Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods Plant Material

2.1. Plant Material

Extraction Methods

FTIR Analysis

Analgesic Activity

Animals and Ethical Approval

Hot Plate Test

GC-MS Analysis

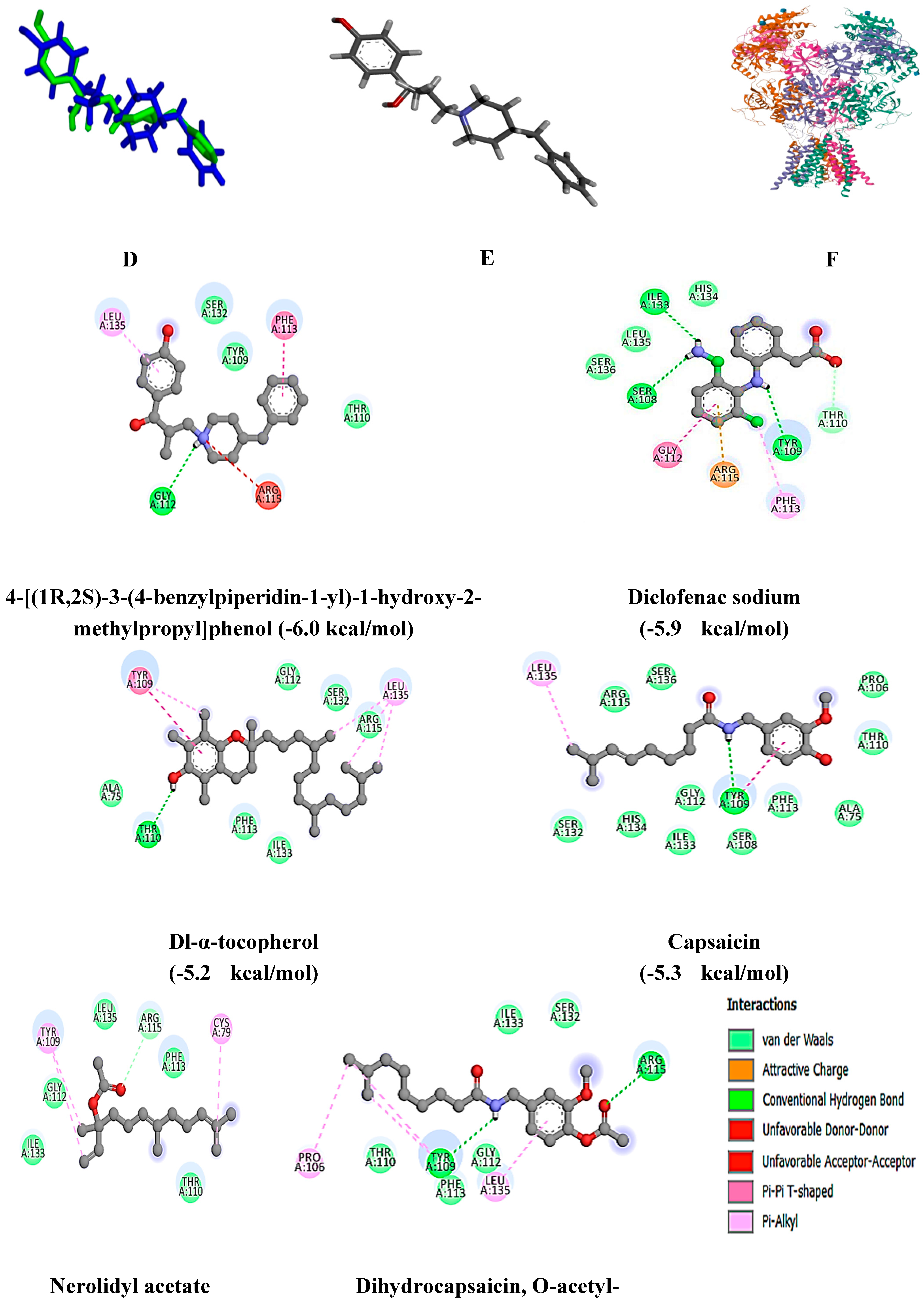

Molecular Docking Studies

Sample Preparation (Virtual Screening)

