. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.J.; Sun-Weng, H.; Chang, H.Y. Factors influencing follow-on public offering of shipping companies from investor perspective - A hybrid multiple-criteria decision-making approach. Technological and Economic Development of Economy. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mukazi, I.; Wijaya, M.M.; Dewadi, F.M. Development of Solar-Powered Fishing Boats with Leak Threat Sensor System: A Sustainable Solution for Indonesian Fishermen. Kumawula. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Salata, F.; Golasi, I.; Bombelli, E.; Vollaro, E.; Nardecchia, F.; Pagliaro, F.; Gugliermetti, F.; Vollaro, A. Case study on economic return on investments for safety and emergency lighting in road tunnels. Sustainability, 7, 9809-9822, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Sędziwy, A.; Basiura, A.; Wojnicki, I. Roadway Lighting Retrofit: Environmental and Economic Impact of Greenhouse Gases Footprint Reduction. Sustainability. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Shibabrata, M.; Parthassarathi, S.; Saswti, M. Development of a microcontroller based emergency lighting system with smoke detection and mobile communication facilities. Light and Engineering, 27, 46-50, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Suardi, S.; Kyaw, A.Y.; Wulandary, A.I. Impacts of Application Light-Emitting Diode (LED) Lamps in Reducing Generator Power on Ro-Ro Passenger Ship 300 GT KMP Bambit. JMES Int. Journal of Mech. Eng. Sc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Talluri, L.; Nalianda, D.; Kyprianidis, K. Techno economic and environmental assessment of wind assisted marine propulsion systems. Ocean Engineering. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Towle, L.C. An analysis of the overall integrity of an escape route lighting system. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Electrical Safety in Hazardous Environments, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Lee, H.S. Evaluating financial performance of Taiwan container shipping companies by strength and weakness indices. International Journal of Computer Mathematics. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Wati, G.; Suardi, S.; Mubarak, A.A. Analysis of Generator Power Requirements for Lighting Distribution Using LED Lights on a 500 DWT Sabuk Nusantara. ISMATECH. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Ren, J.; Zhong, Z. Design of monitoring and control system for unmanned ship based on FPGA. Proceedings Volume 12599, Second International Conference on Digital Society and Intelligent Systems (DSInS 2022); 125992O, 2023.

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, J.; Liu, J. Design of a ship light environment control system. Proceedings Volume 12717, 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and High-Performance Computing (AIAHPC 2023). 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).