Molecular Docking

Results and Discussion

Extraction Optimization

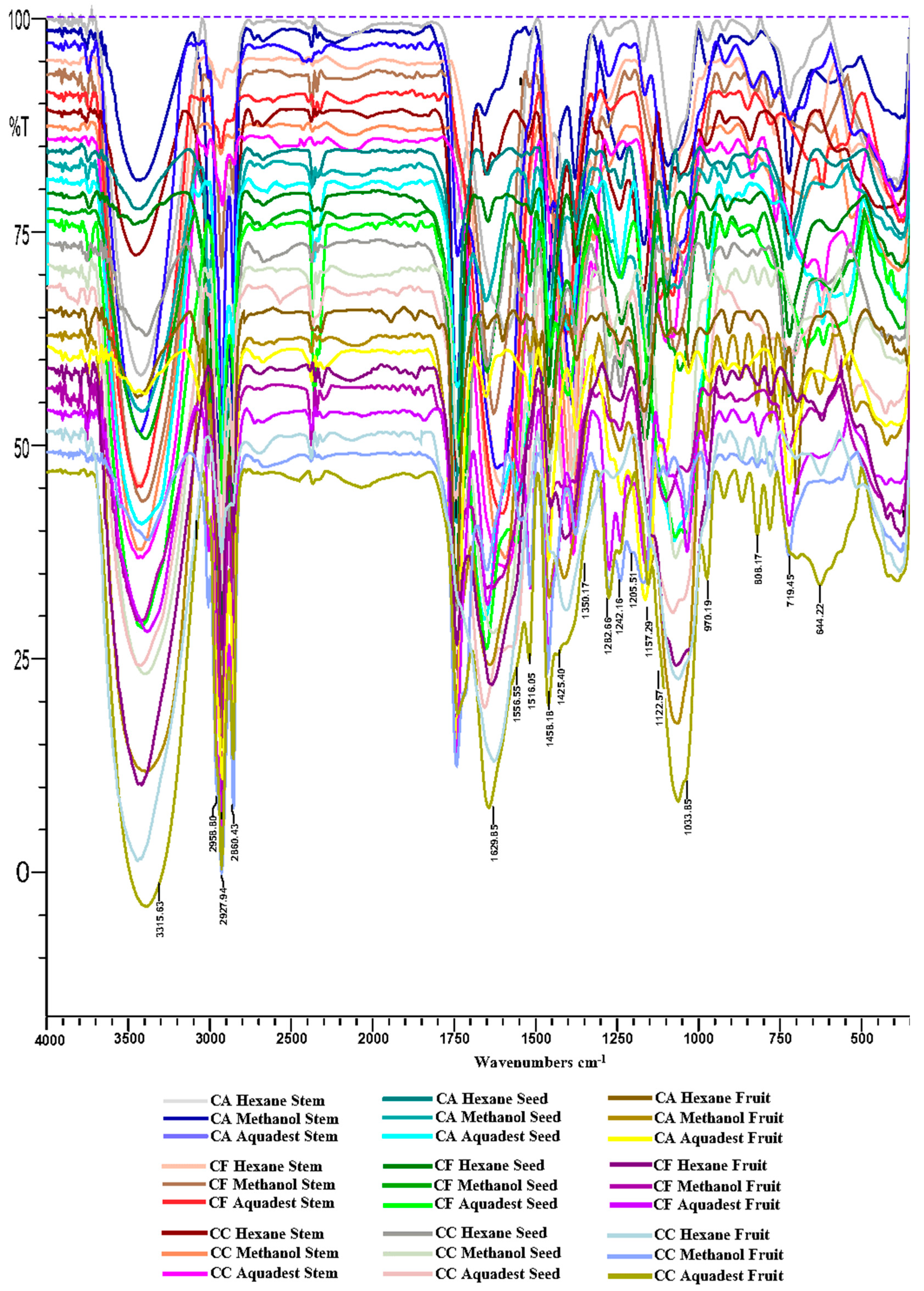

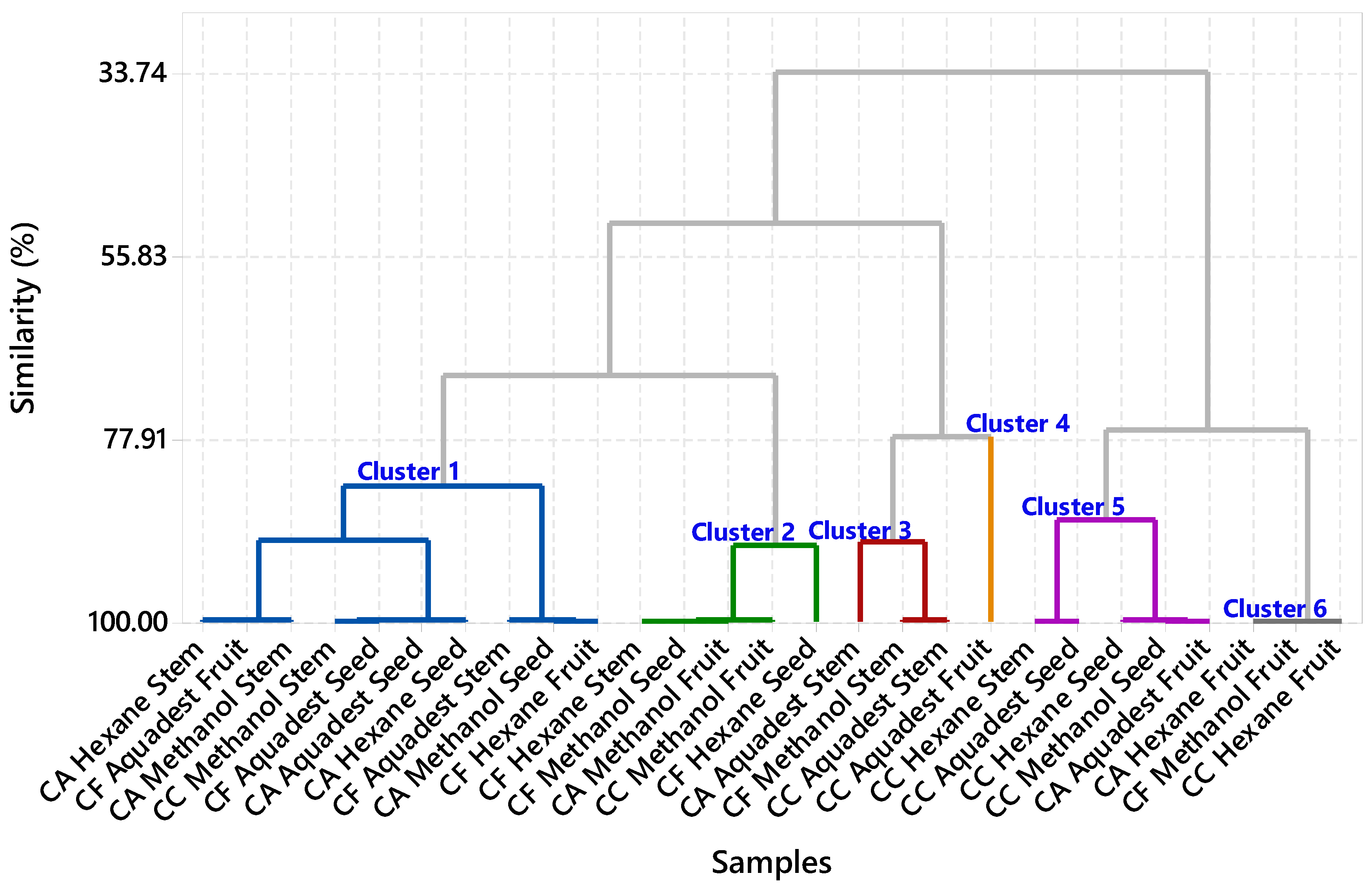

FTIR Profiling Analysis

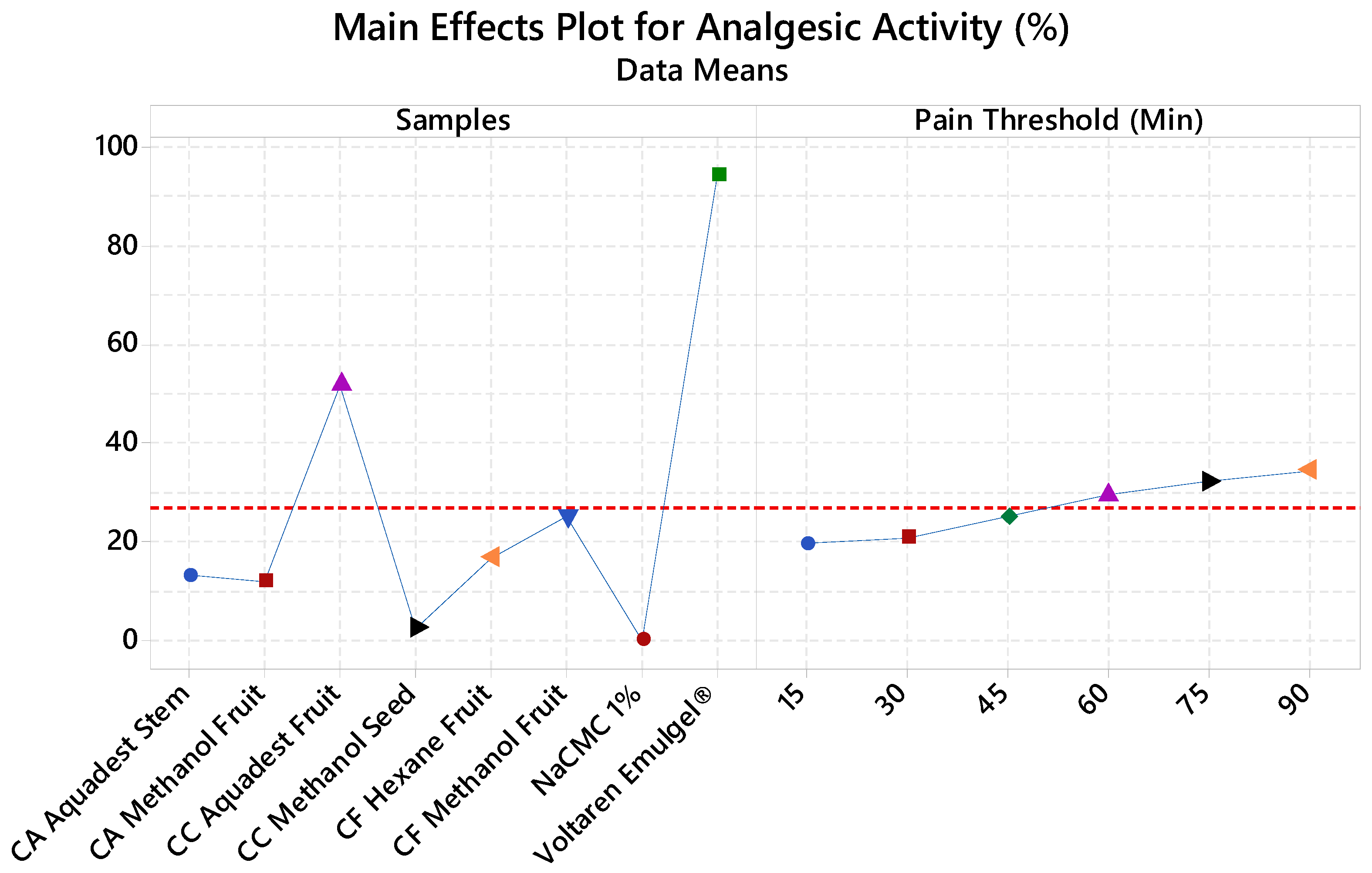

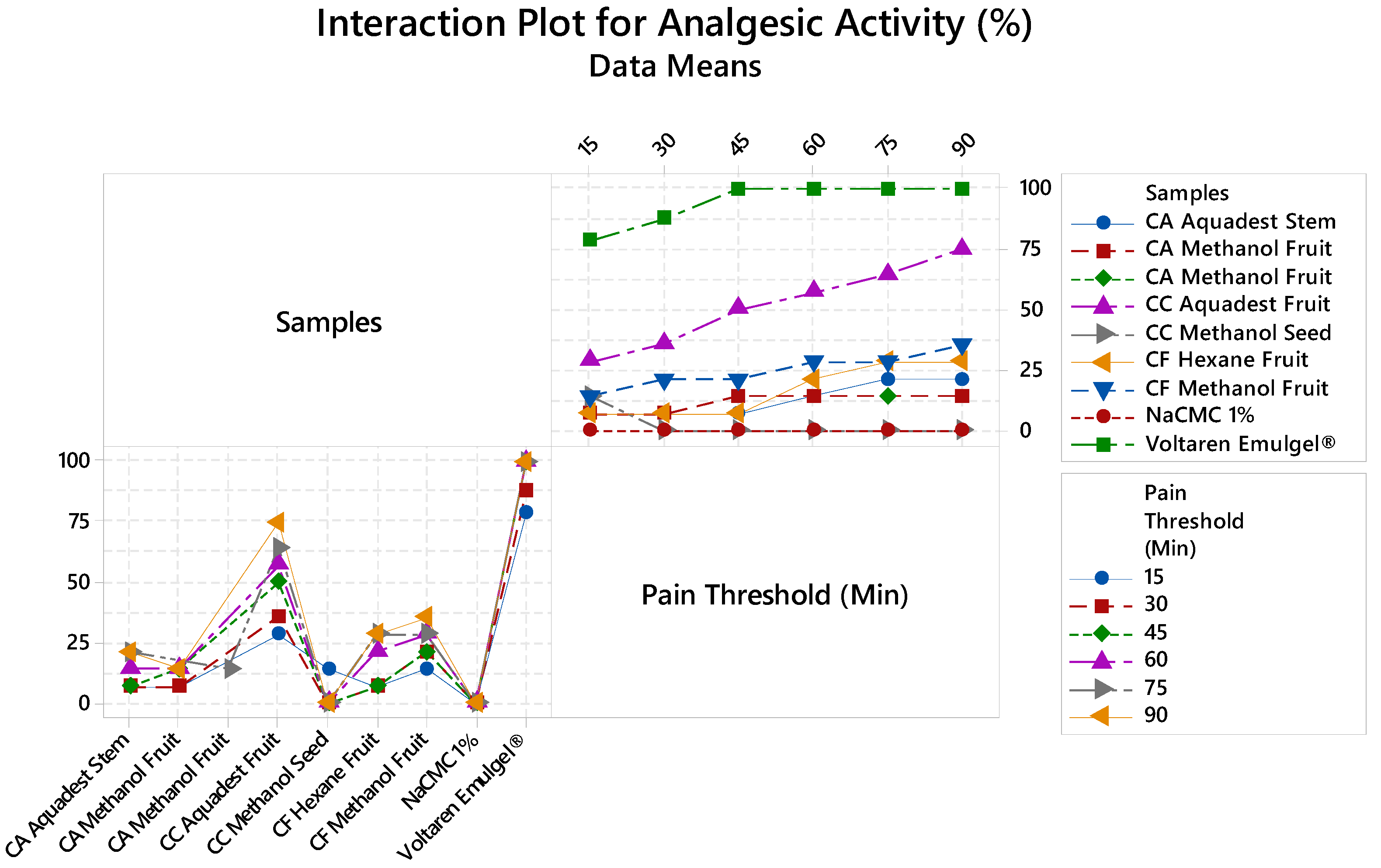

Analgesic Activity

GC-MS Metabolite Characterization

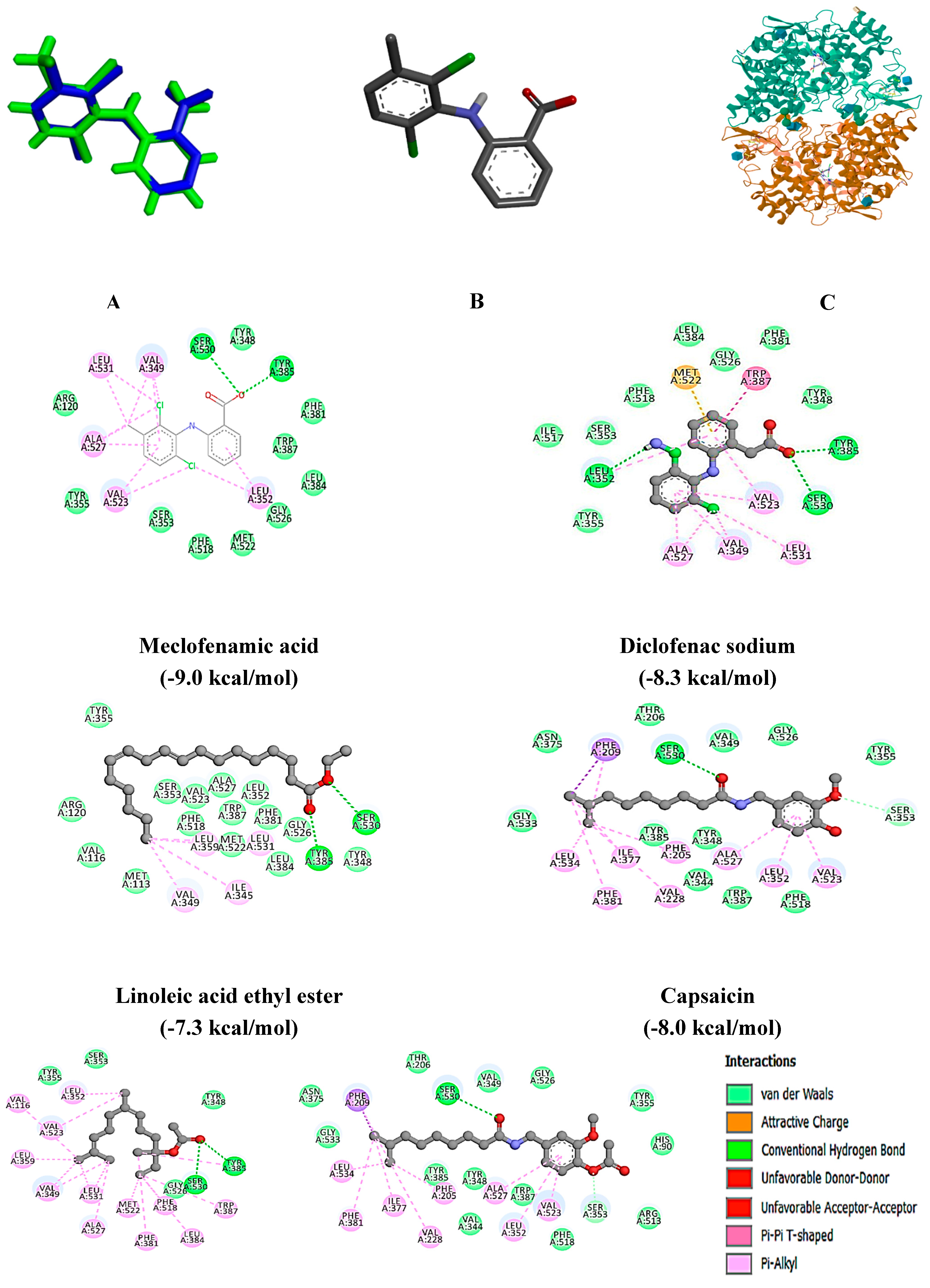

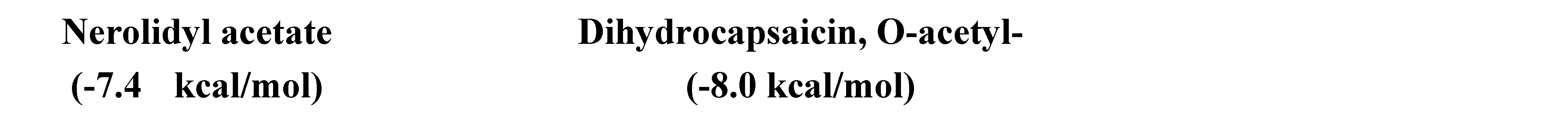

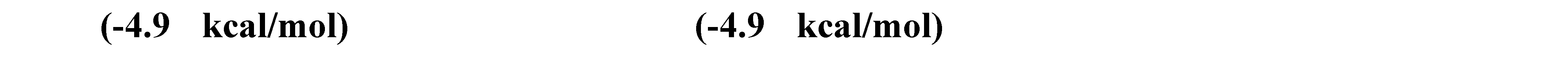

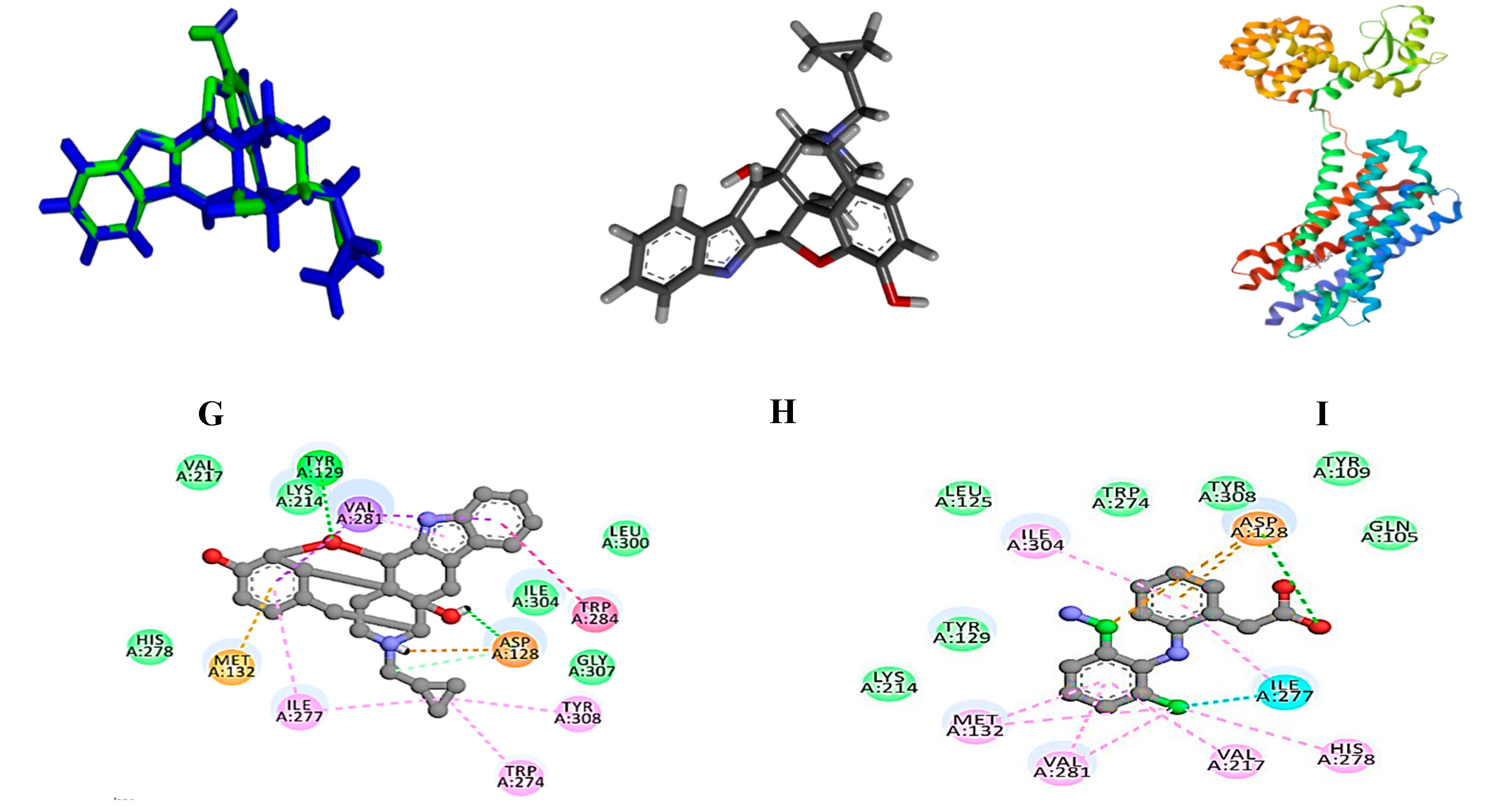

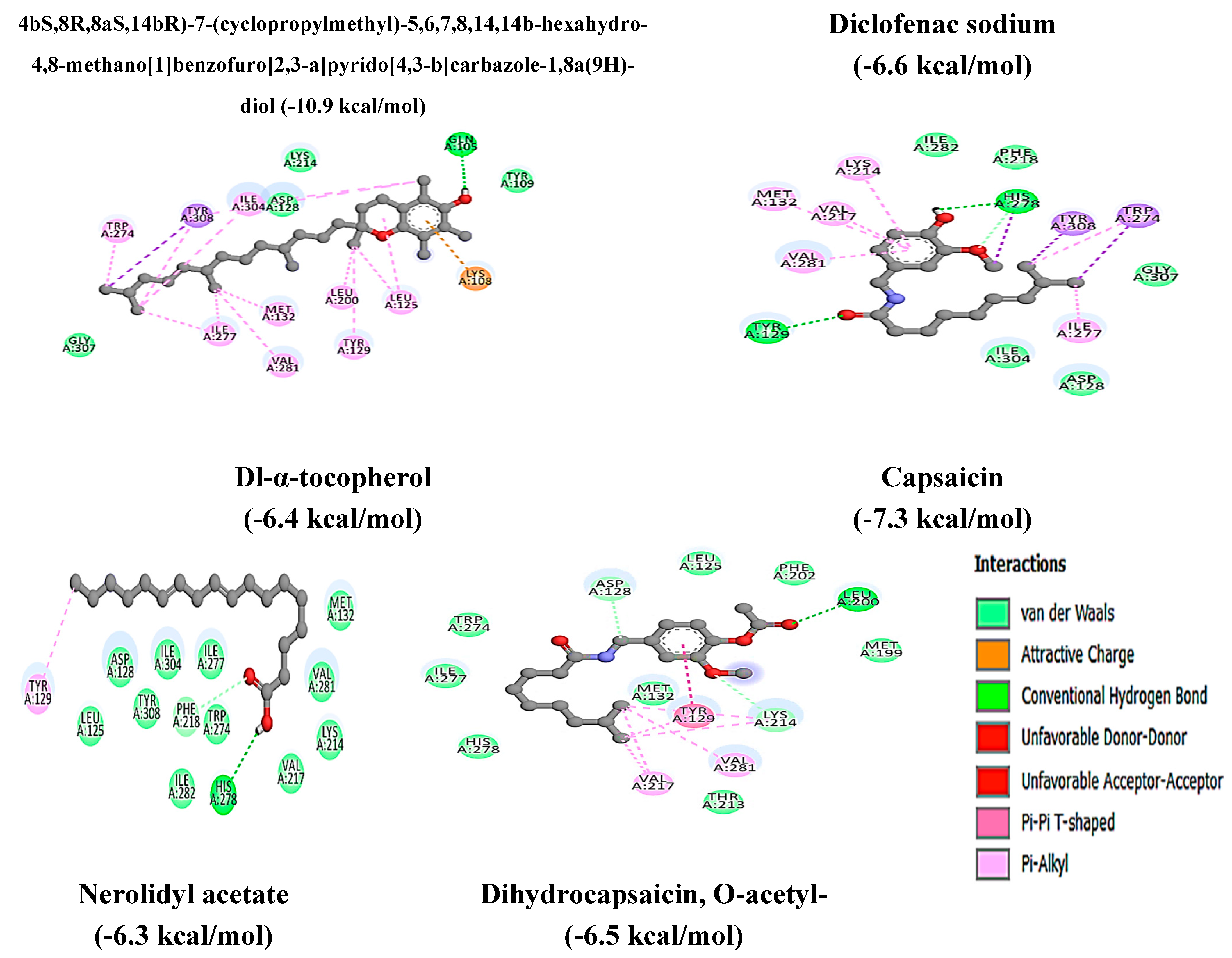

Molecular Docking Analysis

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Peghetti, A.; Seri, R.; Cavalli, E.; Martin, V. Pain Management. In Pearls and Pitfalls in Skin Ulcer Management. In Pearls and Pitfalls in Skin Ulcer Management; Maruccia, M., Papa, G., Ricci, E., Giudice, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandelani, F.F.; Nyalunga, S.L.N.; Mogotsi, M.M.; Mkhatshwa, V.B. Chronic pain: its impact on the quality of life and gender. Front. Pain Res. 2023, 4, 1253460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabernacki, T.; Gilbert, D.; Rhodes, S.; Scarberry, K.; Pope, R.; McNamara, M.; Gupta, S.; Banik, S.; Mishra, K. The burden of chronic pain in transgender and gender diverse populations: Evidence from a large US clinical database. Eur. J. Pain 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberio, P.; Balordi, M.; Castaldo, M.; Viganò, A.; Jacobs, F.; Benvenuti, C.; Torrisi, R.; Zambelli, A.; Santoro, A.; De Sanctis, R. Empowerment, Pain Control, and Quality of Life Improvement in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients through Pain Neuroscience Education: A Prospective Cohort Pilot Study Protocol (EMPOWER Trial). J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaibel, D.; Fernandez, C.J.; Pappachan, J.M. Acute worsening of microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus during rapid glycemic control: The pathobiology and therapeutic implications. World J. Diabetes 2024, 15, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tushingham, S.; Cottle, J.; Adesokan, M.; Ogwumike, O.O.; Ojagbemi, A.; Stubbs, B.; Fatoye, F.; O Babatunde, O. The prevalence and pattern of comorbid long-term conditions with low back pain and osteoarthritis in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Heal. Promot. Educ. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanza, C.; Romenskaya, T.; Racca, F.; Rocca, E.; Piccolella, F.; Piccioni, A.; Saviano, A.; Formenti-Ujlaki, G.; Savioli, G.; Franceschi, F.; et al. Severe Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy: Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Critical Illness. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoupras, A.; Gkika, D.A.; Siadimas, I.; Christodoulopoulos, I.; Efthymiopoulos, P.; Kyzas, G.Z. The Multifaceted Effects of Non-Steroidal and Non-Opioid Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Drugs on Platelets: Current Knowledge, Limitations, and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, I.; Anwar, M.; Murtaza, B.; Khan, M.I. Molecular mechanisms of morphine tolerance and dependence; novel insights and future perspectives. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2023, 479, 1457–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, A.; Laitman, A. Safe Management of Adverse Effects Associated with Prescription Opioids in the Palliative Care Population: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhapra, A.; MacLean, R.R.; Rosenheck, R.; Becker, W.C. Are opioids effective analgesics and is physiological opioid dependence benign? Revising current assumptions to effectively manage long-term opioid therapy and its deprescribing. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 90, 2962–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamadi, N.; Asiri, A.H.; Alshahrani, F.M.; Alqahtani, A.Y.; Al Qout, M.M.; A Alnami, R.; Alasiri, A.S.; Al-Zomia, A.S. Gastrointestinal Complications Associated With Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Use Among Adults: A Retrospective, Single-Center Study. Cureus 2022, 14, e26154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhu, X. Insights from pharmacovigilance and pharmacodynamics on cardiovascular safety signals of NSAIDs. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1455212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaForge, J.M.; Urso, K.; Day, J.M.; Bourgeois, C.W.; Ross, M.M.; Ahmadzadeh, S.; Shekoohi, S.; Cornett, E.M.; Kaye, A.M.; Kaye, A.D. Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Clinical Implications, Renal Impairment Risks, and AKI. Adv. Ther. 2023, 40, 2082–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare, T.T.; Uzoeto, H.O.; Gonlepa, L.N.; Cosmas, S.; Ajima, J.N.; Arazu, A.V.; Ezechukwu, S.P.; Didiugwu, C.M.; Ibiang, G.O.; Osotuyi, A.G.; et al. Evolution and challenges of opioids in pain management: Understanding mechanisms and exploring strategies for safer analgesics. Med. Chem. Res. 2024, 33, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranova, H.; Valkova, V.; Gabriny, L. Chili peppers (Capsicum spp.): the spice not only for cuisine purposes: an update on current knowledge. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1379–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Patel, D.K. Biological Importance, Pharmacological Activities, and Nutraceutical Potential of Capsanthin: A Review of Capsicum Plant Capsaicinoids. Curr. Drug Res. Rev. 2024, 16, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.D.N.C.; Ferraz, G.V.; da Silva, L.R.; Oliveira, A.C.; de Almeida, L.R.; Costa, M.F.; Silva, R.N.O.; da Silva, V.B.; Lopes, Â.C.d.A.; Gomes, R.L.F. Assessment of phenotypic divergence and hybrid development in ornamental peppers (Capsicum spp.). Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 15. [CrossRef]

- Kebu, Z.; Gure, A.; Molole, G.J. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content, Lipophilic Components, and Antioxidant Activities of Capsicum annuum Varieties Grown in Omo Nada, Jimma, Ethiopia. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19, 1934578X241306244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolayemi, A.; Ojewole, J. Comparative anti-inflammatory properties of Capsaicin and ethylaAcetate extract of Capsicum frutescens linn [Solanaceae] in rats. Afr. Heal. Sci. 2013, 13, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, V.; Porwal, M.; Sikarwar, M.S.; Singh, B.; Choudhary, P.; Mohanta, B.C. A review on phytochemical and pharmacological potential of Bhut Jolokia (a cultivar of Capsicum chinense Jacq.). J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 14, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranova, H.; Valkova, V.; Gabriny, L. Chili peppers (Capsicum spp.): the spice not only for cuisine purposes: an update on current knowledge. Phytochem. Rev. 2021, 21, 1379–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, T.; Destandau, E.; Lesellier, E. Selective extraction of bioactive compounds from plants using recent extraction techniques: A review. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1635, 461770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, B.; Rohman, A. Optimization of Pagoda (Clerodendrum paniculatum L.) Extraction Based By Analytical Factorial Design Approach, Its Phytochemical Compound, and Cytotoxicity Activity. Egypt. J. Chem. 2022, 65, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, B.; Mus, S.; Rahimah, S.; Tandiongan, R.M.; Klara, K.P.; Afrida, N.; Nisaa, N.R.K.; Risna, R.; Jur, A.W.; Alam, G.; et al. Antimicrobial Profiling of Piper betle L. and Piper nigrum L. Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): Integrative Analysis of Bioactive Compounds Based on FT-IR, GC-MS, and Molecular Docking Studies. Separations 2024, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, A.; Vasamsetti, B.M.K.; Park, J.-H. A comprehensive review of capsaicin: Biosynthesis, industrial productions, processing to applications, and clinical uses. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Xue, Y.; Fu, L.; Wang, Y.; He, M.; Zhao, L.; Liao, X. Extraction, purification, bioactivity and pharmacological effects of capsaicin: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 5322–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bedairy, M.D.O.; Al-Saadi, Z.S.H.; Al_Majidi, Z.R.K.; Al-Humairi, M.S.K.; Al-groushi, F.A.A.R.; Al-Waeli, M.B.B.M.; Al-Abode, M.A.J.; Al_Aazawei, A.H.N. Anticoagulant, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Activity: Biological Activity and Investigation of Bioactive Natural Compounds Using FTIR and GC-MS Techniques. J. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2024, 7, 2236–2249. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya-Rodriguez, C.A.; Carvajal-Zamorano, K.; Bustos, D.; Alegría-Arcos, M.; Castillo, K. A journey from molecule to physiology and in silico tools for drug discovery targeting the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) channel. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1251061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Eltayeb, W.A.; Rakshit, G.; El-Arabey, A.A.; Khan, J.; Aldosari, S.M.; Alshehri, B.; Abdalla, M. Dual synergistic inhibition of COX and LOX by potential chemicals from Indian daily spices investigated through detailed computational studies. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, B.; Alam, G. Chemometrics-Assisted Fingerprinting Profiling of Extract Variation From Pagoda (Clerodendrum Paniculatum L.) Using Tlc-Densitometric Method. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.F.; Khodve, G.; Yadav, S.; Mallick, K.; Banerjee, S. Probiotic treatment improves post-traumatic stress disorder outcomes in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2025, 476, 115246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachnani, R.; Sepulveda, D.E.; Booth, J.L.; Zhou, S.; Graziane, N.M.; Raup-Konsavage, W.M.; Vrana, K.E. Chronic Cannabigerol as an Effective Therapeutic for Cisplatin-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, M.; Yamada, A.; Yamada, A.I.; Wu, Q.; Kridsada, K.; Ling, J.; Yu, H.; Dong, P.; Ma, M.; Gu, J.; et al. Distinct local and global functions of mouse Aβ low-threshold mechanoreceptors in mechanical nociception. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Ali, G.; Rahman, K.; Khan, Y.; Ayaz, M.; Mosa, O.F.; Nawaz, A.; Hassan, S.S.U.; Bungau, S. Efficacy of 2-Hydroxyflavanone in Rodent Models of Pain and Inflammation: Involvement of Opioidergic and GABAergic Anti-Nociceptive Mechanisms. Molecules 2022, 27, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Mazumder, U.; Kumar, R.S.; Gomathi, P.; Rajeshwar, Y.; Kakoti, B.; Selven, V.T. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic effects of methanol extract from Bauhinia racemosa stem bark in animal models. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 98, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijazi, M.A.; El-Mallah, A.; Aboul-Ela, M.; Ellakany, A. Evaluation of Analgesic Activity of Papaver libanoticum Extract in Mice: Involvement of Opioids Receptors. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 8935085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olguín-Rojas, J.A.; Vázquez-León, L.A.; Palma, M.; Fernández-Ponce, M.T.; Casas, L.; Barbero, G.F.; Rodríguez-Jimenes, G.d.C. Re-Valorization of Red Habanero Chili Pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) Waste by Recovery of Bioactive Compounds: Effects of Different Extraction Processes. Agronomy 2024, 14, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusankha, G.D.M.P.; Siow, L.F.; Thoo, Y.Y. Efficacy of green solvents in pungent, aroma, and color extractions of spice oleoresins and impact on phytochemical and antioxidant capacities. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.; Rawoof, A.; Kumar, A.; Momo, J.; Ahmed, I.; Dubey, M.; Ramchiary, N. Genetic Regulation, Environmental Cues, and Extraction Methods for Higher Yield of Secondary Metabolites in Capsicum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 9213–9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.T.; Chen, Q.; Hong, R.Y.; Kumar, M.R. Preparation of oleic acid modified multi-walled carbon nanotubes for polystyrene matrix and enhanced properties by solution blending. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2015, 26, 8667–8675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colli-Pacheco, J.P.; Rios-Soberanis, C.R.; Moo-Huchin, V.M.; Perez-Pacheco, E. Study of the incorporation of oleoresin Capsicum as an interfacial agent in starch-poly (lactic acid) bilayer films. Polym. Bull. 2022, 80, 9077–9095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Ayub, H. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) technique for food analysis and authentication. In Nondestructive Quality Assessment Techniques for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 103–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranska, M.; Schulz, H. Determination of alkaloids through infrared and Raman spectroscopy. Alkaloids: Chem. Biology 2009, 67, 217–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, V. K. Infrared Spectroscopy. In Instrumental Methods of Chemical Analysis; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 179–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Hao, Y.; Zhao, M.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Lin, Y.; Liang, S. Efficient enzymatic synthesis of D-α-tocopherol acetate by Carica papaya lipase-catalyzed acetylation of D-α-tocopherol in a solvent-free system. LWT 2024, 202, 116289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguettaya, A.; Yu, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; Song, A. Efficient agglomerative hierarchical clustering. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 2785–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.; Kim, J.S.; Woo, M.R.; Ji, S.H.; Park, S.; Din, F.U.; Kim, J.O.; Youn, Y.S.; Oh, K.T.; Lim, S.-J.; et al. Establishment of nanoparticle screening technique: A pivotal role of sodium carboxymethylcellulose in enhancing oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble aceclofenac. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, N.K.; Biswas, P.; Khandker, A.; Tareq, M.I.; Tauhida, S.J.; Shishir, T.A.; Bibi, S.; Alam, A.; Zilani, N.H.; Albekairi, N.A.; et al. Profiling of antioxidant properties and identification of potential analgesic inhibitory activities of Allophylus villosus and Mycetia sinensis employing in vivo, in vitro, and computational techniques. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 336, 118695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, P.N.; Calado, C.C.R. Enhancing Bioactive Compound Classification through the Synergy of Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Advanced Machine Learning Methods. Antibiotics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, Y.-M.; He, X.-B.; Jing, Y.-K.; Wang, L.-R.; Wang, J.-M.; Xie, X.-Q. Computational systems pharmacology analysis of cannabidiol: a combination of chemogenomics-knowledgebase network analysis and integrated in silico modeling and simulation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2019, 40, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 52. Zilani, M.N.H.; Islam, M.A.; Biswas, P.; Anisuzzman, M.; Hossain, H.; Shilpi, J.A.; Hasan, M.N.; Hossain, M.G. Metabolite profiling, anti-inflammatory, analgesic potentials of edible herb Colocasia gigantea and molecular docking study against COX-II enzyme. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2021, 281, 114577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Jiang, X.; Zu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Xu, Z.; Ding, H.; Zhao, Q. A comprehensive description of GluN2B-selective N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 200, 112447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunro, O.B.; Richard, G.; Izah, S.C.; Ovuru, K.F.; Babatunde, O.T.; Das, M. Citrus aurantium: Phytochemistry, Therapeutic Potential, Safety Considerations, and Research Needs. In Herbal Medicine Phytochemistry: Applications and Trends; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.; Gaspar, H.; Silva, J.; Alves, C.; Martins, A.; Teodoro, F.; Susano, P.; Pinteus, S.; Pedrosa, R. Unravelling the Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Potential of the Marine Sponge Cliona celata from the Portuguese Coastline. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, S.A.; Vickers, M.H.; Zhang, X.D.; Gray, C.; Reynolds, C.M. Maternal supplementation with conjugated linoleic acid in the setting of diet-induced obesity normalises the inflammatory phenotype in mothers and reverses metabolic dysfunction and impaired insulin sensitivity in offspring. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, K.; Bai, S.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, J.; Peng, H.; Xuan, Y.; Su, Z.; Ding, X. Effects of Maternal and Progeny Dietary Vitamin E on Growth Performance and Antioxidant Status of Progeny Chicks before and after Egg Storage. Animals 2021, 11, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, J.; Feng, Z.; Song, X. Pharmacological activity of capsaicin: Mechanisms and controversies (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 29, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; Alqahtani, A.; Ojo, O.A.; Shaheen, H.M.; Wasef, L.; Elzeiny, M.; Ismail, M.; Shalaby, M.; Murata, T.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A.; et al. Biological Properties, Bioactive Constituents, and Pharmacokinetics of Some Capsicum spp. and Capsaicinoids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almotayri, A.; Jois, M.; Radcliffe, J.; Munasinghe, M.; Thomas, J. The effects of red chilli, black pepper, turmeric, and ginger on body weight-A systematic review. Hum. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 19, 200111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, B.J.; Malkowski, M.G. Substrate-selective Inhibition of Cyclooxygeanse-2 by Fenamic Acid Derivatives Is Dependent on Peroxide Tone. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 15069–15081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Ferré, H.E.; Guajardo-Flores, D.; La Vega, G.R.-D.; Gutierrez-Uribe, J.A. Recovery of Capsaicinoids and Other Phytochemicals Involved With TRPV-1 Receptor to Re-valorize Chili Pepper Waste and Produce Nutraceuticals. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 588534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Lü, W.; Michel, J.C.; Goehring, A.; Du, J.; Song, X.; Gouaux, E. NMDA receptor structures reveal subunit arrangement and pore architecture. Nature 2014, 511, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laorob, T.; Ngoenkam, J.; Nuiyen, A.; Thitiwuthikiat, P.; Pejchang, D.; Thongsuk, W.; Wichai, U.; Pongcharoen, S.; Paensuwan, P. Comparative effectiveness of nitro dihydrocapsaicin, new synthetic derivative capsaicinoid, and capsaicin in alleviating oxidative stress and inflammation on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated corneal epithelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2024, 244, 109950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granier, S.; Manglik, A.; Kruse, A.C.; Kobilka, T.S.; Thian, F.S.; Weis, W.I.; Kobilka, B.K. Structure of the δ-opioid receptor bound to naltrindole. Nature 2012, 485, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Stillerov, V.T.; Dracinsky, M.; Gaustad, H.L.A.; Lorenzi, Q.; Smrckova, H.; Reinhardt, J.K.; Lienard, M.A.; Bednarova, L.; Sacha, P.; et al. Discovery and isolation of novel capsaicinoids and their TRPV1-related activity. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Samples | Plant Parts | Solvent |

Extract (g) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | Capsicum annuum | Stem | Hexane | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Methanol | 1.1 | 5.5 | |||

| Aquadest | 2.4 | 12 | |||

| Seed | Hexane | 2 | 10 | ||

| Methanol | 1 | 5 | |||

| Aquadest | 0.8 | 4 | |||

| Fruit | Hexane | 1 | 5 | ||

| Methanol | 2 | 10 | |||

| Aquadest | 3.6 | 18 | |||

| CF | Capsicum frutescens | Stem | Hexane | 0.2 | 1 |

| Methanol | 2 | 10 | |||

| Aquadest | 2.9 | 14.5 | |||

| Seed | Hexane | 1 | 5 | ||

| Methanol | 2 | 10 | |||

| Aquadest | 0.7 | 3.5 | |||

| Fruit | Hexane | 1 | 5 | ||

| Methanol | 3 | 15 | |||

| Aquadest | 4.7 | 23.5 | |||

| CC | Capsicum chinense | Stem | Hexane | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Methanol | 1.7 | 8.5 | |||

| Aquadest | 1.4 | 7 | |||

| Seed | Hexane | 1 | 5 | ||

| Methanol | 1 | 5 | |||

| Aquadest | 0.8 | 4 | |||

| Fruit | Hexane | 1 | 5 | ||

| Methanol | 2 | 10 | |||

| Aquadest | 2.5 | 12.5 |

| Compouds Detected | Molecular formula | MW (g/mol) | Pubchem (CID) | RT (M in) | SI (%) | Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsicum frutescens (CF) hexane fruit extract | ||||||

| Oleic acid | C18H34O2 | 282 | 445639 | 19.025 | 88 | 1.06 |

| Methyl palmitate | C17H34O2 | 270 | 8181 | 21.127 | 97 | 3.90 |

| N-hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 256 | 985 | 22.129 | 95 | 6.74 |

| Methyl linoleate | C19H34O2 | 294 | 5284421 | 24.938 | 96 | 6.66 |

| Methyl oleate | C19H36O2 | 296 | 5364509 | 25.084 | 94 | 5.37 |

| 15-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | C19H36O2 | 296 | 5364490 | 25.217 | 85 | 2.26 |

| Linoleic acid | C18H32O2 | 280 | 5280450 | 26.271 | 93 | 6.88 |

| N-pentadecylacetamide | C17H35NO | 269 | 12009452 | 26.659 | 85 | 6.59 |

| Nerolidol | C15H26O | 222 | 8888 | 29.086 | 86 | 22.64 |

| Heneicosane | C21H44 | 296 | 12403 | 29.417 | 94 | 3.10 |

| Isofucosterol | C29H48O | 412 | 5281326 | 29.892 | 89 | 1.23 |

| Pentacosane | C25H52 | 352 | 12406 | 33.233 | 97 | 1.06 |

| Hexacosane | C26H54 | 366 | 12407 | 36.600 | 96 | 1.08 |

| Squalene | C30H50 | 410 | 638072 | 38.342 | 98 | 3.43 |

| Nonacosane | C29H60 | 408 | 12409 | 39.667 | 97 | 1.42 |

| Dl-α-tocopherol | C29H50O2 | 430 | 2116 | 44.167 | 96 | 1.64 |

| Total | 75.06 | |||||

| Capsicum chinense (CC) aquadest fruit extract | ||||||

| Propanoic acid, 2-methyl- | C4H8O2 | 88 | 6590 | 4.700 | 87 | 3.50 |

| 1-Propanol, 2,2-dimethyl-, acetate | C7H14O2 | 130 | 13552 | 4.906 | 87 | 7.73 |

| Phenol, 2-methoxy- | C7H8O2 | 124 | 460 | 8.894 | 92 | 1.37 |

| (6E)-8-methyl- 6-nonenoic acid | C10H18O2 | 170 | 5365959 | 13.225 | 94 | 1.16 |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | C17H34O2 | 270 | 8181 | 21.044 | 96 | 1.89 |

| Palmitoleic acid | C16H30O2 | 254 | 445638 | 21.668 | 97 | 1.31 |

| N-hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 256 | 985 | 22.076 | 95 | 12.58 |

| 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | C19H34O2 | 294 | 5284421 | 26.080 | 96 | 1.68 |

| Oleic acid | C18H34O2 | 282 | 445639 | 26.167 | 85 | 1.59 |

| 7-tetradecenal, (Z)- | C14H26O | 210 | 5364468 | 26.270 | 87 | 2.19 |

| Linoleic acid ethyl ester | C20H36O2 | 308 | 5282184 | 26.372 | 94 | 2.37 |

| Octadecanoic acid | : C18H36O2 | 284 | 5281 | 26.717 | 93 | 2.91 |

| Nerolidyl acetate | C17H28O2 | 264 | 5363426 | 28.996 | 86 | 11.32 |

| Capsaicin | C18H27NO3 | 305 | 1548943 | 34.746 | 97 | 4.38 |

| Dihydrocapsaicin, O-acetyl- | C20H31NO4 | 349 | 91715808 | 35.182 | 89 | 2.26 |

| Total | 58.24 | |||||

| Compounds | Protein Target | Bond-free energy (kcal/mol) | H-bond Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meclofenamic acid | 5IKQ | -9.0 | Tyr 385, Ser 530 |

| Diclofenac sodium | -8.3 | Leu 352, Tyr 358, Ser 530 | |

| Oleic acid | -6.7 | NI | |

| Methyl palmitate | -6.6 | Arg 120, Tyr 355 | |

| N-hexadecanoic acid | -6.5 | Arg 120, Tyr 355 | |

| Methyl linoleate | -6.9 | Arg 120, Tyr 355 | |

| Methyl oleate | -6.7 | Arg 120 | |

| 15-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | -6.9 | Arg 120 | |

| Linoleic acid | -6.9 | Arg 120 | |

| N-pentadecylacetamide | -6.7 | Arg 120 | |

| Nerolidol | -6.9 | Arg 120 | |

| Heneicosane | -6.7 | NI | |

| Isofucosterol | -4.0 | NI | |

| Pentacosane | -7.2 | NI | |

| Hexacosane | -7.1 | NI | |

| Squalene | -8.5 | NI | |

| Nonacosane | -7.5 | NI | |

| Dl-α-tocopherol | -8.8 | NI | |

| Propanoic acid, 2-methyl- | -4.3 | ALA 151, ARG 496 | |

| 1-Propanol, 2,2-dimethyl-, acetate | -4.9 | ALA 527 | |

| Phenol, 2-methoxy- | -5.3 | MET 522, VAL 523, ALA 527 | |

| >(6E)-8-methyl- 6-nonenoic acid | >-6.3 | TYR 385, SER 530 | |

| >Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | -6.5 | ARG 120, TYR 355 | |

| Palmitoleic acid | >-6.7 | ARG 120, TYR 355 | |

| 9,12-octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | -6.9 | ARG 120, TYR 355 | |

| 7-tetradecenal, (Z)- | -6.2 | ARG 120, TYR 355 | |

| Linoleic acid ethyl ester | -7.3 | TYR 385, SER 530 | |

| Octadecanoic acid | -6.8 | ARG 120 | |

| Nerolidyl acetate | -7.4 | TYR 385, SER 530 | |

| Capsaicin | -8.0 | SER 353, SER 530 | |

| Dihydrocapsaicin, O-acetyl- | -8.0 | SER 353, SER 530 | |

| 4-[(1R,2S)-3-(4-benzylpiperidin-1-yl)-1-hydroxy-2-methylpropyl]phenol | 4TLM | -6.0 | Gly 112 |

| Diclofenac sodium | -5.9 | Ile 133, Ser 108, Tyr 109, Thr 110 | |

| Oleic acid | -4.3 | Ser 132 | |

| Methyl palmitate | -4.2 | Thr 110 | |

| N-hexadecanoic acid | -3.7 | Gly 112, Leu 135 | |

| Methyl linoleate | -4.3 | Thr 110 | |

| Methyl oleate | -3.9 | NI | |

| 15-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | -4.0 | NI | |

| Linoleic acid | -4.2 | NI | |

| N-pentadecylacetamide | -4.5 | Ser 132, Ile 133 | |

| Nerolidol | -4.9 | NI | |

| Heneicosane | -3.9 | NI | |

| Isofucosterol | -6.0 | NI | |

| Pentacosane | -3.7 | NI | |

| Hexacosane | -3.4 | NI | |

| Squalene | -4.5 | NI | |

| Nonacosane | -3.6 | NI | |

| Dl-α-tocopherol | -5.2 | Thr 110 | |

| Propanoic acid, 2-methyl- | -3.5 | Ser 108, His 134, Leu 135, Ser 136 | |

| 1-Propanol, 2,2-dimethyl-, acetate | -3.8 | Tyr 109, Gly 112, Leu 135, Ser 136 | |

| Phenol, 2-methoxy- | -4.3 | His 134 | |

| (6E)-8-methyl- 6-nonenoic acid | -3.4 | Gly 112 | |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | -3.7 | Gly 112, Leu 135 | |

| Palmitoleic acid | -4.2 | NI | |

| 9,12-octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | -4.2 | NI | |

| 7-tetradecenal, (Z)- | -4.0 | NI | |

| Linoleic acid ethyl ester | -4.2 | Arg 115 | |

| Octadecanoic acid | -3.8 | Ile 133 | |

| Nerolidyl acetate | -4.9 | Arg 115 | |

| Capsaicin | -5.3 | Tyr 109 | |

| Dihydrocapsaicin, O-acetyl- | -4.9 | Tyr 109, Arg 115 | |

| (4bS,8R,8aS,14bR)-7-(cyclopropylmethyl)-5,6,7,8,14,14b-hexahydro-4,8-methano[1]benzofuro[2,3-a]pyrido[4,3-b]carbazole-1,8a(9H)-diol | 4EJ4 | -10.9 | Asp 128, Tyr 129 |

| Diclofenac sodium | -6.6 | Asp 128 | |

| Oleic acid | -5.6 | Gln 105, Lys 108, Tyr 109 | |

| Methyl palmitate | -4.8 | NI | |

| N-hexadecanoic Acid | -5.3 | Gly 307, Tyr 308 | |

| Methyl linoleate | 6.0 | Met 199, Leu 200 | |

| Methyl oleate | -5.7 | NI | |

| 15-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | -5.3 | His 278 | |

| Linoleic acid | -5.4 | Phe 218, His 278 | |

| N-pentadecylacetamide | -5.2 | Asp 128, Ile 304 | |

| Nerolidol | -6.5 | NI | |

| Heneicosane | -5.2 | NI | |

| Isofucosterol | -7.7 | NI | |

| Pentacosane | -5.2 | NI | |

| Hexacosane | -5.0 | NI | |

| Squalene | -6.8 | NI | |

| Nonacosane | -5.3 | NI | |

| Dl-α-tocopherol | -6.4 | Gln 105 | |

| Propanoic acid, 2-methyl- | -4.1 | Asp 128, Tyr 308 | |

| 1-Propanol, 2,2-dimethyl-, acetate | -4.6 | NI | |

| (6E)-8-methyl- 6-nonenoic acid | -5.0 | NI | |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | -5.3 | Gly 307, Tyr 308 | |

| Palmitoleic acid | -5.6 | Phe 218, His 278 | |

| 9,12-octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | -5.5 | Lys 214, His 278 | |

| 7-tetradecenal, (Z)- | -5.4 | NI | |

| Linoleic acid ethyl ester | -5.8 | NI | |

| Octadecanoic acid | -5.7 | Gln 105, Tyr 308 | |

| Nerolidyl acetate | -6.3 | His 278, Phe 218 | |

| Capsaicin | -7.3 | Tyr 219, His 278 | |

| Dihydrocapsaicin, O-acetyl- | -6.5 | Asp 128, Lys 214, Leu 200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).